1. Introduction

The sequence

of Chebyshev polynomials provides a typical example of a chaotic system and it was used to obtain a well known and exhaustively analyzed public-key encryption scheme based on chaos [

1,

2,

3]. For any index

r,

has degree

r and its restriction to the open real interval

has as image this interval, namely it is an onto map

, hence the corresponding cryptosystem has

I as the space of both plaintexts and ciphertexts. Since the sequence of Chebyshev polynomials forms a semigroup, namely for any

,

the sequence has served as basis of several chaotic cryptosystems:

for encryption, a public key has the form for and is the private key. Then for a message the ciphertext is , where is a random index selected by the sender of the message, and for decryption the owner of the private key calculates ,

for key agreement (KA), the classic Diffie-Hellman KA scheme can be translated quite directly by the semigroup property [

4],

for authentication, a general scheme is introduced in [

5] in which

servers should authenticate

client using a

central registry (RC). Each server has a key

and each client an index

and the corresponding Chebyshev polynomials are evaluated on secret numbers owned by the RC hence the servers and the clients just know the values of their polynomials at the secret points. Also there is an interesting application of the sequence of Chebyshev polynomials for Radio Frequency IDentification (RFID), where the index

s is broadcasted by a transceiver and each transponder selects a particular index

r and codifies it in order to form an identification label [

6], and

for image encryption the chaotic methods have been extensively used as well as some refinements of chaotic maps [

7,

8].

In [

9] the behaviour Chebyshev sequence in modular arithmetic, as well as its impact on the security of cryptosystems have been analyzed within the context of Number Theory.

In 2005 the most common attack to this cryptosystem was introduced [

10] (see [

4,

11] as well). The attack strategy is based in solving equations of the form

for

with respect to index

r. To this end there are considered just real numbers in

I with a finite length decimal representation. For any

, let

be the collection of numbers in

I whose decimal representation consists of

m digits. Thus, by multiplying the involved real numbers by the power

the stated problem gives rise to congruence relations on the integers solvable by Number Theory techniques.

We performed several experiments in order to test Bergamo’s attack [

10] using multiple precision arithmetic provided by the already conventional software tools

gmp [

12] and

mpfr [

13], we report here the results. We consider a

length for the specification of plaintexts and a

precision, with

, for the number of significant digits in decimal representation. The space of plaintexts is coded as the set of words of length

ℓ with symbols in

, with cardinality

, and the space of ciphertexts is the set of words of length

m with symbols in

.

Bergamo’s attack [

10] is effective whenever

ℓ is known by the attacker. This attack technique would produce several possible solutions for the recovering secret key depending on the assumed value of the length

ℓ. An exhaustive search of the right secret key may be still rather costly. The length

ℓ may be part of the private key in the chaotic crypto-scheme.

The purpose of the current report is to illustrate the importance to fix the length of the plaintexts ℓ and the precision m among the participants in the crypto scenario.

It is worth to mention that some similar remarks related to the difficulties in making effective the attack in [

10] have been pointed out in [

5] and there the authors consider attacks based on impersonation. In [

14] it is pointed also the importance to limit the numerical domains of Chebyshev polynomials.

In section 2 we recall the Chebyshev polynomials and in section 3 we recall the corresponding chaotic cryptosystem and the attack in [

10]. In section 4 we present the performed experiments. Our contribution consists in testing the effectiveness of Bergamo’s attack. We have concluded that it is essential for the attacker to know the length of plaintexts and certainly the arithmetical precision should be greater than this length.

2. Chebyshev Polynomials

Notation. We will write for any two integers

,

,

. For any

, with

we may consider open, semiclosed or closed intervals:

For a radix

,

, let

be the collection of

Rdigits, then for each

,

will denote the set of real numbers in

that can be written as polynomial expressions in terms of

with coefficients in

, in other words

is the set of fractional numbers than can be written with exactly

m digits in radix

R.

As a very basic trigonometric identity we recall that for any

and any

:

Besides,

and

. With the change of variable

,

(see

Figure 1), the sequence of

Chebyshev polynomials follows:

Remark 1.

The sequence is asemigroup, namely

Indeed, using the above mentioned change of variables,

:

From the definition of the Chebyshev polynomials,

hence

where

and

Let us write the powers of matrix

as

Then

Hence,

From here, it follows that

:

.

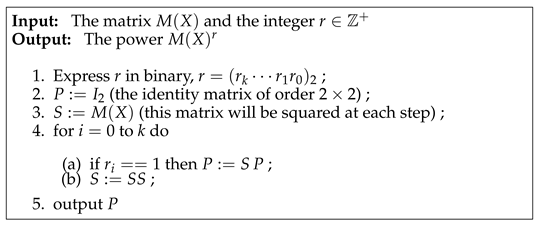

Algorithm 1.

Square-and-product procedure

Algorithm 1.

Square-and-product procedure

The powers of the matrix

can be calculated via

square-and-product:

namely, by the procedure sketched in Algorithm 1.

The Chebyshev polynomials are defined in the interval , the absolute values of the points in this domain are in the unit interval .

Consider the conventional decimal radix,

. Suppose that

is such that

for some

, then there is an integer

such that

, or

. Consequently, from relations (

1) and (2) it follows that

Besides,

and

On the other hand, from step 4(a) of the procedure in

Table 1

as well as, from step 4(b),

Through these relations, the square-and-product algorithm can be performed within multiple precision arithmetic in

using a multiple precision arithmetic on the integers.

Remark 2. In the current experiments we calculate the Chebyshev polynomials through the above “square-and-product” method in order to maintain the multiple precision of the calculations through additions and products and to avoid the dependency of implementations of the maps cos and arccos.

3. The Cryptosystem Based on Chebyshev Polynomials

3.1. The General Scheme

The following is a public-key encryption scheme where the plaintext space and the ciphertext space are both the real interval :

-

Key generation

Choose and large enough. The public key is and the private key is s.

-

Encryption

For a plaintext , choose a random index , and calculate , , . The ciphertext is .

-

Decryption

Given the ciphertext recover the message as .

Hence the time complexity of the encryption procedure is

where

is the time complexity of the chosen algorithm for multiplication in

,

m is the precision of calculations and

r is the chosen random number.

With respect to the Decryption Procedure let us make a remark:

Suppose that a number

x in the open interval

is written in radix

R as

, with digits

, namely

. Then for any

:

where

is the decimal number expressed by the first

digits of

x and

. Thus

besides

Assume now that there are given two numbers

,

. By expressing them as in (

5),

thus by division there are quotients

and remainders

,

such that

From Equation (7),

by substracting (

8) from (

6)

hence from (

4)

and this last inequality entails

, consequently the radix-

R expression of

q and

coincide up to the

-digit.

In summary:

Lemma 1. If , , for any the quotients and coincide up to the -digit.

Thus, in Chebyshev encryption scheme the precision m, which is the number of significant digits in the arithmetical calculations within the interval , shall be greater than the length ℓ of plaintexts since in the decryption process a division is involved. However, due to Lemma 1, for any the recovered plaintext is plaussible up to the -th digit. In order to determine the original plaintext the decipherer should know ℓ.

In an attack to the cryptosystem, given a public key

and the ciphertext

, the random index

such that

should be recovered and the plaintext should be

consisting of

m digits where

m is the precision of calculations. The original plaintext shall be the

ℓ-length prefix

of

. Thus a bruteforce procedure to recover

ℓ is to look for the first length

ℓ such that

. According to (

3) the cost in time of this procedure is

It is worth to mention that in this consecutive search, for some tested lengths Bergamo’s attack, presented below, fails because the conditions stated in

Section 3.2.1 are not satisfied.

3.2. Bergamo’s Attack

Let us recall first some basic facts of number theory.

3.2.1. Solving Linear Equations in Remainder Rings

Let be a modulus greater than 1 and consider the equation , with .

3.2.2. A number Theory Problem

Consider the following

We consider in particular the case in which the following condition holds:

Assume that

with

. Then

, and this last equation is stated over

. By writing

and

the equation is equivalent to

In fact:

Hence the sign in the right side of (

11) is not relevant and just an equation in (

9) may be considered.

As mentioned in

Section 3.2.1, if

then the unique solution of (

11) is

in

. If

and

, only when

the Equation (

11) can be solved and its

d solutions are given as

,

.

In summary:

Remark 3. With above notation, eq. (11) has solutions if where , and d is the number of solutions.

If we deal just with rational numbers in then for any radix any such rational number has a periodic R-representation. But for any pair of rational numbers there is a radix such that those numbers have finite representations for that radix.

Remark 4. Whenever , a radix R may be found such that for the main problem, for some length .

Proof. For a rational number , with , , and a radix , let and . For any current index i let be the minimum power such that and . Then with and . Thus, the radix-R expression of the rational number consists of 0’s except that at each entry there appears the digit . Since the remainder sequence takes values on the finite set , it is eventually periodic and so is the digit sequence . Clearly, the length of the period will be bounded by the denominator b; and if there is an index i such that then . Obviously, for such an index exists. □

3.2.3. The Attack

Each Chebyshev polynomial may be written as .

Given the public key of Alice, the attacker, Eve, looks for such that , then she evaluates and she recovers the plaintext as .

Remark 5.

Proof. Indeed, let .

Assume

and that for some

,

(the case in which

is similar because cos is an even function). Then

Assume

, then

and necessarily

. □

Let

and

. We may calculate arccos by its Taylor series [

15]:

Eve’s goal consists in recovering

such that

or in an equivalent form we have:

Thus, Eve’s goal (

13) is an instance of the main problem (

9) and it can be solved, by the method seen in

Section 3.2.2.

As a final remark in this section we point out that if

are solutions of (

12), then for a sign

,

4. Experiments

We have used the Multiple Precision Arithmetic provided by gmp: the gnu Multiple Precision Arithmetic Library, operating on signed integers, rational numbers, and floating-point numbers. The main used function categories and data structures are mpz, the high-level signed integer arithmetic structure, and mpf, the high-level floating-point arithmetic structure. The used version is gmp 6.3.0.

When dealing with Bergamo’s attack, we used the High Performed Trigonometric Function provided by mpfr: the gnu Multiple Precision Floating-Point Reliable Library. The used version is mpfr 4.2.1.

The platform was a computer with a processor intel(r) core(tm) i7-10750H cpu @ 2.60ghz 2.59 ghz and 64-bit operating system ubuntu 22.04.3 lts.

The precision of any mpf structure from gmp, namely the number of digits in the decimal part of floating numbers, can be fixed in advance. Since , N digits precision shall be required by the built-in function mpf_set_default_prec(), where the function only supports argument with N a multiple of 20. Alternatively, N digits precision may be required by the built-in function mpfr::mpreal::set_default_prec(), for any integer N. Nevertheless, the arithmetic still loses digits beyond the specified precision.

In our experiments we use two precision parameters:

ℓ: number of digits to codify plaintexts, we will refer to this parameter as length, and

m: precision of arithmetical calculations in gmp and mpfr, we will refer to this parameter as precision by itself.

In order to get correct crypto operations, for any given length

ℓ, the secret keys

s and the random indices

r shall be bounded from above and the precision

m shall be bounded from below (see

Table 1 below).

4.1. A Numerical Example for Symmetric Block Ciphering

Let be the ascii simple message:

Hi! I’m Xiaoqi.

Nice to meet you! ^_^

consisting of 38 characters (there is a

Line Feed at the end of each row). We take

, and

as we discussed above in this example. Since

, we can split the message into 4 sections, 3 consisting of 12 characters and the last of 2 characters. Each

ascii symbol is a byte and we write it in bits. By concatenating these bit strings we codify the message by the following real numbers expressed in radix 10 with

“significant digits”:

With secret key:

we calculate the public key

where

In order to cipher, we consider the index

then

and by making

, for

, we obtain the following values for the second entries of the ciphertexts:

In order to decipher, we calculate the values

, for

, and we obtain the following values:

The original plaintexts are obtained by cutting at length

.

Remark 6.

In the stated Cryptographic Scheme based on Chebyshev polynomials two parameters are essential: ℓ which is thelength, or the number of significant digits of plaintexts, and m which is theprecision, or the number of correct digits in arithmetical calculations.

A rough estimation from

Table 1 is that for integer

k and secret key

, the precision

m must be greater or equal than

4.2. Using an Enveloping Technique for Large Plaintexts

Evidently a block ciphering of long plaintexts by this method is excessively inefficient. We may compose symmetric block ciphering with this method through the

OpenSSL library

EVP in order to envelop large plaintexts. We take

, and

in this example. For the private key:

we calculate the public key

where

and consider an

envelope_key

Then by selecting

we get the cipher of

ek as

with

and effectively

The envelope key

can be obtained by cutting the decimal representations up to the

ℓ-th decimal digit.

4.3. A Numerical Example for Bergamo’s Attack

We try here the same example that illustrates the attack in [

1]. It is proposed to take:

Secret key.

Public key. For

, take

hence

is the public key.

Random exponent for ciphering.. Hence

Ciphertext. For any plaintext

the ciphertext is

However these calculations are purely symbolic. All angles involved in above calculations are irrational numbers, hence when dealing with them with a computer we just have approximations to their values. For instance, up to 8 digits, we have

then

consequently

is comparable with

. Indeed, for the current example

obviously the calculation of Chebyshev polynomials is highly sensitive to small errors, they are ill-conditioned. In this situation using the numerical approximations we have

Then the attacker Eve should solve the problem (

13) with

in decimal representation, namely with radix

, where those coefficients are obtained according to the relations stated before problem (

13).

Suppose that the values (

15) and (16) are cut up to the

m-th digit. According to the method described in

Section 3.2.2, condition (

10) does hold and consequently the problem is reduced to solve Equation (

11), which, by Remark 3, has solutions only when

We proposed 2 cases of different precision covering the 2 situations listed in the Bergamo’s algorithm that resulting the correct

, such that

Case . In this case the coefficients in Equation (

11) are

and

with

The unique solution of the corresponding instance of Equation (

11) is

Hence, the corresponding iteration

r such that

is

Comparing with the original index

, we get

Case . In this case the coefficients in Equation (

11) are

and

with

and the solutions of the corresponding instance of Equation (

11) are

and

.

Hence, there are four corresponding iterations

such that

and they are

Take

Comparing with the original index

, we get

While applying the symbolic compuation to

, yields it is indeed a correct solution:

Thus, for different values of

m it may happen that either there are no solutions of Equation (

11) (

) or there are several solutions (

and

). And as

m increases, the solution

increases as well. However, when

is much larger than

r, the calculations of Chebyshev polynomials may differ from that of the original index due to precision error propagation.

However, as reported in [

10], Bergamo’s attack succeeds by considering symbolic, not numerical, calculations:

Suppose that for some rational number

,

. Then according to the selection of coefficients

a,

b, as in Equation (

12),

, for a sign

, and

. Then by selecting a radix

R such that both

a and

b have finite

R-radix representation, as stated in Remark 4, Bergamo’s attack would succeed in recovering the index

r.

Besides the above example in which Bargamo’s attack may fail to recover the original index r, which is the random index when ciphering in Chebyshev chaotic cryptosystem, we also remark the following:

By considering the relation (

14), we have that the left side lies in the real interval

while the right side is the difference of two big numbers

, of the same order of magnitude. Depending on the chosen precision

m of the computing platform this difference can be great when the true values of the operands are approximated. Hence this difference may differ too much from the right side and that may provoke that for the alleged recovered index

r,

and consequently

.

5. Conclusions

Due to the chaotic behaviour of Chebyshev polynomials, the breaking attack in [

10] may fail if the length

ℓ, the number of significant digits, in plaintexts is unknown. Hence,

ℓ must be a part of the secret key. The precision

m, the number of significant digits in arithmetical calculations, may be part of the public key.

Author Contributions

G.M. proposed the experiments, X.L. made the implementations and performed the experiments. Writing the report was a joint task.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All c/c++ programs developed for the current experimentation are available https://github.com/ChillingLiu/Chebyshev-Polynomial-based-Cryptosystem.

Acknowledgments

These experiments were realized during the stay at the Guangdong Technion Israel Institute of Technology (GTIIT) of the second author as visiting professor. Dr. Morales-Luna kindly acknowledges the academic and administrative authorities of GTIIT for their hospitality and the great teaching and research environment in GTIIT.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kocarev, L. Chaos-based cryptography: a brief overview. IEEE Circuits and Systems Magazine 2001, 1, 6–21. [CrossRef]

- Kocarev, L.; Makraduli, J.; Amato, P. Public-Key Encryption Based on Chebyshev Polynomials. Circuits, Systems and Signal Processing 2005, 24, 497–517. [CrossRef]

- Mishkovski, I.; Kocarev, L., Chaos-Based Public-Key Cryptography. In Chaos-Based Cryptography: Theory,Algorithms and Applications; Kocarev, L.; Lian, S., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 27–65. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Liao, X.; Deng, S. A novel key agreement protocol based on chaotic maps. Information Sciences 2007, 177, 1136–1142. [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.; Kang, D.; Won, D. Improved Secure and Efficient Chebyshev Chaotic Map-Based User Authentication Scheme. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 15891–15910. [CrossRef]

- Kardaş, S.; Genç, Z.A. Security Attacks and Enhancements to Chaotic Map-Based RFID Authentication Protocols. Wireless Personal Communications 2018, 98, 1135–1154. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Yang, H. Image Encryption Algorithm Using Multi-Level Permutation and Improved Logisticc-Chebyshev Coupled Map. Information 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Yang, H. Image Encryption Using a New Hybrid Chaotic Map and Spiral Transformation. Entropy 2023, 25. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liao, X.; Xiang, T.; Zheng, H. Security analysis of the public key algorithm based on Chebyshev polynomials over the integer ring ZN. Information Sciences 2011, 181, 5110–5118. [CrossRef]

- Bergamo, P.; D’Arco, P.; De Santis, A.; Kocarev, L. Security of public-key cryptosystems based on Chebyshev polynomials. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers 2005, 52, 1382–1393. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, D. Security of Public-Key Cryptosystems Based on Chebyshev Polynomials over Z/pkZ. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs 2019, PP, 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Free Software Foundation. GMP: The GNU Multiple Precision Arithmetic Library. https://gmplib.org/, Viewed at 2024/12.

- Fousse, L.; Hanrot, G.; Lefèvre, V.; Pélissier, P.; Zimmermann, P. MPFR: A multiple-precision binary floating-point library with correct rounding. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 2007, 33, 13?es. [CrossRef]

- Cheong, K.Y. One-way Functions from Chebyshev Polynomials. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2012/263, 2012.

- WolframAlpha. ArcCos Taylor Series. https://www.wolframalpha.com/input/?i=taylor+series+arccos&lk=3, Viewed at 2024/12.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).