1. Introduction

Radiation shielding materials play a vital role across numerous fields, such as medical imaging and nuclear energy [

1], by reducing radiation exposure and protecting human health [

2]. Traditionally, materials with high atomic numbers, such as lead (Pb), have been widely used for radiation shielding due to their excellent attenuation properties [

3]. Lead, owing to its high atomic number and density, efficiently absorbs ionizing radiation, making it a common choice in shielding applications [

4]. However, its toxicity and adverse environmental impact have raised concerns, necessitating the development of safer, more sustainable alternatives [

5].

In radiation shielding research, various fillers like barium sulfate (BaSO₄) [

6], tungsten trioxide (WO₃) [

7], gadolinium oxide (Gd₂O₃) [

8] and bismuth oxide (Bi₂O₃) [

9] are frequently incorporated into polymer matrices due to their effective radiation attenuation properties. Studies indicate that silicone rubber with 70% BaSO₄ and Bi₂O₃ achieves a notable 90.19–97.48% radiation absorption at 120 kVp, offering a flexible, eco-friendly alternative for reducing diagnostic X-ray exposure [

10]. Additionally, flexible thermoplastic composites with tungsten-bismuth (W/Bi) and bismuth tungsten oxide fillers (20–100% ratios) have shown strong attenuation at X-ray energies of 80–120 kVp and gamma rays ranging from 59 to 960 keV, with W/Bi proving particularly effective due to superior attenuation coefficients and flexibility—ideal for medical radiation protection [

11]. In glass-based shielding, Gd₂O₃-doped samples (0–10 mol%) were evaluated for gamma (0.015–15 MeV) and neutron (0.5–10 MeV) shielding. The sample with 10 mol% Gd₂O₃ (GSNBC4) showed the highest gamma attenuation, while a higher B₂O₃ content (54.5 mol%) in GSNBC1 yielded the greatest neutron removal effectiveness [

12]. For natural rubber (NR) composites, gamma shielding comparisons between lead oxide (PbO) and Bi₂O₃ fillers revealed that NR/PbO composites offer enhanced tensile strength, while NR/Bi₂O₃ composites provide better oil resistance and thermal stability. Both types demonstrated excellent gamma shielding, surpassing concrete and haematite-serpentine [

13].

In recent years, researchers have sought alternatives that integrate non-toxic or eco-friendly materials [

14]. One promising strategy involves harnessing high atomic number elements found in natural waste products [

15]. The combination of these high atomic number elements, abundant availability, and low cost in certain natural wastes presents an innovative path toward developing sustainable radiation shielding materials [

16]. For example, composites derived from eggshells have demonstrated promise due to their high calcium content [

17], which, when ground into powder and mixed with a binder, provides shielding properties comparable to conventional materials [

18]. Similarly, waste-based materials such as rice husk ash and seashell composites are being explored for their effectiveness in radiation shielding applications that demand low-to-moderate protection levels [

19,

20]. "Beach debris" or "marine debris" includes human-made waste in coastal areas, such as plastics [

21], metals, glass [

22] and notably, coral fragments [

23]. Coral fragments, often remnants of coral reefs, can be affected by ocean acidification, warming, and physical damage [

24], but they also offer potential for innovative applications, like natural filtration [

25] or even sustainable materials for scientific research [

26]. Rich in calcium carbonate, coral debris has potential uses in construction [

27], water treatment [

28] and pharmaceuticals [

29]. Scientific research on coral debris provides insights into reef health and the effects of pollution, underscoring the need for effective waste management to protect marine environments [

30]. Integrating coral debris into broader environmental strategies highlights its value in conservation and pollution mitigation efforts [

31].

This study explores the development and characterization of epoxy-resin composites reinforced with coral-derived calcium carbonate fillers for enhanced radiation shielding. By leveraging the high-density and unique structural properties of calcium carbonate from coral, this research aims to create a sustainable and effective composite material for protecting against X-rays. The study examines the mechanical and radiation attenuation properties of these composites, aiming to provide a viable alternative to traditional radiation shielding materials in medical, industrial, and nuclear applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Material and Coral Processing

The epoxy resin used in this study was obtained from Resin Lab, Thailand. The resin consisted of diglycidyl ether of bisphenol A (DGEBA), a commonly used epoxy monomer due to its excellent mechanical properties, thermal stability, and adhesive characteristics [

32]. The coral fragments used in this study were sourced from a certified domestic supplier in Thailand (Lam Luk Ka Khlong 4 Market, Thailand), ensuring compliance with environmental conservation laws and regulations. These fragments were verified to originate from naturally degraded coral, without harvesting from ecosystems that could be adversely affected.

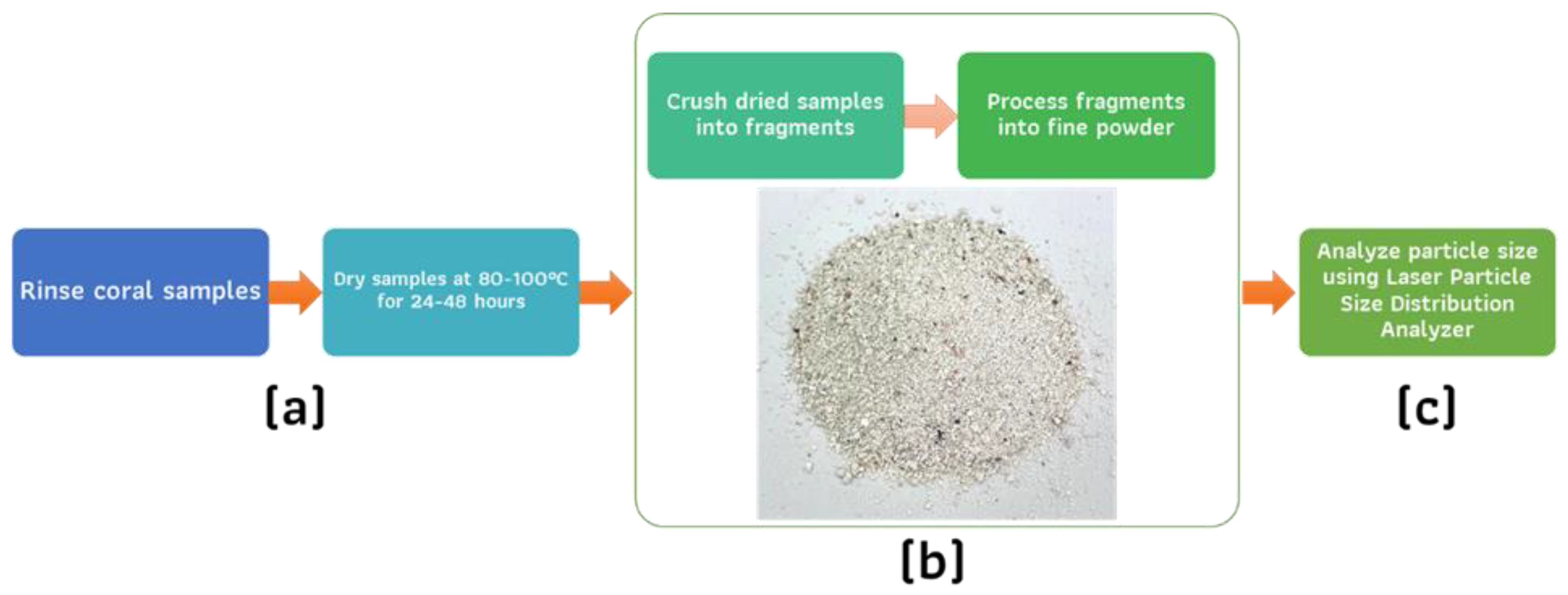

Figure 1 illustrates the preparation process for the coral samples. Initially, the coral samples were rinsed thoroughly with seawater to eliminate loose debris and marine organisms, ensuring a clean and uncontaminated starting material. Following this, the cleaned samples were dried in an oven at a controlled temperature range of 80–100°C for 24–48 hours to ensure complete removal of moisture. Once dried, the coral samples were mechanically crushed into smaller fragments using a crusher. These fragments were subsequently ground into a fine powder using a ball mill and pestle to achieve a uniform particle size. The particle size distribution (PSD) of the resulting coral powder was then analyzed using a Laser Particle Size Distribution Analyzer. This analysis provided precise data on the size range and uniformity of the particles, confirming their suitability for use in composite material applications.

2.2. Composite Material Preparation Involves Blending Coral Powder with Epoxy Resin

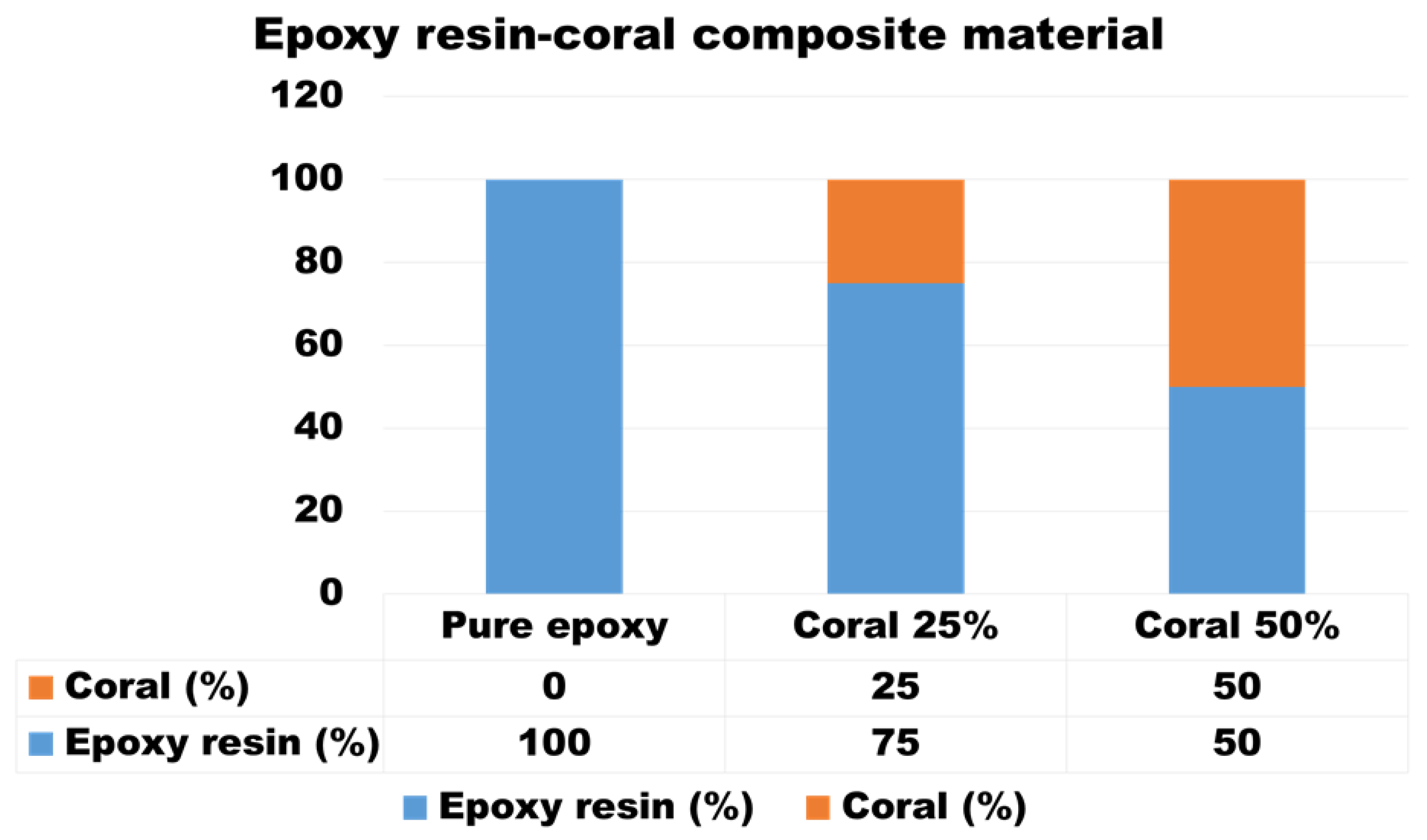

The preparation of the epoxy-resin matrix involved combining the epoxy resin with the hardener in accordance with the manufacturer’s specified guidelines. The required amounts of epoxy resin and hardener were precisely measured using a calibrated scale, adhering to the recommended 2:1 ratio by weight or volume. The necessary quantities of coral powder to achieve weight fractions of 0%, 25%, and 50% were calculated relative to the composite's total weight, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

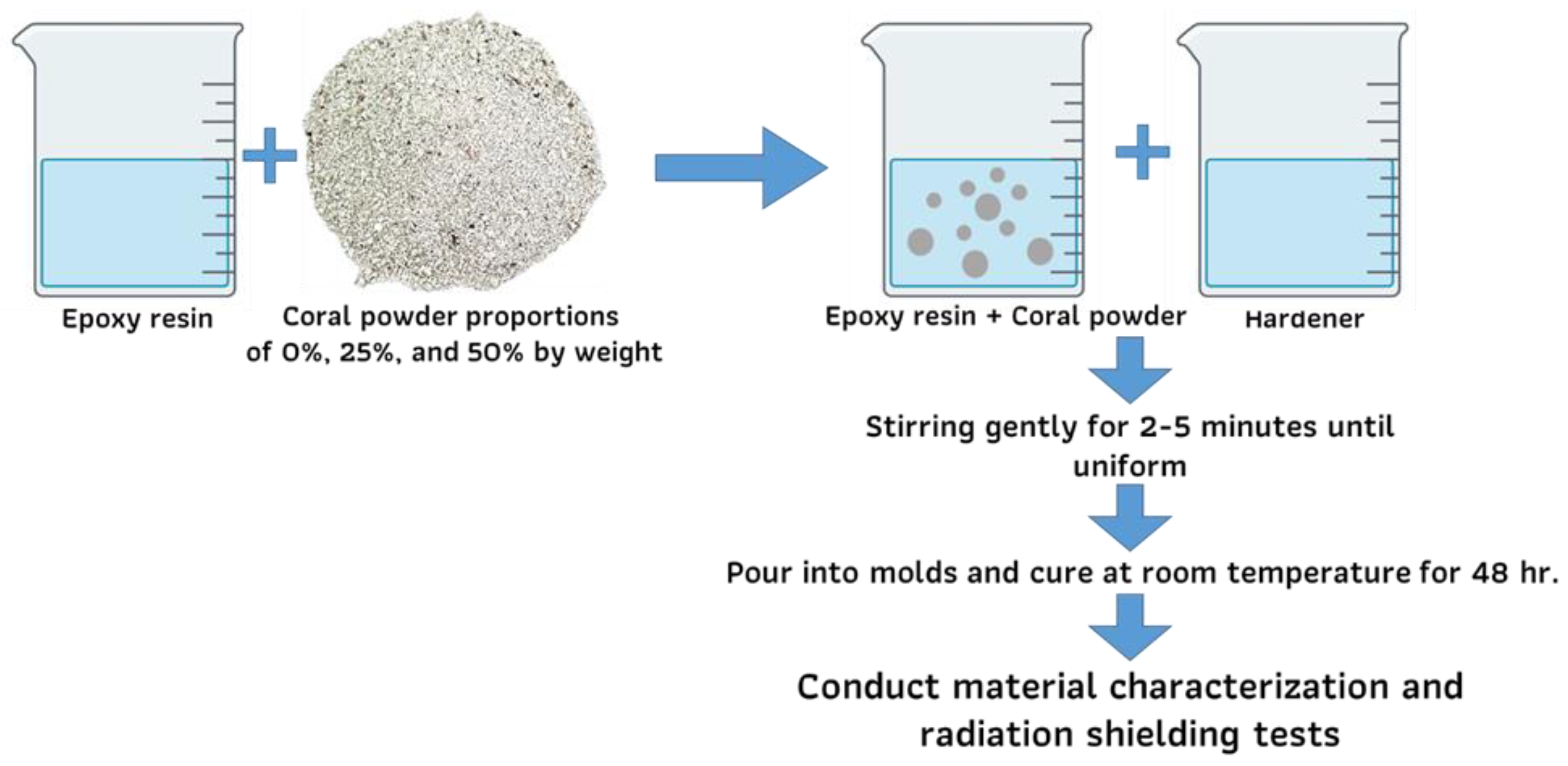

In a clean and contaminant-free container, the epoxy resin and hardener were mixed thoroughly by gentle stirring for 2–5 minutes until a uniform mixture was achieved. The pre-calculated coral powder was then gradually added to the mixture while using a mechanical stirrer to ensure homogeneity and prevent the formation of agglomerates. The mixing process continued for an additional 5 minutes to achieve a consistent distribution of the coral powder within the matrix. The prepared mixture was subsequently poured into molds and allowed to cure at room temperature for a duration of 48 hours. After curing, the samples were ready for further material characterization and radiation shielding performance evaluation, as detailed in

Figure 3.

2.3. Comprehensive Characterization of Epoxy-Resin Composites Reinforced with Coral-Derived Calcium Carbonate

A comprehensive characterization was conducted to evaluate the quality and performance of epoxy-resin composites reinforced with coral-derived calcium carbonate fillers. The analysis included the following techniques: X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) for elemental composition, Particle Size Distribution (PSD) analysis for assessing particle uniformity, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for examining surface morphology and microstructural features, and mechanical strength testing to determine the composites' tensile and compressive properties.

The raw materials utilized in this study are illustrated in

Figure 1b. The coral sample was analyzed for its elemental composition using Wavelength Dispersive X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) spectrometry with a Bruker S8 Tiger XRF spectrometer. Prior to analysis, the sample was prepared in powdered form, and the elemental composition was determined using theoretical formulas and fundamental parameter calculations. The results were presented in terms of oxide concentrations.

The particle size distribution (PSD) of the coral powder was assessed using a Laser Particle Size Distribution Analyzer (Model LA960V2). The sample was prepared by dispersing the coral powder in a liquid medium to achieve proper suspension and to minimize particle agglomeration. The analysis employed refractive indices of 1.658 for calcium carbonate and 1.333 for water. Instrument parameters were set with a circulation speed of 5 and an agitation speed of 7, while the ultrasound function was disabled. Transmittance values of 89.4% for the red channel (R) and 92.5% for the blue channel (B) were recorded, ensuring the optical reliability of the measurements during the PSD analysis.

The morphology of the samples was analyzed using a JEOL JSM-IT300 scanning electron microscope (USA) operating at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. The structural and dimensional characteristics of the samples, each measuring 1.0 × 1.0 cm², were investigated using the same SEM. To enhance imaging quality, the epoxy composite samples were sputter-coated with a thin layer of gold. Micrographs were acquired at magnifications of 500× and 2000×, providing detailed visualization of surface morphology and microstructural features. Furthermore, Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS) integrated with the SEM was employed for elemental analysis and mapping, enabling verification of calcium carbonate distribution and concentration within the epoxy matrix.

The mechanical strength of the samples was assessed through tensile testing performed on a TK-10TX tensile testing machine (BEMACS, Osaka, Japan), with a load capacity ranging from 1 to 10 tons. The samples were subjected to incremental tensile forces until failure, and key parameters such as Tensile Strength (MPa), Compressive Strength (MPa) and Flexural Strength (MPa) were recorded. These measurements provided a comprehensive evaluation of the tensile strength properties of the material.

2.4. Experimental Setup and Evaluation of Radiation Shielding Effectiveness

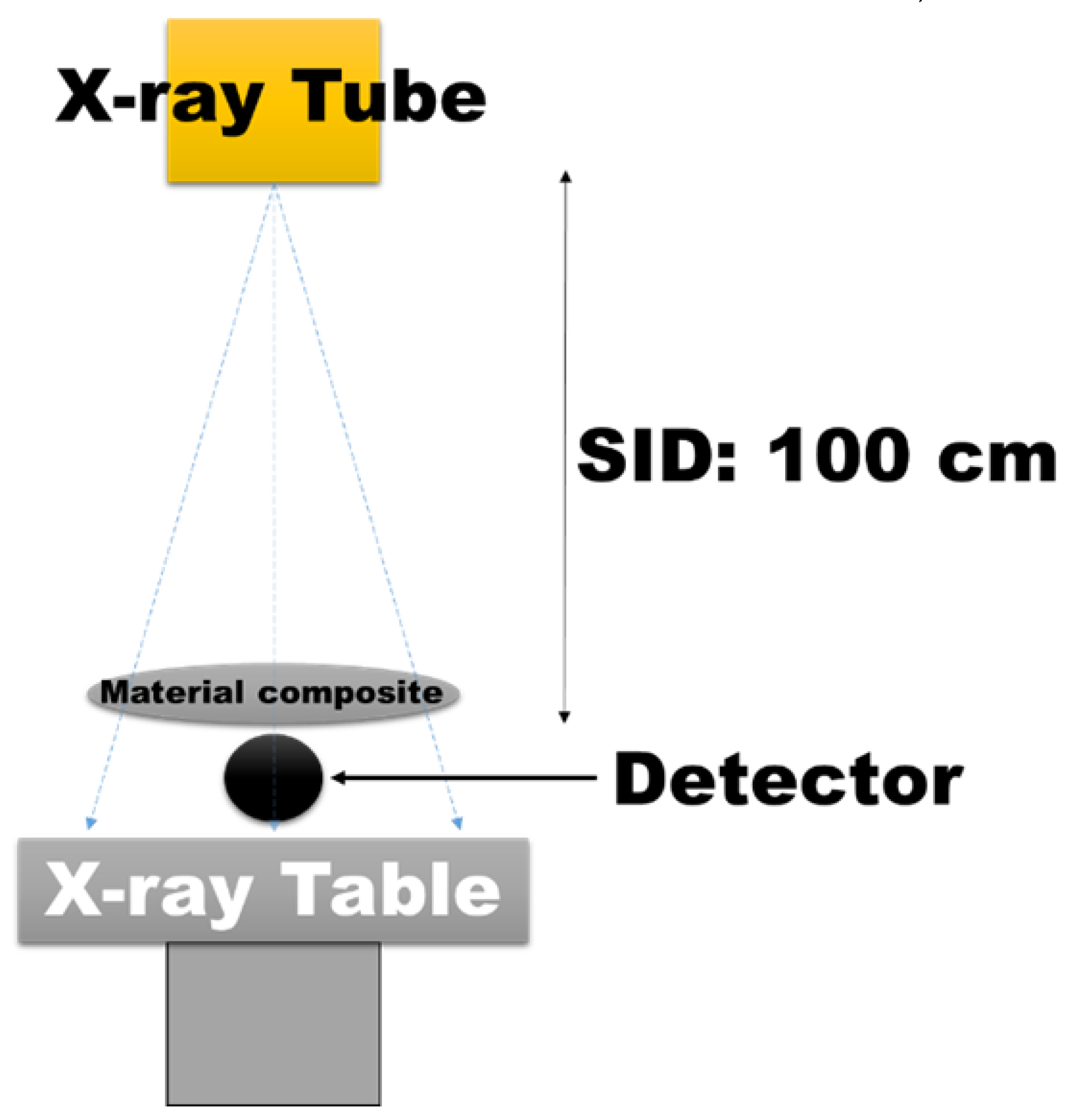

The experimental setup involved the use of a medical X-ray diagnostic unit (RADspeed Fit, Shimadzu Corporation, Japan) configured to operate at exposure parameters of 60, 80, 100, and 120 kVp with a fixed tube current of 5 mAs. The source-to-image distance (SID) was maintained at a constant 100 cm throughout the experiment. A Radcal AccuGold detector was positioned to fully encompass the X-ray beam output, ensuring complete coverage of the field size. Prior to conducting the tests, both the X-ray unit and the radiation detector were calibrated according to the manufacturers' guidelines to ensure accurate and reliable measurements, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

To evaluate the shielding properties of the tested materials, the percentage absorption of radiation dose (%Abs) was calculated using the following formula:

Where D

baseline is the radiation dose measured without shielding, and D

shielded is the radiation dose measured with the shielding material [

33].

The linear attenuation coefficient (

μ), representing the material's capacity to attenuate X-rays, was calculated using the exponential attenuation law:

where

I is the transmitted intensity,

I0 is the initial intensity and

x is the thickness of the shielding material [

10].

Additionally, the Half-Value Layer (HVL), which signifies the thickness of material required to reduce the X-ray intensity by half, was determined using the equation [

34]:

The parameters calculated, including percentage absorption (%Abs), linear attenuation coefficient (μ), and HVL, provided a comprehensive assessment of the shielding effectiveness of the tested materials. These metrics offer valuable insights into the material's potential for radiation protection applications.

3. Results

3.1. Elemental Composition of Coral Sample Analyzed by X-Ray Fluorescence

The analysis of the coral sample revealed a high calcium oxide (CaO) content, accounting for 51.60% by weight, which confirms the predominance of calcium as the primary component. This indicates the suitability of the coral material for applications requiring high calcium content, such as filler materials in composites. In addition to calcium oxide, the analysis identified magnesium oxide (MgO) at 1.06%, contributing to the structural properties of the material. Silicon dioxide (SiO₂) was detected at 0.66%, indicating the presence of trace silicate impurities that may influence the mechanical or chemical properties of the material. Other minor constituents included potassium oxide (K₂O) and sodium oxide (Na₂O), present in trace amounts in

Table 1. The comprehensive elemental profile underscores the potential of the coral-derived material in applications that leverage its calcium-rich composition while also considering the impact of minor elements on the overall material performance.

3.2. Particle Size Distribution (PSD) Analysis of Coral Powder

The particle size distribution (PSD) analysis of the coral powder sample provided detailed insights into its particle size characteristics. The D(v,0.1) value, representing the size below which 10% of the particles are distributed, was 315.75 µm. The median particle size, or D(v,0.5), was measured at 572.17 µm, indicating that half of the sample volume consists of particles smaller than this size. The D(v,0.9) value, which accounts for 90% of the particles, was recorded at 1206.94 µm. The mean particle size of the sample was calculated as 679.98 µm, reflecting the average size across the distribution in

Figure 5.

These results indicate a broad range of particle sizes, with the majority falling within the micrometer scale. The data demonstrates that the coral powder is well-prepared and suitable for applications where a consistent particle size distribution is essential, such as in composite materials. The findings also confirm the effectiveness of the preparation process in ensuring uniformity and reducing particle agglomeration.

3.3. Morphological Characterization of Epoxy-Resin Composites Incorporating Coral Powder at Varying Weight Fractions

The prepared epoxy-resin matrix was evaluated after incorporating coral powder at varying weight fractions of 0%, 25%, and 50%. As shown in the

Figure 6, the matrix without coral powder (0% weight fraction) exhibits a clear and transparent appearance, indicative of pure resin properties. At a 25% weight fraction of coral powder, the composite transitions to a slightly opaque texture, with visible fine particles uniformly dispersed throughout the matrix. When the coral powder content increases to 50%, the composite becomes fully opaque, with a dense distribution of coral particles, demonstrating significant filler integration.

These observations highlight the progressive impact of increasing coral powder content on the composite's visual and structural properties. The uniform dispersion of coral powder in the resin indicates successful mixing and integration, confirming adherence to the preparation methodology. The results provide critical insights into the composite’s morphological changes due to varying filler concentrations, which are essential for subsequent mechanical and functional evaluations.

3.4. Physical Characteristics of Coral Powder Sample Analyzed via SEM-EDS

The physical characteristics of coral powder incorporated into an epoxy-resin matrix at varying weight fractions (0%, 25%, and 50%) were evaluated using photographic and SEM-EDS analyses in

Figure 7. The results revealed significant changes in surface morphology and elemental composition as the coral powder content increased.

SEM imaging demonstrated notable variations in surface morphology across the samples. The control sample (0% coral powder) exhibited a smooth, homogeneous texture, indicative of pure epoxy resin. At 25% coral powder, dispersed coral particles were embedded within the matrix, forming localized clusters. The particles appeared irregular in shape, reflecting the granular nature of the coral material. In contrast, the 50% coral powder sample displayed a more heterogeneous structure, with densely packed particles, increased surface roughness, and evident agglomeration. These observations suggest that higher filler content disrupts the continuity of the resin matrix, potentially impacting the composite’s mechanical properties.

The addition of coral powder significantly altered the physical characteristics of the epoxy-resin matrix. While the 25% coral powder sample achieved relatively uniform dispersion and enhanced surface roughness, the 50% sample suffered from particle agglomeration, void formation, and reduced matrix homogeneity. These findings highlight the potential of coral powder as a filler material and underscore the need to optimize filler content to balance structural integrity and material performance.

The Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) analysis of the epoxy-resin matrix and coral composites with coral powder weight fractions of 0%, 25%, and 50%, as presented in

Figure 8, provided significant insights into the elemental distribution and compositional changes with varying filler content.

For the pure epoxy sample (0% coral powder), the elemental composition primarily consisted of carbon (C) and oxygen (O), with weight percentages of 81.24% and 18.55%, respectively, as shown in

Table 2. This distribution reflects the organic and polymeric structure of the epoxy resin. Trace amounts of silicon (Si) were detected at 0.21%, likely originating from additives or minor contaminants in the resin formulation.

In the 25% coral powder composite, a marked reduction in carbon content was observed (52.34%), along with an increase in oxygen content (23.18%). The addition of coral powder introduced new elements such as calcium (Ca, 7.55%), barium (Ba, 8.58%), and titanium (Ti, 2.81%), which are consistent with the mineralogical composition of coral. Additionally, minor elements including sulfur (S, 2.2%), magnesium (Mg, 0.26%), and aluminum (Al, 0.16%) were identified. These results confirm the successful incorporation of coral particles into the resin matrix.

In the 50% coral powder composite, further shifts in elemental composition were observed. The carbon content decreased to 46.69%, reflecting the increased dilution of the epoxy matrix due to the higher filler fraction. Oxygen levels rose to 31.79%, indicative of the oxygen-rich nature of coral. Calcium content slightly increased to 8.28%, while barium was no longer detected. Silicon (Si, 6.91%) and magnesium (Mg, 1.4%) concentrations were significantly higher compared to the 25% composite, suggesting the increased contribution of silica-based components from the coral powder. Potassium (K, 0.43%) and sodium (Na, 0.7%) were also newly detected, aligning with the mineral composition of coral and its interaction with the resin matrix.

The EDS findings are consistent with SEM observations, which revealed increasing coral particle agglomeration at higher filler contents. The greater diversity and concentration of elements such as Ca, Si, and Mg further validate the embedding of coral powder into the matrix and the associated shift in its physical and chemical properties. This analysis underscores the compositional transition from a predominantly polymeric epoxy matrix in the control sample to a mineral-enriched composite as the coral powder content increases. These findings highlight the potential of coral powder as a functional filler in composite materials, particularly for applications requiring specific elemental profiles.

3.5. Radiation Attenuation Properties of Epoxy Composites Reinforced with Coral-Derived Calcium Carbonate

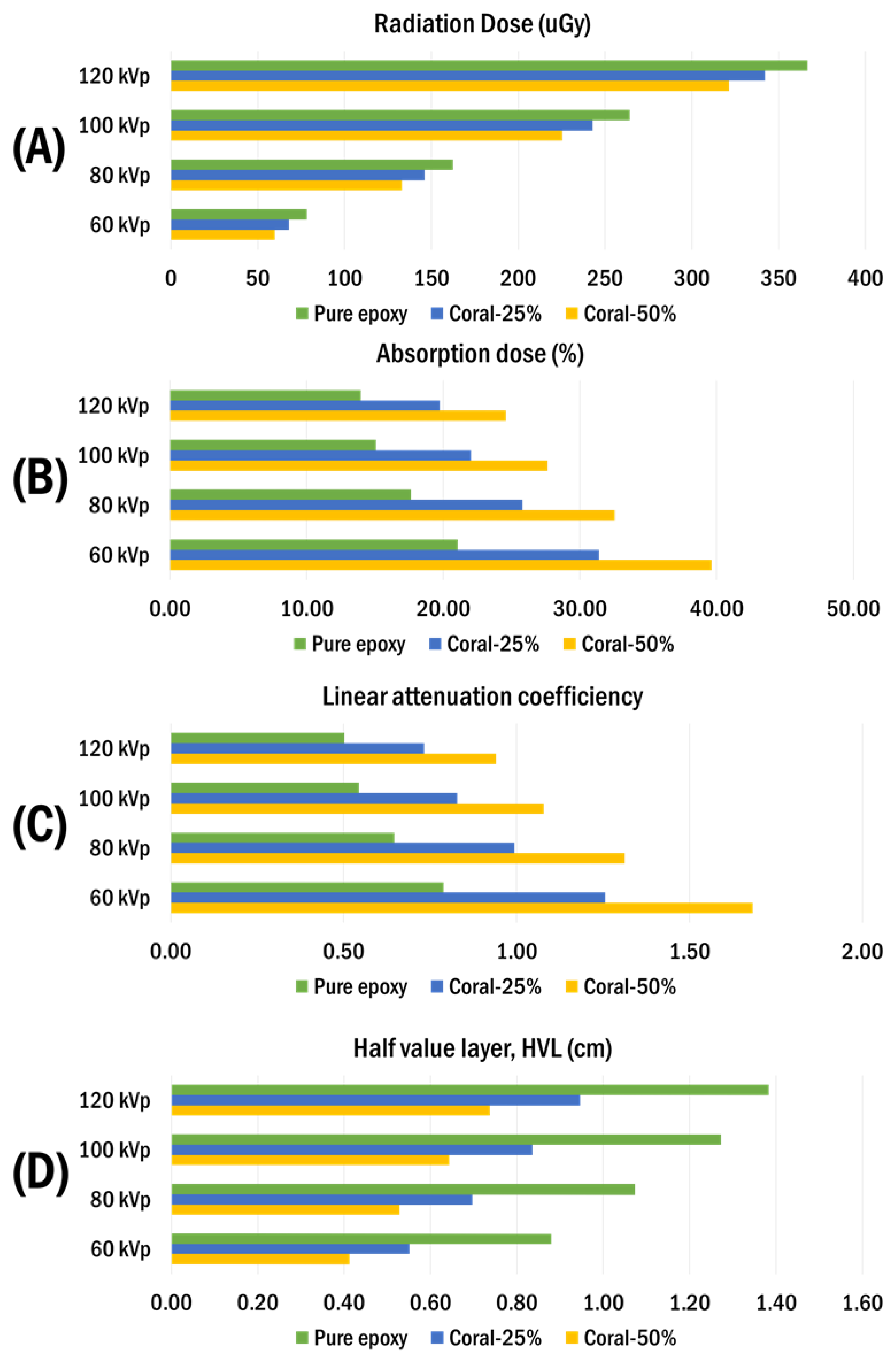

The radiation attenuation properties of epoxy composites reinforced with coral-derived calcium carbonate were assessed at varying filler concentrations (0%, 25%, and 50%) under different X-ray energy levels (60 kVp, 80 kVp, 100 kVp, and 120 kVp). The results, presented in

Figure 9, demonstrate a marked improvement in attenuation performance with increasing coral filler content.

For radiation dose measurements, the pure epoxy sample recorded the highest exposure values, ranging from 78.21 µGy at 60 kVp to 366.7 µGy at 120 kVp. In contrast, the composites containing 25% and 50% coral filler exhibited significantly reduced radiation doses. Notably, the 50% coral composite recorded doses as low as 59.81 µGy at 60 kVp and 321.5 µGy at 120 kVp (

Figure 9a).

Absorption dose analysis followed a similar trend, with the percentage absorption increasing with coral filler content. At 60 kVp, the pure epoxy sample achieved an absorption rate of 21.06%, while the 25% and 50% coral composites demonstrated improved absorption rates of 31.40% and 39.63%, respectively (

Figure 9b).

The linear attenuation coefficient values corroborated these findings, revealing enhanced attenuation performance with higher coral filler content. The pure epoxy sample exhibited the lowest coefficient (e.g., 0.79 cm⁻¹ at 60 kVp), whereas the 25% and 50% coral composites showed significantly higher coefficients of 1.26 cm⁻¹ and 1.68 cm⁻¹, respectively (

Figure 9c).

The half-value layer (HVL) measurements further highlighted the impact of coral filler addition on shielding performance. The HVL of pure epoxy was 0.88 cm at 60 kVp, which was reduced to 0.55 cm and 0.41 cm for the 25% and 50% coral composites, respectively (

Figure 9d). These reductions in HVL values reflect the improved attenuation efficiency of the coral-reinforced composites. In conclusion, the incorporation of coral-derived calcium carbonate into epoxy composites significantly enhances their radiation shielding properties. The results indicate that increasing the coral filler content improves attenuation performance, absorption capacity, and linear attenuation coefficients while reducing the HVL, making these composites promising candidates for radiation protection applications.

3.6. Comparison of Radiation Shielding Properties Between High Filler Coral-Derived Calcium Carbonate Composite and Lead

The radiation shielding performance of a high-filler composite containing 50% coral-derived calcium carbonate was evaluated in comparison to a standard lead apron (0.5 mm Pb equivalent, RayShield® USA) under 120 kV X-ray energy. The comparison focused on key parameters, including radiation dose, absorption efficiency, linear attenuation coefficient, and half-value layer (HVL), as summarized in

Table 3.

The lead apron exhibited superior shielding performance across all measured metrics. The radiation dose transmitted through the lead apron was 27.75 µGy, significantly lower than the 321.5 µGy recorded for the coral-derived composite. This substantial difference underscores the higher attenuation capacity of lead, achieving an absorption efficiency of 93.49%, compared to 24.57% for the coral-based composite.

The linear attenuation coefficient of lead was determined to be 5.46 cm⁻¹, markedly higher than the 0.94 cm⁻¹ observed for the coral composite. This higher coefficient reflects the exceptional capacity of lead to reduce X-ray intensity over a shorter path length. Consistent with this, the half-value layer (HVL) for lead was measured at 0.13 cm, significantly smaller than the 0.74 cm required for the coral composite. The lower HVL of lead highlights its superior density and atomic number, which contribute to its enhanced attenuation properties.

In conclusion, the lead apron demonstrated significantly greater radiation shielding efficiency compared to the coral-derived composite under 120 kV X-ray exposure. While the coral composite shows promise as an environmentally friendly, lead-free alternative, its current shielding performance is markedly inferior to that of conventional lead-based materials. Future efforts to optimize the formulation and structure of the coral composite could further improve its attenuation capabilities, potentially making it a viable option for specific applications requiring sustainable shielding materials.

3.7. Mechanical Properties for Epoxy-Resin Composites Incorporating Coral-Derived Calcium Carbonate

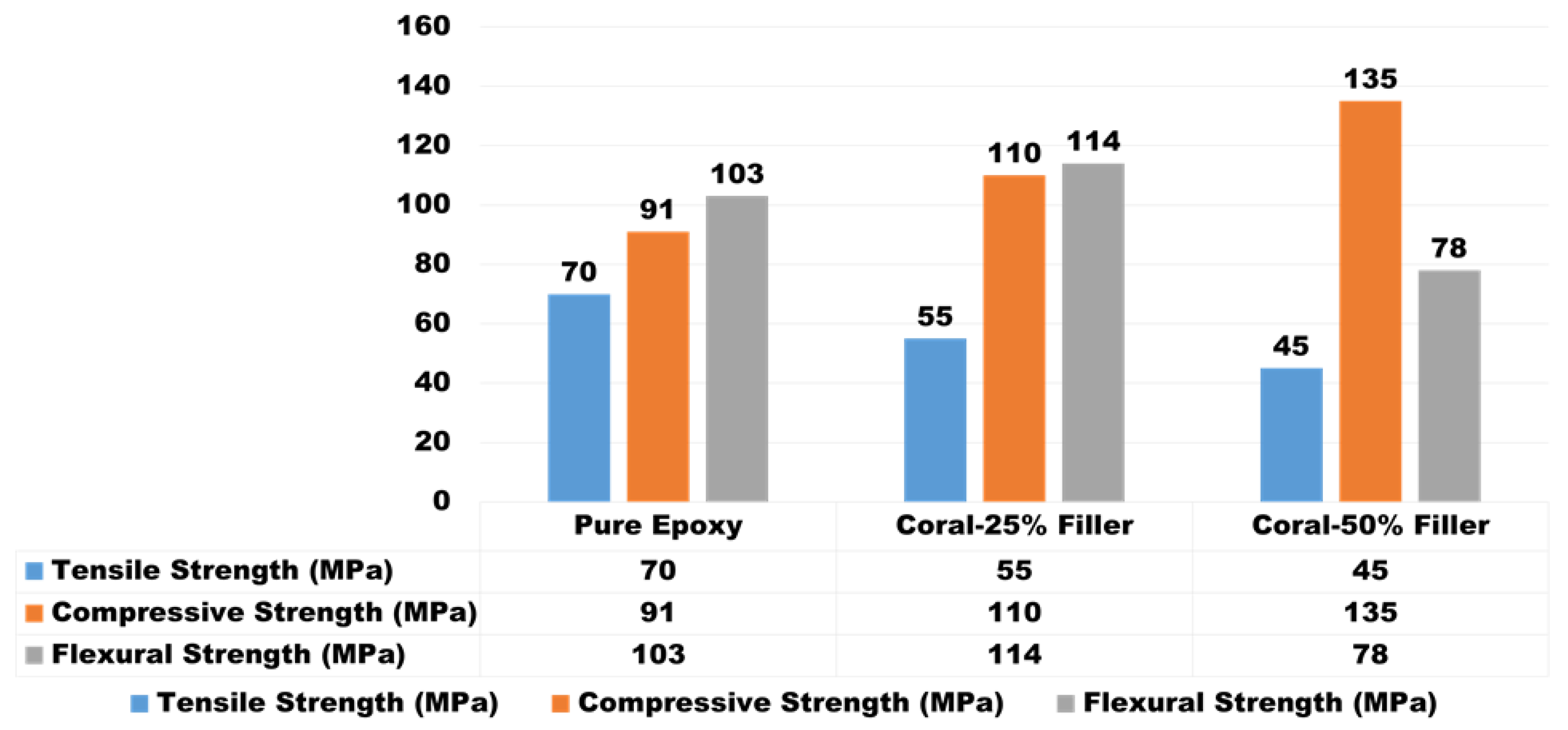

The mechanical properties of epoxy composites reinforced with varying weight fractions of coral-derived calcium carbonate fillers (0%, 25%, and 50%) were assessed in terms of tensile strength, compressive strength, and flexural strength. The findings, presented in

Figure 10, illustrate the impact of filler content on the mechanical behavior of the composites.

For tensile strength, the pure epoxy sample exhibited the highest value at 70 MPa, reflecting the cohesive and uninterrupted polymeric structure of the matrix. The addition of 25% coral filler reduced the tensile strength to 55 MPa, while increasing the filler content to 50% further decreased this property to 45 MPa. These reductions are attributed to increased brittleness and stress concentrations introduced by the dispersed filler particles within the matrix.

In terms of compressive strength, the pure epoxy sample showed a baseline value of 91 MPa. The incorporation of 25% coral filler enhanced this property to 110 MPa, and further addition to 50% filler increased the compressive strength to 135 MPa. This improvement can be attributed to the high-density coral filler particles, which reinforce the composite under compressive loads, increasing its load-bearing capacity.

For flexural strength, the pure epoxy sample achieved a value of 103 MPa, indicating its resistance to bending forces. The addition of 25% coral filler slightly improved flexural strength to 114 MPa, likely due to increased rigidity provided by the filler. However, at 50% filler content, the flexural strength decreased significantly to 78 MPa, reflecting a reduction in matrix flexibility and the increased brittleness associated with higher filler concentrations.

These results highlight the trade-offs inherent in increasing coral-derived filler content. While compressive strength improves significantly with higher filler percentages, tensile and flexural properties decline due to the brittleness and stress concentration effects of the fillers. These findings emphasize the importance of optimizing filler content to achieve a balance between mechanical performance and application-specific requirements.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study emphasize the significant benefits of utilizing coral-derived calcium carbonate as a functional material in composite applications. The high calcium oxide (CaO) content, measured at 51.60% by weight, underscores its potential as a structural filler. Calcium-rich fillers are well-documented for their ability to enhance the mechanical properties of composites, particularly in improving compressive strength and tensile performance, making them ideal for applications such as radiation shielding, construction, and biomedical devices [

35]. In terms of mechanical properties, the incorporation of coral-derived calcium carbonate significantly enhances the compressive strength of epoxy composites, a critical attribute for applications requiring materials capable of withstanding high compressive loads, such as structural panels or protective coatings. However, achieving a balance between filler content and flexibility is essential to maintain optimal performance, as observed in related studies on bio-based composite materials [

36]. The addition of calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) fillers influences the mechanical properties, including tensile, compressive, and flexural strength [

37] . While tensile strength decreases due to stress concentration points and potential weak interfacial bonding, compressive strength improves due to the rigidity of the CaCO₃ particles. Flexural strength, on the other hand, shows a complex relationship, improving at lower filler contents but decreasing at higher concentrations due to increased brittleness [

38,

39,

40].

The use of coral-derived calcium carbonate also aligns with sustainable development goals. Coral powder, sourced from naturally degraded coral in oceans, offers an environmentally friendly alternative to conventional materials such as lead, which pose toxicity and environmental risks [

41,

42]. Harvesting practices are regulated to minimize marine ecosystem damage, with a focus on collecting dead or eroded coral. This sustainable approach ensures the dual benefit of marine conservation and resource utilization [

43,

44,

45]. Additionally, coral’s calcium-rich composition and particle size distribution enhance its versatility in engineering materials, ensuring uniform dispersion and consistent mechanical performance in composite matrices [

46]. Trace elements such as magnesium and silica further expand its utility for specialized applications requiring unique chemical or structural characteristics [

47].

Coral-derived materials show considerable promise in radiation shielding applications. Although their attenuation properties are less effective than those of lead, coral-reinforced composites provide an environmentally friendly alternative for low-to-moderate shielding needs, such as in diagnostic radiology or protective barriers. These materials offer a safer option without the health risks associated with lead-based shielding, aligning with global trends toward sustainable radiation protection technologies [

48].

Despite these advantages, the study identified limitations in the material's performance. The reduced tensile strength at higher coral filler concentrations and the heterogeneous structure observed in the 50% coral composite—marked by particle agglomeration and matrix discontinuity—pose challenges for applications requiring high tensile and flexural performance. These findings align with similar studies on high-filler composites, which underscore the need for optimized dispersion techniques to enhance structural homogeneity and balance mechanical properties [

49]. Additionally, while coral fillers improve shielding efficiency, the attenuation remains lower than that of traditional lead-based materials, limiting applicability in high-radiation environments. The absence of long-term durability testing is another limitation, as it precludes a comprehensive understanding of the composite's performance under varying environmental and operational conditions.

Overall, this study highlights the broad potential of coral-derived calcium carbonate in composite applications, emphasizing its mechanical properties, sustainability, and radiation shielding capabilities. Future research should focus on optimizing the composite formulation through hybrid filler systems, surface modifications, and advanced processing techniques to address existing limitations and further expand the material’s applicability across diverse industries.

Future studies should focus on optimizing the particle size and distribution of coral fillers within the epoxy matrix to improve tensile properties while preserving compressive strength and radiation shielding efficiency. Investigating hybrid filler systems that combine coral-derived fillers with other sustainable materials, such as rice husk ash or seashell powder [

50,

51] may result in composites with enhanced multifunctional properties. Furthermore, conducting long-term durability and environmental testing is essential for evaluating the structural integrity and performance of these composites over time. Extending this research to explore the use of coral fillers in other polymer systems could further expand the potential applications of eco-friendly radiation shielding materials.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the potential of coral-derived calcium carbonate fillers as a sustainable and effective addition to epoxy resin for radiation shielding and structural support in composite materials. The results demonstrate that the incorporation of coral fillers enhances the compressive and flexural strength of epoxy composites, while achieving moderate radiation attenuation, particularly at higher filler concentrations. Although the shielding efficiency does not match that of conventional lead-based materials, these composites represent a viable alternative for applications prioritizing environmental sustainability, non-toxicity, and moderate shielding performance. The use of coral-derived fillers aligns with contemporary trends in sustainable material development, leveraging natural waste to create functional and eco-friendly solutions. Future research could focus on optimizing filler distribution and exploring hybrid material systems to enhance both mechanical properties and radiation attenuation capabilities. Overall, coral-enhanced epoxy composites offer a promising pathway toward safer and more environmentally conscious radiation shielding materials suitable for a variety of industrial applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, and visualization, Tochaikul, G., Tanadchangsaeng, N., Panaksri, A., & Moonkum, N.; writing—review and editing, Tochaikul, G. & Moonkum, N.; supervision, Tanadchangsaeng, N. & Moonkum, N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the research institute of Rangsit University.

Data Availability Statement

All the data are provided in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to Assoc. Prof. Manus Mongkolsul for their invaluable support and guidance throughout the course of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barbhuiya, S., et al., A comprehensive review of radiation shielding concrete: Properties, design, evaluation, and applications. Structural Concrete, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K., W. Cole, and G. Haase, Radiation protection in humans: extending the concept of as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA) from dose to biological damage. The British journal of radiology, 2004. 77(914): p. 97-99. [CrossRef]

- McCaffrey, J., et al., Radiation attenuation by lead and nonlead materials used in radiation shielding garments. Medical physics, 2007. 34(2): p. 530-537. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. and Z. Wang, Progress in Ionizing Radiation Shielding Materials. Advanced Engineering Materials, 2024: p. 2400855. [CrossRef]

- Flora, S.J., G. Flora, and G. Saxena, Environmental occurrence, health effects and management of lead poisoning, in Lead. 2006, Elsevier. p. 158-228. [CrossRef]

- Oglat, A.A. and S.M. Shalbi, An Alternative Radiation Shielding Material Based on Barium-Sulphate (BaSO4)-Modified Fly Ash Geopolymers. Gels, 2022. 8(4): p. 227. [CrossRef]

- Asemi, N.N., et al., Advancing gamma radiation shielding with Bitumen-WO₃ composite materials. Journal of Radiation Research and Applied Sciences, 2024. 17(4): p. 101143. [CrossRef]

- Li, R., et al., Effect of particle size on gamma radiation shielding property of gadolinium oxide dispersed epoxy resin matrix composite. Materials Research Express, 2017. 4(3): p. 035035. [CrossRef]

- Maghrabi, H.A., et al., Bismuth oxide-coated fabrics for X-ray shielding. Textile Research Journal, 2016. 86(6): p. 649-658. [CrossRef]

- Moonkum, N., et al., Evaluation of silicone rubber shielding material composites enriched with BaSO4 and Bi2O3 particles for radiation shielding properties. Materials Research Innovations, 2023. 27(5): p. 296-303. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., et al., A comparative study between pure bismuth/tungsten and the bismuth tungsten oxide for flexible shielding of gamma/X rays. Radiation Physics and Chemistry, 2023. 208: p. 110906. [CrossRef]

- Almousa, N., et al., Enhancing Radiation Shielding with Gadolinium (III) Oxide in Cerium (III) Fluoride-Doped Silica Borate Glass. Science and Technology of Nuclear Installations, 2024. 2024(1): p. 8910531. [CrossRef]

- Kalkornsuranee, E., et al., Mechanical and gamma radiation shielding properties of natural rubber composites: effects of bismuth oxide (Bi2O3) and lead oxide (PbO). Materials Research Innovations, 2022. 26(1): p. 8-15. [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, N., et al., Recent advances in eco-friendly and cost-effective materials towards sustainable dye-sensitized solar cells. Green chemistry, 2020. 22(21): p. 7168-7218. [CrossRef]

- Emsley, J., Nature's building blocks: an AZ guide to the elements. 2011: Oxford University Press, USA.

- More, C.V., et al., Polymeric composite materials for radiation shielding: a review. Environmental chemistry letters, 2021. 19: p. 2057-2090. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-z., et al., Integrating eggshell-derived CaCO3/MgO nanocomposites and chitosan into a biomimetic scaffold for bone regeneration. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2020. 395: p. 125098. [CrossRef]

- Tochaikul, G. and N. Moonkum, Development of Sustainable X-ray Shielding Materials: An Innovative Approach Using Epoxy Composite with Crab Shell, Eggshell, and Bone Waste. Radiation Physics and Chemistry, 2024: p. 111871. [CrossRef]

- Alrowaili, Z., et al., Radiation attenuation of fly ash and rice husk ash-based geopolymers as cement replacement in concrete for shielding applications. Radiation Physics and Chemistry, 2024. 217: p. 111489. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-C., Process technology for development and performance improvement of medical radiation shield made of eco-friendly oyster shell powder. Applied Sciences, 2022. 12(3): p. 968. [CrossRef]

- Pawar, P.R., S.S. Shirgaonkar, and R.B. Patil, Plastic marine debris: Sources, distribution and impacts on coastal and ocean biodiversity. PENCIL Publication of Biological Sciences, 2016. 3(1): p. 40-54.

- Iñiguez, M.E., J.A. Conesa, and A. Fullana, Marine debris occurrence and treatment: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2016. 64: p. 394-402. [CrossRef]

- De, K., et al., Characterization of anthropogenic marine macro-debris affecting coral habitat in the highly urbanized seascape of Mumbai megacity. Environmental Pollution, 2022. 298: p. 118798. [CrossRef]

- Allemand, D. and D. Osborn, Ocean acidification impacts on coral reefs: From sciences to solutions. Regional Studies in Marine Science, 2019. 28: p. 100558. [CrossRef]

- Baino, F. and M. Ferraris, Learning from Nature: Using bioinspired approaches and natural materials to make porous bioceramics. International Journal of Applied Ceramic Technology, 2017. 14(4): p. 507-520. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.-h., et al., Recycling coral waste into eco-friendly UHPC: Mechanical strength, microstructure, and environmental benefits. Science of the Total Environment, 2022. 836: p. 155424. [CrossRef]

- He, Z., et al., Utilization of recycled coral sand and aluminum scraps in foam concrete: Preparation, insulation of environmental noise and heat, and pore structure. Journal of Building Engineering, 2024. 95: p. 110153. [CrossRef]

- Herrán, N., et al., Calcium carbonate production, coral cover and diversity along a distance gradient from Stone Town: A case study from Zanzibar, Tanzania. Frontiers in Marine Science, 2017. 4: p. 412. [CrossRef]

- Karacan, I., et al., The synthesis of hydroxyapatite from artificially grown Red Sea hydrozoan coral for antimicrobacterial drug delivery system applications. Journal of the Australian Ceramic Society, 2021. 57: p. 399-407. [CrossRef]

- Corbin, C., The role of waste management in underpinning the Blue Economy, in The Caribbean Blue Economy. 2020, Routledge. p. 195-209.

- Nama, S., et al., Impacts of marine debris on coral reef ecosystem: A review for conservation and ecological monitoring of the coral reef ecosystem. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2023. 189: p. 114755. [CrossRef]

- Cao, L., et al., How a bio-based epoxy monomer enhanced the properties of diglycidyl ether of bisphenol A (DGEBA)/graphene composites. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 2013. 1(16): p. 5081-5088. [CrossRef]

- Moonkum, N., et al., Radiation protection device composite of epoxy resin and iodine contrast media for low-dose radiation protection in diagnostic radiology. Polymers, 2023. 15(2): p. 430. [CrossRef]

- Tochaikul, G., et al., Innovative radiation shielding material with flexible lightweight and low cost from shrimp shells waste. Radiation Physics and Chemistry, 2024. 225: p. 112162. [CrossRef]

- Dorozhkin, S.V., Calcium orthophosphates: applications in nature, biology, and medicine. 2012: CRC Press.

- Reichert, C.L., et al., Bio-based packaging: Materials, modifications, industrial applications and sustainability. Polymers, 2020. 12(7): p. 1558. [CrossRef]

- He, H., et al., Compressive properties of nano-calcium carbonate/epoxy and its fibre composites. Composites Part B: Engineering, 2013. 45(1): p. 919-924. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., et al., Study on mechanical property of epoxy composite filled with nano-sized calcium carbonate particles. Journal of materials science, 2005. 40(5): p. 1297-1299. [CrossRef]

- Rudawska, A. and M. Frigione, Aging effects of aqueous environment on mechanical properties of calcium carbonate-modified epoxy resin. Polymers, 2020. 12(11): p. 2541. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G., Y.-J. Heo, and S.-J. Park, Effect of morphology of calcium carbonate on toughness behavior and thermal stability of epoxy-based composites. Processes, 2019. 7(4): p. 178. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.L., et al., Malaysia’s progress in achieving the United Nations sustainable development goals (SDGs) through the lens of chemistry. Pure and Applied Chemistry, 2024(0). [CrossRef]

- Schileo, G. and G. Grancini, Lead or no lead? Availability, toxicity, sustainability and environmental impact of lead-free perovskite solar cells. Journal of materials chemistry C, 2021. 9(1): p. 67-76. [CrossRef]

- Bruckner, A.W., Advances in management of precious corals to address unsustainable and destructive harvest techniques. The cnidaria, past, present and future: The world of Medusa and her sisters, 2016: p. 747-786. [CrossRef]

- Carter, R.B., et al., Coral reef, water quality status and community understanding of threats in the eastern gulf of Thailand. APN, 2014.

- Wilkinson, C.C., Status of coral reefs of the world: 2004. 2004: Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS).

- Trinkūnaitė-Felsen, J., Investigation of calcium hydroxyapatite synthesized using natural precursors. 2014.

- Sinclair, D.J., Correlated trace element “vital effects” in tropical corals: A new geochemical tool for probing biomineralization. Geochimica et cosmochimica acta, 2005. 69(13): p. 3265-3284. [CrossRef]

- Ihsani, R.N., et al., Innovative radiation shielding: a review natural polymer-based aprons with metal nanoparticle fillers. Polymer-Plastics Technology and Materials, 2024. 63(6): p. 738-755. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, N., et al., Exploring Conductive Filler-Embedded Polymer Nanocomposite for Electrical Percolation via Electromagnetic Shielding-Based Additive Manufacturing. Advanced Materials Technologies, 2024: p. 2400250. [CrossRef]

- Putra, N.E., J. Zhou, and A.A. Zadpoor, Sustainable Sources of Raw Materials for Additive Manufacturing of Bone-Substituting Biomaterials. Advanced Healthcare Materials, 2024. 13(1): p. 2301837. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.A.M.M., et al., Exploring seashell and rice husk waste for lightweight hybrid biocomposites: synthesis, microstructure, and mechanical performance. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery, 2023: p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Preparation and analysis of coral samples: (a) Clean and dry samples, (b) Fragment and pulverize into fine powder, (c) Analyze particle size using laser-based distribution techniques.

Figure 1.

Preparation and analysis of coral samples: (a) Clean and dry samples, (b) Fragment and pulverize into fine powder, (c) Analyze particle size using laser-based distribution techniques.

Figure 2.

Composition distribution of epoxy resin, hardener, and coral powder at 0%, 25%, and 50% Weight Fractions.

Figure 2.

Composition distribution of epoxy resin, hardener, and coral powder at 0%, 25%, and 50% Weight Fractions.

Figure 3.

Preparation process of epoxy-resin composite samples with calcium carbonate fillers.

Figure 3.

Preparation process of epoxy-resin composite samples with calcium carbonate fillers.

Figure 4.

Experimental setup for radiation attenuation measurements using a medical X-ray diagnostic unit and radcal accuGold detector.

Figure 4.

Experimental setup for radiation attenuation measurements using a medical X-ray diagnostic unit and radcal accuGold detector.

Figure 5.

Particle size distribution (PSD) of coral powder showing mean particle size of 679.98 µm.

Figure 5.

Particle size distribution (PSD) of coral powder showing mean particle size of 679.98 µm.

Figure 6.

Morphological appearance of epoxy-resin composites with 0%, 25% and 50% coral powder weight fractions.

Figure 6.

Morphological appearance of epoxy-resin composites with 0%, 25% and 50% coral powder weight fractions.

Figure 7.

SEM images of epoxy-resin composites incorporating coral powder at weight fractions of 0%, 25%, and 50% showing surface morphology at different magnifications.

Figure 7.

SEM images of epoxy-resin composites incorporating coral powder at weight fractions of 0%, 25%, and 50% showing surface morphology at different magnifications.

Figure 8.

SEM-EDS analysis showing electron images and elemental spectra of epoxy composites with 0%, 25%, and 50% coral powder.

Figure 8.

SEM-EDS analysis showing electron images and elemental spectra of epoxy composites with 0%, 25%, and 50% coral powder.

Figure 9.

Radiation Attenuation Performance of Epoxy Composites with Coral Fillers at 0%, 25%, and 50%: (a) %Absorption of Radiation Dose, (b) Linear Attenuation Coefficient (µ), and (c) Half-Value Layer (HVL).

Figure 9.

Radiation Attenuation Performance of Epoxy Composites with Coral Fillers at 0%, 25%, and 50%: (a) %Absorption of Radiation Dose, (b) Linear Attenuation Coefficient (µ), and (c) Half-Value Layer (HVL).

Figure 10.

Mechanical properties of epoxy composites with varying coral-derived calcium carbonate filler content.

Figure 10.

Mechanical properties of epoxy composites with varying coral-derived calcium carbonate filler content.

Table 1.

Elemental composition of coral powder sample analyzed by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy.

Table 1.

Elemental composition of coral powder sample analyzed by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy.

| Elemental Oxides |

Weight Percentage (%) |

| Calcium Oxide (CaO) |

51.6 |

| Magnesium Oxide (MgO) |

1.06 |

| Strontium oxide (SrO) |

0.77 |

| Silicon Dioxide (SiO₂) |

0.66 |

| Sodium Oxide (Na₂O) |

0.58 |

| Sulfur Trioxide (SO₃) |

0.4 |

| Aluminum Oxide (Al₂O₃) |

0.12 |

| Chlorine (Cl) |

0.09 |

| Phosphorus Pentoxide (P₂O₅) |

0.07 |

| Iron Oxide (Fe₂O₃) |

0.06 |

| Potassium Oxide (K₂O) |

0.03 |

Table 2.

Elemental composition of rure epoxy and coral composites (Wt%).

Table 2.

Elemental composition of rure epoxy and coral composites (Wt%).

| Element |

Pure Epoxy (Wt%) |

Coral 25% (Wt%) |

Coral 50% (Wt%) |

| C |

81.24 |

52.34 |

46.69 |

| O |

18.55 |

23.18 |

31.79 |

| Si |

0.21 |

1.8 |

6.91 |

| Mg |

- |

0.26 |

1.4 |

| Al |

- |

0.16 |

2.19 |

| S |

- |

2.2 |

- |

| Ca |

- |

7.55 |

8.28 |

| Ti |

- |

2.81 |

- |

| Fe |

- |

1.13 |

1.61 |

| Ba |

- |

8.58 |

- |

| Na |

- |

- |

0.7 |

| K |

- |

- |

0.43 |

| Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Table 3.

Comparison of radiation shielding properties between 50% coral-derived composite and lead (0.5 mm Pb equivalent).

Table 3.

Comparison of radiation shielding properties between 50% coral-derived composite and lead (0.5 mm Pb equivalent).

| Material |

Coral-50% |

Lead |

| Radiation Dose (uGy) |

321.5 |

27.75 |

| Absorption dose (%) |

24.57 |

93.49 |

| Linear attenuation coefficiency |

0.94 |

5.46 |

| Half value layer, HVL (cm) |

0.74 |

0.13 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).