1. Introduction

Memory types can be broadly divided into volatile and non-volatile memory. Volatile memory refers to memory in which stored data is erased when the external power supply is removed. The most common examples are SRAM and DRAM. SRAM has a faster read speed and low power consumption. In contrast to the six transistors required for each bit of data in SRAM, DRAM can process each bit using only one capacitor and one transistor. This implies that DRAM has greater capacity and density per unit volume, which results in a lower manufacturing cost [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

Non-volatile memory is commonly used to store information because the stored data is not erased when the external power supply is removed. Traditional non-volatile memory includes flash memory and ROM. However, traditional non-volatile memory has the disadvantages of slow read/write speed and slower reading speed. In recent years, new types of non-volatile memory have been developed that combine the advantages of volatile memory with non-volatile characteristics to improve their disadvantages. These memories feature faster read and write speeds, lower power consumption, and better read endurance. To date, the following four types of emerging volatile memories have been developed: magnetoresistive random access memory (MRAM), phase change random access memory (PCRAM), ferroelectric random access memory (FeRAM), and resistive random access memory (RRAM) [

15,

16,

17].

RRAM is currently the focus of much research attention because its structure uses a metal/insulator/metal (MIM) sandwich structure. The way this structure is overlapped can reduce the finished area and thus increase the memory capacity. Compared with other emerging memories, RRAM has the advantages of lower write voltage, faster read speed, and higher integration density. Another study indicates that the Al/Nd

2O

3/ITO structure can also facilitate the operation of Nd

2O

3 resistive memory at a high frequency and improve the switching ratio [

18]. In addition to the study of the dielectric layer, the contact between the metal and the dielectric layer in the MIM structure of the RRAM is also a key point of investigation, as it directly affects the characteristics of the RRAM. Currently, there is a significant body of research focusing on the effect of different electrode materials on the characteristics of RRAMs.

Recently, the supercapacitors exhibited two main categories concerning the charge storage devices mechanism, for the electric double-layer capacitors and pseudo-capacitors [

19,

20]. The high conductive and surface area carbonaceous materials were widely used as electrode materials in electric double-layer capacitors. Metal oxides exhibited the conducting polymers were tested for pseudocapacitive electrode materials. These were the electrode materials that determine the electrochemical performance of the supercapacitors. The neodymium element is an important rare earth material for applications in the electric vehicles, mobile phones, permanent magnets, windmills, high-speed rail, medical scanners, lasers, optical fiber data transmission, screen phosphors, banknote protection, catalysts for everything that supports our daily life. Additionally, the neodymium oxide (Nd

2O

3) material was an important naturally abundant and highly reactive element in rare earth metal oxides materials. It was widely also applications in the magnetic devices, the catalysts, and the dielectrics capacitor material. The neodymium oxide material were used for the conductive filler and to enhance the electrical properties in relation materials [

21]. Therefore, the neodymium oxide (Nd

2O

3) material has the opportunity to be used in supercapacitor applications, it was also might the opportunity to be used for same capacitor structure of RRAM memory devices in the future.

Because the neodymium oxide (Nd2O3) material was the characteristics of a high dielectric constant material, it might be opportunity used in CMOS integration circuit in the future. According to the latest 1T1R RRAM process integration technology, there was the opportunity that materials was able to applied to components in the same metal-insulator-metal (MIM) structure of the RRAM devices. There were still opportunities to integrate neodymium oxide materials integrated the CMOS manufacturing processes in the future.

Generally, for neodymium oxide (Nd2O3) thin films, the films of various material have defects, oxygen vacancies, and other problems after preparation as-deposited processing to be RRAM devices . Additionally, a rapid thermal annealing process and a general furnace tube annealing process were usually to improve the electrical and relation properties. However, the annealing process requires a long cost and high temperature time. In our previous research, we successfully proposed a low-temperature supercritical technology method to improve defects in neodymium oxide (Nd2O3) film processing. The defects and oxygen vacancies of non-treated neodymium oxide thin films for different oxygen concentration parameters were also effectively achieved and improved by the of supercritical carbon dioxide fluid treatment. Therefore, to choice the different top/bottom electrodes and electrical transferred conduction mechanisms will be the focus and direction of our research.

To discuss the oxygen concentration distribution effect in oxygen-rich ITO electrode, the ser/reset voltage of neodymium oxide films RRAM devices for different ITO electrode thickness were discussed and investigated. Additionally, the extremely different set voltage might be discussed form the electric field concentration effect at the tip of the RRAM resistance wire and the oxygen ion concentration distribution effect. Finally, we varied the different thickness ITO electrode to illustrate the influence of different electrode materials on bipolar switching characteristics for neodymium oxide films resistance random access memory devices on the set voltage mechanism [

22].

3. Results and Discussion

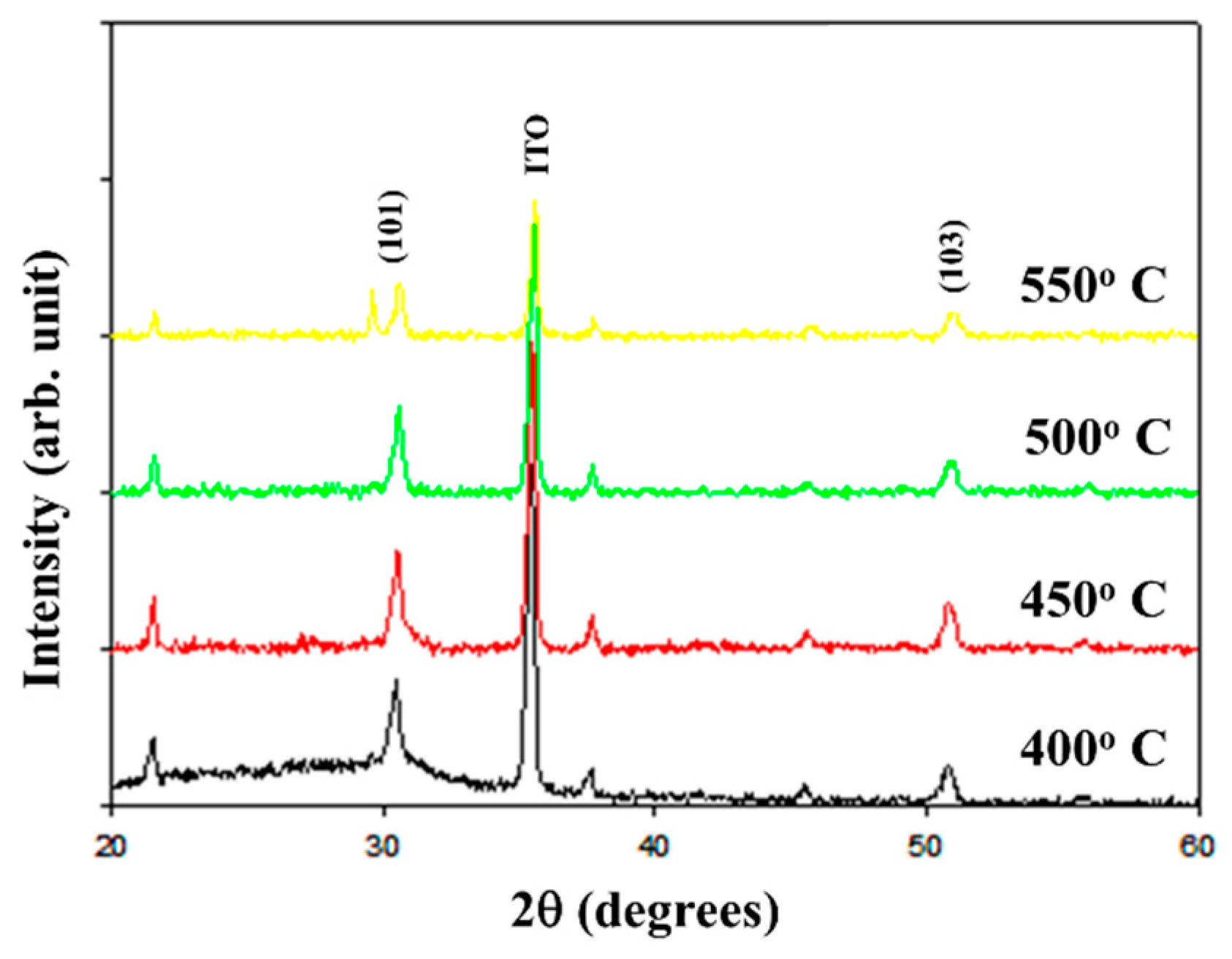

Figure 1 depicts the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the (101) and (103) preferred peaks of the as-deposited neodymium oxide films subjected to different annealing temperatures. It can be observed that all the films exhibited a polycrystalline structure irrespective of the annealing temperature applied.

The smallest full width at half maximum (FWHM) value for the (101) and (103) preferred peaks of the neodymium oxide films at different annealing temperatures was measured. The crystallinity and grain size of the neodymium oxide films prepared using an annealing temperature of 450°C exhibited the smallest FWHM value relative to the other temperature treatments. In addition, a smaller peak FWHM exhibits better crystallinity. FWHM(101) was 0.18 for an annealing temperature of 450°C. After calculation, the crystallinity was found to be 97.02% and grain size of 30nm. Comparing the those results, the crystallinity of the annealing temperature of 450°C is better. The grain size was then calculated by the Debye–Scherrer formula equation, the error of the measured parameters was about 3–5%. The grain size and the crystallinity of the neodymium oxide films was also proved in

Figure 2. Rapid thermal processing (RTP) was a semiconductor manufacturing process which heating relation material films to temperatures above 1,000°C for not more than a few seconds. These processes were used for a wide variety of applications in integrated circuit manufacturing including dopant activation, thermal oxidation, defect structure, oxygen vacancy concentration, and device performance.

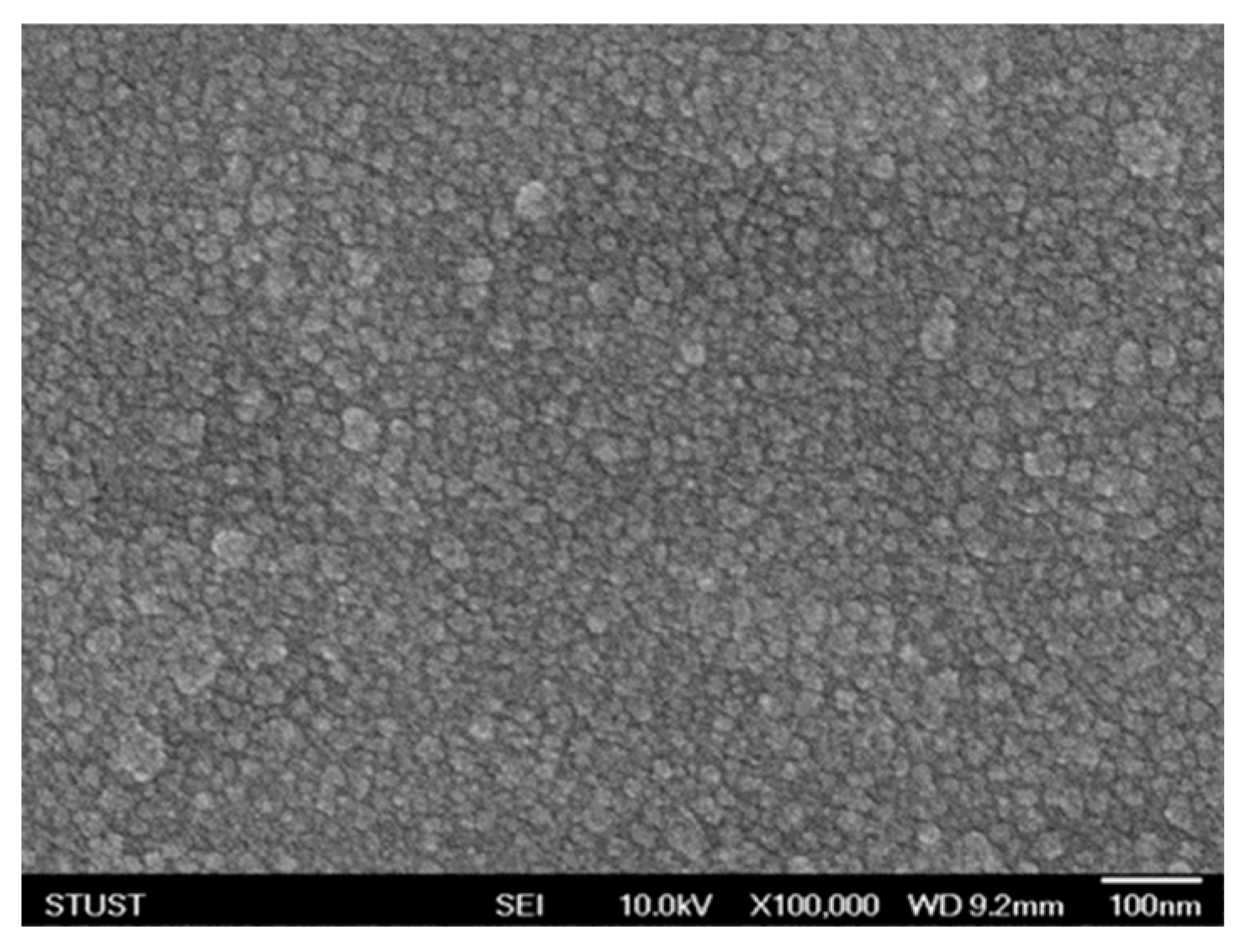

The microstructure of the neodymium oxide films of the RRAM devices was observed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to examine the surface morphology. The specimens of films exhibited a thickness of approximately 15 nm and displayed a dense and uniform grain structure. Additionally, circular plates and oval grains were observed. As illustrated in

Figure 2, the microstructure and grain size of the neodymium oxide films subjected to annealing at 450°C exhibited a predominantly round or circular morphology. The grain size of the neodymium oxide films was found to be approximately 30 nm. In a previous study, the grain growth, dielectric loss, and leakage current properties of non-treated films exhibited notable improvement when subjected to different oxygen annealing treatments. Moreover, the annealing process led to a reduction in the number of traps and vacancies in the films, which in turn resulted in a notable decrease in the leakage current density.

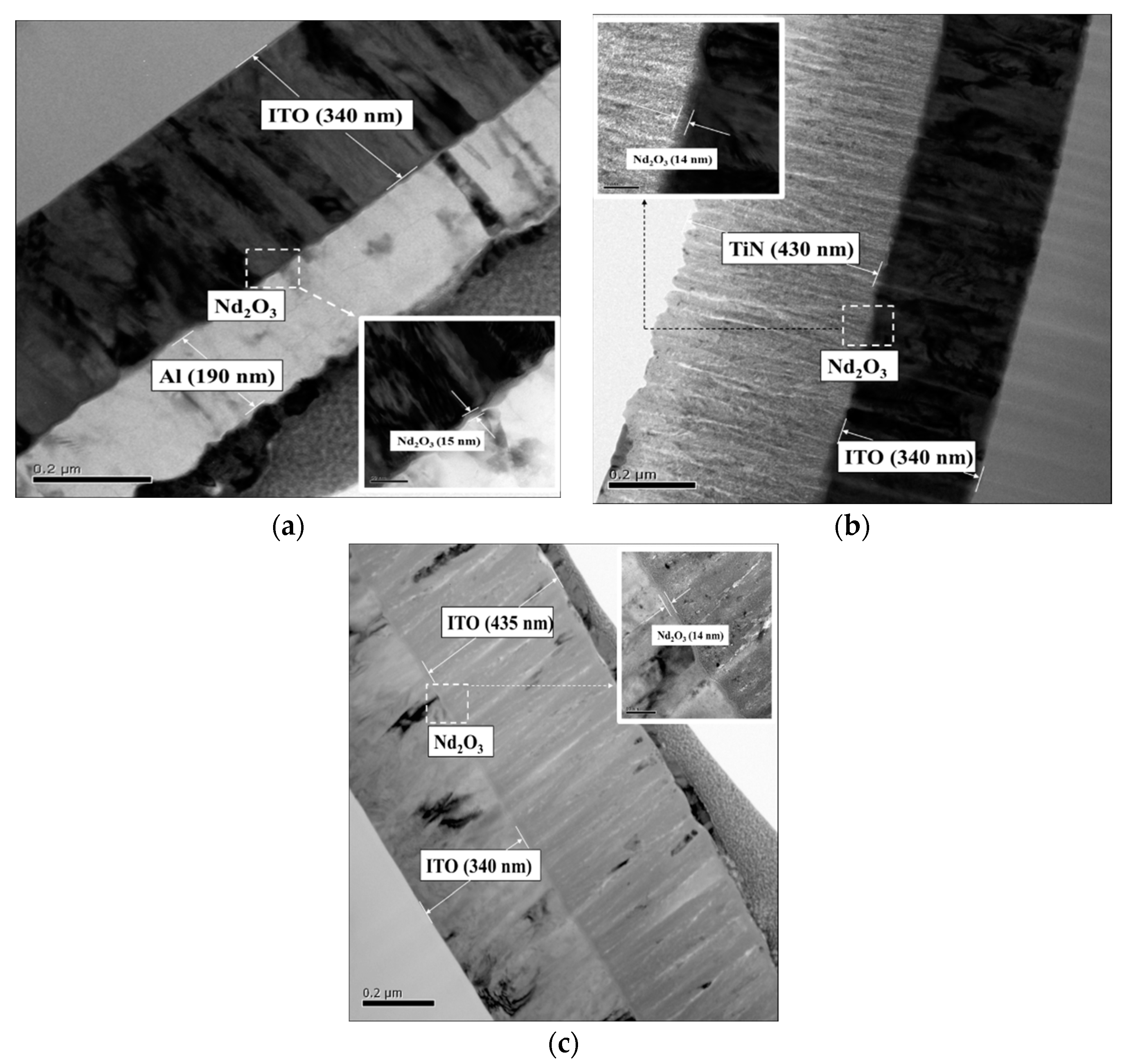

Figure 3 presented the images and cross-sectional structure obtained by the transmission electron microscope(TEM), the Philips Tecnai G2 F20 (FEG-STEM).

Figure 3 depicts the cross-section of the neodymium oxide films of the RRAM devices for the various top electrode materials (Al, TiN, and ITO). The thicknesses of the Al (top electrode), the neodymium oxide films, and the ITO substrate of the RRAM devices were approximately 190 nm, 15 nm, and 340 nm, respectively (Top left). The TiN and ITO top electrodes of the RRAM devices exhibited thicknesses of approximately 430 nm and 340 nm, respectively (top right and bottom left). Subsequent observations and measurements of the

I-V curves to determine the electrical conduction mechanism of the neodymium oxide films revealed their significance for applications in nonvolatile RRAM devices (bottom right).

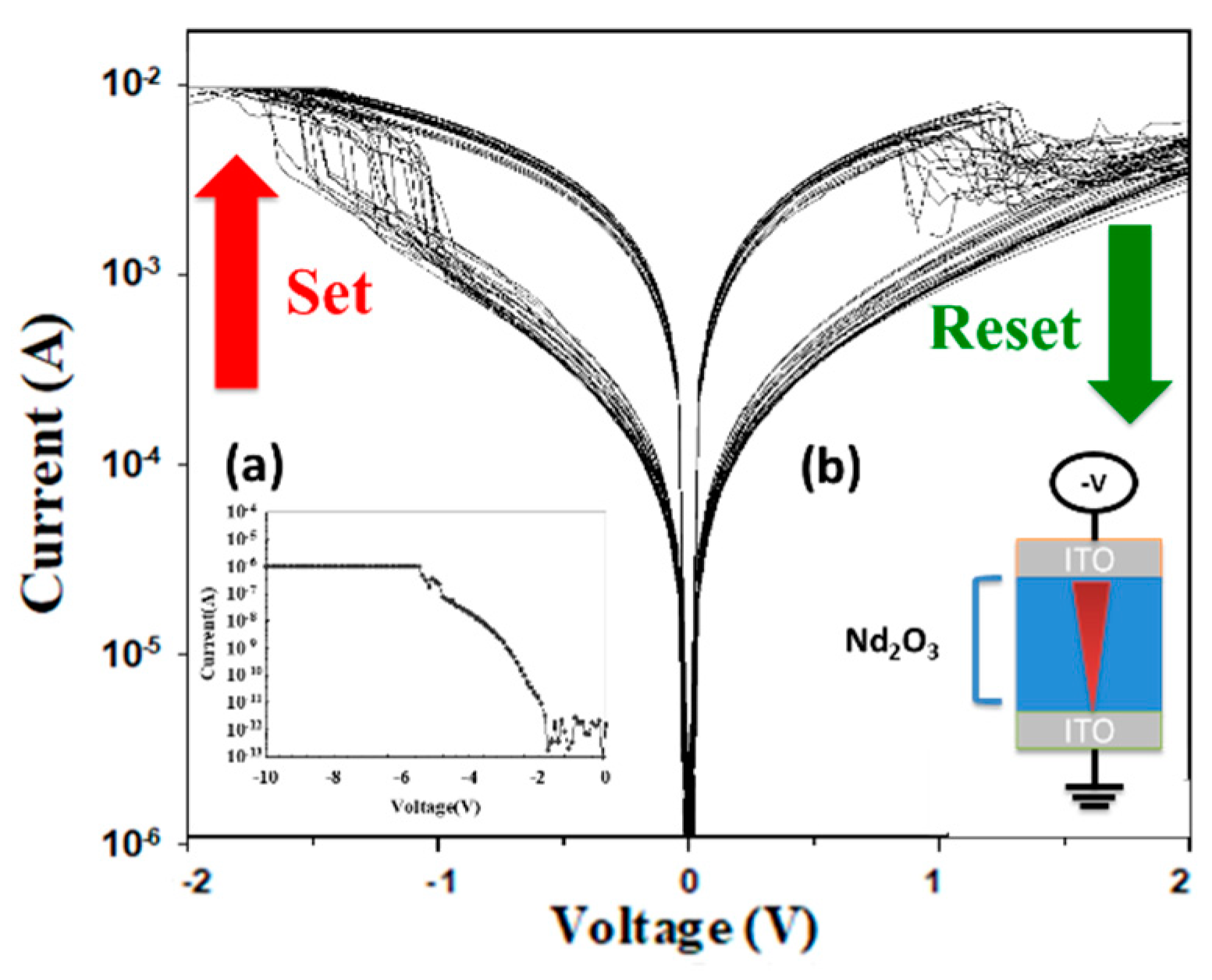

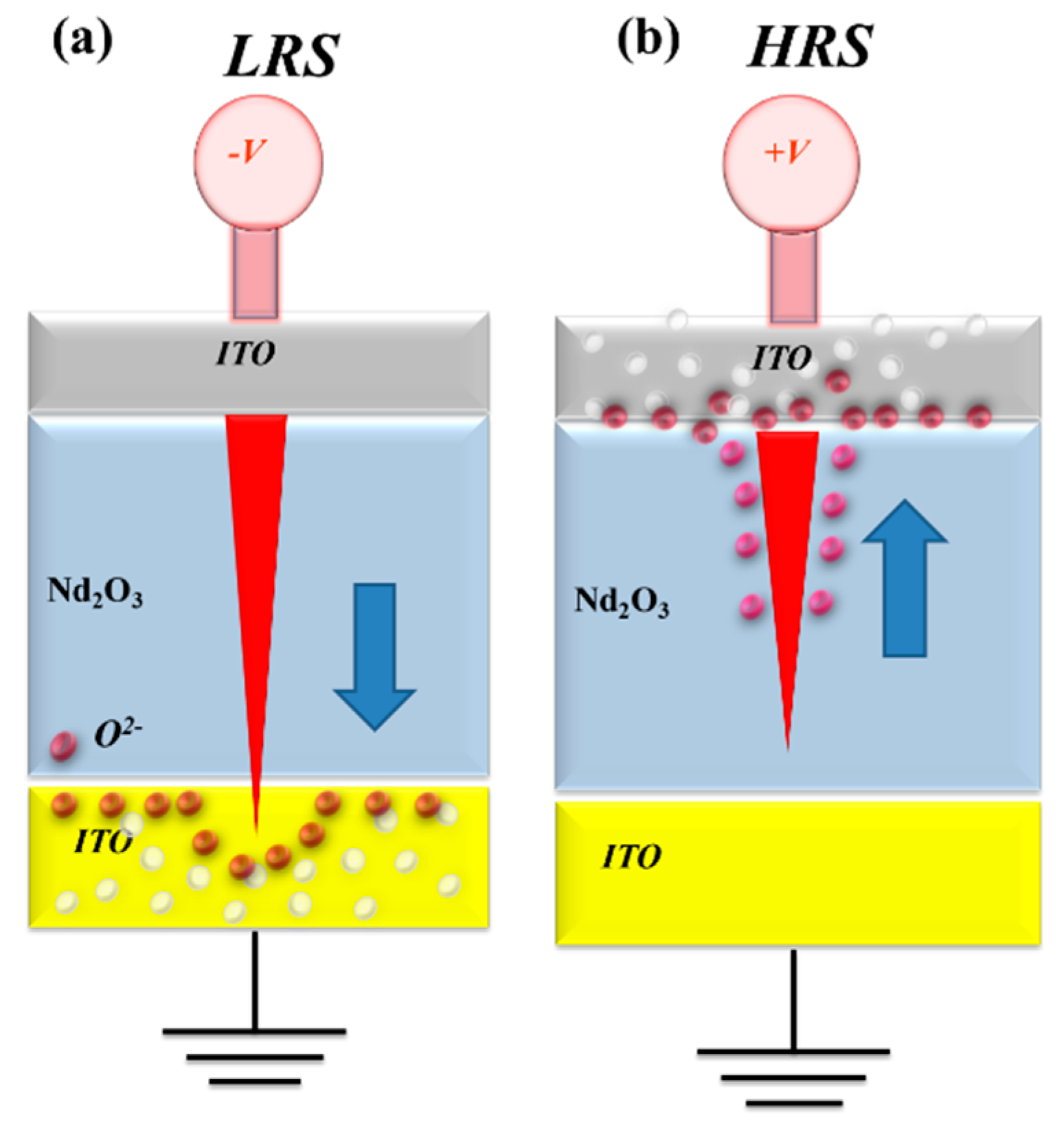

The properties of the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices with the initial forming process at the set and reset states are illustrated in

Figure 4. As illustrated in

Figure 4a, the current compliance was 10 mA. The initial forming process was conducted at a voltage of approximately 6 V. In the set process, the neodymium oxide films RRAM device was transferred to the low resistance state (LRS), whereby a high positive bias was applied in excess of the set voltage during set and reset processing. In the reset process, the operation current exhibited a continuous decrease from the low resistance state (LRS) to the high resistance state (HRS) when a negative bias was applied over the reset voltage. To obtain a stable

I-V operating switching condition, the set and reset processes of the neodymium oxide films of the RRAM devices were repeated 100 times.

Figure 4 shows the

I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices with the initial forming process or an ITO/films/ITO structure, based on 100 measurements. The set and reset voltages of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device for a 10mA compliance current were approximately 1.5V and -1.5V, respectively. As illustrated in

Figure 4(a), the breakdown voltage of the initial forming process was -6V.

To explore the electrical conduction behavior of the initial metallic filament forming conduction, the Ohmic conduction and hopping conduction mechanism were determined by

I-V and ln

I–V1/2 curve fitting. To calculate the

I-V curve, the Ohmic conduction mechanism equation was transformed from the

I-V curves fitting the RRAM devices. For the Ohmic conduction,

where

Eac is electron activation energy,

is the carrier mobility,

E is applied electrical field,

n is the electronic concentration, k is the Boltzmann constant, T is absolute temperature.

In addition, to calculate the

curve, the hopping conduction mechanism equation was transformed to the

I-V curves fitting the RRAM devices. For the hopping conduction,

where

d, Φ

T,

v0,

N and

a are films thickness, barrier height of hopping, intrinsic vibration frequency, the density of space charge, and mean hopping distance, respectively [

12,

18].

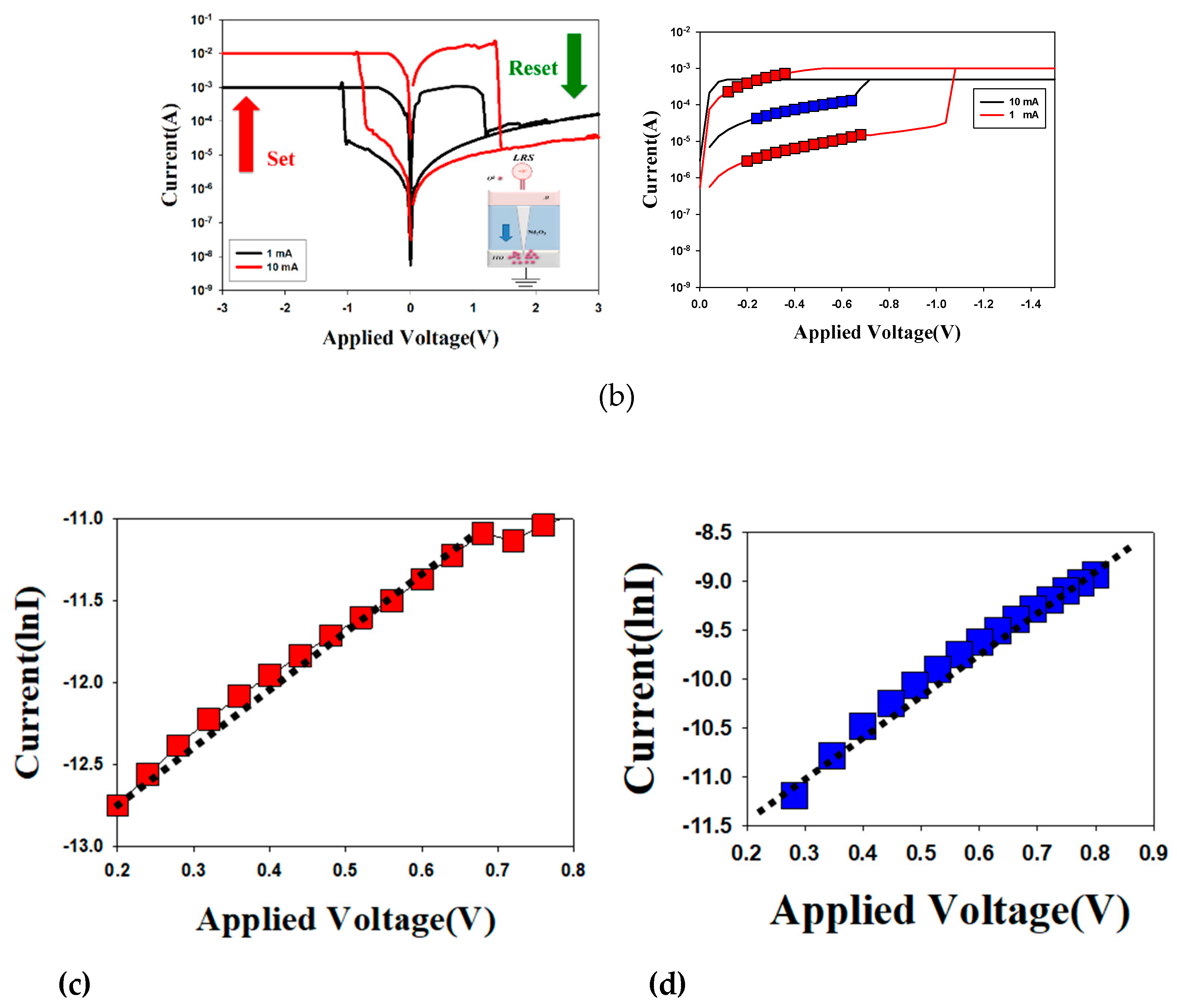

Figure 5 presented the

I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device using aluminum top electrode under different (a) compliance current processes and (b) conduction mechanisms. The applied compliance current for the neodymium oxide films RRAM device was 1mA and 10mA, respectively. The set and reset voltages of the RRAM device for a compliance current of 1mA were approximately 1V and -1V, respectively. For a compliance current of 10mA, the memory windows exhibited a high 10

4 ratio and a low set voltage. This result may be indicative of the low set voltage of high switch cycles induced by the high compliance current.

Figure 5(b) depicts the

I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device with an aluminum top electrode for different conduction mechanisms. The neodymium oxide films RRAM device for 1mA and 10mA compliance currents both exhibited the hopping conduction mechanism in low set voltage, as illustrated in

Figure 5(b). In addition, the electrical conduction mechanism of films RRAM devices of 10mA compliance current exhibited the hopping conduction behavior for all LRS/HRS in

Figure 5 (c) and (d). The electrical transfer mechanisms and initial metallic filament path model of the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices for aluminum electrode in the set/reset state also presented and described in

Figure 6.

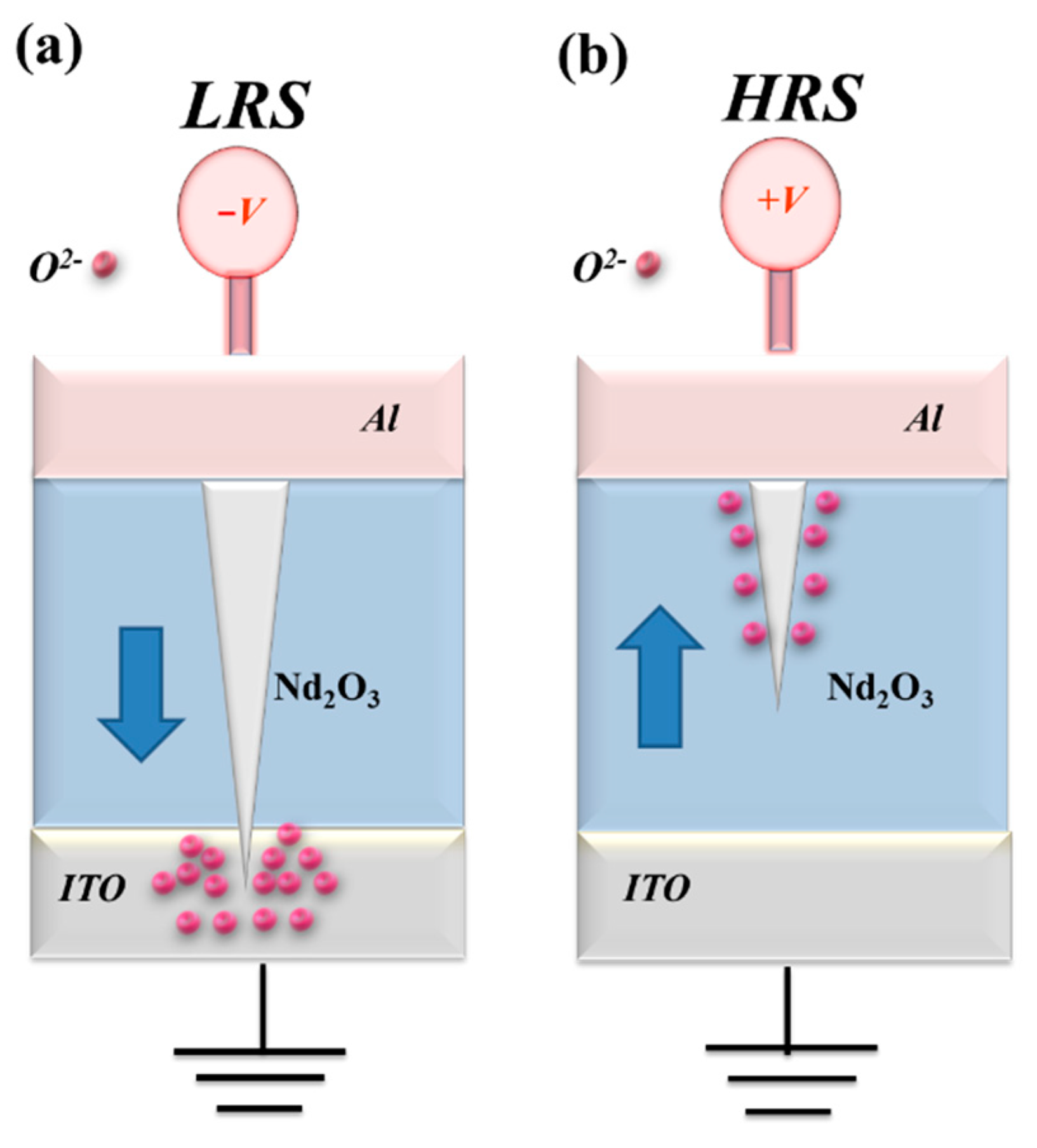

Figure 7 presented the

I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device with a TiN top electrode under different (a) compliance current processes and (b) conduction mechanisms. The set and reset voltages of the RRAM device with a TiN top electrode for 1mA compliance current were approximately 1V and -1V, respectively. At the 10 mA compliance current, the memory windows exhibited a high 10³ ratio and a low set voltage. The result may also be indicative of a low set voltage resulting from high switch cycles induced by a high compliance current.

Figure 7(b) depicts the

I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device with a TiN top electrode under different conduction mechanisms. The neodymium oxide films RRAM device with 1mA and 10mA compliance currents both exhibited a hopping conduction mechanism at low set voltages and an ohmic conduction mechanism at high applied voltages in

Figure 7 (c) and (d). The oxygen vacancies exist in the interface region between the TiN bottom/film of the RRAM device and gradually accumulate for LRS states. The physical conduction model provided the continuing oxidation reaction of the thin metal metallic filament path in high positive voltage later. Thin metal metallic filament were affected by oxygen atoms near the bottom electrode area. The electrical transfer mechanisms and initial metallic filament path model of the films RRAM devices for TiN electrode in the set/reset state clearly described in

Figure 8 [

23,

24].

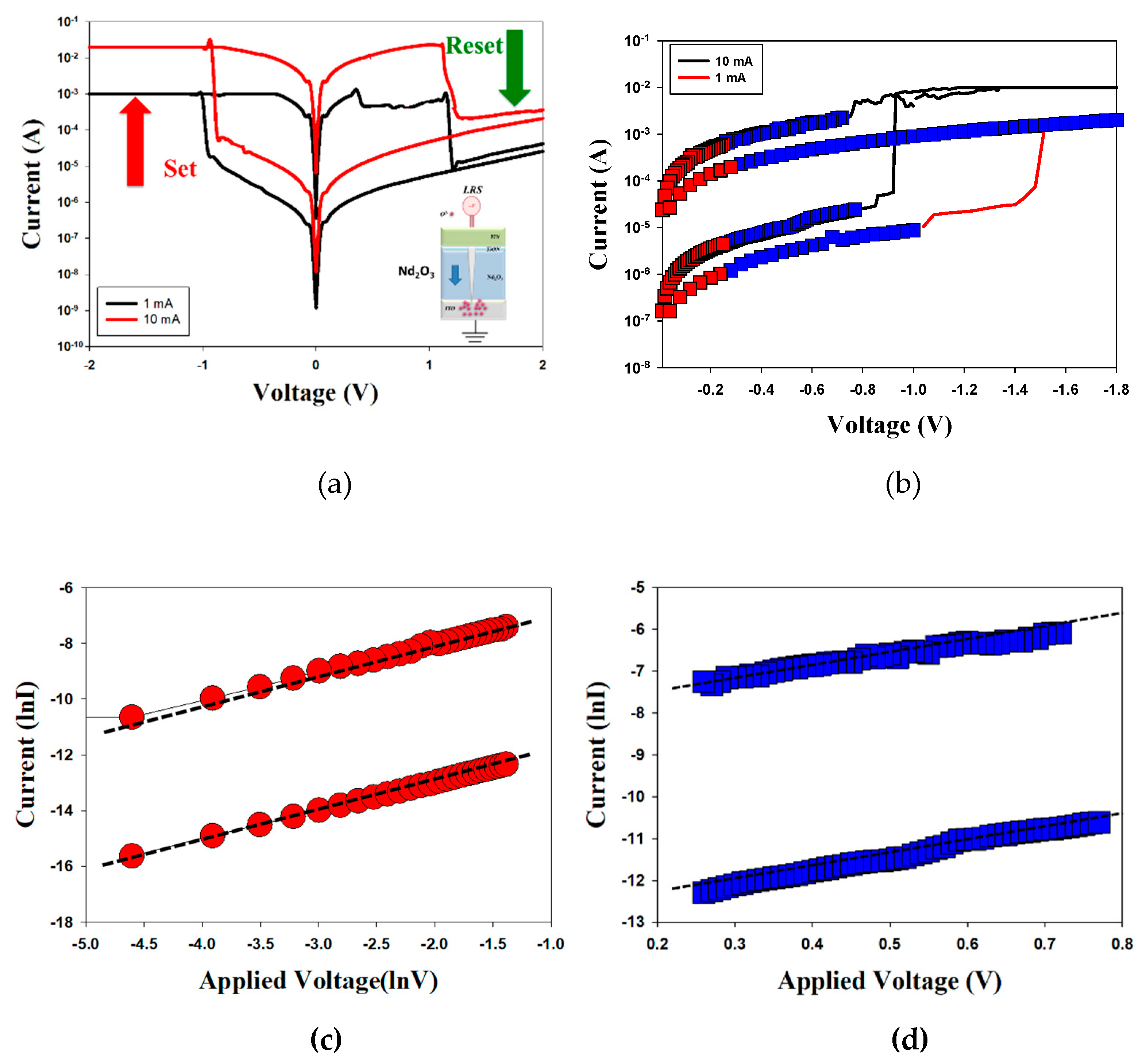

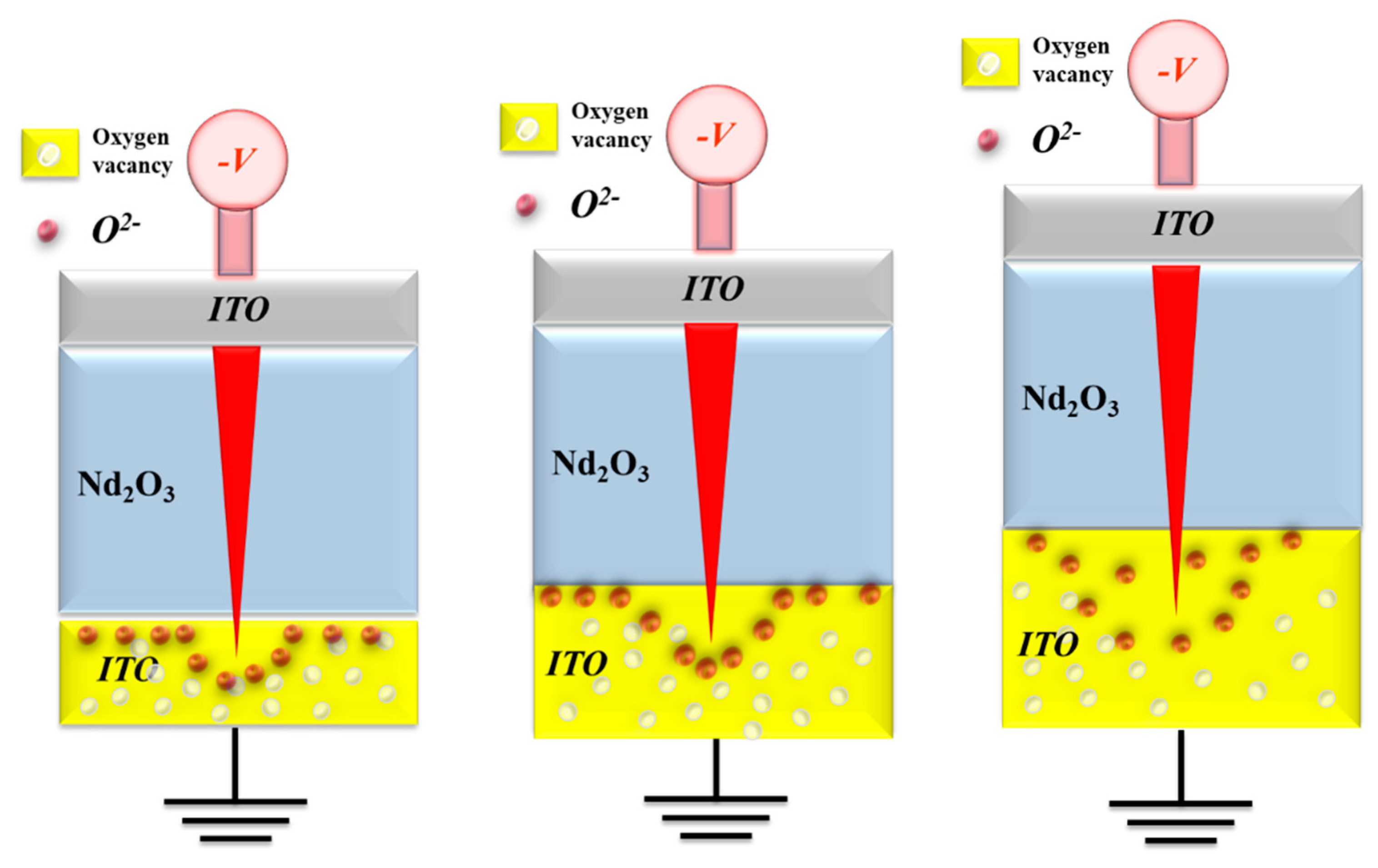

Figure 9 also presented the

I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device with an ITO top electrode under different (a) compliance current processes and (b) conduction mechanisms. The set and reset voltages of the RRAM device with an ITO top electrode and a 1mA compliance current were approximately 1V and -1.2V, respectively. At a compliance current of 1 mA, the memory windows demonstrated a high 10

3 ratio and a low set voltage. However, the memory windows exhibited a low 10

2 ratio with a 10mA compliance current. This result may also indicate the involvement of oxygen ions from the ITO electrode in the electron conduction path of the films.

Figure 9(b) depicts the

I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device with an ITO top electrode under different conduction mechanisms. The neodymium oxide films RRAM device exhibited the hopping conduction mechanism at low set voltages and the ohmic conduction mechanism at high applied voltages when tested with 1mA and 10mA compliance currents in

Figure 9 (c) and (d), respectively. The physical conduction model also provided the elliptical pattern of the depletion region formed by oxygen ions and vacancies gradually accumulates in the ITO top electrode of films RRAM device for LRS later. Additionally, the conductive metal continuously and sharply adsorbs oxygen atoms and vacancies in ITO electrode in HRS. In

Figure 10, the electrical transfer mechanisms and initial metallic filament path model of the films RRAM devices for ITO electrode were also clearly described [

23,

24].

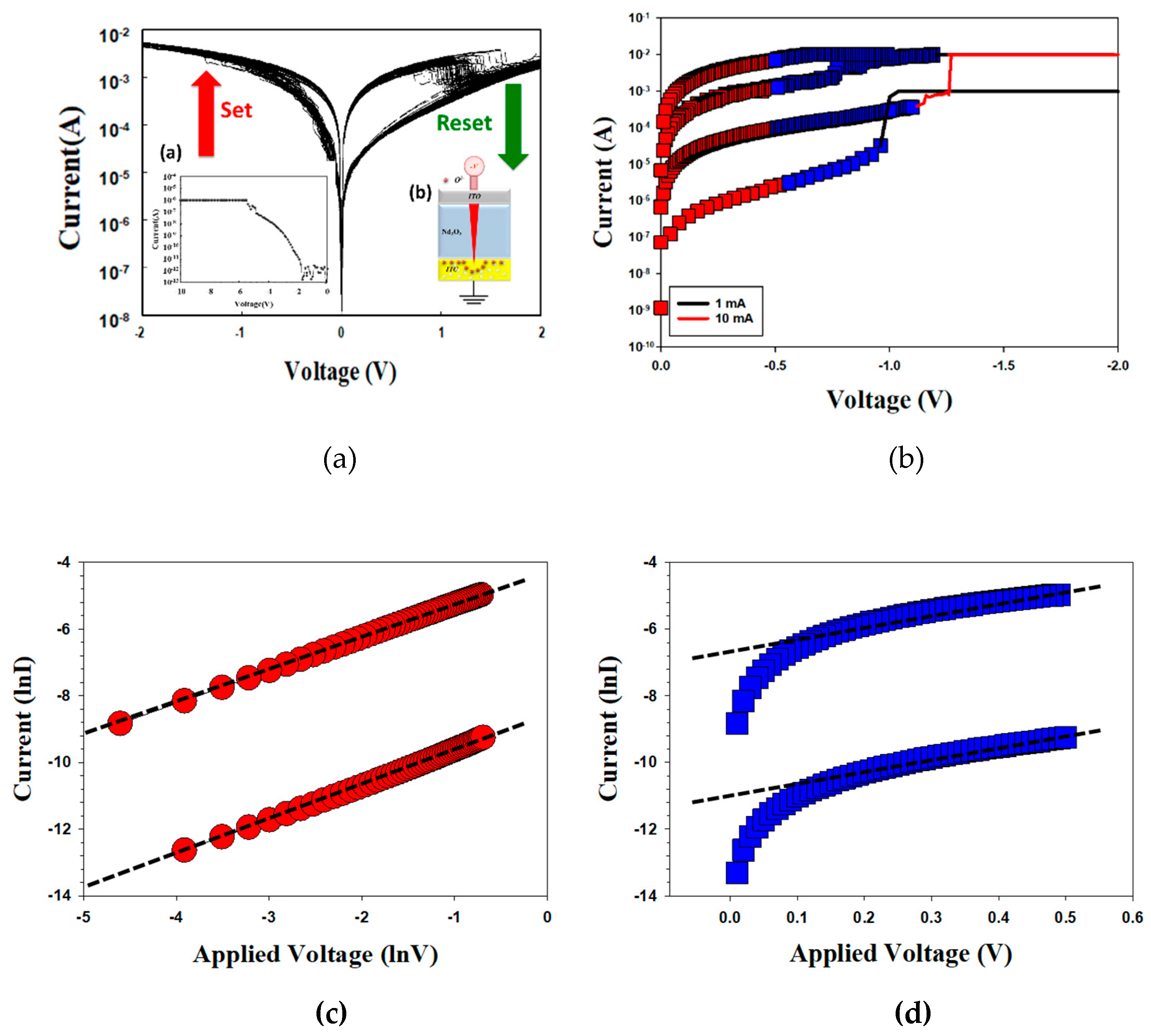

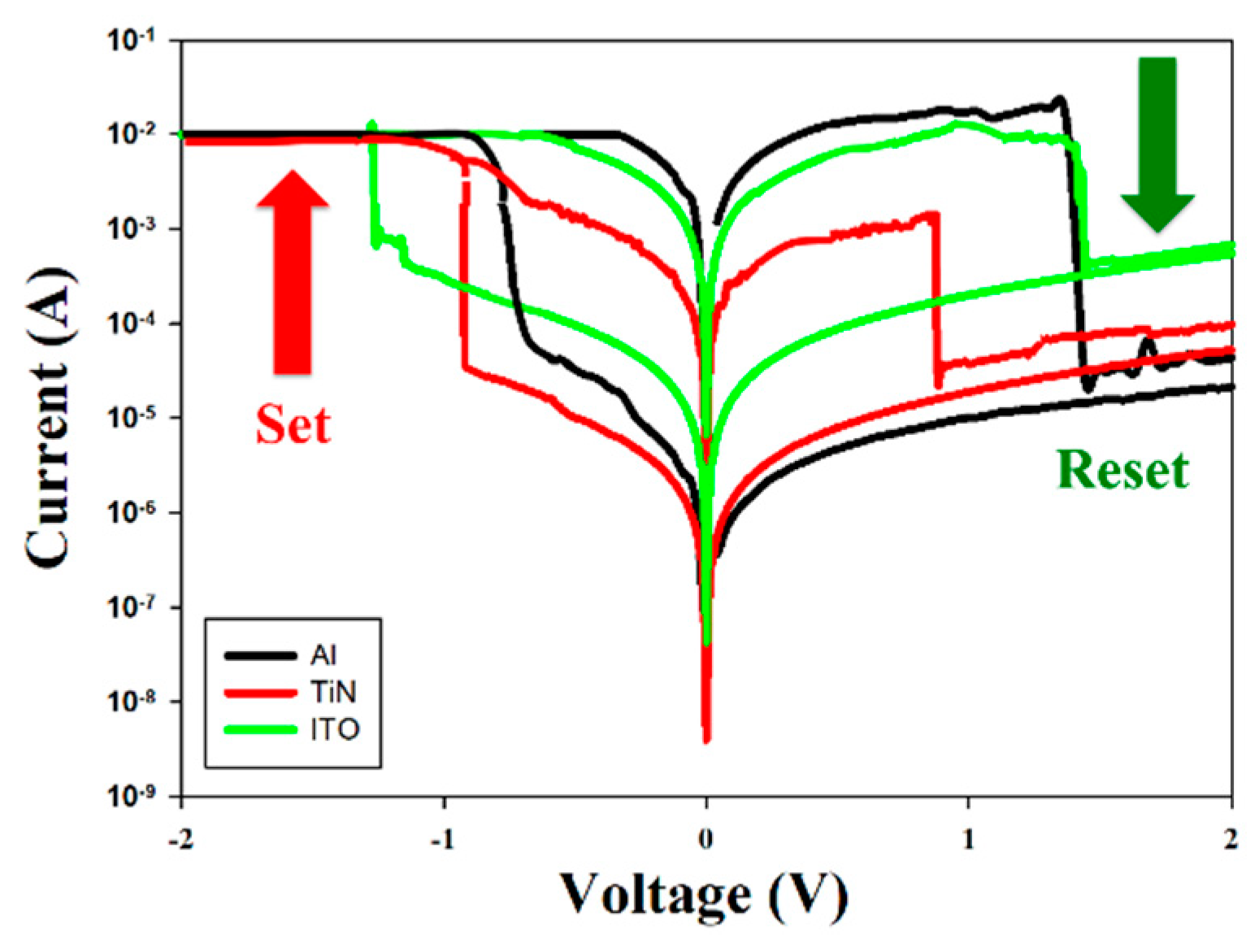

The above

I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device with different top electrode materials, including aluminum, TiN, and ITO, are presented in

Figure 11. At a compliance current of 10mA, the

I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device with an ITO electrode exhibited a symmetry memory window within the set/reset voltage range. The observed symmetry of the

I-V curves may be attributed to the barrier height at the interface between the films and the ITO electrode in the RRAM device, which employs the same top and bottom ITO electrode materials. In contrast, the top electrode of the RRAM device using aluminum or TiN exhibited asymmetric

I-V curves. The asymmetry of the

I-V curves in the set/reset voltage ranges may be attributed to the disparate barrier heights of the films and the ITO electrode interface. As illustrated in

Figure 11, the memory window ratios of the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices were approximately 10², 10³, and 10³, respectively.

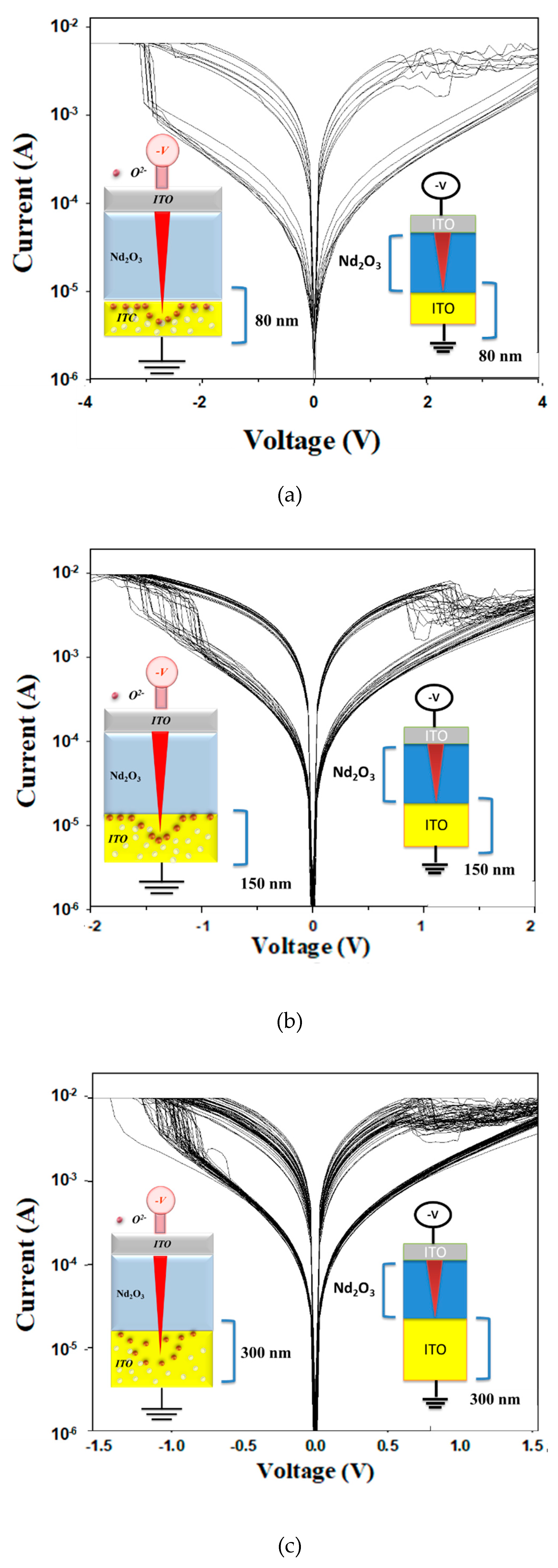

Figure 12 presented the 100 trace

I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device using ITO as the top electrode materials with thicknesses of (a) 80 nm, (b) 150 nm, and (c) 300 nm from 100 measurements. In the insert of

Figure 12(a)-(c), the left image depicts the electron transfer model, while the right image represents the MIM structure of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device.

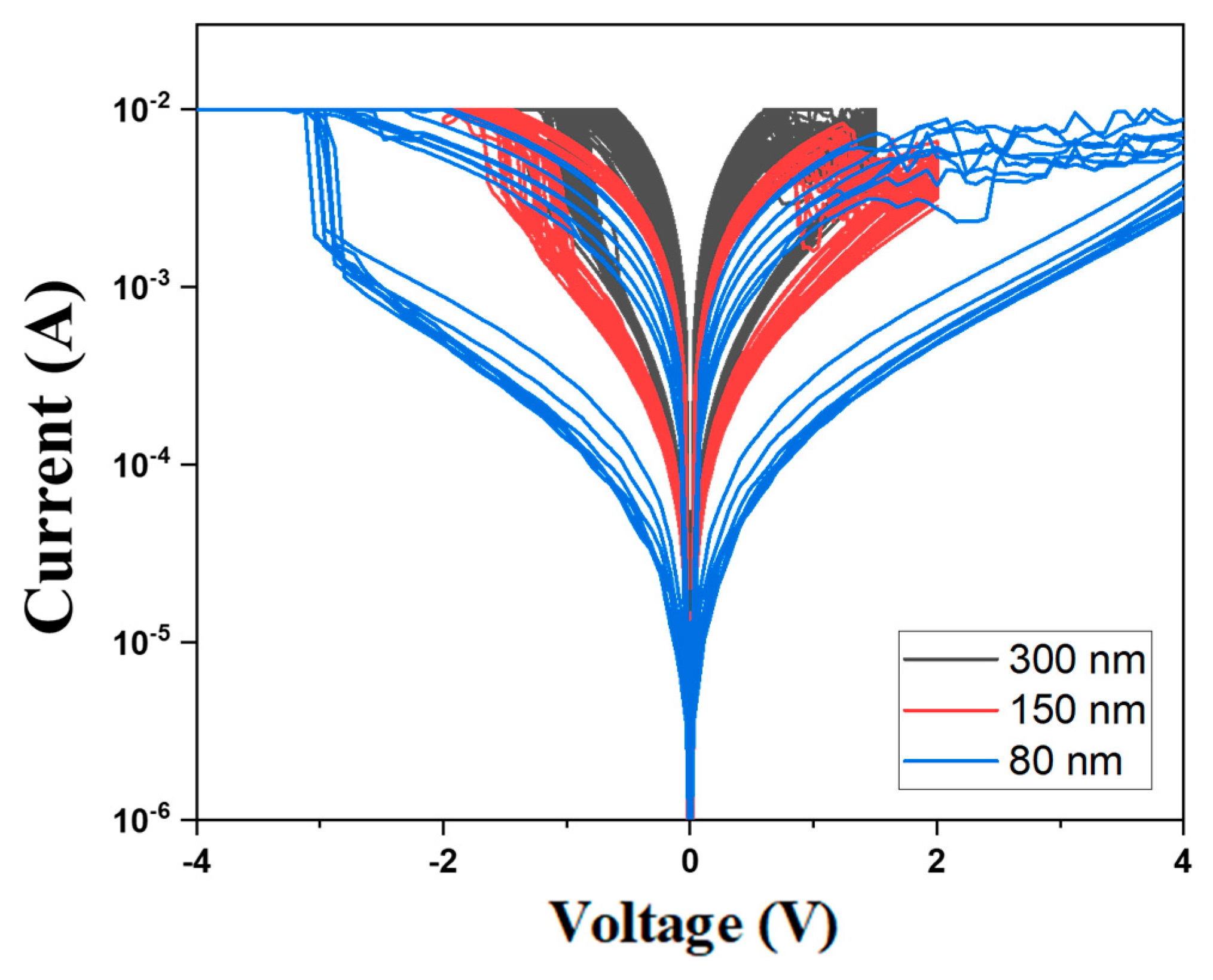

Figure 13 presents the

I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device using ITO as the top electrode materials with different thicknesses from 100 cycle times measurements. The neodymium oxide films RRAM device with a thickness of 300nm exhibited the maximum memory window in the order of 10

2 in both set and reset states. However, the neodymium oxide films RRAM device with a thickness between 80 and 150 nm exhibited a relatively narrow memory window, in the order of 10

2. As shown in

Figure 13, the set and reset voltage of RRAM devices decreased from ±3V to ±1.5V as the thickness increased from 80 nm to 300 nm.

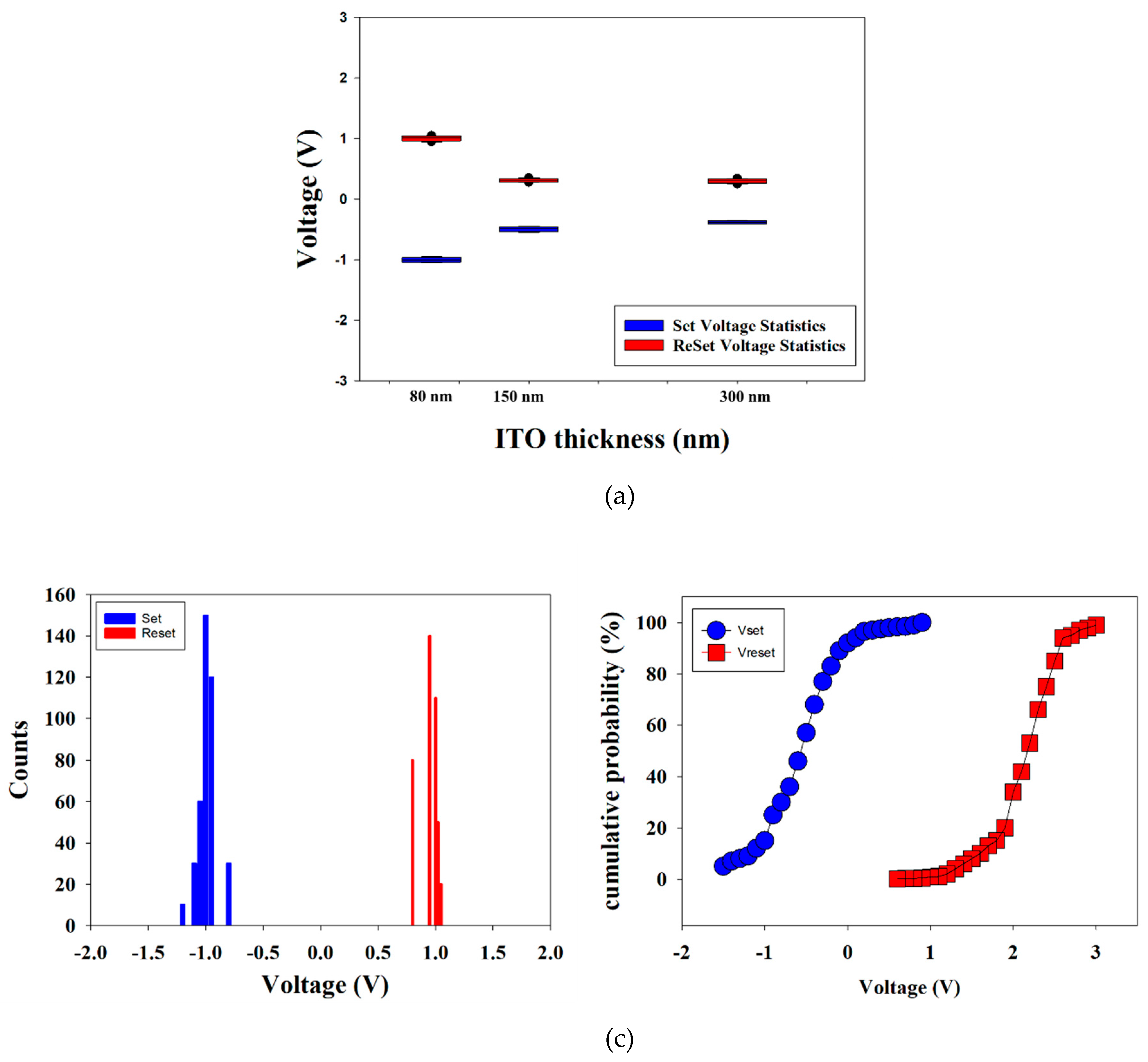

Figure 14 shows the set and reset voltages of neodymium oxide films RRAM devices using ITO as the top electrode materials with different thicknesses.

Figure 14b and

Figure 14c presents the statistical results of distribution of the set/reset voltage measured in RRAM devices for 400 times measured. In

Figure 11b, the set and reset voltage value was found for the range of applied voltage of −1 to 1 V in counts distribution results. In addition, the statistical results of cumulative probability for the resistive switching properties of the RRAM devices were also observed in

Figure 14c.

As illustrated in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14, the set voltage exerts a significant influence on the set process, while the oxygen concentration distribution effect also plays a pivotal role. In this study, three ITO electrodes with different thicknesses were used: 80 nm, 150 nm and 300 nm. The switching layer was a 15 nm thick neodymium oxide films under the same conditions, as shown in

Figure 15.

As shown by the set statistical results in

Figure 14, an increase in thickness correlates with a reduction in the set voltage. This suggests that oxygen ions are driven into the ITO films electrode, resulting in the creation of additional oxygen vacancies during the set process. As the thickness of the ITO continues to increase, the oxygen concentration distribution expands over a larger area of the ITO electrode. This may be a contributing factor to the low set voltage operation of the neodymium oxide films RRAM in the set process.

On the other hand, the reset statistical results indicates that the reset voltage increases as the thickness of the neodymium oxide films increases. The increasing reset voltage may be due to the diffuse of oxygen ions into the range of the ITO electrode in the set operation process as explained in

Figure 15. When the high reverse bias was applied in the reset process, the oxygen ions must be driven back to the neodymium oxide films switching layer. The physical model depicting the effect of oxygen concentration distribution effect in relation to different ITO electrode thicknesses is shown in

Figure 15.

To discuss the oxygen ion concentration distribution effect in oxygen-rich ITO electrode, the ser/reset voltage of neodymium oxide films RRAM devices for different ITO electrode thickness were discussed and investigated. The set operating voltage at the Al electrode was about 0.8V, and the minimum set voltage to form the conduction path of RRAM is about 1V, so the concentration distribution potential energy of oxygen in RRAM was about -0.2V. The set operating voltage of the ITO electrode was about 1.2V. Therefore, the oxygen ions fill the vacancies in ITO and attract oxygen ions to form a concentration distribution with a potential energy of 1.4V.

In addition, the set operating voltage at the TiN electrode was about 1V, and the minimum set voltage to form the conduction path of RRAM was about 1.1V, so the concentration distribution potential energy of oxygen in RRAM was about -0.1V. The set operating voltage of the ITO electrode was about 1.2V. Therefore, the oxygen ions fill the vacancies in ITO and attract oxygen ions to form a concentration distribution with a potential energy of 1.3V [

22]. Above the experimental results for infer the oxygen concentration distribution effect calculated, the set voltage of the RRAM devices in oxygen-rich ITO electrode was more less than those of other Al/TiN material electrode. Especially in different oxygen-rich ITO electrode thickness for 80nm, 150nm, and 300nm, the thick thickness ITO electrode exhibited the low set voltage. We suggested this reason might be attributed form the different oxygen concentration distribution effect close the interface for different oxygen-rich ITO electrode thickness, as shown in

Figure 15.

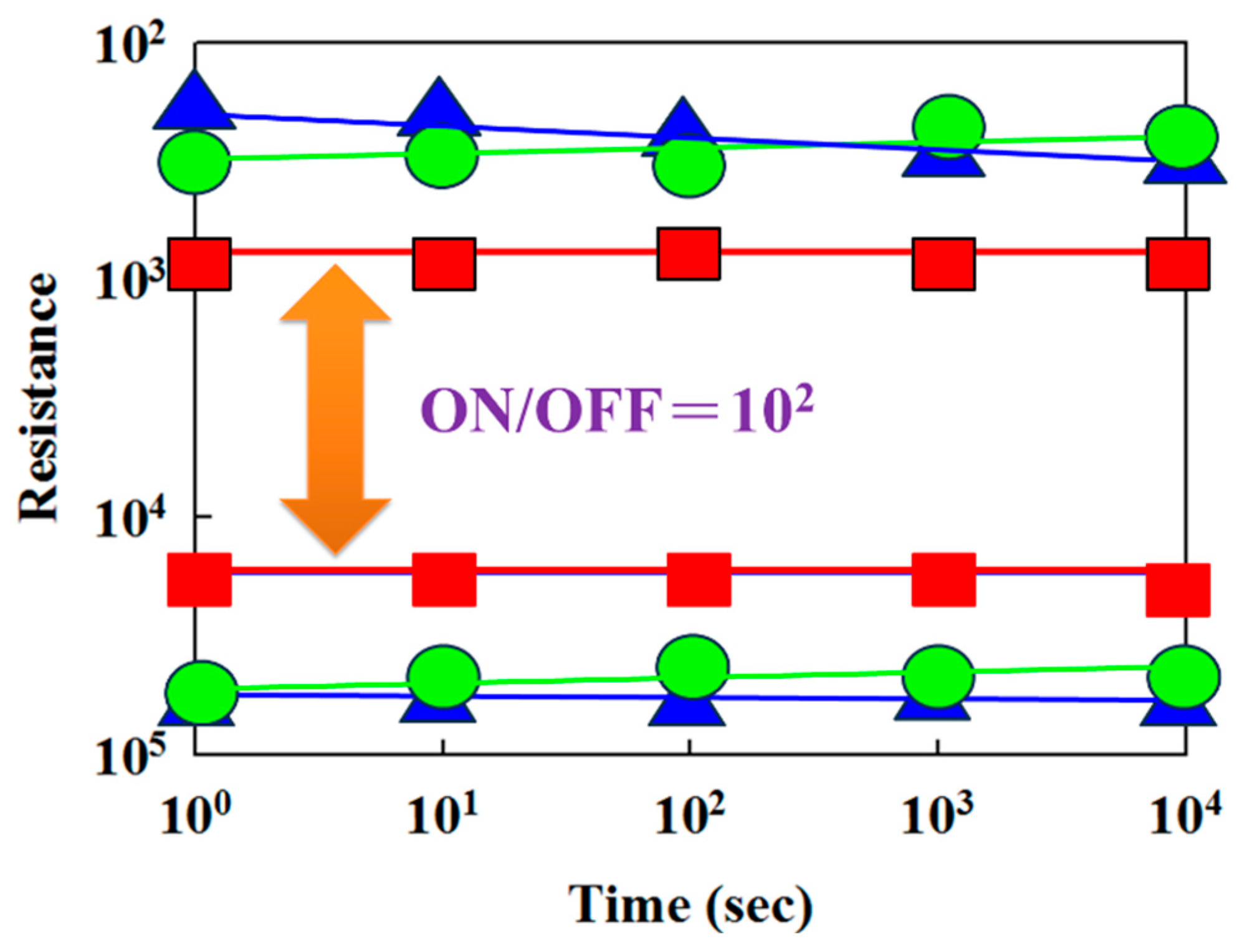

Figure 16 shows the switching cycling versus resistance value curves, determined by the retention and endurance measurement properties. The retention properties of the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices with different top electrode materials (Al, TiN, ITO) were measured to investigate their reliability for applications in non-volatile memory RRAM devices. There were no significant changes in the ON/OFF ratio switching resistance cycling versus testing time curves in the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices for more than 10

2 seconds in the extrapolation calculation anticipation measured.

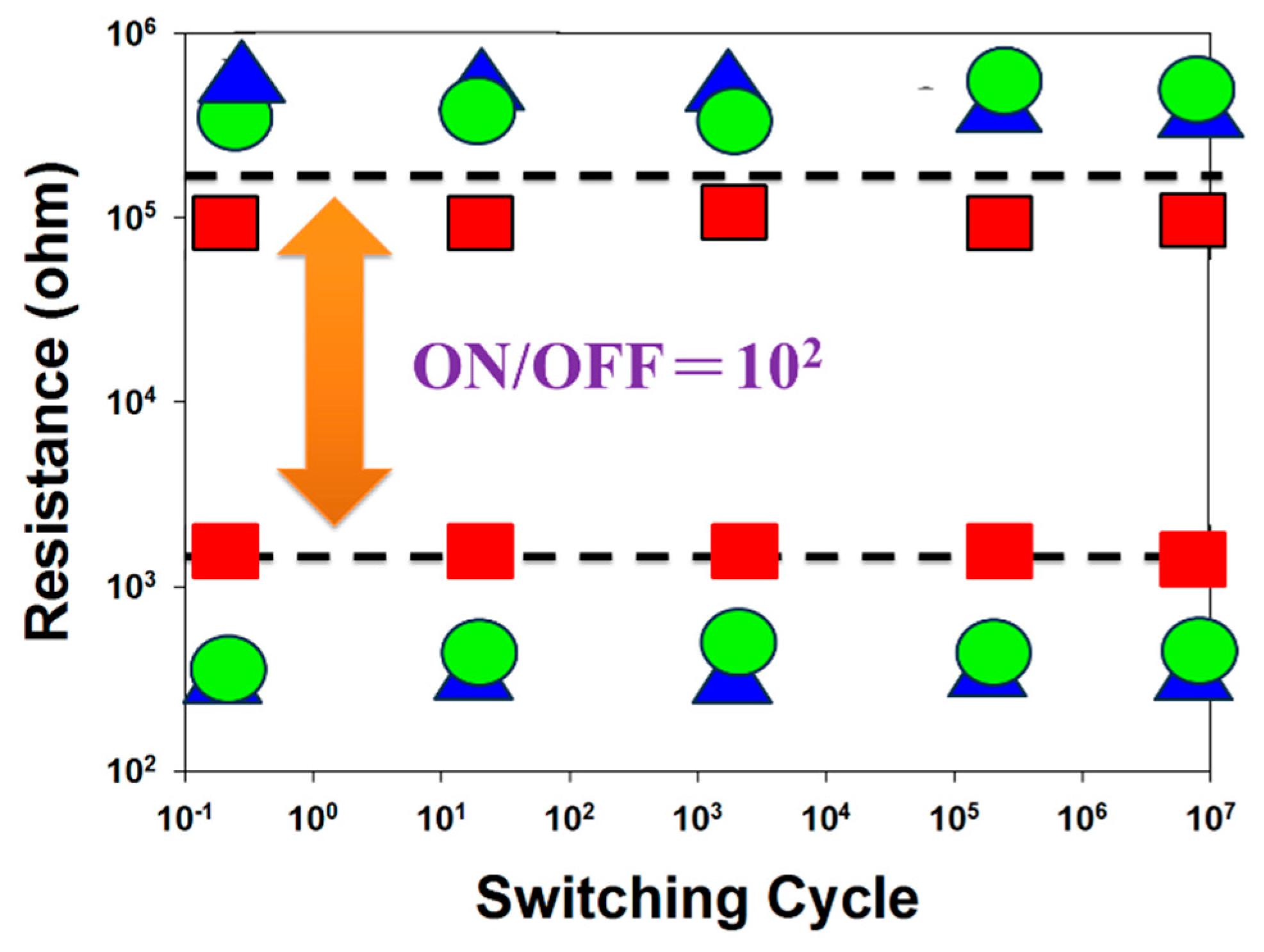

Figure 17 presents the resistance value versus switching cycle curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices with ITO (red), TiN (green), and aluminum (blue) as the top electrode materials. The neodymium oxide films RRAM device showed no significant changes in the ON/OFF ratio switching behavior cycling versus the time curves for more than 10

2 seconds in the extrapolation calculation anticipation.

Table 1 presented the compared on the film RRAM structure, the V

SET/V

RESET properties, the On/Off ratio properties, and the endurance cycles properties for the various films RRAM devices. In our work, the V

SET/V

RESET of the ITO/Nd

2O

3/ITO the film RRAM structure was about 1/-1V, the On/Off ratio of 10

2, and the endurance cycles of 10

7. Comparison those film RRAM devices, the ITO/Nd

2O

3/ITO the film RRAM structure also exhibited the excellent the resistance switching and endurance properties in our work.

Figure 1.

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the neodymium oxide films were examined at varying annealing temperatures, ranging from 400°C to 550°C.

Figure 1.

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the neodymium oxide films were examined at varying annealing temperatures, ranging from 400°C to 550°C.

Figure 2.

The micro-structure of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device with an Al/Nd/ITO structure.

Figure 2.

The micro-structure of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device with an Al/Nd/ITO structure.

Figure 3.

The cross-section structure of the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices with different top electrode materials for (a)Al (b) TiN, and (c) ITO material.

Figure 3.

The cross-section structure of the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices with different top electrode materials for (a)Al (b) TiN, and (c) ITO material.

Figure 4.

The I-V curves of the neodymium oxide thin-films RRAM devices with (a) the initial forming process and (b) the ITO/films/ITO structure from 100 measurements.

Figure 4.

The I-V curves of the neodymium oxide thin-films RRAM devices with (a) the initial forming process and (b) the ITO/films/ITO structure from 100 measurements.

Figure 5.

The I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device with aluminum top electrode under different (a)compliance current processes, and (b) conduction mechanisms (c) hopping conduction of LRS, and (d) hopping conduction of HRS.

Figure 5.

The I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device with aluminum top electrode under different (a)compliance current processes, and (b) conduction mechanisms (c) hopping conduction of LRS, and (d) hopping conduction of HRS.

Figure 6.

The electrical transfer mechanisms and initial metallic filament path model of the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices for aluminum electrode in the set/reset state.

Figure 6.

The electrical transfer mechanisms and initial metallic filament path model of the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices for aluminum electrode in the set/reset state.

Figure 7.

The I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device with a TiN electrode under different (a) compliance current processes and (b) conduction mechanisms (c) ohmic conduction for low electrical voltage, and (d) hopping conduction for high electrical voltage.

Figure 7.

The I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device with a TiN electrode under different (a) compliance current processes and (b) conduction mechanisms (c) ohmic conduction for low electrical voltage, and (d) hopping conduction for high electrical voltage.

Figure 8.

The electrical transfer mechanisms and initial metallic filament path model of the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices for TiN electrode in the set/reset state.

Figure 8.

The electrical transfer mechanisms and initial metallic filament path model of the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices for TiN electrode in the set/reset state.

Figure 9.

The I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device with an ITO electrode under different (a) compliance current processes and (b) conduction mechanisms (c) ohmic conduction, and (d) hopping conduction.

Figure 9.

The I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device with an ITO electrode under different (a) compliance current processes and (b) conduction mechanisms (c) ohmic conduction, and (d) hopping conduction.

Figure 10.

The electrical transfer mechanisms and initial metallic filament path model of the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices for ITO electrode in the set/reset state.

Figure 10.

The electrical transfer mechanisms and initial metallic filament path model of the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices for ITO electrode in the set/reset state.

Figure 11.

The I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device under different compliance current processes.

Figure 11.

The I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device under different compliance current processes.

Figure 12.

The I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device using ITO as the top electrode materials with thicknesses of (a) 80 nm, (b) 150 nm, and (c) 300 nm.

Figure 12.

The I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device using ITO as the top electrode materials with thicknesses of (a) 80 nm, (b) 150 nm, and (c) 300 nm.

Figure 13.

The I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device using ITO as the top electrode materials with different thicknesses.

Figure 13.

The I-V curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device using ITO as the top electrode materials with different thicknesses.

Figure 14.

The set/reset voltage statistics of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device using ITO as the top electrode materials with (a) different thicknesses, (b) counts distribution, and (c) cumulative probability.

Figure 14.

The set/reset voltage statistics of the neodymium oxide films RRAM device using ITO as the top electrode materials with (a) different thicknesses, (b) counts distribution, and (c) cumulative probability.

Figure 15.

The electrical transfer mechanisms and initial metallic filament path model of the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices in the reset state.

Figure 15.

The electrical transfer mechanisms and initial metallic filament path model of the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices in the reset state.

Figure 16.

The resistance value versus time curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices (red: ITO, green: TiN, blue: aluminum).

Figure 16.

The resistance value versus time curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices (red: ITO, green: TiN, blue: aluminum).

Figure 17.

The resistance value versus switching cycle curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices (red color: ITO, green color: TiN, blue color: aluminum).

Figure 17.

The resistance value versus switching cycle curves of the neodymium oxide films RRAM devices (red color: ITO, green color: TiN, blue color: aluminum).

Table 1.

The compared on the structure, the VSET/VRESET, the On/Off ratio, and the endurance cycles for the various films RRAM devices.

Table 1.

The compared on the structure, the VSET/VRESET, the On/Off ratio, and the endurance cycles for the various films RRAM devices.

| ROW |

STRUCTURE |

VSET/VRESET (V) |

On/Off RATIO |

ENDURANCE $(CYCLES) |

REF |

| 1 |

Al/MoOx/Pt |

3/-3 |

∼160 |

500 |

[26] |

| 2 |

Cu/Cu doped MoOx/Pt |

0.5/-1.5 |

∼23 |

106

|

[27] |

| 3 |

Ag/MoO3/ITO |

8/-8 |

∼1.28 |

25 |

[28] |

| 4 |

Ag/MoO3-x/FTO |

1.8/-1.1 |

∼8 |

10 |

[29] |

| 5 |

Ag/MoOx/ITO |

0.4/-0.067 |

>10 |

– |

[30] |

| 6 |

Ni/MoO3/Mo |

3.3/-2.3 |

<10 |

17 |

[31] |

| 7 |

Pt–Ir/MoOx/Pt |

3/-0.7 |

∼10 |

35 |

[32] |

| 8 |

Ag/MoOx/CQDs/Pt |

0.36/-0.25 |

∼70 |

107

|

[33] |

| 9 |

Al/SiO2/Si |

1/-2 |

∼10 |

10 |

[34] |

| 10 |

TiN/HfO2/TiN |

0.4/-0/4 |

<10 |

10 |

[35] |

| 11 |

ITO/Nd2O3/ITO |

1/-1 |

>102

|

107

|

This work |