Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

09 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Organic solar cells (OSCs) are one of the most promising candidates for the future commercialization of renewable energy sources that provide a low cost and flexible devices for different daily-life applications. This objective can be rapidly accomplished by formulating novel compounds and forecasting their efficiency and stability without significant investigation, thus minimizing the number of prospective targets. Data-driven machine learning (ML) algorithms can foretell materials energy levels, absorption response, stability, and efficiency of OSCs that helps in the development of novel high-performance materials. Nonetheless, the data-driven molecular design of organic solar cell materials continues to pose significant challenges. The primary issue lies in the complexity and variability of organic materials, which necessitates extensive and high-quality datasets for training robust machine learning models. Additionally, integrating these models into a coherent and efficient workflow that can be adopted by the scientific community remains an obstacle. This review article delves into the use of machine learning methods for organic solar cell research. Hence, the fundamentals of machine learning and the important procedures for applying these techniques in the context of organic solar cells are elaborated. A brief introduction to different classes of machine learning algorithms, as well as related software and tools, is provided. By addressing the challenges and leveraging the power of machine learning, we aim to pave the way for the accelerated discovery and optimization of organic solar cell materials, ultimately contributing to their commercialization and widespread adoption.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Use of Machine Learning in Organic Solar Cells

3. Steps of Machine Learning Applications

3.1. Sample Collection

3.2. Data Preparation and Processing

3.3. Model Building

3.4. Model Evaluation

4. Types of Machines Learning Algorithm

-

Supervised Learning: Supervised learning algorithms are trained on labeled data, meaning each training example is paired with an output label. These algorithms learn to map inputs to outputs, which is critical for predicting the properties of new materials.(Breiman 2001, Alvarez-Gonzaga and Rodriguez 2024)

- ○

-

Classification Algorithms: These are used to categorize data into predefined classes. For example, in organic solar cells, classification algorithms can predict whether a new material will act as a donor or acceptor based on its molecular structure.(Chen and Tang 2024)

- Support Vector Machines (SVM): SVMs are effective in classifying materials based on their electronic properties. For instance, they can help determine which molecular structures are likely to result in high-efficiency donor or acceptor materials for OSCs.

- Decision Trees and Random Forests: These algorithms identify critical structural features that determine material performance. They can be used to analyze various molecular descriptors and pinpoint which attributes are most influential in achieving high PCE.

- ○

-

Regression Algorithms: These predict continuous values, such as the power conversion efficiency (PCE) of organic solar cells.

- Linear Regression: Often used to model the relationship between molecular descriptors and PCE. For example, linear regression can help establish how changes in molecular structure affect the efficiency of OSCs.(Rosenblatt 1958)

- Neural Networks: Neural networks can capture more complex, non-linear relationships between structure and efficiency. They are particularly useful in modeling the intricate dependencies between various molecular features and the overall performance of OSCs.(Goodfellow 2016)

-

Unsupervised Learning: Unsupervised learning algorithms deal with data without labeled responses. They are useful for discovering hidden patterns or intrinsic structures in the data. (Ain 2010)

- ○

- Clustering Algorithms: Clustering algorithms, such as k-Means, can group materials with similar properties, aiding in the identification of promising material families. For instance, clustering can reveal which sets of molecular structures consistently yield high-efficiency OSCs. (Sahu, Yang et al. 2019)

- ○

- Dimensionality Reduction Techniques: Techniques like PCA (Principal Component Analysis) reduce the complexity of data while retaining essential patterns, which is crucial when dealing with high-dimensional datasets in materials science. PCA can help identify the most influential factors in determining OSC performance, streamlining the design process.(Padula, Simpson et al. 2019)

-

Reinforcement Learning: Reinforcement learning involves training models through trial and error, using feedback from their actions. This approach can optimize material synthesis processes or experimental procedures to maximize efficiency or yield.

- ○

- Q-Learning and Deep Q-Networks (DQN): These techniques can optimize the sequence of synthesis steps to produce materials with desired properties efficiently. For example, reinforcement learning can help refine the fabrication process of OSCs to enhance their stability and efficiency.(Padula, Simpson et al. 2019)

-

Hybrid and Multiscale Modeling: These approaches integrate different modeling techniques to provide a comprehensive understanding of material behavior across various scales.(Padula, Simpson et al. 2019)

- ○

- Atomistic or Molecular-Level Models: These models focus on the interactions at the molecular level, which are crucial for understanding the fundamental properties of materials. For instance, molecular dynamics simulations can reveal how molecular vibrations and rotations affect the electronic properties of OSCs.(Frenkel and Smit 2023)

- ○

- Continuum or Device-Level Models: These models help in understanding how molecular-level properties translate to macroscopic device performance. For example, continuum models can simulate the charge transport properties in OSCs, providing insights into how molecular arrangements affect overall efficiency.

-

Performance Prediction and Optimization: Performance prediction and optimization involve using computational models, statistical methods, or machine learning techniques to forecast and improve the performance of a system, device, or process.

- ○

- Performance Prediction: In the context of organic solar cells, performance prediction involves using models or algorithms to estimate and forecast the characteristics and efficiency of the solar cell based on various factors. This prediction may encompass the expected power conversion efficiency (PCE), short-circuit current density (Jsc), open-circuit voltage (Voc), fill factor (FF), or other key metrics that quantify the effectiveness of the solar cell in converting sunlight into electricity. For example, machine learning models can predict how different material compositions and device architectures will perform under specific operating conditions. (Afzal and Hachmann 2020)

- ○

- Optimization Strategies: Optimization involves adjusting parameters such as material composition, device architecture, layer thicknesses, interfaces, or manufacturing processes to maximize efficiency, increase stability, or enhance other desirable characteristics. Machine learning algorithms can be used to identify the optimal combinations of these parameters, significantly reducing the need for extensive trial-and-error experimentation. For instance, genetic algorithms can be employed to explore a vast parameter space and find the best configuration for high-efficiency OSCs.(Padula, Simpson et al. 2019)

-

Materials Discovery and Design: Materials discovery and design involve the systematic search, identification, and development of new materials or the optimization of existing materials with desired properties for specific applications.

- ○

- Property Prediction and Screening: Machine learning models can predict the properties of potential materials, allowing researchers to screen large databases and identify promising candidates quickly. For example, predictive models can estimate the electronic properties of new organic molecules, aiding in the discovery of high-performance materials for OSCs.(Butler, Davies et al. 2018, Sahu, Yang et al. 2019)

- ○

- Database Mining and High-Throughput Screening: ML algorithms can mine existing databases of materials to identify patterns and correlations that may not be apparent through traditional analysis. High-throughput screening techniques can rapidly evaluate a vast number of materials, accelerating the discovery process.(Jain, Ong et al. 2013)

- ○

- Structure-Property Relationships: Understanding the relationships between molecular structure and material properties is crucial for designing new materials. Machine learning can help elucidate these relationships, guiding the rational design of materials with desired characteristics.

- ○

- Design and Synthesis: Once promising materials are identified, machine learning can aid in optimizing the synthesis processes to ensure reproducibility and scalability. For example, ML models can suggest optimal reaction conditions to synthesize high-purity materials efficiently.

-

Process and Manufacturing Optimization: Process and manufacturing optimization in the context of organic solar cells involves improving and refining the procedures, techniques, and production methods used in fabricating these photovoltaic devices.(Alvarez-Gonzaga and Rodriguez 2024)

- ○

- Process Control and Standardization: Machine learning can be used to develop standardized protocols that ensure consistent quality and performance of OSCs. For example, ML algorithms can monitor production processes in real-time, adjusting parameters to maintain optimal conditions.

- ○

- Yield Improvement: By analyzing production data, machine learning can identify factors that influence yield and suggest modifications to improve it. This can lead to higher efficiency and lower costs in OSC manufacturing.

- ○

- Scaling Production and Cost Reduction: ML techniques can optimize manufacturing processes to make them more scalable and cost-effective. For instance, predictive models can help in planning resource allocation and minimizing waste.

- ○

- Robustness and Reliability: Machine learning can enhance the robustness and reliability of OSCs by identifying and mitigating factors that lead to device degradation. This can result in longer-lasting and more stable solar cells.

-

Pattern Recognition and Data Analysis: Pattern recognition and data analysis involve the systematic process of identifying meaningful patterns, structures, or relationships within datasets, enabling the extraction of valuable insights or information.(Sahu, Yang et al. 2019)

- ○

- Data Collection and Preprocessing: Efficient data collection and preprocessing are crucial for ensuring high-quality inputs for ML models. This includes cleaning data, handling missing values, and normalizing data to make it suitable for analysis.

- ○

- Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA): EDA techniques help in understanding the underlying patterns and distributions in the data. Visualization tools can provide insights into how different variables interact and influence OSC performance.

- ○

- Feature Extraction and Selection: Identifying the most relevant features or descriptors is essential for building accurate ML models. Techniques like PCA can reduce the dimensionality of the data, focusing on the most significant variables.

- ○

- Clustering and Classification: Clustering algorithms can group similar data points, helping to identify patterns in material properties. Classification algorithms can categorize materials based on their predicted performance.

- ○

- Regression and Prediction: Regression techniques can model the relationships between variables, providing predictions for new data points. These predictions can guide the development of new materials and the optimization of OSCs.

- ○

- Anomaly Detection and Outlier Analysis: Identifying anomalies and outliers in the data can reveal potential issues or novel phenomena that warrant further investigation. This can lead to new discoveries and improvements in OSC technology.

- ○

- Correlation and Relationship Analysis: Understanding the correlations and relationships between different variables helps in identifying key factors that influence OSC performance. This knowledge can inform the design and optimization of new materials.(Jain, Ong et al. 2013)

5. Machine Learning Analysis of Organic Solar Cells

5.1. Molecular Descriptors

5.2. Molecular Fingerprints

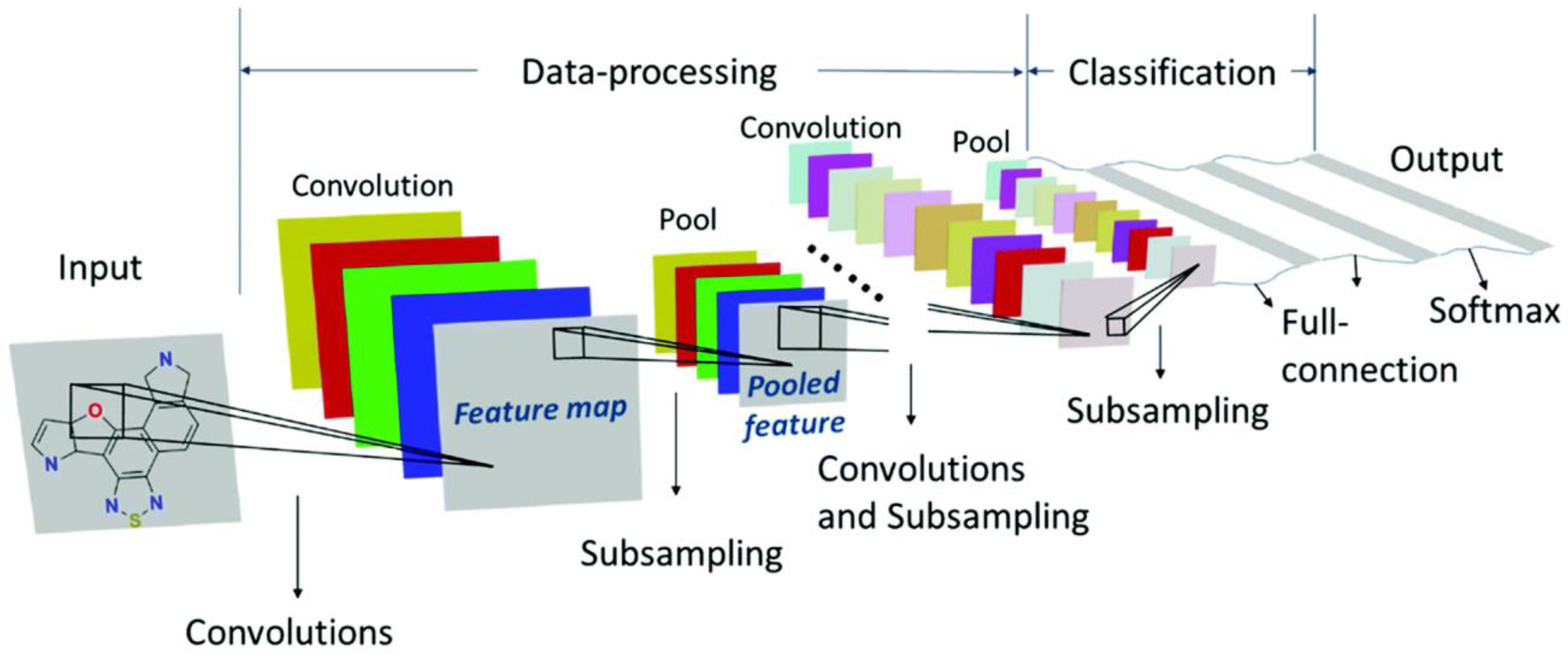

5.3. Images

5.4. Microscopic Properties

5.5. Energy Levels

5.6. Simulated Properties

6. Problems and Future Prospects

6.1. Data Infrastructure

6.2. Descriptor Selection

6.3. Multidimensional Design

6.4. Experimental Validation

6.5. Development of Better Software

References

- Lopez, S. A. , et al. (2017). "Design principles and top non-fullerene acceptor candidates for organic photovoltaics." Joule 1(4): 857-870. [CrossRef]

- Ding, P. , et al. (2024). "Stability of organic solar cells: toward commercial applications." Chemical Society Reviews 53(5): 2350-2387. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. , et al. (2023). "The critical role of the donor polymer in the stability of high-performance non-fullerene acceptor organic solar cells." Joule 7(4): 810-829. [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M. A. F. and J. Hachmann (2020). High-throughput computational studies in catalysis and materials research, and their impact on rational design. HANDBOOK ON BIG DATA AND MACHINE LEARNING IN THE PHYSICAL SCIENCES: Volume 1. Big Data Methods in Experimental Materials Discovery, World Scientific: 1-44. [CrossRef]

- Ain, A. (2010). "Data clustering: 50 years beyond K-means [J]." Pattern Recognition Letters 31(8): 651-666. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Gonzaga, O. A. and J. I. Rodriguez (2024). "Machine learning models with different cheminformatics data sets to forecast the power conversion efficiency of organic solar cells." arXiv preprint. arXiv:2410.23444.

- Breiman, L. (2001). "Random forests." Machine learning 45: 5-32. [CrossRef]

- Butler, K. T. , et al. (2018). "Machine learning for molecular and materials science." Nature 559(7715): 547-555. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G. and D.-M. Tang (2024). "Machine Learning as a “Catalyst” for Advancements in Carbon Nanotube Research." Nanomaterials 14(21): 1688. [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, D. and B. Smit (2023). Understanding molecular simulation: from algorithms to applications, Elsevier.

- Goodfellow, I. (2016). Deep learning, MIT press. [CrossRef]

- Jain, A. , et al. (2013). "Commentary: The Materials Project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation." APL materials 1(1). [CrossRef]

- Padula, D. , et al. (2019). "Combining electronic and structural features in machine learning models to predict organic solar cells properties." Materials Horizons 6(2): 343-349. [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, F. (1958). "The perceptron: a probabilistic model for information storage and organization in the brain." Psychological review 65(6): 386. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, H. , et al. (2019). "Designing promising molecules for organic solar cells via machine learning assisted virtual screening." Journal of Materials Chemistry A 7(29): 17480-17488. [CrossRef]

- Cereto-Massagué, A. , et al. (2015). "Molecular fingerprint similarity search in virtual screening." Methods 71: 58-63. [CrossRef]

- Cova, T. and A. Pais (2019). Deep learning for deep chemistry: optimizing the prediction of chemical patterns. Front Chem 7: 809. [CrossRef]

- Du, P. , et al. (2018). "Microstructure design using graphs." npj Computational Materials 4(1): 50. [CrossRef]

- Du, X. , et al. (2019). "Efficient polymer solar cells based on non-fullerene acceptors with potential device lifetime approaching 10 years." Joule 3(1): 215-226. [CrossRef]

- Duong, D. T. , et al. (2012). "Molecular solubility and hansen solubility parameters for the analysis of phase separation in bulk heterojunctions." Journal of Polymer Science Part B: Polymer Physics 50(20): 1405-1413. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J. , et al. (2020). "Over 14.5% efficiency and 71.6% fill factor of ternary organic solar cells with 300 nm thick active layers." Energy & environmental science 13(3): 958-967. [CrossRef]

- Gu, G. H. , et al. (2019). "Machine learning for renewable energy materials." Journal of Materials Chemistry A 7(29): 17096-17117. [CrossRef]

- Hachmann, J. , et al. (2014). "Lead candidates for high-performance organic photovoltaics from high-throughput quantum chemistry–the Harvard Clean Energy Project." Energy & environmental science 7(2): 698-704. [CrossRef]

- Imamura, Y. , et al. (2017). "Automatic high-throughput screening scheme for organic photovoltaics: estimating the orbital energies of polymers from oligomers and evaluating the photovoltaic characteristics." The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 121(51): 28275-28286. [CrossRef]

- Jones, L. and P. D. Nellist (2013). "Identifying and correcting scan noise and drift in the scanning transmission electron microscope." Microscopy and Microanalysis 19(4): 1050-1060. [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, P. B. , et al. (2018). "Machine learning-based screening of complex molecules for polymer solar cells." The Journal of chemical physics 148(24). [CrossRef]

- Kodali, H. K. and B. Ganapathysubramanian (2012). "Computer simulation of heterogeneous polymer photovoltaic devices." Modelling and Simulation in Materials Science and Engineering 20(3): 035015. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-H. (2020). "A Machine Learning–Based Design Rule for Improved Open-Circuit Voltage in Ternary Organic Solar Cells." Advanced Intelligent Systems 2(1): 1900108. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-H. (2020). "Performance and matching band structure analysis of tandem organic solar cells using machine learning approaches." Energy Technology 8(3): 1900974. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-H. (2020). "Robust random forest based non-fullerene organic solar cells efficiency prediction." Organic Electronics 76: 105465. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. H. (2019). "Insights from machine learning techniques for predicting the efficiency of fullerene derivatives-based ternary organic solar cells at ternary blend design." Advanced Energy Materials 9(26): 1900891. [CrossRef]

- Linderl, T. , et al. (2017). "Energy Losses in Small-Molecule Organic Photovoltaics." Advanced Energy Materials 7(16): 1700237. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. , et al. (2019). "15% efficiency tandem organic solar cell based on a novel highly efficient wide-bandgap nonfullerene acceptor with low energy loss." Advanced Energy Materials 9(11): 1803657. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.-K. , et al. (2019). "Achieving high-performance non-halogenated nonfullerene acceptor-based organic solar cells with 13.7% efficiency via a synergistic strategy of an indacenodithieno [3, 2-b] selenophene core unit and non-halogenated thiophene-based terminal group." Journal of Materials Chemistry A 7(42): 24389-24399. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T. , et al. (2020). "Concurrent improvement in J sc and V oc in high-efficiency ternary organic solar cells enabled by a red-absorbing small-molecule acceptor with a high LUMO level." Energy & environmental science 13(7): 2115-2123. arXiv:10.1039/D0EE00662A.

- Lopez, S. A. , et al. (2017). "Design principles and top non-fullerene acceptor candidates for organic photovoltaics." Joule 1(4): 857-870. [CrossRef]

- Majeed, N. , et al. (2020). "Using deep machine learning to understand the physical performance bottlenecks in novel thin-film solar cells." Advanced Functional Materials 30(7): 1907259. arXiv:10.1002/adfm.201907259.

- Mahmood, A. , et al. (2018). "Recent progress in porphyrin-based materials for organic solar cells." Journal of Materials Chemistry A 6(35): 16769-16797. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A. , et al. (2019). "First-principles theoretical designing of planar non-fullerene small molecular acceptors for organic solar cells: manipulation of noncovalent interactions." Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 21(4): 2128-2139. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A. and J.-L. Wang (2021). "Machine learning for high performance organic solar cells: current scenario and future prospects." Energy & environmental science 14(1): 90-105. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A. and J. L. Wang (2020). "A review of grazing incidence small-and wide-angle x-ray scattering techniques for exploring the film morphology of organic solar cells." Solar RRL 4(10): 2000337. [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, S. , et al. (2018). "Computer-aided screening of conjugated polymers for organic solar cell: classification by random forest." The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 9(10): 2639-2646. [CrossRef]

- Noruzi, R. , et al. (2020). "NURBS-based microstructure design for organic photovoltaics." Computer-Aided Design 118: 102771. [CrossRef]

- Olivares-Amaya, R. , et al. (2011). "Accelerated computational discovery of high-performance materials for organic photovoltaics by means of cheminformatics." Energy & environmental science 4(12): 4849-4861. [CrossRef]

- Padula, D. , et al. (2019). "Combining electronic and structural features in machine learning models to predict organic solar cells properties." Materials Horizons 6(2): 343-349. [CrossRef]

- Padula, D. and A. Troisi (2019). "Concurrent optimization of organic donor–acceptor pairs through machine learning." Advanced Energy Materials 9(40): 1902463. [CrossRef]

- Pattanaik, L. and C. W. Coley (2020). "Molecular representation: going long on fingerprints." Chem 6(6): 1204-1207. [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.-P. and Y. Zhao (2019). "Convolutional neural networks for the design and analysis of non-fullerene acceptors." Journal of chemical information and modeling 59(12): 4993-5001. [CrossRef]

- Perea, J. D. , et al. (2017). "Introducing a new potential figure of merit for evaluating microstructure stability in photovoltaic polymer-fullerene blends." The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 121(33): 18153-18161. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F. , et al. (2017). "Machine learning methods to predict density functional theory B3LYP energies of HOMO and LUMO orbitals." Journal of chemical information and modeling 57(1): 11-21. [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, S. , et al. (2018). "Process optimization for microstructure-dependent properties in thin film organic electronics." Materials Discovery 11: 6-13. [CrossRef]

- Pokuri, B. S. S. , et al. (2019). "Interpretable deep learning for guided microstructure-property explorations in photovoltaics." npj Computational Materials 5(1): 95. [CrossRef]

- Pokuri, B. S. S. , et al. (2019). "GRATE: A framework and software for GRaph based Analysis of Transmission Electron Microscopy images of polymer films." Computational Materials Science 163: 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Pyzer-Knapp, E. O. , et al. (2022). "Accelerating materials discovery using artificial intelligence, high performance computing and robotics." npj Computational Materials 8(1): 84. [CrossRef]

- Pyzer-Knapp, E. O. , et al. (2016). "A Bayesian approach to calibrating high-throughput virtual screening results and application to organic photovoltaic materials." Materials Horizons 3(3): 226-233. [CrossRef]

- Pyzer-Knapp, E. O. , et al. (2015). "Learning from the harvard clean energy project: The use of neural networks to accelerate materials discovery." Advanced Functional Materials 25(41): 6495-6502. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, H. , et al. (2018). "Toward predicting efficiency of organic solar cells via machine learning and improved descriptors." Advanced Energy Materials 8(24): 1801032. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Lengeling, B. and A. Aspuru-Guzik (2018). "Inverse molecular design using machine learning: Generative models for matter engineering." Science 361(6400): 360-365. [CrossRef]

- Scharber, M. C. , et al. (2006). "Design rules for donors in bulk-heterojunction solar cells—Towards 10% energy-conversion efficiency." Advanced materials 18(6): 789-794. [CrossRef]

- Schleder, G. R. , et al. (2019). "From DFT to machine learning: recent approaches to materials science–a review." Journal of Physics: Materials 2(3): 032001. [CrossRef]

- Sui, M.-Y. , et al. (2019). "Nonfullerene acceptors for organic photovoltaics: from conformation effect to power conversion efficiencies prediction." Solar RRL 3(11): 1900258. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W. , et al. (2019). "The use of deep learning to fast evaluate organic photovoltaic materials." Advanced Theory and Simulations 2(1): 1800116. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W. , et al. (2019). Machine learning-assisted molecular design and efficiency prediction for high-performance organic photo-voltaic materials. Sci Adv 5 (11): eaay4275. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W. , et al. (2019). "Machine learning–assisted molecular design and efficiency prediction for high-performance organic photovoltaic materials." Science advances 5(11): eaay4275. [CrossRef]

- Taffese, W. Z. and L. Espinosa-Leal (2024). "Unveiling non-steady chloride migration insights through explainable machine learning." Journal of Building Engineering 82: 108370. [CrossRef]

- Vo, A. H. , et al. (2019). "An overview of machine learning and big data for drug toxicity evaluation." Chemical research in toxicology 33(1): 20-37. [CrossRef]

- Wadsworth, A. , et al. (2019). "Critical review of the molecular design progress in non-fullerene electron acceptors towards commercially viable organic solar cells." Chemical Society Reviews 48(6): 1596-1625. [CrossRef]

- Wan, X. , et al. (2020). "Acceptor–donor–acceptor type molecules for high performance organic photovoltaics–chemistry and mechanism." Chemical Society Reviews 49(9): 2828-2842. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. , et al. (2023). "Efficient screening framework for organic solar cells with deep learning and ensemble learning." npj Computational Materials 9(1): 200. [CrossRef]

- Wodo, O. and B. Ganapathysubramanian (2012). "Modeling morphology evolution during solvent-based fabrication of organic solar cells." Computational Materials Science 55: 113-126. [CrossRef]

- Wodo, O. , et al. (2012). "A graph-based formulation for computational characterization of bulk heterojunction morphology." Organic Electronics 13(6): 1105-1113. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. , et al. (2020). "Machine learning for accelerating the discovery of high-performance donor/acceptor pairs in non-fullerene organic solar cells." npj Computational Materials 6(1): 120. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y. , et al. (2019). "Assessing the energy offset at the electron donor/acceptor interface in organic solar cells through radiative efficiency measurements." Energy & environmental science 12(12): 3556-3566. [CrossRef]

- Ye, L. , et al. (2017). "High-efficiency nonfullerene organic solar cells: critical factors that affect complex multi-length scale morphology and device performance." Advanced Energy Materials 7(7): 1602000. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J. , et al. (2020). "Reducing voltage losses in the A-DA′ DA acceptor-based organic solar cells." Chem 6(9): 2147-2161. [CrossRef]

- Yue, Q. , et al. (2020). "n-Type molecular photovoltaic materials: design strategies and device applications." Journal of the American Chemical Society 142(27): 11613-11628. [CrossRef]

- Zawodzki, M. , et al. (2015). "Interfacial morphology and effects on device performance of organic bilayer heterojunction solar cells." ACS applied materials & interfaces 7(30): 16161-16168. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C. , et al. (2020). "Electron-Deficient and Quinoid Central Unit Engineering for Unfused Ring-Based A1–D–A2–D–A1-Type Acceptor Enables High Performance Nonfullerene Polymer Solar Cells with High Voc and PCE Simultaneously." Small 16(22): 1907681. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. , et al. (2019). "Revealing the critical role of the HOMO alignment on maximizing current extraction and suppressing energy loss in organic solar cells." IScience 19: 883-893. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. and C. Ling (2018). "A strategy to apply machine learning to small datasets in materials science." npj Computational Materials 4(1): 25. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.-W. , et al. (2020). "Effect of increasing the descriptor set on machine learning prediction of small molecule-based organic solar cells." Chemistry of Materials 32(18): 7777-7787. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T. , et al. (2019). "Big data creates new opportunities for materials research: a review on methods and applications of machine learning for materials design." Engineering 5(6): 1017-1026. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. , et al. (2019). "Enhanced light-harvesting of benzodithiophene conjugated porphyrin electron donors in organic solar cells." Journal of Materials Chemistry C 7(2): 380-386. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z. , et al. (2018). "High-efficiency small-molecule ternary solar cells with a hierarchical morphology enabled by synergizing fullerene and non-fullerene acceptors." Nature Energy 3(11): 952-959. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).