1. Introduction

Dissociative identity disorder (DID), previously better known as multiple personality, is a chronic and complex condition. Characteristic features include problems with autobiographical memory, and a lack of a sense of unified and coherent identity. The literature indicates that the most common etiological source is the experience of severe trauma, particularly in childhood [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

This publication is a case report of a patient diagnosed with DID at the Department of Psychiatry, Medical University of Bialystok, Bialystok. The description includes the whole process of diagnosis, based on psychiatric-psychological examinations, with particular emphasis on understanding the mechanisms of DID in the psychodynamic model.

Dissociative identity disorder (DID) is characterized by disruption and/or discontinuity in the integration of consciousness, memory (with variable functional amnesia), identity (split personality), emotion, perception, body representation, motor control and behavior [

6,

7]. Depersonalization and derealization are the most common symptoms present in the clinical picture of disorders of the patient's sense of body, surroundings and ‘self’. Disturbed consciousness is the next stage in the developing dissociation, where the patient experiences a reduced ability to respond to external stimuli, while dissociative amnesia protects against re-experiencing difficult autobiographical events that carry the memory of strong stressors and traumas. In turn, dissociation itself destabilizes the sense of identity [

1,

8,

9,

10].

Despite the many studies devoted to the problem of DID, it has not been possible to establish its epidemiology with precision. The prevalence of the described disorder is estimated to be around 1% of the general population, predominating among patients receiving other forms of psychiatric care. These findings suggest that DID is not a rare disorder and that its prevalence is comparable to schizophrenia [

7,

11,

12]. Retrospective studies revealed that a significant proportion of people with a diagnosis of DID, reported experiencing early childhood trauma (before 6 years of age), mainly physical abuse, including sexual abuse [

13,

14,

15].

The DSM-5 Classification includes a new subtype of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) of a dissociative nature, and dissociative disorders are placed immediately after trauma and stress disorders [

6,

16]. This classification order is intended to highlight the important etiological correlation between dissociative PTSD and DID. Research shows similarities in brain activation patterns in both clinical entities, highlighting trauma as a major initiating factor in DID [

2,

15,

17].

Thanks to the growing number of scientific research into the etiology and etiopathogenesis of the phenomenon, it is worth promoting awareness of this issue [

3]. Knowledge of the mechanisms of this problem will enable accurate and reliable diagnosis and the implementation of an individualized therapeutic plan, thereby improving the quality of life of patients and their families. The issues raised by the authors, constitute an original addition to psychiatric knowledge [3,6,10,11,18)].

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Patient Information

A 33-year-old patient, biologically and metrically female, resident of one of the provincial cities in Poland. Somatically healthy, no previous psychiatric hospitalization, not treated for addiction.

The patient has a degree in experimental physics and works as a controller of technical machines. She supports herself and rarely takes sick leave. She reported alternating periods of inability to fulfil timely work duties and when tasks were completed very quickly, for which she was sometimes rewarded by her superiors. She related her difficulties to her switching identities, which was also confirmed by those around her.

The patient had several private appointments with a psychiatrist before presenting to the Department of Psychiatry, who diagnosed schizophrenia, suggested a psychological diagnosis and implemented pharmacotherapy: Olanzapine 5mg/d, Valpropinic acid 1000mg/d. The patient denied the accuracy of the diagnosis and refused to cooperate. Upon leaving the doctor's office, she felt misunderstood and appalled by the specialist's attitude. Wanting to know the source of her difficulties, she reached for scientific publications on Dissociative Identity Disorder, which the psychologist had suggested to her.

Finding Polish and English-language publications, she presented to the Department with a referral to verify the clinical hypotheses. During her hospitalization, she reported that in 2014, a 'voice in her head' appeared, which she identified as thoughts of her own, but belonging to different identities, in her opinion, called 'alters'. In highly stressful and crisis situations, the 'alters' then urged her to make suicidal attempts, despite her well-being.

2.2. Data related to the patient's CV:

(A) Family and background - the respondent described her parents' marriage as ‘incompatible’ and conflictual, and herself as unimportant and disregarded by relatives, functioning as an outsider: ‘I was the youngest and had never been invited anywhere by relatives’.

MOTHER - died three years ago at the age of 68, from brain cancer. The woman was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and syndrome of adult children of alcoholics (ACA). The patient remembers her as emotionally unstable and over-controlling - she would check on her daughter during bath time, monitor her daughter's activity on her private Facebook account.

FATHER - is alive, of retirement age, has suffered a myocardial infarction and stroke, and has an oncological illness - prostate cancer. The patient feels unaccepted by her father, constantly insulted, excessively criticized, compared with her older brother and threatened that she will ‘end up in a lunatic asylum' and, because of her dependency, will not manage in life. The patient’s manifestations of any emotion were punished with shouting by her father, which formed in her the conviction of the reprehensibility of emotions in her life.

BROTHER - with his brother, 8 years older, the patient has a ‘neutral’ relationship. He was suspected of having attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

SISTER - died at a young age, no details of relationship with sister or how she functioned in the family system.

GRANDFATHER - the patient's grandfather (on her father's side) was addicted to alcohol and died because of it. He went down in her memoirs as ‘rowdy and constantly drunk’.

MALE COUSIN (from her mother's side) - the patient does not maintain contact with him. According to what she reported, the man murdered his wife at her own request (for unknown reasons) and is currently in prison.

(B) Education, peer group - the patient graduated in experimental physics (defended her thesis) and is gainfully employed. She functioned on the sidelines in peer circles, did not feel liked, and escaped into her world of dreams and fantasies.

(C) Sexual development, gender identity - the patient, during her college years, made her first attempt at a romantic relationship with a fellow student, but was not satisfied. Exploring her sense of sexual identity and orientation, while identifying as a bisexual woman, she became involved with a female partner with an emotionally unstable personality. The relationship was turbulent, and the patient observed gaps in her memory and volatile behavior. She shared her experiences with her partner at the time, who suggested multiple personality and referred her to scientific publications. After the break-up of the relationship, the patient's dissociative states intensified, which she related to the strong and extreme emotions governing the relationship. At the same time, the patient's mother also died, and her father's behavior contributed to the dissociation from the emotional sphere. The patient was accused by her former female partner of rape and sexual abuse, which she did not remember. It was then that she first sought the help of a psychologist.

Currently, the patient is in a relationship with a woman who, due to her concern about her partner's condition, motivated her to deepen her diagnosis.

(D) Nuclear family - the patient and her female partner, together for several months, have been sharing a household, they have a cat (to which some of the patient's alternative personalities declare she is allergic). The women talk about DID issues, so that the patient feels understood and accepted. She admitted that some of her alters remain in a relationship with her girlfriend. The partner, due to Asperger's Syndrome, diagnosed in early childhood, also receives specialist support.

3. Clinical Findings

Laboratory and neuroimaging diagnostics, including morphology, electrolytes, liver tests, glucose, renal tests, ECG, MRI and EEG [

18,

19], did not reveal abnormalities.

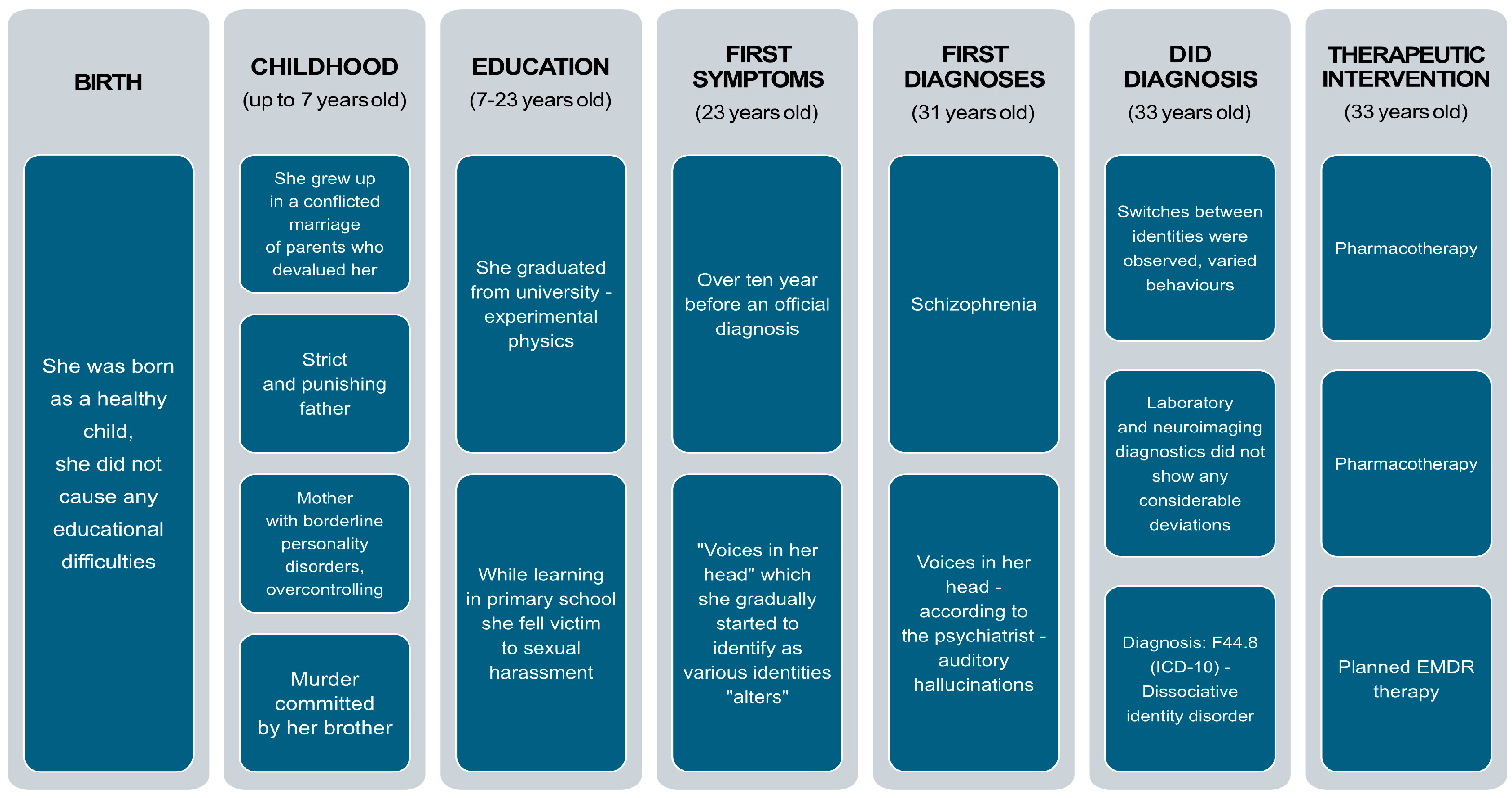

4. Timeline

Figure 1.

Historical and current information from this episode of care.

Figure 1.

Historical and current information from this episode of care.

5. Diagnostic Assessment

The patient's interview was very difficult to collect, due to switching alters, especially when discussing difficult topics. To complete the diagnosis, the DES-R PL Scale (Dissociative Experiences Scale - Revised, Polish version) and the Minnesota Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire MMPI-2 were used [

20,

21,

22].

On the DES-R PL scale, the patient significantly exceeded the cut-off point, scoring 179pts, while the personality profile obtained on the MMPI-2, bore the hallmarks of aggravation. However, it was subjected to detailed analysis and careful interpretation.

The patient was born as a healthy child, developed normally and had no educational difficulties. She reported discopathy and a single repositioning of a tibial fracture. She did not experience serious head injuries with loss of consciousness or epileptic seizures. She was diagnosed at the Neurology Outpatient Clinic, due to a single episode of dissociative seizures; epilepsy was ruled out. To date, she has not been hospitalized psychiatrically or in detox. She did not take medication on a permanent basis. She had repeatedly engaged in self-destructive behavior - she had harmed herself on her forearms and thighs with a razor blade. On one occasion, manifestly, she made a suicidal attempt, by hanging herself using a trouser belt.

She drinks alcohol and smokes cigarettes occasionally, depending on the dominant identity at the time. She has not tried other psychoactive substances, as confirmed by all personalities.

She had no criminal record and had never had probation supervision.

During the appointments, the patient was correctly auto and allopsychically oriented, with clear awareness. No clinically significant memory or attention disorders were observed. She did not reveal disturbances in the flow and pace of thought, but periodically she displayed illogical structure. She made variable eye contact with the examiner and shortened her distance. She spoke in a sensible, excessively digressive manner. Fluctuating states of identity (switches) were observed, with accompanying fluctuating moods and fluctuating psychomotor drive. Affect was adequate to the spoken content, periodically maladjusted. She reported the presence of anxiety, psychosomatic complaints, intrusive thoughts and episodes of panic anxiety. She did not disclose acute psychotic productions in the form of delusions and hallucinations. She denied suicidal thoughts and tendencies. She did not report somatic complaints, except for a dysregulated diurnal cycle.

The data collected suggested the presence of mixed cluster B personality disorder - histrionic, emotionally unstable, narcissistic and antisocial personality traits (according to the DSM-5 Classification) [

16].

Psychological Assessment

The patient is characterized by generalized anxiety and low self-esteem. The woman has a negative attitude towards authorities, is reluctant to conform, and can sometimes be irritable. She declares the presence of problems in the family and is prone to interpersonal conflicts. She confirms the presence of persecutory thoughts and bizarre sensory experiences. She reports a lack of Ego control in the cognitive sphere and difficulties in maintaining control. Lack of observing Ego, resulting in inability to judge reality as others see it. She feels socially alienated, lonely and has difficulty establishing and maintaining mature relationships based on intimacy and commitment. Interpersonal relationships are characterized by instability and turbulence, ranging from states of idealization to devaluation, which constitutes a mechanism that sustains her psychopathology. She makes a desperate effort to avoid imagined rejection by others. She is characterized by empathy deficits, emotional immaturity, she is labile and lacks the ability to defer gratification. She is not in touch with her emotional sphere, which limits gaining insight. She uses numerous immature defense mechanisms based on regression. The patient does not have sufficient resources to cope effectively with everyday difficulties, her sense of self is disturbed (clear and permanently unstable image of herself and of her own Self), resulting in giving away responsibility by creating additional personalities (human and animal ones). She may display impulsive, 'acting-out' behavior. She may be maladjusted, may feel anger and have difficulty controlling it. In stressful situations, transient paranoid imagery and very intense dissociative symptoms may occur. In addition, the patient displays specific interests in multiple personality themes and her unconstructive ways of functioning are reinforced by those in her immediate surroundings. During the psychotherapeutic consultation, she declared her willingness to continue working on herself [

23,

24,

25].

On the basis of the material collected (observation, interview, analysis of psychological and psychiatric examinations carried out), based on the current ICD-10 Classification, the patient described was diagnosed with: F44.81 - dissociative identity disorder and F61 - mixed personality disorder [

26,

27].

6. Therapeutic Intervention

During hospitalization, the following pharmacotherapeutic drugs were included: Anafranil SR (Clomipramine) 75mg DS 0-0-1; Ketrel (Quetiapine) XR 50mg DS 0-0-1; Symla (Lamotrigine) 50mg DS 0-0-1 and ad hoc Relanium (Diazepam), for severe anxiety, fear. No adverse effects were observed during pharmacotherapy. During her stay at the Clinic, the patient participated in psychotherapeutic talks, occupational therapy and other forms of therapeutic interventions proposed.

7. Follow-up and Outcomes

In the dissociative identity disorder of the case described, defense mechanisms serve to survive and protect against traumatic experiences. The patient, after discharge from hospital, undertook psychotherapy in a psychodynamic approach. The psychotherapist, during the first meetings, focused on building a safe therapeutic relationship and then on helping her to understand the disorder and the accompanying mechanisms of dissociation. The patient initially displayed an oppositional and rebellious attitude, but her motivation to work increased over time. Relaxation techniques were introduced to support the patient in coping with sudden changes in identity and emotions. During moments of 'switching', the woman was allowed to speak freely of the alter, but therapeutic dialogue was only undertaken with the underlying personality.

7.1. In the Case Described, the Presence of the Following Defense Mechanisms Was Identified [24,28,29]:

1. Splitting, used by the examined person to dissociate from emotions, thoughts and traumatic memories, blocking their access to consciousness. In effect, the mechanism leads to the differentiation of the alters, thus maintaining a relatively constant homeostasis.

2. Dissociation, whereby the examined person isolates or separates aspects of personality and experience in order to protect the psyche from traumatic experiences. This mechanism leads to the emergence of different identities, each of which has an assigned role in coping with the trauma and allows protection of the self.

3. Projection, allows the patient to project her own emotions, thoughts and traits onto other alter identities and people. The examined person thus avoids confronting her own emotions and experiences.

4. Affective isolation, based on the avoidance of feeling and expressing emotions, helps the patient to maintain the seemingly calm 'surface of the Self structure'.

5. Denying traumatic memories and events enables the patient to avoid acknowledging their existence and significance.

6. The reverse reactions applied by the examined person, which consist of experiencing opposite feelings and behaviors towards the same events or people, result from the creation of different alternative identities.

7. The denial mechanism allows the patient to minimize and/or deny the negative impact of traumatic events on her life.

8. Amnesia of part of the events, feelings or identities of the alters, allows the examined person to avoid feeling the anxiety associated with the trauma.

7.2. The Subsequent Stages of Therapeutic Interventions

Subsequent stages of the therapy will focus on the integration of individual alternative identities into a central identity or the creation of a new personality, integrating the others. A necessary therapeutic intervention will consist in the reworking of traumatic memories and experiences, generating dissociative disorders. To this end, it is planned to use elements of EMDR therapy, as a method to support the psychotherapeutic process [

18,

23,

24,

25,

30,

31].

The therapeutic interventions will be long-term and gradual, in order to sustain constructive change and minimise the risk of re-disintegration, however, thanks to the patient's professional support and commitment and motivation, the prognosis is optimistic [

23,

24,

30].

8. Discussion

DID is a multidimensional and chronic state of dissociation, characterized by the presence of two or more separate identity states, with a marked discontinuity of the sense of self, manifested by disturbances of affect, memory, perception, behavior and consciousness, and sometimes sensory and movement disorders [

2,

6,

13,

20].

Research reports, in the etiopathogenesis of the disorder, point to the important role of community factors, such as sexual abuse during childhood or violence during adolescence, as well as genetic factors, such as the polymorphism of the rs25531 allele of the serotonin transporter gene promoter and the Val158Met allele of catechol-o-methyltransferase. A smaller volume of the amygdala and hippocampus was also observed, compared to the size of these structures in individuals without DID, which may explain the presence of emotional and memory disturbances simultaneously [

1,

14,

17,

18,

32,

33,

34].

In addition, this entity can coexist with other psychiatric and somatic illnesses (as confirmed by the case of the patient described by the authors), so the presence of another mental illness does not constitute an absolute exclusion of DID [

5,

7].

One reason for the diagnostic difficulties is the widespread belief that this clinical entity is extremely rare, as well as the limited knowledge about it. The described 33-year-old woman with a diagnosis of dissociative disorder (DID), hospitalized psychiatrically for the first time, reported feelings of discomfort, social alienation, suicidal thoughts and manifested the presence of 46 personalities, including: male (K. - displaying violent tendencies, aggressive; W. - intellectual, psychotherapist), female (A. - emotional alter, alienated, drinking beer and smoking cigarettes; G. - Host, managing other alters, opposed to personality integration; M. - gatekeeper, controlling access to other personalities), as well as an animal character - the cat.

According to the current state of knowledge, dissociative disorders represent an underestimated and under-recognized clinical diagnosis, hence the authors have made an in-depth analysis and description of the case, including therapeutic strategies, which distinguishes the paper from the available literature. The authors' aim in preparing this paper was to promote knowledge of the symptomatology of DID and to emphasize the importance of a holistic and individualized approach to the patient [

1,

2,

3,

7,

18].

9. Patient Perspective

Thanks to the accurate diagnosis, the described patient declared a sense of relief: ‘For a long time I had not known what was happening to me, I thought I was possessed. I am grateful for the diagnosis. I received effective stabilising drug treatment. Psychotherapy although hard will hopefully allow me to recover completely in the future’.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org,

Figure 1. Historical and current information from this episode of care.

Author Contributions

OW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SCJ: Writing – review & editing. WN: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed Consent Statement

The patient was informed about the publication of the medical case and provided written informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

References

- Orlof, W.; Wilczyńska, K.M.; Waszkiewicz, N. Dysocjacyjne zaburzenie tożsamości (osobowość mnoga) — powszechniejsze niż wcześniej sądzono. Psychiatria 2018, 15(4), 228–233. Available at https://journals.viamedica.pl/psychiatria/article/view/59802.

- Reinders, A.A.T.S.; Veltman, D.J. Dissociative identity disorder: out of the shadows at last? Br. J. Psychiatry 2021, 219(2), 413–414. [CrossRef]

- Lebois, L.A. M.; Ross, D.A.; Kaufman, M.L. “I Am Not I”: The Neuroscience of Dissociative Identity Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 91(3), e11–e13. [CrossRef]

- Boysen, G.A. Dissociative Identity Disorder: A Review of Research From 2011 to 2021. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2024, 212(3), 174–186. [CrossRef]

- Şar, V. The many faces of dissociation: opportunities for innovative research in psychiatry. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2014, 12(3), 171–179. [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, D.; Lewis-Fernández, R.; Lanius, R.; Vermetten, E.; Simeon, D.; Friedman, M. Dissociative disorders in DSM-5. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9(1), 299–326. [CrossRef]

- Orlof, W.; Rozenek, E.B.; Waszkiewicz, N.; Szewczak, B. Dissociative identity (multiple personality) disorder in Poland: a clinical case description and diagnostic difficulties. Postępy Psychiatrii i Neurologii 2021, 30(3), 213–218. [CrossRef]

- Jedlecka, W. The notion of “the dissociation” – fundamental issues. Filoz. Publiczna Eduk. Demokr. 2018, 3(2), 97–110.

- Brand, B.L.; Myrick, A.C. Dissociative disorders. In Translating Research into Practice: A Desk Reference for Practicing Mental Health Professionals; Grossman, L., Walfish, S., Eds.; Springer Publishing: New York, 2014; pp 187–189.

- Barton, N. Dissociative identity disorder. In Gabbard’s Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders; Gabbard, G.O., Ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, 2017; pp 439-445.

- Şar, V.; Akyuz, G.; Dogan, O. Prevalence of dissociative disorders among women in the general population. Psychiatry Res. 2007, 149(1–3), 169–176. [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.A. Epidemiology of multiple personality disorder and dissociation. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 1991, 14(3), 503–517.

- Şar, V.; Mutluer, T.; Necef, I.; Fatih, P. Trauma, Creativity, and Trance: Special Ability in a Case of Dissociative Identity Disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175(6), 506–507. [CrossRef]

- Savitz, J.B.; Van Der Merwe, L.; Newman, T.K.; Solms, M.; Stein, D.J.; Ramesar, R.S. The relationship between childhood abuse and dissociation. Is it influenced by catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) activity? Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008, 11(2), 149–161. [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.A.; Ridgway, J.; Neighbors, Q.; Myron, T. Reversal of Amnesia for Trauma in a Sample of Psychiatric Inpatients with Dissociative Identity Disorder and Dissociative Disorder Not Otherwise Specified. J. Child Sex Abus. 2022, 31(5), 550–561. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association, Office of Mental Disorders. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5; Arlington, 2013. Available at https://www.sciencetheearth.com/uploads/2/4/6/5/24658156/dsm-v-manual_pg490.pdf.

- Chalavi, S.; Vissia, E.M.; Giesen, M.E.; Nijenhuis, E.R.S.; Draijer, N.; Cole, J.H.; et al. Abnormal hippocampal morphology in dissociative identity disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder correlates with childhood trauma and dissociative symptoms. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2015, 36(5), 1692–1704. [CrossRef]

- Saxena, M.; Tote, S.; Sapkale, B. Multiple Personality Disorder or Dissociative Identity Disorder: Etiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Cureus 2023, 15(11), e49057. [CrossRef]

- Reinders, A.A.T.S.; Marquand, A.F.; Schlumpf, Y.R.; Chalavi, S.; Vissia, E.M.; Nijenhuis, E.R.S.; et al. Aiding the diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder: pattern recognition study of brain biomarkers. Br. J. Psychiatry 2019, 215(3), 536–544. [CrossRef]

- Tomalski, R.; Pietkiewicz, I. Rozpoznawanie i różnicowanie zaburzeń dysocjacyjnych – wyzwania w praktyce klinicznej. Czasopismo Psychologiczne 2019, 25(1), 43–51.

- Brand, B.L.; Chasson, G.S.; Palermo, C.A.; Donato, F.M.; Rhodes, K.P.; Voorhees, E.F. MMPI-2 Item Endorsements in Dissociative Identity Disorder vs. Simulators. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 2016, 44(1), 63–72.

- Pietkiewicz, I.J.; Hełka, A.M.; Tomalski, R. Validity and reliability of the revised Polish online and pen-and-paper versions of the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DESR-PL). Eur. J. Trauma Dissociation 2019, 3(4), 235–243. [CrossRef]

- Subramanyam, A.A.; Somaiya, M.; Shankar, S.; Nasirabadi, M.; Shah, H.R.; Paul, I.; et al. Psychological Interventions for Dissociative disorders. Indian J. Psychiatry 2020, 62(Suppl 2), S280–S289. [CrossRef]

- Barach, P.M.; Comstock, C.M. Psychodynamic Psychotherapy of Dissociative Identity Disorder. In Handbook of Dissociation; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1996; pp 413–429.

- Spermon, D.; Darlington, Y.; Gibney, P. Psychodynamic psychotherapy for complex trauma: targets, focus, applications, and outcomes. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2010, 3, 119–127. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. IACAPAP e-Textbook of child and adolescent mental health, 2013. Available at https://iacapap.org/_Resources/Persistent/9fc773413bcb960e30a7a67494153aea1503eeb7/A.1-ETHICS-072012.pdf.

- Pużyński, S.; Wciórka, J. Klasyfikacja zaburzeń psychicznych i zaburzeń zachowania w ICD-10. Opisy kliniczne i wskazówki diagnostyczne; Vesalius: Kraków, 2000.

- Costa, R.M. Dissociation (Defense Mechanism). In Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp 1165–1167.

- Kampe, L.; Bohn, J.; Remmers, C.; Hörz-Sagstetter, S. It’s Not That Great Anymore: The Central Role of Defense Mechanisms in Grandiose and Vulnerable Narcissism. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Saxe, G.N.; van der Kolk, B.A.; Berkowitz, R.; Chinman, G.; Hall, K.; Lieberg, G.; et al. Dissociative disorders in psychiatric inpatients. Am. J. Psychiatry 1993, 150(7), 1037–1042. [CrossRef]

- Gentile, J.P.; Dillon, K.S.; Gillig, P.M. Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for patients with dissociative identity disorder. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 10(2), 22–29. Available at https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3615506/pdf/icns_10_2_22.pdf.

- Pieper, S.; Out, D.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; van Ijzendoorn, M.H. Behavioral and molecular genetics of dissociation: The role of the serotonin transporter gene promoter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR). J. Trauma Stress 2011, 24(4), 373–380. [CrossRef]

- Koenen, K.C.; Saxe, G.; Purcell, S.; Smoller, J. W.; Bartholomew, D.; Miller, A.; et al. Polymorphisms in FKBP5 are associated with peritraumatic dissociation in medically injured children. Mol. Psychiatry 2005, 10(10), 1058–1059. [CrossRef]

- Vermetten, E.; Schmahl, C.; Lindner, S.; Loewenstein, R. J.; Bremner, J. D. Hippocampal and amygdalar volumes in dissociative identity disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163(4), 630–636. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).