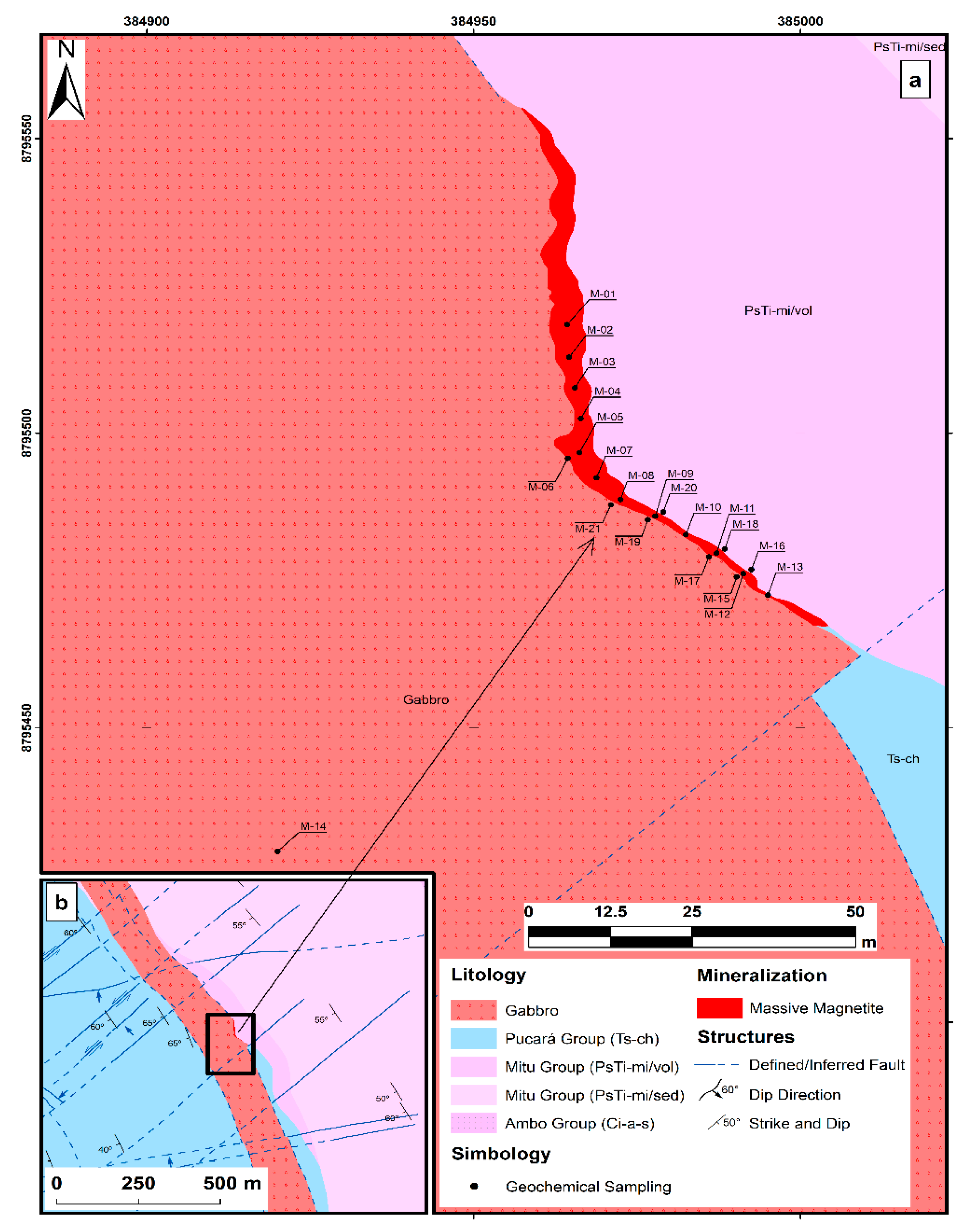

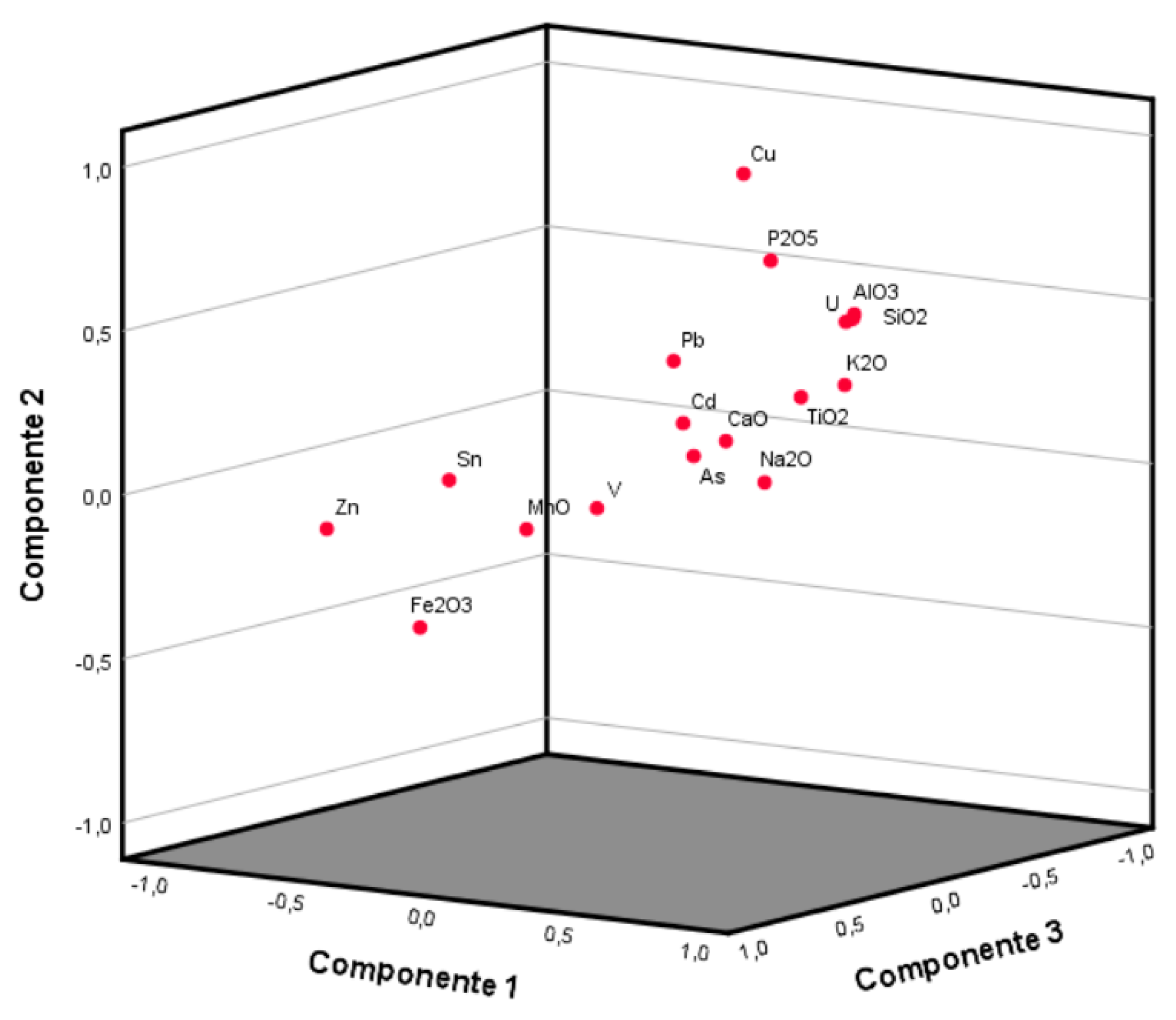

3.1. Multi-Element Geochemistry

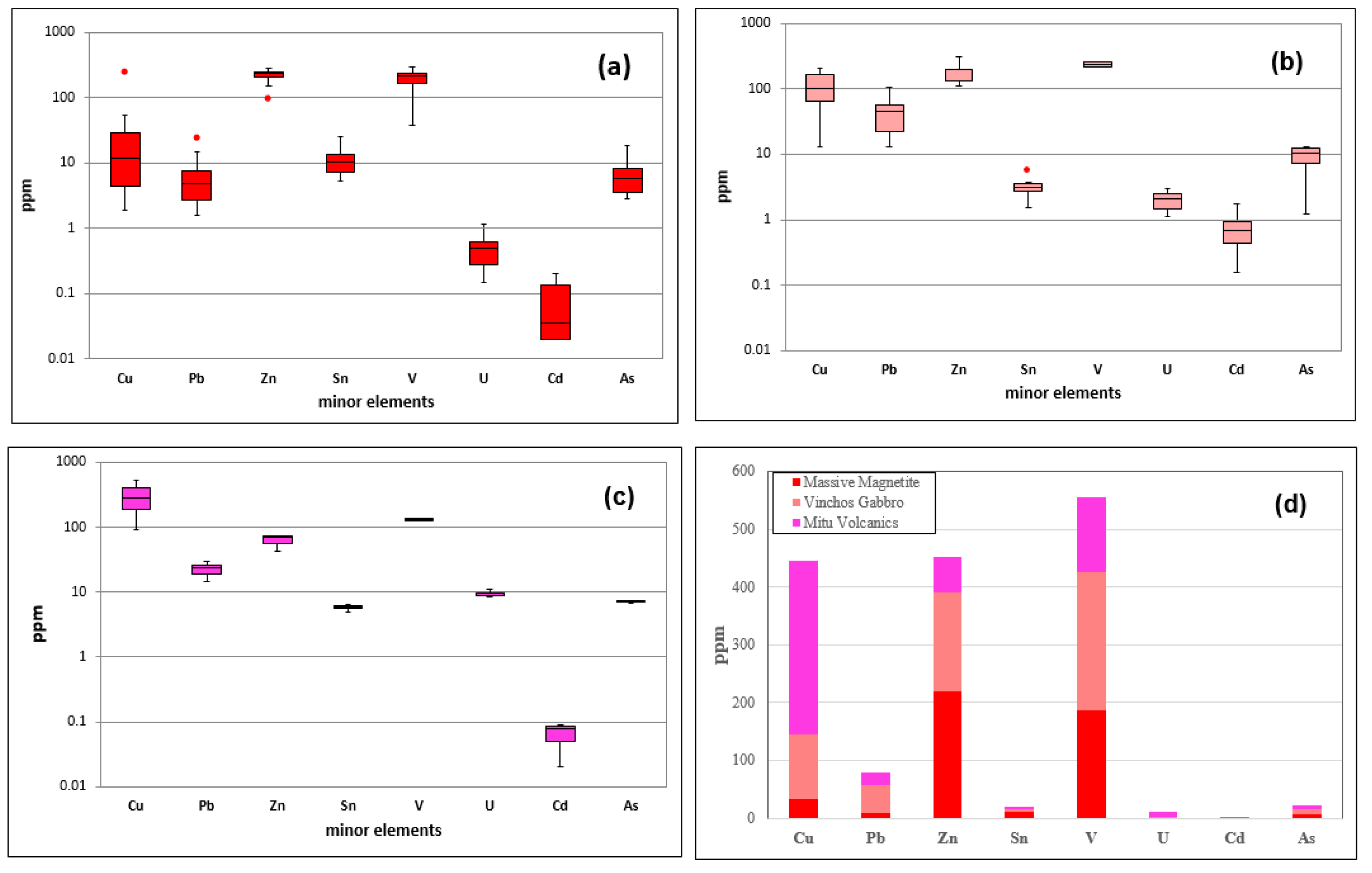

The comparison of minor elements in the three types of rocks massive magnetite, Winchos Gabbro, and Mitu volcanic rocks—reveals distinctive geochemical patterns that reflect their formation environments and potential mineralization. The massive magnetite (

Figure 5a) is characterized its high Fe₂O₃ content, ranging from 68.8% to 87.3%, and in V concentration (up to 294 ppm), typical of vanadiferous magnetite de-posits. The presence of Zn (98–278 ppm) is also significant, although relatively low, while Cu (2.8–53.5 ppm) and Pb (1.9–25.4 ppm) exhibit variability, suggesting specific mineral associations and the possible inclusion of minor phases or hydrothermal alter-ation processes that enrich these zones in copper and lead. The Winchos gabbro (

Figure 5b) exhibits a low to moderate Fe₂O₃ content (11.6–16.1%), indicating its mafic nature. This type of rock displays anomalies in Cu concentrations, ranging from 8.1 to 210 ppm, which can be considered sub-economic or prospectively interesting depending on the geological context and exploration potential, and Pb reaching up to 179 ppm, re-flecting an affinity with these elements within the mafic matrix. V concentration in the gabbro shows anomalies, reaching up to 305 ppm, which may be associated with min-erals like magnetite and titanomagnetite, typical of vanadium-rich Gabbros, suggest-ing an anomalous enrichment in the area. This enrichment could be of prospectively interesting for further exploration. The levels of Zn (up to 107.5 ppm) and U (up to 2.99 ppm) suggest that the Winchos gabbro may also contain minor phases of zinc and uranium, without reaching the anomalies detected in the volcanics. The Mitu volcanic rocks (

Figure 5c) present significant anomalies in Cu, with concentrations ranging from 280 to 529 ppm, and in U, reaching up to 10.85 ppm, suggesting a formation environment that may have included hydrothermal processes responsible for these anomalies in copper and uranium. This behavior contrasts with Zn levels (29.3–57.3 ppm) and Fe₂O₃ (15.5–23.4%), which are common in volcanic rocks of intermediate to felsic composition. These patterns suggest that the Mitu volcanic rocks have significant potential for copper and uranium exploration, while the massive magnetite is promising for iron and vanadium exploitation, and the Winchos gabbro shows potential in copper, lead, and vanadium, reflecting its mafic composition.

Table 1 summarizes the concentrations of trace elements in massive magnetite, Winchos gabbro, and Mitu volcanics, showing clear differences that reflect their metallogenic potentials and formation environments. Massive magnetite is characterized by a mean copper (Cu) of 32.85 ppm, with values ranging from 1.9 to 53.5 ppm, and a median of 12 ppm, indicating a moderate concentration with variability in some samples. Vanadium (V) shows a high mean of 187.21 ppm and reaches a maximum of 294 ppm, confirming its affinity with the magnetite structure, while zinc (Zn) has a median of 238.5 ppm, indicating a significant presence compared to lead (Pb), which has a median of 4.75 ppm. In the Winchos gabbro, Cu shows a high mean of 110.93 ppm and a range of 13.2 to 210 ppm, with a median of 101.25 ppm, suggesting a uniform distribution and greater capacity to host copper. Pb in the gabbro has a mean of 47.95 ppm and reaches up to 107.5 ppm, indicating possible compatibility with mafic phases. V, with a mean of 237.83 ppm and a median of 242.5 ppm, is also prominent, similar to magnetite. The Mitu volcanics are notable for strong Cu enrichment, with a mean of 299.83 ppm and a maximum of 529 ppm, reflecting significant potential for copper mineralization, while uranium (U) reaches a mean of 9.367 ppm and a maximum of 10.85 ppm, possibly associated with hydrothermal processes. Zn has a median of 56 ppm, and V has a relatively low mean of 130.33 ppm. Therefore, massive magnetite is particularly rich in V and Zn, Winchos gabbro in Cu and Pb, and Mitu volcanics in Cu and U, suggesting that the latter are especially promising for copper and uranium exploitation, while magnetite and gabbro are potential sources of vanadium, zinc, and lead.

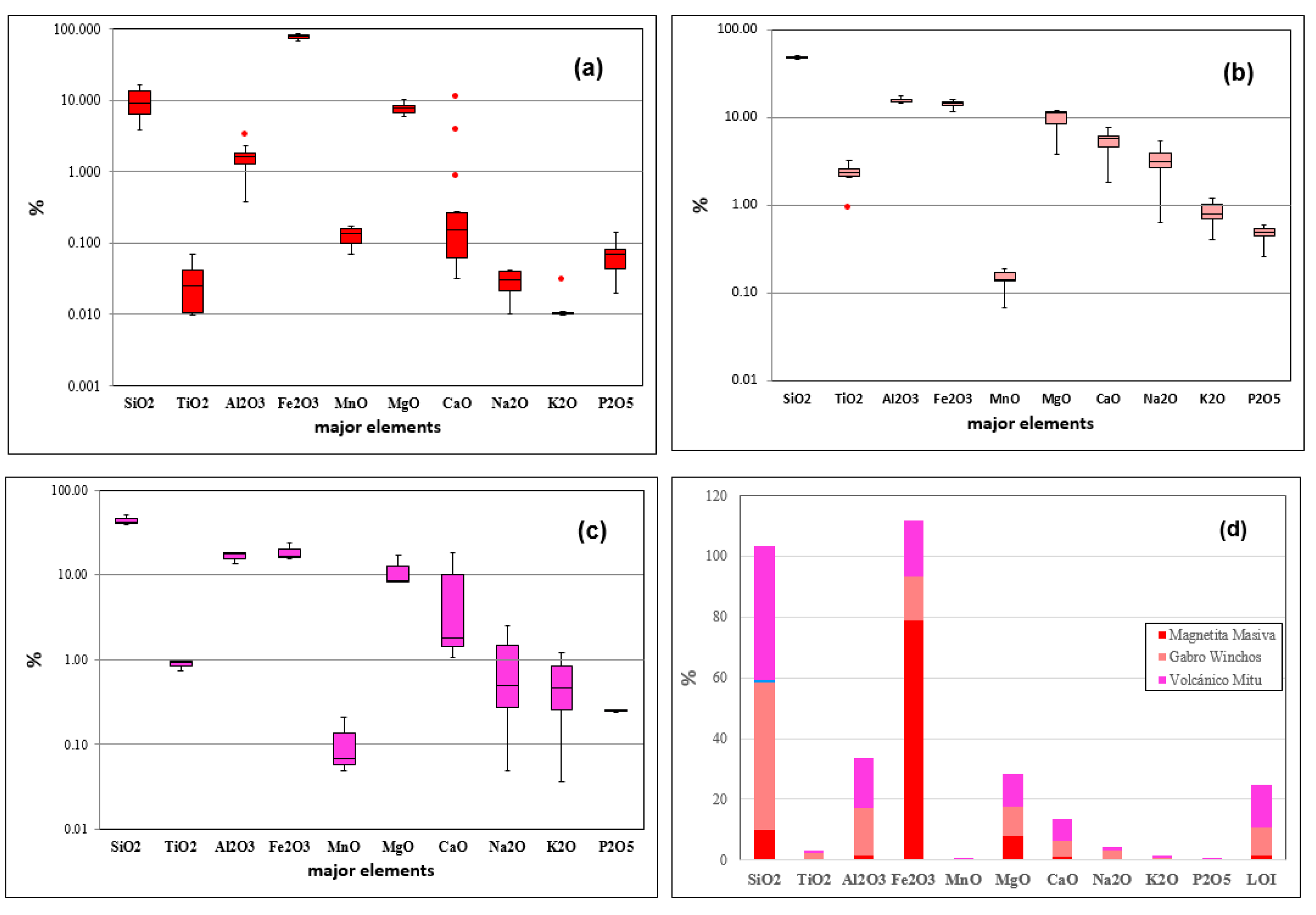

Figure 6 presents the concentrations of major elements in three rock types: massive magnetite, Winchos gabbro, and Mitu volcanics, expressed as percentages. This analysis reveals significant compositional variations that reflect the formation environments of each rock type and their mineralogical potentials. In the massive magnetite (

Figure 6a), the Fe₂O₃ content is predominantly high, ranging from 68.76% to 87.30%, which confirms its nature as an iron deposit. The silica (SiO₂) content is low, with values between 3.81% and 16.60%, indicating that the magnetite is not significantly contaminated with other silicates. The other oxides present lower concentrations; Al₂O₃ ranges from 0.77% to 2.33%, while TiO₂, CaO, Na₂O, and K₂O are present in minimal concentrations (generally below 0.1%), reflecting the relative purity of the massive magnetite and the limited inclusion of accessory minerals. The Winchos gabbro (

Figure 6b) shows a more complex and diversified composition compared to massive magnetite. Fe₂O₃ in this type of rock is significantly lower, ranging between 11.55% and 15.55%, which is characteristic of mafic rocks and reflects its lower total iron content. However, the concentrations of SiO₂ are much higher (46.69% to 51.42%), which is typical of gabbros. Al₂O₃ reaches up to 17.78%, and TiO₂ ranges between 2.18% and 3.28%, suggesting the presence of aluminum- and titanium-rich mineral phases, such as feldspars and possibly ilmenite. MgO and CaO are also significant, with maxima of 12.07% and 7.78%, respectively, indicative of the presence of mafic minerals such as pyroxenes and calcic plagioclase. In the Mitu volcanics (

Figure 6c), Fe₂O₃ shows an intermediate range of concentrations (15.5% to 23.44%), reflecting a moderate iron content compared to gabbro and magnetite. SiO₂ in these volcanic rocks ranges from 39.01% to 41.49%, suggesting an andesitic or basaltic composition. Al₂O₃ values are similar to those in gabbro (13.5% to 18.29%), while TiO₂ is lower (0.74% to 0.97%), which is consistent with the composition of intermediate volcanic rocks. Additionally, CaO reaches up to 18.19%, and MgO and P₂O₅ are present in notable concentrations (up to 8.17% and 0.59%, respectively), indicating the presence of calcic phases and phosphates, typical of volcanic contexts. Each rock type exhibits a unique composition: massive magnetite is rich in Fe₂O₃ and poor in silicates; Winchos gabbro contains high levels of SiO₂, Al₂O₃, TiO₂, and CaO, reflecting its mafic character; and Mitu volcanics possess an intermediate composition with elevated levels of Fe₂O₃, SiO₂, and CaO, indicating a volcanic environment with potential for forming calcic minerals and phosphates.

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics of the major elements in three rock types: massive magnetite, Winchos gabbro, and Mitu volcanics, showing significant compositional variations. In massive magnetite, Fe₂O₃ dominates with an average of 79.08%, ranging from 68.76% to 87.33%, reflecting its high iron content. SiO₂ has a low average of 9.97%, with values between 3.81% and 16.60%, suggesting a low presence of silicates. Al₂O₃ ranges from 0.38% to 2.33%, with an average of 1.60%, while TiO₂, CaO, Na₂O, and K₂O are nearly absent (generally <0.1%), indicating high iron purity. In the Winchos gabbro, Fe₂O₃ is significantly lower, with an average of 14.29% and a range of 11.55% to 16.13%, typical of mafic rocks. SiO₂ reaches an average of 48.36%, with a maximum of 51.42%, reflecting the siliceous nature of gabbro. Al₂O₃ shows an average of 15.60%, with values reaching 17.78%, while TiO₂ ranges from 2.09% to 3.28%, suggesting the presence of aluminum- and titanium-rich minerals such as ilmenite and feldspars. MgO and CaO are significant, with averages of 9.56% and 5.24%, respectively, indicating mafic mineralogy. In the Mitu volcanics, Fe₂O₃ has an average of 18.49%, ranging from 15.53% to 23.44%, indicating an intermediate composition. SiO₂ has an average of 43.97%, with a maximum of 51.42%, typical of volcanic rocks of andesitic to basaltic type. Al₂O₃ ranges from 13.50% to 18.29% (average of 16.52%), while TiO₂ is low, with an average of 0.88%. High CaO values (average of 7.02%, maximum of 18.19%) and MgO (average of 11.16%, maximum of 16.84%) suggest the presence of calcic phases and mafic minerals, characteristic of volcanic environments. In conclusion, massive magnetite is extremely rich in Fe₂O₃, Winchos gabbro shows high levels of SiO₂ and Al₂O₃ with mafic characteristics, and Mitu volcanics have an intermediate composition with elevated CaO and MgO, highlighting their lithological diversity and mineralogical potential.

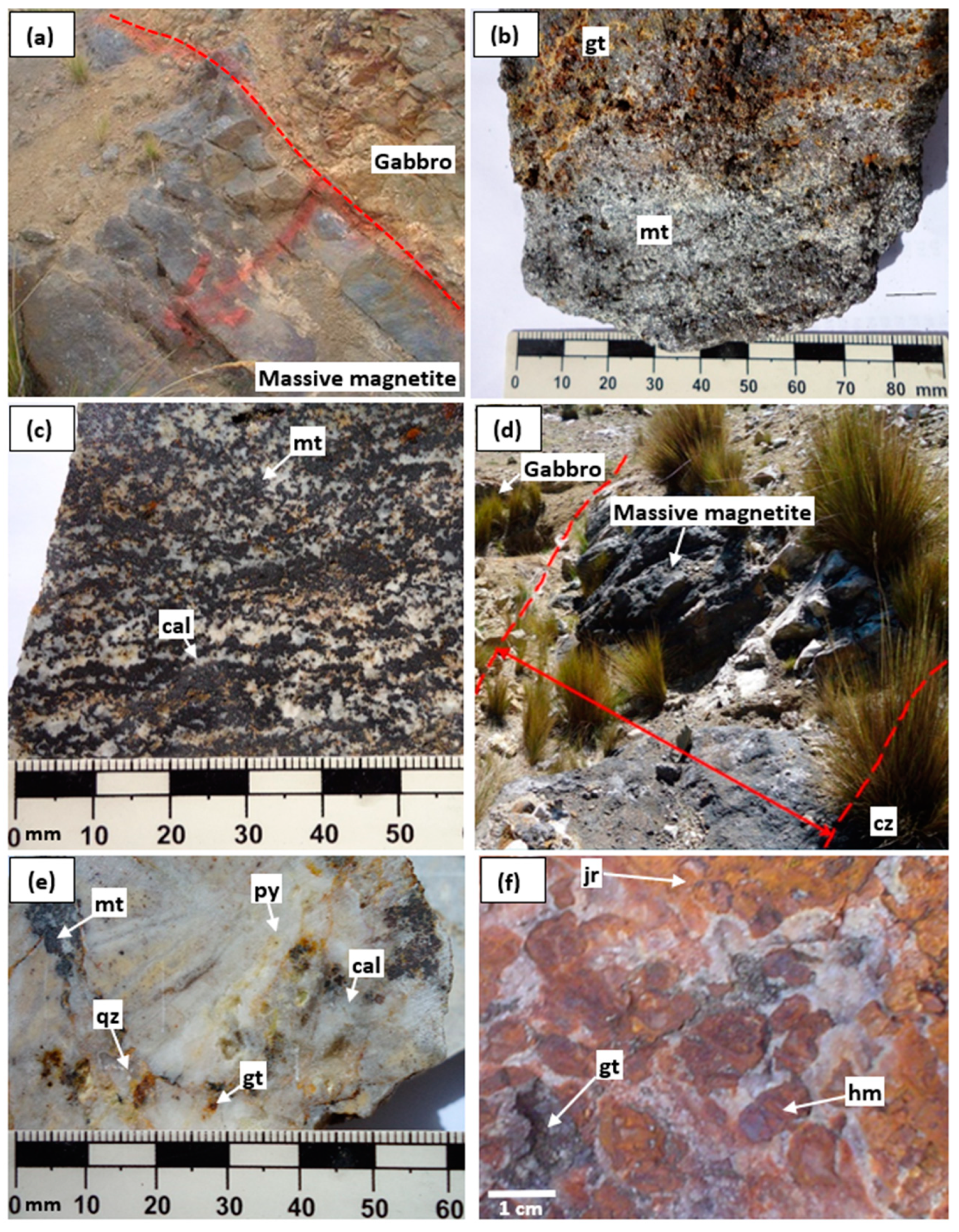

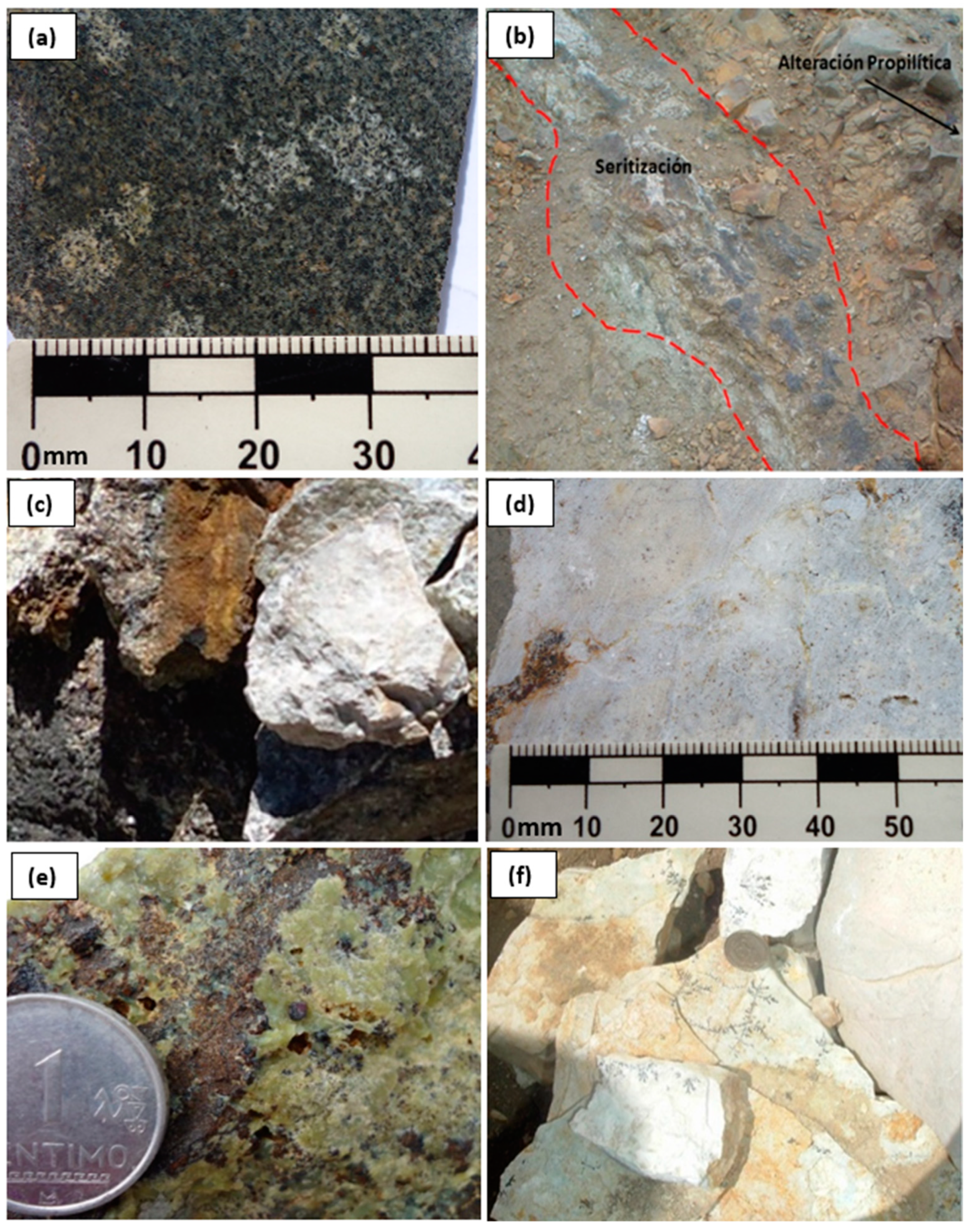

3.2. Genesis of Magnetite Mineralization

La

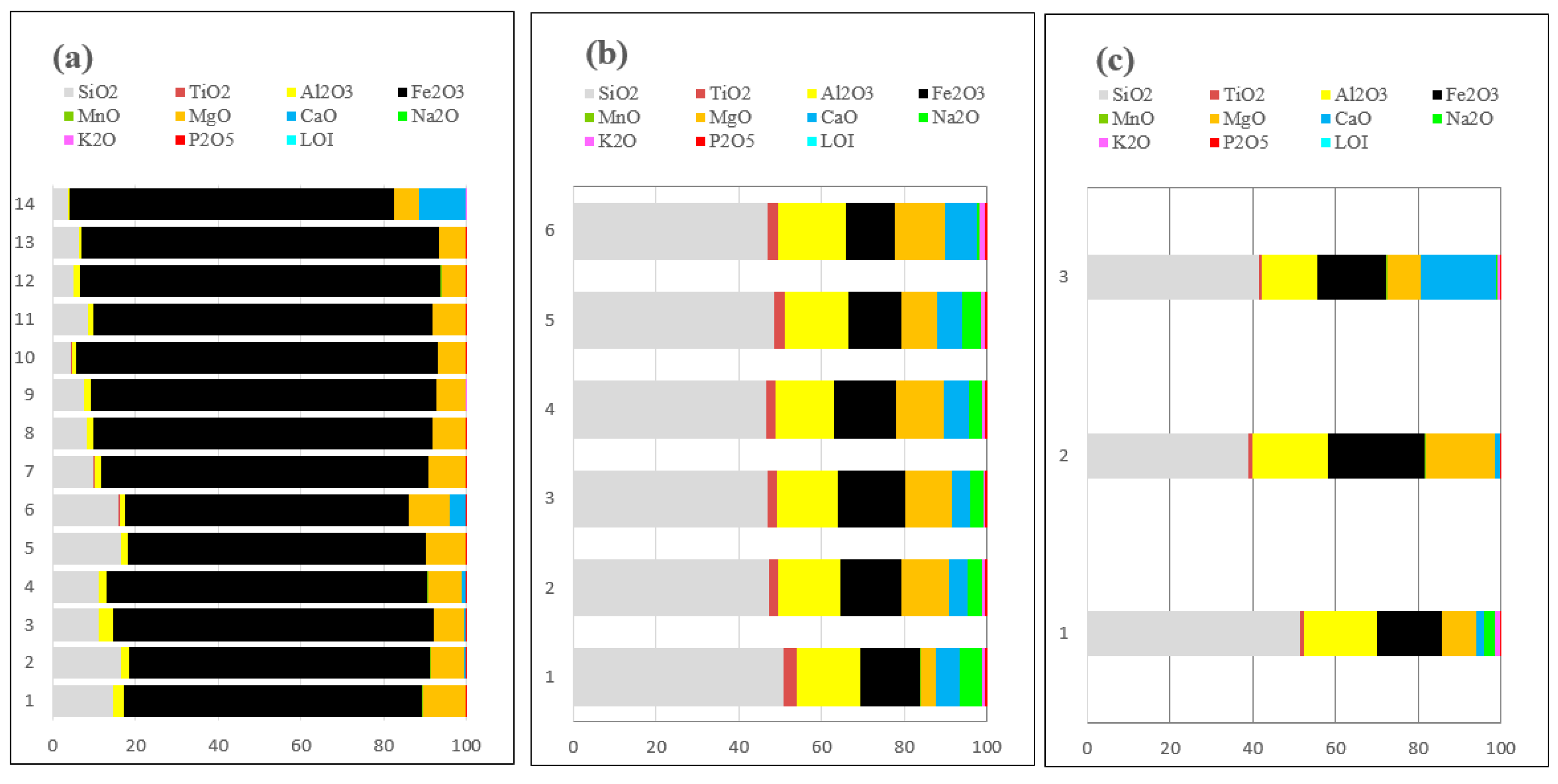

Figure 7 shows the concentrations of major oxides in various lithologies, including massive magnetite, Winchos gabbro, Mitu volcanics, and the Tapo Massif [

26], adjusted to 100% with the loss on ignition (LOI) considered, providing an accurate view of the mineralogical content in the context of carbonates and alteration processes. The massive magnetite (

Figure 7a) is notable for its high Fe₂O₃ concentration, ranging from 68.75% to 87.32%, indicating a very pure iron deposit associated with the replacement of magnetite in marbles of the Chambará Formation. This suggests that Fe₂O₃ was released and available for mobilization in the hydrothermal system, favoring the formation of iron mineralization in contact with carbonates. The Mitu volcanics (

Figure 7b) show Fe₂O₃ contents ranging from 15.53% to 23.44%, indicating that these igneous bodies may have contributed iron to the hydrothermal system, aiding magnetite mineralization in areas of interaction with limestones. Additionally, SiO₂ in the Mitu volcanics presents high values (39.01% to 51.41%), suggesting an intermediate to felsic composition that could facilitate the transport of Fe via magmatic fluids. The presence of other oxides, such as Al₂O₃ (13.50% to 18.29%) and CaO (up to 18.19%), supports the role of the Mitu volcanics as sources of elements in the system. The Winchos gabbro (

Figure 7c) presents Fe₂O₃ in the range of 11.55% to 16.13%, implying a complementary contribution of iron to the mineralization system, possibly through the gradual release of Fe during hydrothermal alteration of mafic minerals present in the gabbro. Furthermore, the CaO content in the gabbro, with values up to 7.78%, reinforces its interaction with carbonates in replacement environments. Massive magnetite mineralization is not an isolated event but is influenced by iron contributions from both the Mitu volcanics and the Winchos gabbro, where Fe₂O₃ from these units was mobilized and incorporated into areas of interaction with carbonates, such as the marbles of the Chambará formation. The geological configuration suggests that the replacement of magnetite in the marble is a process linked to a Fe-enriched hydrothermal system, with diverse sources enriching the host rock and facilitating the formation of magnetite deposits.

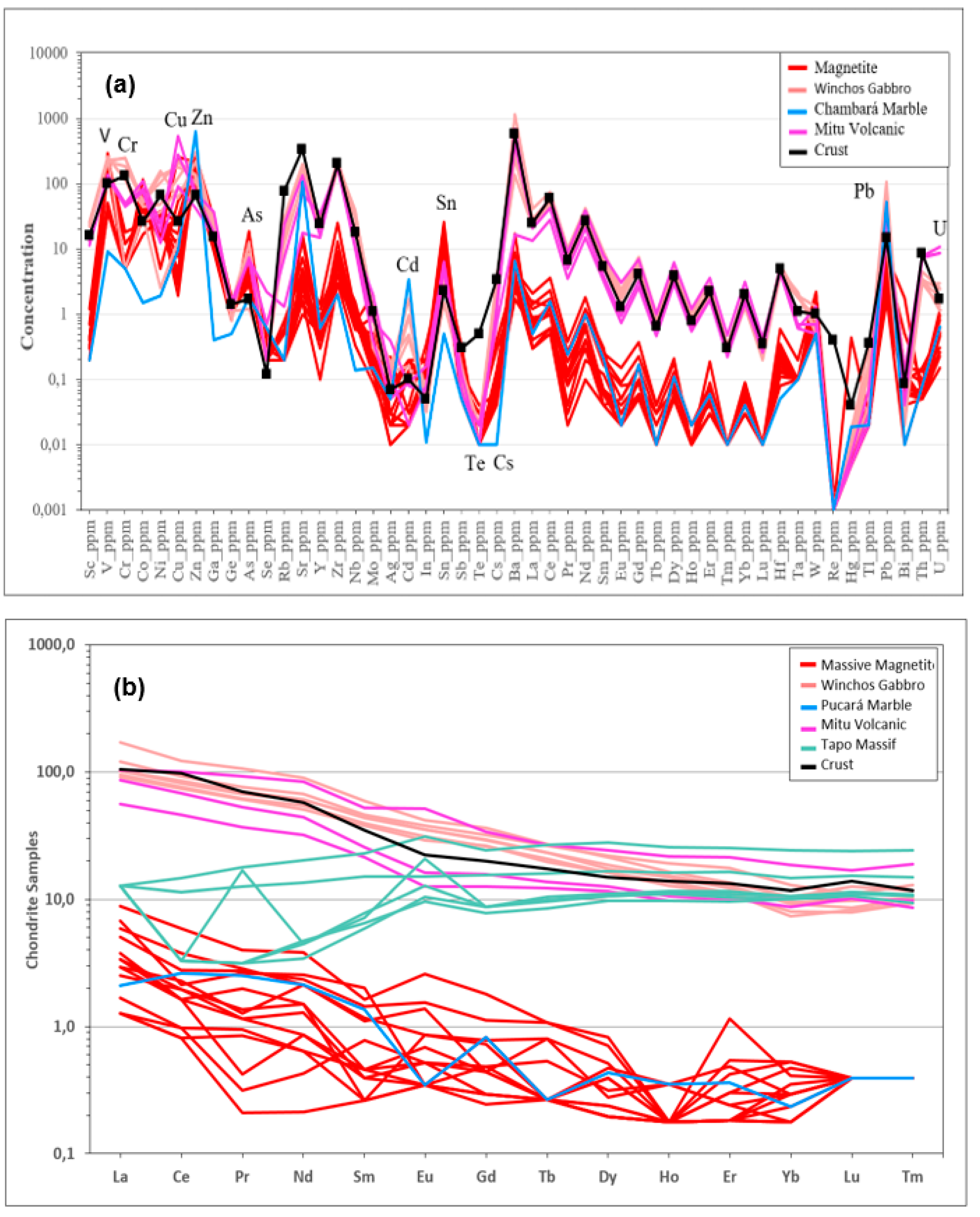

The rare earth element (REE) profile normalized to chondrite for the volcanic rocks of the Mitu Group and the ultramafic rocks of the Tapo Massif shows a similar concentration in heavy rare earth elements (HREE) (

Figure 8). At the same time, there is an increase in light rare earth elements (LREE) in the volcanic rocks of the Mitu Group compared to the ultramafic rocks of the Tapo Massif. This REE geochemical behavior can be explained by considering that the fissure magmatism of the Mitu Group intruded and assimilated the ultramafic rocks of the Tapo Massif at depth. The increase in LREE can be explained by the fact that these elements behave as highly incompatible in the magma due to their large atomic radius, which prevents them from fitting into the mineral structure, leading to their enrichment during the fissure magmatism of the Mitu Group. On the other hand, the HREE have sufficiently small radii that allow them to fit into the mineral structure. The REE profile of the Winchos gabbro and the Mitu Group rocks exhibits a similar geochemical behavior for HREE and LREE. This behavior could indicate a comagmatic event, where the fissure emission centers correspond to the emplacement of the Winchos gabbro and laterally to the volcanic rocks of the Mitu Group. The REE profile of the marble from the Chambará Formation and the massive magnetite shows similar geochemical behavior for both HREE and LREE. This behavior could be explained by the massive magnetite inheriting its REE geochemical behavior from the marble of the Chambará Formation during the replacement process.

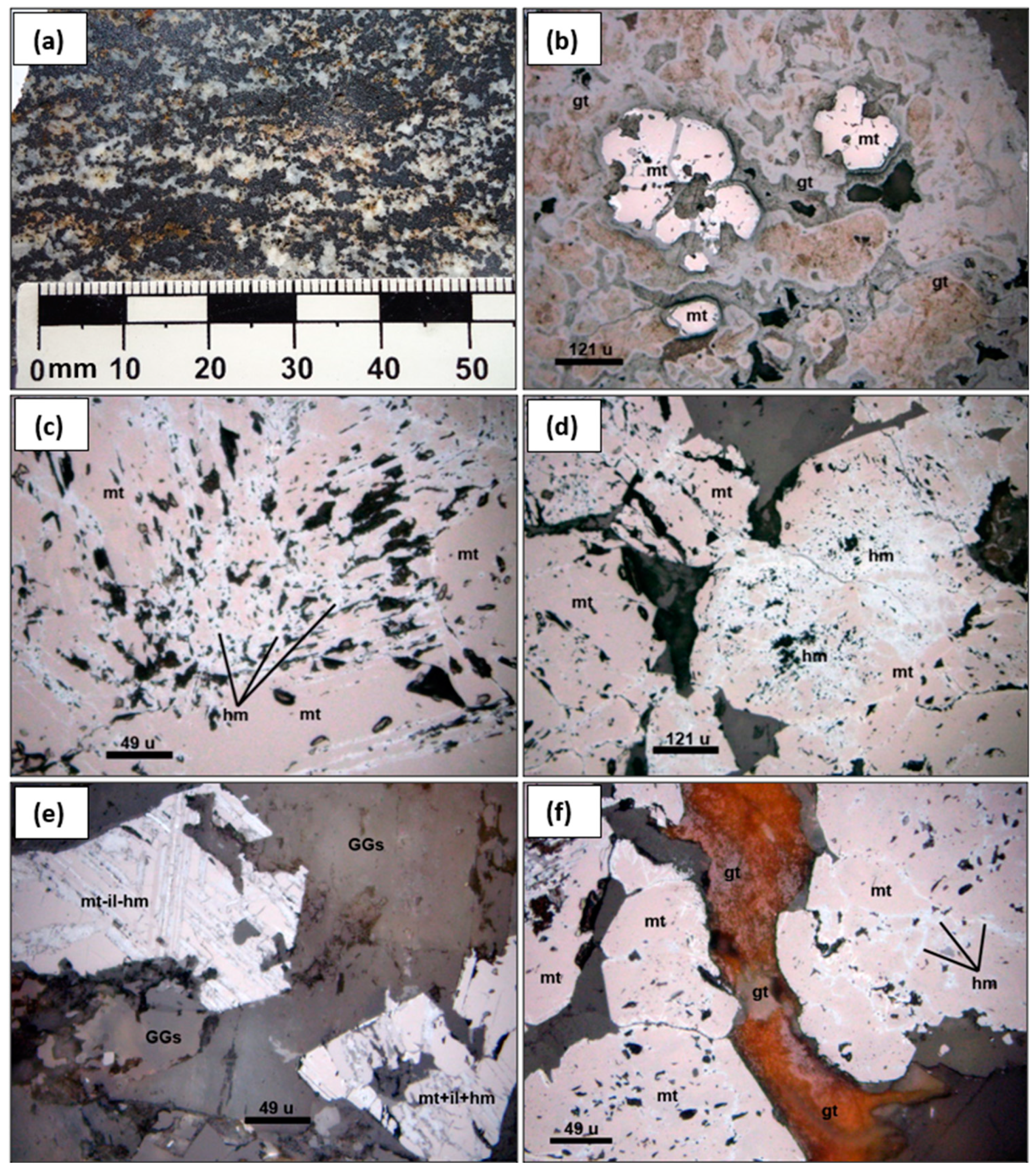

Having an understanding of major elements, trace elements, rare earth elements, and microscopic petrography allows for defining the evolution and mineralization of the magnetite in the Winchospunta-Carhuamayo prospect. Regarding the evolution of massive magnetite, there is evidence of the similarity in the REE profile with the marble of the Chambará Formation, which indicates the replacement of magnetite in the Chambará Formation marble. This is corroborated by microphotographs. Additionally, the concentration of major ferric oxide elements in the Mitu volcanic rocks and Winchos gabbro shows the availability of ferric oxide for the formation of massive magnetite. (

Figure 9).