Submitted:

05 December 2024

Posted:

06 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

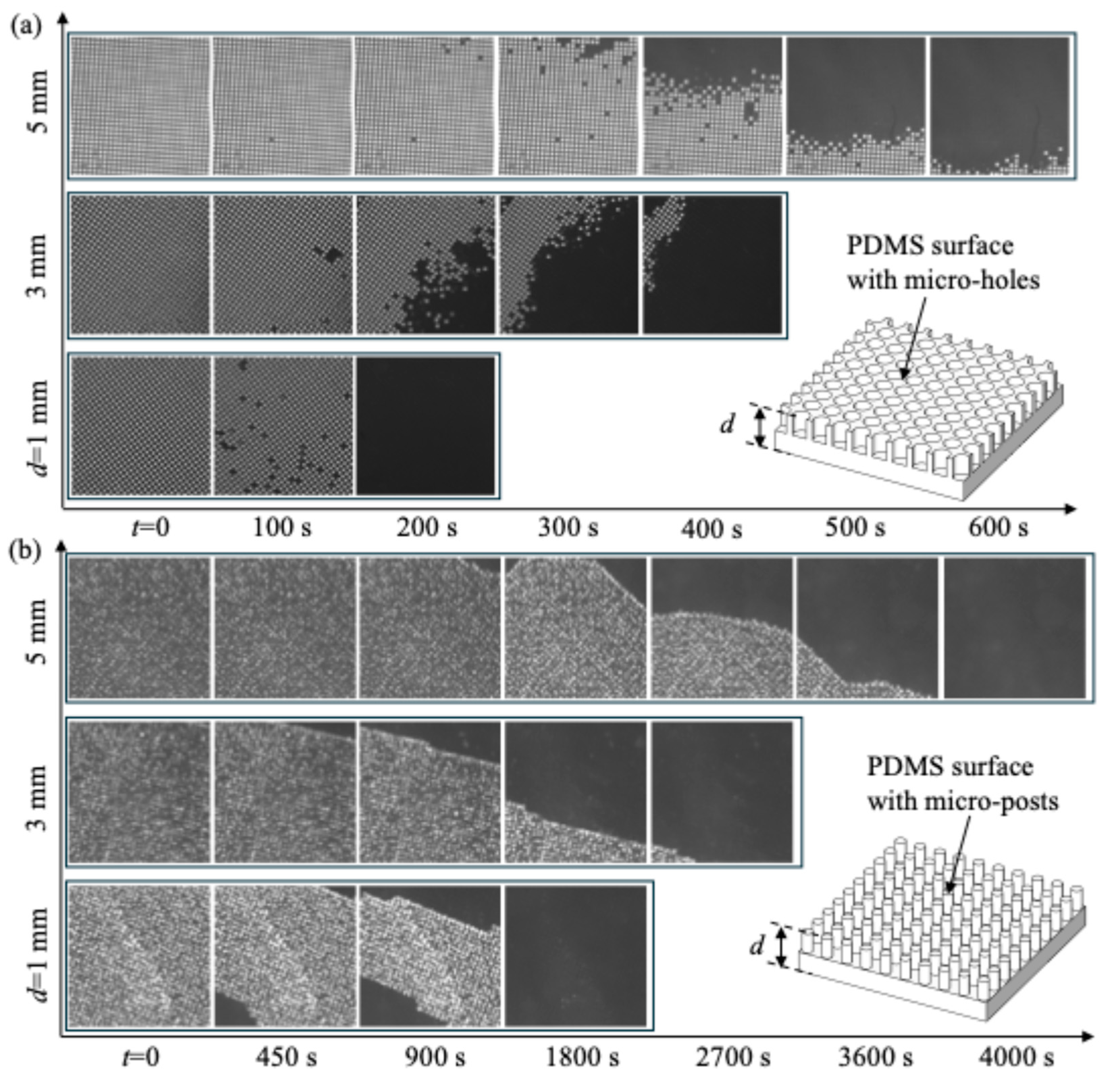

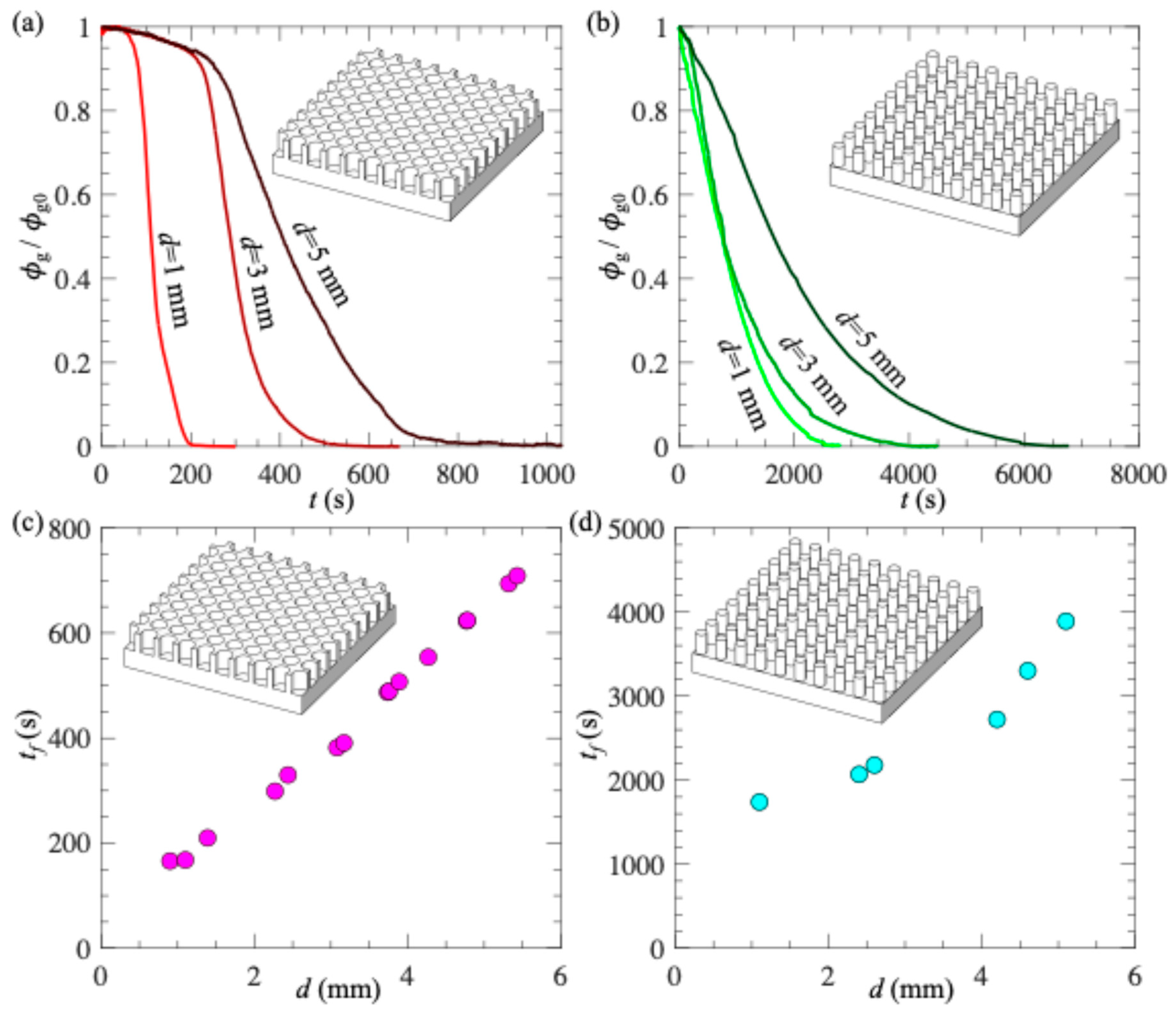

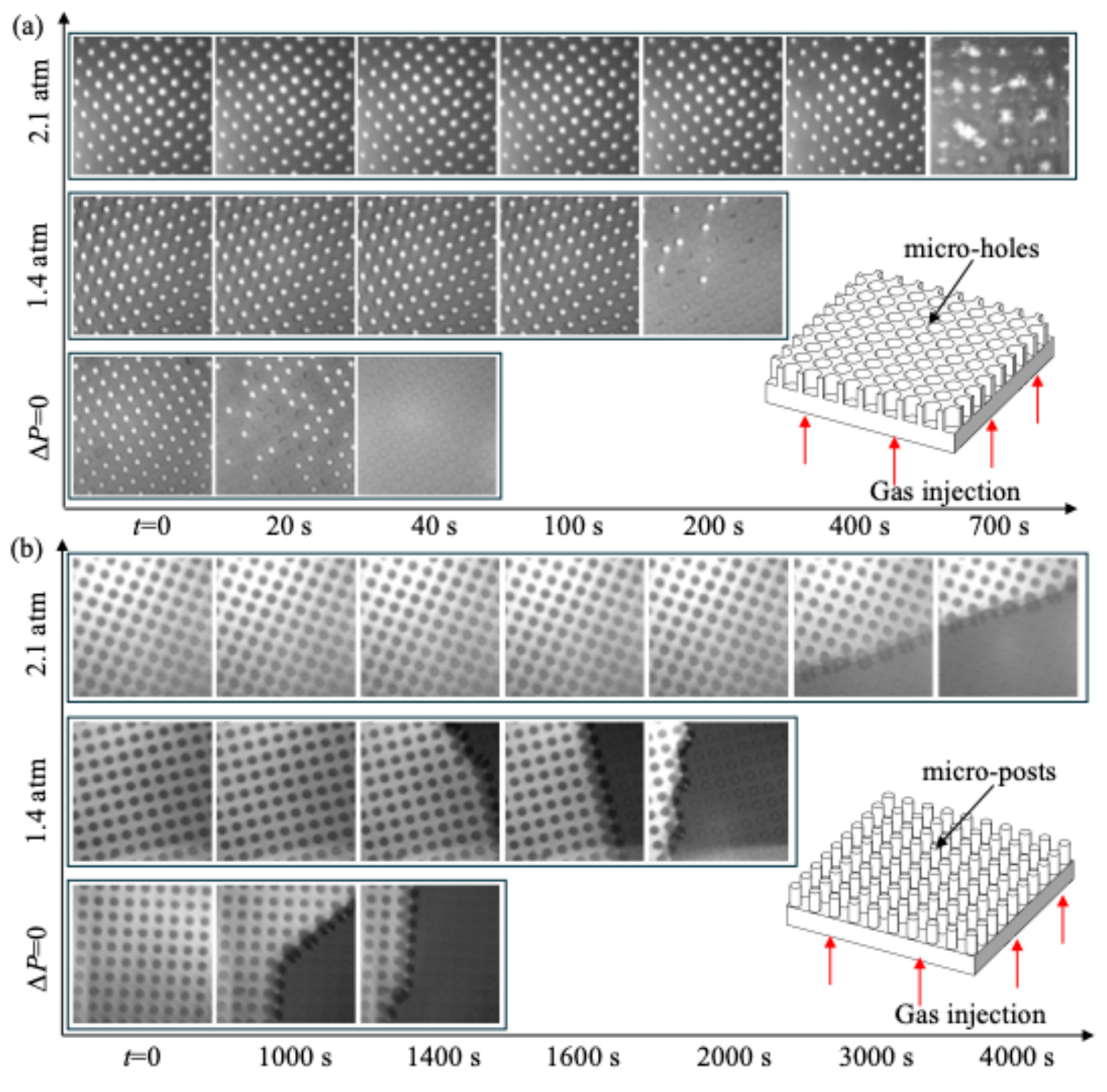

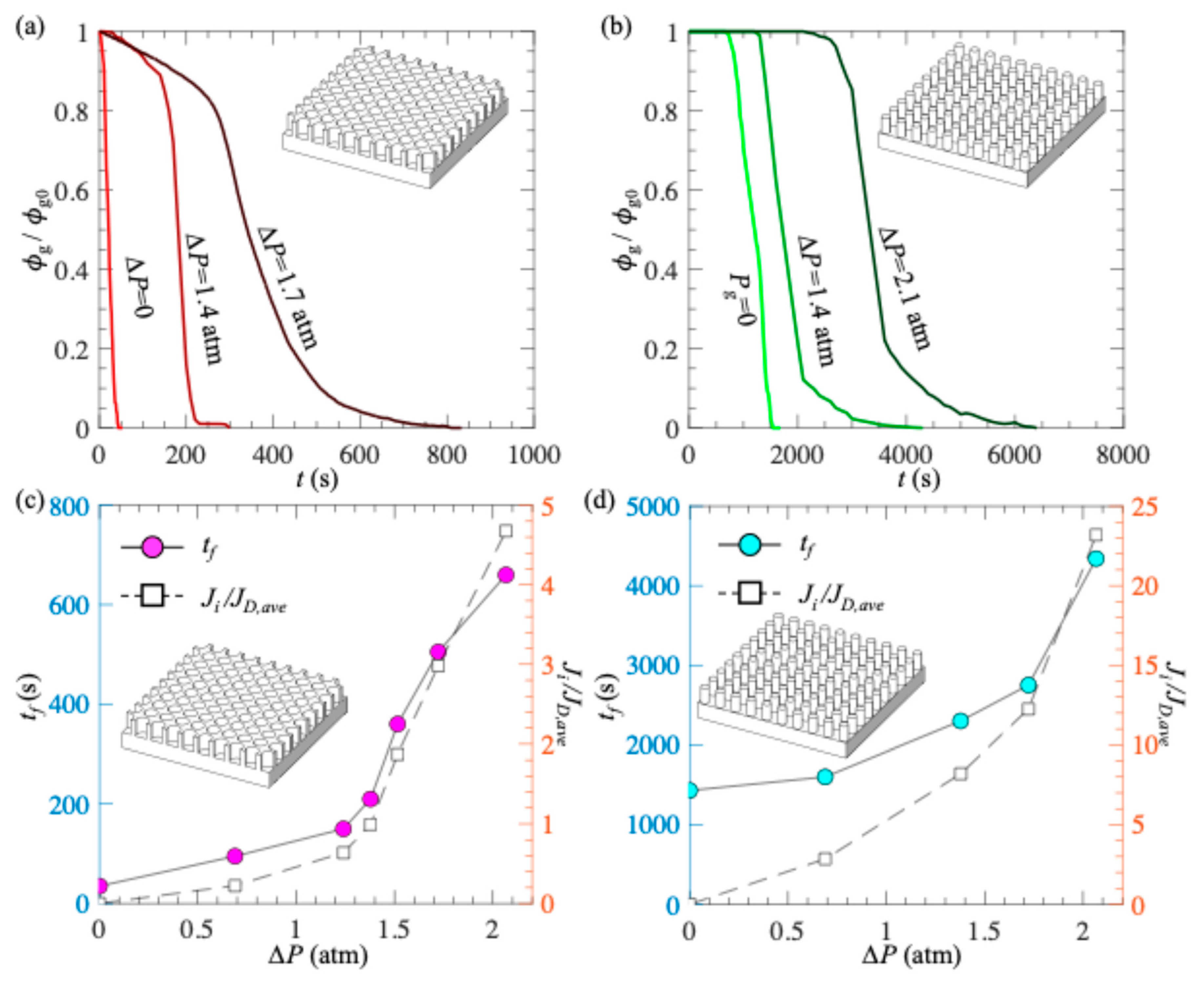

- (a)

- Effect of PDMS surface thickness on plastron longevity

- (b)

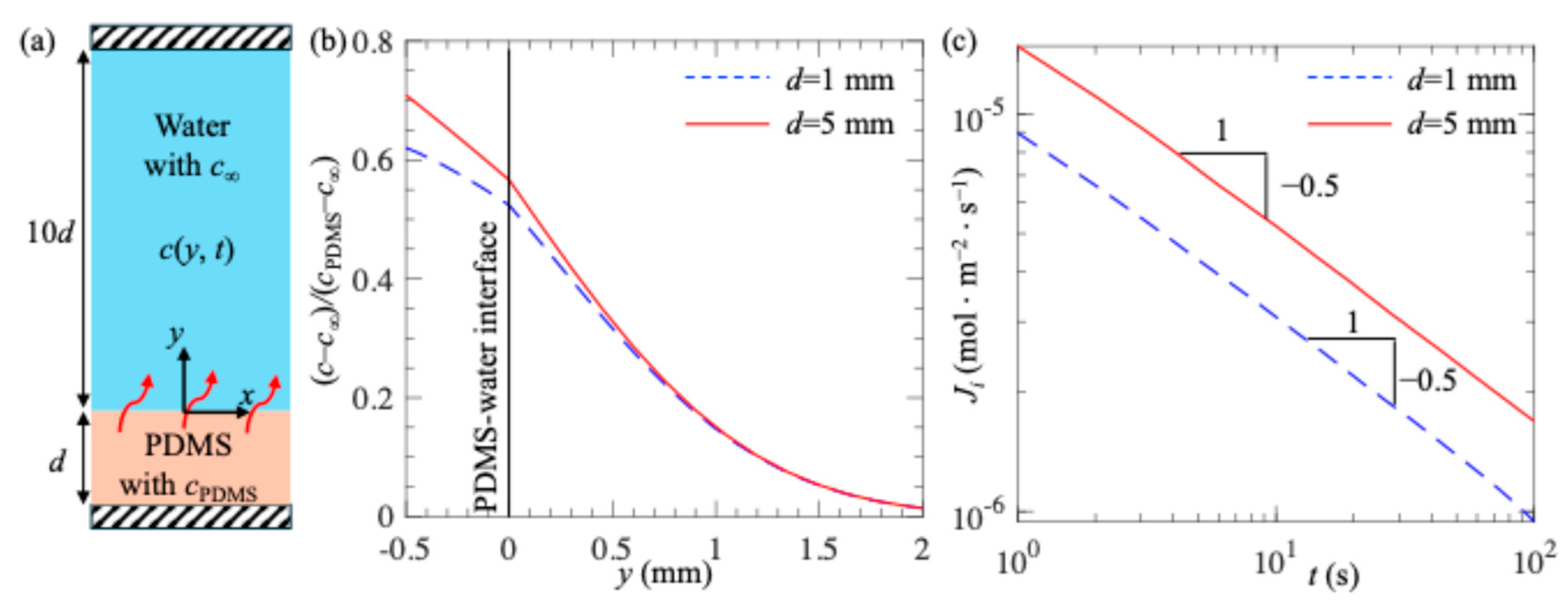

- Effect of gas injection through PDMS on plastron longevity

4. Conclusions

Data Availability Statements

Conflicts of Interest statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Hu, J.; Yao, Z. Drag reduction of turbulent boundary layer over sawtooth riblet surface with superhydrophobic coat. Physics of Fluids 2023, 35, 015104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Wu, S.; Gulfam, R.; Deng, Z.; Chen, Y. Dropwise condensation heat transfer on vertical superhydrophobic surfaces with fractal microgrooves in steam. Int J Heat Mass Transf 2023, 217, 124641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elius, M.; Richard, S.; Boyle, K.; Chang, W.S.; Moisander, P.H.; Ling, H. Impact of gas bubbles on bacterial adhesion on super-hydrophobic aluminum surfaces. Results in Surfaces and Interfaces 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, U.; Gusain, D.; Balasubramani, B.; Srivastava, S.; Ganesh, S.; Ambattu Raghavannambiar, S.; Ramaraj, K. A comprehensive review of environment-friendly biomimetic bionic superhydrophobic surfaces. Biofouling 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, F.; Hu, Z.; Feng, Y.; Lai, N.-C.; Wu, X.; Wang, R. Advanced Anti-Icing Strategies and Technologies by Macrostructured Photothermal Storage Superhydrophobic Surfaces. Advanced Materials 2024, 36, 2402897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Xie, Z.-H.; Ding, L.; Zhang, S. Progress in superhydrophobic surfaces for corrosion protection of Mg alloys – a mini-review. Anti-Corrosion Methods and Materials 2024, 71, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Lv, P.; Lin, H.; Duan, H. Underwater Superhydrophobicity: Stability, Design and Regulation, and Applications. Appl Mech Rev 2016, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassie, A.B.D.; Baxter, S. Wettability of porous surfaces. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1944, 40, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu M, Yu N, Kim J, Kim C-J “CJ”. Superhydrophobic drag reduction in high-speed towing tank. J Fluid Mech 2021, 908, A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajdi Hokmabad, B.; Ghaemi, S. Turbulent flow over wetted and non-wetted superhydrophobic counterparts with random structure. Physics of Fluids 2016, 28, 015112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, J.P. Slip on Superhydrophobic Surfaces. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 2010, 42, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.; Srinivasan, S.; Golovin, K.; McKinley, G.H.; Tuteja, A.; Katz, J. High-resolution velocity measurement in the inner part of turbulent boundary layers over super-hydrophobic surfaces. J Fluid Mech 2016, 801, 670–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, G.B.; Page, K.; Patir, A.; Nair, S.P.; Allan, E.; Parkin, I.P. The Anti-Biofouling Properties of Superhydrophobic Surfaces are Short-Lived. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 6050–6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosrati, A.; Mohammadshahi, S.; Raessi, M.; Ling, H. Impact of the Undersaturation Level on the Longevity of Superhydrophobic Surfaces in Stationary Liquids. Langmuir 2023, 39, 18124–18131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgoun, A.; Ling, H. A General Model for the Longevity of Super-Hydrophobic Surfaces in Under-Saturated, Stationary Liquid. J Heat Transfer 2022, 144, 042101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, H. Diffusion characteristics of air pockets on hydrophobic surfaces in channel flow: Three-dimensional measurement of air-water interface. Phys Rev Fluids 2019, 4, 074001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobji, M.S.; Kumar, S.V.; Asthana, A.; Govardhan, R.N. Underwater Sustainability of the “Cassie” State of Wetting. Langmuir 2009, 25, 12120–12126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.; Xue, Y.; Shi, Y.; Lin, H.; Duan, H. Metastable States and Wetting Transition of Submerged Superhydrophobic Structures. Phys Rev Lett 2014, 112, 196101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.D.; Kadoko, J.; Hodes, M. Two-Dimensional Numerical Analysis of Gas Diffusion-Induced Cassie to Wenzel State Transition. J Heat Transfer 2021, 143, 103001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, S.; Ahmad, Z.; Das, R.; Mishra, H. Counterintuitive Wetting Transitions in Doubly Reentrant Cavities as a Function of Surface Make-Up, Hydrostatic Pressure, and Cavity Aspect Ratio. Adv Mater Interfaces 2020, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemeda, A.A.; Tafreshi, H.V. General formulations for predicting longevity of submerged superhydrophobic surfaces composed of pores or posts. Langmuir 2014, 30, 10317–10327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, B.; Li, Y.; Tan, H.; Zandvliet, H.J.W.; Zhang, X.; Lohse, D. Entrapment and Dissolution of Microbubbles Inside Microwells. Langmuir 2018, 34, 10659–10667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadoko, J.; Karamanis, G.; Kirk, T.; Hodes, M. One-Dimensional Analysis of Gas Diffusion-Induced Cassie to Wenzel State Transition. J Heat Transfer 2017, 139, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, B.; Hemeda, A.A.; Amrei, M.M.; Luzar, A.; Gad-el-Hak, M.; Vahedi Tafreshi, H. Predicting longevity of submerged superhydrophobic surfaces with parallel grooves. Physics of Fluids 2013, 25, 062108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaha, M.A.; Tafreshi, H.V.; Gad-el-Hak, M. Influence of Flow on Longevity of Superhydrophobic Coatings. Langmuir 2012, 28, 9759–9766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Sun, G.; Kim, C.-J. Infinite Lifetime of Underwater Superhydrophobic States. Phys Rev Lett 2014, 113, 136103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poetes, R.; Holtzmann, K.; Franze, K.; Steiner, U. Metastable Underwater Superhydrophobicity. Phys Rev Lett 2010, 105, 166104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Xue, Y.; Lv, P.; Li, D.; Duan, H. Influence of fluid flow on the stability and wetting transition of submerged superhydrophobic surfaces. Soft Matter 2016, 12, 4241–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokmabad, B.V.; Ghaemi, S. Effect of Flow and Particle-Plastron Collision on the Longevity of Superhydrophobicity. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 41448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, S.; Mishra, H. Collective wetting transitions of submerged gas-entrapping microtextured surfaces. Droplet 2024, 3, e135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, RN. RESISTANCE OF SOLID SURFACES TO WETTING BY WATER. Ind Eng Chem 1936, 28, 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patankar, N.A. Transition between superhydrophobic states on rough surfaces. Langmuir 2004, 20, 7097–7102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadshahi, S.; O’Coin, D.; Ling, H. Impact of sandpaper grit size on drag reduction and plastron stability of super-hydrophobic surface in turbulent flows. Physics of Fluids 2024, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu N, Li ZR, McClelland A, del Campo Melchor FJ, Lee SY, Lee JH, Kim C-J “CJ”. Sustainability of the plastron on nano-grass-covered micro-trench superhydrophobic surfaces in high-speed flows of open water. J Fluid Mech 2023, 962, A9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reholon, D.; Ghaemi, S. Plastron morphology and drag of a superhydrophobic surface in turbulent regime. Phys Rev Fluids 2018, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; García-Mayoral, R.; Mani, A. Pressure fluctuations and interfacial robustness in turbulent flows over superhydrophobic surfaces. J Fluid Mech 2015, 783, 448–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; García-Mayoral, R.; Mani, A. Turbulent flows over superhydrophobic surfaces: Flow-induced capillary waves, and robustness of air-water interfaces. J Fluid Mech 2018, 835, 45–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu N, Kiani S, Xu M, Kim C-J “CJ”. Brightness of Microtrench Superhydrophobic Surfaces and Visual Detection of Intermediate Wetting States. Langmuir 2021, 37, 1206–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, S.; Yang, R.; Jiang, C.; Yuan, W. In Situ Observation of Dynamic Wetting Transition in Re-Entrant Microstructures. Langmuir 2017, 33, 3949–3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Kim, C.J. Underwater restoration and retention of gases on superhydrophobic surfaces for drag reduction. Phys Rev Lett 2011, 106, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, B.P.; Bartlett, P.N.; Wood, R.J.K. Active gas replenishment and sensing of the wetting state in a submerged superhydrophobic surface. Soft Matter 2017, 13, 1413–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yong, K. Combining the lotus leaf effect with artificial photosynthesis: Regeneration of underwater superhydrophobicity of hierarchical ZnO/Si surfaces by solar water splitting. NPG Asia Mater 2015, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchanathan, D.; Rajappan, A.; Varanasi, K.K.; McKinley, G.H. Plastron Regeneration on Submerged Superhydrophobic Surfaces Using In Situ Gas Generation by Chemical Reaction. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2018, 10, 33684–33692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakarelski, I.U.; Patankar, N.A.; Marston, J.O.; Chan, D.Y.C.; Thoroddsen, S.T. Stabilization of Leidenfrost vapour layer by textured superhydrophobic surfaces. Nature 2012, 489, 274–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranadhi, D.; Chen, D.; Kleingartner, J.A.; Srinivasan, S.; Cohen, R.E.; McKinley, G.H. Sustained drag reduction in a turbulent flow using a low-Temperature Leidenfrost surface. Sci Adv 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Xu, Z.; Gong, L.; Yang, S.; Zeng, H.; He, C.; Ge, D.; Yang, L. Recoverable underwater superhydrophobicity from a fully wetted state via dynamic air spreading. iScience 2021, 24, 103427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Wen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Song, D.; Ouahsine, A.; Hu, H. Maintenance of air layer and drag reduction on superhydrophobic surface. Ocean Engineering 2017, 130, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Choi, H.; Ha, C.; Lee, C.; Park, H. Plastron replenishment on superhydrophobic surfaces using bubble injection. Physics of Fluids 2022, 34, 103323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Huang, S.; Lv, P.; Xue, Y.; Su, Q.; Duan, H. Ultimate Stable Underwater Superhydrophobic State. Phys Rev Lett 2017, 119, 134501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilip, D.; Jha, N.K.; Govardhan, R.N.; Bobji, M.S. Controlling air solubility to maintain “Cassie” state for sustained drag reduction. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2014, 459, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.; Katz, J.; Fu, M.; Hultmark, M. Effect of Reynolds number and saturation level on gas diffusion in and out of a superhydrophobic surface. Phys Rev Fluids 2017, 2, 124005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Marlena, J.; Pranantyo, D.; Nguyen, B.L.; Yap, C.H. A porous superhydrophobic surface with active air plastron control for drag reduction and fluid impalement resistance. J Mater Chem A Mater 2019, 7, 16387–16396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, W.; Heo, S.; Lee, S.J. Effects of surface air injection on the air stability of superhydrophobic surface under partial replenishment of plastron. Physics of Fluids 2022, 34, 122115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Fang, H.; Sun, S.; Wang, X.; Cao, L.; Wu, D. Fabrication of air-permeable superhydrophobic surfaces with excellent non-wetting property. Mater Lett 2022, 313, 131783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Song, Y.; Gao, F.; Dong, S.; Xu, C.; Liu, B.; Zheng, J.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Q. Achieving underwater stable drag reduction on superhydrophobic porous steel via active injection of small amounts of air. Ocean Engineering 2024, 308, 118329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Perlin, M. Drag reduction in turbulent channel flow by gas perfusion through porous non-hydrophobic and hydrophobic interfaces: Part II. Ocean Engineering 2024, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breveleri, J.; Mohammadshahi, S.; Dunigan, T.; Ling, H. Plastron restoration for underwater superhydrophobic surface by porous material and gas injection. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2023, 676, 132319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Givenchy ET, Amigoni S, Martin C, Andrada G, Caillier L, Géribaldi S, Guittard F. Fabrication of Superhydrophobic PDMS Surfaces by Combining Acidic Treatment and Perfluorinated Monolayers. Langmuir 2009, 25, 6448–6453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tserepi, A.D.; Vlachopoulou, M.-E.; Gogolides, E. Nanotexturing of poly(dimethylsiloxane) in plasmas for creating robust super-hydrophobic surfaces. Nanotechnology 2006, 17, 3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropmann, A.; Tanguy, L.; Koltay, P.; Zengerle, R.; Riegger, L. Completely Superhydrophobic PDMS Surfaces for Microfluidics. Langmuir 2012, 28, 8292–8295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, B.; D’Amone, S.; Manca, M.; Viola, I.; Cingolani, R.; Gigli, G. Superhydrophobicity Due to the Hierarchical Scale Roughness of PDMS Surfaces. Langmuir 2008, 24, 2712–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebert, D.; Bhushan, B. Transparent, superhydrophobic, and wear-resistant surfaces using deep reactive ion etching on PDMS substrates. J Colloid Interface Sci 2016, 481, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, M.; Feng, X.; Xi, J.; Zhai, J.; Cho, K.; Feng, L.; Jiang, L. Super-Hydrophobic PDMS Surface with Ultra-Low Adhesive Force. Macromol Rapid Commun 2005, 26, 1805–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.; Yang, Q.; Chen, F.; Zhang, D.; Du, G.; Bian, H.; Si, J.; Yun, F.; Hou, X. Superhydrophobic PDMS surfaces with three-dimensional (3D) pattern-dependent controllable adhesion. Appl Surf Sci 2014, 288, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yan, W.; Zheng, H.; Zhao, C.; Liu, D. Laser-Engineered Superhydrophobic Polydimethylsiloxane for Highly Efficient Water Manipulation. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2021, 13, 48163–48170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, M.M.; Ducker, R.E.; MacDonald, J.C.; Lambert, C.R.; Grant McGimpsey, W. Super-hydrophobic, highly adhesive, polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) surfaces. J Colloid Interface Sci 2012, 367, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Wang, W.; Jiang, G.; Mei, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, K.; Cui, J. Study on hierarchical structured PDMS for surface super-hydrophobicity using imprinting with ultrafast laser structured models. Appl Surf Sci 2016, 364, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, I.; Souza, A.; Sousa, P.; Ribeiro, J.; Castanheira, E.M.S.; Lima, R.; Minas, G. Properties and Applications of PDMS for Biomedical Engineering: A Review. J Funct Biomater 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkel, T.C.; Bondar, V.I.; Nagai, K.; Freeman, B.D.; Pinnau, I. Gas sorption, diffusion, and permeation in poly(dimethylsiloxane). J Polym Sci B Polym Phys 2000, 38, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markov, D.A.; Lillie, E.M.; Garbett, S.P.; McCawley, L.J. Variation in diffusion of gases through PDMS due to plasma surface treatment and storage conditions. Biomed Microdevices 2014, 16, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberti A, Marasso SL, Cocuzza M. PDMS membranes with tunable gas permeability for microfluidic applications. RSC Adv 2014, 4, 61415–61419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Lee, H.; Jetta, D.; Oh, K.W. Vacuum-driven power-free microfluidics utilizing the gas solubility or permeability of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS). Lab Chip 2015, 15, 3962–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadshahi, S.; Breveleri, J.; Ling, H. Fabrication and characterization of super-hydrophobic surfaces based on sandpapers and nano-particle coatings. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2023, 666, 131358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, D.; Kim, J.; Ko, H.S.; Park, H.C. Direct measurement of slip flows in superhydrophobic microchannels with transverse grooves. Physics of Fluids 2008, 20, 113601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

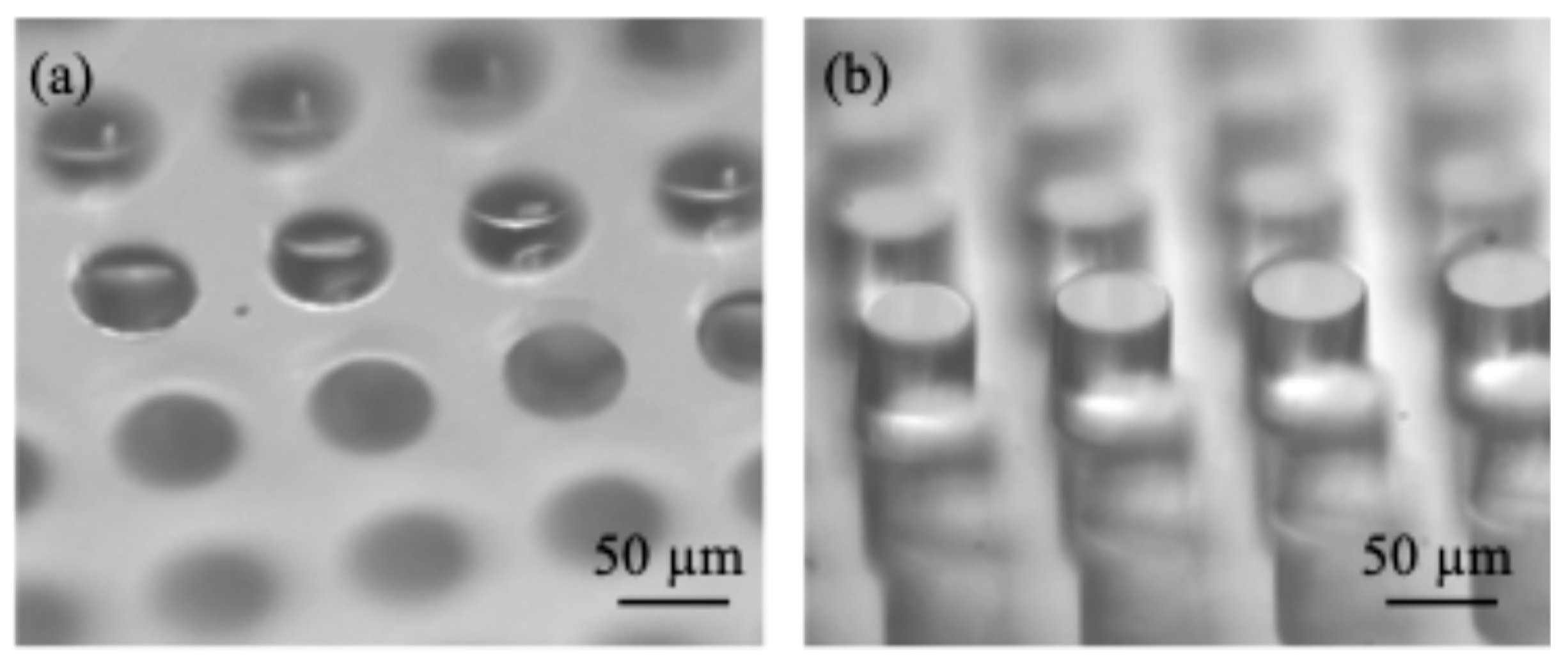

| Samples | Radius (µm) | Depth or height (µm) | Wavelength (µm) | ΔE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micro-holes | 30 | 46 | 100 | 0.015 |

| Micro-posts | 30 | 61 | 100 | −0.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).