1. Introduction

Jean Marie Flourens in the early part of the 19th century first identified the role of the semicircular canals in maintaining balance followed by the discovery and refinement of the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) generated by these canals and effected through the brain and the oculomotor system by Goltz, Breuer, Mach and Hogyes throughout the same century1. The key function of the VOR is to stabilise gaze, a key attribute for sustenance of life and orientation of oneself in space. Crum Brown was the first to point out the push pull mechanism of reciprocal stimulation/inhibition of the lateral semicircular canal on each side and the anterior canal on the right with the posterior canal on the left and the anterior canal on the left with the posterior canal on the right2. These groundbreaking discoveries paved the way for future researchers to study the vestibulo-ocular reflex in detail spearheaded by Barany. However, it was not until 1988, that a clinical test was devised by Halmagyi and Curthoys that could assess a high frequency response of the semicircular canals by the eponymous head thrust test3.

The basic principle of the test entails a sharp, rapid acceleration and unpredictable thrust on each side of the head at about 10 degrees displacement whilst asking the subject to focus the eyes on a fixed target. The VOR ensures that the eyes move with the head in the opposite direction to maintain the gaze on the target. This is achieved in different horizontal and vertical planes in the high frequency response of the canals and is a sensitive and specific indicator of high frequency canal function4. The clinical head impulse test was subjective contingent on examiner observation and expertise and therefore, there was a need for objective quantification. Cremer in 1998 first used scleral coil to physically measure the VOR in response to a head thrust5. In 2005 when Ulmer and Chay devised a remote mounted camera to capture and quantify the eye movement6. Further refinement with scleral coil experiments that are applied close to the pupil led to the discovery of the video head impulse test (vHIT) by MacDougal7 et al in 2009 where an infrared camera is applied close to the pupil through a head band for lateral semicircular canals that was found to correlate well with the scleral coil measurements. The same team in 20138 then devised a technique for measuring paired vertical canals VOR as well.

In the normal situation, the VOR ensures that the eyes remain fixed on the target, and the ratio of the head movement to the slow phase eye movement generated by the VOR is defined as a VOR gain that approaches unity and is equal. In deficiencies of the VOR, the eyes move with the head in the same direction as the head movement. The brain recognises this error in response to the command and generates a catch-up quick movement called a saccade to bring the eyes back to the target. Since the eyes cannot move in the direction of the VOR, the VOR gain involving the slow phase of the VOR becomes far less than unity and the saccade ensure that the VOR is still maintained. The slow phase of the VOR gain and the saccade can be clearly discernible in the vHIT measurement device. The difference between the clinical and the software driven vHIT are two-fold – firstly in the former, one cannot measure the slow phase of the VOR gain and secondly in the former only an overt saccade i.e. the saccade that is generated after completion of the head movement can be seen but a covert saccade i.e. the saccade generated during the head movement cannot be seen whereas in the latter both can be seen as can a VOR gain be measured.

Since its discovery, the vHIT has seen intense research and is now established as a key investigation to quantify high frequency canal function in all canals and on both sides individually. This is a milestone in vestibular diagnostics yielding valuable information crucial for diagnosis and management. Furthermore, it has been also identified as providing valuable information for vestibular compensation by virtue of analysis of saccade morphology9. vHIT features in the Barany diagnostic criteria for bilateral vestibular hypofunction10 and in the proposed isolated otolith disorder criteria by Park et al11.

Whilst the vHIT has been studied extensively in adults, it has hardly been studied in children. Vestibular disorders in children generate a significant morbidity affecting not only balance but overall development including cognitive development in children12. The prevalence is estimated between 0.45 to 5.313. Thus, accurate diagnosis is essential that includes quantification as this leads to rewarding management outcomes. To this end, the vHIT as a diagnostic marker plays an important role.

The fundamental difference between adults and children as far as VOR is concerned is that the VOR in children is in the process of development and maturation and thus it will be incorrect to transpose adult norms in children. Standardization of vHIT norms require scrutiny and analysis because these can be quite heterogenous across different centres dealing with different paediatric population cohorts. Paediatric head impulse test requires far more practice and special paediatric training than in adults with expertise that might not be available. Only a few centres in the world assess children with vHIT. Therefore, there is a gap of knowledge about the test in the paediatric population in terms of efficacy, ease and interpretation.

This article is a systematic review article of the vHIT in children. This has not been attempted before. The aims are to study the feasibility, the ease of the test in the paediatric population and quantify aggregated norms of the different parameters of the vHIT in children as gleaned through published evidence in the normal population. The objectives are to draw meaningful inferences about the outcomes of the test by calculating a pooled average VOR gain in the normal population of children for reference for future studies. A secondary objective was a scoping review of VOR gain in vestibular pathologies in children and an estimation of pooled effect sizes in case-control studies involving cohorts of normal children and children with vestibular disorders.

2. Methods

Search Strategy:

This review is an integrative literature search of published evidence pertaining to the video head impulse test in children. It was designed based on the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA). Key words used were video head impulse test vHIT, head impulse test, children, paediatric, normative data, VOR gain, review. Repositories and databases searched included PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, Cochrane reviews, Science Direct, Embase and Ovid.

Review questions:

What are the reference values of the VOR in normal children across all semicircular canals? How to perform the vHIT test in children and the how easy or difficult is it? What is the VOR gain in vestibular pathologies in children and how does it differ from normal values?

Inclusion criteria:

All studies reporting a normative value of the vHIT in children from 6 months to 18 years. Studies reporting a pathological cohort with or without a normal population were included. Studies that reported useful information regarding the test procedure in children were included for discussion.

Exclusion criteria:

Specific pathological cohorts (for example vHIT in children with sensorineural hearing loss, cochlear implants, specific genetic disorders), abstracts, series with less than 10 subjects, review articles and case reports were excluded.

Data extraction and analysis:

First, all studies with the designated key words were obtained. The studies were then subjected to an initial screening for elimination of studies in adults by all authors. This was followed by the elimination of studies that reported vHIT in specific vestibular disorders in children as well as studies that were case reports or a case series and abstracts by all authors. The selection thereof was then analysed by 3 senior authors who are paediatric vestibular specialists and who have performed thousands of paediatric vHITs among themselves and published their own laboratory norms in a tertiary paediatric vestibular unit. Agreement or concordance with the study question was then analysed. The final list was further analysed by obtaining mean VOR gains across the canals. Since the reportage was variable especially because different age cohorts were reported and sides considered separately in some studies, an average VOR gain was considered for the right and the left sides from studies that reported the gains separately for each ear. The scientific rationale for this pooling of VOR gains across different age groups and sides lay in the observation that they were not significantly different from each other that would be clinically relevant. The VOR gain values as a function of age is consistent over a wide age range from age of 20-80 years with a slight decrease at old age14,15, however, the issue in the paediatric cohort is less well determined and this review was envisaged to provide some insights.

The studies that reported vHIT in a pathological cohort only were analysed for meaningful inferences and a metanalytic quantification was not possible as normative gain values were not given, and the number of studies were small. The case-control studies were separately analysed for metanalysis of pooled effect sizes in terms of lateral semicircular canal gains that also yielded an inference of heterogeneity in these studies. Vertical canal gains in these studies were not available in all instances thereby precluding a metanalysis of vertical canals.

One study reported the effect of peak head velocity on VOR gains that was analysed separately and not included in the metanalysis. Some studies compared the vHIT with the caloric test and the rotatory chair test to assess correlation and agreement and formulate sensitivity and specificity of the vHIT. These were not analysed separately whilst reviewing these studies as the vHIT is a fundamentally different test from either the calorics or the chair as the former assesses high frequency function of the vestibular sensory epithelia and the latter ones assess low frequency responses.

Quality analysis

The scientific quality of the publications in terms of content and answering the research question was evaluated by a senior author and cross checked by another senior author in the studies that underwent quantitative synthesis using the mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 201816(n = 19). Quantitative descriptive methods were assessed and an overall rating from poor to reasonable and good were applied.

Statistical methods:

The averaged VOR gain across the studies were analysed Social Statistics, an online statistical calculator (

https://www.socscistatistics.com/tests/). A second statistical software that is developed by Stats Direct Ltd and The University of Liverpool supported by Leap of Faith Ventures

https://www.statsdirect.co.uk/Default.aspx. was used for metanalysis of effect sizes across case control studies. For these studies that reported side specific lateral semicircular VOR gains, pooled/average standard deviations (SD) were calculated by the formula for averaging standard deviations across a same sample size by the formula √s1

2/2 + s2

2 /2 where s1 is the SD of the left lateral semicircular canal and s2 the SD of the right semicircular canal.

The PRISMA algorithm is given in

Figure 1.

3. Results

Article output:

Using the designated key words in research repositories, a total of 6140 articles pertaining to video head impulse test published in English language only were observed from 2009, the year of first publication to the present day. This was then further streamlined or fine-tuned with the words children and paediatric that narrowed down the search to 112. These articles were then screened by the study protocol and 86 studies were excluded by the study protocol. Of the remaining 26 articles17-42, 5 studies23,25,29,30,38 investigated pathological cohorts only without any data on normative values. One study41 investigated the relationship between peak head velocity and VOR gain in children. Institutional unpublished data from a published audit and a personal series was included.

The final list of studies that reported values in normal and mixed normal-pathological cohorts and assessed for quantitative synthesis therefore included 2017-22, 24, 26-28,31-37,39,40,42. Of these, 624,27,28,34,40,42 were case control studies investigating both a normal and a pathological group. Fourteen17-22,26,31-33,35-37,39 studied a normal population only.

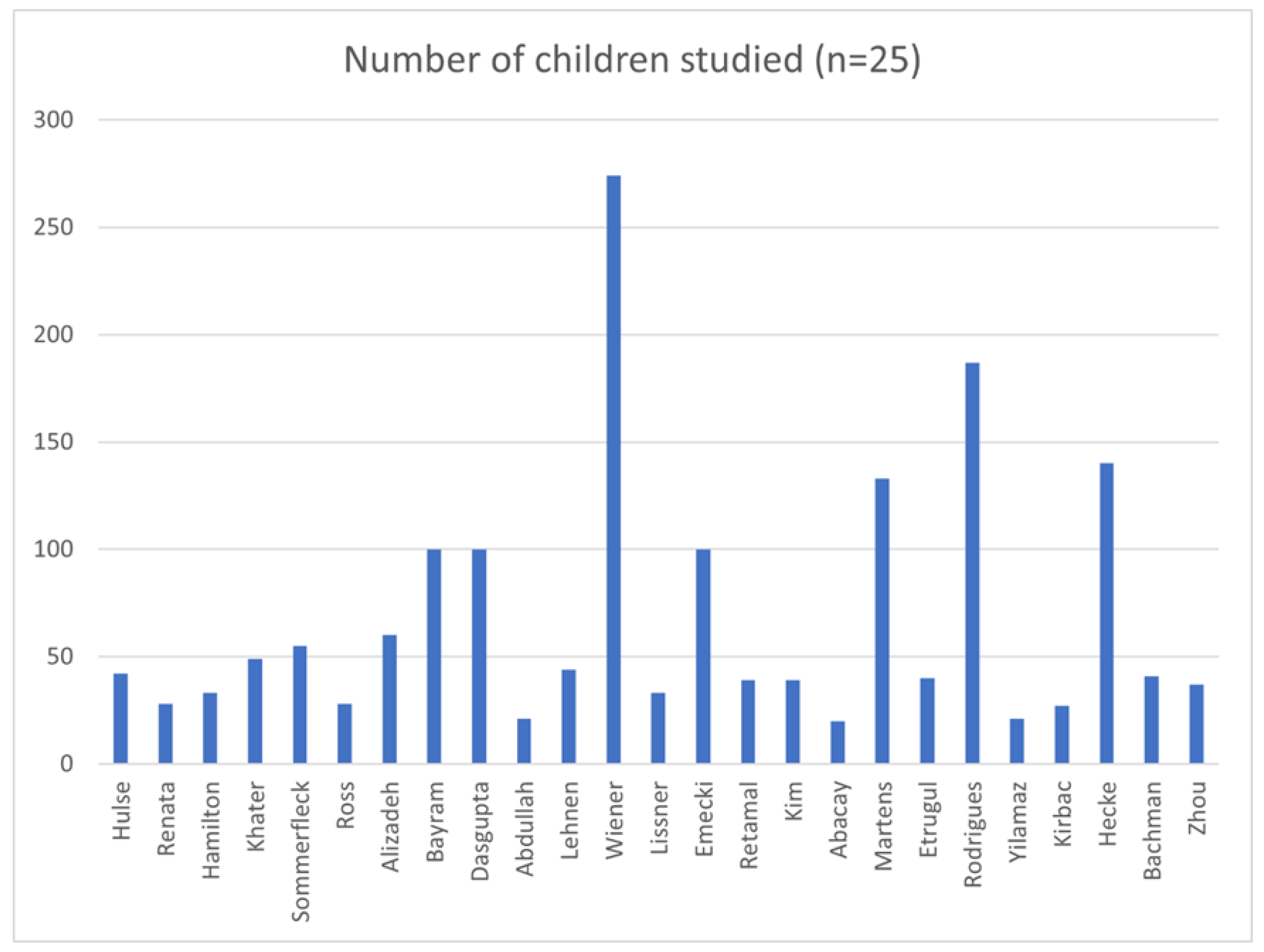

Demographics of children studied and study characteristics

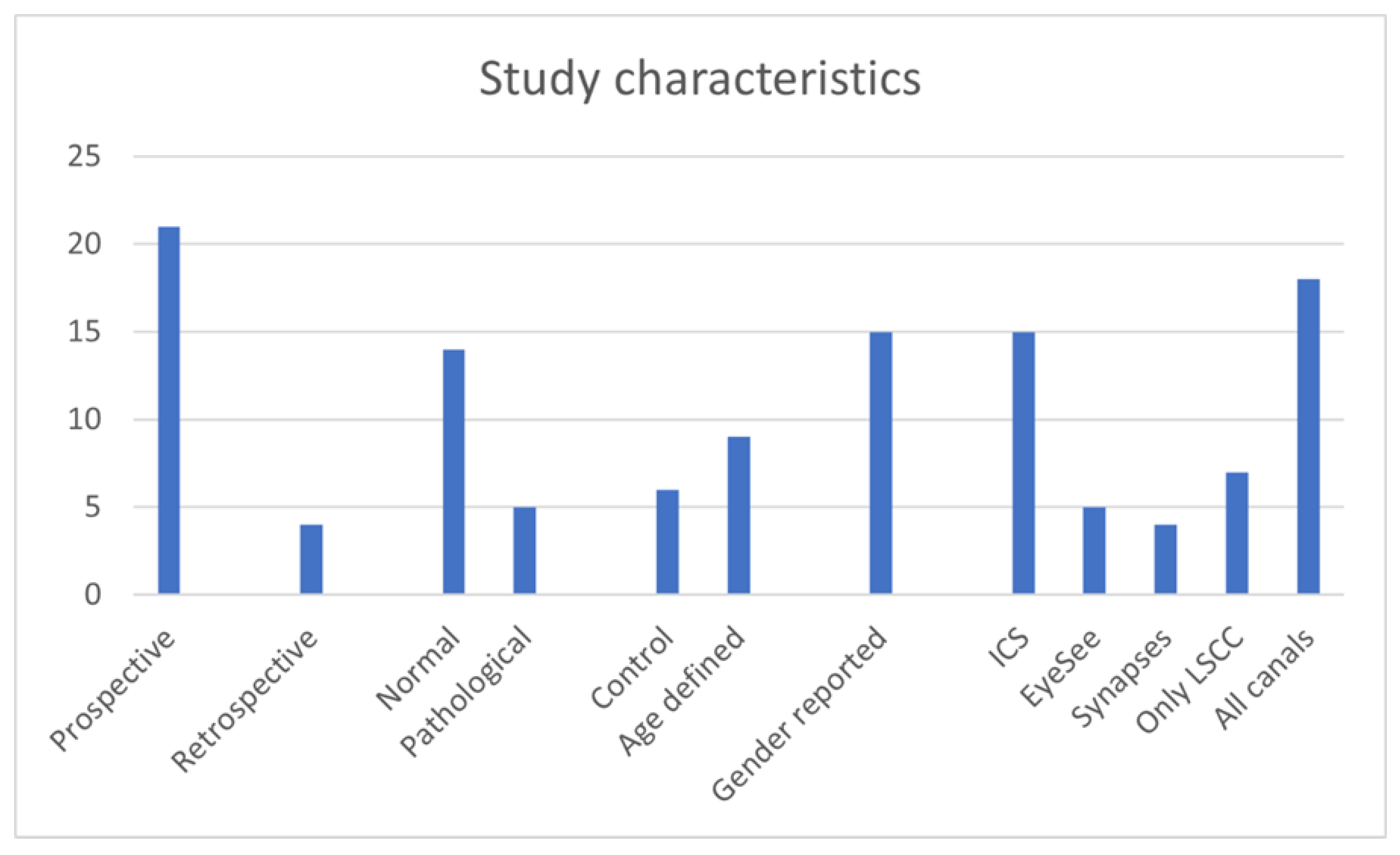

A total of 1691 children between the ages of 5 months to 18 years were studied in the 25 studies reporting vHIT results in normal and in pathological cohorts. The normal cohorts consisted of 1189 children and the rest comprised of the pathological cohorts (502). Twenty-one studies were prospective except 423,25,29,38 that were retrospective studies. Seven studies21,27,29,31,33,35,38 investigated only the lateral semicircular canals whilst the rest 14 investigated all canals. Ten studies did not report genders17,20,23,30,31,35,37,38,39,42.

Only 3 studies studied vHIT in children less than the age of 3 years23,33,39. Six studies used the EyeSeeCam system21,27,31,32,35,36. Fourteen used the ICS Impulse system17,18,20,22,24-26,28,29,30,37,38,40,42 and 4 studies used the Synapses system19,23,33,39. One did not mention the equipment34. The 3 studies that studied vHIT under the age of 3 years utilised the Synapses system. Some studies using the ICS Impulse system outlined the non-availability of a suitable size headband to fit a child under the age of 3 years, using foam pads for a good fit and the importance of tightly fitting goggles for meaningful inferences in the test18,20,22,24-26,29,35, 36,40. The studies using the EyeSeeCam system alluded to a problem of goggle slippage in a mobile camera32. Under the age of 3 years, the tests were performed with the child sitting on the carer’s knees.

Nine studies20,21,31,33,35-37,39,42 reported VOR gain across different age groups and did not observe any statistically significant differences of VOR gains across the paediatric age group from the age of 6 years. The Martens study33 observed that children under the age of 1 year showed statistically significant low VOR gains than other groups whilst the Rodrigues Villalba study36 showed that children from 3-6 years showed statistically significant lower gain values than older children. Wiener-Vacher pointed out that refractive errors under the age of 3 years contribute to this gain value39.

Technique and feasibility

Twelve studies reported the time required to perform the test in children that was observed to be quick18,20,24,26-28,30,31,37,38,39. Seven studies calculating the time reported an average time of 10-15 minutes,24,26,27,30,31,37. The technique involved unpredictable head impulses delivered on an average for at least 10 and up to 20 impulses,21,22,24-30,32,34,35.

The distance between the target and the pupils on an average were 1 m with a fixed target on the wall that were recommended to be attractive targets for example toys that would appeal to the children in almost all studies. Many studies reported on the importance of adequate instructions and tailoring the test according to the child’s needs for example avoiding blinking and adequate engagement18,24,25-27,29,32,34,35,39 and a further four studies recommended a technique whereby eye lids were recommended to be pulled up18,20,24,26.

The displacement of the head was reported by most studies as 10-20 degrees whilst executing the impulses at a peak head velocity between 50 – 250 degs/sec with an average of at least 100-150 deg/sec. Whilst high velocities were possible in lateral head impulses, as many as 5 studies23,33,36,37,39 reported that a similar high peak velocity was difficult to achieve in the vertical canals.

A couple of studies29,40 specifically mentioned operator variability that could generate heterogenous results. All studies reported on the ease of performing the test with practice and experience. The test-retest variability was minimal as reported in one study37. One study21 observed several reasons for possible test failure that included apprehension, lack of interest and failure of calibration.

Table 1 illustrates the different studies and important observations whilst

Table 2 is a representation of VOR gains and the demographics.

VOR gain across studies

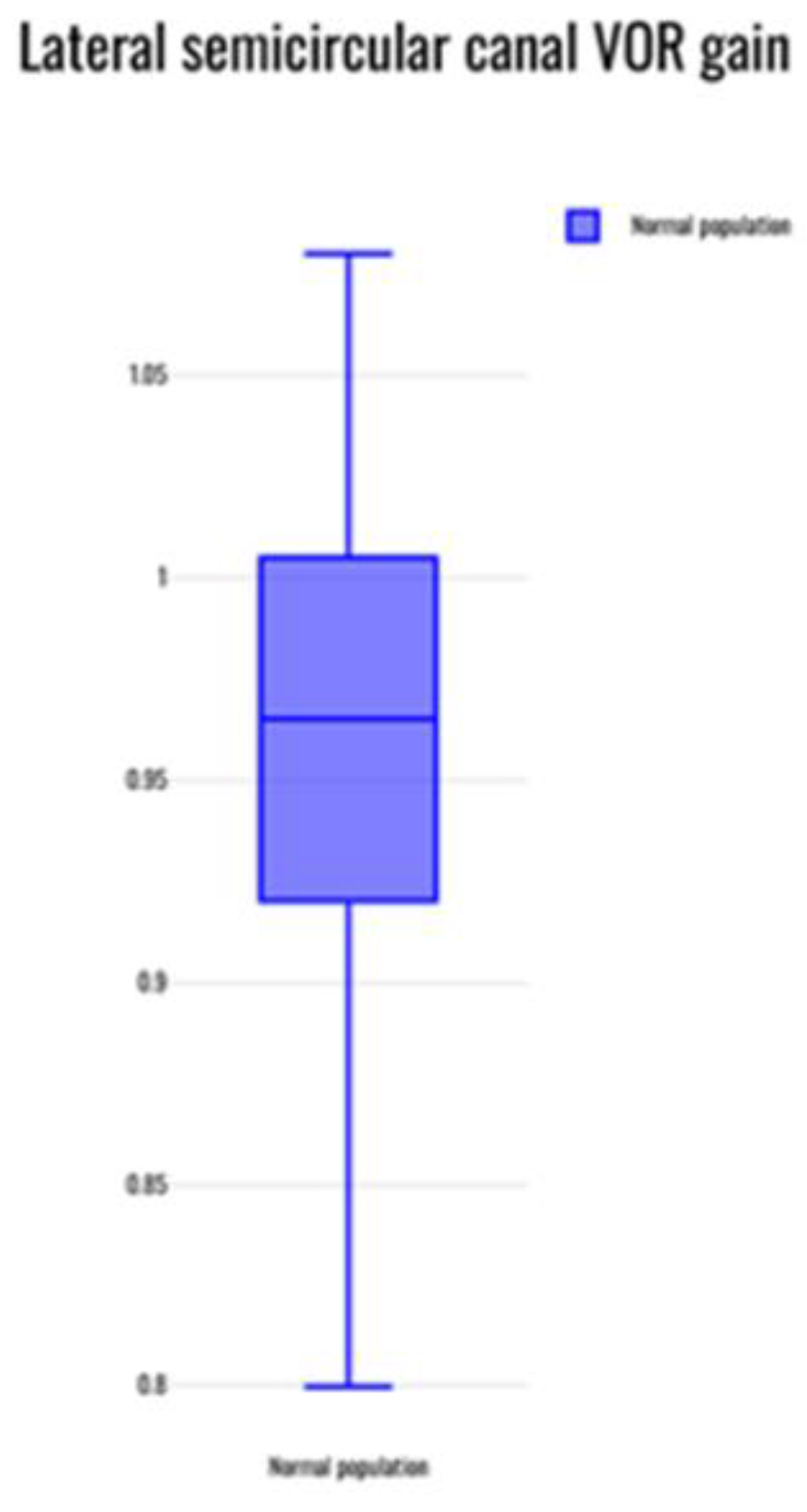

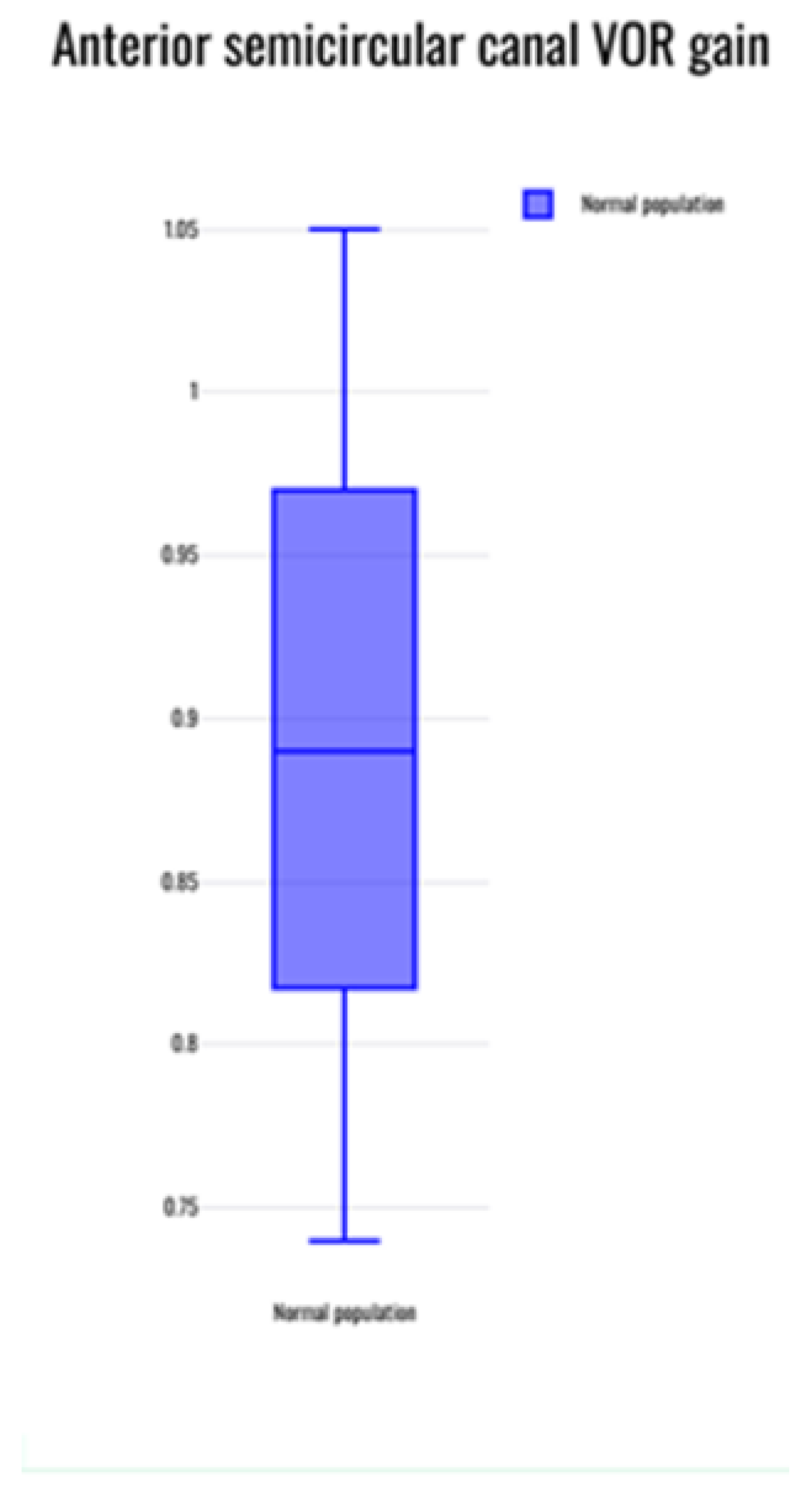

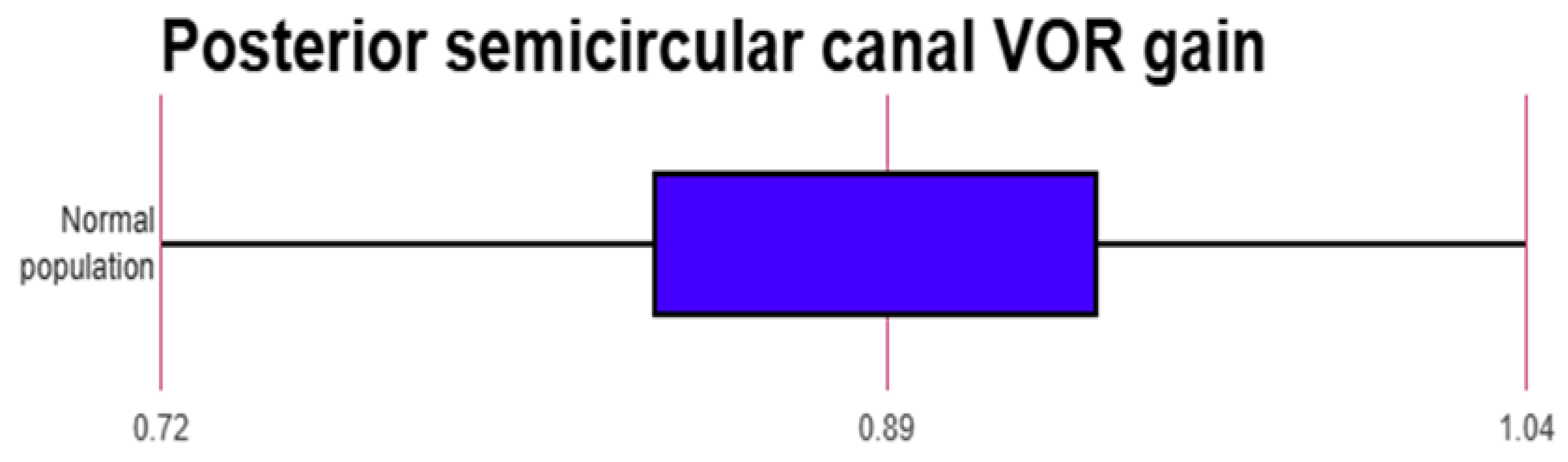

The mean normative value of the VOR gain reported across 20 studies that reported normative data in the normal population17-22,24,26-28,31-37,39,40,42 was evaluated statistically. The average VOR gain was observed to be 0.96 +/- 0.07 in the lateral canals; 0.89 +/- 0.13 in the anterior canals and 0.9 +/0.12 in the posterior canals. Whilst there was large concordance within the lateral semicircular canal gain, there was variability noted for the vertical canal groups especially the anterior semicircular canal where at least three studies reported gain values of lower than 0.824,26,42.

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 are box and whisker plots of average VOR gain in the normal population in different canals.

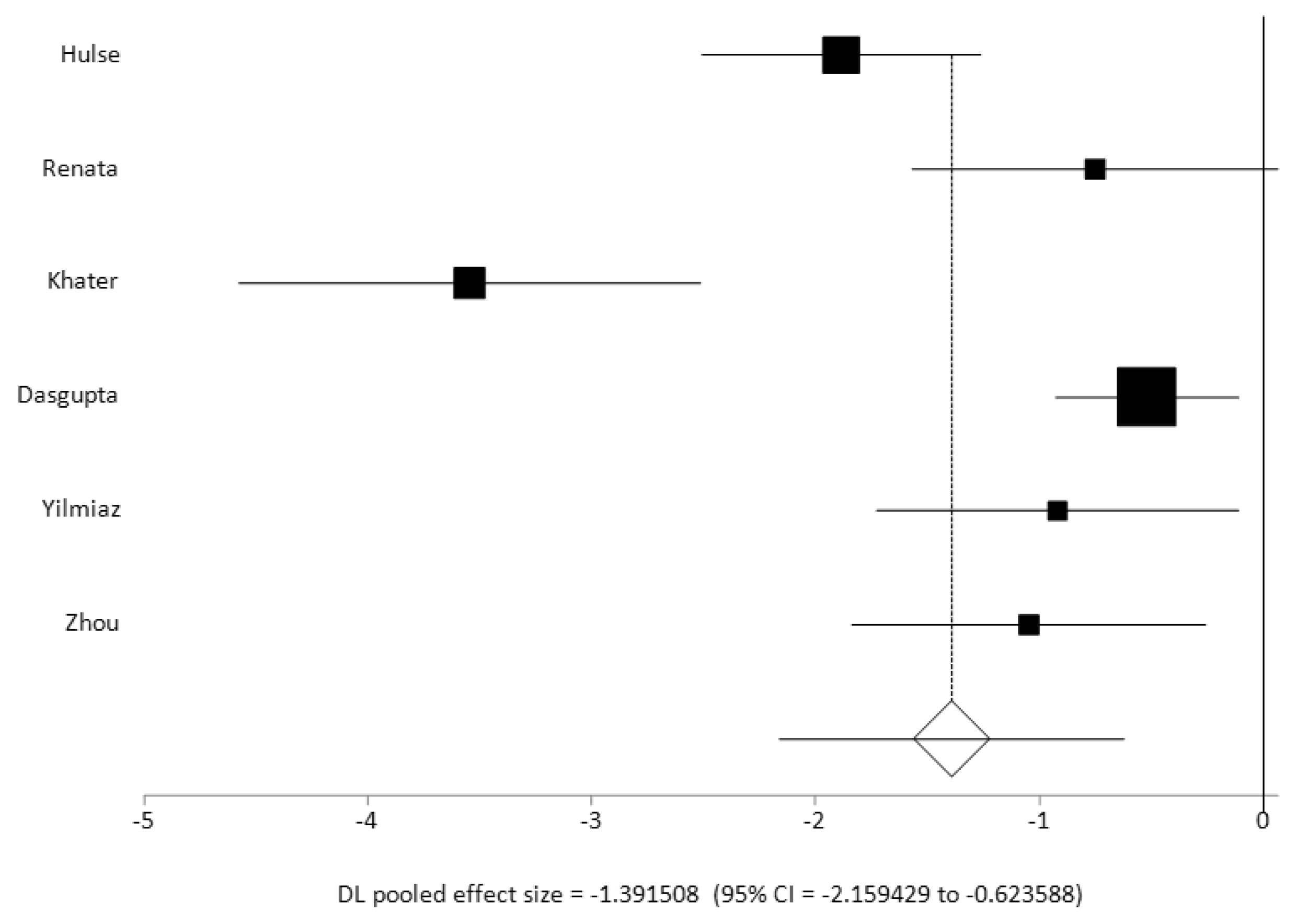

When comparing the VOR gain value across the lateral semicircular canal plane in studies which included data for both normal and pathological groups24,27,28,34,40,42 (n = 6), the combined random effects pooled effect size was significant with a large effect size of 1 and a significant heterogeneity (I2 inconsistency 86.2%). Two studies27,29 reported a VOR gain value of less than 0.5 in their pathological cohorts as compared to other studies who reported VOR gain values in their pathological cohorts between 0.6 and 0.8 (average gain across all studies 0.67 +/- 0.16). All these studies had reported statistically significant VOR gain differences between their normal and their pathological cohorts. These studies in addition to the studies that reported a pathological cohort only23,25,29,30,38 also observed that a low VOR gain with corrective saccades are the strongest indicators of vestibular weakness. VOR gain alone was not a strong indicator of vestibular weakness as commented on by two studies25,37. In fact, five studies 24,28,29,31,42 reported that refixation saccades with normal VOR gain indicated compensated vestibular weakness.

Figure 7 is a forest plot of the pooled effect sizes of controlled studies that were metanalysed.

The 5 studies that studied the vHIT only in a pathological cohort 23,25,29,30,38 reported individual gains in specific aetiologies that they had encountered. A VOR gain value of less than 0.7 – 0.8 with refixation saccades were deemed abnormal. Hamilton25 reported that saccades were 100% specific and sensitive to confirm vestibular weakness. Sommerfleck38 considered balance disorders in children as a whole and observed that about 42% presented with vestibular symptoms. Many of these children showed a diminution of VOR gain in vestibular pathology except in vestibular migraine. Kim29 pointed to several sources of artifact contamination: specifically blink artifact, difficulty with following instructions, inattention and goggle slippage. They reported a low sensitivity but a high specificity when compared to the caloric test. Etrugul23 observed saccade morphology evolution with vestibular compensation and whist calculating average gain across all canals, described a significantly low gain of less than 0.7 in vestibular pathologies. Kirbac30 observed similarly reporting significantly low gains across a pathological group.

There had been only 1 study that investigated peak head velocity with VOR gain41. This demonstrated that achieving high velocities in the vertical canals were more difficult than in the lateral canals but since the VOR gain was not different with different including slower peak head velocities that was felt as not to have contaminated the outcome. Wiener came to the same conclusion39.

Table 3 summarises the statistical analysis.

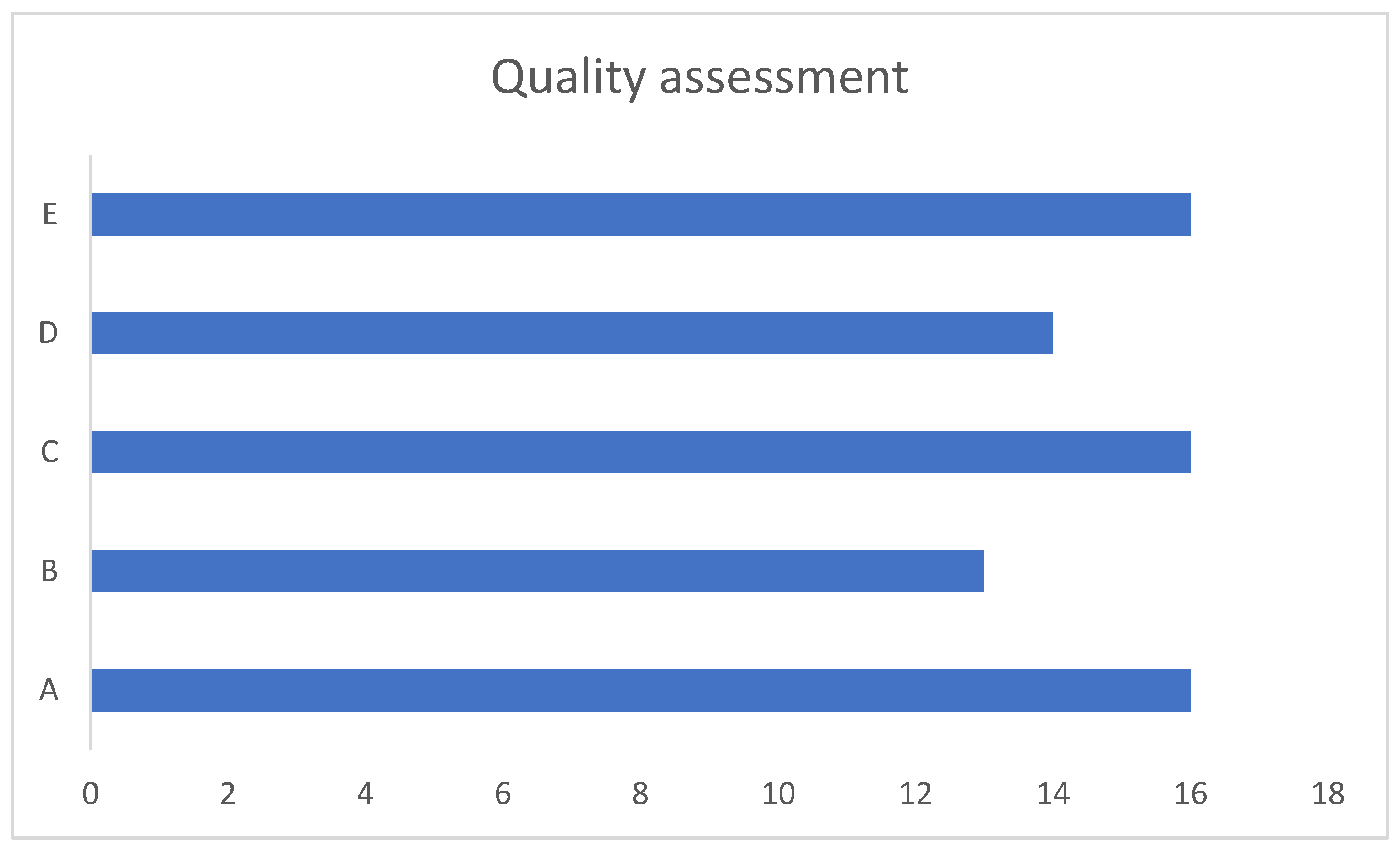

Quality analysis

Clear research questions were described in all but two studies

34,40. The sample strategy relevant to address relevant research question was deemed satisfactory in 16 and undetermined in 3

27,34,40. The samples were deemed representative of the target population in 13 studies

17,20,22,25,26,28,29,32,33,35,36,38,42. Sixteen studies were with appropriate measurements and statistical analysis

17,18,20,21,22,25,26,28,30-33,35,36,39,42. Fourteen studies were considered with low non responsive bias

17,18,20,22,25,26,28,30-33,36,39,42 . Eleven studies were deemed to be good, 5 were reasonable and 3 were poor.

Figure 8 illustrates this.

Recommendations

We provide recommendations as to the different aspects of the vHIT in children in

Table 4 as gleaned from this review.

4. Discussion

The video head impulse test has revolutionised vestibular diagnostics yielding valuable information about high frequency vestibular canal function. This frequency is the most utilised of all frequency responses in the human species and therefore the most practical one in day-to-day function. Previously the calorics and the rotatory chair yielded ear specific information for low frequency vestibular lateral canal function only. The vHIT is not only side specific but yields information on all semicircular canals.

Whilst the efficacy, significance and the feasibility of this quick non-invasive test is well established evidenced by over 6000 publications over the last 15 years, in children we could manage to list only 112 studies that had studied the test. Out of these, a vast majority had researched on the vHIT in specific pathological cohorts for example in sensorineural hearing loss or cochlear implantation children or individual disorders known to cause a hearing loss. These studies did not include normative data or a comparison of the test outcomes with other pathologies especially the ones that spare the cochlea. These studies were therefore excluded. Along with other exclusion criteria, our final list of studies who had reported normative data and cumulative pathological data comprised of 25 articles. All these studies also commented on test logistics and feasibility in the paediatric population. There is consensus yet to be achieved as to the technique of the test in children for most informed outcome and we felt that by looking into the evidence, we can arrive at one.

Our main research objective was to quantify normal VOR gains in the paediatric population. As can be noted that our review articles were quite heterogenous with different study designs and protocols and normal VOR gains were likely to differ. However, there was good consistency in reporting lateral canal VOR gains across the study groups with an average value of 0.96 +/- 0.07 ((range 0.8 - 1.08) in the lateral canals. This would translate as a VOR gain between 0.9 to 1 as a normal value for VOR gain for this canal in children across age groups similar to that in an adult. This gain value is less than 0.9 in the Martens study33 under the age of 1 year that was statistically lower than older children, but it can be noted that this lower gain value is still more than 0.7 that was apparent in pathological cohorts in this review. Thus, a gain value between 0.7 and 0.9 in children under the age of 1 year does not appear to be clinically significant unless accompanied by other stigmata and signs of vestibular disorders in children.

When the anterior semicircular canal VOR gain was pooled, it was noted that this was 0.89 +/- 0.13 with a range of 0.74 to 1.03 as the normal values. For the posterior semicircular gains, the pooled average was 0.9 +/-0.12 with a range between 0.72 to 1.04. This is lower than that found in adults that is 0.8 and above. In fact, four studies18,24,36,42 observed gains of less than 0.8 and just over 0.8 in the anterior semicircular canal and in the posterior semicircular canals. A low normal VOR in the vertical canals gain is attributed partly to the cervical neck maturation and cervical neck muscle tone in a developing child according to three studies21,24,37. The vertical canal gains showed greater variability, breadth and outliers than the lateral canal gains as can be seen in the figures.

The VOR gain in pathological cohorts with vestibular problems were reported in studies who had investigated this to be uniformly lower than the normal value (<0.7) and combined with refixation saccades, the most important indicator of vestibular weakness that is well known (5 studies with pathological cohorts and 6 studies with case and control cohorts). When we compared the case control studies for a combined effect size of VOR gain in the lateral semicircular canals, we detected a large effect size that is not unsurprising and well accepted in the adult population. We also observed significant heterogeneity in this group of studies when they were reporting VOR gain in the pathological cohort in the lateral semicircular canals. This was because the Hulse27 and the Khater28 study reported significantly lower gain of <0.5 as compared to the others ranging between 0.6-0.8 in their pathological cohorts. This can be explained by the observation that the pathologies in the cohorts in each study were different. Furthermore, since VOR gain improves with vestibular compensation especially in a highly plastic and maturing vestibular system in the paediatric population, the data captured at a given time frame will be variable as well. However, the mean VOR gain showed an average of 0.68 that is well below the normal range as described earlier.

Therefore, it can be said that a high frequency VOR as measured by the vHIT is as effective a biomarker of vestibular weakness in children as in adults not withstanding a maturing and developing vestibular system in children. The VOR is present at birth but is not mature and reaches functional maturity around 6-12 months of age 39. As it matures, it calibrates and refines according to environmental stimuli. This also underpins the very important role of the developing VOR in children from an early age. We believe that this observation suggests that derangement of the VOR in children due to any reason will affect a child’s orientation in space and balance that can be eminently detected by the vHIT and therefore this test needs to be performed to investigate balance disorders in children.

Five studies reported normal gain with refixation saccades as further indicators of compensated vestibular weakness24,28,29,31,42. This observation coupled with the observation that VOR gain alone was not the sole marker for a vestibular weakness and the high sensitivity and specificity of saccades noted in one study lead one to infer that saccades are crucial to establish vestibular weakness. In adults, studies by Perez Fernandez43 and replicated by Korsager44 had also demonstrated refixation saccades with normal VOR gain suggested compensated vestibular weakness. It must be borne in mind that vestibular compensation in a child will be different from those in adults due to evolving and highly efficient and active cerebral plasticity. Thus, VOR gain morphology and saccade evolution will be different too and likely to be more noticeable. A recent SHIMP study in children arrived at a similar conclusion45. It is likely that further qualification of saccade and other related parameters (such as, amplitude and latency) might evolve in children in the future.

The studies used 3 different equipment for the vHIT - ICS Impulse (head mounted fixed camera), EyeSeeCam (head mounted mobile camera) and Synapses (remote camera). Most studies in this review investigated children over the age of 3 years with the exception of 3 studies23,33,39. These investigators used the remote camera Synapses system. Head bands fitting small heads under the age of 3 years or slightly over are not yet manufactured or marketed although individual centres have improvised various techniques. The common technique used is to use extra foam or padding in the head band for the ICS Impulse and the EyeSeeCam systems using a head mounted camera as suggested by two authors18,20 to avoid goggle slippage. A tight and optimal fitting goggles to obtain meaningful results through the band was recommended by several studies (n=10). This is intuitively a most important consideration in children given the head circumferences and a band not fitted correctly is a recognised cause of skewed VOR gain46. A remote camera system that precludes the use of a head band mounted camera can be tried from the age of 6 months onwards33. One study32 reported goggle slippage in a mobile camera system that can interfere with VOR gain calculations.

Bayram21 pointed out several reasons that precluded successful implementation of the test. The current authors agree to this and have encountered the factors mentioned that included fear, anxiety, disinterest and calibration failure. However, even in these circumstances, these factors can be mitigated by increasing play and engagement with the children to make the test interesting especially in children with neurodevelopmental conditions and overcome apprehension. In some instances, calibration is impossible where we recommend using default calibration. This is not ideal as in all software, the default calibration is based on an adult population. Even then, vHIT should be attempted and the results interpreted in a holistic approach to aim to draw meaningful conclusions.

Pupillary calibration was deemed important across several studies (n = 7) that was recommended to be attained by lifting eyelids up and by performing the test in a bright room to avoid pupillary constriction. Technical difficulties for the test practitioner especially in very young children are possible due to difficulties in following instructions by children and their tendency to get distracted easily.

All studies emphasized the need for correct and adequate instructions whilst performing the test by explaining carefully and repeatedly encouraging the subjects and the carers alike. Attractive targets were suggested to be chosen for gaze fixation and special care were recommended to engage the children at all times to avoid flagging attention that can make the test difficult to perform. Anxiety has been known to influence VOR gains47. The time taken to implement the test ranges from 10 minutes to 20 minutes and deemed to be quick. The lesser the time taken, the more engaged the children are likely to be for a reliable test. This underpins the vital suggestion that was a common theme across all studies that experience and practice are required to perform this test successfully in children. The present authors cannot emphasize this point well enough that paediatric training is pivotal to perform the test. A study by Money-Nolan14 investigated the likely cause of noise in vHIT measurements and identified operator variability, google tightness, gaze alignment towards canal plane and inconsistent technique generating unreliable VOR gains that is also true for the paediatric population as well. They recommend adopting consistent techniques and individual laboratory norms that the present authors agree to.

In terms of technique, the review observed that a minimum of 10 impulses for all canals with about 10-20 degrees displacement at a peak head velocity of 100-200 degrees per second should elicit a meaningful and robust response of the vHIT. It is important to obtain at least 10 trials to reproduce or replicate output results as invariably some impulses will contain artifacts especially in children due to the reasons enumerated above for example blink artifacts, lack of attention and pupillary calibration. The distance of the target should be 1 m. Vergence determined by distance does not play a role according to Wiener-Vacher39. Some studies have pointed out that it is difficult to achieve sufficient head velocity for the vertical especially the anterior semicircular canals. Low peak head velocities may affect gain as observed in adults. Furthermore, in adults, low peak head velocities may not elicit the high frequency VOR as smooth pursuits contribute to gaze stability rather than the VOR14. In children, this smooth pursuit system does not develop until late, so low peak head velocities should not contaminate VOR gain in children48. Zhou41 observed that in children, peak saccadic velocities of different magnitudes did not alter VOR gain significantly. Therefore, the lower peak head velocities to assess vertical canal function still yield canal specific VOR gains that are of use diagnostically.

Age did not influence any significant changes in VOR gain in the studies that investigated the vHIT in different age groups from the age of 6 years. The study33 using the Synapses remote camera system successfully performed the test in children under 1 year of age where they found that the VOR gain under 1 year was significantly lower than those at 3 years. The study36 using an EyeSeeCam system noted that children between 3 and 6 years demonstrated significantly lower gain values than older children. This study did not separately analyse the VOR gain at 3, 4, 5 and 6 years and thus it is likely that the low VOR gain was mainly observed at 3 years. This is not unsurprising as high frequency VOR function matures until the age of 2 years 39,49. In addition, hypermetropia and astigmatism in children under the age of 3 years are also responsible for this gain variability39.

Most studies stressed on the importance of supplementing the vHIT with other vestibular function tests like the calorics, the rotatory chair, the VNG and the otolith vestibular evoked myogenic potential tests. The present authors consider this recommendation as a sound approach to glean a comprehensive information about vestibular function in children. Since the vestibular sensory epithelium response is tonotopic or frequency specific, there may be conditions where selective frequencies can be affected. Thus, one test assessing high frequency response like the vHIT is unlikely to give a complete picture. Furthermore, we recommend that the output from the test in children as that in adults should be analysed by the clinician followed by peer review if necessary and taken holistically along with the clinical phenotypes and other vestibular tests for most effective and meaningful information.

This review was limited by the low number of studies that have investigated vHIT in the paediatric population. The gold standard of prospective randomised controlled trials is lacking in the subject. Given the limited availability of data, a full metanalysis was not possible either. Furthermore, we have combined studies using all 3 different systems to assess VOR gain. There might be differences in output comparing the 3 systems50. There is no gold standard test to validate vHIT in children to compare high frequency canal function as scleral coil testing is not appropriate in children. Hence, diagnostic accuracy will be difficult to ascertain reiterating the previous point that other tests are recommended to be performed for a full diagnostic vestibular work up. vHIT is not a treatment, hence it cannot be compared to a sham procedure either.

However, the strengths of the studies are apparent. The quality assessment indicated that more than 80% of studies yielded meaningful conclusions with optimal statistical methods. The majority of them were prospective with adequate statistical methods applied to a representative population of children including 6 controlled studies that eliminated the bias of retrospective analysis. Most studies (80%) investigated a normal population either as the only objective or when comparing to a pathological group. Therefore, this review indicated a robust average VOR gain value in normal children, a cut off for vestibular weakness and the importance of refixation saccades in making meaningful inferences about vestibular pathology in children.

5. Conclusions

We feel that this review will set standards for performing the vHIT in children and benchmark parameters due to its strengths. Nevertheless, we also emphasize that individual laboratories should ideally establish their own norms in children for consistency. The procedure requires adequate paediatric experience and practice to eliminate artifacts. vHIT is a highly feasible non-invasive and an eminently doable investigation that can be performed in children. Crucially, this review has highlighted the special considerations in terms of the actual test and its outcome that differs from adults, reiterating a most important caveat that adult testing paradigms cannot be extrapolated directly to children.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, SDG, ALM, RC.; methodology, all authors; software, SDG, ALM, RC.; validation, SDG., RC, NGA, SR, LM.; formal analysis, SDG, RC, NGA, SR, LM, JS.; investigation, all authors.; resources, SDG, SR.; data curation, SDG, ALM, RC; writing—original draft preparation, SDG.; writing—review and editing, all authors.; visualization, SDG, ALM, RC, SD.; supervision, SDG.; project administration, SDG.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This review did not require ethical review as it did not involve human or animal experimentation.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

All data presented in article.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

- Dasgupta S, Mandala M, Guneri EA, Bassim M, Tarnutzer AA. The pioneers of vestibular physiology in the 19th century. J Laryngol Otol. 2024 May 8:1-32. [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta S, Mandala M, Guneri EA. Alexander Crum Brown: A Forgotten Pioneer in Vestibular Sciences. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020 Sep;163(3):557-559. [CrossRef]

- Halmagyi GM, Curthoys IS. A clinical sign of canal paresis. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:737-739.

- Alhabib SF, Saliba I. Video head impulse test: a review of the literature. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017 Mar;274(3):1215-1222. [CrossRef]

- Cremer PD, Halmagyi GM, Aw ST, Curthoys IS, McGarvie LA, Todd MJ, Black RA, Hannigan IP. Semicircular canal plane head impulses detect absent function of individual semicircular canals. Brain. 1998 Apr;121 ( Pt 4):699-716. [CrossRef]

- Ulmer E, Chays A. Curthoys and Halmagyi Head Impulse test: an analytical device. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2005 Apr;122(2):84-90. French. [CrossRef]

- MacDougall HG, Weber KP, McGarvie LA, Halmagyi GM, Curthoys IS. The video head impulse test: diagnostic accuracy in peripheral vestibulopathy. Neurology. 2009 Oct 6;73(14):1134-41. [CrossRef]

- MacDougall HG, McGarvie LA, Halmagyi GM, Curthoys IS, Weber KP. Application of the video head impulse test to detect vertical semicircular canal dysfunction. Otol Neurotol. 2013 Aug;34(6):974-9. [CrossRef]

- Curthoys, I. S., & Manzari, L. (2017). Clinical application of the head impulse test of semicircular canal function. Hearing, Balance and Communication, 15(3), 113–126. [CrossRef]

- Strupp M, Kim JS, Murofushi T, Straumann D, Jen JC, Rosengren SM, Della Santina CC, Kingma H. Bilateral vestibulopathy: Diagnostic criteria Consensus document of the Classification Committee of the Bárány Society. J Vestib Res. 2017;27(4):177-189. https://doi.org/10.3233/VES-170619. Erratum in: J Vestib Res. 2023;33(1):87. [CrossRef]

- Park HG, Lee JH, Oh SH, Park MK, Suh MW. Proposal on the Diagnostic Criteria of Definite Isolated Otolith Dysfunction. J Audiol Otol. 2019 Apr;23(2):103-111. [CrossRef]

- Wiener-Vacher SR, Hamilton DA, Wiener SI. Vestibular activity and cognitive development in children: perspectives. Front Integr Neurosci. 2013 Dec 11;7:92. [CrossRef]

- Li CM, Hoffman HJ, Ward BK, Cohen HS, Rine RM. Epidemiology of Dizziness and Balance Problems in Children in the United States: A Population-Based Study. J Pediatr. 2016 Apr;171:240-7.e1-3. [CrossRef]

- Money-Nolan LE, Flagge AG. Factors affecting variability in vestibulo-ocular reflex gain in the Video Head Impulse Test in individuals without vestibulopathy: A systematic review of literature. Front Neurol. 2023 Mar 9;14:1125951. [CrossRef]

- McGarvie LA, MacDougall HG, Halmagyi GM, Burgess AM, Weber KP, Curthoys IS. The Video Head Impulse Test (vHIT) of Semicircular Canal Function - Age-Dependent Normative Values of VOR Gain in Healthy Subjects. Front Neurol. 2015 Jul 8;6:154. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Quan Nha et al. ‘The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018 for Information Professionals and Researchers’. 1 Jan. 2018: 285 – 291.

- Abakay MA, Kufecilar L, Yazici ZM et al. Determination of Normal Video Head Impulse Test Gain Values in Different Age Group. Turkey Clinics J Med Sci.2020;40(4):406-9. [CrossRef]

- Nurul Ain Abdullah, Nor Haniza Abdul Wahat, Curthoys, I. S., Asma Abdullah, & Hamidah Alias. (2017). The feasibility of testing otoliths and semicircular canals function using VEMPs and vHIT in Malaysian children. Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. http://journalarticle.ukm.my/11490/.

- Alizadeh S, et al. Normative vestibulo-ocular reflex data in 6-12 year-old children using video headimpulse test. Aud Vestib Res. 2017;26(3):145–50.

- Bachmann K, et al. Video head impulse testing in a pediatric population: normative findings. J Am Acad Audiol. 2018;29(5):417–26.

- Bayram A, et al. Clinical practice of horizontal video head impulse test in healthy children. Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis Derg. 2017;27(2):79–83. [CrossRef]

- Emekci T, Uğur KŞ, Cengiz DU, Men Kılınç F. Normative values for semicircular canal function with the video head impulse test (vHIT) in healthy adolescents. Acta Otolaryngol. 2021 Feb;141(2):141-146. [CrossRef]

- Ertugrul G. Clinical use of child-friendly video head impulse test in dizzy children. Am J Otolaryngol. 2022 May-Jun;43(3):103432. [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta S. The video head impulse test in different vestibular pathologies in children. Vestibular Hackathon, Peckforton UK. 2018 (content on request https://www.alderhey.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Alder-Hey-Quality-Report-17-18.pdf).

- Hamilton SS, Zhou G, Brodsky JR. Video head impulse testing (VHIT) in the pediatric population. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;79(8):1283–7. [CrossRef]

- Van Hecke R, Deconinck FJA, Danneels M, Dhooge I, Uzeel B, Maes L. A Clinical Framework for Video Head Impulse Testing and Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potential Assessments in Primary School-Aged Children. Ear Hear. 2024 Sep-Oct 01;45(5):1216-1227. [CrossRef]

- Hulse R, et al. Clinical experience with video head impulse test in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;79(8):1288–93. [CrossRef]

- Khater AM, Afifif PO. Video head-impulse test (vHIT) in dizzy children with normal caloric responses. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;87:172–7. [CrossRef]

- Kim KS, Jung YK, Hyun KJ, Kim MJ, Kim HJ. Usefulness and practical insights of the pediatric video head impulse test. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020 Dec;139:110424. [CrossRef]

- Kirbac A, Kaya E, Incesulu SA, Carman KB, Yarar C, Ozen H, Pinarbasli MO, Gurbuz MK. Differentiation of peripheral and non-peripheral etiologies in children with vertigo/dizziness: The video-head impulse test and suppression head impulse paradigm. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2024 Apr;179:111935. [CrossRef]

- Lehnen N, Ramaioli C, Todd NS, Bartl K, Kohlbecher S, Jahn K, Schneider E. Clinical and video head impulses: a simple bedside test in children. J Neurol. 2017 May;264(5):1002-1004. [CrossRef]

- Lissner, V. M. H., Devantier, L., & Ovesen, T. (2019). Using the video head impulse test in healthy Danish adolescents. Hearing, Balance and Communication, 18(1), 49–54. [CrossRef]

- Martens S, Dhooge I, Dhondt C, Vanaudenaerde S, Sucaet M, Rombaut L, Maes L. Pediatric Vestibular Assessment: Clinical Framework. Ear Hear. 2023 Mar-Apr 01;44(2):423-436. [CrossRef]

- Renata P, et al. Application of the video head impulse test in the diagnostics of the balance system in children. Pol Otorhino Rev. 2015;4(2):6–11. [CrossRef]

- Retamal SR, Díaz PO, Fernández AM, Muñoz CG, Espinoza MR, Araya VS, Rivera JT. Assessment protocol and reference values of vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) gain in the horizontal plane recorded with video-Head Impulse Test (vHIT) in a pediatric population. Codas. 2021 Jul 5;33(4):e20200076. Spanish, English. PMID: 34231764. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Villalba R, Caballero-Borrego M. Normative values for the video Head Impulse Test in children without otoneurologic symptoms and their evolution across childhood by gender. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2023 Sep;280(9):4037-4043. [CrossRef]

- Ross LM, Helminski JO. Test-retest and interrater reliability of the video head impulse test in the pediatric population. Otol Neurotol. 2016 Jun;37(5):558–63. [CrossRef]

- Sommerfleck PA, et al. Balance disorders in childhood: main etiologies according to age. Usefulness of the video head impulse test. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016; 87:148–53. [CrossRef]

- Wiener-Vacher SR, Wiener S. Video head impulse tests with a remote camera system: normative values of semicircular canal vestibulo-ocular reflex gain in infants and children. Front Neurol. 2017; 8:434. [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz E; Yağcı I; Kesimli MC; Altundağ A. Comparison of Video Head Impulse Test Results of Pediatric Patients with Dizziness with Healthy Volunteers. Turkish Journal of Ear Nose & Throat (Tr-ENT), 2022, Vol 32, Issue 4, p121. [CrossRef]

- Zhou G, Goutos C, Lipson S, Brodsky J. Range of Peak Head Velocity in Video Head Impulse Testing for Pediatric Patients. Otol Neurotol. 2018 Jun;39(5):e357-e361. [CrossRef]

- Zhou G, Yun A, Wang A, Brodsky JR. Comparing Video Head Impulse Testing With Rotary Chair in Pediatric Patients: A Controlled Trial. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2024 Oct;171(4):1190-1196. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Fernandez N, Eza-Nuñez P. Normal Gain of VOR with Refixation Saccades in Patients with Unilateral Vestibulopathy. J Int Adv Otol. 2015 Aug;11(2):133-7. [CrossRef]

- Korsager LE, Faber CE, Schmidt JH, Wanscher JH. Refixation Saccades with Normal Gain Values: A Diagnostic Problem in the Video Head Impulse Test: A Case Report. Front Neurol. 2017 Mar 14;8:81. [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta S, Crunkhorn R, Wong J, McMahon A, Ratnayake S, Manzari L. Suppression head impulse test in children-experiences in a tertiary paediatric vestibular centre. Front Neurol. 2024 Mar 14;15:1297707. [CrossRef]

- Suh MW, Park JH, Kang SI, Lim JH, Park MK, Kwon SK. Effect of Goggle Slippage on the Video Head Impulse Test Outcome and Its Mechanisms. Otol Neurotol. 2017 Jan;38(1):102-109. [CrossRef]

- Naranjo EN, Cleworth TW, Allum JH, Inglis JT, Lea J, Westerberg BD, Carpenter MG. Vestibulo-spinal and vestibulo-ocular reflexes are modulated when standing with increased postural threat. J Neurophysiol. 2016 Feb 1;115(2):833-42. [CrossRef]

- Claes Von Hofsten, Kerstin Rosander. Development of smooth pursuit tracking in young infants. Vision Research. Volume 37, Issue 13 1997 Pages 1799-1810. [CrossRef]

- O'Reilly R, Grindle C, Zwicky EF, Morlet T. Development of the vestibular system and balance function: differential diagnosis in the pediatric population. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2011 Apr;44(2):251-71, vii. [CrossRef]

- George M, Kolethekkat AA, Yoan P, Maire R. Video Head Impulse Test: A Comparison and Analysis of Three Recording Systems. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023 Mar;75(1):60-66. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).