Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Narrative Process

3. Results

3.1. Reconsidering Being a Researcher

The group was a good introduction to get me thinking on many topics and how to approach any given topic without it bogging me down. I have learned it requires patience and in research, one can never come up with 100% hard and fast conclusions on anything. I have also learned I am not really a “researcher” but the group has helped me to grasp that with any topic, research is very important. Learning to approach topics that have personally impacted me, objectively has been of great value. If a person can overcome how one particular topic/issue has emotionally impacted them and become clear thinking and grounded on their experience, they can communicate better on how to help themselves and others who go through a like experience. Or simply use it as a teaching method. Writing narratives are also useful to sort out information and experiences. They are a great tool to use when approaching many subjects/situations. They help to solve puzzles and they surprisingly offer solutions and/or inspirations for the next chapter.

3.2. Recognizing a Deeper Problem

Sometime after having my first child, my husband tried to gently broach the topic of my “fatigue” and irritability being more a result of unexpressed sadness rather than simply an issue of lack of sleep. I would often blame my moodiness and lack of energy on late bedtimes. In truth, he was right but it took many years to be able to acknowledge and understand the unresolved trauma and its impact on my physical state. This was not the first time he had tried to point this out, but by this time I had done several years of intensive therapy and trained as trauma therapist, so had gained tools to be able to receive his words and perspective and process them in a forward moving way.

3.3. Negative Advice From a Counselor

A person I wish I hadn’t met is a counselor I met with in my first year at U of T. In my first year, I was not doing well at all mentally and academically; which is something I think a lot of students go through, but I did not know that. I decided to try and pick myself up the best way I could, and started reaching out to faculty members, counselors, and taking appointments with them. I met with a counselor who I asked for advice about my first year, when I was still in the beginning of my second semester. She was very nice and considerate, however; it felt like the chat was not personal, and that she was just reciting a same conversation she says to every student she meets with. At this time, I needed encouragement and comfort, as it was just the beginning of my health related journey, yet she did not provide that, but instead told me in a way that I could not get where I wanted to be, and that it is too late for me, which was not true. After the conversation, I thought what I liked doing was not for me. I wish she had let me know that it was just the beginning of my journey, and that if I put the effort in, I could have picked myself up and done better academically.

3.4. Confronting Self-Doubt

COVID-19 and the isolation and anxiety it brought highlighted a lot of very negative attitudes I had towards my education and my future. Even prior to the pandemic I found it difficult to look forward, ask myself questions, and prioritize my health and wellbeing. With isolation I realized I had been so intensely geared towards producing that I had neglected every aspect of myself that I had not deemed useful in whatever I was doing at the time. It got rough. Although I still do struggle with that, finding time and understanding the importance of asking myself why and how and where do I as a person with history and heart fit, I do think that HeNReG has helped illustrate the importance of that. Putting the person back into the researcher. I think it's really cool and I believe it has really helped me understand that it takes conscious effort to unlearn all of the harmful ideas that have been injected into a lot of us.

3.5. The Influence of Why Questions

4. Discussion

4.1. A Health Narratives Pregnancy Process

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Halkos, G.; Gkampoura, E.-C. Where Do We Stand on the 17 Sustainable Development Goals? An Overview on Progress. Economic Analysis and Policy 2021, 70, 94–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoušková, S.; Hák, T.; Moldan, B. Global SDGs Assessments: Helping or Confusing Indicators? Sustainability 2018, 10, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; Hickmann, T.; Sénit, C.-A.; Beisheim, M.; Bernstein, S.; Chasek, P.; Grob, L.; Kim, R.E.; Kotzé, L.J.; Nilsson, M.; et al. Scientific Evidence on the Political Impact of the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat Sustain 2022, 5, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, I.; Cuervo-Cazurra, A.; Park, J.; Antolín-López, R.; Husted, B.W. Implementing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals in International Business. J Int Bus Stud 2021, 52, 999–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davarpanah, A.; Babaie, H.; Dhakal, N. Semantic Modeling of Climate Change Impacts on the Implementation of the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals Related to Poverty, Hunger, Water, and Energy. Earth Sci Inform 2023, 16, 929–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, D.; Fortier, F.; Boucher, J.; Riffon, O.; Villeneuve, C. Sustainable Development Goal Interactions: An Analysis Based on the Five Pillars of the 2030 Agenda. Sustainable Development 2020, 28, 1584–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoyiannis, D. Rethinking Climate, Climate Change, and Their Relationship with Water. Water 2021, 13, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Change: Observed Impacts on Planet Earth; Letcher, T.M., Ed.; Third edition.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2021; ISBN 978-0-12-821575-3.

- Fuso Nerini, F.; Sovacool, B.; Hughes, N.; Cozzi, L.; Cosgrave, E.; Howells, M.; Tavoni, M.; Tomei, J.; Zerriffi, H.; Milligan, B. Connecting Climate Action with Other Sustainable Development Goals. Nat Sustain 2019, 2, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Naturalistic Decision-Making in Intentional Communities: Insights from Youth, Disabled Persons, and Children on Achieving United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for Equality, Peace, and Justice. Challenges 2024, 15, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.-W.; Pielke, R.A.; Zeng, X.; Baik, J.-J.; Faghih-Naini, S.; Cui, J.; Atlas, R.; Reyes, T.A.L. Is Weather Chaotic? Coexisting Chaotic and Non-Chaotic Attractors Within Lorenz Models. In 13th Chaotic Modeling and Simulation International Conference; Skiadas, C.H., Dimotikalis, Y., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Complexity; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 805–825. ISBN 978-3-030-70794-1. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, T.N. Predicting Uncertainty in Forecasts of Weather and Climate. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2000, 63, 71–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, K.; Qasim, M.Z.; Song, H.; Murshed, M.; Mahmood, H.; Younis, I. A Review of the Global Climate Change Impacts, Adaptation, and Sustainable Mitigation Measures. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2022, 29, 42539–42559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlis, T.M.; Cheng, K.-Y.; Guendelman, I.; Harris, L.; Bretherton, C.S.; Bolot, M.; Zhou, L.; Kaltenbaugh, A.; Clark, S.K.; Vecchi, G.A.; et al. Climate Sensitivity and Relative Humidity Changes in Global Storm-Resolving Model Simulations of Climate Change. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadn5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Corredores, M.M.; Goldwasser, M.R.; Falabella De Sousa Aguiar, E. Carbon Dioxide and Climate Change. In Decarbonization as a Route Towards Sustainable Circularity; SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp. 1–14. ISBN 978-3-031-19998-1. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, G. Fossil Fuels in a Carbon-Constrained World. In The Palgrave Handbook of Managing Fossil Fuels and Energy Transitions; Wood, G., Baker, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 3–23. ISBN 978-3-030-28075-8. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry, S.; Sidhu, G.P.S. Climate Change Regulated Abiotic Stress Mechanisms in Plants: A Comprehensive Review. Plant Cell Rep 2022, 41, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Azam, W. Natural Resource Scarcity, Fossil Fuel Energy Consumption, and Total Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Top Emitting Countries. Geoscience Frontiers 2024, 15, 101757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.P.; Ozturk, I. The Impacts of Globalization, Financial Development, Government Expenditures, and Institutional Quality on CO2 Emissions in the Presence of Environmental Kuznets Curve. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2020, 27, 22680–22697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.M.; Husnain, M.I.U.; Azimi, M.N. An Environmental Perspective of Energy Consumption, Overpopulation, and Human Capital Barriers in South Asia. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holechek, J.L.; Geli, H.M.E.; Sawalhah, M.N.; Valdez, R. A Global Assessment: Can Renewable Energy Replace Fossil Fuels by 2050? Sustainability 2022, 14, 4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedemann, A.J. Life after Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; Lecture notes in energy; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-70335-6. [Google Scholar]

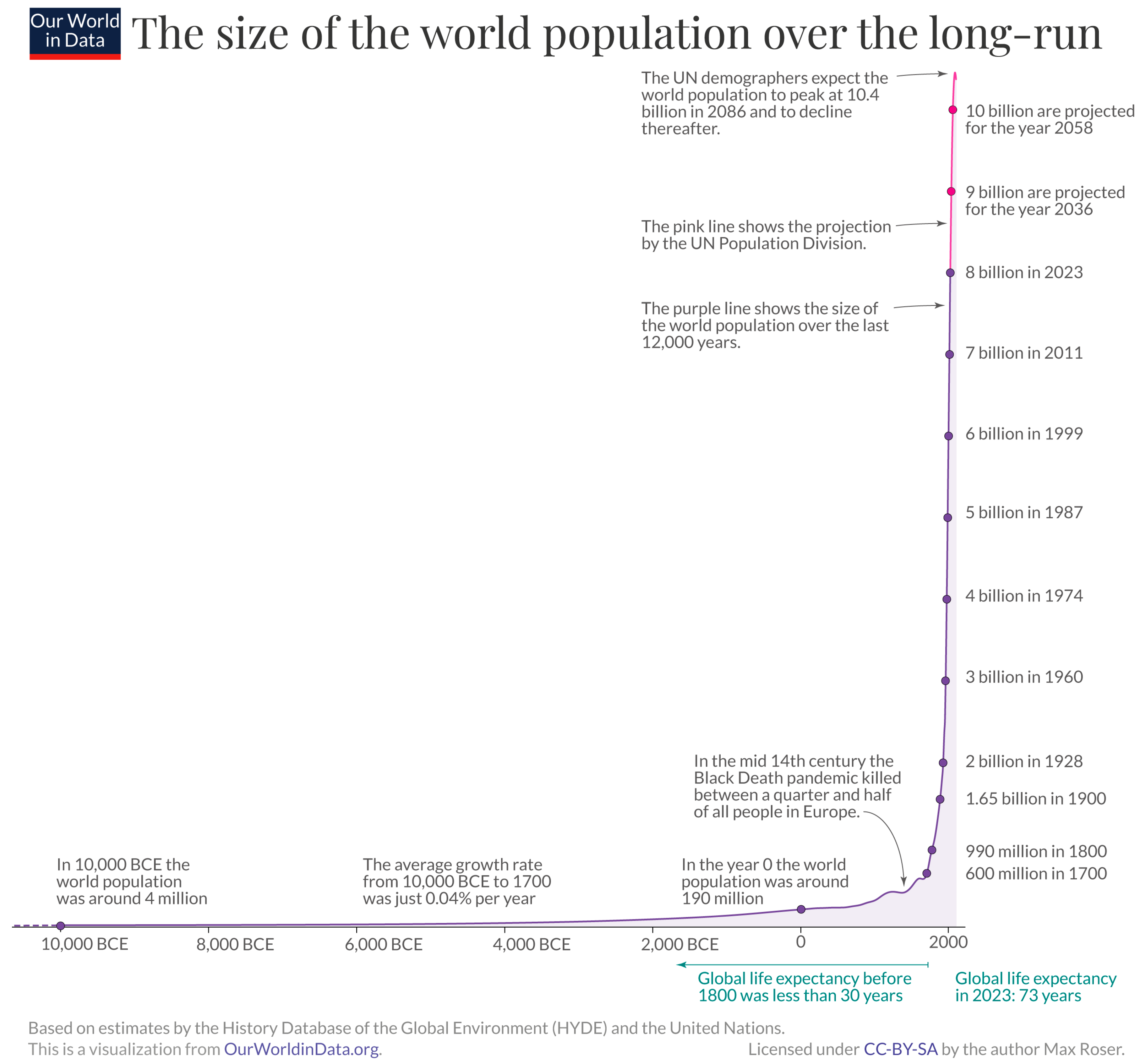

- Roser, M.; Ritchie, H. How Has World Population Growth Changed over Time? Our World in Data 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Villani, M.; Serra, R. Super-Exponential Growth in Models of a Binary String World. Entropy 2023, 25, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLong, J.P.; Burger, O. Socio-Economic Instability and the Scaling of Energy Use with Population Size. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Keinan, A. Inference of Super-Exponential Human Population Growth via Efficient Computation of the Site Frequency Spectrum for Generalized Models. Genetics 2016, 202, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, S. Pandora’s Seed: The Unforseen Cost of Civilization; 1st ed.; Random House: New York, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4000-6215-7. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, T.R.; Sinclair, C.J. Bread, Beer, and the Seeds of Change: Agriculture’s Impact on World History; CABI: Wallingford, Oxfordshire, UK ; Cambridge, MA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-84593-705-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bellwood, P.S. First Farmers: The Origins of Agricultural Societies; Second edition.; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, 2023; ISBN 978-1-119-70637-3. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Agriculture for Food Security: A Global Perspective; Bālakr̥shṇa, Ed.; First edition.; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1-77463-756-2.

- Sanford, T. Agricultural Revolution. In A Whirlwind History of the Universe and Mankind; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2024; pp. 41–55. ISBN 978-981-9726-73-8. [Google Scholar]

- Riehl, S. Archaeobotanical Evidence for the Interrelationship of Agricultural Decision-Making and Climate Change in the Ancient Near East. Quaternary International 2009, 197, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, O. Reading Genesis 1.28 with a Plea for Planetary Responsibility. In Market, Ethics and Religion; Kærgård, N., Ed.; Ethical Economy; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; Vol. 62, pp. 159–170. ISBN 978-3-031-08461-4. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. “Be Fertile and Increase, Fill the Earth and Master It”: The Ancient and Medieval Career of a Biblical Text; Cornell paperbacks; 1. print. Cornell Pb.; Cornell Univ. Press: Ithaca, N.Y., 1992; ISBN 978-0-8014-8053-9. [Google Scholar]

- Günther, I.; Harttgen, K. Desired Fertility and Number of Children Born Across Time and Space. Demography 2016, 53, 55–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polgar, S. Population History and Population Policies from an Anthropological Perspective. Current Anthropology 1972, 13, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.L.; Smith, G.N. Pregnancy Complications, Cardiovascular Risk Factors, and Future Heart Disease. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America 2020, 47, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramlakhan, K.P.; Johnson, M.R.; Roos-Hesselink, J.W. Pregnancy and Cardiovascular Disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020, 17, 718–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewey, J.; Andrade, L.; Levine, L.D. Valvular Heart Disease in Pregnancy. Cardiology Clinics 2021, 39, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, A.A.; Devi Rajeswari, V. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus - A Metabolic and Reproductive Disorder. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2021, 143, 112183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaitescu, A.M.; Popescu, M.R.; Ciobanu, A.M.; Gica, N.; Cimpoca-Raptis, B.A. Pregnancy Complications Can Foreshadow Future Disease—Long-Term Outcomes of a Complicated Pregnancy. Medicina 2021, 57, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Täufer Cederlöf, E.; Lundgren, M.; Lindahl, B.; Christersson, C. Pregnancy Complications and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Later in Life: A Nationwide Cohort Study. JAHA 2022, 11, e023079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieger, J.A.; Hutchesson, M.J.; Cooray, S.D.; Bahri Khomami, M.; Zaman, S.; Segan, L.; Teede, H.; Moran, L.J. A Review of Maternal Overweight and Obesity and Its Impact on Cardiometabolic Outcomes during Pregnancy and Postpartum. Clin Med�Insights�Reprod�Health 2021, 15, 2633494120986544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrales, P.; Vidal-Puig, A.; Medina-Gómez, G. Obesity and Pregnancy, the Perfect Metabolic Storm. Eur J Clin Nutr 2021, 75, 1723–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, R.; Morton, V.H.; Morris, R.K. Childbirth-Related Perineal Trauma and Its Complications: Prevalence, Risk Factors and Management. Obstetrics, Gynaecology & Reproductive Medicine 2024, 34, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage-Fransen, M.A.H.; Wiezer, M.; Otto, A.; Wieffer-Platvoet, M.S.; Slotman, M.H.; Nijhuis-van Der Sanden, M.W.G.; Pool-Goudzwaard, A.L. Pregnancy- and Obstetric-related Risk Factors for Urinary Incontinence, Fecal Incontinence, or Pelvic Organ Prolapse Later in Life: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2021, 100, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moossdorff-Steinhauser, H.F.A.; Berghmans, B.C.M.; Spaanderman, M.E.A.; Bols, E.M.J. Prevalence, Incidence and Bothersomeness of Urinary Incontinence in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int Urogynecol J 2021, 32, 1633–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalawmpuii, A.; Taksande, V.; Mahakarkar, M. Grade IV Utero Vaginal Prolapse (Procidentia): A Case Report. JPRI 2021, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, G. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Postpartum Depression in Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2022, 31, 2665–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanardo, V.; Giliberti, L.; Giliberti, E.; Grassi, A.; Perin, V.; Parotto, M.; Soldera, G.; Straface, G. The Role of Gestational Weight Gain Disorders in Symptoms of Maternal Postpartum Depression. Intl J Gynecology & Obste 2021, 153, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R. Religion’s Sudden Decline: What’s Causing It, and What Comes Next? Oxford University press: New York (N.Y.), 2021; ISBN 978-0-19-754704-5. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R.F. Giving Up on God. Foreign Affairs 2020, 99, 110–118. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider-Mayerson, M.; Leong, K.L. Eco-Reproductive Concerns in the Age of Climate Change. Climatic Change 2020, 163, 1007–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrman, K.-E. World Population Growth: A Once and Future Global Concern. World 2023, 4, 684–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donath, O.; Berkovitch, N.; Segal-Engelchin, D. “I Kind of Want to Want”: Women Who Are Undecided About Becoming Mothers. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 848384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.; Farb, N.; Pogrebtsova, E.; Gruman, J.; Grossmann, I. What Do People Mean When They Talk about Mindfulness? Clinical Psychology Review 2021, 89, 102085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiesa, A. The Difficulty of Defining Mindfulness: Current Thought and Critical Issues. Mindfulness 2013, 4, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, M.; Tilley, J.L.; Im, S.; Price, K.; Gonzalez, A. A Systematic Review of Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia and Caregivers. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2021, 34, 528–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, B.; Lindsay, E.K.; Greco, C.M.; Brown, K.W.; Smyth, J.M.; Wright, A.G.C.; Creswell, J.D. Mindfulness Interventions Improve Momentary and Trait Measures of Attentional Control: Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 2021, 150, 686–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adelian, H.; Khodabandeh Shahraki, S.; Miri, S.; Farokhzadian, J. The Effect of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction on Resilience of Vulnerable Women at Drop-in Centers in the Southeast of Iran. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.; Cain, K. The Use of Questions to Scaffold Narrative Coherence and Cohesion. Journal Research in Reading 2019, 42, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fina, A. Doing Narrative Analysis from a Narratives-as-Practices Perspective. NI 2021, 31, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntinda, K. Narrative Research. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2018; pp. 1–13. ISBN 978-981-10-2779-6. [Google Scholar]

- Renjith, V.; Yesodharan, R.; Noronha, J.A.; Ladd, E.; George, A. Qualitative Methods in Health Care Research. Int J Prev Med 2021, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fludernik, M. The Diachronization of Narratology: Dedicated to F. K. Stanzel on His 80th Birthday. Narrative 2003, 11, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, P. Psychoanalytic Constructions and Narrative Meanings. Paragraph 1986, 7, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R.; Godzich, W. Story and Situation: Narrative Seduction and the Power of Fiction; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 1984; ISBN 978-0-8166-8204-1. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra, A.M.C.; De Oliveira Moreira, J.; De Oliveira, L.V.; E Lima, R.G. The Narrative Memoir as a Psychoanalytical Strategy for the Research of Social Phenomena. PSYCH 2017, 08, 1238–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, S.-A. Narratology and Narrative Theory. In The Routledge Handbook of Translation History; Routledge: London, 2021; pp. 54–69. ISBN 978-1-315-64012-9. [Google Scholar]

- Birke, D.; Von Contzen, E.; Kukkonen, K. Chrononarratology: Modelling Historical Change for Narratology. Narrative 2022, 30, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zekri Masson, S. Autobiography and the Autobiographical Mode as Narrative Resistances. An Interdisciplinary Perspective. EJLW 2022, 11, AN1–AN10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroni, R.; Paschoud, A. Introduction: Time and Narrative, the Missing Link between the “Narrative Turn” and Postclassical Narratology? Poetics Today 2021, 42, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civitarese, G. Does It Appear to ‘Resemble’ Reality? On the Ethics of Psychoanalytic Writing. The Psychoanalytic Quarterly 2024, 93, 105–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havron, E. In Search of the Empty Moment in Psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis, Self and Context 2024, 19, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. A Narrative Development Process to Enhance Mental Health Considering Recent Hippocampus Research. Arch Psychiatry 2024, 2, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Team Mindfulness in Online Academic Meetings to Reduce Burnout. Challenges 2023, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Report on Digital Literacy in Academic Meetings during the 2020 COVID-19 Lockdown. Challenges 2020, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Online Meeting Challenges in a Research Group Resulting from COVID-19 Limitations. Challenges 2021, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Enhancing Hopeful Resilience Regarding Depression and Anxiety with a Narrative Method of Ordering Memory Effective in Researchers Experiencing Burnout. Challenges 2022, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Maintaining a Focus on Burnout in Medical Students. Journal of Mental Health Disorders 2023, 3, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Historical Study of an Online Hospital-Affiliated Burnout Intervention Process for Researchers. J Hosp Manag Health Policy 2023, 0, 0–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, E.H.; Kim, K.H. Relationship between Optimism, Emotional Intelligence, and Academic Resilience of Nursing Students: The Mediating Effect of Self-Directed Learning Competency. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1182689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, N.B.B.; Dafny, H.A.; Baldwin, C.; Jakimowitz, S.; Chalmers, D.; Aroury, A.M.A.; Chamberlain, D. What Are the Solutions for Well-Being and Burn-out for Healthcare Professionals? An Umbrella Realist Review of Learnings of Individual-Focused Interventions for Critical Care. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, N. The Relationship Between Social Intelligence, Self-Esteem With Psychological Resilience For Healthcare Professionals And Affecting Factors. Psi Hem Derg 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, T.; Keville, S.; Cain, A.; Adler, J.R. Facilitating Reflection: A Review and Synthesis of the Factors Enabling Effective Facilitation of Reflective Practice. Reflective Practice 2022, 23, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, Y.; Sharma, K. Six Facets of Facilitation: Participatory Design Facilitators’ Perspectives on Their Role and Its Realization. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New Orleans LA USA, April 29 2022. pp. 1–14.

- Camussi, E.; Meneghetti, D.; Rella, R.; Sbarra, M.L.; Calegari, E.; Sassi, C.; Annovazzi, C. Life Design Facing the Fertility Gap: Promoting Gender Equity to Give Women and Men the Freedom of a Mindful Life Planning. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1176663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuenkel, C.A. Reproductive Milestones across the Lifespan and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Women. Climacteric 2024, 27, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanbury, C. Population, Climate Change and the Philosopher’s Message. Aust. J. environ. educ. 2024, 40, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaluzeviciute, G. The Role of Empathy in Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy: A Historical Exploration. Cogent Psychology 2020, 7, 1748792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, S.; De Luca Picione, R.; Vincenzo, B.; Mannino, G.; Langher, V.; Pergola, F.; Velotti, P.; Venuleo, C. The Affectivization of the Public Sphere: The Contribution of Psychoanalysis in Understanding and Counteracting the Current Crisis Scenarios. Subject, Action, & Society: Psychoanalytical Studies and Practices 2021, 1, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | UN Sustainable Goals | HumanInteraction | Standard of Living | Organizational Structures | Planetary Care |

| 1 | No poverty | ⬜️ | |||

| 2 | Zero hunger | ⬜️ | |||

| 3 | Good health and well-being | ⬜️ | |||

| 4 | Quality education | ⬜️ | |||

| 5 | Gender equality | ⬜️ | |||

| 6 | Clean water and sanitation | ⬜️ | |||

| 7 | Affordable and clean energy | ⬜️ | |||

| 8 | Decent work and economic growth | ⬜️ | |||

| 9 | Industry, innovation and infrastructure | ⬜️ | |||

| 10 | Reduced inequalities | ⬜️ | |||

| 11 | Sustainable cities and communities | ⬜️ | |||

| 12 | Responsible consumption and production | ⬜️ | |||

| 13 | Climate action | ⬜️ | |||

| 14 | Life below water | ⬜️ | |||

| 15 | Life on land | ⬜️ | |||

| 16 | Peace, justice, and strong institutions | ⬜️ | |||

| 17 | Partnerships | ⬜️ |

| Order | First Word | Body of Question |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Describe | yourself regarding your research related to health |

| 2 | When | were you first interested in your research topic |

| 3 | When | did you start to feel distanced from your research |

| 4 | When | did you think you might need help with your research |

| 5 | When | did you wonder if you were pursuing the right research topic |

| 6 | Where | do you go to devote time to your research |

| 7 | Where | are you most comfortable discussing your research |

| 8 | Where | do you feel supported for working on your research |

| 9 | Where | are you most frustrated in accomplishing your research |

| 10 | Who | has devoted time to helping you pursue your research |

| 11 | Who | has kept you away from your research |

| 12 | Who | do you want to impress with your work on your research |

| 13 | Who | has provided you with the most inspiration in your research |

| 14 | What | holds you back from finding time for your research |

| 15 | What | place gives you the most joy in conducting your research |

| 16 | What | could you do to inform others of your research |

| 17 | What | significant thing do you want to accomplish in your research |

| 18 | How | has time gotten away from you as a researcher |

| 19 | How | have you found a productive place to research |

| 20 | How | would you improve to reach others as a researcher |

| 21 | How | do you organize yourself to be most effective as a researcher |

| 22 | How | would you do things differently restarting as a researcher |

| 23 | Why | have you not spent enough time as a researcher |

| 24 | Why | do you think you need a new location to research |

| 25 | Why | are people not understanding you as a researcher |

| 26 | Why | is your research valuable |

| 27 | Why | do you need to find a new approach to your research |

| 28 | Why | are you reconsidering the reason you research |

| Order | First Word | Body of Question |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Describe | yourself regarding your potential to become pregnant |

| 2 | When | have you thought about how long pregnancy lasts |

| 3 | When | did you consider where you would live if pregnant |

| 4 | When | did you visualize the ideal man to impregnate you |

| 5 | When | have you worried about the possibility of pregnancy |

| 6 | Where | could you get help most quickly if you were pregnant |

| 7 | Where | would you go to determine if you were pregnant |

| 8 | Where | is the healthcare provider you would go to if pregnant |

| 9 | Where | do you go online to get information about pregnancy |

| 10 | Who | has spent time with you talking about pregnancy |

| 11 | Who | would give you a place to live if you were pregnant |

| 12 | Who | would tell others about your pregnancy |

| 13 | Who | has offered you valuable information about pregnancy |

| 14 | What | would you do during the nine months of pregnancy |

| 15 | What | would be comfortable in your home if you were pregnant |

| 16 | What | support would the father provide if you were pregnant |

| 17 | What | would you do if you were pregnant |

| 18 | How | would you organize your time commitments if pregnant |

| 19 | How | would you meet with your healthcare provider if pregnant |

| 20 | How | much would you tell the father about your pregnancy |

| 21 | How | would you know if you wanted to be pregnant |

| 22 | How | do you decide what information is relevant about pregnancy |

| 23 | Why | is this not the right time to be pregnant |

| 24 | Why | do concerns about the earth matter regarding pregnancy |

| 25 | Why | is there tension between men and women about pregnancy |

| 26 | Why | does it matter what you would do if you were pregnant |

| 27 | Why | should you know the health-related issues of pregnancy |

| 28 | Why | are you reconsidering your responsibility to be pregnant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).