Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

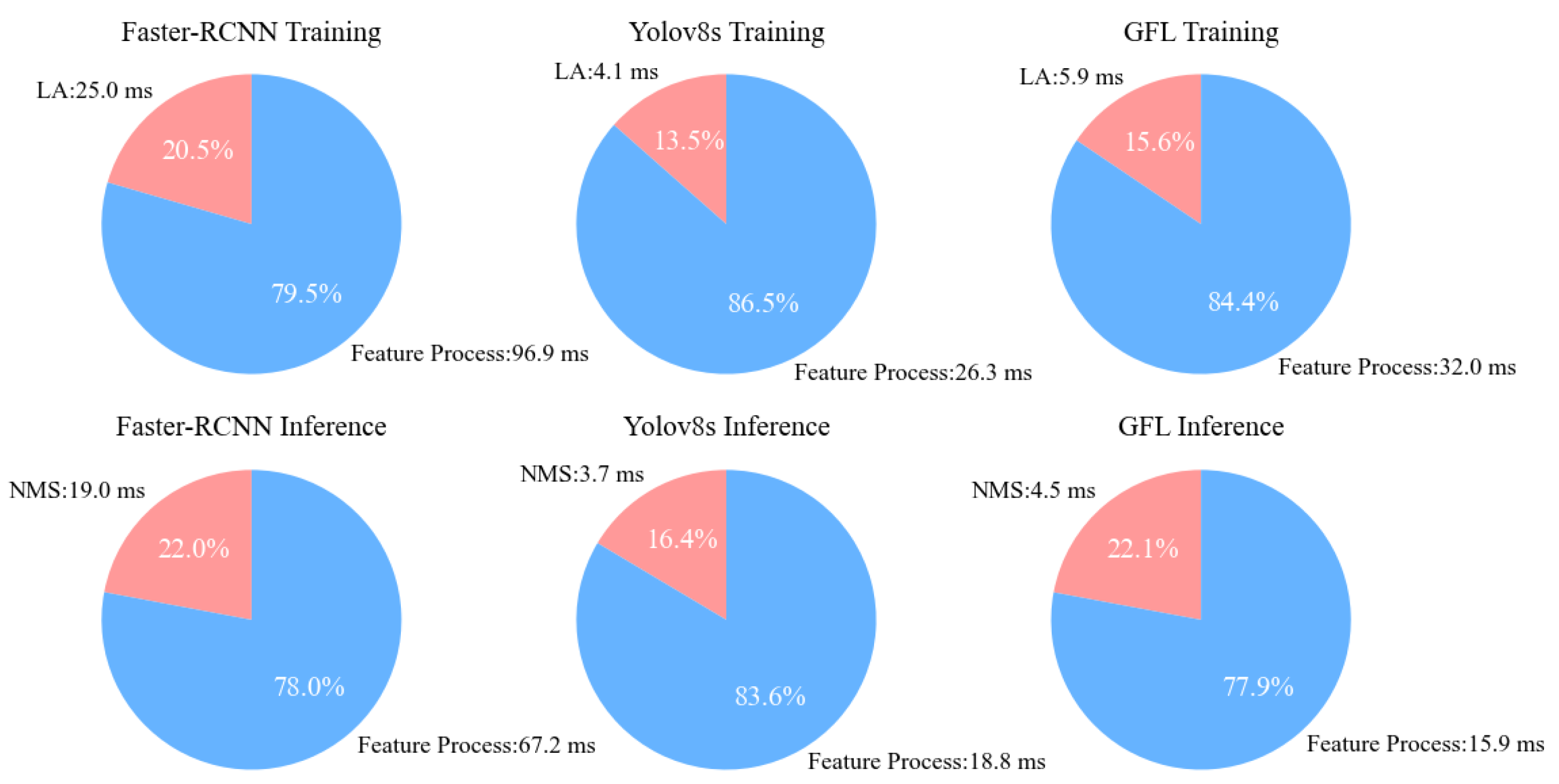

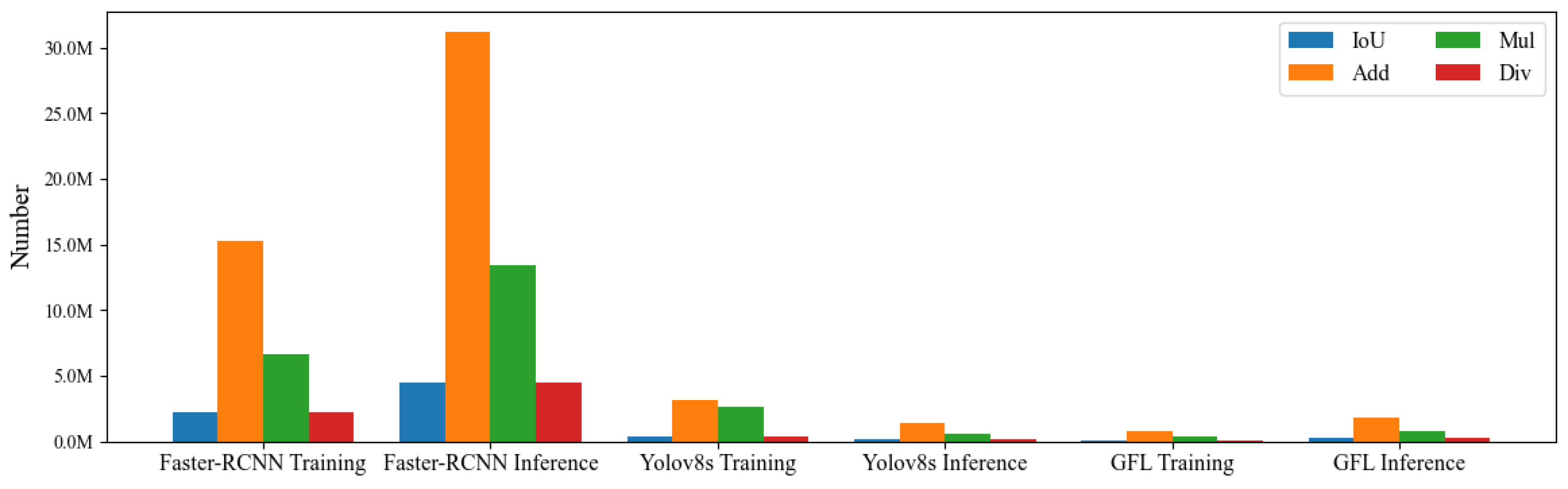

Deep learning significantly advances object detection. Post process, a critical component of this process, selects valid bounding boxes to represent true targets during inference and assigns boxes and labels to these objects during training to optimize the loss function. However, post process constitutes a substantial portion of the total processing time for a single image. This inefficiency primarily arises from the extensive Intersection over Union (IoU) calculations required between numerous redundant bounding boxes in post-processing algorithms. To reduce the redundant IoU calculations, we introduce a classification prioritization strategy during both training and inference post processes. Additionally, post process involves sorting operations that contribute to inefficiency. To minimize unnecessary comparisons in Top-K sorting, we have improved the bitonic sorter by developing a hybrid bitonic algorithm. These improvements have effectively accelerated post process. Given the similarities between training and inference post processes, we unify four typical post-processing algorithms and design a hardware accelerator based on this framework. Our accelerator achieves at least 7.55 times the speed in inference post process compared to recent accelerators. When compared to the RTX 2080 Ti system, our proposed accelerator offers at least 21.93 times the speed for training post process and 19.89 times for inference post process, thereby significantly enhancing the efficiency of loss function minimization.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

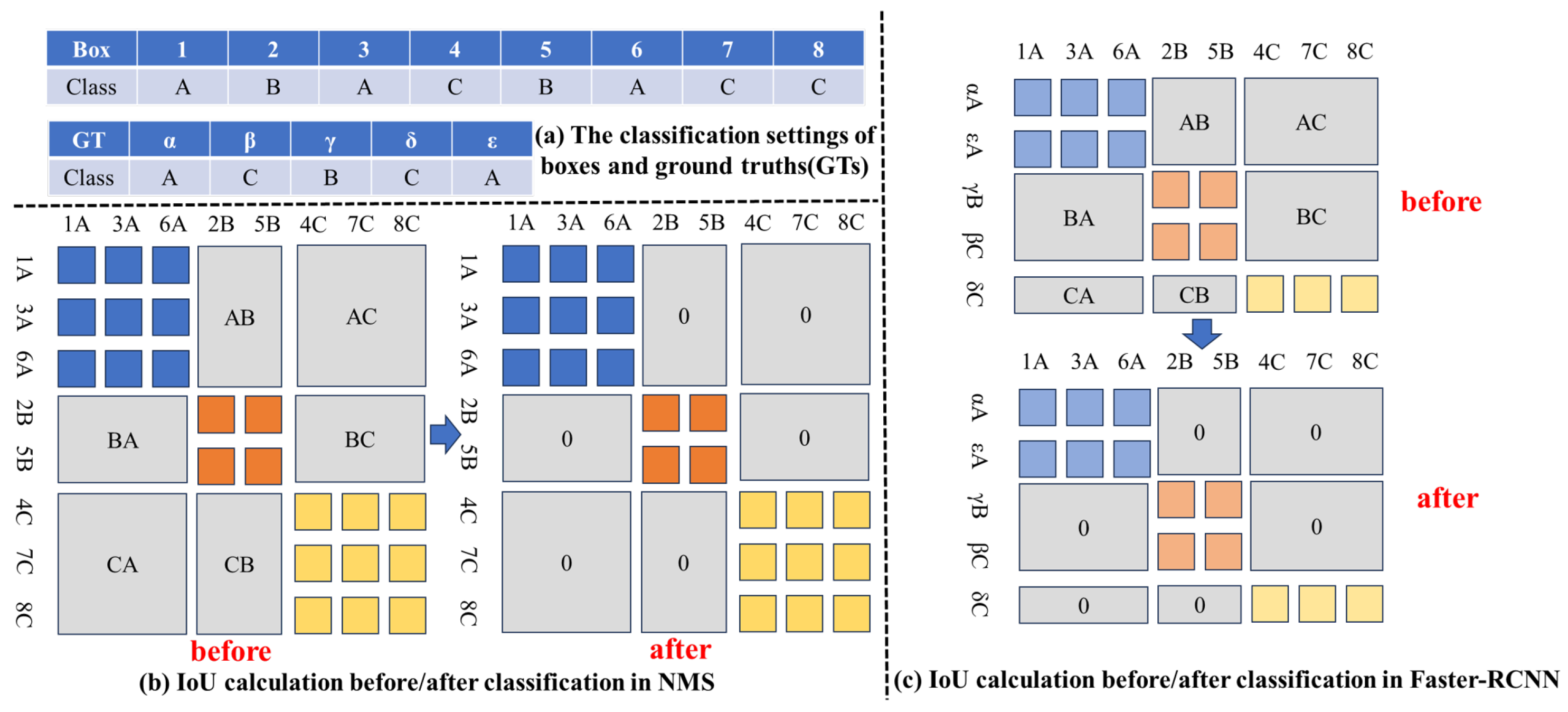

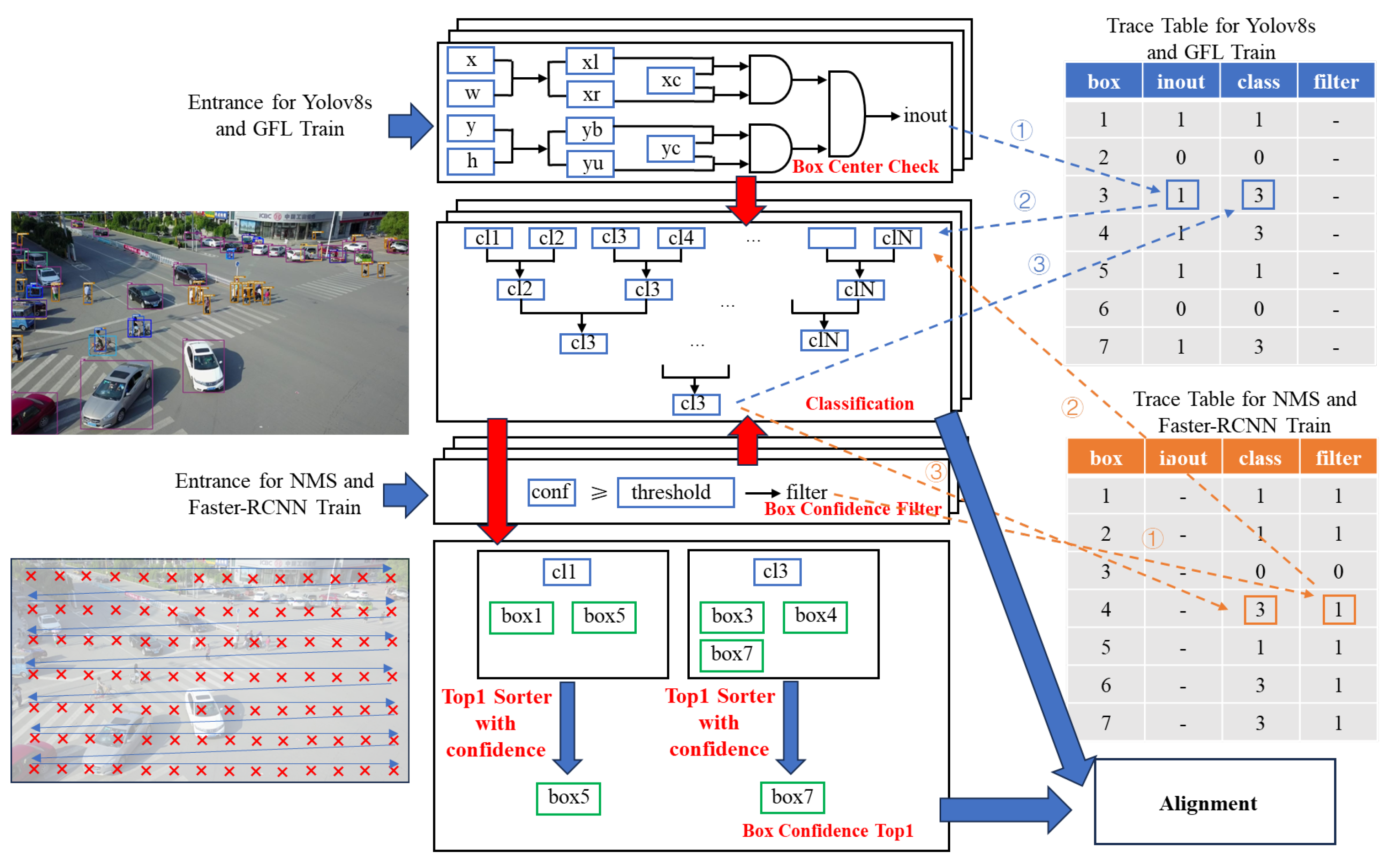

- Minimizing Redundant IoU Calculations: Traditional post-processing methods often involve redundant IoU calculations between redundant bounding boxes. To address this, we introduce priority of confidence threshold checking combined with classification (CTC-C) into NMS, effectively reducing the computation of ineffective IoUs. Given the operational similarities between inference post process and training post process, we also implement priority of confidence threshold checking combined with classification (CTC-C) in the training post process of Faster-RCNN. For YOLOv8s and GFL, we incorporate priority of center point position checking combined with classification (CPC-C) to further reduce redundant IoU calculations. We propose a unified algorithmic framework for these four common post-processing methods and present a design for a corresponding hardware accelerator.

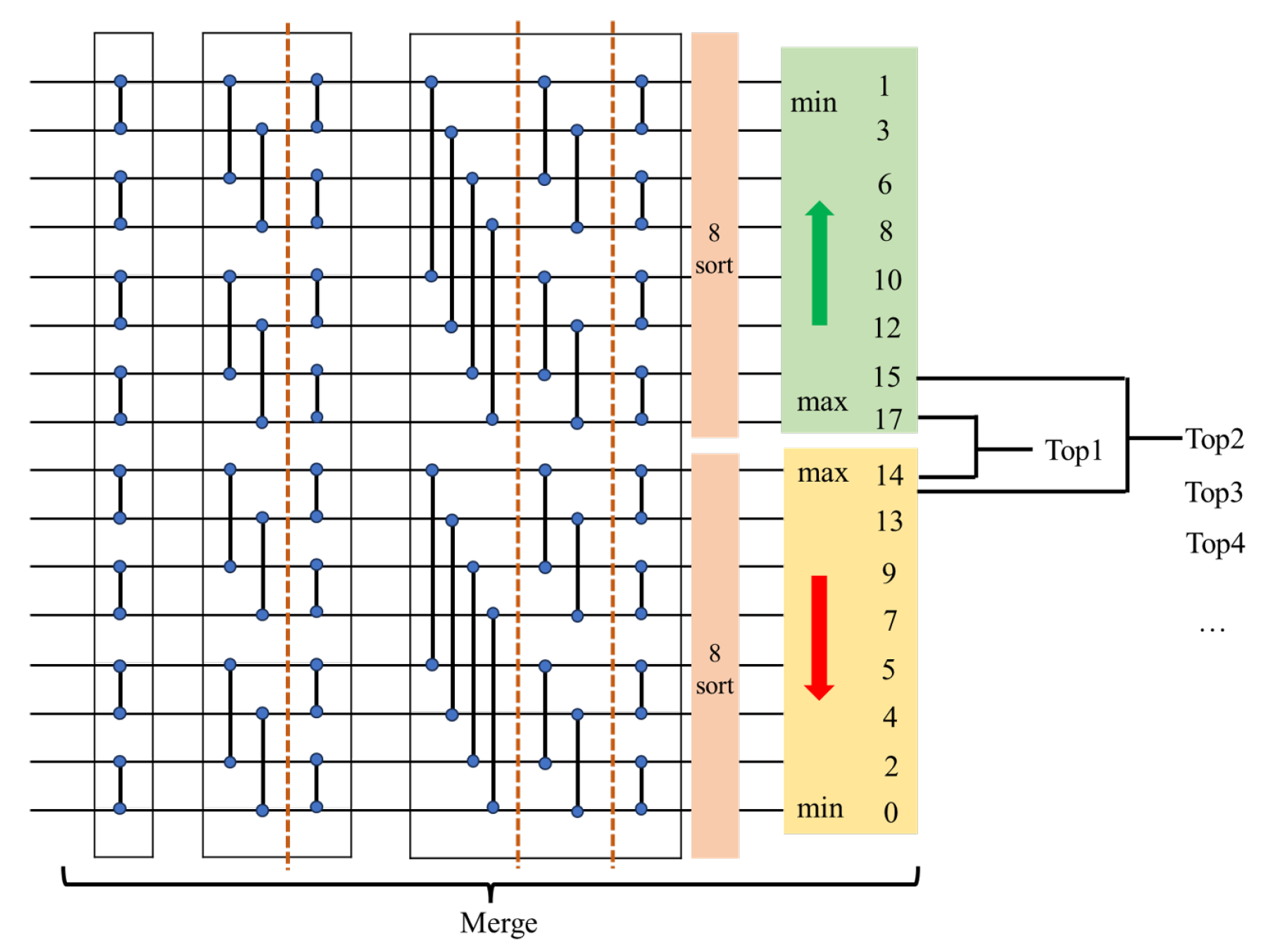

- Reducing Redundant Comparisons: Traditional Top-K element selection methods often involve full sorting, which introduces unnecessary comparisons among non-essential elements. To overcome this, we introduce the hybrid bitonic sorter, which avoids redundant comparisons. We detail the algorithm and hardware design of the hybrid bitonic sorter, which efficiently performs IoU sorting for bounding boxes and rapidly identifies the Top-K elements, thereby optimizing the selection of the best bounding boxes during training post process.

- Data-level Parallelism Computing with Categories: By applying principles such as priority of CTC-C and CPC-C, we can determine the category of each bounding box prior to IoU calculation. This allows for simultaneous and independent execution of IoU computations and subsequent operations across different categories.

- Parallel Sorting: We incorporate bitonic sorting to facilitate parallel comparisons. Unlike sorting algorithms with limited parallelism, bitonic sorting offers significantly higher efficiency and speed.

- Significance of Post Processing Software-Hardware Acceleration: This paper explores the critical importance of hardware acceleration in both training and inference post processing phases. We propose a co-design strategy that integrates both software and hardware to enhance the efficiency of post process.

- Unified Algorithm Framework and Hardware Design: We analyze the feasibility of unifying the algorithms for training and inference post processes and present a hardware designing framework based on a unified algorithmic workflow. The accelerator achieves a minimum speedup of 7.55 times for NMS acceleration compared to recent accelerators. When evaluated solely through IP simulation, our design demonstrates superior acceleration performance relative to the number of bounding boxes. Compared to the RTX 2080 Ti system, our solution provides a minimum speedup of 21.93 times for training post process and 19.89 times for inference post process.

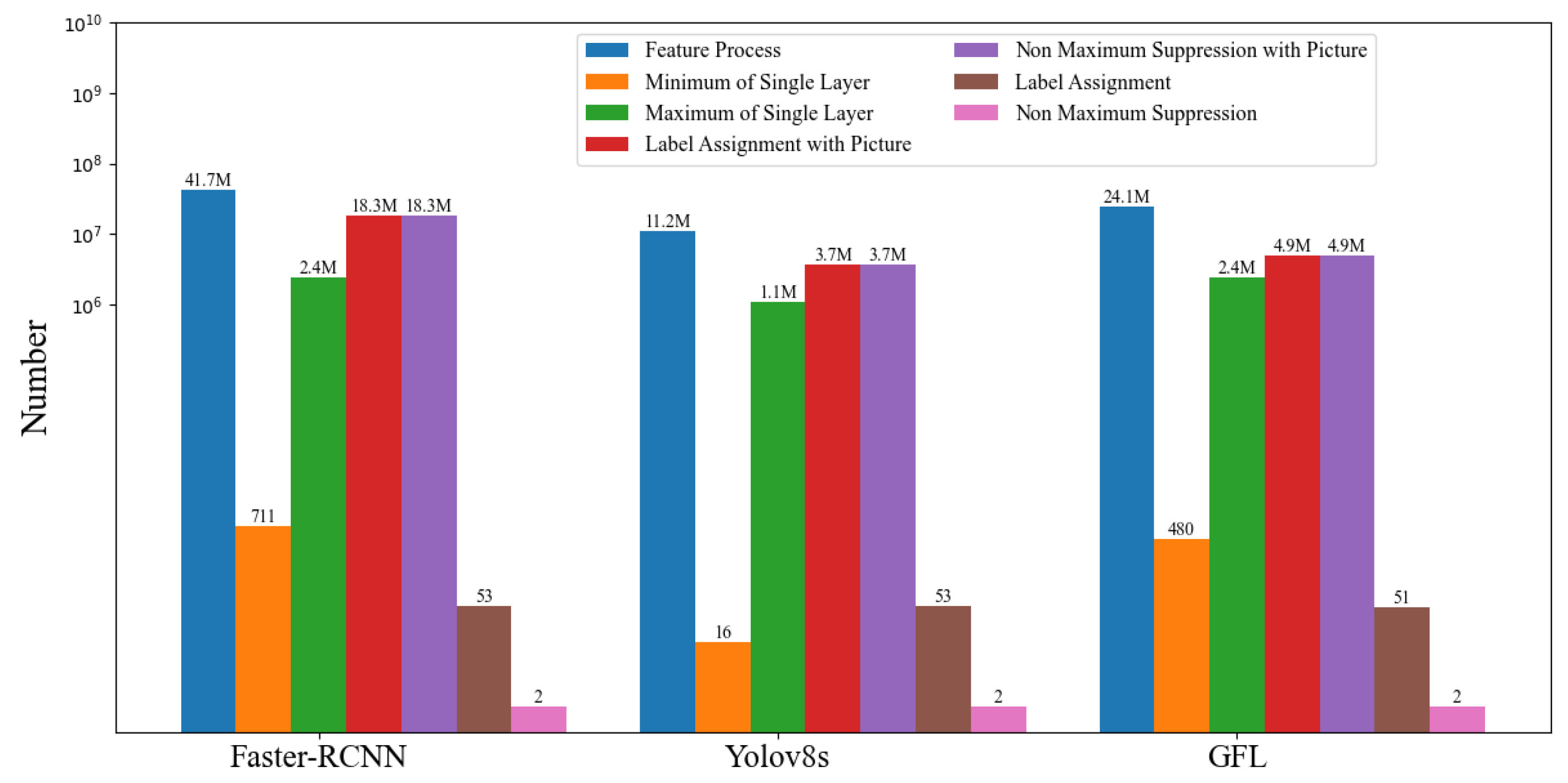

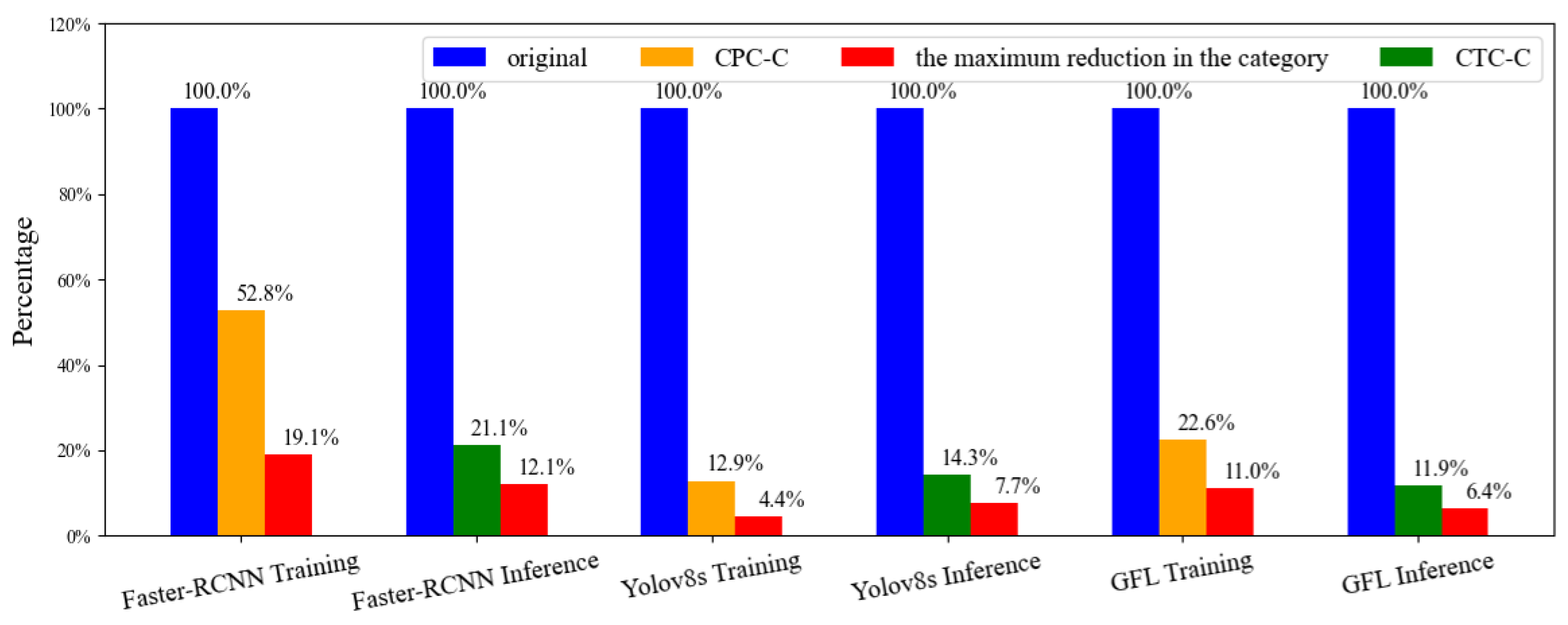

- Reduction of Redundant IoU Calculations: We address the issue of redundant IoU calculations in training and inference post-processing algorithms. By introducing priority of CTC-C in NMS and Faster-RCNN training post process, as well as CPC-C in YOLOv8s and GFL training post process, we effectively reduce the computation of ineffective IoUs. This reduction improves algorithmic efficiency and supports effective software and hardware co-design. With the application of bounding box center point position checking (CPC) and confidence threshold checking (CTC), the number of bounding boxes is reduced to 12.9% and 11.9% of the original count, respectively. Classification further limits the number of maximum bounding boxes per class to 4.4%–19.1% of the original. These reductions validate the effectiveness of our approach, achieving a maximum speedup of 1.19 times and a minimum of 1.10 times.

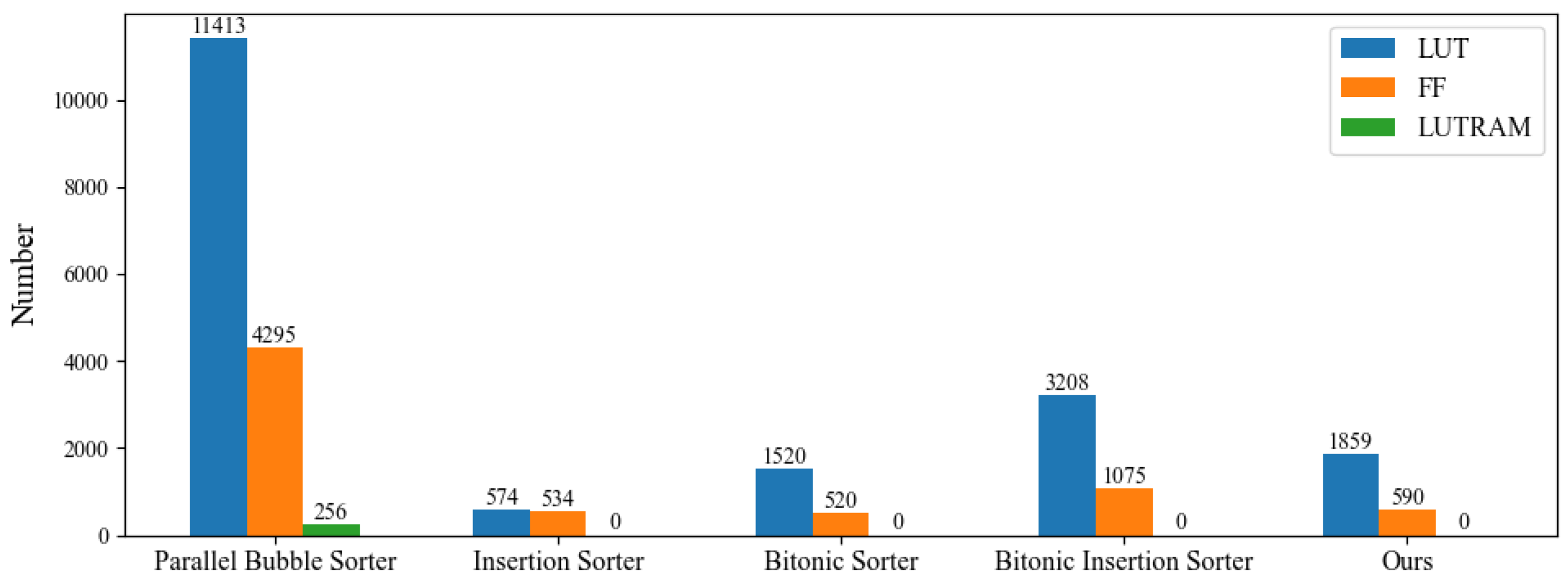

- Design of Hybrid Bitonic Sorter: We introduce the hybrid bitonic sorter algorithm and its hardware implementation. The bitonic sorter enables highly parallel comparisons, and the Top-K algorithm within the hybrid sorter maintains this parallelism, reducing redundant comparisons typical in traditional Top-K element selection. This enhancement in sorting algorithm efficiency results in a more effective hardware solution, achieving high-performance co-design for both full sorting and Top-K sorting. Our design provides a maximum speedup of 1.25 times and a minimum of 1.05 times compared to recent sorters.

2. The Related Works

2.1. Object Detection and Post Process Algorithm

2.2. The Hardware Accelerator in Inference Post-Processing Algorithms

2.3. The Hardware Accelerator in Sorter Algorithm

3. The Unification of Post Process Algorithm and Optimization

3.1. Analysis of the Uniformity of Post-Processing Algorithms

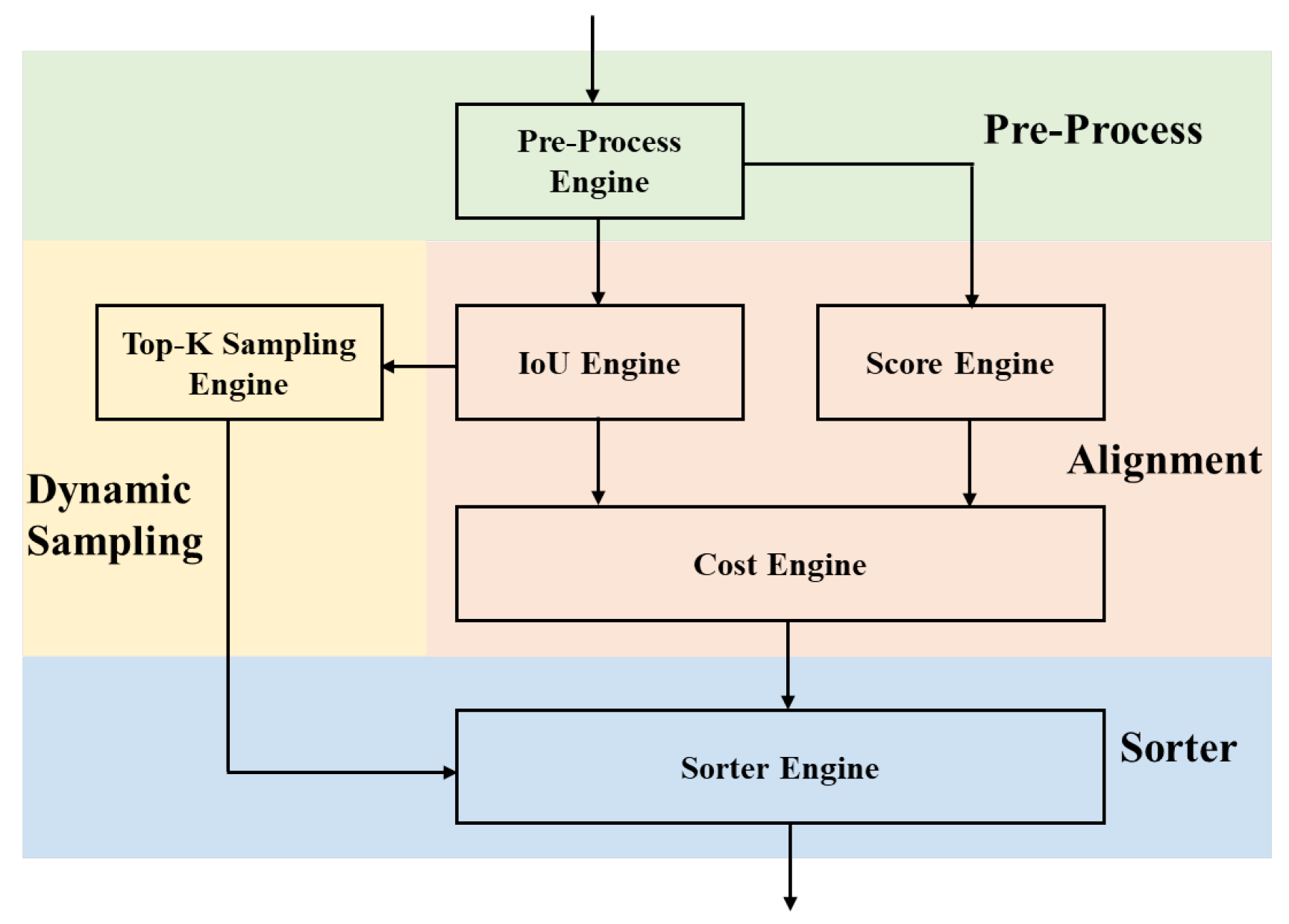

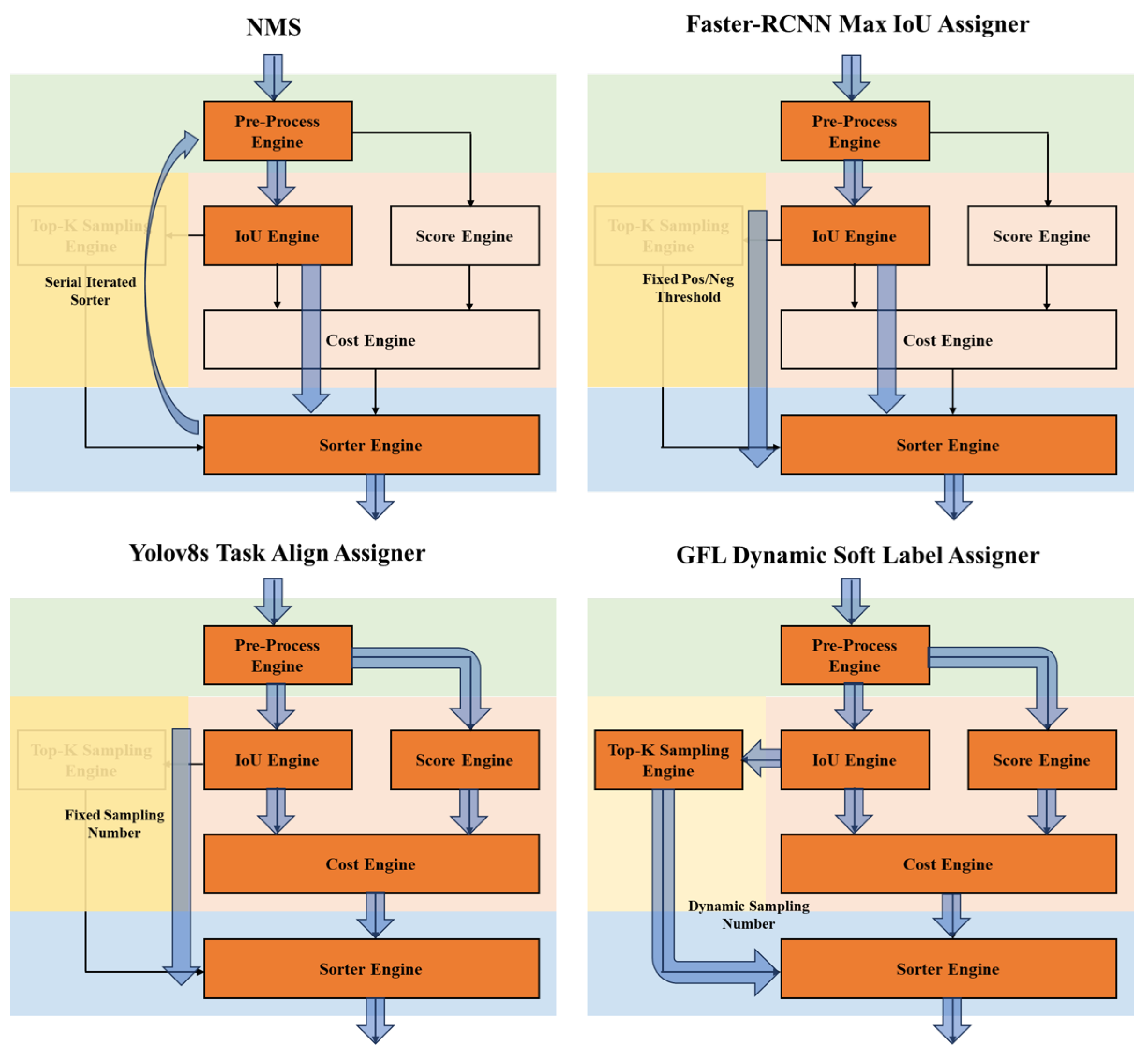

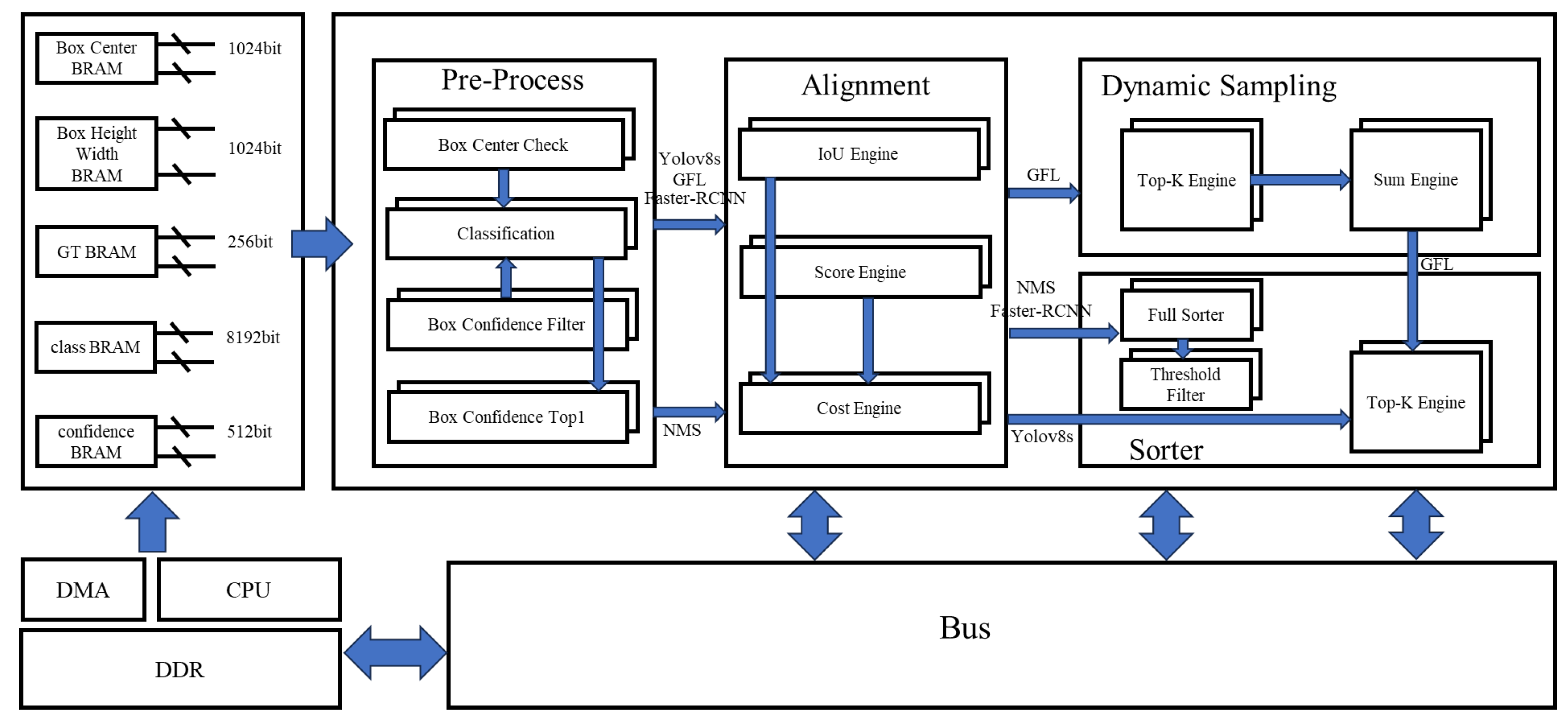

- Step 1. Pre-Process: This step involves extracting the bounding box with the highest confidence or verifying whether the bounding box center point is within the ground truth boxes. To be detailed, as shown in Figure 4, the light green background represents the Pre-Process stage, where the input is data related to bounding boxes, and the output is qualified bounding boxes that have undergone classification, confidence judgment, and center determination of the bounding box. The core element is the Pre-Process Engine.

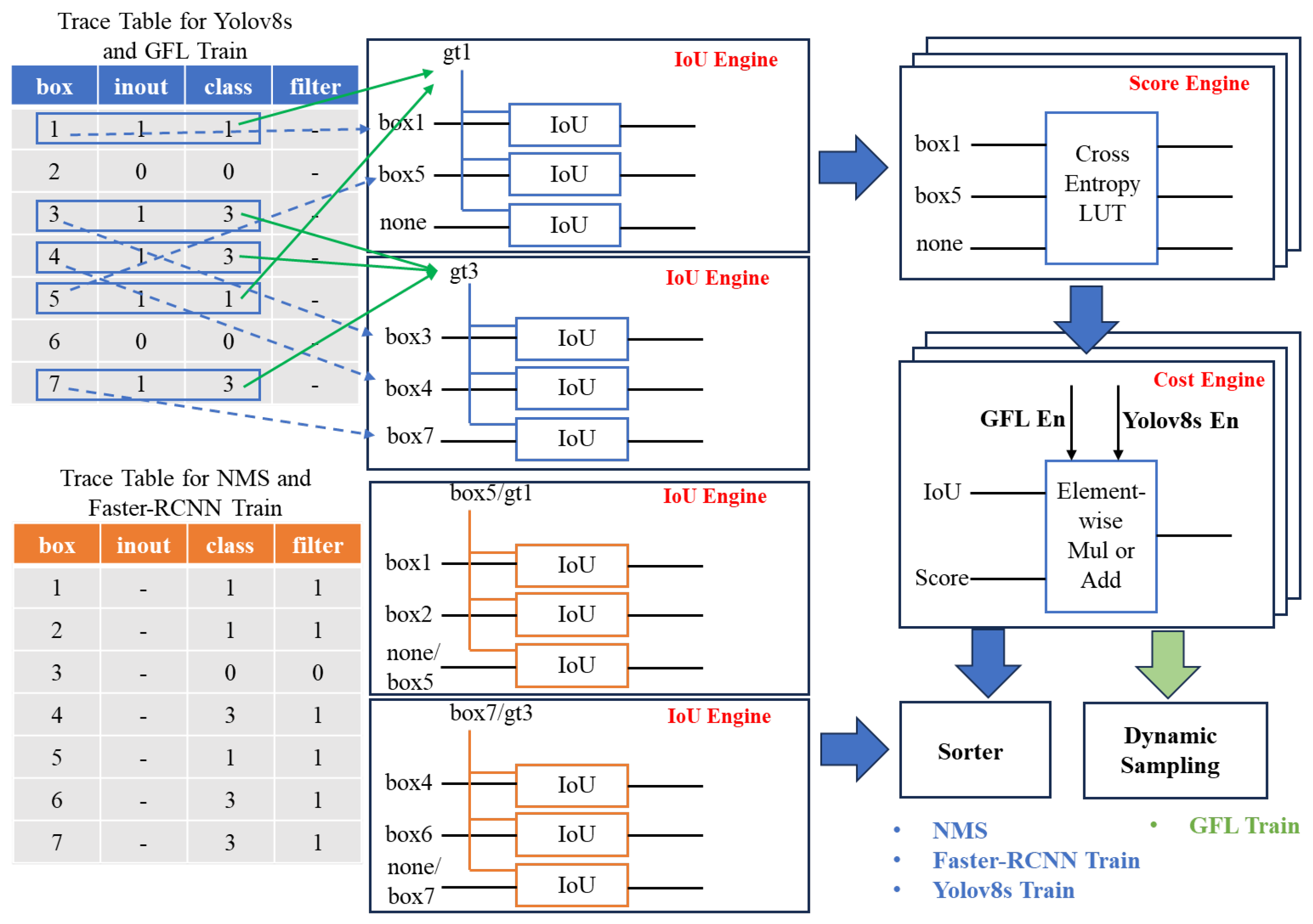

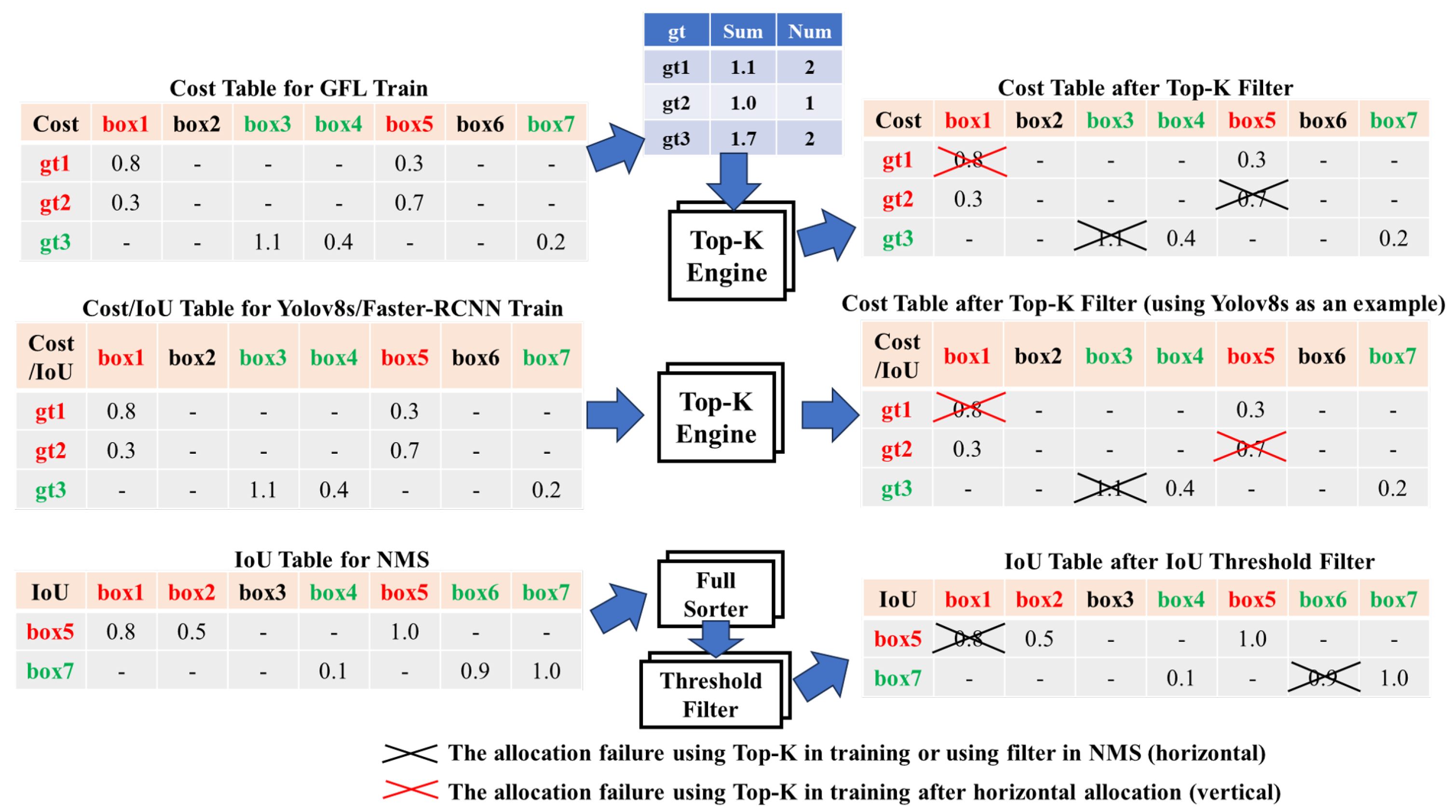

- Step 2. Alignment: This step calculates the IoU between the bounding boxes and the ground truth. Both the Task Align Assigner and the Dynamic Soft Label Assigner additionally compute alignment scores by integrating classification values with IoU. As shown in Figure 4, the light pink background represents the Alignment stage, where the input includes the coordinate and category information of qualified bounding boxes, as well as the coordinate and category information of ground truth. Possible outputs include the IoU matrix and alignment score matrix constructed based on qualified bounding boxes and ground truth. The core elements are the IoU Engine, Score Engine, and Cost Engine, with the IoU Engine responsible for calculating the IoU matrix, the Score Engine responsible for calculating the classification score matrix, and the Cost Engine responsible for calculating the alignment score matrix.

- Step 3. Dynamic Sampling: This step determines the number of bounding boxes corresponding to each ground truth target, a requirement specific to the Dynamic Soft Label Assigner based on its alignment scores. In Figure 4, the light yellow background represents the Dynamic Sampling stage, where the input is the alignment score matrix, and the output is the maximum number of bounding boxes that each ground truth can be assigned to. The core element is the Top-K Sampling Engine, used only for Dynamic Soft Label Assigner.

- Step 4. Sorter: This final step involves sorting and selecting bounding boxes based on IoU matrix or alignment score matrix. In Figure 4, the light blue background represents the Sorter stage, where possible inputs include the IoU matrix, alignment score matrix, and the number of bounding boxes that each ground truth can be assigned to, with the output being the assignment of bounding boxes to each ground truth or true target.

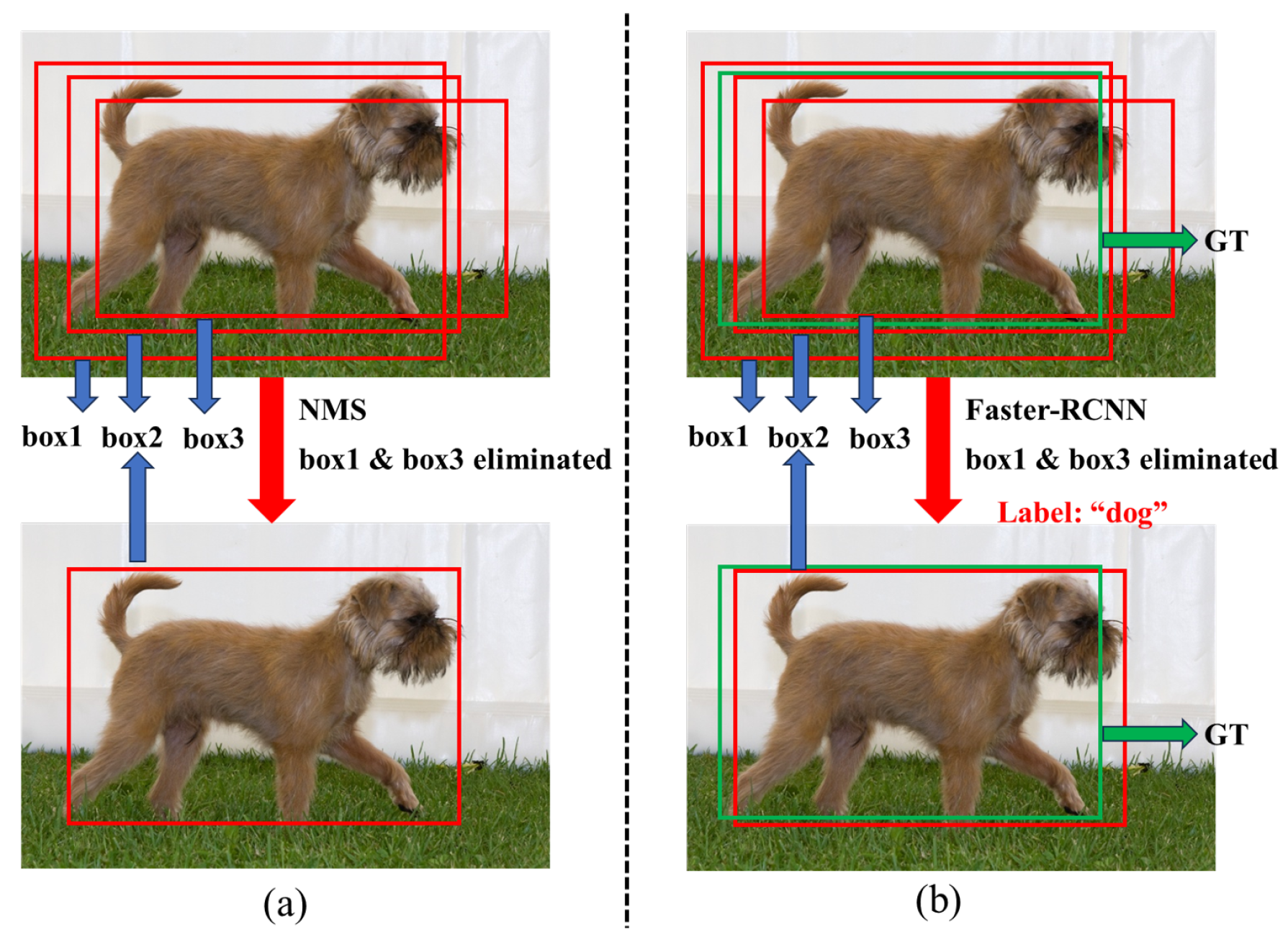

- NMS: In the Pre-Process stage, NMS identifies the bounding box with the highest confidence score. During the Alignment stage, it calculates the IoU between the selected bounding box and the remaining ones. In the Sorter stage, IoUs are sorted, and bounding boxes are filtered based on predefined IoU thresholds. This iterative process continues until no bounding boxes remain.

- Max IoU Assigner: This algorithm filters bounding boxes based on confidence in the Pre-Process stage. It then computes the IoU matrix between bounding boxes and ground truth boxes in the Alignment stage. In the Sorter stage, IoUs are sorted and used to filter bounding boxes according to IoU thresholds, mapping each bounding box to its corresponding ground truth box.

- Task Align Assigner: In the Pre-Process stage, this algorithm filters bounding boxes based on confidence. The Alignment stage involves calculating IoU matrix and alignment score matrix. During the Sorter stage, alignment scores are sorted, and bounding boxes are selected based on a fixed number of boxes per ground truth target, mapping them accordingly.

- Dynamic Soft Label Assigner: This method filters bounding boxes based on confidence in the Pre-Process stage. It calculates IoU matrix and alignment score matrix, using both classification and IoU, during the Alignment stage. The number of allowable bounding boxes per ground truth target is determined based on alignment scores in Dynamic Sampling stage. In the Sorter stage, alignment scores are sorted, and bounding boxes are selected according to the number required for each ground truth target, effectively mapping them to the ground truth boxes.

3.2. Redundancy Analysis of Post-Processing Algorithms

3.3. Redundancy Optimizations for Post-Processing Algorithms

4. Accelerator Framework Design

4.1. Overall Framework Design of Accelerator

4.2. The Design of Hybrid Bitonic Sorter

4.3. The Design of Pre-Process Submodule

4.4. The Design of Alignment Submodule

4.5. The Design of Dynamic Sampling and Sorter Submodules

5. Experiments and Results Analysis

5.1. Experimental Setup

5.2. Redundancy Results Analysis

5.3. Analysis of Results for Sorter Optimization

5.4. Analysis of Results for Post-Processing Accelerator

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, Y.; Yang, J.; Chen, L.; Li, K.; Sima, C.; Zhu, X.; Chai, S.; Du, S.; Lin, T.; Wang, W.; Lu, L.; Jia, X.; Liu, Q.; Dai, J.; Qiao, Y.; Li, H. Planning-oriented Autonomous Driving. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, Canada, 17-23 June 2023; pp. 17853–17862. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Lin, Z.; Shan, X.; Wang, Y.; Sun, D.; Yang, M.H. DrivingGaussian: Composite Gaussian Splatting for Surrounding Dynamic Autonomous Driving Scenes. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, Washington, USA, 17-21 June 2024; pp. 21634–21643. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, M.; Jacob, F.; Duveiller, G. Remote sensing for agricultural applications: A meta-review. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 236, 111402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandome, P.; Leauthaud, C.; Moinard, S.; Sainlez, O.; Mekki, I.; Zairi, A.; Belaud, G. Making technological innovations accessible to agricultural water management: Design of a low-cost wireless sensor network for drip irrigation monitoring in Tunisia. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 4, 100227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, R.; Kereszturi, G.; Pullanagari, R.; Durance, P.; Ashraf, S.; Anderson, C. Mineral prospecting from biogeochemical and geological information using hyperspectral remote sensing - Feasibility and challenges. J. Geochem. Explor. 2022, 232, 106900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Chen, F.; Wang, J.; Hao, X.; Chen, H.; Liu, H. Prospecting criteria for skarn-type iron deposits in the thick overburden area of Qihe-Yucheng mineral-rich area using geological and geophysical modelling. J. Appl. Geophys. 2024, 105442. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, Canada, 11-17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Hwang, J.; Lee, S.; Bae, Y.; Park, J. An energy and GPU-computation efficient backbone network for real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPR), Long Beach, California, USA, 16-20 June 2019; pp. 0–0. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Qin, H.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, Utah, USA, 18-22 June 2018; pp. 8759–8768. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, Hawaii, USA, 21-26 July 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, K.; Bai, S.; Xie, L.; Qi, H.; Huang, Q.; Tian, Q. Centernet: Keypoint triplets for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, South Korea, 27-30 October 2019; pp. 6569–6578. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, W.; Wu, L.; Chen, S.; Hu, X.; Li, J.; Tang, J.; Yang, J. Generalized focal loss: Learning qualified and distributed bounding boxes for dense object detection. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 21002–21012. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, W.; Hu, X.; Li, J.; Tang, J.; Yang, J. Generalized focal loss v2: Learning reliable localization quality estimation for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, Tennessee, USA, 16-22 June 2021; pp. 11632–11641. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Chi, C.; Yao, Y.; Lei, Z.; Li, S. Z. Bridging the gap between anchor-based and anchor-free detection via adaptive training sample selection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, Washington, USA, 14-19 June 2020; pp. 9759–9768. [Google Scholar]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Glasgow, UK, 23-28 August 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Jia, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L. Diag-IoU loss for object detection. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 33, 7671–7683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basalama, S.; Sohrabizadeh, A.; Wang, J.; Guo, L.; Cong, J. FlexCNN: An end-to-end framework for composing CNN accelerators on FPGA. ACM Trans. Reconfigurable Technol. Syst. 2023, 16, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, G.; Yang, X.; Zhang, T.; Zheng, J.; Xu, D.; Liu, Z.; Liu, M.; Yan, X. XVDPU: A High-Performance CNN Accelerator on the Versal Platform Powered by the AI Engine. ACM Trans. Reconfigurable Technol. Syst. 2024, 17, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wang, M.; Chu, X.; Wang, K.; He, L. Low-precision floating-point arithmetic for high-performance FPGA-based CNN acceleration. ACM Trans. Reconfigurable Technol. Syst. (TRETS) 2021, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Fan, X.; Cao, W.; Wang, L. SWM: A high-performance sparse-winograd matrix multiplication CNN accelerator. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. (VLSI) Syst. 2021, 29, 936–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NanoDet-Plus: Super fast and high accuracy lightweight anchor-free object detection model. Available online: https://github.com/RangiLyu/nanodet (accessed on 2021).

- Feng, C.; Zhong, Y.; Gao, Y.; Scott, M.; Huang, W. Tood: Task-aligned one-stage object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, Canada, 10-17 October 2021; pp. 3490–3499. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Zhu, L.; Chen, W.; Wang, W.; Gan, C.; Han, S. On-device training under 256kb memory. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS), New Orleans, USA, 28 November - 9 December 2022; pp. 22941–22954. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, B.; Yuan, H.; Lu, L.; Zhang, Y. Resource-constrained neural architecture search on edge devices. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zheng, P.; Xu, S.; Wu, X. Object detection with deep learning: A review. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2019, 30, 3212–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q. Efficientdet: Scalable and efficient object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, Washington, USA, 14-19 June 2020; pp. 10781–10790. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Detrs beat yolos on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 17-21 June 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.; Berg, A. SSD: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the 14th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Amsterdam, Netherlands, 10-16 October 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Girshick, R. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21-26 July 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Z.; Vasconcelos, N. Cascade R-CNN: Delving into high quality object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18-22 June 2018; pp. 6154–6162. [Google Scholar]

- Law, H.; Deng, J. CornerNet: Detecting objects as paired keypoints. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8-14 September 2018; pp. 734–750. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Zhuo, J.; Krahenbuhl, P. Bottom-up object detection by grouping extreme and center points. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 16-20 June 2019; pp. 850–859. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zheng, T.; Xu, G.; Yang, Z.; Liu, H.; Cai, D. Training-time-friendly network for real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), New York, NY, USA, 7-12 February 2020; pp. 11685–11692. [Google Scholar]

- Ghahremannezhad, H.; Shi, H.; Liu, C. Object detection in traffic videos: A survey. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 6780–6799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.; Su, Y.; Cao, X.; Li, H.; Liu, L. YOLOFM: An improved fire and smoke object detection algorithm based on YOLOv5n. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Shen, C.; Chen, H.; He, T. FCOS: Fully convolutional one-stage object detection. arXiv Prepr. arXiv:1904.01355 2019.

- Xu, C.; Wang, J.; Yang, W.; Yu, H.; Yu, L.; Xia, G. RFLA: Gaussian receptive field based label assignment for tiny object detection. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Tel-Aviv, Israel, 23-27 October 2022; pp. 526–543. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Lee, H. Probabilistic anchor assignment with IoU prediction for object detection. In Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Glasgow, UK, 23-28 August 2020; pp. 355–371. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Z.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Yoshie, O.; Sun, J. OTA: Optimal transport assignment for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 19-25 June 2021; pp. 303–312. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, F.; Li, Z.; Sun, J. YOLOX: Exceeding YOLO series in 2021. arXiv Prepr. arXiv:2107.08430 2021.

- Zhu, X.; Su, W.; Lu, L.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Dai, J. Deformable DETR: Deformable transformers for end-to-end object detection. arXiv Prepr. arXiv:2010.04159 2020.

- Pu, Y.; Liang, W.; Hao, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Hu, H.; Huang, G. Rank-DETR for high quality object detection. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, J.; Bouchard, M.; Laganiere, R. T-fftradnet: Object detection with Swin vision transformers from raw ADC radar signals. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 2-6 October 2023; pp. 4030–4039. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, C.; Kwong, S.; Ip, H. Dual Swin-transformer based mutual interactive network for RGB-D salient object detection. Neurocomputing 2023, 559, 126779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodla, N.; Singh, B.; Chellappa, R.; Davis, L. S. Soft-NMS–improving object detection with one line of code. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22-29 October 2017; pp. 5561–5569. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, P.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Ye, R.; Ren, D. Distance-IoU loss: Faster and better learning for bounding box regression. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), New York, NY, USA, 7-12 February 2020; pp. 12993–13000. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, P.; Ren, D.; Liu, W.; Ye, R.; Hu, Q.; Zuo, W. Enhancing geometric factors in model learning and inference for object detection and instance segmentation. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 52, 8574–8586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezatofighi, H.; Tsoi, N.; Gwak, J.; Sadeghian, A.; Reid, I.; Savarese, S. Generalized intersection over union: A metric and a loss for bounding box regression. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 16-20 June 2019; pp. 658–666. [Google Scholar]

- Neubeck, A.; Van, G.L. Efficient non-maximum suppression. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Hong Kong, 20-24 August 2006; pp. 850–855. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Pan, Q.; Gao, L.; Zhang, B. Improved non-maximum suppression for object detection using harmony search algorithm. Appl. Soft Comput. 2019, 81, 105478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Zheng, A.; Zhang, X.; Sun, J. Detection in crowded scenes: One proposal, multiple predictions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13-19 June 2020; pp. 12214–12223. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Huang, D.; Wang, Y. Adaptive NMS: Refining pedestrian detection in a crowd. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 16-20 June 2019; pp. 6459–6468. [Google Scholar]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Glasgow, UK, 23-28 August 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, P.; Zheng, M.; Wang, X.; Dai, J.; Li, H. Fast convergence of DETR with spatially modulated co-attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, Canada, 10-17 October 2021; pp. 3621–3630. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P.; Zhang, R.; Jiang, Y.; Kong, T.; Xu, C.; Zhan, W.; Tomizuka, M.; Li, L.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, C. Sparse R-CNN: End-to-end object detection with learnable proposals. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 19-25 June 2021; pp. 14454–14463. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, M.; Ouyang, P.; Yin, S.; Liu, L.; Wei, S. A fast and power-efficient hardware architecture for non-maximum suppression. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II: Express Briefs 2019, 66, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Derbyshire, H.; Sun, W.; Yue, J.; Shi, H.; Liu, Y. A sort-less FPGA-based non-maximum suppression accelerator using multi-thread computing and binary max engine for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Asian Solid-State Circuits Conference (A-SSCC), Busan, South Korea, 7-10 November 2021; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, T.; Yu, Z.; Raghuraman, A.; Udayan, S.; Lin, J.; Aly, M.M.S. Scalable hardware acceleration of non-maximum suppression. In Proceedings of the Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE), Grenoble, France, 21-25 March 2022; pp. 96–99. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.B.; Lee, S.S.; Park, J.; Jang, S.J. Standard greedy non maximum suppression optimization for efficient and high speed inference. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics-Asia (ICCE-Asia), Gangwon, South Korea, 1-3 November 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Anupreetham, A.; Ibrahim, M.; Hall, M.; Boutros, A.; Kuzhively, A.; Mohanty, A.; Nurvitadhi, E.; Betz, V.; Cao, Y.; Seo, J. End-to-end FPGA-based object detection using pipelined CNN and non-maximum suppression. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Field-Programmable Logic and Applications (FPL), Dresden, Germany, 30 August - 3 September 2021; pp. 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Liu, K.; Liu, W.; Li, S. Efficient FPGA-based Accelerator for Post-Processing in Object Detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Field Programmable Technology (ICFPT), Yokohama, Japan, December 11-14 2023; pp. 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lv, D.; Yu, X.; He, G. O3 NMS: An Out-Of-Order-Based Low-Latency Accelerator for Non-Maximum Suppression. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Monterey, California, USA, 21-25 May 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, K.; Li, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Kuo, H.W.; Lee, K.P.; Tang, K.T. An area-efficient accelerator for non-maximum suppression. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II: Express Briefs 2023, 70, 2251–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anupreetham, A.; Ibrahim, M.; Hall, M.; Boutros, A.; Kuzhively, A.; Mohanty, A.; Nurvitadhi, E.; Betz, V.; Cao, Y.; Seo, J. High Throughput FPGA-Based Object Detection via Algorithm-Hardware Co-Design. ACM Trans. Reconfigurable Technol. Syst. 2024, 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batcher, K. E. Sorting networks and their applications. In Proceedings of the Spring Joint Computer Conference, April 30 - May 2 1968; pp. 307–314. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.R.; Ho, C.C.; Chen, W.T.; Chen, P.Y. A Low-Cost Pipelined Architecture Based on a Hybrid Sorting Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I: Regul. Pap. 2023.

- Zhao, J.; Zeng, P.; Shen, G.; Chen, Q.; Guo, M. Hardware-software co-design enabling static and dynamic sparse attention mechanisms. IEEE Trans. Comput. Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Sun, W.; Zhou, A.; Wang, Z. Efficient N: M Sparse DNN Training Using Algorithm, Architecture, and Dataflow Co-Design. IEEE Trans. Comput. Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, W.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Z. Efficient hardware post processing of anchor-based object detection on FPGA. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Annual Symposium on VLSI (ISVLSI), Limassol, Cyprus, 6-8 July 2020; pp. 580–585. [Google Scholar]

| Standard IoU | Priority of Confidence Threshold Checking | Priority of Classification | Support for Training Post Process | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019-TCASII[57] | × | × | × | × |

| 2021-ASSCC[58] | × | × | × | × |

| 2021-FPL[61] | √ | √ | × | × |

| 2021-ICCE[60] | √ | √ | * | × |

| 2022-DATE[59] | × | √ | × | × |

| 2023-FPT[62] | √ | √ | × | × |

| 2023-ISCAS[63] | √ | √ | × | × |

| 2023-TCASII[64] | × | √ | × | × |

| 2024-TReTS[65] | √ | √ | * | × |

| Ours | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Sorter Type | Support for Full Sorting | Support for Top-K Sorting | |

|---|---|---|---|

| - | Bitonic Sorter | √ | √ |

| 2023-TCAD[69] | Insertion Sorter | × | √ |

| 2023-TCASI[67] | Bitonic Sorter + Insertion Sorter | √ | √ |

| 2024-TCAD[68] | Variant of Bitonic Sorters | × | √ |

| Ours | Bitonic Sorter + Sorter Tree | √ | √ |

| Sorter | Sorter Type | Cycle |

|---|---|---|

| Parallel Bubble Sorter | Bubble Sorter | 7, 7@32:1, 7@32:16 |

| 2023-TCAD[69] | Insertion Sorter | 261, 261@32:1, 261@32:16 |

| Bitonic Sorter | Bitonic Sorter | 21, 21@32:1, 21@32:16 |

| 2023-TCASI[67] | Bitonic Insertion Sorter | 106, 15@32:1. 106@32:16 |

| Ours | Hybrid Bitonic Sorter | 21, 15@32:1, 21@32:16 |

| 2023-TCAD[69] | Bitonic Sorter | 2023-TCASI[67] | Ours | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sorter Type | Insertion Sorter | Bitonic Sorter | Bitonic Insertion Sorter | Hybrid Bitonic Sorter |

| Time (ms) | 0.416@F | 0.252@F | 0.309@F | 0.248@F |

| 0.208@G | 0.184@G | 0.193@G | 0.182@G | |

| 0.206@Y | 0.186@Y | 0.193@Y | 0.183@Y | |

| 0.388@F-NMS | 0.255@F-NMS | 0.304@F-NMS | 0.253@F-NMS | |

| 0.220@G-NMS | 0.192@G-NMS | 0.202@G-NMS | 0.190@G-NMS | |

| √ | 0.210@Y-NMS | 0.188@Y-NMS | 0.196@Y-NMS | 0.186@Y-NMS |

| Power (W) | 3.028 | 2.228 | 3.740 | 2.321 |

| LUT | 204200 | 158329 | 351365 | 166417 |

| FF | 154203 | 135901 | 181732 | 136652 |

| 2023-TCASII[64] | 2024-TReTS[65] | Ours | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confidence Threshold Checking in Inference | √ | √ | √ |

| Box Center Position Checking in Training | √ | √ | √ |

| Classification Priority | × | * | √ |

| Time (ms) | 0.295@F | 0.272@F | 0.248@F (1.10x) |

| 0.217@G | 0.214@G | 0.182@G (1.18x) | |

| 0.209@Y | 0.212@Y | 0.187@Y (1.13x) | |

| 0.368@F-NMS | 0.287@F-NMS | 0.253@F-NMS (1.13x) | |

| 0.228@G-NMS | 0.226@G-NMS | 0.190@G-NMS (1.19x) | |

| 0.209@Y-NMS | 0.209@Y-NMS | 0.186@Y-NMS (1.12x) |

| 2020-ISVLSI[70] | 2021-ICCE[60] | 2022-DATE[59] | 2023-FPT[62] | Ours | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support Train | × | × | × | × | √ | |

| IoU Accuracy Expression | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Testing Mode | IP Simulation | Data From DDR | IP Simulation | IP Simulation | Data Fetched by DMA From DDR | IP Simulation |

| Frequency (MHz) | 100 | - | 400 | 150 | 200 | |

| Time (ms) | √ | √ | √ | √ | 0.248@F | 0.080@F |

| √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 0.182@G | 0.014@G |

| √ | 0.032@NMS | 1.91@NMS | 0.05@NMS | 0.014@NMS | 0.187@Y | 0.015@Y |

| √ | √ | 5.19@NMS | √ | √ | 0.253@F-NMS | 0.083@F-NMS |

| √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 0.190@G-NMS | 0.022@G-NMS |

| √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 0.186@Y-NMS | 0.017@Y-NMS |

| Box Number | √ | √ | √ | √ | 22000@F | |

| √ | 3000 | - | 1000 | 2880 | 8400@G | |

| √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 6300@Y | |

| Selected Boxes | 5 | 11/48 | 5 | 24 | 10 | |

| Platform | ZYNQ7-ZC706 | ZCU106 | Gensys2 | Virtex7 690T | ZCU102 | |

| LUT | 11139 | - | 14188 | 26404 | 166417 | |

| FF | 3009 | - | 2924 | 21127 | 136652 | |

| LUTRAM | - | - | 7504 | 2 | 0 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).