Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Bone Disorders

3. Emotional Stress

4. Arterial Hypertension

5. Relationship Between Emotional Stress and Bone Disorders

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferguson, M.; Slepian, M.; France, C.; Svendrovski, A.; Katz, J. Hypertensive Hypoalgesia in a Complex Chronic Disease Population. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, X.; Dai, Y.; Zhao, H. Comorbidity of Anxiety and Hypertension: Common Risk Factors and Potential Mechanisms. Int. J. Hypertens. 2023, 2023, 9619388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruill, T.M. Chronic Psychosocial Stress and Hypertension. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2010, 12, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

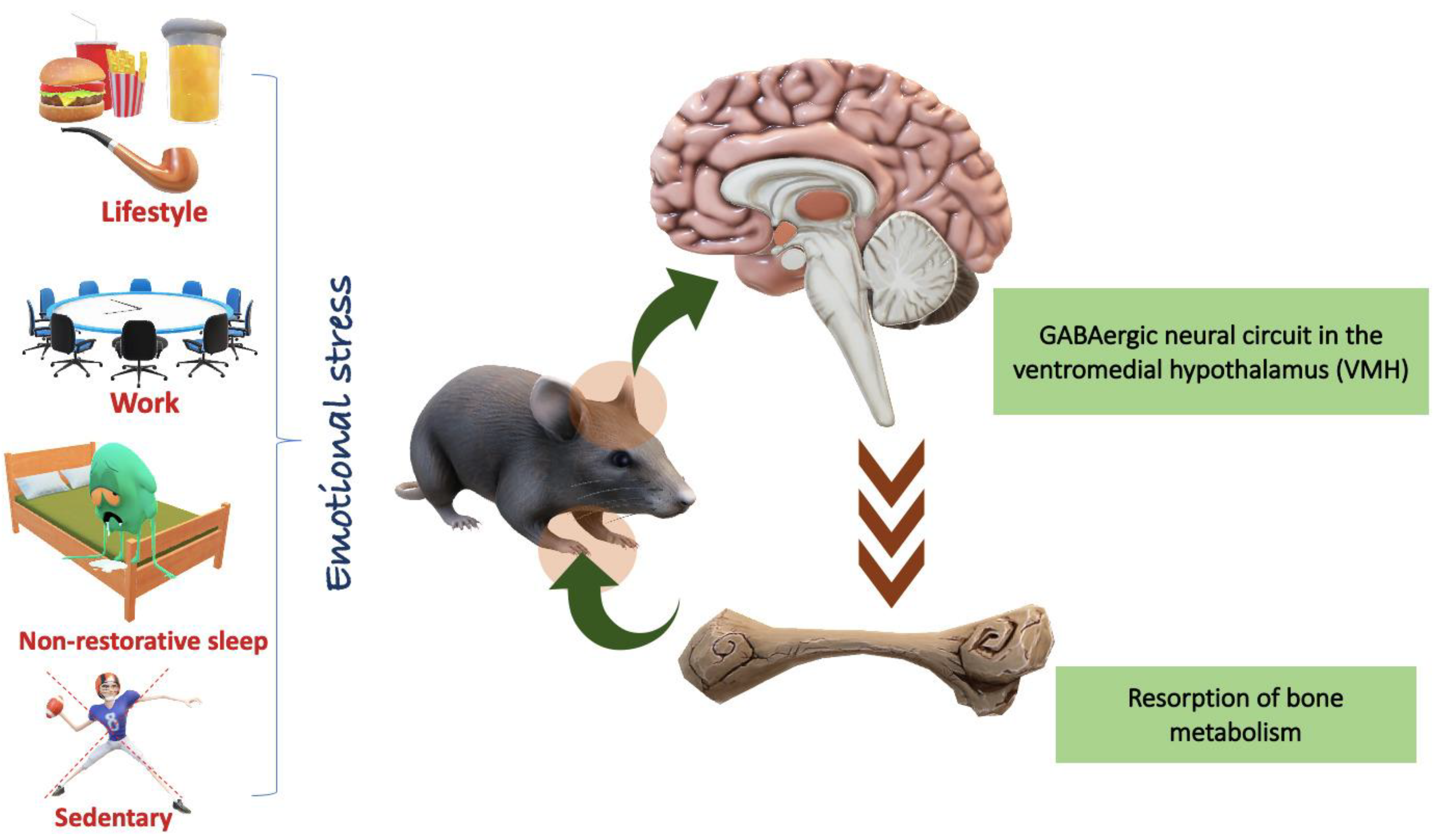

- Yang, F.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; et al. A GABAergic Neural Circuit in the Ventromedial Hypothalamus Mediates Chronic Stress-Induced Bone Loss. J. Clin. Invest. 2020, 130, 6539–6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyave-Atehortua, D.; Cordoba-Sanchez, V.; Zambrano-Cruz, R. Perseverative Cognition as a Mediator Between Personality Traits and Blood Pressure. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2023, 19, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaupp, J.; Hediger, K.; Wunderli, J.M.; Schäffer, B.; Tobias, S.; Kolecka, N.; Bauer, N. Psychophysiological Effects of Walking in Forests and Urban Built Environments with Disparate Road Traffic Noise Exposure: Study Protocol of a Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Przysucha, E.; Klarner, T.; Zerpa, C.; Maransinghe, M.K. Bimanual Coordination in Individuals Post-stroke: Constraints, Rehabilitation Approaches and Measures: Systematic Review. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2024, 17, 831–851. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bletsa, E.; et al. Exercise Effects on Left Ventricular Remodeling in Patients with Cardiometabolic Risk Factors. Life 2023, 13, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zhao, N.; Wang, J. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Toward Osteoporosis Among Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease in Zhejiang. Medicine (Baltimore) 2024, 103, e38153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolic, M.; Sharma, S.; Palmquist, A.; Shah, F.A. The Impact of Medication on Osseointegration and Implant Anchorage in Bone Determined Using Removal Torque—A Review. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Lary, C.W.; Hodonsky, C.J.; Peyser, P.A.; Bos, D.; van der Laan, S.W.; Miller, C.L.; Rivadeneira, F.; Kiel, D.P.; Kavousi, M.; Medina-Gomez, C. Association Between BMD and Coronary Artery Calcification: An Observational and Mendelian Randomization Study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2024, 39, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassis, A.; et al. Nutritional and Lifestyle Management of the Aging Journey: A Narrative Review. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1087505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadjidakis, D.J.; Androulakis, I.I. Bone Remodeling. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1092, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serim, T.M.; Amasya, G.; Eren-Böncü, T.; Şengel-Türk, C.T.; Özdemir, A.N. Electrospun Nanofibers: Building Blocks for the Repair of Bone Tissue. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2024, 15, 941–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bari, A.A.; Al Mamun, A. Current Advances in Regulation of Bone Homeostasis. FASEB BioAdvances 2020, 2, 668–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marahleh, A.; Kitaura, H.; Ohori, F.; Noguchi, T.; Mizoguchi, I. The Osteocyte and Its Osteoclastogenic Potential. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1121727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, N.; Sims, N.A. The Cells of Bone and Their Interactions. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2020, 262, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, M. Bone Tissue Regeneration: Biology, Strategies and Interface Studies. Prog. Biomater. 2019, 8, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofaro, F.D.; Costa, S.; Simone, M.L.; Quaglino, D.; Boraldi, F. Fibroblasts' Secretome from Calcified and Non-calcified Dermis in Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum Differently Contributes to Elastin Calcification. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, K.X.; Gao, X.; Liu, L.; He, W.G.; Jiang, Y.; Long, C.B.; Zhong, G.; Xu, Z.H.; Deng, Z.L.; He, B.C.; Hu, N. Leptin Attenuates the Osteogenic Induction Potential of BMP9 by Increasing β-Catenin Malonylation Modification via Sirt5 Down-Regulation. Aging (Albany NY) 2024, 16, 7870–7888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergatti, A.; Abate, V.; D'Elia, L.; De Filippo, G.; Piccinocchi, G.; Gennari, L.; Merlotti, D.; Galletti, F.; Strazzullo, P.; Rendina, D. Smoking Habits and Osteoporosis in Community-Dwelling Men Subjected to Dual-X-ray Absorptiometry: A Cross-Sectional Study. *J. Endocrinol. Invest.* 2024. Ahead of Print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudhud, L.; Rozmer, K.; Kecskés, A.; Pohóczky, K.; Bencze, N.; Buzás, K.; Szőke, É.; Helyes, Z. Transient Receptor Potential Ankyrin 1 Ion Channel Is Expressed in Osteosarcoma and Its Activation Reduces Viability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, S.; Nakayama, T. Recent Clinical Treatment and Basic Research on the Alveolar Bone. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Röper, L.; Fuchs, F.; Hanschen, M.; Failer, S.; Alageel, S.; Cong, X.; Dornseifer, U.; Schilling, A.F.; Machens, H.G.; Moog, P. Bone Regenerative Effect of Injectable Hypoxia Preconditioned Serum-Fibrin (HPS-F) in an Ex Vivo Bone Defect Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrousos, G.P. Stress and Disorders of the Stress System. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2009, 5, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, J.K.; Engert, V.; Valk, S.L.; Singer, T.; Puhlmann, L.M.C. Mapping Pathways to Neuronal Atrophy in Healthy, Mid-Aged Adults: From Chronic Stress to Systemic Inflammation to Neurodegeneration? Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2024, 38, 100781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarström, A.; Westerlund, H.; Janlert, U.; Virtanen, P.; Ziaei, S.; Östergren, P.O. How Do Labour Market Conditions Explain the Development of Mental Health Over the Life-Course? A Conceptual Integration of the Ecological Model with Life-Course Epidemiology in an Integrative Review of Results from the Northern Swedish Cohort. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Rinwa, P.; Kaur, G.; Machawal, L. Stress: Neurobiology, Consequences and Management. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2013, 5, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atrooz, F.; Alkadhi, K.A.; Salim, S. Understanding Stress: Insights from Rodent Models. Curr. Res. Neurobiol. 2021, 2, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, Z.R.; Abizaid, A. Stress Induced Obesity: Lessons from Rodent Models of Stress. Front. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, I.; Gellner, A.-K. Long-Term Effects of Chronic Stress Models in Adult Mice. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna) 2023, 130, 1133–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, E.; Hatanaka, T.; Iijima, T.; Kimura, M.; Katoh, A. The Effects of Corticotropin-Releasing Factor on Motor Learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, K.T.; Stefanescu, A.; He, J. The Global Epidemiology of Hypertension. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picariello, C.; Lazzeri, C.; Attanà, P.; Chiostri, M.; Gensini, G.F.; Valente, S. The Impact of Hypertension on Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. Int. J. Hypertens. 2011, 2011, 563657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, N.; Hassan, A.; Ghani, U.; Rahim, O.; Ghulam, M.; James, N.; Ashfaq, Z.; Ali, S.; Siddiqui, A. Age-Related Patterns of Symptoms and Risk Factors in Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS): A Study Based on Cardiology Patients' Records at Rehman Medical Institute, Peshawar. Cureus 2024, 16, e58426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, X.; Dai, Y.; Zhao, H. Comorbidity of Anxiety and Hypertension: Common Risk Factors and Potential Mechanisms. Int. J. Hypertens. 2023, 2023, 9619388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koszewicz, M.; Jaroch, J.; Brzecka, A.; Ejma, M.; Budrewicz, S.; Mikhaleva, L.M.; Muresanu, C.; Schield, P.; Somasundaram, S.G.; Kirkland, C.E.; Avila-Rodriguez, M.; Aliev, G. Dysbiosis Is One of the Risk Factors for Stroke and Cognitive Impairment and Potential Target for Treatment. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 164, 105277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabrazzo, M.; Cipolla, S.; Signoriello, S.; Camerlengo, A.; Calabrese, G.; Giordano, G.M.; Argenziano, G.; Galderisi, S. A Systematic Review on Shared Biological Mechanisms of Depression and Anxiety in Comorbidity with Psoriasis, Atopic Dermatitis, and Hidradenitis Suppurativa. Eur. Psychiatry 2021, 64, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, T.G. The Effects of Environmental and Lifestyle Factors on Blood Pressure and the Intermediary Role of the Sympathetic Nervous System. J. Hum. Hypertens. 1997, 11, S9–18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.S.; Egede, L.E. Differences in Medical Expenditures for Men and Women with Diabetes in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2008-2016. Womens Health Rep. (New Rochelle) 2020, 1, 345–353. [Google Scholar]

- Vetcher, A.A.; Zhukov, K.V.; Gasparyan, B.A.; Borovikov, P.I.; Karamian, A.S.; Rejepov, D.T.; Kuznetsova, M.N.; Shishonin, A.Y. Different Trajectories for Diabetes Mellitus Onset and Recovery According to the Centralized Aerobic-Anaerobic Energy Balance Compensation Theory. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Méndez, G.X.; Calderón, V.M.; Zuñiga-Pimentel, T.A.; Rivera-Cerecedo, C.V. Noninvasive Monitoring of Blood Pressure and Heart Rate during Estrous Cycle Phases in Normotensive Wistar-Kyoto and Spontaneously Hypertensive Female Rats. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2023, 62, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, K.R.; McDonald, L.T.; Jensen, N.R.; Sidles, S.J.; LaRue, A.C. Impacts of Psychological Stress on Osteoporosis: Clinical Implications and Treatment Interactions. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 200. [Google Scholar]

- Jethwa, J.T. Musculoskeletal and Psychological Rehabilitation. Indian J. Orthop. 2023, 57 (Suppl 1), 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coventry, P.A.; Meader, N.; Melton, H.; Temple, M.; Dale, H.; Wright, K.; Cloitre, M.; Karatzias, T.; Bisson, J.; Roberts, N.P.; Brown, J.V.E.; Barbui, C.; Churchill, R.; Lovell, K.; McMillan, D.; Gilbody, S. Psychological and pharmacological interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid mental health problems following complex traumatic events: Systematic review and component network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawrzyniak, A.; Balawender, K. Structural and Metabolic Changes in Bone. Animals 2022, 12, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idelevich, A.; Baron, R. Brain to Bone: What Is the Contribution of the Brain to Skeletal Homeostasis? Bone 2018, 115, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Qiao, W.; Wei, J.A.; Tao, Z.; Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Lin, M.; Ng, K.M.C.; Zhang, L.; Yeung, K.W.; Chow, B.K.C. Secretin-Dependent Signals in the Ventromedial Hypothalamus Regulate Energy Metabolism and Bone Homeostasis in Mice. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.J.; Lu, Y.C.; Lu, S.N.; Liang, F.W.; Chuang, H.Y. Association Between Osteoporosis and Adiposity Index Reveals Nonlinearity Among Postmenopausal Women and Linearity Among Men Aged Over 50 Years. *J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health* 2024. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.; Jiang, B.; Xing, W.; Sun, J.; Greenblatt, M.B.; Zou, W. Skeletal Stem Cells: Origins, Definitions, and Functions in Bone Development and Disease. Life Med. 2022, 1, 276–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xu, C.; Song, H.; Feng, X.; Ma, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, G.; Mu, C.; Tan, L.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Luo, Z.; Yang, C. Biomimetic Bone-Periosteum Scaffold for Spatiotemporal Regulated Innervated Bone Regeneration and Therapy of Osteosarcoma. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minoia, A.; et al. Bone Tissue and the Nervous System: What Do They Have in Common? Cells. 2022, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gisbert-Garzarán, M.; Gómez-Cerezo, M.N.; Vallet-Regí, M. Targeting Agents in Biomaterial-Mediated Bone Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, W.; Liu, R.W.; Makmur, A.; Low, X.Z.; Sng, W.J.; Tan, J.H.; Kumar, N.; Hallinan, J.T.P.D. Artificial Intelligence Applications for Osteoporosis Classification Using Computed Tomography. Bioengineering (Basel) 2023, 10, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fricke, H.P.; Hernandez, L.L. The Serotonergic System and Bone Metabolism During Pregnancy and Lactation and the Implications of SSRI Use on the Maternal-Offspring Dyad. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2023, 28, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, C.H.; Zheng, C.X.; Jin, Y.; Sui, B.D. Autonomic Neural Regulation in Mediating the Brain-Bone Axis: Mechanisms and Implications for Regeneration Under Psychological Stress. QJM 2024, 117, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indirli, R.; Lanzi, V.; Mantovani, G.; Arosio, M.; Ferrante, E. Bone Health in Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea: What the Endocrinologist Needs to Know. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 946695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Shao, J.; Gao, D.; Zhang, L.; Yang, F. Astrocytes in the Ventromedial Hypothalamus Involve Chronic Stress-Induced Anxiety and Bone Loss in Mice. Neural Plast. 2021, 2021, 7806370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.S.; Chin, K.Y. Potential Mechanisms Linking Psychological Stress to Bone Health. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 18, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; et al. A GABAergic Neural Circuit in the Ventromedial Hypothalamus Mediates Chronic Stress-Induced Bone Loss. J. Clin. Invest. 2020, 130, 6539–6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, E.; Knapstein, P.R.; Jahn, D.; Appelt, J.; Frosch, K.H.; Tsitsilonis, S.; Keller, J. Crosstalk of Brain and Bone—Clinical Observations and Their Molecular Bases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

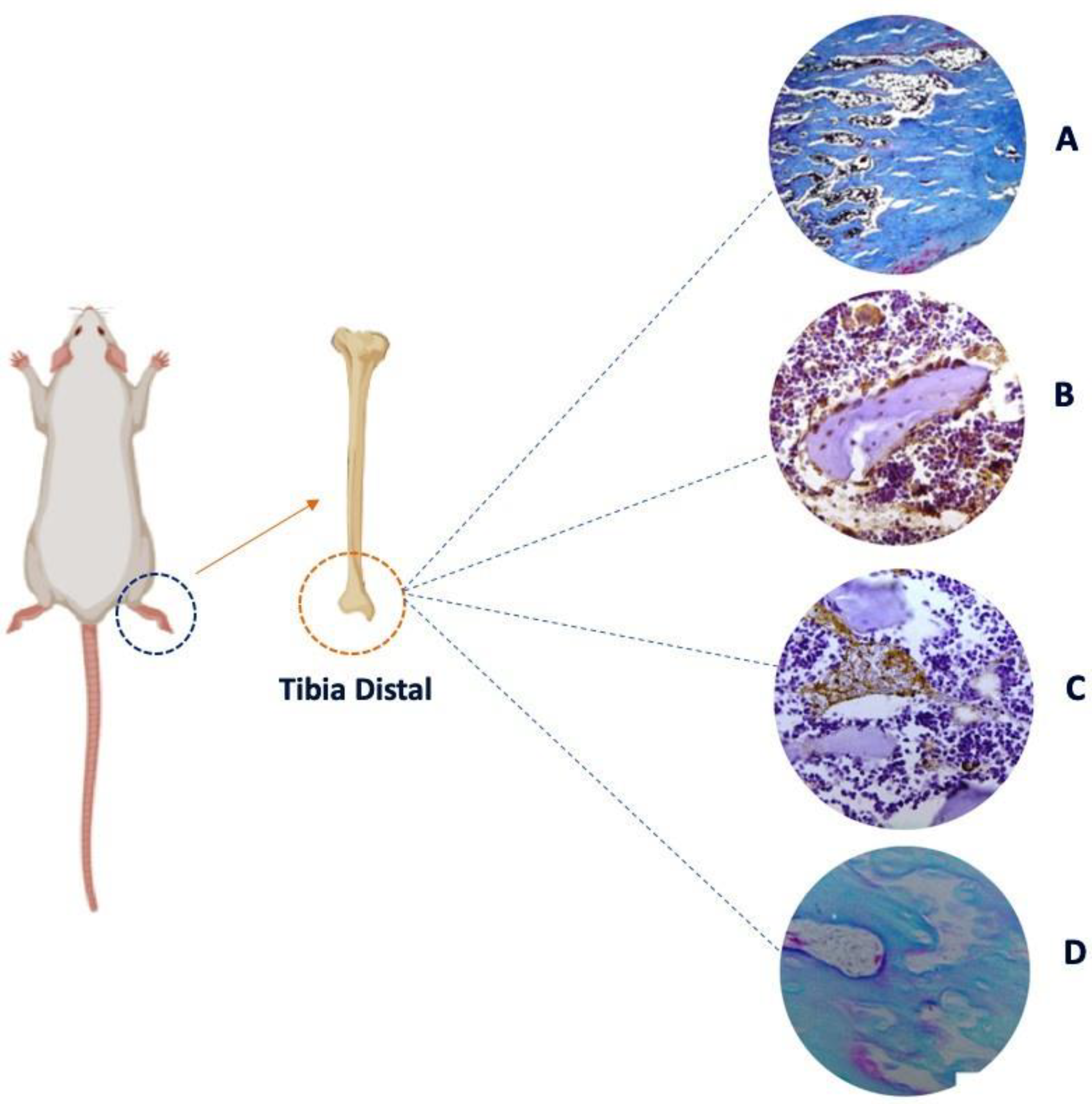

- Lopes Castro, M.M.; Nascimento, P.C.; Souza-Monteiro, D.; et al. Blood Oxidative Stress Modulates Alveolar Bone Loss in Chronically Stressed Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Gao, X.; Hou, Y. Effects of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Combined with Music Therapy on Pain, Anxiety, and Sleep Quality in Patients with Osteosarcoma. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2019, 41, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Deng, D.; et al. Aggravating Effects of Psychological Stress on Ligature-Induced Periodontitis via the Involvement of Local Oxidative Damage and NF-κB Activation. Mediators Inflamm. 2022, 2022, 6447056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, E.S.B.; Farias, L.C.; Silveira, L.H.; Jesus, C.Í.; Rocha, R.G.D.; Ramos, G.V.; Magalhães, H.T.A.T.; Brito-Júnior, M.; Santos, S.H.S.; Jham, B.C.; et al. Conditioned Fear Stress Increases Bone Resorption in Apical Periodontitis Lesions in Wistar Male Rats. Arch. Oral Biol. 2019, 97, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follis, S.L.; Bea, J.; Klimentidis, Y.; et al. Psychosocial stress and bone loss among postmenopausal women: results from the Women's Health Initiative. J Epidemiol Community Health 2019, 73, 888–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haffner-Luntzer, M.; Foertsch, S.; Fischer, V.; Prystaz, K.; Tschaffon, M.; Mödinger, Y.; Bahney, C.S.; Marcucio, R.S.; Miclau, T.; Ignatius, A.; Reber, S.O. Chronic Psychosocial Stress Compromises the Immune Response and Endochondral Ossification During Bone Fracture Healing via β-AR Signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2019, 116, 8615–8622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foertsch, S.; Haffner-Luntzer, M.; Kroner, J.; Gross, F.; Kaiser, K.; Erber, M.; Reber, S.O.; Ignatius, A. Chronic Psychosocial Stress Disturbs Long-Bone Growth in Adolescent Mice. Dis. Model. Mech. 2017, 10, 1399–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okbay Güneş, A.; Alikaşifoğlu, M.; Şen Demirdöğen, E.; Erginöz, E.; Demir, T.; Kucur, M.; Ercan, O. The Relationship of Disordered Eating Attitudes with Stress Level, Bone Turnover Markers, and Bone Mineral Density in Obese Adolescents. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2017, 9, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henneicke, H.; Li, J.; Kim, S.; Gasparini, S.J.; Seibel, M.J.; Zhou, H. Chronic Mild Stress Causes Bone Loss via an Osteoblast-Specific Glucocorticoid-Dependent Mechanism. Endocrinology 2017, 158, 1939–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumano, H. Clin Calcium 2005, 15, 1544–1547.

- Azuma, K.; Adachi, Y.; Hayashi, H.; Kubo, K.Y. Chronic Psychological Stress as a Risk Factor of Osteoporosis. J. UOEH 2015, 37, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, K.; Furuzawa, M.; Fujiwara, S.; Yamada, K.; Kubo, K.Y. Effects of Active Mastication on Chronic Stress-Induced Bone Loss in Mice. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 12, 952–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahrendorf, M.; Swirski, F.K. Lifestyle Effects on Hematopoiesis and Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 884–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erez, H.B.; Weller, A.; Vaisman, N.; Kreitler, S. The Relationship of Depression, Anxiety and Stress with Low Bone Mineral Density in Post-Menopausal Women. Arch. Osteoporos. 2012, 7, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, X.; Li, Q.; Wu, S.; Sun, J.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Y.J. Psychological Stress Alters the Ultrastructure and Increases IL-1β and TNF-α in Mandibular Condylar Cartilage. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2012, 45, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seferos, N.; Kotsiou, A.; Petsaros, S.; Rallis, G.; Tesseromatis, C. Mandibular Bone Density and Calcium Content Affected by Different Kinds of Stress in Mice. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2010, 10, 231–236. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson-Buckendahl, P.; Pohorecky, L.A.; Kubovcakova, L.; Krizanova, O.; Martin, R.B.; Martinez, D.A.; Kvetnanský, R. Ethanol and Stress Activate Catech.

- García-Alfaro, P.; García, S.; Rodriguez, I.; Pascual, M.A.; Pérez-López, F.R. Association of Endogenous Hormones and Bone Mineral Density in Postmenopausal Women. J Midlife Health 2023, 14, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Luo, X.; Lu, Z.; Chen, N. Association of Midnight Cortisol Level with Bone Mineral Density in Chinese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Cross-Sectional Study. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2024, 17, 2943–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, C. Enhancing Mental Health, Well-Being and Active Lifestyles of University Students by Means of Physical Activity and Exercise Research Programs. Front Public Health 2022, 10, 849093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedenreich, C.M.; Ryder-Burbidge, C.; McNeil, J. Physical activity, obesity and sedentary behavior in cancer etiology: epidemiologic evidence and biologic mechanisms. Mol Oncol 2021, 15, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.M.; Huang, P.; Chen, R.; Wang, Y.C. The relationship between physical activity and mental health of middle school students: the chain mediating role of negative emotions and self-efficacy. Front Psychol 2024, 15, 1415448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calcagni, E.; Elenkov, I. Stress system activity, innate and T helper cytokines, and susceptibility to immune-related diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2006, 1069, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coletti, C.; Acosta, G.F.; Keslacy, S.; Coletti, D. Exercise-mediated reinnervation of skeletal muscle in elderly people: An update. Eur J Transl Myol 2022, 32, 10416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Xu, S.; Zhang, H. Regulation of bone health through physical exercise: Mechanisms and types. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022, 13, 1029475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; et al. Tobacco toxins induce osteoporosis through ferroptosis. Redox Biol 2023, 67, 102922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Maldonado, E.; Gallego-Narbón, A.; Zapatera, B.; Alcorta, A.; Martínez-Suárez, M.; Vaquero, M.P. Bone Remodelling, Vitamin D Status, and Lifestyle Factors in Spanish Vegans, Lacto-Ovo Vegetarians, and Omnivores. Nutrients 2024, 16, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hezaimi, K.; Rotstein, I.; Katz, J.; Nevins, M.; Nevins, M. Effect of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (Paroxetine) on Newly Formed Bone Volume: Real-Time In Vivo Micro-computed Tomographic Analysis. J Endod 2023, 49, 1495–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkhenany, H.; AlOkda, A.; El-Badawy, A.; El-Badri, N. Tissue regeneration: Impact of sleep on stem cell regenerative capacity. Life Sci. 2018, 214, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Article title | Kind study | Authors | Year | Stress | Time | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomic neural regulation in mediating the brain-bone axis: mechanisms and implications for regeneration under psychological stress |

Review |

Ma, C et al. [56] |

2024 |

X |

X |

The autonomic neural basis of psychological stress-induced bone loss |

| Bone health in functional hypothalamic amenorrhea: What the endocrinologist needs to know |

Review |

Indirli, Rita et al. [57] |

2022 |

X |

X |

Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea causes stress and bone is severely affected |

| Astrocytes in the Ventromedial Hypothalamus Involve Chronic Stress-Induced Anxiety and Bone Loss in Mice | Experimental | Liu, Yunhui et al. [58] | 2021 | Chronic | 8 weeks | Glial-neuron microcircuit in VMH nuclei that mediates anxiety and bone loss induced by chronic stress |

| Potential mechanisms linking psychological stress to bone health | Review | Ng, Jia-Sheng, and Kok-Yong Chin [59] | 2021 | Chronic | X | Chronic psychological stress should be recognised as a risk factor of osteoporosis |

| GABAergic neural circuit in the ventromedial hypothalamus mediates chronic stress-induced bone loss | Experimental | Yang, Fan et al. [60] | 2020 | Chronic | 8 weeks | Chronic stress in crewmembers resulted in decreased bone density |

| Crosstalk of Brain and Bone—Clinical Observations and Their Molecular Bases | Review | Otto, Ellen et al. [61] | 2020 | X | X | The nervous system tightly modulates bone metabolism and regeneration |

| Blood Oxidative Stress Modulates Alveolar Bone Loss in Chronically Stressed Rats | Experimental | Lopes Castro, Micaele Maria et al. [62] | 2020 | Chronic | 30 days | Chronic stress induces oxidative blood imbalance, which can potentiate or generate morphological, structural and metabolic damage to the alveolar bone |

| Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction combined with music therapy on pain, anxiety, and sleep quality in patients with osteosarcoma | Clinical | Liu, Haizhi et al. [63] | 2019 | Chronic | 8 weeks | Music therapy significantly alleviated clinical symptoms in patients with osteosarcoma |

| Aggravating Effects of Psychological Stress on Ligature-Induced Periodontitis via the Involvement of Local Oxidative Damage and NF- κ B Activation | Experimental | Li, Qiang et al. [64] | 2019 | Chronic | 4 weeks | Psychological stress aggravates inflammation in periodontitis tissues and leads to further activation of the nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) signaling pathway |

| Conditioned fear stress increases bone resorption in apical periodontitislesions in Wistar male rats | Experimental | Gomes, Emisael Stênio Batista et al. [65] | 2019 | Chronic | 56 days | Stress caused by fear modifies a periapical lesion, increasing the size of bone loss and increasing the number of inflammatory cells |

| Psychosocial stress and bone loss among postmenopausal women: results from the Women's Health Initiative | Clinical | Follis, Shawna L et al. [66] | 2019 | Chronic | 6 years | High social stress was associated with decreased bone mineral density |

| Chronic psychosocial stress compromises the immune response and endochondral ossification during bone fracture healing via β-AR signaling | Experimental | Haffner-Luntzer, Melanie et al. [67] | 2019 | Chronic | 19 days | Chronic psychosocial stress leads to an imbalanced immune response after fracture via β-AR signaling |

| Chronic psychosocial stress disturbs long-bone growth in adolescent mice | Experimental | Foertsch, Sandra et al. [68] | 2017 | Chronic | 19 days | Chronic psychosocial stress negatively impacts endochondral ossification in the growth plate, affecting both longitudinal and appositional bone growth |

| The Relationship of Disordered Eating Attitudes with Stress Level, Bone Turnover Markers, and Bone Mineral Density in Obese Adolescents | Clinical | Okbay Güneş, Aslı et al. [69] | 2017 | X | X | Effect of stress caused by disordered eating habits harms bone remodeling |

| Chronic Mild Stress Causes Bone Loss via an Osteoblast-Specific Glucocorticoid-Dependent Mechanism | Experimental | Henneicke, Holger et al. [70] | 2017 | Chronic | 4 weeks | Bone loss during chronic stress is mediated through increased glucocorticoid signaling in osteoblasts (and osteocytes) and subsequent activation of osteoclasts |

| Osteoporosis and stress | Review | Kumano, Hiroaki. [71] | 2015 | X | X | Osteoporosis causes anxiety, depression, loss of social roles and social isolation, which leads to stress. |

| Chronic Psychological Stress as a Risk Factor of Osteoporosis | Review | Azuma, Kagaku et al. [72] | 2015 | X | X | Chronic stress activates the HPA axis and increases inflammatory cytokines, eventually leading to bone loss, inhibiting bone formation and stimulating bone resorption. |

| Effects of Active Mastication on Chronic Stress-Induced Bone Loss in Mice | Clinical | Azuma, Kagaku et al. [73] | 2015 | Chronic | 4 weeks | The stress group showed an increase in serum corticosterone levels and increased bone resorption |

| Lifestyle effects on hematopoiesis and atherosclerosis | Review | Nahrendorf, Matthias, and Filip K Swirski. [74] | 2015 | Chronic | X | Lifestyle (stress) changes the number of macrophages, diverting bone marrow production to the periphery |

| The relationship of depression, anxiety and stress with low bone mineral density in post-menopausal women | Clinical | Erez, Hany Burstein et al. [75] | 2012 | X | X | Supporting evidence for the existence of associations between mood variables and decreased bone |

| Psychological stress alters the ultrastructure and increases IL-1β and TNF-α in mandibular condylar cartilage | Experimental | Lv, Xin et al. [76] | 2012 | Chronic | 1,3 nad 5 weeks | Psychological stress increased plasma hormone levels and indicated increased expression of IL-1β and TNF-α in the TMJ |

| Mandibular bone density and calcium content affected by different kind of stress in mice | Experimental | Seferos, N et al. [77] | 2010 | Chronic | 137 days | The calcium content of the mandible and the ratio between calcium content and mandible volume was decreased |

| Ethanol and stress activate catecholamine synthesis in the adrenal: effects on bone | Experimental | Patterson-Buckendahl, Patricia et al. [78] | 2008 | Chronic | 6 weeks | Osteocalcin levels were reduced indicating inhibition of bone formation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).