1. Introduction

The use of physiologically-based modeling and simulation as a tool in pharmaceutical product development has been rising in recent years, especially after the publications of the following guidelines:

Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Analyses - format and content [

1], and

The Use of Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Analyses - Biopharmaceutics Applications for Oral Drug Product Development, Manufacturing Changes, and Controls Guidance for Industry [

2], both from the FDA, and

European Medicines Agency Guideline on the Reporting of Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling and Simulation [

3] from EMA. These materials provide guidelines and recommendations for the processes of implementing the PBPK model and regulatory submission. As such, many companies have invested in this type of approach to rationalize the development process by reducing financial, human, and material resources. As an example of process optimization, the definition of “safe space” must be cited, as it allows a more accurate understanding of the link between critical quality attributes and clinical performance.

To build a PBPK model, it is essential to have knowledge about all the factors involved in the drug’s absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination processes. Also, information about the population sample submitted to the study, such as age, gender, body mass and food effect, is needed. In addition to the PBPK model, compound’s information, such as physicochemical properties, particle size, formulation information and dissolution data, are linked to the model, becoming more detailed, to achieve mechanistic understanding as a Physiologically Based Biopharmaceutics Model (PBBM). The in vitro, in vivo and in silico information can be obtained experimentally or in literature, which contributes to the model’s complexity and predictivity [

4,

5,

6].

All this data listed is necessary because PBPK models - mathematical models - comprise the anatomy and physiology of the human body; in particular, organ size and volume, blood flow, transporters, enzymes, drug’s behavior according to its physicochemical properties. Thus, with this highly integrated system, the effects that occur in each organ influence the others [

7]. With this in view, the selection of information is essential, and the performance of the predictive model shall be verified by comparing simulated with observed data, adopting adequate statistical tools and previously established acceptance criteria [

3].

The association between dissolution testing, virtual bioequivalence study (VBE) and PBPK modeling are parts that make up the physiologically based biopharmaceutics modeling (PBBM) [

8]. PBBM integrates physiology characteristics of the subjects as a PBPK model, with drug and formulation performance data, to gain knowledge about biopredictive or clinically relevant dissolution methods and drug absorption [

5,

9].

Dissolution methods with clinically relevant specifications can be used to predict the influence of critical material attributes (CMA) and formulation variables as granule size distribution and tablet strength variation, for example, due to manufacturing process and post-approval changes, during the life cycle of the product, on its in vivo performance [

10]. In the other hand, biopredictive dissolution methods are those that can be linked to the in vivo performance of the drug product, which can also be evaluated using the PBBM approach [

11].

Rivaroxaban is a drug that intervenes in the process of clot formation in blood vessels, either preventing their formation in the veins after orthopedic surgery or treating deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, acute coronary syndrome, as well as prevention cerebrovascular accident (CVA), by inhibiting free Factor Xa in the blood, which would bound to the clot and in the prothrombinase complex [

12,

13].

Rivaroxaban presents linear pharmacokinetics in doses between 2.5 mg and 10 mg in fasted state, at doses of 15 and 20 mg there is a decrease in the bioavailability, but not proportional to dose (about 66% of the dose is absorbed), demonstrating that drug’s absorption is dose dependent and incomplete. It can be explained by its low solubility, which becomes significantly committed to the dose increasing [

14]. In the fed state, bioavailability is greater than 80% and presents linear pharmacokinetics for all dosages, in this sense, it’s recommended that the doses of 15 mg and 20 mg should be taken with food [

13,

15].

Rivaroxaban presents high permeability and is metabolized by the enzymes CYP3A4 and CYP2J2 by an oxidative process in the liver. Also, it undergoes uptake by the influx transporter, OAT3, in the kidneys, a process in which P-gp glycoprotein has a role too [

16,

17].

Being a low solubility and high permeability, class II of the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS), the dissolution of this drug is its limiting step for absorption. Given that, the drug's bioavailability is ruled by its in vivo dissolution. It means that having robust in vitro method to predict in vivo dissolution will contribute to the research, development, and quality control of rivaroxaban tablets. Thus, obtaining biopredictive dissolution test specifications can help pharmaceutical companies to gain insights about the in vivo performance of the drug product.

In this study, it was aimed to use a PBBM approach to set a biopredictive dissolution method for rivaroxaban tablets. For this purpose, a PBPK model was built and validated, and different dissolution test conditions were used as inputs in GastroPlus® software to assess their influence on the rivaroxaban absorption process. Virtual bioequivalence studies were run to evaluate the biopredictive power of the dissolution test conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The drug used was rivaroxaban 99.7% of purity (Zhejiang Supor Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd., China), kindly provided by a Brazilian pharmaceutical company. Samples of rivaroxaban 20 mg tablets, Xarelto®, (Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Leverkusen, Germany) were purchased in the local market. Buffer solutions used for dissolution testing were prepared according to the United States Pharmacopeia (USP). Analytical grade anhydrous monobasic sodium phosphate, glacial acetic acid, sodium acetate, hydrochloric acid (HCl) 37%, sodium hydroxide for analysis (JT Baker, Pennsylvania, USA), sodium dodecyl sulfate (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), acetonitrile (JT Baker, Pennsylvania, USA) and purified water were also used.

2.2. Solubility Determination

Rivaroxaban’s solubility was experimentally determined using the shake-flask method, where excess amount of the drug was added in solutions within the physiological pH range (0.1 M HCl solution; 0.05 M acetate buffer solution pH 4.5 and 0.05 M phosphate buffer solution pH 6.8), and solutions containing 0.05 M acetate buffer pH 4.5 with 0.1%, 0.2% and 0.4% of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS).

The solutions were kept under agitation of 150 rpm, at 37 ± 0.5 °C in an orbital shaking equipment Tecnal model T420 (São Paulo, Brazil) for 72 hours. After that, aliquots were collected, centrifuged, and 1 mL of the supernatant was diluted into a 10 mL volumetric flask containing purified water and acetonitrile (1:1). The absorbance of each solution was evaluated using an analytical curve in each pH, at a wavelength of 248 nm [

18].

Dose/solubility ratio was calculated by dividing the highest dose (20 mg) by its experimental solubility in all tested solutions.

2.3. FDA Dissolution Method

The reference drug product Xarelto® 20 mg (tablet) was submitted to the dissolution test under the conditions recommended by the FDA [

19]: apparatus 2 (paddle) at 75 rpm, 900 mL of acetate buffer solution pH 4.5 containing 0.4% of sodium dodecyl sulfate at 37 ± 0.5°C. The test was conducted in triplicate, using the Hanson Vision Elite 8 Dissolution Equipment (Teledyne Hanson, FL, USA). For this purpose, aliquots containing 5 mL were manually withdrawn from each dissolution vessel at time intervals of 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, and 60 minutes, and filtered using polyethylene 45 µm pore size dissolution filter. The amount of rivaroxaban dissolved was quantified using the same spectrophotometric method described for the solubility determination.

2.4. Development of the Biopredictive Dissolution Method

Tablets (n = 3) of the reference drug product Xarelto® 20 mg were submitted to different dissolution test conditions, as shown in

Table 1. The dissolution media used was acetate buffer solution pH 4.5 and the surfactant used was sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS).

2.5. Dissolution Efficiency Evaluation

The dissolution profiles obtained according to the test conditions presented in

Table 1, were evaluated regarding their dissolution efficiency (DE). DE values were calculated using the Microsoft Excel add-in program DDSolver.

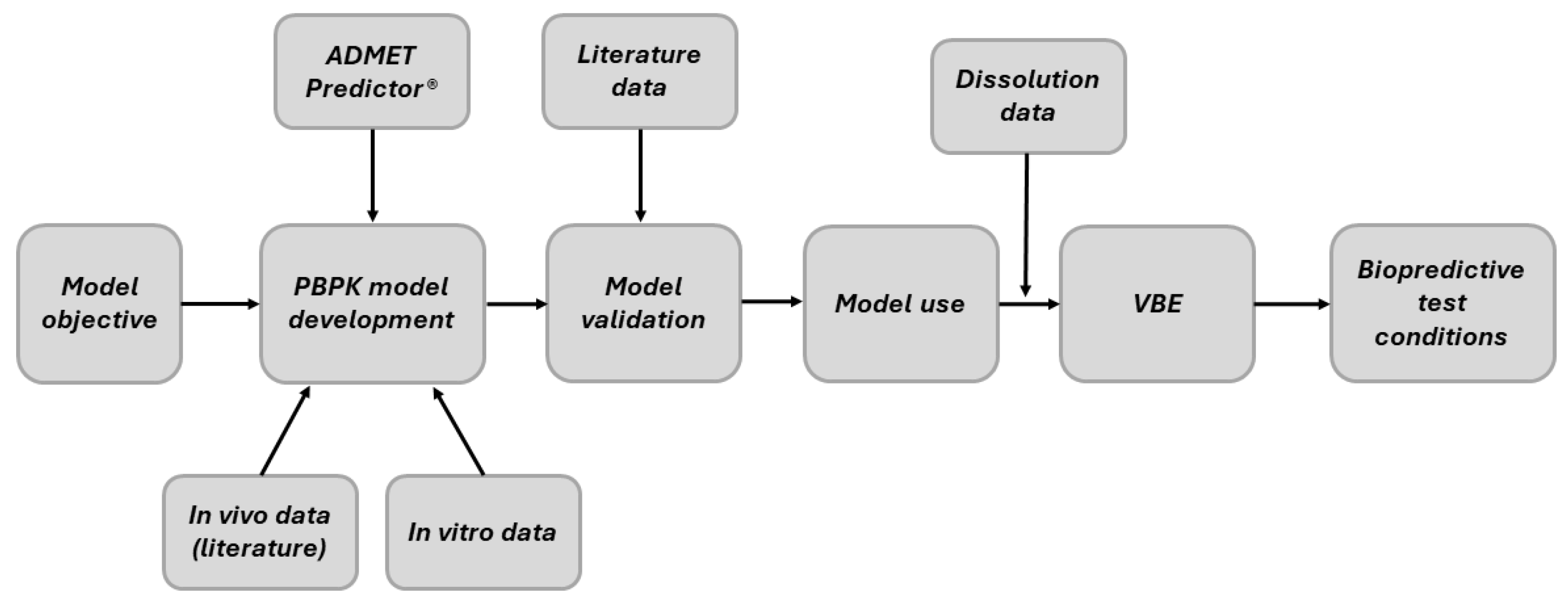

2.6. PBBM Development, Validation and Use

A PBPK model for rivaroxaban was developed considering PBBM, validated and used to simulate plasma concentration-time curves of rivaroxaban tablets using the dissolution data as inputs. Obtained output data were used to perform virtual bioequivalence (VBE) studies. With these, it was aimed to evaluate the biopredictive performance of the dissolution test conditions (

Table 1). The steps are illustrated in the workflow below (

Figure 1).

2.6.1. PBPK Model Development

A PBPK model for rivaroxaban was built using GastroPlus® software version 9.8 (Simulations Plus Inc., Lancaster, CA, USA). Physicochemical and biopharmaceutical parameters calculated by the ADMET Predictor® module of GastroPlus®, and obtained from the literature, as well as experimental data, detailed in

Table 2, were firstly inserted in the software as input data.

In sequence, the plasma concentration-time curves for oral administration of Xarelto® tablets, containing 20 mg of rivaroxaban, reported by Kubitza et al. [

14], were used to set up the PBPK model. Kubitza et al. [

14] performed the in vivo study with ten healthy caucasian men, aged between 18 and 45 years, with body mass index (BMI) from 18 to 32 Kg/m

2, under fasting and high fat dietary fed conditions.

The PBPK model was setup considering the physiology of a healthy 33-year-old man, with 80.8 kg of body weight and 24.4 kg/m2 of body mass index (BMI). The partition coefficients between tissues and blood plasma (Kp) and fraction unbound to tissues (Fut) were calculated using the Poulin method, which was also considered for both perfusion and permeability limited tissues. Renal clearance was calculated by the product between glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and Fup while hepatic clearance was obtained by ADMET Predictor®.

To achieve adequate predictions under the fasting condition, the plasma concentration-time curve of Xarelto® 20 mg, described by Kubitza et al. [

14], was used to set the ASF (Absorption Scale Factors).

Then, fed state simulations were performed using “Human - Physiological - Fed; Opt logD Model SA/V 6.1” setting in GastroPlus®, considering the high calorie (900 Kcal) and high fat (55%) meal option.

For both fasted and fed PBPK models, simulations were performed without the use of in vitro dissolution profiles, selecting as dosage form immediate-release tablets (IR:Tablet) and Johnson dissolution model, with simulation length of 24 hours, comparing the obtained results with those described by Kubitza et al. [

14].

2.6.2. PBPK Model Validation

In order to evaluate the PBPK model, simulations were run in both fasted and fed states. In sequence, the predicted PK parameters maximum plasma concentration (C

max) and area under the curve (AUC

0-t) were compared to those described by Kubitza et al. [

23,

24], and Stampfuss et al. [

15]. These parameters were obtained by running simulations without the use of in vitro dissolution profiles as input data, selecting the IR:Tablet as the dosage form.

A second validation step was performed to validate the PBBM approach, by linking experimental dissolution profiles to the PBPK model. The experimental dissolution profile of the reference drug product Xarelto® 20 mg tablets, obtained by applying the following method recommended by the FDA [

19], (apparatus 2 at 75 rpm and 900 ml of acetate buffer solution pH 4.5, containing 0.4% of SDS), was used as input data in the software. A Weibull function was fitted to the dissolution profile and the dosage form CRU: Dispersed was selected, which allowed the software to consider the release of undissolved particles of the drug according to the dissolution profile, which than dissolve according to the Johnson’s dissolution model in GastroPlus®. The simulations were performed in both fasted and fed states, and the values of the predicted PK parameters were compared to data from the literature.

2.6.3. Evaluation of Model Predictability

Aiming to evaluate the robustness of the model, predicted/observed ratio (P/O) and success criteria (SC) were used to compare the simulated PK parameters, under fasted and fed conditions, for Xarelto® 20 mg with the observed ones.

P/O values were considered acceptable when they were within the 0.8-1.25 range [

25]. SC formula considers sample size (N) and intra-individual variation (CV%) of the observed data to establish the confidence interval (CI), in which the geometric mean of predicted C

max and AUC

0-t must not exceed the lower and upper limits of the P/O ratio, as previously described by Abduljalil et al [

26].

2.6.4. Model Use

After PBPK model validation, the dissolution profiles experimentally obtained according to different dissolution test conditions (

Table 1), were added to the software in order to assess which dissolution test condition would be more biopredictive. The simulations were run in GastroPlus®, in both fasted and fed states, with CRU: Dispersed selected as the dosage form and a Weibull function fitted to each dissolution profile. The PK data C

max and AUC

0-t, generated as outputs from the predicted plasma concentration-time curves, were compared with the PK parameters obtained using the dissolution profile described in the FDA for Xarelto® 20 mg tablets, for both fasted and fed states, by running virtual bioequivalence (VBE) studies.

2.7. Virtual Bioequivalence Studies

VBE studies were performed to test the biopredictive power of the dissolution methods (

Table 1).

The population simulator in GastroPlus® was used to run VBE studies using the CRU: Dispersed as the dosage form and Weibull function fitted to each dissolution profile, in comparison to the predicted plasma concentration-time curve of the Xarelto® 20 mg tablets, obtained using the experimental dissolution profile using the FDA dissolution method as previously described.

The virtual crossover trials, randomized from the normal distribution, logarithmic scale, were performed considering a population of 48 healthy male Caucasian subjects, with body weight between 65 and 95 kg and BMI of 19 to 29 kg/m

2. The test conditions were considered bioequivalent if the 90% confidence intervals (CI) the geometric mean test/reference for C

max and AUC

0-t ratios were within the bioequivalence limits of 80 and 125% [

27,

28].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Solubility Determination

According to the results exhibited on

Table 3, rivaroxaban present low and constant solubility value in HCl 0.1 M, acetate buffer pH 4.5, and phosphate buffer pH 6.8 solutions. Dose/solubility (D/S) ratio is used to calculate the volume of dissolution media required to dissolve the dose completely. According to the Biopharmaceutics Classification System, a drug is considered highly soluble when the D/S ratio is ≤ 250 mL in the physiological pH range [

25]. Very high values (> 3,000 mL) of D/S ratio were found for the solutions, which confirms its low solubility according to the BCS.

The results of the solubility of the drug in 0.05 M acetate buffer pH 4.5 containing different concentrations of the surfactant SDS are also presented in

Table 3.

The low and constant solubility of rivaroxaban in the physiologically pH range (

Table 3) is in agreement with its high pKa value (10.87), being on its unionized form at pH below its pKa. It is well-known that, for BCS class II drugs, dissolution is the rate-limiting step for absorption. For better absorption, it is recommended the administration of rivaroxaban at the higher dose strength (20 mg) with food. Due to its low solubility, the increase of bile salt concentration in the fed condition can help to solubilize the drug, which was already demonstrated by Kushwah et al. [

29]. The authors evaluated the solubility of rivaroxaban in biorelevant dissolution media at different pH conditions and found higher solubility in the fed state than in fasted condition.

Since the recommended dissolution method by the FDA for rivaroxaban tablets is acetate buffer pH 4.5 + 0.4% SDS, this solubility medium and two other SDS concentrations (0.1% and 0.2%) were also tested. The results (

Table 3) show a high increase in drug solubility by adding SDS to the dissolution medium. As a surfactant, SDS increases the wettability of the drug particles, helping to solubilize the drug. The solubilization process depends on the critical micelle concentration (CMC), in other words, as the amount of surfactant increases, the solubility increases. The amount of SDS used in the FDA dissolution method (0.4%) corresponds to 0.01387M, a value 1.73 times higher than the CMC of the SDS (0.008 M), which can explain the high solubility value of drug at this condition.

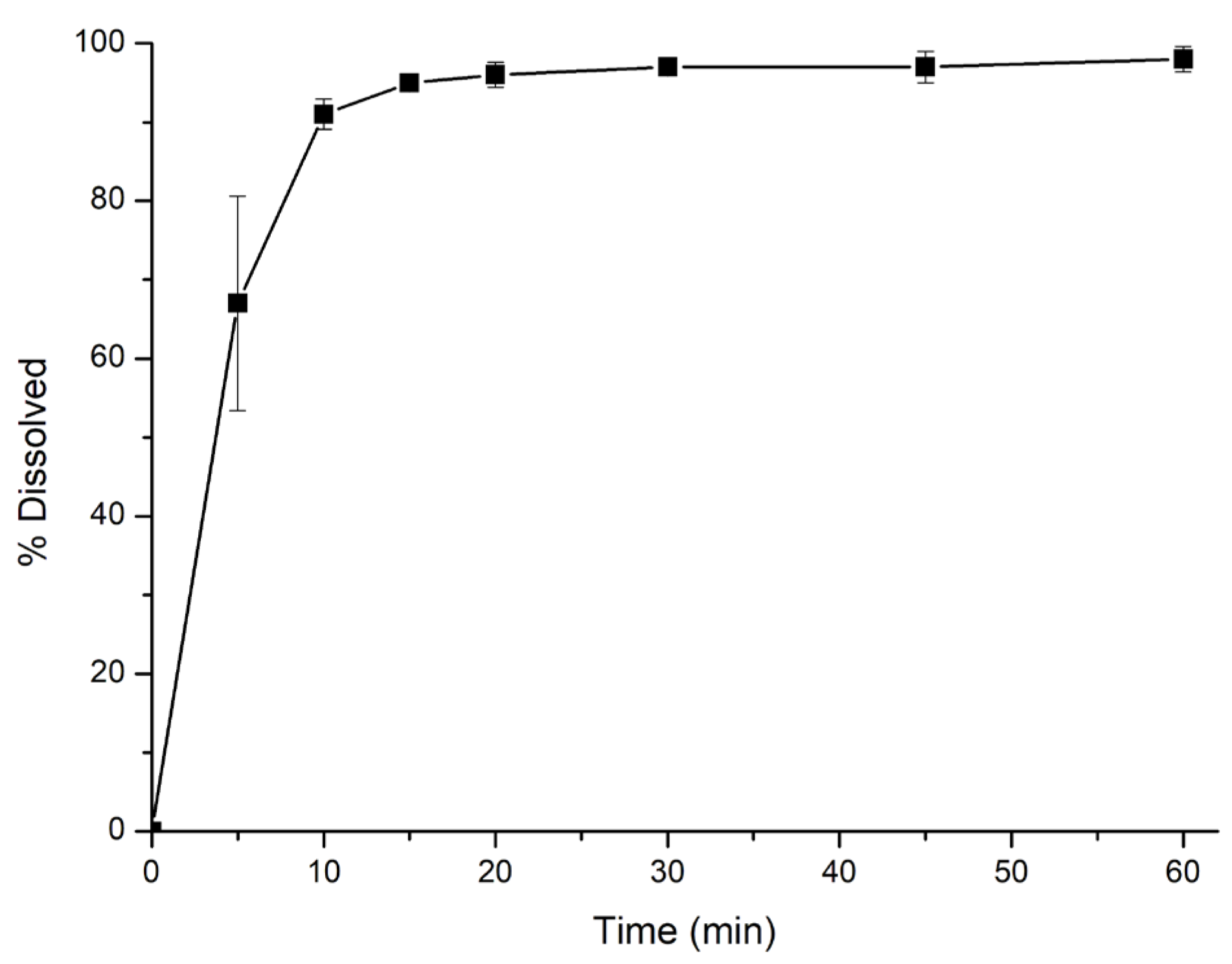

3.2. FDA Dissolution Method

The dissolution profile of Xarelto® 20 mg tablets, obtained by applying the method recommended by the FDA for the 20 mg dose strength, is shown in

Figure 2.

Using the dissolution method recommended by the FDA, rivaroxaban presents very rapid dissolution characteristics. It may be attributed to the high amount (0.4%) of the surfactant SDS used in the dissolution medium, since it was the dissolution medium where rivaroxaban showed the highest solubility (

Table 3). In this scenario, other dissolution test conditions (

Table 1) were tested and in silico tools were used to show their in vivo relevance.

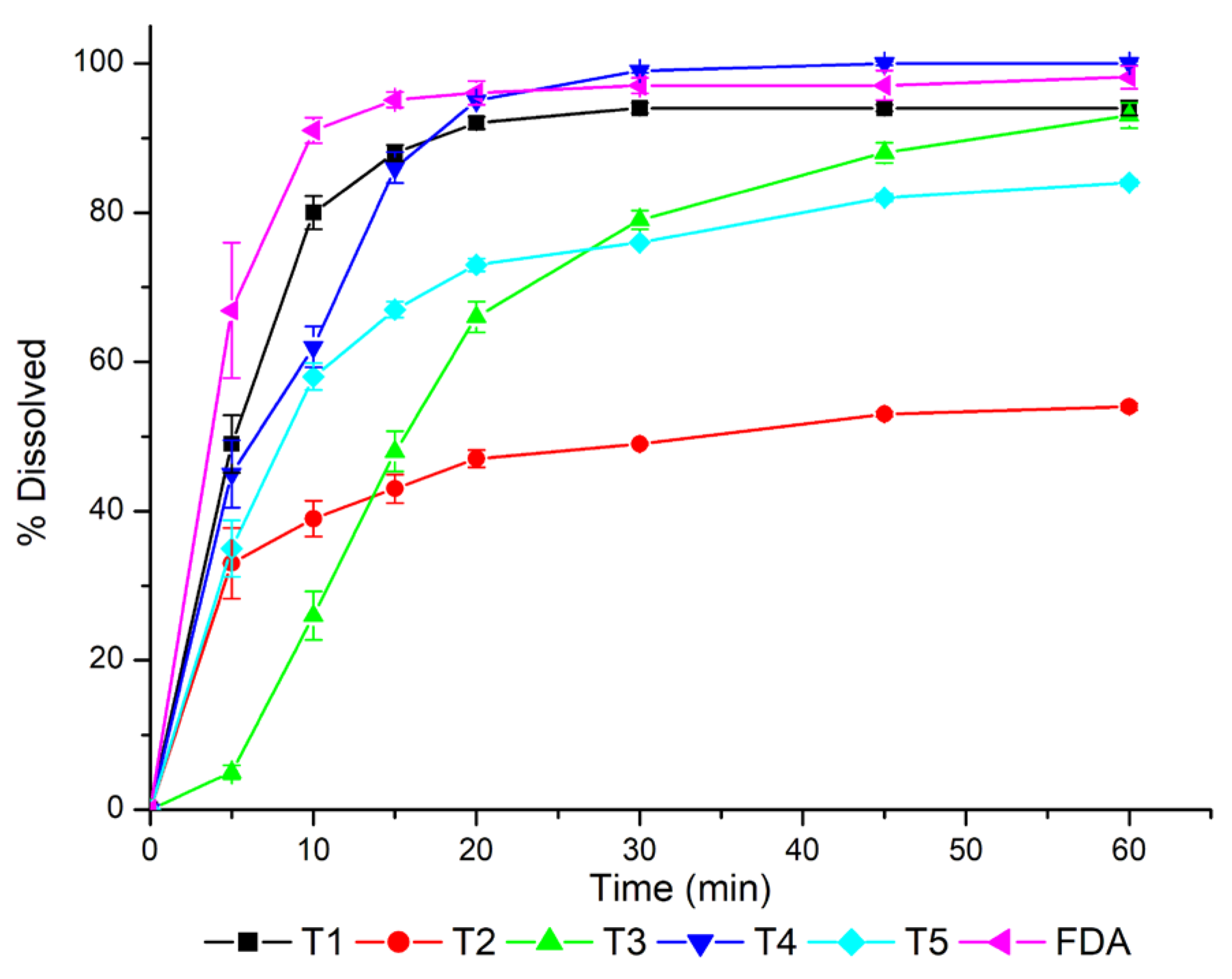

3.3. Development of Biopredictive Dissolution Method and Dissolution Efficiency Evaluation

The results of rivaroxaban percent dissolved from Xarelto® 20 mg tablets when applying the dissolution test conditions previously described in

Table 1, are shown in

Figure 3.

The calculated values of DE were T1 = 83.1%, T2 = 44.5%, T3 = 65.6%, T4 = 84.9%, and T5 = 68.8%. The same amount of SDS (0.25%) was used in the dissolution test conditions T3, T1 and T4, for which the difference was only the rotation speed, 50 rpm, 75 rpm and 100 rpm, respectively (

Table 1). The increase in the rotation speed showed to have an influence on the values of DE, showing lower value for T3 (65.6%) than for T1 (83.5%) and T4 (84.9%). Additionally, the same rotation speed (75 rpm) was used for T2 and T1 conditions, but with different amounts of SDS, 0.10% and 0.25%, respectively. It showed an effect on the percent of rivaroxaban dissolved, and consequently, in the DE values, 44.5% for T2 and 83.7% for T1.

The dissolution profiles obtained for T1 and T4 were closer to that obtained using the FDA dissolution method. For T1 and T4, the same amount of SDS (0.25%) was used, which corresponds to 0.00867 M, and 75 rpm and 100 rpm, respectively, as rotation speed. In these two cases, the amount of SDS used was sufficient to reach its critical micelle concentration (0.008 M), and a minimal rotation speed of 75 rpm was necessary to obtain dissolution profiles closer to the one obtained using the FDA dissolution method. However, despite the same SDS concentration (0.00867 M) used at T3 condition, the rotation speed (50 rpm) showed not to be sufficient to release the drug closer to the dissolution profile obtained using the FDA dissolution method.

The concentration of SDS used at T2 and T5 were 0.10% (0.00347 M) and 0.15% (0.00520 M), respectively, in both cases lower than the CMC of SDS (0.008 M). It is evident that the low amount of SDS used at T2 lead to the lower percent of drug dissolved. It seems that even using 75 rpm as the rotation speed, it was necessary a minimum amount of SDS, even at a concentration lower than its CMC, that should be higher than 0.00347 M. For T5, the combination of 0.00520 M of SDS and a rotation speed of 60 rpm led to a higher amount of drug released in the first 20 minutes of dissolution test compared with the T3.

These dissolution profiles (

Figure 3) were used as input data in GastroPlus® to assess their impact on the bioavailability.

3.4. Development and Validation of the PBPK Model

The obtained hepatic and kidney clearance from the developed PBPK model, CL

liver and CL

kidney were 9.773 L/h and 3.559 L/h, respectively, leading to a predicted systemic clearance CLsys = 13.332 L/h. The volume of distribution Vss was 48.470 L and the half-life T1/2 was 2.519 hours. PBPK model using the tissue to plasma partition coefficients (Kp) described in

Table 2, was applied to both fasted and fed states.

The obtained values of the PK parameters were compared to those reported by references #14 (

Table S1), using the P/O and SC, as part of the first validation step.

The model was able to predict both fasted and fed states, according to the bioavailability values reported in literature [

14]: 66% (fasted) and 80 – 100% (fed). Similarly, the predicted Tmax values were within the observed data 0.8 – 4.0 h (fasted) and 1.3 – 6.0 h (fed), also reported by Kubitza et al. [

14].

In light of these results, it was decided to maintain the ASF values obtained by our optimizations (

Table 2), as they can be supported by the reported behavior of the drug. In addition, the PBPK model was validated by comparative analysis between the simulated pharmacokinetic parameters with the data reported by Kubitza et al. [

23,

24] and Stampfuss et al. [

15], which are presented in

Tables S2 and S3, respectively. Thus, the ASF, as well as the model, were considered satisfactory.

From the results that include the first step of model validation (

Tables S1–S3), predicted PK parameters were compared with the observed data using the P/O ratio and the success criteria (SC) range, as previously described. For the great part of the results, the P/O ratio was within the 0.8 – 1.25 range [

30], and for those cases where P/O was lower than 0.8, the values were within the success criteria. SC is very useful because it considers the coefficient of variation and the number of subjects included in the in vivo study, mainly for drugs with high variability and when the observed data was obtained from a low number of subjects [

26]. SC was previously used to compare predicted vs observed PK data of immediate and extended-release dosage forms, showing to be a valuable comparison criterion [

31,

32].

For the second validation step, the PBBM was challenged by introducing the dissolution profile of Xarelto® 20 mg tablets, obtained experimentally, using the dissolution method recommended by the FDA (acetate buffer pH 4.5, containing 0.4% of SDS), referred as FDA method, modeled fitting it to a Weibull function. The simulated PK parameters were compared with the data from reference #14 (

Table S4), and were within the acceptance range considering P/O and SC range, for both fasted and fed states.

For all simulations, predicted plasma concentration-time curve of 20 mg rivaroxaban tablets, in fasted state, showed a reduction of 56%, 69% and 75% for C

max, AUC

0-t and T

max, respectively, in comparison to fed state. These results demonstrate that food intake improves rivaroxaban’s bioavailability, in accordance with literature [

14,

15,

33,

34].

The change in ASF values suggests that these parameters have high sensibility to physiological changes that occur in the fasted and fed state. In addition, it might significantly impact the formulation’s absorption kinetics, since there are still several unknown factors involved in absorption in the lower portion of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) [

35].

The results obtained by our simulations show that the bioavailability of rivaroxaban is reduced in the fasted state, which is in accordance with literature. Therefore, the optimization of ASF values for the fasted conditions, in order to adjust the predictive absorption in the GIT compartments, resulted in approximately 30% lower ASF values, in comparison with the default settings to fed state (

Table 2). This reduction fits the reduced bioavailability of the compound in the fasted state, which is related to its decreased absorption, due to low solubility.

In contrast, the ASF values obtained by Kushwah et al. [

29], also using the optimization module in the GastroPlus

®, were approximately 14-fold higher than the default values. These increased values mean faster absorption of the drug, especially in the small intestine, which requires higher dissolution of a low solubility drug and may contribute to a higher bioavailability in the fasted state. Nevertheless, this phenomenon diverges from the reported critical material attribute (low solubility) and clinical data (decreased bioavailability in fasted state), reported in literature.

A key point of our results is the obtainment of acceptable predictions (

Table S4) using dissolution results obtained using the dissolution method recommended by the FDA. It represents an advantage since it is applicable for quality control and stability tests, providing greater safety in releasing the products to the market, as well as useful in post-approval changes.

Since predicted values in all validation steps, considering the mechanistic factors affecting drug absorption, were contemplated in the P/O or SC range, the model was considered validated and it was used to evaluate different dissolution profiles, with focus on the evaluation of biopredictive power of each dissolution test condition.

3.5. PBPK Model Use and Virtual Bioequivalence Studies

Using the dissolution profiles obtained from the dissolution test conditions T1, T3, T4 and T5 showed to pass in the VBE in both fasted and fed states, while T2 failed in both conditions, as shown in

Table 5.

These VBE studies were performed to test the biopredictive power of the dissolution methods (

Table 1). Biopredictive dissolution methods are defined as those dissolution test conditions that can be used to quantitatively predicted in vivo PK profiles [

36].

The approval of T1, T3, T4, and T5 in VBE for both fasted and fed states means that these dissolution test conditions can be used as biopredictive dissolution methods, since it was able to adequately predict the in vivo outcomes in these cases. The dissolution profile obtained using the T2 dissolution test (

Figure 3) did not show adequate biopredictive power (

Table 5).

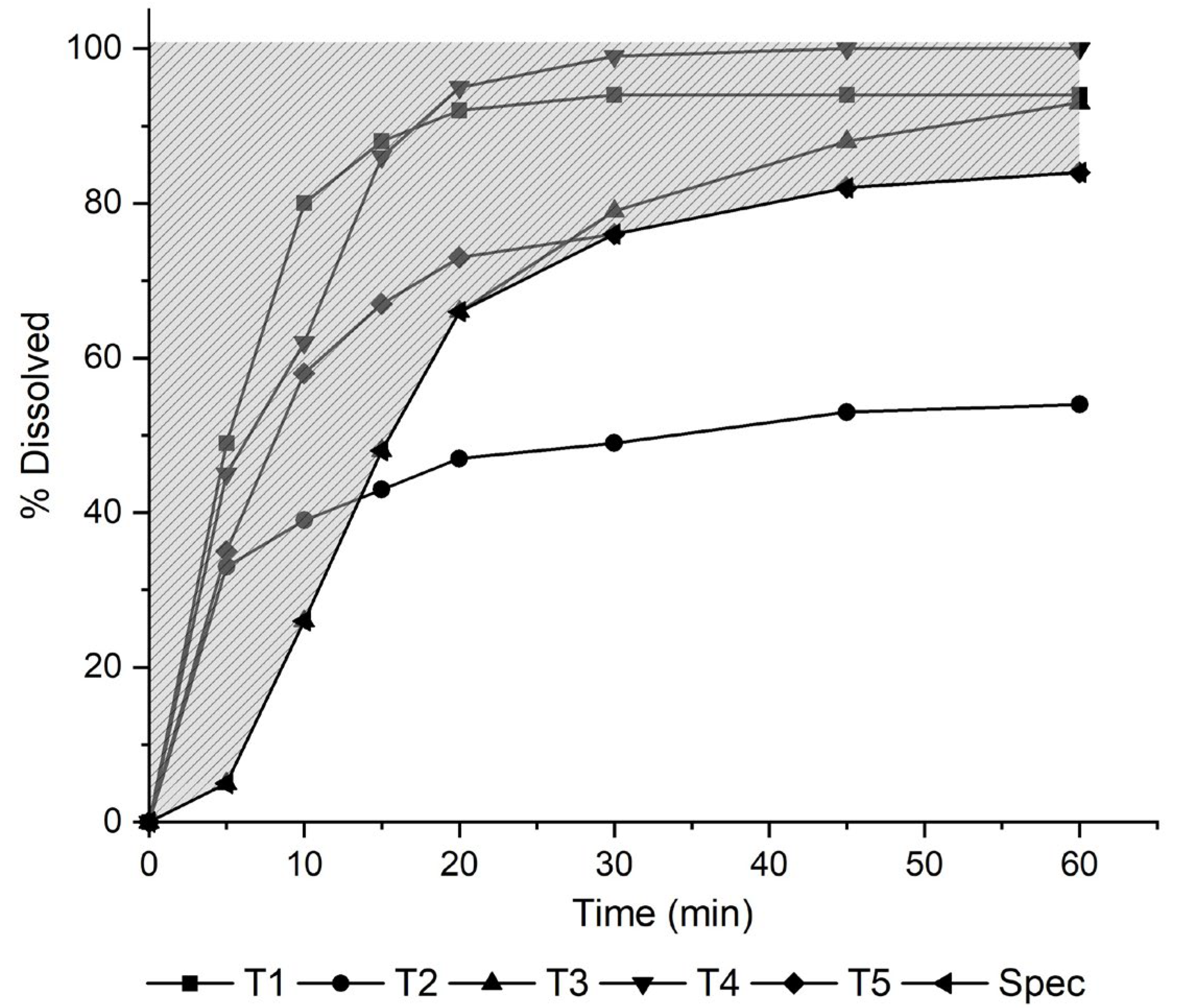

By running these VBE studies (

Table 5), and considering the dissolution profiles (

Figure 3) obtained for each test condition (

Table 1), it was possible to build a dissolution safe space (

Figure 4) and to set a dissolution specification.

IR tablet formulations containing 20 mg of rivaroxaban, which dissolution profile is within T3 up to 20 minutes and, after this, T5 up to 60 minutes (lower limit) and the dissolution profile of the FDA dissolution method (upper limit) can be bioequivalent.

Additionally, a dissolution test specification of not less than 66% dissolved in 20 minutes, that is amount of drug dissolved found for T3, and not less than 84% dissolved in 60 minutes, could be used as a quality control specification.

The development of PBPK models for molecules with high variability consists of a major challenge, which makes model validation essential to ensure its robustness and reproducibility. Nevertheless, we obtained as output a particular in silico absorption profile for each dissolution condition. It demonstrated that PBBM has the potential to increase the robustness of the evaluations of biopredictive power of the dissolution tests. Moreover, it contributes with the consistency of virtual bioequivalence studies, which allows the prediction of the formulations’ quality by its dissolution performance.

The developed PBBM was based on a PBPK model, which considers all tissues and organs compartmentalized and interconnected by the bloodstream – showing to be adequate, as it has higher complexity, with all processes involved in drug absorption and elimination considered in the system [

37].

4. Conclusions

The combination of the amount of SDS used in the dissolution medium and the rotation speed showed to be important to its biopredictive power. It can be achieved using a minimal of 0.15% (0.00520 M) of SDS and a rotation speed of 60 rpm, that was used for T5 dissolution test condition. A dissolution specification of not less than 66% dissolved in 20 minutes and 84% in 60 minutes can be used for quality control purposes. Additionally, the PBBM developed and validated, and was able to capture the differences in the dissolution behavior in each case, in both fasted and fed conditions, by running virtual bioequivalence studies. This approach can help pharmaceutical companies in the development of dissolution tests and to set up biopredictive dissolution test specifications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, table S1: Comparative analysis of pharmacokinetic parameters with observed [

14] and predicted data, in fasted and fed states, for the administration of Xarelto® 20 mg tablets; Table S2: Comparative analysis of the predicted PK parameters with the observed data of Xarelto® 20 mg’s intake [

23,

24], in fasted and fed states; Table S3: Comparative analysis of the predicted PK parameters with the observed data of Xarelto® 20 mg’s intake (15), in fasted and fed states; Table S4: Second validation step with a comparative analysis of pharmacokinetic parameters with observed [

14] and predicted data, in fasted and fed states, using the dissolution profile of Xarelto® 20 mg tablets, obtained using the FDA recommended dissolution method [

19], as input data, modeled by fitting it to a Weibull function.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, E.N.C.L., M.G.I. and M.D.D.; methodology, E.N.C.L., M.G.I. and M.D.D.; software, E.N.C.L., B.W.C.J. and M.D.D.; validation, E.N.C.L. and B.W.C.J.; formal analysis, E.N.C.L, M.G.I. and M.D.D.; investigation, E.N.C.L. and B.W.C.J.; resources, H.G.F., M.G.I. and M.D.D.; data curation, M.G.I. and M.D.D.; writing—original draft preparation, E.N.C.L. and B.W.C.J.; writing—review and editing, H.G.F., M.G.I. and M.D.D.; visualization, H.G.F. and M.G.I.; supervision, M.D.D.; project administration, E.N.C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article and in the Supplementary Material.

Acknowledgments

Portions of these results were generated using GastroPlus® software (provided by Simulations Plus Inc., Lancaster, CA, USA) as academic license.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FDA—U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Analyses - Format and Content Guidance for Industry. 2018, Available online:. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/101469/download (accessed on day month year).

- FDA—U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). The use of physiologically based pharmacokinetic analyses - biopharmaceutics applications for oral drug product development, manufacturing changes, and controls guidance for industry – draft guidance. 2020, Available online:. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/142500/download (accessed on day month year).

- EMA - European Medicines Agency Guideline on the reporting of physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modelling and simulation. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). 2019, Available online:. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-reporting-physiologically-based-pharmacokinetic-pbpk-modelling-and-simulation_en.pdf (accessed on day month year).

- Ghate, V.M.; Chaudhari, P.; Lewis, S.A. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modelling for in vitro-in vivo extrapolation: Emphasis on the use of dissolution data. Dissolution Technologies 2019, 26, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo, M.; Hens, B. , Dickens, J.; Mudie, D.; Paixão, P.; Tsume, Y.; Shedden K.; Amidon G.L. A mechanistic physiologically- based biopharmaceutics modeling (PBBM) approach to assess the in vivo performance of an orally administered drug product: from IVIVC to IVIVP. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAllister, M.; Flanagan, T.; Cole, S.; Abend, A.; Kotzagiorgis, E.; Limberg, J.; Mead, H.; Mangas-Sanjuan, V.; Dickinson, P.A.; Moir, A.; Pepin, X.; Zhou, D.; Tistaert, C.; Dokoumetzidis, A.; Anand, O.; Le Merdy, M.; Turner, D.B.; Griffin, B.T.; Darwich, A.; Dressman, J.; Mackie, C. Developing Clinically Relevant Dissolution Specifications (CRDSs) for Oral Drug Products: Virtual Webinar Series. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang X, Lionberger RA, Davit BM, Yu LX. Utility of physiologically based absorption modeling in implementing Quality by Design in drug development. AAPS J 2011, 13, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heimbach, T.; Suarez-Sharp, S.; Kakhi, M.; Holmstock, N.; Olivares-Morales, A.; Pepin, X.; Sjögren, E.; Tsakalozou, E.; Seo, P.; Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Lin, H.P.; Montague, T.; Mitra, A.; Morris, D.; Patel, N.; Kesisoglou, F. Dissolution and Translational Modeling Strategies Toward Establishing an In Vitro-In Vivo Link-a Workshop Summary Report. AAPS J 2019, 21, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, V.A.; Mann, J.C.; Barker, R.; Pepin, X. The case for physiologically based biopharmaceutics modelling (PBBM): what do dissolution scientists need to know? Dissolution Technologies 2020, 27, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jereb, R.; Opara, J.; Legen, I.; Petek, B.; Grabnar-Peklar, D. In vitro-In vivo Relationship and Bioequivalence Prediction for Modified-Release Capsules Based on a PBPK Absorption Model. AAPS PharmSciTech 2019, 21, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.; Suarez-Sharp, S.; Pepin, X.J.H.; Flanagan, T.; Zhao, Y.; Kotzagiorgis, E.; Parrott, N.; Sharan, S.; Tistaert, C.; Heimbach, T.; Zolnik, B.; Sjögren, E.; Wu, F.; Anand, O.; Kakar, S.; Li, M.; Veerasingham, S.; Kijima, S.; Lima Santos, G.M.; Ning, B.; Raines, K.; Rullo, G.; Mandula, H.; Delvadia, P.; Dressman, J.; Dickinson, P.A.; Babiskin, A. Applications of Physiologically Based Biopharmaceutics Modeling (PBBM) to Support Drug Product Quality: A Workshop Summary Report. J Pharm Sci 2021, 110, 594–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueck, W.; Stampfuss, J.; Kubitza, D.; Becka, M. Clinical pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of rivaroxaban. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2014, 53, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer. Package leaflet: information for the user, Approval by ANVISA, 2021. Available online: https://consultas.anvisa.gov.br/#/bulario/q/?nomeProduto=Xarelto. (accessed on day month year).

- Kubitza, D.; Becka, M.; Zuehlsdorf, M.; Mueck, W. Effect of food, an antacid, and the H2 antagonist ranitidine on the absorption of BAY 59-7939 (rivaroxaban), an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor, in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol 2006, 46, 549–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stampfuss, J.; Kubitza, D.; Becka, M.; Mueck, W. The effect of food on the absorption and pharmacokinetics of rivaroxaban. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2013, 51, 549–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuruya, Y.; Nakanishi, T.; Komori, H.; Wang, X.; Ishiguro, N.; Kito, T.; Ikukawa, K.; Kishimoto, W.; Ito, S.; Schaefer, O.; Ebner, T.; Yamamura, N.; Kusuhara, H.; Tamai, I. Different Involvement of OAT in Renal Disposition of Oral Anticoagulants Rivaroxaban, Dabigatran, and Apixaban. J Pharm Sci 2017, 106, 2524–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaik, A.N.; Lukacova, V.; Fraczkiewicz, G.; A physiologically based pharmacokinetic model of rivaroxaban: role of OAT3 and P-gp transporters in renal clearance. Conference W1230-05-39.2018 AAPS Annual meeting PharmSci 360, Washington D.C., USA, (4/11/2018). Available online: https://www.simulations-plus.com/assets/AAPS_2018-Rivaroxaban- Poster_AN-Shaik.pdf. (accessed on day month year).

- Çelebier, M.; Kaynak, M.S.; Altinöz, S.; Sahin, S. UV spectrophotometric method for determination of the dissolution profile of rivaroxaban. Dissolution Technologies 2014, 21, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA—U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). FDA-recommended dissolution methods 2011. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/dissolution/dsp_getallData.cfm. (accessed on day month year).

- Willmann, S.; Becker, C.; Burghaus, R.; Coboeken, K.; Edginton, A.; Lippert, J.; Siegmund, H.U.; Thelen, K.; Mück, W. Development of a paediatric population-based model of the pharmacokinetics of rivaroxaban. Clin Pharmacokinet 2014, 53, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillo, J.A.; Zhao, P.; Bullock, J.; Booth, B.P.; Lu, M.; Robie-Suh, K.; Berglund, E.G.; Pang, K.S.; Rahman, A.; Zhang, L.; Lesko, L.J.; Huang, S.M. Utility of a physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling approach to quantitatively predict a complex drug-drug-disease interaction scenario for rivaroxaban during the drug review process: implications for clinical practice. Biopharm Drug Dispos 2012. 33, 99–110. [CrossRef]

- Cheong, E.J.Y.; Teo, D.W.X.; Chua, D.X.Y.; Chan, E.C.Y. Systematic Development and Verification of a Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model of Rivaroxaban. Drug Metab Dispos 2019, 2019. 47, 1291–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubitza D, Becka M, Wensing G, Voith B, Zuehlsdorf M. Safety, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics of BAY 59-7939--an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor--after multiple dosing in healthy male subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol, 2005; 61, 873–800.

- Kubitza D, Becka M, Voith B, Zuehlsdorf M, Wensing G. Safety, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics of single doses of BAY 59-7939, an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2005, 78, 412–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA—U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Guidance for Industry. Extended-release oral dosage forms: development, evaluation, and application of in vitro/in vivo correlations. 1997. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/70939/download. (accessed on day month year).

- Abduljalil K, Cain T, Humphries H, Rostami-Hodjegan A. Deciding on success criteria for predictability of pharmacokinetic parameters from in vitro studies: an analysis based on in vivo observations. Drug Metabolism and Disposition, 2014; 42.

- BRAZIL. Brazilian Health Surveillane Agency (ANVISA). Resolução RE nº1170 de 19 de abril de 2006. Guia para provas de biodisponibilidade relativa/bioequivalência de medicamentos. CFAR/GTFAR/CGMED/ANVISA. 2006. Available online: http://antigo.anvisa.gov.br/documents/10181/2718376/%281%29RE_1170_2006_COMP.pdf/52326927-c379-45b4-9a7e-9c5ecabaa16b. (accessed on day month year).

- FDA—U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Guidance for industry Statistical approaches to establishing bioequivalence. 2001. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/70958/download. (accessed on day month year).

- Kushwah V, Arora S, Tamás Katona M, Modhave D, Fröhlich E, Paudel A. On Absorption Modeling and Food Effect Prediction of Rivaroxaban, a BCS II Drug Orally Administered as an Immediate-Release Tablet. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samant TS, Lukacova V, Schmidt S. Development and qualification of physiologically based pharmacokinetic models for drugs with atypical distribution behavior: a desipramine case study. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol, 2017; 6, 315–321.

- Medeiros JJS, Costa TM, Carmo MP, Nascimento DD, Lauro ENC, Oliveira CA, Duque MD, Prado LD. Efficient drug development of oseltamivir capsules based on process control, bioequivalence and PBPK modeling. Drug Dev Ind Pharm, 2022; 48, 146–157.

- Issa MG, de Souza, NV, Jou BWC, Duque MD, Ferraz HG. Development of extended-release mini-tablets containing metoprolol supported by design of experiments and physiologically based biopharmaceutics modeling. Pharmaceutics, 2022; 14, 892.

- Greenblatt DJ, Patel M, Harmatz JS, Nicholson WT, Rubino CM, Chow CR. Impaired Rivaroxaban Clearance in Mild Renal Insufficiency with Verapamil Coadministration: Potential Implications for Bleeding Risk and Dose Selection. J Clin Pharmacol 2018, 58, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueck W, Lensing AW, Agnelli G, Decousus H, Prandoni P, Misselwitz F. Rivaroxaban: population pharmacokinetic analyses in patients treated for acute deep-vein thrombosis and exposure simulations in patients with atrial fibrillation treated for stroke prevention. Clin Pharmacokinet 2011, 50, 675–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra A, Petek B, Bajc A, Velagapudi R, Legen I. Physiologically based absorption modeling to predict bioequivalence of controlled release and immediate release oral products. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2019, 134, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu D, Sanghavi M, Kollipara S, Ahmed T, Saini AK, Heimbach T. Physiologically based pharmacokinetics modeling in biopharmaceutics: case studies for establishing the bioequivalence safe space for innovator and generic drugs. Pharm Res, 2023; 40, 337–357.

- Lin L, Wong H. Predicting Oral Drug Absorption: Mini Review on Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic Models. Pharmaceutics 2017, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).