Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

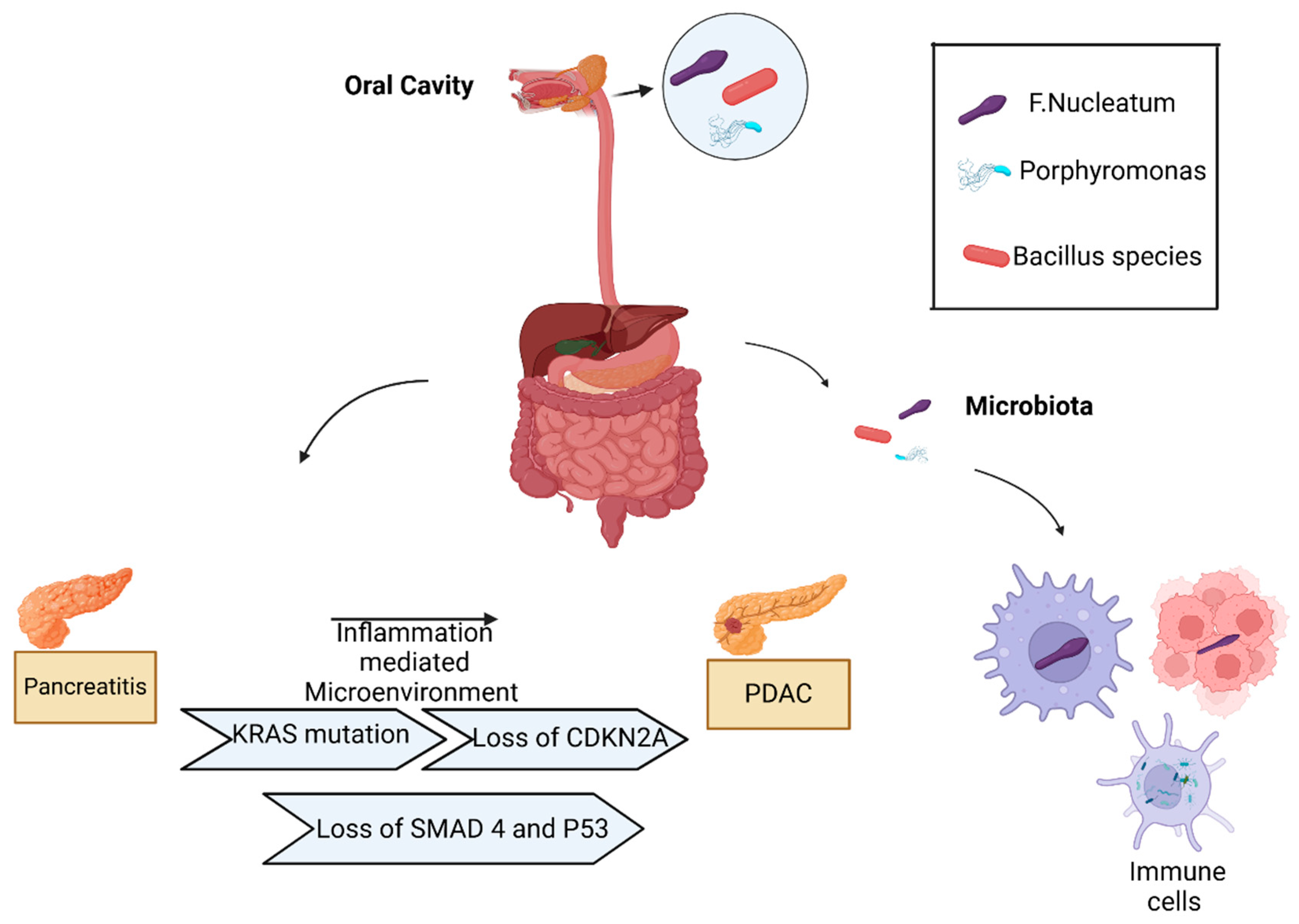

1. Microbiota in Healthy Pancreas

2. Pancreatic Cancer Intratumoral Microbiota

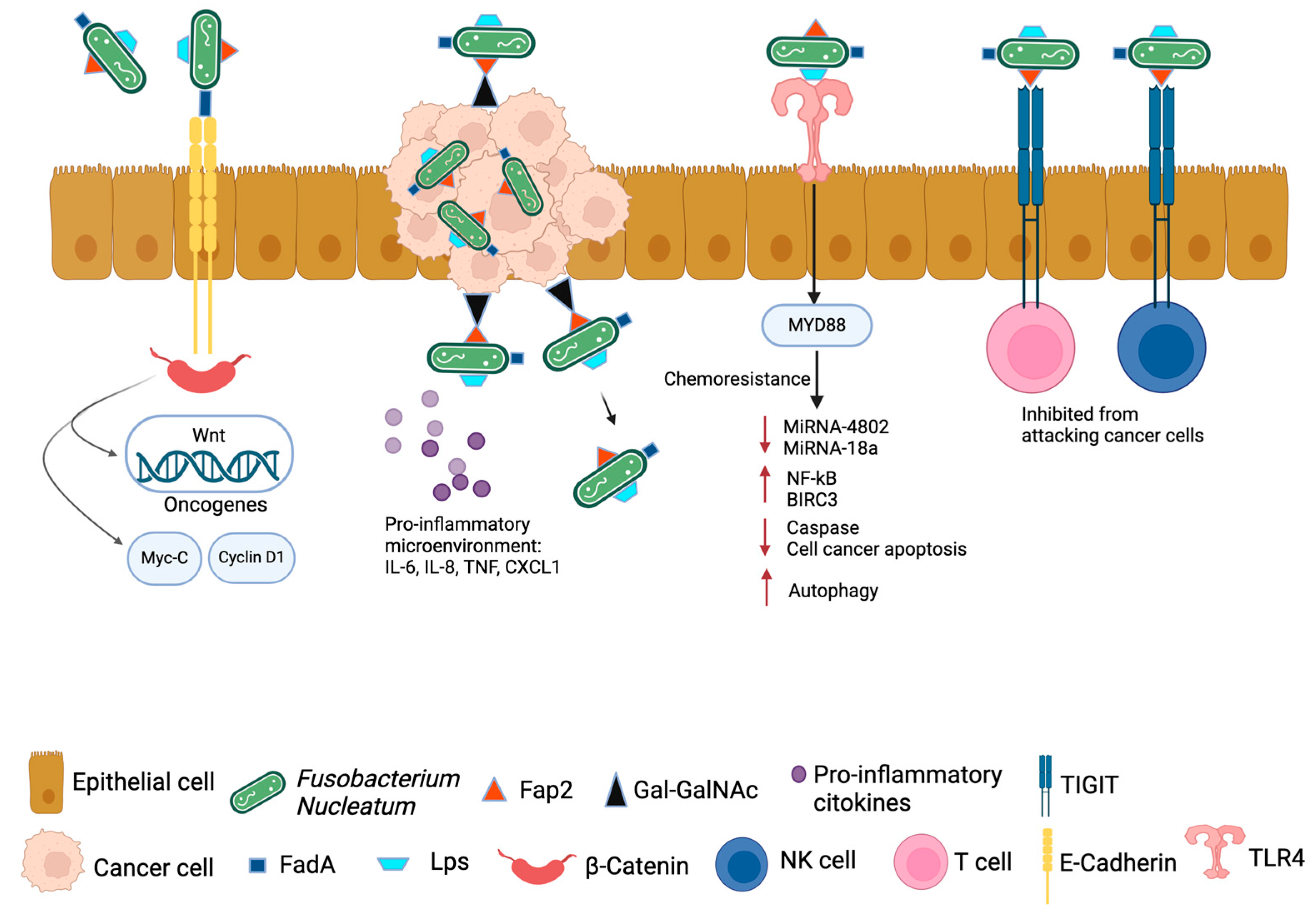

3. Fn Oncobacterium and Its Pathogenic Mechanism in Pancreatic Cancer Development

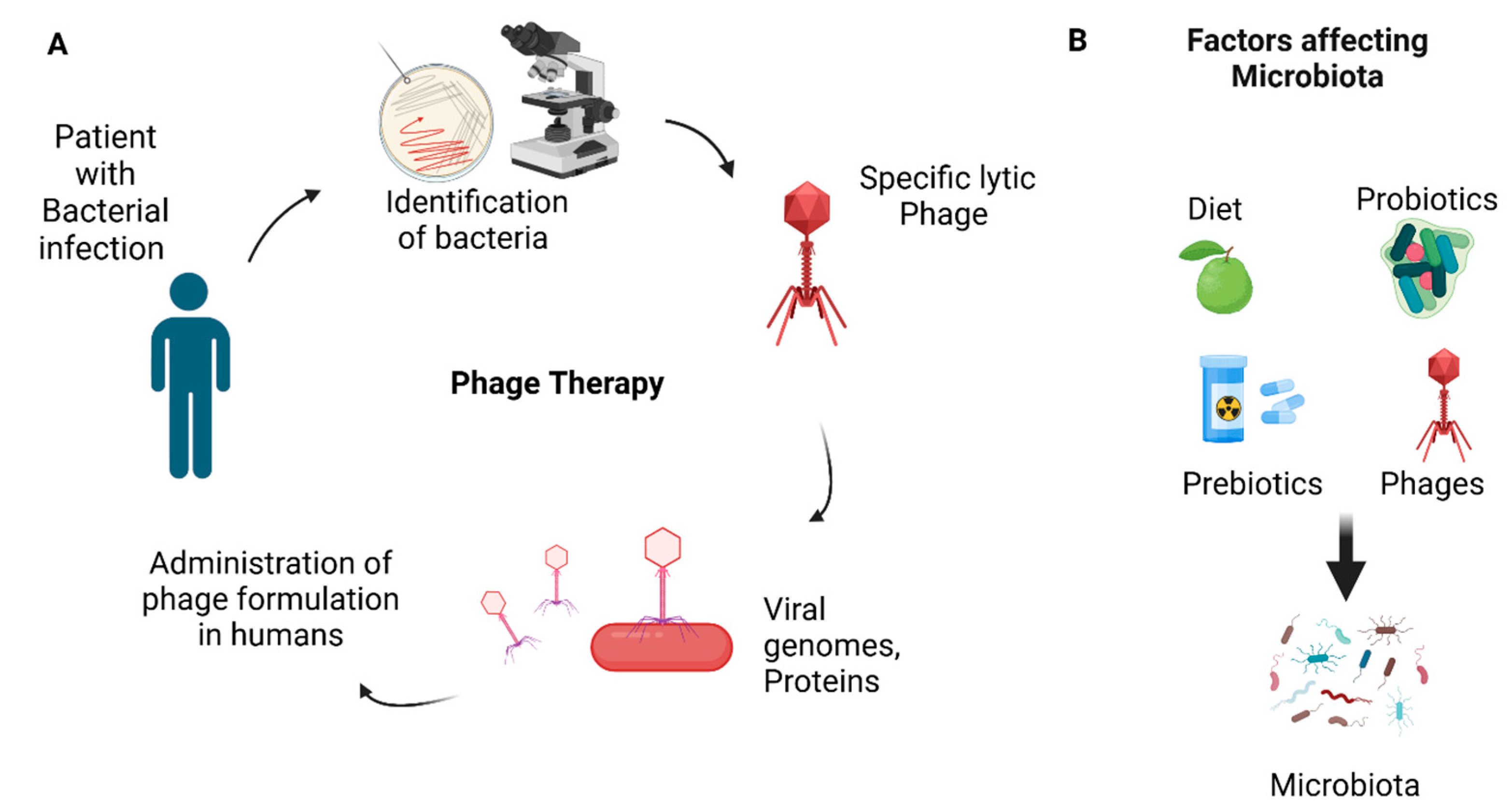

4. Fusobacterium nucleatum and Pancreatic Cancer Prognosis, Therapy, and Biomarkers

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thomas, R.M.; et al. Intestinal microbiota enhances pancreatic carcinogenesis in preclinical models. Carcinogenesis. 2018, 39, 1068–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, L.T.; et al. Potential role of intratumor bacteria in mediating tumor resistance to the chemotherapeutic drug gemcitabine. Science. 2017, 357, 1156–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong-Rolle, A.; et al. Unexpected guests in the tumor microenvironment: microbiome in cancer. Protein Cell. 2021, 12, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pushalkar, S.; et al. The Pancreatic Cancer Microbiome Promotes Oncogenesis by Induction of Innate and Adaptive Immune Suppression. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, V.; et al. Gut Microbiota Promotes Tumor Growth in Mice by Modulating Immune Response. Gastroenterology. 2018, 155, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, G.E.; et al. Microbiota restricts trafficking of bacteria to mesenteric lymph nodes by CX(3)CR1(hi) cells. Nature. 2013, 494, 116–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Blas, A.; et al. Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Travels to Mesenteric Lymph Nodes Both with Host Cells and Autonomously. J Immunol. 2019, 202, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevins, C.L. and N.H. Salzman. Paneth cells, antimicrobial peptides and maintenance of intestinal homeostasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011, 9, 356–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medveczky, P., R. Szmola, and M. Sahin-Toth. Proteolytic activation of human pancreatitis-associated protein is required for peptidoglycan binding and bacterial aggregation. Biochem J. 2009, 420, 335–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, C.J.; et al. The proteome of normal pancreatic juice. Pancreas. 2012, 41, 186–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; et al. Pancreatic beta-Cells Limit Autoimmune Diabetes via an Immunoregulatory Antimicrobial Peptide Expressed under the Influence of the Gut Microbiota. Immunity. 2015, 43, 304–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahuja, M.; et al. Orai1-Mediated Antimicrobial Secretion from Pancreatic Acini Shapes the Gut Microbiome and Regulates Gut Innate Immunity. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marroncini, G.; et al. Gut-Liver-Pancreas Axis Crosstalk in Health and Disease: From the Role of Microbial Metabolites to Innovative Microbiota Manipulating Strategies. Biomedicines. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, P., G.L. Hold, and H.J. Flint. The gut microbiota, bacterial metabolites and colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014, 12, 661–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichardt, N.; et al. Phylogenetic distribution of three pathways for propionate production within the human gut microbiota. ISME J. 2014, 8, 1323–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, D.J. and T. Preston. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut Microbes. 2016, 7, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, I.; et al. Free Fatty Acid Receptors in Health and Disease. Physiol Rev. 2020, 100, 171–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, I.; et al. Maternal gut microbiota in pregnancy influences offspring metabolic phenotype in mice. Science. 2020, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolognini, D.; et al. A Novel Allosteric Activator of Free Fatty Acid 2 Receptor Displays Unique Gi-functional Bias. J Biol Chem. 2016, 291, 18915–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, M.; et al. An Acetate-Specific GPCR, FFAR2, Regulates Insulin Secretion. Mol Endocrinol. 2015, 29, 1055–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D.; et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007, 56, 1761–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riviere, A.; et al. Bifidobacteria and Butyrate-Producing Colon Bacteria: Importance and Strategies for Their Stimulation in the Human Gut. Front Microbiol. 2016, 7, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pishvaian, M.J. and J.R. Brody. Therapeutic Implications of Molecular Subtyping for Pancreatic Cancer. Oncology (Williston Park). 2017, 31, 159–66. [Google Scholar]

- Park, W., A. Chawla, and E.M. O'Reilly. Pancreatic Cancer: A Review. JAMA. 2021, 326, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi, J.D.; et al. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2020, 395, 2008–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, W.; et al. Improvement of surgical results for pancreatic cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, e476–e485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.J. , Brief communication: a new combination in the treatment of advanced pancreatic cancer. Semin Oncol. 2005, 32 (6 Suppl S8), 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahan, L.; et al. Combination 5-fluorouracil, folinic acid and cisplatin (LV5FU2-CDDP) followed by gemcitabine or the reverse sequence in metastatic pancreatic cancer: final results of a randomised strategic phase III trial (FFCD 0301). Gut. 2010, 59, 1527–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammel, P.; et al. Effect of Chemoradiotherapy vs Chemotherapy on Survival in Patients With Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer Controlled After 4 Months of Gemcitabine With or Without Erlotinib: The LAP07 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016, 315, 1844–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carioli, G.; et al. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2021 with focus on pancreatic and female lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2021, 32, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahib, L.; et al. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 2913–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, A.P. , Pancreatic cancer epidemiology: understanding the role of lifestyle and inherited risk factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021, 18, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, S.; et al. Inherited pancreatic cancer syndromes. Cancer J. 2012, 18, 485–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; et al. Early detection of pancreatic cancer: Where are we now and where are we going? Int J Cancer. 2017, 141, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Electronic address, a.a.d.h.e. and N. Cancer Genome Atlas Research, Integrated Genomic Characterization of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2017, 32, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, S. and F. Mitelman, Cancer cytogenetics. Fourth edition. ed. 2015, Chichester, West Sussex ; Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Pfeffer, U. , Cancer genomics : molecular classification, prognosis and response prediction. 2013, Dordrecht: Springer. vi, 588 pages.

- Marshall, B.J. and J.R. Warren. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984, 1, 1311–5. [Google Scholar]

- Abed, J.; et al. Colon Cancer-Associated Fusobacterium nucleatum May Originate From the Oral Cavity and Reach Colon Tumors via the Circulatory System. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020, 10, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhi, L.; et al. Breast cancer colonization by Fusobacterium nucleatum accelerates tumor growth and metastatic progression. Nat Commun. 2020, 11, 3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, C.A. and W.S. Garrett. Fusobacterium nucleatum - symbiont, opportunist and oncobacterium. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019, 17, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabwe, M.; et al. Lytic Bacteriophage EFA1 Modulates HCT116 Colon Cancer Cell Growth and Upregulates ROS Production in an Enterococcus faecalis Co-culture System. Front Microbiol. 2021, 12, 650849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.K.; et al. Dysbiosis of salivary microbiome and cytokines influence oral squamous cell carcinoma through inflammation. Arch Microbiol. 2021, 203, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Team, N.I.H.H.M.P.A. , A review of 10 years of human microbiome research activities at the US National Institutes of Health, Fiscal Years 2007-2016. Microbiome. 2019, 7, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, W.S. , Cancer and the microbiota. Science. 2015, 348, 80–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belkaid, Y. and T.W. Hand. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell. 2014, 157, 121–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme, E.; et al. Tumor Microbiome Diversity and Composition Influence Pancreatic Cancer Outcomes. Cell. 2019, 178, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.; et al. Fungal mycobiome drives IL-33 secretion and type 2 immunity in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2022, 40, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.P., M. Tangney, and M.J. Claesson. Sequence-Based Characterization of Intratumoral Bacteria-A Guide to Best Practice. Front Oncol. 2020, 10, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Sanchez, P. and G.M. DeNicola. The microbiome(s) and cancer: know thy neighbor(s). J Pathol. 2021, 254, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinwand, J. and G. Miller. Regulation and modulation of antitumor immunity in pancreatic cancer. Nat Immunol. 2020, 21, 1152–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; et al. Intratumoral accumulation of gut microbiota facilitates CD47-based immunotherapy via STING signaling. J Exp Med. 2020, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J., C.Y. Chen, and R.B. Hayes. Oral microbiome and oral and gastrointestinal cancer risk. Cancer Causes Control. 2012, 23, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaiser, R.A.; et al. Enrichment of oral microbiota in early cystic precursors to invasive pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2019, 68, 2186–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogrendik, M. , Oral bacteria in pancreatic cancer: mutagenesis of the p53 tumour suppressor gene. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015, 8, 11835–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nejman, D.; et al. The human tumor microbiome is composed of tumor type-specific intracellular bacteria. Science. 2020, 368, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; et al. Microbiota in Tumors: From Understanding to Application. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2022, 9, e2200470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; et al. History of peptic ulcer disease and pancreatic cancer risk in men. Gastroenterology. 2010, 138, 541–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, H.O.; et al. Helicobacter species ribosomal DNA in the pancreas, stomach and duodenum of pancreatic cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2006, 12, 3038–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; et al. Human oral microbiome and prospective risk for pancreatic cancer: a population-based nested case-control study. Gut. 2018, 67, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Castillo, E.; et al. The Microbiomes of Pancreatic and Duodenum Tissue Overlap and Are Highly Subject Specific but Differ between Pancreatic Cancer and Noncancer Subjects. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2019, 28, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuhashi, K.; et al. Association of Fusobacterium species in pancreatic cancer tissues with molecular features and prognosis. Oncotarget. 2015, 6, 7209–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.; et al. Comparisons of oral, intestinal, and pancreatic bacterial microbiomes in patients with pancreatic cancer and other gastrointestinal diseases. J Oral Microbiol. 2021, 13, 1887680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, R.M. and C. Jobin. Microbiota in pancreatic health and disease: the next frontier in microbiome research. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020, 17, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.; et al. Gut microbial profile analysis by MiSeq sequencing of pancreatic carcinoma patients in China. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 95176–95191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; et al. Pancreatic cyst fluid harbors a unique microbiome. Microbiome. 2017, 5, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, M.; et al. Tumor-Associated Microbiome: Where Do We Stand? Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J.; et al. International Cancer Microbiome Consortium consensus statement on the role of the human microbiome in carcinogenesis. Gut. 2019, 68, 1624–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, M.; et al. Mutagenesis by Microbe: the Role of the Microbiota in Shaping the Cancer Genome. Trends Cancer. 2020, 6, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, A.C.; et al. Polyamine catabolism contributes to enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis-induced colon tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011, 108, 15354–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinadasa, R.N.; et al. Cytolethal distending toxin: a conserved bacterial genotoxin that blocks cell cycle progression, leading to apoptosis of a broad range of mammalian cell lineages. Microbiology (Reading). 2011, 157 Pt 7, 1851–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Tejero, M. and J.E. Galan. CdtA, CdtB, and CdtC form a tripartite complex that is required for cytolethal distending toxin activity. Infect Immun. 2001, 69, 4358–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisan, T.; et al. The Haemophilus ducreyi cytolethal distending toxin induces DNA double-strand breaks and promotes ATM-dependent activation of RhoA. Cell Microbiol. 2003, 5, 695–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.T., H.K. Kantilal, and F. Davamani. The Mechanism of Bacteroides fragilis Toxin Contributes to Colon Cancer Formation. Malays J Med Sci. 2020, 27, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthur, J.C.; et al. Microbial genomic analysis reveals the essential role of inflammation in bacteria-induced colorectal cancer. Nat Commun. 2014, 5, 4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijeras-Raballand, A.; et al. Microbiome and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2021, 45, 101589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, Z.; et al. Exploring Connections between Oral Microbiota, Short-Chain Fatty Acids, and Specific Cancer Types: A Study of Oral Cancer, Head and Neck Cancer, Pancreatic Cancer, and Gastric Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.H.; et al. Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut. 1987, 28, 1221–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qadami, G.H.; et al. Gut Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids: Impact on Cancer Treatment Response and Toxicities. Microorganisms. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, H.Y.; et al. Role of microbiota and microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids in PDAC. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 5661–5675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; et al. More Than Just a Periodontal Pathogen -the Research Progress on Fusobacterium nucleatum. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022, 12, 815318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum and its associated systemic diseases: epidemiologic studies and possible mechanisms. J Oral Microbiol. 2023, 15, 2145729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum: The Opportunistic Pathogen of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases. Front Microbiol. 2022, 13, 860149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britton, T.A.; et al. The respiratory enzyme complex Rnf is vital for metabolic adaptation and virulence in Fusobacterium nucleatum. mBio. 2024, 15, e0175123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alon-Maimon, T., O. Mandelboim, and G. Bachrach. Fusobacterium nucleatum and cancer. Periodontol 2000. 2022, 89, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum in tumors: from tumorigenesis to tumor metastasis and tumor resistance. Cancer Biol Ther. 2024, 25, 2306676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krisanaprakornkit, S.; et al. Inducible expression of human beta-defensin 2 by Fusobacterium nucleatum in oral epithelial cells: multiple signaling pathways and role of commensal bacteria in innate immunity and the epithelial barrier. Infect Immun. 2000, 68, 2907–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.H.; et al. Transcriptome profiling analysis of senescent gingival fibroblasts in response to Fusobacterium nucleatum infection. PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0188755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; et al. FAD-I, a Fusobacterium nucleatum Cell Wall-Associated Diacylated Lipoprotein That Mediates Human Beta Defensin 2 Induction through Toll-Like Receptor-1/2 (TLR-1/2) and TLR-2/6. Infect Immun. 2016, 84, 1446–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatelli, P.; et al. The Role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in Oral and Colorectal Carcinogenesis. Microorganisms. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder Gallimidi, A.; et al. Periodontal pathogens Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum promote tumor progression in an oral-specific chemical carcinogenesis model. Oncotarget. 2015, 6, 22613–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.R.; et al. Diverse Toll-like receptors mediate cytokine production by Fusobacterium nucleatum and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans in macrophages. Infect Immun. 2014, 82, 1914–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, A.; et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis entry into gingival epithelial cells modulated by Fusobacterium nucleatum is dependent on lipid rafts. Microb Pathog. 2012, 53, 234–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metzger, Z.; et al. Synergistic pathogenicity of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum in the mouse subcutaneous chamber model. J Endod. 2009, 35, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, D.J. , New Roles for Fusobacterium nucleatum in Cancer: Target the Bacteria, Host, or Both? Trends Cancer. 2021, 7, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Antonio, D.L.; et al. The Oncobiome in Gastroenteric and Genitourinary Cancers. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatelli, P.; et al. The Potential of Colonic Tumor Tissue Fusobacterium nucleatum to Predict Staging and Its Interplay with Oral Abundance in Colon Cancer Patients. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, M.; et al. Intratumor Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes the progression of pancreatic cancer via the CXCL1-CXCR2 axis. Cancer Sci. 2023, 114, 3666–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, K.; et al. Human Microbiome Fusobacterium Nucleatum in Esophageal Cancer Tissue Is Associated with Prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 5574–5581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.D.; et al. Salivary Fusobacterium nucleatum serves as a potential diagnostic biomarker for gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 4120–4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audirac-Chalifour, A.; et al. Cervical Microbiome and Cytokine Profile at Various Stages of Cervical Cancer: A Pilot Study. PLoS One. 2016, 11, e0153274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokowa-Soltys, K., K. Wojtkowiak, and K. Jagiello. Fusobacterium nucleatum - Friend or foe? J Inorg Biochem. 2021, 224, 111586. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum secretes amyloid-like FadA to enhance pathogenicity. EMBO Re 2021, 22, e52891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; et al. FadA from Fusobacterium nucleatum utilizes both secreted and nonsecreted forms for functional oligomerization for attachment and invasion of host cells. J Biol Chem. 2007, 282, 25000–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirbel, J.; et al. Meta-analysis of fecal metagenomes reveals global microbial signatures that are specific for colorectal cancer. Nat Med. 2019, 25, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abed, J.; et al. Fap2 Mediates Fusobacterium nucleatum Colorectal Adenocarcinoma Enrichment by Binding to Tumor-Expressed Gal-GalNAc. Cell Host Microbe. 2016, 20, 215–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. and J.Y. Fang. Fusobacterium nucleatum, a key pathogenic factor and microbial biomarker for colorectal cancer. Trends Microbiol. 2023, 31, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, J.; et al. Tumor Targeting by Fusobacterium nucleatum: A Pilot Study and Future Perspectives. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017, 7, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castano-Rodriguez, N.; et al. Dysbiosis of the microbiome in gastric carcinogenesis. Sci Re 2017, 7, 15957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.H.; et al. The role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer: from carcinogenesis to clinical management. Chronic Dis Transl Med. 2019, 5, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, P., H. Eslami, and H.S. Kafil. Carcinogenesis mechanisms of Fusobacterium nucleatum. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017, 89, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, M.R.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal cancer by inducing Wnt/beta-catenin modulator Annexin A1. EMBO Re 2019, 20(4).

- Clevers, H. and R. Nusse, Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012, 149, 1192–205. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, S., F. Hua, and Z.W. Hu. The regulation of beta-catenin activity and function in cancer: therapeutic opportunities. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 33972–33989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, T.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Promotes Chemoresistance to Colorectal Cancer by Modulating Autophagy. Cell. 2017, 170, 548–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udayasuryan, B.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum induces proliferation and migration in pancreatic cancer cells through host autocrine and paracrine signaling. Sci Signal. 2022, 15, eabn4948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borowsky, J.; et al. Association of Fusobacterium nucleatum with Specific T-cell Subsets in the Colorectal Carcinoma Microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 2816–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frydrychowicz, M.; et al. Exosomes - structure, biogenesis and biological role in non-small-cell lung cancer. Scand J Immunol. 2015, 81, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, F.; et al. The Tumor Microbiome in Pancreatic Cancer: Bacteria and Beyond. Cancer Cell. 2019, 36, 577–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; et al. Exosomes derived from Fusobacterium nucleatum-infected colorectal cancer cells facilitate tumour metastasis by selectively carrying miR-1246/92b-3p/27a-3p and CXCL16. Gut. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Domenis, R.; et al. Toll-like Receptor-4 Activation Boosts the Immunosuppressive Properties of Tumor Cells-derived Exosomes. Sci Re 2019, 9, 8457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channon, L.M.; et al. Small extracellular vesicles (exosomes) and their cargo in pancreatic cancer: Key roles in the hallmarks of cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2022, 1877, 188728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; et al. The Role of Fecal Fusobacterium nucleatum and pks(+) Escherichia coli as Early Diagnostic Markers of Colorectal Cancer. Dis Markers. 2021, 2021, 1171239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullman, S.; et al. Analysis of Fusobacterium persistence and antibiotic response in colorectal cancer. Science. 2017, 358, 1443–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunzmann, A.T.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum tumor DNA levels are associated with survival in colorectal cancer patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019, 38, 1891–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K. and Y. Hu. Microbiome harbored within tumors: a new chance to revisit our understanding of cancer pathogenesis and treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020, 5, 136. [Google Scholar]

- Michaud, D.S.; et al. A prospective study of periodontal disease and pancreatic cancer in US male health professionals. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007, 99, 171–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mima, K.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal carcinoma tissue and patient prognosis. Gut. 2016, 65, 1973–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.B.; et al. Association between Fusobacterium nucleatum and patient prognosis in metastatic colon cancer. Sci Re 2021, 11, 20263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, L., A. Xu, and J. Xu. Roles of PD-1/PD-L1 Pathway: Signaling, Cancer, and Beyond. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020, 1248, 33–59. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.S.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum-derived succinic acid induces tumor resistance to immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. Cell Host Microbe. 2023, 31, 781–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaCourse, K.D.; et al. The cancer chemotherapeutic 5-fluorouracil is a potent Fusobacterium nucleatum inhibitor and its activity is modified by intratumoral microbiota. Cell Re 2022, 41, 111625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum induces MDSCs enrichment via activation the NLRP3 inflammosome in ESCC cells, leading to cisplatin resistance. Ann Med. 2022, 54, 989–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma progression and chemoresistance by enhancing the secretion of chemotherapy-induced senescence-associated secretory phenotype via activation of DNA damage response pathway. Gut Microbes. 2023, 15, 2197836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da, J.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Promotes Cisplatin-Resistance and Migration of Oral Squamous Carcinoma Cells by Up-Regulating Wnt5a-Mediated NFATc3 Expression. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2021, 253, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, A.A. and G.G. Mackenzie. Pancreatic cancer: A critical review of dietary risk. Nutr Res. 2018, 52, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, H.E.; et al. The tumour microenvironment after radiotherapy: mechanisms of resistance and recurrence. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015, 15, 409–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudarzi, M.; et al. An Integrated Multi-Omic Approach to Assess Radiation Injury on the Host-Microbiome Axis. Radiat Res. 2016, 186, 219–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, S.E.; et al. Human postprandial responses to food and potential for precision nutrition. Nat Med. 2020, 26, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.R.; et al. Dietary prebiotics: current status and new definition. Food Science & Technology Bulletin: Functional Foods. 2010, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Englyst, H.N. and G.T. Macfarlane. Breakdown of resistant and readily digestible starch by human gut bacteria. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 1986, 37, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafari, N.; et al. Role of gut bacterial and non-bacterial microbiota in alcohol-associated liver disease: Molecular mechanisms, biomarkers, and therapeutic prospective. Life Sci. 2022, 305, 120760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersi, F.; et al. Cancer immunotherapy resistance: The impact of microbiome-derived short-chain fatty acids and other emerging metabolites. Life Sci. 2022, 300, 120573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.; et al. Modulation of the Tumor Microenvironment by Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids: Impact in Colorectal Cancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoaf, K.; et al. Prebiotic galactooligosaccharides reduce adherence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to tissue culture cells. Infect Immun. 2006, 74, 6920–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteagudo-Mera, A.; et al. Adhesion mechanisms mediated by probiotics and prebiotics and their potential impact on human health. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 6463–6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourali, G.; et al. Microbiome as a biomarker and therapeutic target in pancreatic cancer. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation in cancer management: Current status and perspectives. Int J Cancer. 2019, 145, 2021–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrof, E.O.; et al. Microbial ecosystems therapeutics: a new paradigm in medicine? Benef Microbes. 2013, 4, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.S.; et al. Durable coexistence of donor and recipient strains after fecal microbiota transplantation. Science. 2016, 352, 586–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R., Z. Chen, and J. Cai. Fecal microbiota transplantation: Emerging applications in autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun. 2023, 141, 103038. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, F.; et al. Optimized Antimicrobial Peptide Jelleine-I Derivative Br-J-I Inhibits Fusobacterium Nucleatum to Suppress Colorectal Cancer Progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Merwe, M.; et al. The onco-immunological implications of Fusobacterium nucleatum in breast cancer. Immunol Lett. 2021, 232, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, J.E.; et al. Circulating IgA Antibodies Against Fusobacterium nucleatum Amyloid Adhesin FadA are a Potential Biomarker for Colorectal Neoplasia. Cancer Res Commun. 2022, 2, 1497–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahara, T.; et al. Fusobacterium in colonic flora and molecular features of colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 1311–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dejea, C.M.; et al. Patients with familial adenomatous polyposis harbor colonic biofilms containing tumorigenic bacteria. Science. 2018, 359, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, J.E.; et al. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases. Eighth edition. ed. Expertconsult. 2015, Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders.

- Gur, C.; et al. Binding of the Fap2 protein of Fusobacterium nucleatum to human inhibitory receptor TIGIT protects tumors from immune cell attack. Immunity. 2015, 42, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusiak-Szelachowska, M., B. Weber-Dabrowska, and A. Gorski. Bacteriophages and Lysins in Biofilm Control. Virol Sin. 2020, 35, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, A., P.R. Sharma, and R. Agarwal. Combatting intracellular pathogens using bacteriophage delivery. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2021, 47, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Belleghem, J.D.; et al. Interactions between Bacteriophage, Bacteria, and the Mammalian Immune System. Viruses. 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabwe, M., S. Dashper, and J. Tucci. The Microbiome in Pancreatic Cancer-Implications for Diagnosis and Precision Bacteriophage Therapy for This Low Survival Disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022, 12, 871293. [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia, C., G.P. Stafford, and C. Murdoch. Porphyromonas gingivalis Outer Membrane Vesicles Increase Vascular Permeability. J Dent Res. 2020, 99, 1494–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; et al. The Role of Porphyromonas gingivalis Outer Membrane Vesicles in Periodontal Disease and Related Systemic Diseases. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020, 10, 585917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).