1. Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic resulted from the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus that emerged in late 2019 [

1]. Its emergence was accompanied by a record number of deaths across the globe. Because of the loss of lives, lockdowns were imminent, leading to businesses shutting down for months to contain the virus. The pandemic strained the healthcare sector to an unprecedented level, as recorded in Europe and the Americas, for example. This development points to the fact that there is a need for a robust diagnostic system for the early detection of the virus [

2]. Its early detection would allow medical personnel to effectively contain it because affected persons would be isolated, contact tracing would start in earnest, and patients would be promptly treated [

2]. Furthermore, early detection could potentially save lives [

2]. The traditional approach for testing patients for COVID-19 has been through the Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) [

3]. This test is usually time-consuming; in addition, it requires specialized skills to carry out the test on patients) [

3]. This development therefore requires that experts be trained on how to effectively administer this process. Also, the process gives a lot of conflicting results, potentially allowing COVID-19 patients to go home due to error [

4]. In addition, there have been cases of false positives recorded via RT-PCR [

5].

In response to this, researchers have come up with artificial intelligence (AI)-based solutions for the detection of COVID-19 from X-rays [

5], CT scans [

6], and cough sounds [

7]. This is now possible because of the availability of datasets. Cough sound has been used to detect COVID-19, as seen in [

8]. They combined this with the symptoms of the patients to make a prediction. The use of a cough signal is useful because a COVID-19 cough produces a distinctive pattern, differentiating it from a normal cough [

8]. This distinctive pattern arises as the virus attacks the lungs, thereby damaging its structure [

8].

Authors have researched several methods for the detection of COVID-19 from images. For example in [

5], they developed a deep learning model that extracts key features from X-ray images and then leverages a pre-trained model (VGG19) for the classification of COVID-19. A pre-trained model reflects an already existing model that has been trained on thousands of images. Therefore, its usage is usually appreciated in image classification tasks – since it has learned images sufficiently from different domains. There is a high likelihood of improved performance when in use in different classification tasks, including medical image classification tasks. Several pre-trained models have been used as seen by authors in [

9]. They used several pre-trained models for their proposed model. Some of the pre-trained models (transfer learning models) are ResNET50, ResNET101, and InceptionV3, the pre-trained models were also finetuned on the collected X-ray images, where the model trained on ResNET101 proved to have outperformed other models. In addition, other research using deep learning models for X-ray COVID-19 detection has also been done as seen in the following papers [

10] [

11]. In [

12], authors used the VGG-19 pre-trained model for the classification of X-ray images with improved performance.

The CT-scan images have also been solely analyzed for the detection of the presence of the COVID-19 virus. For example, authors in [

13] used a similar approach proposed by authors in [

9]. However, they used pre-trained models built on the VGG19 and then compared them to other pre-trained models such as Xception Net, and CNN. From their analysis, it is observed that their model performed satisfactorily. In addition, authors in [

14] developed a deep learning model that improves on traditional deep learning methods. Their model incorporates two key innovations – the ability to reason based on the passed data, and the ability to learn. This means the model does not need input from humans in setting parameters. The model achieved an F1-score of 0.9731 on CT-scan images [

14].

Furthermore, in [

15] they showed that the adoption of a pre-trained model for CT-scan can further improve its classification output compared to models that do not use pre-trained models. On the other hand, researchers have also solely used cough datasets for the prediction of COVID-19. This is because patients suffering from the virus have a distinct way of coughing. After all, their lung structure has been altered [

16] [

17]. Authors in [

18] used a Support Vector Machine (SVM) to classify cough sounds. An ensemble model has also been proposed by authors in [

19]. The model consists of a CNN layer for feature extraction, and then another classification model. The authors went further to develop an application called "AI4COVID-19” where users can interface with their tool.

The papers reviewed above point to the fact that pre-trained models can potentially improve the output of COVID-19 classification. More recently, the use of multimodal deep learning models has been adopted to improve COVID-19 accuracy. For example, in [

20], authors developed a multimodal system that uses X-ray and CT-scan images for classification. They went further to experiment with different transfer learning architectures such as the MobileNetV2 VGG16, and ResNET50 [

20]. Similarly, authors in [

21] used two pre-trained models, one for the CT scan and another for the X-ray. The outputs of these different deep learning layers are then fused to give an improved classification output. Many researchers have also combined datasets from different sources; for example, authors in [

22] combined datasets of X-ray and cough for improved classification. Consequently, two models were developed, and then the outputs of these models were fused. In addition, their cost function gives more weight or relevance to the model with the least error [

22].

Authors in [

23] also used several pre-trained models for the detection of the virus in X-ray images as well as CT-scan images. From their experiment, it was established that VGG19 gave the best result in terms of classification accuracy. It was also established that X-ray images are more accurate in the detection of the virus compared to CT-scan images.

While COVID-19 detection with multimodal architectures exists, as discussed, to the best of our knowledge, no multimodal architectures take advantage of cough, X-ray, and CT scans together for the classification of the COVID-19 virus. In addition, no research has been carried out to investigate the relevance of pre-trained models on multimodal architecture using these three datasets. Our research therefore aims to fill this gap by researching the relevance of a multimodal system using three datasets in the classification of COVID-19 with or without a pre-trained model. In addition, we also explored the contribution of pre-trained models on unimodal systems for cough, X-ray, and CT-scan datasets.

Many researchers have exhausted using unimodal pre-trained models to improve the classification of COVID-19 via X-ray images, CT-scan, and cough, in addition, to using multimodal designs for different combinations such as X-ray and CT scan. No research has been done, from our knowledge, using multimodal designs that combine cough, CT-scan and X-rays. In addition, we investigate further the impact of the VGG19 pre-trained model on unimodal classifications such as for cough, CT-scan, and X-ray, and then the effect of the VGG19 on a multimodal design that leverages on three datasets – cough, X-ray and CT scan. Therefore, this research investigates the impact of pre-trained models (VGG19, ResNET, and MobileNetV2) on a multimodal system that combines three datasets of cough, X-ray and CT scan. This research is important in that it provides an in-depth analysis of how the combination of three datasets can be used to improve COVID-19 classification. In addition, it provides a comparative study of how selected pre-trained models can influence COVID-19 classification from the perspective of unimodal and multimodal systems. Furthermore, this research also provides a platform to look at medical diagnosis from the multimodal perspective as it may potentially improve classification. The motivation behind the combination of these datasets is hinged on the fact that COVID-19 patients usually exhibit these symptoms – lung abnormalities, and cough [

24]. Lung abnormalities can be detected from X-ray images as well as CT scans. There are several advantages to the proposed model of using three datasets. One of them is the ability to harness complementary information - the sound from a cough could depict respiratory disease while images from X-rays and CT scans could reveal the structure of the lungs [

25]. In addition, X-rays and CT-scan can also reveal the extent of damage to the lungs while the cough sounds might indicate early signs of COVID-19 [

25]. In addition, there is the potential to increase sensitivity (correctly identifying persons with COVID-19) and specificity (correctly identifying persons without COVID-19) [

25]. Lastly, data from one source might be unreliable for exams due to poor X-ray or CT-scan images [

25].

2. Materials and Methods

This section discusses the architecture of the proposed model as well as the data preprocessing stages for the datasets used. Recall that we used three datasets: cough sound, X-ray, and CT scan. We therefore need to preprocess the data before passing it into the proposed multimodal architecture.

2.1. Data Pre-Processing

The first dataset is the cough dataset found in [

26]. This dataset has audio that lasts up to 9 seconds, however, on average, each audio has approximately two seconds segment of cough. Therefore, we needed to extract this segment. To do this, each cough file is loaded using the PyTorch torch audio. Load () function. This function then reads the audio waveform (

wf) as seen in Eq. (1).

In Eq. (1), wf is the cough waveform (wf). The next stage is resampling. If the sample rate of the audio is not at 16 kHz, we then resample (Eq. 2).

The conversion of the waveform to a mono channel is next (Eq 3). The conversion is necessary because, the critical information (cough) can be found in one channel, another advantage of using one channel is for noise reduction.

Next, the detection of the cough segment kicks in and it is then extracted. This is done by using the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) [

27]. The STFT breaks the cough waveform into small time windows that would enable signal change detection [

27]. STFT converts the waveform from a time domain into the frequency domain (F) for each frame

[

27]. The next is to calculate the energy of each frame as seen in Eq. (4)

where

squares the size or magnitude of the Short-Time Fourier Transform for each frame. In the next stage, we normalized the energy (Eq. 5).

The normalized energy ( is then analyzed based on a set threshold of 0.5. If an energy’s frame exceeds 0.5, the algorithm then selects the first two seconds of the waveform, effectively collecting the cough portion into.

We used the X-ray dataset found in [

28], [

29], [

30] and [

31] while for the CT scan, we used the dataset in [

14]. The pre-processing for X-ray and CT-scan images is similar. Each image is opened using the PIL image. Open () function, and read as coloured images. The images are further resized into 224 by 224 – since some pre-trained models take images in this size. The preprocessing X-ray images are stored in

while

is for CT-scan.

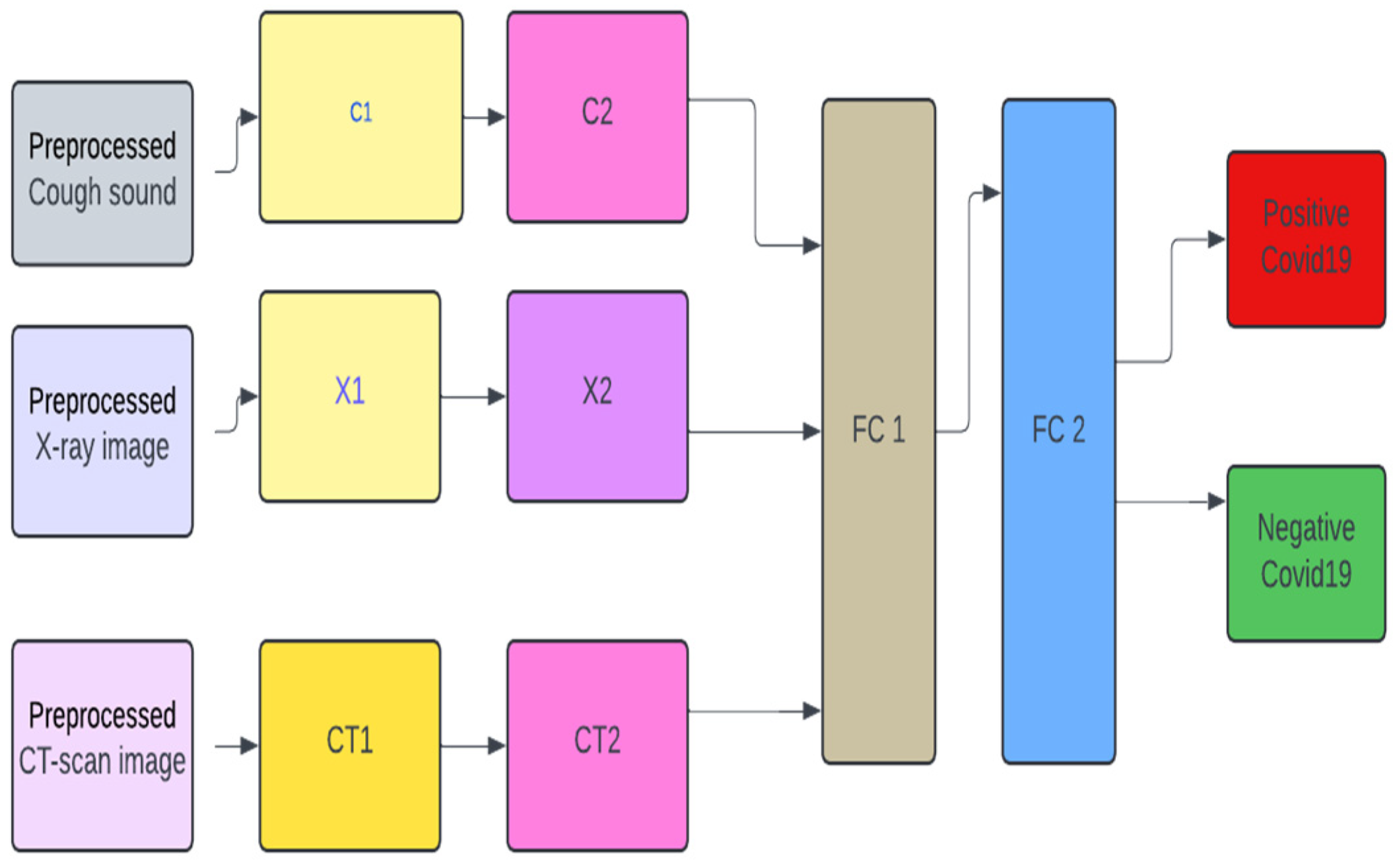

2.2. Model Design

Figure 1 depicts the design of the multimodal system which has five layers, excluding the pre-processing layer. For C1 (which houses the first convolution layer for cough). We have the pre-pressed cough sound (X_audio) being fed into the model via block C1. This block takes the processed cough sounds as input as seen in the equation below. In Eqs. (6), (7), and (8) encapsulate the processes in block C1. In Eq. (7)

p is the dropout value, set to 0.5.

For block

C2, we have Eqs. (9), (10) where

is the output from the previous layer while

are the weights and biases of the block.

For X-ray pre-processed images, we have Eqs. (11), (12), (13), (14), (15), and (16) for blocks X1 and X2

For CT-scan images, we have the following Equations – (17), (18), (19), (20), (21), and (22).

For FC1, in

Figure 1, we have Eq. (23).

combines the outputs from C2, X2, and CT2, as seen in Eq. (24)

has 164,913408 trainable weights while

has 164 trainable parameters.

is the fully connected layer, as seen in

Figure 1. The second fully connected layer is in Eq. (25).

has 1164 trainable parameters while

has 1 parameter. The output of this goes into a sigmoid activation in Eq. (26), and then the output is seen in Eqs. (27) and (28).

2.3. Training

For the training process, we used the Eq. (29). We trained for 30 epochs. The inputs to the proposed model go into the model at the same time. This means that a sample of positive COVID-19 cough, X-ray and CT scan goes into the model at once. This also goes for negative COVID-19. We used batch processing of 8 during the training process.

In Eq. 29, is the model parameter, while is the forward pass of the model. is the learning rate. Lastly) is the loss function.

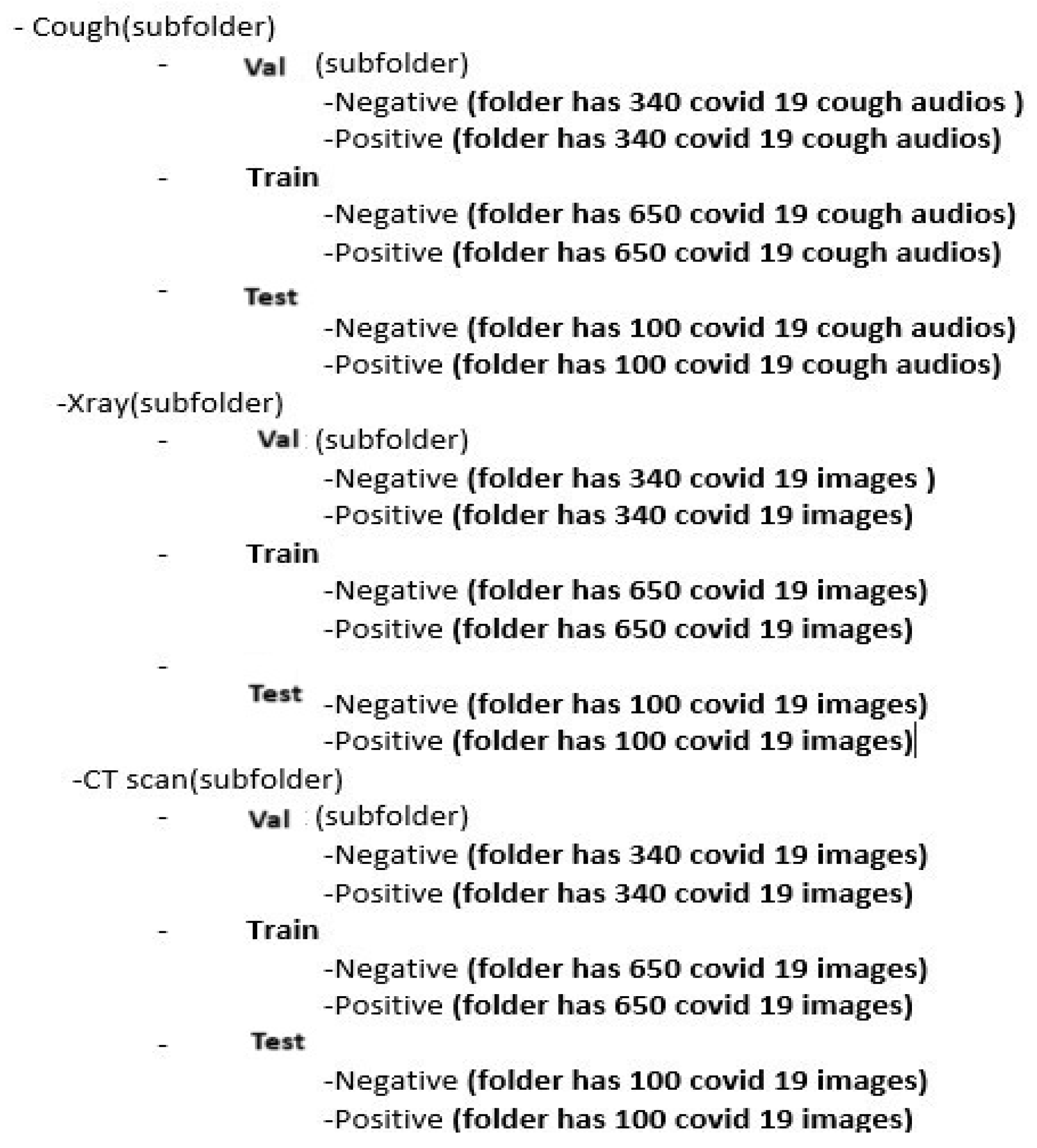

Figure 2 provides the structure of the dataset for training, testing and validation.

2.4. Validation

At the end of each epoch, we validate the model, and if the loss value on the validation dataset is less than the previous epoch, the current training model is saved. For each batch, i of 8 data points (eight cough sounds, eight X-ray images, and eight CT-scan), do the following in Eqs (30) to (35):

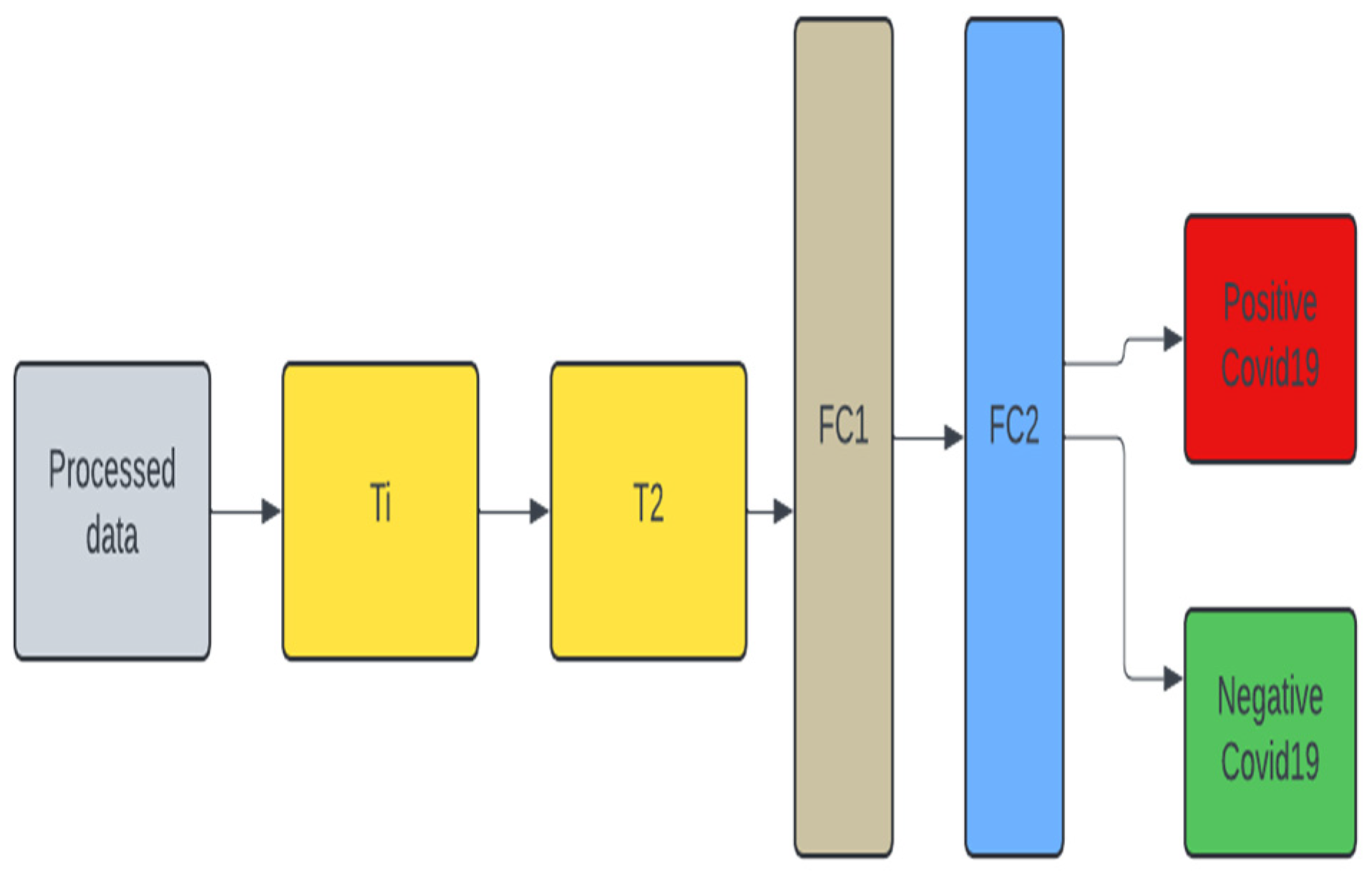

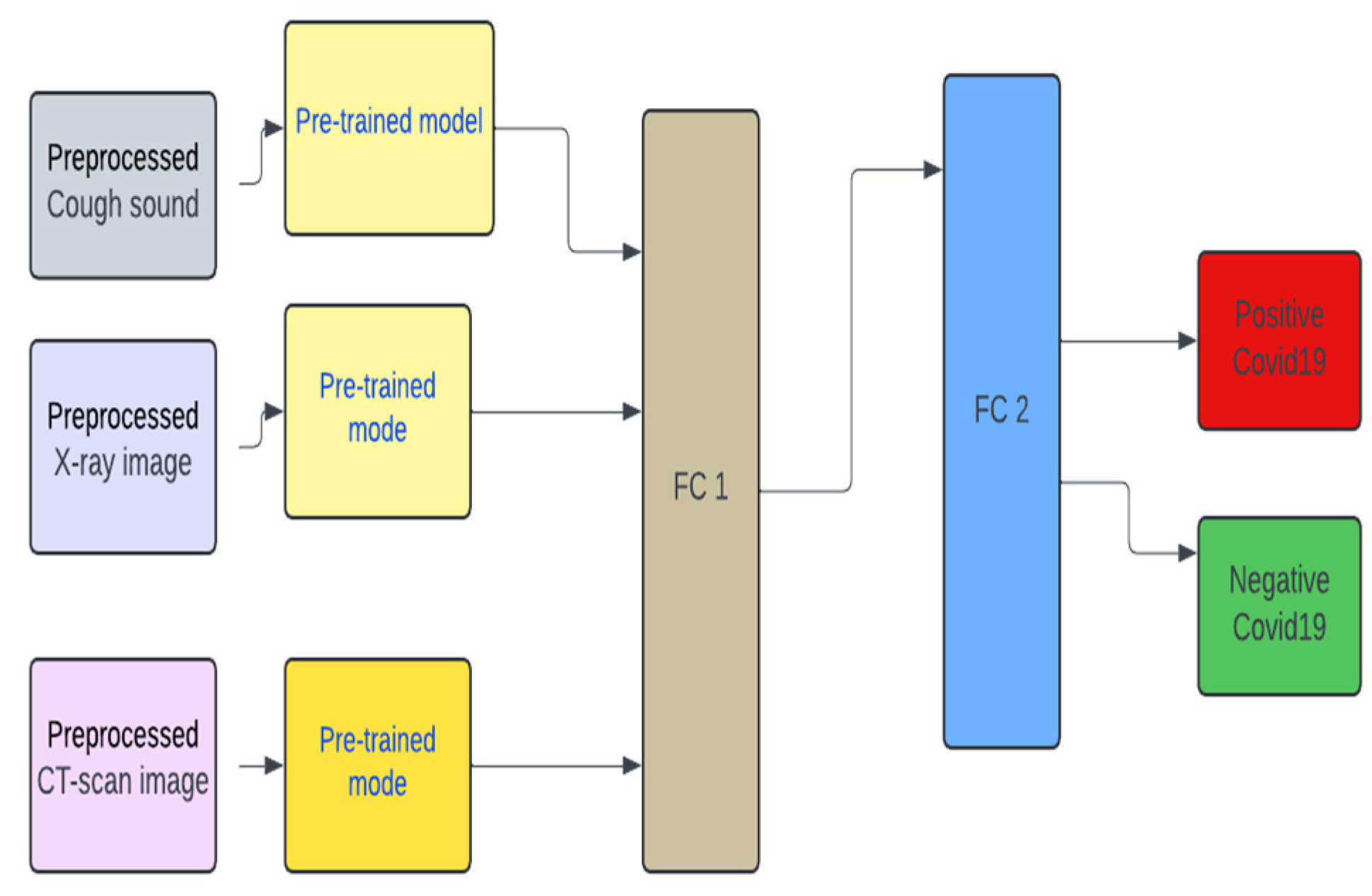

2.5. Unimodal Systems

To test the robustness of the multimodal design, we developed two different models for each dataset, one with a VGG19 pre-trained model (

Figure 4) and another without a pre-trained model (

Figure 3). We decided to concentrate on VGG19 as it is claimed in [

21] that its performance outperforms other pre-trained models. For the unimodal system in

Figure 3, for cough the T1 and T2 blocks replicate the C1 and C2 blocks in

Figure 1. Also, for the unimodal system for X-ray T1 and T2 replicates the X1 and X2 blocks. The same goes for the CT-scan - CT1 and CT2 for T1 and T2. Same as FC1 and FC2.

In

Figure 4, the pre-trained model is the VGG19. FC1 and FC2 reflect the same architecture as seen in

Figure 1. The training, and testing validation of the unimodal systems follow the same process prescribed for the multimodal systems, earlier. Except that the combination of datasets is not implemented.

2.6. Multimodal Pre-Trained Systems

Furthermore, we also developed a multimodal pre-trained model. We experimented on three pre-trained models – they are the VGG19, ResNET and MobileNetV2. We used these models as they are popular pre-trained models that have been used in the literature.

4. Results

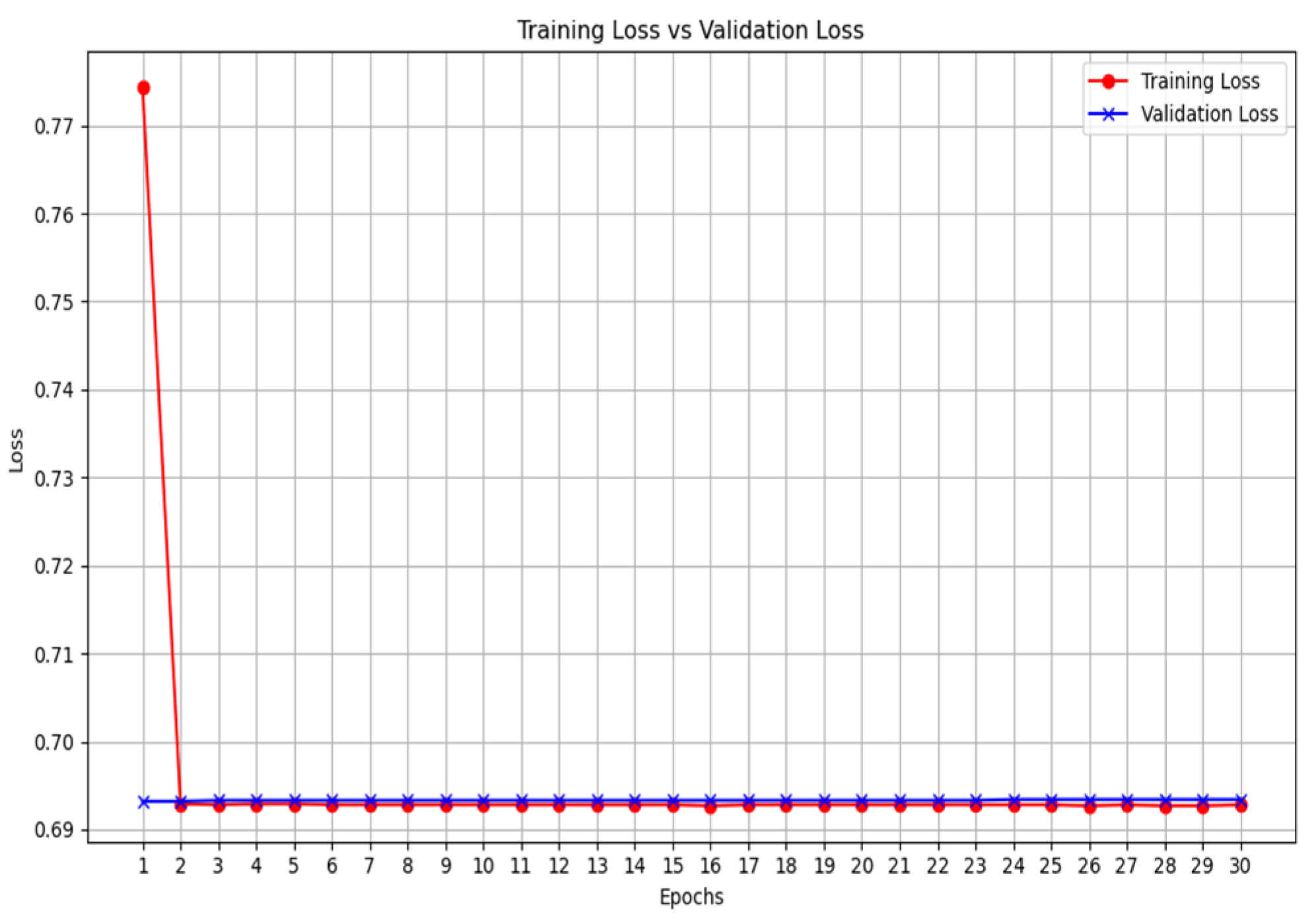

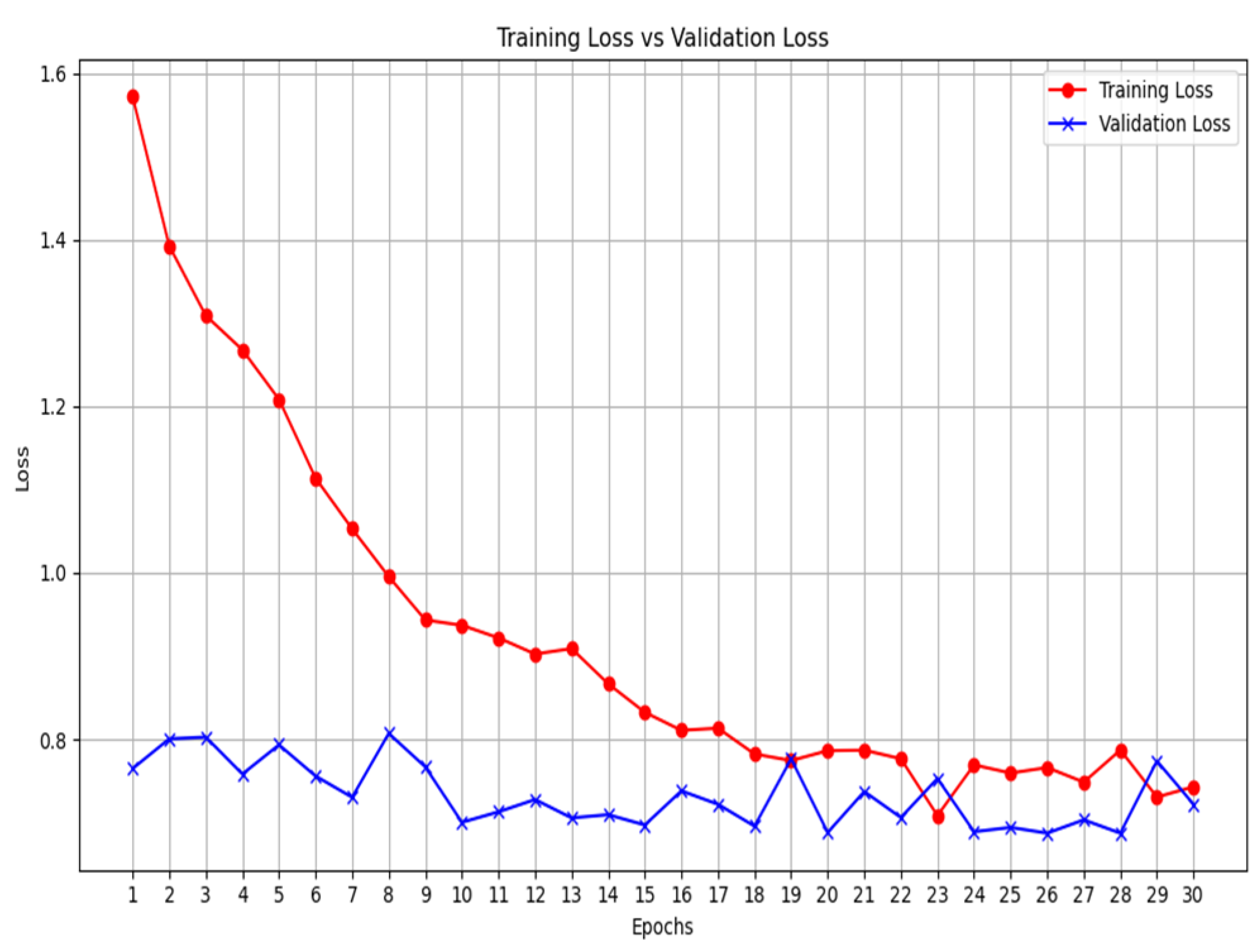

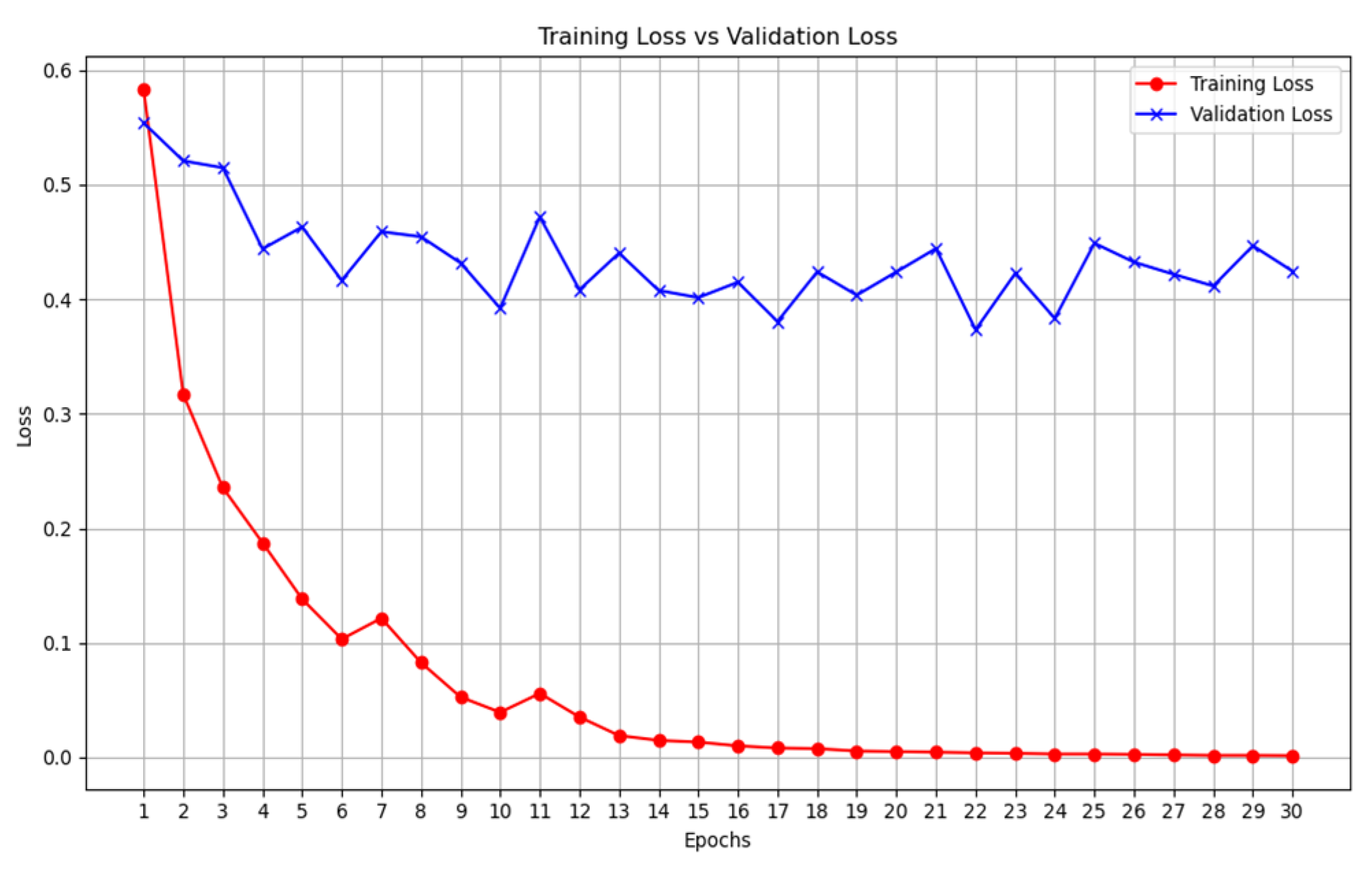

The results highlight several key insights into the use of deep learning models. First for the unimodal systems for cough, X-ray, and CT-scan. The result from

Table 1 shows the accuracy score as well as the F1-score of the unimodal system for cough. Looking at the graphs of the unimodal and pre-trained unimodal in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, it is observed that the cough with a pre-trained model improves the validation loss, as against the graph in

Figure 6 without a pre-trained model. It therefore means that the traditional deep learning model cannot learn the dataset patterns, hence the poor outcome. In

Table 2, there is an improved performance on the accuracy and the F1-score. This shows the importance of transfer learning on the cough dataset to deliver an improved outcome. The architectural complexity of the VGG-19 might have assisted in delivering an improved outcome.

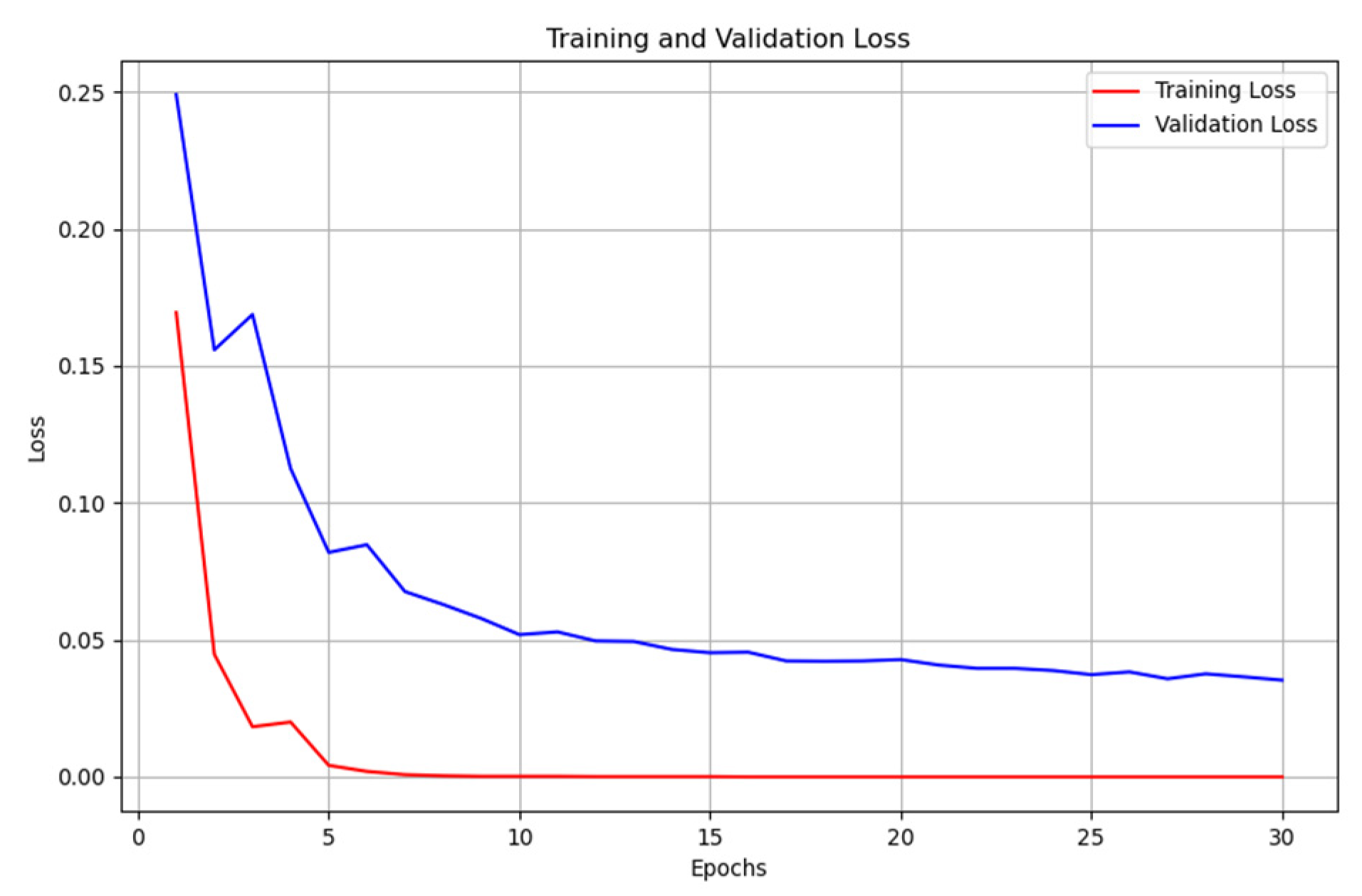

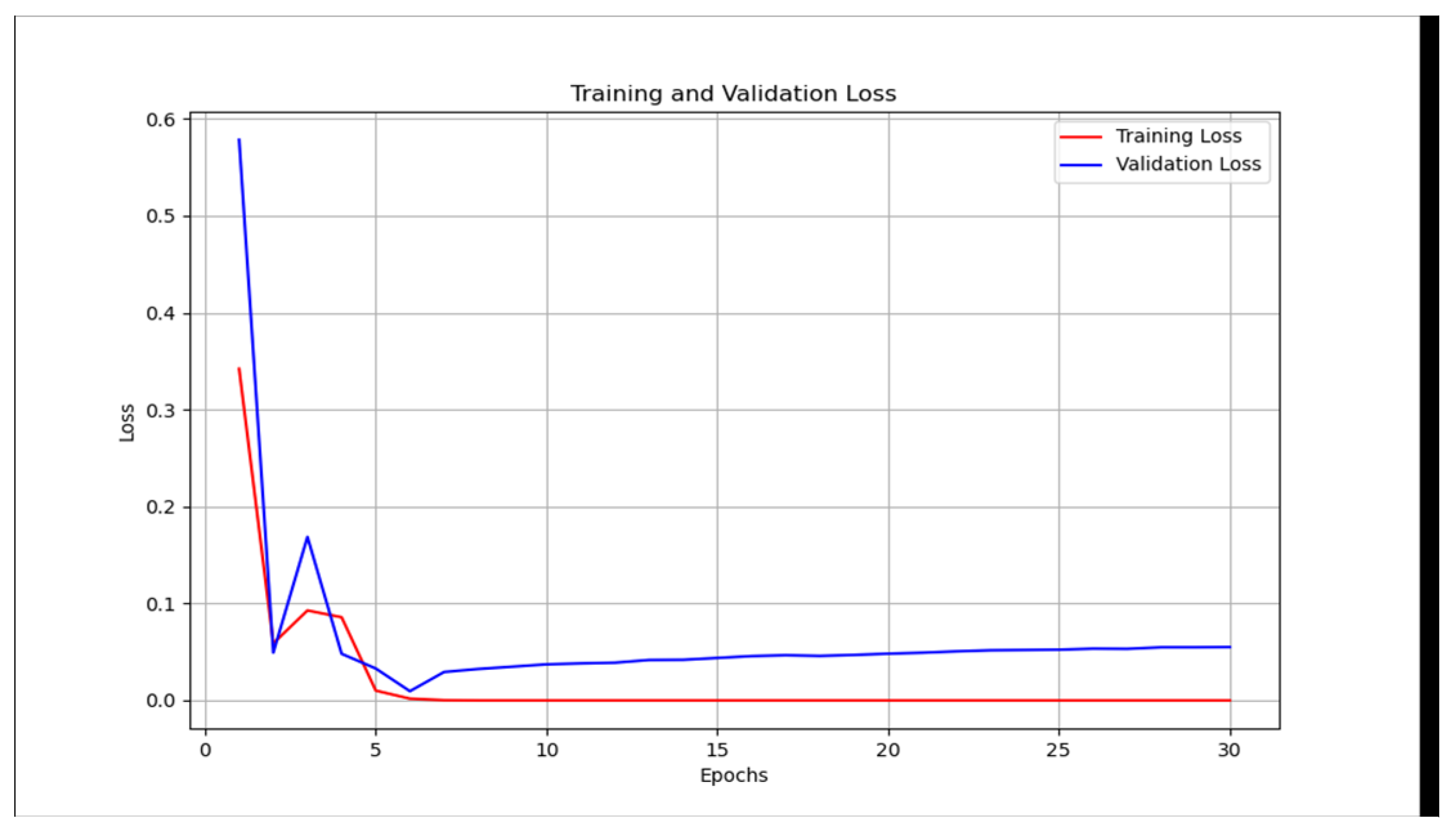

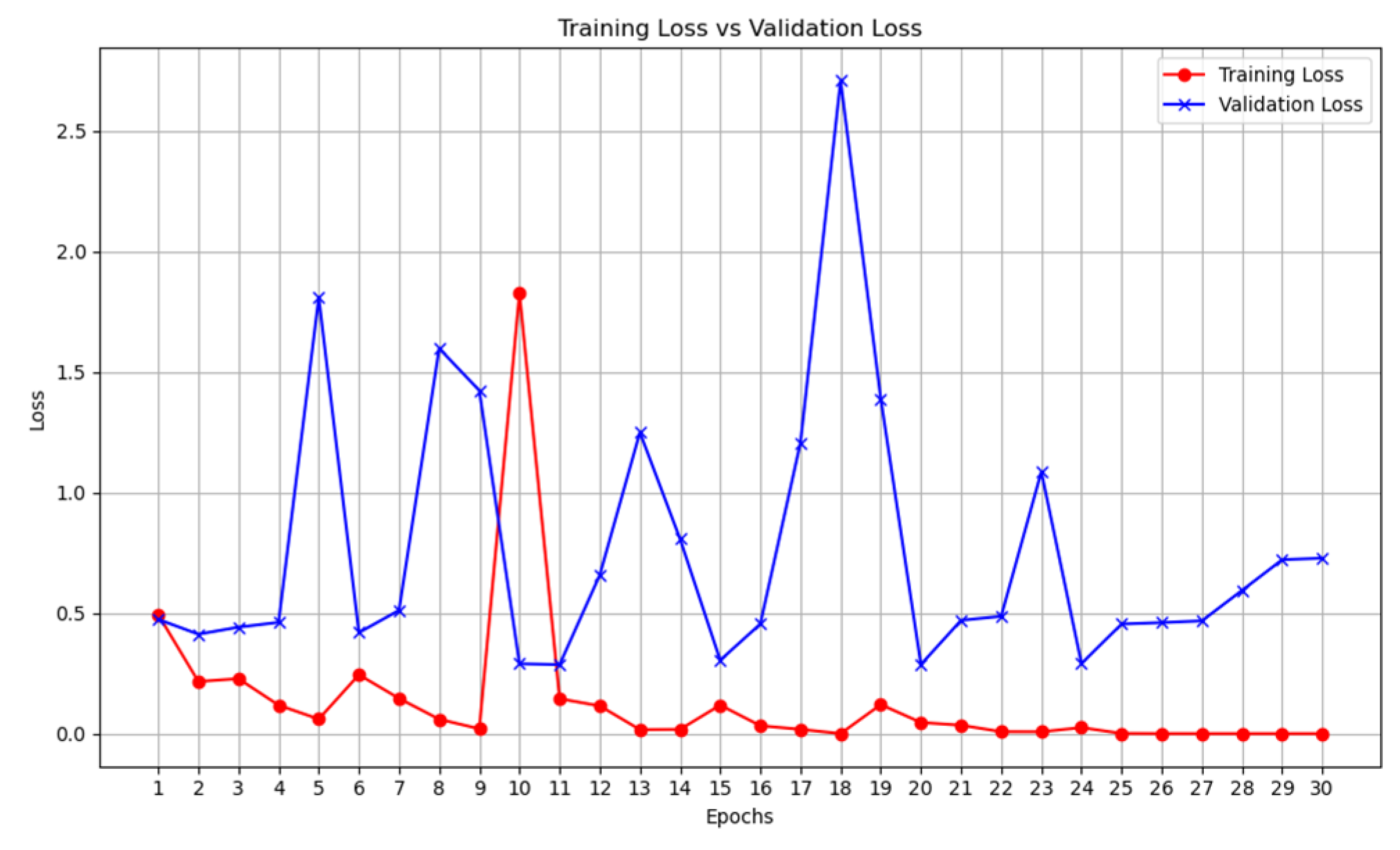

The same outcome is also recorded for unimodal deep learning system for X-ray,

Table 3 and

Table 4,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. The pre-trained model for the VGG-19 outperformed the traditional CNN deep learning model (

Table 3 and

Table 4). It can also be observed that the over-fitting is minimized as the training loss curve and the validation loss curve are relatively close.

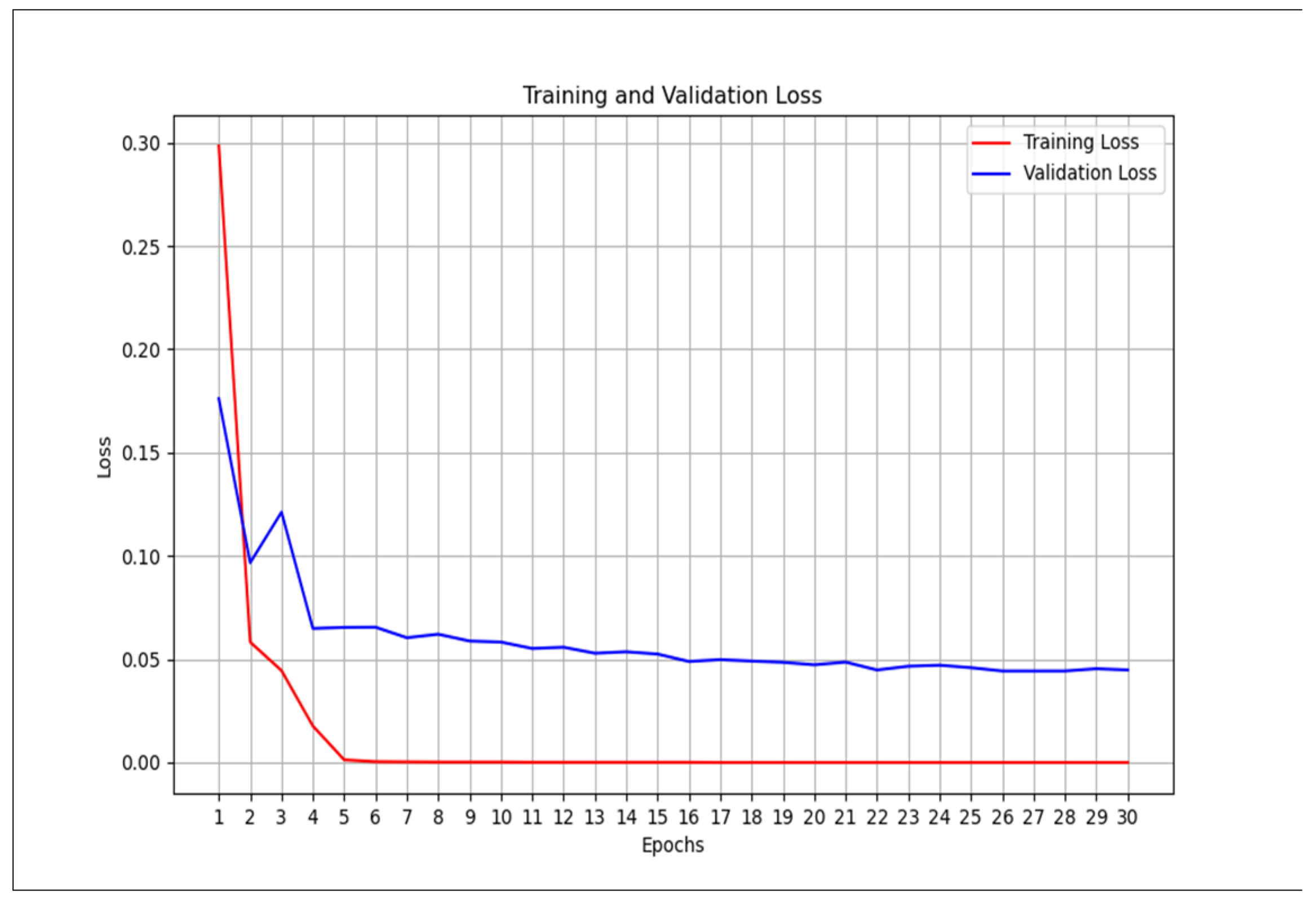

However, this is not the case for the CT scan. The traditional unimodal deep learning model outperformed the pre-trained unimodal for CT-scan (

Table 5 and

Table 6). An explanation to this could be that the images learned from the pre-trained model may not be useful in the CT-scan scenario. Even though the pre-trained model and the traditional model attempt to solve the over-fitting problem encountered during the training phase (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11).

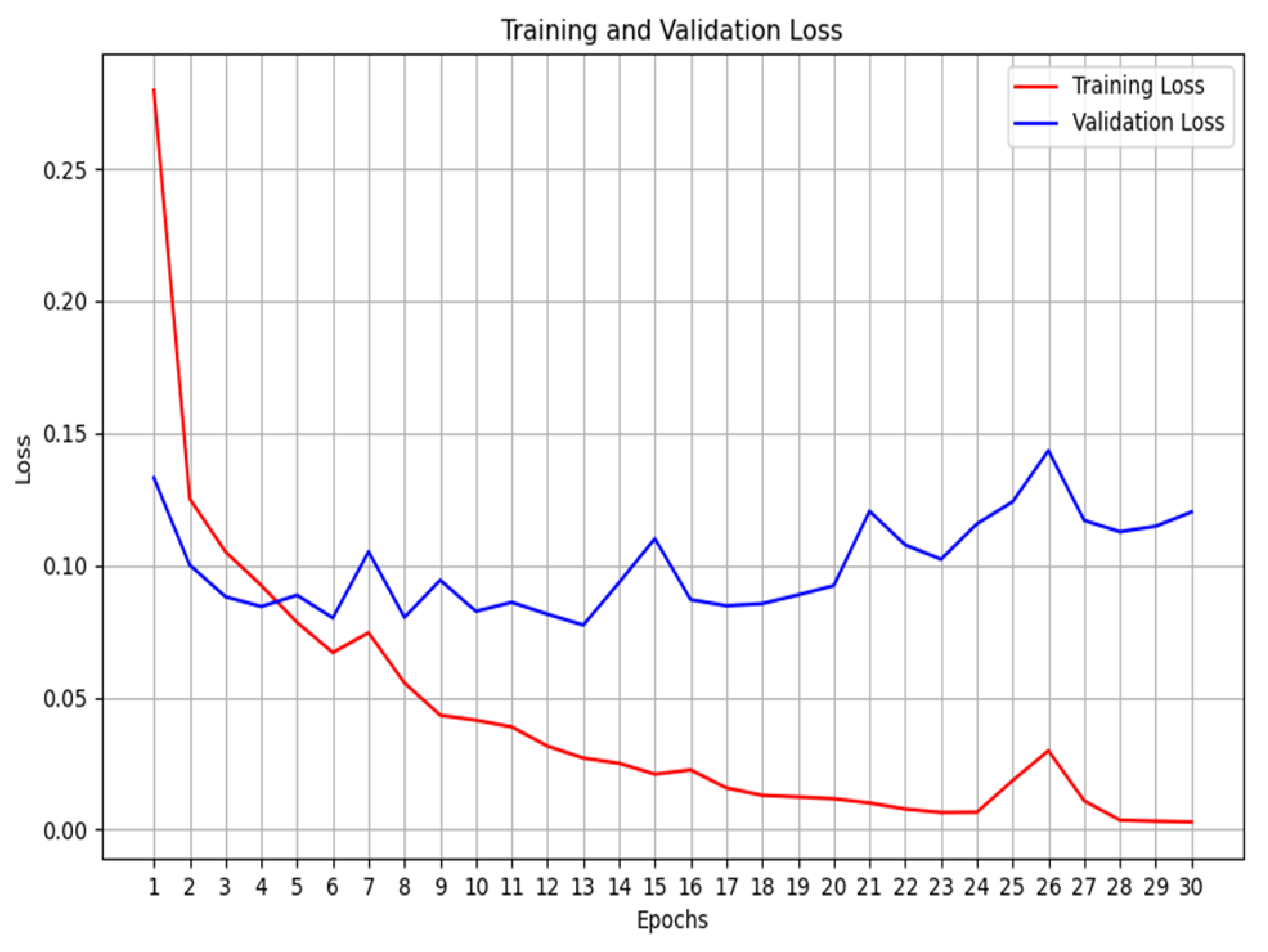

Moving on to multimodal systems (

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10), it is observed that the model that leveraged on a pre-trained model and that without a pre-trained model have the same accuracy value of 98% (

Table 7 vs

Table 8). However, using the F1-score, the non-pre-trained model outperformed the pre-trained model. An explanation for this could be that since the multimodal system has learned from three different datasets, it has aggregated complementary information from different datasets. As a result, it is possible to learn the unique attributes from these datasets to deliver an improved COVID-19 classification model. We also extended the experiment to two additional pre-trained models (ResNET and Mobilenetv2), in

Table 9 and

Table 10 however, they could not outperform the multimodal system developed without the pre-trained model.

Using the F1-score it is also true that the non-pre-trained multimodal performs better than the unimodal CT scan proposed by [

14] which gave an F1-score of 0.9731. The multimodal system, that we proposed, is enriched by learning from three diverse datasets. In addition, analyzing the training graphs (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13) shows that the non-pre-trained multimodal system (

Figure 12) exhibits less overfitting compared to the VGG19-based pre-trained multimodal.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.O., E.E. and M. C.; methodology, K.O., E.E. and M. C.; software, K.O., E.E..; validation, K.O., E.E. and M. C.; formal analysis, K.O., E.E..; investigation, K.O., E.E. and M. C.; resources, E.E. and M. C.; data curation, K.O., E.E. and M. C.; writing— K.O., E.E.; writing—review and editing, E.E. and M. C.; visualization, K.O., E.E. and M. C.; supervision, E.E. and M. C.; project administration, M. C.; funding acquisition, E.E. and M. C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Proposed multimodal architecture.

Figure 1.

Proposed multimodal architecture.

Figure 2.

Training, testing and validation configuration.

Figure 2.

Training, testing and validation configuration.

Figure 3.

Unimodal architecture used for Cough, X-ray, and CT-scan for COVID-19 classification.

Figure 3.

Unimodal architecture used for Cough, X-ray, and CT-scan for COVID-19 classification.

Figure 4.

Unimodal architecture with Pre-trained model (VGG19) used for Cough, X-ray, and CT-scan for COVID-19 classification.

Figure 4.

Unimodal architecture with Pre-trained model (VGG19) used for Cough, X-ray, and CT-scan for COVID-19 classification.

Figure 5.

Multimodal architecture with Pre-trained model (VGG19) used for Cough, X-ray, and CT-scan for COVID-19 classification.

Figure 5.

Multimodal architecture with Pre-trained model (VGG19) used for Cough, X-ray, and CT-scan for COVID-19 classification.

Figure 6.

Unimodal COVID-19 cough classification- training loss vs validation loss.

Figure 6.

Unimodal COVID-19 cough classification- training loss vs validation loss.

Figure 7.

Unimodal COVID-19 cough classification with VGG19 - training loss vs validation loss.

Figure 7.

Unimodal COVID-19 cough classification with VGG19 - training loss vs validation loss.

Figure 8.

Unimodal COVID-19 X-ray classification - training loss vs validation loss.

Figure 8.

Unimodal COVID-19 X-ray classification - training loss vs validation loss.

Figure 9.

Unimodal COVID-19 X-ray classification with VGG19 - training loss vs validation loss.

Figure 9.

Unimodal COVID-19 X-ray classification with VGG19 - training loss vs validation loss.

Figure 10.

Unimodal COVID-19 CT-scan classification - training loss vs validation loss.

Figure 10.

Unimodal COVID-19 CT-scan classification - training loss vs validation loss.

Figure 11.

Unimodal COVID-19 CT-scan classification with VGG19 - training loss vs validation loss.

Figure 11.

Unimodal COVID-19 CT-scan classification with VGG19 - training loss vs validation loss.

Figure 12.

Multimodal COVID-19 classification - training loss vs validation loss.

Figure 12.

Multimodal COVID-19 classification - training loss vs validation loss.

Figure 13.

Multimodal COVID-19 classification with VGG19 - training loss vs validation loss.

Figure 13.

Multimodal COVID-19 classification with VGG19 - training loss vs validation loss.

Table 1.

Evaluation for unimodal – Cough.

Table 1.

Evaluation for unimodal – Cough.

| Evaluation metrics |

Values |

| Accuracy |

50% |

| Sensitivity |

1 |

| Specificity |

0 |

| F1 Score |

0.6667 |

Confusion matrix

True Positives (TP)

True Negatives (TN)

False Positives (FP):

False Negatives (FN): |

[[0 100]

[0 100]]

100

0

100

0 |

Table 2.

Evaluation for unimodal – Cough VGG-19.

Table 2.

Evaluation for unimodal – Cough VGG-19.

| Evaluation metrics |

Values |

| Accuracy |

57.50% |

| Sensitivity |

0.69 |

| Specificity |

0.46 |

| F1 Score |

0.6188 |

Confusion matrix

True Positives (TP)

True Negatives (TN)

False Positives (FP):

False Negatives (FN): |

[[46 54]

[32 69]]

69

46

54

32 |

Table 3.

Evaluation for unimodal – X-ray.

Table 3.

Evaluation for unimodal – X-ray.

| Evaluation metrics |

Values |

| Accuracy |

98.00% |

| Sensitivity |

1 |

| Specificity |

0.960 |

| F1 Score |

0.9804 |

Confusion matrix

True Positives (TP)

True Negatives (TN)

False Positives (FP):

False Negatives (FN): |

[[96 4]

[0 100]]

100

96

4

0 |

Table 4.

Evaluation for unimodal – X-ray VGG-19.

Table 4.

Evaluation for unimodal – X-ray VGG-19.

| Evaluation metrics |

Values |

| Accuracy |

99.00% |

| Sensitivity |

1 |

| Specificity |

0.98 |

| F1 Score |

0.9901 |

Confusion matrix

True Positives (TP)

True Negatives (TN)

False Positives (FP):

False Negatives (FN): |

[[98 2]

[0 100]]

100

98

2

0 |

Table 5.

Evaluation for unimodal – CT-scan.

Table 5.

Evaluation for unimodal – CT-scan.

| Evaluation metrics |

Values |

| Accuracy |

91.00% |

| Sensitivity |

0.91 |

| Specificity |

0.91 |

| F1 Score |

0.91 |

Confusion matrix

True Positives (TP)

True Negatives (TN)

False Positives (FP):

False Negatives (FN): |

[[91 9]

[9 91]]

91

91

9

9 |

Table 6.

Evaluation for unimodal – CT-scan VGG-19.

Table 6.

Evaluation for unimodal – CT-scan VGG-19.

| Evaluation metrics |

Values |

| Accuracy |

77.50% |

| Sensitivity |

0.55 |

| Specificity |

1 |

| F1 Score |

0.7097 |

Confusion matrix

True Positives (TP)

True Negatives (TN)

False Positives (FP):

False Negatives (FN): |

[[100 0]

[45 55]]

55

100

0

45 |

Table 7.

Evaluation for multimodal.

Table 7.

Evaluation for multimodal.

| Evaluation metrics |

Values |

| Accuracy |

98.00% |

| Sensitivity |

1 |

| Specificity |

0.9600 |

| F1 Score |

0.9804 |

Confusion matrix

True Positives (TP)

True Negatives (TN)

False Positives (FP):

False Negatives (FN): |

[[96 4]

[0 100]]

100

96

4

0 |

Table 8.

Evaluation for multimodal –VGG19.

Table 8.

Evaluation for multimodal –VGG19.

| Evaluation metrics |

Values |

| Accuracy |

98.00 % |

| Sensitivity |

0.98 |

| Specificity |

0.98 |

| F1 Score |

0.980 |

Confusion matrix

True Positives (TP)

True Negatives (TN)

False Positives (FP):

False Negatives (FN): |

[[98 2]

[2 98]]

98

98

2

2 |

Table 9.

Evaluation for multimodal –RESNET.

Table 9.

Evaluation for multimodal –RESNET.

| Evaluation metrics |

Values |

| Accuracy |

50.00 % |

| Sensitivity |

1 |

| Specificity |

0 |

| F1 Score |

0.6667 |

Confusion matrix

True Positives (TP)

True Negatives (TN)

False Positives (FP):

False Negatives (FN): |

[[0 100]

[0 100]]

100

0

100

0 |

Table 10.

Evaluation for multimodal – MOBILENETV2.

Table 10.

Evaluation for multimodal – MOBILENETV2.

| Evaluation metrics |

Values |

| Accuracy |

96 % |

| Sensitivity |

0.96 |

| Specificity |

0.96 |

| F1 Score |

0.96 |

Confusion matrix

True Positives (TP)

True Negatives (TN)

False Positives (FP):

False Negatives (FN): |

[[96 4]

[4 96]]

96

96

4

4 |