Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

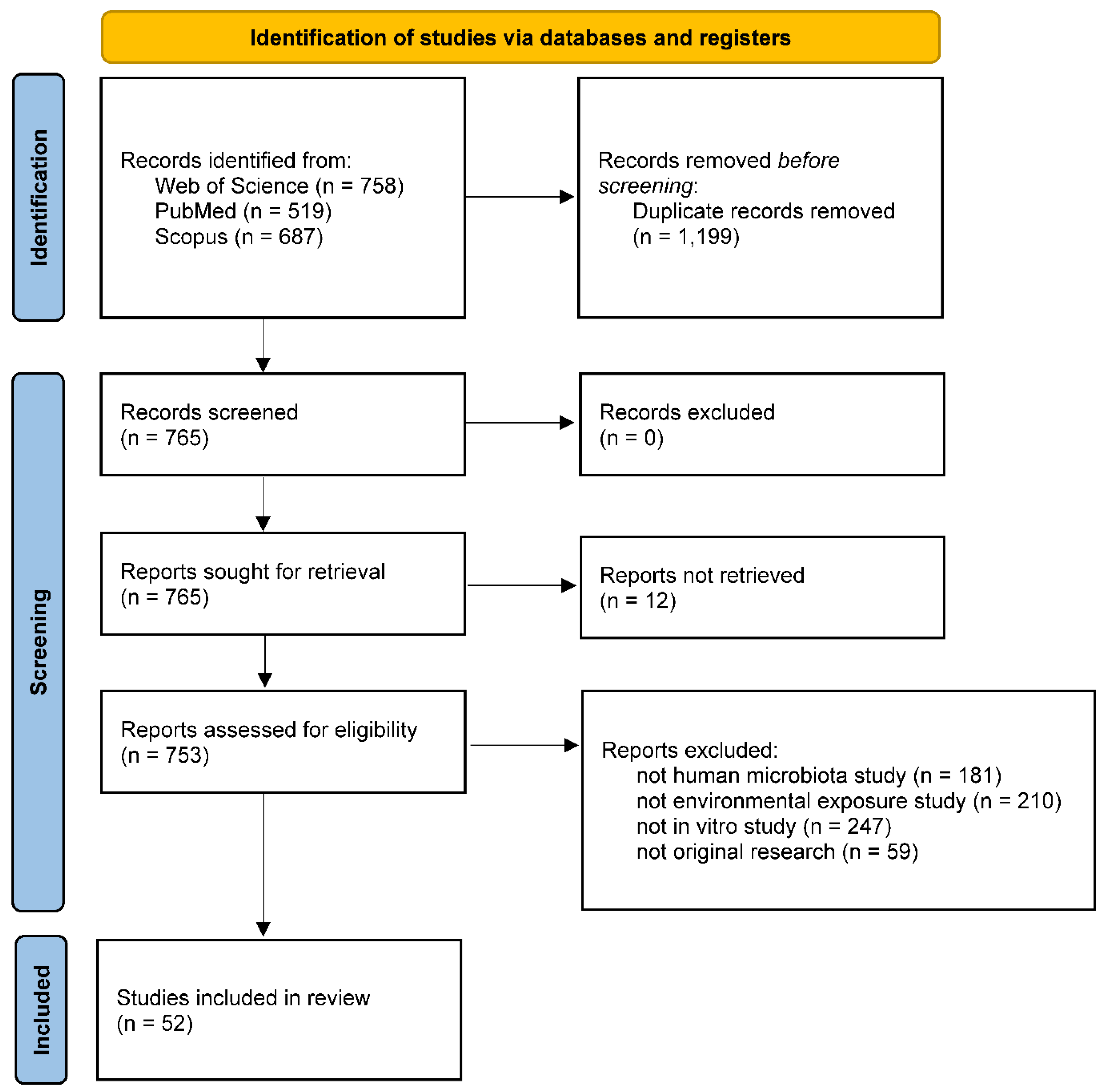

2. Methods

3. Gastrointestinal Tract Microbiota

| Exposure | In vitro model | Key findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral cavity | |||

| Sodium fluoride | Six-species biofilm on sintered hydroxyapatite disks |

Candida albicans (-) Actinomyces oris (-) Fusobacterium nucleatum (-) Streptococcus oralis (-) Streptococcus sobrinus (-) Veillonella dispar (-) |

[52] |

| Sodium fluoride | Saliva-derived mixed-species biofilm on saliva-coated human enamel discs |

Streptococcus mutans (↓) Streptococcus sanguinis (↓) |

[42] |

| Stannous fluoride, triclosan + sodium fluoride |

Saliva-derived mixed-species culture | Uncultured Veillonella sp. (↑) Bulleidia extructa (↑) Veillonella atypica and three Veillonella sp. (↓) |

[46] |

| Sodium fluoride + arginine | Saliva-derived mixed-species biofilm on saliva-coated human enamel discs |

Streptococcus mutans (↓) Streptococcus sanguinis (↑) |

[42] |

| Sodium fluoride + stannous chloride | Oral isolate single-species culture |

Enterobacter hormaechei (↓) Streptococcus salivarius (↓) Staphylococcus aureus (↓) Enterobacter cloacae (↓) Enterococcus faecalis (↓) Lactobacillus salivarius (↓) Candida albicans (↓) |

[49] |

| Stannous fluoride + zinc lactate | Saliva-derived mixed-species biofilm in hydroxyapatite disc reactors | Total facultative anaerobes (↓) Total anaerobes (-) Total streptococci (-) Total Gram-negative anaerobes (↓) |

[40] |

| Stannous fluoride + zinc lactate | Saliva-derived mixed-species biofilm in drip-flow biofilm reactors | Total facultative anaerobes (↓) Total anaerobes (↓) Total streptococci (↓) Total Gram-negative anaerobes (↓) |

[40] |

| Stannous fluoride + zinc lactate | Saliva-derived mixed-species biofilm in multiple sorbarod devices | Total facultative anaerobes (-) Total anaerobes (-) Total streptococci (-) Total Gram-negative anaerobes (↓) |

[40] |

| Triclosan | Saliva-derived mixed-species biofilm in hydroxyapatite disc reactors | Total facultative anaerobes (↓) Total anaerobes (↓) Total streptococci (↓) Total Gram-negative anaerobes (↓) |

[40] |

| Triclosan | Saliva-derived mixed-species biofilm in drip-flow biofilm reactors | Total facultative anaerobes (↓) Total anaerobes (↓) Total streptococci (↓) Total Gram-negative anaerobes (↓) |

[40] |

| Triclosan | Saliva-derived mixed-species biofilm in multiple sorbarod devices | Total facultative anaerobes (-) Total anaerobes (-) Total streptococci (↓) Total Gram-negative anaerobes (↓) |

[40] |

| Traditional Chinese medicinal toothpaste | Oral cavity-derived isolate single-species culture |

Enterobacter hormaechei (↓) Streptococcus salivarius (-) Staphylococcus aureus (↓) Enterobacter cloacae (-) Enterococcus faecalis (↓) Lactobacillus salivarius (-) Candida albicans (↓) |

[49] |

| Chlorhexidine | Single-species culture and biofilm in culture plates; dual-species culture and biofilm in culture plates |

Streptococcus mutans (↓) Candida albicans (-) Staphylococcus aureus (↓) Pseudomonas aeruginosa (↓) |

[54] |

| Chlorhexidine gluconate | Oral cavity-derived Candida albicans isolate single-species culture | Candida albicans (↓) | [53] |

| Essential oils | Mixed-species biofilm in culture plates, and plates supplemented with nylon fibers | Mixtures of 5-6 species selected from Actinomyces viscosus, Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus oralis, Streptococcus sanguinis, and Streptococcus salivarius (↓) | [50] |

| Essential oils | Single-species culture on agar plates |

Porphyromonas gingivalis (↓) Prevotella intermedia (↓) Fusobacterium nucleatum (↓) Staphylococcus aureus (↓) Streptococcus mutans (↓) |

[55] |

| Essential oils | Single-species culture on agar plates |

Streptococcus mutans (↓) Streptococcus sanguinis (↓) Staphylococcus aureus (↓) Candida albicans (↓) |

[56] |

| Hypochlorite nanobubbles | Saliva-derived mixed-species culture | Porphyromonas pasteri (↓) | [47] |

| Denture cleanser | Nine-species biofilm on polymethylmethacrylate discs | Total aerobes (↓) Total anaerobes (↓) Candida (↓) |

[57] |

| Copper oxide nanoparticles, zinc oxide nanoparticles | Teeth crown surface-derived mixed-species culture | Total bacterial counts (↓) | [39] |

| Tetracycline | Saliva-derived mixed-species biofilm in Constant Depth Film Fermenters | Total anaerobic count (↓) Lactobacillus (-) Streptococcus (↓) Actinomyces (↓) |

[41] |

| Ampicillin | Saliva-derived mixed-species biofilm in culture plates pre-coated with saliva pellicle |

Veillonella atypica (↑) Veillonella infantium (↑) Veillonella dispar (↑) Veillonella parvula (↓) Prevotella jejuni (↑) Prevotella histicola (↑) Prevotella salivae (↑) Prevotella melaninogenica (↑) Streptococcus oralis (↓) Streptococcus mitis (↓) Streptococcus parasanguinis (↓) Streptococcus sanguinis (↓) Streptococcus salivarius (↑) Streptococcus pneumoniae (-) Staphylococcus aureus (-) |

[43] |

| Amoxicillin | Saliva-derived mixed-species biofilm in culture plates | Total viable cells (-) Streptococcus salivarius (↑) Streptococcus pneumoniae (↑) Lactobacillus fermentum (↓) |

[44] |

| Cigarette smoke | Mixed-species biofilm in sintered hydroxyapatite disc reactors | Fusobacterium nucleatum (↑) | [51] |

| Nonnutritive sweeteners | Single-species culture and biofilm in culture plates; dual-species biofilm on glass coverslips pre-coated with saliva; saliva-derived mixed-species biofilm on glass coverslips pre-coated with saliva |

Streptococcus sanguinis (↓) Streptococcus mutans (↓) Streptococcus mutans/Streptococcus sanguinis ratio (↓) |

[48] |

| Gamma radiation | Single-species culture and biofilm in culture plates |

Candida albicans (-) Candida albicans (-) Streptococcus salivarius (-) Klebsiella oxytoca (↓) |

[58] |

| Heavy ion radiation | Single-, dual-, and saliva-derived mixed-species culture |

Streptococcus (↑) Streptococcus mutans/ Streptococcus sanguinis ratio (↑) |

[45] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Porphyromonas gingivalis, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Actinomyces odontilyticus single-species culture supernatant, co-cultured with ACE2+ 293T cells | SARS-CoV-2 pseudoviral infection (↓) | [59] |

| Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) | Streptococcus sanguinis and Akata cell co-culture | EBV lytic activation (↑) | [60] |

| Stomach | |||

| pH (6.0 to 3.0) | Eleven-species culture in chemostats |

Candida (-) Lactobacillus (-) Escherichia (↓) Klebsiella (↓) |

[61] |

| Small intestine | |||

| Bacteriophage cocktail | Seven-species culture in the Smallest Intestine (TSI) model inoculated with Listeria monocytogenes |

Streptococcus (-) Enterococcus faecalis (-) Listeria monocytogenes (↓) Escherichia coli (-) |

[70] |

| Ampicillin | Seven-species culture in the Smallest Intestine (TSI) model inoculated with Listeria monocytogenes |

Streptococcus (-) Enterococcus faecalis (↓) Listeria monocytogenes (-) Escherichia coli (↓) |

[70] |

| Large intestine | |||

| Reviews on types of in vitro models | [24,25,26,31] | ||

| Reviews including exposure-microbiota interactions using in vitro models: | |||

| Heavy metals | [8,9] | ||

| Antibiotics | [10,11] | ||

| Nanomaterials | [32,33] | ||

| Persistent organic pollutants | [12,13] | ||

| Food additives | [34,35] | ||

| Pathogens | [20,36] | ||

| Exposure | In vitro model | Key findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory tract | |||

| Fluoroquinolone, meticillin,penicillin, oxacillin, kanamycin, tobramycin, gentamicin, erythromycin, lincomycin, tetracycline, fusidic acid, fosfomycin, rifampicin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | Nose-derived Staphylococcus isolates on agar plates | 87 out of 88 fluoroquinolone-resistant staphylococci carried co-resistance, and 75 carried co-resistance specifically to meticillin | [72] |

| Penicillin, cefoxitin | Nose-derived Staphylococcus isolates on agar plates | 24 out of 27 Staphylococcus carried resistance to penicillin and/or cefoxitin | [77] |

| Ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, ampicillin-sulbactam, cefuroxime, cefotaxime, imipenem, meropenem, azithromycin, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, thrimetoprim-sulfametoxazole | Throat- and nose-derived Haemophilus parainfluenzae isolates on agar plates | Isolates showed different resistance patterns based on two different guidelines | [78] |

| Ceftazidime, amoxicillin, cefotaxime, ceftazidime | Respiratory tract-derived Prevotella isolates on agar plates | 38 out of 50 Prevotella isolates produced extended-spectrum β-lactamases and had higher resistance to amoxicillin and ceftazidime | [73] |

| Supplemental oxygen | Sputum-derived mixed-species culture |

Candida albicans (↓) Aspergillus fumigatus (↓) Actinomyces oris (↓) Schaalia odontolytica (↓) Rothia mucilaginosa (↓) Multiple Streptococcus species (↓) Pseudomonas aeruginosa (-) Staphylococcus aureus (-) |

[79] |

| Human rhinovirus (HRV) | Corynebacterium, Haemophilus influenzae, Calu-3 cell co-culture in the air-liquid interface (ALI) model | HRV copy number (↓) by Corynebacterium pseudodiphtheriticum + Haemophilus influenzae | [71] |

| Skin | |||

| Cosmetics | Staphylococcus epidermidis single-species culture | Yields of short-chain fatty acids depended on different cosmetics | [82] |

| Ultraviolet (UV) filters in sunscreens | Lactobacillus crispatus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Cutibacterium acnes single-species culture in a culture plate exposure to UV light |

Lactobacillus crispatus (↑) Cutibacterium acnes (↓) |

[83] |

| Octocrylene | Skin-derived single-species culture | Deinococcus grandis and Stenotrophomonas metabolized octocrylene | [84] |

| Ultraviolet radiation (UVR) | Sphingomonas mucosissima single-species culture on agar plates | Sphingomonas mucosissima was resistant to UVR | [85] |

| Mycolactones | Skin-derived single-species fungal spores on agar plates |

Aspergillus flavus (↑) Aspergillus niger (↑) Penicillium rubens (↓) |

[86] |

| Benzo[a]pyrene | Skin-derived Micrococcus luteus and Pseudomonas oleovorans co-culture in a microbially competent three-dimensional skin model | Benzo[a]pyrene degradation to various metabolites | [80] |

| Methyl Red, Orange II | Single-species culture |

Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, Micrococcus, Dermacoccus, and Kocuria species metabolized Methyl Red with various rates, and all but Corynebacterium xerosis metabolized Orange II |

[87] |

| Doxycycline, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, cefalexin, amoxicillin, trimethoprim, clarithromycin, linezolid, metronidazole, azithromycin, co-amoxiclav | Staphylococcus epidermidis single-species culture on agar plates | Staphylococcus epidermidis exhibited resistance to various antibiotics, and antibiotic-adapted strains showed cross-resistance | [88] |

| Green tea extracts | Single-species culture on agar plates |

Micrococcus luteus (↓) Staphylococcus epidermidis (↓) Clostridium xerosis (↓) Bacillus subtilis (↓) |

[89] |

| Vagina | |||

| Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) | Vagina-derived single species or mixed species co-cultured with vaginal epithelial cells and HIV-1-susceptible cells in the air-liquid interface (ALI) model | HIV-1 replication (↓) by Lactobacillus iners and group B streptococcus-dominated culture | [93] |

| Zika virus (ZIKV), Herpes Simplex Virus type 2 (HSV-2) | Vagina-derived single species or mixed species co-cultured with vaginal epithelial cells in the air-liquid interface (ALI) model | ZIKV titers (↓) by Staphylococcus epidermidis-dominated culture ZIKV titers (↑) by Lactobacillus crispatus-dominated culture HSV- HSV-2 (↑) by Lactobacillus jensenii-dominated, Mobiluncus mulieris-containing culture |

[96] |

| Human vaginal pathogens including Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Streptococcus agalactiae, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Gardnerella vaginalis, and Mobiluncus curtisii | Lactobacillus single-species culture on agar plates | Pathogens (↓) by Lactobacillus species except for L. iners, with strain-specific differences | [97] |

| Human vaginal pathogens including Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus, and Candida albicans | Vagina-derived Lactobacillus single-species culture on agar plates | Pathogens (↓), with strain-specific differences | [98] |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | Streptococcus agalactiae and Lactobacillus iners single-species culture |

Lactobacillus iners upon exposure (↓), 6 hours later (-) Streptococcus agalactiae (↑) |

[99] |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Vagina-derived Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus single-species culture | Mycobacterium tuberculosis (↓) | [100] |

| Gardnerella | Vagina-derived mixed-species culture on agar plates | Gardnerella (↓) | [101] |

| Metronidazole | Lactobacillus crispatus, Lactobacillus iners, Gardnerella vaginalis, Prevotella bivia, and Atopobium vaginae co-culture |

Gardnerella vaginalis (↓) Prevotella bivia (↓) Atopobium vaginae (↓) Lactobacillus crispatus (-) Lactobacillus iners (-) |

[94] |

| Metronidazole | Gardnerella vaginalis and Lactobacillus iners co-culture | Gardnerella vaginalis (-) due to metronidazole sequestration by Lactobacillus iners | [90] |

| Metronidazole, clindamycin | Vagina-derived Bifidobacterium single-species culture on agar plates | Bifidobacterium exhibited different susceptibility to metronidazole and clindamycin, with species-specific patterns | [95] |

| β-lactamines, aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, macrolides, glycopeptides, sulfamides, diaminopyrimidine, rifamycines, aminosides | Vagina-derived Lactobacillus single-species culture on agar plates | Lactobacillus showed species- and strain-dependent antibiotic resistance patterns | [98] |

| Clindamycin, erythromycin, metronidazole, tinidazole, dequalinium | Gardnerella vaginalis single-species culture | Gardnerella vaginalis showed strain-dependent antibiotic resistance patterns | [102] |

| Tea tree oil | Vagina-derived single-species culture |

Candida (↓) at low oil concentration Bifidobacterium (↓) at intermediate concentration |

[103] |

|

Lactobacillus (↓) at high concentration |

|||

| Vaginal douche products | Lactobacillus single-species culture | Lactobacillus (↓) | [104] |

3.1. Oral Microbiota

3.2. Gastric and Small Intestinal Microbiota

4. Extraintestinal Microbiota

4.1. Respiratory Microbiota

4.2. Skin Microbiota

4.3. Vaginal Microbiota

5. Advantages of Utilizing In Vitro Models to Understand Exposure-Microbiota Interactions

6. Opportunities for Improvement and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.-X.; Chen, X.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in Health and Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thursby, E.; Juge, N. Introduction to the Human Gut Microbiota. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 1823–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieterich, W.; Schink, M.; Zopf, Y. Microbiota in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamont, R.J.; Koo, H.; Hajishengallis, G. The Oral Microbiota: Dynamic Communities and Host Interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, A.L.; Belkaid, Y.; Segre, J.A. The Human Skin Microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, M.; Alizadeh, M.; Brown, S.; Ma, B.; Ravel, J. Towards a Deeper Understanding of the Vaginal Microbiota. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutvirtz, G.; Sheiner, E. Airway Pollution and Smoking in Reproductive Health. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 85, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giambò, F.; Italia, S.; Teodoro, M.; Briguglio, G.; Furnari, N.; Catanoso, R.; Costa, C.; Fenga, C. Influence of Toxic Metal Exposure on the Gut Microbiota (Review). World Acad. Sci. J. 2021, 3, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Yu, L.; Tian, F.; Zhai, Q.; Fan, L.; Chen, W. Gut Microbiota: A Target for Heavy Metal Toxicity and a Probiotic Protective Strategy. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 742, 140429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadighara, P.; Rostami, S.; Shafaroodi, H.; Sarshogi, A.; Mazaheri, Y.; Sadighara, M. The Effect of Residual Antibiotics in Food on Intestinal Microbiota: A Systematic Review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman-Rodriguez, M.; McDonald, J.A.K.; Hyde, R.; Allen-Vercoe, E.; Claud, E.C.; Sheth, P.M.; Petrof, E.O. Using Bioreactors to Study the Effects of Drugs on the Human Microbiota. Methods 2018, 149, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.; Li, G.; Yang, Y.; Yu, Y. A Review on in-Vitro Oral Bioaccessibility of Organic Pollutants and Its Application in Human Exposure Assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 752, 142001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsiaoussis, J.; Antoniou, M.N.; Koliarakis, I.; Mesnage, R.; Vardavas, C.I.; Izotov, B.N.; Psaroulaki, A.; Tsatsakis, A. Effects of Single and Combined Toxic Exposures on the Gut Microbiome: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Toxicol. Lett. 2019, 312, 72–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimkaite, L.; Liveikis, T.; Kaspute, G.; Armalyte, J.; Aldonyte, R. Air Pollution-Associated Shifts in the Human Airway Microbiome and Exposure-Associated Molecular Events. Future Microbiol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulliero, A.; Traversi, D.; Franchitti, E.; Barchitta, M.; Izzotti, A.; Agodi, A. The Interaction among Microbiota, Epigenetic Regulation, and Air Pollutants in Disease Prevention. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Średnicka, P.; Juszczuk-Kubiak, E.; Wójcicki, M.; Akimowicz, M.; Roszko, M.Ł. Probiotics as a Biological Detoxification Tool of Food Chemical Contamination: A Review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 153, 112306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, P.; Shokrzadeh, M.; Raeisi, S.N.; Ghorbani-HasanSaraei, A.; Nasiraii, L.R. Aflatoxins Biodetoxification Strategies Based on Probiotic Bacteria. Toxicon 2020, 178, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Flores, G.; Pickard, J.M.; Núñez, G. Microbiota-Mediated Colonization Resistance: Mechanisms and Regulation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Bai, Y.; Zha, L.; Ullah, N.; Ullah, H.; Shah, S.R.H.; Sun, H.; Zhang, C. Mechanism of the Gut Microbiota Colonization Resistance and Enteric Pathogen Infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvigioni, M.; Mazzantini, D.; Celandroni, F.; Ghelardi, E. Animal and In Vitro Models as Powerful Tools to Decipher the Effects of Enteric Pathogens on the Human Gut Microbiota. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Franklin, C.L.; Ericsson, A.C. Consideration of Gut Microbiome in Murine Models of Diseases. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.A.; Beasley, D.E.; Dunn, R.R.; Archie, E.A. Lactobacilli Dominance and Vaginal pH: Why Is the Human Vaginal Microbiome Unique? Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, S.; Yeoman, C.J.; Janga, S.C.; Thomas, S.M.; Ho, M.; Leigh, S.R.; Consortium, P.M.; White, B.A.; Wilson, B.A.; Stumpf, R.M. Primate Vaginal Microbiomes Exhibit Species Specificity without Universal Lactobacillus Dominance. ISME J. 2014, 8, 2431–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Ahlawat, S.; Sharma, K.K. Culturing the Unculturables: Strategies, Challenges, and Opportunities for Gut Microbiome Study. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 134, lxad280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenring, J.; Bircher, L.; Geirnaert, A.; Lacroix, C. In Vitro Human Gut Microbiota Fermentation Models: Opportunities, Challenges, and Pitfalls. Microbiome Res. Rep. 2023, 2, N. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Yu, L.; Tian, F.; Zhao, J.; Zhai, Q. In Vitro Models to Study Human Gut-Microbiota Interactions: Applications, Advances, and Limitations. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 270, 127336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.N.; Oulhote, Y.; Weihe, P.; Wilkinson, J.E.; Ma, S.; Zhong, H.; Li, J.; Kristiansen, K.; Huttenhower, C.; Grandjean, P. Effects of Lifetime Exposures to Environmental Contaminants on the Adult Gut Microbiome. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignal, C.; Guilloteau, E.; Gower-Rousseau, C.; Body-Malapel, M. Review Article: Epidemiological and Animal Evidence for the Role of Air Pollution in Intestinal Diseases. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 757, 143718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated Guidance and Exemplars for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagini, F.; Daddi, C.; Calvigioni, M.; De Maria, C.; Zhang, Y.S.; Ghelardi, E.; Vozzi, G. Designs and Methodologies to Recreate in Vitro Human Gut Microbiota Models. Bio-Des. Manuf. 2023, 6, 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utembe, W.; Tlotleng, N.; Kamng’ona, A. A Systematic Review on the Effects of Nanomaterials on Gut Microbiota. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2022, 3, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojciechowska, O.; Costabile, A.; Kujawska, M. The Gut Microbiome Meets Nanomaterials: Exposure and Interplay with Graphene Nanoparticles. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 6349–6364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Qu, R.; Li, M.; Sheng, P.; Jin, L.; Huang, X.; Xu, Z.Z. Impacts of Food Additives on Gut Microbiota and Host Health. Food Res. Int. 2024, 196, 114998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Liu, H.; Qin, N.; Ren, X.; Zhu, B.; Xia, X. Impact of Food Additives on the Composition and Function of Gut Microbiota: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 99, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, S.L.; Peña-Díaz, J.; Finlay, B.B. Chemical Communication in the Gut: Effects of Microbiota-Generated Metabolites on Gastrointestinal Bacterial Pathogens. Anaerobe 2015, 34, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewhirst, F.E.; Chen, T.; Izard, J.; Paster, B.J.; Tanner, A.C.R.; Yu, W.-H.; Lakshmanan, A.; Wade, W.G. The Human Oral Microbiome. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 5002–5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio-Maia, B.; Caldas, I.M.; Pereira, M.L.; Pérez-Mongiovi, D.; Araujo, R. Chapter Four - The Oral Microbiome in Health and Its Implication in Oral and Systemic Diseases. In Advances in Applied Microbiology; Sariaslani, S., Michael Gadd, G., Eds.; Academic Press, 2016; Vol. 97, pp. 171–210.

- Tabrez Khan, S.; Ahamed, M.; Al-Khedhairy, A.; Musarrat, J. Biocidal Effect of Copper and Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles on Human Oral Microbiome and Biofilm Formation. Mater. Lett. 2013, 97, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledder, R.G.; McBain, A.J. An in Vitro Comparison of Dentifrice Formulations in Three Distinct Oral Microbiotas. Arch. Oral Biol. 2012, 57, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ready, D.R. Antibiotic and mercury resistance in the cultivable oral microbiota of children. Ph.D., University of London, University College London, 2005.

- Zheng, X.; He, J.; Wang, L.; Zhou, S.; Peng, X.; Huang, S.; Zheng, L.; Cheng, L.; Hao, Y.; Li, J.; et al. Ecological Effect of Arginine on Oral Microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brar, N.K.; Dhariwal, A.; Åmdal, H.A.; Junges, R.; Salvadori, G.; Baker, J.L.; Edlund, A.; Petersen, F.C. Exploring Ex Vivo Biofilm Dynamics: Consequences of Low Ampicillin Concentrations on the Human Oral Microbiome. Npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brar, N.K.; Dhariwal, A.; Shekhar, S.; Junges, R.; Hakansson, A.P.; Petersen, F.C. HAMLET, a Human Milk Protein-Lipid Complex, Modulates Amoxicillin Induced Changes in an Ex Vivo Biofilm Model of the Oral Microbiome. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, G.; Zhou, X.; Peng, X.; Li, M.; Zhang, M.; Lu, D.; Yang, D.; Cheng, L.; Ren, B. Heavy Ion Radiation Directly Induced the Shift of Oral Microbiota and Increased the Cariogenicity of Streptococcus Mutans. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e01322–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glancey, A.S.G. Selection, interaction and adaptation in the oral microbiota. Ph.D., The University of Manchester, 2011.

- Sagara, K.; Kataoka, S.; Yoshida, A.; Ansai, T. The Effects of Exposure to O2- and HOCl-Nanobubble Water on Human Salivary Microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Xi, R.; Li, Y.; Peng, X.; Xu, X.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, X. The Effects of Nonnutritive Sweeteners on the Cariogenic Potential of Oral Microbiome. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 9967035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, Q.; Gao, Y.; Qin, T.; Wang, S.; Shi, Y.; Chen, T. Interaction of Oral and Toothbrush Microbiota Affects Oral Cavity Health. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aires, A.; Barreto, A.S.; Semedo-Lemsaddek, T. Antimicrobial Effects of Essential Oils on Oral Microbiota Biofilms: The Toothbrush In Vitro Model. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S.M. Relative Contributions of Tobacco Associated Factors and Diabetes to Shaping the Oral Microbiome. Ph.D., 2018.

- Thurnheer, T.; Belibasakis, G.N. Effect of Sodium Fluoride on Oral Biofilm Microbiota and Enamel Demineralization. Arch. Oral Biol. 2018, 89, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellepola, A.; Samaranayake, L. The Effect of Brief Exposure to Sub-Therapeutic Concentrations of Chlorhexidine Gluconate on the Germ Tube Formation of Oral Candida Albicans and Its Relationship to Post-Antifungal Effect. Oral Dis. 2000, 6, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, P.J. Interaction of the Oral Microbiota with Respiratory Pathogens in Biofilms of Mechanically Ventilated Patients. Ph.D., Cardiff University, 2017.

- Kalra, K.; Vasthare, R.; Shenoy, P.A.; Vishwanath, S.; Singhal, D.K. Antibacterial Efficacy of Essential Oil of Two Different Varieties of Ocimum (Tulsi) on Oral Microbiota—An Invitro Study. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2019, 10, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somantri, R.U.; Sugiarto; Iriani, E. S.; Sunarti, T.C. In Vitro Study on the Antimicrobial Activity of Eleven Essential Oils against Oral Cavity Microbiota. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1063, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, L.E. The Impact of Denture Related Disease on the Oral Microbiome of Denture Wearers. Ph.D., University of Glasgow, 2016.

- Vanhoecke, B.W.; De Ryck, T.R.; De boel, K.; Wiles, S.; Boterberg, T.; Van de Wiele, T.; Swift, S. Low-Dose Irradiation Affects the Functional Behavior of Oral Microbiota in the Context of Mucositis. Exp. Biol. Med. 2016, 241, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bontempo, A.; Chirino, A.; Heidari, A.; Lugo, A.; Shindo, S.; Pastore, M.R.; Madonia, R.; Antonson, S.A.; Godoy, C.; Nichols, F.C.; et al. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Porphyromonas Gingivalis and the Oral Microbiome. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Zhang, J.-B.; Lu, L.-X.; Jia, Y.-J.; Zheng, M.-Q.; Debelius, J.W.; He, Y.-Q.; Wang, T.-M.; Deng, C.-M.; Tong, X.-T.; et al. Oral Microbiota Alteration and Roles in Epstein-Barr Virus Reactivation in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e03448–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’May, G.A.; Reynolds, N.; Macfarlane, G.T. Effect of pH on an In Vitro Model of Gastric Microbiota in Enteral Nutrition Patients. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 4777–4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira-Marques, J.; Ferreira, R.M.; Pinto-Ribeiro, I.; Figueiredo, C. Helicobacter Pylori Infection, the Gastric Microbiome and Gastric Cancer. In Helicobacter pylori in Human Diseases: Advances in Microbiology, Infectious Diseases and Public Health Volume 11; Kamiya, S., Backert, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; ISBN 978-3-030-21916-1. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.R.; Macfarlane, G.T.; Reynolds, N.; O’May, G.A.; Bahrami, B.; Macfarlane, S. Effect of a Synbiotic on Microbial Community Structure in a Continuous Culture Model of the Gastric Microbiota in Enteral Nutrition Patients. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2012, 80, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akritidou, T.; Smet, C.; Akkermans, S.; Tonti, M.; Williams, J.; Van de Wiele, T.; Van Impe, J.F.M. A Protocol for the Cultivation and Monitoring of Ileal Gut Microbiota Surrogates. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 133, 1919–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firrman, J.; Friedman, E.S.; Hecht, A.; Strange, W.C.; Narrowe, A.B.; Mahalak, K.; Wu, G.D.; Liu, L. Preservation of Conjugated Primary Bile Acids by Oxygenation of the Small Intestinal Microbiota in Vitro. mBio 2024, 15, e00943–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolaki, M.; Minekus, M.; Venema, K.; Lahti, L.; Smid, E.J.; Kleerebezem, M.; Zoetendal, E.G. Microbial Communities in a Dynamic in Vitro Model for the Human Ileum Resemble the Human Ileal Microbiota. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2019, 95, fiz096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Trijp, M.P.H.; Rösch, C.; An, R.; Keshtkar, S.; Logtenberg, M.J.; Hermes, G.D.A.; Zoetendal, E.G.; Schols, H.A.; Hooiveld, G.J.E.J. Fermentation Kinetics of Selected Dietary Fibers by Human Small Intestinal Microbiota Depend on the Type of Fiber and Subject. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, 2000455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyaert, S.; Moens, F.; Pirovano, W.; van den Bogert, B.; Klaassens, E.S.; Marzorati, M.; Van de Wiele, T.; Kleerebezem, M.; Van den Abbeele, P. Development of a Reproducible Small Intestinal Microbiota Model and Its Integration into the SHIME®-System, a Dynamic in Vitro Gut Model. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takada, T.; Chinda, D.; Mikami, T.; Shimizu, K.; Oana, K.; Hayamizu, S.; Miyazawa, K.; Arai, T.; Katto, M.; Nagara, Y.; et al. Dynamic Analysis of Human Small Intestinal Microbiota after an Ingestion of Fermented Milk by Small-Intestinal Fluid Perfusion Using an Endoscopic Retrograde Bowel Insertion Technique. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 1662–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakobsen, R.R.; Trinh, J.T.; Bomholtz, L.; Brok-Lauridsen, S.K.; Sulakvelidze, A.; Nielsen, D.S. A Bacteriophage Cocktail Significantly Reduces Listeria Monocytogenes without Deleterious Impact on the Commensal Gut Microbiota under Simulated Gastrointestinal Conditions. Viruses 2022, 14, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narang, P. Development of In-vitro Model Systems to Study the Effect of the Human Microbiota in Respiratory Diseases. Ph.D., University of Technology Sydney, 2023.

- Munier, A.-L.; de Lastours, V.; Barbier, F.; Chau, F.; Fantin, B.; Ruimy, R. Comparative Dynamics of the Emergence of Fluoroquinolone Resistance in Staphylococci from the Nasal Microbiota of Patients Treated with Fluoroquinolones According to Their Environment. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2015, 46, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherrard, L.J.; McGrath, S.J.; McIlreavey, L.; Hatch, J.; Wolfgang, M.C.; Muhlebach, M.S.; Gilpin, D.F.; Elborn, J.S.; Tunney, M.M. Production of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases and the Potential Indirect Pathogenic Role of Prevotella Isolates from the Cystic Fibrosis Respiratory Microbiota. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2016, 47, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enaud, R.; Prevel, R.; Ciarlo, E.; Beaufils, F.; Wieërs, G.; Guery, B.; Delhaes, L. The Gut-Lung Axis in Health and Respiratory Diseases: A Place for Inter-Organ and Inter-Kingdom Crosstalks. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandeplassche, E.; Sass, A.; Lemarcq, A.; Dandekar, A.A.; Coenye, T.; Crabbé, A. In Vitro Evolution of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa AA2 Biofilms in the Presence of Cystic Fibrosis Lung Microbiome Members. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, D.D.; Fisher, J.R.; Hoskinson, S.M.; Medina-Colorado, A.A.; Shen, Y.C.; Chaaban, M.R.; Widen, S.G.; Eaves-Pyles, T.D.; Maxwell, C.A.; Miller, A.L.; et al. Development of a Novel Ex Vivo Nasal Epithelial Cell Model Supporting Colonization With Human Nasal Microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlat, I.P.; Stroe, R.; Diţu, L.-M.; Curuţiu, C.; Chiurtu, E.R.; Stănculescu, I.; Chifiriuc, M.C.; Lazăr, V. Evaluating the Role of the Working Environment on to Skin and Upper Respiratory Tract Microbiota of Museum Workers. Romanian Biotechnol. Lett. 2020, 25, 2103–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosikowska, U.; Andrzejczuk, S.; Grywalska, E.; Chwiejczak, E.; Winiarczyk, S.; Pietras-Ożga, D.; Stępień-Pyśniak, D. Prevalence of Susceptibility Patterns of Opportunistic Bacteria in Line with CLSI or EUCAST among Haemophilus Parainfluenzae Isolated from Respiratory Microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.; Jesudasen, S.; Bringhurst, L.; Sui, H.-Y.; McIver, L.; Whiteson, K.; Hanselmann, K.; O’Toole, G.A.; Richards, C.J.; Sicilian, L.; et al. Supplemental Oxygen Alters the Airway Microbiome in Cystic Fibrosis. mSystems 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemoine, L. Modulation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Toxicity by the Human Skin Microbiome. Ph.D., Freie Universitaet Berlin, 2021.

- Holland, D.B.; Bojar, R.A.; Jeremy, A.H.T.; Ingham, E.; Holland, K.T. Microbial Colonization of an in Vitro Model of a Tissue Engineered Human Skin Equivalent – a Novel Approach. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008, 279, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanabe, K.; Moriguchi, C.; Fujiyama, N.; Shigematsu, Y.; Haraguchi, N.; Hirano, Y.; Dai, H.; Inaba, S.; Tokudome, Y.; Kitagaki, H. A Trial for the Construction of a Cosmetic Pattern Map Considering Their Effects on Skin Microbiota—Principal Component Analysis of the Effects on Short-Chain Fatty Acid Production by Skin Microbiota Staphylococcus Epidermidis. Fermentation 2023, 9, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetz, R.; Claypool, J.; Sfriso, R.; Vollhardt, J.H. Sunscreens Can Preserve Human Skin Microbiome upon Erythemal UV Exposure. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2024, 46, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timm, C.M.; Loomis, K.; Stone, W.; Mehoke, T.; Brensinger, B.; Pellicore, M.; Staniczenko, P.P.A.; Charles, C.; Nayak, S.; Karig, D.K. Isolation and Characterization of Diverse Microbial Representatives from the Human Skin Microbiome. Microbiome 2020, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harel, N.; Ogen-Shtern, N.; Reshef, L.; Biran, D.; Ron, E.Z.; Gophna, U. Skin Microbiome Bacteria Enriched Following Long Sun Exposure Can Reduce Oxidative Damage. Res. Microbiol. 2023, 174, 104138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoudi, N.; Cassagne, C.; Million, M.; Ranque, S.; Kabore, O.; Drancourt, M.; Zingue, D.; Bouam, A. Investigation of Skin Microbiota Reveals Mycobacterium Ulcerans-Aspergillus Sp. Trans-Kingdom Communication. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stingley, R.L.; Zou, W.; Heinze, T.M.; Chen, H.; Cerniglia, C.E. Metabolism of Azo Dyes by Human Skin Microbiota. J. Med. Microbiol. 2010, 59, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R. “Does the Human Skin Microbiome Adapt to Antibiotic Exposure?” M.Res., University of Salford, 2019.

- Al-Talib, H.; Mohd Kasim, N. A.; Al-khateeb, A.; Murugaiah, C.; Abdul Aziz, A.; Rashid, N. N.; Azizan, N.; Ridzuan, S. Antimicrobial Effect of Malaysian Green Tea Leaves (Camellia Sinensis) on the Skin Microbiota. Malays. J. Microbiol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y. A Systems Approach to Characterize Drivers of Vaginal Microbiome Composition and Bacterial Vaginosis Treatment Efficacy. Ph.D., University of Michigan, 2023.

- Zahra, A.; Menon, R.; Bento, G.F.C.; Selim, J.; Taylor, B.D.; Vincent, K.L.; Pyles, R.B.; Richardson, L.S. Validation of Vaginal Microbiome Proxies for in Vitro Experiments That Biomimic Lactobacillus-Dominant Vaginal Cultures. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2023, 90, e13797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, G.; Doherty, E.; To, T.; Sutherland, A.; Grant, J.; Junaid, A.; Gulati, A.; LoGrande, N.; Izadifar, Z.; Timilsina, S.S.; et al. Vaginal Microbiome-Host Interactions Modeled in a Human Vagina-on-a-Chip. Microbiome 2022, 10, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyles, R.B.; Vincent, K.L.; Baum, M.M.; Elsom, B.; Miller, A.L.; Maxwell, C.; Eaves-Pyles, T.D.; Li, G.; Popov, V.L.; Nusbaum, R.J.; et al. Cultivated Vaginal Microbiomes Alter HIV-1 Infection and Antiretroviral Efficacy in Colonized Epithelial Multilayer Cultures. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e93419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, S.M.; Mafunda, N.A.; Woolston, B.M.; Hayward, M.R.; Frempong, J.F.; Abai, A.B.; Xu, J.; Mitchell, A.J.; Westergaard, X.; Hussain, F.A.; et al. Cysteine Dependence of Lactobacillus Iners Is a Potential Therapeutic Target for Vaginal Microbiota Modulation. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 434–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, A.C.; Hill, J.E. Quantification, Isolation and Characterization of Bifidobacterium from the Vaginal Microbiomes of Reproductive Aged Women. Anaerobe 2017, 47, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerson-Brown, M.H.; Miller, A.L.; Maxwell, C.A.; White, M.M.; Vincent, K.L.; Bourne, N.; Pyles, R.B. Cultivated Human Vaginal Microbiome Communities Impact Zika and Herpes Simplex Virus Replication in Ex Vivo Vaginal Mucosal Cultures. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argentini, C.; Fontana, F.; Alessandri, G.; Lugli, G.A.; Mancabelli, L.; Ossiprandi, M.C.; van Sinderen, D.; Ventura, M.; Milani, C.; Turroni, F. Evaluation of Modulatory Activities of Lactobacillus Crispatus Strains in the Context of the Vaginal Microbiota. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e02733–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouarabi, L.; Chait, Y.A.; Seddik, H.A.; Drider, D.; Bendali, F. Newly Isolated Lactobacilli Strains from Algerian Human Vaginal Microbiota: Lactobacillus Fermentum Strains Relevant Probiotic’s Candidates. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2019, 11, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.-F.; Huang, P.-J.; Cheng, W.-H.; Huang, C.-Y.; Chu, L.J.; Lee, C.-C.; Lin, H.-C.; Chen, L.-C.; Lin, W.-N.; Tsao, C.-H.; et al. Vaginal Microbiota of the Sexually Transmitted Infections Caused by Chlamydia Trachomatis and Trichomonas Vaginalis in Women with Vaginitis in Taiwan. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, M.A.; Seo, H.; Kim, S.; Tajdozian, H.; Barman, I.; Lee, Y.; Lee, S.; Song, H.-Y. In Vitro Anti-Tuberculosis Effect of Probiotic Lacticaseibacillus Rhamnosus PMC203 Isolated from Vaginal Microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrønding, T.; Vomstein, K.; Bosma, E.F.; Mortensen, B.; Westh, H.; Heintz, J.E.; Mollerup, S.; Petersen, A.M.; Ensign, L.M.; DeLong, K.; et al. Antibiotic-Free Vaginal Microbiota Transplant with Donor Engraftment, Dysbiosis Resolution and Live Birth after Recurrent Pregnancy Loss: A Proof of Concept Case Study. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 61, 102070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrocks, V. NMR Metabolomics to Understand Behaviour and Symbiosis between Isolates of the Vaginal Microbiota. Ph.D., King’s College London, 2022.

- Di Vito, M.; Mattarelli, P.; Modesto, M.; Girolamo, A.; Ballardini, M.; Tamburro, A.; Meledandri, M.; Mondello, F. In Vitro Activity of Tea Tree Oil Vaginal Suppositories against Candida Spp. and Probiotic Vaginal Microbiota. Phytother. Res. 2015, 29, 1628–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, E.; Bechelaghem, N. To ‘Douche’ or Not to ‘Douche’: Hygiene Habits May Have Detrimental Effects on Vaginal Microbiota. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 38, 678–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, D.P.; Zhang, J.; Nguyen, N.-T.; Ta, H.T. Microfluidic Gut-on-a-Chip: Fundamentals and Challenges. Biosensors 2023, 13, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhang, K.; Ming, F.; Yangdai, T.; Xu, T.; Shi, H.; Bao, Y.; Yao, H.; Peng, H.; et al. Novel Scheme for Non-Invasive Gut Bioinformation Acquisition with a Magnetically Controlled Sampling Capsule Endoscope. Gut 2021, 70, 2297–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nejati, S.; Wang, J.; Sedaghat, S.; Balog, N.K.; Long, A.M.; Rivera, U.H.; Kasi, V.; Park, K.; Johnson, J.S.; Verma, M.S.; et al. Smart Capsule for Targeted Proximal Colon Microbiome Sampling. Acta Biomater. 2022, 154, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).