Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

I. Introduction

II. Literature Review

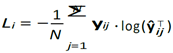

III. Methodology

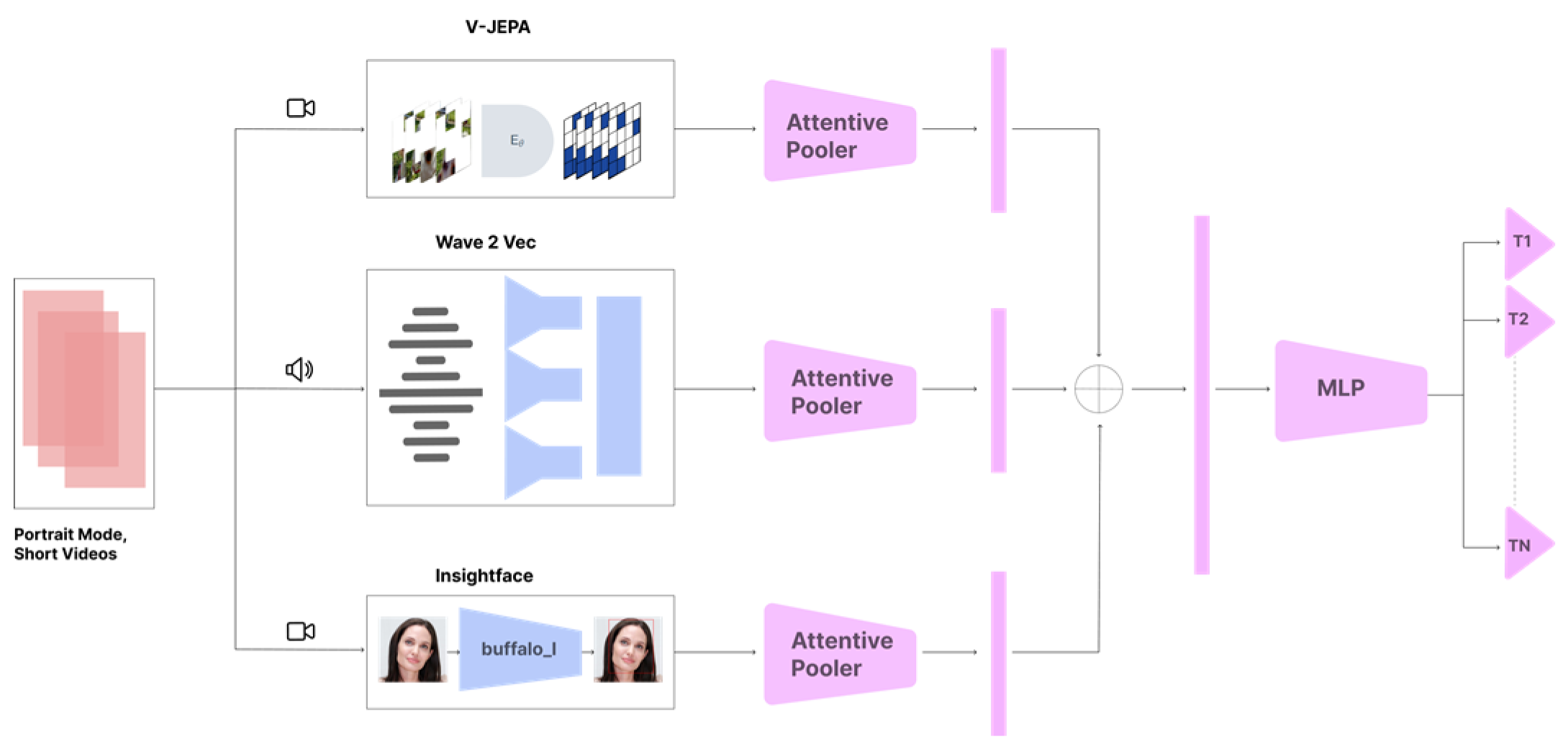

A. Dataset

B. Pretrained Models Used

- Feature Encoder (genc): This component takes the raw waveform x and encodes it into a latent representation c = genc(x).

- Context Network (gar): This is an autoregressive network that models the temporal dependencies in the latent representation c, producing contextualized representations

- zt= gar(c1:t).

- Quantization Module (q): This component quantizes the continuous representations zt into a discrete latent space qt= q(zt).

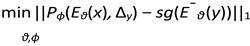

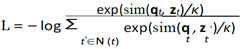

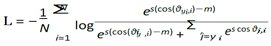

. The model is trained by minimizing the

. The model is trained by minimizing the  loss between predicted and ground truth landmarks:

loss between predicted and ground truth landmarks:

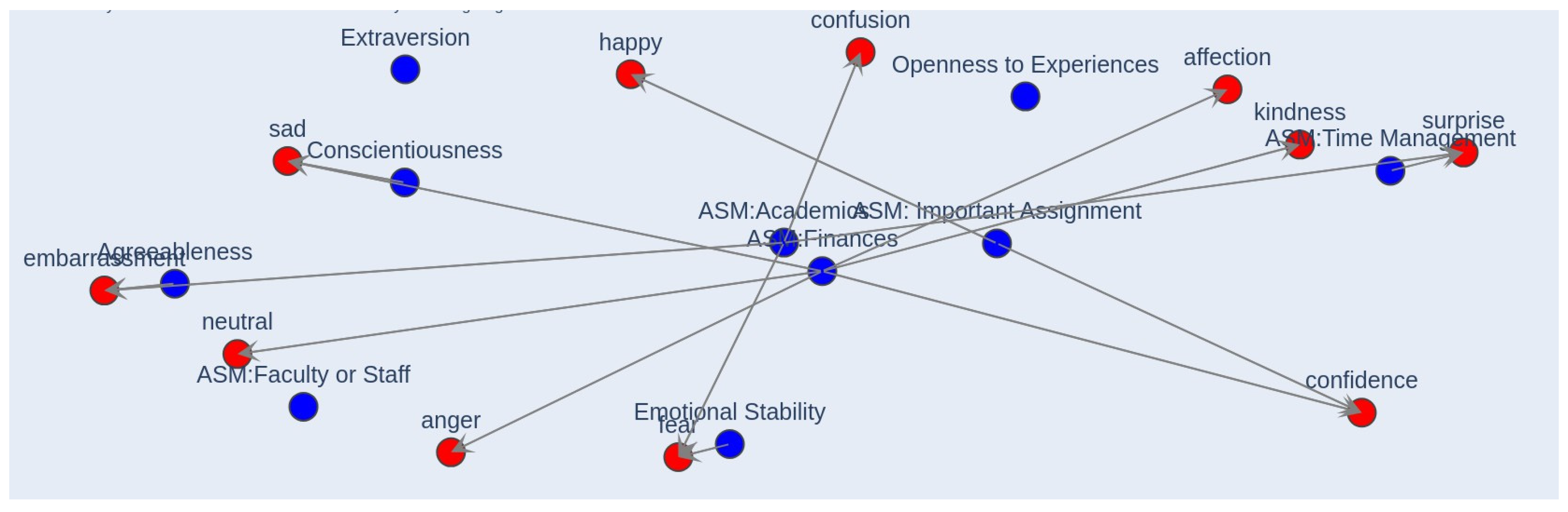

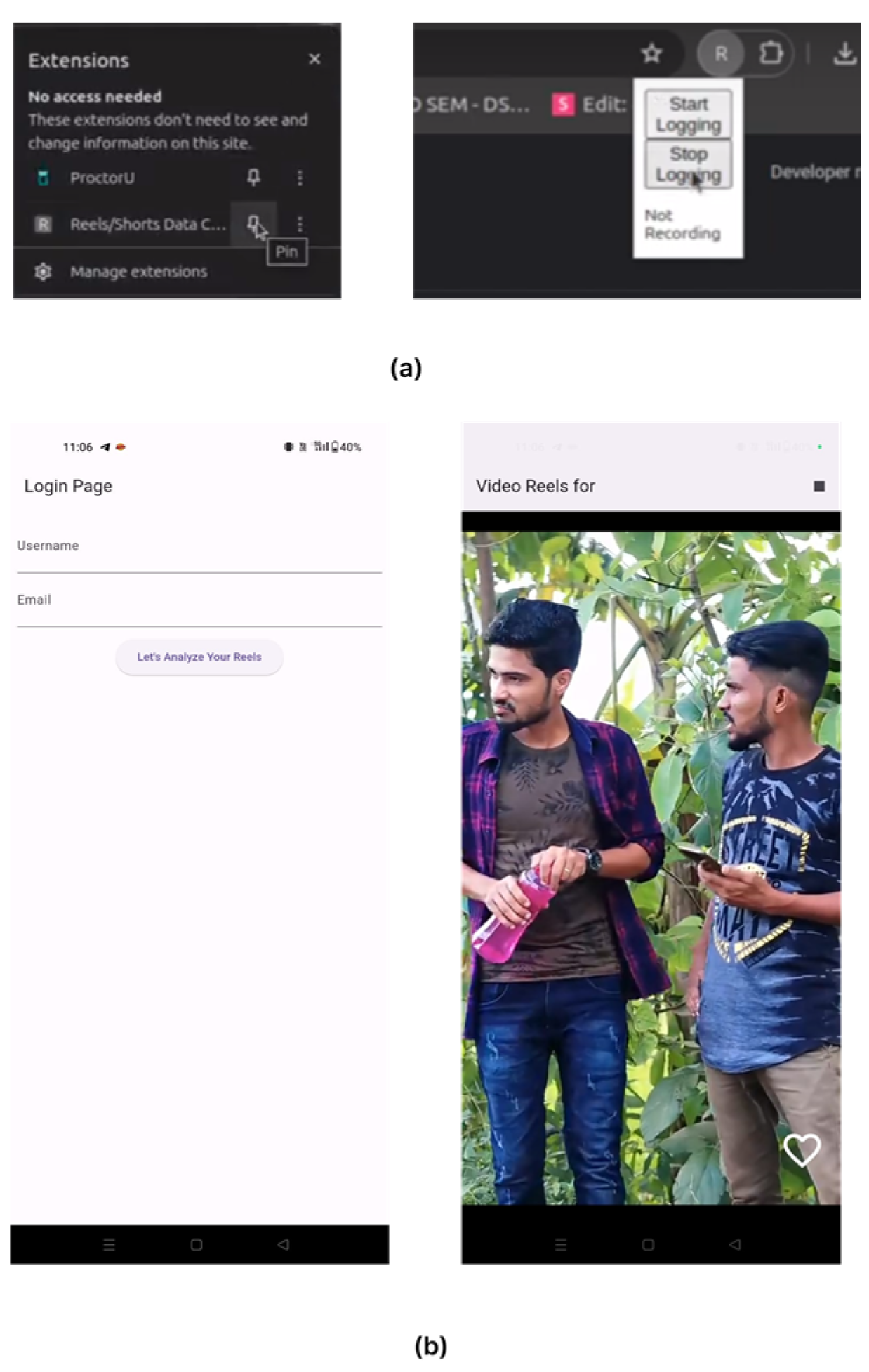

IV. Case Study: Academic Stress Prediction Using Short-Form Video Content

V. Results

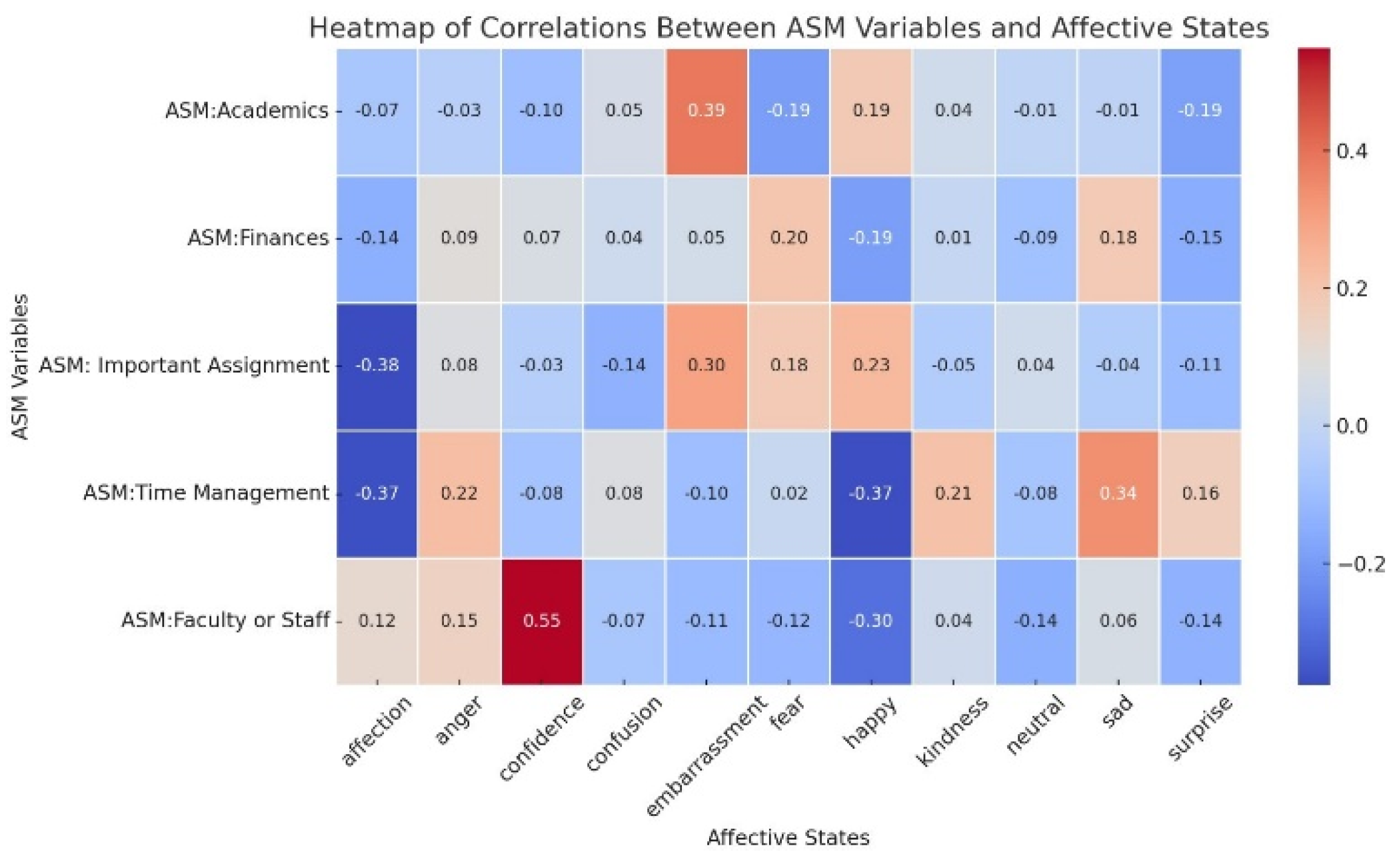

- Financial stress and conscientiousness appear to cause consumption of sad content.

- Academic stress and agreeableness seem to cause consumption of content with embarrassment as an affective state.

- Academic stress, with positive emotional stability, ap- pears to cause consumption of content with fear as an affective state.

VI. Discussion

References

- H. Chhapia, “37 lakh migrated for education within India in a decade - Times of India.” [Online]. Available: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/education/news/37-lakh-migrated- for-education-within-india-in-a-decade/articleshow/29729578.cms.

- E. M. Cotella, A. S. Go´mez, P. Lemen, C. Chen, G. Ferna´ndez, Hansen, J. P. Herman, and M. G. Paglini, “Long-term impact of chronic variable stress in adolescence versus adulthood,” Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, vol. 88, pp. 303–310, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Schraml, A. Perski, G. Grossi, and I. Makower, “Chronic Stress and Its Consequences on Subsequent Academic Achievement among Adolescents,” Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology, vol. 2, no. 1, p. p69, Apr. 2012. [CrossRef]

- N. Mathew, D. C. Khakha, A. Qureshi, R. Sagar, and C. C. Khakha, “Stress and Coping among Adolescents in Selected Schools in the Capital City of India,” The Indian Journal of Pediatrics, vol. 82, no. 9, pp. 809–816, Sep. 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. Parikh, M. Sapru, M. Krishna, P. Cuijpers, V. Patel, and D. Michelson, ““It is like a mind attack”: stress and coping among urban school-going adolescents in India,” BMC Psychology, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 31, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. F. Roberts and U. G. Foehr, “Trends in Media Use,” The Future of Children, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 11–37, 2008, publisher: Princeton University.

- X. Zhang, Y. Wu, and S. Liu, “Exploring short-form video application addiction: Socio-technical and attachment perspectives,” Telematics and Informatics, vol. 42, p. 101243, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. W. Downs, G. Driskill, and D. Wuthnow, “A Review of Instrumen- tation on Stress,” Management Communication Quarterly, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 100–126, Aug. 1990, publisher: SAGE Publications Inc. [CrossRef]

- S. Reisman, “Measurement of physiological stress,” in Proceedings of the IEEE 23rd Northeast Bioengineering Conference, May 1997, pp. 21–23. [CrossRef]

- P. Derevenco, G. Popescu, and N. Deliu, “Stress assessment by means of questionnaires,” Romanian journal of physiology, vol. 37, no. 1-4, pp. 39–49, Jan. 2000.

- I. Kokka, G. P. Chrousos, C. Darviri, and F. Bacopoulou, “Measuring Adolescent Chronic Stress: A Review of Established Biomarkers and Psychometric Instruments,” Hormone Research in Paediatrics, vol. 96, no. 1, pp. 74–82, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. C. Towbes and L. H. Cohen, “Chronic stress in the lives of college students: Scale development and prospective prediction of distress,” Journal of Youth and Adolescence, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 199–217, Apr. 1996. [CrossRef]

- N. Sharma and T. Gedeon, “Objective measures, sensors and compu- tational techniques for stress recognition and classification: A survey,” Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, vol. 108, no. 3, pp. 1287–1301, Dec. 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Aguilo´, P. Ferrer-Salvans, A. Garc´ıa-Rozo, A. Armario, Corb´ı, F. J. Cambra, R. Bailo´n, A. Gonza´lez-Marcos, G. Caja, S. Aguilo´, R. Lo´pez- Anto´n, A. Arza-Valde´s, and J. M. Garzo´n-Rey, “Project ES3: attempting to quantify and measure the level of stress.

- J. Carreira, E. Noland, C. Hillier, and A. Zisserman, “A short note on the kinetics-700 human action dataset,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.06987, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Miech, D. Zhukov, J.-B. Alayrac, M. Tapaswi, I. Laptev, and J. Sivic, “Howto100m: Learning a text-video embedding by watching hundred million narrated video clips,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2019, pp. 2630–2640.

- J.-B. Grill, F. Strub, F. Altche´, C. Tallec, P. Richemond, E. Buchatskaya, Doersch, B. Avila Pires, Z. Guo, M. Gheshlaghi Azar et al., “Bootstrap your own latent-a new approach to self-supervised learning,” Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 33, pp. 21 271– 21 284, 2020.

- A. Baevski, Y. Zhou, A. Mohamed, and M. Auli, “wav2vec 2.0: A framework for self-supervised learning of speech representations,” Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 33, pp. 12 449– 12 460, 2020.

- A. Gangwar, S. Umesh, R. Sarab, A. K. Dubey, G. Divakaran, S. V. Gangashetty et al., “Spring-inx: A multilingual indian language speech corpus by spring lab, iit madras,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.14654, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Flynn, B. A. Sundermeier, and N. R. Rivera, “A new, brief measure of college students’ academic stressors,” Journal of American College Health, pp. 1–8, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. D. Gosling, P. J. Rentfrow, and W. B. Swann Jr, “A very brief measure of the big-five personality domains,” Journal of Research in personality, vol. 37, no. 6, pp. 504–528, 2003. [CrossRef]

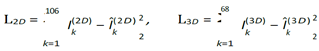

| Modality | Backbone | Top-1 | Top-3 | Top-5 |

| Visual | R(2+1)D-50 | 50.6 | 72.3 | 81.4 |

| Visual | R3D-50 | 52.7 | 74.5 | 83.6 |

| Visual | R3D-101 | 52.6 | 74.1 | 83.3 |

| Audio | VGG | 31.6 | 50.5 | 60.9 |

| Audio | CLSRIL23 | 31.2 | 50.1 | 60.6 |

| Visual, Audio | R3D-50 + VGG | 54.9 | 74.9 | 82.4 |

| Visual, Audio | R3D-50 + CLSRIL23 | 54.9 | 75.4 | 82.9 |

| Visual, Audio | R3D-50 + VGG + CLSRIL23 | 56.5 | 76.5 | 83.8 |

| Visual, AudioFace (Ours) |

V-JEPA+Wav2vec(Indic) + Buffalo_l |

58.93 | 78.34 | 87.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).