Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

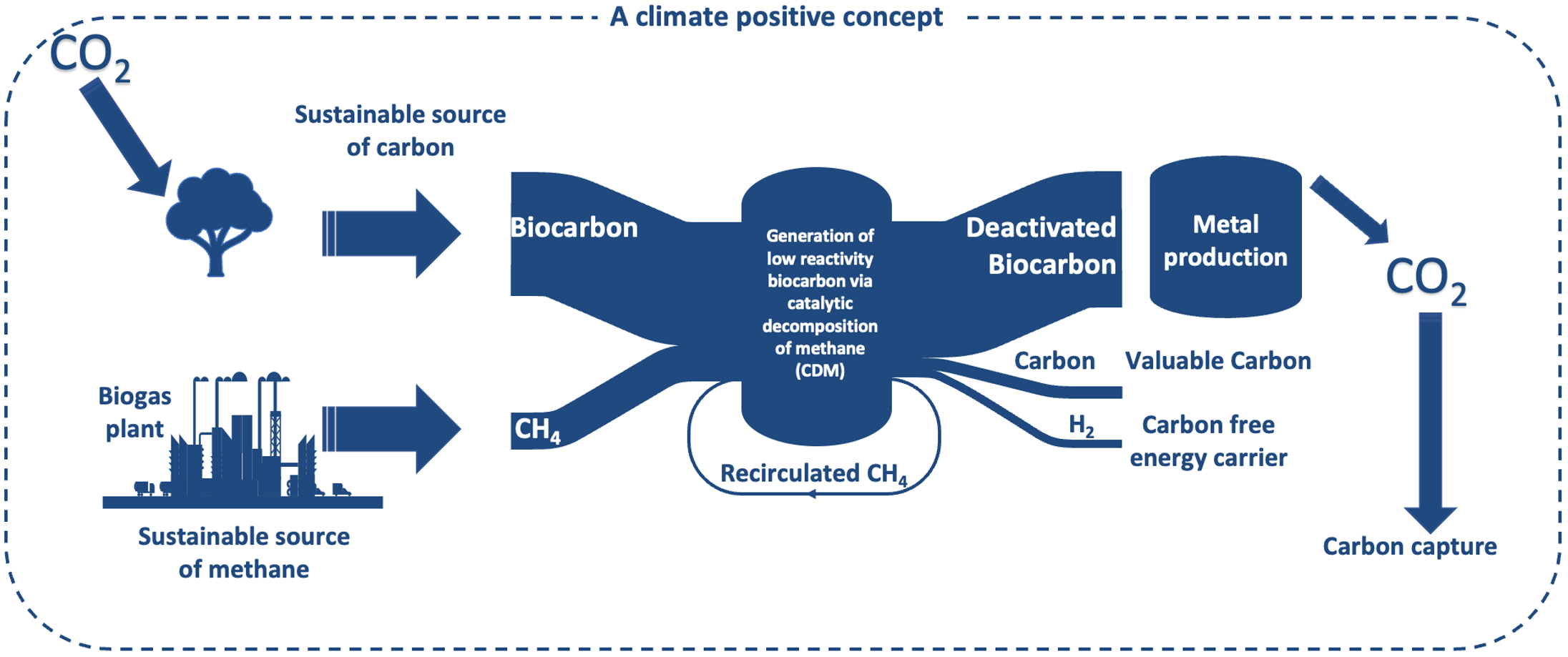

Abstract

To reach agreed-on climate goals, it is necessary to develop new energy carriers and industrial materials that are carbon neutral. To combat global warming and keep Earth’s temperature below a 1.5 °C increase, some of these solutions need to be carbon negative. This study fulfills this criterion by producing clean hydrogen, and biocarbon, suitable for the metallurgic industry, through the thermal decomposition of methane using biocarbon as a catalyst. Five different biomass samples were used to prepare biocarbons, at a pyrolysis temperature of 1000 °C and a holding time of 90 minutes. When methane was cracked at 1100 °C and a holding time of 90 minutes, the highest hydrogen production was 105 mol/kg biocarbon, using birch bark. The lowest hydrogen yield, of 68 mol/kg biocarbon, was achieved with steam explosion pellets. All biocarbons showed substantial carbon deposition from cracked methane on the surface, with the highest deposition on birch bark and spruce wood biocarbon, of 42 % relative to the biocarbon start weight. The carbon deposition increased with decomposition temperature, methane-share in the purge gas and holding time. The steam explosion pellets, after deactivation, had a CO2 reactivity that is comparable to coke, a reducing agent that is commonly used in manganese producing industry.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biocarbon production

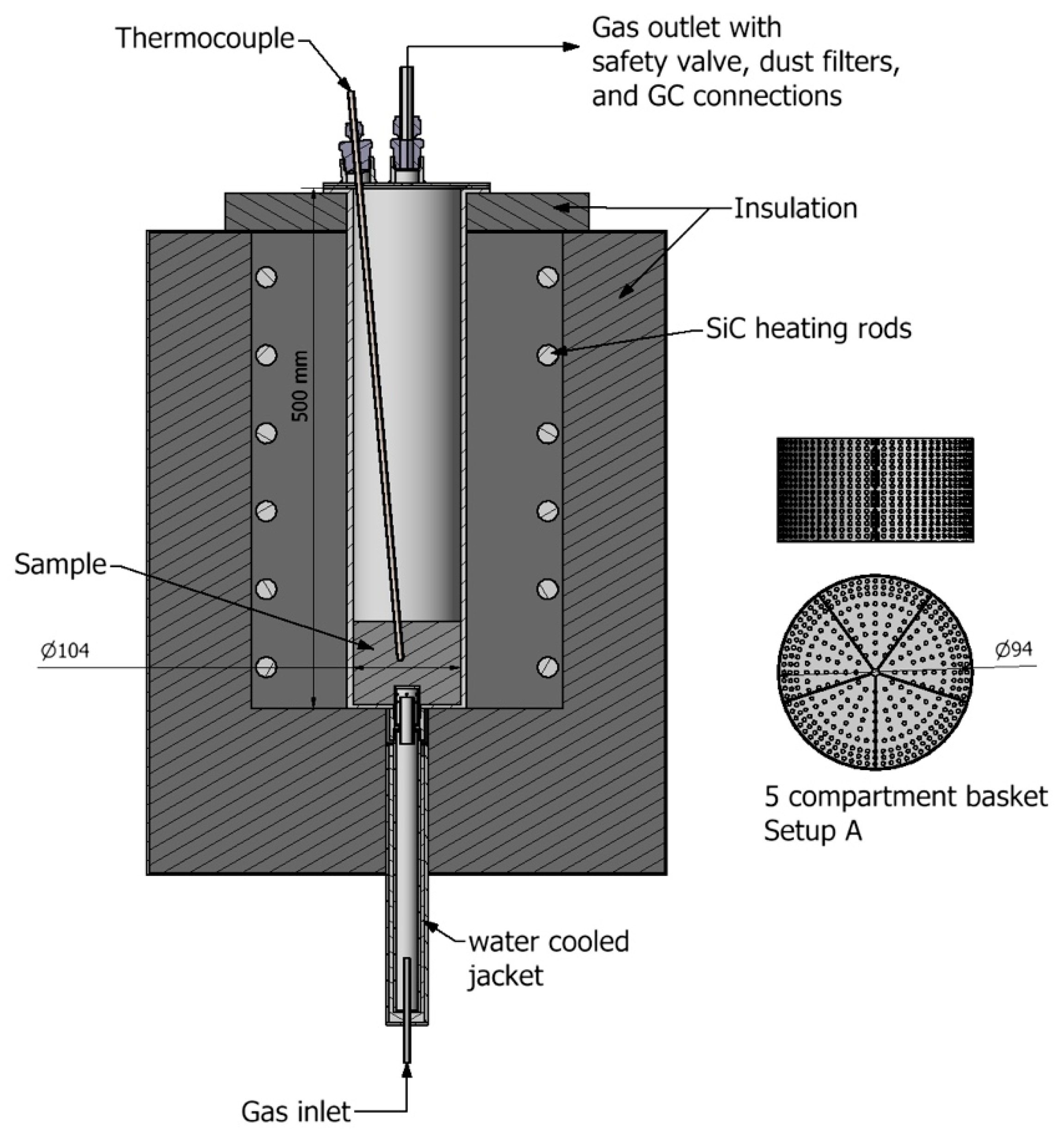

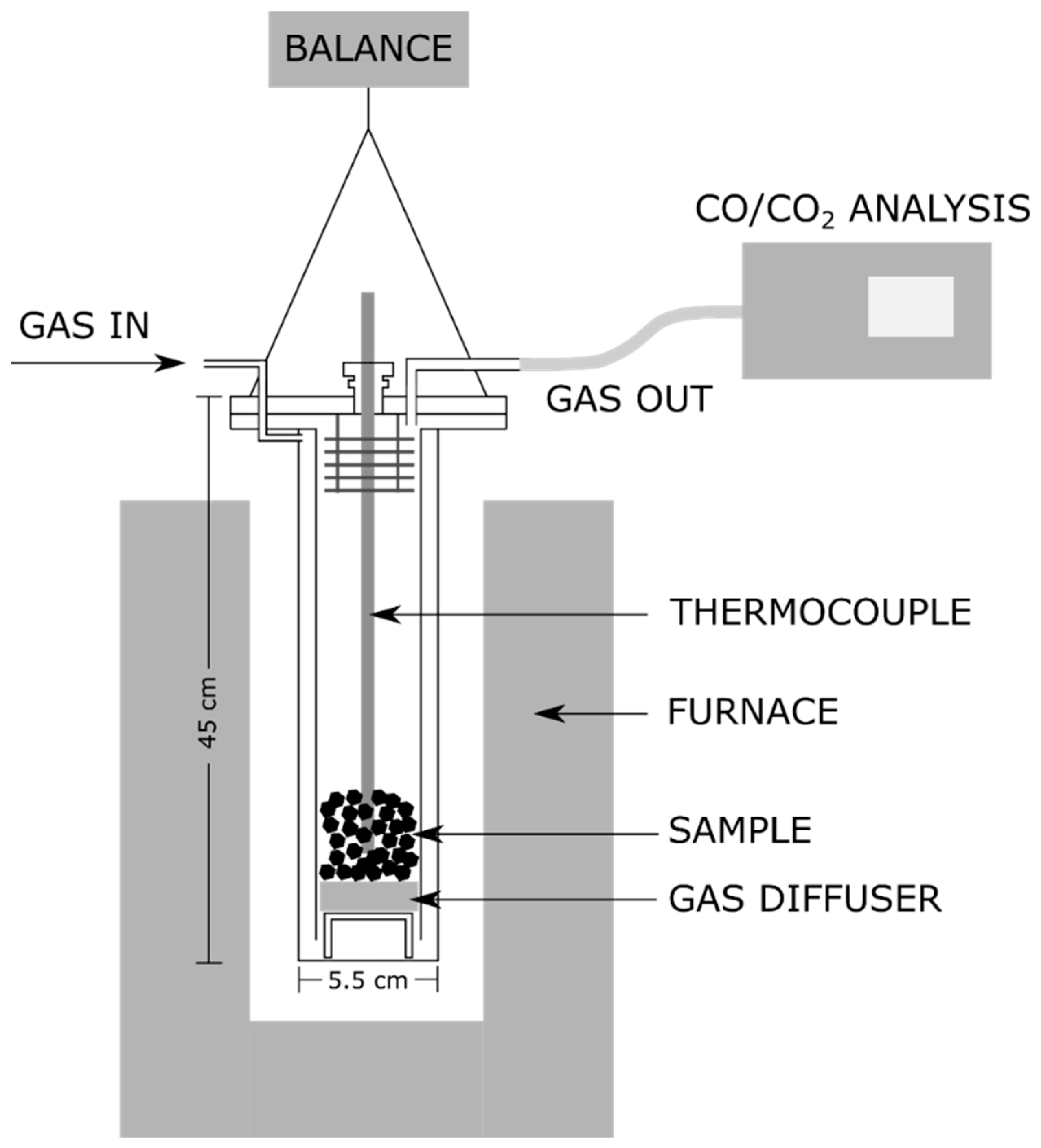

2.2. Methane cracking setups

2.3. Biocarbon characterization

2.3.1. Proximate analysis

2.3.2. Element analysis

2.3.3. Ash forming element analysis

2.3.4. Surface area, porosity and density analysis

2.3.5. Raman analysis

2.3.6. SEM-EDS analysis

2.3.7. Mechanical properties analysis

2.3.8. CO2-Reactivity

3. Results and discussion

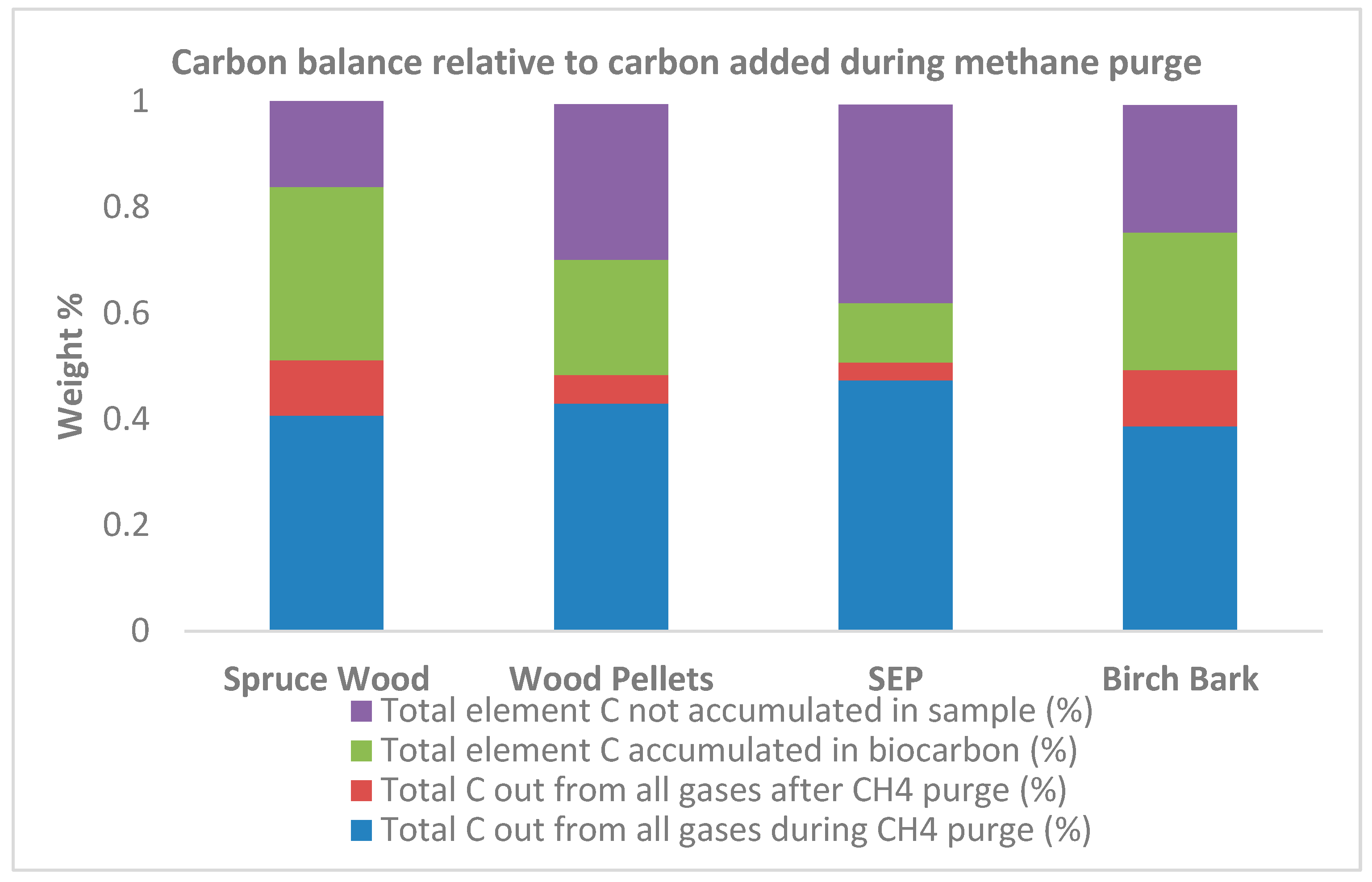

3.1. Hydrogen potential from catalytic methane cracking

3.2. Characterization of the treated biocarbon

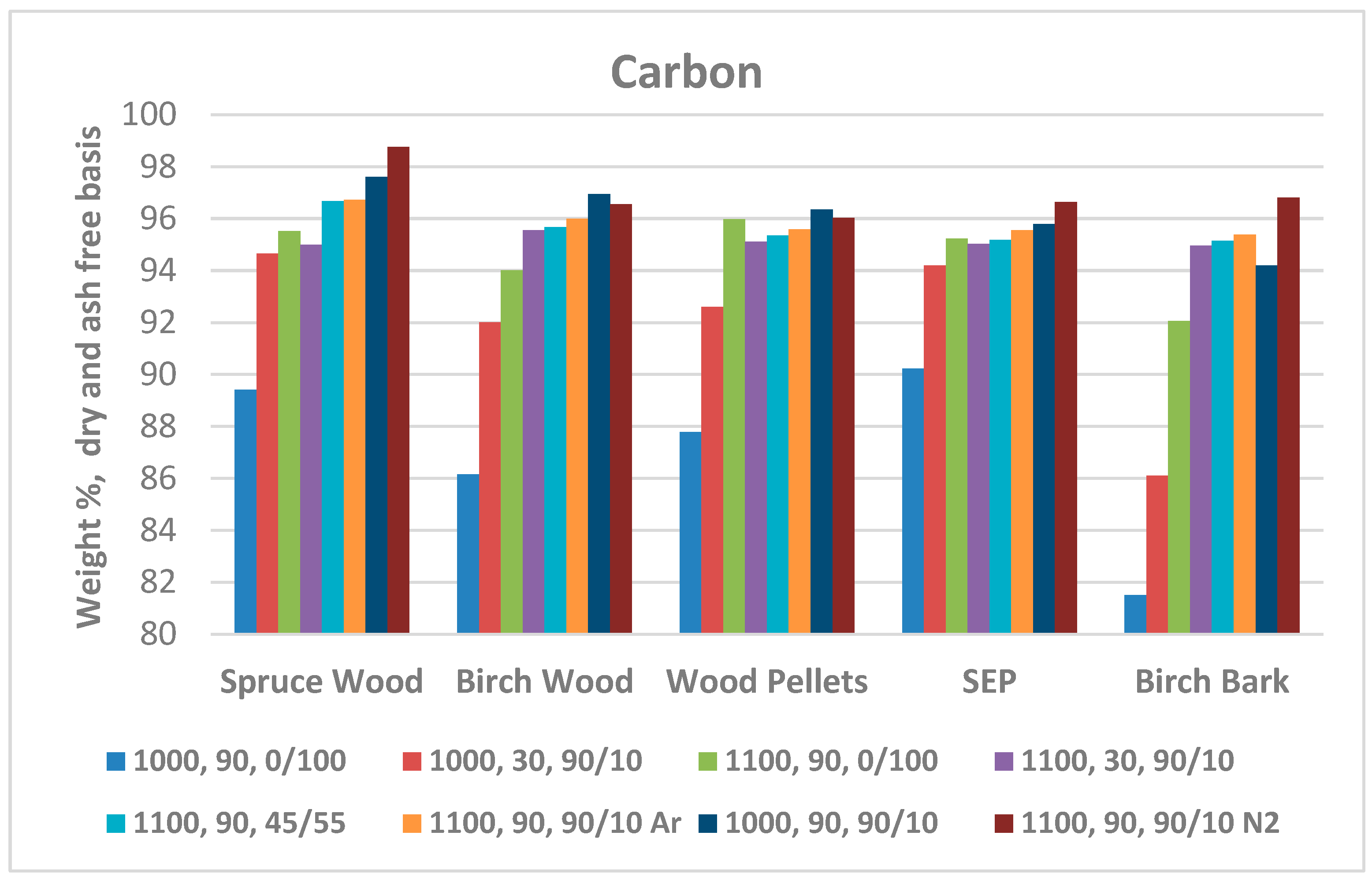

3.2.1. Proximate and element analysis

3.2.2. Ash forming element analysis

3.2.3. Surface, and density analysis

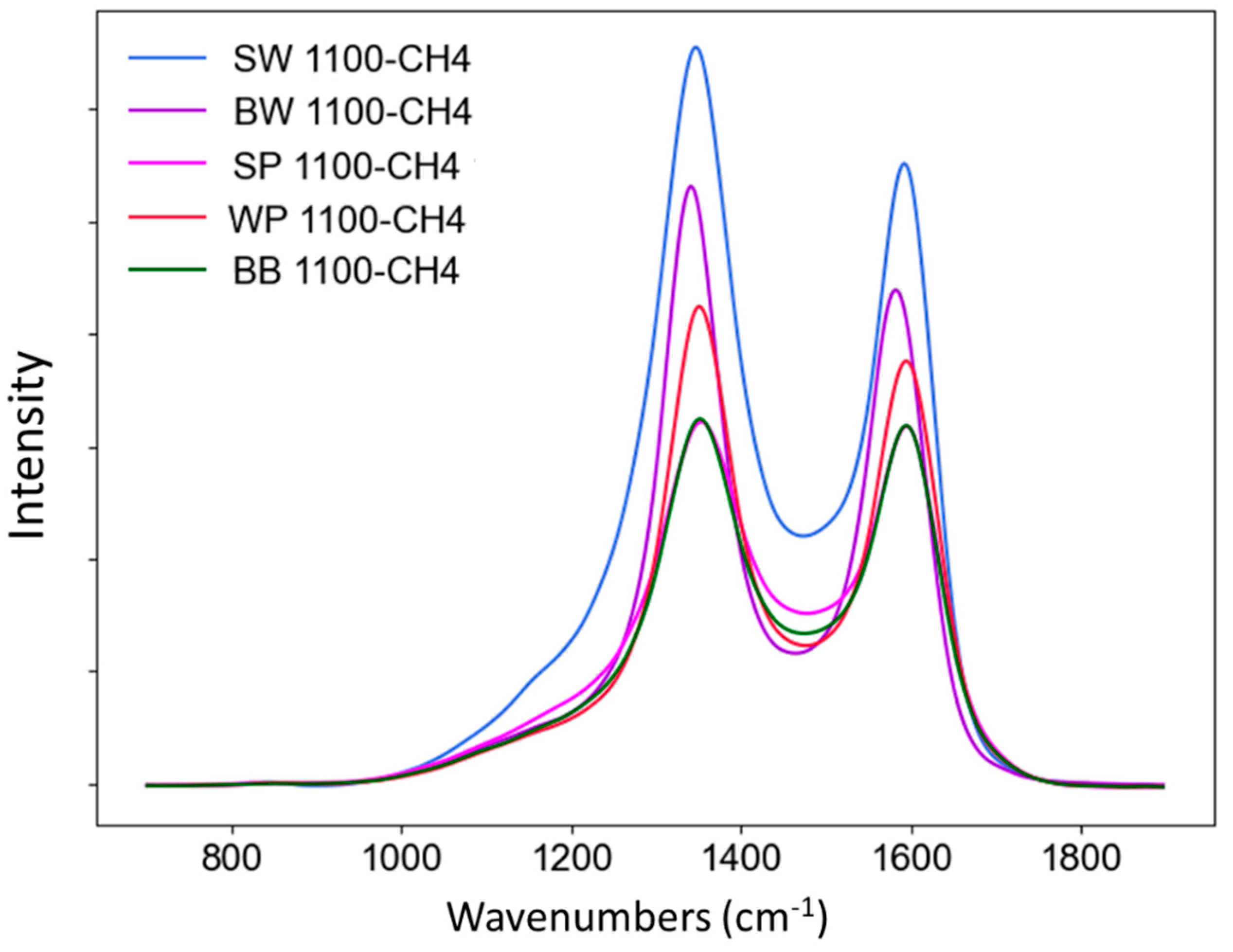

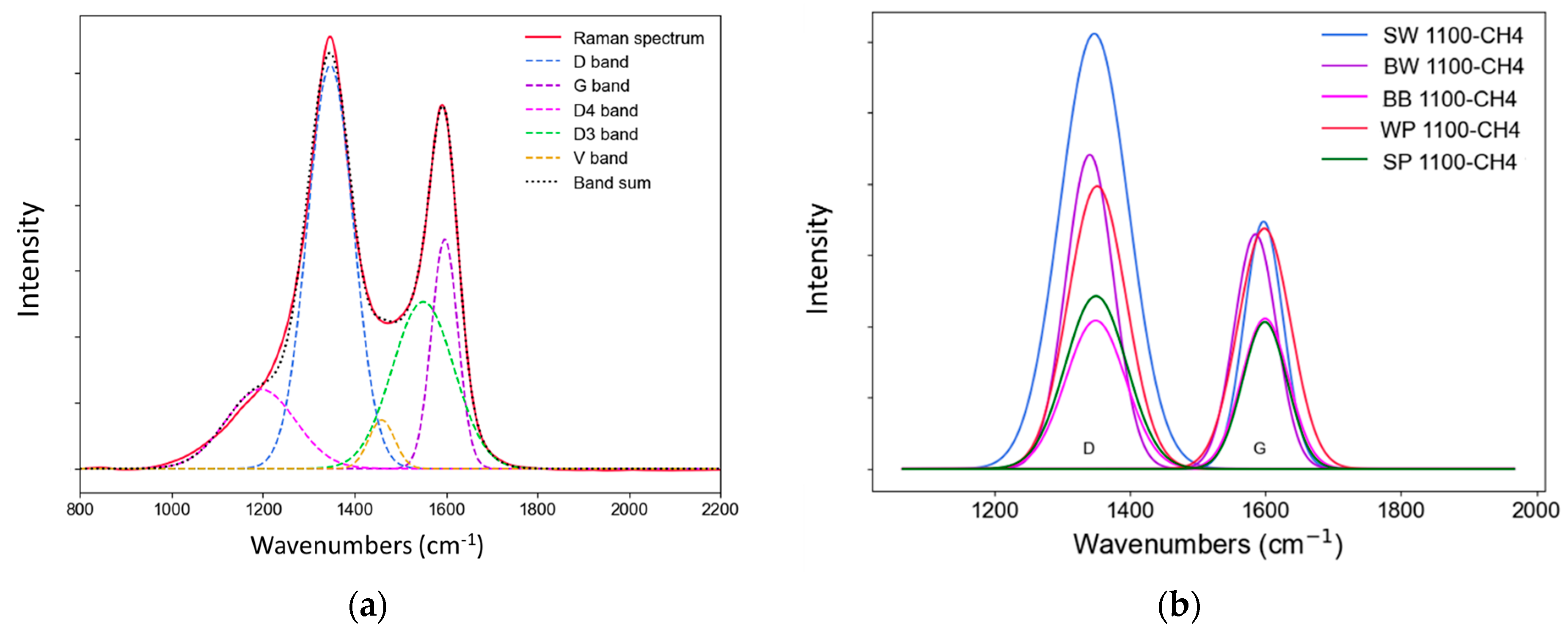

3.2.4. Raman analysis

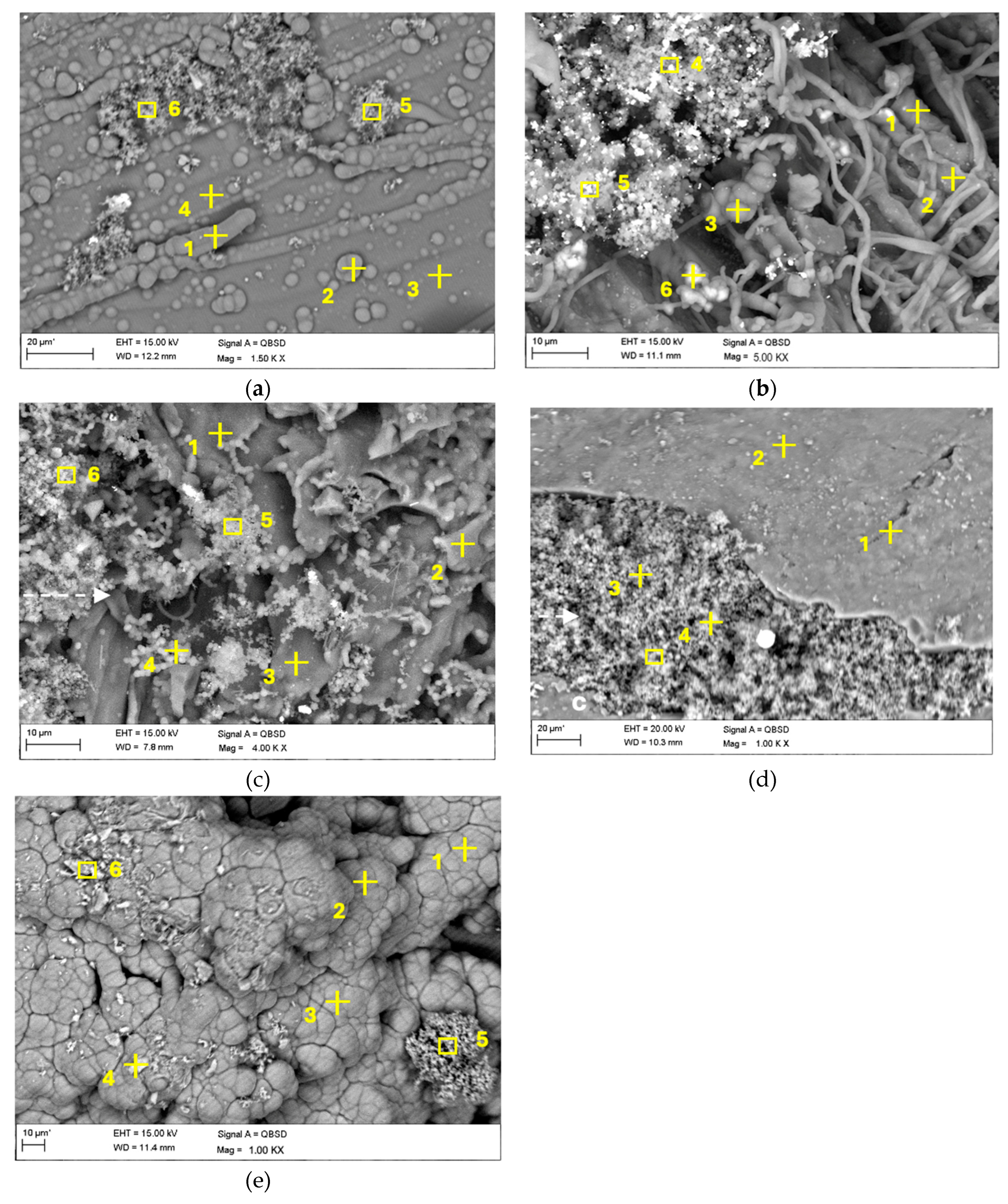

3.2.5. SEM-EDS analysis

3.2.6. Mechanical properties analysis

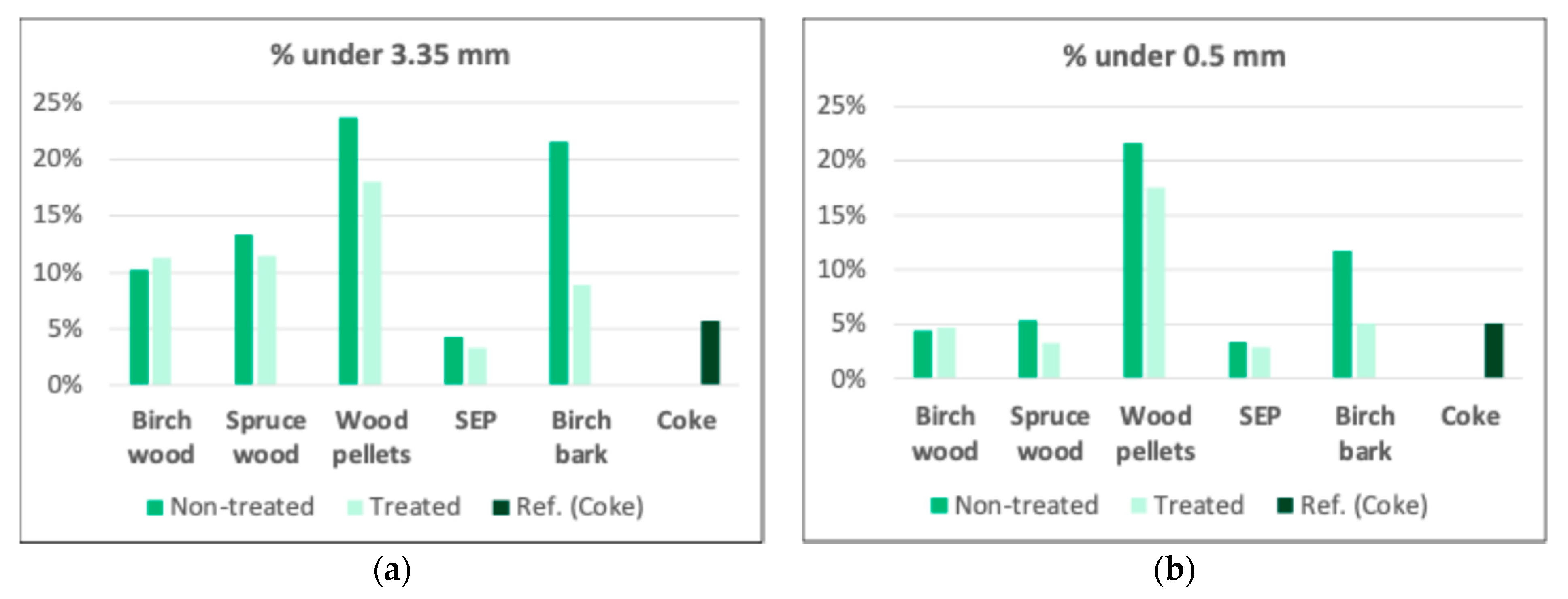

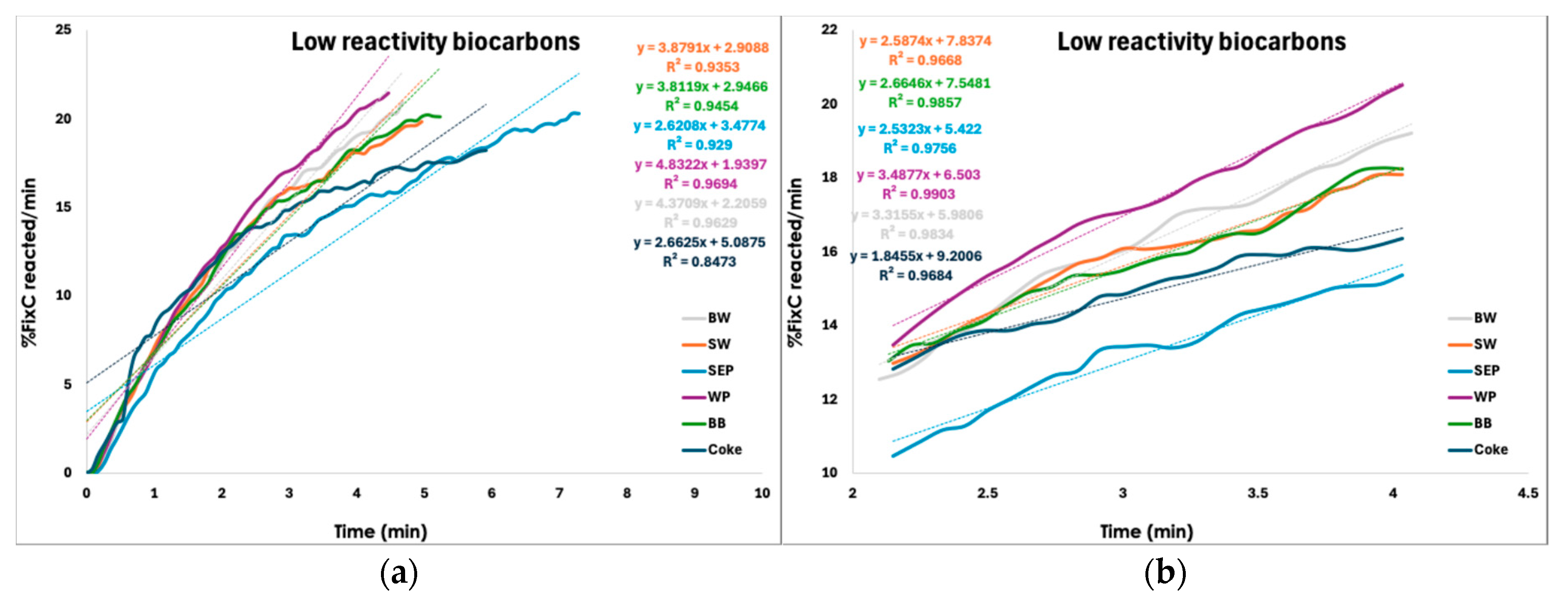

3.2.7. CO2-Reactivity

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heintz, I.; Mousa, E.; Ye, G. Development of Fossil-Free Technologies for the Metallurgical Industry—Swerim Pilot and Industrial Experiences. In Proceedings of the Advances in Pyrometallurgy; Fleuriault, C., Steenkamp, J.D., Gregurek, D., White, J.F., Reynolds, Q.G., Mackey, P.J., Hockaday, S.A.C., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2023; pp. 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Souza Filho, I.R.; Springer, H.; Ma, Y.; Mahajan, A.; da Silva, C.C.; Kulse, M.; Raabe, D. Green Steel at Its Crossroads: Hybrid Hydrogen-Based Reduction of Iron Ores. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 340, 130805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Quader, M.; Ahmed, S.; Dawal, S.Z.; Nukman, Y. Present Needs, Recent Progress and Future Trends of Energy-Efficient Ultra-Low Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Steelmaking (ULCOS) Program. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 55, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalaker, H.; Hovig, E.W. Hydrogen Plasma-Based Reduction of Metal Oxides. In Proceedings of the Advances in Pyrometallurgy; Fleuriault, C., Steenkamp, J.D., Gregurek, D., White, J.F., Reynolds, Q.G., Mackey, P.J., Hockaday, S.A.C., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2023; pp. 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Schanche, T.L.; Tangstad, M. Prereduction of Nchwaning Ore in CO/CO2/H2 Gas Mixtures. Minerals 2021, 11, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osen, K.S.; Dalaker, H.; Martinez, A.M.; Gudbrandsen, H.; Wang, Z.; Kero, I. CO2 Free FeMn/Mn Production Through Molten Oxide Electrolysis. In Proceedings of the Advances in Pyrometallurgy; Fleuriault, C., Steenkamp, J.D., Gregurek, D., White, J.F., Reynolds, Q.G., Mackey, P.J., Hockaday, S.A.C., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2023; pp. 267–280. [Google Scholar]

- Allanore, A. Features and Challenges of Molten Oxide Electrolytes for Metal Extraction. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2014, 162, E13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiencke, J.; Lavelaine, H.; Kane, G.J.; Panteix, P.-J.; Petitjean, C.; Rapin, C. Kinetics of Iron Electrochemical Reduction into Liquid Metal at 1823 K in a Molten Oxide Electrolyte. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2018, 212, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrhaug, E.H. Non-Fossil Reduction Materials in the Silicon Process - Properties and Behaviour. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kaffash, H.; Surup, G.R.; Tangstad, M. Densification of Biocarbon and Its Effect on CO2 Reactivity. Processes 2021, 9, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, H.F.; Wan Daud, W.M.A. Hydrogen Production by Methane Decomposition: A Review. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 1160–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Qi, M.; Zhang, G.; Hu, H.; Ma, X. Hydrogen Production by Catalytic Methane Decomposition: Carbon Materials as Catalysts or Catalyst Supports. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 19755–19775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suelves, I.; Lazaro, M.; Moliner, R.; Corbella, B.; Palacios, J. Hydrogen Production by Thermo Catalytic Decomposition of Methane on Ni-Based Catalysts: Influence of Operating Conditions on Catalyst Deactivation and Carbon Characteristics. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2005, 30, 1555–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Epling, W.; Croiset, E. Reaction and Deactivation Rates of Methane Catalytic Cracking over Nickel. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 12460–12470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.; Panjala, D.; Huffman, G.P. Hydrogen Production by Catalytic Decomposition of Methane. Energy Fuels 2001, 15, 1528–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Wang, Y.; Shi, X.; Shah, N.; Huggins, F.; Bollineni, S.; Seehra, M.; Huffman, G. Catalytic Nonoxidative Dehydrogenation of Ethane over Fe–Ni and Ni Catalysts Supported on Mg(Al)O to Produce Hydrogen and Easily Purified Carbon Nanotubes. Energy Fuels 2007, 21, 3520–3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Y.; Lua, A.C. Development of Metallic Nickel Nanoparticle Catalyst for the Decomposition of Methane into Hydrogen and Carbon Nanofibers. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 26765–26775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moliner, R.; Suelves, I.; Lazaro, M.; Moreno, O. Thermocatalytic Decomposition of Methane over Activated Carbons: Influence of Textural Properties and Surface Chemistry. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2005, 30, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. Hydrogen Production by Catalytic Decomposition of Methane over Activated Carbons: Kinetic Study. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2004, 29, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.K.; Han, G.Y.; Yoon, K.J.; Lee, B.K. Thermocatalytic Hydrogen Production from the Methane in a Fluidized Bed with Activated Carbon Catalyst. Catalysis Today 2004, 93–95, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Chen, H.; Li, B.; Li, W. Catalytic Decomposition of Methane over Activated Carbon. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2005, 73, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, H.F.; Daud, W.M.A.W. Thermocatalytic Decomposition of Methane for Hydrogen Production Using Activated Carbon Catalyst: Regeneration and Characterization Studies. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 8034–8045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Xiao, R.; Li, Y.; Shen, L. Catalytic Carbon Dioxide Reforming of Methane to Synthesis Gas over Activated Carbon Catalyst. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008, 47, 4349–4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.K.; Lee, S.Y.; Han, G.Y.; Lee, B.K.; Lee, T.-J.; Jun, J.H.; Yoon, K.J. Catalytic Decomposition of Methane over Carbon Blacks for CO2-Free Hydrogen Production. Carbon 2004, 42, 2641–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradov, N.; Smith, F.; T-Raissi, A. Catalytic Activity of Carbons for Methane Decomposition Reaction. Catalysis Today 2005, 102–103, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suelves, I.; Pinilla, J.L.; Lázaro, M.J.; Moliner, R. Carbonaceous Materials as Catalysts for Decomposition of Methane. Chemical Engineering Journal 2008, 140, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Tan, Y.; Han, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, D. Hydrogen Production by Methane Cracking over Different Coal Chars. Fuel 2011, 90, 3473–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Zhu, M.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, D. Hydrogen Production by Methane Cracking over Xiaolongtan Lignite Chars: The Role of Mineral Matter. Fuel 2016, 183, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.; Larachi, F.; Ziegler, D.; Alamdari, H. Effects of Heat Treatment and Acid Washing on Properties and Reactivity of Charcoal. Biomass and Bioenergy 2016, 90, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Khalil, R.; Bakken, J.; Skreiberg, Ø. Production and Characterization of Biocarbon from Woody Biomasses Produced at 1000 °C 2024.

- Maziarka, P.; Wurzer, C.; Arauzo, P.J.; Dieguez-Alonso, A.; Mašek, O.; Ronsse, F. Do You BET on Routine? The Reliability of N2 Physisorption for the Quantitative Assessment of Biochar’s Surface Area. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 418, 129234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Olsen, M.N.P.; Moni, C.; Dieguez-Alonso, A.; de la Rosa, J.M.; Stenrød, M.; Liu, X.; Mao, L. Comparison of Properties of Biochar Produced from Different Types of Lignocellulosic Biomass by Slow Pyrolysis at 600 °C. Applications in Energy and Combustion Science 2022, 12, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitzky, A.; Golay, M. J. Smoothing and Differentiation of Data by Simplified Least Squares Procedures. Anal. Chem. 1964, 36, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, A.; Pandya, A.K.; Serhatkulu, G.K.; Weber, R.E.; Dai, H.; Thakur, J.S.; Naik, V.M.; Naik, R.; Auner, G.W.; Rabah, R.; et al. A Robust Method for Automated Background Subtraction of Tissue Fluorescence. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 2007, 38, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phounglamcheik, A.; Wang, L.; Romar, H.; Kienzl, N.; Broström, M.; Ramser, K.; Skreiberg, Ø.; Umeki, K. Effects of Pyrolysis Conditions and Feedstocks on the Properties and Gasification Reactivity of Charcoal from Woodchips. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 8353–8365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimaru, K.; Hata, T.; Bronsveld, P.; Nishizawa, T.; Imamura, Y. Characterization of Sp2- and Sp3-Bonded Carbon in Wood Charcoal. J Wood Sci 2007, 53, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, C. Char Structure Characterised by Raman Spectroscopy and Its Correlations with Combustion Reactivity. Fuel 2007, 86, 2316–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Dong, M.; Nie, W.; Rao, G.; Lu, J. Conversion Mechanism of Organic Components during the Eucalyptus Biomass Pyrolysis Process Based on the Multispectral Association Method. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 7929–7940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, A.C.A.; Anniwaer, A.; Okura, H.; Chaerusani, V.; Zhang, P.; Rizkiana, J.; Kurnia, I.; Abudula, A.; Guan, G. Addition of Torrefied Algal Biomass to Improve Land-Based Biomass Gasification for Hydrogen-Rich Gas Production. Algal Research 2023, 74, 103236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.A.; Kercher, A.K.; Nguyen, T.H.; Nagle, D.C.; Ball, W.P. Production and Characterization of Synthetic Wood Chars for Use as Surrogates for Natural Sorbents. Organic Geochemistry 2006, 37, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizani, C.; Escudero Sanz, F.J.; Salvador, S. The Nature of the Deposited Carbon at Methane Cracking over a Nickel Loaded Wood-Char. Comptes Rendus Chimie 2016, 19, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameya, Y.; Hanamura, K. Kinetic and Raman Spectroscopic Study on Catalytic Characteristics of Carbon Blacks in Methane Decomposition. Chemical Engineering Journal 2011, 173, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradov, N. Catalysis of Methane Decomposition over Elemental Carbon. Catalysis Communications 2001, 2, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, S.; Kurimoto, Y. Raman Spectroscopic Study on Pyrolyzed Wood and Bark of Japanese Cedar: Temperature Dependence of Raman Parameters. J Wood Sci 2003, 49, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Exp. # | Material | Reactor T. (°C) | Holding time (min) | Environment | Gas analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | All | 1000 | 30 | 90/10 CH4/Ar | no |

| 2 | All | 1000 | 90 | 90/10 CH4/Ar | no |

| 3 | All | 1100 | 30 | 90/10 CH4/Ar | no |

| 4 | All | 1100 | 90 | 45/55 CH4/Ar | no |

| 5 | All | 1100 | 90 | 90/10 CH4/Ar | no |

| 6 | All | 1100 | 90 | 0/100 CH4/Ar | no |

| 7 | Spruce Wood | 1100 | 75 | 90/10 CH4/N2 | yes |

| 8 | Birch Wood | 1100 | 90 | 90/10 CH4/N2 | yes |

| 9 | Wood Pellets | 1100 | 90 | 90/10 CH4/N2 | yes |

| 10 | SEP | 1100 | 90 | 90/10 CH4/N2 | yes |

| 11 | Birch Bark | 1100 | 90 | 90/10 CH4/N2 | yes |

| Feedstock | Spruce Wood | Wood Pellets | SEP | Birch Bark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start weight of biocarbon (g) | 81.7 | 80.0 | 100.0 | 82.5 |

| Volatiles released prior to CH4 purge (g) and in % relative to start weight | 0.02 (0.02%) |

0.74 (0.93%) |

0.82 (0.82%) |

0.99 (1.2%) |

| Weight prior to CH4 purge (g) | 81.7 | 79.2 | 99.2 | 81.5 |

| Weight gained (g) and in % relative to start weight | 34.36 (42.1%) |

26.48 (33.4%) |

13.8 (13.9%) |

34.91 (42.8%) |

| Total H2 out (mol) | 7.3 | 7.4 | 6.8 | 8.7 |

| Total CH4 out (mol) | 3.3 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 4.0 |

| Total C2H4 out (mol) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Total H2 out (mol/mol CH4 in) | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| Total H2 out (mol/kg biocarbon) | 89.9 | 92.4 | 68.2 | 105.2 |

| Total CH4 out (mol/kg biocarbon) | 40.1 | 50.6 | 44.8 | 48.4 |

| Spruce Wood | Birch Wood | Wood Pellets | SEP | Birch Bark | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biocarbon from pyrolysis | ||||||

| Volatile matter content | 5.23 | 5.84 | 5.45 | 5.35 | 6.57 | |

| Ash content | 0.82 | 1.29 | 0.80 | 1.08 | 3.98 | |

| Fixed carbon content | 93.95 | 92.87 | 93.75 | 93.57 | 89.45 | |

| Treated biocarbon, at 1100 °C, 90 min, and 90/10 (CH4/N2) | ||||||

| Volatile matter content | 4.74 | 4.72 | 4.40 | 3.49 | 5.09 | |

| Ash content | 0.79 | 1.09 | 0.77 | 1.03 | 2.08 | |

| Fixed carbon content | 94.47 | 94.19 | 94.83 | 95.48 | 92.83 | |

| Spruce Wood | Birch Wood | Wood Pellets | SEP | Birch Bark | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biocarbon from pyrolysis | ||||||

| Carbon | 89.42 | 89.67 | 88.99 | 90.23 | 88.10 | |

| Hydrogen | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.82 | |

| Nitrogen | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.44 | 0.57 | 0.52 | |

| Sulphur | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.02 | |

| Oxygen | 9.27 | 9.04 | 9.77 | 8.47 | 10.54 | |

| Treated biocarbon, at 1100 °C, 90 min, and 90/10 (CH4/N2) | ||||||

| Carbon | 98.77 | 96.56 | 96.03 | 96.65 | 96.81 | |

| Hydrogen | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.12 | |

| Nitrogen | 0.10 | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.38 | |

| Sulphur | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.02 | |

| Oxygen | 1.04 | 2.85 | 3.40 | 2.84 | 2.67 | |

| Treated biocarbon, at 1000 °C, 30 min, and 90/10 (CH4/Ar) | ||||||

| Carbon | 94.66 | 92.00 | 92.60 | 94.19 | 91.11 | |

| Hydrogen | 0.31 | 0.52 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.64 | |

| Nitrogen | 0.50 | 0.68 | 0.72 | 0.77 | 0.91 | |

| Sulphur | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.02 | |

| Oxygen | 4.52 | 6.75 | 6.23 | 4.51 | 7.33 | |

| Treated biocarbon, at 1000 °C, 90 min, and 90/10 (CH4/Ar) | ||||||

| Carbon | 97.61 | 96.95 | 96.36 | 95.80 | 94.20 | |

| Hydrogen | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.24 | |

| Nitrogen | 0.69 | 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.79 | 0.88 | |

| Sulphur | 0.02 | 0.014 | 0.012 | 0.016 | 0.019 | |

| Oxygen | 1.45 | 2.35 | 2.91 | 3.25 | 4.68 | |

| Treated biocarbon, at 1100 C, 30 min, and 90/10 (CH4/Ar) | ||||||

| Carbon | 95.00 | 95.56 | 95.11 | 95.03 | 94.96 | |

| Hydrogen | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.31 | 0.26 | |

| Nitrogen | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 0.31 | |

| Sulphur | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| Oxygen | 4.54 | 3.96 | 4.45 | 4.31 | 4.45 | |

| Treated biocarbon, at 1100 °C, 90 min, and 45/55 (CH4/Ar) | ||||||

| Carbon | 96.67 | 95.68 | 95.36 | 95.19 | 95.16 | |

| Hydrogen | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.19 | |

| Nitrogen | 0.20 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.55 | |

| Sulphur | 0.014 | 0.013 | 0.016 | 0.02 | 0.019 | |

| Oxygen | 2.91 | 3.84 | 4.19 | 4.40 | 4.11 | |

| Treated biocarbon, at 1100 °C, 90 min, and 90/10 (CH4/Ar) | ||||||

| Carbon | 96.73 | 95.99 | 95.59 | 95.56 | 95.38 | |

| Hydrogen | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.23 | |

| Nitrogen | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.24 | |

| Sulphur | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | |

| Oxygen | 2.71 | 3.53 | 4.00 | 4.06 | 4.13 | |

| Treated biocarbon, at 1100 °C, 90 min, and 0/100 (CH4/Ar) | ||||||

| Carbon | 95.53 | 94.01 | 95.97 | 95.23 | 93.89 | |

| Hydrogen | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.14 | |

| Nitrogen | 0.55 | 0.68 | 0.63 | 0.47 | 0.44 | |

| Sulphur | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| Oxygen | 3.77 | 5.07 | 3.26 | 4.15 | 5.52 | |

| Spruce Wood | Birch Wood | Wood Pellets | SEP | Birch Bark | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biocarbon from pyrolysis | ||||||

| Calcium | 3620 | 4151 | 2890 | 3280 | 16549 | |

| Potassium | 2770 | 3595 | 1797 | 1396 | 8048 | |

| Phosphorus | 291 | 240 | 272 | 142 | 957 | |

| Silicon | 134 | 169 | 122 | 123 | 340 | |

| Sodium | 1861 | 1885 | 1699 | 1047 | 6831 | |

| Sulphur | 158 | 175 | 98 | 140 | 637 | |

| Magnesium | 381 | 505 | 352 | 262 | 1285 | |

| Manganese | 352 | 304 | 346 | 247 | 859 | |

| Aluminum | 212 | 270 | 142 | 125 | 353 | |

| Iron | 224 | 330 | 216 | 139 | 460 | |

| Copper | 3 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 5 | |

| Zinc | 9 | 11 | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| Barium | 58 | 67 | 48 | 79 | 354 | |

| Titanium | 7 | 21 | 11 | 4 | 21 | |

| Treated biocarbon, at 1100 °C, 90 min, and 90/10 (CH4/N2) | ||||||

| Calcium | 2550 | 3706 | 2350 | 3260 | 14780 | |

| Potassium | 340 | 219 | 199 | 170 | 4578 | |

| Phosphorus | 150 | 143 | 138 | 89 | 357 | |

| Silicon | 119 | 134 | 154 | 110 | 200 | |

| Sodium | 106 | 202 | 135 | 106 | 180 | |

| Sulphur | 98 | 162 | 113 | 70 | 287 | |

| Magnesium | 273 | 372 | 408 | 390 | 1174 | |

| Manganese | 151 | 259 | 260 | 384 | 406 | |

| Aluminum | 64 | 140 | 88 | 85 | 156 | |

| Iron | 198 | 441 | 182 | 102 | 278 | |

| Copper | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 6 | |

| Zinc | 4 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 9 | |

| Barium | 36 | 55 | 30 | 69 | 205 | |

| Titanium | 3 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 13 | |

| Treated biocarbon, at 1000 °C, 30 min, and 90/10 (CH4/Ar) | ||||||

| Calcium | 3150 | 3110 | 2620 | 3030 | 16280 | |

| Potassium | 1060 | 840 | 350 | 850 | 6440 | |

| Phosphorus | 210 | 240 | 206 | 200 | 1320 | |

| Silicon | 108 | 134 | 139 | 109 | 441 | |

| Sodium | 131 | 227 | 147 | 191 | 374 | |

| Sulphur | 80 | 36 | 45 | 120 | 280 | |

| Magnesium | 369 | 412 | 719 | 407 | 1196 | |

| Manganese | 226 | 291 | 326 | 405 | 772 | |

| Aluminum | 74 | 42 | 32 | 76 | 86 | |

| Iron | 149 | 459 | 208 | 108 | 392 | |

| Copper | 6 | 6 | 5 | 136 | 93 | |

| Zinc | 5 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 4 | |

| Barium | 53 | 68 | 33 | 71 | 308 | |

| Titanium | 10 | 10 | 1 | 6 | 9 | |

| Treated biocarbon, at 1100 °C, 90 min, and 90/10 (CH4/Ar) | ||||||

| Calcium | 3211 | 2182 | 2819 | 2618 | 11285 | |

| Potassium | 123 | 164 | 218 | 200 | 143 | |

| Phosphorus | 27 | 421 | 24 | 128 | 1138 | |

| Silicon | 140 | 168 | 173 | 135 | 402 | |

| Sodium | 151 | 182 | 100 | 64 | 160 | |

| Sulphur | 112 | 183 | 128 | 156 | 224 | |

| Magnesium | 340 | 973 | 357 | 383 | 1165 | |

| Manganese | 94 | 291 | 87 | 361 | 446 | |

| Aluminum | 59 | 109 | 97 | 81 | 172 | |

| Iron | 68 | 466 | 173 | 284 | 250 | |

| Copper | 2 | 5 | 2 | 14 | 5 | |

| Zinc | 4 | 9 | 5 | 34 | 6 | |

| Barium | 55 | 36 | 70 | 63 | 197 | |

| Titanium | 5 | 10 | 5 | 21 | 13 | |

| Treated biocarbon, at 1100 °C, 90 min, and 0/100 (CH4/Ar) | ||||||

| Calcium | 3079 | 2780 | 3710 | 3031 | 14770 | |

| Potassium | 1456 | 1630 | 1410 | 1382 | 6800 | |

| Phosphorus | 189 | 170 | 123 | 220 | 620 | |

| Silicon | 156 | 187 | 181 | 143 | 413 | |

| Sodium | 1045 | 1175 | 691 | 506 | 2288 | |

| Sulphur | 118 | 100 | 60 | 80 | 210 | |

| Magnesium | 282 | 431 | 341 | 260 | 1122 | |

| Manganese | 312 | 266 | 297 | 376 | 989 | |

| Aluminum | 95 | 85 | 37 | 65 | 311 | |

| Iron | 49 | 138 | 74 | 178 | 241 | |

| Copper | 7 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 12 | |

| Zinc | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Barium | 92 | 47 | 67 | 84 | 392 | |

| Titanium | 1 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 21 | |

| Physio-chemical property | Spruce Wood | Birch Wood | Wood Pellets | SEP | Birch Bark | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biocarbon from pyrolysis | ||||||

| Surface area (N2) (m2 g-1) | 204 | 223 | 150 | 105 | 279 | |

| Density (g cm-3) | 1.97 | 1.99 | 2.04 | 2.02 | 1.70 | |

| Treated biocarbon | ||||||

| Surface area (N2) (m2 g-1) | 167 (18%) |

148 (34%) | 133 (11%) | 88 (16%) |

203 (27%) |

|

| Density (g cm-3) | 1.79 (9%) |

1.81 (9%) |

1.69 (17%) | 1.97 (3%) |

1.62 (5%) |

|

| Parameter | Spruce Wood | Birch Wood | Wood Pellets | SEP | Birch Bark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID/IG | 1.76 | 1.37 | 1.25 | 1.16 | 0.99 |

| AD/AG | 3.08 | 2.35 | 1.29 | 1.51 | 1.26 |

| AD/Atotal | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.33 |

| FWHMD (cm–1) | 159.3 | 127.5 | 120.2 | 101.2 | 104.3 |

| FWHMG (cm–1) | 95.2 | 102.6 | 104.2 | 98.7 | 96.4 |

| C | O | Ca | Si | K | Na | P | Mg | Al | Fe | Fe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spruce wood (atomic ratio %) | |||||||||||

| 1 | 91.1 | 8.5 | n.d. | n.d. | 0.1 | 0.2 | n.d. | n.d. | 0 | n.d. | 0 |

| 2 | 91.2 | 8.3 | 0.4 | 0.06 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.1 |

| 3 | 92.8 | 6.0 | 0.7 | 0.09 | 0.3 | n.d. | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.d. | 0.1 |

| 4 | 94.5 | 4.5 | 0.5 | 0.23 | 0.1 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.2 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 5 | 89.2 | 9.1 | 1.4 | 0.09 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | 0.1 | 0.1 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 6 | 88.9 | 9.3 | 1.0 | 0.24 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | n.d. | 0 |

| Birch wood (atomic ratio %) | |||||||||||

| 1 | 98.6 | 1.4 | n.d. | 0.02 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 2 | 98.7 | 1.3 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0 | n.d. | 0 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 3 | 98.9 | 1.0 | n.d. | 0.02 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 4 | n.d. | 11.3 | 79 | 0.92 | n.d. | 1.2 | 0.3 | 3.7 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| 5 | n.d. | 10.9 | 80 | 1.27 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 2.4 | n.d. | 4.2 | 1.5 |

| 6 | 33.2 | 6.3 | 45 | 11.8 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.3 | n.d. | 2.5 | 1.1 |

| Wood pellets (atomic ratio %) | |||||||||||

| 1 | 93.2 | 1.5 | 3.7 | n.d. | 1.2 | n.d. | 0.2 | n.d. | 0.1 | n.d. | 0.1 |

| 2 | 95.7 | 4.2 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0 | n.d. | 0 | n.d |

| 3 | 96.4 | 3.5 | n.d. | 0.05 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0 | 0 | n.d. |

| 4 | 75.3 | 19.3 | 1.5 | 0.02 | 2.1 | 1.6 | n.d. | 0.2 | 0.1 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 5 | 76.8 | 15.8 | 2.4 | 0.17 | 2.1 | 1.8 | n.d. | 0.6 | 0.3 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 6 | 79.7 | 14.5 | 1.6 | n.d. | 0.2 | 3.8 | n.d. | n.d. | 0.1 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Steam explosion pellets (atomic ratio %) | |||||||||||

| 1 | 97.6 | 2.4 | n.d. | 0.03 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 2 | 94.7 | 4.5 | 0.5 | 0.01 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | n.d. | 0.1 |

| 3 | 88.8 | 11.0 | n.d. | 0.1 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0 | 0 | n.d. | 0.1 |

| 4 | 90.6 | 9.0 | n.d. | 0.1 | 0.1 | n.d. | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | n.d. | 0.1 |

| Birch bark (atomic ratio %) | |||||||||||

| 1 | 94.6 | 3.5 | 1.6 | 0.07 | 0.2 | 0 | n.d. | 0 | 0.1 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 2 | 90.6 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 0.23 | 0.4 | 0.1 | n.d. | n.d. | 0.1 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 3 | 90.9 | 5.4 | 3.2 | 0.13 | 0.3 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | 0.1 | n.d. | 0 |

| 4 | 88.7 | 9.9 | 0.2 | 0.24 | 0.2 | 0.3 | n.d. | 0.3 | 0.2 | n.d. | 0 |

| 5 | 83.1 | 14.2 | 0.5 | 0.18 | 0.1 | 0.9 | n.d. | 0.6 | 0.4 | n.d. | 0.1 |

| 6 | 88.0 | 9.8 | 0.5 | 0.29 | 0 | 0.5 | n.d. | 0.5 | 0.3 | n.d. | 0.1 |

| Start wt. (g) | End wt. (g) | Wt. loss (%) | Overall RR 1 | 1-2 min RR 2 | 2-4 min. RR 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-treated biocarbons | ||||||

| SW | 20 | 17.9 | 10.6 | 9.46 | 8.48 | - |

| BW | 19 | 17.1 | 14.5 | 9.95 | 9.29 | 7.72 |

| WP | 20 | 17.7 | 11.7 | 6.1 | 6.8 | 4.56 |

| SEP | 20 | 18.1 | 9.5 | 5.05 | 5.17 | 4.02 |

| BB | 20 | 17.2 | 14.2 | 11.37 | 9.22 | - |

| Treated biocarbons | ||||||

| SW | 20 | 18.9 | 5.9 | 3.88 | 5.24 | 2.59 |

| BW | 20 | 18.9 | 5.6 | 4.37 | 4.79 | 3.32 |

| WP | 20 | 17.8 | 11.1 | 4.83 | 5.86 | 3.49 |

| SEP | 20 | 18.9 | 5.5 | 2.62 | 4.45 | 2.53 |

| BB | 20 | 19.3 | 3.7 | 3.81 | 5.16 | 2.66 |

| SW | 20 | 18.9 | 5.9 | 3.88 | 5.24 | 2.59 |

| Reference (Coke) | ||||||

| 20 | 17.8 | 1.1 | 2.66 | 4.07 | 1.85 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).