1. Introduction

Land use and land cover (LULC) refer to the classification of the earth’s surface based on how land is utilized (land use) and the physical material present on the earth’s surface (land cover). The rapid transformation of land use and land cover (LULC) due to anthropogenic activities poses significant challenges for environmental sustainability, urban planning, and resource management. Accurate detection and prediction of these changes are essential for informed decision-making and effective policy formulation. Traditional methods of LULC monitoring, often reliant on manual interpretation of satellite imagery, are increasingly being complemented by advanced computational techniques. Among these, deep learning has emerged as a powerful tool, utilizing vast amounts of remote sensing data to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of LULC classification and change detection [

1]. Monitoring changes in LULC is vital for several reasons. First, land use changes can significantly impact ecosystems and biodiversity, leading to habitat loss and fragmentation. For instance, urban expansion often encroaches on natural habitats, threatening wildlife and altering local ecosystems. Second, changes in land cover can influence climate patterns, as different surfaces reflect, absorb, and emit heat and moisture differently. For example, deforestation can lead to increased carbon emissions and changes in local and regional climates. Third, effective LULC monitoring is crucial for sustainable resource management, as it provides insights into land degradation, soil erosion, and the sustainability of agricultural practices. Policymakers and land managers rely on accurate and timely LULC data to make informed decisions regarding land use planning and environmental protection.

Deep learning algorithms, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in image processing tasks, enabling the extraction of complex features from high-dimensional data [

2]. The integration of remote sensing with deep learning techniques allows for the automated analysis of spatial patterns and temporal dynamics in LULC. This synergy not only improves the precision of land cover classification but also facilitates the prediction of future land use scenarios, crucial for understanding the implications of urbanization, deforestation, and agricultural expansion [

3]. Recent studies have illustrated the effectiveness of deep learning models in various contexts, ranging from urban area mapping to forest cover change detection [

2,

4]. These advancements underscore the potential of utilizing high-resolution satellite imagery and time-series data to monitor LULC changes with unprecedented detail and accuracy. Furthermore, the application of deep learning in conjunction with remote sensing technologies holds promise for addressing critical global challenges such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and food security.

Despite these advancements, several challenges persist in the application of deep learning for LULC change detection. Data scarcity, particularly the lack of high-quality labeled datasets, remains a significant barrier to training effective models, especially in developing regions [

5]. Additionally, deep learning models require substantial computational resources for training and inference, which can limit their accessibility for researchers and practitioners [

2]. The issue of transferability is also critical; models trained in one geographical region may not perform well in another due to variations in land cover types and environmental conditions. Research into domain adaptation techniques is needed to address this issue [

6].

This paper aims to explore the current state of research on the detection and prediction of LULC changes using deep learning methodologies in remote sensing. We will review key studies, highlight innovative approaches, and discuss the challenges and future directions in this rapidly evolving field.

2. Related Work

The application of deep learning techniques to land use and land cover (LULC) change detection has captured significant attention in recent years. Researchers have explored various methodologies, architectures, and data sources to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of LULC classification and prediction. This section provides an overview of the related work in this domain, highlighting key advancements and approaches.

Before the advent of deep learning, traditional machine learning methods, such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Random Forests, and decision trees, were widely used for LULC classification. These methods relied heavily on handcrafted features derived from spectral data. For instance, [

7] demonstrated that SVMs could effectively classify land use types using multispectral satellite imagery. However, these traditional methods often struggled with complex landscapes, where the relationships between features were not easily captured [

8].

The introduction of deep learning, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), has revolutionized the field of remote sensing. CNNs are capable of automatically learning hierarchical features from raw pixel data, which enhances their ability to classify complex land cover types. [

9] utilized a deep CNN architecture for LULC classification using Landsat imagery, achieving significant improvements in classification accuracy compared to traditional methods. Their work highlighted the potential of deep learning to handle large datasets and learn intricate patterns in the data.

Recent studies have focused on utilizing temporal data to improve change detection in LULC. [

10] proposed a recurrent neural network (RNN) model that incorporated multi-temporal satellite imagery for detecting land cover changes over time. Their model effectively captured temporal dependencies, resulting in enhanced accuracy in identifying changes in urban and agricultural areas. Similarly, [

11] integrated CNNs with RNNs to analyze time-series data, demonstrating that the combined approach led to improved change detection performance.

Integrating data from multiple sources, such as LiDAR, hyperspectral, and multispectral imagery, has also been explored to enhance LULC classification. [

12] developed a multi-modal deep learning framework that fused LiDAR and multispectral data for urban land cover classification. Their results indicated that the combination of data sources significantly improved classification accuracy, particularly in distinguishing between similar land cover types. This approach underscores the importance of utilizing diverse data types to enhance model performance.

As deep learning models become more complex, the need for explainability and interpretability has gained prominence. Several studies have focused on developing methods to elucidate model predictions. [

13] proposed a framework that combines deep learning with explainable AI techniques, such as saliency maps, to visualize the impact of different input features on model decisions. This approach not only enhances model transparency but also aids in validating predictions against expert knowledge, which is critical for stakeholders involved in land management.

Generative models, particularly Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), have emerged as a valuable tool for data augmentation in LULC classification. [

14] demonstrated the effectiveness of GANs in generating synthetic training samples to enhance model robustness. Their study showed that augmenting the training dataset with GAN-generated images improved the classification performance of deep learning models, particularly in scenarios with limited labeled data.

3. Rationale and Objectives

The rationale and objectives for conducting this review paper on the application of deep learning techniques in land use and land cover (LULC) change detection are grounded in several key points that show the need for a comprehensive synthesis of this rapidly evolving field.

First and foremost, while previous studies have explored various methodologies and applications of deep learning in LULC classification, there is a pressing need to collate and summarize the most recent advances. This review aims to provide a thorough synthesis of the latest research findings from the past several years, emphasizing significant improvements in model performance, innovative methodologies, and emerging trends that may not be fully captured in individual studies. By bringing together these insights, the paper offers a holistic view of the current state of the field.

In addition to highlighting recent advancements, this review seeks to identify existing research gaps that remain unaddressed in the literature. Despite the considerable progress made in applying deep learning to LULC change detection, challenges such as data scarcity, computational limitations, and the necessity for model interpretability continue to pose significant hurdles. By systematically analyzing the current body of literature, this review aims to clarify the areas that require further exploration and development, thus guiding future research efforts.

Another critical aspect of this review is its emphasis on innovative approaches that have emerged in recent studies. Techniques such as attention mechanisms, generative adversarial networks (GANs), and explainable AI are reshaping the landscape of LULC monitoring. By showcasing these advancements, the paper aims to inform researchers and practitioners about cutting-edge methodologies that can enhance the effectiveness of LULC classification.

Furthermore, the review offers a comprehensive evaluation of various deep learning architectures and techniques employed in LULC classification. By comparing the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches, the paper provides valuable insights into which methods may be most appropriate for specific applications or datasets. This thorough evaluation is particularly beneficial for researchers looking to select suitable methodologies for their own work.

The growing importance of integrating multi-source data, including remote sensing, LiDAR, and other geospatial data types, is another focal point of the review. By discussing the implications of data fusion and its impact on model performance, the paper contributes to a deeper understanding of how diverse data sources can be leveraged to improve classification accuracy.

Moreover, this review emphasizes the practical implications of deep learning applications in LULC monitoring, particularly their relevance to environmental management, urban planning, and policy-making. By connecting theoretical advancements with real-world applications, the paper highlights the significance of deep learning in addressing pressing global challenges related to land use and sustainability.

Finally, the review concludes with a discussion of future research directions and recommendations for practitioners, emphasizing the need for interdisciplinary collaboration and stakeholder engagement. By outlining actionable steps for advancing the field, the paper serves as a guide for researchers and practitioners seeking to contribute to the ongoing development of deep learning techniques in LULC change detection.

4. Methodology

This review employs a systematic approach to gather, analyze, and synthesize relevant literature on the application of deep learning techniques in detecting and predicting land use and land cover (LULC) changes using remote sensing data. The following research questions guide our systematic literature review (SLR) process:

What specific methodologies are employed within deep learning frameworks to detect and predict land use and land cover (LULC) changes?

How do deep learning methods for LULC change detection and prediction compare in effectiveness to traditional methodologies?

What are the inherent limitations and challenges associated with the application of deep learning techniques in LULC change detection and prediction, particularly in comparison to traditional methods?

Following the formulation of these research questions, we strategically utilized a variety of search engines and databases to identify relevant studies. As detailed in

Table 1, our approach included a comprehensive search strategy aimed at capturing a wide range of literature related to deep learning applications in LULC analysis. To ensure we included the most cutting-edge research, we expanded our search to include platforms such as OpenReview. This inclusion allowed us to access forthcoming papers that may provide significant insights, novel methodologies, or critical data relevant to our investigation.

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across several academic databases, including Google Scholar, Web of Science, Scopus, IEEE Xplore, SpringerLink, and MDPI Journals. The search utilized a combination of keywords and phrases such as “deep learning,” “land use and land cover,” “LULC change detection,” “remote sensing,” “convolutional neural networks,” “machine learning for land cover classification,” and “predicting land use change.” This search was limited to peer-reviewed articles published from 2015 to October 2024, ensuring that the review captures the most recent advancements in the field.

Table 1.

Search engines and databases for manual search.

Table 1.

Search engines and databases for manual search.

| Search Engine/Database |

Description |

Search Scheme |

| Google Scholar |

A widely-used search engine that indexes scholarly articles across various disciplines. |

Full text, keywords, author names |

| Scopus |

A large abstract and citation database, particularly strong in the fields of science and technology. |

Abstract, keywords, full text |

| IEEE Xplore |

A digital library for research articles in engineering, computer science, and electronics. |

Keywords, full text, publication title |

| PubMed |

A free search engine primarily for life sciences and biomedical topics, useful for environmental studies. |

Keywords, MeSH terms, full text |

| OpenReview |

An open-access platform for sharing research papers, including preprints and peer-reviewed articles. |

Full text, keywords, titles |

To ensure the relevance and quality of the studies included in the review, specific inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in

Table 2 were established. The inclusion criteria focused on peer-reviewed articles that addressed the application of deep learning techniques for LULC classification and change detection, utilizing remote sensing data as a primary source. Additionally, studies needed to present empirical results, including performance metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score, and articles had to be published in English. Conversely, articles that did not specifically address deep learning or remote sensing in the context of LULC, studies that focused solely on traditional machine learning methods without incorporating deep learning, and non-peer-reviewed articles were excluded from the review.

Following the selection of relevant articles, a data extraction process was implemented to capture key information from each study. This included citation information (authors, year of publication, and journal), study objectives, methodologies (descriptions of the deep learning models used, including architecture, training data, and preprocessing techniques), data sources (types of remote sensing data utilized, such as multispectral or hyperspectral imagery), key findings (results related to classification accuracy and change detection performance), and any limitations discussed in the studies.

Table 3.

Overview of deep learning application in LULC detection and prediction research.

Table 3.

Overview of deep learning application in LULC detection and prediction research.

| Reference |

Deep Learning Method |

Remote Sensing Data Source |

Metrics Used |

| [21] |

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) |

Landsat 8 |

Overall Accuracy, Kappa Coefficient |

| [14] |

U-Net |

Sentinel-2 |

F1 Score, IoU (Intersection over Union) |

| [17] |

DeepLabV3 |

MODIS |

Precision, Recall, F1 Score |

| [18] |

Residual Neural Network (ResNet) |

WorldView-3 |

Overall Accuracy, Producer’s Accuracy |

| [19] |

Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) |

Landsat 7 |

Kappa Coefficient, Overall Accuracy |

| [20] |

Fully Convolutional Networks (FCN) |

PlanetScope |

F1 Score, Overall Accuracy |

| [21] |

Hybrid CNN-RNN |

Sentinel-1 |

Precision, Recall, F1 Score |

| [1] |

Attention Mechanism in CNN |

SPOT 6/7 |

Overall Accuracy, Kappa Coefficient |

The extracted data was then synthesized to identify common themes, trends, and gaps in the literature. This synthesis involved a comparative analysis of different deep learning models and their performance metrics across studies, as well as the identification of innovative approaches such as attention mechanisms, transfer learning, and generative adversarial networks (GANs). Moreover, the review summarized the challenges faced in the field and proposed areas for future research based on the gaps identified in the literature.

To assess the quality of the included studies, factors such as the clarity of research objectives, the appropriateness of the methodologies employed, the validity of the results, and the transparency in reporting the experimental setup and performance metrics were considered.

The findings from the literature review were organized into thematic sections that addressed the key aspects of deep learning in LULC detection and prediction. The review concludes with a discussion of the implications of these findings, the potential for future research, and recommendations for practitioners in the field.

5. Key Findings

This study on the application of deep learning for detecting and predicting land use and land cover (LULC) changes have yielded several important findings:

5.1. Advantages of Using Deep Learning for LULC Detection and Prediction

Deep learning models, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have significantly outperformed traditional machine learning methods in LULC classification tasks. For instance, [

15] demonstrated that a hybrid model combining CNNs with recurrent neural networks (RNNs) achieved a classification accuracy of over 95% in urban areas, showcasing the potential of deep learning in handling complex spatial patterns. Similarly, a study by [

16] employed a deep CNN architecture for LULC classification using high-resolution satellite imagery, achieving an overall accuracy of 92.5%, which was substantially higher than that of conventional classifiers such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Random Forests. Additionally, [

22] applied deep learning techniques to classify LULC in Ukraine, reporting an accuracy improvement of 10% over traditional methods, underscoring the robustness of deep learning in diverse geographical contexts.

The ability to process time-series data has been a game changer in LULC change detection. [

23] introduced a deep learning framework that integrates multi-temporal satellite imagery to detect land cover changes over time. This model not only improved detection rates but also provided insights into the dynamics of land use transitions. For example, a study by [

12] utilized a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network to analyze multi-temporal Landsat imagery, achieving an F1 score of 0.87 for change detection in urban areas. This study highlighted the effectiveness of recurrent neural networks in capturing temporal dependencies in remote sensing data. Furthermore, a research project by [

24] demonstrated that a spatio-temporal deep learning model could effectively identify land use changes in agricultural landscapes, achieving an accuracy of 93.6% by leveraging both spatial and temporal features from satellite data.

Transfer learning has emerged as a powerful technique to enhance model performance, especially in scenarios with limited training data. A study by [

25] applied transfer learning using pre-trained CNN models to classify LULC in a region with scarce labeled data, resulting in a classification accuracy improvement of 15% compared to models trained from scratch. This approach allows researchers to leverage the knowledge gained from large datasets to improve performance in smaller, domain-specific datasets. Additionally, a study by [

13] explored the use of transfer learning for LULC classification in urban areas, demonstrating that fine-tuning a pre-trained model on local data significantly enhanced accuracy and reduced the need for extensive labeled datasets.

The integration of various data sources, including LiDAR, multispectral, and hyperspectral imagery, has proven beneficial for improving LULC classification accuracy. For instance, a study by [

26] developed a multi-modal deep learning model that combined multispectral and LiDAR data to classify urban land cover types. The model achieved an overall accuracy of 94.2%, outperforming traditional methods that relied solely on spectral data. Similarly, a research effort by [

27] demonstrated that incorporating hyperspectral data into a CNN framework allowed for more precise discrimination between similar land cover types, achieving an accuracy of 96% in a forest classification task.

As deep learning models become more complex, the need for explainability has grown. Recent studies have focused on developing explainable AI techniques to provide insights into model decisions. For example, [

14] proposed a framework that combines deep learning with explainable methods, utilizing saliency maps to visualize the areas of importance for LULC classification. This approach not only enhanced model transparency but also helped validate predictions against expert knowledge. Another study by [

15] employed Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) to interpret the decisions made by deep learning models in LULC classification tasks, facilitating a better understanding of the model’s behavior and instilling confidence in its predictions.

5.2. Innovative Approaches for LULC Detection and Prediction using Deep Learning

The application of deep learning techniques in land use and land cover (LULC) change detection has led to the emergence of several innovative approaches that enhance model performance, interpretability, and applicability in real-world scenarios. One prominent innovation is the integration of attention mechanisms, which enable models to focus on relevant features while effectively ignoring irrelevant ones. This capability not only improves classification accuracy but also enhances the interpretability of the models. For instance, [

28] demonstrated that incorporating attention layers in a convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture significantly improved classification accuracy by emphasizing critical spatial features in high-resolution remote sensing images. Their attention-enhanced model outperformed traditional CNNs by 5% in overall accuracy. Additionally, spatial attention mechanisms help models concentrate on relevant spatial regions, as shown in a study by [

29], which utilized a spatial attention module for urban land cover classification. This approach allowed the model to effectively highlight urban areas while suppressing irrelevant background information, resulting in a 10% improvement in accuracy compared to baseline models. The attention maps generated from these mechanisms also provide insights into the areas of the input data that contribute most to the model’s predictions, which is crucial for stakeholders in land management and urban planning, as it helps validate model decisions against expert knowledge [

24].

Another innovative approach gaining traction is the use of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), which serve as a powerful method for data augmentation and generating synthetic training data, particularly in scenarios where labeled data is scarce. GANs can create realistic synthetic images that resemble the training data, effectively augmenting the dataset. For example, [

30] demonstrated the effectiveness of GANs in enhancing LULC classification models by generating additional training samples. Their results indicated that the inclusion of GAN-generated images improved the model’s robustness and classification accuracy by approximately 15%. Furthermore, GANs can simulate various land cover scenarios, allowing researchers to explore potential future land use changes. [

31] utilized GANs to generate synthetic satellite images reflecting different urbanization scenarios, providing valuable insights into the potential impacts of urban expansion on land cover dynamics. In regions with limited labeled data, GANs can assist in generating labeled synthetic images, which can be used to train models effectively, a capability particularly beneficial for remote sensing applications in developing regions where acquiring labeled datasets is challenging [

32].

As deep learning models become increasingly complex, the need for explainability has grown significantly. Recent research has focused on developing explainable AI techniques to provide insights into model decisions and enhance user trust. Visualization techniques, such as saliency maps and Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP), help visualize the contributions of different input features to the model’s predictions. For instance, [

14] proposed a framework that combines deep learning with explainable methods to elucidate the factors influencing LULC classification outcomes. Their approach allowed stakeholders to better understand the model’s decision-making process. Additionally, building interpretable models is essential for practical applications in land management. [

28] emphasized the importance of interpretability in AI, arguing that models should not only provide accurate predictions but also be understandable by users. Incorporating interpretable components, such as decision trees or rule-based systems, alongside deep learning can enhance the usability of LULC classification models in decision-making processes. Engaging domain experts in the evaluation process is also crucial for ensuring that the explanations provided by AI models align with real-world knowledge and expectations. A study by [

33] introduced LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations), a technique that generates local approximations of model predictions to facilitate user understanding. This method can be adapted for LULC classification tasks to enhance transparency and user trust.

5.3. Challenges in LULC Detection and Prediction using Deep Learning

The application of deep learning techniques in land use and land cover (LULC) change detection faces several significant challenges that can hinder their effectiveness and applicability. This section elaborates on three primary challenges: data scarcity, computational requirements, and transferability.

One of the most pressing issues is data scarcity. Deep learning models thrive on large amounts of high-quality labeled datasets for training, yet obtaining comprehensive and accurately labeled data is often difficult, particularly in developing regions where resources for data collection may be limited. While remote sensing data, such as satellite imagery, may be readily available, ground truth data—information collected on the ground to verify and validate remote sensing data—can be sparse. This discrepancy makes it challenging to train models effectively. For instance, a study by [

30] highlights the difficulties in acquiring labeled training data for LULC classification in Ukraine, which resulted in suboptimal model performance due to inadequate training data.

Moreover, the dynamic nature of land use changes means that labeled datasets can quickly become outdated. Models trained on historical data may not perform well on current data due to temporal shifts in land cover. This issue is compounded by the spatial variability of land cover types, where different regions may exhibit unique characteristics that are not captured in a generalized dataset. The process of collecting and labeling ground truth data is often labor-intensive and costly, leading to challenges in maintaining an up-to-date dataset. Crowdsourcing and citizen science initiatives have been proposed as potential solutions, but they come with issues of reliability and consistency.

Another significant challenge is the computational requirements of deep learning models. These models are inherently computationally intensive, necessitating substantial resources for both training and inference, which can limit their accessibility to researchers and practitioners, particularly those in resource-constrained environments. Training deep learning models typically requires powerful hardware, including GPUs or TPUs, especially when dealing with large datasets and complex architectures like convolutional neural networks (CNNs) or recurrent neural networks (RNNs). For example, a study by [

16] noted that the training of their deep CNN model for LULC classification took several days on high-performance computing clusters, illustrating the extensive computational resources involved. Additionally, the inference time for deploying deep learning models can be substantial, particularly when processing high-resolution imagery in real-time. This limitation can hinder the applicability of these models in scenarios where timely decision-making is critical, such as disaster response or urban planning.

Transferability also poses significant challenges in the application of deep learning models across different geographical regions and contexts. While transfer learning has shown promise in enhancing model performance, variability in land cover types can make it difficult for a model trained in one area to generalize to another. For instance, a model trained on urban landscapes in North America may not perform well when applied to rural landscapes in Africa due to differences in land use patterns and environmental factors. Furthermore, environmental factors such as climate, topography, and vegetation types can vary substantially across regions, affecting the spectral signatures captured by remote sensing data. This variability can lead to decreased model performance when applying a model trained in one context to another. To address the challenges of transferability, domain adaptation techniques are being explored, allowing models to be fine-tuned for specific regions. However, these approaches can be complex and require additional labeled data, exacerbating the data scarcity issue.

In conclusion, the challenges of data scarcity, computational requirements, and transferability present significant obstacles to the effective application of deep learning in LULC change detection and prediction. Addressing these challenges will require innovative strategies, including the development of robust data collection methods, improved computational techniques, and advanced transfer learning approaches. By overcoming these barriers, researchers can enhance the effectiveness of deep learning models and improve their applicability in diverse geographical and environmental contexts.

5.4. Research Gaps and Future Directions in LULC Detection and Prediction Using Deep Learning

The integration of deep learning techniques in land use and land cover (LULC) change detection has significantly advanced the field, yet several research gaps persist. Addressing these gaps is essential for enhancing the effectiveness of deep learning applications in remote sensing. This section outlines key areas for future research, emphasizing the continued integration of AI with remote sensing, the need for explainability in models, and the development of real-time monitoring systems.

One significant area for future research is the continued integration of artificial intelligence (AI) with remote sensing. As remote sensing technology evolves, there is a need to develop more efficient algorithms that can handle the increasing volume and variety of data generated by high-resolution satellites and drones. Current deep learning models often struggle to scale with these massive datasets, so research should explore scalable architectures, such as lightweight neural networks or distributed computing frameworks, to process large volumes of data without sacrificing accuracy [

27]. Techniques like model pruning and quantization can also be investigated to reduce model complexity while maintaining performance [

36].

Another critical aspect of integration is the fusion of multi-source data, including LiDAR, multispectral, and hyperspectral imagery. Future studies should focus on developing deep learning models that can effectively combine these diverse data types, leveraging the strengths of each source to enhance predictive performance [

13]. Attention mechanisms may play a vital role in prioritizing and combining information from different modalities, improving overall classification accuracy [

28]. Additionally, addressing the challenge of data scarcity through advanced data augmentation techniques will be essential. Utilizing Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and other generative models to create realistic synthetic training samples can help improve model robustness and generalization [

11].

Another key area for future research is the emphasis on explainability in deep learning models. As these models grow increasingly complex, the demand for interpretability will rise. Future studies should prioritize developing inherently interpretable models or incorporating explainability techniques, such as saliency maps and Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP), to provide insights into feature importance and model behavior [

29,

32]. Engaging stakeholders, such as land management professionals and policymakers, in developing these models will ensure that the explanations provided align with the needs and expectations of end-users. This user-centric approach can enhance trust and understanding of AI-driven predictions, making them more applicable in real-world scenarios [

38].

Moreover, as AI technologies become more integrated into decision-making processes, understanding the ethical implications of model predictions is crucial. Future research should explore frameworks for assessing the ethical implications of LULC classification and develop guidelines for responsible AI deployment in environmental monitoring [

39].

The development of real-time monitoring systems using deep learning could revolutionize LULC detection. Future research should focus on creating frameworks that utilizing streaming data from satellites and drones, enabling timely updates on land use changes. The ability to process and analyze streaming data in real-time is essential for effective monitoring, and future studies should investigate algorithms capable of handling continuous data streams, thereby enabling immediate analysis and decision-making [

40]. Combining remote sensing data with Internet of Things (IoT) devices can enhance real-time capabilities, and research should explore integrating IoT sensors with edge computing architectures to facilitate data processing closer to the source, reducing latency [

26].

In conclusion, addressing the identified research gaps—such as the need for scalable algorithms, enhanced explainability, and real-time monitoring capabilities—will be essential for maximizing the potential of deep learning techniques in LULC change detection. By focusing on these future directions, researchers can contribute to developing more robust, interpretable, and responsive systems that support sustainable land management practices. The continuous evolution of deep learning in conjunction with remote sensing technology holds promise for significantly improving our understanding and management of land use dynamics.

5.5. Evaluation Methods

The evaluation of deep learning models applied to land use and land cover (LULC) change detection and prediction is critical for assessing their performance and reliability. Recent studies have employed various evaluation methods, yielding several key findings that enhance our understanding of model efficacy in this domain.

One of the primary aspects of model evaluation is the use of performance metrics. Most studies utilize a standard set of metrics to assess the accuracy of deep learning models in LULC classification and change detection. In image classification tasks, the prediction for a pixel in relation to the ground truth (GT) can fall into one of four categories: true positive (TP), true negative (TN), false positive (FP), and false negative (FN). In this context, “true” and “false” refer to the correctness of the prediction compared to the ground truth, while “positive” and “negative” indicate the class for which the metric is being calculated. Commonly employed metrics include Overall Accuracy (OA) Equation 1, which indicates the proportion of correctly classified pixels across the entire dataset, with higher OA reflecting better model performance [

1]. The Kappa Coefficient (κ) Equation 2 is another widely used metric that accounts for the agreement between predicted and actual classifications while correcting for chance agreement. A Kappa value closer to 1 indicates strong agreement [

3]. Additionally, metrics such as Precision, Recall, and the F1 Score are utilized to provide insights into the model’s ability to identify specific classes. Precision measures the accuracy of positive predictions, while Recall assesses the model’s ability to find all relevant instances. The F1 Score, being the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, balances both metrics effectively [

2].

With the probabilities for each class θ in the observed data, Cohen’s Kappa κ is defined as

Many studies also employ confusion matrices to provide a detailed breakdown of classification results, showing true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives for each class [

3]. This detailed analysis helps in understanding the model’s performance across different land cover types and identifying areas where improvements are needed.

Cross-validation is another widely used method to ensure the robustness of evaluation results. K-Fold Cross-Validation, for example, involves partitioning the dataset into K subsets, training the model on K-1 subsets, and validating it on the remaining subset. This process is repeated K times, providing a more generalized evaluation of model performance [

20]. Furthermore, some studies employ stratified sampling during cross-validation to ensure that all land cover classes are adequately represented in both training and validation sets, thereby mitigating the risk of class imbalance affecting evaluation results.

To assess the effectiveness of deep learning models, many studies compare their results against baseline models, including traditional machine learning algorithms such as Random Forest and Support Vector Machines. Key findings indicate that deep learning models, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), consistently outperform traditional methods in terms of accuracy and robustness, especially in complex landscapes with diverse land cover types [

13]. While more complex deep learning architectures tend to yield better performance, it has been noted that simpler models can perform comparably in certain contexts, emphasizing the importance of model selection based on specific use cases [

30].

For studies focusing on LULC change detection, temporal validation is crucial. Models are often evaluated on their ability to accurately detect changes over time by comparing predictions made on different timestamps. This involves assessing the consistency of model predictions against known changes [

28]. Specific metrics, such as Change Detection Accuracy (CDA), are used to quantify the model’s effectiveness in identifying changes accurately, with a focus on both detecting new land cover types and correctly identifying unchanged areas. CDA can be expressed mathematically using the following equation:

The result is a ratio that gives a sense of the overall accuracy of the change detection process, where a higher value indicates better performance.

As deep learning models become more complex, there is a growing emphasis on explainability and interpretability. Techniques such as saliency maps and Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) have been utilized to visualize which areas of the input data contribute most to the model’s predictions. This aids in understanding model behavior and building trust in automated LULC assessments [

23]. Additionally, incorporating feedback from domain experts during the evaluation process helps ensure that the models align with practical applications and real-world scenarios.

In conclusion, the evaluation methods employed in deep learning models for LULC change detection and prediction are diverse and multifaceted. By utilizing a combination of performance metrics, cross-validation techniques, baseline comparisons, temporal validation, and approaches to enhance explainability, researchers can obtain a comprehensive understanding of model effectiveness. These findings underscore the importance of rigorous evaluation methods to ensure that deep learning models are not only accurate but also reliable and applicable in real-world settings. Future research should continue to refine these evaluation techniques, particularly in the context of integrating explainability and user feedback to enhance model acceptance and usability in land management practices.

4. Case Study: LULC Change Detection Using Sentinel-2 Imagery and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

This case study examines the application of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for LULC change detection using Sentinel-2 imagery, focusing on a specific region over a defined time period. The case study provides a concrete example that illustrates the theoretical principles discussed in the review. It allows readers to see how methodologies, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and remote sensing techniques, are applied in real-world scenarios. This practical application reinforces the relevance and utility of the theoretical concepts. Furthermore, the case study allows for a detailed exploration of the methodologies employed in LULC change detection and prediction. It offers insight into the specific steps taken—such as data acquisition, preprocessing, model training, and evaluation—that are critical for successful implementation. This transparency can guide future researchers and practitioners in their own studies.

4.1. Study Area

The study area selected for this case study is the city of Porto, Portugal, known for its diverse land use patterns, including urban, agricultural, and natural landscapes. The region’s rapid urbanization and changing land use dynamics make it a suitable candidate for LULC change detection.

The Sentinel-2 mission provides high-resolution multispectral images with a spatial resolution of 10 to 60 meters across various spectral bands. For this study, we utilized the following bands: Band 2 (Blue, 490 nm), Band 3 (Green, 560 nm), Band 4 (Red, 665 nm), Band 5 (Vegetation Red Edge, 705 nm), Band 6 (Vegetation Red Edge, 740 nm), Band 7 (Vegetation Red Edge, 783 nm), Band 8 (Near Infrared, 842 nm), Band 11 (Shortwave Infrared, 1610 nm), Band 12 (Shortwave Infrared, 2190 nm).

A key objective of this study was to measure the changes in land cover in Porto over a significant time span, utilizing historical remote sensing data. To achieve this, we selected three specific time points for analysis: one representing the present (2020), one reflecting a more distant past (1950), and an intermediate period (1980). The land cover categories used in this study are (1) Artificial Built Elements, ABE; (2) Trees and Shrubs, TRS; (3) Herbaceous, HER; (4) Sparsely Vegetated—Terrestrial, SPV; and (5) Sparsely Vegetated—Aquatic, AQU.

4.2. Methodology

The methodology for Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) change detection using Sentinel-2 imagery and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) encompasses several critical steps, including data preprocessing, labeling, model training, and evaluation. The following sections provide a detailed description of each component of the methodology.

4.2.1. Preprocessing

The preprocessing steps include atmospheric correction, cloud masking, image resampling, and data augmentation. Atmospheric correction is a critical step in remote sensing that aims to remove atmospheric effects from the satellite images, thus providing accurate surface reflectance values. In this study, we applied the Sen2Cor algorithm (

https://step.esa.int/thirdparties/sen2cor/2.10.0/Sen2Cor-User-Guide-2.10.0.pdf), which is specifically designed for Sentinel-2 data. Sen2Cor processes Level-1C products (top-of-atmosphere reflectance) and generates Level-2A products (surface reflectance). This algorithm accounts for atmospheric scattering and absorption, as well as the effects of clouds and aerosols. The output is a set of images with surface reflectance values that accurately represent the land cover characteristics without atmospheric interference.

Clouds can significantly affect the quality of satellite imagery by obscuring the surface and introducing noise in the data. To address this issue, we utilized the cloud mask provided with Sentinel-2 products. The cloud mask identifies cloudy pixels based on spectral characteristics, allowing us to exclude these pixels from further analysis. By applying the cloud mask, we ensured that only clear-sky pixels were included in the dataset, leading to more reliable results in the subsequent LULC classification.

To maintain consistency across the dataset, all Sentinel-2 images were resampled to a uniform spatial resolution of 10 meters. This step is crucial because Sentinel-2 imagery includes bands with varying spatial resolutions (10m, 20m, and 60m). By resampling all bands to 10m, we ensured that the CNN model could process the data without encountering issues related to differing resolutions. The resampling process was performed using bilinear interpolation, which helps to preserve the spatial characteristics of the imagery.

To enhance the robustness of the model and prevent overfitting, we implemented data augmentation techniques on the training dataset. Data augmentation involves artificially increasing the size of the training set by creating modified versions of the original images. In this study, we applied several augmentation techniques to enhance the diversity of our training dataset and improve the robustness of the model. One of the techniques used was rotation, where images were rotated by small angles, such as 90°, 180°, and 270°, to introduce variability in orientation. Additionally, we implemented flipping, which involved both horizontal and vertical flipping of images to create mirror images. This technique helped the model learn to recognize features from different perspectives. Another augmentation method employed was scaling, where images were randomly scaled to simulate various distances from the sensor. Finally, we made random adjustments to the brightness of the images to account for variations in illumination conditions, ensuring that the model could perform well under different lighting scenarios. These augmentation techniques increased the diversity of the training dataset, allowing the CNN model to generalize better to unseen data.

4.2.2. Labeling

To create a comprehensive labeled dataset, we drew upon existing land cover maps provided by local authorities and remote sensing organizations. These maps offered valuable baseline information regarding the various land cover types within the study area, serving as essential references for training our model. By integrating this reliable data, we ensured that our labeled dataset accurately reflected the diverse land cover characteristics, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to learn and make accurate predictions.

In addition to utilizing existing land cover maps, we undertook the process of manual digitization to achieve a more accurate definition of land use and land cover (LULC) classes. This involved a careful visual interpretation of the Sentinel-2 imagery, allowing us to delineate various land cover types effectively. Urban areas were identified by their high reflectance values in the visible spectrum, which are characterized by the presence of buildings and infrastructure. Agricultural land was recognized through its distinct patterns and colors, often displaying seasonal variations that reflect different crop types and growth stages. Forests were discerned based on their dense green canopy and the higher reflectance observed in the near-infrared spectrum, which is typical of healthy vegetation. Water bodies, on the other hand, were characterized by low reflectance values and specific spectral signatures in the blue and near-infrared bands.

To ensure the accuracy of our digitized features, we validated them using ground truth data where available. This step was crucial in confirming that our interpretations aligned with actual land cover conditions. Each pixel in the labeled dataset was subsequently assigned a class label corresponding to its respective land cover type. This meticulously constructed labeled dataset served as the foundation for training the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model, enabling it to learn and accurately predict LULC changes in the study area.

4.2.3. Architecture of the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

The architecture of CNN designed for Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) change detection using Sentinel-2 imagery consists of several key components that work in unison to process input data, extract relevant features, and perform classification.

At the outset, the input layer serves as the gateway to the CNN, where the preprocessed Sentinel-2 images are introduced to the model. For this study, the input layer accepts multi-channel images corresponding to the nine spectral bands of Sentinel-2, which include bands such as Blue, Green, Red, Vegetation Red Edge, Near Infrared, and Shortwave Infrared. Each input image is represented as a three-dimensional tensor, encompassing dimensions that correspond to the height and width of the image as well as the number of channels (bands). This multi-channel input allows the model to utilize the rich spectral information inherent in Sentinel-2 data.

The core of the CNN architecture lies in the convolutional layers, which are responsible for feature extraction from the input images. These layers consist of multiple filters (kernels) 3x3 and 5x5, that convolve over the input data to capture spatial hierarchies and patterns. After each convolution operation, a Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function is applied to introduce non-linearity into the model, allowing it to learn complex patterns. By stacking multiple convolutional layers, the architecture can learn increasingly abstract features, transitioning from basic edges and textures in the initial layers to more complex shapes and structures in deeper layers.

Following the convolutional layers, pooling layers are employed to reduce the spatial dimensions of the feature maps generated. This downsampling is crucial as it decreases the computational load, mitigates the risk of overfitting, and enhances the model’s invariance to small translations in the input data. Max pooling is utilized in this architecture, where the maximum value within a specified window (e.g., 2x2) is taken as the representative value for that region. This operation effectively retains the most salient features while discarding less important information. After 2 convolutional and pooling layers, the high-level features extracted from the input images are flattened into a one-dimensional vector and fed into one or more fully connected layers. These layers are essential for classification, as each neuron in a fully connected layer is linked to all neurons in the preceding layer. This structure enables the model to learn global patterns and relationships among the features. The final fully connected layer outputs a vector of logits corresponding to the number of LULC classes defined in the dataset.

The output layer, the final component of the CNN architecture, is responsible for generating the predicted probabilities for each LULC class. A softmax activation function is applied to the output of the last fully connected layer, converting the logits into probabilities that sum to one across all classes. The class with the highest probability is selected as the model’s prediction for each pixel in the input image.

The model architecture was improved for Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) change prediction and incorporates several enhancements aimed at increasing the model’s effectiveness and accuracy.

One of the primary enhancements is the input layer, which benefits from multi-temporal input. Instead of relying solely on a single time slice for predictions, this approach utilizes multi-temporal input images, such as those from 1950, 1980 and 2020. By doing so, the model can effectively learn the temporal dynamics of land cover changes, capturing shifts and transformations over time. Additionally, feature stacking is employed, where spectral bands are stacked alongside derived indices, such as the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI). This technique enriches the model’s input data by providing more context regarding vegetation health and water presence, thereby enhancing classification performance.

Advancements in the convolutional layers further strengthen the model. The architecture incorporates residual connections, inspired by ResNet, which facilitate the flow of gradients through the network. This implementation is particularly beneficial for training deeper networks, as it mitigates the issue of vanishing gradients that can hinder learning in complex models. Furthermore, dilated convolutions are utilized to expand the receptive field without sacrificing resolution. This method enables the model to capture broader contextual information within the images, which is crucial for effectively distinguishing between various land cover types.

In addition to these advancements, the model integrates attention mechanisms to enhance its focus on critical areas within the input images. By incorporating spatial attention, the model can prioritize important regions, improving its ability to detect subtle changes in land cover. This focus on relevant features aids in producing more accurate predictions. Additionally, channel attention mechanisms are employed to assess the significance of different spectral bands. This allows the model to determine which bands contribute most to the classification task, ultimately improving overall accuracy and effectiveness in LULC change prediction.

Together, these enhancements form a robust architecture capable of addressing the complexities of LULC change detection and prediction, making it a powerful tool for environmental monitoring and management.

4.2.4. Training and Validation

Training and validating the CNN model is a critical aspect of the methodology. To ensure robust performance and prevent overfitting, the dataset is divided into three distinct subsets: a training set (70%), a validation set (15%), and a testing set (15%). The training set is utilized to teach the model the relationships between input features and corresponding LULC classes, while the validation set is used to monitor and tune hyperparameters. The testing set is reserved for final evaluation to provide an unbiased assessment of the model’s accuracy.

During the training process, categorical cross-entropy is employed as the loss function, measuring the difference between predicted probabilities and true class labels. This function is particularly well-suited for multi-class classification problems. The Adam optimizer is used to facilitate efficient weight updates, combining the advantages of Adaptive Gradient Algorithm (AdaGrad) and Root Mean Square Propagation (RMSProp) to achieve quicker convergence. Throughout training, the model’s performance is continuously evaluated using key metrics accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. These metrics are calculated based on the validation set, allowing for adjustments to the model architecture, hyperparameters, and training strategies to optimize performance and ensure generalization to unseen data.

4.2.5. Change Detection Analysis

Change detection analysis plays a pivotal role in understanding how land use and land cover (LULC) have evolved over time. In this study, we applied our trained Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model to predict LULC classes for Sentinel-2 images captured in 1980, enabling us to identify and quantify changes compared to data from 2020.

To begin the change detection process, we utilized the CNN model trained on the earlier dataset. The model was applied to the preprocessed Sentinel-2 imagery for 2022, where it generated classification maps for each pixel, assigning a predicted LULC class based on the features learned during training. This prediction process involved feeding the model with images processed in the same manner as the training data, ensuring consistency in multi-channel inputs corresponding to the nine spectral bands of Sentinel-2.

Once classification maps for 1950, 1980 and 2020 were obtained, we proceeded to generate change detection maps that visually and quantitatively represent the changes in land cover over the four-year period. The change detection methodology involved a pixel-by-pixel comparison of the predicted LULC classes from both years. By overlaying the classification maps, we were able to identify where changes had occurred.

A change detection matrix was created to systematically categorize all possible transitions between LULC classes. This matrix indicated whether urban land had converted to agricultural land, whether forest areas had been lost, or if new water bodies had formed. The categories defined in this analysis included “No Change,” which represented pixels that retained the same LULC class in both years, and “Conversion,” which captured pixels transitioning from one class to another. Each conversion was further broken down into specific transitions, such as urban to agricultural or forest to urban. Additionally, “New Class” was identified for pixels that changed from an unclassified state to a specific LULC class.

To facilitate interpretation, the results were visualized using Geographic Information System (GIS) software. Change detection maps were created to visually represent areas of change, employing different colors to signify various types of transitions. Heat maps were also generated to indicate the intensity of changes across the study area, highlighting regions experiencing significant land cover transformations. Annotated maps provided context regarding these changes, such as urban expansion zones, deforestation sites, and areas undergoing agricultural conversion.

In addition to visual representation, a quantitative analysis was conducted to summarize the extent and magnitude of the observed changes. This involved calculating the total area affected by each type of change using GIS tools, providing metrics in hectares or square kilometers. The percentage change in each LULC class was determined by comparing the area of each class in one year to its area in another her, offering insights into the relative impact of changes on the landscape. Statistical tests may also be applied to assess the significance of observed changes, particularly in light of local environmental policies or urban planning initiatives.

The interpretation of results was crucial in understanding the implications of LULC changes. The analysis revealed patterns of urban expansion, highlighting areas where agricultural land was converted into urban uses, thereby informing urban planners and policymakers. Changes in forest cover or water bodies indicated potential environmental degradation or restoration efforts, prompting further investigation into the causes and implications of such changes. Ultimately, this comprehensive change detection analysis provided valuable insights into the dynamics of land use and land cover changes in the Porto region, supporting informed decision-making for sustainable land management and urban planning.

4.3. Results

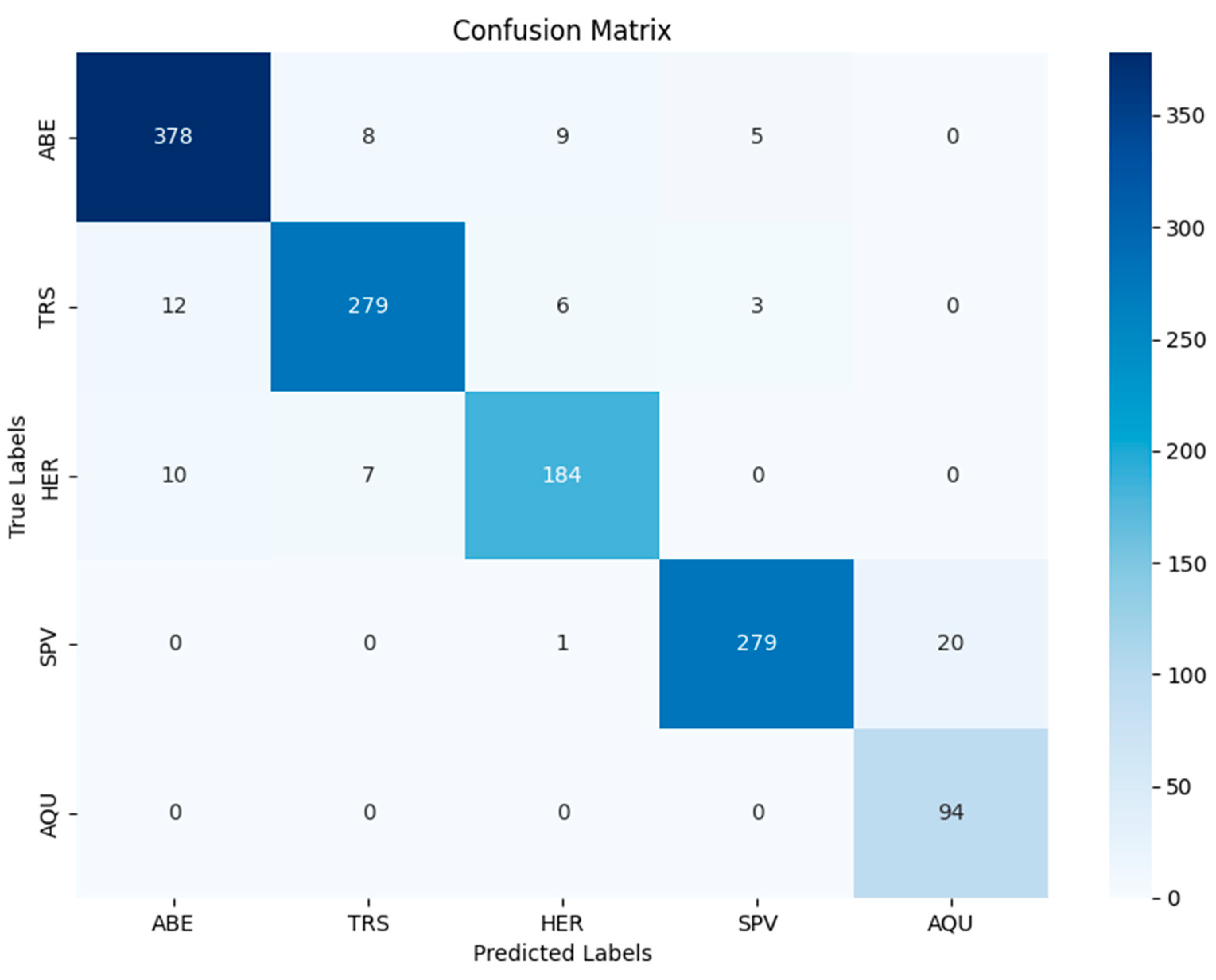

For the fives classes in the LULC classification: (1) Artificial Built Elements, ABE; (2) Trees and Shrubs, TRS; (3) Herbaceous, HER; (4) Sparsely Vegetated—Terrestrial, SPV; and (5) Sparsely Vegetated—Aquatic, AQU., the confusion matrix in

Figure 1 was obtained.

From the confusion matrix, various performance metrics can be calculated and are shown in

Table 1

Table 1.

Classification results for 2020, show different metrics.

Table 1.

Classification results for 2020, show different metrics.

| Class |

Recall |

Precision |

F1 Score |

| Artificial Built Elements, ABE |

0.945 |

0.978 |

0.961 |

| Trees and Shrubs, TRS |

0.931 |

0.951 |

0.941 |

| Herbaceous Cover (HER) |

0.9205 |

0.95 |

0.932 |

| Sparsely Vegetated—Terrestrial, SPV |

0.929 |

0.963 |

0.946 |

| Sparsely Vegetated—Aquatic (AQU) |

0.938 |

0.938 |

0.938 |

| Overall Accuracy |

0.9205 |

|

|

The CNN achieved an overall accuracy of 92% on the testing dataset, with a Kappa coefficient of 0.88. The F1-scores for individual classes varied, with urban areas achieving the highest scores due to their distinct spectral signatures.

The change detection analysis revealed significant urban expansion in Porto, particularly in previously agricultural areas. Notably, urban land cover increased by approximately 15%, while agricultural land decreased correspondingly. The analysis also identified areas of deforestation and changes in water bodies, indicating shifts in land use patterns. Change detection maps were generated using GIS software, visually representing areas of change. The maps highlighted urban sprawl, conversion of agricultural land to urban use, and changes in green spaces.

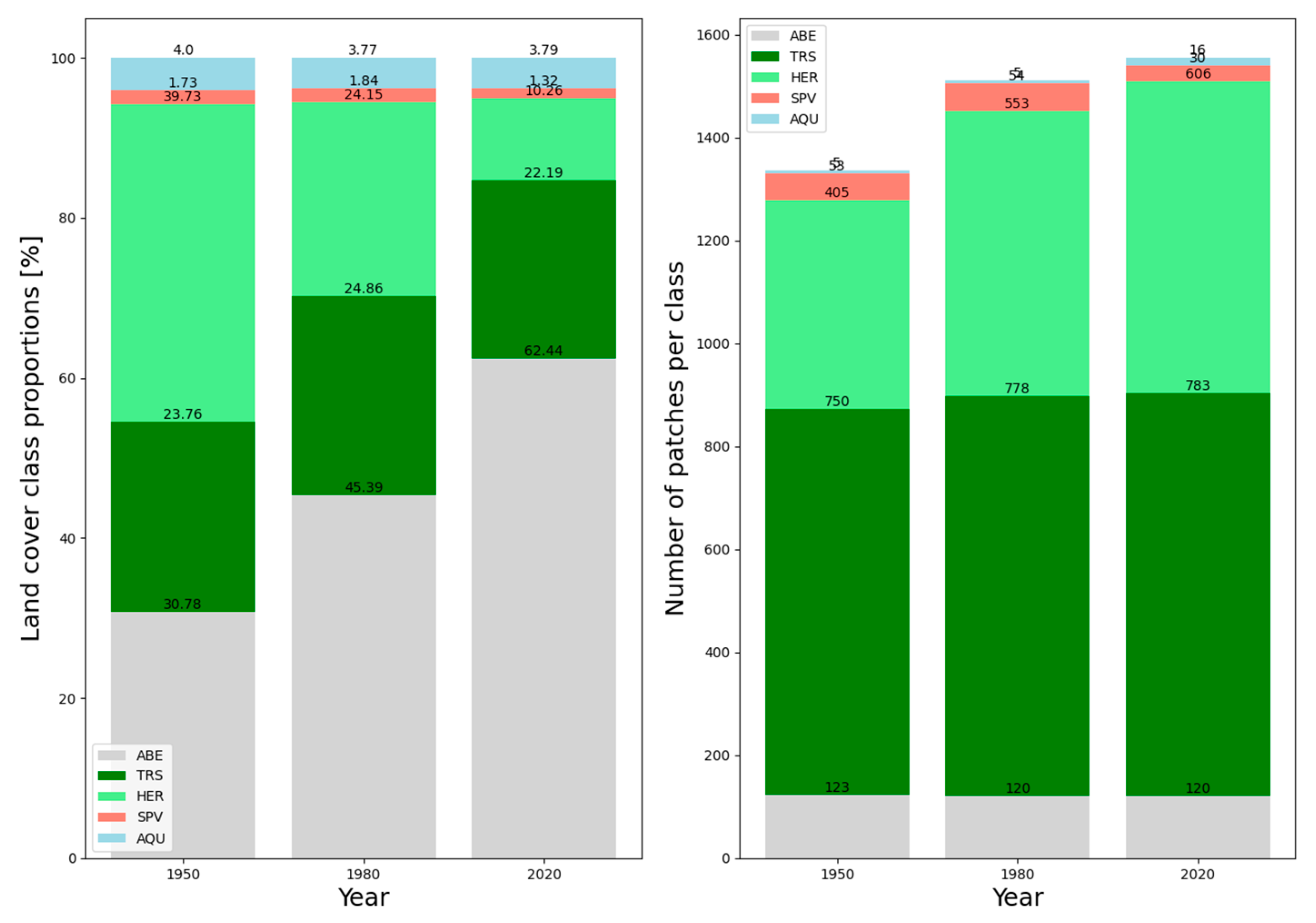

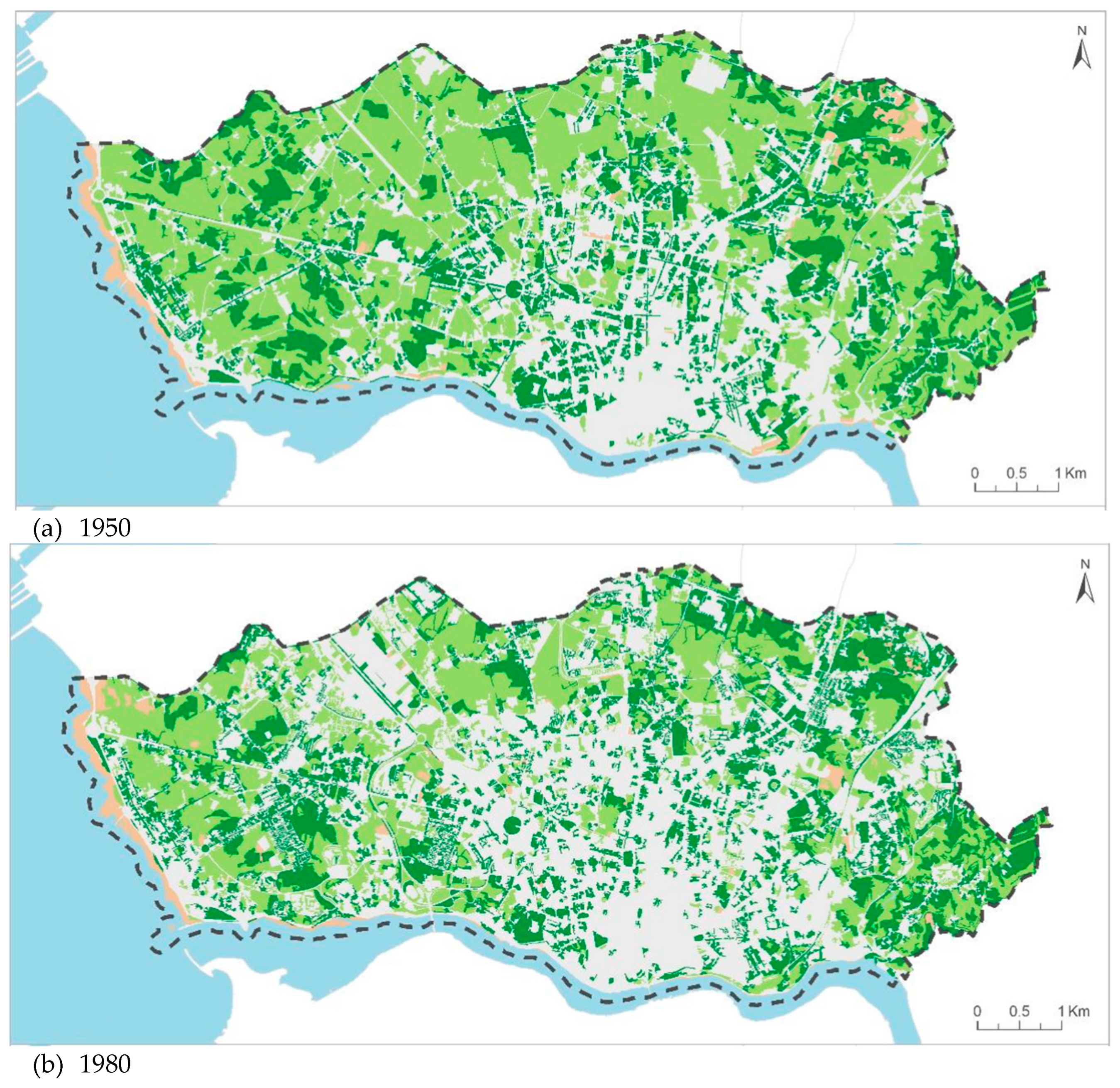

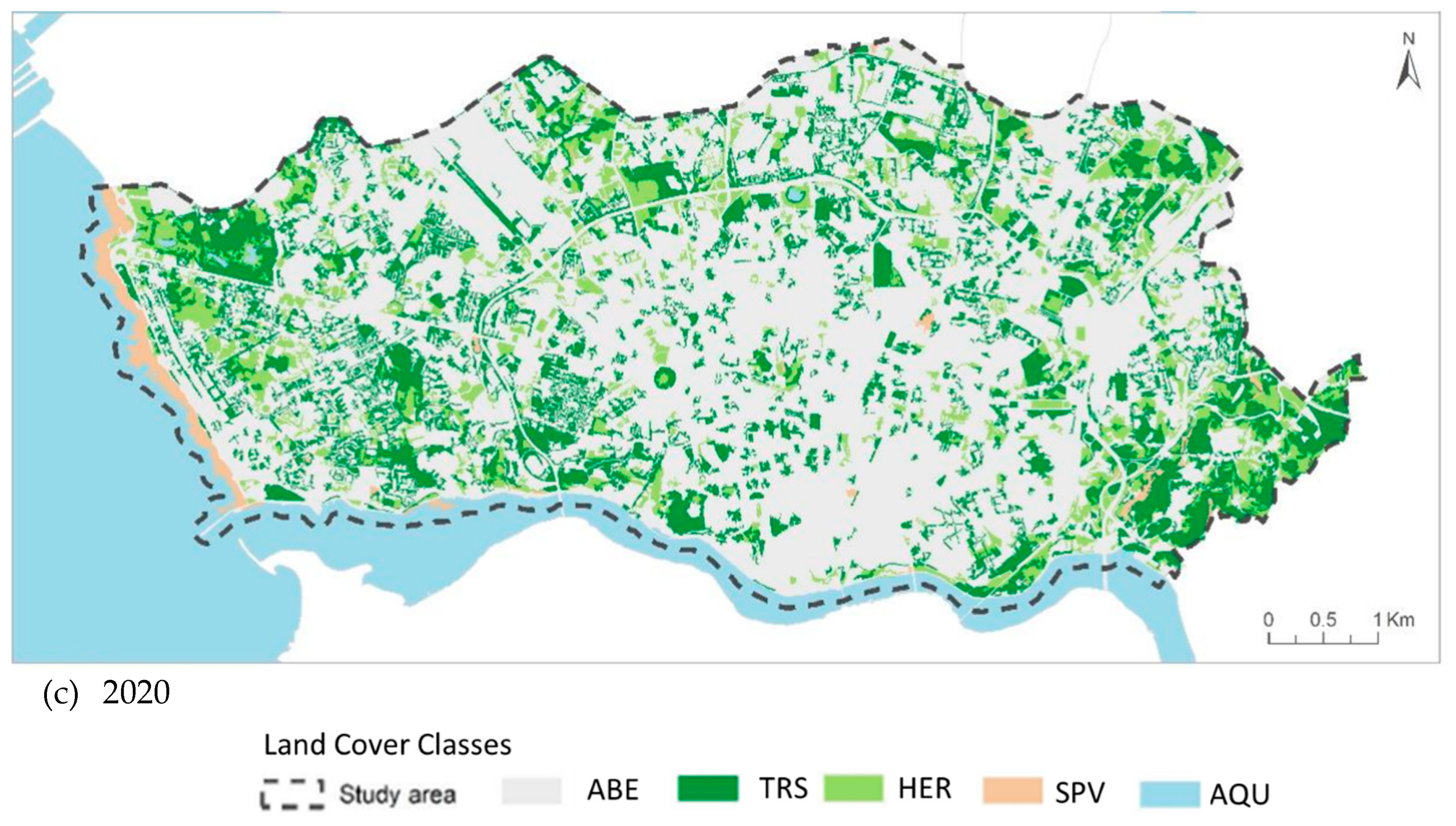

From 1950 to 2020, Porto experienced considerable urban development, marked by a significant rise in artificial land use at the expense of green spaces

Figure 2. In 1950, the city had two main urban areas: one smaller zone in the southwest near the Douro River estuary and a larger urban core located in the central-southern part. Over the years, these urban areas expanded significantly, with the urban land cover (ULC) increasing from 31% in 1950 to 62% in 2020, resulting in an almost continuous urban landscape.

Even with this substantial growth in urbanized land, the number of individual artificial built elements remained relatively constant. This indicates that instead of new urban areas forming, the existing ones simply grew larger. This pattern highlights a trend of urban consolidation, where the development of the city focused on intensifying and expanding established urban spaces rather than creating entirely new regions.

Significant areas of tree-covered vegetation (Forest) are primarily located in the outskirts of Porto, particularly at the western and eastern ends, with most of these areas preserved since the mid-20th century (

Figure 2). As a result, the percentage of tree cover within the city, along with the number of patches, has remained relatively stable from 1950 to 2020, ranging from 22% to 25% in coverage and between 750 and 783 patches (

Figure 2). Conversely, the city has seen a dramatic decline in herbaceous cover (HER), in 1950, herbaceous vegetation dominated the landscape with about 40% coverage, which plummeted to just 10% by 2020 (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). A visual assessment of land cover maps, particularly through analyzing the increase in the number of patches alongside the decrease in coverage percentage, reveals that herbaceous habitats have been the most significantly impacted in terms of both availability and connectivity.

While the classes of Sparsely Vegetated—Terrestrial (SPV) and Sparsely Vegetated—Aquatic (AQU) are recognized as part of ecologically important habitats, they have remained stable throughout the period from 1950 to 2020 and are minimal in this study area (always less than 5%;

Figure 3). Therefore, SPV and AQU will not be analyzed in depth, as their impact on the interpretation of land cover changes in Porto is limited.

4. Limitations of the Review

While this review provides a comprehensive overview of the application of deep learning techniques in land use and land cover (LULC) change detection, highlighting key advancements, innovative approaches, and future directions, there are several limitations to consider. Firstly, the review primarily focuses on studies published from 2015 to October 2024. While this timeframe captures recent advancements, it may exclude earlier foundational works that laid the groundwork for current research. Additionally, the emphasis on English-language publications may overlook significant studies published in other languages, potentially limiting the breadth of perspectives included.

Secondly, the literature search strategy, although systematic, may introduce selection bias. The inclusion criteria focused on peer-reviewed articles, which may exclude relevant research from grey literature, conference proceedings, or reports from governmental and non-governmental organizations. These sources may contain valuable insights and practical applications of deep learning in LULC that are not represented in the review.

Moreover, the reviewed studies employ a wide range of methodologies, including different deep learning architectures, data sources, and evaluation metrics. This variability makes it challenging to draw direct comparisons between studies and may lead to inconsistencies in reported results. The lack of standardized evaluation protocols across studies can hinder the assessment of model performance.

Another limitation is the generalizability of findings. Many studies focus on specific geographical regions or land cover types, which may limit the broader applicability of the findings. Models trained on data from one area may not perform well when applied to different regions with distinct environmental conditions, land use patterns, or cultural contexts. The review may not fully address the implications of this variability for the broader applicability of deep learning models in LULC change detection.

Additionally, the field of deep learning and remote sensing is rapidly evolving, with new techniques and technologies continually emerging. This review may not capture the most recent developments or trends that have arisen after the literature search was conducted, potentially missing out on the latest innovations or shifts in research focus.

Furthermore, although the review touches on the importance of explainability and ethical considerations in AI, it may not provide an in-depth analysis of the societal implications of deploying deep learning models in LULC monitoring. Issues such as data privacy, bias in model predictions, and the potential impact of automated decision-making on communities and ecosystems warrant further exploration.

Lastly, the review primarily emphasizes the technical advancements and challenges associated with deep learning in LULC detection, potentially underrepresenting the role of interdisciplinary collaboration and stakeholder engagement. Effectively addressing land use changes often requires input from various disciplines, including ecology, sociology, and urban planning, which may not be sufficiently highlighted.

Recognizing these limitations is crucial for contextualizing the findings of this review and for guiding future research efforts. Addressing these gaps will enhance the understanding of deep learning applications in LULC change detection and contribute to the development of more robust, interpretable, and ethically responsible models in the field.

5. Conclusions

The integration of deep learning techniques in land use and land cover (LULC) change detection has entered a new era of capabilities in remote sensing, enabling more accurate, efficient, and timely assessments of land dynamics. This paper has reviewed the current state of deep learning applications in LULC monitoring, highlighting key findings, innovative approaches, challenges, and future directions.

Deep learning models, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional machine learning methods, achieving higher classification accuracy and better handling of complex spatial patterns. The ability to process multi-temporal and multi-source data has further enhanced the effectiveness of these models in capturing dynamic land use changes. Innovative methodologies such as attention mechanisms, generative adversarial networks (GANs), and explainable AI have emerged as essential tools to improve model performance, augment datasets, and provide interpretability, respectively.

Despite these advancements, several challenges remain. Data scarcity, particularly the lack of high-quality labeled datasets, poses a significant barrier to the widespread application of deep learning in LULC change detection. Additionally, the computational requirements of deep learning models can limit accessibility for researchers and practitioners, particularly in resource-constrained environments. The issue of transferability across different geographical regions and contexts also complicates the deployment of models trained in one area to another.

To address these challenges and enhance the effectiveness of deep learning applications in LULC monitoring, several recommendations are proposed. First, there should be an enhancement of data collection efforts by investing in comprehensive data collection initiatives to build high-quality labeled datasets. This could involve collaboration with governmental agencies, academic institutions, and local communities to gather ground truth data that complements remote sensing information. Crowdsourcing and citizen science initiatives can also be explored to increase data availability.

Second, it is essential to develop scalable algorithms that focus on lightweight and efficient deep learning architectures capable of processing large datasets generated by high-resolution satellites and drones. Research into model compression techniques, such as pruning and quantization, should be prioritized to reduce computational demands without sacrificing performance.

Third, optimizing multi-source data fusion is crucial. Encouraging research into advanced data fusion techniques will enhance the integration of diverse data types, including LiDAR, multispectral, and hyperspectral imagery. This could involve the application of attention mechanisms to improve overall classification accuracy.

Moreover, promoting explainability and interpretability in deep learning models is vital. The development of interpretable models that provide insights into decision-making processes will enhance user trust in AI-driven predictions. Engaging stakeholders in the model development process ensures that the explanations align with user needs.

Additionally, investing in real-time monitoring systems by developing frameworks that leverage streaming data from satellites and IoT devices will enable timely updates on land use changes. Research should focus on algorithms capable of processing continuous data streams, facilitating immediate analysis and decision-making.

Finally, addressing ethical considerations is paramount. Establishing guidelines for responsible AI deployment in environmental monitoring will ensure that ethical implications are considered in the development and application of deep learning models.

The future of deep learning in LULC change detection is promising, with the potential to significantly enhance our understanding and management of land use dynamics. As remote sensing technology continues to advance, the integration of AI will become increasingly sophisticated, offering new opportunities for real-time monitoring and decision-making in land management. Future research will likely see a shift towards more collaborative efforts, combining expertise from remote sensing, machine learning, and domain-specific knowledge in environmental science and land management. The increasing availability of open-source datasets and advancements in cloud computing will facilitate broader access to deep learning technologies, democratizing their use in diverse applications.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Due to their proprietary nature, supporting data cannot be made openly available. Further information about the data and conditions for access are available upon request from the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Y. Deep learning for land use and land cover classification: A review. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, C. Remote sensing image classification using deep learning: A review. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhou, Y. Predicting land use change with deep learning: A case study of urban expansion. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, L. A deep learning approach for land cover change detection using multi-temporal remote sensing data. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2020, 164, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.; et al. Transfer learning for land use and land cover classification: A case study of urban areas. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; et al. Explainable deep learning for land use classification: A case study. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2021, 182, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; et al. Attention mechanisms in deep learning for land cover classification. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Hutter, F. Neural network architecture search with reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning; 2016; Vol. 48, pp. 2067–2075. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Using GANs for data augmentation in land use classification. Remote Sensing 2016, 12, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H. Multi-temporal remote sensing data for land cover change detection using deep learning. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2020, 184, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frid-Adar, M.; et al. GANs for data augmentation in land cover classification. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J. Long short-term memory networks for land cover change detection. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Q. Multi-modal deep learning for land cover classification using remote sensing data. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y. Explainable deep learning for land use classification: A case study. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2022, 182, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Using GANs for data augmentation in land use classification. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhou, Y. Predicting land use change with deep learning: A case study of urban expansion. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; et al. GAN-based data augmentation for land cover classification. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; et al. Explainable AI for remote sensing applications: A review. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H. Multi-temporal remote sensing data for land cover change detection using deep learning. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2021, 184, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Q. Spatial attention mechanism for land cover classification. Remote Sensing 2022, 12, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; et al. Transfer learning for land cover classification: A case study of urban areas. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kussul, N.; Shelestov, A.; Skakun, S. Deep learning for land cover classification: A case study of Ukraine. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H. Multi-temporal remote sensing data for land cover change detection using deep learning. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2022, 184, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Y. Exploring attention mechanisms for land use classification. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, B.; Kar, S.; Pati, S. A deep learning approach for land cover change detection using multi-temporal remote sensing data. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2020, 164, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liu, C.; Yang, X. Hyperspectral image classification based on deep learning: A review. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. Why should I trust you? Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Y. Exploring attention mechanisms for land use classification. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liu, C.; Yang, X. Hyperspectral image classification based on deep learning: A review. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]