1. Introduction

Developmental venous anomaly (DVA), also known as cerebral venous angioma is a congenital venous malformation of veins draining brain parenchyma [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Some clinicians refer to them as caput medusae [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. DVAs consist of radially arranged configuration of medullary veins that are distinct from the normal brain parenchyma, forming a pattern that resembles an "umbrella" [

2,

3,

4,

5]. DVAs are a subtype of cerebrovascular malformations (CVM) that account for up to approximately 55% of such lesions, and among general population CVMs occur in 2.6 to 6.4%, relatively widely depending on the demographics, study population, region, etc [

2,

3,

5,

6]. Mostly, these lesions are clinically insignificant, although, in the literature, they have been associated with migraine and other symptoms [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

Majority of DVAs are diagnosed incidentally, and, due to their benign clinical course, these lesions generally do not require intervention [

3,

5,

6,

7]. However in rare, extraordinary cases a DVA can be symptomatic, causing headaches, seizures, neurological deficits, even cerebral infarction and hydrocephalus[

3,

5,

6]. For instance, in 2019, Althobaiti E et. al. published a case report where DVA was mimicking a thrombosed cerebral vein; in this case, the patient was admitted to a primary health care service due to severe throbbing headache and high blood pressure [

8]. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) is considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of DVA’s; however, they can often be identified using contrast- enhanced cross- sectional imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) [

5].

Furthermore, basal ganglia calcification (BGC) is a neurodegenerative process that may occur primarily as a presentation of Fahr’s disease, secondary due to underlying cause (

Table 1) or related to aging [

9]. Similarly to DVAs, basal ganglia calcification is characterised by its indolent nature, therefore, the diagnostic process may be challenging. Brain NECT is considered a gold standard for diagnosis identifying calcifications as hyperdense lesions [

10]. Often these calcifications are observed in the basal ganglia; however, cases with calcifications occurring in subcortical structures such as dentate nuclei, thalamus and subcortical white matter have been previously described [

10]. Less frequently, calcifications can also be found in the internal capsule, cerebral and cerebellar cortex, and brainstem [

10].

BGC is relatively common, incidentally identified in about 0.3-20% of all brain NECT scans, depending on the study population, region demographics etc [

10,

12]. According to available scientific literature data, these calcifications are frequently observed in geriatric patients; in this case, these lesions are considered “physiological” [

10,

11,

12]. However, if these calcifications are demonstrated in patients younger than 50 years, these findings should be considered pathological [

12]. In contrast to bilateral BGC, available literature data on unilateral BGC, possible causative agents and pathophysiology is rather limited, therefore, future research on this topic is warranted.

To date, only a limited number of case reports have documented unilateral BGC associated with DVAs. Majority of authors claim that DVA’s contribute to the development of unilateral BGC due to the presumed venous hypertension in the territory drained by the vascular malformation. As a result, stenosis of the collector vein causes chronic increase in the venous pressure within the DVA, although venous hypertension can also occur even without frank stenosis of the collector veins [

2,

20,

21,

22]. Progressive thickening and hyalinization of the vessel walls in DVA’s leads to increased vascular resistance, reduced compliance, and venous hypertension. Chronic venous hypertension, in turn, results in chronic ischemia, oedema, microhaemorrhages, gliosis, dystrophic calcification, and atrophy [

2,

20,

21,

23]. This sustained venous hypertension may represent the underlying pathogenic mechanism responsible for the parenchymal changes in the surrounding tissues of DVAs, potentially contributing to unilateral basal ganglia calcification [

2,

20,

21,

22].

Based on the available publications and scientific literature, pathological unilateral basal ganglia calcification may arise from a few potential aetiologies. Comprehensive patient evaluation and tailored therapeutic interventions are crucial to achieving optimal recovery, favourable prognosis, and improved long-term outcome.

2. Case Presentation

A fifty-four-year-old Caucasian male was admitted to a tertiary university hospital due to a sudden speech impairment and right-sided weakness. His medical history included primary arterial hypertension (PAH), dislipidemia, lumbar and sacral spine spondylosis with myofascial pain syndrome. No prior ischemic events were documented. The patient’s sibling also had a history of PAH , and she had a history of an intracerebral haemorrhage at the age of 54. The neurological examination revealed mild central type paresis of the facial muscles on the right side, mild right-sided hemiparesis, and right side hemihypesthesia. Deep tendon reflexes were more pronounced on the left side compared to the right side in both upper and lower extremities. Patient was stable in the Romberg’s manoeuvre. The patient exhibited pronounced motor aphasia. The patient scored 10 at the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), indicating moderate stroke severity, while the Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of 4 points noted moderately severe disability.

The patient’s clinical presentation and risk factors were indicative of acute intracerebral ischemia. In alignment with the clinical scenario, a native NECT of the brain was performed, a critical in assessing eligibility for intravenous thrombolysis- a key intervention for acute ischemic stroke.

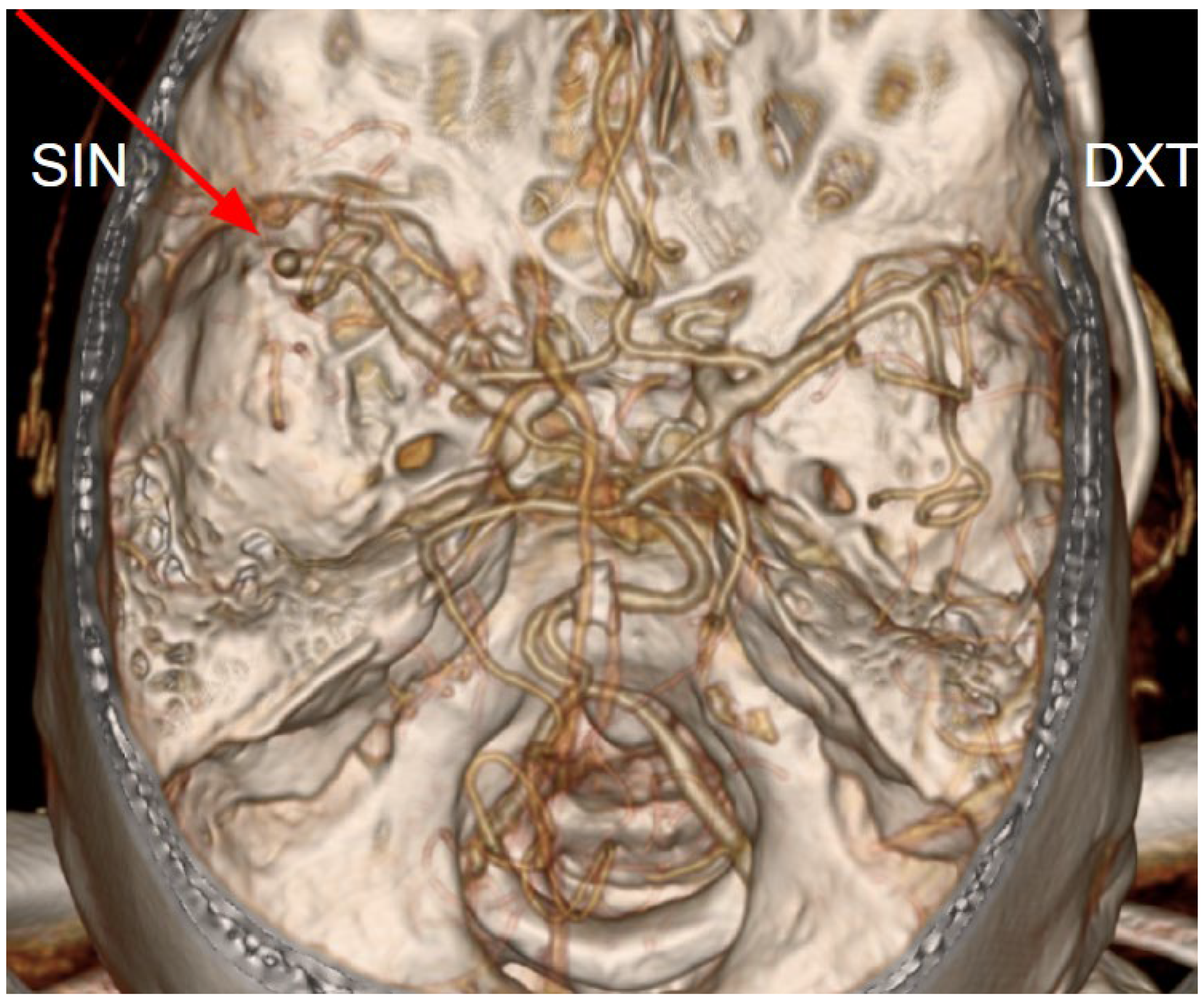

The initial NECT radiological findings did not provide a definitive diagnosis and did not show any signs of acute ischemia. Considering the patient’s clinical presentation and initial NECT findings, further investigation with CT angiography was conducted. An acute occlusion of the M2 segment of the left middle cerebral artery (MCA) was identified, accompanied by leptomeningeal collaterals extending to the left brain hemisphere with a Tan collateral score of 3 (

Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4). A subsequent perfusion CT was performed revealing an extensive hypoperfusion zone predominantly consistent with a penumbra-type lesion (

Figure 5). No hemorrhage was observed. The emergency department radiologist and neurologist raised concerns regarding the possibility of an acute ischemia combined with primary neoplastic tumour and calcification of the basal ganglia, potentially a high- grade oligodendroglioma. Therefore, an acute thrombolytic therapy with intravenous thrombolysis was contraindicated. Thrombolysis is typically constrained to a standardized 4.5-hour window to optimize reperfusion outcomes and minimize the risk of ischemia-reperfusion injury [

24,

25]. The patient was subsequently admitted to the Stroke Unit for further evaluation and management.

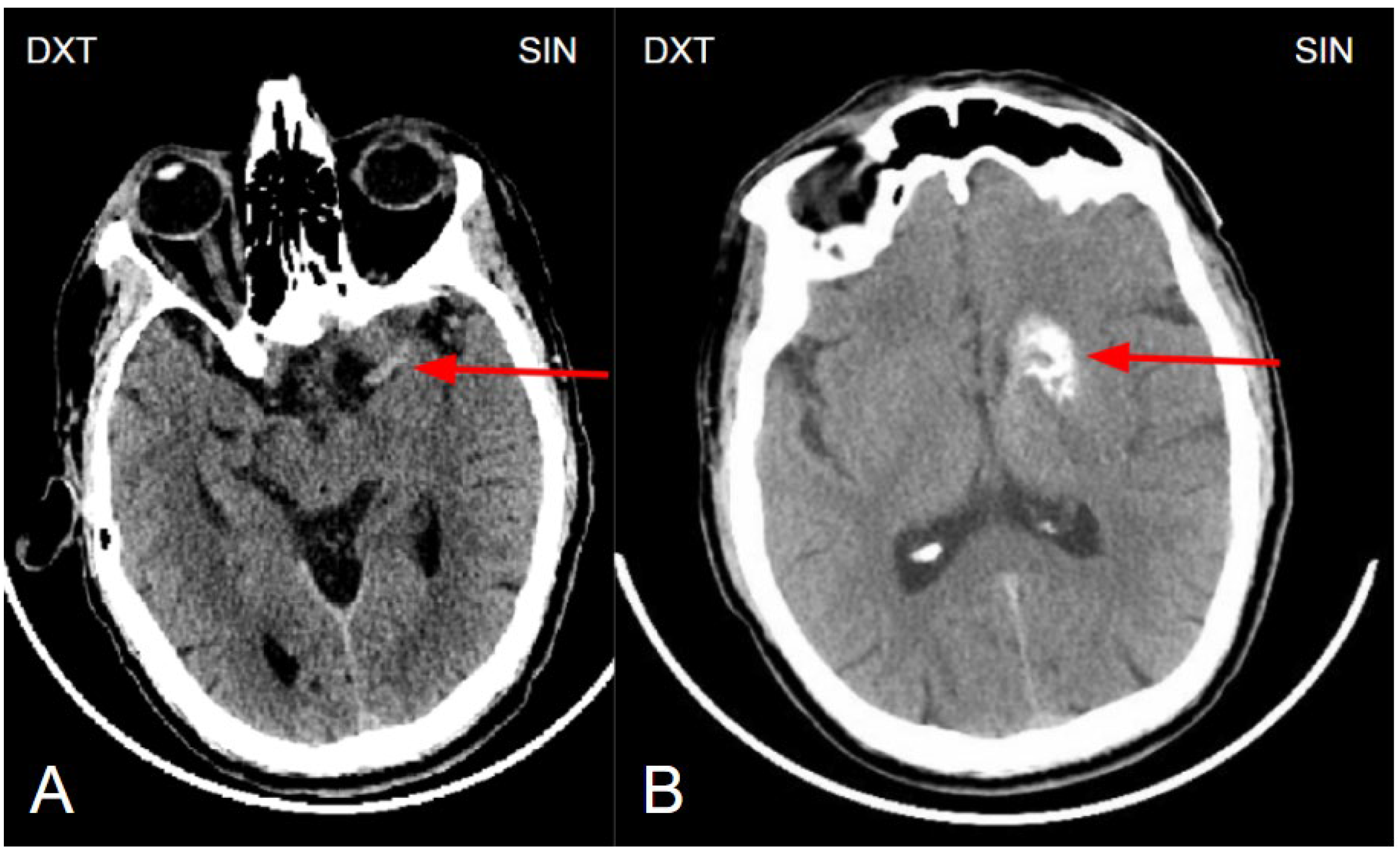

The next day, a neuroradiologist reviewed a control followup NECT, that demonstrated an ischemic lesion localized to the left insula, predominantly involving the left parietal lobe and the superior gyrus of the left temporal lobe (

Figure 1). Additional radiological findings included a hyperdense artery sign, characteristic of acute thrombosis, and basal ganglia calcification on the left side, warranting further investigation to clarify the underlying aetiology. Subsequently MRI of the brain was conducted, which also revealed ischemic signs, as well as unilateral basal ganglia calcification (

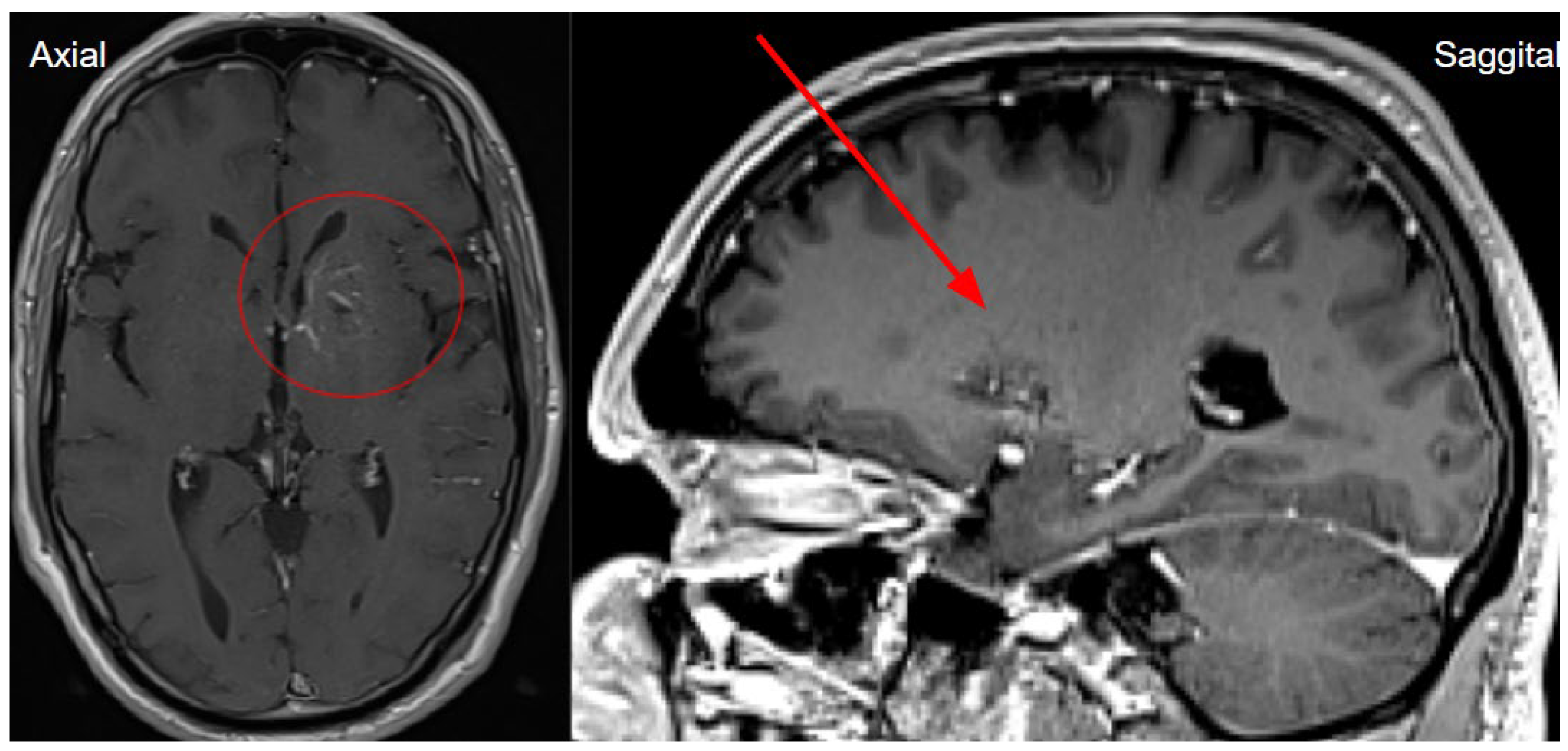

Figure 6). Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) was performed to clarify reasons for unilateral basal ganglia calcifications, and it confirmed the presence of a developmental venous anomaly (

Figure 7).

Conservative treatment was initiated, including antiplatelet therapy with aspirin, an angiotensin receptor blocker (valsartan), a thiazide diuretic (hydrochlorothiazide), and HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statin) rosuvastatin. To address post-infarction neurological complications, such as motor aphasia, right-sided hemihypesthesia, mild hemiparesis, facial muscle paralysis, and fine motor impairment, a multidisciplinary team with functional specialists enrolling speech therapist, physiotherapist and ergotherapist was engaged. The patient was closely monitored over the next few days. Neurological symptoms gradually improved, and the patient was discharged from the hospital in a good overall health condition five days after symptom onset with further recommendations to continue the prescribed pharmacological therapy and physiotherapy at home.

Figure 1.

(A) Non enhanced computed tomography of the brain showing a hyperdense artery sign, arteria cerebri media sin. M1 segment (red arrow). The hyperdense artery sign typically indicates acute thrombosis, especially in the presence of corresponding neurological symptoms. (B) Non-enhanced computed tomography of the brain at the basal ganglia level shows unilateral basal ganglia calcinosis, predominantly in the caput nuclei caudati and nucleus lentiforme (red arrow), without perifocal edema or mass effect, suggesting changes of a more likely benign nature.

Figure 1.

(A) Non enhanced computed tomography of the brain showing a hyperdense artery sign, arteria cerebri media sin. M1 segment (red arrow). The hyperdense artery sign typically indicates acute thrombosis, especially in the presence of corresponding neurological symptoms. (B) Non-enhanced computed tomography of the brain at the basal ganglia level shows unilateral basal ganglia calcinosis, predominantly in the caput nuclei caudati and nucleus lentiforme (red arrow), without perifocal edema or mass effect, suggesting changes of a more likely benign nature.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography angiography of the magistral intracranial arteries (volume-rendered reconstruction) shows an occlusion of the left middle cerebral artery (M2 segment) (red arrow).

Figure 2.

Computed tomography angiography of the magistral intracranial arteries (volume-rendered reconstruction) shows an occlusion of the left middle cerebral artery (M2 segment) (red arrow).

Figure 3.

Computed tomography post contrast on left basal ganglia level in axial and sagittal planes showing a low contrast enhancement vessel- venous angioma, which corresponds to developmental venous anomaly (DVA), which we think is the causative agent for basal ganglia calcinosis (red circle and red arrow).

Figure 3.

Computed tomography post contrast on left basal ganglia level in axial and sagittal planes showing a low contrast enhancement vessel- venous angioma, which corresponds to developmental venous anomaly (DVA), which we think is the causative agent for basal ganglia calcinosis (red circle and red arrow).

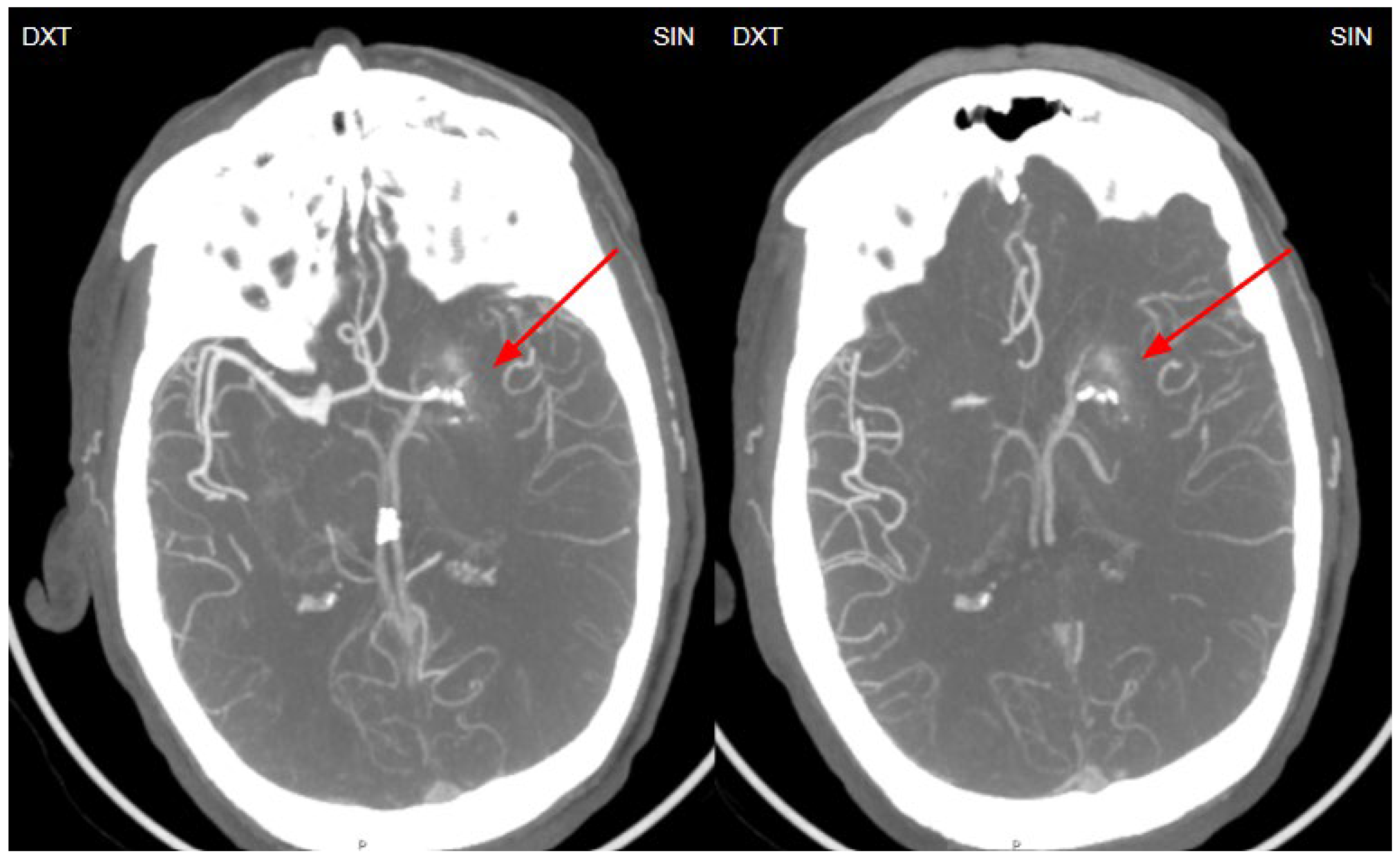

Figure 4.

Retrospective analysis of the computed tomography angiography (MIP-CTA) images, performed before the MRI and DSA examinations, reveals a small venous angioma (DVA) in the left basal ganglia (red arrows).

Figure 4.

Retrospective analysis of the computed tomography angiography (MIP-CTA) images, performed before the MRI and DSA examinations, reveals a small venous angioma (DVA) in the left basal ganglia (red arrows).

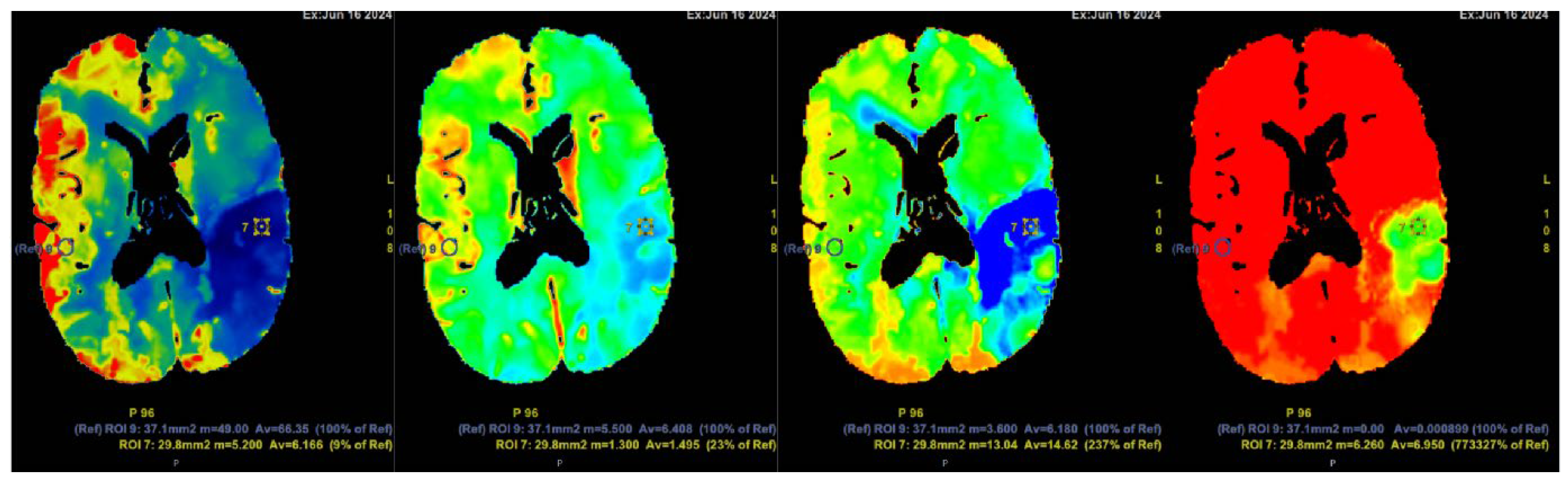

Figure 5.

Computed tomography perfusion (CTP) after contrast injection shows a large hypoperfusion area in the territory of the left middle cerebral artery (ACM sin) with extensive penumbra-type damage (salvageable brain tissue) and a small core-type lesion in the parietal lobe, comprising less than one-third of the total hypoperfusion volume. The findings suggest the patient could potentially benefit from intravenous thrombolysis. Cerebral blood flow (CBF) 9%; cerebral blood volume (CBV) 23%; mean transit time (MTT) 237%.

Figure 5.

Computed tomography perfusion (CTP) after contrast injection shows a large hypoperfusion area in the territory of the left middle cerebral artery (ACM sin) with extensive penumbra-type damage (salvageable brain tissue) and a small core-type lesion in the parietal lobe, comprising less than one-third of the total hypoperfusion volume. The findings suggest the patient could potentially benefit from intravenous thrombolysis. Cerebral blood flow (CBF) 9%; cerebral blood volume (CBV) 23%; mean transit time (MTT) 237%.

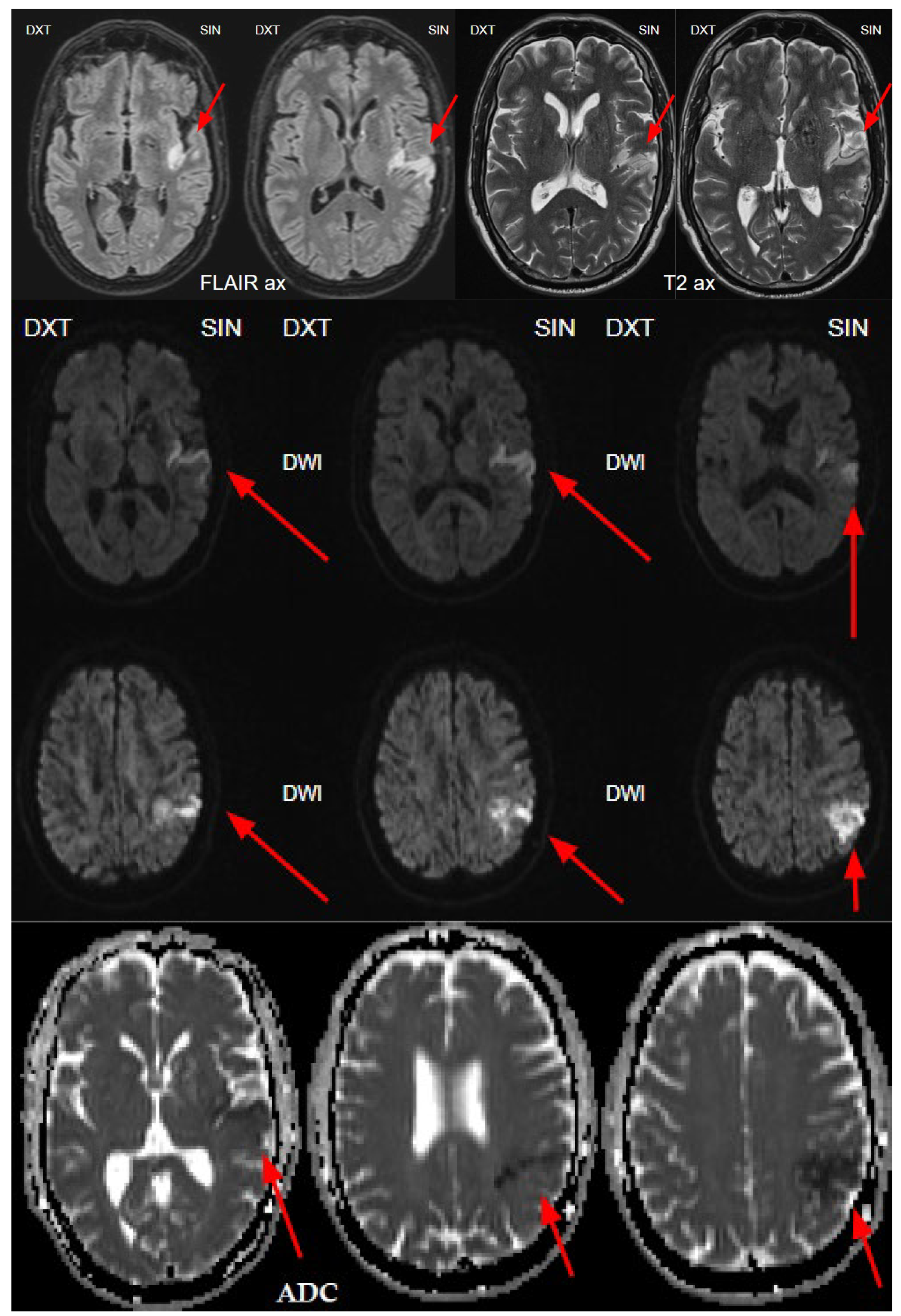

Figure 6.

The next day's magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and T2-weighted sequences reveals acute ischemia in the left insula and left parietal lobe, and upper gyrus of temporal lobe corresponding to the lesion seen on CTP and consistent with the territory of the left middle cerebral artery (MCA), M2 segment. Diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) sequence showing restricted diffusion on left side insula, left parietal and temporal lobe with low apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map value, which corresponds to acute infarction of the middle cerebral artery territory of the left side M2 occlusion.

Figure 6.

The next day's magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and T2-weighted sequences reveals acute ischemia in the left insula and left parietal lobe, and upper gyrus of temporal lobe corresponding to the lesion seen on CTP and consistent with the territory of the left middle cerebral artery (MCA), M2 segment. Diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) sequence showing restricted diffusion on left side insula, left parietal and temporal lobe with low apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map value, which corresponds to acute infarction of the middle cerebral artery territory of the left side M2 occlusion.

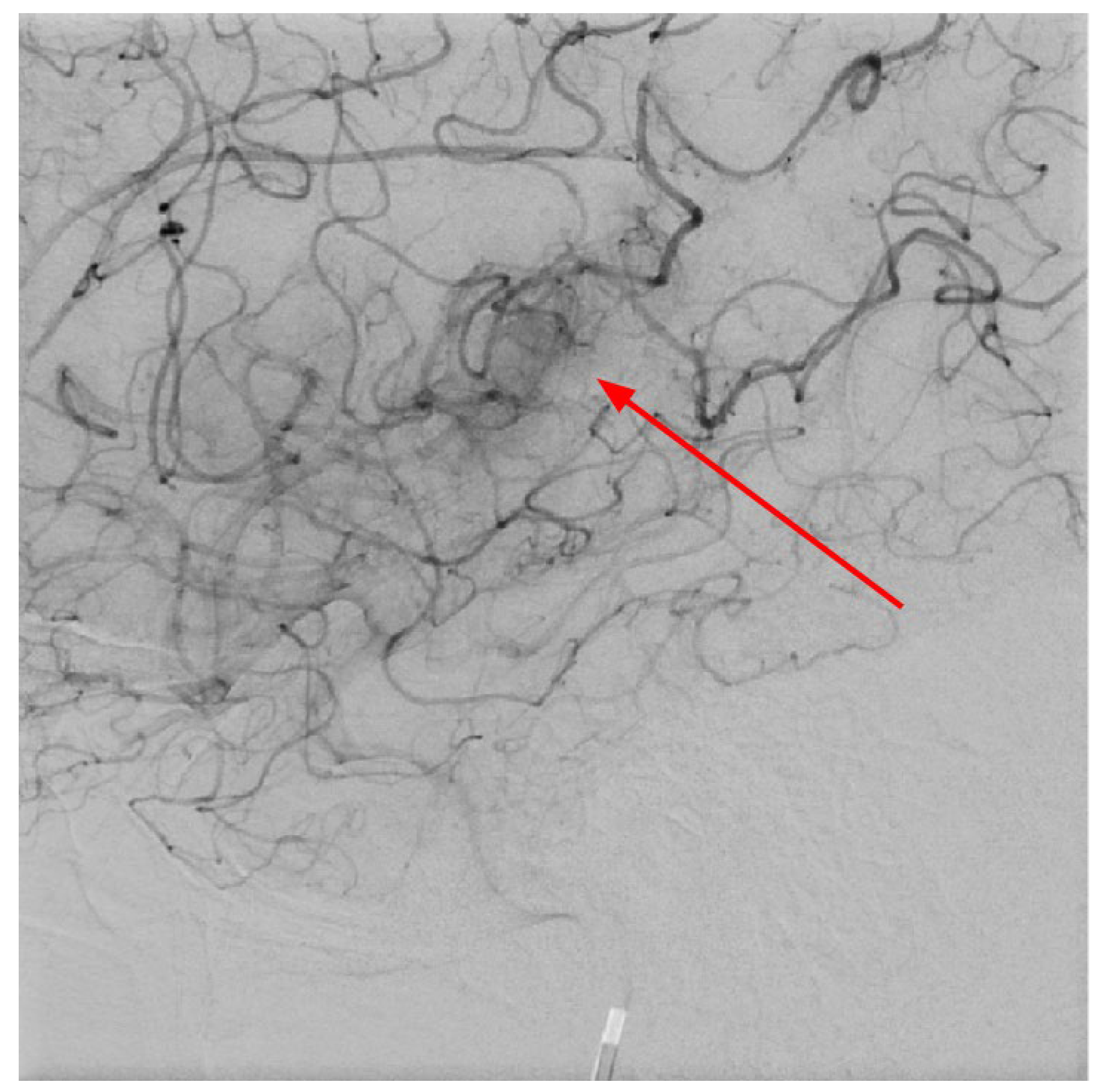

Figure 7.

Digital subtraction angiography in LL projection at the level of basal ganglia showing abnormal vessels, which corresponds to developmental venous anomaly- venous angioma in the left area of the basal ganglia, also these changes seen on CTA and MRI after contrast injection (red arrow).

Figure 7.

Digital subtraction angiography in LL projection at the level of basal ganglia showing abnormal vessels, which corresponds to developmental venous anomaly- venous angioma in the left area of the basal ganglia, also these changes seen on CTA and MRI after contrast injection (red arrow).

3. Discussion

Developmental venous anomalies (DVA) and basal ganglia calcifications have been previously described in the literature. DVAs are composed of dilated medullary veins draining normal brain parenchyma ultimately draining into the deep or the superficial venous system [

26]. DVAs are thought to arise from a maldevelopment of foetal cortical venous drainage, but the clear aetiology of DVAs is still under debate [

23]. Usually, DVAs are benign and incidentally discovered by either angiographic or contrast-enhanced brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), usually resembling “caput medusae” [

1,

2,

7,

23]. However, publicly available case reports about unilateral basal ganglia calcinosis due to venous angioma are under 20.

In 2010, Dehkharghani et al. published an article demonstrating six case reports with unilateral caudate and putamen calcifications in DVA drainage territories. In all these patients, DVA was found in gadolinium-enhanced MRI and/or computed tomography angiography (CTA) or conventional angiography. They stressed out the venous hypertension as the main contributing factor for these abnormalities [

22]. Moreover, they reported no symptoms referable to the basal ganglia, and patients they presented did not reveal underlying metabolic disorders or processes associated with calcium deposition [

22]. In our case, the patient was a fifty-four-year-old male presenting with a sudden speech impairment and right-sided weakness. No abnormal movements were noted in this patient. Subacute stroke on the left side in the dorsal part of the insula, in the upper dorsal part of the left temporal lobe and partially in the left parietal lobe was found on NECT, and CTA revealed left middle cerebral artery (MCA) M2 occlusion. On CT perfusion (CTP), markedly decreased cerebral blood flow (CBF) and cerebral blood volume (CBV) was noted along with increased mean transit time (MTT). Subsequently, gadolinium-enhanced brain MRI was performed where small blood vessels draining to subependymal periventricular veins on T1 post-contrast was found. Due to these findings, the patient underwent following digital subtraction angiography (DSA) where venous angioma in the area of the left basal ganglia was observed.

Another possible cause of unilateral BGC could be oligodendrogliomas (OG). OGs are rare neuroepithelial tumours of the central nervous system, a type of gliomas, accounting up to 5% of primary intracranial neoplasms [

19]. These tumours are predominantly found in the frontal lobes of the brain, often involving cortical or subcortical regions [

17,

19]. Most OGs contain coarse calcification, observed in 30% to 90% of cases [

17,

18,

19]. The presence of calcification is characterized by the high signal intensity in T2- weighted MRI sequences [

17,

18,

19]. In radiological imaging, these calcifications could potentially present unilaterally, depending on the OG’s localization [

17,

18,

19].

Unilateral BGC may also be associated with non-ketotic hyperglycaemia (NKH), which is a component of the non-ketotic hyperglycaemic hemichorea syndrome, also known as diabetic striatopathy or chorea-hyperglycemia-basal ganglia (C-H-BG) syndrome. This syndrome is often described to have a typical triad that enrolls unilateral involuntary movements, contralateral striatal abnormality on neuroimaging and resolution of symptoms after correction of hyperglycemia [

15,

16]. Brain NECT and MRI may demonstrate unilateral hyperintensity in the striatal region, most commonly the putamen, which can manifest contralaterally in the body as hemiballism or hemichoreic movements [

15,

16].

Sometimes, AVMs may occur in patients with genetic conditions [

27]. Just recently, in October 2024, Toader et al. published a case report of a 36-year-old female with prothrombin G20210A mutation-associated thrombophilia, highlighting its potential impact on AVM pathophysiology and management [

27]. In this case, the patient underwent frontal craniotomy with microsurgical resection of the AVM which proved to be a viable and effective treatment option [

27].

In 2022, Patel et al. presented a clinical case report about a patient with hyperkinetic choreiform movements attributed to basal ganglia calcification and underlying developmental venous anomaly [

28]. Movement disorders are often associated in the setting of a recent stroke, but chorea-like hyperkinetic movements in association with DVAs have not been thoroughly reported so far [

28,

29]. Their imaging results revealed right-sided unilateral calcifications within the basal ganglia with associated DVA in the absence of stroke, contributing to contralateral hyperkinetic movements [

28]. Another publication about unilateral hyperkinetic choreiform movements due to basal ganglia calcification and underlying DVA was published in 2019 by Falconer et al [

20]. They pointed out clonazepam as one of the treatment options for such cases [

20]. Patel et al. revealed a trial with clonazepam in their patient resulting in almost near-resolution of hyperkinetic movements [

28].

In our patient, no abnormal movements were noted. During his hospitalisation, the patient underwent a wide range of tests and exams, revealing no data of systemic or genetic disorders. The patient received conservative treatment. However, mild motor aphasia, slight coordination impairment in the right upper extremity and sensory ataxia in both lower extremities persisted along with deep tendon reflex asymmetry in both arms and in both legs, dx>sin. After 5 days, the patient was discharged from the hospital in a good overall-health condition with further recommendations to continue antiplatelet therapy with aspirin indefinitely, antihypertensive therapy and rosuvastatin.

This clinical case report demonstrates a highly valuable and educative radiologic findings about unilateral BGC and developmental venous anomaly, considering there are less than 20 case reports available so far. We believe that this report will be interesting for medical professionals and will provide an additional contribution to the science of this pathology, however there is still a need for more research and awareness of this pathology to increase the knowledge about such cases and improve patient management.

4. Conclusions

To conclude, unilateral basal ganglia calcinosis due to venous angioma is a rare condition characterized by unclear pathophysiological mechanisms, a limited number of potential aetiologies, and a heterogeneous clinical presentation. It can mimic other conditions, such as intracerebral hemorrhage or hemorrhagic brain tumors, thereby complicating acute stroke management, as illustrated in this case. Comprehensive interdisciplinary patient evaluation and therapeutic interventions are crucial to achieving optimal recovery and improved long-term outcome.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B., S.S., O.Z., K.V., and J.V.; methodology, A.B., S.S., O.Z., S.P., E.N., and K.K.; software, A.B., S.P., E.N., K.K..; validation, S.S., A.B., and K.K.; formal analysis, S.S., A.B..; investigation, O.Z., K.V., S.S., A.B..; resources, O.Z., K.V.; data curation, A.B., J.V., S.P., E.N., K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, O.Z., S.S., K.V..; writing—review and editing, S.S., A.B., S.P.; visualization, A.B., S.P., E.N.; supervision, A.B., K.K.; project administration, A.B.; funding acquisition, A.B.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was covered by Riga Stradins University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Riga Stradins University, Riga, Latvia.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Pauls Stradins Clinical University Hospital, Institute of Diagnostic Radiology, our colleagues in radiology and neurology, as well as to Pauls Stradins Clinical University Hospital, Department of Neurology, and to Riga Stradins University, Faculty of Residency staff for our work together.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Santucci, G.M. , et al. , Brain parenchymal signal abnormalities associated with developmental venous anomalies: detailed MR imaging assessment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2008, 29, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sarp, A.F., O. Batki, and M. F. Gelal, Developmental Venous Anomaly With Asymmetrical Basal Ganglia Calcification: Two Case Reports and Review of the Literature. I J Radiol, 2015, 12, e16753. [Google Scholar]

- Essentials of Osborn’s Brain: A Fundamental Guide for Residents and Fellows Anne G. Osborn, MD, FACR University Distinguished Professor and Professor of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, William H. and Patricia W. Child Presidential Endowed Chair in Radiology, University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, Utah.

- Rammos, S.K., R. Maina, and G. Lanzino, Developmental venous anomalies: current concepts and implications for management. Neurosurgery, 2009, 65, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Idiculla, P.S. , et al. , Cerebral Cavernous Malformations, Developmental Venous Anomaly, and Its Coexistence: A Review. Eur Neurol, 2020, 83, 360–368. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.C.-T. and T. Krings, Symptomatic Developmental Venous Anomaly: State-of-the-Art Review on Genetics, Pathophysiology, and Imaging Approach to Diagnosis. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 2023.

- Aoki, R. and K. Srivatanakul, Developmental Venous Anomaly: Benign or Not Benign. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo), 2016, 56, 534–543. [Google Scholar]

- Althobaiti, E. , Felemban, B. , Abouissa, A., Azmat, Z., & Bedair, M. (2019). Developmental venous anomaly (DVA) mimicking thrombosed cerebral vein. Radiology Case Reports, 14(6), 778–781.

- Li, M. , et al. , SLC20A2-Associated Idiopathic basal ganglia calcification (Fahr disease): a case family report. BMC Neurol, 2022, 22, 438. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.Y. , et al., The Genetics of Primary Familial Brain Calcification: A Literature Review. Int J Mol Sci, 2023, 24.

- de Brouwer, E.J. , et al. , Basal ganglia calcifications: No association with cognitive function. J Neuroradiol, 2023, 50, 266–270. [Google Scholar]

- Donzuso, G. , et al. , Basal ganglia calcifications (Fahr's syndrome): related conditions and clinical features. Neurol Sci, 2019, 40, 2251–2263. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, Y.-C. and M. -I. Lin, Intramuscular Hemangioma of the Temporalis Muscle With Incidental Finding of Bilateral Symmetric Calcification of the Basal Ganglia: A Case Report. Pediatrics and neonatology, 2010, 51, 296–9. [Google Scholar]

- Amisha, F. and S. Munakomi, Fahr Syndrome, in StatPearls. 2024, StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL).

- Johari, B. , et al., Unilateral striatal CT and MRI changes secondary to non-ketotic hyperglycaemia. BMJ Case Reports, 2014, 2014.

- Evers Smith, C.M., K. K. Chaurasia, and D.C. Dekoski, Non-ketotic Hyperglycemic Hemichorea-Hemiballismus: A Case of a Male With Diabetes Mellitus and Speech Disturbances. Cureus, 2022, 14, E25073. [Google Scholar]

- Mubarak, F. , et al. , Multifocal oligodendroglioma with callosal and brainstem involvement. Surg Neurol Int, 2022, 13, 442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Differential Diagnosis of Intracranial Masses, in Diseases of the Brain, Head and Neck, Spine 2020–2023: Diagnostic Imaging, J. Hodler, R.A. Kubik-Huch, and G.K. von Schulthess, Editors. 2020, Springer Copyright 2020, The Author(s). Cham (CH). p. 93-104.

- Tork, C.A. and C. Atkinson, Oligodendroglioma, in StatPearls. 2024, StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL).

- Falconer, R.A. , et al. , Unilateral Hyperkinetic Choreiform Movements due to Calcification of the Putamen and Caudate from an Underlying Developmental Venous Anomaly. Cureus, 2019, 11, e3990. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- San Millán Ruíz, D. , et al. , Parenchymal abnormalities associated with developmental venous anomalies. Neuroradiology, 2007, 49, 987–995. [Google Scholar]

- Dehkharghani, S. , et al. , Unilateral calcification of the caudate and putamen: association with underlying developmental venous anomaly. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2010, 31, 1848–1852. [Google Scholar]

- Wilms, G. , et al. , Cerebral venous angiomas. Neuroradiology, 1990, 32, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ringleb, P. , et al. , Extending the time window for intravenous thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke using magnetic resonance imaging-based patient selection. Int J Stroke, 2019, 14, 483–490. [Google Scholar]

- L, L., W. X, and Y. Z, Ischemia-reperfusion Injury in the Brain: Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutic Strategies. Biochem Pharmacol (Los Angel), 2016, 5.

- Lasjaunias, P., P. Burrows, and C. Planet, Developmental venous anomalies (DVA): the so-called venous angioma. Neurosurg Rev, 1986, 9, 233–242. [Google Scholar]

- Toader, C. , et al. , The Microsurgical Resection of an Arteriovenous Malformation in a Patient with Thrombophilia: A Case Report and Literature Review. Diagnostics, 2024, 14, 2613. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, J., M. Khalil, and S. Zafar, Hyperkinetic Choreiform Movements Secondary to Basal Ganglia Calcification and Underlying Developmental Venous Anomaly. Cureus, 2022, 14, e22752. [Google Scholar]

- Bhidayasiri, R. and D. D. Truong, Chorea and related disorders. Postgrad Med J, 2004, 80, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).