1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a significant respiratory virus responsible for claiming over 6 million lives worldwide, inciting a global pandemic most known as COVID-19 [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. It is believed that SARS-CoV-2 was first detected in Wuhan, China, in late 2019 and then kept evolving to different variants. SARS-CoV-2 falls within the coronavirus family of zoonotic viruses, which also includes the Middle Eastern Respiratory Virus (MERS-CoV), SARS-CoV and other seasonal human CoVs [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. The high transmissibility and infection rates of SARS-CoV-2 set it apart from other coronavirus variants. While SARS-CoV is similarly an airborne virus, SARS-CoV-2 can be contracted and spread before the onset of symptoms and is spread just as frequently by asymptomatic individuals [

12]. This challenges public health efforts as it is harder to control the influx of symptoms when patients have different timelines regarding presymptomatic or asymptomatic infection. SARS-CoV-2 infection has varying adverse effects on infected individuals ranging from mild to severe/critical. According to the World Health organization (WHO), symptomatic patients typically experience common symptoms of fever, cough, fatigue, and loss of taste or smell, along with less common symptoms such as skin irritation, bodily aches, sore throat, headache, diarrhea, and eye irritation [

13]. Moreover, more severe illness is associated with serious breathing/lung impairment that requires immediate attention. Some of the worst cases will experience life-threatening conditions like acute respiratory distress syndrome that requires intensive care. However, some individuals experience prolonged and severe symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection, known as long COVID. This multisystemic condition has affected over 65 million people globally, increasing the risk for conditions such as type 2 diabetes, chronic fatigue, and cardiovascular disease.

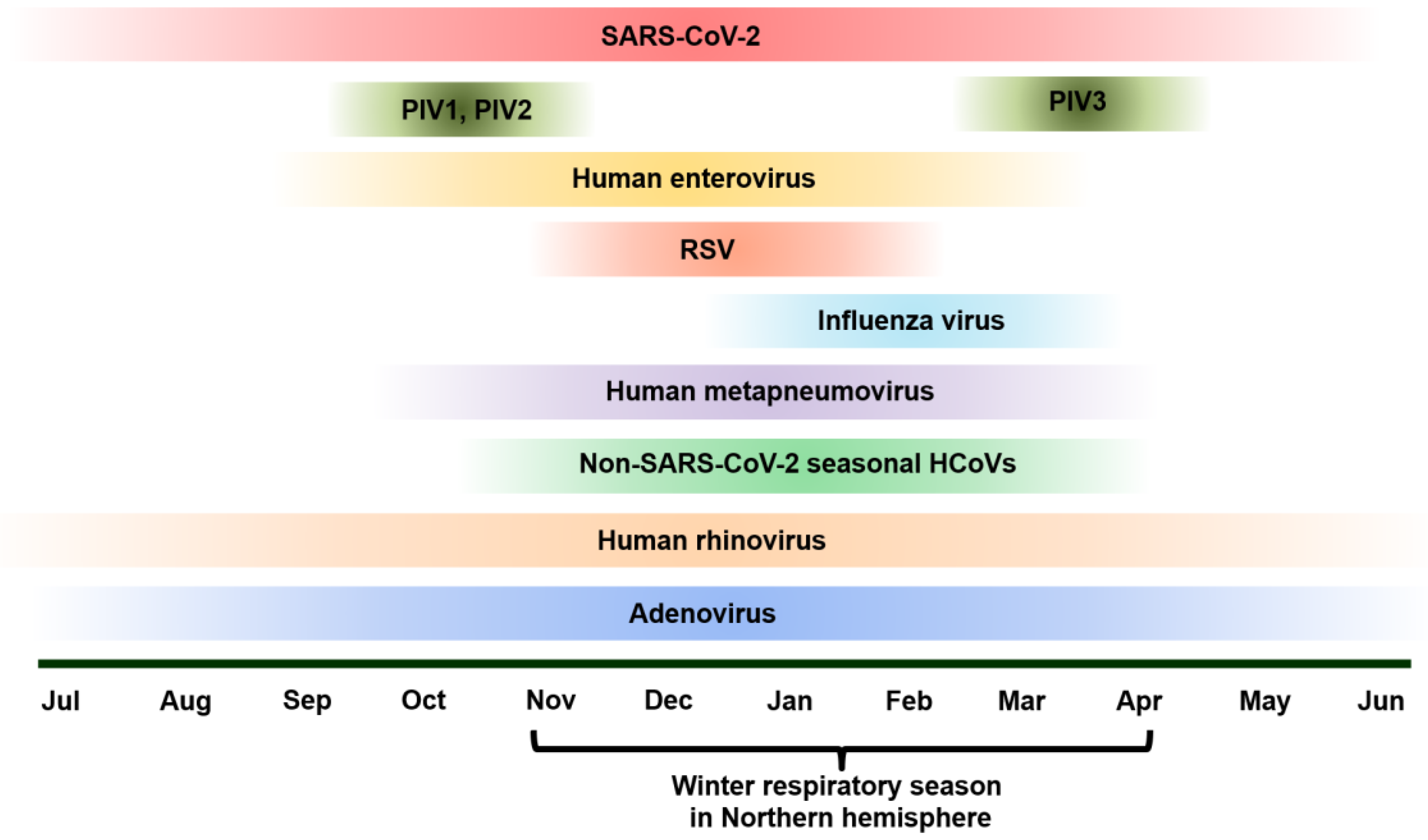

As SARS-CoV-2 spread rapidly worldwide since late 2019, the rate of infection of many respiratory pathogens had started to decline as most individuals had followed major guidelines to slow the spread of the virus [

12]. Since 2021, there have been changes in the epidemiology and the seasonality of pathogens such as Influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human metapneumovirus (hMPV), enterovirus, rhinovirus, parainfluenza virus (PIV), and adenovirus [

14,

15,

16]. In addition, with SARS-CoV-2 and respiratory viruses circulating simultaneously, co-infections between SARS-CoV-2 and respiratory viruses have become prevalent and have influenced patient outcomes [

13,

17] (

Figure 1).

For example, before the pandemic, seasonal Influenza typically peaked in the Northern hemisphere in late winter, e.g., the first half of February, while the Southern hemisphere saw peaks in late July. During the COVID-19 pandemic, seasonal influenza A and B are still prevalent in many areas, causing unfavorable symptoms and complications even with readily available vaccines. Post pandemic peak in the Northern Hemisphere was as early as December, with the duration of epidemic increasing to 11 weeks. Although post pandemic peaks in the Southern hemisphere the post pandemic pak change was not statistically significant, the influenza epidemics increased in length at 20 weeks [

18]. As both influenza A/B and SARS-CoV-2 have similar transmission patterns (contact with aerosolized droplets and contaminated surfaces) symptoms and typically circulate in seasonal outbreaks, it poses a significant public health threat for co-infection [

19].

Another appealing example is RSV, which is the leading cause of lower respiratory tract infections in young children, most prevalent in children under two years of age [

20]. RSV is the second leading cause of infant deaths, making it a significant public health concern. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, in the Northern hemisphere RSV typically peaked in the winter season, around January, while in the southern hemisphere the virus peaked in late July. Post COVID pandemic, this pattern of RSV showed 1-2 months early, and there was a larger gap with the Southern hemisphere experiencing an earlier than usual peak during the first wave [

18,

21]. With the known contribution of RSV to increased respiratory distress and bronchiolitis in young children, the addition of SARS-CoV-2 infection can even further exacerbate the severity of RSV symptoms [

22].

With SARS-CoV-2 evolving into mild Omicron variants and co-circulating with other respiratory viruses, there is major knowledge gap in the impact of SARS-CoV-2 on the epidemiology and seasonality of othe traditional respiratory virues. Further, the change in the virus circulation requires an updated strategies in timely detecting SARS-CoV-2 and other traditional respiratory viruses, e.g., influenza viruses, RSV, enteroviruses, human rhinoviruses, adenoviruses, PIVs and seasonal HCoVs. There is urgent need to implement multiplex molecular tesings for SARS-CoV-2 and other traditional respiratory viruses, especially the point-of-care (POC) testings. In this review, we assess the epidemiology and impact of SAR-CoV-2 co-infections on other respiratory viruses. Further, we review multiplex molecular testing for the detection of respiratory viruses and co-infections with SARS-CoV-2. This review not only sheds light on the updated epidemiology of respiratory viruses in the post-COVID era but also provides insight on the appropriate application of multiplex molecular testing to detection of respiratory viruses, especially POC testing.

2. Co-Infection of SARS-CoV-2 with Viral Respiratory Infections

Co-infections occur when a host body is invaded by multiple pathogens simultaneously. As expected, this can complicate the symptoms and diagnoses of diseases. When co-infection is seen with respiratory viruses, it is significant because a combination of symptoms may occur from multiple viruses, creating a destructive recipe for the body’s immune system that may lead to prolonged illness and severe outcomes. With the rise of the COVID-19 pandemic at the onset of 2020, SARS-CoV-2 co-infections with other viral and bacterial pathogens have sparked concern for the potential of exacerbating the already severe symptoms and outcomes that are associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection [

23]. Evidence from studies has shown that these co-infections have frequent occurrence, making up around 0.35% observed infections in individuals displaying both severe and mild symptoms [

24]. While co-infection severity and frequency are continually being researched, there is evidence and understanding of how SARS-CoV-2 impacts various respiratory viruses as well as their diagnosis.

2.1. Influenza Viruses

Recent studies have shown that co-infection between SARS-CoV-2 and influenza strains has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality rates compared to individuals with single infections. Influenza’s effect on SARS-CoV-2 hinders immune responses and reduces antibody levels. Strikingly, patients who are co-infected have a mortality risk almost twice as high as those only infected with SARS-CoV-2 [

19,

25]. Vaccination for both SARS-CoV-2 and influenza provides an effective way for individuals to protect themselves against viruses and potential co-infection. Some studies have shown that influenza vaccines can cross-protect against SARS-CoV-2 and potentially mitigate the risk of severe risks such as mortality and severe symptoms [

25]. This probably can be explained by the concept of trained immunity in which an irrelevant vaccine may trigger innate immune memory that can prevent infection due to another irrelevant pathogen [

26].

For identification of co-infection between SARS-CoV-2 variants and influenza virues, RT-PCR assay and whole genome sequencing were used, which allowed variants like Delta and Omicron to be differentiated, which is crucial for understanding individual strain epidemiology [

27]. After performing these tests, statistical analyses were performed using logical regression to understand the associations between the SARS-CoV-2 variants and co-infections with Influenza A. Using this model, the researchers were able to evaluate the impact of the co-infections on patient outcomes such as symptoms while taking patient demographic and medical history into account. This aided in understanding how co-infections with different strains may influence clinical outcomes. The study found a 33% co-infection rate among SARS-CoV-2 positive patients, with higher rates in the Delta variant. In-depth diagnostic testing is crucial to understanding viral co-infections. RT-PCR has been proven to be more effective than rapid antigen-based assays, though the latter ones are often more readily available [

27].

2.2. RSV

While RSV is typically seasonal, with epidemics usually occurring in the winter months (

Figure 1), there is plenty of opportunity for SARS-CoV-2 co-infection and co-circulation to transpire, as the two are similar in their transmission method (aerosolized droplets). Accordingly, as both can be prevented by wearing masks, isolating from infected individuals, and disinfecting communal surfaces, there was a drop in reported RSV cases in the winter of 2021-22, when the COVID-19 pandemic was still in full effect. However, once pandemic restrictions were lifted, RSV cases spiked, even in some cases higher than the pre-pandemic level [

22]. This increased prevalence of RSV has increased the likelihood of SARS-CoV-2 and RSV co-infection, particularly in children, as they are most susceptible to respiratory viruses in general [

28]. Children have also been found to be more susceptible to respiratory viral co-infections than adults overall [

29]. While recent studies have shown that co-infection rates between RSV and SARS-CoV-2 are relatively sparse at 3%, their mere occurrence provides a significant understanding of how these viruses interact and their impact on patient outcomes [

29].

As with many respiratory viruses, SARS-CoV-2 and RSV have similar symptoms, complicating the diagnostic process. Multiplex PCR tests are the most common laboratory tests used to determine the presence of multiple pathogens in a sample. Once the predominant viral pathogen is determined, that is the one that is typically treated most closely while also focusing on treating the other, with RSV treatment being more focused on respiratory support. However, cases are mostly treated on an individualized basis as increased severity may be seen in infected individuals who may need more intensive treatment, which is why understanding and detecting co-infections is essential [

22].

2.3. hMPV

There is little significant understanding of the effect of hMPV on SARS-CoV-2 co-infection. Through chest computed tomography (CT) scan and RT-PCR, a study in Iran in 2020 found three cases of SARS-CoV-2 and hMPV co-infection in young children (a 13-month-old and two six-year-olds). All three children expressed similar symptoms of fever, cough, and malaise, will all three passing away within 2 days of being hospitalized for their infections. The researchers speculated that hMPV’s direct effect on inflammation, interferon secretion patterns in the respiratory tract, and causation of asthma may lead to increased SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility. This study emphasized the importance of testing for respiratory viral co-infections in young children, as they can potentially be fatal [

30]. Further, another study in 2020 detailed the case of a 57-year-old woman with pre-existing health conditions who tested positive for both hMPV and SARS-CoV-2 simultaneously (tested via respiratory pathogen panel (RPP) and RT-PCR). The patient expressed symptoms of dry cough and upper respiratory symptoms. SARS-CoV-2 and hMPV co-infections are infrequent in adults, and those with underlying or pre-existing health conditions may be at increased risk [

31]. The knowledge out there indicates that these co-infections are typically uncommon, and the outcomes are not significantly different from singular SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, in young children and those with pre-existing health conditions, these co-infections may have more severe clinical outcomes and implications [

30,

31,

32].

2.4. Enterovirus

Belonging to the family

Picornaviridae, the genus

enterovirus consists of enteroviruses, rhinoviruses, polioviruses, which can be further divided into hundreds of subtypes [

33,

34,

35]. Enteroviruses can cause a wide range of respiratory and neurological issues, sores and rashes on the hands, mouth, and, in severe cases, encephalitis and acute flaccid paralysis [

36]. When co-infected with SARS-CoV-2, enteroviruses can potentially produce severe clinical outcomes, as with most respiratory co-infections there are higher potential risks of hospitalization and need for inclusive diagnostic testing [

37]. While many of the documented co-infections with SARS-CoV-2 and enterovirus are with rhinoviruses, there have been some studies that have documented non-rhinovirus enteroviruses. One study from Jordan focusing on upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) found three cases of co-infections of SARS-CoV-2 and enterovirus co-infections and highlighted enteroviruses as the most common pathogen of viral co-infection [

38]. This research highlighted that generally enteroviruses have a high tendency to co-infect with other viruses including SARS-CoV-2, emphasizing the consistent need for multiplex testing methods to account for this possibility.

One review highlighted 130 studies where bacterial, fungal, and respiratory co-infections with SARS-CoV-2 were discovered in pediatric cases. Across the 130 studies predominantly using RT-PCR, only 5 cases of enterovirus co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 were found [

39]. This may indicate that these co-infections are not as prevalent as others. However, one study found that culturing SARS-CoV-2, coxsackievirus A7 (CVA7), and enterovirus A71 (EV-A71) in Vero E6 and HEK293A cell produced an inhibitory effect on the SARS-CoV-2 virus. In addition, they found that hamsters co-infected with SARS-CoV-2 and enteroviruses exhibited non severe clinical symptoms, even presenting with less reduction in body weight and lower levels of SARS-CoV-2 in the lungs than those singularly infected with SARS-CoV-2 [

40]. This study provides significant evidence that SARS-CoV-2 co-infections with enteroviruses may actually lessen the severity of SARS-CoV-2, providing critical evidence or understanding the interaction between the viruses. While the direct impact of SARS-CoV-2 co-infections with enteroviruses are still being studied, current animal and cell models provide promising evidence that enteroviruses may mitigate the effects of severe SARS-CoV-2 symptoms. Overall, there is still a need for further research on the prevalence of these co-infections and how they affect different populations.

2.5. Rhinoviruses

A study in Southern Brazil assessing 20 respiratory pathogens during the COVID-19 pandemic uncovered significant findings about SARS-CoV-2 and rhinovirus co-infection in children between two and 18 years of age. The study found that out of 436 participants, 49.5% were infected with rhinovirus making it the most detected pathogen. 7.1% of participants had co-infection with rhinovirus and SARS-CoV-2. Consequently, rhinovirus had a higher hospitalization rate when co-infection occurred with another virus, including SARS-CoV-2, while SARS-CoV-2 infection alone had a lower hospitalization rate [

41]. Another study in 2020 in Brazil found that other than SARS-CoV-2, rhinovirus appeared to be the main virus circulating at the time. In their study, they found that rhinovirus was the only virus to co-occur with SARS-CoV-2, with seven out of 91 patients experiencing SARS-CoV2+rhinovirus co-infection [

42].

A complication arises in diagnosing COVID-19 with rhinovirus and SARS-CoV-2, expressing similarly regarding patient symptoms. For this reason, comprehensive testing is emphasized to account for any co-infections that may occur. This can be done through RT-PCR testing, which can detect multiple pathogens. Overall, current studies that have explored co-infection between SARS-CoV-2 and rhinovirus have highlighted the importance of understanding SARS-CoV-2 infection and management in pediatric populations. While SARS-CoV-2 alone may only cause mild illness in children compared to adults, the presence of rhinoviruses may lead to more severe illness and hospitalization, which is a significant cause for concern [

41].

2.6. PIV

One study used a multiplexed respiratory panel (RP) test, BioFire RP 2.1, which tests for a broad range of respiratory viruses at once using samples from nasopharyngeal swabs. This study found that there were no co-infections between PIV-1 and SARS-CoV-2. PIV-2+SARS-CoV2 accounted for 0.89%, PIV-4+SARS-CoV-2 0.48%, and PIV-3+SARS-CoV2 1.77% [

43]. While these percentages are relatively low, co-infections of PIV and SARS-CoV-2 are known to exacerbate symptoms and call for more supportive care than a singular infection might.

Further, a recent case of co-infection was studied in a 73-year-old woman with a history of bilateral bronchiectasis [

44]. She came to the hospital presenting with symptoms of fever, rhinitis, and increased dyspnoea. Physicians ran a BioFire panel on her and discovered that she was co-infected with both SARS-CoV-2 and PIV-3. Accordingly, she was placed in the intensive care unit of the hospital and was treated for parainfluenza with injectable Cefaperazone+ Sulbactam and Oseltamivir, as well as steroids and low molecular weight heparin for high D dimer levels. Her health quickly turned around, and she was able to leave the hospital after eight days. This case emphasizes the need for early detection of co-infections as they can lead to more severe illnesses. In this case, the patient was able to return to good health swiftly because she was treated quickly [

44]. Even though co-infections with various respiratory viruses are relatively infrequent, the importance of comprehensive viral testing is evident for understanding the effects and early detection in patients who may experience severe illness if not treated [

44].

2.7. Adenovirus

Adenovirus circulate and cause respiratory infections year around (

Figure 1). Studies have shown that only 5-7% of SARS-CoV-2 co-infections are adenovirus related [

45]. While co-infection between adenoviruses and SARS-CoV-2 is generally rare, it is still vital to consider adenoviruses when diagnostic testing as they could potentially lead to more severe outcomes. While adenoviruses account for only a small percentage of respiratory viral co-infections, when reported, they have typically been in individuals with underlying health conditions. One reported case in Colombia was a 40-year-old diabetic man whose diabetes was poorly taken care of. He experienced adverse symptoms from COVID-19, and it was discovered that he had a co-infection with adenovirus. This exemplifies why it is crucial to test for multiple pathogens, even when it is typically a rare occurrence [

46]. It is possible that adenovirus and SARS-CoV-2 co-infection may cause adverse clinical outcomes in those with underlying health problems. It may require careful therapeutic management for those affected [

46].

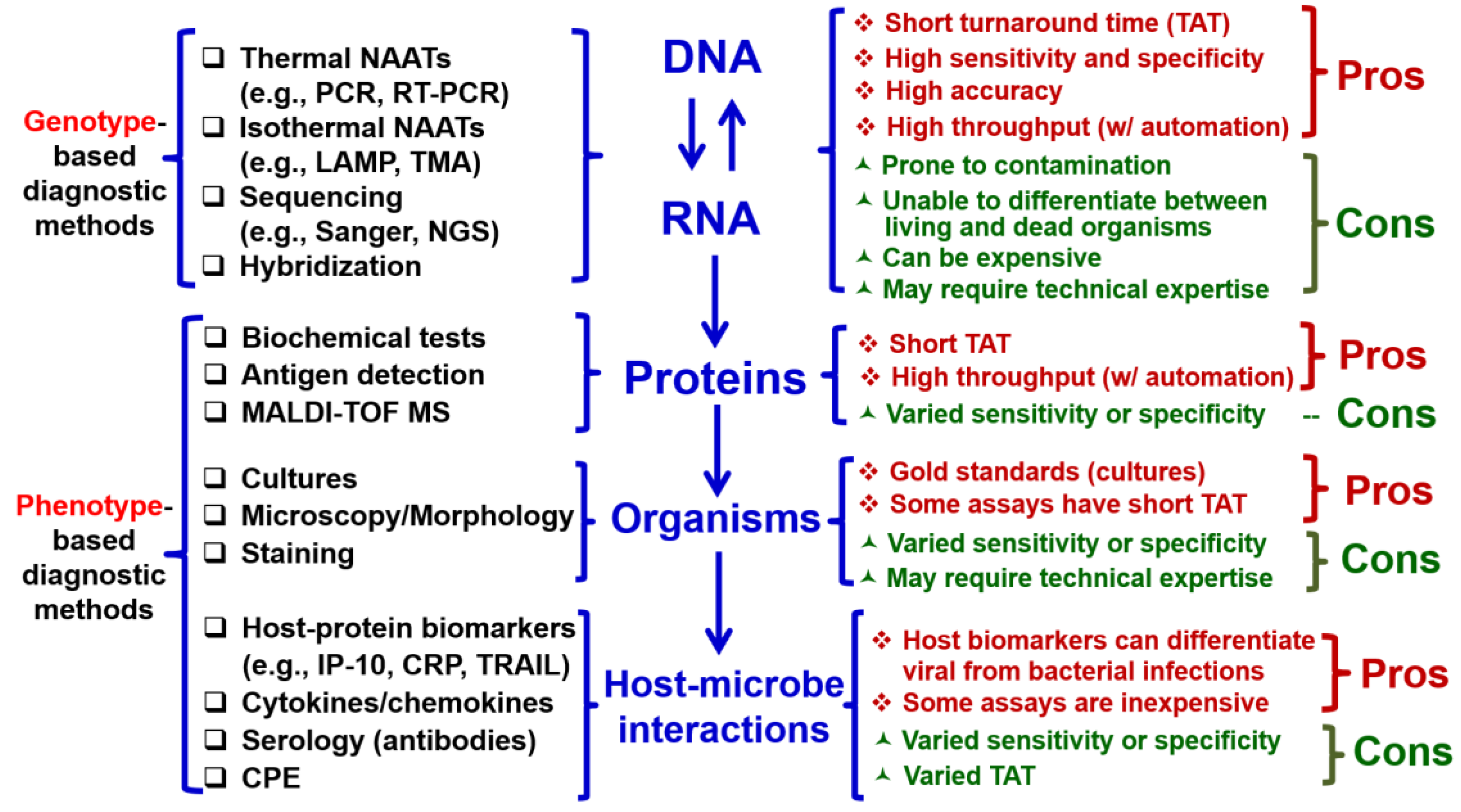

3. Multiplex Molecular Testing for Respiratory Viruses and Their Co-Infections

Historically, conventional procedures have been used for identification of microorganisms to aid in diagnosis of infectious diseases, which involves with detemining traits, antigens, morphology, and human antibodies by performing cultures, microscopy, serology (

Figure 2, left) [

47,

48]. However, these diagnostic methods based on phenotype suffer from delayed turn-around time (TAT), low sensitivity and specificity, and requirement of special technical expertise (

Figure 2, right). The paradigm of microorganism workup in the field of clinical microbiology has been dramatically changed with the advent of molecular biology and genotype-based diagnostic methods targeting nucleic acid (NA; DNA or RNA) [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53]. For example, NA amplification (NAA) tests (NAATs), sequencing (Sanger or next-generation sequencing) and hybridization (

Figure 2, left) have short TAT, high sensitivity and specificity, and high accuracy compared with conventional phenotypic methods (

Figure 2, right) [

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59].

The invention of multiplex PCR allows for simultaneous detection of multiple orgasnisms in one reaction[

60]. However, there are several bottlenecks for one-well multiplex PCR, including but not limited to, undesirable primer-primer interactions, non-specific amplification, crosstalk between detection channels, and a limited numbers of detection channels [

60]. The development of multiplex syndromic panels have overcomed these hurdle to expand their panel and cover more organisms. We discuss some examples of FDA-approved multiplex syndromic panels and their application to the detection of respiratory viruses [

60].

3.1. BioFire Respiratory Panel 2.1

With the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, respiratory panels for diagnostic testing were altered to include SARS-CoV-2, one being the BioFire respiratory panel 2.1 [

12]. Biofire respiratory panel 2.1 (RP 2.1) is a multiplex PCR diagnostic tool that can detect singular infections and co-infections of 22 pathogens (19 viral and 3 bacterial) by using nasopharyngeal swab specimens (

Table 1). This highly efficient panel can be completed within approximately 45 minutes which allows patients and physicians to understand the current course of the illness and treatment options quicker. This test has an overall 97.1% sensitivity and 99.3% specificity [

14]. The Biofire Respiratory 2.1 plus panel is an updated version that accounts for the original 22 pathogens with the addition of MERS-CoV. This tool has an overall sensitivity of 97.1% and 99.3% specificity [

15]. Considering that RP 2.1 and RP 2.1 plus both have high sensitivity and specificity, it can be inferred that they are an efficient and accurate way of detecting SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory pathogens [

72].

3.2. BioFire Spotfire

The BioFire Spotfire Respiratory Panel is a multiplex diagnostic tool that can detect up to 15 respiratory pathogens in approximately 15 minutes, using nasopharyngeal or throat swab specimens (

Table 1). It is typically used in point of care settings where rapid results are ideal for patient convenience. The overall sensitivity of Biofire Spotfire is 98.5%, while the specificity is 99.1% For SARS-CoV-2 detection, the sensitivity is 97.3%, with a specificity of 99.4%. In addition, there is a smaller scale version of this diagnostic test called the Spotfire Respiratory Panel Mini. This version can only target 5 pathogens, including SARS-CoV-2, human rhinovirus, influenza A, influenza B, and RSV. Further, the overall sensitivity of this tool is 98.7%, while the specificity is 98%. For detection of SARS-CoV-2, the sensitivity is 97.3%, with a specificity of 99.4% [

13,

17]. Both versions of this diagnostic tool have relatively high sensitivity and specificity, indicating that they provide accurate detection. Though, in comparison to Biofire RP 2.1, they do not detect as many respiratory pathogens, so they cannot account for all possible co-infections. However, the turnaround time for this panel is far quicker (15 minutes vs. 45 minutes), which may be more feasible in POC settings such as urgent cares that need to supply patients with instant results.

3.3. Roche Cobas (GenMark) Eplex Respiratory Pathogen Panel 2 (RP2) Panel

The cobas eplex RP2 Panel is a NA multiplex respiratory panel that can detect and differentiate nucleic acids from up to 17 viral and bacterial pathogens within 90 minutes using nasopharyngeal swap specimens (

Table 1). For enterovirus and rhinovirus specifically, this diagnostic panel cannot accurately differentiate between the two, so further testing would be needed for patients who test positive. This test was designed with the intention of lessening the occurrence of false positive results however, false negatives and false positives are still possible outcomes and patients should exercise caution if they believe they have been exposed regardless of their results [

18,

21]. The TAT of this panel consisting of NA extraction and amplification and detection is 90 minutes, not as fast as the others. The TAT makes this panel more suitable for larger laboratory settings where rapid testing is not the priority.

3.4. Qiagen Respiratory Panel

The QIAstat-Dx Respiratory Panel Plus is a diagnostic respiratory panel that uses nasopharyngeal swab specimens to detect up to 21 viral and bacterial pathogens within an hour. This respiratory panel utilizes a multiplex RT-PCR which is favorable for detecting co-infections in patient samples [

73,

74]. This is also referred to as syndromic testing which means that it can quickly detect pathogens that have overlapping symptoms [

75]. By being able to detect pathogens with similar symptoms, as well as co-infections, the QIAstat-Dx Respiratory Panel removes the need for multiple tests being needed to diagnose patients [

74]. In comparison to the other tests, it is better suited for diagnosing co-infections. Like the cobas eplex respiratory panel, QIAstat-Dx Respiratory Panel Plus cannot differentiate between enterovirus and rhinovirus. It has a slightly higher TAT than some of the other diagnostic tools at around 1 hour, but the fact that it is a syndromic test is convenient in that it can eliminate the need for other diagnostic testing and would likely be best used on patients with experiencing symptoms that are common for multiple pathogens [

72].

3.5. Luminex RPP

The NxTAG Respiratory Pathogen Panel (NxTAG RPP) is a a multiplex PCR diagnostic tool by Luminex (

Table 1). This method of diagnostic testing can detect up to 19 pathogens of viral and bacterial origin, including SARS-CoV-2 from upper respiratory tract specimens. It takes around 3.5-5 hours for results to be available, but it can hold up to 48-96 patient samples at a time, as it houses 96-well plates. This makes it ideal in a setting like a hospital where it may be most feasible to test patient specimens in large batches. Additionally, the main target for this method of testing is patients presenting with symptoms of respiratory tract infections [

76,

77]. In comparison with other respiratory diagnostic tools, the NxTAG RPP has a longer TAT for results, but it can test a larger number of patient specimens at once which makes it more suitable in a larger scale setting like a hospital or medical laboratory where rapid testing in less than an hour is not the highest priority.

4. Conclusions

SARS-CoV-2 is a novel, highly-pathogenic HCoV that caused the COVID-19 pandemic around the world. The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 has wiped out other respiratory viruses e.g., influenza viruses and RSV during the COVID pandemic, which is attributed to public health mitigation procedures. In the post-COVID era, the epidemiology and seasonality of the traditional respiratory viruses has shifted partially due to the co-circulation with SARS-CoV-2. With SARS-CoV-2 and traditional respiratory virues sharing similar symptoms but may differ in clinical outcomes and treatment options, rapid detection and differentiation of SARS-CoV-2 and other traditional respiratory viruses are critical. Multiplex molecular testings, e.g., PCR, are the mainstay detection strategy. BioFire, GenMark, Luminex and Qiagen technologies have their advantages and limitations which are northy noting. This review provides updated information on epidemiology, seasonality and clinical significance of respiratory viruses and co-infections in the post-COVID era. It also sheds light on cutting-edge techonlogies for the simultaneously detection of respiratory viruses and SARS-CoV-2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M.C.; writing—review and editing, K.M.C. and B.M.L.; visualization, K.M.C. and B.M.L.; supervision, B.M.L.; project administration, B.M.L.; funding acquisition, B.M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication resulted, in part, from research supported by the District of Columbia Center for AIDS Research, an NIH-funded program (P30AI117970), which is supported by the following NIH Co-Funding and Participating Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, NIA, NIDDK, NIMHD, NIDCR, NINR, FIC, and OAR. Research reported in this work was also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the NIAID of the NIH under award number U54AI150225. BML was also supported by The Robert H. Parrot Chair for Pediatric Research at Children's National Hospital and intramural funds provided by the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support from the Medical Microbiology Laboratory of Children's National Hospital.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.-L.; Wang, X.-G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.-R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.-L.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.M.; Hill, H.R. Role of Host Immune and Inflammatory Responses in COVID-19 Cases with Underlying Primary Immunodeficiency: A Review. J. Interf. Cytokine Res. 2020, 40, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauci, A.S.; Lane, H.C.; Redfield, R.R. Covid-19 — Navigating the Uncharted. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1268–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.M.; Martins, T.B.; Peterson, L.K.; Hill, H.R. Clinical significance of measuring serum cytokine levels as inflammatory biomarkers in adult and pediatric COVID-19 cases: A review. Cytokine 2021, 142, 155478–155478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebbani, A.V.; Pulakuntla, S.; Pannuru, P.; Aramgam, S.; Badri, K.R.; Reddy, V.D. COVID-19: comprehensive review on mutations and current vaccines. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 204, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carabelli, A.M.; Peacock, T.P.; Thorne, L.G.; Harvey, W.T.; Hughes, J.; COVID-19 Genomics UK Consortium; Peacock, S.J.; Barclay, W.S.; de Silva, T.I.; Towers, G.J.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant biology: immune escape, transmission and fitness. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.M.; Beck, E.M.; Fisher, M.A. The Brief Case: Ventilator-Associated Corynebacterium accolens Pneumonia in a Patient with Respiratory Failure Due to COVID-19. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 59, e0013721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.; Cai, Y.; Pang, C.; Wang, L.; McSweeney, S.; Shanklin, J.; Liu, Q. Structural basis for SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein recognition of human cell junction protein PALS1. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu BM, Yao Q, Cruz-Cosme R, Yarbrough C, Draper K, Suslovic W, Muhammad I, Contes KM, Hillyard DR, Teng, S., Tang, Q. Genetic conservation and diversity of SARS-CoV-2 Envelope gene across variants of concern.

- Schoeman, D.; Fielding, B.C. Is There a Link Between the Pathogenic Human Coronavirus Envelope Protein and Immunopathology? A Review of the Literature. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Li, N.L.; Wang, J.; Shi, P.-Y.; Wang, T.; Miller, M.A.; Li, K. Overlapping and Distinct Molecular Determinants Dictating the Antiviral Activities of TRIM56 against Flaviviruses and Coronavirus. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 13821–13835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagani, I.; Ghezzi, S.; Alberti, S.; Poli, G.; Vicenzi, E. Origin and evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2023, 138, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascella M, Rajnik M, Aleem A, et al. Features, Evaluation, and Treatment of Coronavirus (COVID-19) [Updated 2023 Aug 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554776/.

- Wang, L.-F.; Eaton, B.T. Bats, Civets and the Emergence of SARS. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2007, 315, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Middle East respiratory syndrome: global summary and assessment of risk. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MERS-RA-2022.

- Memish, Z.A.; Perlman, S.; Van Kerkhove, M.D.; Zumla, A. Middle East respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2020, 395, 1063–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, V.; Chavda, V.; Alshahrani, N.Z.; Mehta, R.; Satapathy, P.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; Sah, R. MERS outbreak in Riyadh: A current concern in Saudi Arabia. Le Infezioni in Medicina, 2024; 32, 264–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Influenza (seasonal) [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023 Sep. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal).

- Rezaee, D.; Bakhtiari, S.; Jalilian, F.A.; Doosti-Irani, A.; Asadi, F.T.; Ansari, N. Coinfection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and influenza virus during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch. Virol. 2023, 168, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Williams, D.J.; Arnold, S.R.; Ampofo, K.; Bramley, A.M.; Reed, C.; Stockmann, C.; Anderson, E.J.; Grijalva, C.G.; Self, W.H.; et al. Community-Acquired Pneumonia Requiring Hospitalization among US Children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padda IS, Parmar M. COVID (SARS-CoV-2) Vaccine. [Updated 2023 Jun 3]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567793/.

- Nunziata, F.; Salomone, S.; Catzola, A.; Poeta, M.; Pagano, F.; Punzi, L.; Vecchio, A.L.; Guarino, A.; Bruzzese, E. Clinical Presentation and Severity of SARS-CoV-2 Infection Compared to Respiratory Syncytial Virus and Other Viral Respiratory Infections in Children Less than Two Years of Age. Viruses 2023, 15, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Upadhyay, P.; Reddy, J.; Granger, J. SARS-CoV-2 respiratory co-infections: Incidence of viral and bacterial co-pathogens. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 105, 617–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pipek, O.A.; Medgyes-Horváth, A.; Stéger, J.; Papp, K.; Visontai, D.; Koopmans, M.; Nieuwenhuijse, D.; Munnink, B.B.O.; Cochrane, G.; et al.; VEO Technical Working Group Systematic detection of co-infection and intra-host recombination in more than 2 million global SARS-CoV-2 samples. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Z.; He, W.; Sun, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, M.; Chang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zeng, W.; et al. Influenza and COVID-19 co-infection and vaccine effectiveness against severe cases: a mathematical modeling study. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1347710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.M.; Rakhmanina, N.Y.; Yang, Z.; Bukrinsky, M.I. Mpox (Monkeypox) Virus and Its Co-Infection with HIV, Sexually Transmitted Infections, or Bacterial Superinfections: Double Whammy or a New Prime Culprit? Viruses 2024, 16, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.Y.; Boftsi, M.; Staudt, L.; McElroy, J.A.; Li, T.; Duong, S.; Ohler, A.; Ritter, D.; Hammer, R.; Hang, J.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 and influenza co-infection: A cross-sectional study in central Missouri during the 2021–2022 influenza season. Virology 2022, 576, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris DR, Qu Y, Thomason KS, de Mello AH, Preble R, Menachery VD, Casola A, Garofalo RP. The impact of RSV/SARS-CoV-2 co-infection on clinical disease and viral replication: insights from a BALB/c mouse model. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023 May 24:2023.05.24.542043. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mandelia, Y.; Procop, G.; Richter, S.; Worley, S.; Liu, W.; Esper, F. Dynamics and predisposition of respiratory viral co-infections in children and adults. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 27, 631.e1–631.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi, S.; Safamanesh, S.; Ghasemzadeh-Moghaddam, H.; Ghafouri, M.; Mohajerzadeh-Heydari, M.; Namdar-Ahmadabad, H.; Azimian, A. Report of death in children with SARS-CoV-2 and human metapneumovirus (hMPV) coinfection: Is hMPV the trigger? J. Med Virol. 2020, 93, 579–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touzard-Romo, F. , Tapé, C., Lonks JR. Co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 and Human Metapneumovirus. Rhode Island Medical Journal. 2020 Mar.

- Maltezou, H.C.; Papanikolopoulou, A.; Vassiliu, S.; Theodoridou, K.; Nikolopoulou, G.; Sipsas, N.V. COVID-19 and Respiratory Virus Co-Infections: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Viruses 2023, 15, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair W, Omar M. Enterovirus. [Updated 2023 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562330/.

- Liu, B. Universal PCR Primers Are Critical for Direct Sequencing-Based Enterovirus Genotyping. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 339–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.M.; Mulkey, S.B.; Campos, J.M.; DeBiasi, R.L. Laboratory diagnosis of CNS infections in children due to emerging and re-emerging neurotropic viruses. Pediatr. Res. 2023, 95, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair W, Omar M. Enterovirus. [Updated 2023 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562330/#.

- Maltezou, H.C.; Papanikolopoulou, A.; Vassiliu, S.; Theodoridou, K.; Nikolopoulou, G.; Sipsas, N.V. COVID-19 and Respiratory Virus Co-Infections: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Viruses 2023, 15, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khasawneh, A.I.; Himsawi, N.M.; Abu-Raideh, J.A.; Sammour, A.; Abu Safieh, H.; Obeidat, A.; Azab, M.; Tarifi, A.A.; Al Khawaldeh, A.; Al-Momani, H.; et al. Prevalence of SARS-COV-2 and other respiratory pathogens among a Jordanian subpopulation during Delta-to-Omicron transition: Winter 2021/2022. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svyatchenko, V.A.; Legostaev, S.S.; Lutkovskiy, R.Y.; Protopopova, E.V.; Ponomareva, E.P.; Omigov, V.V.; Taranov, O.S.; Ternovoi, V.A.; Agafonov, A.P.; Loktev, V.B. Coxsackievirus A7 and Enterovirus A71 Significantly Reduce SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Cell and Animal Models. Viruses 2024, 16, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amstutz, P.; Bahr, N.C.; Snyder, K.; Shoemaker, D.M. Pneumocystis jiroveciiInfections Among COVID-19 Patients: A Case Series and Literature Review. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, ofad043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, F.H.; Sartor, I.T.S.; Polese-Bonatto, M.; Azevedo, T.R.; Kern, L.B.; Fazolo, T.; de David, C.N.; Zavaglia, G.O.; Fernandes, I.R.; Krauser, J.R.M.; et al. Rhinovirus as the main co-circulating virus during the COVID-19 pandemic in children. J. de Pediatr. 2022, 98, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.F.B.; Suguita, P.; Litvinov, N.; Farhat, S.C.L.; de Paula, C.S.Y.; Lázari, C.d.S.; Bedê, P.V.; Framil, J.V.d.S.; Bueno, C.; Branas, P.C.A.A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 and rhinovirus infections: are there differences in clinical presentation, laboratory abnormalities, and outcomes in the pediatric population? Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2022, 64, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westbrook, A.; Wang, T.M.; Bhakta, K.B.; Sullivan, J.B.; Gonzalez, M.D.; Lam, W.; Rostad, C.A. Respiratory Coinfections in Children With SARS-CoV-2. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2023, 42, 774–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiody, S.; Aravind, T.R. Coinfection with SARS-CoV-2 and parainfluenza virus in an elderly patient: a case report. Int J Community Med Public Health 2024, 11, 2056–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svyatchenko, V.A.; Ternovoi, V.A.; Lutkovskiy, R.Y.; Protopopova, E.V.; Gudymo, A.S.; Danilchenko, N.V.; Susloparov, I.M.; Kolosova, N.P.; Ryzhikov, A.B.; Taranov, O.S.; et al. Human Adenovirus and Influenza A Virus Exacerbate SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Animal Models. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motta, J.C.; Gómez, C.C. Adenovirus and novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov2) coinfection: A case report. IDCases 2020, 22, e00936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.M.; Carlisle, C.P.; Fisher, M.A.; Shakir, S.M. The Brief Case: Capnocytophaga sputigena Bacteremia in a 94-Year-Old Male with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, Pancytopenia, and Bronchopneumonia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 59, e0247220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray PR, Baron EJ, Jorgensen JH, Landry ML, Pfaller MA (ed). 2006. Manual of clinical microbiology: Volume 1. 9th ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- Liu, B.-M.; Li, T.; Xu, J.; Li, X.-G.; Dong, J.-P.; Yan, P.; Yang, J.-X.; Yan, L.; Gao, Z.-Y.; Li, W.-P.; et al. Characterization of potential antiviral resistance mutations in hepatitis B virus reverse transcriptase sequences in treatment-naïve Chinese patients. Antivir. Res. 2009, 85, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Liu, B.; Zhao, C.; Yang, J.; Yan, C.; Yan, L.; Zhuang, H.; Li, T. Amino acid similarities and divergences in the small surface proteins of genotype C hepatitis B viruses between nucleos(t)ide analogue-naïve and lamivudine-treated patients with chronic hepatitis B. Antivir. Res. 2013, 102, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Yang, J.X.; Yan, L.; Zhuang, H.; Li, T. Novel HBV Recombinants between Genotypes B and C in 3'-terminal Reverse Transcriptase (RT) Sequences are Associated with Enhanced Viral DNA Load, Higher RT Point Mutation Rates and Place of Birth among Chinese Patients. Infection, Genetics & Evolution 2018, 57, 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Liu, B.; Hou, J.; Sun, J.; Hao, R.; Xiang, K.; Yan, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhuang, H.; Li, T. Naturally occurring deletions/insertions in HBV core promoter tend to decrease in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B patients during antiviral therapy. Antiviral Therapy. 2015, 20, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.M.; Rakhmanina, N.Y.; Yang, Z.; Bukrinsky, M.I. Mpox (Monkeypox) Virus and Its Co-Infection with HIV, Sexually Transmitted Infections, or Bacterial Superinfections: Double Whammy or a New Prime Culprit? Viruses 2024, 16, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, B.; Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Ding, H.; Li, T. Discrepancy of potential antiviral resistance mutation profiles within the HBV reverse transcriptase between nucleos(t)ide analogue-untreated and -treated patients with chronic hepatitis B in a hospital in China. J. Med Virol. 2011, 84, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Panda, D.; Mendez-Rios, J.D.; Ganesan, S.; Wyatt, L.S.; Moss, B. Identification of Poxvirus Genome Uncoating and DNA Replication Factors with Mutually Redundant Roles. J. Virol. 2018, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-X.; Liu, B.-M.; Li, X.-G.; Yan, C.-H.; Xu, J.; Sun, X.-W.; Wang, Y.-H.; Jiao, X.-J.; Yan, L.; Dong, J.-P.; et al. Profile of HBV antiviral resistance mutations with distinct evolutionary pathways against nucleoside/ nucleotide analogue treatment among Chinese chronic hepatitis B patients. Antivir. Ther. 2010, 15, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Totten, M.; Nematollahi, S.; Datta, K.; Memon, W.; Marimuthu, S.; Wolf, L.A.; Carroll, K.C.; Zhang, S.X. Development and Evaluation of a Fully Automated Molecular Assay Targeting the Mitochondrial Small Subunit rRNA Gene for the Detection of Pneumocystis jirovecii in Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid Specimens. J Mol Diagn. 2020, 22, 1482–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.M. Epidemiological and clinical overview of the 2024 Oropouche virus disease outbreaks, an emerging/re-emerging neurotropic arboviral disease and global public health threat. J. Med Virol. 2024, 96, e29897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Forman, M.; Valsamakis, A. Optimization and Evaluation of a Novel Real-Time RT-PCR Test for Detection of Parechovirus in Cerebrospinal Fluid. 2019, 272, 113690. [CrossRef]

- Elnifro, E.M.; Ashshi, A.M.; Cooper, R.J.; Klapper, P.E. Multiplex PCR: Optimization and Application in Diagnostic Virology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 13, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Li, N.L.; Shen, Y.; Bao, X.; Fabrizio, T.; Elbahesh, H.; Webby, R.J.; Li, K. The C-Terminal Tail of TRIM56 Dictates Antiviral Restriction of Influenza A and B Viruses by Impeding Viral RNA Synthesis. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 4369–4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.M.; Li, N.L.; Wang, R.; Li, X.; Li, Z.A.; Marion, T.N.; Li, K. Key roles for phosphorylation and the Coiled-coil domain in TRIM56-mediated positive regulation of TLR3-TRIF–dependent innate immunity. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Li, N.L.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Lester, S.; Li, K. TRIM56 Is an Essential Component of the TLR3 Antiviral Signaling Pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 36404–36413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Qiu, C.; Miao, R.; Zhou, J.; Lee, A.; Liu, B.; Lester, S.N.; Fu, W.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, L.; et al. MCPIP1 restricts HIV infection and is rapidly degraded in activated CD4+ T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 110, 19083–19088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Wang, N.; Lee, Y.-M.; Liu, C.; Li, K. TRIM56 Is a Virus- and Interferon-Inducible E3 Ubiquitin Ligase That Restricts Pestivirus Infection. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 3733–3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, D.; Li, N.L.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, B.; Kumthip, K.; Wang, T.T.; Huo, D.; Ingels, J.F.; Lu, L.; Shang, J.; et al. The Molecular Chaperone GRP78 Contributes to Toll-like Receptor 3-mediated Innate Immune Response to Hepatitis C Virus in Hepatocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 12294–12309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Li, N.L.; Wei, D.; Liu, B.; Guo, F.; Elbahesh, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, G.-Y.; Li, K. The E3 ligase TRIM56 is a host restriction factor of Zika virus and depends on its RNA-binding activity but not miRNA regulation, for antiviral function. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeMessurier, K.S.; Rooney, R.; Ghoneim, H.E.; Liu, B.; Li, K.; Smallwood, H.S.; Samarasinghe, A.E. Influenza A virus directly modulates mouse eosinophil responses. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2020, 108, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, BM. History of global food safety, foodborne illness, and risk assessment. In History of Food and Nutrition Toxicology; Academic Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; pp. 301–316. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.M. Isothermal nucleic acid amplification technologies and CRISPR-Cas based nucleic acid detection strategies for in-fectious disease diagnostics. In Manual of Molecular Microbiology; ASM Press, Washington, DC, USA, 2026. (In Press).

- Liu, B.M.; Hayes, A.W. Mechanisms and Assessment of Genotoxicity of Metallic Engineered Nanomaterials in the Human Environment. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmanan, K.; Liu, B.M. Impact of Point-of-Care Testing on Diagnosis, Treatment and Surveillance of Vaccine-Preventable Viral Infections. Preprints 2024, 2024120061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrrell, C.S.; Allen, J.L.Y.; Gkrania-Klotsas, E. Influenza: epidemiology and hospital management. Medicine 2021, 49, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, Z.; Tan, S.; Ma, D. Respiratory syncytial virus: from pathogenesis to potential therapeutic strategies. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 4073–4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Yan, R.; Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, C.; Jiang, D.; Yang, M.; Cao, K.; Chen, M.; You, Y.; et al. Global burden and trends of respiratory syncytial virus infection across different age groups from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease 2019 Study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 135, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Lung Association. Treatment for RSV [Internet]. Chicago: American Lung Association; 2024. Available from: https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/rsv/treatment.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) [Internet]. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2024. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/about/index.html.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).