Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Lifetime Stressor Exposure

2.2.2. Early Adversity

2.2.3. Life Events

2.2.4. Perceived Stress

2.2.5. Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms

2.3. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Usability and Acceptability

3.2. Descriptive Statistics for Lifetime Stressor Exposure for Men and Women

3.3. Validity

3.3.1. Concurrent Validity

3.3.2. Predictive Validity

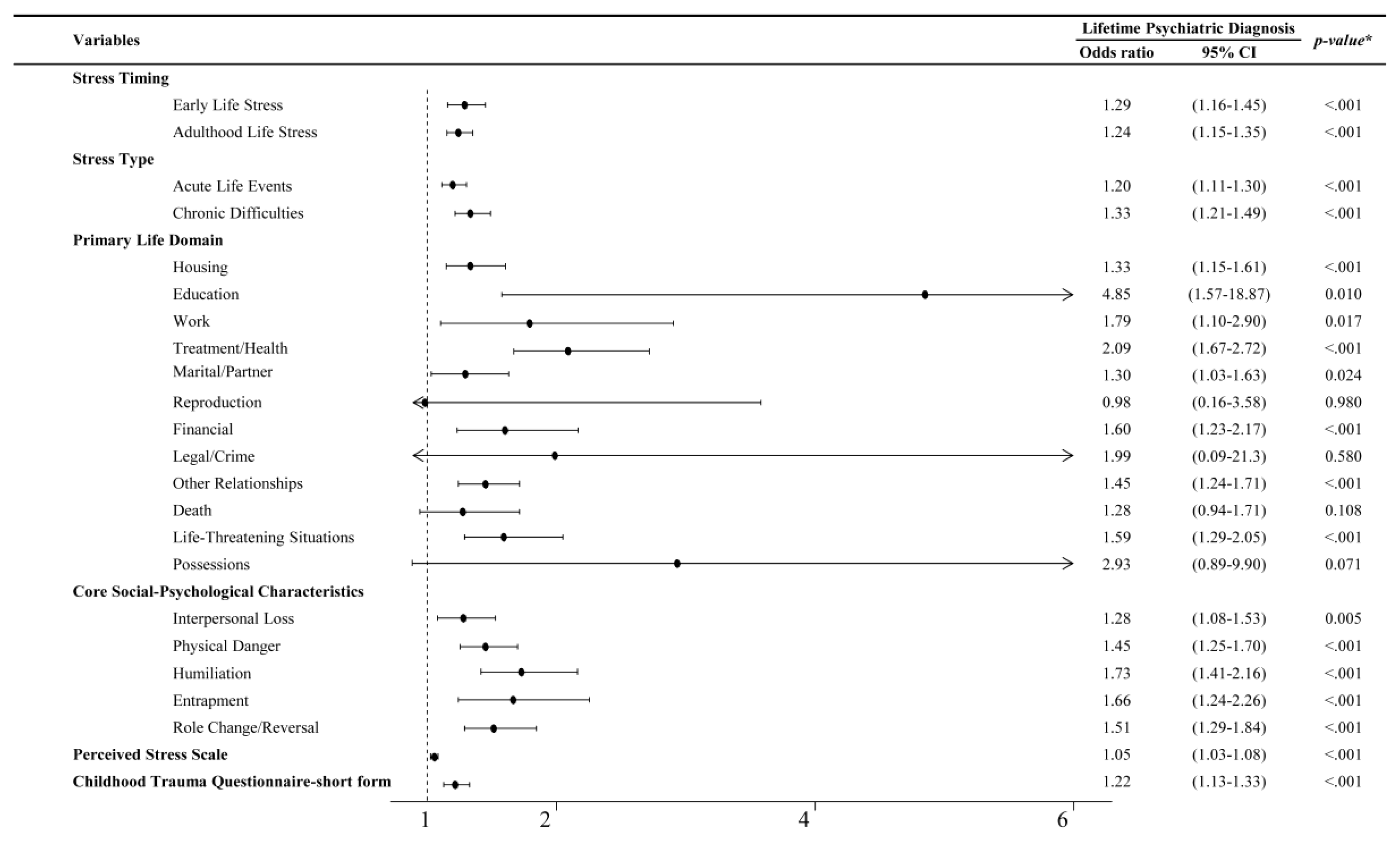

3.3.3. Comparative Predictive Validity of Each Variable for Lifetime Psychiatric Diagnosis

3.4. Test-Retest Reliability

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Selye, H. The Stress of Life; McGraw Hill: New York, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Epel, E.S.; Blackburn, E.H.; Lin, J.; Dhabhar, F.S.; Adler, N.E.; Morrow, J.D.; Cawthon, R.M. Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2004, 101, 17312–17315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, A.; Litzelman, K.; Wisk, L.E.; Maddox, T.; Cheng, E.R.; Creswell, P.D.; Witt, W.P. Does the perception that stress affects health matter? The association with health and mortality. Health Psychol 2012, 31, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, D.B.; Thayer, J.F.; Vedhara, K. Stress and health: a review of psychobiological processes. Annu Rev Psychol 2021, 72, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautarescu, A.; Craig, M.C.; Glover, V. Chapter Two - Prenatal stress: Effects on fetal and child brain development. Int Rev Neurobiol 2020, 150, 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Strathearn, L.; Giannotti, M.; Mills, R.; Kisely, S.; Najman, J.; Abajobir, A. Long-term cognitive, psychological, and health outcomes associated with child abuse and neglect. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20200438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.I.; Smyth, N.; Hall, S.J.; Torres, S.J.; Hussein, M.; Jayasinghe, S.U.; Ball, K.; Clow, A.J. Psychological stress reactivity and future health and disease outcomes: a systematic review of prospective evidence. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2020, 114, 104599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monroe, S.; Slavich, G. Psychological stressors: overview. In Stress: Concepts, Cognition, Emotion, and Behavior; Elsevier, 2016; pp. 109–115.

- Biggs, A.; Brough, P.; Drummond, S. Lazarus and Folkman’s psychological stress and coping theory. In The Handbook of Stress and Health: A Guide to Research and Practice; Wiley Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 349–364. [Google Scholar]

- Schneiderman, N.; Ironson, G.; Siegel, S.D. Stress and health: psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2005, 1, 607–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segerstrom, S.C.; Miller, G.E. Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull 2004, 130, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, T.H. Life situations, emotions, and disease. Psychosomatics 1978, 19, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolai, K.A.; Laney, T.; Mezulis, A.H. Different stressors, different strategies, different outcomes: how domain-specific stress responses differentially predict depressive symptoms among adolescents. J Youth Adolesc 2013, 42, 1183–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavich, G.M.; O’Donovan, A.; Epel, E.S.; Kemeny, M.E. Black sheep get the blues: a psychobiological model of social rejection and depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2010, 35, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epel, E.S.; Crosswell, A.D.; Mayer, S.E.; Prather, A.A.; Slavich, G.M.; Puterman, E.; Mendes, W.B. More than a feeling: A unified view of stress measurement for population science. Front Neuroendocrinol 2018, 49, 146–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkelsen, S.; Coggon, D.; Andersen, J.H.; Casey, P.; Flachs, E.M.; Kolstad, H.A.; Mors, O.; Bonde, J.P. Are depressive disorders caused by psychosocial stressors at work? A systematic review with metaanalysis. Eur J Epidemiol 2021, 36, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, C.; Ge, Y.; Tang, B.; Liu, Y.; Kang, P.; Wang, M.; Zhang, L. A meta-analysis of risk factors for combat-related PTSD among military personnel and veterans. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0120270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavich, G.M.; Irwin, M.R. From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: a social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychol Bull 2014, 140, 774–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavich, G.M.; Sacher, J. Stress, sex hormones, inflammation, and major depressive disorder: extending Social Signal Transduction Theory of Depression to account for sex differences in mood disorders. Psychopharmacology 2019, 236, 3063–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rentscher, K.E.; Carroll, J.E.; Mitchell, C. Psychosocial stressors and telomere length: a current review of the science. Annu Rev Public Health 2020, 41, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Shin, C.; Ko, Y.-H.; Lim, J.; Joe, S.-H.; Kim, S.; Jung, I.-K.; Han, C. The reliability and validity studies of the Korean version of the Perceived Stress Scale. Korean J Psychom Med 2012, 20, 127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Chandola, T.; Brunner, E.; Marmot, M. Chronic stress at work and metabolic syndrome: a prospective study. BMJ 2006, 332, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Janicki-Deverts, D. Who’s stressed? Distributions of psychological stress in the United States in probability samples from 1983, 2006, and 2009 1. J Appl Soc Psychol 2012, 42, 1320–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, H.; Kim, D.; Koh, H.; Kim, Y.; Park, J.S. Psychometric properties of the Life Events Checklist-Korean version. Psychiatry Investig 2008, 5, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armour, C.; Carragher, N.; Elhai, J.D. Assessing the fit of the dysphoric arousal model across two nationally representative epidemiological surveys: the Australian NSMHWB and the United States NESARC. J Anxiety Disord 2013, 27, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Koss, M.P.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Park, S.C.; Yang, H.; Oh, D.H. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the childhood trauma questionnaire-short form for psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatry Investig 2011, 8, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazassa, M.J.; Oliveira, M. d. S.; Spahr, C.M.; Shields, G.S.; Slavich, G.M. The Stress and Adversity Inventory for Adults (Adult STRAIN) in Brazilian Portuguese: initial validation and links with executive function, sleep, and mental and physical health. Front Psychol 2020, 10, 3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavich, G.M.; Shields, G.S. Assessing lifetime stress exposure using the Stress and Adversity Inventory for Adults (Adult STRAIN): An overview and initial validation. Psychosom Med 2018, 80, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturmbauer, S.C.; Shields, G.S.; Hetzel, E.-L.; Rohleder, N.; Slavich, G.M. The stress and adversity inventory for adults (adult STRAIN) in German: an overview and initial validation. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0216419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, J.C.; Shields, G.S.; Trainor, B.C.; Slavich, G.M.; Yonelinas, A.P. Greater lifetime stress exposure predicts blunted cortisol but heightened DHEA responses to acute stress. Stress Health 2019, 35, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.L.; Slavich, G.M.; Chen, E.; Miller, G.E. Targeted rejection predicts decreased anti-inflammatory gene expression and increased symptom severity in youth with asthma. Psychol Sci 2015, 26, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raio, C.M.; Lu, B.B.; Grubb, M.; Shields, G.S.; Slavich, G.M.; Glimcher, P. Cumulative lifetime stressor exposure assessed by the STRAIN predicts economic ambiguity aversion. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosero-Pahi, M.; Andoh, J.; Shields, G.S.; Acosta-Ortiz, A.; Serrano-Gomez, S.; Slavich, G.M. Cumulative lifetime stressor exposure impairs stimulus–response but not contextual learning. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 13080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, G.S.; Ramey, M.M.; Slavich, G.M.; Yonelinas, A.P. Determining the mechanisms through which recent life stress predicts working memory impairments: precision or capacity? Stress 2019, 22, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavich, G.M.; Stewart, J.G.; Esposito, E.C.; Shields, G.S.; Auerbach, R.P. The Stress and Adversity Inventory for Adolescents (Adolescent STRAIN): associations with mental and physical health, risky behaviors, and psychiatric diagnoses in youth seeking treatment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2019, 60, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Stress, adaptation, and disease: allostasis and allostatic load. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1998, 840, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, F.; Shahwan, S.; Teh, W.L.; Sambasivam, R.; Zhang, Y.J.; Lau, Y.W.; Ong, S.H.; Fung, D.; Gupta, B.; Chong, S.A.; Subramaniam, M. The prevalence of childhood trauma in psychiatric outpatients. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2019, 18, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutin, E.; Schiweck, C.; Cornelis, J.; De Raedt, W.; Reif, A.; Vrieze, E.; Claes, S.; Van Hoof, C. The cumulative effect of chronic stress and depressive symptoms affects heart rate in a working population. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1022298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, S.E.; Prather, A.A.; Puterman, E.; Lin, J.; Arenander, J.; Coccia, M.; Shields, G.S.; Slavich, G.M.; Epel, E.S. Cumulative lifetime stress exposure and leukocyte telomere length attrition: the unique role of stressor duration and exposure timing. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 104, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, D. Korean adaptation of Spielberger’s STAI (K-STAI). Korean J Health Psychol 1996, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Y.; Lee, S.; Kim, J. Distinct and overlapping features of anxiety sensitivity and trait anxiety: the relationship to negative affect, positive affect, and physiological hyperarousal. Korean J Clin Psychol 2005, 24, 439–449. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, J.-K.; Kim, Y.; Choi, K.-H. The psychometric properties and clinical utility of the Korean versions of the GAD-7 and GAD-2. Front Psychiatry 2019, 10, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.; Jo, S.A.; Kwak, J.-H.; Pae, C.-U.; Steffens, D.; Jo, I.; Park, M.H. Validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Korean version in the elderly population: the Ansan Geriatric study. Compr Psychiatry 2008, 49, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, K.; Admon, L.K.; Winkelman, T.N.; Muzik, M.; Hall, S.; Dalton, V.K.; Zivin, K. Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders, serious mental illness, and delivery-related health outcomes, United States, 2006–2015. BMC Womens Health 2020, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussida, C.; Patimo, R. Women’s family care responsibilities, employment and health: a tale of two countries. J Fam Econ Issues 2021, 42, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madriz, E. Nothing Bad Happens to Good Girls: Fear of Crime in Women’s Lives; University of California Press: Berkeley/Los Angeles, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, S.; Haandrikman, K. Gendered fear of crime in the urban context: a comparative multilevel study of women’s and men’s fear of crime. J Urban Aff 2023, 45, 1238–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Gewirtz, A.H.; Sapienza, J.K. Resilience in Development: The Importance of Early Childhood; Centre of Excellence for Early Childhood Development: Montreal, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, C.A.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Harris, N.B.; Danese, A.; Samara, M. Adversity in childhood is linked to mental and physical health throughout life. BMJ 2020, 371, m3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, S.; Kim, S.; Zhang, H.; Dobalian, A.; Slavich, G.M. Lifetime adversity predicts depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairment in a nationally representative sample of older adults in the United States. J Clin Psychol 2024, 80, 1031–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burani, K.; Brush, C.J.; Shields, G.S.; Klein, D.N.; Nelson, B.; Slavich, G.M.; Hajcak, G. Cumulative lifetime acute stressor exposure interacts with reward responsiveness to predict longitudinal increases in depression severity in adolescence. Psychol Med 2023, 53, 4507–4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.L.M.; Sichko, S.; Bui, T.Q.; Libowitz, M.R.; Shields, G.S.; Slavich, G.M. Intergenerational transmission of lifetime stressor exposure in adolescent girls at differential maternal risk for depression. J Clin Psychol 2023, 79, 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulton, R.; Moffitt, T.E.; Silva, P.A. The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study: overview of the first 40 years, with an eye to the future. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2015, 50, 679–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, C.W.; Ickovics, J.R. Adolescent suicide in South Korea: risk factors and proposed multi-dimensional solution. Asian J Psychiatr 2019, 43, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavich, G.M. Social safety theory: a biologically based evolutionary perspective on life stress, health, and behavior. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2020, 16, 265–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavich, G.M. Social safety theory: understanding social stress, disease risk, resilience, and behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Curr Opin Psychol 2022, 45, 101299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavich, G.M.; Roos, L.G.; Mengelkoch, S.; Webb, C.A.; Shattuck, E.C.; Moriarity, D.P.; Alley, J.C. Social safety theory: conceptual foundation, underlying mechanisms, and future directions. Health Psychol Rev 2023, 17, 5–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.; Lee, J.; Yoo, M.S.; Ko, E. South Korean children’s academic achievement and subjective well-being: the mediation of academic stress and the moderation of perceived fairness of parents and teachers. Child Youth Serv Rev 2019, 100, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijbenga, L.; Reijneveld, S.A.; Almansa, J.; Korevaar, E.L.; Hofstra, J.; de Winter, A.F. Trajectories of stressful life events and long-term changes in mental health outcomes, moderated by family functioning? The TRAILS study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2022, 16, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.J.; Gooding, P.; Wood, A.M.; Tarrier, N. The role of defeat and entrapment in depression, anxiety, and suicide. Psychol Bull 2011, 137, 391–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, P.; Allan, S. The role of defeat and entrapment (arrested flight) in depression: an exploration of an evolutionary view. Psychol Med 1998, 28, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, R.C.; Kirtley, O.J. The integrated motivational-volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Phil Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 2018, 373, 20170268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Total (N = 218) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 29.5±6.02 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 79 (36.24) | |

| Female | 139 (63.76) | |

| Level of education (years) | 14.90±1.73 | |

| Occupational status | ||

| Employed | 171 (78.44) | |

| Unemployed | 47 (21.56) | |

| Medical history | ||

| Any | 66 (30.28) | |

| Endocrine disorder | 24 (11.01) | |

| Gastrointestinal disorder | 23 (10.55) | |

| Nervous disorder | 6 (2.75) | |

| Musculoskeletal disorder | 6 (2.75) | |

| Respiratory disorder | 5 (2.29) | |

| Genitourinary disorder | 4 (1.83) | |

| Cardiovascular disorder | 3 (1.38) | |

| Others | 7 (3.21) | |

| None | 152 (69.72) | |

| Psychiatric history | ||

| Any | 44 (20.33) | |

| Depressive disorder | 37 (16.97) | |

| Anxiety disorder | 31 (14.22) | |

| Insomnia disorder | 20 (9.17) | |

| Panic disorder | 7 (3.21) | |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 2 (0.92) | |

| Bipolar disorder | 1 (0.46) | |

| Adjustment disorder | 1 (0.46) | |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 0 (0.00) | |

| Schizophrenia | 0 (0.00) | |

| Others | 1 (0.46) | |

| None | 174 (79.66) | |

| Variables | Sex | p-value | ||

|

Men (n = 79) |

Women (n = 139) |

|||

| Total Lifetime Stressor Count | 8.68±6.61 | 11.46±11.63 | 0.052 | |

| Primary Life Domain | ||||

| Housing | 0.65±1.34 | 1.40±2.77 | 0.024* | |

| Education | 0.06±0.29 | 0.04±0.19 | 0.402 | |

| Work | 0.43±0.63 | 0.60±0.83 | 0.108 | |

| Treatment/Health | 1.49±2.19 | 1.55±2.01 | 0.856 | |

| Marital/Partner | 1.43±1.53 | 1.42±2.00 | 0.960 | |

| Reproduction | 0.00±0.00 | 0.12±0.42 | 0.015* | |

| Financial | 0.38±0.74 | 0.68±1.25 | 0.056 | |

| Legal/Crime | 0.06±0.29 | 0.01±0.12 | 0.084 | |

| Other Relationships | 1.70±2.13 | 2.09±2.54 | 0.241 | |

| Death | 0.96±1.32 | 0.76±1.16 | 0.246 | |

| Life-Threatening Situations | 0.65±1.39 | 1.32±2.53 | 0.030* | |

| Possessions | 0.03±0.16 | 0.08±0.30 | 0.136 | |

| Core Social-Psychological Characteristic | ||||

| Interpersonal Loss | 2.84±2.18 | 2.61±2.21 | 0.471 | |

| Physical Danger | 1.51±2.02 | 2.38±3.26 | 0.032* | |

| Humiliation | 1.25±1.83 | 1.47±2.00 | 0.433 | |

| Entrapment | 0.97±1.07 | 1.22±1.27 | 0.144 | |

| Role Change/Disruption | 1.65±2.05 | 2.81±4.32 | 0.025* | |

| M±SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | STRAIN Lifetime Stressor Count | 10.45±10.17 | 0.949* | 0.614* | 0.487* | 0.477* | |

| 2 | STRAIN Lifetime Stressor Severity | 25.17±25.07 | 0.604* | 0.473* | 0.509* | ||

| 3 | CTQ-SF | 39.42±14.33 | 0.331* | 0.472* | |||

| 4 | LEC | 1.66±2.32 | 0.219* | ||||

| 5 | PSS | 17.16±5.91 |

| STAI State | ||||||

| Model | Adj. R2 | Δ R2 | F | p | SE | β |

| Covariates | 0.23 | 13.97 | <0.001 | 9.64 | - | |

| Covariates + STRAIN Total Stressor Count | 0.35 | 0.12 | 20.47 | <0.001 | 8.86 | 0.44*** |

| Covariates + STRAIN Total Stressor Severity | 0.37 | 0.136 | 21.87 | <0.001 | 8.75 | 0.20*** |

| STAI Trait | ||||||

| Adj. R2 | Δ R2 | F | p | SE | β | |

| Covariates | 0.24 | 14.84 | <0.001 | 10.39 | - | |

| Covariates + STRAIN Total Stressor Count | 0.36 | 0.117 | 21.25 | <0.001 | 9.56 | 0.47*** |

| Covariates + STRAIN Total Stressor Severity | 0.39 | 0.15 | 24.28 | <0.001 | 9.31 | 0.23*** |

| PHQ-9 | ||||||

| Adj. R2 | Δ R2 | F | p | SE | β | |

| Covariates | 0.22 | 12.92 | <0.001 | 4.85 | - | |

| Covariates + STRAIN Total Stressor Count | 0.4 | 0.182 | 24.89 | <0.001 | 4.25 | 0.27*** |

| Covariates + STRAIN Total Stressor Severity | 0.42 | 0.206 | 27.35 | <0.001 | 4.17 | 0.12*** |

| GAD-7 | ||||||

| Adj. R2 | Δ R2 | F | p | SE | β | |

| Covariates | 0.12 | 6.84 | <0.001 | 4.25 | - | |

| Covariates + STRAIN Total Stressor Count | 0.23 | 0.109 | 11.64 | <0.001 | 3.98 | 0.17*** |

| Covariates + STRAIN Total Stressor Severity | 0.24 | 0.121 | 12.39 | <0.001 | 3.94 | 0.08*** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).