Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

03 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database and Study Design

2.2. Pathological Data and Study Groups

2.3. Statistical Analysis

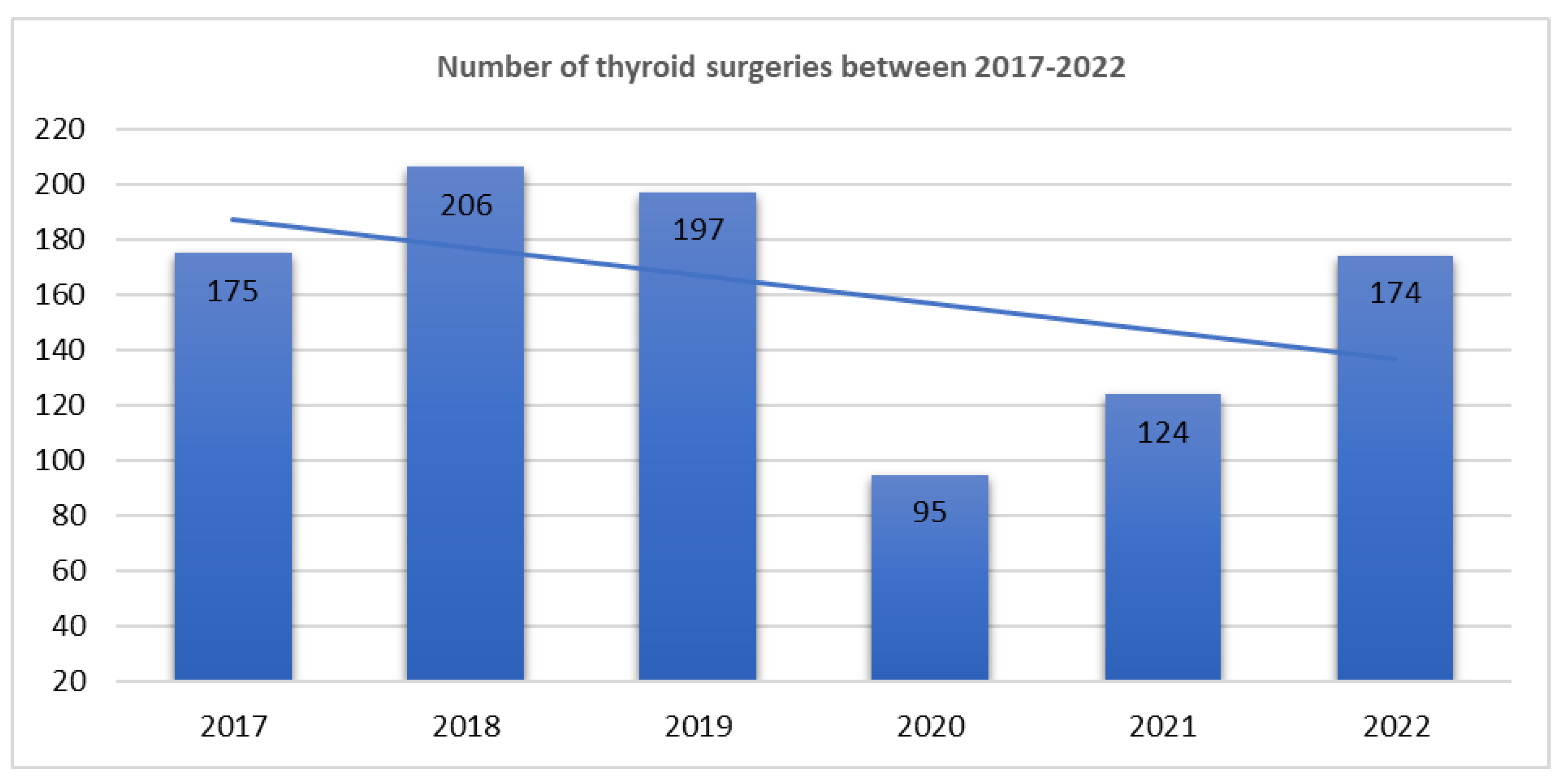

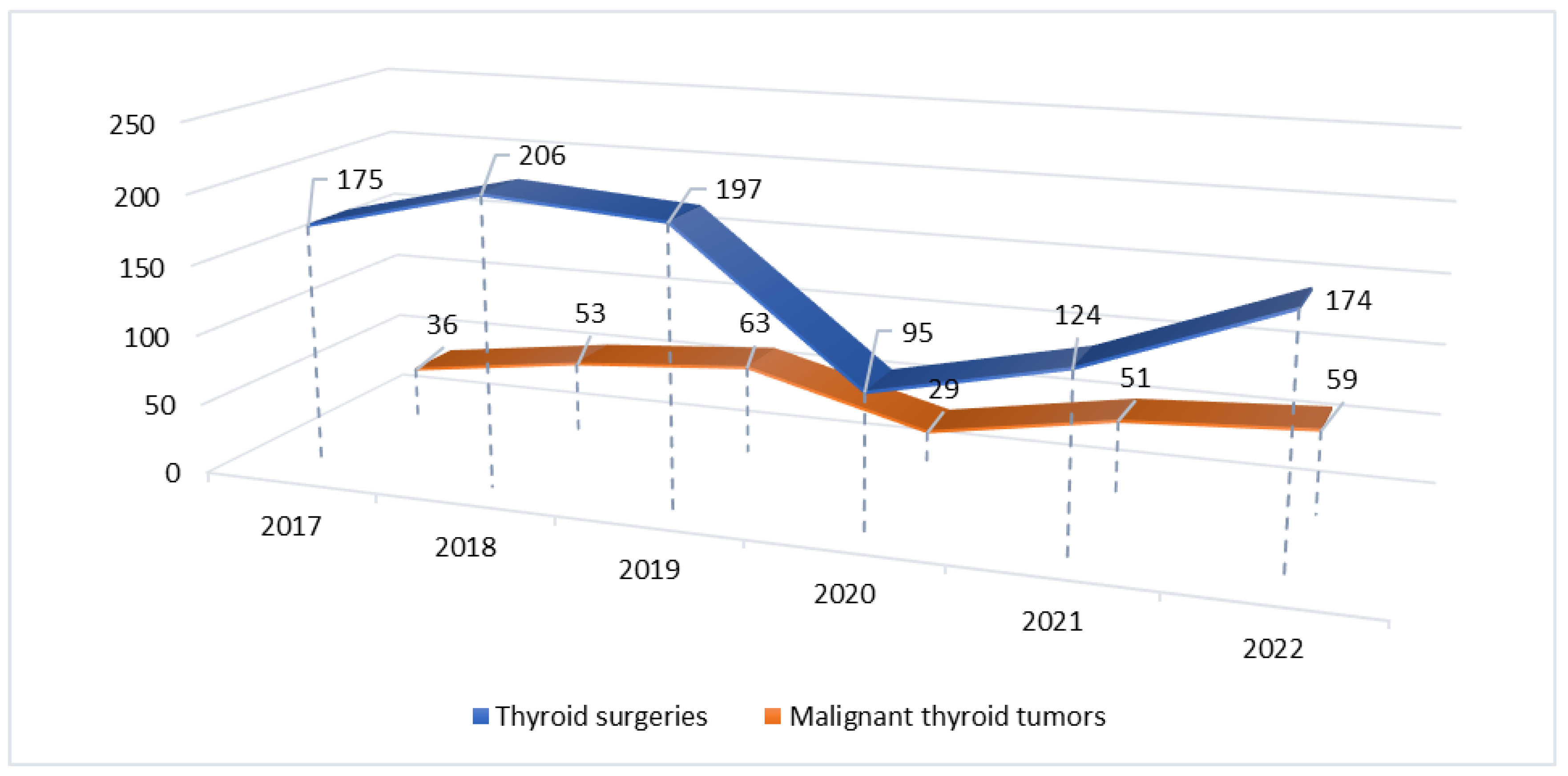

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

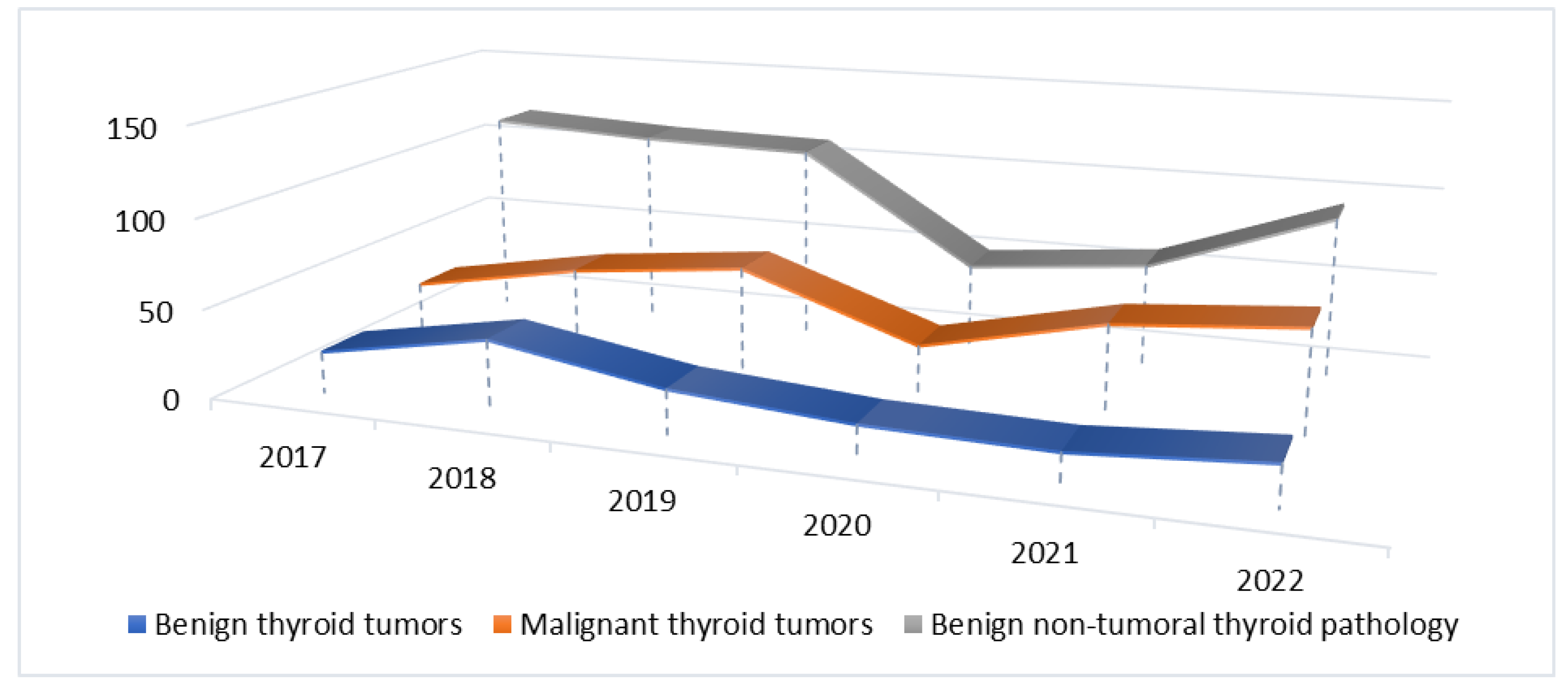

3.2.1. Benign Non-Tumoral Pathology Group

3.2.2. Benign Thyroid Tumors Group

3.2.3. Malignant Thyroid Tumors Group

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflict of Interest

References

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomedica 2020, 91. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Wei, F.; Hu, L.; Wen, L.; Chen, K. Epidemiology and Clinical Characteristics of COVID-19. Arch Iran Med 2020, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradesh, U.; Pandit, P.; Dayal, D.; Pashu, U.; Vigyan, C.; Evam, V.; Pradesh, U.; Zoonosis, S. De; Pereira, S.; Pereira, D.; et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 – COVID-19 Kuldeep Dhama, Preprints (Basel) 2020.

- WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic, World Health Organization (WHO).

- Darvishi, M.; Nazer, M.R.; Shahali, H.; Nouri, M. Association of Thyroid Dysfunction and COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lui, D.T.W.; Tsoi, K.H.; Lee, C.H.; Cheung, C.Y.Y.; Fong, C.H.Y.; Lee, A.C.H.; Tam, A.R.; Pang, P.; Ho, T.Y.; Law, C.Y.; et al. A Prospective Follow-up on Thyroid Function, Thyroid Autoimmunity and Long COVID among 250 COVID-19 Survivors. Endocrine 2023, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoo, B.; Tan, T.; Clarke, S.A.; Mills, E.G.; Patel, B.; Modi, M.; Phylactou, M.; Eng, P.C.; Thurston, L.; Alexander, E.C.; et al. Thyroid Function Before, During, and after COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2021, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duntas, L.H.; Jonklaas, J. COVID-19 and Thyroid Diseases: A Bidirectional Impact. J Endocr Soc 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scappaticcio, L.; Pitoia, F.; Esposito, K.; Piccardo, A.; Trimboli, P. Impact of COVID-19 on the Thyroid Gland: An Update. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguib, R. Potential Relationships between COVID-19 and the Thyroid Gland: An Update. Journal of International Medical Research 2022, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, A.K.; Alzahrani, A.S. Sars-Cov-2: Emerging Role in the Pathogenesis of Various Thyroid Diseases. J Inflamm Res 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitahara, C.M.; Schneider, A.B. Epidemiology of Thyroid Cancer. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention 2022, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhao, X.; Sun, J.; Cheng, C.; Yin, C.; Bai, R. The Epidemic of Thyroid Cancer in China: Current Trends and Future Prediction. Front Oncol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashorobi, D.; Lopez, P.P. Cancer, Follicular Thyroid; 2020.

- Juan Rosai, R.Y.O.G.K.R.V.L. WHO Classification of Tumours of Endocrine Organs; 2017;

- Umakanthan, S.; Sahu, P.; Ranade, A.V.; Bukelo, M.M.; Rao, J.S.; Abrahao-Machado, L.F.; Dahal, S.; Kumar, H.; Kv, D. Origin, Transmission, Diagnosis and Management of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Postgrad Med J 2020, 96. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correction to Lancet Infect Dis 2020; Published Online March 23. Https://Doi.Org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30162 (The Lancet Infectious Diseases, (S1473309920301626), (10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30162-6)). Lancet Infect Dis 2020, 20. [CrossRef]

- Pujolar, G.; Oliver-Anglès, A.; Vargas, I.; Vázquez, M.L. Changes in Access to Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.N.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, F.; Pender, M.; Wang, N.; Yan, F.; Ying, X.H.; Tang, S.L.; Fu, C.W. Reduction in Healthcare Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. BMJ Glob Health 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsioufis, K.; Chrysohoou, C.; Kariori, M.; Leontsinis, I.; Dalakouras, I.; Papanikolaou, A.; Charalambus, G.; Sambatakou, H.; Siasos, G.; Panagiotakos, D.; et al. The Mystery of “Missing” Visits in an Emergency Cardiology Department, in the Era of COVID-19.; a Time-Series Analysis in a Tertiary Greek General Hospital. Clinical Research in Cardiology 2020, 109. [CrossRef]

- Diaz, A.; Sarac, B.A.; Schoenbrunner, A.R.; Janis, J.E.; Pawlik, T.M. Elective Surgery in the Time of COVID-19. Am J Surg 2020, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halley, M.C.; Stanley, T.; Maturi, J.; Goldenberg, A.J.; Bernstein, J.A.; Wheeler, M.T.; Tabor, H.K. “It Seems like COVID-19 Now Is the Only Disease Present on Earth”: Living with a Rare or Undiagnosed Disease during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Genetics in Medicine 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karavadra, B.; Stockl, A.; Prosser-Snelling, E.; Simpson, P.; Morris, E. Women’s Perceptions of COVID-19 and Their Healthcare Experiences: A Qualitative Thematic Analysis of a National Survey of Pregnant Women in the United Kingdom. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailemariam, S.; Agegnehu, W.; Derese, M. Exploring COVID-19 Related Factors Influencing Antenatal Care Services Uptake: A Qualitative Study among Women in a Rural Community in Southwest Ethiopia. J Prim Care Community Health 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, A.W.; Billany, J.C.T.; Adam, R.; Martin, L.; Tobin, R.; Bagdai, S.; Galvin, N.; Farr, I.; Allain, A.; Davies, L.; et al. Rapid Implementation of Virtual Clinics Due to COVID-19: Report and Early Evaluation of a Quality Improvement Initiative. BMJ Open Qual 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smulever, A.; Abelleira, E.; Bueno, F.; Pitoia, F. Thyroid Cancer in the Era of COVID-19. Endocrine 2020, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popa, O.; Barna, R.A.; Borlea, A.; Cornianu, M.; Dema, A.; Stoian, D. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Thyroid Nodular Disease: A Retrospective Study in a Single Center in the Western Part of Romania. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feier, C.V.I.; Muntean, C.; Faur, A.M.; Blidari, A.; Contes, O.E.; Streinu, D.R.; Olariu, S. The Changing Landscape of Thyroid Surgery during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Four-Year Analysis in a University Hospital in Romania. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Min, E.; Hwang, Y.M.; Choi, Y.S.; Yi, J.W. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Thyroid Surgery in a University Hospital in South Korea. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Tian, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhu, J.; Wei, T.; Lei, J. Potential Interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and Thyroid: A Review. Endocrinology (United States) 2021, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarzadeh, A.; Nemati, M.; Jafarzadeh, S.; Nozari, P.; Mortazavi, S.M.J. Thyroid Dysfunction Following Vaccination with COVID-19 Vaccines: A Basic Review of the Preliminary Evidence. J Endocrinol Invest 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, M.M.; El-Zawawy, H.T.; Ahmed, S.M.; Aly Abdelhamid, M. Thyroid Disease and Covid-19 Infection: Case Series. Clin Case Rep 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeClair, K.; Bell, K.J.L.; Furuya-Kanamori, L.; Doi, S.A.; Francis, D.O.; Davies, L. Evaluation of Gender Inequity in Thyroid Cancer Diagnosis. JAMA Intern Med 2021, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moleti, M.; Sturniolo, G.; Di Mauro, M.; Russo, M.; Vermiglio, F. Female Reproductive Factors and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Ros, R.; Rinaldi, S.; Biessy, C.; Tjønneland, A.; Halkjær, J.; Fournier, A.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Mesrine, S.; Tikk, K.; Fortner, R.T.; et al. Reproductive and Menstrual Factors and Risk of Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma: The EPIC Study. Int J Cancer 2015, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbari, R.; Zhang, L.; Kebebew, E. Thyroid Cancer Gender Disparity. Future Oncology 2010, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, E.; De, P.; Nuttall, R. BMI, Diet and Female Reproductive Factors as Risks for Thyroid Cancer: A Systematic Review. PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haymart, M.R. Understanding the Relationship Between Age and Thyroid Cancer. Oncologist 2009, 14, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pathology group | 2017-2019 n (%) |

2020-2022 n (%) |

P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benign non-tumoral thyroid lesions | 339 (58.6) | 200 (50.8) | 0.017 |

| Benign thyroid tumors | 87 (15.1) | 54 (13.8) | 0.579 |

| Malignant thyroid tumors | 152 (26.3) | 139 (35.4) | 0.002 |

| Total | 578 (59.5%) | 393 (40.5%) |

|

Pathology group |

2017-2019 | 2020-2022 | p | ||||||||

|

Average age (years) |

W/ M ratio | Average age for men (years) | Average age for women (years) | Average age (years) | W/M ratio | Average age for men (years) | Average age for women (years) | Average age | Average age for men (years) | Average age for women (years) | |

| Benign non-tumoral thyroid pathology | 53.59 |

9.2/1 |

54.43 |

53.48 | 53.67 |

7.3/1 |

60.83 |

52.69 | 0.552 | 0.002 | 0.556 |

| Benign thyroid tumors | 49.73 |

7.7/1 |

50.90 |

49.58 | 51.90 |

6.8/1 |

51.68 |

53.42 | 0.363 | 0.694 | 0.419 |

| Malignant thyroid tumors | 50.96 |

4.6/1 |

54.64 |

50.10 | 49.57 |

5.3/1 |

48.47 |

48.71 | 0.356 | 0.186 | 0.542 |

| Benign, non-tumoral thyroid lesions | 2017-2019 N (%) |

2020-2022 N (%) |

P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nodular goiter | 268 (79) | 169 (84.5) | 0.139 |

| Diffuse goiter | 13 (3.9) | 2 (1) | 0.060 |

| Basedow-Graves’ disease | 24 (7.1) | 11 (5.5) | 0.588 |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis | 27 (7.9) | 15 (7.5) | 0.990 |

| Cysts | 5 (1.5) | 2 (1) | 0.990 |

| Subacute thyroiditis | 1 (0.3) | 0 | - |

| Thyroid tuberculosis | 1 (0.3) | 0 | - |

| Thyroid abscess | 0 | 1 (0.5) | - |

| Total | 339 (56.8) | 200 (50.8) | 0.017 |

| Benign thyroid tumors | 2017-2019 N (%) |

2020-2022 N (%) |

P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Follicular adenoma | 46 (52.9) | 22 (40.7) | 0.170 |

| Hürthle cell adenoma | 13 (14.9) | 7 (12.9) | 0.808 |

| Hyalinizing trabecular tumor | 0 | 1 (2) | - |

| Other encapsulated follicular-patterned thyroid tumors (non-invasive) | 28 (32.2) | 24 (44.4) | 0.154 |

| Thyroid tumor of uncertain malignant potential (TT-UMP) | 9 (32.2) | 10 (41.6) | 0.151 |

| Noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary- like nuclear features (NIFTP) | 19 (67.8) | 14 (58.4) | 0.782 |

| Total | 87 (15.1) | 54 (13.8) | 0.579 |

| Malignant thyroid tumors | 2017-2019 N (%) |

2020-2022 N (%) |

P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Papillary thyroid carcinoma | 118 (77.6) | 124 (89.2) | 0.011 |

| Follicular thyroid carcinoma | 1 (0.80) | 0 | - |

| Hürthle cell carcinoma | 0 | 2 (1.4) | - |

| Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma | 8 (5.2) | 5 (3.6) | 0.577 |

| Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma | 2 (1.3) | 0 | - |

| Medullary thyroid carcinoma | 15 (9.9) | 4 (2.9) | 0.017 |

| Metastasis | 3 (1.9) | 1 (0.7) | 0.623 |

| Other type (limphoma, angiosarcoma, plasmocitoma) | 5 (3.3) | 3 (2.2) | 0.725 |

| Total | 152 (26.3) | 139 (35.4) | 0.002 |

| Papillary thyroid carcinoma | 2017-2019 N (%) |

2020-2022 N (%) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional | 61 (51.8) | 51 (41.2) | 0.121 |

| Follicular variant | 18 (15.3) | 28 (22.7) | 0.189 |

| Papillary microcarcinoma | 23 (19.5) | 26 (20.9) | 0.873 |

| Encapsulated variant | 0 | 1 (0.8) | - |

| Oncocytic variant | 0 | 2 (1.6) | - |

| Warthin-like variant | 3 (2.5) | 6 (4.8) | 0.500 |

| Tall cell variant | 7 (5.9) | 6 (4.8) | 0.780 |

| Hobnail variant | 3 (2.5) | 2 (1.6) | 0.677 |

| Solid- trabecular variant | 3 (2.5) | 0 | - |

| Diffuse sclerosing variant | 0 | 2 (1.6) | - |

| Total | 118 | 124 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).