1. Introduction

Although there are worldwide initiatives aimed at achieving Sustainable Development Goal 6 — access to safe drinking water for everyone — in 2020, more than two billion people did not have safely managed drinking water, and 2.4 billion resided in countries facing water stress [

1]. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, millions continue encountering water-related challenges primarily due to fluctuating and unpredictable climate conditions, growing populations, and heightened agricultural demand [

2]. Despite attempts to address water-related problems, effective solutions remain elusive, posing significant threats to human health and development.

Water insecurity – the absence or lack of water access, quality, and affect [

3]- is concerned with excess and scarcity and examines sociocultural factors, such as infrastructure, environment, and management, that underlie water resources [

4]. Evidence suggests that water insecurity might impact human health and development through different domains, including nutritional, psychosocial, and physical health [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Thus, water-insecure households are more likely to be economically vulnerable, food insecure, and experience poor health outcomes, including higher levels of depression, among others [

11,

12]. Moreover, households lacking water security may experience decreased agricultural output and economic activities [

13]. However, diverse experiences with water insecurity might compel households to adopt coping strategies to secure sufficient water for daily life [

14], p. 13. Coping strategies - household and individual responses to unreliable water supplies [

15] - are immediate and temporary behaviors that households develop to cope with challenges around water as a resource [

16]. Coping strategies are meant to achieve positive outcomes, such as sufficient water for household use, but sometimes entail tradeoffs [

17] with negative consequences [

11]. For instance, water acquisition strategies like sleep interruption to get to the water point earlier than others, borrowing water for cooking or drinking from neighbors, and withstanding long queues at the water collection points may lead to physical and psychosocial impacts on women [

11,

18,

19].

Households may apply multiple coping strategies to mitigate water insecurity [

20,

21,

22,

23]. For example, individual and household behavioral responses might include drilling wells, storing water, and collecting water from alternative sources [

15]. In a recent study to characterize and quantify coping strategies, Collins et al. identified water borrowing as the most practiced strategy, especially among people collecting water from non-primary sources [

16].

Despite the extensive literature on coping strategies for household water insecurity, strategies employed by displaced individuals or households have not been significantly investigated. Additionally, there is limited knowledge of how personal values, beliefs, and norms may influence these strategies. Specifically, the theoretical frameworks informing the choice of these strategies remain largely underexplored.

The Value, Belief, and Norm Theory (VBN) [

24] is a plausible theoretical framework that might help to understand the behaviors of water system users and the strategies they employ to navigate water challenges [

25]. As a theoretical framework, VBN can incorporate environmentally related behaviors [

26] and is thus a viable theory for understanding coping strategies in water-stressed households. Further, since individual behaviors and coping strategies are dynamic and vary in context [

15], the VBN’s emphasis on human-water interactions [

27] makes it suitable for understanding household and individual water insecurity dynamics.

This study, therefore, sought to a) explore the most used household water coping strategies among households affected by development-induced displacement and b) explore how values, beliefs, and norms might influence the choices of these coping strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

Data for this study were collected from the people affected or displaced by the Thwake Multipurpose Dam construction in Makueni County, Kenya. The Thwake Multipurpose Dam is one of Kenya’s Vision 2030 projects and aims to reduce water scarcity and increase irrigation, energy production, and support for the affected residents of Makueni County. Upon its completion, the Thwake Multipurpose Dam will be one of the largest water infrastructures in Kenya, occupying about 10,000 acres of land. It is estimated that approximately 5,000 people were displaced to pave the way for the dam construction.

2.2. Participant Recruitment

We purposefully recruited 65 participants (20 men and 45 women) affected by the Thwake Dam construction in Makueni County. Participants were eligible if they had recently relocated from the dam construction area, had been given notice to vacate the land, or were in the downstream regions affected by the dam construction. Only adults 18 years and older, residents of the Thwake region for more than one year, and knowledgeable about household water needs were allowed to participate in the study.

2.3. Data Collection

Two qualitative researchers fluent in the local language conducted interviews between December 2018 and June 2019 using the in-depth interview (IDI) technique. In-depth interviewing is a qualitative data collection method that allows extended conversations between a researcher and a participant. An IDI enables the researcher and participants to explore sensitive topics, including knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions on various issues [

28]. The interviews were audio-recorded and lasted for approximately one hour. The interviews explored themes related to experiences of water insecurity, including water acquisition practices and coping strategies. In addition, the interviews asked about people’s perceptions and thoughts regarding their values, beliefs, and norms, and how these influenced their choices, practices, and behaviors as they pertain to household water insecurity.

2.4. Data Analysis

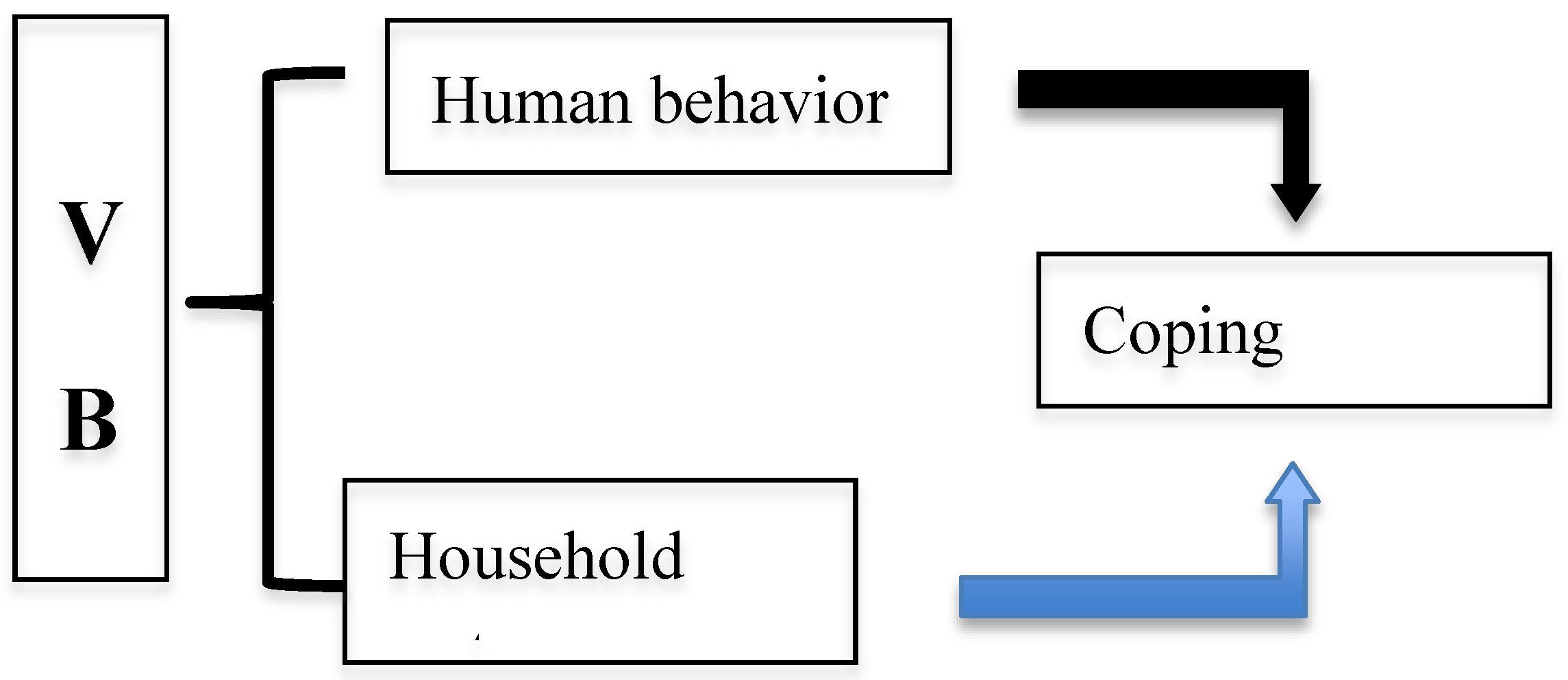

Transcription and translation: Initial interviews were transcribed verbatim into Kamba and translated to English by trained qualitative transcribers. The quality of the transcription and translation was verified by an independent research assistant who listened and read through the first ten audio recordings and transcripts. This process identified emergent themes to develop a data-coding framework (tree). An initial 50 codes were generated and imported into Atlas. Ti. (version 8.2.1(550)) software for qualitative data analysis. A theoretical framework (

Figure 1) was developed using these codes to guide the data analysis process. The rest of the interviews were then coded and analyzed for emerging themes.

Coding procedure: Each transcript was coded for coping strategies and information on values, beliefs, and norms. The coping strategies were linked to both storage mechanisms and elements of VBN.

Ethical Consideration: Northwestern University (STU00208788) and Amref Health Kenya (P574/2019) provided ethical approval. Participants were reimbursed KES 500 (US$5) for each visit to the interview location.

3. Results

Water storage in plastic containers (jerry cans and barrels) was the primary coping strategy (155 mentions) among households in the Makueni area. It greatly influenced other household water practices, including acquisition, use, and treatment. For instance, water treatment appeared to occur only where water storage was present. Similarly, collecting rainwater (mentioned 61 times) and borrowing (mentioned 53 times) depended on the households’ water storage capacity.

3.1. The Influence of Household Water Storage on Other Coping Strategies

Although most participants stored water in different places in their households, all 65 participants confirmed having between two and twenty plastic water containers. Thus, plastic jerry cans were the most common mode of water storage among households in the Thwake region.

“If I have many water containers, then I can store water well, but when you don’t have them, I fear water will run out very fast, and I will keep fetching water from the river. With these containers, I am sure I can have some water for about a month after the rains subside.” Female, 33 Years

3.1.2. Changes in Seasonality and Water Storage Behaviors

Water storage practices varied with the seasons but remained consistent. All participants indicated that acquiring water was a daily or regular task, necessitating a careful storage strategy. However, attitudes toward household water storage shifted according to the season. In rainy periods, the majority focused on collecting rainwater, influenced by its accessibility and perceived quality, including taste and texture. Participants noted that the volume of water stored was contingent on how many storage containers were available at home.

“You know, usually we store rainwater in the containers I mentioned, the super drums and the jerry cans. So, when it is a dry season, we get water from the storage and use it for drinking. As for cooking, among other house activities, we go to the river or other water sources available at that time.” PID 039, Female, 30 Years

3.1.3. Household Water Rationing and Storage Practices and

When asked about water storage and consumption, some participants (n=20) indicated that their household water activities—such as laundry, cooking, cleaning, bathing, and drinking—dictated the volume of water stored and its distribution across various tasks. Drinking and cooking water were reported to have the highest priority. In contrast, stored water for agricultural purposes, including livestock care and crop production, was considered a lower priority and received the least allocation. Most participants agreed that, even though they faced water scarcity, they avoided using stored water for economic activities.

“I store drinking water in a port. I keep drinking water for emergencies during the dry season in those jerry cans, water for cooking in buckets, and washing clothes in other containers. That is how I store my water.” PID 030, Female, 27 Years.

3.1.4. Household Water Acquisition and Storage Practices

This study reveals that the availability of water storage facilities in households influences the frequency and volume of water collected. Participants reported that households with multiple storage containers made fewer trips to the water source and could go longer without worrying about water supply. Conversely, the participants observed that households and women lacking sufficient water storage facilities spent more time between water-fetching trips, often requiring their children to collect water almost daily.

“If I have many water containers, then I can store it well, but when you don’t have them, your water will run out very fast, and you will keep on fetching water from the river even when rain has gone on for a month, your water from the river has run out. I learned that one should have many containers for storing water” PID 006, Female, 33 Years.

3.1.5. Water Source and Storage Practices

Rainwater storage was frequently prioritized. Nonetheless, storage focused on water from all sources, despite rivers and surface water receiving less emphasis when alternatives existed.

“This is now a picture of how we store water. That is the super drum I was telling you about. We usually store water there, whether it is rainwater or any that we get from the various water points. The water pot, though, is used to store drinking water.” PID 015, Female, 40 Years

3.1.6. Water Borrowing and Storage Practices

Interestingly, households with fewer containers appeared more susceptible and turned to alternative methods like borrowing. In the interviews, borrowing was ranked as one of the most frequently cited coping strategies, and 28 participants referenced it 53 times. The shortage of storage containers also seemed to make households more vulnerable to other issues, such as insufficient cooking and drinking water, leading them to adopt unconventional methods like borrowing.

“I lacked water until I borrowed drinking water from my neighbor because I had not boiled my drinking water, and she gave me even more water for cooking because I had fewer containers for storing water.” PID 32, Female, 39 Years

3.1.7. Waking Up Early, Lining Up at Water Points and Storage Practices

When it comes to water acquisition, many people would wake up early to reach the nearest water point (borehole or tap) before it got crowded. This practice was often shaped by how many storage containers each household could afford.

“Yes, like in the past, before those boreholes were established, we had a huge problem because the rivers were drying up. Once they had dried up, it forced us to look for water for about 3 km, meaning we had to wake up very early in the morning to go and get water.”PID 021, Male, 36 Years

3.2. Values, Norms, and Beliefs and Choices of Water Insecurity Coping Strategies

This study explored individuals’ experiences with water storage and various coping strategies for household water insecurity, aiming to uncover how values, beliefs, and societal norms shaped these practices. The results indicate that personal values, beliefs, and dominant societal norms influenced most water coping strategies and practices. For instance, gender norms were viewed as significant in how households acquire and use water. Participants’ societal beliefs, such as religious views, also informed water quality and treatment decisions. For example, rainwater was often regarded as a divine blessing, leading to the perception that it did not have quality concerns. However, when contemplating water treatment, personal values regarding attributes like texture and odor emerged as important factors.

3.2.1. Water Storage and Beliefs

Some participants felt that water was inherently pure and divinely provided. Consequently, they viewed water treatment as unnecessary. Additionally, some reported that conducting a household blessing ritual could enhance water safety for drinking and other domestic purposes. In cases where these rituals were observed, the water was deemed safe and suitable for human consumption after the rituals were completed.

“After the water has been blessed, we pour it into the pot, and anyone who wants drinking water can use it.” PID 002, Female, 48 Years.

The belief that water is already blessed was similar in the type of water source. Some participants believed that God blesses water from the source and that water is naturally safe.

“R: We drink it directly from the river with the notion that God had blessed the water. Sometimes we get stomach upset, headache, you can diarrhea, and I think such problems come up because of water.” PID 006, Female, 33 Years

“R: When it rains, dirty water can flow into the well or borehole, but God has already blessed water. I have never witnessed anybody falling sick because the person used that water. God had already blessed water; even if you drink dirty water, nothing will happen to you. I believe water comes from God, so whether they treat it or not, it will be safe from any disease.” PID 32, Female, 39 Years.

Belief in supernatural forces influenced how individuals responded to various coping strategies. Some participants expressed a tendency to refrain from taking action, opting instead to entrust their fate to God. This was particularly evident in situations of property damage caused by flooding. Such natural disasters were regarded as sacred and deemed to require no human intervention, shaping the way people responded to challenging circumstances. Interviewer: Okay, what do you do when your farm is flooded?

“Respondent: You know there is nothing much I can do; I leave it all to God. If this happens after planting, we leave it in God’s hands.” PID 023, Female, 50 Years.

3.2.2. Values and Norms

Gender norms were recognized as linked to roles in water acquisition. It was perceived that acquiring and using water was mainly a woman’s duty. This classification was also noticeable among children, with young girls being viewed as more accountable for water-related tasks than boys.

“Because that is her work, fetching water as the woman … And more so when carrying the Jerry cans with my hands, it is better for women because they can use their heads or even back to hold water. They were created that way.”PID 005, Male, 34 Years

The study found that gender norms placed considerable responsibilities on women regarding water usage, especially in agriculture. Many participants believed it was primarily a woman’s role to perform agricultural activities that required water.

“R: anything to do with planting and irrigation of vegetables is done by the woman of the house.” PID 044, Male, 42 Years

4. Discussion

Our findings show that in the Makueni region, water storage and treatment serve as the primary coping strategies and significantly affect other strategies, such as acquisition, borrowing, usage, and treatment methods in western Kenya. For instance, the availability of water storage facilities greatly impacts the timing and quantity of water collected and utilized by households. Participants with sufficient water storage made fewer trips for water and spent less time on acquisition compared to those lacking storage. Additionally, most participants considered water storage crucial for food preparation; those with adequate facilities reported no challenges in cooking or meal planning. Furthermore, households with inadequate water storage systems reportedly encountered unexpected water-related costs, such as sourcing alternative water transport and spending more on water from vendors. The research also revealed that while families utilized various coping strategies to address water issues, these approaches were influenced by personal values, beliefs, and societal norms.

In sub-Saharan Africa, including Kenya, numerous water resources are either unimproved or unsafe. [

11], and many people are forced to leave their homes to find water, wasting valuable time that could be used for economic and other productive activities [

29]. Participants noted that they used various coping strategies to address these challenges. This study indicates that practices such as water acquisition are associated with household water storage effectiveness and are influenced by individual values, beliefs, and social norms.

These results illustrate that obtaining water is a difficult task for households with limited storage options, potentially exposing individuals to additional health risks. The outcomes support observations made by other researchers about the physical health impacts associated with certain coping strategies [

23]. Further, the findings expound on the negative influence of societal norms that assign more water acquisition responsibilities to women. In addition, the study extends the argument regarding the gendered aspects of water acquisition and the perceived role of women as culturally suitable and, therefore, responsible for hauling water for the family [

30]. This study further supports other findings documenting that women and children bear the burden of water acquisition and the associated consequences [

31]. Other scholars have noted that women involved in water acquisition are more likely to suffer physical injuries, including spinal injuries, most often in the cervical region, and poor maternal health outcomes [

7,

32,

33]. These effects were more pronounced for young women, as their injuries made it harder to find marriage partners [

34]. Scholars highlight that individuals affected or displaced by development projects, like dam construction, may experience weakened social ties, reduced family support, and strained familial relationships, which can negatively impact their psychological well-being [

35].

Our study reveals that household water storage practices affected income and spending behaviors. Households lacking storage facilities incurred higher water acquisition costs, spent more time fetching water—especially during dry seasons—engaged with water vendors more, and directed money to household water needs. Thus, water storage directly impacted household income by reducing the time allocated for economic activity and opportunity costs. These findings support the growing literature on household water insecurity and household income [

12,

36,

37,

38]. Other studies have demonstrated that financial burdens are experienced when household members spend time and money to acquire water [

39]. Thus, water acquisition robs families of valuable productive times that could be converted into economic and recreational time [

40].

In addition, we found that storage capabilities impacted other acquisition practices and compelled individuals to have erratic sleep patterns. Worsened by displacement and relocation challenges, individuals would adjust their schedules to wake up early or stay up late in the evening to fetch water, thus depriving them of sleep and leisure time [

41]. Cumulatively, this could significantly improve women’s health outcomes, such as reduced stress, anxiety, and depression levels.

In this study, societal norms around gender roles further influenced household water acquisition strategies, expanding on the literature on water and gender [

30,

41]. Research on gendered dynamics in water acquisition suggests that women’s responsibilities as water carriers are tied to their reproductive roles, which hinders their involvement and empowerment in water-related matters [

42]. While community wells and water points provide secure environments for social responsibilities and showcase women’s agency in building social connections, Strang notes that advancements in technology—specifically water pumps and piped water—have worsened women’s disenfranchisement, ultimately transferring control of water resources to the men who design these infrastructures (Strang 2004).

While most participants viewed water quality as a significant issue, this study found that water treatment primarily relied on water storage to address water quality. Moreover, treatment practices were influenced by personal values and beliefs, often leading to a reduction or prevention of water treatment. These observations may clarify why water treatment remains extremely low in many developing countries [

43]. For instance, while rainwater was predominantly collected, it was seldom treated due to the belief that it was already blessed by God and naturally clean. Some individuals preferred to have their water undergo blessings through water rituals as a water treatment method, after which they reported being comfortable storing their water for extended periods. This viewpoint might clarify other research outcomes that show a notable amount of E. coli in collected rainwater at the household level, especially in cases where no treatment occurred beforehand [

44]. Meera and Ahammed have pointed out that various factors, such as the roof’s age, its material, and the type of rainfall, impact the quality of harvested rainwater [

45]. However, this study argues that personal values and societal beliefs significantly affect rainwater treatment practices.

5. Conclusions

As water security concerns rise and climate change increases vulnerability, VBN may play a vital role in understanding cultural complexities and dynamic human-water interactions. This paper demonstrates that the Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) theoretical framework can improve our understanding of how households cope with water insecurity and interact with water. Therefore, it is essential to understand people’s values, beliefs, and norms to accurately predict behavioral changes in water-insecure households. Therefore, the VBN framework could provide valuable insights for creating a water coping strategies index, especially for the displaced population. However, incorporating ethnographic methods during data collection is essential to capture individual beliefs, values, and norms.

Funding

This study was funded through the Northwestern Graduate School Fellowship and the British Institute in East Africa (BIEA) Small Thematic Research Grant.

Data Availability Statement

Data for this study will be available upon request.

Acknowledgments

This research’s greatest acknowledgment is to the Thwake Dam community members who volunteered to participate in it and shared their experiences.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- United Nations, “SDG Report,” The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2017. Accessed: Sep. 29, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2017/overview/.

- S. Marshall, “The Water Crisis in Kenya: Causes, Effects and Solutions,” Global Majority, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 31–45, 2011.

- W. Jepson, “Measuring ‘no-win’ waterscapes: Experience-based scales and classification approaches to assess household water security in colonias on the US–Mexico border,” Geoforum, vol. 51, pp. 107–120, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Wutich et al., “Advancing methods for research on household water insecurity: Studying entitlements and capabilities, socio-cultural dynamics, and political processes, institutions and governance,” Water Security, vol. 2, pp. 1–10, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Aihara, S. Shrestha, and J. Sharma, “Household water insecurity, depression and quality of life among postnatal women living in urban Nepal,” Journal of Water and Health, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 317–324, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Brewis, N. Choudhary, and A. Wutich, “Household water insecurity may influence common mental disorders directly and indirectly through multiple pathways: Evidence from Haiti,” Social Science & Medicine, vol. 238, p. 112520, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. R. Krumdieck et al., “Household water insecurity is associated with a range of negative consequences among pregnant Kenyan women of mixed HIV status,” J Water Health, vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 1028–1031, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Miller et al., “Household Water and Food Insecurity Are Positively Associated with Poor Mental and Physical Health among Adults Living with HIV in Western Kenya,” The Journal of Nutrition, vol. 151, no. 6, pp. 1656–1664, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Miller et al., “Water Security and Nutrition: Current Knowledge and Research Opportunities,” Adv Nutr, vol. 12, no. 6, pp. 2525–2539, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Y. Rosinger and S. L. Young, “The toll of household water insecurity on health and human biology: Current understandings and future directions,” WIREs Water, vol. 7, no. 6, p. e1468, 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. G. J. Stevenson, A. Ambelu, B. A. Caruso, Y. Tesfaye, and M. C. Freeman, “Community Water Improvement, Household Water Insecurity, and Women’s Psychological Distress: An Intervention and Control Study in Ethiopia,” PLOS ONE, vol. 11, no. 4, p. e0153432, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Stoler et al., “Cash water expenditures are associated with household water insecurity, food insecurity, and perceived stress in study sites across 20 low- and middle-income countries,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 716, p. 135881, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Hadley and A. Wutich, “Experience-based Measures of Food and Water Security: Biocultural Approaches to Grounded Measures of Insecurity,” Human Organization, vol. 68, no. 4, pp. 451–460, Dec. 2009. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Donelson, S. Salinas, P. L. Munday, and L. N. S. Shama, “Transgenerational plasticity and climate change experiments: Where do we go from here?,” Global Change Biology, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 13–34, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Majuru, M. Suhrcke, and P. R. Hunter, “How Do Households Respond to Unreliable Water Supplies? A Systematic Review,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 13, no. 12, p. 1222, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Collins et al., “Toward a more systematic understanding of water insecurity coping strategies: insights from 11 global sites,” BMJ Glob Health, vol. 9, no. 5, p. e013754, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Eakin et al., “Adapting to risk and perpetuating poverty: Households strategies for managing flood risk and water scarcity in Mexico City,” Environmental Science & Policy, vol. 66, pp. 324–333, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Collins et al., “‘I know how stressful it is to lack water!’ Exploring the lived experiences of household water insecurity among pregnant and postpartum women in western Kenya,” Global Public Health, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 649–662, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. R. Krumdieck et al., “Household water insecurity is associated with a range of negative consequences among pregnant Kenyan women of mixed HIV status,” J Water Health, vol. 14, no. 6, p. 1028, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Achore and E. Bisung, “Coping with water insecurity in urban Ghana: patterns, determinants and consequences,” Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 150–164, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Bisung and S. J. Elliott, “‘It makes us really look inferior to outsiders’: Coping with psychosocial experiences associated with the lack of access to safe water and sanitation,” Can J Public Health, vol. 108, no. 4, pp. e442–e447, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. M. Owuor et al., “The influence of an agricultural intervention on social capital and water insecurity coping strategies: Qualitative evidence from female smallholder farmers living with HIV in western Kenya,” Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 11, p. e32058, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Venkataramanan, S. M. Collins, K. A. Clark, J. Yeam, V. G. Nowakowski, and S. L. Young, “Coping strategies for individual and household-level water insecurity: A systematic review,” WIREs Water, vol. 7, no. 5, p. e1477, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. C. Stern, T. Dietz, T. D. Abel, G. A. Guagnano, and L. Kalof, “A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism,” Human Ecology Review, vol. 6, no. 2, p. 18, 1999.

- J. Hiratsuka, G. Perlaviciute, and L. Steg, “Testing VBN theory in Japan: Relationships between values, beliefs, norms, and acceptability and expected effects of a car pricing policy,” Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, vol. 53, pp. 74–83, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. C. Stern and T. Dietz, “The Value Basis of Environmental Concern,” Journal of Social Issues, vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 65–84, 1994. [CrossRef]

- S. Massuel et al., “Inspiring a Broader Socio-Hydrological Negotiation Approach With Interdisciplinary Field-Based Experience,” Water Resources Research, vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 2510–2522, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Knott, A. H. Rao, K. Summers, and C. Teeger, “Interviews in the social sciences,” Nat Rev Methods Primers, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 1–15, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Pickering and J. Davis, “Freshwater Availability and Water Fetching Distance Affect Child Health in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Environ. Sci. Technol., vol. 46, no. 4, pp. 2391–2397, Feb. 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. Guchhait, S. Chakraborty, R. Mondal, S. Mondal, and Ganguly, “Water and women: A review on gender perspective role,” vol. 9, pp. 4–7, Mar. 2023.

- S. M. Collins et al., “You take the cash meant for beans and you buy water”: The Multi-Faceted Consequences of Water Insecurity for Pregnant and Postpartum Kenyan Women of Mixed HIV Status,” The FASEB Journal, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J.-A. Geere et al., “Carrying water may be a major contributor to disability from musculoskeletal disorders in low income countries: a cross-sectional survey in South Africa, Ghana and Vietnam,” J Glob Health, vol. 8, no. 1, 2018. [CrossRef]

- V. Venkataramanan, J.-A. L. Geere, B. Thomae, J. Stoler, P. R. Hunter, and S. L. Young, “In pursuit of ‘safe’ water: the burden of personal injury from water fetching in 21 low-income and middle-income countries,” BMJ Global Health, vol. 5, no. 10, p. e003328, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Fielmua and D. T. Mwingyine, “Water at the Centre of Poverty Reduction: Targeting Women as a Stepping Stone in the Nadowli District, Ghana,” Ghana Journal of Development Studies, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 46-68–68, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. M. Owuor, D. R. Awuor, E. M. Ngave, and S. L. Young, “‘The people here knew how I used to live, but now I have to start again.’ Lived experiences and expectations of the displaced and non-displaced women affected by the Thwake Multipurpose Dam construction in Makueni County, Kenya,” Social Science & Medicine, p. 116342, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Achore, E. Bisung, and E. D. Kuusaana, “Coping with water insecurity at the household level: A synthesis of qualitative evidence,” Int J Hyg Environ Health, vol. 230, p. 113598, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Brewis et al., “Water sharing, reciprocity, and need: A comparative study of interhousehold water transfers in sub-Saharan Africa,” Economic Anthropology, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 208–221, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Collins et al., “You take the cash meant for beans and you buy water”: The Multi-Faceted Consequences of Water Insecurity for Pregnant and Postpartum Kenyan Women of Mixed HIV Status,” The FASEB Journal, vol. 31, no. 1_supplement, p. 651.4-651.4, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Saladi and F. S. Salehe, “Assessment of water supply and its implications on household income in Kabuku Ndani Ward, Handeni District, Tanzania,” Mar. 2018, Accessed: Apr. 12, 2019. [Online]. Available: http://www.suaire.sua.ac.tz:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/2229.

- E. Bisung and S. J. Elliott, “Improvement in access to safe water, household water insecurity, and time savings: A cross-sectional retrospective study in Kenya,” Social Science and Medicine, vol. 200, pp. 1–8, 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. R. Gambe, “The Gender Dimensions of Water Poverty: Exploring Water Shortages in Chitungwiza,” Journal of Poverty, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 105–122, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- V. Strang, Meaning of Water. New York: BERG, 2004.

- A. Geremew, B. Mengistie, J. Mellor, D. S. Lantagne, E. Alemayehu, and G. Sahilu, “Appropriate household water treatment methods in Ethiopia: household use and associated factors based on 2005, 2011, and 2016 EDHS data,” Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, vol. 23, no. 1, p. 46, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Smiley and H. Hambati, “Impacts of flooding on drinking water access in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: implications for the Sustainable Development Goals,” Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 2019. [CrossRef]

- V. Meera and M. Mansoor Ahammed, “Factors Affecting the Quality of Roof-Harvested Rainwater,” in Urban Ecology, Water Quality and Climate Change, A. K. Sarma, V. P. Singh, R. K. Bhattacharjya, and S. A. Kartha, Eds., in Water Science and Technology Library. , Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018, pp. 195–202. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).