Introduction

According to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, 1.3 billion people suffer from serious disabilities. This is 16% of the world's population, or every sixth of person [

1].

One of the main causes of disability is stroke.

Stroke differs from many other conditions as it occurs suddenly when the blood supply to the brain is occluded or there is a bleed resulting in damage to surrounding brain tissue. It is responsible for a wider range of disabilities than any other condition [

2].

The most recent Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019 stroke burden estimates showed that stroke remains the second leading cause of death and the third leading cause of death and disability combined (as expressed by disability-adjusted life-years lost—DALYs) in the world [

3].

According to the World Stroke Organization (WSO) 2022 global fact sheet, more than 12.2 million new strokes occur each year. Globally, one in four people over 25 years of age will suffer a stroke in their lifetime. There are currently more than 101 million people worldwide who have had a stroke. Six and a half million people die from stroke every year. More than 143 million years of healthy life are lost each year due to stroke-related death and disability [

4].

The incidence of stroke in the Republic of Kazakhstan increases 2.3 times from 189 in 2011 to 433.7 per 100,000 populations in 2020. It can be noted that the dynamics of the mortality rate has relatively decreased. By the way, compared to 2011, in 2020 (78.49) there was a decrease of 15%. In 2011, 92.36 mortality rates per 100 000 per population were registered [

5].

In absolute numbers, more than 40,000 cases of strokes are registered annually in our country, of which only 5,000 people die in the first 10 days and another 5,000 during the first month after the stroke [6, 7].

People who survive a stroke usually have to deal with various functional limitations. These restrictions have a significant impact on the quality of life and the associated social participation in everyday life and also have a physical and emotional impact on the lives of relatives [

8]. Estimates of the prevalence of dysarthria following traumatic brain injury vary from 10% to 60% in different series [9, 10]. Post-stroke dysphagia (a difficulty in swallowing after a stroke) is a common and expensive complication of acute stroke and is associated with increased mortality, morbidity, and institutionalization due in part to aspiration, pneumonia, and malnutrition [

11].

Mental health diagnoses in the first 3 years after a stroke increase the risk of death by more than 10%. In spite of the fact that patients with poststroke depression were younger and had fewer chronic illnesses than nondepressed patients, we found that the mortality risk was still higher in those with poststroke depression and other mental health diagnoses. These data speak to the seriousness of poststroke mental health diagnoses, since the presence of a mental health condition confers as much risk for subsequent mortality as many other cardiovascular risk factors [

12].

Urinary incontinence can affect 40% to 60% of people admitted to hospital after a stroke, with 25% still having problems when discharged from hospital and 15% remaining incontinent after one year [

13].

These limitations have a significant impact on quality of life and accompanying social participation in daily life, as well as having a physical and emotional impact on the lives of loved ones. Return to work (RTW) is a common goal for adults after stroke; however, poststroke disabilities may limit occupational opportunities [

14]. (RTW) is a common goal for adults after stroke; however, post-stroke disability can limit employment opportunities. This problem is a major economic burden for the state. The physical, psychological, social, financial, and economic costs associated with loss of productivity for patients post-stroke are reported to be billions of dollars each year [

15].

Table 1 illustrates comparative data on the size of payments to persons with disabilities from the effects of morbidity in Kazakhstan and the United States.

The profound changes that can accompany stroke may create considerable uncertainty in caring for the affected person and may necessitate changes in lifestyle or behavior patterns of both caregivers and stroke survivors [

17]. Care provided commonly includes: physical, such as assisting with personal hygiene, feeding or mobility, care and assistance with medication; emotional, providing company and listening to worries; or practical, helping with cooking, shopping, cleaning, etc. The amount of time spent caring varies from a few minutes to many hours a week [

2].

The classic caregiver stress framework portrays an image of caregivers who sacrifice their own health to enable disabled relatives to continue to reside in the community. It is easy to imagine how this process could break down, with mentally and physically compromised caregivers eventually providing lower-quality care, perhaps leading over time to abuse or neglect and, ultimately, to negative health outcomes for the care recipient [

18].

Stroke family caregivers report feelings of uncertainty, emotional distress, and the need for training and information [

19]. They are more likely to have depressive symptoms and report fair to poor physical health, higher strain, and are less likely to engage in health promotion activities than noncaregivers [

20].

If the relative carer and family have poor arrangements, caregiving can have a negative impact on health and well-being [

21].

Caregivers need assistance in learning strategies to address their changing needs and prevent the detrimental effects of caregiving over time [22, 23].

Therefore, we conducted a cross-sectional study to assess post-stroke care needs among caregivers.

Purpose of the study: to identify the emerging difficulties of caregivers after discharge from hospital to home and the most common post-stroke patient health deficits encountered by caregivers during home care.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

In order to study the opinions of relatives caring for stroke patients and to identify the difficulties encountered in the process of care at home, a questionnaire was developed and the questions of the questionnaire were tested (validated). The questionnaire contains 24 questions. The questionnaire consists of a passport part and a main block of questions reflecting the peculiarities of care, difficulties and care skills of relatives, and a question assessing the emotional state of the caregiver on a ten-point scale. The structure of the questions was either dichotomous (i.e. yes/no answers) or evaluative on a scale from 1 to 10. The questionnaire was completed in Kazakh and Russian and took approximately 10-15 minutes to complete. The questionnaire was anonymous. In order to maintain confidentiality, no personal information about the individual was collected.

Study Participants

Study participants were recruited by distributing a questionnaire via Google Forms. Home caregivers of stroke survivors (n=205) participated in the study. Of these, 121 were female caregivers and 84 were male caregivers. The average age of the respondents was 50 years.

Participants residing in the East Kazakhstan region (East Kazakhstan Oblast and Abay Oblast) were voluntarily enrolled in this study and informed consent was obtained from each of them. All study participants provided written consent after providing detailed information about the purpose of the study and the confidentiality of personal data. Participants were coded with a unique code. The correspondence between this code and the personal identification information was stored in a file that only the database сustodian had access to. The others had access to the coded (secure) database. Prior to data collection, the study received approval from the Semey Medical University Ethics Committee (Protocol №1, October 22, 2022).

Statistical Analysis

The obtained responses were stored in an automated Google spreadsheet.

For qualitative data: Pearson's chi-square. A value of p<0.05 was taken as statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 20.0 program (IBM Ireland Product Distribution Limited, Ireland). Descriptive statistics such as frequencies (n), mean values (M), medians (Me) and standard deviations (SD) were calculated.

Results

We conducted an analytical study to describe the peculiarities of caring for a relative with stroke and possible difficulties in the process of care. The average length of time after stroke onset is 23.9 months. (IQR=13).

Table 2 provides an overview of the study population detailing its main characteristics. Of the total sample of 205, 121 (59.1%) identified themselves as female and 84 (40.9%) identified themselves as male. Most of the participants were between forty and sixty years old (M=50.57; SD= 13.475). The education level of 37.6% of the respondents had tertiary education, 33.7% had secondary education, 13.7% had incomplete secondary education, 10.2% had primary education, and 4.9% had postgraduate education. The majority of participants indicated themselves as unemployed 48 (23.4%), 38 indicated themselves as civil servants (18.5%), heavy physical laborers and professional athletes accounted for 1%.

Table 3 presents the answers to the questions concerning the availability of disability group and restoration of labor activity. 143 respondents answered that relatives did not restore their labor activity after stroke. This is more than half of the respondents (69.7%), and only 62 (30.2%) of the participants answered that relatives of stroke survivors have returned to their previous jobs. To the question, "Does your relative who had a stroke have a disability group?" 80 participants (39%) answered positively. 105 (51%) answered that they did not. 20 people (10%) abstained from answering. Of the patients who received disability due to stroke, 15 people belong to group 1, 36 to group 2, and 35 to group 3.

Table 4 shows the percentage of stroke sequelae and the specifics of poststroke care direction. Relatives of the caregivers noted that the majority of post-stroke patients have such disorders as motor dysfunction (119).

Speech impairment as a consequence of stroke was 39%. In 18.5% of patients there were complications such as swallowing difficulties. Sensory impairment in 44% and mental dysfunction in 38.5%. Urinary incontinence and stool disturbance in 11% of stroke survivors.

In the answers to the question studying the specifics of care directions in the post-stroke period, it can be seen that the most frequent recovery efforts are those aimed at restoring coordination of movement (46.3%), restoring mental health (43.9%) and restoring motor activity (39.5). The least frequent recovery efforts were those aimed at restoring sleep (17.6%) and nutrition (12.2%) (

Table 3)

In order to identify the existing difficulties of informal home-based caregivers, we compiled questions to identify them.

Table 5 illustrates the difficulties experienced by informal caregivers following discharge home from hospital. The data presented in the table is divided into the age groups compared. Those aged 49 years and under (46.8%) and those aged 50 years and over (53.1%). Persons 49 years and younger have the most difficulty in getting a referral for rehabilitation (59.4%) and communicating with a relative stroke survivor (45.8%) compared to persons 50 years and older. Meanwhile, persons 50 years and older have difficulties in obtaining information from medical personnel (49.5%) and obtaining medicines within the guaranteed scope of free medical care (56%) compared to the second comparable age group 49 and younger. 19.5% received stroke care allowance, 80.5% did not. We believe this is due to the fact that only 39% of stroke survivors have a disability group.

According to

Table 6, those with tertiary education proficiency in psychological rehabilitation skills is most common than those with pre-university education (35.6% vs. 22%). Similar responses can be seen for proficiency in occupational therapy skills (26% vs. 18.6%), kinesotherapy (18.4% vs. 13.6%), and physical therapy (21.8% vs. 16.9%) which is statistically significant (p= 0.000). On the contrary, those with pre-university education have more skills in speech rehabilitation (18.6%) than those with tertiary education (14.9%).

Table 7 shows comparative data on poststroke health effects depending on the period of recovery. The results of the survey showed that poststroke complications affecting cognitive function within a year of stroke onset were 46.7%; after 12 months and more, this index decreased by 3.7% and amounted to 43%. The same cannot be said for motor complications. Climbing stairs, moving around became more difficult after 12 months from the moment of stroke onset (54%), while this indicator before 12 months was 45.7%. As well as complications in physiologic needs, such as personal hygiene, dressing, increased by 3.6% (31.4% before 12 months vs. 35% after 12 months).

To the question "How do you feel about the multi-disciplinary trio?" (doctor-nurse-relative) 92.6% of respondents answered positively, 2.9% had a negative attitude.

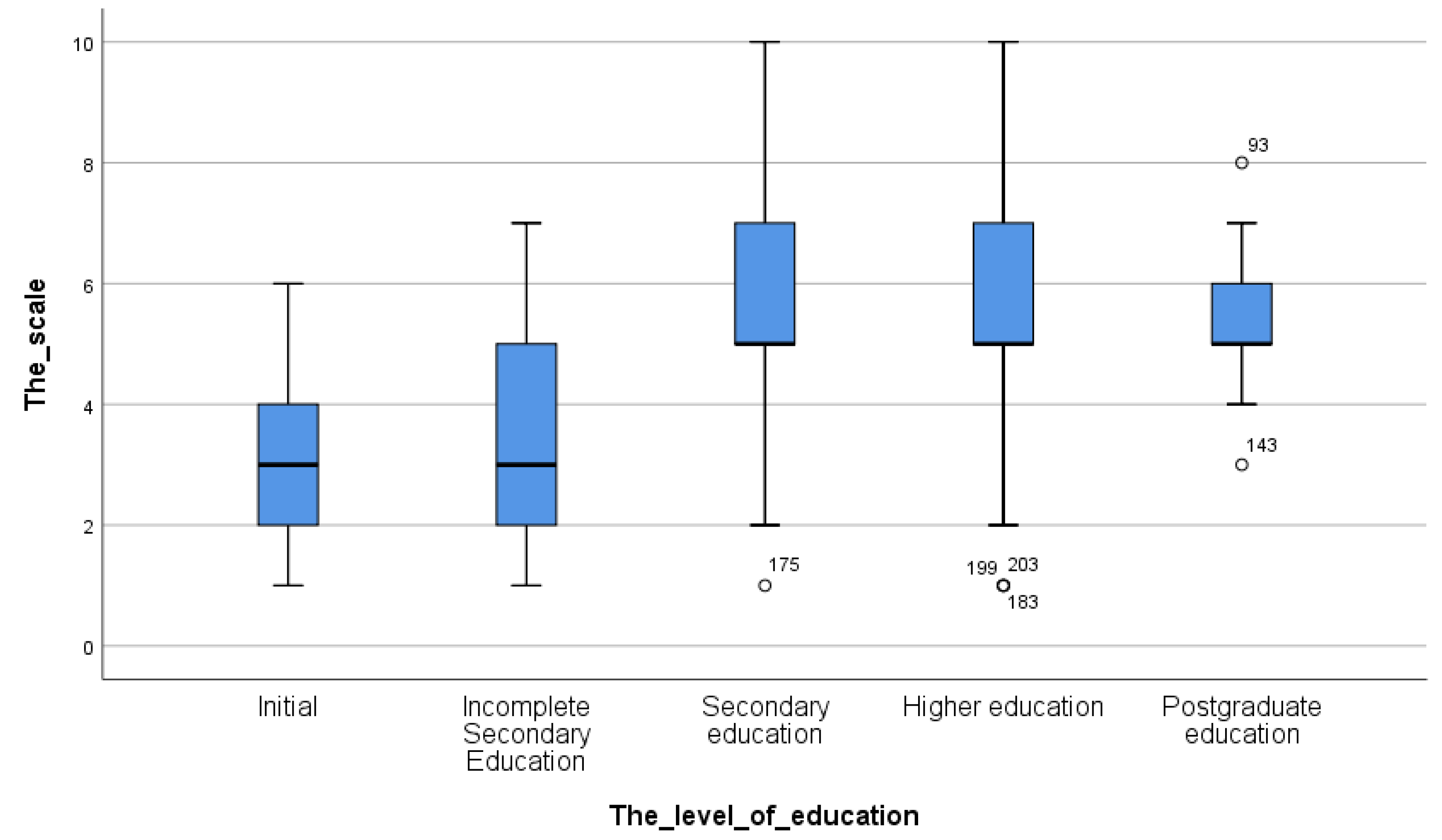

Figure 1 shows the emotional state of caregivers on a 10-point scale according to education level. Where 1-point means "bad" emotional state, respectively 10-points means "excellent". Majority of individuals with primary (62%) and incomplete secondary education (57%) rated their emotional state between two and five points. Persons with secondary, higher and postgraduate education turned out to be more emotionally stable. Their answer ranged from five to eight points.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine the challenges caregivers face after discharge from hospital to home and the most common post-stroke health deficits experienced by home caregivers. The study also aimed to assess the impact of the patient's health on the caregiver's emotional well-being. The majority of caregivers were female (59%, p=0.01). The average age was 50 years (M=50.57 (95% CI: 48.71-52.42) SD = 13,47

Many stroke patients are discharged home with functional limitations requiring assistance. Researchers at the University of Belgrade estimate that after three months, 70% of stroke survivors have reduced walking speed, and 20% remain confined to a wheelchair [

24]. Paresis of the upper extremity is a frequent impairment following acute stroke, which occurs in up to three-quarters of patients [

25].

Although partial improvement of motor dysfunction is experienced during the recovery phase, many patients experience long-term impairments affecting dexterity and motor control of the paretic upper extremity [

26].

The results of our study also show that motor impairment is present in 58% of stroke patients (p≤0.021). Consequently, caregivers' actions are most often aimed at rehabilitation activities to restore movement coordination 46.3%. In their scientific report, Sang Gu Ji and H C Chiu found that one of the most important goals of post-stroke rehabilitation is to restore the gait structure and achieve fast walking so that stroke survivors can perform their daily activities without complications [27, 28].

The tasks of achieving this goal after discharge will fall on the shoulders of home caregivers, who often feel unprepared. Moreover, in a Swiss study, many caregivers described feeling abandoned and lonely with no one to turn to after discharge [

29]. According to our study, difficulties in obtaining information from health care staff or not understanding the information received was 47.9% in those under 50 years of age, whereas in those over 50 years of age it was 49.5%. These findings are supported by other studies and reports on the needs of stroke survivors and carers following discharge home [

22]. This limitation of discretion is likely to be exacerbated by the lack of information that caregivers reportedly have about their rights to be assessed and supported, as well as the rights to support the person they are caring for. Just as commonly, communication difficulties are associated with post-stroke depression and with aphasia. Poststroke depression occurs in approximately one-third of all ischemic stroke survivors [

12]. Approximately 1/3 of people who have a stroke will be diagnosed with aphasia [

30]. Even mild forms of aphasia can negatively affect functional outcomes, mood, quality of life, social participation, and the ability to return to work [

31]. Approximately 1/3 of people who have a stroke will be diagnosed with aphasia. Even mild forms of aphasia can negatively affect functional outcomes, mood, quality of life, social participation and the ability to return to work.

Effective transitional care from hospital to home can be achieved when health professionals take a partnership approach to individualized transitional care; developing the ability of stroke survivors and caregivers to orient and inform about health and social care services to meet their care needs.

According to a study by our domestic colleagues, the main causes of high morbidity and mortality rates from stroke in the regions of Kazakhstan are a shortage of physicians, inadequate primary health care, insufficient observation and treatment, and untimely hospitalization [

32]. According to the results of our study, the difficulties in obtaining a referral for rehabilitation measures amounted to 62.9%. Although proper and timely rehabilitation can help to reduce disability and mortality rates.

Previous studies of home-based rehabilitation programs for stroke survivors have shown that post-stroke care is complex and different from care for patients with other chronic diseases [

29].

Recent health care policy discourses have accelerated efforts to minimize hospital stays and provide more care in the community and the patient’s home [

33]. There are high expectations for individuals and family members to manage their rehabilitation and aftercare, including the coordination of services [

34]. This highlights a real need to initiate high-quality self-management support earlier in the stroke pathway to enable individuals and families to manage the transition from hospital to home and live well after the experience of stroke [

35].

The shortened hospital stay usually does not give family members enough time to learn what they need to know to take on the role of caregiver [

22]. The majority of participants in this study had difficulty in caregiving due to lack of skills in speech rehabilitation (82.9%) and kinesotherapy management (84.4%). Poorly trained caregivers pose a threat to patient safety and may increase preventable re-hospitalizations [

29].

Unpreparedness for caregiving, fear for the future, stress, anxiety, and having difficulties in home rehabilitation can negatively affect the emotional well-being of caregivers. The study assessed the impact of patient health on caregiver emotional well-being using a 10-point scale. Participants with elementary and less than a high school education rated their emotional well-being low (1 to 3 points), while those with a high school education and a college degree rated their emotional well-being between 4 and 7 points. Caregivers of stroke patients reported feeling depressed, isolated, and lonely when they returned home [7, 29]. Increased emotional distress on the part of caregivers, in turn, reduces the ability to deliver high quality care to patients and negatively impacts patient outcomes [36, 37].

The evaluation of changes in post-stroke outcomes according to the recovery period showed that stair climbing and mobility became more difficult after 12 months from the onset of stroke (54%), the cognitive complication within one year from the onset of stroke was 46.7%, whereas this rate decreased by 43% after that time. In a study conducted in London, the rate of cognitive impairment within three months of stroke onset was 43.9% [

38]. Prolonged physical and cognitive impairment are major barriers to reintegration into the workplace. As the results of our study show only 30.2% of stroke survivors recovered their work activities. A study by Adams et al. showed that the success rate of return to work at follow-up was 48.9% [

39]. Failure to reintegrate into society can reduce quality of life, health status and mental health. This not only affects the emotional well-being and financial stability of both the individual and their family, but has a financial impact on society as a whole through loss of productivity and dependence on publicly funded supplementary income [

40].

It is known that recovery from stroke varies greatly. Post-stroke consequences and recovery period depend on many factors. First of all, from the type of cerebral blood flow disorder, from the scale and localization. Not an insignificant role in recovery has timely medical care, rehabilitation care measures, the initial state of health of the patient, age, comorbidities, etc.

Conclusions

This study allows us to see the peculiarities of caring for stroke patients at home, the difficulties of care and the level of proficiency in home rehabilitation skills, as well as the impact of the patient's health on the emotional state of caregivers. The results show the consequences of stroke that caregivers most often face and direct their efforts. Difficulties during caregiving and lack of readiness for home rehabilitation have a detrimental effect on the caregiver's health and, in particular, on the caregiver's emotional state.

This qualitative data analysis contributes to an in-depth understanding of stroke survivors' and caregivers' perspectives on the challenges, barriers to effective transition, and the complex interplay of post-stroke functioning. The results of this study show that opportunities and challenges coexist during transition. It is important to recognize that in order to enhance the outcome of inpatient care and improve stroke patient outcomes, caregiver burden should be minimized and care plans should be individualized to meet their specific needs.

Further research is needed to comprehensively assess the needs of the patient and, equally important, the willingness of caregivers to assume the caregiving role.

Author Contributions

Data curation G.K. K.; methodology, Z.A.Kh.; investigation, formal analysis D.S.S.; resources Z.A.Kh., S-E.D.S; software K.; methodology, Z.A.Kh.; investigation, formal analysis D.S.S.; resources Z.A.Kh., S.; project administration D.B.; conceptualization K.M.A., writing-original draft, Sh.G.M.

Funding

This research was not funded by any organization. This research is carried out within the framework of the approved topic of the doctoral dissertation of a doctoral student of the specialty “Public Health” of the Semey Medical University, Kazakhstan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Ethics Committee the Semey Medical University (Protocol №1, October 22, 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the administration of the Semey Medical University. We thank the study participants for taking time to complete our questionnaire.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- The World Health Organization. Global report on equity in health of people with disabilities 2023.

- Feigin, V. , Norrving B., Sudlow, Cathie L.,Sacco R. Updated criteria for population-based stroke and transient ischemic attack incidence studies for the 21st century. Stroke. 2018, 9, 2248–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigin, V.; Stark, B.; Johnson, C.; Roth, G.; Bisignano, C. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Neurology. 2021, 10, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigin, V.; Brainin, M.; Norrving, B. World Stroke Organization (WSO): Global Stroke Fact Sheet 2022. International Journal of Stroke. 2022, 1, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairatova, G. , Smailova D. , Kuanyshkalieva, A. Epidemiology of stroke in the republic of Kazakhstan. 2022, 5, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Akshylakov, S.; Adilbekov, E.; Akhmetzhanova, Z.; Medukhanova, S. JSC Organization and condition of the stroke service of the Republic of Kazakhstan according to the results of 2016, 31–36.

- Statistical collection "The health of the population of the Republic of Kazakhstan and the activities of healthcare organizations in 2019" Ministry of Health of the Republic of Kazakhstan 2020.: [Internet] https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/dsm/documents/details/246287?lang=ru.

- Bilda, K.; Stricker, S. Trained stroke helpers: Voluntary care model in outpatient stroke aftercare. Zeitschrift fur Gerontologie und Geriatrie. 2021, 1, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo T., P.; et al. Pure motor stroke: a reappraisal. Neurology. 1992, 4, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarno, M.T.; Buonaguro, A.; Levita, E. Characteristics of verbal impairment in closed head injured patients. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1986, 6, 400–405. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D., L.; et al. Post-stroke dysphagia: A review and design considerations for future trials. International Journal of Stroke. 2016, 4, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, L.S.; Ghose, S.S.; Swindle, R.W. Depression and other mental health diagnoses increase mortality risk after ischemic stroke. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004, 6, 1090–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas L., H.; et al. Interventions for Treating Urinary Incontinence after Stroke in Adults. Stroke. 2019, 8, E226–E227. [Google Scholar]

- Green, T.L.; McGovern, H.; Hinkle, J.L. Understanding Return to Work After Stroke Internationally: A Scoping Review. The Journal of neuroscience nursing: journal of the American Association of Neuroscience Nurses. 2021, 5, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C. Return to work after stroke: a nursing state of the science. Stroke. 2014, 9, e174–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan dated December 5, 2023 No. 43-VIII On the Republican Budget for 2024-2026 2024. 5 December.

- Bakas, T.; et al. Needs, concerns, strategies, and advice of stroke caregivers the first 6 months after discharge. The Journal of neuroscience nursing : journal of the American Association of Neuroscience Nurses. 2002, 5, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, J.E. Handbook of health psychology 2001.

- Danzl, M.M. Developing the Rehabilitation Education for Caregivers and Patients (RECAP) Model: Application to Physical Therapy in Stroke Rehabilitation. Theses and Dissertations--Rehabilitation Sciences. 2013.

- Haley W., E. [et al.]. Long-term impact of stroke on family caregiver well-being: a population-based case-control study. Neurology. 2015, 13, 1323–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheesbrough, S.; et al. The Lives of Young Carers in England. Omnibus survey report. Department for Education. 2017, 1, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron J., I. Gignac M. A. M. «Timing It Right»: a conceptual framework for addressing the support needs of family caregivers to stroke survivors from the hospital to the home. Patient education and counseling 2008, 3, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwood, N. [et al.]. Informal primary carers of stroke survivors living at home-challenges, satisfactions and coping: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Disability and rehabilitation. 2009, 5, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dujović S., D.; et al. Novel multi-pad functional electrical stimulation in stroke patients: A single-blind randomized study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2017, 4, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence E., S.; et al. Estimates of the prevalence of acute stroke impairments and disability in a multiethnic population. Stroke. 2001, 6, 279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, K.-H.; Lee, J. Temporal recovery and predictors of upper limb dexterity in the first year of stroke: A prospective study of patients admitted to a rehabilitation centre. NeuroRehabilitation. 2013, 32, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu H., C.; et al. Physical functioning and health-related quality of life: before and after total hip replacement. The Kaohsiung journal of medical sciences. 2000, 6, 285–292. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, S.G.; Kim, M.K. The effects of mirror therapy on the gait of subacute stroke patients: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical rehabilitation. 2015, 4, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz B., J.; et al. Improving Stroke Caregiver Readiness for Transition from Inpatient Rehabilitation to Home. Gerontologist. 2017, 5, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flowers H., L.; et al. Poststroke Aphasia Frequency, Recovery, and Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2016, 12, 2188–2201e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, S.M.; Sebastian, R. Diagnosing and managing post-stroke aphasia. Expert review of neurotherapeutics. 2022, 2, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenova, G.; Kausova, G.; Tazhiyeva, A. Improving multidisciplinary hospital care for acute cerebral circulation disorders in Kazakhstan. Heliyon. 2023, 8, e18435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD Health Ministers Ministerial Statemen: The Next Generation of Health Reforms OECD Health Ministerial Meeting 2017 January, 1–17.

- Lindblom, S.; et al. Perceived Quality of Care Transitions between Hospital and the Home in People with Stroke. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2020, 12, 1885–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dineen-Griffin, S. Garcia-Cardenas, V., Williams, K., Benrimoj, S. I. Helping patients help themselves: a systematic review of self-management support strategies in primary health care practice. PloS one 2019, 14, e0220116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakas, T.; Burgener, S.C. Predictors of emotional distress, general health, and caregiving outcomes in family caregivers of stroke survivors. Topics in stroke rehabilitation. 2002, 1, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach S., R.; et al. Risk factors for potentially harmful informal caregiver behavior. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005, 2, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, E. S. , Coshall, C., Dundas, R., Stewart, J., Rudd, A. G., Howard, R., & Wolfe, C. D. Estimates of the prevalence of acute stroke impairments and disability in a multiethnic population. Stroke. 2001, 32, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar]

- Adams R., A.; et al. Post-acute brain injury rehabilitation for patients with stroke. Brain Injury. 2004, 8, 811–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, G.; O’Donnell, J.; Pimentel, R.; Blake, E.; Mackenzie, L. Interventions to facilitate return to work after stroke: a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023, 20, 6469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).