1. Introduction

This study aimed to foster attachment between humans and robots by examining the process of attachment formation between animals, particularly between humans and companion animals. Common characteristics observed in these relationships were identified and incorporated as HRI behavioral elements in the design and behavior of the robot.

Humans form attachment and solidarity with companion animals through interaction, gaining emotional satisfaction and alleviating social isolation. However, the burden and responsibility of caring for a living animal can deter some individuals from adopting a pet, even if they desire emotional connection. Consequently, interest in companion robots is growing, as they can provide emotional satisfaction without the social responsibilities associated with living animals.

According to 2023 data from the global research firm Statista, dogs and cats are the most popular companion animals worldwide. Similarly, the 2022 report by the American Pet Products Association (APPA) revealed that approximately 70% of U.S. households own pets, with dogs making up 48% and cats 45%. Leveraging the popularity of these animals, we identified behavioral patterns and characteristics of dogs and cats that could be applied to robots.

Interactions between humans and companion animals encompass diverse activities such as communication, affection, training, protection, walking, play, and feeding. These interactions often involve specific behaviors, such as animals requesting petting or engaging in eye contact to express emotion. Physical touch during petting has been shown to increase oxytocin levels in both humans and animals, reducing stress and fostering attachment[

1]. To replicate these effects, we incorporated features of dogs and cats into the design of the robot EDIE(

Figure 1), emphasizing its fluffy white appearance reminiscent of fur. EDIE responds to petting with smiles and laughter, facilitating positive emotional transfer between the robot and the user. Additional behaviors like protection, walking, and play were reinterpreted as imprinting effects and cooperative hunting, and integrated into EDIE’s design and behavior as key HRI (Human-Robot Interaction) elements.

To allow as many users as possible to experience EDIE’s four HRI elements, we developed a 30-minute performance featuring EDIE as the protagonist. Participants were surveyed after the performance to identify their most preferred HRI element among grooming (petting), emotional transfer, imprinting, and cooperative hunting (play). The performance format was chosen for three main reasons:

It allowed for a large number of participants.

It minimized the potential for researcher bias influencing participant responses.

It ensured participant anonymity, aligning with ethical research standards.

This study employed large-scale surveys to identify broader trends and preferences rather than conducting in-depth analyses. A higher user preference for a specific HRI element indicated that the element effectively increased the user’s affinity and attachment to the robot. A total of 3,760 participants responded to the surveys, with 1,461 participants in the first experiment and 2,299 participants in the second.

In the first experiment, participants engaged with EDIE for more than five minutes during the introductory phase of the content. In this setting, imprinting effects were the most preferred HRI element. Conversely, in the second experiment, where participants interacted with EDIE for less than three minutes, emotional transfer emerged as the most favored element.

This suggests that deeper interactions (longer than five minutes) foster attachment through imprinting, while shorter, surface-level interactions (around three minutes) rely more on emotional transfer. These findings highlight how specific HRI elements can influence user preferences and attachment, contributing to the development of emotionally engaging robots that promote human-robot coexistence.

2. Materials and Methods

The study takes the form of a performance to secure a large number of voluntary experimental participants. Each performance lasts approximately 30 minutes, during which one participant is paired with a robot to enter the performance space. Participants experience and enjoy the HRI features applied to EDIE and return the robot upon exiting the performance. The performance scenario is meticulously designed to ensure that participants evenly experience all of EDIE’s HRI elements.

The HRI elements implemented in EDIE consist of four key features: grooming, emotional transfer, imprinting effect, and cooperative hunting. These elements are simplified representations of the complex and multi-layered interactions commonly observed between humans and companion animals (e.g., dogs and cats), such as communication, affection, training and learning, protection, walking, playing, and feeding activities.

To ensure the integrity of the experimental performance, it is crucial to prevent interruptions caused by robot malfunctions during the performance. If a robot malfunctions and the participant must restart their experience, this could lead to an uneven exposure to certain HRI elements or diminish the immersive quality of the performance, thereby contaminating the response samples. Therefore, to minimize the likelihood of robot malfunctions, the functionalities for interactions have been simplified.

2.1. The Fuzzy Robot Representing Grooming

The fuzzy robot interacts with users by rubbing its body against their hands, inviting them to groom it. This behavior mimics a form of communication and affection observed between humans and animals.

As confirmed by previous research, soft tactile stimulation through fur is closely linked to emotional comfort. H.Harlow’s 1958 study highlighted the correlation between fur and psychological stability[

2], while James Burkett’s 2016 research demonstrated that oxytocin is released during gentle stroking of fur[

3], fostering emotional bonding. Furthermore, Amy McCullough’s 2018 study found that owning pets with soft fur and engaging in grooming behaviors not only provides psychological satisfaction but also significantly reduces stress[

4]. These findings have been consistently validated over time.

Based on these insights, this study incorporated the characteristics of grooming into the design of EDIE’s appearance. The robot’s white, fuzzy exterior was specifically chosen to provide users with emotional satisfaction through soft tactile stimulation, while also evoking the familiarity of mammalian animals.

However, to prevent users from forming preconceived notions about EDIE’s behavioral patterns, the robot was designed to resemble no specific animal. While EDIE’s appearance is reminiscent of a mammal with fur, its design deliberately avoids imitating any particular species.

The outer covering of EDIE was crafted using microfiber fabric with a hair length of 15mm. This length was chosen to allow users’ fingers to sink into the fur, maximizing tactile stimulation. The soft microfiber fur is designed to penetrate between the fingers, replicating the emotional comfort experienced when stroking a dog or cat.

Through this design, the study aimed to provide users with emotional satisfaction via grooming interactions with EDIE, fostering a sense of attachment to the robot.

2.2. EDIE’s Expressions and Sounds Representing Emotional Transfer

Laughter and smiling reduce cortisol, the stress hormone, relax the body, and enhance feelings of happiness, leading to a more positive emotional state. These effects help promote bonding and a sense of unity[

5].

Laughter and smiling go beyond mere emotional expressions; they strengthen social connections. In 2018, P.Mui explained that people tend to mimic each other’s smiles, resulting in emotional contagion[

6]. Thus, laughter and smiling are among the most intuitive and immediate reactions, effectively fostering positive relationships. To enable users to experience the emotional transfer HRI element, this study designed EDIE to smile in response to being groomed by the user.

EDIE’s laughter combines expressions and sounds. For facial expression, EDIE’s eyes were designed to occupy one-third of its face. This large size allows for exaggerated expressions, a technique commonly used in animation to emphasize characters’ emotions. The eyes were animated at 20 frames per second and displayed on an LCD screen, ensuring vivid expression and emphasizing the robot’s character.

Although companion animals cannot use human language, people interpret their intentions by integrating factors such as the length, pitch, and tone of their vocalizations, along with facial expressions and gestures. Similarly, EDIE emits unique robotic sounds instead of language, utilizing variations in length, pitch, and tone to represent different emotions. These sounds were synchronized with EDIE’s eye expressions to convey emotional responses.

This study anticipated that EDIE’s laughter and smiles would transfer positive emotions to users, fostering affinity and attachment based on these positive emotional interactions. (

Figure 2).

2.3. Following User Representing Imprinting Effect

The "imprinting effect" was first identified in 1937 by Austrian biologist and ethologist K.Lorenz[

7]. It refers to the phenomenon where young animals form a bond with their mother during early life stages. Over time, the concept expanded to describe how exposure to specific stimuli or environments during critical developmental periods creates a strong and lasting imprint on the brain. This is commonly observed in young animals that perceive the first moving object they encounter after birth as their parent.

Maternal attachment, where a mother forms a bond with her offspring, is similarly linked to the imprinting response. During early life stages, when an individual experiences safety and protection from its mother, this memory influences its behavior as it matures and becomes a parent itself. Recognizing its offspring’s dependence, the individual forms an attachment that fosters care and protection, ultimately enhancing the offspring’s survival rate. This process contributes to the species’ continuity through successful reproduction and survival. Observing a companion animal following its owner and feeling maternal attachment toward it is also a complex interaction of biological, psychological, and evolutionary factors, directly connected to the imprinting effect. This study aimed to evoke maternal attachment in users toward EDIE by assigning the robot the role of an infant. EDIE was designed to follow a single designated user as its companion.

However, the study’s experimental format posed a challenge, as it was structured as a 30-minute performance where participants changed frequently. This left no time for the robot to learn to recognize and follow its companion through training. To address this issue, EDIE was programmed to recognize specific patterns such as flowers, butterflies, or clouds. A fabric sleeve featuring these patterns was created to wrap around the user’s calf, enabling EDIE to track the sleeve as its designated target.

Additionally, the performance scenario required participants to wear the sleeve to be paired with the robot. This setup encouraged participants to actively engage with the experiment by wearing the sleeve, allowing EDIE to follow its designated user seamlessly.

2.4. A Game with the Robot Representing Cooperative Hunting

Cooperative hunting is a behavior where multiple individuals act collectively to effectively hunt larger or faster prey. This behavior is widely observed across various species, from lions, wolves, and whales to ants and bees. According to K.Tsutsui’s 2024 study, cooperative hunting allows for the efficient acquisition of energy necessary for survival while also strengthening social solidarity[

8].

The previously discussed features, grooming and emotional transfer, provide emotional satisfaction through sensory interactions between humans and robots. Similarly, the imprinting effect fosters psychological and instinctive bonding, encouraging attachment to the robot.

Cooperative hunting, however, differs in that it promotes emotional bonding through solidarity, which is then leveraged to form attachment. Bonding refers to emotional connections formed between individuals or small groups based on trust, affection, and mutual understanding, while solidarity denotes emotional ties that arise among individuals sharing common goals or benefits. Through collective actions to achieve a shared purpose, individuals develop a sense of belonging and stability within the group, as well as emotional reliance on other group members, ultimately forming attachment.

In summary, solidarity and bonding share the commonality of fostering close relationships that lead to attachment. However, solidarity originates within a broader social context, while bonding is more personal and intimate, creating emotionally positive relationships.

Cooperative hunting between humans and animals has evolved into forms of play as humans moved away from a survival mode based on hunting and gathering. Activities like playing frisbee with a dog or engaging a cat with a fishing rod are forms of play that foster emotional connection between humans and their pets. While traditional cooperative hunting rewarded teamwork with "food," modern play rewards "fun" as the primary incentive.

To incorporate cooperative hunting as an HRI element for EDIE, this study developed a game that the user and EDIE could enjoy together. The game was designed not as a screen-based activity but as a physical experience enabled through digital art.

Research by N.Rob has shown that sharing experiences with others has a significant impact on attachment formation[

10].

Thus, by engaging the user and EDIE in a cooperative game where they complete missions together and experience enjoyment as a reward, this study aims to foster human attachment to the robot.

2.5. Development of an HRI Experience Scenario

The primary focus in designing the content scenario was ensuring that users could experience all four HRI elements—grooming, emotional transfer, imprinting effect, and cooperative hunting—through the story’s progression.

The overall storyline is as follows:

EDIE is a robotic lifeform residing on an alien planet(

Figure 3) that has been invaded by an evil computer virus. Participants, visiting the planet to save EDIE from this crisis, meet their designated EDIE companion (imprinting effect). They calm the frightened EDIE by grooming it (grooming), and when EDIE regains its courage and begins to smile again (emotional transfer), the group collaborates with EDIE to rebuild the planet damaged by the virus (cooperative hunting).

Although the storyline is simple, it meticulously integrates all four HRI elements selected for this study. To ensure participants fully experience these elements, a docent was deployed to guide and facilitate the experience.

Table 1.

HRI Elements Applied to EDIE and Experience Scenario.

Table 1.

HRI Elements Applied to EDIE and Experience Scenario.

| HRI Elements Applied to EDIE |

Scenario for Experiencing HRI Elements |

| Grooming & Emotional Contagion |

Time to be friend with EDIE |

| To elicit positive emotional expressions from the robot, the user’s actions must first act as a trigger.

Therefore, these two elements are connected in an action and reaction elationship. |

At the beginning of the performance, guided by a docent, users spend time petting the robot, observing its reactions, and bonding with it.

When the user pets the robot, it expresses joy through a combination of eye movements and sounds. |

| Imprinting |

Paired Robot |

| By placing the user in the role of a parent and having the robot act as an offspring that follows the parent, the user’s maternal attachment to the robot is formed. |

Upon entering the performance venue, each user is paired 1:1 with a robot.

During this time, the robot follows only the designated user. |

| Cooperative Hunting |

Digital Art Games |

| The user and the robot perform a given game together, experiencing the behavior patterns of cooperative hunting. |

The performance venue is divided into sections, each featuring games such as treasure hunts, shooting games, and escape games.

As participants and robots complete each game mission, they progress to the next stage. |

2.6. Development of the Robot EDIE

The hardware design and construction of the robot were focused on implementing the HRI elements of grooming, emotional transfer, imprinting effect, and cooperative hunting.

EDIE was designed as a wheel-based robot with a spherical body approximately the size of a soccer ball. One side of the sphere was cut diagonally to form the face, allowing EDIE to always look upward toward the user.

The robot’s exterior was crafted using white microfiber fabric to implement grooming. This fabric was draped over the robot’s body, ensuring that users would not feel any discomfort while stroking the fur. Ultra-thin FSR (Force Sensitive Resistor) sensors were installed under the fabric to detect the user’s touch. When a touch was detected, EDIE would respond by expressing positive emotions, such as laughter and smiles. These emotions were conveyed through a combination of eye shapes displayed on an LCD screen and corresponding sounds.

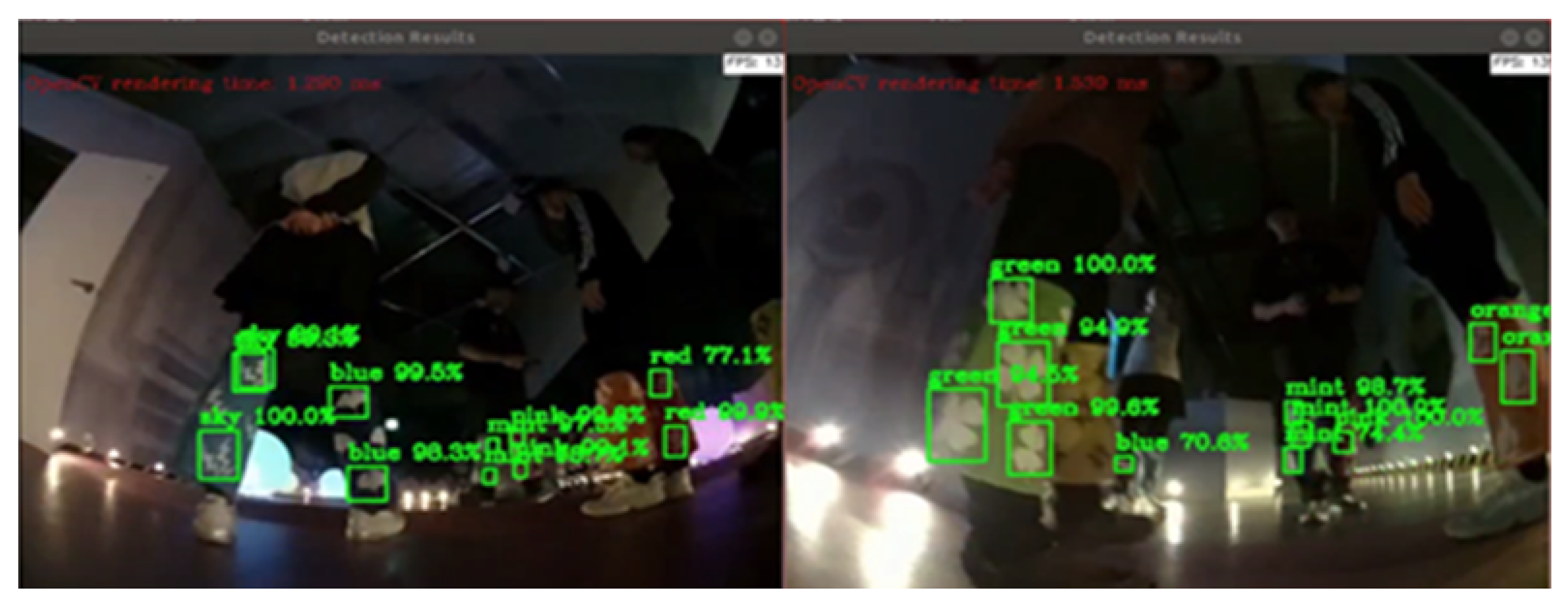

A camera was installed on the forehead of EDIE’s face to enable vision recognition. This allowed EDIE to identify the patterns on the user’s sleeve and follow the corresponding user.

To help users distinguish their designated EDIE, each robot was equipped with an LED strip. The LEDs emitted soft, distinct colors that were visible through the white fur, making each EDIE uniquely identifiable.

These features enable EDIE to provide users with a dynamic and interactive experience while supporting various HRI elements integrated into the robot’s design and behavior.

Figure 4.

EDIE’s Hardwear and Apperence Design.

Figure 4.

EDIE’s Hardwear and Apperence Design.

To develop the platform responsible for EDIE’s processing, ROS (Robot Operating System) was utilized. ROS simplifies development by breaking down the robot’s components into minimal units called nodes. The entire system was structured around a central Behavior Control node, with input nodes including Camera, FSR, and Laser, and output nodes such as Motor, LED, Display, and Sound.

To enable EDIE to follow users, the camera first captures the pattern on the sleeve. The system filters this input to detect each distinct pattern drawn on the fabric. The captured image is then digitally labeled and processed through a supervised learning procedure to build an AI model. This trained model is deployed on EDIE’s onboard Neural Stick, allowing the robot to identify and track the designated user using on-device AI.

The implementation of on-device AI, rather than relying on cloud-based systems, was intended to ensure stable content operation without being affected by unreliable network communications.

Figure 5.

EDIE’s pattern recognition.

Figure 5.

EDIE’s pattern recognition.

3. Experiment and Survey

The experiment in this study was conducted in the form of a performance. This approach was chosen to prevent participants from being consciously aware that they were part of an experiment, which might influence their responses to the subsequent survey about their interaction with EDIE. Additionally, this format aimed to encourage large-scale user participation to enhance the reliability of the response data while ensuring participants’ anonymity.

Each performance session was limited to a maximum of 7 participants. Consequently, a group consisted of 7 participants, 7 EDIE robots, and one docent. The docent, trained in advance, was instructed not to interfere with the interactions between participants and EDIE to avoid influencing their experience. However, the docent played a crucial role in guiding participants to experience all four HRI elements and in maintaining the storyline throughout the performance.

At the end of the performance, participants were asked to cast their votes at a survey board placed near the exit. The survey posed a single question: "Which of the four HRI elements applied to EDIE did you like the most?" Male participants were given green stickers, while female participants received white stickers. Each participant selected one preferred element and placed their sticker in the corresponding box, organized by age groups.

This method allowed for a clear visual representation of participants’ preferences based on gender, age, and their most favored HRI element. It enabled the identification of trends across different demographic groups without compromising the participants’ privacy. By minimizing psychological barriers, the study succeeded in collecting a larger volume of reliable data.

Table 2.

Survey Question and Intent.

Table 2.

Survey Question and Intent.

Q. What did you like most about this exhibition?

Please place your sticker accordingly. |

| Option |

Intent of the Question |

| 1. I like that EDIE followed me around. |

Imprinting |

| 2. I like that EDIE smiled when I petted it. |

Emotional Transfer |

| 3. I liked EDIE’s soft fur. |

Grooming |

| 4. I liked playing games with EDIE. |

Cooperative Hunting |

3.1. Experiment 1

The first experiment was conducted over 15 days in October 2019 in Seoul, with 1,461 participants responding to the survey after the performance. The performance scenario was designed to include two instances each of grooming, emotional transfer, and imprinting effect, and four instances of cooperative hunting. Although cooperative hunting appeared to have more opportunities compared to the other elements, the balance among the four HRI elements was ultimately maintained.

This balance was achieved as participants, while playing the game (cooperative hunting) with the robot, often spontaneously engaged in grooming by stroking the robot, observed its smiles (emotional transfer), and experienced the robot following them throughout the performance space (imprinting effect). These spontaneous interactions were not included in the calculated experience counts, ensuring equal emphasis on all four HRI elements.

Figure 6.

Scene from the First Experiment.

Figure 6.

Scene from the First Experiment.

3.2. Experiment 2

The experiment, which had been suspended due to the COVID-19 pandemic, resumed in 2023 and was conducted over 18 days in Busan, with 2,299 participants responding to the survey.

The intended number of experiences for the four HRI elements in the performance was the same as in the first experiment. However, there was one key difference. In the scenario, after participants were paired with EDIE at the beginning of the performance, they were given time to groom and observe EDIE’s reactions to build familiarity.

In the first experiment, this interaction lasted for over 5 minutes, allowing sufficient time for bonding. In the second experiment, however, this duration was reduced to under 3 minutes due to the overwhelming number of participants who signed up for the performance following the transition to an endemic phase.

Figure 7.

Scene from the Second Experiment.

Figure 7.

Scene from the Second Experiment.

4. Results

The results of the survey responses from a total of 3,760 participants in the performance-based experiments are as follows: 1,461 respondents from the first experiment and 2,299 respondents from the second experiment.

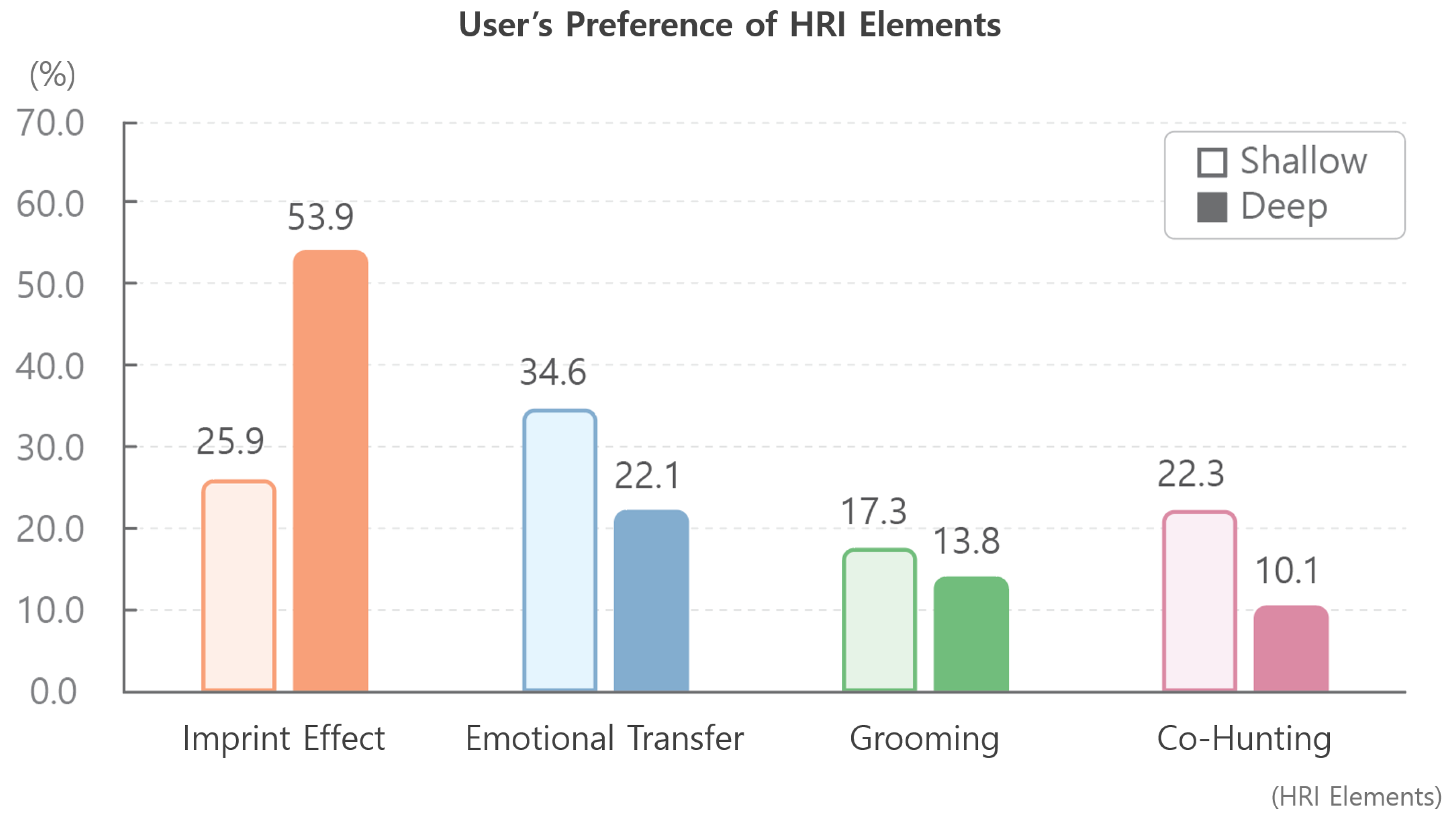

Figure 8.

Results of the First(L) and the Second Survey(R).

Figure 8.

Results of the First(L) and the Second Survey(R).

4.1. Results of the First Experiment

Among the 1,461 participants in the first experiment’s survey, 712 were female, and 749 were male. By age group, there were 607 children (under 10 years old), 420 adolescents (10–20 years old), and 434 adults.

Of the HRI elements applied to EDIE, the Imprinting effect was the most favored, with 767 votes, more than double the votes for the second place element, Emotional Transfer, which received 324 votes. Grooming and Cooperative Hunting followed with 210 and 160 votes, respectively.

4.2. Results of the Second Experiment

In the second experiment’s survey, 1,115 participants were female, and 1,184 were male. By age group, there were 1,190 children (under 10 years old), 650 adolescents (10–20 years old), and 459 adults.

In this survey, Emotional transfer was the most favored HRI element, receiving 773 votes, followed by Imprinting effect with 572 votes, Cooperative Hunting with 531 votes, and Grooming with 423 votes.

Unlike the first survey, where there was a preference gap of more than twice between the first and second ranked elements, the second survey showed relatively smaller differences in preference across all elements.

4.3. Analysis

The four HRI elements incorporated into the performance scenarios—Imprinting Effect, Emotional Transfer, Grooming, and Cooperative Hunting—were applied the same number of times in both the 2019 and 2023 scenarios: Imprinting Effect (2 times), Emotional Transfer (2 times), Grooming (2 times), and Cooperative Hunting (4 times). Additionally, both performances had similar runtimes of approximately 25 minutes, and the number of users admitted per session ranged from 7 to 8, making the experimental conditions nearly identical.

The primary difference between the two surveys lies in whether users had sufficient time to interact with EDIE when they first met the robot, and whether this allowed adequate opportunities for rapport-building. Based on the extent of pre-performance interaction, the 1,461 users from 2019 were classified into a "deep interaction group," while the 2,299 users from 2023 were classified into a "shallow interaction group." The responses to the HRI elements were then evaluated based on these group distinctions.

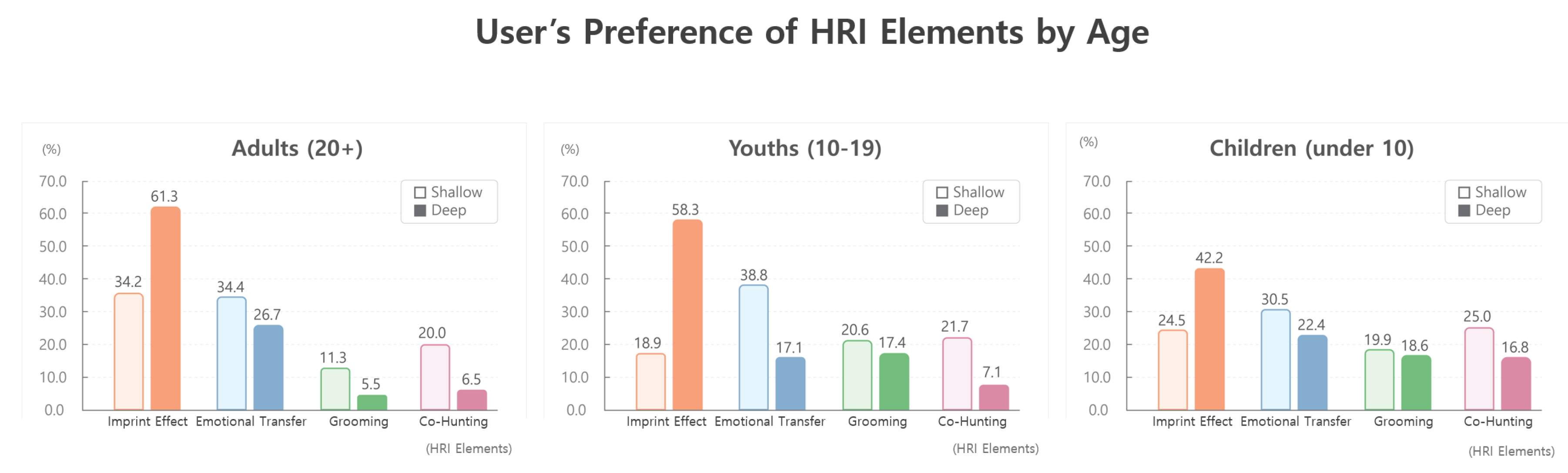

Grooming provides satisfaction through tactile stimulation, fostering attachment, and is thus referred to as "sensory stimulation." Emotional Transfer delivers emotional satisfaction by conveying positive emotions, so it is termed "emotional stimulation." The Imprinting Effect, grounded in attachment theory, represents the instinctual behavior of young individuals to ensure survival and forms the basis of maternal attachment, earning it the label "instinctual stimulation." Cooperative Hunting, as applied to EDIE, provides enjoyment through the reward of mission completion and is therefore called "playful stimulation." An analysis of the overall participant responses revealed that the deep interaction group showed the highest preference (53.9%) for the instinctual stimulation of the robot following users. Conversely, the shallow interaction group exhibited the highest preference (34.6%) for the emotional stimulation of the robot’s smiling expression, indicating that the degree of interaction with the robot influences the preferred HRI element. When analyzed by age, preference for instinctual stimulation interactions increased among adolescents and adults compared to children, and the difference between the deep and shallow interaction groups became more pronounced.

Figure 9.

User’s Preference of HRI Elements.

Figure 9.

User’s Preference of HRI Elements.

Figure 10.

User’s Preference of HRI Elements by Age.

Figure 10.

User’s Preference of HRI Elements by Age.

In the first experiment, participants had a relatively longer time at the beginning to observe EDIE and establish rapport. During this time, participants, from their perspective as caregivers, replaced the robot EDIE with an infant, fostering maternal attachment through the Imprinting Effect. Once maternal attachment was established, it demonstrated a significantly stronger impact compared to other HRI elements. This suggests that activating the instinctual behavior of maternal care during the process of fostering attachment has a force that surpasses sensory, emotional, and playful stimulations.

On the other hand, in the second experiment, where the rapport-building time was shorter, Emotional Transfer showed relatively higher preference. This was likely because participants, without sufficient time to favor one domain over others—sensory, emotional, instinctual, or playful—found "laughter," which stimulates both visual and auditory senses simultaneously, to be the most intuitive and immediately engaging experience.

5. Conclusions

This study was initiated to identify the most effective characteristics that encourage attachment between humans and robots, particularly focusing on companion robots that provide emotional stability and satisfaction to users in a world where humans and robots coexist.

To this end, the robot EDIE was designed with four HRI elements in its appearance and behavioral patterns: Grooming, Emotional Transfer, Imprinting Effect, and Cooperative Hunting. When sufficient time for interaction and rapport-building with users is ensured, the Imprinting Effect, wherein EDIE follows the user, proved to be the most effective in fostering user attachment.

Bowlby’s attachment theory explains that humans are biologically evolved to form emotional bonds and attachments, which play a decisive role in development[

9]. Children who grow within such relationships eventually perceive and raise their own offspring as attachment figures based on their experiences.

Rob applied Bowlby’s attachment theory to robots, emphasizing the importance of the concepts of Secure Base and Safe Haven[

10]. A robot can become an attachment figure when it is perceived as “always supporting me and staying by my side.” The findings of this study align with Bowlby and Rob’s assertions, as the Imprinting Effect and Emotional Transfer were the most favored HRI elements by users. EDIE follows a designated individual and responds positively to the user’s actions with smiles and laughter. In doing so, EDIE fulfills the roles of a Secure Base and a Safe Haven, always supporting and staying close to the user.

Therefore, companion robots designed for long-term interaction with users would benefit from incorporating these HRI elements. Strategically, such robots should be designed to become objects of care and affection for users while also possessing the ability to positively influence the user’s emotions. This aligns with the fundamental purpose of companion robots as emotionally supportive entities.

6. Future Work

This study raises an intriguing question: Should companion robots be perceived as “entities that give affection to users” or as “entities that become the objects of users’ affection”? Which of these perceptions aligns more closely with the original goal of addressing social issues through robots?

Currently, the eighth generation of EDIE is under development. Once EDIE 8 is completed, we plan to conduct large-scale field tests, as in previous versions, by securing a substantial sample population.

Through these tests, we aim to explore whether a companion robot that loves humans or one that is loved by humans better fulfills the purpose of companion robots.

It is our hope that this study will inspire researchers in the field of companion robots and contribute to the expansion of the companion robot market as a whole.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the MOTIE(Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy) in Korea, under the Korea Robot Industry Core Technology Development Project(20018699), supervised by the Korea Evaluation Institute of Industrial Technology(KEIT).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nagasawa, M., Mitsui, S., En, S., Ohtani, N., Ohta, M., Sakuma, Y., Onaka, T., Mogi, K. & Kikusui, T. Oxytocin-gaze positive loop and the coevolution of human-dog bonds. Science. 348, 333-336 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Harlow, H. The nature of love.. American Psychologist. 13, 673 (1958).

- Burkett, J., Andari, E., Johnson, Z., Curry, D., Waal, F. & Young, L. Oxytocin-dependent consolation behavior in rodents. Science. 351, 375-378 (2016). [CrossRef]

- McCullough, A., Jenkins, M., Ruehrdanz, A., Gilmer, M., Olson, J., Pawar, A., Holley, L., Sierra-Rivera, S., Linder, D., Pichette, D. & Others Physiological and behavioral effects of animal-assisted interventions on therapy dogs in pediatric oncology settings. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 200 pp. 86-95 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Kramer, C. & Leitao, C. Laughter as medicine: A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventional studies evaluating the impact of spontaneous laughter on cortisol levels. Plos One. 18, e0286260 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Mui, P., Goudbeek, M., Roex, C., Spierts, W. & Swerts, M. Smile mimicry and emotional contagion in audio-visual computer-mediated communication. Frontiers In Psychology. 9 pp. 2077 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, K. Der Kumpan in der Umwelt des Vogels. Der Artgenosse als auslösendes Moment sozialer Verhaltungsweisen.. Journal Für Ornithologie. Beiblatt.(Leipzig). (1935).

- Tsutsui, K., Tanaka, R., Takeda, K. & Fujii, K. Collaborative hunting in artificial agents with deep reinforcement learning. Elife. 13 pp. e85694 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss: retrospect and prospect.. American Journal Of Orthopsychiatry. 52, 664 (1982). [CrossRef]

- Rabb, N., Law, T., Chita-Tegmark, M. & Scheutz, M. An attachment framework for human-robot interaction. International Journal Of Social Robotics. pp. 1-21 (2022). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).