Submitted:

29 November 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

In this work, a series of boronated amidines based on the closo-dodecaborate anion and amino acids containing an amino group in the side chain of the general formula [B12H11NHC(NH(CH2)nCH(NH3)COOH)CH3], where n = 2, 3, 4, were synthesized. These derivatives contain conserved α-amino and α-carboxyl groups recognized by the binding centers of the large neutral amino acid transporter (LAT) system, which serves as a target for the clinically applied BNCT agent para-boronophenylalanine (BPA). The paper describes several approaches to synthesizing the target compounds, their acute toxicity studies, and tumor uptake studies in vivo in two tumor models.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Safety and Tolerability of Compounds in Laboratory Animals

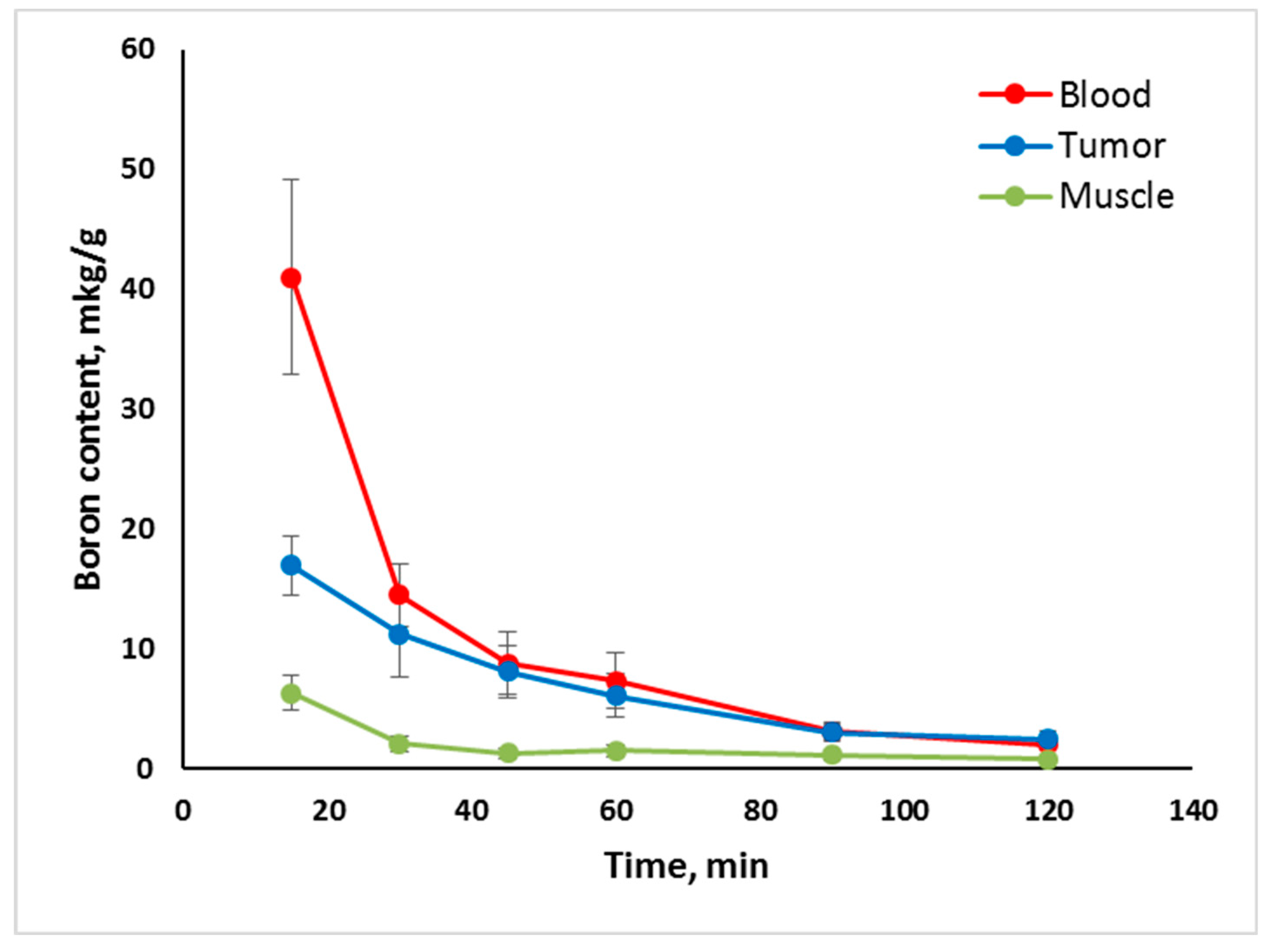

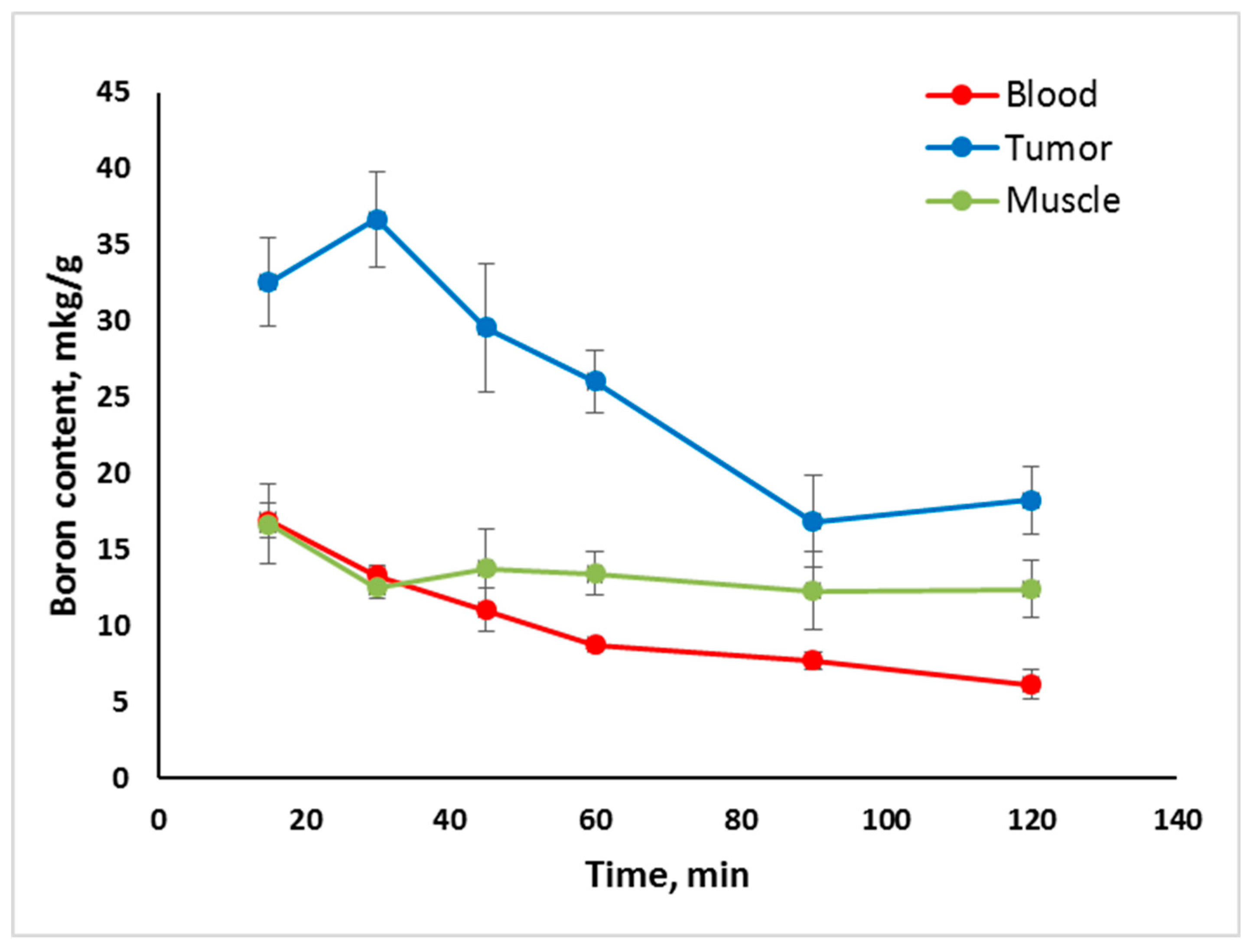

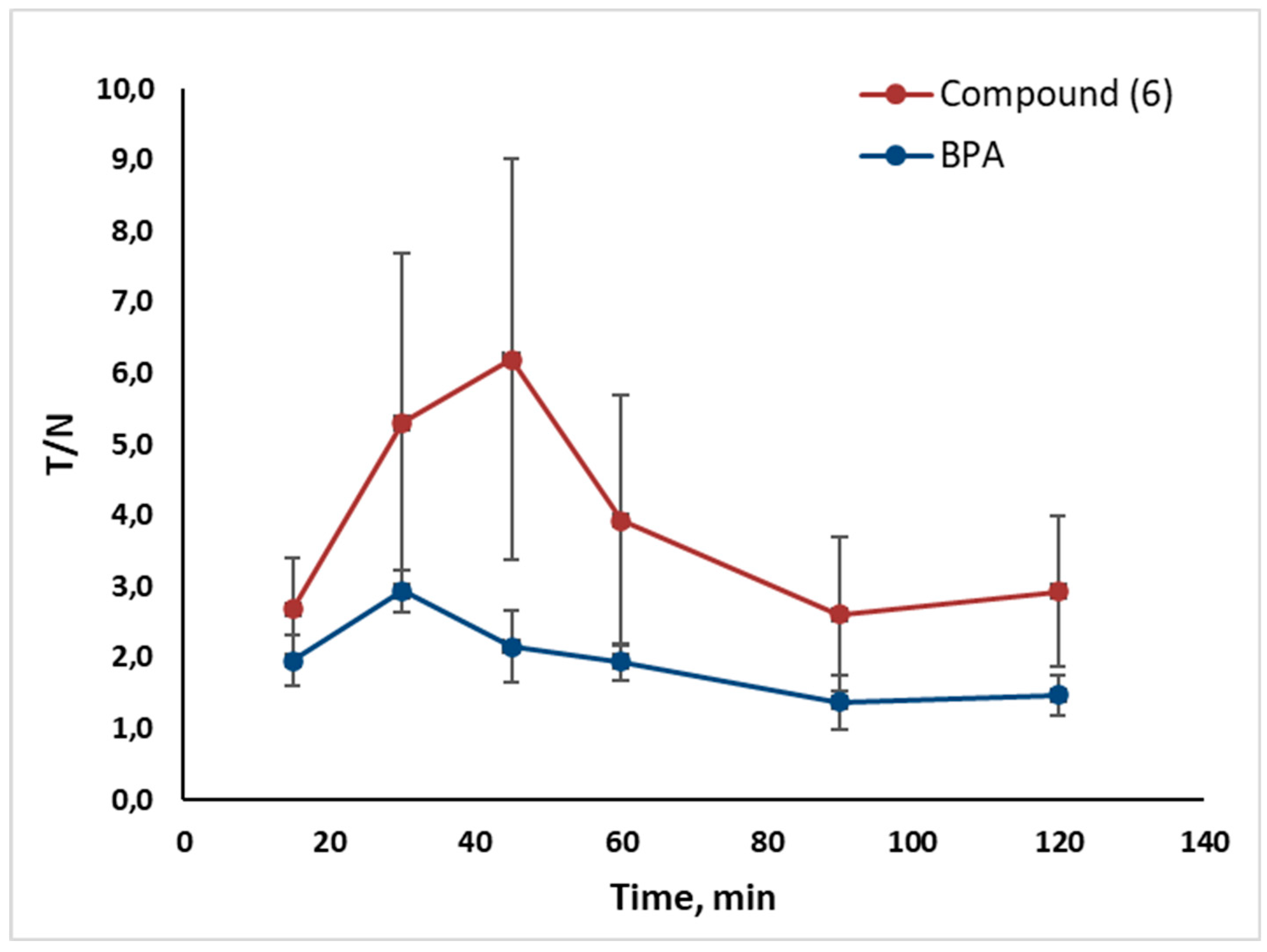

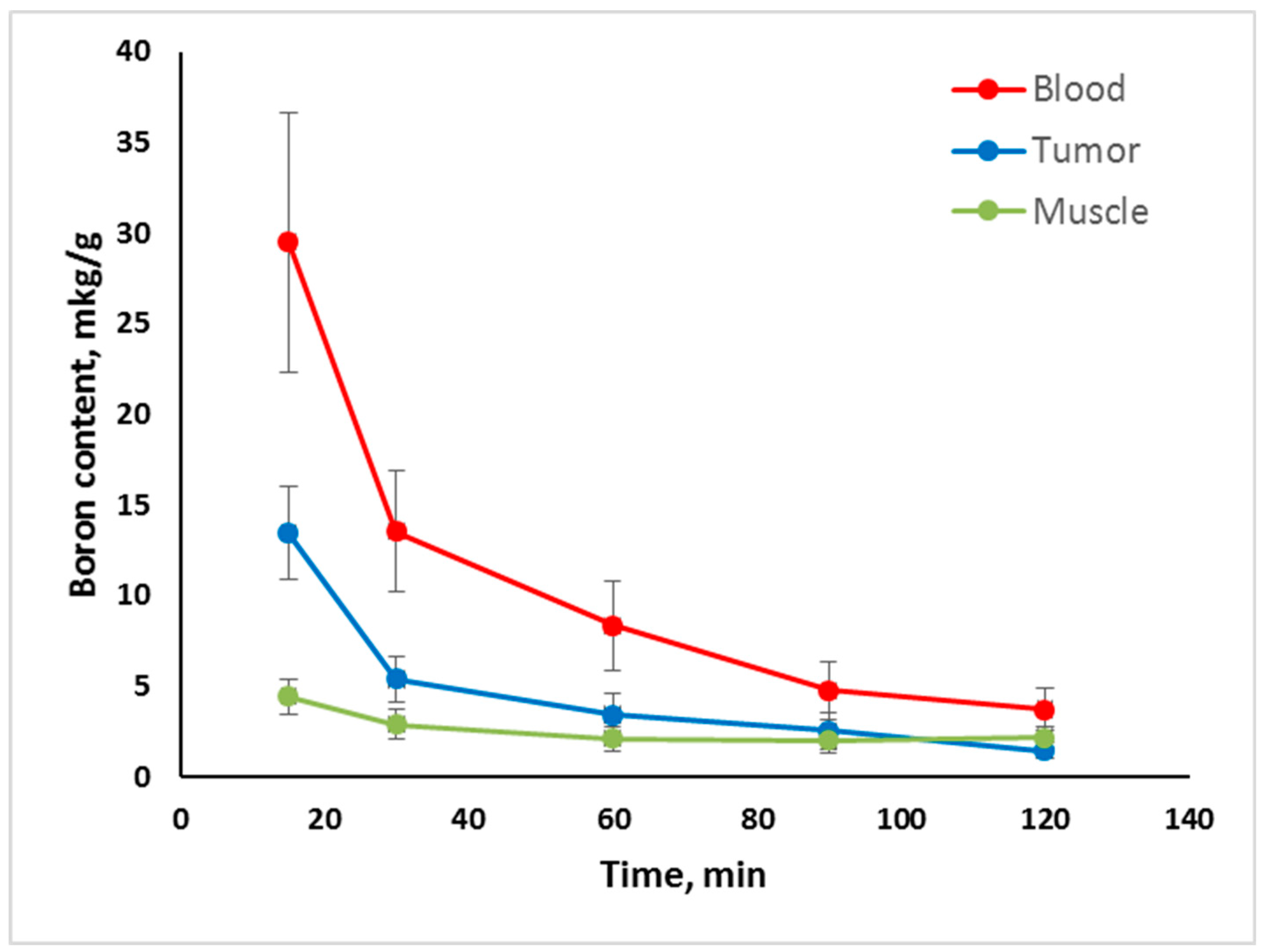

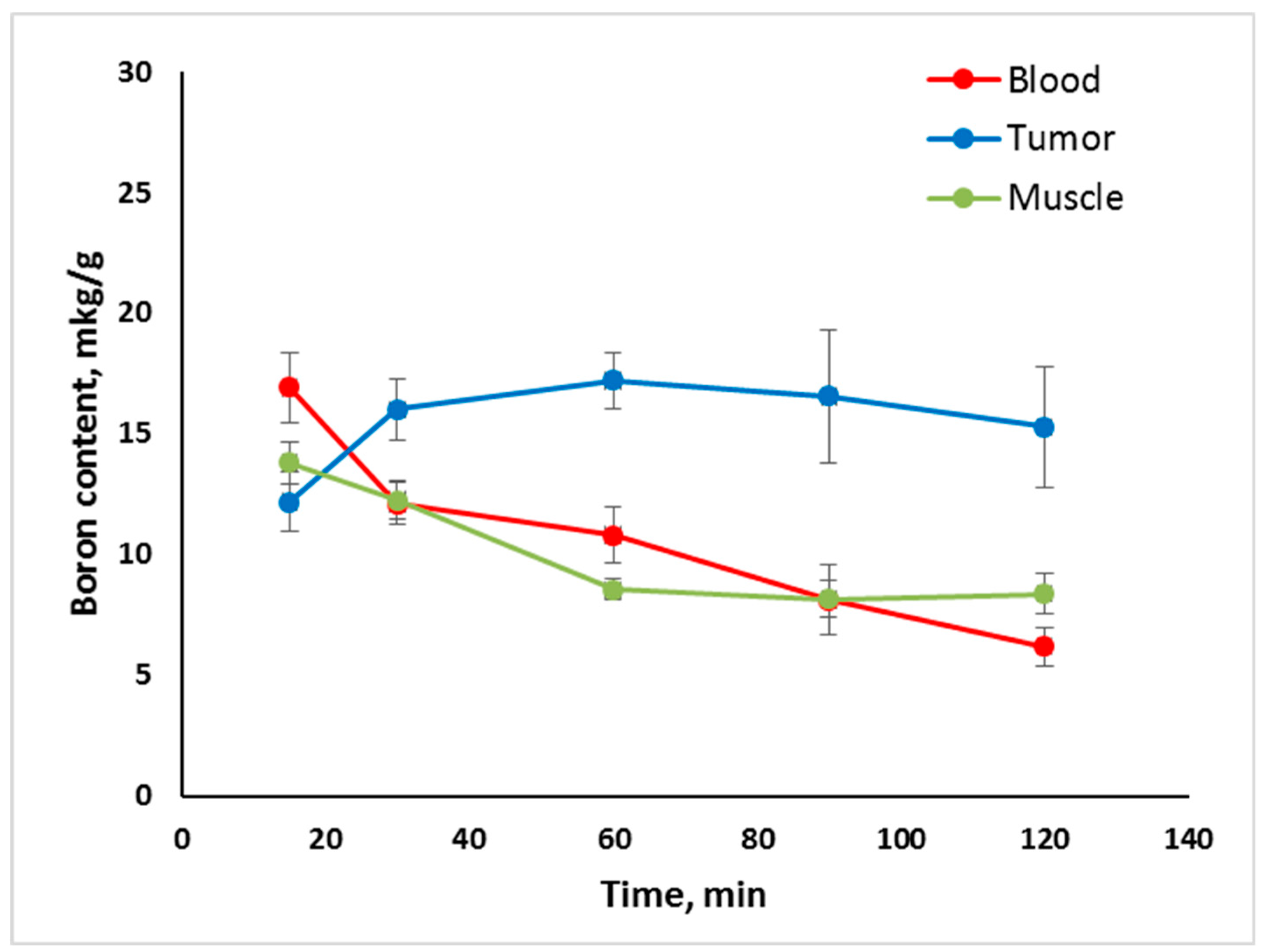

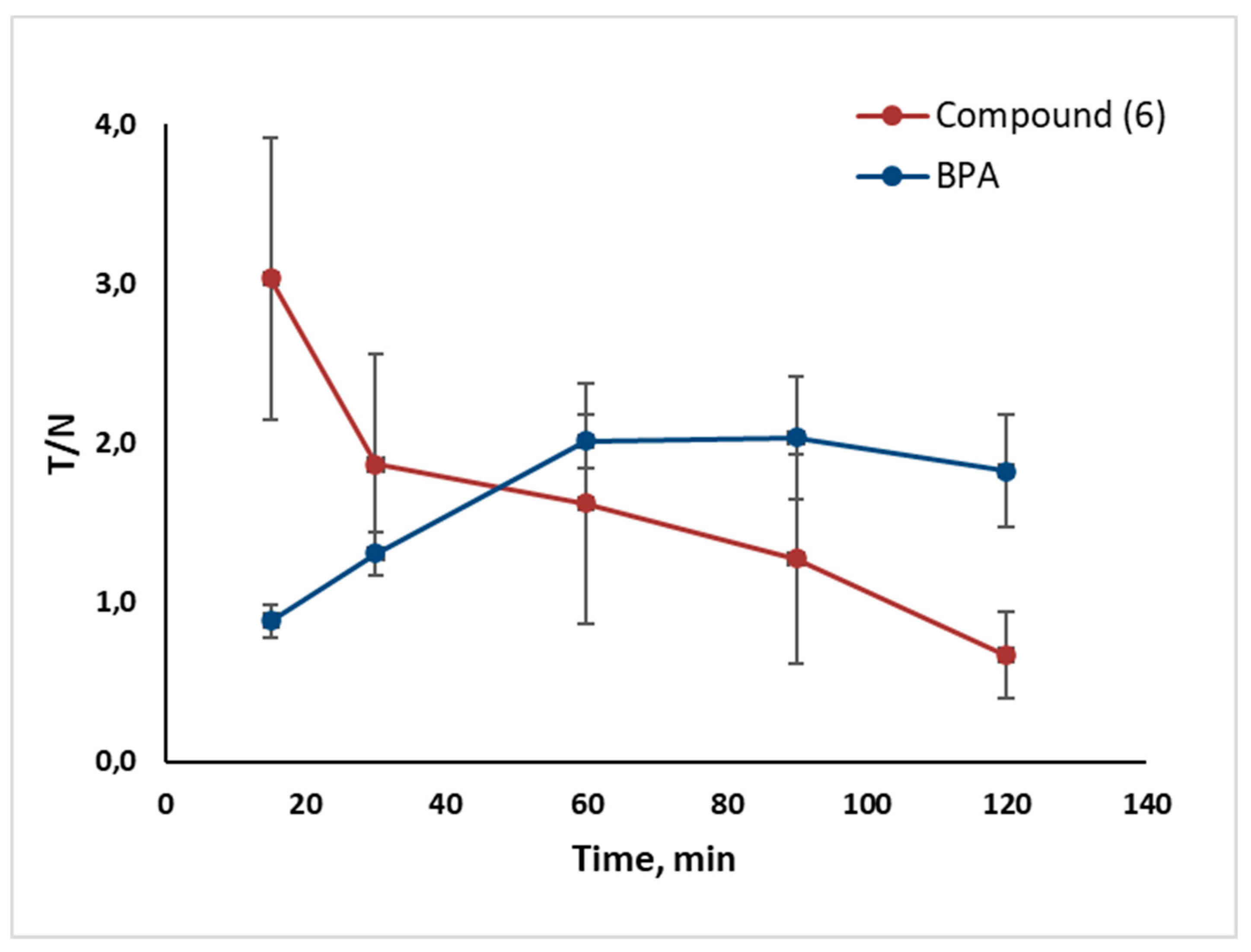

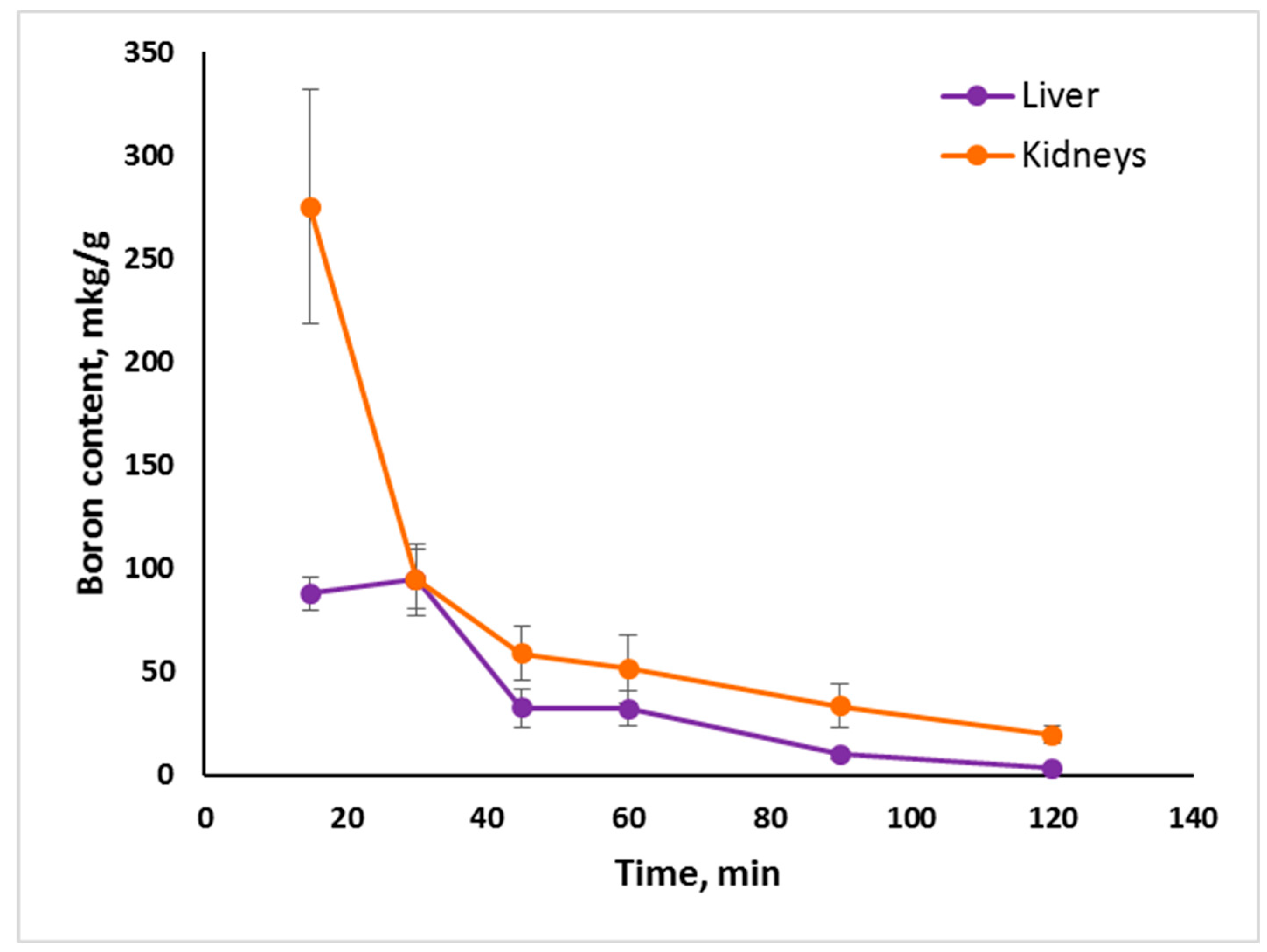

2.2. In Vivo Tumor Uptake

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. NMR Spectroscopy

3.2. Analytical Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (RP-HPLC)

3.3. Preparative RP-HPLC

3.4. High-Resolution ESI Mass Spectrometry

3.5. X-Ray Crystal Structure Determination

3.6. Sample Preparation and Determination of Boron in Biological Samples

3.7. Computational Details

3.8. Reagents and Materials

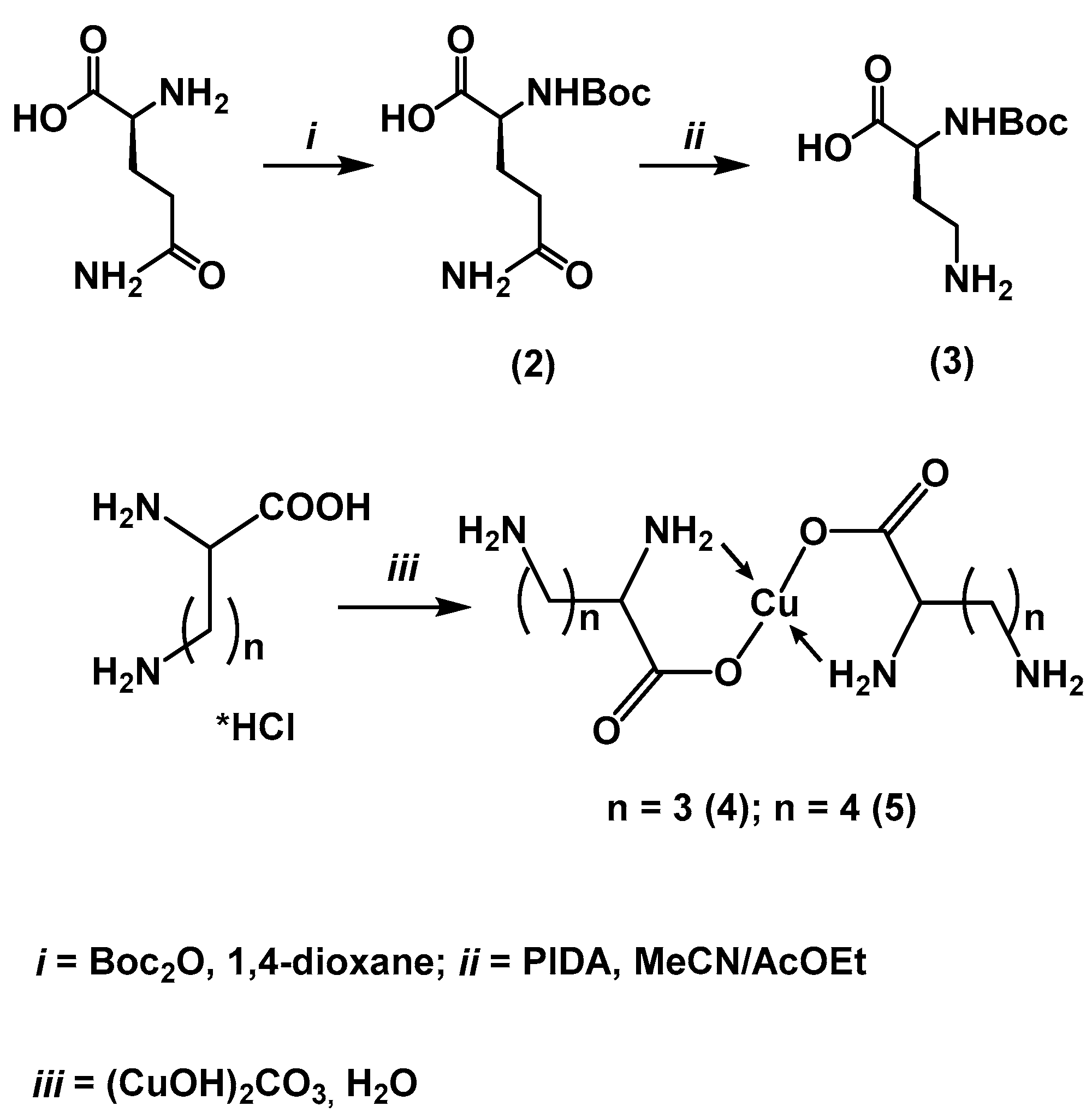

- Nα-(tert-Butoxycarbonyl)-L-glutamine (Boc-L-glutamine) (2)

- Nα-Boc-β-amino-L-alanine (3)

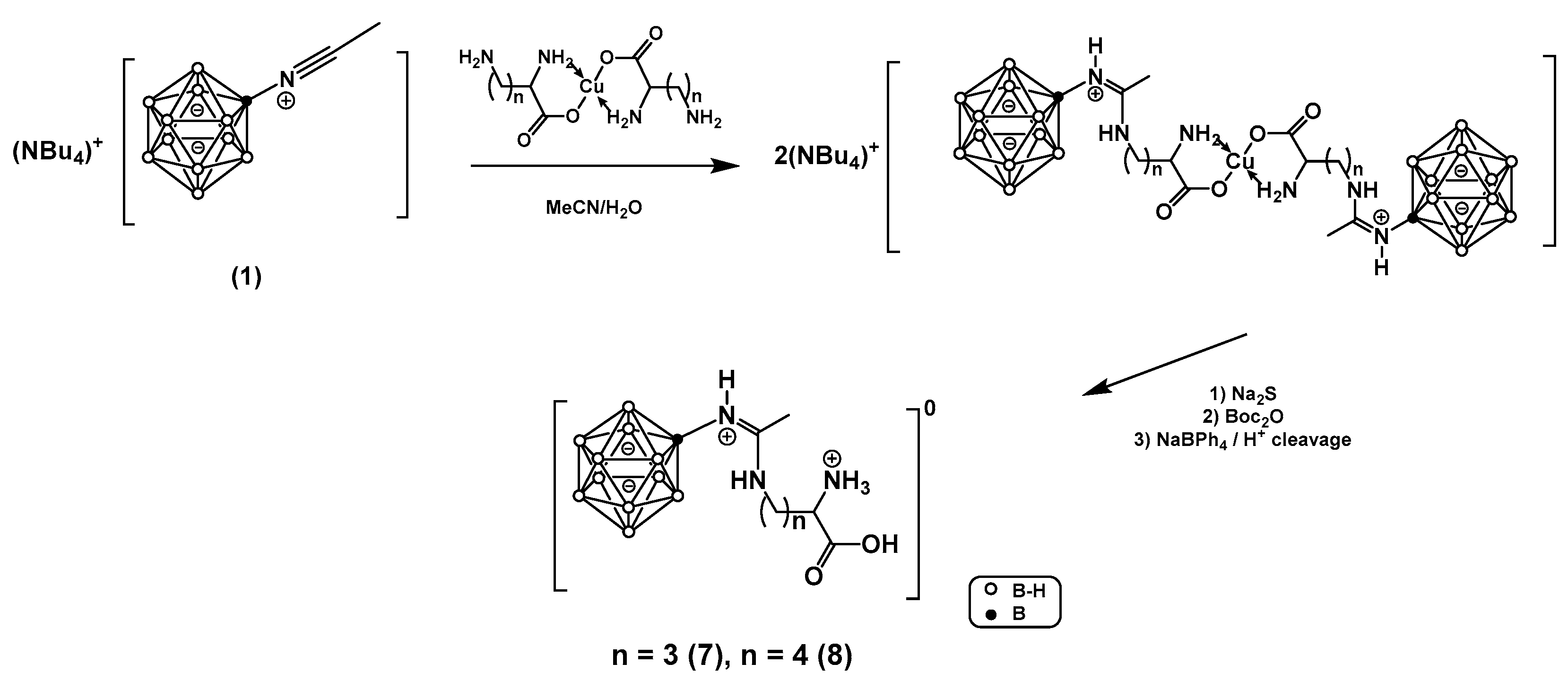

- General Method for the Synthesis of Copper Complexes of Diamino Acids

- Cu(Orn*HCl)₂ (4) and Cu(Lys*HCl)₂ (5)

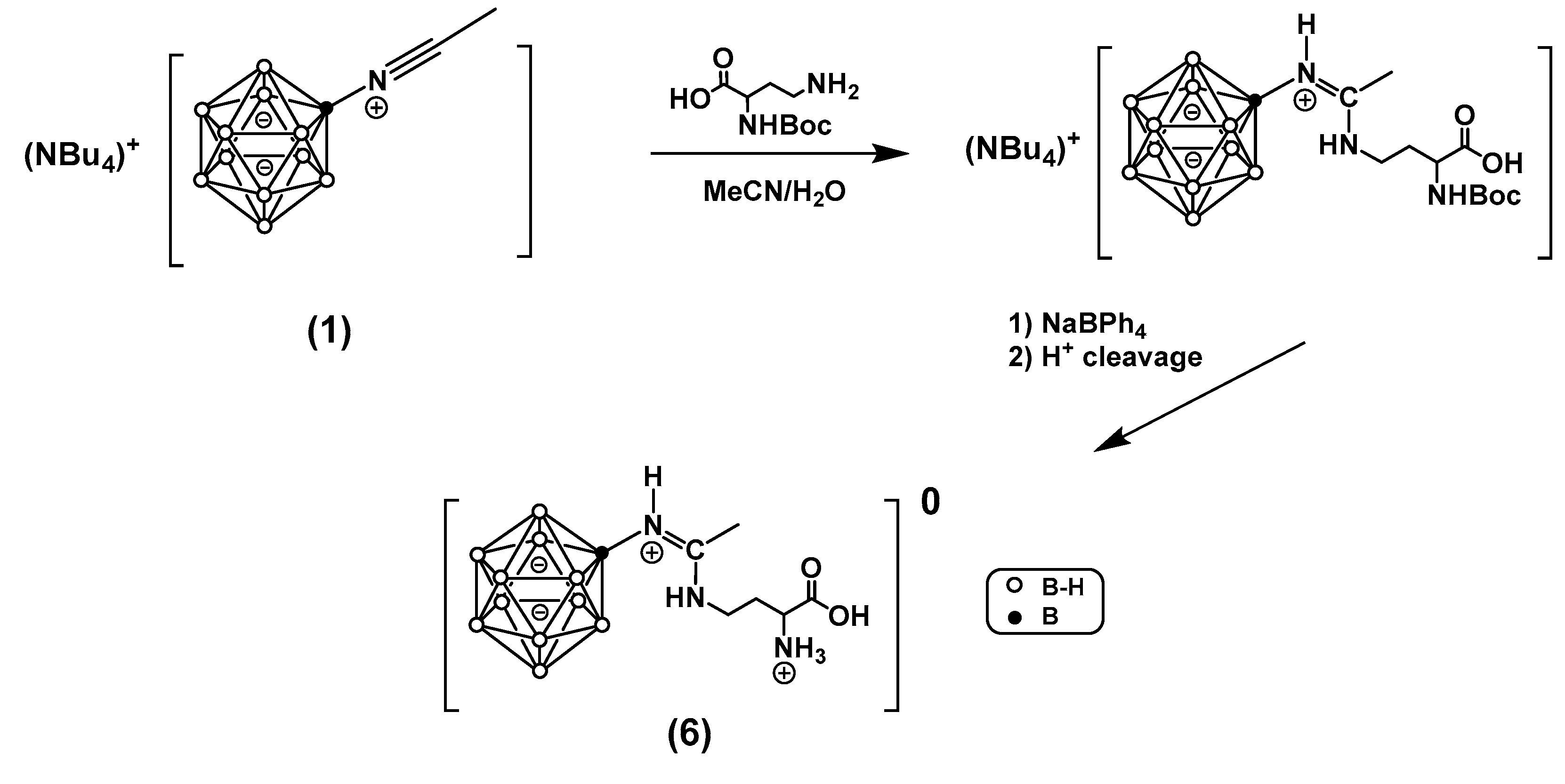

- [B₁₂H₁₁NHC(NH(CH₂)₂CH(NH₃)COOH)CH₃]*3H₂O (6)

3.9. General Method for the Synthesis of Boronated Diamino Acid Derivatives

- [B₁₂H₁₁NHC(NH(CH₂)₃CH(NH₃)COOH)CH₃]*3H₂O (7)

- [B₁₂H₁₁NHC(NH(CH₂)₃CH(NH₃)COOH)CH₃]*3H₂O (8)

- Animal Studies

- Preparation of solutions of compounds (6)-(8) for biological studies:

- Safety and Tolerability Studies

- Tumor uptake of Compounds

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barth, R.F.; Mi, P.; Yang, W. Boron Delivery Agents for Neutron Capture Therapy of Cancer. Cancer Commun 2018, 38, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Chong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Pan, J.; Huang, C.; Sun, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, X.; Shao, Y.; Jin, C.; et al. A Review of Planned, Ongoing Clinical Studies and Recent Development of BNCT in Mainland of China. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck-Sickinger, A.G.; Becker, D.P.; Chepurna, O.; Das, B.; Flieger, S.; Hey-Hawkins, E.; Hosmane, N.; Jalisatgi, S.S.; Nakamura, H.; Patil, R.; et al. New Boron Delivery Agents. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 2023, 38, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Dai, K.; Li, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, T.; Jun Xie; Ruiping Zhang; Liu, Z. A Boron-10 Nitride Nanosheet for Combinational Boron Neutron Capture Therapy and Chemotherapy of Tumor. Biomaterials 2021, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawar, V.M.; Beck, M.; Shetgaonkar, A.D.; Pal, R.; Bakshi, A.K.; Nadkarni, V.S. Synthesis and Application of Boron Polymers for Enhanced Thermal Neutron Dosimetry. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B 2020, 462, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Singh, P.; Singh, K.; Gaharwar, U.S.; Meena, R.; Kumar, M.; Nakagawa, F.; Wu, S.; Suzuki, M.; Nakamura, H.; et al. Boron Nitride (10BN) a Prospective Material for Treatment of Cancer by Boron Neutron Capture Therapy (BNCT). Mater Lett 2020, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Qiao, W.; Shen, Y.; Xu, H.; Fan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lan, Y.; Gong, Y.; Chen, F.; Feng, S. Biomimetic Boron Nitride Nanoparticles for Targeted Drug Delivery and Enhanced Antitumor Activity. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soloway, A.H.; Whitman, B.; Messer, J.R. Penetration of Brain and Brain Tumor by Aromatic Compounds as a Function of Molecular Substituents. III. J Med Pharm Chem 1962, 5, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvinen, J.; Pulkkinen, H.; Rautio, J.; Timonen, J.M. Amino Acid-Based Boron Carriers in Boron Neutron Capture Therapy (BNCT). Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.P.; Yu, C.S. Recent Development of Radiofluorination of Boron Agents for Boron Neutron Capture Therapy of Tumor: Creation of 18F-Labeled C-F and B-F Linkages. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchino, H.; Kanai, Y.; Kim, D.K.; Wempe, M.F.; Chairoungdua, A.; Morimoto, E.; Anders, M.W.; Endou, H. Transport of Amino Acid-Related Compounds Mediated by L-Type Amino Acid Transporter 1 (LAT1): Insights Into the Mechanisms of Substrate Recognition. Mol Pharmacol 2002, 61, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, J.H.; Barth, R.F.; Wyzlic, I.M.; Soloway, A.H.; Rotaru, J.H. In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation of O-Carboranylalanine as a Potential Boron Delivery Agent for Neutron Capture Therapy. Anticancer Res 1995, 15, 2033–2038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gomez, F.A.; Hawthorne, M.F. A Simple Route to C-Monosubstituted Carborane Derivatives. J Org Chem 1992, 57, 1384–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyzlic, I.M.; Soloway, A.H. A General, Convenient Way to Carborane-Containing Amino Acids for Boron Neutron Capture Therapy. Tetrahedron Lett 1992, 33, 7489–7490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashar, J.K.; Lama, D.; Moore, D.E. Synthesis of Dihydroxycarboranyl Phenylalanine for Potential Use in Boron Neutron Capture Therapy or Melanoma. Tetrahedron Lett 1993, 34, 6799–6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radel, P.A.; Kahl, S.B. Enantioselective Synthesis of <scp>l</Scp> - and <scp>d</Scp> -Carboranylalanine. J Org Chem 1996, 61, 4582–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, R.F.; Kabalka, G.W.; Yang, W.; Huo, T.; Nakkula, R.J.; Shaikh, A.L.; Haider, S.A.; Chandra, S. Evaluation of Unnatural Cyclic Amino Acids as Boron Delivery Agents for Treatment of Melanomas and Gliomas. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2014, 88, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmquist, J.; Carlsson, J.; Markides, K.E.; Pettersson, P.; Olsson, P.; Sunnerheim-Sjöberg, K.; Sjöberg, S. Asymmetric Synthesis of O- and p-Carboranyl Amino Acids. In Cancer Neutron Capture Therapy; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1996; pp. 131–136. [Google Scholar]

- Kahl, S.B.; Schaeck, J.J.; Laster, B.; Warkentien, L. Enantioselective Syntheses of 10B-Enriched L- and D-Carboranylalanine and Their Radiobiological Evaluation in V-79 Chinese Hamster Cells. In Frontiers in Neutron Capture Therapy; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2001; pp. 797–802. [Google Scholar]

- Kusaka, S.; Hattori, Y.; Uehara, K.; Asano, T.; Tanimori, S.; Kirihata, M. Synthesis of Optically Active Dodecaborate-Containing l-Amino Acids for BNCT. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2011, 69, 1768–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, Y.; Kusaka, S.; Mukumoto, M.; Ishimura, M.; Ohta, Y.; Takenaka, H.; Uehara, K.; Asano, T.; Suzuki, M.; Masunaga, S.; et al. Synthesis and in Vitro Evaluation of Thiododecaborated α, α- Cycloalkylamino Acids for the Treatment of Malignant Brain Tumors by Boron Neutron Capture Therapy. Amino Acids 2014, 46, 2715–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, Y.; Kusaka, S.; Mukumoto, M.; Uehara, K.; Asano, T.; Suzuki, M.; Masunaga, S.; Ono, K.; Tanimori, S.; Kirihata, M. Biological Evaluation of Dodecaborate-Containing <scp>l</Scp> -Amino Acids for Boron Neutron Capture Therapy. J Med Chem 2012, 55, 6980–6984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futamura, G.; Kawabata, S.; Nonoguchi, N.; Hiramatsu, R.; Toho, T.; Tanaka, H.; Masunaga, S.-I.; Hattori, Y.; Kirihata, M.; Ono, K.; et al. Evaluation of a Novel Sodium Borocaptate-Containing Unnatural Amino Acid as a Boron Delivery Agent for Neutron Capture Therapy of the F98 Rat Glioma. Radiation Oncology 2017, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryabchikova, M.N.; Nelyubin, A.V.; Smirnova, A.V.; Finogenova, Yu.A.; Skribitsky, V.A.; Shpakova, K.E.; Kubasov, A.S.; Zhdanov, A.P.; Lipengolts, A.A.; Grigorieva, E.Y.; et al. Preparation of Closo-Dodecaborate Anion Conjugate with Ethyl Glycinate and Study of Its Biodistribution in Melanoma Model B16F10. Russian Journal of Inorganic Chemistry 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelyubin, A.V.; Selivanov, N.A.; Bykov, A.Yu.; Klyukin, I.N.; Novikov, A.S.; Zhdanov, A.P.; Karpechenko, N.Yu.; Grigoriev, M.S.; Zhizhin, K.Yu.; Kuznetsov, N.T. Primary Amine Nucleophilic Addition to Nitrilium Closo-Dodecaborate [B12H11NCCH3]−: A Simple and Effective Route to the New BNCT Drug Design. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 13391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laskova, J.; Ananiev, I.; Kosenko, I.; Serdyukov, A.; Stogniy, M.; Sivaev, I.; Grin, M.; Semioshkin, A.; Bregadze, V.I. Nucleophilic Addition Reactions to Nitrilium Derivatives [B 12 H 11 NCCH 3 ] − and [B 12 H 11 NCCH 2 CH 3 ] −. Synthesis and Structures of Closo -Dodecaborate-Based Iminols, Amides and Amidines. Dalton Transactions 2022, 51, 3051–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stogniy, M.Y.; Erokhina, S.A.; Suponitsky, K.Y.; Anisimov, A.A.; Sivaev, I.B.; Bregadze, V.I. Nucleophilic Addition Reactions to the Ethylnitrilium Derivative of: Nido -Carborane 10-EtCN-7,8-C2B9H11. New Journal of Chemistry 2018, 42, 17958–17967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAHRENHOLZ, F.; THIERAUCH, K. SYNTHESIS OF p -AMINO-L-PHENYLALANINE DERIVATIVES WITH PROTECTED p -AMINO GROUP FOR PREPARATION OF p -AZIDO-L-PHENYLALANINE PEPTIDES. Int J Pept Protein Res 1980, 15, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelyubin, A.V.; Klyukin, I.N.; Novikov, A.S.; Zhdanov, A.P.; Selivanov, N.A.; Bykov, A.Yu.; Kubasov, A.S.; Zhizhin, K.Yu.; Kuznetsov, N.T. New Aspects of the Synthesis of Closo-Dodecaborate Nitrilium Derivatives [B12H11NCR]− (R = n-C3H7, i-C3H7, 4-C6H4CH3, 1-C10H7): Experimental and Theoretical Studies. Inorganics (Basel) 2022, 10, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreimann, E.L.; Itoiz, M.E.; Dagrosa, A.; Garavaglia, R.; Farías, S.; Batistoni, D.; Schwint, A.E. The Hamster Cheek Pouch as a Model of Oral Cancer for Boron Neutron Capture Therapy Studies: Selective Delivery of Boron by Boronophenylalanine. Cancer Res 2001, 61, 8775–8781. [Google Scholar]

- Garabalino, M.A.; Heber, E.M.; Hughes, A.M.; González, S.J.; Molinari, A.J.; Pozzi, E.C.C.; Nievas, S.; Itoiz, M.E.; Aromando, R.F.; Nigg, D.W.; et al. Biodistribution of Sodium Borocaptate (BSH) for Boron Neutron Capture Therapy (BNCT) in an Oral Cancer Model. Radiat Environ Biophys 2013, 52, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruker AXS Inc. SAINT. Version 8.40A. 2019.

- Krause, L.; Herbst-Irmer, R.; Sheldrick, G.M.; Stalke, D. Comparison of Silver and Molybdenum Microfocus X-Ray Sources for Single-Crystal Structure Determination. J Appl Crystallogr 2015, 48, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT - Integrated Space-Group and Crystal-Structure Determination. Acta Crystallogr A 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2 : A Complete Structure Solution, Refinement and Analysis Program. J Appl Crystallogr 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. The ORCA Program System. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NBO 7.0. E. D. Glendening, J.K. NBO 7.0. E. D. Glendening, J.K. Badenhoop, A.E.R.; J. E. Carpenter, J.A. Bohmann, C.M. Morales, P.K.; C. R. Landis, and F. Weinhold, T.C.I.; University of Wisconsin, Madison, W. (2018) No Title.

- Bader, R.F.W. Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn : A Multifunctional Wavefunction Analyzer. J. Comp. Chem. 2011, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemcraft - Graphical Software for Visualization of Quantum Chemistry Computations. Available online: https://www.chemcraftprog.com.

- Rasheed, A.M.; Namala, R.; Manne, N.; Vanjivaka, S.; Dhamjewar, R.; Balasubramanian, G. Concise and Efficient Synthesis of Highly Potent and Selective Dipeptidyl Peptidase II Inhibitors. Synth Commun 2008, 38, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radić Stojković, M.; Piotrowski, P.; Schmuck, C.; Piantanida, I. A Short, Rigid Linker between Pyrene and Guanidiniocarbonyl-Pyrrole Induced a New Set of Spectroscopic Responses to the Ds-DNA Secondary Structure. Org Biomol Chem 2015, 13, 1629–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardes, G.J.L.; Linderoth, L.; Doores, K.J.; Boutureira, O.; Davis, B.G. Site-Selective Traceless Staudinger Ligation for Glycoprotein Synthesis Reveals Scope and Limitations. ChemBioChem 2011, 12, 1383–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

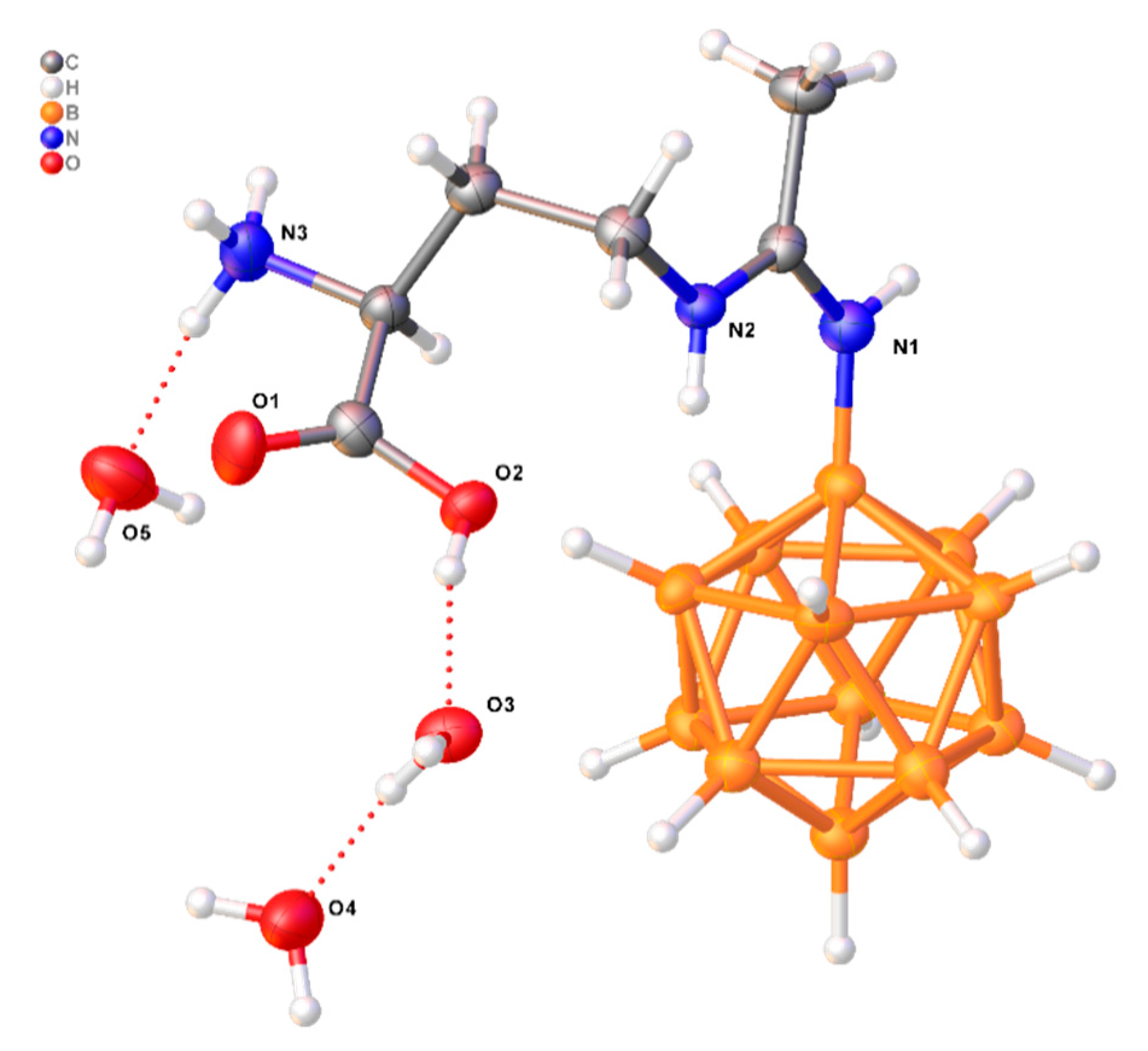

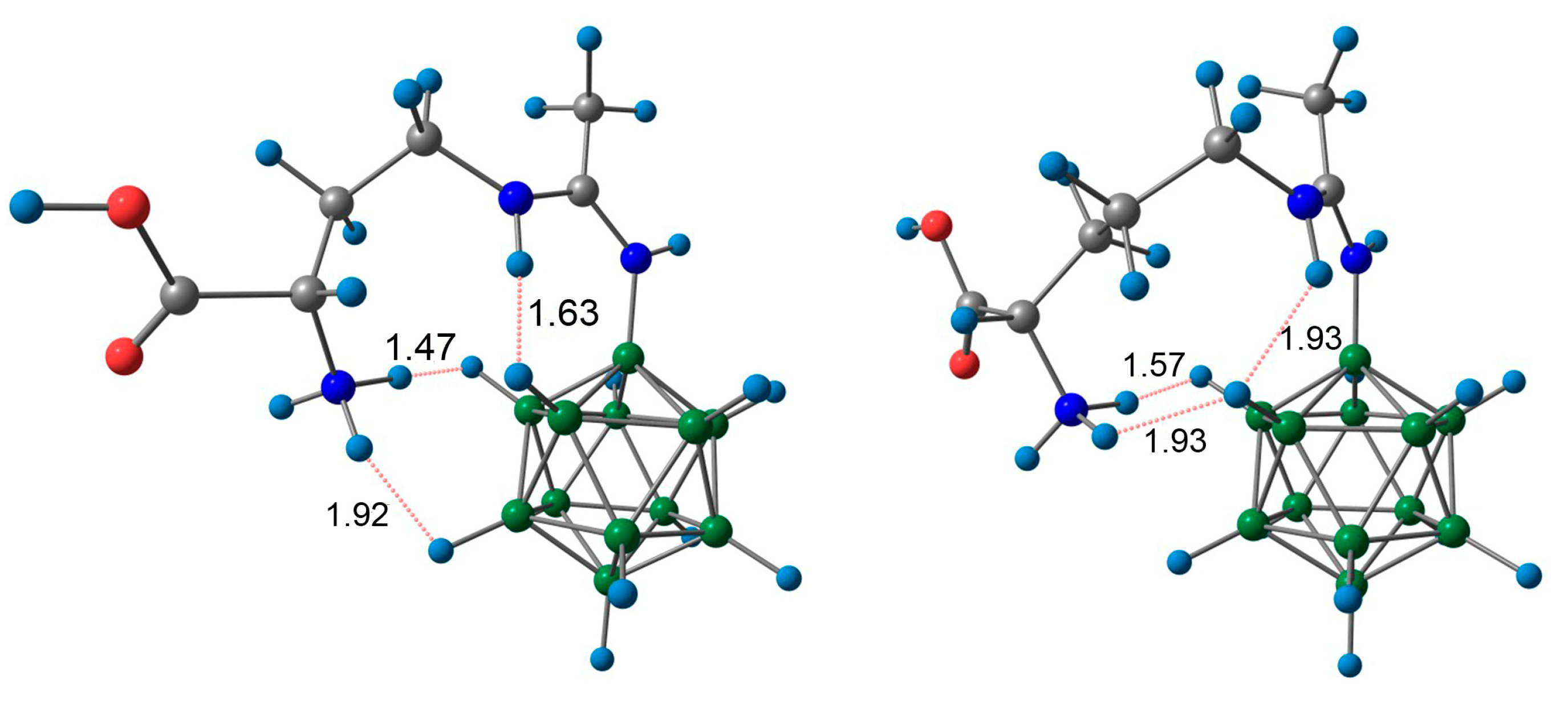

| D-H…A | d(D-H), Å | d(H-A), Å | d(D-A), Å | D-H-A, ° |

| O2-H2...O3 | 0.84 | 1.78 | 2.594(5) | 163.1 |

| N3-H3A...O5 | 0.91 | 1.83 | 2.735(7) | 170.3 |

| N3-H3C...O31 | 0.91 | 2.16 | 2.814(6) | 127.7 |

| O5-H5B...O42 | 0.87 | 1.94 | 2.802(8) | 169.6 |

| O3-H3F...O13 | 0.87 | 2.07 | 2.827(5) | 145.5 |

| O3-H3G...O4 | 0.87 | 1.86 | 2.726(6) | 172.3 |

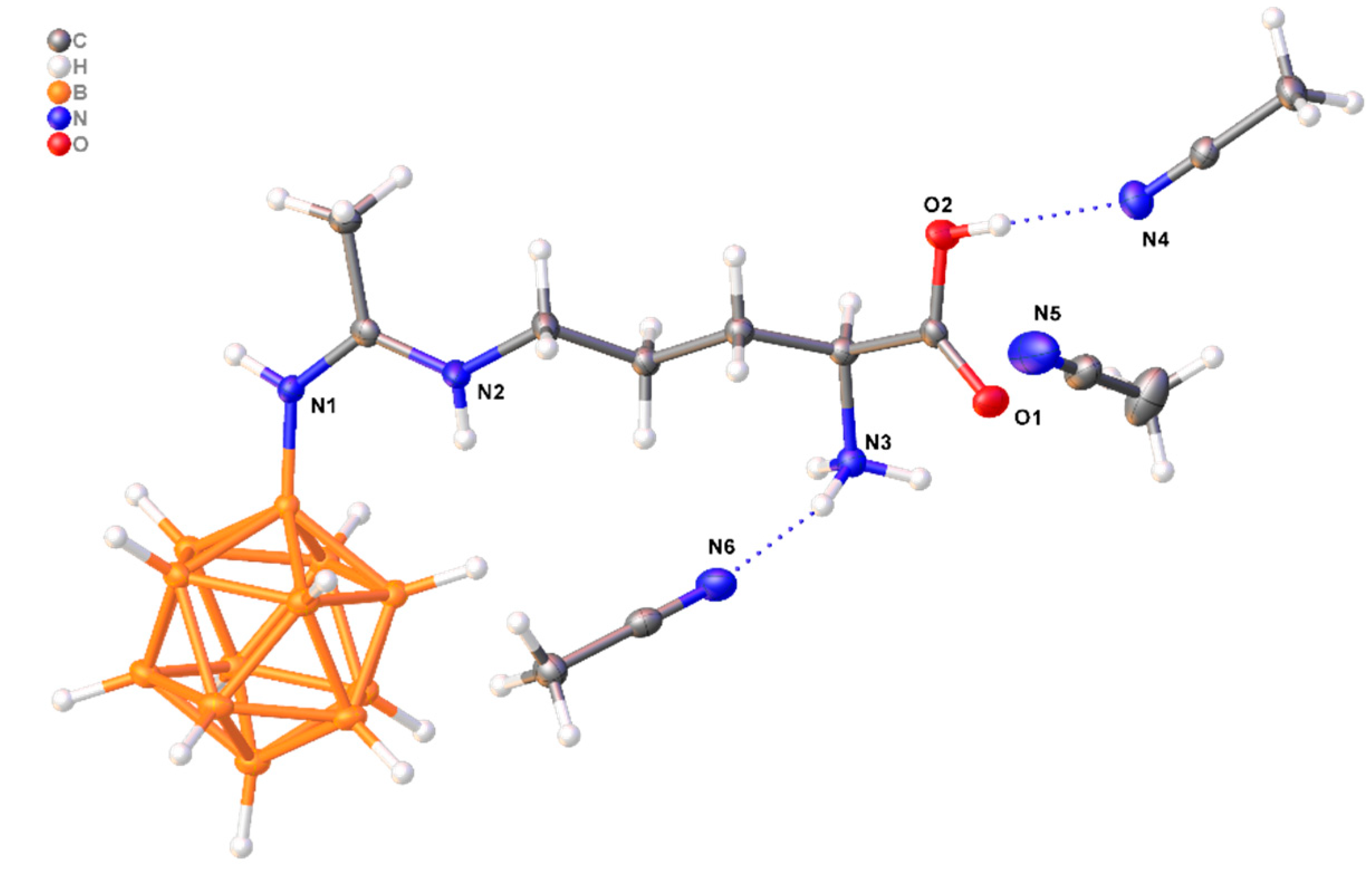

| D-H…A | d(D-H), Å | d(H-A), Å | d(D-A), Å | D-H-A, ° |

| O2-H2… N4 | 0.84 | 1.89 | 2.721(2) | 170.1 |

| N3-H3B… O11 | 0.91 | 2.18 | 2.894(2) | 135.1 |

| N3-H3B… N41 | 0.91 | 2.53 | 3.235(2) | 135.1 |

| N3-H3C… N6 | 0.91 | 2.14 | 3.024(2) | 164.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).