1. Introduction

Conservative global estimates anticipate 2-8% of the world’s children and young people have a level of caring responsibility (Saragosa et al., 2022). In context 3.55 million children living in the UK are currently in their early years (0-5) (United Nations, 2023). Evidence suggests for some young carers, their role is assumed between three and ten years before they are identified (Carers Trust, 2023). Whilst recognition of young caregiving has undoubtedly grown exponentially in recent decades, it is widely acknowledged that young carers are still not identified at the earliest possible opportunities (Ronicle & Kendall, 2011; Phelps, 2020). In the UK, recent household census data identified young carers as young as three years old providing unpaid care in Scotland (Scotland's Census, 2022). Furthermore, prevalence of young carers recognised from the age of four years is evidenced through provision of dedicated young carers services across the UK (Young Carers National Voice, 2024; Carers Trust, 2024). Evidence suggests a 3% rise in prevalence from 8% to 9.8–11.9 % following the COVID- 19 pandemic in analysis of three longitudinal data sets of young carers aged 16-18 years old (Letelier et al., 2024). For many of these young people it is likely that their caring role began in early childhood.

The contextualization of children as caregivers is a complex matter (Joseph et al., 2019; Stevens et al., 2024). The psychosocial impacts of young caregiving have received growing interest in recent years with qualitative research suggested to have reached saturation in some respects (Joseph et al., 2023). Still the voice of young carers in early childhood (YCEC) is seldomly represented in the broader field of empirical research (Medforth, 2022). Particularly the voice of society’s youngest carers (0-5 years). Whilst not limited to the context of young carers, voicing experiences of our youngest children is of fundamental importance (Lawerence, 2022; Correia et al., 2023), both to inform policy and to foster pathways to achieving national and international aspiration for improved young carer identification and support (Leu et al., 2022; Commonwealth Secretariat, 2023).

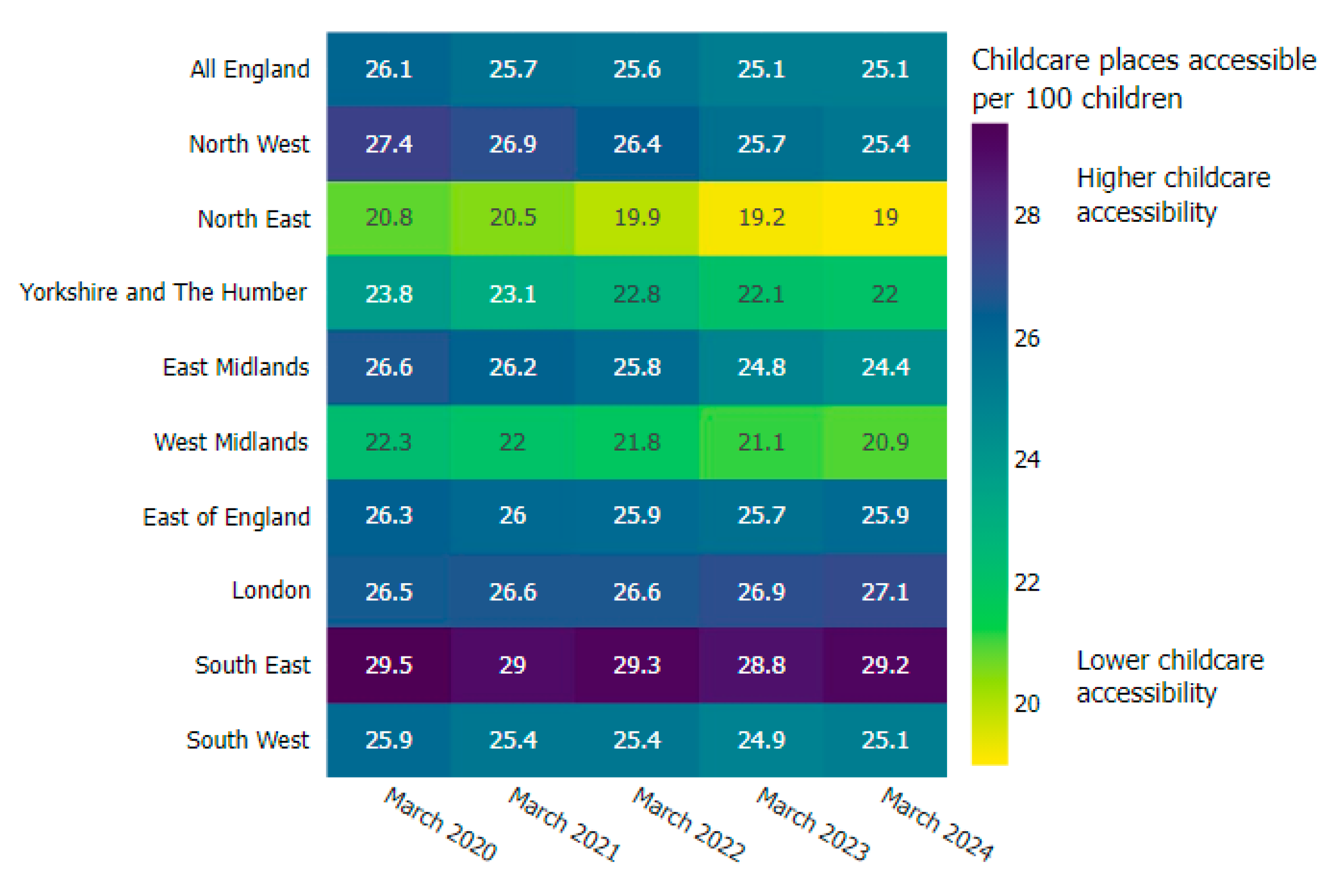

Optimal child development forms the basis on which community adhesion and economic growth are founded to build thriving, sustainable societies (Black et al., 2022). The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), underpinned by the leave no one behind (LNOB) principle (Oehring & Gunasekera, 2024), address crucial factors of poverty, (SDG1), health and wellbeing (SDG3) and education (SDG 4) (UNICEF, 2023). Each having a significant impact upon young carer well-being and life opportunities. Establishing equitable opportunities for YCEC to achieve these goals is of imperative importance, helping to ensure that those furthest behind are receiving support at the earliest opportunities. Importantly, UK-wide investment in the early childhood care and education (ECCE) sector has taken bold steps in recent times to address inequalities. In England, policy seeks to increase access to provision, starting in areas deemed as ‘childcare desserts.’ Evidence indicates 45% of children under the age of five years in England are currently not able to gain access to provision in their local area, as a result existing childcare funding entitlements are less accessible to lower income families; exasperating availability of support to families in need (Ofsted, 2024) (

Figure 1).

Commitment to investment in ECCE is unified across each of the four nations (UK). A report recently commissioned by The Royal Foundation of The Prince and Princess of Wales, business taskforce for early childhood, estimates £45.5 billion of value would be added each year to the UK economy by investing in early childhood (Deloitte, 2024:8). Such commitment is mirrored within the health care system with the Health and Care Act (2022) (Department of Health and Social Care, 2022) prioritising young children’s health and wellbeing within Integrated Care Boards (ICB’s) across England. A visual pathway sets out a vision centering children within the core of all health care provision (

Figure 2) (Children and Young People’s Health Policy Influencing Group, 2024). Its unifying commitment to these promises obligates policy to reflect the vital role the ECCE sector plays within the puzzle of system change concerned with young carer and whole family support. In doing so, professional awareness across the sectors of health and social care and ECCE harnesses the potential to recognise and prevent inappropriate caring responsibility at the earliest opportunity. In addition, strengthening young children’s transition

into primary education where early childhood development continues to be supported; yet outcomes for young carers are significantly impacted in comparison to their non caregiving peers (Leadbitter et al., 2024).

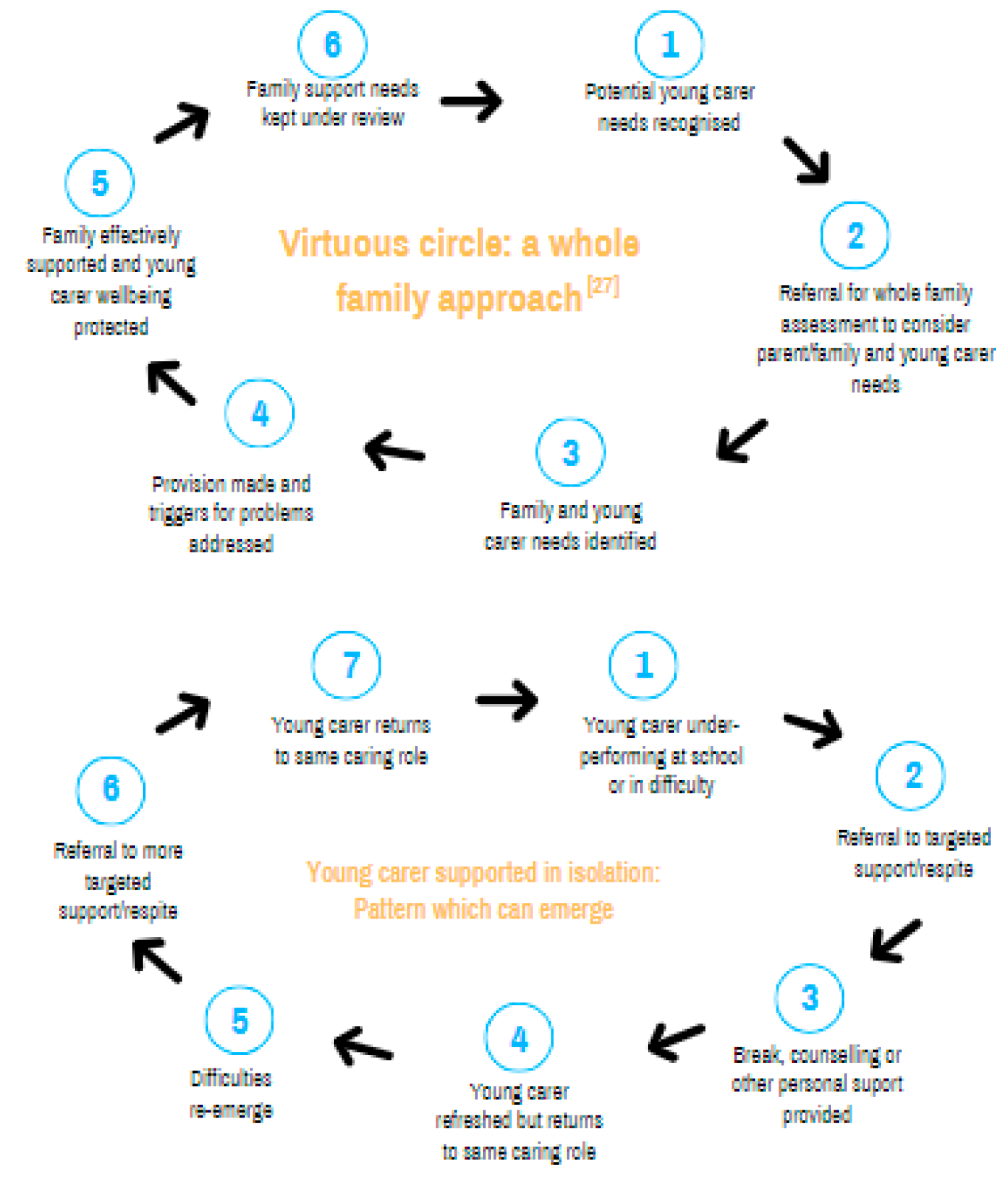

The framing of YCEC in the UK sits within the context of interdisciplinary, whole family support; fundamental to the reduction of negative outcomes associated with the care of another person (Woodman et al., 2020; Yghemonos, 2023) (

Figure 3). Whole family support serves to strengthen the family unit, placing emphasis on growing secure, consistent, supportive relationships (Garner & Yogman., 2021). Aligning with principles of early childhood curricula, attachment theory informs relational pedagogy, fostering a sense of belonging and companionship within child, family, and professional triad’s (Cliffe & Solvason., 2023; Lippard et al., 2017). Developing healthy attachments in early life is therefore central to the moderation and reduction of childhood stress and associated biopsychosocial outcomes in later life (McWayne et al., 2021; Davidi, 2023; Fayazi et al., 2020).

When child-caregiver relationships become fractured, a ripple of insecurity, discomfort and compromised feelings of safety extend throughout the ‘nested structures’ which encompass the child’s unique lived experience (Bronfenbrenner, 1979:3). In this regard, successful support, and intervention through adoption of a ‘virtuous circle model’ (

Figure 3) takes account of a child’s wider sociocultural ecosystem. As such fostering companionship and helping to reinforce mutually resilient attachments in early childhood and beyond.

O’Dea & Marcelo (2022) discuss the experience of caregiver support in the broader context of caregiving amongst adult populations. Importantly they warn that having support accessible throughout the layered systems of education, health, social care, and wider community contexts, does not necessarily mean carers feel supported. Concurring with Ellicott et al. (2024) that ‘think family’ approaches, whilst advocated within social policy, are yet to be fully adopted consistently into practice (Woodman, et al., 2019:21). To address this, Lindley (2023:264-277) argues for a ‘National Children’s Service’ which would place whole family systems at the core of all service delivery. Mirrored by ideals set out by Carers Trust (2024) recently updated ‘No wrong doors for carers’ memorandum of understanding, accountability for the identification and support of young carers (and their family’s) therefore sits at the door of all health, care, and education professionals, including the ECCE sector, service commissioners and strategic leads. Entwined whole family systems thus serve to mitigate isolation, not only for the child and their family, but of organisations working in silos.

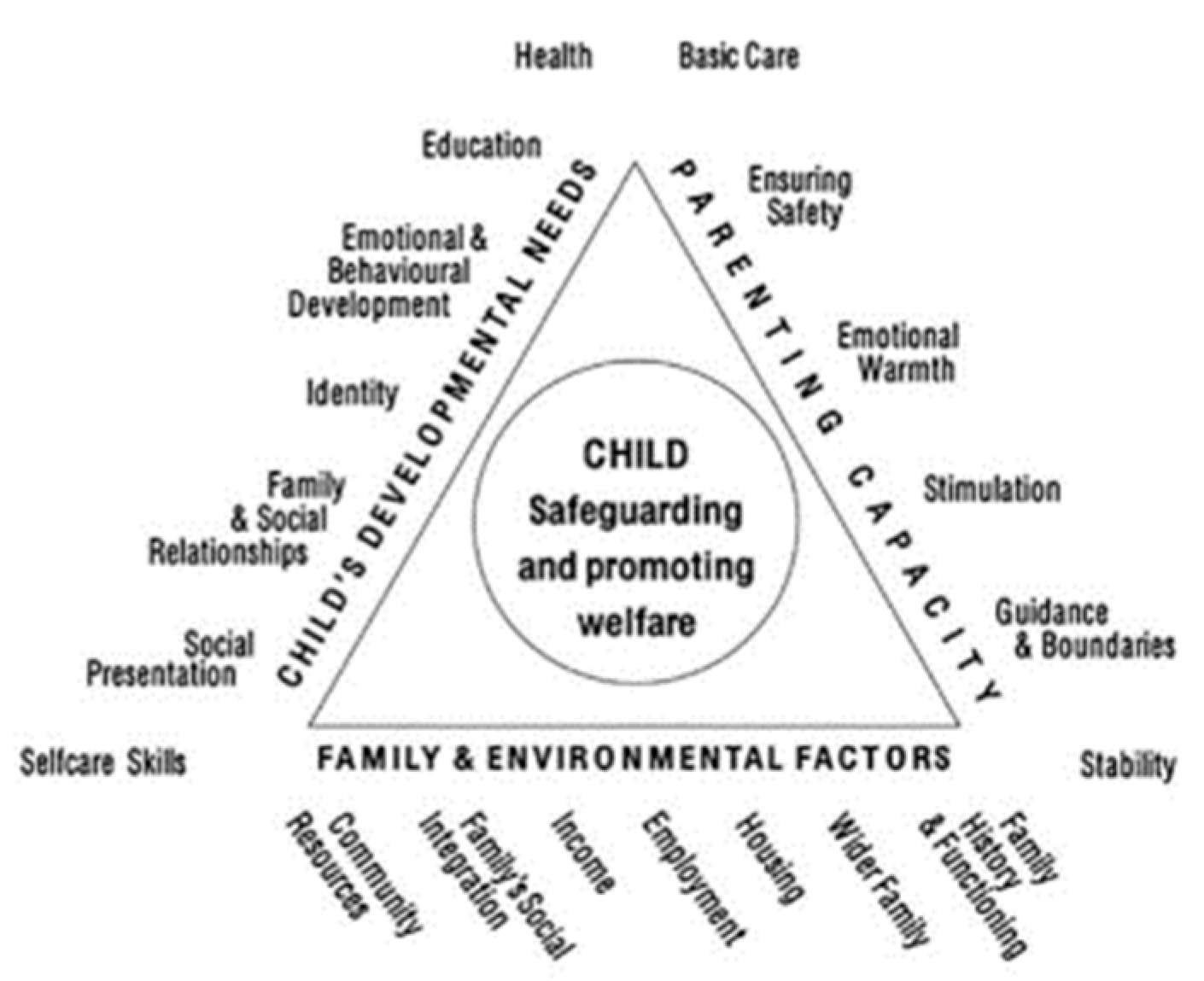

Young carers (including children who may become young carers) within the UK have a right to voice their experience and have their needs assessed. These rights must be protected in the context of safeguarding and equitable opportunity for all young carers (Baginsky et al., 2020; Gowen et al., 2021; Lätsch et al., 2023). Drawing examples from practice in England, the ‘Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and their Families’ (Department of Health, 2000) served as a guiding compass for all assessments under the umbrella of the Children Act 1989 (Gov.UK, 1989) (as modified by the Children and Families Act 2014) (Gov.UK, 2014). The framework (

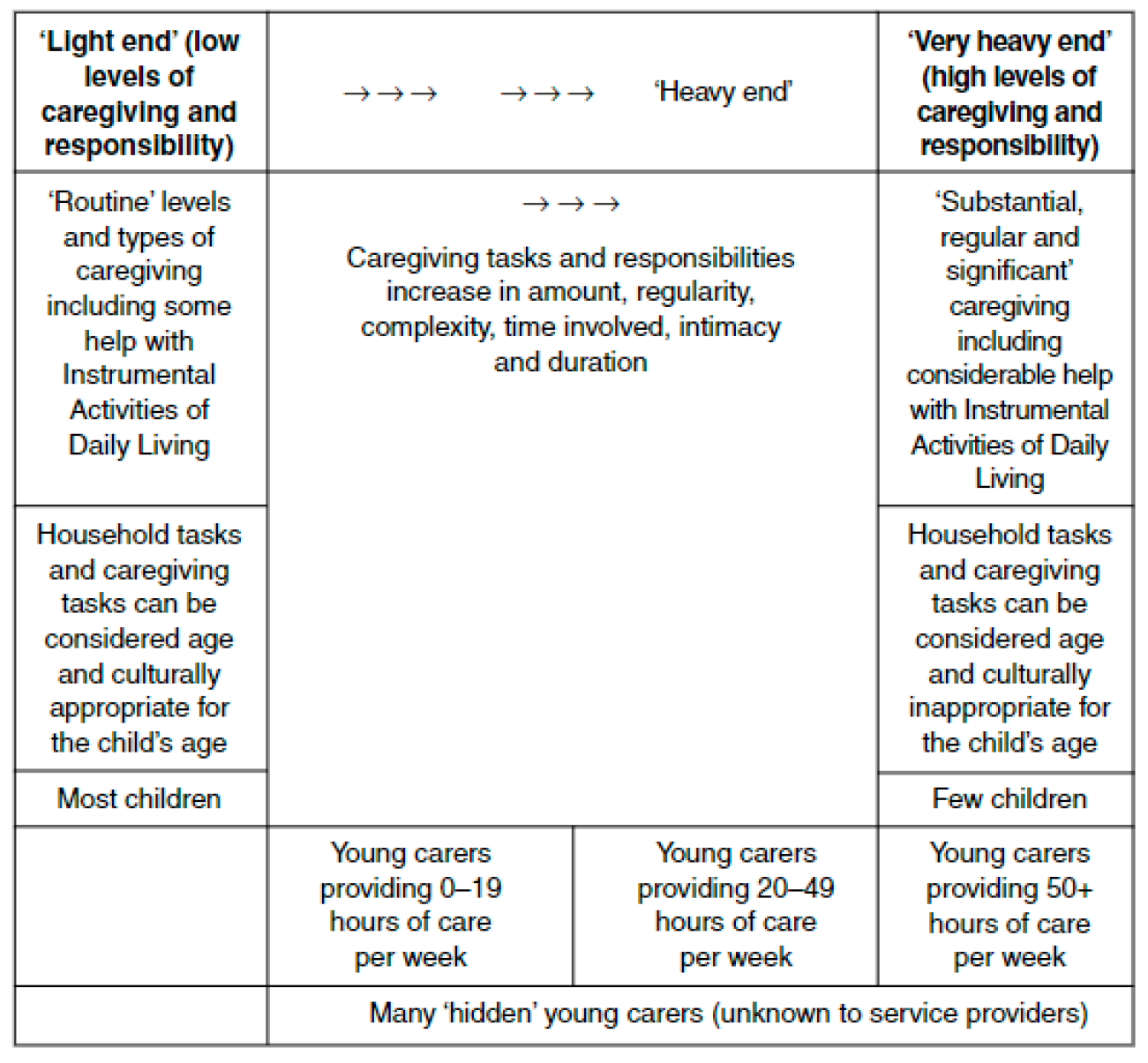

Figure 4) provided a foundation on which the core tenant of social work practice has developed. Helping to illustrate the point within a ‘continuum of care’ in which experiences of care giving may become inappropriate (Becker, 2007:33) (

Figure 5).

Subsequent documentation throughout the UK reflects modern principles of safeguarding needs in guidance. Working Together to Safeguard Children (Department for Education, 2015:2024), Keeping children safe, helping families thrive (Department for Education, 2024c), Working Together to Safeguard People (Welsh Government, 2022), Co-operating to Safeguard Children and Young People in Northern Ireland (Department of Health (NI) , 2024), National Guidance for Child Protection in Scotland (Scottish Government, 2023) and Getting it right for every child (GIRFEC) (Scottish Government, 2022).

These documents help to conceptualise risk within Jospeh et al’s. (2019:84) conceptual concentric circle model of young caregiving. This illustrates the interplay of ‘caring for,’ ‘caring about’ and the need of ‘care for’ young carers themselves. Its application is crucial in the development of preventative strategies offering whole family support and intervention.

In these contexts, understanding young carer’s early development may help to ‘untangle’ (Joseph et al., 2019:77) the dichotomous complexity of empowerment and risk associated with young caregiving. The multifaceted nature of caregiving experience can in some cases foster resilience (Boyle, 2020; Gough & Gulliford., 2020). In contrast young carers face significant risk and emotional strain (King et al., 2023), poor physical and mental health (Lacey et al., 2022; Fleitas Alfonzo et al.,2022; King, Singh & Disney., 2021) and compromised educational outcomes (Brimblecombe et al., 2020; Carers Trust, 2024; Kettell, 2018; Leadbitter et al., 2024). This complexity underscores the need for a nuanced understanding of individual circumstance, developmentally appropriate contexts, and recognition that in some cases empowerment and risk may coexist, influencing one another profoundly (Masiran et al., 2023). It is important to recognise that trauma itself is a socially rooted construct (Lannamann, & Mcnamee., 2019). As such, professionals undertaking assessments of need must refrain from viewing the experience of YCEC through a subjectively informed lens of broader YC understanding.

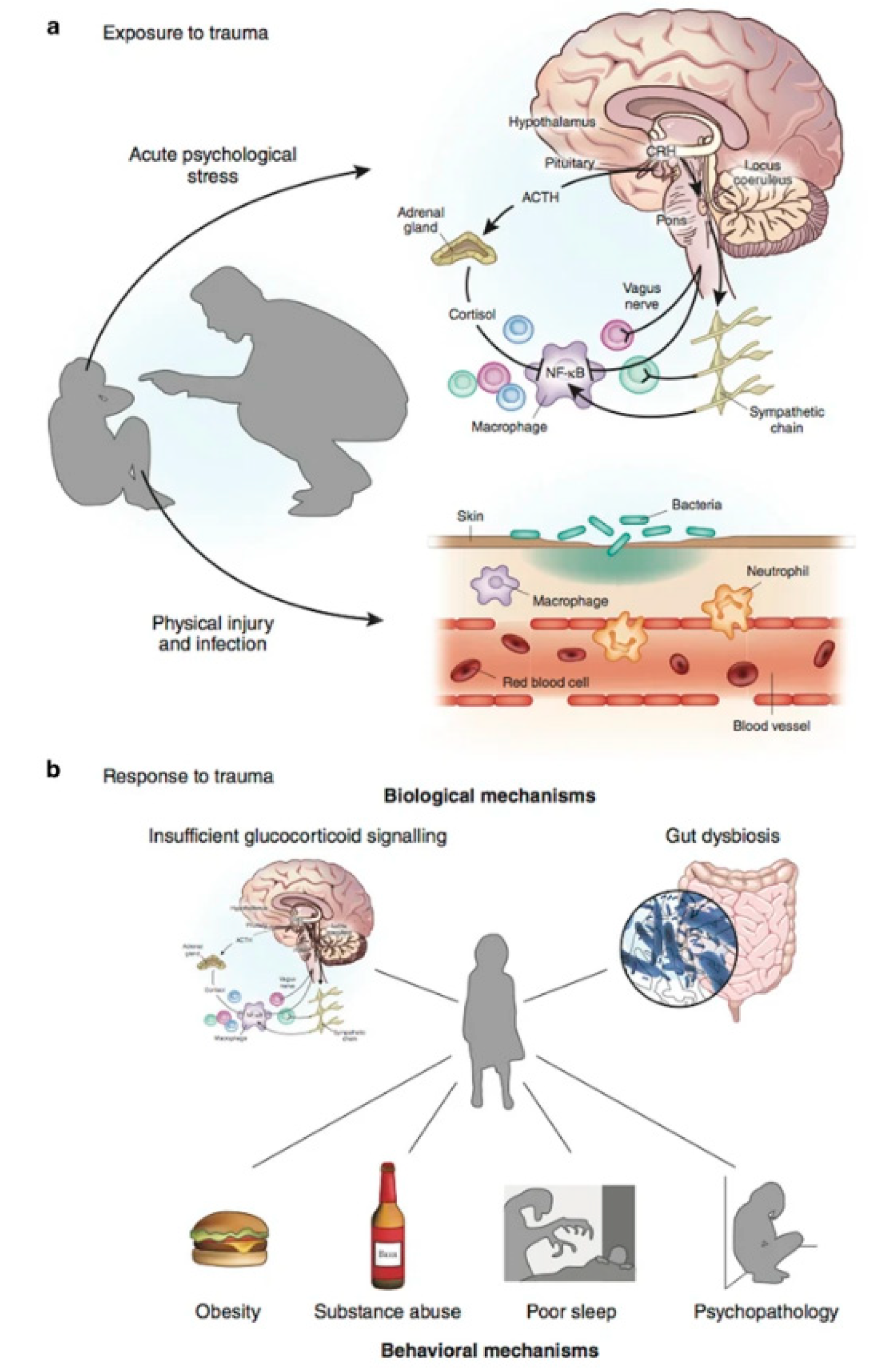

Early childhood development lays the foundation on which all human experience is shaped (Richter et al., 2020). A life course perspective is therefore imperative to inform multidisciplinary practice concerned with prevention of inappropriate caring responsibility. Such perspective gives insight to mitigating risks of associated biopsychosocial factors resulting from adverse childhood experiences (ACES) (Felitti et al., 1998; Gilgoff et al., 2020; Spratt et al., 2018). Danese & Lewis (2016:108) describe early life stress as ‘hidden wounds’ of early childhood, contributing to poor health and mental health outcomes. Gabor Mate (2021) further explains that ‘

trauma is not what happens to you, it is what happens inside you’ (Triesman, 2021:22). In this context, psychoneuroimmunology (PNI) (

Figure 6), advances understanding of the relationship between the nervous system, psychological processes, and their effect on the immune system, strongly making a case for deeper enquiry of early life experiences of young carers robust.

Walker et al’s. (2024:8) systematic review of young carer experience in Australia notably contextualizes the occurrence of being ‘born into caring’ as a distinct theme for analysis. Janes et al. (2021) revisited past research in the context of psychosocial health. Their review concludes the need for future research to engage with young carers of all age ranges, including those not already known to local authorities. Lacey et al. (2022) implores the need for longitudinal studies which explore more deeply cause and effect within young caregiving relationship and wellbeing outcomes. Further supporting the argument for greater focus on being and becoming a YCEC and the wider biopsychosocial implications of such across the life course (Ornstein et al., 2024).

Prevalence: Growing prevalence of YCEC in the UK is evident with reports illustrating increased awareness. For example, The Department of Education (DfE, 2016) reported an 80% increase in England in the identification of young carers aged between five and seven years between 2001 and 2011. Whilst incidence rates are thought to be underestimated, a further increase is evident between 2011 and 2021. Carers Trust (2023) reported 3000 YC aged between five and nine years spending at least fifty hours per week taking care of another person in England and Wales. In Northern Ireland 1,932 children aged between five and fourteen years were providing up to 19 hours of care per week, with 316 providing more than 50 hours of care per week (NISRA, 2021). Furthermore, census data for Scotland recognised children as young as three years old having caring responsibilities (Scotland's Census, 2022). Notably Scotland being the first nation in the UK to formally make provision to record children under the age of five years as caregivers within household Census data.

Summary: Early childhood offers a critical window of development affording a significant opportunity for early identification of risk to take place. Understanding concepts of caring and childhood in this context helps to address the ‘invisible vulnerabilities’ of being and becoming a YCEC (Yuan & Ku., 2024:7). The sharing of stories gives power to the young carer community, creating the potential for reciprocity (Dove et al., 2021). Stories of experience help triangulate our understanding of prevalence data and quantitative research. Furthermore, understanding the perspectives of very young carers holds the potential to offer compelling insight to the broader field of mental health prevention, support, and intervention.

Aim: This scoping review is an initial step in quilting together a polyvocal investigation of YCEC (Ortega et al., 2023). The review is presented as part of a programme of PhD research undertaken by the lead author. It is intended to map the current knowledge base concerned with the lived experiences of the youngest carers in the UK. The objective is to create a step change in perceptions of young caregiving. This serves to better inform future developments of policy and practice in relation to possible mitigating factors concerned with early familial relationships and attachment.

With commitment to reducing research waste, the focus of this review centers on the qualitative representation of YCEC aged between birth and five years in the UK.

Definition in context: Global typology of young caregiving is not categorised by a single unified definition. Mutual understanding views young carers as any child or young person under the age of eighteen providing or intending to provide care to another person with an illness, addiction, disability, or mental health condition.

“Young carers in every country look after someone in their family who has an illness or a disability or other condition. Sometimes they look after the whole family. Young carers are children and young people first and should be free to develop emotionally and physically and to take full advantage of opportunities for educational achievement and life success” (Commonwealth Charter for Young Carers, Commonwealth Secretariat, 2023:1).

In the United Kingdom (UK) ‘Young Carer’ is used unanimously within legislation in England, Children Act 1989 (Gov.UK, 1989) as modified by the Children and Families Act 2014 (Gov.UK, 2014); Health and Care Act, 2022 (Department of Health and Social Care, 2022), Scotland (The Carers (Scotland) Act 2016) (Gov. Scot, 2021), and Wales (The Social Services and Well-being (Wales) Act 2014) (Legislation.gov.uk, 2014). Young carers are recognised in Northern Ireland under a broader definition of children in need, with ‘Young Carer’ used within practice guidance (Action for Children, 2024; Barnardo’s, 2024). Legislation throughout England, Scotland and Wales embeds the right for all children and young people, regardless of age to an assessment of need. Northern Ireland enacts this right through the Children (Northern Ireland) Order 1995 (Legislation.gov.uk, 1995).

Early childhood is globally typified as the period from birth to school entry, which varies across the world (EECERJ, 2023; UNICEF, 2018). In the UK infancy, early years and early childhood are overlapping constructs with distinct age ranges within the concept of early childhood. In this context three intersecting, yet distinct, developmental constructs exist. Infancy, the period from conception to the age of two years (Burlingham et al., 2023) and early years and early childhood, which are used interchangeably to describe young children aged from birth to five years (Boyd & Hirst, 2015; Bradbury, 2018). In the context of this review, and with commitment to reduce research waste (Joseph et al., 2023) the focus centers on the representation of YCEC aged from birth to five years (Black et al., 2017).

Review questions: How are Young Carers represented in broader literature and what factors influence dominant representations of Young Carers in Early Childhood in the UK?

2. Design and Search

2.1. Design

This Scoping review has been undertaken in accordance with JBI guidance for scoping reviews (Pollock et al., 2023). A preliminary search of JBI Systematic-Review-Register (JBI, 2024) was conducted and no current or underway systematic reviews or scoping reviews of the specific topic were identified.

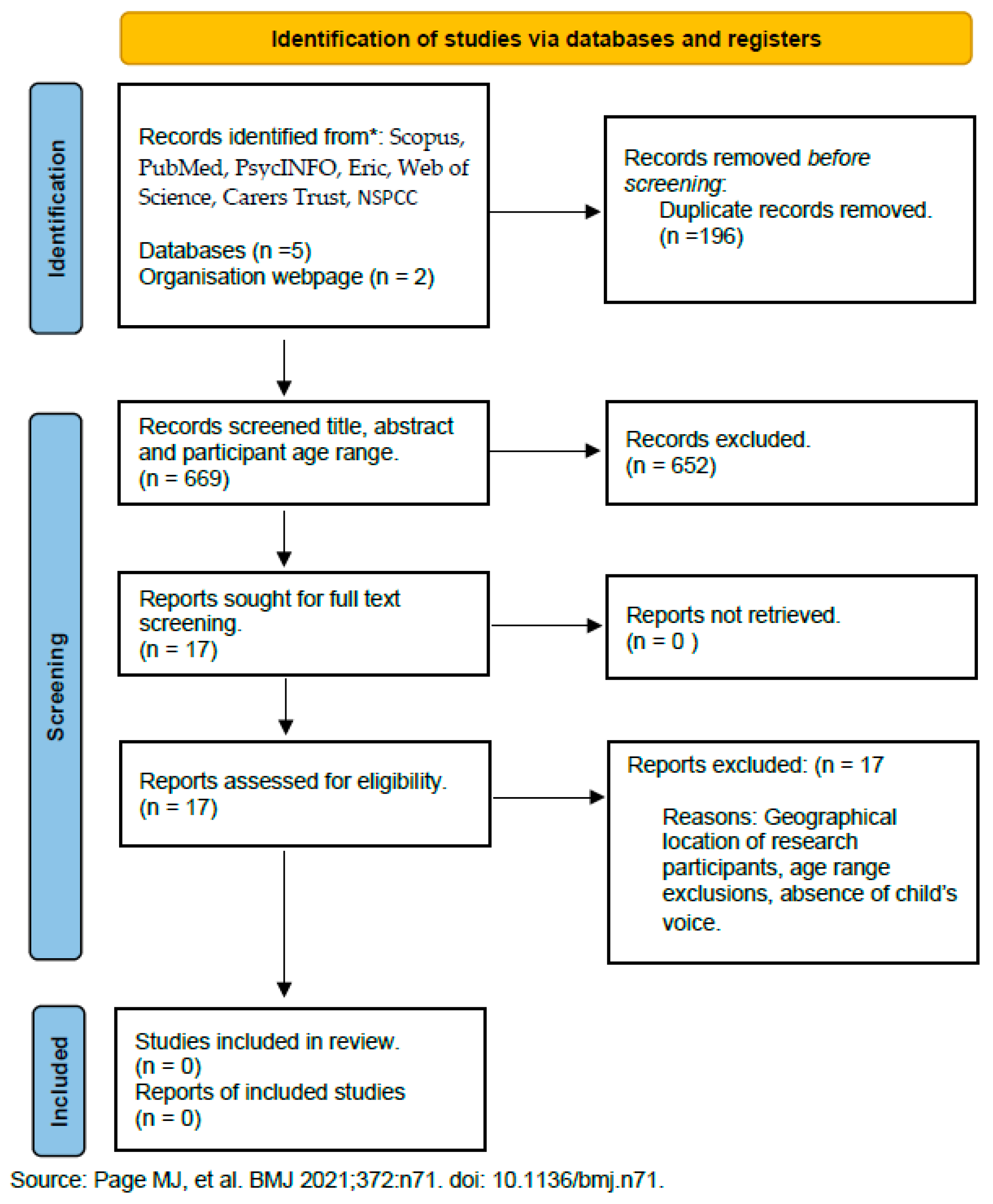

A priori protocol was developed and published (Systematic-Review-Register - Systematic Review Register | Joanna Briggs Institute, 2024-02-29) entitled ‘Young Carers in Early Childhood - Scoping Review’. The lead author has adhered to the PRISMA-ScR checklist for scoping reviews (Tricco et al., 2018). The PCC Participant, Concept, Context approach defined the eligibility criteria in relation to participants. This defined the age of young carers included in studies (0-5 years), the definition of a young carer and the location of young carers. In this case qualitative studies that were conducted with participants from the UK only.

2.2. Search

The search strategy was devised in consultation with knowledge users and a library information specialist to define clear, succinct search terms. Examples of key words and phrases include ‘Young carers,’ ‘Early Childhood’ and ‘Lived experience.’ Key words and controlled vocabulary were utilised to manually adapt the search strategy for online databases. These included publications dated 2014-2024 in Scopus, PubMed, PsycINFO, Eric, Web of Science, and the Carers Trust and NSPCC websites. Manual searches of reference lists, including past systematic reviews concerned with young carers were undertaken. Articles were imported to Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., 2016). Duplicates were removed before screening.

An independent reviewer screened 10% of all articles including title, abstract and participant age range where indicated in methodologies. Full text screening proceeded with a further 10% screened by the same independent reviewer. Any conflict arbitrated by the lead author in consultation with Knowledge user representatives, by refereeing to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Results were discussed with knowledge users at all stages of the review process, including defining the aims, sharing articles for consideration and conclusion of results (Pollock et al., 2022). Eligible sources for inclusion included peer reviewed primary research articles and internet searches of grey literature. Exclusion criteria omitted articles where samples were indivisible by age (e.g., “Participants ranged in age from 5 to 12 years”) or the age range of participants are not specified. Opinion pieces and local service data were excluded. Relevant systematic reviews were pearled for any additional eligible articles within reference lists, not captured by the original search.

3. Results

A search of Scopus, PubMed, PsycINFO, Eric, Web of Science databases, and the Carers Trust, NSPCC, yielded 865 articles, imported to Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., 2016). After removal of duplicates, 669 remained and were subject to title, abstract and population screening. 10% of which were blind screened by an independent reviewer. After excluding irrelevant articles, 17 full text articles were retrieved for full text screening of which 10% were screened by the independent reviewer. Of these, 8 serious case reviews (SCR’s) were screened from the NSPCC database. The results were discussed with knowledge users to reach a final agreement.

A comprehensive search of the literature yielded no studies which met the inclusion criteria for this scoping review. The exception being a yet unpublished master’s degree dissertation (Ellicott, 2023), entitled ‘Capturing the ontology of young carers in the early years -Threads of hope through lived experience’. This work has not been included due to the ongoing nature of the research. The work explored the lived experience of two families, each centering on a young carer aged four years old. As the work has yet to be subject to peer review it has been excluded in this instance. Other studies were excluded due to the specified age range criteria and the geographical area of research participants. The absence of relevant research highlights a significant gap in knowledge regarding the way in which the lived experiences of young carers in early childhood are represented and understood.

4. Narrative Analysis of Excluded Findings:

Themes observed during the screening process are discussed within this narrative analysis of excluded articles and broader representations of young carers. Concurring with Janes et al. (2021) existing empirical research presents subjective outputs. Participants within research are mostly already known to services. As such participant age range is dominated by experience of children grouped within age ranges of 5-18 yrs., with greatest representation of those aged 7-18 yrs. (Chikhradze et al., 2017) (in the context of childhood). As a result, outputs lack the voice, developmental and pedagogical perspective of YCEC.

This highlights a compelling need for further research specifically concerned with YCEC originating from all disciplines. Furthermore, research informed guidance is required to develop policy and practice to further represent the voice of YCEC. This is particularly needed in the contexts of whole family support and for local authorities wishing to reach and engage with young carers who may be viewed as more challenging to serve.

Advice and guidance: Limited research and guidance was found to be available to support service provision with assessing and meeting the needs and transitions of YCEC. Whilst independent documentation is often available within local services, only one overarching document was found, and consistently recommended to the lead author by knowledge users (Carers Trust, 2015). The guidance was excluded from the review due to age range exclusion and revisions made by the regulatory body in England since publication (Ofsted, 2019). A resource pack for schools aimed at the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) and key stage 1, produced by Caring Together (2020) provides some practical support and activity ideas for schools, but refrains from voicing the experience of the YCEC in broad developmental terms relating to the EYFS fully (0-5 yrs.) (Department for Education, 2024b).

National organisations offering effective awareness training to education providers throughout the UK do not yet extend that guidance specifically to the ECCE sector (for example, Carers Trust & The Children's Society, 2022). Provision of targeted Young Carer support is itself variable across the UK. For example, some local authorities endorse a whole age model of delivery whilst other parts of the UK offer tailored support to young carers from predetermined age ranges (Young Carers National Voice, 2022; Carers Trust (Young Carers Alliance), 2024).

Where policies and support systems fail to fully capture the full age range of young carers, a distorted representation influences prevalent narratives. Phelps (2017) noted the importance of voicing society’s most vulnerable young carers, noting stories should not be obscured by those more commonly represented. As a result, information sharing between the ECCE sector and primary schools regarding vulnerabilities are not well informed, nor do they share the common language of ‘Young Carers’ to better recognise YCEC upon transition into primary school. Consequently, opportunities are sometimes missed by professionals to identify very young children who are, or are likely to become, young carers at the earliest opportunity. In addition, there is little evidence of professional engagement across disciplines to consider the barriers to identification and support for YCEC.

Defining the age of assessment and support: Gibson et al. (2019) acknowledge young carers from birth and highlight the undertaking of assessment may come from all professionals concerned with a family, including an Early Help Assessment in England. Correctly observing there is no lower age limit to an assessment of need in the context of young carers. However, it was noticed during screening exercises that legislative frameworks are at times misrepresented in literature. For example, Darling et al. (2019:532) and Waters (2019:1) insert age limitations when reporting legislation pertaining to the protection of young carers rights. Incorrectly creating exclusion criteria to the early identification of YCEC. As such, decision makers are not as well informed to recognise YCEC as they could be, feeding narratives of implicit bias towards families where young children provide care to another person. Such misrepresentation is unhelpful when setting commissioning priorities, contributing to a postcode lottery of support across the UK (Medforth, 2022). Furthermore, discussion regarding the purpose of early help and family support strategy more broadly highlights the need for greater service evaluation. Particularly concerning the modus operandi of young carers support services in the broader sphere of family support, which most commonly seek to intervene when problems already exist, rather than preventing crisis from occurring (Webb, 2021).

Language and terminology: In 2016 a report from the Office of the Children's Commissioner for England made a commitment to better understand the experience of society’s youngest carers (Children's Commissioner for England, 2016). The report prompted advocacy for greater focus on identification and support for YCEC, up to and including children aged 8 years. Pathways to identification and assessment of YCEC were viewed through a lens of safeguarding, with the report suggesting services were not able to support the needs of young children, due to lack of investment. Caregiving in this context was defined into three categories, ‘minimal,’ ‘low-level’ or ‘excessive.’ As such YCEC were considered to be children in need (Gov.UK, 1989) or placed in the care of social services. Local tabloids sensationalised the report with headlines of ‘stolen childhood’ labelling YCEC as infant carers, feeding narratives of adult centric views of young caregiving (News, 2016). Infancy in the developmental context of early childhood is defined as the period from gestation up to 2 yrs. (Burlingham et al., 2024). As such barriers may have prevented societal acceptance of YCEC as providers of care incomprehensible. Instead, greater collaboration of cross policy initiatives could be developed to improve support for families during infancy, including pre-birth assessment and post birth support throughout early childhood. Current research offered by Burch et al. (2024: 23) has found that in two hundred recent care proceedings concerned with infants under twelve mths, 34% involved a parent with ‘learning disabilities or learning difficulties’. Cooccurring risk factors included substance abuse, mental health, and domestic abuse, raised by professionals. Long-term, whole family support in this context is necessary to mitigate the risk of children being taken into care, and to provide more targeted support for those families where the care of another person is most likely to be provided, in some way, by the child. As such making the case to extend professional awareness training concerned with young carers, to all professionals responsible for the health, care and education of children and their families in a child’s early years.

There are long standing arguments, of course, which view definitive terminology as problematising childhood (Fives et al., 2019; Olsen, 2000). This argument, in the context of young carers, is countered by Joseph et al’s. (2023:44) concentric circle model, helping to address the nuances of young caregiving. The model offers opportunity to reframe resistances to labelling YCEC or viewing young carers as a homogenous group. Saragosa et al. (2022) suggest broader age group representation in the context of young adult carers is a result of sociodemographic changes. Further research is needed to understand such changes in relation to caregiving identified in early childhood. Additionally, research is required to understand society's perception of young carers in the context of early childhood.

Safeguarding: In recent years serious case reviews (now called Child Safeguarding Practice Reviews (CSPRs) in England) concerned with young carers have highlighted notable factors requiring further exploration in the context of YCEC. The NSPCC (2021) published a report highlighting a lack of safeguarding training amongst early years staff, lack of robust policies and procedures of which staff must comply with and implement in practice. Where concerns about children were raised, these were not consistently, nor appropriately, shared. Of greatest pertinence to YCEC, where support needs of families were recognised, staff failed to fully acknowledge the impact of such on parenting capacity. Too often ECCE settings do not receive vital information from other services involved in family support and as a result professionals are not well informed of a child’s unique history and wider social environment. Consequently, early years practitioners are not always well informed to protect children or to prevent risks that were otherwise known. The report makes clear recommendations which advocate for ‘professional curiosity’ in all cases, imploring the sector to ‘build up a picture of a child’s lived experience and show curiosity about their life outside of the setting, such as their home environment and family relationships.’ NSPCC (2021:4). Poor understanding of lived experiences in early childhood, in the context of young caregiving creates barriers to having experiences and needs heard and understood. As a result, insufficient recognition of family history inhibits assessments which must consider the cumulative impact of factors associated with young caregiving. Where needs are poorly understood, application of thresholds within Early Help, child in need assessments and family support strategies are brought into question (Children’s Commissioner for England, 2024). Particularly when young carers are exposed to multiple risk factors concerned with caregiving, including a ‘trigger trio’ of risk defined as parental mental health, addiction, and exposure to domestic violence (Bennett et al., 2024).

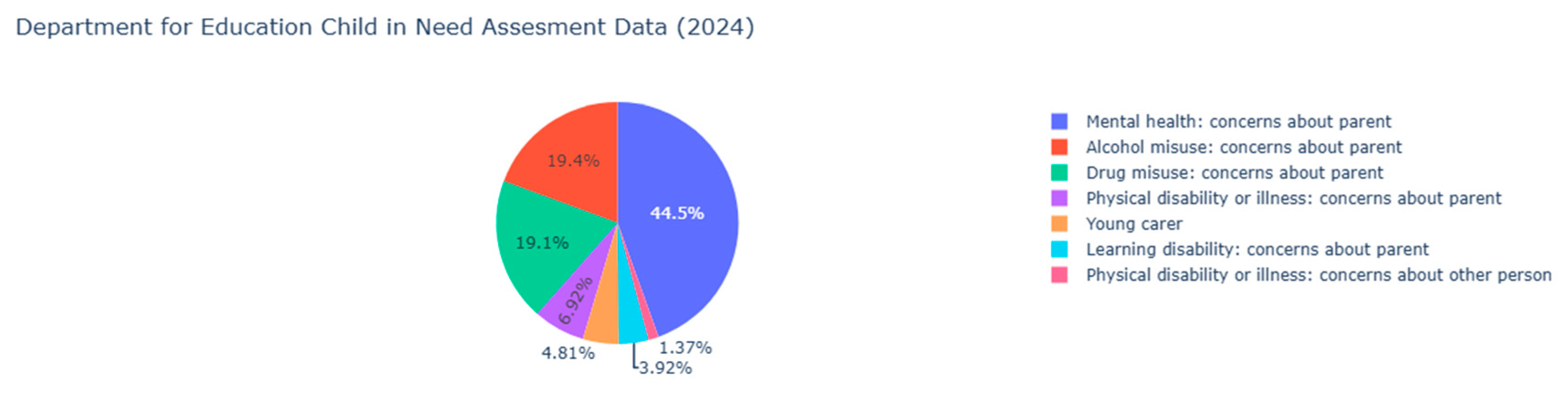

A preliminary search of serious case reviews (SCR) available on the NSPCC database provided explicit examples of too little, too late. Young carers were identified as an outcome of a SCR, but not always by those professionals involved in the care and support of the child/ren and their families leading up to the review. This highlights a significant lack of awareness and understanding of young carers in cases of children in need. For context, one in every thirty children in England are reported to be children in need (Department for Education, 2023). The following graphic, (

Figure 8.) helps to illustrate the current percentage of children on a child in need plan in England, and the factors of concern regarding a parent or other person. The percentage of children identified as young carers is marginal, furthermore this figure has decreased by -0.80% since 2023, despite incidences of child in need plans increasing overall.

Furthermore, 22% of all children in Northern Ireland face severe hardship (Eurochild, 2022), 20% of children receiving care and support in Wales are under 5 years old (Gov.Wales, 2024) and 24% of all children in Scotland are living in poverty (Dickie, 2023). These multiple hardships faced by children in the UK are further exemplified when caring responsibility is left undetected. Furthermore, the Safeguarding Practice Review Panel (Gov.uk., 2024;74) suggests the lack of whole family approaches to assessment of need can lead to subjective views towards individuals and risk. Subsequently, when vulnerabilities are viewed in isolation, the person of focus is often seen as ‘the risk’ rather than that person and all family members concerned ‘being at risk.’ As such, current methods of assessments are, at times, failing to protect young carers and the rights afforded to them. Little consideration is given to the power that operates in a family’s life and the subsequent threat presented by such (Johnstone & Boyle, 2018). Future assessments should provide ‘broad and holistic’ considerations of need which are meaningfully centered on the ‘voices and lived experience of all relevant children (those subject to support and protection as well as other related children in the family)’ (Safeguarding Practice Review Panel., Gov.uk., 2024;78).

Other risk factors concerned with outcomes from SCR/CSPRs involving young carers, noted exposure to suicide, exposure to bereavement, failings of professionals to acknowledge a child’s family history, and a culture of failing to adhere to evidenced based practice, (for this reason local practice guides have been excluded from this scoping review in the context of YCEC). Where children and young people were recognised as young carers, mental health and primary health care services failed to recognise the significance of their vulnerability. Tragically resulting in cases of young carers dying by suicide, and/or neglect, or being placed into the care of the local authority. A child’s voice should unarguably be central to all assessment and information concerning the needs of a family. Evidence strongly indicates this is not consistently the current case for YCEC.

In summary, research screened as part of this process has been largely led by experts outside the field of ECCE. Key empirical research regarding the assessment of young carers has yet to include the informed developmental perspective of YCEC in successful models (Ellicott & Woodworth., 2024). As a result, framing of experience has led to a technocratic approach to young carers policy which may benefit further from crucial pedagogical exploration (Simpson et al., 2017). ECCE is one of the UK’s vital public services, regarded as a foundation within society alongside education, social care, and health (Heintz et al., 2021). A fundamental bedrock of whole family support deserves better inclusion in broader narratives of young carers' care and education. In doing so, the UK will be initiative-taking in leaning further towards a goal of achieving improved levels of response for all young carers, continuing to explore the voice of childhood in its entirety. This will help to broaden “extensive awareness at all levels of government and society of the experiences and needs of young carers.” Jospeh (2019:81) and assist in ensuring that future assessments of need reach those who are currently left behind (Oehring & Gunasekera, 2024).

4.1. Implications for Research:

To address knowledge gaps identified in this review, recommendations for further research concerning the voice and experience of YCEC are made. Research concerned with young carer visibility within society should be constructed in the context of spaces and places YCEC encounter, including the early childhood care and education sector. This would support the development of whole systems approaches which foster prevention, and where appropriate, sustained support throughout the life course (Farooq et al., 2024). Consequently, aiding earlier awareness of young carers, broadening young carer narratives, and furthering policy and practice developments in the UK to support systems change in the future (Leu et al., 2022).

4.2. Limitations:

This scoping review is positioned within the context of UK society, legislation, and policy. As a result, the review is presenting a Eurocentric position. Consequently, the review may not be generalisable to broader international comparison (Emmott & Gibbon., 2024).

The concept of parentification was understood as a known risk and consequence of young caregiving, therefore the subject was not explored explicitly within this review but recognised in the context of perceived inappropriate caring and protecting a child’s right to care. For further information Dariotis et al. (2023) have undertaken a comprehensive systematic literature review of the subject, Hendricks et al. (2021) conducted a parentification concept analysis amongst young carers, and Sharpe (2024) whose thesis explored ‘Parentification: Identifying Young Caregivers at Risk’ is recommended.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review sought to assess the extent of literature specifically concerned with the lived experiences of YCEC. The authors highlight a gap in research concerned with voice and representation of YCEC, in the UK. Whilst challenges are presented, understanding early childhood development, and particularly early attachments and companionship in all young carer’s lives could help better inform assessments of need where pathologies of trauma exist.

By defining the concept of YCEC, the distinct developmental importance in the context of young caregiving is represented. The significance of this highlight’s dominant representation of young carers in the UK, shaped by an amalgamate of economic, social, cultural, and institutional factors.

The legislative rights afforded to young carers within the UK apply to children and young people from birth to eighteen years (in the context of childhood). There is no lower age limit placed upon an assessment of need in any UK legislation. Strategies which inform practice to help young carers self-identify and enhance professional awareness to identify young carers at the earliest opportunities can be further improved. Providing research that plays a role in equipping all sectors with deep understanding of the ontology of YCEC is therefore instrumental in shaping economic growth, and better outcomes for society.

6. Knowledge User Comment

‘This review clearly demonstrates the urgent need for a greater focus on the youngest young carers. We know from the 2021 Census that over 3000 children aged just 5 to 8 years old were recorded as caring for more than 50 hours each week, in England and Wales yet we know very little about their distinct experiences or support needs, including those in their early years.

If we are to ensure young carers are identified at the earliest opportunity, then there is a real need to focus on how we better identify and support young children who have caring responsibilities. This requires a focus across research, policy, and practice.’ (Andy McGowan, Policy & Practice Manager, Carers Trust)

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Carly Ellicott, Beth Neale and Andy McGowan; methodology, Carly Ellicott; formal analysis, Carly Ellicott and Sayyeda Ume Rubab; investigation, Carly Ellicott.; data curation, Carly Ellicott, Ali Bidaran and Andy McGowan; writing—original draft preparation, Carly Ellicott; writing—review and editing, Carly Ellicott, Beth Neale, Andy McGowan; supervision, Felicity Dewsbery, Associate Professor Alyson Norman and Director of Studies, Professor Helen Lloyd,.

Acknowledgments

The lead author thanks Pen Green Centre for children and their families, for invaluable guidance and feedback in the development of the Young Carers in Early Childhood Research Program. Such gratitude is extended to Carers Trust, including members of the Young Carers Alliance and Young Carers National Voice who have become critical friends of the research process. Special thanks to John Bangs OBE, (Independent Carers Policy Advisor) for his continued support and advice, and to Sara Gowen and Sheffield Young Carers for contributing their time and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Action for Children. (2024). NI Regional Young Carers. Action for Children. https://www.actionforchildren.org.uk/how-we-can-help/our-local-services/find-our-services-near-you/ni-regional-young-carers/.

- Baginsky, M., Manthorpe, J., & Moriarty, J. (2020). The Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and Their Families and Signs of Safety: Competing or Complementary Frameworks? The British Journal of Social Work, 51(7). [CrossRef]

- Barnardo's. (2024). Barnardo’s Northern Ireland. Barnardo’s. https://www.barnardos.org.uk/who-we-are/where-we-work/northern-ireland.

- Becker, S. (2007). Global Perspectives on Children’s Unpaid Caregiving in the Family. Global Social Policy: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Public Policy and Social Development, 7(1), 23–50. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D. L., Wickham, S., Barr, B., & Taylor-Robinson, D. (2024). Poverty and children entering care in England: A qualitative study of local authority policymakers’ perspectives of challenges in Children’s Services. Children and Youth Services Review, 162, 107689. [CrossRef]

- Black, M. M., Walker, S. P., Fernald, L. C. H., Andersen, C. T., DiGirolamo, A. M., Lu, C., McCoy, D. C., Fink, G., Shawar, Y. R., Shiffman, J., Devercelli, A. E., Wodon, Q. T., Vargas-Barón, E., & Grantham-McGregor, S. (2017). Early Childhood Development Coming of age: Science through the Life Course. The Lancet, 389(10064), 77–90. [CrossRef]

- Black, R. E., Liu, L., Hartwig, F. P., Villavicencio, F., Rodriguez-Martinez, A., Vidaletti, L. P., Perin, J., Black, M. M., Blencowe, H., You, D., Hug, L., Masquelier, B., Cousens, S., Gove, A., Vaivada, T., Yeung, D., Behrman, J., Martorell, R., Osmond, C., & Stein, A. D. (2022). Health and development from preconception to 20 years of age and human capital. The Lancet, 399(10336), 1730–1740. [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D., & Hirst, N. (Eds.). (2015). Understanding Early Years Education across the UK. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Boyle, G. (2020). The Moral Resilience of Young People Who Care. Ethics and Social Welfare, 14(3), 266–281. [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, A. (2018). Datafied at four: the role of data in the “schoolification” of early childhood education in England. Learning, Media and Technology, 44(1), 7–21. [CrossRef]

- Brimblecombe, N., Knapp, M., King, D., Stevens, M., & Cartagena Farias, J. (2020). The high cost of unpaid care by young people: health and economic impacts of providing unpaid care. BMC Public Health, 20(1). [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development. Harvard University Press. [CrossRef]

- Burch, P. K., Simpson, D. A., Taylor, V., Bala, D. A., & Morgado De Queiroz, S. (2024, June). Babies in care proceedings: What do we know about parents with learning disabilities or difficulties? Https://Www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/; Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. https://www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Babies-in-care-proceedings-What-do-we-know-about-parents-with-learning-disabilities-or-difficulties.pdf.

- Burlingham, M., Maguire, L., Hibberd, L., Turville, N., Cowdell, F., & Bailey, E. (2023). The needs of multiple birth families during the first 1001 critical days: A rapid review with a systematic literature search and narrative synthesis. Public Health Nursing, 41. [CrossRef]

- Carers Trust. (2023, November 1). APPG on Young Carers and Young Adult Carers - Inquiry into life opportunities. Carers.org. https://carers.org/all-party-parliamentary-group-appg-for-young-carers-and-young-adult-carers/appg-on-young-carers-and-young-adult-carers-inquiry-into-life-opportunities?utm_campaign=14214359_APPG%20inquiry%20%20%28to%20YC%20Alliance%20members%29&utm_medium=email&utm_source=Carers%20Trust&dm_i=I34.

- Carers Trust. (2024). Young Carers Alliance. Carers.org. https://carers.org/young-carers-alliance/young-carers-alliance.

- Carers Trust. (2015). Supporting Young Carers Aged 5–8 A Resource for Professionals Working with Younger Carers. Https://Carers.org/Downloads/Resources-Pdfs/Younger-Carers-Aged-5-To-8/Supporting-Young-Carers-Aged-5-To-8-a-Resource-For-Professionals-Working-With-Younger-Carers.pdf; Carers Trust. Carers Trust, 2015 supporting-young-carers-aged-5-to-8-a-resource-for-professionals-working-with-younger-carers.pdf.

- Carers Trust. (2023, November). All-party parliamentary group inquiry lays bare the Impact on life opportunities of young carers. Https://Carers.org/Downloads/Appg-For-Young-Carers-And-Young-Adults-Carers-Reportlr.pdf; Carers Trust. https://carers.org/downloads/appg-for-young-carers-and-young-adults-carers-reportlr.pdf.

- Carers Trust. (2024, February). “No Wrong Doors” for Young Carers. Https://Carers.org/Campaigning-For-Change/No-Wrong-Doors-For-Young-Carers-a-Review-And-Refresh; Carers Trust. https://carers.org/campaigning-for-change/no-wrong-doors-for-young-carers-a-review-and-refresh.

- Carers Trust, & The Children's Society. (2022). Young Carers in Schools Programme. Young Carers in Schools Programme. https://youngcarersinschools.com/.

- Caring Together. (2020). Young carers EYFS and key stage 1 Resource pack for schools. https://assets.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/wpuploads/2022/06/Caring-Together-Young-Carers-Awareness-Resource-for-EYFS-and-KS1.pdf.

- Chikhradze, N., Knecht, C., & Metzing, S. (2017). Young carers: growing up with chronic illness in the family - a systematic review 2007-2017. Journal of Compassionate Health Care, 4(1). [CrossRef]

- Children and Young People’s Health Policy Influencing Group. (2024). The healthiest generation of children ever A roadmap for the health system from the Children and Young People’s Health Policy Influencing Group. https://www.ncb.org.uk/sites/default/files/uploads/files/HPIG%20-%20The%20healthiest%20generation%20of%20children%20ever_0.pdf.

- Children's Commissioner for England. (2024, October 31). What is this plan for? The purpose and content of children in need plans | Children’s Commissioner for England. Children’s Commissioner for England. https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/resource/what-is-this-plan-for-the-purpose-and-content-of-children-in-need-plans/.

- Children's Commissioner for England. (2016). The support provided to Young Carers in England. Children’s Commissioner for England. https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/resource/the-support-provided-to-young-carers-in-england/.

- Cliffe, J., & Solvason, C. (2022). What is it that we still don’t get? – Relational pedagogy and why relationships and connections matter in early childhood. Power and Education, 15(3), 175774382211242. [CrossRef]

- Commonwealth Secretariat. (2023, March 18). Commonwealth Charter for Young Carers. COSW. https://cosw.info/young-cares/.

- Correia, N., Aguiar, C., & Amaro, F. (2021). Children’s participation in early childhood education: A theoretical overview. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 24(3), 146394912098178. [CrossRef]

- Correia, N., Aguiar, C., & PARTICIPA Consortium. (2023). Children’s Voices in Early Childhood Education and Care. In Establishing Child Centred Practice in a Changing World, Part B. 9–22. (Emerald Studies in Child Centred Practice), Emerald Publishing Limited, Leeds. [CrossRef]

- Danese, A., & Lewis, S. (2016). Psychoneuroimmunology of Early-Life Stress: The Hidden Wounds of Childhood Trauma? Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(1), 99–114. [CrossRef]

- Dariotis, J. K., Chen, F. R., Park, Y. R., Nowak, M. K., French, K. M., & Codamon, A. M. (2023). Parentification Vulnerability, Reactivity, Resilience, and Thriving: A Mixed Methods Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(13), 6197–6197. [CrossRef]

- Darling, P., Jackson, N., & Manning, C. (2019). Young carers: unknown and underserved. British Journal of General Practice, 69(688), 532–533. [CrossRef]

- Davidi, C. (2023, December 30). People before parents - Early Childhood Matters. Early Childhood Matters. https://earlychildhoodmat.

- ters.online/2023/people-before-parents/.

- Deloitte. (2024). The Royal Foundation Early Years report. Deloitte United Kingdom. https://www.deloitte.com/uk/en/about/story/im pact/5-million-futures-royal-foundation.html.

- Department for Education. (2015, March 26). Working Together to Safeguard Children. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/working-together-to-safeguard-children--2.

- Department for Education. (2016). The lives of young carers in England. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-lives-of-young-carers-in-england.

- Department for Education. (2023). Children in need, Reporting year 2023. Service.gov.uk. https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/children-in-need.

- Department for Education. (2024a). Children in need, Reporting year 2024. Service.gov.uk. https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/children-in-need/2024.

- Department for Education. (2024b). Early Years Foundation Stage Statutory Framework (EYFS). GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/early-years-foundation-stage-framework--2.

- Department for Education. (2024c, November 18). Keeping children safe, helping families thrive. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/keeping-children-safe-helping-families-thrive.

- Department of Health. (2000). Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and their Families. Nationalarchives.gov.uk. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20130404002518/https://www.education.gov.uk/publications/eOrderingDownload/Framework%20for%20the%20assessment%20of%20children%20in%20need%20and%20their%20families.pdf.

- Department of Health. (NI) (2024). Co-operating to Safeguard Children and Young People in Northern Ireland | Department of Health. Health. https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/publications/co-operating-safeguard-children-and-young-people-northern-ireland.

- Department of Health and Social Care. (2022). Health and Care Act 2022 Impact Assessments Summary Document and Analysis of Additional Measures. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1115453/health-and-care-act-2022-summary-and-additional-measures-impact-assessment.pdf.

- Dickie, J. (2023, March 23). Official child poverty statistics: Nearly a quarter of Scotland’s children still in poverty | CPAG. Cpag.org.uk. https://cpag.org.uk/news/official-child-poverty-statistics-nearly-quarter-scotlands-children-still-poverty.

- Dove, B., Fisher, T., & Purchase, E. (2021). Ever-Widening Circles – The Emergence of Reciprocity in the Camden Village and the (Re)generative Nature of Community. In Family group conference research: reflections and ways forward (A. De Roo & R. Jagtenberg, Eds.; pp. 157–177). Eleven International Publishing.

- Ellicott, C. (2023). Capturing the ontology of young carers in the early years -Threads of hope through lived experience [master’s Dissertation]. Pen Green Centre for children and their families: University of Hertfordshire.

- Ellicott, C., Norman, A., & Jackson, S. (2024). Voicing Experiences of Family Members Providing Care to Loved Ones with a Pituitary Condition. The Family Journal. [CrossRef]

- Ellicott, C., & Woodworth, A. (2024). Young Carers in the UK. In The Routledge Handbook of Child and Family Social Work Research: Knowledge-Building, Application, and Impact (P. Welbourne, B. Lee, & L. Ma, J C, Eds.; 1st ed.). Routledge.

- Emmott, E. H., & Gibbon, S. (2024). Understanding Child Development: A Biosocial Anthropological Approach to Early Life.

- Esabella Hsiu-Wen Yuan, & Ku, Y. (2024). “My childhood life falling apart”: A retrospective study of young carers managing parental. [CrossRef]

- mental illness in Taiwan. Child Abuse Review, 33(4). [CrossRef]

- Eurochild. (2022). Eurochild-Northern Ireland – Country Profile 2022 on children in need. Eurochild.org. https://eurochild.org/resource/northern-ireland-country-profile-2022-on-children-in-need/.

- European Early Childhood Education Journal (EECERJ). (2019). Learn about European Early Childhood Education Research Journal. Taylor & Francis.

- Farooq, B., Russell, A. E., Howe, L. D., Herbert, A., Andrew D.A.C. Smith, Fisher, H. L., Baldwin, J. R., Arseneault, L., Danese, A., & Mars, B. (2024). The relationship between type, timing and duration of exposure to adverse childhood experiences and adolescent self-harm and depression: findings from three UK prospective population-based cohorts. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 65(10). [CrossRef]

- Fayazi, M., Arsalandeh, F., Hasani, J., & Masoud, B. (2020). Psychoneuroimmunology of Attachment: A review study. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi Journal (RRJ), 9(4), 159–170. http://frooyesh.ir/article-1-1851-en.html.

- Felitti, V. J. (1998). Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. [CrossRef]

- Fives, A., Kennan, D., Canavan, J., & Brady, B. (2019). Why we still need the term “Young Carer.” Critical Social Work, 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Fleitas Alfonzo, L., Singh, A., Disney, G., Ervin, J., & King, T. (2022). Correction to: Mental health of young informal carers: a systematic review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 57(4). [CrossRef]

-

Gabor Mate - Trauma Is Not What Happens to You, It Is What Happens Inside You. (2021). Www.youtube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nmJOuTAk09g.

- Garner, A., & Yogman, M. (2021). Preventing Childhood Toxic Stress: Partnering with Families and Communities to Promote Relational Health. Pediatrics, 148(2), e2021052582. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J., Colton, F., & Sanderson, C. (2019). Young carers. British Journal of General Practice, 69(687), 504–504. [CrossRef]

- Gilgoff, R., Singh, L., Koita, K., Gentile, B., & Marques, S. S. (2020). Adverse Childhood Experiences, Outcomes, and Interventions. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 67(2), 259–273. [CrossRef]

- Gough, G., & Gulliford, A. (2020). Resilience amongst young carers: investigating protective factors and benefit-finding as perceived by young carers. Educational Psychology in Practice, 36(2), 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Gov.Scot. (2021). Carers (Scotland) Act 2016: statutory guidance - updated July 2021. Www.gov.scot. https://www.gov.scot/publications/carers-scotland-act-2016-statutory-guidance-updated-july-2021/.

- Gov.UK(1989,November16).ChildrenAct1989.Legislation.gov.uk;HMGovernment.https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1989/41/contents.

- Gov.UK. (2014). Children and Families Act 2014. Legislation.gov.uk. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/6/contents.

- Gov.UK. (2024, January 30). Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel: annual report 2022 to 2023. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/child-safeguarding-practice-review-panel-annual-report-2022-to-2023.

- Gov.Wales. (2024, May 21). Children Receiving Care and Support Census: 31 March 2023 (official statistics in development) | GOV.WALES. Www.gov.wales. https://www.gov.wales/children-receiving-care-and-support-census-31-march-2023-official-statistics-development-html.

- Gowen, S. M., Sarojini Hart, C., Sehmar, P., & Wigfield, A. (2021). “. It takes a lot of brain space”: Understanding young carers’ lives in England and the implications for policy and practice to reduce inappropriate and excessive care work. Children & Society, 36(1). [CrossRef]

- Heintz, J., Staab, S., & Turquet, L. (2021). Don’t Let Another Crisis Go to Waste: The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Imperative for a Paradigm shift. Feminist Economics, 27(1-2), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, B. A., Vo, J. B., Dionne-Odom, J. N., & Bakitas, M. A. (2021). Parentification Among Young Carers: A Concept Analysis. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 38(5). [CrossRef]

- Janes, E., Forrester, D., Reed, H., & Melendez-Torres, G. J. (2021). Young carers, mental health and psychosocial wellbeing: A realist synthesis. Child: Care, Health and Development, 48(2). [CrossRef]

- JBI. (2024). systematic-review-register - Systematic Review Register | Joanna Briggs Institute. Jbi.global. https://jbi.global/systematic-review-register.

- Johnstone, L., & Boyle, M. (2018). The Power Threat Meaning Framework: An alternative nondiagnostic conceptual system. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 1(18). [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S., Sempik, J., Leu, A., & Becker, S. (2019). Young Carers Research, Practice and Policy: An Overview and Critical Perspective on Possible Future Directions. Adolescent Research Review, 5(5). [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S., Sempik, J., Leu, A., & Becker, S. (2023). Young carers research, practice and policy: an overview and critical perspective on possible future directions. Intergenerational Justice Review, 9(2), 40-51. [CrossRef]

- Kettell, L. (2018). Young adult carers in higher education: the motivations, barriers and challenges involved – a UK study. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- King, T., Redmond, G., Reavley, N., Hamilton, M., & Barr, A. (2023). A Prospective Study of Suicide and Self-Harm Among Young Carers Using an Australian Cohort. The Lancet. [CrossRef]

- King, T., Singh, A., & Disney, G. (2021). Associations between young informal caring and mental health: a prospective observational study using augmented inverse probability weighting. The Lancet Regional Health - Western Pacific, 15, 100257. [CrossRef]

- Lacey, R. E., Xue, B., & McMunn, A. (2022). The mental and physical health of young carers: a systematic review. The Lancet Public Health, 7(9), e787–e796. [CrossRef]

- Lannamann, J. W., & McNamee, S. (2019). Unsettling trauma: from individual pathology to social pathology. Journal of Family Therapy, 42(3). [CrossRef]

- Lätsch, D., Quehenberger, J., Portmann, R., & Jud, A. (2023). Children’s participation in the child protection system: Are young people from poor families less likely to be heard? Children and Youth Services Review, 145, 106762. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, P. (2022). Hearing and acting with the voices of children in early childhood. Journal of the British Academy, 8s4, 077–090. [CrossRef]

- Leadbitter, H., Morris, D., Cartlidge, K., Samways, E., Blackmore, C., & Fry, L. (2024). Unseen Sacrifices: Understanding the educational disadvantages faced by young carers. https://www.mytimeyoungcarers.org/res/MYTIME%20Report%20-%20Unseen%20Sacrifices%20Faced%20by%20Young%20Carers.pdf.

- Legislation.gov.uk. (1995). The Children (Northern Ireland) Order 1995. Www.legislation.gov.uk. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/nisi/1995/755/contents/made.

- Legislation.gov.uk. (2014). Social Services and Well-being (Wales) Act 2014. Legislation.gov.uk. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/anaw/2014/4/contents.

- Letelier, A., McMunn, A., McGowan, A., Neale, B., & Lacey, R. (2024). Understanding young caring in the UK pre- and post-COVID-19: Prevalence, correlates, and insights from three UK longitudinal surveys. Children and Youth Services Review, 166, 108009–108009. [CrossRef]

- Leu, A., Berger, F. M. P., Heino, M., Nap, H. H., Untas, A., Boccaletti, L., Lewis, F., Phelps, D., & Becker, S. (2022). The 2021 cross-national and comparative classification of in-country awareness and policy responses to “young carers.” Journal of Youth Studies, 26(5), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Lindley, P. (2023). Raising the Nation. In Policy Press eBooks. Policy Press. [CrossRef]

- Lippard, C. N., La Paro, K. M., Rouse, H. L., & Crosby, D. A. (2017). A Closer Look at Teacher–Child Relationships and Classroom Emotional Context in Preschool. Child & Youth Care Forum, 47(1), 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Masiran, R., Ibrahim, N., Awang, H., & Lim, P. Y. (2023). The Positive and Negative Aspects of parentification: an Integrated Review. Children and Youth Services Review, 144(106709), 106709. [CrossRef]

- McWayne, C., Hyun, S., Diez, V., & Mistry, J. (2021). “We Feel Connected… and Like We Belong”: A Parent-Led, Staff-Supported Model of Family Engagement in Early Childhood. Early Childhood Education Journal, 50. [CrossRef]

- Medforth, N. (2022). “Our Unified Voice to Implement Change and Advance the View of Young Carers and Young Adult Carers.” An Appreciative Evaluation of the Impact of a National Young Carer Health Champions Programme. Social Work in Public Health, 37(6), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- News, I. (2016, February 29). The New Day: New daily national newspaper launches with free edition. ITV News. https://www.itv.com/news/2016-02-29/the-new-day-new-daily-national-newspaper-launches-with-free-edition.

- NISRA. (2021). 2021 Census. Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. https://www.nisra.gov.uk/statistics/census/2021-census.

- NSPCC. (2021). Early years sector: learning from case reviews. NSPCC Learning. https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/research-resources/learning-from-case-reviews/early-years-sector.

- O’Dea, N. A., & Marcelo, A. K. (2022). “You can’t do all”: Caregiver Experiences of Stress and Support Across Ecological Contexts. Journal of Child and Family Studies. [CrossRef]

- Oehring, D., & Gunasekera, P. (2024). Ethical Frameworks and Global Health: A Narrative Review of the “Leave No One Behind” Principle. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing, 61. [CrossRef]

- Ofsted. (2019). Education Inspection Framework (EIF). GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/education-inspection-framework.

- Ofsted. (2024, October 16). Commentary: Changes in access to childcare in England. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/changes-to-access-to-childcare-in-england/commentary-changes-in-access-to-childcare-in-england.

- Olsen, R. (2000). Families under the microscope: parallels between the young carers debate of the 1990s and the transformation of childhood in the late nineteenth century. Children Society, 14(5), 384–394. [CrossRef]

- Ornstein, M. T., & Caruso, C. C. (2024). The Social Ecology of Caregiving: Applying the Social–Ecological Model across the Life Course. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(1), 119–119. [CrossRef]

- Ortega, Y., April Leigh Passi, Wayne, J., Mama, Cale, B., & Sarkar, M. (2023). Beginning the Quilt: A Polyvocal and Diverse Collective Seeking New Forms of Knowledge Production. 22. [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—a Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1). [CrossRef]

- Phelps, D. (2017). The Voices of Young Carers in Policy and Practice. Social Inclusion, 5(3), 113. [CrossRef]

- Phelps, D. (2020). Supporting young carers from hidden and seldom heard groups: A literature review. https://www.childrenssociety.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-11/Seldom-Heard-Report.pdf.

- Pollock, D., Alexander, L., Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Khalil, H., Godfrey, C. M., McInerney, P., Synnot, A., & Tricco, A. C. (2022). Moving from consultation to co-creation with knowledge users in scoping reviews: guidance from the JBI Scoping Review Methodology Group. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 20(4), 969–979. [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D., Peters, M. D. J., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Alexander, L., Tricco, A. C., Evans, C., de Moraes, É. B., Godfrey, C. M., Pieper, D., Saran, A., Stern, C., & Munn, Z. (2023). Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 21(3), 520–532. [CrossRef]

- Powell, L., Spencer, S., Clegg, J., & Wood, M. (2024). A Country that works for all children and young people: An evidence-based approach to supporting children in the preschool years. Report. N8 Research Partnership. University of Leeds. [CrossRef]

- Richter, L. M., Cappa, C., Issa, G., Lu, C., Petrowski, N., & Naicker, S. N. (2020). Data for action on early childhood development. The Lancet, 396(10265), 1784–1786. [CrossRef]

- Ronicle, J., & Kendall, S. (2011). Improving support for young carers - family focused approaches York Consulting LLP. https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/id/eprint/1964/1/DFE-RR084.pdf.

- Saragosa, M., Frew, M., Hahn-Goldberg, S., Orchanian-Cheff, A., Abrams, H., & Okrainec, K. (2022). The Young Carers’ Journey: A Systematic Review and Meta Ethnography. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 5826. [CrossRef]

- Scotland's Census. (2022). Scotland’s Census 2022 - Health, disability and unpaid care. Scotland’s Census. https://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/2022-results/scotland-s-census-2022-health-disability-and-unpaid-care/.

- Scottish Government. (2022, September 30). Getting It Right for Every Child (GIRFEC) Policy Statement. Www.gov.scot. https://www.gov.scot/publications/getting-right-child-girfec-policy-statement/.

- Scottish Government. (2023, August 31). Supporting documents. Www.gov.scot. https://www.gov.scot/publications/national-guidance-child-protection-scotland-2021-updated-2023/documents/.

- Sharpe, L. (2024). Parentification: Identifying Young Caregivers at Risk. The Journal of Nurse Practitioners, 104930–104930. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, D., Loughran, S., Lumsden, E., Mazzocco, P., Clark, R. M., & Winterbottom, C. (2017). “Seen but not heard.” Practitioners work with poverty and the organising out of disadvantaged children’s voices and participation in the early years. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 25(2), 177–188. [CrossRef]

- Spratt, T., McGibbon, M., & Davidson, G. (2018). Using Adverse Childhood Experience Scores to Better Understand the Needs of Young Carers. The British Journal of Social Work, 48(8), 2346–2360. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M., Brimblecombe, N., Gowen, S., Skyer, R., & Moriarty, J. (2024). Young carers’ experiences of services and support: What is helpful and how can support be improved? PloS One, 19(3), e0300551–e0300551. [CrossRef]

- Treisman, K. (2021). TREASURE BOX FOR CREATING TRAUMA-INFORMED ORGANIZATIONS: a ready-to-use resource for... trauma, adversity, and culturally informed, infuse. Jessica Kingsley.

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., & Lewin, S. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. (2018). EARLY CHILDHOOD DEVELOPMENT in the UNICEF Strategic Plan 2018-2021. https://www.unicef.org/sites/default/files/2019-05/Early%20Childhood%20Development%20in%20the%20UNICEF%20Strategic%20Plan%202018-2021.pdf.

- UNICEF. (2023). The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023 | Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sdgs.un.org. https://sdgs.un.org/documents/sustainable-development-goals-report-2023-53220.

- United Nations. (2023). World Population Prospects. United Nations. https://population.un.org/wpp/.

- Walker, O., Moulding, R., & Mason, J. (2024). The experience of young carers in Australia: a qualitative systematic review and meta-ethnographic synthesis. Australian Journal of Psychology, 76(1). [CrossRef]

- Waters, J. (2019). Assessing the needs of young carers and young adult carers in a southwest London borough. Primary Health Care, 29(3), 18–27. [CrossRef]

- Webb, C. (2021). In Defence of Ordinary Help: Estimating the effect of Early Help/Family Support Spending on Children in Need Rates in England using ALT-SR. Journal of Social Policy, 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Welsh Government. (2022). Working Together to Safeguard People: Code of Safeguarding Practice. https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2022-01/working-together-to-safeguard-people--code-of-safeguarding-practice_0.pdf.

- Woodman, J., Simon, A., Hauari, H., & Gilbert, R. (2019). A scoping review of “think-family” approaches in healthcare settings. Journal of Public Health, 42(1). [CrossRef]

- Yghemonos, S. (2023). Eurocarers’ Policy Paper on Young Carers. Intergenerational Justice Review, 9(2). [CrossRef]

- Young Carers National Voice. (2022). Young Carers National Voice. Young Carers National Voice. https://www.ycnv.org.uk/.

- Yuan, E. H.-W., & Ku, Y.-W. (2024). The Sacrificed Children: Listening to the Voices of Former Young Carers Supporting Parents with Mental Illness. The British Journal of Social Work. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).