Submitted:

29 November 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Literature Review

Methodology

Energy-Efficient Lighting Technologies

Control Systems for Street Lighting

Renewable Energy for Street Lighting

Forecasting and Neural Network Applications

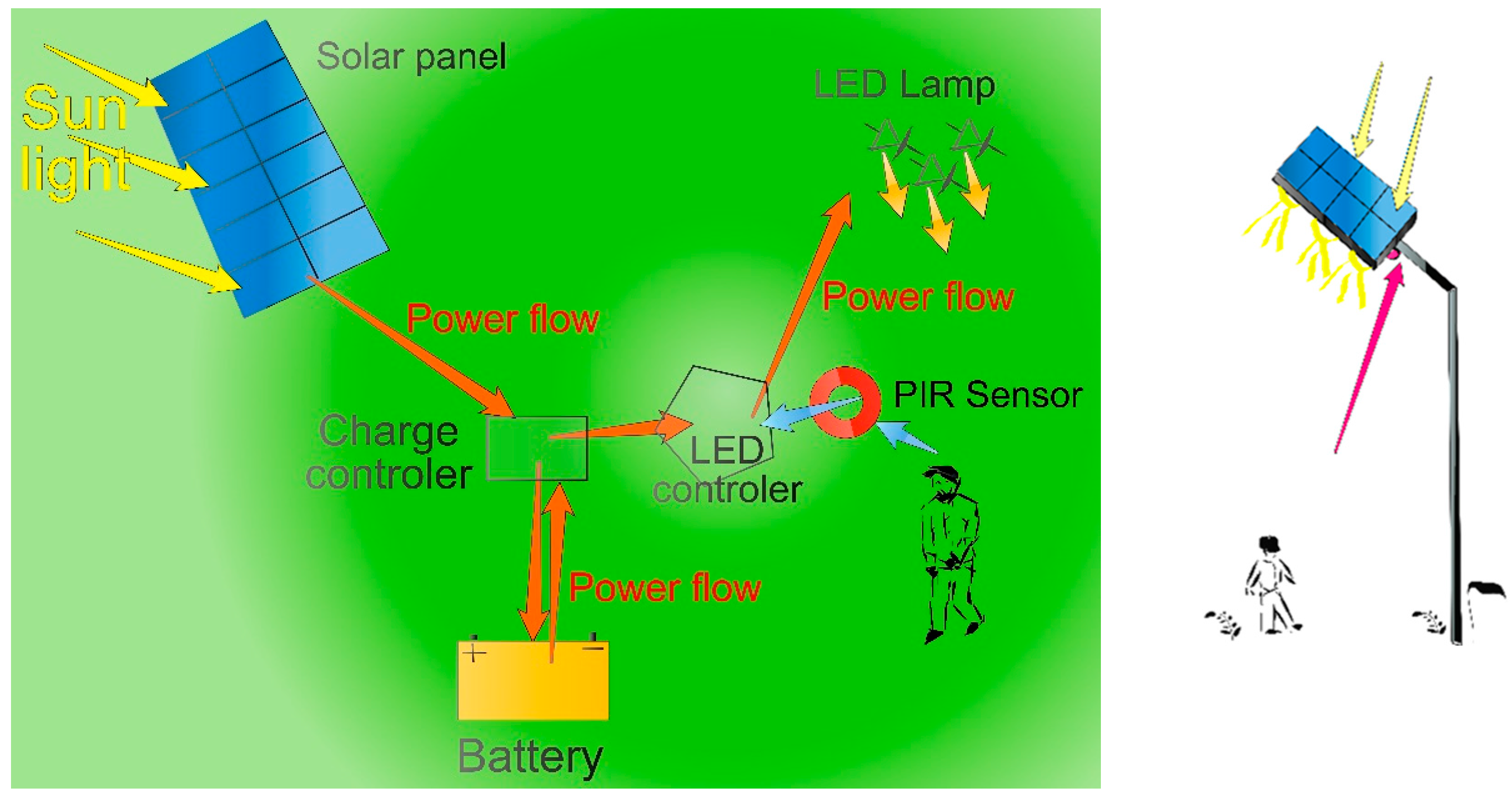

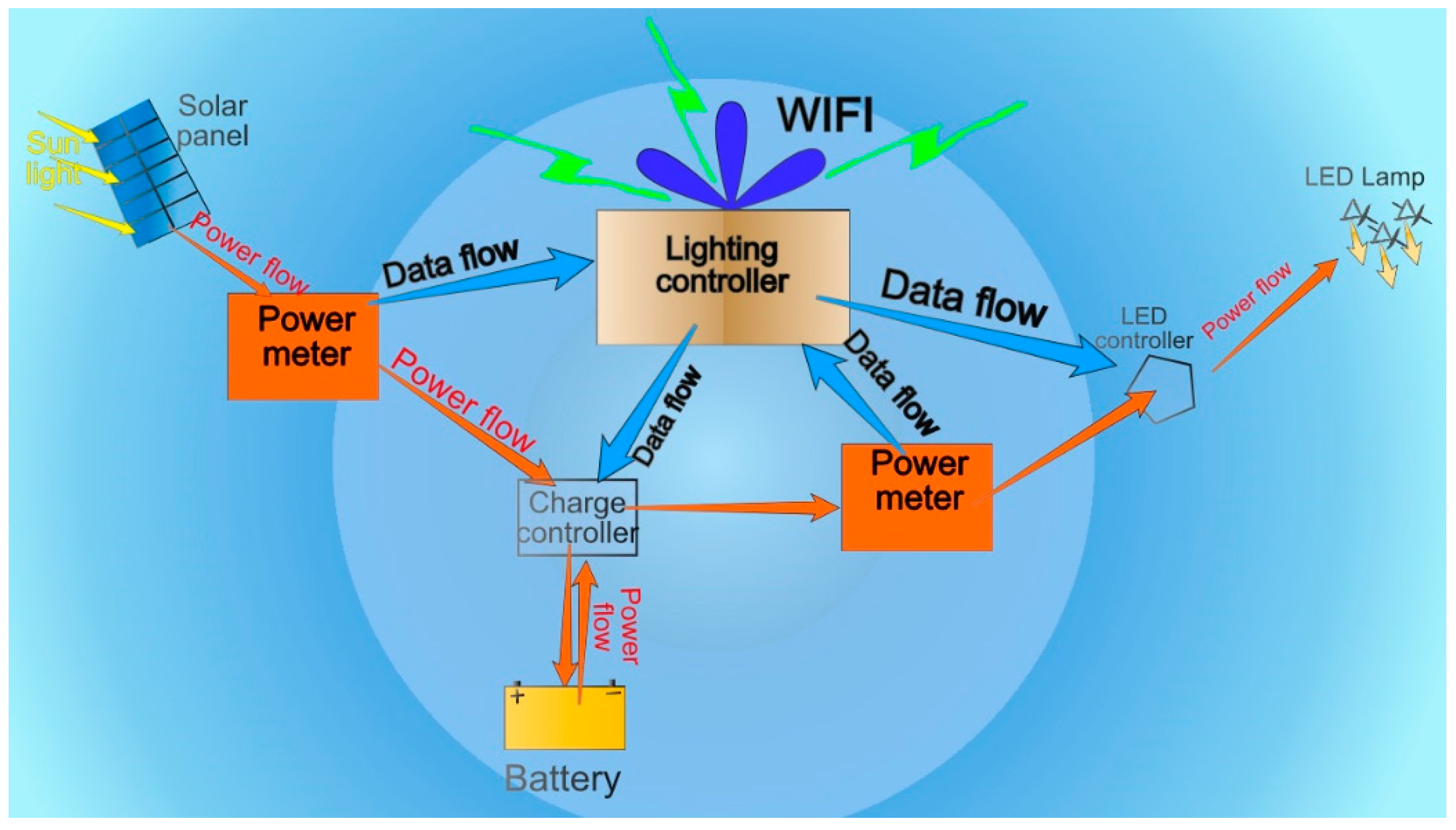

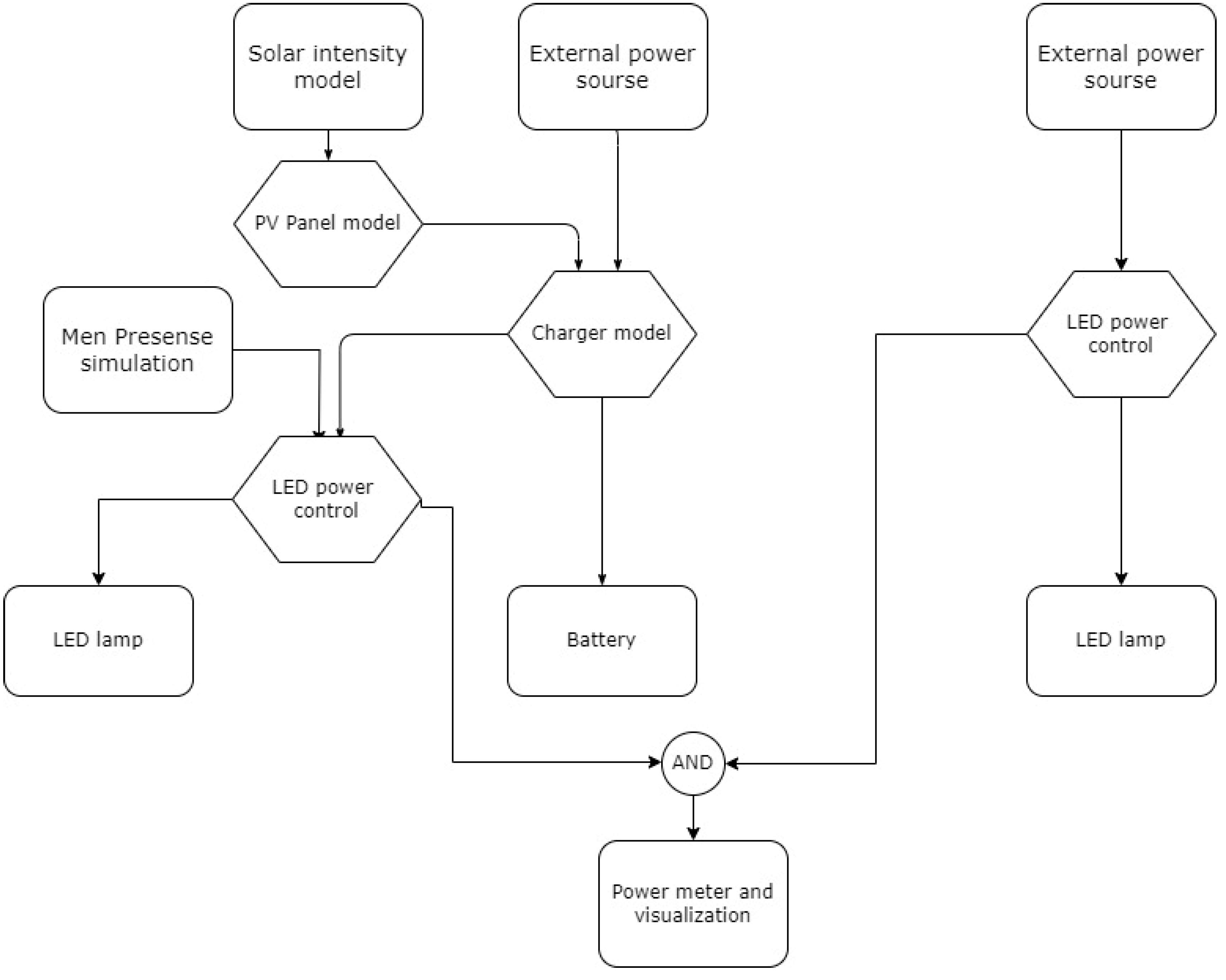

System Design

Materials and Methods

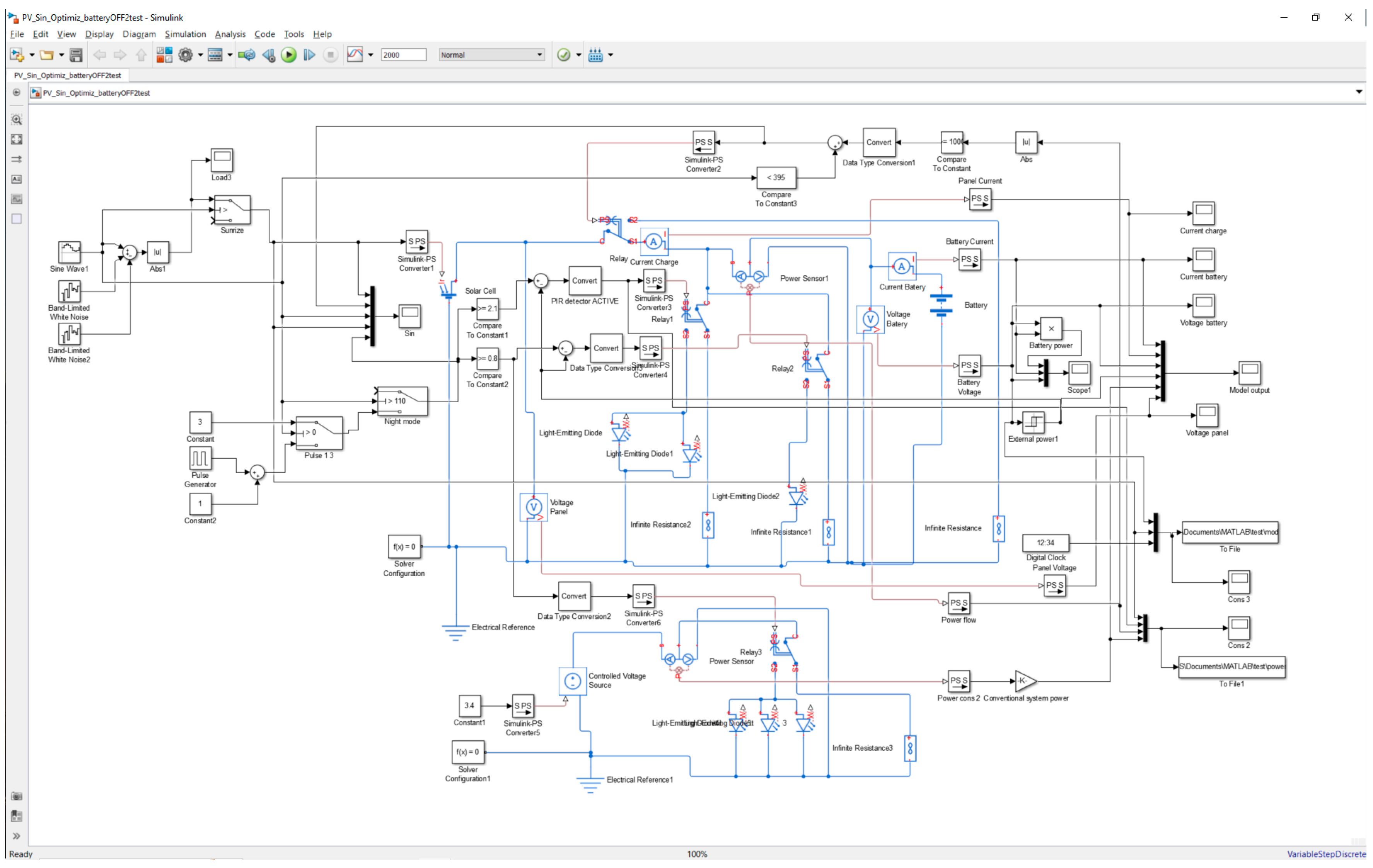

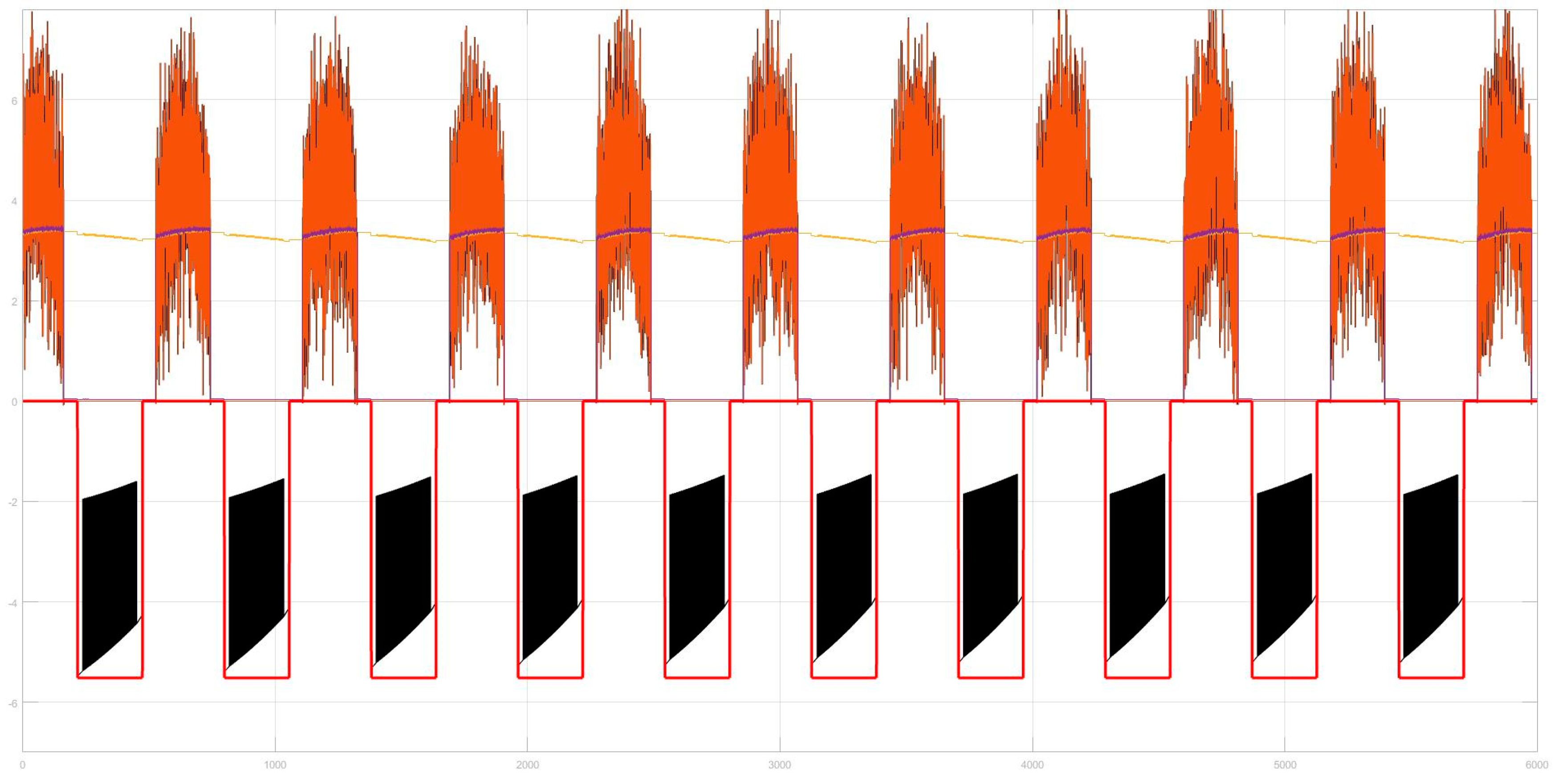

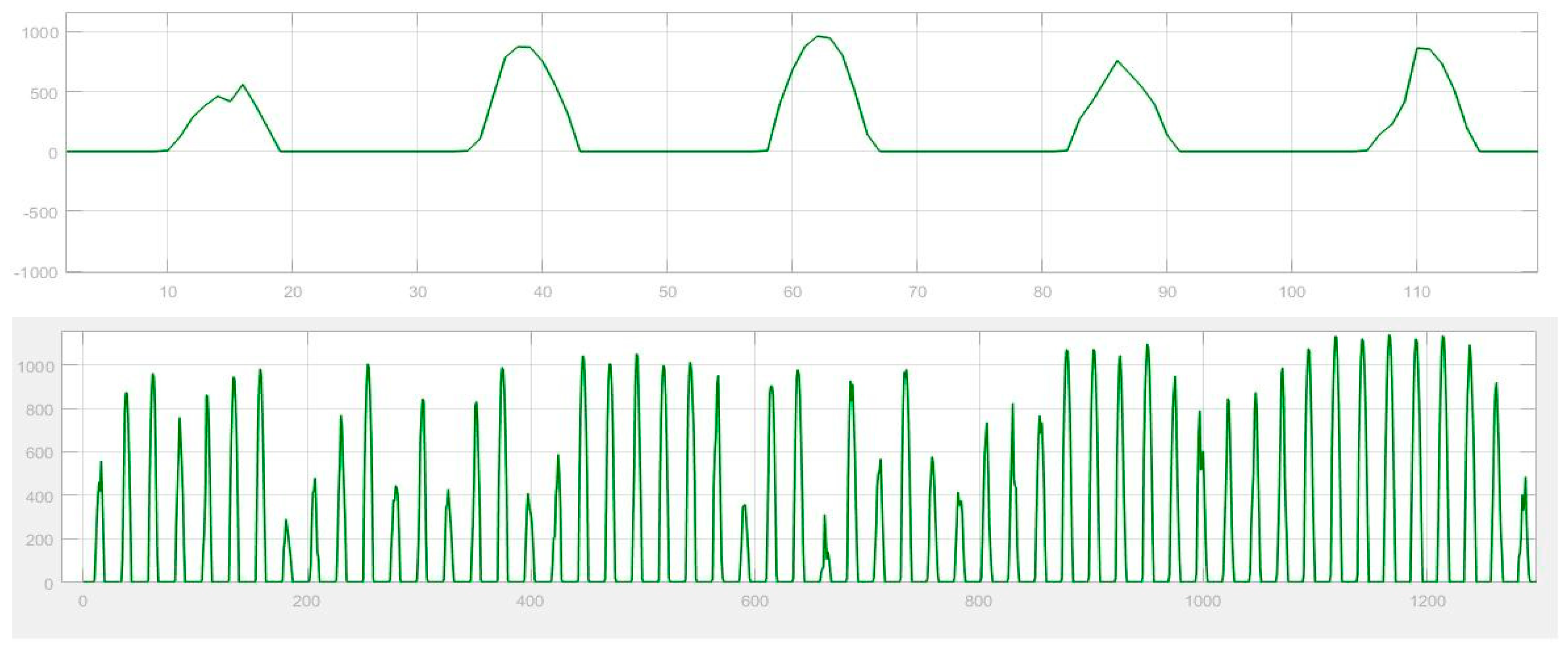

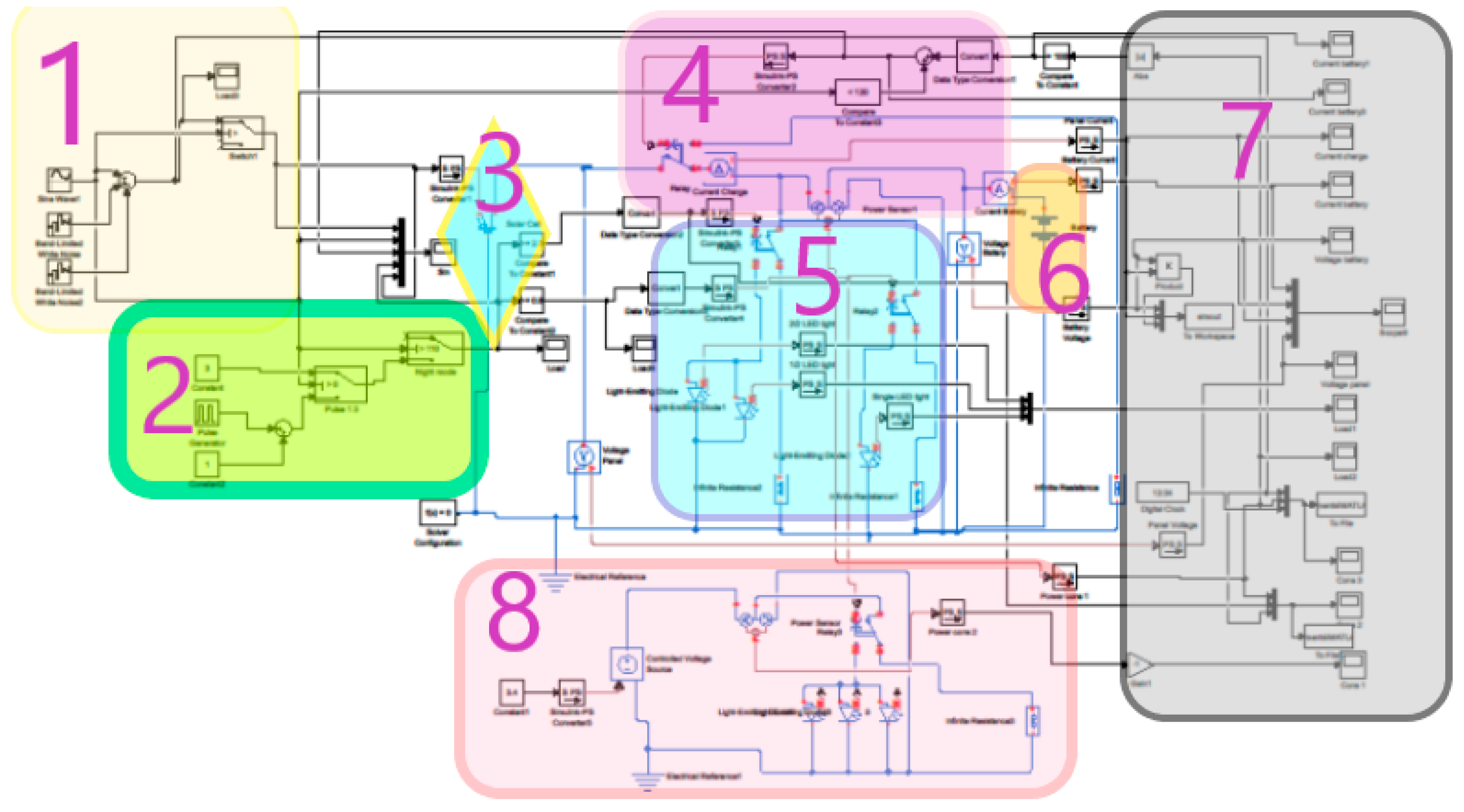

Simulation Method

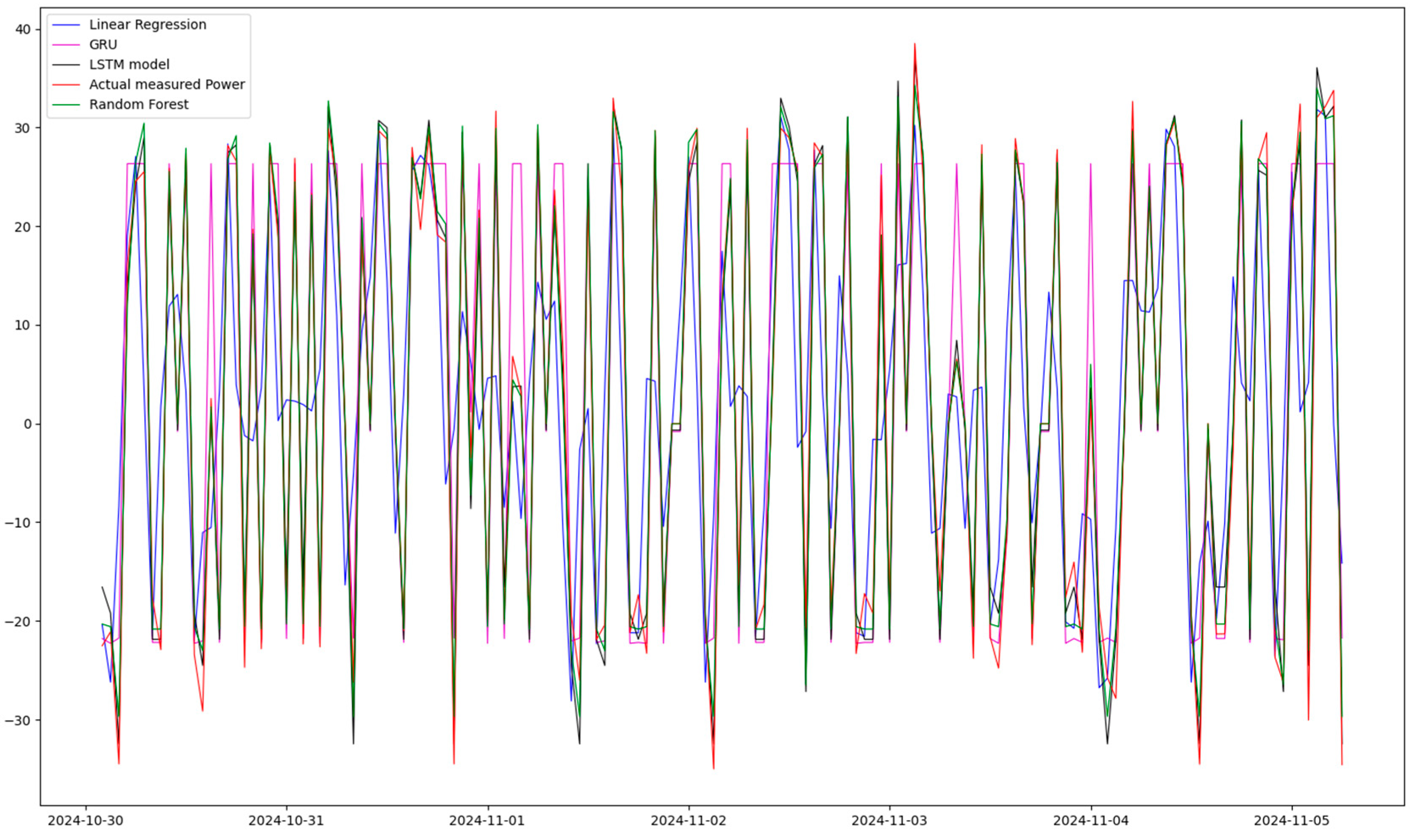

| Models | Test score | MSE | Test score train | MSE train |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lin Regression | 2,631 | 6,923 | 2,590 | 6,707 |

| LSTM | 16,408 | 269,230 | 15,671 | 245,590 |

| Rand Forest | 2,212 | 4,894 | 1,980 | 3,919 |

| GRU | 5,160 | 26,627 | 4,980 | 24,798 |

Results and Discussion

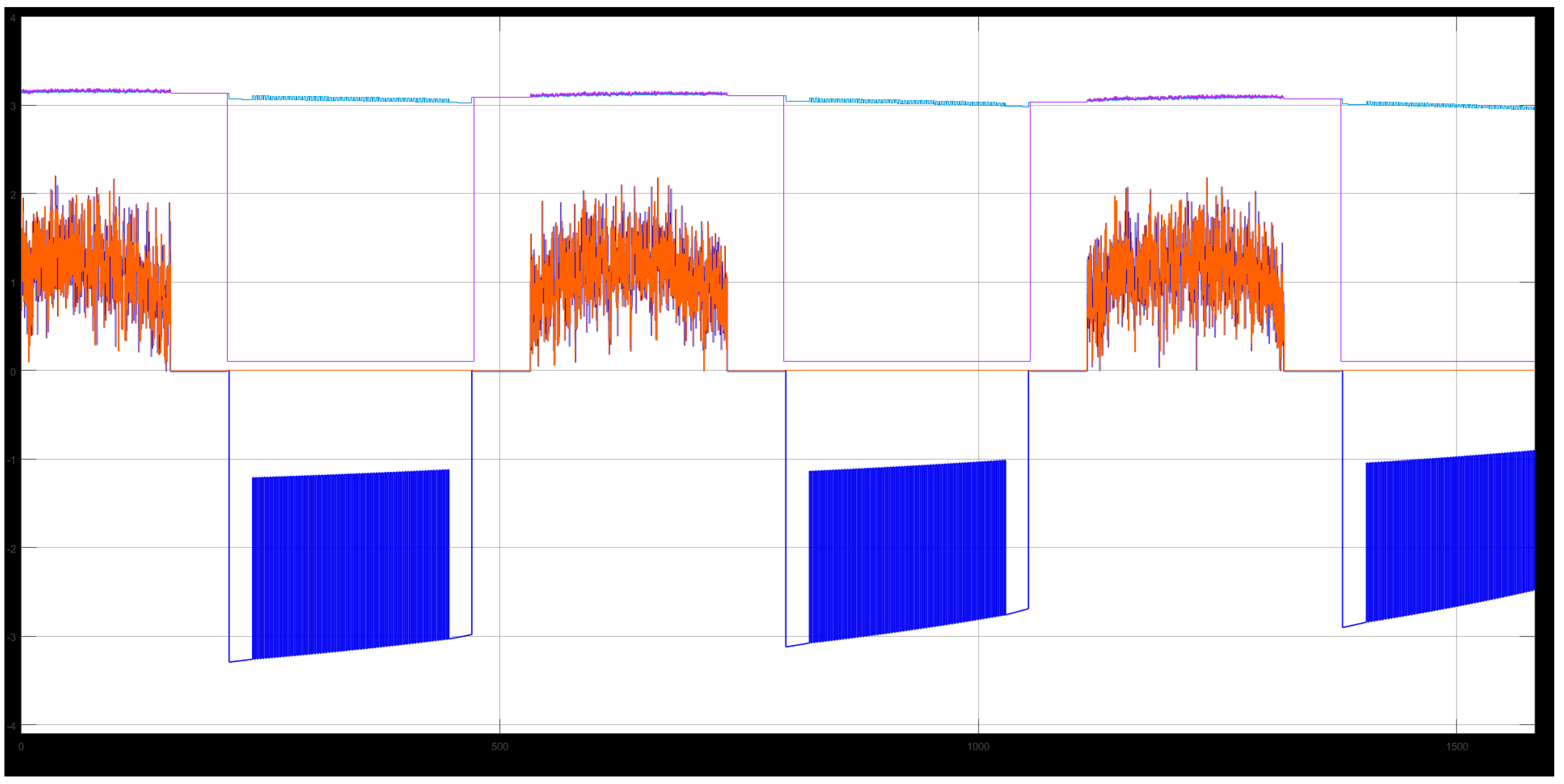

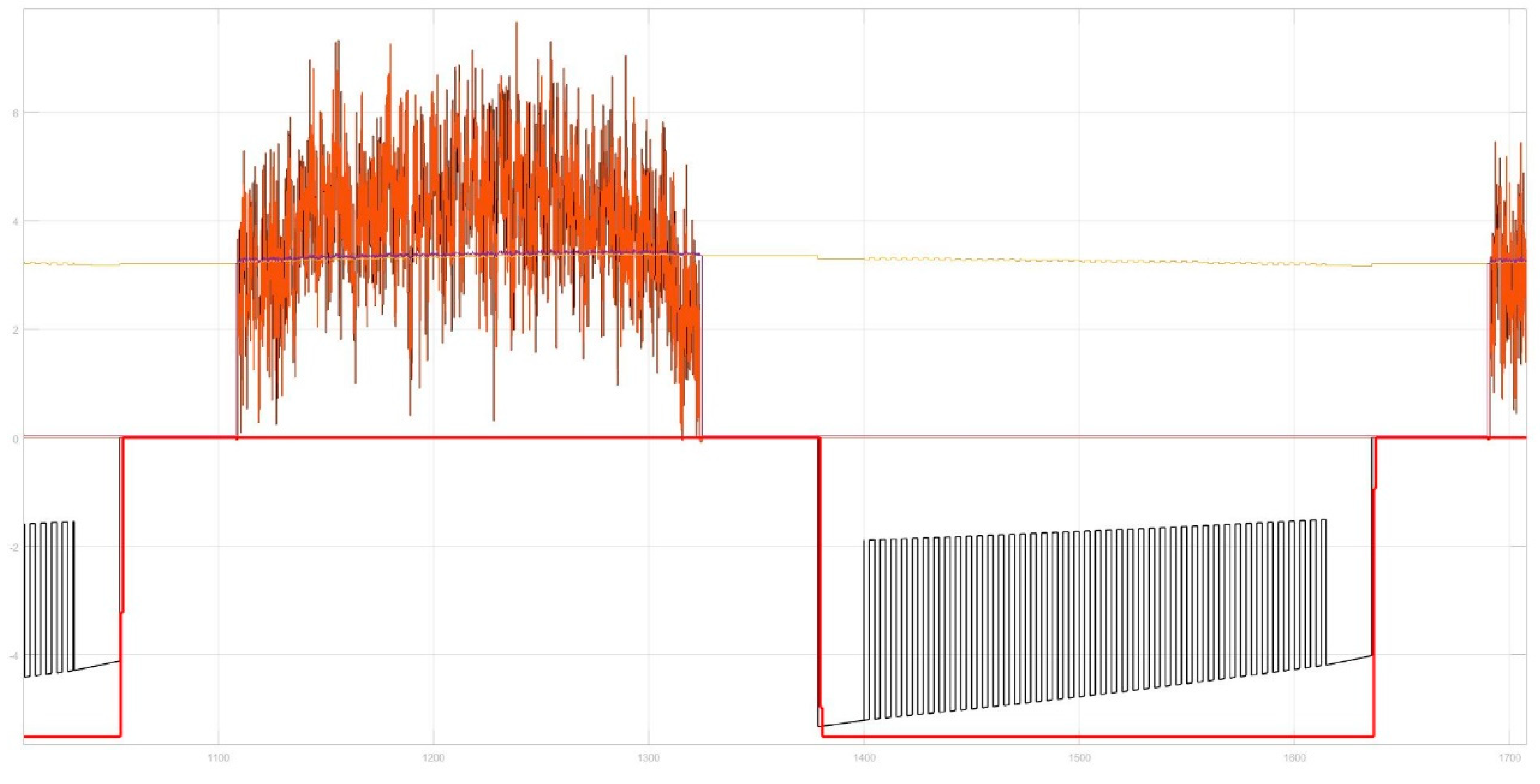

Simulation Results

ANN Prediction Accuracy

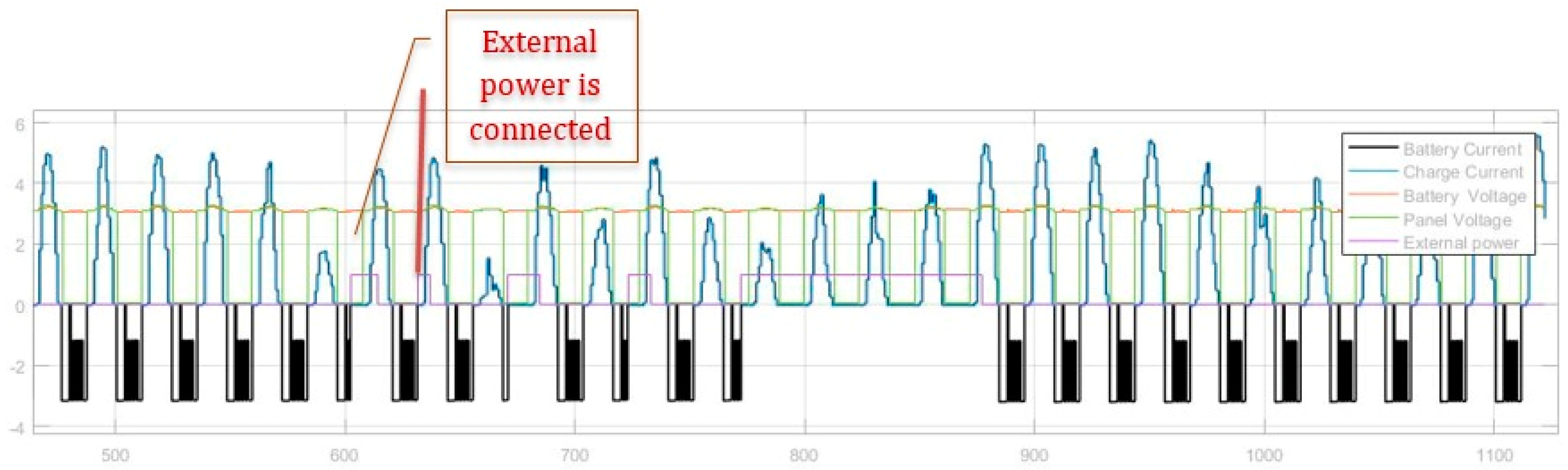

Impact on External Power Sources

Conclusion

Funding

References

- Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the digital and data transformation in the electricity sector Economic Commission for Europe Committee on Sustainable Energy Group of Experts on Energy Efficiency Group of Experts on Cleaner Electricity Systems Eleventh session Geneva, 16-17 September 2024 ECE_ENERGY_GE.6_2024_3_ECE_ENERGY_GE.5_2024_3e.

- Tukymbekov, D.; Saymbetov, A.; Nurgaliyev, M.; Kuttybay, N.; Dosymbetova, G.; Svanbayev, Y. Intelligent autonomous street lighting system based on weather forecast using LSTM. Energy 2021, 231, 120902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandasa, P.; Dhanaraj, J.S.A.; Gao, X.-Z. Artificial Neural Network based Smart and Energy Efficient Street Lighting System: A Case Study for Residential area in Hosur. Sustainable Cities and Society 2019, 48, 101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maronchuk, I.I.; Shirokov, I.V.; Velchenko, A.A.; Mironchuk, V.I. Intelligent LED Lighting System. ENERGETIKA. Proc. CIS High. Educ. institutions Power Eng. Assoc. 2018, 61, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, C.; Surya, S.; Gowtham, J.; Chari, R.; Srinivasan, S.; Siddharth, J.P.; Shrimali, H. Energy efficiency and pay-back calculation on street lighting systems. C. Subramani; S. Surya; J. Gowtham; Rahul Chari; S. Srinivasan; J. P. Siddharth; Hemant Shrimali AIP Conf. Proc. 2112, 020082 (2019).

- The Street Lighting Integrated System Case Study, Control Scenarios, Energy Efficiency. Ożadowicz A. Eng.D., Grela J. MSc.

- Abu Adma, M.A.; Elmasry, S.S.; Ahmed, M.H.S.; Ghitas, A. Practical investigation for road lighting using renewable energy sources "Sizing and modelling of solar/wind hybrid system for road lighting application". Renew. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2017, 3, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solar Energy Utilization Analysis on Public Street Lighting in Sulur Kulon Progo Novi Caroko1, Lilis Kurniasari PROCEEDING INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE OF TECHNOLOGY ON COMMUNITY AND ENVIRONMENTAL DEVELOPMENT « Green Technology for Future 4.0 Community and Environment ».

- Valiullin, K.R.; Orenburg State University. Imitational Modeling of a Street Lighting System. Electrotech. Syst. Complexes 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantoni, R.; Brandão, D. A confirmation-based geocast routing algorithm for street lighting systems. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2011, 37, 1147–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, R.; Dotoli, M.; Pellegrino, R. A decision-making tool for energy efficiency optimization of street lighting. Comput. Oper. Res. 2018, 96, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccali, M.; Bonomolo, M.; Ciulla, G.; Galatioto, A.; Brano, V.L. Improvement of energy efficiency and quality of street lighting in South Italy as an action of Sustainable Energy Action Plans. The case study of Comiso (RG). Energy 2015, 92, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Xin, J.; Liu, H. Recurrent Neural Networks Based Photovoltaic Power Forecasting Approach. Energies 2019, 12, 2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, C.L.; Singh, S.; Chakrabarti, S. Combining forecasts of day-ahead solar power. Energy 2020, 202, 117743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.P.; Merrett, G.V.; Weddell, A.S.; White, N.M. A traffic-aware street lighting scheme for Smart Cities using autonomous networked sensors. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2015, 45, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, M.; Xia, F.; Hao, S.; Peng, D.; Cui, C.; Liu, W. PV Power Prediction Based on LSTM With Adaptive Hyperparameter Adjustment. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 115473–115486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modeling of Battery Charging Algorithms Martyanov A.S., Korobatov D.V., Sirotkin E.A. South Ural State University 2016 2nd International Conference on Industrial Engineering, Applications and Manufacturing (ICIEAM).

- Fouilloy, A.; Voyant, C.; Notton, G.; Motte, F.; Paoli, C.; Nivet, M.-L.; Guillot, E.; Duchaud, J.-L. Solar irradiation prediction with machine learning: Forecasting models selection method depending on weather variability. Energy 2018, 165, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Feng, P.X.L. Huang X, Shi J, Gao B, Tai Y, Chen Z, Zhang J. Forecasting hourly solar irradiance using hybrid wavelet transformation and Elman model in smart grid. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 139909e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ferhatmetin34/solar-power-electricity-production/data.

- https://re.jrc.ec.europa.eu/pvg_tools/en/#TMY.

- Okonta, D.E.; Vukovic, V. Smart cities software applications for sustainability and resilience. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the digital and data transformation in the electricity sector Economic Commission for Europe Committee on Sustainable Energy Group of Experts on Energy Efficiency Group of Experts on Cleaner Electricity Systems Eleventh session Geneva, 16-17 September 2024 ECE_ENERGY_GE.6_2024_3_ECE_ENERGY_GE.5_2024_3e.

- Tukymbekov, D.; Saymbetov, A.; Nurgaliyev, M.; Kuttybay, N.; Dosymbetova, G.; Svanbayev, Y. Intelligent autonomous street lighting system based on weather forecast using LSTM. Energy 2021, 231, 120902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandasa, P.; Dhanaraj, J.S.A.; Gao, X.-Z. Artificial Neural Network based Smart and Energy Efficient Street Lighting System: A Case Study for Residential area in Hosur. Sustainable Cities and Society 2019, 48, 101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maronchuk, I.I.; Shirokov, I.V.; Velchenko, A.A.; Mironchuk, V.I. Intelligent LED Lighting System. ENERGETIKA. Proc. CIS High. Educ. institutions Power Eng. Assoc. 2018, 61, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, C.; Surya, S.; Gowtham, J.; Chari, R.; Srinivasan, S.; Siddharth, J.P.; Shrimali, H. Energy efficiency and pay-back calculation on street lighting systems. C. Subramani; S. Surya; J. Gowtham; Rahul Chari; S. Srinivasan; J. P. Siddharth; Hemant Shrimali AIP Conf. Proc. 2112, 020082 (2019). [CrossRef]

- The Street Lighting Integrated System Case Study, Control Scenarios, Energy Efficiency. Ożadowicz A. Eng.D., Grela J. MSc.

- Abu Adma, M.A.; Elmasry, S.S.; Ahmed, M.H.S.; Ghitas, A. Practical investigation for road lighting using renewable energy sources "Sizing and modelling of solar/wind hybrid system for road lighting application". Renew. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2017, 3, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solar Energy Utilization Analysis on Public Street Lighting in Sulur Kulon Progo Novi Caroko1, Lilis Kurniasari PROCEEDING INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE OF TECHNOLOGY ON COMMUNITY AND ENVIRONMENTAL DEVELOPMENT « Green Technology for Future 4.0 Community and Environment ».

- IMITATIONAL MODELING OF A STREET LIGHTING SYSTEM Kamil R. Valiullin. [CrossRef]

- Pantoni, R.; Brandão, D. A confirmation-based geocast routing algorithm for street lighting systems. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2011, 37, 1147–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, R.; Dotoli, M.; Pellegrino, R. A decision-making tool for energy efficiency optimization of street lighting. Comput. Oper. Res. 2018, 96, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccali, M.; Bonomolo, M.; Ciulla, G.; Galatioto, A.; Brano, V.L. Improvement of energy efficiency and quality of street lighting in South Italy as an action of Sustainable Energy Action Plans. The case study of Comiso (RG). Energy 2015, 92, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Xin, J.; Liu, H. Recurrent Neural Networks Based Photovoltaic Power Forecasting Approach. Energies 2019, 12, 2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, C.L.; Singh, S.; Chakrabarti, S. Combining forecasts of day-ahead solar power. Energy 2020, 202, 117743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.P.; Merrett, G.V.; Weddell, A.S.; White, N.M. A traffic-aware street lighting scheme for Smart Cities using autonomous networked sensors. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2015, 45, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, M.; Xia, F.; Hao, S.; Peng, D.; Cui, C.; Liu, W. PV Power Prediction Based on LSTM With Adaptive Hyperparameter Adjustment. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 115473–115486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modeling of Battery Charging Algorithms Martyanov A.S., Korobatov D.V., Sirotkin E.A. South Ural State University 2016 2nd International Conference on Industrial Engineering, Applications and Manufacturing (ICIEAM).

- Fouilloy, A.; Voyant, C.; Notton, G.; Motte, F.; Paoli, C.; Nivet, M.-L.; Guillot, E.; Duchaud, J.-L. Solar irradiation prediction with machine learning: Forecasting models selection method depending on weather variability. Energy 2018, 165, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang X, Shi J, Gao B, Tai Y, Chen Z, Zhang J. Forecasting hourly solar irradiance using hybrid wavelet transformation and Elman model in smart grid. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 139909e23. [CrossRef]

- https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ferhatmetin34/solar-power-electricity-production/data.

- https://re.jrc.ec.europa.eu/pvg_tools/en/#TMY.

- Okonta, D.E.; Vukovic, V. Smart cities software applications for sustainability and resilience. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nymann, P., Svane, F., Poulsen, P. B., Thorsteinsson, S., Lindén, J., Ploug, R. O., Mira Albert, M. D. C., Knott, A., Mogensen, I., & Retoft, K. (2016). Design, Characterization, and Modelling of High Efficient Solar Powered Lighting Systems. In Proceedings of the 2016 European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference and Exhibition 2016 (pp. 2827-31).

- Lima, M.A.F.; Carvalho, P.C.; Fernández-Ramírez, L.M.; Braga, A.P. Improving solar forecasting using Deep Learning and Portfolio Theory integration. Energy, 2020; 195, 117016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akindipe, D.; Olawale, O.W.; Bujko, R. Techno-Economic and Social Aspects of Smart Street Lighting for Small Cities – A Case Study. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomba, V.; Borri, E.; Charalampidis, A.; Frazzica, A.; Karellas, S.; Cabeza, L.F. An Innovative Solar-Biomass Energy System to Increase the Share of Renewables in Office Buildings. Energies 2021, 14, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).