1. Introduction

Left ventricular hypertrabeculation (LVHT) or non-compaction (LVNC) is characterised by prominent left ventricular trabeculae and deep intertrabecular recesses [

1]. The American Heart Association considers LVNC as a genetic cardiomyopathy [

2]. Until the release of the 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies [

3], the European Society of Cardiology categorised LVHT (LVNC) as unclassified cardiomyopathy [

4]. Currently, The Task Force does not classify left ventricular non-compaction as cardiomyopathy but as a phenotypic trait that may occur alone or with other conditions, such as developmental abnormalities, ventricular hypertrophy, dilation, or systolic dysfunction. Due to the absence of morphometric evidence for ventricular compaction in humans [

5,

6], the term "hypertrabeculation" is preferred, especially when the condition is transient or appears in adulthood. Non-familial and sporadic forms have been described in highly trained athletes [

7].

The clinical presentation of LVHT varies from asymptomatic patients to patients with ventricular arrhythmias, thromboembolism, heart failure, and sudden cardiac death. However, there is increasing data about over-diagnosing this cardiomyopathy in an athletic population due to the physiologic adaptation to the extreme preload and afterload conditions characteristic of intense athletic participation [

8].

Gold standard diagnostic criteria for LVHT are currently lacking, and proposed imaging-based criteria have created an epidemic of overdiagnosis in low-risk populations. Athletes suffer significant false-positive rates, and current evidence suggests that this entity may be related to cardiac adaptation to increased preload. We present a clinical case of physiological hypertrabeculation of the left ventricle in an athlete and the contemporary knowledge and current controversies regarding left ventricular hypertrabeculation.

2. Case Presentation

A 21-year-old male, with no prior medical history, was hospitalised after a syncope that occurred during the marathon race. He lost consciousness after running 8 kilometres. Currently, the patient does not take any medications regularly, but during adolescence, he took various supplements while exercising. He denies any recent viral illness. There is no family history of premature cardiovascular deaths. Physical examination on admission was within normal limits, while electrocardiogram (ECG) showed the partial right bundle branch block. Additionally, blood tests indicated elevated cardiac biomarkers (troponin I, creatine kinase MB fraction, B-type natriuretic peptide, myoglobin), which could suggest myocyte and muscle injury as a consequence of exercise-induced stress (

Table 1).

Initially, transthoracic echocardiography was performed (Supplemental Videos 1-3). It showed prolapse of both mitral valve cusps with mild mitral insufficiency. Additionally, Ist degree left atrial dilatation and nondilated left ventricle with a normal ejection fraction of around 61% (as calculated by biplane Simpson) with an increased trabeculation of both left and right ventricles was noticed.

Video I. Transthoracic echocardiography: 4 chamber heart view. Video II. Transthoracic echocardiography: modified 4 chamber heart view with zoomed both ventricles. Video III. Transthoracic echocardiography: short axis at the midventricular level.

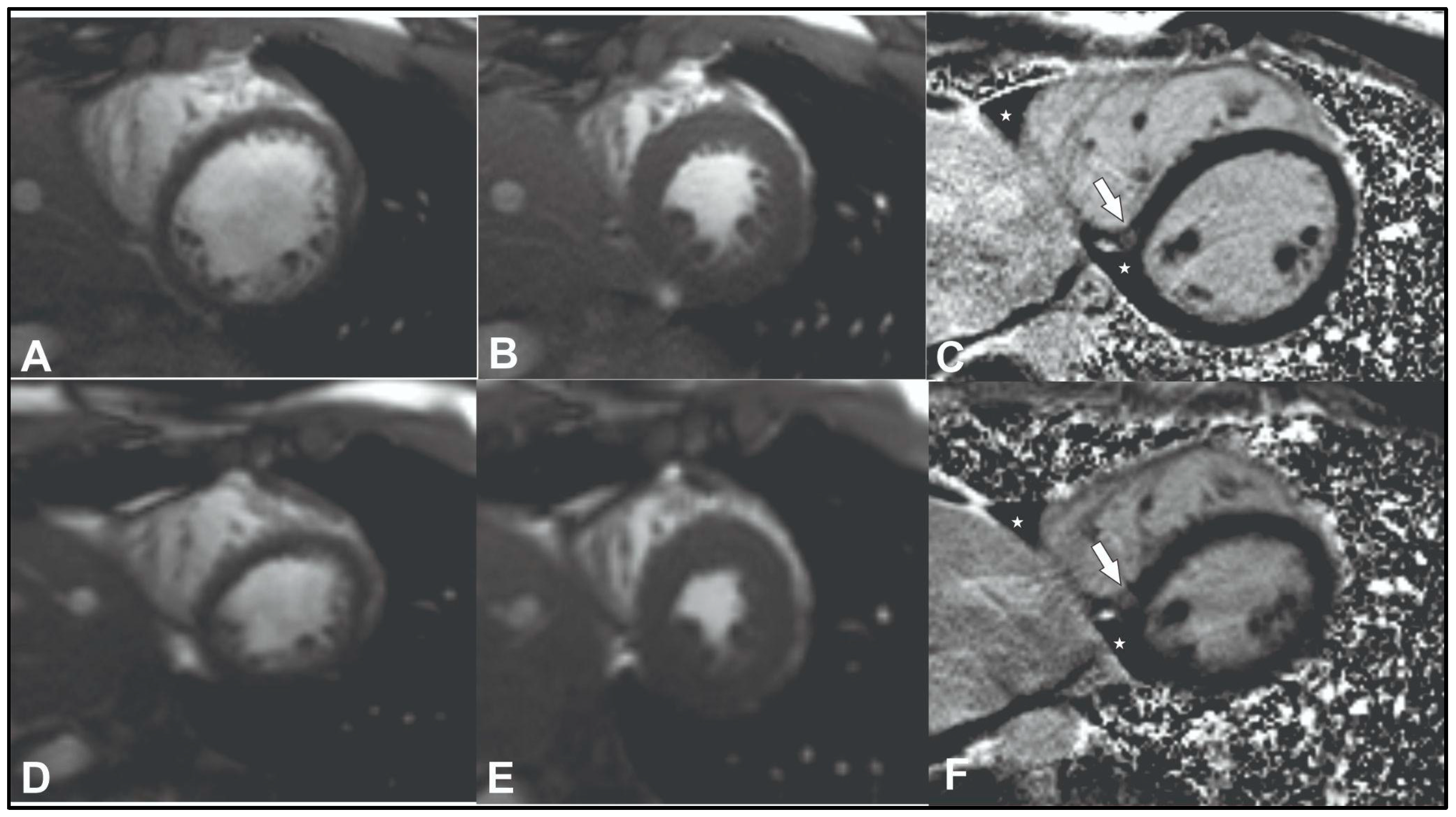

To exclude coronary artery pathology or anomalies computed tomography angiography was performed (Supplemental Video 4). No changes in coronary vessels were found. Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) was performed to assess structural and functional cardiac changes and to exclude cardiomyopathies. The latter test showed slight LV dilatation (left ventricular end-diastolic volume index (EDVI) 104 ml/m² (normal range <92), left ventricular end-systolic volume index (ESVI) 47 ml/m² (normal range <30), borderline LV systolic function (55 %, normal range >55%), and left signs of ventricular non-compaction. Non-compacted to compacted myocardium ratio was up to 2.6 in diastole (Supplemental Videos 5-7,

Figure 1 A-C). According to Petersen's criteria, a normal ratio of non-compacted to compacted myocardium should be <2.3 in diastole [

9]. A nonspecific focus of fibrosis was also detected on late gadolinium enhancement images at the inferior left and right ventricle insertion points (

Figure 1C, white arrow).

Video IV. Coronary artery computed tomography angiography representing normal coronary arteries

After a comprehensive review of the patient's medical history, it was determined that the patient had experienced positional syncope. As a result, a tilt table test was performed, resulting in the diagnosis of mixed-type vasovagal syncope. 24-hour Holter monitoring was performed and showed sinus rhythm with a heart rate (HR) of 28 – 91 beats per minute (bpm). Short bradycardia episodes with HR less than 25 bpm were observed. The average daily HR was 41 bpm.

Video V. Cardiac magnetic resonance cine (SSFP) sequence at admission: 4 chamber heart view representing left ventricular and right ventricular hypertrabeculation. Video VI. Cardiac magnetic resonance cine (SSFP) sequence at admission: short axis view at midventricular to an apical level representing an increase in left ventricular noncompacted to compacted layer ratio in lateral and inferior walls. Video VII. Cardiac magnetic resonance cine (SSFP) sequence at admission: short axis view at an apical level representing an increase in left ventricular noncompacted to compacted layer ratio in all walls except septum.

At that time, it was concluded that the patient may have physiological remodelling of the left ventricle due to his high activity in endurance sports. Also, it was strongly recommended to discontinue the use of various stimulants such as caffeine and reduce his physical activity from high to moderate or/and mild in order to reduce the incidence of syncope. No anticoagulants or antiaggregants were prescribed.

After 2 years of follow-up, the patient underwent follow-up examination and additional CMR which revealed reverse remodelling of the left ventricle with a decrease in left ventricular dilatation (EDVI from 104 to 97 ml/m² (normal range <92), ESVI from 47 to 40 ml/m² (normal range <30), LV ejection fraction within the normal range (58%) and left ventricular myocardium with normal non-compacted to compacted myocardium ratio in diastole – 1.9 (normal range <2.3) (

Figure 1 D-F, Supplemental Videos 8-10). The patient reported no recurrence of syncopal episodes.

Video VIII. Cardiac magnetic resonance cine (SSFP) sequence at 2 years follow-up: 4 chamber heart view representing a decrease in left ventricular end-diastolic diameter and noncompacted to compacted layer ratio. Video IX. Cardiac magnetic resonance cine (SSFP) sequence at 2 years follow-up: short axis view at midventricular to an apical level representing a decrease in left ventricular end-diastolic diameter and noncompacted to compacted layer ratio. Video X. Cardiac magnetic resonance cine (SSFP) sequence at 2 years follow-up: short axis view at an apical level representing a decrease in left ventricular end-diastolic diameter and noncompacted to compacted layer ratio.

4. Discussion

Left ventricular hypertrabeculation (LVHT) is a complex and under-researched heart condition. The diagnosis of LVHT has increased significantly due to advancements in imaging techniques, yet there remains considerable debate over its diagnostic criteria and management [

10]. Clinicians and scientists around the globe have advanced our understanding of the genetics, diagnostics, therapeutics, and outcomes for adult and pediatric patients with LVHT. Recent studies have shown that LVHT, previously underestimated in prevalence, is more common than thought, affecting 0.14% to 0.27% of the general population and 9.5% of children with cardiomyopathies [

10]. The condition is diagnosed more frequently due to improved awareness and imaging technology. Isolated LVHT has been found in up to 8% of athletes, suggesting a potential overlap with physiological adaptations in this group [

10].

Clinically, left ventricular hypertrabeculation (LVHT) can present with a wide range of symptoms, from none to heart failure, palpitations, chest pain, and, in rare cases, arrhythmias or sudden cardiac death [

8]. Syncope with exertion is particularly common, possibly due to the increased demands on the body, especially during elite athletic events. On physical examination, vital signs may show bradycardia, hypotension, or tachyarrhythmias. A cardiac examination is often normal but may reveal arrhythmias, murmurs, signs of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), or congestive heart failure [

8]. In some cases, isolated LVHT could be an adaptive response to training and may not require further evaluation or restrictions from sports if the patient is asymptomatic and has no concerning findings (e.g., arrhythmias, abnormal stress test, or depressed left ventricular function). However, symptomatic patients should be excluded from sports and closely monitored for potential risks such as heart failure, sudden cardiac death, and thromboembolism.

The prognosis of left ventricular hypertrabeculation (LVHT) remains uncertain, despite it being recognised as a clinical condition for over 30 years. Recent studies indicate that overall survival is lower in patients with LVHT compared to the expected survival of age- and sex-matched individuals from the general U.S. population. However, patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction and isolated apical noncompaction have a survival rate similar to that of the general population [

11,

12].

Guidelines from the American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology (ACC) recommend that asymptomatic athletes with normal systolic function and no significant arrhythmias may participate in competitive sports [

13]. However, those with impaired function or arrhythmias should be limited to low-intensity sports until more data are available.

A recent study involving 1,492 Olympic elite athletes across various sports disciplines who underwent electrocardiograms, echocardiograms, and exercise stress tests found that left ventricle trabeculations (LVT) were common, occurring in 29% of participants, particularly in male, Afro-Caribbean, and endurance athletes [

14]. LVTs in this population were interpreted as a manifestation of adaptive remodelling associated with elite athletic training. The study concluded that in the absence of clinical abnormalities such as left ventricular systolic or diastolic impairment, electrocardiogram repolarization abnormalities, or a family history of cardiomyopathy, LVTs in athletes are of benign clinical significance and do not require further investigation. In addition, this

prospective study suggested that recreational marathon running does not increase left ventricular trabeculation [

15]. However, further investigations are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Applying cut-off values from published LV hypertrabeculation criteria to young, healthy individuals has a potential risk for overdiagnosis. It has previously been shown that younger individuals possess greater amounts of apical trabeculation [

16,

17] but age-specific normative or cut-off values for pathological LV trabeculation do not currently exist. In this sample of healthy subjects, excessive trabeculation was found predominantly at the LV apex, which is recognized as the most commonly non-compacted segment [

9] and was detected with greater sensitivity by Chin [

18] and Captur [

19] using apical fractal dimension (FD) criteria. A higher prevalence of positive Chin [

18] as compared to Jenni [

20] criteria has previously been reported in Olympic athletes with prominent trabeculation [

21]. The fractal dimension (FD) quantifies how thoroughly a complex structure fills space. Its value is constrained by the structure's topological dimension. For example, in two-dimensional imaging, endocardial borders are more complex than straight lines, giving them an FD greater than 1. However, since they don’t completely occupy the two-dimensional space, their FD remains below 2. Thus, the FD for an endocardial border consistently falls between 1 and 2, representing a non-integral value. In left ventricular hypertrabeculation (LVHT), excessive trabeculations result in a highly irregular endocardial border. Fractal analysis of these borders in LVHT is expected to produce a higher FD compared to normal hearts.

Studies in athletes have reported prominent trabeculation, raising concerns about a diagnostic grey zone between LVHT and exercise-induced remodelling [

22]. Severe cases in clinical practice suggest LVHT might be a distinct pathology, as the extent of trabeculation exceeds what could arise from adaptation alone. While adult myocardium can remodel via myocyte hypertrophy, its limited proliferative capacity makes extensive de novo trabeculation unlikely. Most cases likely reflect normal trabeculation variations influenced by ventricular geometry and loading conditions. Clinical evaluations, including symptoms, family history, function, arrhythmias, and CMR findings, suggest only 0.1% of cases align with LVHT, with most being normal or non-cardiomyopathic. This supports the idea that prominent trabeculation in athletes is often exercise-induced remodelling.

In this case, insertion point fibrosis was detected on late gadolinium enhancement images at the inferior left and right ventricles (Figure 1C, white arrow). Insertion point fibrosis is frequently observed in athletes irrespective of age [

23,

24]

. One hypothesis suggests this pattern may result from pressure or volume overload in the right ventricle during intense exercise, causing microinjuries that manifest as late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) [

25]

. Generally, it is considered to be benign and non-prognostic [

26]

. In healthy elderly individuals, insertion point fibrosis may represent a normal ageing process and is often deemed an incidental finding when unaccompanied by other signs of cardiac damage [

27]

.

Increased cardiac troponin levels following exercise have been documented in athletes across various sports [

28,

29]

. These increases are temporary and generally return to baseline within 48-72 hours after exercise [

30]

. While the exact mechanisms behind exercise-induced troponin release remain unclear [

31]

, recent research suggests that activities such as marathon running may impact cardiomyocyte integrity [

32]

, potentially leading to the leakage of cytosolic troponin fragments [

33]

. Further investigation is required to determine whether specific groups (based on factors such as age, sex, or sports discipline) with exercise-induced troponin elevations might be at heightened cardiovascular risk [

34]

.

In this case, LV hypertrabeculation reached its maximum expression at the peak of physical conditioning and decreased two years after the detraining period. This suggests that LV hypertrabeculation occurred during the marathon training period as a response to the intensity and volume of the training load. These changes represent adaptive mechanisms that can regress during detraining.

5. Conclusions

Isolated LVHT may be an adaptive mechanism to training and may not require further evaluation or restriction from sports if the patient is asymptomatic and there are no other high-risk features (e.g., depressed LV function). Symptomatic patients should be barred from sports participation and followed closely for risk of heart failure, sudden cardiac death, and thromboembolism. Latest data suggests that left ventricular hypertrabeculation can be induced by exercise and it represents a normal physiological adaptation in the athletic heart. In this case, an increased preload resulted in eccentric left ventricular (LV) remodelling, accentuating trabeculations. After the detraining period, eccentric LV remodelling was reverted to normal (as evidenced by a decrease in the end-diastolic volume and its index), and the trabeculations collapsed at their base. Consequently, the increased non-compacted to compacted myocardium ratio can no longer be measured. Isolated hypertrabeculation, without associated clinical or imaging risk factors, is not recognised as a definitive indicator of elevated cardiac risk. Meanwhile, caution should be exercised before diagnosing LVHT in an athlete based solely on trabeculation appearance.

Author Contributions

Validation, R.J., R.S., P.S. and S.G.; formal analysis, R.J.; resources, R.S., S.G.; data curation, R.S., P.S. and S.G.; writing—original draft preparation, R.J.; writing—review and editing, R.S., P.S. and S.G.; visualization, S.G. and R.J.; supervision, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics review and approval were waived for this study due to the form of the article. In this case report, we just describe the clinical observations.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jenni R, Hoechlin EN, van der Loo B. Isolated ventricular non-compaction of the myocardium in adults. Heart. 2007 Jan;93(1):11–5. [CrossRef]

- Maron BJ, Towbin JA, Thiene G, Antzelevitch C, Corrado D, Arnett D, Moss AJ, Seidman CE, Young JB; American Heart Association; Council on Clinical Cardiology, Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee; Quality of Care and Outcomes Research and Functional Genomics and Translational Biology Interdisciplinary Working Groups; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Contemporary definitions and classification of the cardiomyopathies: an American Heart Association Scientific Statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee; Quality of Care and Outcomes Research and Functional Genomics and Translational Biology Interdisciplinary Working Groups; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2006 Apr 11;113(14):1807-16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbelo, Alexandros Protonotarios, Juan R Gimeno, Eloisa Arbustini, Roberto Barriales-Villa, Cristina Basso, Connie R Bezzina, Elena Biagini, Nico A Blom, Rudolf A de Boer, Tim De Winter, Perry M Elliott, Marcus Flather, Pablo Garcia-Pavia, Kristina H Haugaa, Jodie Ingles, Ruxandra Oana Jurcut, Sabine Klaassen, Giuseppe Limongelli, Bart Loeys, Jens Mogensen, Iacopo Olivotto, Antonis Pantazis, Sanjay Sharma, J Peter Van Tintelen, James S Ware, Juan Pablo Kaski, ESC Scientific Document Group, 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies: Developed by the task force on the management of cardiomyopathies of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), European Heart Journal, Volume 44, Issue 37, 1 October 2023, Pages 3503–3626. [CrossRef]

- Elliott P, Andersson B, Arbustini E, Bilinska Z, Cecchi F, Charron P, et al. Classification of the cardiomyopathies: a position statement from the european society of cardiology working group on myocardial and pericardial diseases. European Heart Journal. 2008 Jan 1;29(2):270–6. [CrossRef]

- Faber JW, D’Silva A, Christoffels VM, Jensen B. Lack of morphometric evidence for ventricular compaction in humans. J Cardiol 2021;78:397–405. [CrossRef]

- Anderson RH, Jensen B, Mohun TJ, Petersen SE, Aung N, Zemrak F, et al. Key questions relating to left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy: is the emperor still wearing any clothes? Can J Cardiol 2017;33:747–757. [CrossRef]

- Gati S, Chandra N, Bennett RL, Reed M, Kervio G, Panoulas VF, et al. Increased left ventricular trabeculation in highly trained athletes: do we need more stringent criteria for the diagnosis of left ventricular non-compaction in athletes? Heart. 2013 Mar 15;99(6):401–8. [CrossRef]

- Coris EE, Moran BK, De Cuba R, Farrar T, Curtis AB. Left Ventricular Non-Compaction in Athletes: To Play or Not to Play. Sports Med. 2016 Sep;46(9):1249–59. [CrossRef]

- S.E. Petersen, J.B. Selvanayagam, F. Wiesmann, M.D. Robson, J.M. Francis, R.H. Anderson, et al. Left ventricular non-compaction: insights from cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol., 46 (1) (2005), pp. 101-105. [CrossRef]

- John L. Jefferies, MD Left Ventricular Noncompaction Cardiomyopathy: New Clues in a Not So New Disease? Journal of the American Heart AssociationVolume 10, Issue 2, 19 January 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ganga HV, Thompson P. Sports Participation in non-compaction cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48: 1466–71. [CrossRef]

- Vaibhav R. Vaidya, MBBS. Long-Term Survival of Patients With Left Ventricular Noncompaction. Journal of the American Heart Association. Volume 10, Issue 2, 19 January 2021. [CrossRef]

- Maron BJ, Udelson JE, Bonow RO, et al. Eligibility and disqualification recommendations for competitive athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities: Task Force 3: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy and other cardiomyopathies, and myocarditis: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(21):2362–71. [CrossRef]

- Giuseppe Di Gioia, Simone Pasquale Crispino, Sara Monosilio, Viviana Maestrini, Antonio Nenna, Alessandro Spinelli, Erika Lemme, Maria Rosaria Squeo, Antonio Pelliccia, Left Ventricular Trabeculation: Arrhythmogenic and Clinical Significance in Elite Athletes, Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography, Volume 37, Issue 6, 2024, Pages 577-586, ISSN 0894-7317. [CrossRef]

- Andrew D'Silva, Gabriella Captur, Anish N. Bhuva, Siana Jones, Rachel Bastiaenen, Amna Abdel-Gadir, Sabiha Gati, Jet van Zalen, James Willis, Aneil Malhotra, Irina Chis Ster, Charlotte Manisty, Alun D. Hughes, Guy Lloyd, Rajan Sharma, James C. Moon, Sanjay Sharma, Recreational marathon running does not cause exercise-induced left ventricular hypertrabeculation, International Journal of Cardiology, Volume 315, 2020, Pages 67-71, ISSN 0167-5273. [CrossRef]

- Z. Bentatou, M. Finas, P. Habert, F. Kober, M. Guye, S. Bricq, et al. Distribution of left ventricular trabeculation across age and gender in 140 healthy Caucasian subjects on MR imaging. Diagn Interv Imaging., 99 (11) (2018), pp. 689-698. [CrossRef]

- K. Dawson, A.M. Maceira, V.J. Raj, C. Graham, D.J. Pennell, P.J. Kilner Regional thicknesses and thickening of compacted and trabeculated myocardial layers of the normal left ventricle studied by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging., 4 (2) (2011), pp. 139-146. [CrossRef]

- Chin T.K., Perloff J.K., Williams R.G., Jue K., Mohrmann R. Isolated noncompaction of left ventricular myocardium. A study of eight cases. Circulation. 1990;82(2):507–513. [CrossRef]

- Captur G., Muthurangu V., Cook C., Flett A.S., Wilson R., Barison A. Quantification of left ventricular trabeculae using fractal analysis. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2013;15:36. [CrossRef]

- Jenni R., Oechslin E., Schneider J., Attenhofer Jost C., Kaufmann P.A. Echocardiographic and pathoanatomical characteristics of isolated left ventricular non-compaction: a step towards classification as a distinct cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2001;86(6):666–671. [CrossRef]

- Caselli S., Ferreira D., Kanawati E., Di Paolo F., Pisicchio C., Attenhofer Jost C. Prominent left ventricular trabeculations in competitive athletes: a proposal for risk stratification and management. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016;223:590–595. [CrossRef]

- Abela M., D’Silva, A. Left Ventricular Trabeculations in Athletes: Epiphenomenon or Phenotype of Disease?. Curr Treat Options Cardio Med 20, 100 (2018). [CrossRef]

- van de Schoor FR, Aengevaeren VL, Hopman MT, et al. Myocardial fibrosis in athletes. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:1617-1631. [CrossRef]

- Androulakis E, Swoboda PP. The role of cardiovascular magnetic resonance in sports cardiology; current utility and future perspectives. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2018;20:86. [CrossRef]

- Małek ŁA, Barczuk-Falęcka M, Werys K, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance with parametric mapping in long-term ultra-marathon runners. Eur J Radiol. 2019;17:89-94. [CrossRef]

- Klopotowski M, Kukula K, Malek LA, et al. The value of cardiac magnetic resonance and distribution of late gadolinium enhancement for risk stratification of sudden cardiac death in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiol. 2016;68:49‐56. [CrossRef]

- Grigoratos C, Pantano A, Meschisi M, et al. Clinical importance of late gadolinium enhancement at right ventricular insertion points in otherwise normal hearts. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1007/s10554-020-01783-y.

- La Gerche A, Connelly KA, Mooney DJ, MacIsaac AI, Prior DL. Biochemical and functional abnormalities of left and right ventricular function after ultra-endurance exercise. Heart. 2008;94: 860–866. [CrossRef]

- Eijsvogels T, George K, Shave R, et al. Effect of prolonged walking on cardiac troponin levels. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:267–272. [CrossRef]

- Scherr J, Braun S, Schuster T, et al. 72-h kinetics of high-sensitive troponin T and inflammatory markers after marathon. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1819–1827. [CrossRef]

- Mair J, Lindahl B, Hammarsten O, et al. How is cardiac troponin released from injured myocardium? Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2018;7: 553–560. [CrossRef]

- Aengevaeren VL, Froeling M, Hooijmans MT, et al. Myocardial injury and compromised cardiomyocyte integrity following a marathon run. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2020;13:1445–1447. [CrossRef]

- Vroemen WHM, Mezger STP, Masotti S, et al. Cardiac troponin T: only small molecules in recreational runners after marathon completion. J Appl Lab Med. 2019;3:909–911. [CrossRef]

- Omland T, Aakre KM. Cardiac troponin increase after endurance exercise. Circulation. 2019;140:815–818. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).