1. Introduction

The origins of the Internet trace back [

1] to efforts to interconnect computer networks in the 1950s. J.C.R. Licklider of MIT first proposed the idea of a universal network in 1962. He envisioned a globally interconnected set of computers through which everyone could quickly access data and programs from any site. The U.S. Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) funded the development of the ARPANET in 1969, which was the first network to implement packet switching and laid the groundwork for the modern Internet. Today, the Internet is a global network that connects billions of devices and is integral to modern communication, collaboration, commerce, and entertainment on a global scale.

1.1. Integration with Telecommunications

Today, the Internet and telecommunications networks are highly integrated. Telecommunications companies provide Internet services; the same infrastructure is used for voice and data transmission. This integration has transformed communication, making the Internet an essential part of the global telecommunications network. Voice over IP (VoIP) and broadband have further blurred the lines between traditional telecommunications and the Internet. VoIP allows voice communication over the Internet, while broadband provides high-speed Internet access through telecommunications infrastructure.

1.2. Challenges and Issues

While the Internet has undoubtedly transformed our lives in many positive ways, there are several downsides. The anonymity of the Internet has resulted in abusive behavior, including trolling, stalking, and cyberbullying. Cyber breaches have become common, threatening privacy, and identity theft has become a significant issue affecting millions of people each year [

2]. In 2021, about 23.9 million people (9% of U.S. residents age 16 or older) reported being victims of identity theft. Nearly 42 million Americans were victims of identity fraud in 2021. Across all incidents of identity theft reported in 2021, about 59% of victims experienced a financial loss of

$1 or more. These victims had financial losses totaling

$16.4 billion.

Government efforts through laws and regulations, increased public awareness, and some technology-based defense tools are attempting to address these issues. However, they fall short of providing the safeguards required. There are several attempts to address these issues with a next-generation Internet with an architecture that enhances the Internet [

3,

4,

5]. These include:

Semantic Web: Makes it easier to find and link related information.

Future Internet Architectures: Developed using both clean-slate approaches and incremental improvements, considering various scenarios, including seamless mobility, ad hoc networks, sensor networks, the Internet of Things (IoT), and new paradigms like content and user-centric networks.

Integration of Blockchain Technology: Enhances security and trust in online transactions.

Development of the Metaverse: This represents the Internet’s next frontier, combining augmented reality, virtual reality, and other emerging technologies.

1.3. Foundational Issues

However, several arguments point out the current problems associated with the complexity and vulnerability to hacking and fraud on the Internet and associated information systems using general-purpose computers. These are not merely operational issues but stem from the foundational shortcomings of the Turing machine computing model’s stored program control (SPC) implementation [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. These shortcomings arise from:

Limitations of the Church-Turing Thesis: Dealing with finite resources available for computing processes.

Inability to Model Distributed Processes: Communicating asynchronously with each other (CAP theorem limitation).

Logical Limits: Arise when “trying to get general-purpose computers to model a part of the world that includes themselves [

6] p. 215.

1.4. New Insights from the General Theory of Information (GTI)

In this context, the General Theory of Information (GTI) suggests a new approach based on the issues of safety and security [

18,

19]. GTI focuses on how biological systems manage their safety and security with self-regulating processes with autopoietic and cognitive behaviors. Autopoiesis refers to the behavior of a system that replicates itself and maintains identity and stability while its components face fluctuations caused by external influences. Autopoiesis enables them to use the specification in their genomes to instantiate themselves using matter and energy transformations. They reproduce, replicate, and manage their stability using cognitive processes. Cognition allows them to process information into knowledge and use it to manage interactions between various constituent parts within the system and its interaction with the environment. Cognition uses multiple mechanisms to gather information from different sources, convert it into knowledge, develop a history through memorizing the transactions, and identify new associations through their analysis. Organisms have developed various forms of cognition.

GTI suggests a new schema-based approach to infusing current-generation information technologies with a service-oriented architecture and added autopoietic and cognitive behaviors. This approach aims to enhance safety and security by mimicking the self-regulating processes found in biological systems.

1.5. Structure of This Paper

The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 examines the foundational issues with the current Internet architecture.

Section 3 reviews GTI and the service-oriented Internet proposed by Burgin and Mikkilineni and its potential implementation architecture.

Section 4 discusses the implications of the new architecture and compares it with other comparable approaches.

Section 5 presents observations and potential future directions.

2. Foundational Issues with the Current Internet

Today’s computing processes have evolved to execute highly complex algorithms by processing vast amounts of data, which in turn generate new representations of system knowledge. Here, "knowledge" refers to the state of a system, including its various entities, their relationships, and the evolution of these entities through interactions that alter their state.

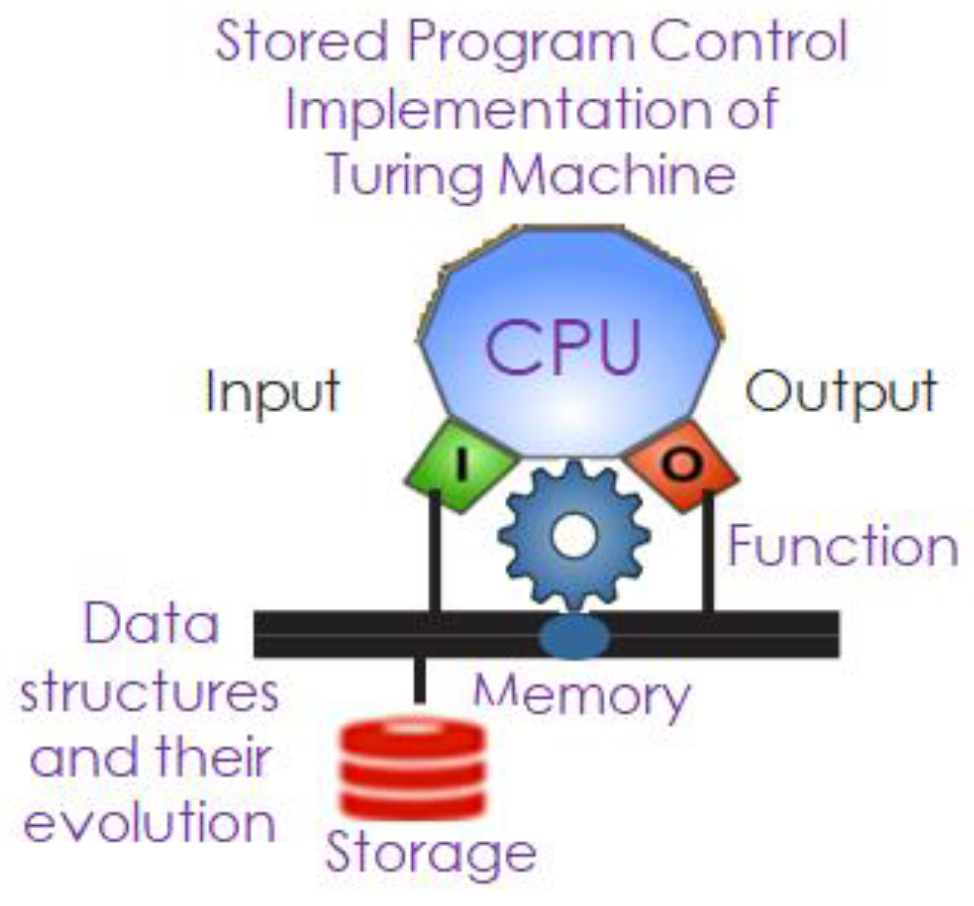

These processes are executed using digital computing machines that implement stored program-controlled Turing machines. A program, which embodies an algorithm, operates on data represented as binary sequences (0s and 1s). An algorithm’s "intent" is defined by its sequence of steps, but the resources and time required to execute this intent depend on many factors outside the algorithm’s specification. Computing resources such as speed and memory critically influence the outcome of execution. The nature of the algorithm itself also dictates the resources required.

While modern hardware and software architectures implement sophisticated algorithms to model physical systems, reason about them, and control them, resource optimization to enhance efficiency remains independent of the algorithm’s power. Mark Burgin, in his book Super-Recursive Algorithms [

16], emphasizes that “efficiency of an algorithm depends on two parameters: power of the algorithm and the resources used in the solution process. If the algorithm does not have access to necessary resources, it cannot solve the problem under consideration.”

The efficiency of computation execution hinges on managing the dynamic relationship between hardware and software, monitoring fluctuations, and adjusting resources accordingly.

The Turing machine initially started as a static, closed system, akin to a single cell in biology, designed for computing algorithms corresponding to mathematical worldviews. Introducing an operating system transforms the Turing machine’s implementation into a workflow of computations. Each process now behaves as a new Turing machine, managed by the operating system, which acts like a series of management Turing machines dedicated to controlling other computing Turing machines based on defined policies.

This dynamic is analogous to the evolution of multi-cellular organisms, where individual cells establish common management protocols to achieve shared goals with shared resources. Operating systems communicate with processes using shared memory, providing fault, configuration, accounting, performance, and security management through abstractions like addressing, alerting, mediation, and supervision.

Von Neumann’s stored program-controlled implementation of the Turing machine ingeniously provides a physical implementation of a cognitive apparatus to represent and transform knowledge via data structures. This implementation allows information to flow between processing structures at a velocity defined by the medium, where information represents the difference between two states of knowledge.

Figure 1.

The digital gene – A Cognitive apparatus executing a process evolution specified by a function or algorithm.

Figure 1.

The digital gene – A Cognitive apparatus executing a process evolution specified by a function or algorithm.

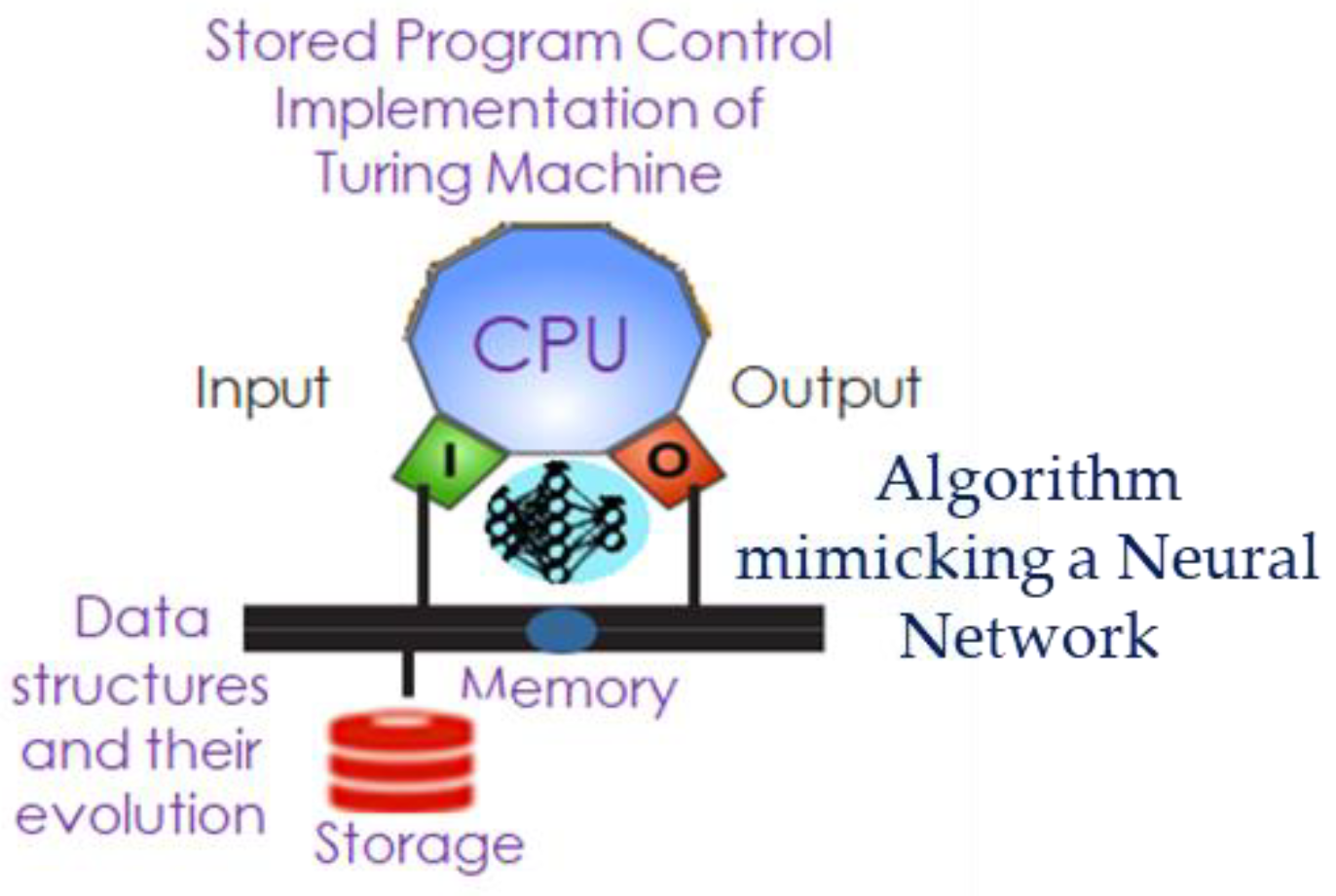

Turing computable functions also include algorithms that define neural networks, which are used to model processes that cannot be described themselves as algorithms, such as voice recognition, video processing, etc. Cognition here comes from the ability to encode how to mimic neural networks in the brain, model, and process information just as neurons in biology do.

Figure 2 shows the digital neuron (executing the cognitive processes that cannot be specified in an algorithm) mimicking the biological systems.

Despite the successes mentioned in the introduction, foundational shortcomings cannot be addressed without changing the computing model.

2.1. Resource Limitations and the Church-Turing Thesis

The Church-Turing thesis establishes boundaries on computing based on resource limitations. All algorithms that are Turing computable fall within these boundaries, which state that “a function on the natural numbers is computable by a human being following an algorithm, ignoring resource limitations, if and only if it is computable by a Turing machine.” Turing computable functions are those described by formal, mathematical rules or sequences of event-driven actions, such as modeling, simulation, and business workflows. Unfortunately, in a distributed computing environment, the availability and performance of software systems depend critically on available resources. Managing the right computing resources (CPU, memory, network bandwidth, etc.) for service transactions requires orchestration across diverse computing infrastructures, often owned by different providers with varying incentives. This complexity adds to the cost of computing, with estimates suggesting that up to 70% of current IT budgets are consumed for ensuring service availability, performance, and security [

20].

1.6. Challenges in Distributed Computing

The complexity of geographically distributed computing environments is compounded by heterogeneous infrastructures and disparate management systems. In large-scale dynamic distributed computations, supported by numerous infrastructure components, the increased probability of component failures introduces non-determinism. For example, Google has observed emergent behavior [

21] in their scheduling of distributed computing resources when dealing with a large number of resources. This non-determinism must be addressed by a service control architecture that separates functional and non-functional aspects of computing.

Fluctuations in computing resource requirements, driven by changing business priorities, workload variations, and real-time latency constraints, demand a dynamic response to adjust computing resources. Current reliance on various orchestrators and management systems cannot scale in a distributed infrastructure without leading to vendor lock-in or requiring a universal standard, which often stifles innovation and competition. Therefore, the evolution of processes delivering application intent necessitates new computing, management, and programming models that unify the management of computing resources and functional fulfillment [

18,

19,

22].

Systems are continuously evolving and interacting. Sentient systems, which can feel, perceive, or experience, evolve using a non-Markovian process, where the probability of a future state depends on both the present state and prior state history. For digital systems to evolve and mimic human intelligence, they must incorporate time dependence and historical context into their process dynamics. Creating systems that can reason about themselves introduces challenges in ensuring consistency and reliability. Self-referential systems can lead to paradoxes and inconsistencies, making it difficult to guarantee their correctness. These systems are inherently complex, as they must handle both primary tasks and meta-level reasoning about their operations, adding layers of complexity to their design and implementation.

The search for self-organizing and self-regulating computers led to the vision of autonomous computing structures, as stated by Paul Horn in 2001 [

23]. He envisioned systems that manage themselves according to an administrator’s goals, with new components integrating as effortlessly as new cells in the human body. These ideas are not science fiction but elements of the grand challenge to create self-managing computing systems.

Louis Barrett [

24] highlights the differences between Turing machines implemented using von Neumann architecture and biological systems. While the computer analogy built on von Neumann architecture has been useful, classic artificial intelligence (or Good Old-Fashioned AI: GOFAI) has had limited success, particularly in areas of cognitive evolution. Turing machines, based on algorithmic symbolic manipulation, excel in tasks like natural language processing, formal reasoning, planning, mathematics, and playing chess. However, they fall short in aspects of cognition that involve adaptive behavior in changing environments.

Barrett suggests that dynamic coupling between various system elements, where changes in one element influence others, must be accounted for in computational models that include sensory and motor functions along with analysis. While such couplings can be modeled and managed using a Turing machine network, the tight integration of observer and observed models with a description of the “self” using parallelism and signaling, common in biology, remains a challenge.

In the next section, we discuss a new computing model derived from GTI that enables the implementation of autopoietic and cognitive computing structures that are self-organizing and self-regulating using a digital genome, just as living systems use the biological genome to build, operate, and manage a living organism.

3. General Theory of Information and the Services-Centric Internet

In essence, the Internet provides a platform on which distributed software applications are deployed, connecting people and devices, managing various workflows, and delivering a wide range of services and information seamlessly across the globe. A distributed information processing structure (application) is a collection of independent computation structures (micro- or mini- or mega- services, immutable or mutable, stateless or stateful) that appear to its users as a single coherent system executing functional requirements defined by business requirements. An example is a three-tier application consisting of a web server, business logic executor, database etc., or a machine learning stack. Distributed computing has evolved significantly, from client-server models to modern cloud computing, enhancing efficiency in business processes through resource sharing. However, this evolution brings challenges like resource contention, node failures, and security issues. Key attributes for designing distributed systems include resiliency, efficiency, and scalability. Resiliency ensures reliable communication and resource management, efficiency focuses on optimal resource utilization and coordination, and scalability allows systems to adapt to changing demands. Despite advancements, as discussed in this paper, current systems struggle with data security and resource management, highlighting the need for a new architectural foundation that addresses these weaknesses. To address data security and resource management challenges in distributed computing, a new architectural foundation should focus on dynamic management, real-time monitoring, automated resource allocation, and end-to-end visibility. This includes implementing unified dashboards, integrated security measures, fault tolerance, disaster recovery, and elastic infrastructure. Additionally, adopting open standards and service-oriented architecture can enhance interoperability and avoid vendor lock-in, ultimately providing a more robust, efficient, and secure environment for distributed applications.

Burgin and Mikkilineni propose a new architecture derived from the General Theory of Information (GTI) [

18], p.149:

"a new three-tier Internet architecture is suggested and its properties are explored. It is oriented at improving the security and safety of the Internet functioning and providing better tools for interaction between consumers and Internet services. The suggested architecture is based on biological analogies, innovative computational models, such as structural machines and grid automata, as well as on the far-reaching general theory of information. The advantages of the suggested technological Internet architecture are explained in comparison with the traditional one.

The suggested approach leads to three directions of its further development. One is the advancement of the theoretical models getting a more exact picture of information processes in big and small computational and communication networks.

Another direction goes into the technological realization of the theoretical findings and practical ideas discussed here.

One more direction is the synthesis of suggested Internet architecture with name-oriented networking or named data networking (NDN) because many of the Internet’s problems are related to names and naming [

25,

26].”

In this paper we discuss how these ideas from GTI have helped in designing, deploying, operating, and managing distributed software applications addressing the foundational shortcomings of the current Implementations. We argue that the two implementations using the structural machine and the knowledge structures derived from GTI [

22,

27,

28] address the foundational shortcomings mentioned in this paper.

Natural and Machine Intelligence

The General Theory of Information (GTI) [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34] provides a unified framework that connects the physical, biological, and digital realms through the concept of information. This theory elucidates how machines and AI can be designed to emulate the cognitive and adaptive functions of biological systems.

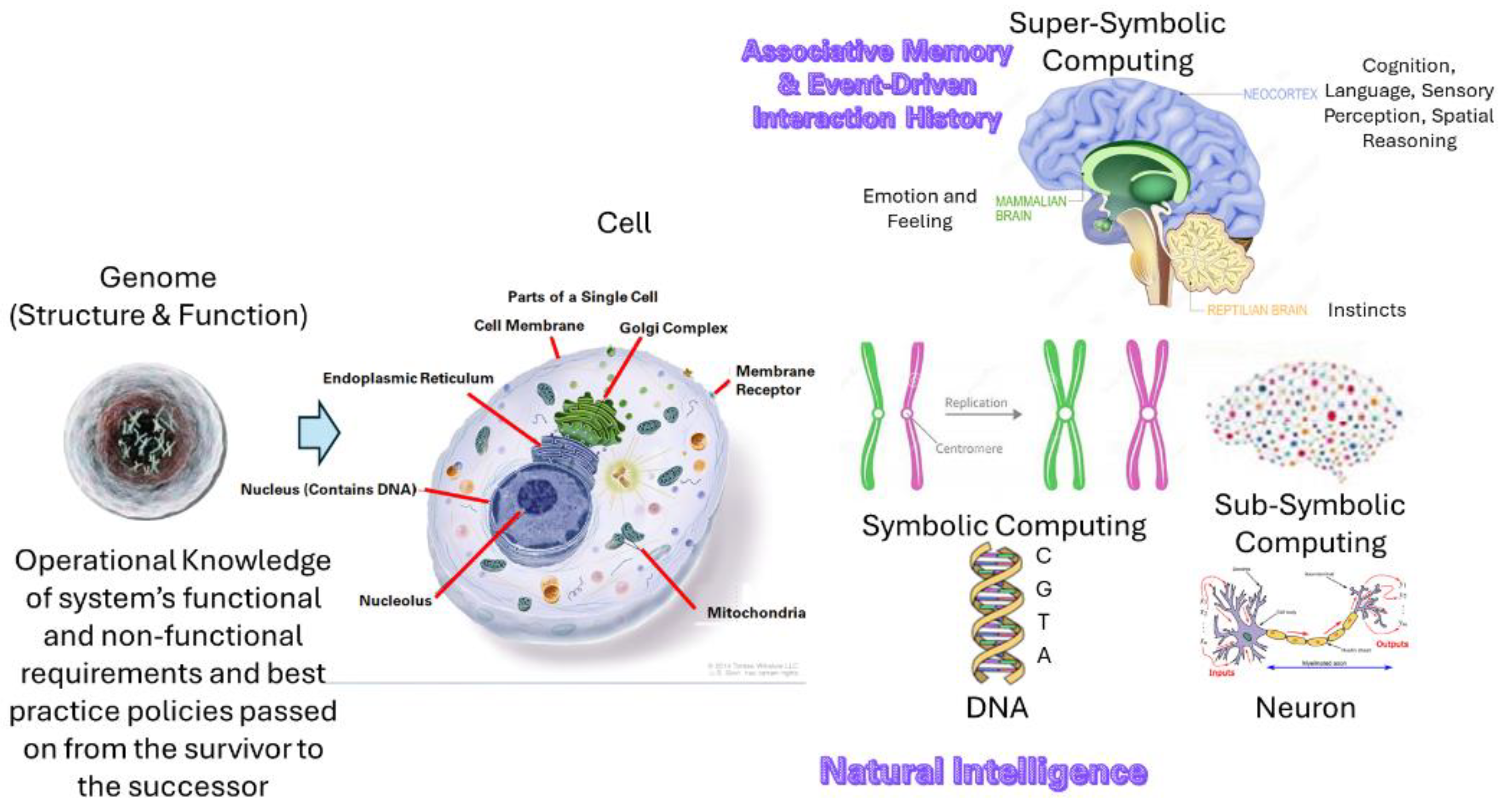

Material structures are the physical entities that exist in the material world, governed by interaction forces that follow the laws of matter and energy transformation. Their evolution adheres to either classical Hamiltonian equations or quantum Schrödinger equations, depending on the nature of the structures. According to GTI, ontological information includes the structure, function, state in phase space and its evolution which is crucial for understanding how these structures and functions develop over time. Ontological information contains the difference between various states of material structures.

GTI posits [

27,

33] that biological systems have evolved to process epistemic information received through their senses, converting it into mental structures (knowledge) that guide self-organization and self-regulation. Information acts as a bridge between material structures (physical entities), mental structures (knowledge created by biological systems), and digital information processing structures (AI and digital computing machines). This bridge facilitates the transfer and transformation of information across different domains.

Figure 3 depicts GTI view of information processing in biological systems where knowledge is stored in the form of associative memory and event-driven transaction history.

Biological systems receive the knowledge required to build, operate, and manage their life processes through their genomes. Genomes encode the instructions for the synthesis of proteins that perform various functions within cells. The structure and function of these systems are represented and processed using symbolic information processing structures in the form of genes. Genes are composed of sequences of nucleotides (adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and thymine (T) in DNA; uracil (U) replaces thymine in RNA). These sequences encode amino acids, which are the building blocks of proteins. This can be seen as symbolic information processing by genes. On the other hand, neurons can be considered as sub-symbolic information processing structures. Neurons communicate via synapses, and their interactions form networks that underpin learning and memory. These structures receive information through their senses and update their knowledge using sub-symbolic information processing structures in the form of neurons. When neurons are activated by sensory signals, they wire together to create or update knowledge stored as associative memory and event-driven transaction history.

To maintain structural stability and interact with their environment, biological systems leverage enhanced cognition through super-symbolic information processing structures in the form of the neocortex. The neocortex is involved in higher-order brain functions such as sensory perception, cognition, spatial reasoning, conscious thought, and motor commands. It uses higher-level knowledge that integrates various knowledge updates received through the senses. The General Theory of Information (GTI) provides a schema and associated operations to depict knowledge representation in the form of named sets or fundamental triads. Knowledge is represented as a multi-layer network of entities, their relationships, and behaviors, which change when events alter the system’s state.

Biological systems manage their functional stability amid fluctuations and instabilities. They make sense of observations and take action using past experiences while observations are still ongoing, optimizing their structure and functional performance. These systems utilize associative memory and event-driven interaction history to make decisions and act effectively.

Digital information processing structures are designed to replicate the functions of mental structures in machines.

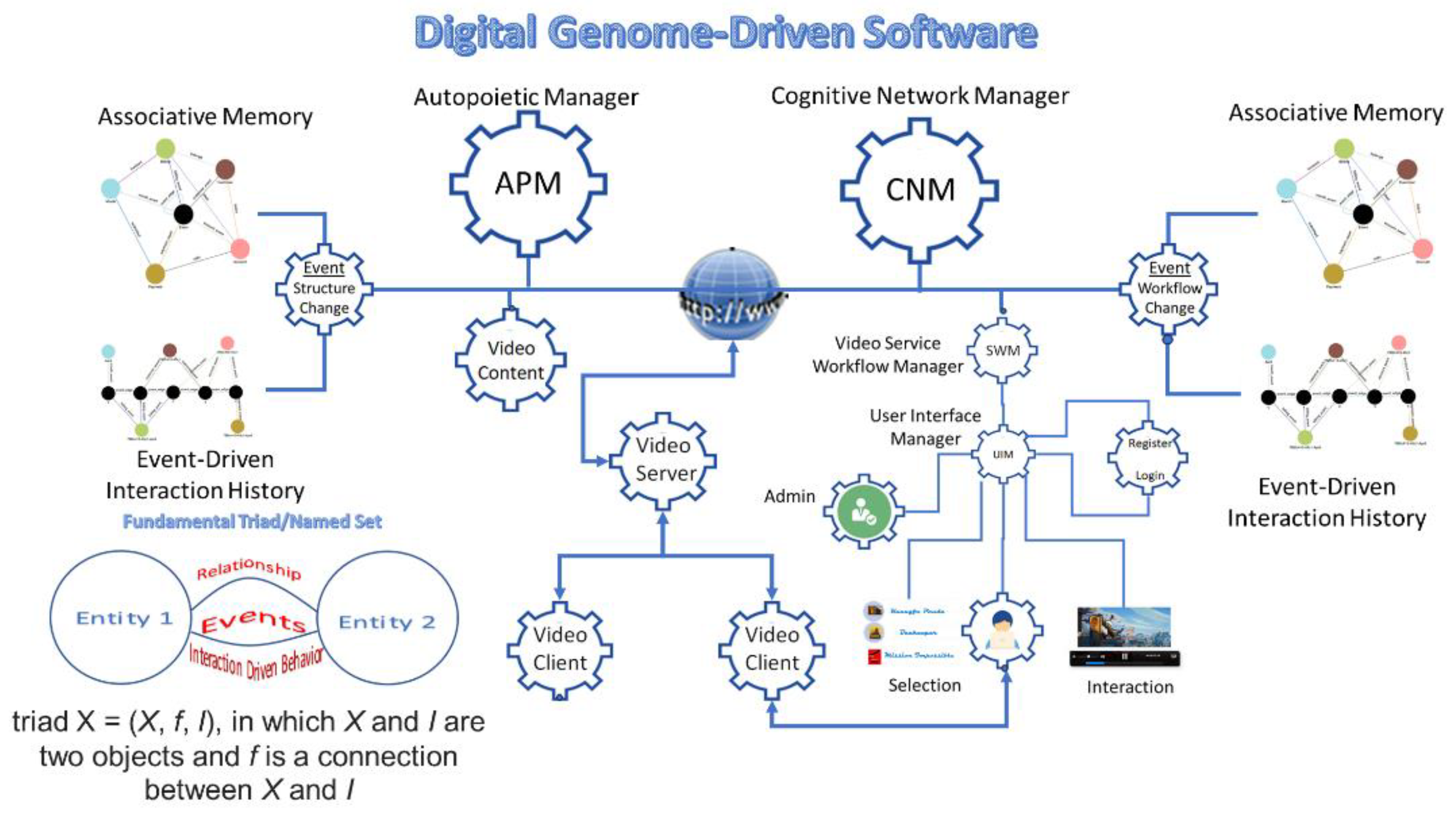

Figure 4 depicts how digital symbolic, sub-symbolic, and super-symbolic information processing structure can be used to build, deploy, operate, and manage distributed software applications.

The General Theory of Information (GTI) [

19,

33] provides a framework that can also model distributed software applications. In this context, the specification of the structure and functions of a distributed software system is defined by its functional and non-functional requirements, along with best practice policies represented as workflows (Digital Genome). Each software component operates as a process with inputs and outputs, similar to a cell in biological systems. These software components function as a society of multi-layered, hierarchical networks of cells, each executing individual processes while collaborating through shared knowledge. They maintain structural stability and interact with their environment using advanced cognitive capabilities.

GTI enables the design of self-organizing and self-regulating distributed software systems that can interpret their observations and take actions while the observations are still ongoing. This allows them to optimize their structure and functionality using associative memory and event-driven interaction history. On the next section, we discuss the prototype implementation of a video on demand (VoD) service as a distributed software application whose structure and functions are deployed, operated and managed using the associative memory and event-driven transaction history.

4. Discussion

Mikkilineni et al., have implemented a prototype of VoD service [

22] using the architecture described in Burgin Mikkilineni Paper [

18]. As stated in the conclusion of their paper [

22], they demonstrated the implementation of the “knowledge representation to construct, operate, and manage a society of autonomous distributed software components with complex organizational structures. The new approach offers practical benefits such as self-regulating distributed application design, development, deployment, operation, and management. Importantly, these benefits are independent of the infrastructure as a service (IaaS) or platform as a service (PaaS) used to execute them, promising a versatile and adaptable solution.

Event-driven interaction history allows for real-time sharing of business moments as asynchronous events. The schema-based knowledge network implementation improves a system’s scalability, agility, and adaptability through the dynamic control and feedback signals exchanged among the system’s components. This architecture separates the traditional sensing, analysis, control, and actuation elements for a given system across a distributed network. It uses shared information between nodes and the nodes that are wired fire together to execute collective behavior.”

The video of the implementation describing the use of associative memory and event-driven transaction history is available [

35] at Digital Genome Implementation Presentations. In this paper, we discuss two extensions implemented; i) that improve the security of the communication between various entities in the distributed application, and ii) deployment of components distributed in two cloud infrastructures (Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Google Cloud Platform (GCP).

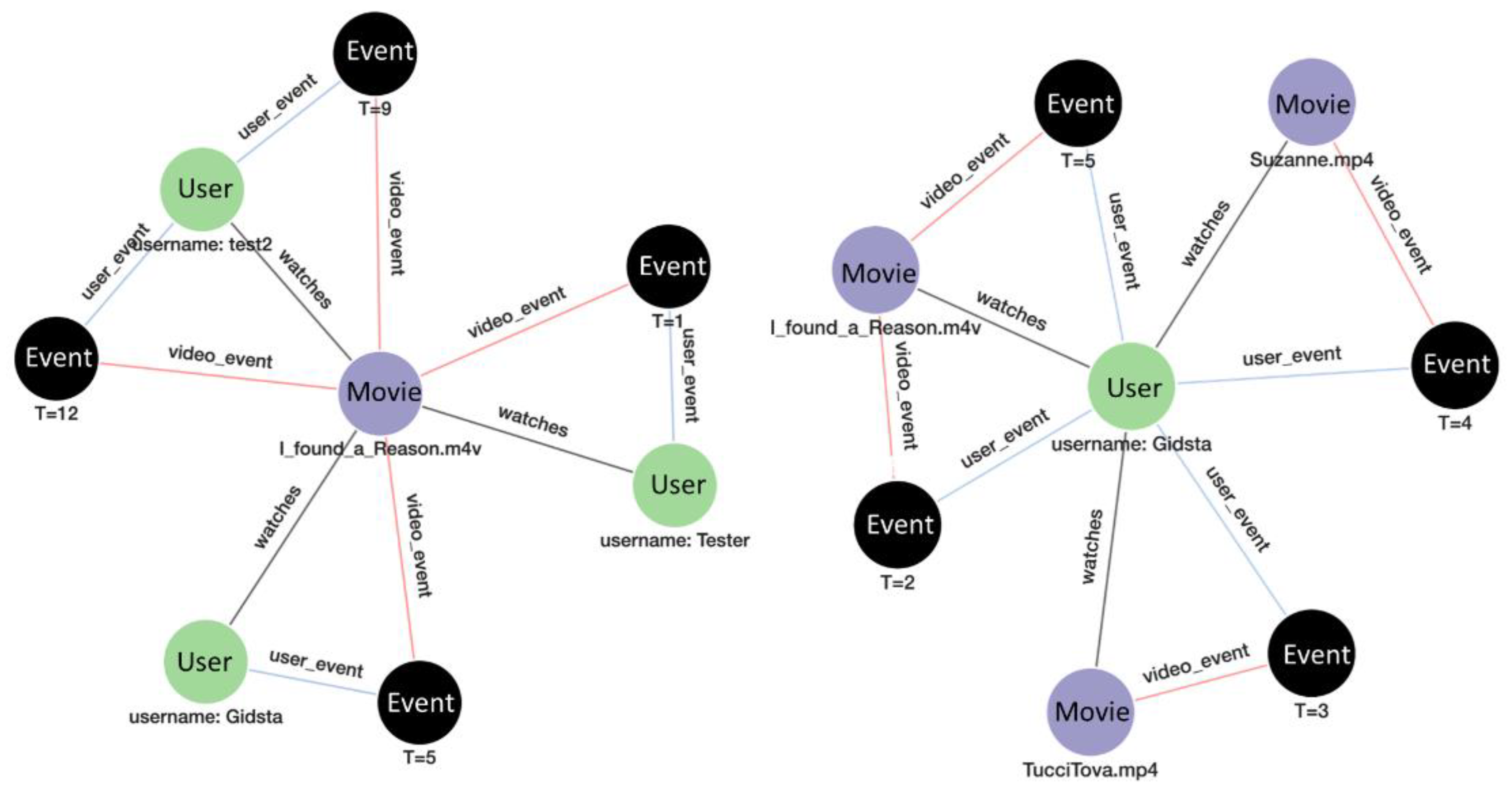

Figure 5 depicts the various entities and their relationships. Each entity is a containerized process which executes various actions based on the knowledge from the digital software genome specification when input is received and sends relevant messages to other wired entities depending on the shared knowledge. The wired nodes fire together to execute collective behavior. In this implementation, the entities of interest are the users and the videos they use from the video content. The user interface management entity manages the user interaction workflow and the video server entity manages the video service delivery workflow. The service workflow manager uses the wired nodes to coordinate the communication across the knowledge network consisting of event managers and associative memory and event-driven interaction history captured in a graph database. As discussed in Burgin-Mikkilineni paper [

19], security is implemented by using private key public key pair and ssh connection management. Each entity uses a private key and shares a public key with other entities with which it is wired.

The deployment and operation scenario is as follows:

The autopoietic manager (APM) receives the list of containerized entities from a docker image repository, and their resource requirements for deployment such as which cloud, credentials, node and edge connection map, etc.

APM deploys the containers as services in the designated clouds and provides the URLs and connection map to the cognitive network manager (CNM) which sets up the connections of the wired nodes.

The service workflow manager coordinates the service node communications using wired connections.

The structural events are captured by the event manager and the associative memory and event-driven interaction history are captured in the graph database. Similarly, workflow events dealing with users and videos are captured by the workflow event manager and the associative memory and the interaction-based history are updated in the graph database.

If deviations occur from normal behavior, the autopoietic and cognitive network managers correct the structural and workflow deviations based on best-practice policies.

The result is a digital genome based software application which is deployed over multiple clouds and its self-regulation is at the service layer independent of IaaS and PaaS providers. The structure is designed based on business requirements. For example, based on recovery time and position objectives (RTO and RPO) the structure can have redundant components on different clouds and auto-failover, auto-scaling, and live migration provide service continuity.

In addition, the workflow associative memory and event-driven interaction history allow us to derive history-based analytics. For example, each user’s behavior is captured and similarly each video history is captured as shown in

Figure 6.

These analytics are used to predict behaviors.

Figure 7.

Event-Driven Interaction History capturing the causal behaviors users and videos.

Figure 7.

Event-Driven Interaction History capturing the causal behaviors users and videos.

5. Conclusions

Mark Burgin’s General Theory of Information (GTI) is a comprehensive framework that aims to unify various forms and manifestations of information:

Super-Symbolic Computing: GTI introduces the concept of super-symbolic computing, which goes beyond traditional symbolic and sub-symbolic computing to incorporate knowledge structures and cognizing oracles. Examples include the autopoietic manager and the cognitive network manager implemented in the VoD prototype.

Digital Genome: GTI provides a model for a digital genome, which specifies the operational knowledge of algorithms executing software life processes. Structure, function, and causal behaviors are represented as a hierarchical multi-layer network with nodes executing various functions and communicating with other nodes using shared knowledge.

Autopoietic and Cognitive Behaviors: By modeling the knowledge representation in biological systems, GTI explains the manifestation of autopoietic (self-maintaining) and cognitive behaviors. A similar knowledge representation schema enables software systems to exhibit these behaviors, enhancing their resilience and adaptability. A comparison of this approach with conventional approach has been discussed extensively [

19,

33]. The foundational shortcomings pointed out in this paper are addressed with the schema-based approach where the computer and the computed work harmoniously to augment human intelligence with machine intelligence.

As Cooper points out [

36], "Computation is about information, and potentially equipped to model the way in which the basic causality of our universe respects and transports information." The General Theory of Information (GTI) bridges the material, mental, and digital worlds with a new model of a society of computational processes running in networks of networks (such as the Internet) as distributed, reactive, agent-based, and concurrent computation. The transformation of information into knowledge, stored as associative memory and event-driven interaction history, allows us to not only understand how biological systems use knowledge but also to build a new class of digital automata with autopoietic and cognitive behaviors. Knowledge of structure, function, and causal behaviors are derived from information and its representation in the form of associative memory and event-driven interaction history enables self-organization and self-regulation in both biological systems and digital automata.

Author Contributions

Mikkilineni contributed to the application of GTI and conceptualization. Kelly’s contribution is in the implementation of the distributed software VoD application prototype to demonstrate the use of GTI.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author’s contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments). The author expresses his gratitude to the late Mark Burgin, who spent countless hours explaining the General Theory of Information and helped him understand its applications regarding software development.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barry M. Leiner, Vinton G. Cerf, David D. Clark, Robert E. Kahn, Leonard Kleinrock, Daniel C. Lynch, Jon Postel, Larry G. Roberts, Stephen Wolff. (1997) “A Brief History of the Internet.” https://www.internetsociety.org/internet/history-internet/brief-history-internet/ (Accessed on Nov.1, 2024).

- Erika Harrell, PhD, and Alexandra Thompson (2021) Victims of Identity Theft, 2021. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin. https://bjs.ojp.gov/document/vit21.pdf.

- Mohammed SA, Ralescu AL. Future Internet Architectures on an Emerging Scale—A Systematic Review. Future Internet. 2023; 15(5):166. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, A. G. (2023). A Next Generation Internet Architecture (Technical Report No. 978). University of Cambridge, Computer Laboratory. https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/techreports/UCAM-CL-TR-978.pdf.

- Yan, S., Bhandari, S. (2021). Future Applications and Requirements. In: Toy, M. (eds) Future Networks, Services and Management. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Cockshott, P.; MacKenzie, L.M.; Michaelson, G. Computation and Its Limits; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; p. 215.

- Aspray, W., & Burks, A. (1989). Papers of John von Neumann on Computing and Computer Theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- van Leeuwen, J., & Wiedermann, J. (2000). The Turing machine paradigm in contemporary computing. In B. Enquist, & W. Schmidt, Mathematics Unlimited—2001 and Beyond. LNCS. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. [CrossRef]

- Eberbach, E., & Wegner, P. (2003). Beyond Turing Machines. The Bulletin of the European Association for Theoretical Com-puter Science (EATCS Bulletin), 81(10), 279-304.

- Wegner, P., & Goldin, D. (2003). Computation beyond Turing Machines: Seeking appropriate methods to model computing and human thought. Communications of the ACM, 46(4), 100.

- Wegner, P., & Eberbach, E. (2004). New Models of Computation. The Computer Journal, 47(1), 4-9. [CrossRef]

- Dodig-Crnkovic, G. (2013). Alan Turing’s legacy: Info-computational philosophy of nature. Computing Nature: Turing Centenary Perspective, 115-123. [CrossRef]

- Cockshott, P., & Michaelson, G. (2007). Are There New Models of Computation? Reply to Wegner and Eberbach. Computer Journal, 5(2), 232-247. [CrossRef]

- Denning, P. (2011). What Have We Said About Computation? Closing Statement. http://ubiquity.acm.org/symposia.cfm. ACM.

- Dodig Crnkovic, G. Significance of Models of Computation, from Turing Model to Natural Computation. Minds Mach. 2011, 21, 301–322. [CrossRef]

- Burgin, M. Super-Recursive Algorithms; Springer: New York, NY, USA; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [CrossRef]

- “CAP Theorem (Explained)” Youtube, Uploaded by Techdose 9 December 2018. Available online: https://youtu.be/PyLMoN8kHwI?si=gtHWzvt2gelf3kly (accessed on 17 June 2024).

- M. Burgin and R. Mikkilineni, "General Theory of Information Paves the Way to a Secure, Service-Oriented Internet Connecting People, Things, and Businesses," 2022 12th International Congress on Advanced Applied Informatics (IIAI-AAI), Kanazawa, Japan, 2022, pp. 144-149. [CrossRef]

- Yanai, I.; Martin, L. The Society of Genes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016.

- František Dařena & Florian Gotter (2021) Technological Development and Its Effect on IT Operations Cost and Environmental Impact, International Journal of Sustainable Engineering, 14:3, 190-201. [CrossRef]

- M. Schwarzkopf, A. Konwinski, M. Abd-El-Malek, and J. Wilkes. Omega: flexible, scalable schedulers for large compute clusters. In Proceedings of the 8th ACM European Conference on Computer Systems, EuroSys ’13, pages 351–364, New York, NY, USA, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Mikkilineni R, Kelly WP, Crawley G. Digital Genome and Self-Regulating Distributed Software Applications with Associative Memory and Event-Driven History. Computers. 2024; 13(9):220. [CrossRef]

- Kephart, J.O.; Chess, D. The Vision of Autonomic Computing. Computer 2003, 36, 41–50. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L. Beyond the Brain; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011.

- O’Toole, J.; Gifford, D.K. Names should mean what, not where, in EW 5. In Proceedings of the 5th Workshop on ACM SIGOPS European Workshop: Models and Paradigms for Distributed Systems Structuring, Mont Saint-Michel, France, 1992, pp. 1–5.

- Balakrishnan, H.; Lakshminarayanan, K.; Ratnasamy, S.; Shenker, S.; Stoica, I.; Walfish, M. A Layered Naming Architecture for the Internet. ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review, 2004, 34, 343–352. [CrossRef]

- Mikkilineni R. A New Class of Autopoietic and Cognitive Machines. Information. 2022; 13(1):24. [CrossRef]

- Kelly WP, Coccaro F, Mikkilineni R. General Theory of Information, Digital Genome, Large Language Models, and Medical Knowledge-Driven Digital Assistant. Computer Sciences & Mathematics Forum. 2023; 8(1):70. [CrossRef]

- Burgin. M. (2010) Theory of Information, World Scientific Publishing, New York.

- Burgin, M. Theory of Knowledge: Structures and Processes; World Scientific: New York, NY, USA; London, UK; Singapore, 2016.

- Burgin, M. Structural Reality, Nova Science Publishers, New York, 2012.

- Burgin, M. (2011). Theory of named sets. Nova Science Publishers, N.Y.

- Mikkilineni R. Mark Burgin’s Legacy: The General Theory of Information, the Digital Genome, and the Future of Machine Intelligence. Philosophies. 2023; 8(6):107. [CrossRef]

- Mikkilineni R. Infusing Autopoietic and Cognitive Behaviors into Digital Automata to Improve Their Sentience, Resilience, and Intelligence. Big Data and Cognitive Computing. 2022; 6(1):7. [CrossRef]

- Digital Genome Implementation Presentations:—Autopoietic Machines (triadicautomata.com). Available online: https://triadicautomata.com/digital-genome-vod-presentation/ (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Cooper, S. B. (2013). What Makes A Computation Unconventional? In Computing Nature: Turing Centenary Perspective (pp. 255-269). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).