Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. UV-Visible Spectroscopy

2.3. ThT Spectrofluorometric Measurements

2.4. Circular Dichroism

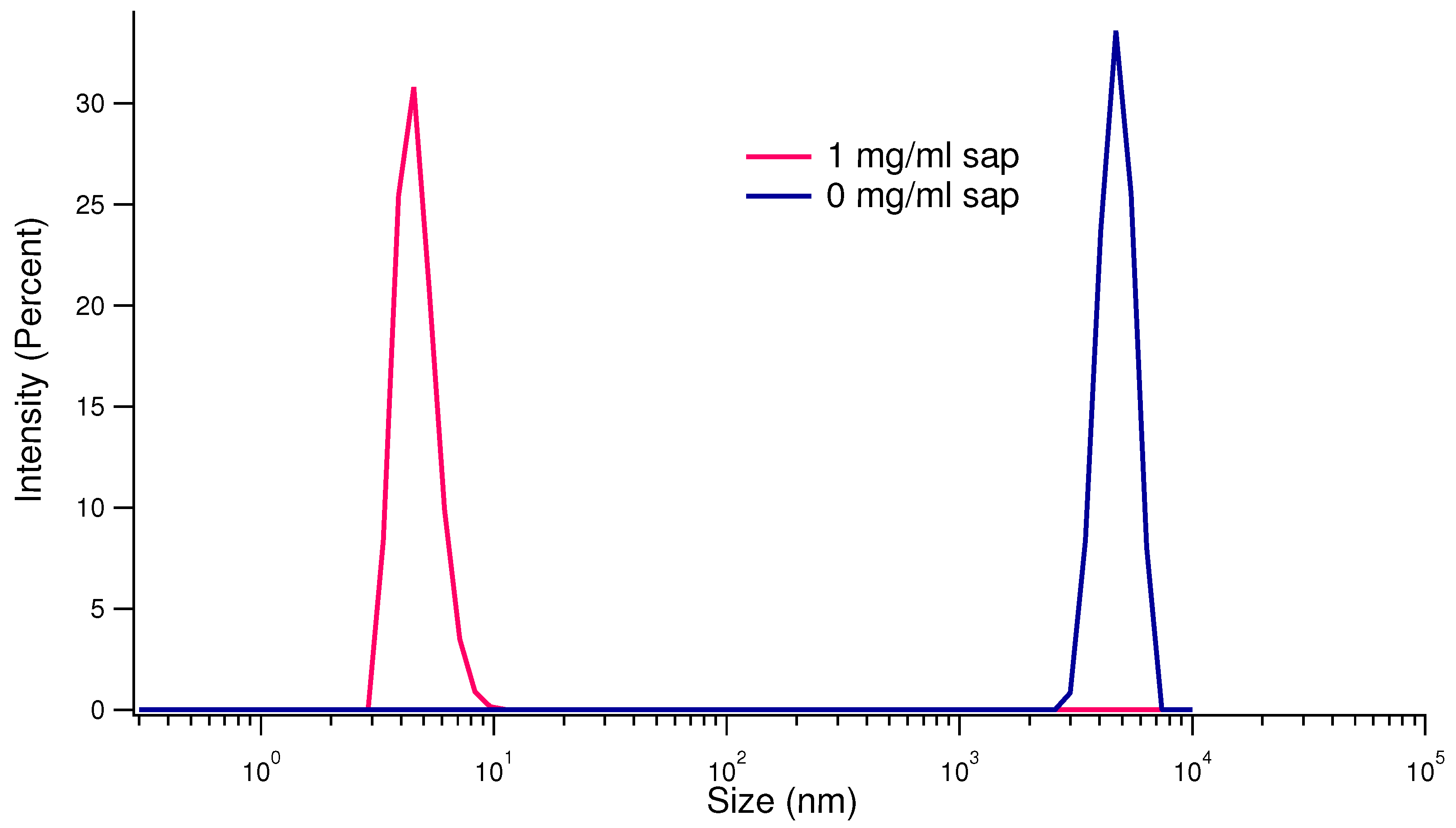

2.5. Dynamic Light Scattering

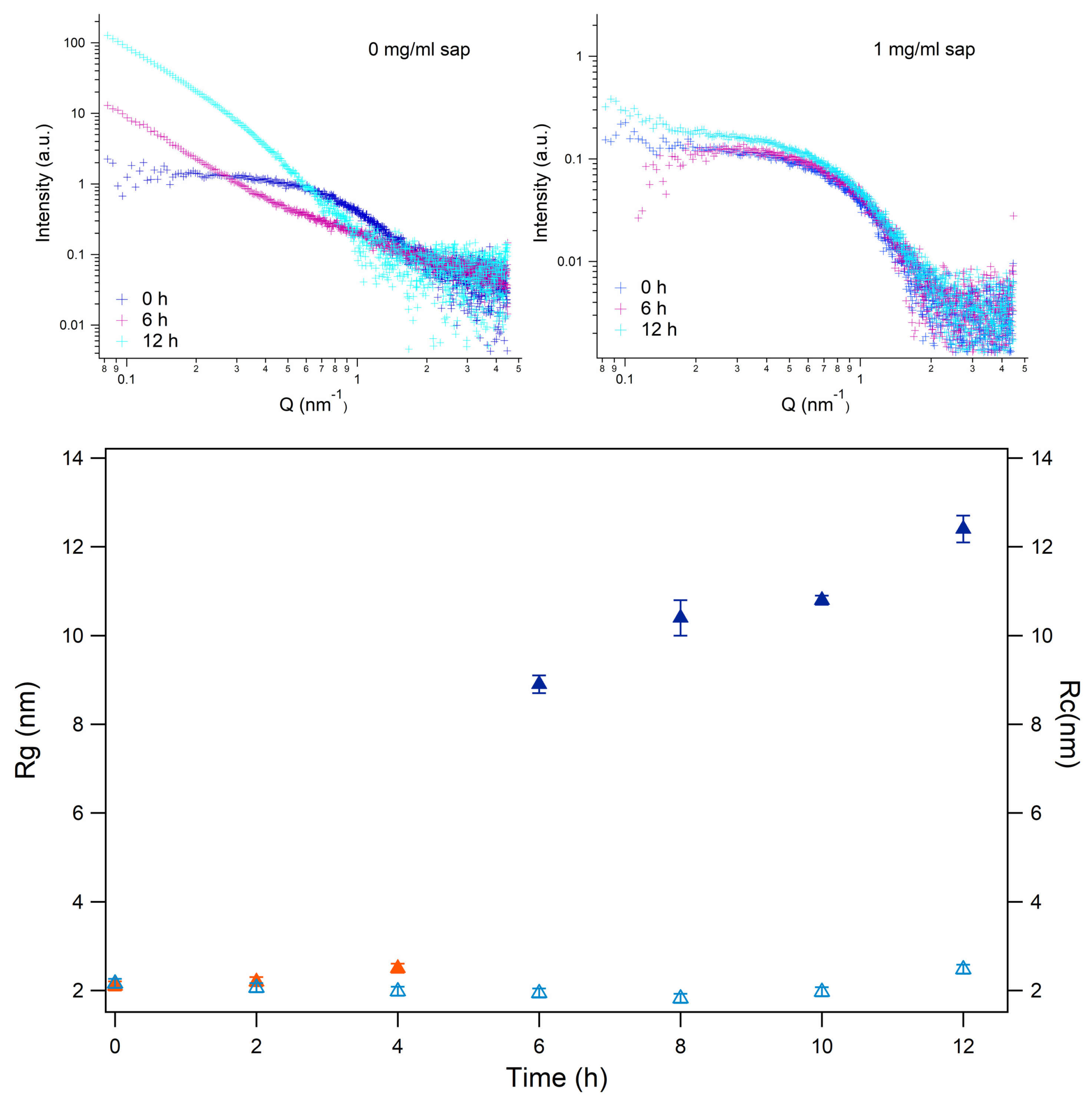

2.6. Small Angle X-Ray Scattering

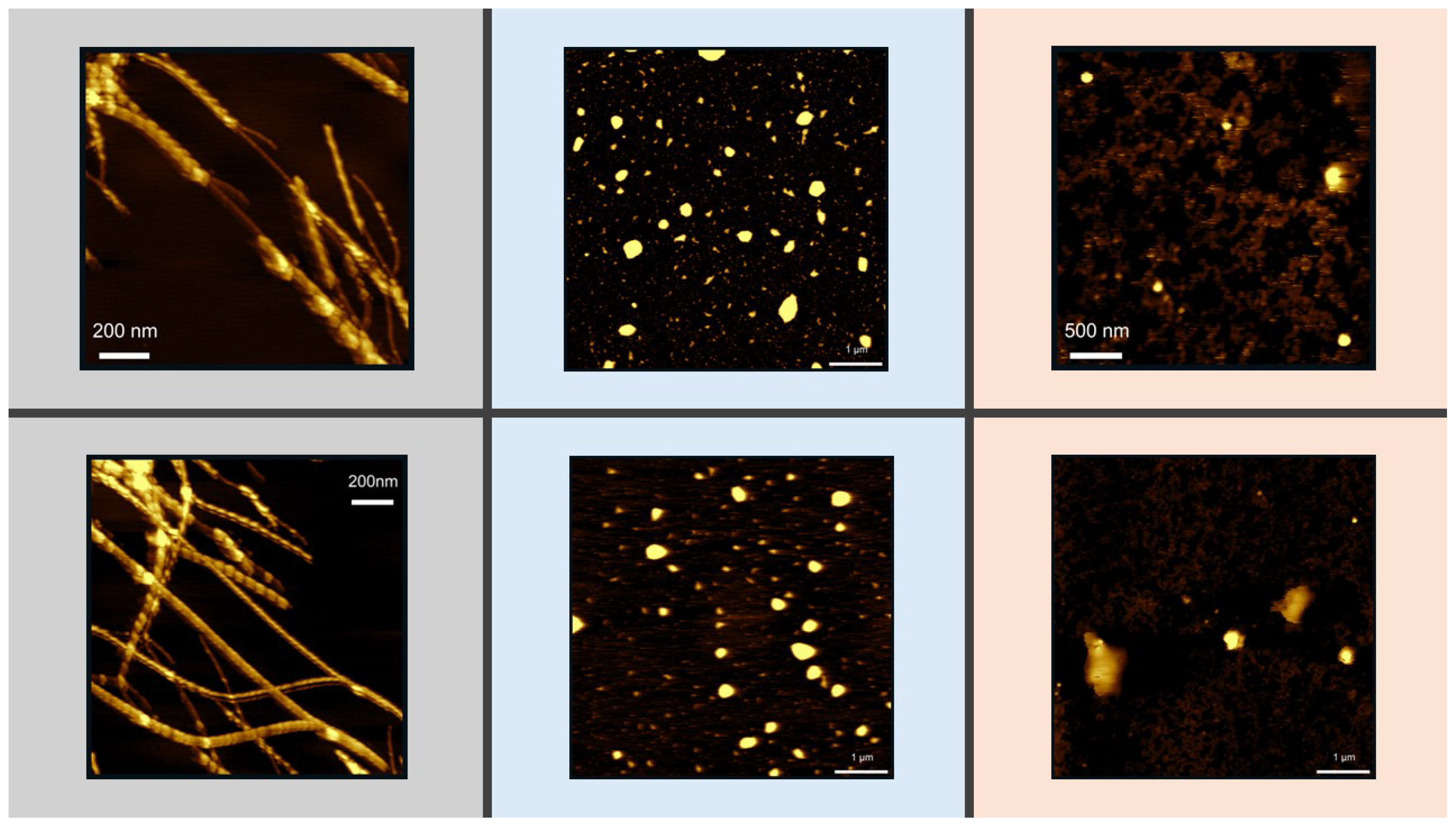

2.7. Atomic Force Microscopy

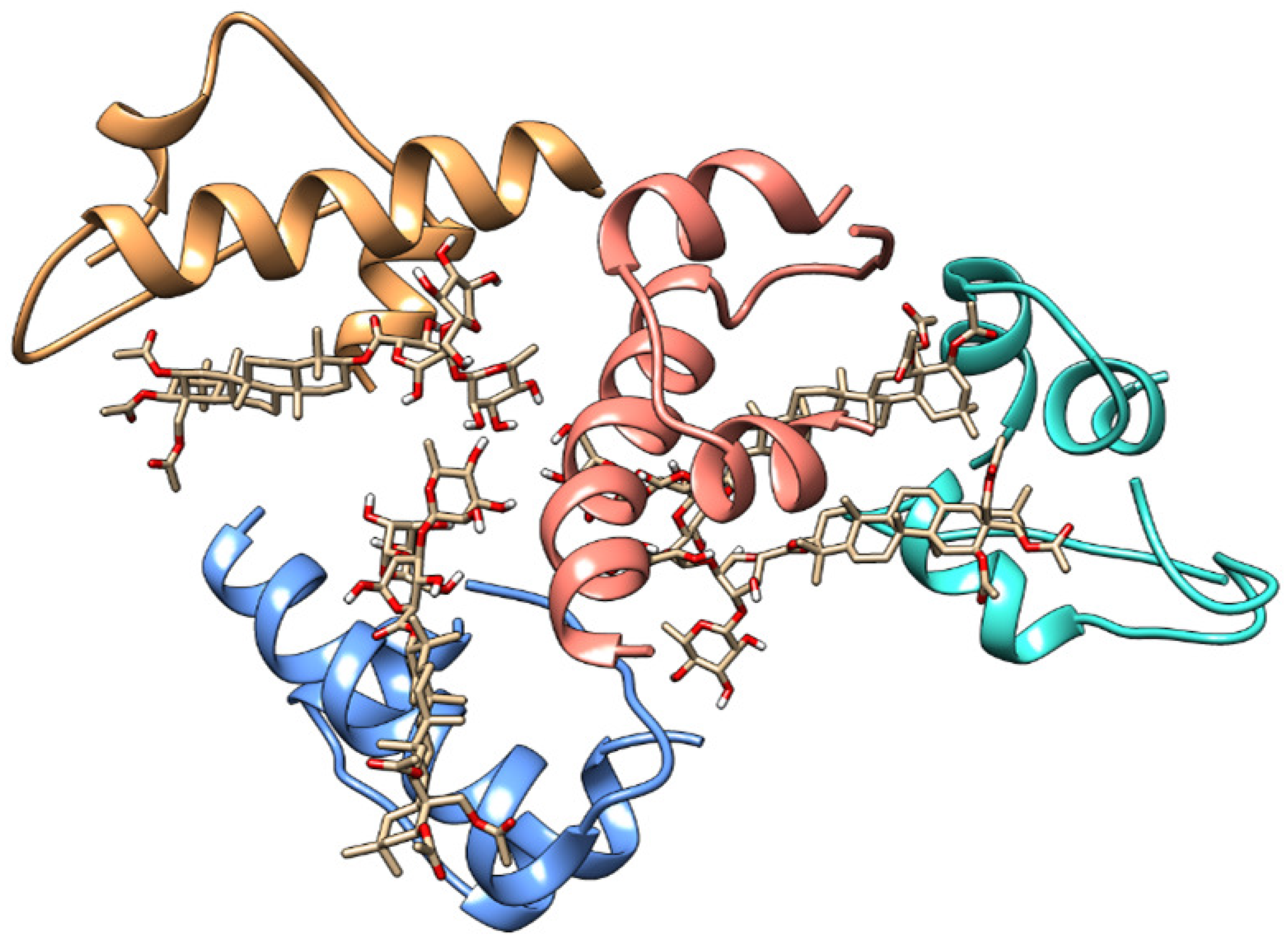

2.8. Molecular Dynamics

3. Results

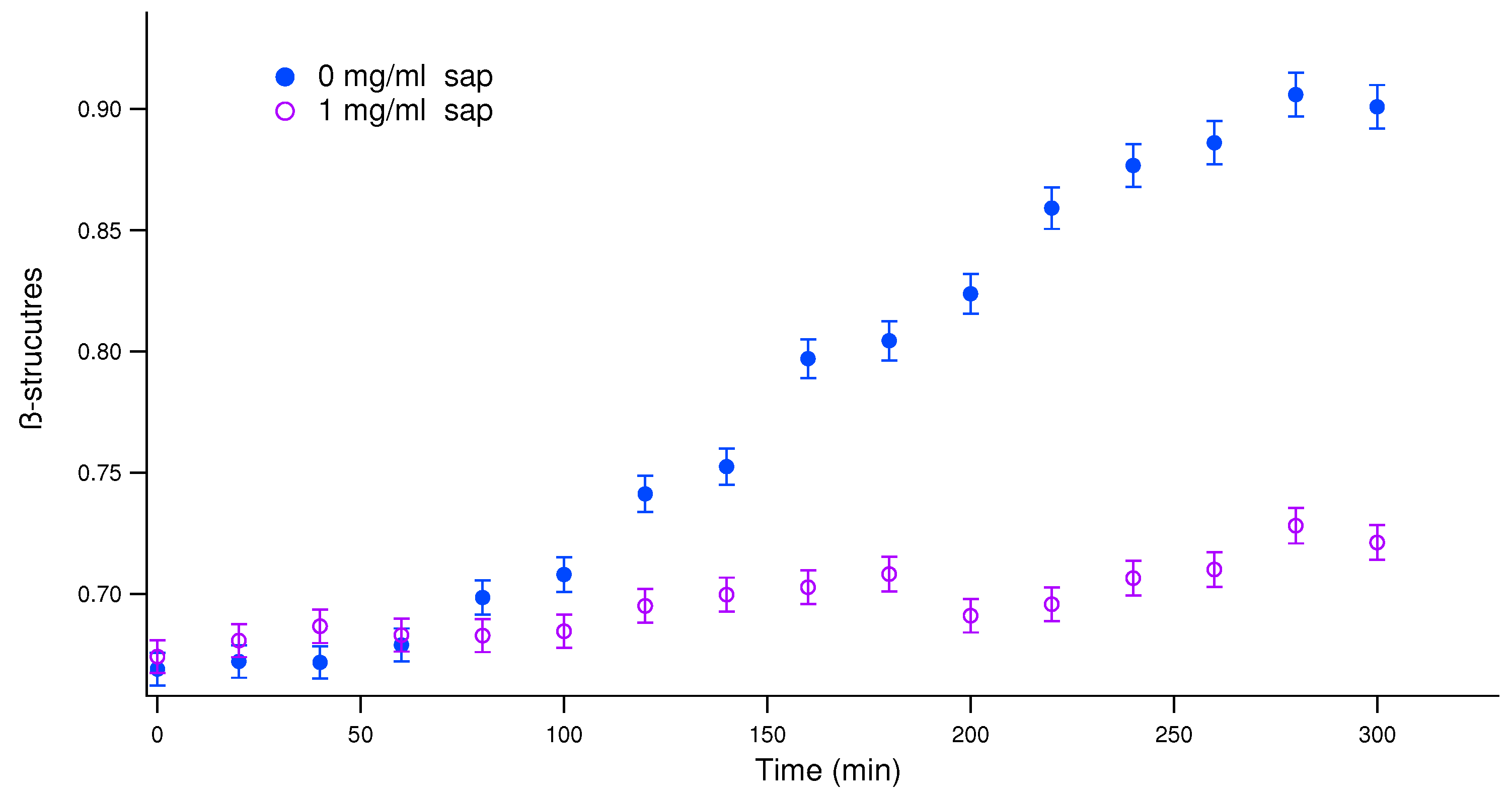

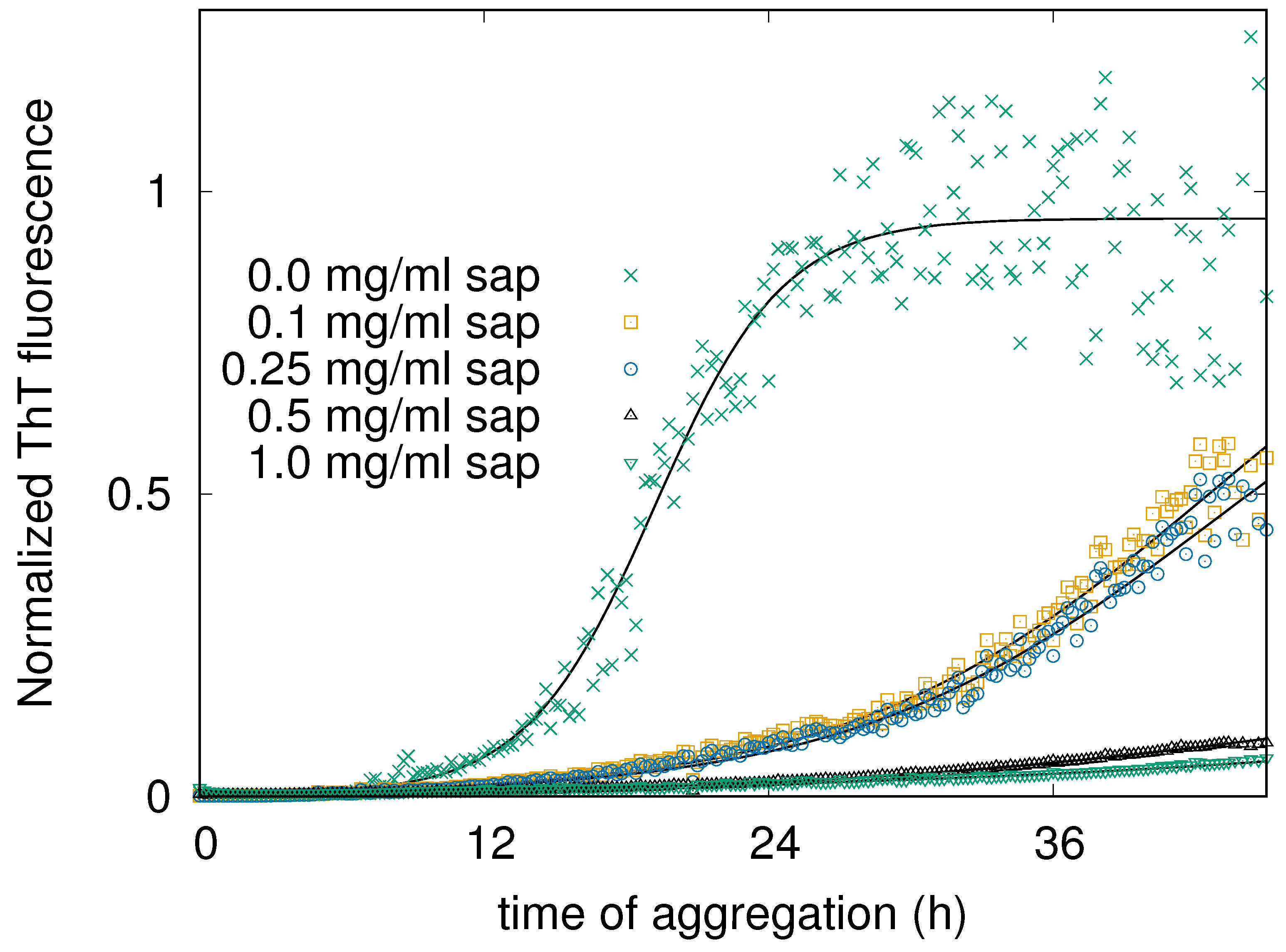

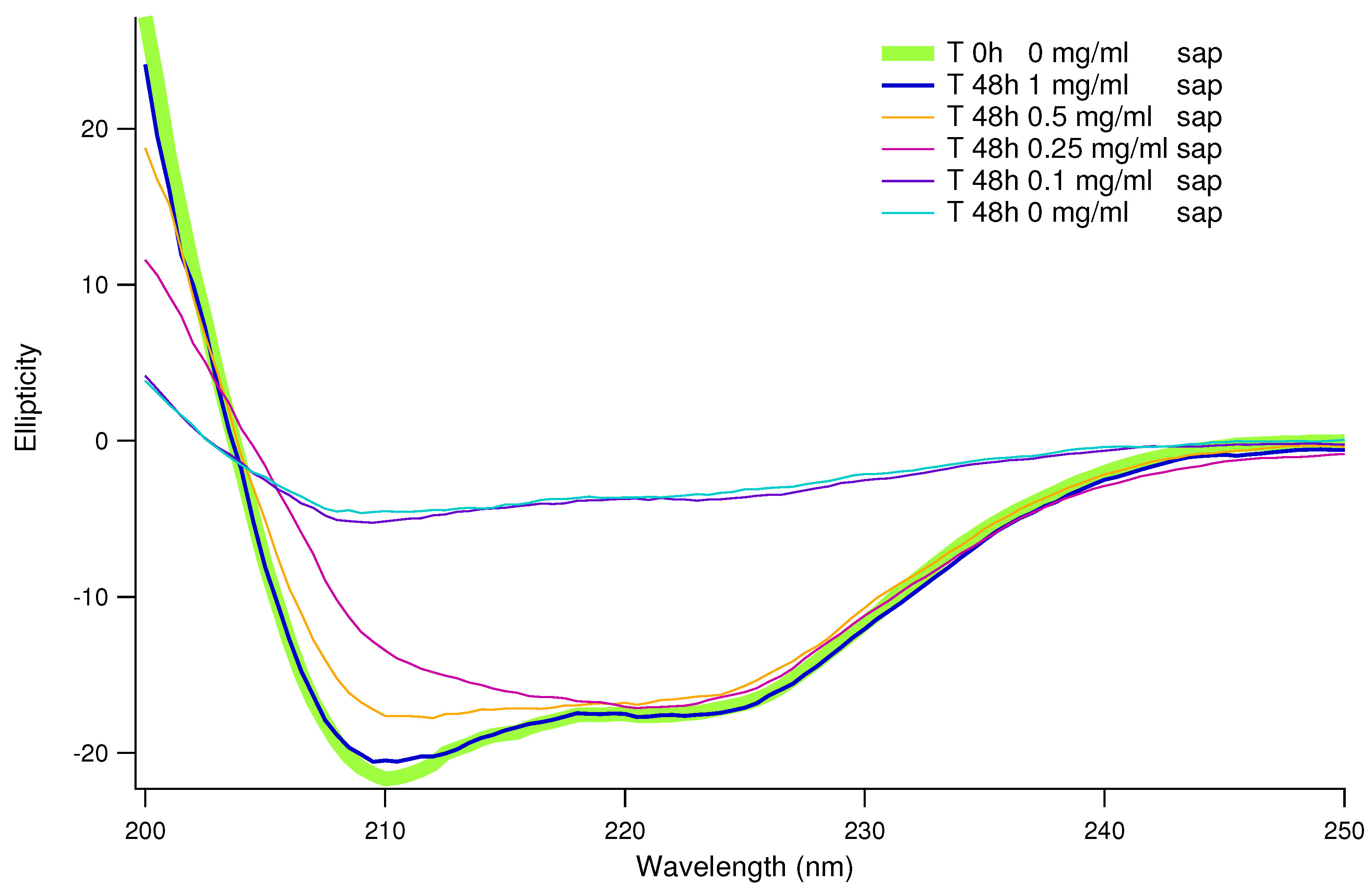

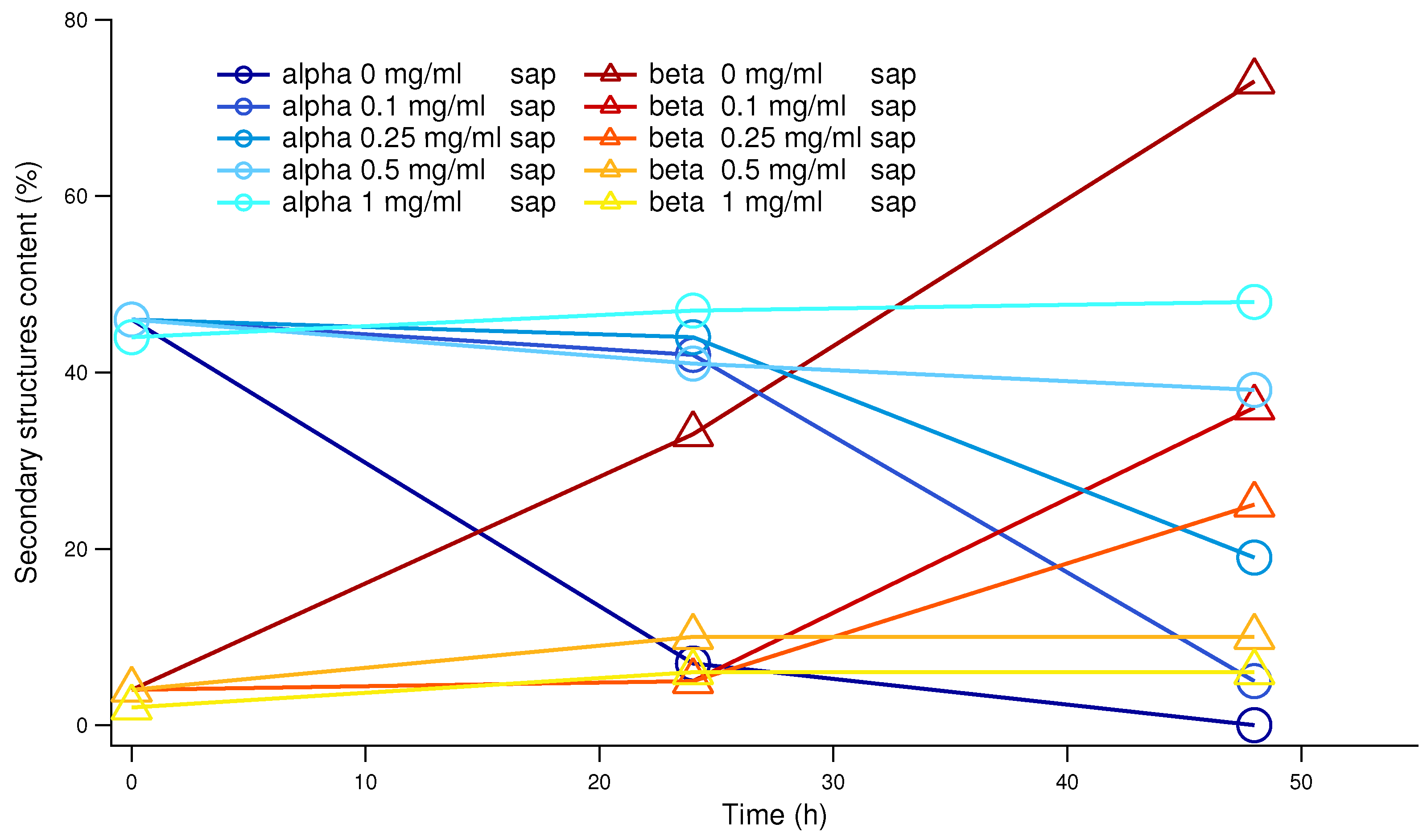

3.1. Secondary Structure

3.2. 3D Structure

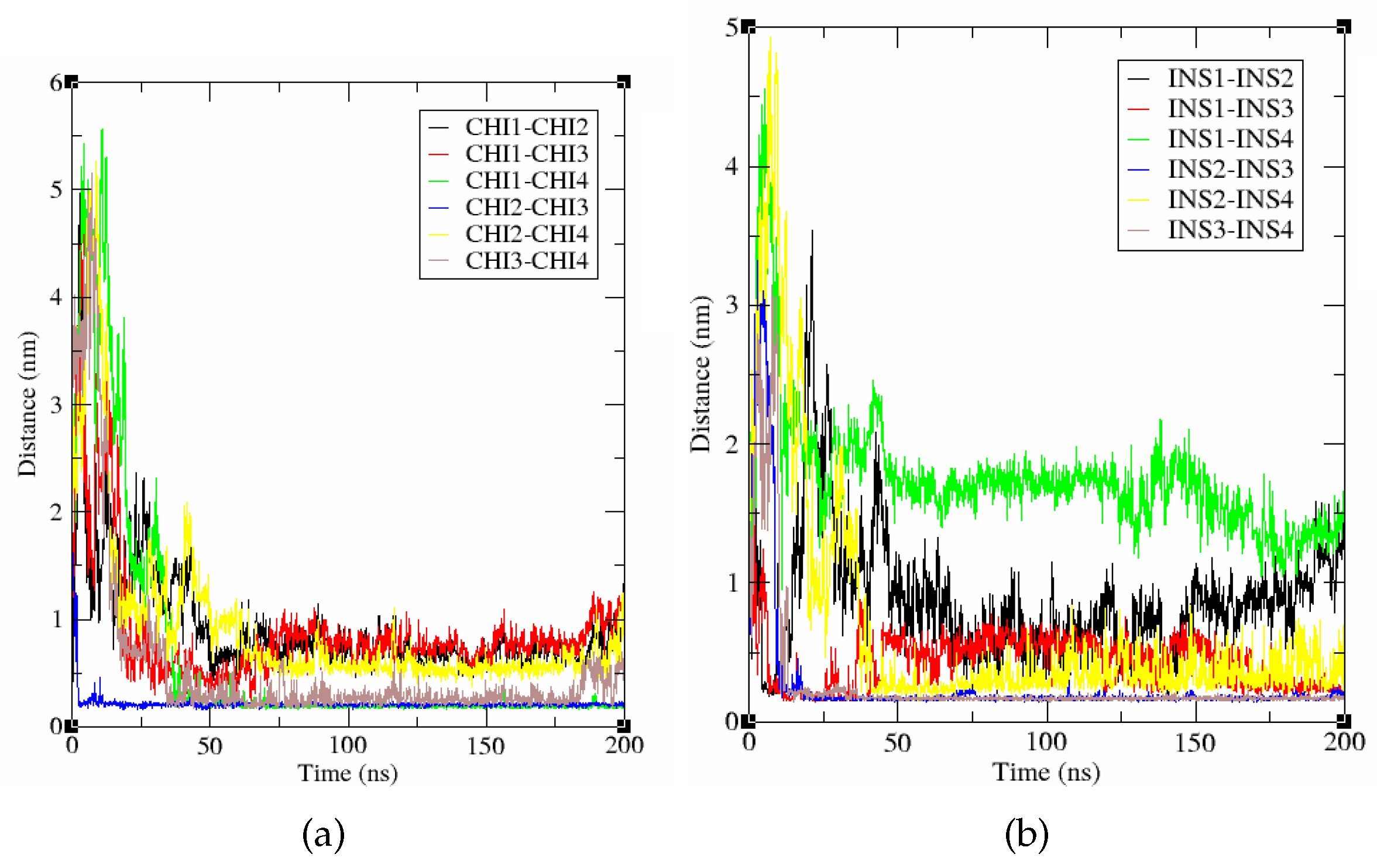

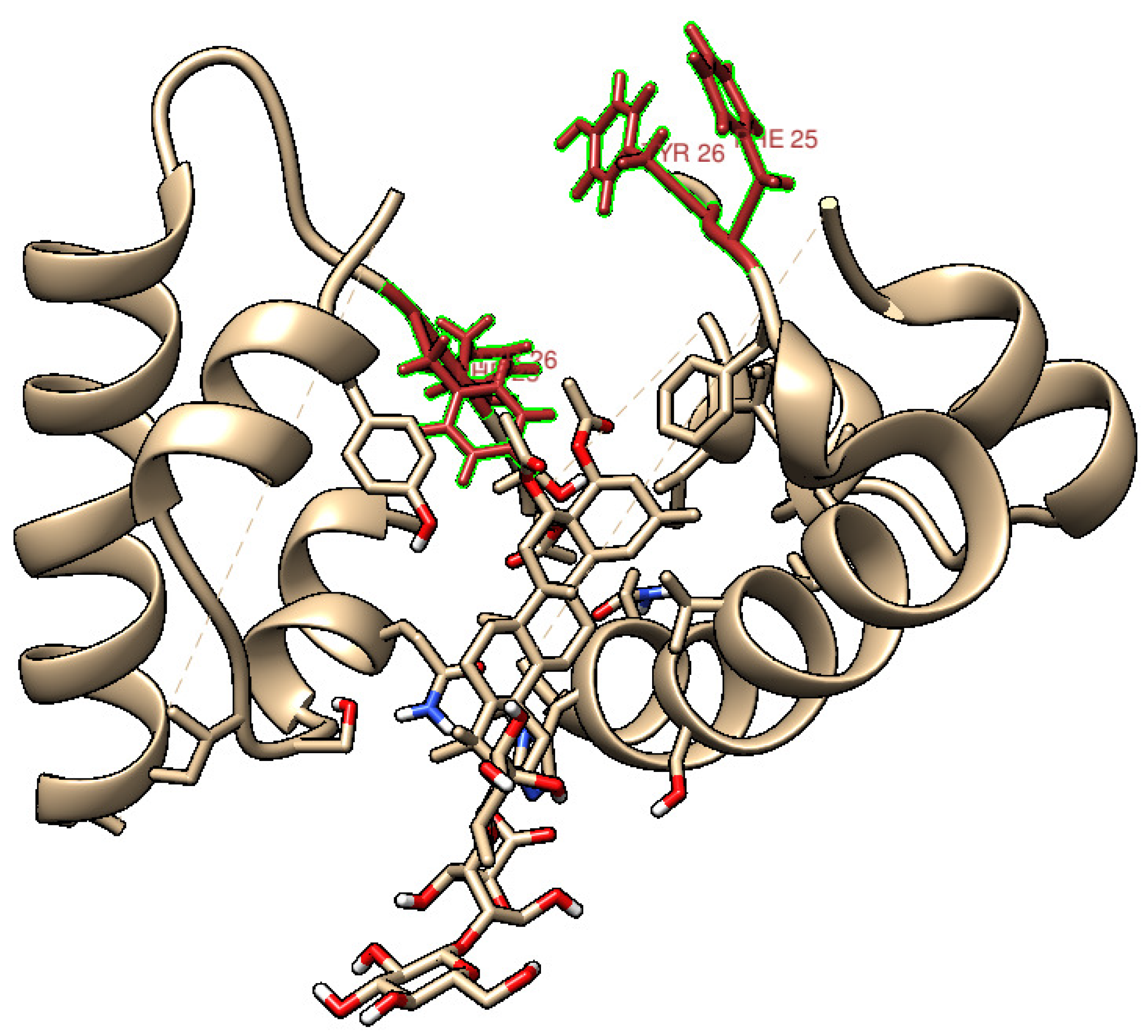

3.3. Molecular Findings

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| AD | Alzheimer Disease |

| AchEI | Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors |

| ThT | Thioflavin T |

| CR | Congo Red |

| CD | Circular dichroism |

| SAXS | Small Angle X-ray Scattering |

| DLS | Dynamic Light Scattering |

| AFM | Atomic Force Microscopy |

| MD | Molecular Dynamics |

| AIns | Insulin-derived amyloidosis |

References

- Weng, Y.; Yu, L.; Cui, J.; Zhu, Y.R.; Guo, C.; Wei, G.; Duan, J.L.; Yin, Y.; Guan, Y.; Wang, Y.H.; et al. Antihyperglycemic, hypolipidemic and antioxidant activities of total saponins extracted from Aralia taibaiensis in experimental type 2 diabetic rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2014, 152, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Jiang, L.; Gao, B.; Chai, Y.; Bao, Y. Comprehensive in silico analysis of the probiotics, and preparation of compound probiotics-Polygonatum sibiricum saponin with hypoglycemic properties. Food Chemistry 2023, 404, 134569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, K.; Ruan, L.; Hu, J.; Fu, Z.; Tian, D.; Zou, W. Panax notoginseng saponin R1 modulates TNF-α/NF-κB signaling and attenuates allergic airway inflammation in asthma. International Immunopharmacology 2020, 88, 106860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.I.; Karima, G.; Khan, M.Z.; Shin, J.H.; Kim, J.D. Therapeutic Effects of Saponins for the Prevention and Treatment of Cancer by Ameliorating Inflammation and Angiogenesis and Inducing Antioxidant and Apoptotic Effects in Human Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarrola, D.; Arrua, W.; Gonzalez, J.; Soverina Escobar, M.; Centurión, J.; Campuzano Benitez, A.; Ovando Soria, F.; Rodas González, E.; Arrúa, K.; Acevedo Barrios, M.; et al. The antihypertensive and diuretic effect of crude root extract and saponins from Solanum sisymbriifolium Lam., in L-NAME-induced hypertension in rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2022, 298, 115605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Monje-Galvan, V. In Vitro and In Silico Studies of Antimicrobial Saponins: A Review. Processes 2023, 11, 2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Kaur, R.; Kumar, S.; Saini, R.K.; Sharma, S.; Pawde, S.V.; Kumar, V. Saponins: A concise review on food related aspects, applications and health implications. Food Chemistry Advances 2023, 2, 100191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, W.K.; Roshdy, H.M.; Kassem, S.M. The potential therapeutic role of Fenugreek saponin against Alzheimer’s disease: Evaluation of apoptotic and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activities. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science 2016, 6, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abduljawad, A.A.; Elawad, M.A.; Elkhalifa, M.E.M.; Ahmed, A.; Hamdoon, A.A.E.; Salim, L.H.M.; Ashraf, M.; Ayaz, M.; Hassan, S.S.u.; Bungau, S. Alzheimer’s Disease as a Major Public Health Concern: Role of Dietary Saponins in Mitigating Neurodegenerative Disorders and Their Underlying Mechanisms. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zeng, M.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Lv, N.; Wang, L.; Gan, J.; Li, Y.; Jiang, X.; Yang, L. Therapeutic Candidates for Alzheimer’s Disease: Saponins. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihara, K.; Koike, S.; Ogasawara, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Koyama, K.; Kinoshita, K. Inhibition of amyloid β aggregation and protective effect on SH-SY5Y cells by triterpenoid saponins from the cactus Polaskia chichipe. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2017, 25, 3377–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihara, K.; Shimoyama, T.; Kawazu, R.; Sasaki, H.; Koyama, K.; Takahashi, K.; Kinoshita, K. Amyloid β aggregation inhibitory activity of triterpene saponins from the cactus Stenocereus pruinosus. Journal of Natural Medicine 2021, 75, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brange, J.; Andersen, L.; Laursen, E.D.; Meyn, G.; Rasmussen, E. Toward Understanding Insulin Fibrillation. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 1997, 86, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manno, M.; Craparo, E.F.; Martorana, V.; Bulone, D.; Biagio, P.L.S. Kinetics of Insulin Aggregation: Disentanglement of Amyloid Fibrillation from Large-Size Cluster Formation. Biophysical Journal 2006, 0, 4585–4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagihi, M.H.A.; Bhattacharjee, S. Amyloid Fibrillation of Insulin: Amelioration Strategies and Implications for Translation. ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science 2022, 5, 1050–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foderà, V.; Librizzi, F.; Groenning, M.; van de Weert, M.; Leone, M. Secondary Nucleation and Accessible Surface in Insulin Amyloid Fibril Formation. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2008, 112, 3853–3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannuzzi, C.; Borriello, M.; Portaccio, M.; Irace, G.; Sirangelo, I. Insights into Insulin Fibril Assembly at Physiological and Acidic pH and Related Amyloid Intrinsic Fluorescence. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaunys, M.; Mikalauskaite, K.; Sakalauskas, A.; Smirnovas, V. Study of Insulin Aggregation and Fibril Structure under Different Environmental Conditions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, L.; Khurana, R.; Coats, A.; Frokjaer, S.; Brange, J.; Vyas, S.; Uversky, V.N.; Fink, A.L. Effect of Environmental Factors on the Kinetics of Insulin Fibril Formation: Elucidation of the Molecular Mechanism. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 6036–6046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilhelm, K.R.; Yanamandra, K.; Gruden, M.A.; Zamotin, V.; Malisauskas, M.; Casaite, V.; Darinskas, A.; Forsgren, L.; Morozova-Roche, L.A. Immune reactivity towards insulin, its amyloid and protein S100B in blood sera of Parkinson’s disease patients. European Journal of Neurology 2007, 14, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzo, F.; Mangione, M.; Librizzi, F.; Manno, M.; Martorana, V.; Noto, R.; Vilasi, S. The Possible Role of the Type I Chaperonins in Human Insulin Self-Association. Life (Basel) 2022, 12, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshihara, H.; Saito, J.; Tanabe, A.; Amada, T.; Asakura, T.; Kitagawa, K.S. Characterization of Novel Insulin Fibrils That Show Strong Cytotoxicity Under Physiological pH. J Pharm Sci. 2016, 105, 1419–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, M.R. Insulin amyloid at injection sites of patients with diabetes. Amyloid Int. J. Exp. Clin. Investig. 2016, 23, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suladze, S.; Sarkar, R.; Rodina, N.; Bokvist, K.; Krewinkel, M.; Scheps, D.; Nagel, N.; Bardiaux, B.; Reif, B. Atomic resolution structure of full-length human insulin fibrils. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2024, 121, e2401458121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilasi, S.; Iannuzzi, C.; Portaccio, M.; Irace, G.; Sirangelo, I. Effect of Trehalose on W7FW14F Apomyoglobin and Insulin Fibrillization: New Insight into Inhibition Activity. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 1789–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, E.; Ricci, C.; Pieraccini, S.; Spinozzi, F.; Mariani, P.; Ortore, M.G. Trehalose Effect on The Aggregation of Model Proteins into Amyloid Fibrils. Life 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micsonai, A.; Moussong, E.; Wien, F.; Boros, E.; Vadászi, H.; Murvai, N.; Lee, Y.H.; Molnár, T.; Réfrégiers, M.; Goto, Y.; et al. BeStSel: webserver for secondary structure and fold prediction for protein CD spectroscopy. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50(1), 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provencher, S.W. A constrained regularization method for inverting data represented by linear algebraic or integral equations. Computer Physics Communications 1982, 27, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenitsch, H.; Rappolt, M.; Kriechbaum, M.; Mio, H.; Laggner, P.; Bernstorff, S. First performance assessment of the small-angle X-ray scattering beamline at ELETTRA. Journal of Synchrotron Radiation 1998, 5, 506–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, R.; Sartori, B.; Radeticchio, A.; Wolf, M.; Dal Zilio, S.; Marmiroli, B.; Amenitsch, H. μDrop: a system for high-throughput small-angle X-ray scattering measurements of microlitre samples. Journal of Applied Crystallography 2021, 54, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nečas, D.; Klapetek, P. Gwyddion: an open-source software for SPM data analysis. Central European Journal of Physics 2012, 10, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.D.; Ciszak, E.; Magrum, L.A.; Pangborn, W.A.; Blessing, R.H. R6 hexameric insulin complexed with m-cresol or resorcinol. Acta Crystallographica Section D 2000, 56, 1541–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, D.; Shenkin, P.S.; Hollinger, F.P.; Still, W.C. The GB/SA Continuum Model for Solvation. A Fast Analytical Method for the Calculation of Approximate Born Radii. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 1997, 101, 3005–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Gaussian˜16 Revision, C.; et al. Gaussian˜16 Revision C.01, 2016. Gaussian Inc. Wallingford CT.

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nose, S. A unified formulation of the constant temperature molecular dynamics methods. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1984, 81, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrella, L.; Moretti, P.; Pieraccini, S.; Magi, S.; Piccirillo, S.; Ortore, M.G. Taurine Stabilizing Effect on Lysozyme. Life 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, T.P.J.; White, D.A.; Abate, A.R.; Agresti, J.J.; Cohen, S.I.A.; Sperling, R.A.; De Genst, E.J.; Dobson, C.M.; Weitz, D.A. Observation of spatial propagation of amyloid assembly from single nuclei. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 14746–14751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrelli, A.; Moretti, P.; Gerelli, Y.; Ortore, M.G. Effects of model membranes on lysozyme amyloid aggregation. Biomolecular Concepts 2023, 14, 20220034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernson, D.; Mecinovic, A.; Abed, M.; Lime, F.; Jageland, P.; Palmlof, M.; Esbjorner, E. Amyloid formation of bovine insulin is retarded in moderately acidic pH and by addition of short-chain alcohols. Eur. Biophys. J. 2020, 49, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, M.; Martins, A.S.; Catarino, J.; Faísca, P.; Kumar, P.; Pinto, J.F.; Pinto, R.; Correia, I.; Ascensão, L.; Afonso, R.A.; et al. How Can Biomolecules Improve Mucoadhesion of Oral Insulin? A Comprehensive Insight using Ex-Vivo, In Silico, and In Vivo Models. Biomolecules 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karen E Marshall, Ricardo Marchante, W.F.X.; Serpell, L.C. The relationship between amyloid structure and cytotoxicity. Prion 2014, 8, 192–196. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Z.; Geng, X.; Wei, L.; Li, Z.; Lin, S.; Xiao, L. Length-Dependent Distinct Cytotoxic Effect of Amyloid Fibrils beyond Optical Diffraction Limit Revealed by Nanoscopic Imaging. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortore, M.G.; Spinozzi, F.; Vilasi, S.; Sirangelo, I.; Irace, G.; Shukla, A.; Narayanan, T.; Sinibaldi, R.; Mariani, P. Time-resolved small-angle x-ray scattering study of the early stage of amyloid formation of an apomyoglobin mutant. Physical Review E 2011, 84, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langkilde, A.E.; Vestergaard, B. Methods for structural characterization of prefibrillar intermediates and amyloid fibrils. FEBS Letters 2009, 583, 2600–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, C.; Barone, G.; Bulone, D.; Burgio, G.; Carrotta, R.; Librizzi, F.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Rosalia Mangione, M.; Palumbo Piccionello, A.; San Biagio, P.L.; et al. Structure and Stability of Hsp60 and Groel in Solution. Biophysical Journal 2016, 110, 368a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herranz-Trillo, F.; Groenning, M.; van Maarschalkerweerd, A.; Tauler, R.; Vestergaard, B.; Bernadó, P. Structural Analysis of Multi-component Amyloid Systems by Chemometric SAXS Data Decomposition. Structure 2017, 25, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Zhao, H.; Qi, W.; He, M. The Hydration Shell of Monomeric and Dimeric Insulin Studied by Terahertz Time-Domain Spectroscopy. Biophysical Journal 2019, 117, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, M.; Craparo, E.F.; Podestà, A.; Bulone, D.; Carrotta, R.; Martorana, V.; Tiana, G.; San Biagio, P.L. Kinetics of Different Processes in Human Insulin Amyloid Formation. Journal of Molecular Biology 2007, 366, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamcik, J.; Mezzenga, R. Study of amyloid fibrils via atomic force microscopy. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science 2012, 17, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Dungan, S.R. Micellar Properties of Quillaja Saponin. 1. Effects of Temperature, Salt, and pH on Solution Properties. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 1997, 45, 1587–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmond, J.; Koner, D.; Meuwly, M. Probing the Differential Dynamics of the Monomeric and Dimeric Insulin from Amide-I IR Spectroscopy. J Phys Chem B. 2019, 123, 6588–6598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karkhaneh, L.; Hosseinkhani, S.; Azami, H.; Karamlou, Y.; Sheidaei, A.; Nasli-Esfahani, E.; Razi, F.; Ebrahim-Habibi, A. Comprehensive investigation of insulin-induced amyloidosis lesions in patients with diabetes at clinical and histological levels: A systematic review. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 2024, 18, 103083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Mondal, S.; Bagchi, B. Insulin dimer dissociation in aqueous solution: A computational study of free energy landscape and evolving microscopic structure along the reaction pathway. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2018, 149, 114902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Saponins concentration (mg/ml | 0 | 0.1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halftime (h) | 19.2 ± 0.1 | 42.6 ± 0.7 | 42.6 ± 0.7 | 52 ± 1 | 110 ± 80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).