Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Overexpression of TCP5 Resulted in Male Sterility

2.2. TCP5 Overexpression Reduced Lignin Accumulation in the Anther Endothecium

2.3. TCP5 Overexpression Resulted in Fewer Pollen Sacs and Pollen

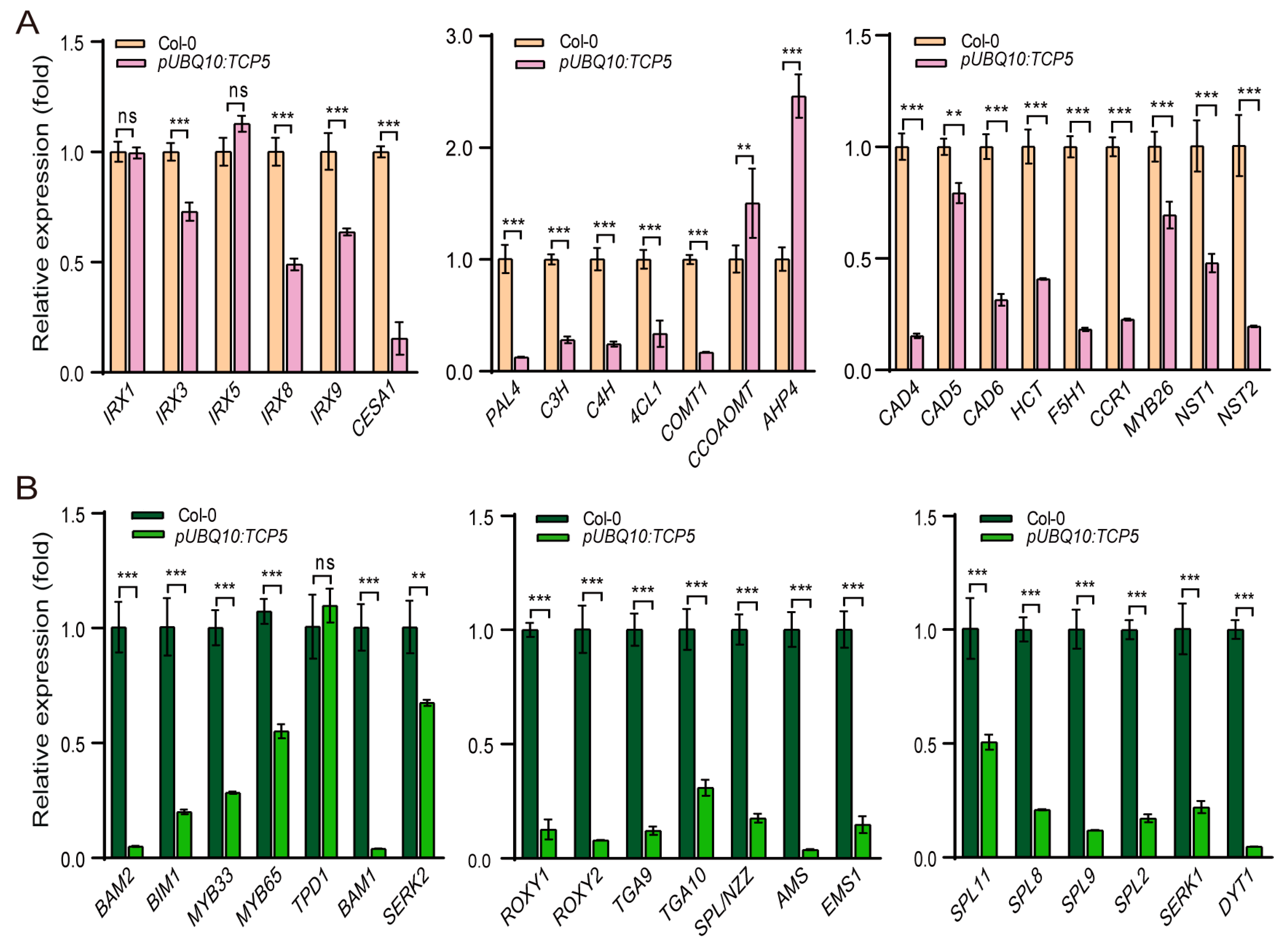

2.4. TCP5 Overexpression Affected the Expressions of Genes Involved in Secondary Cell Wall Formation and Other Key Anther Genes

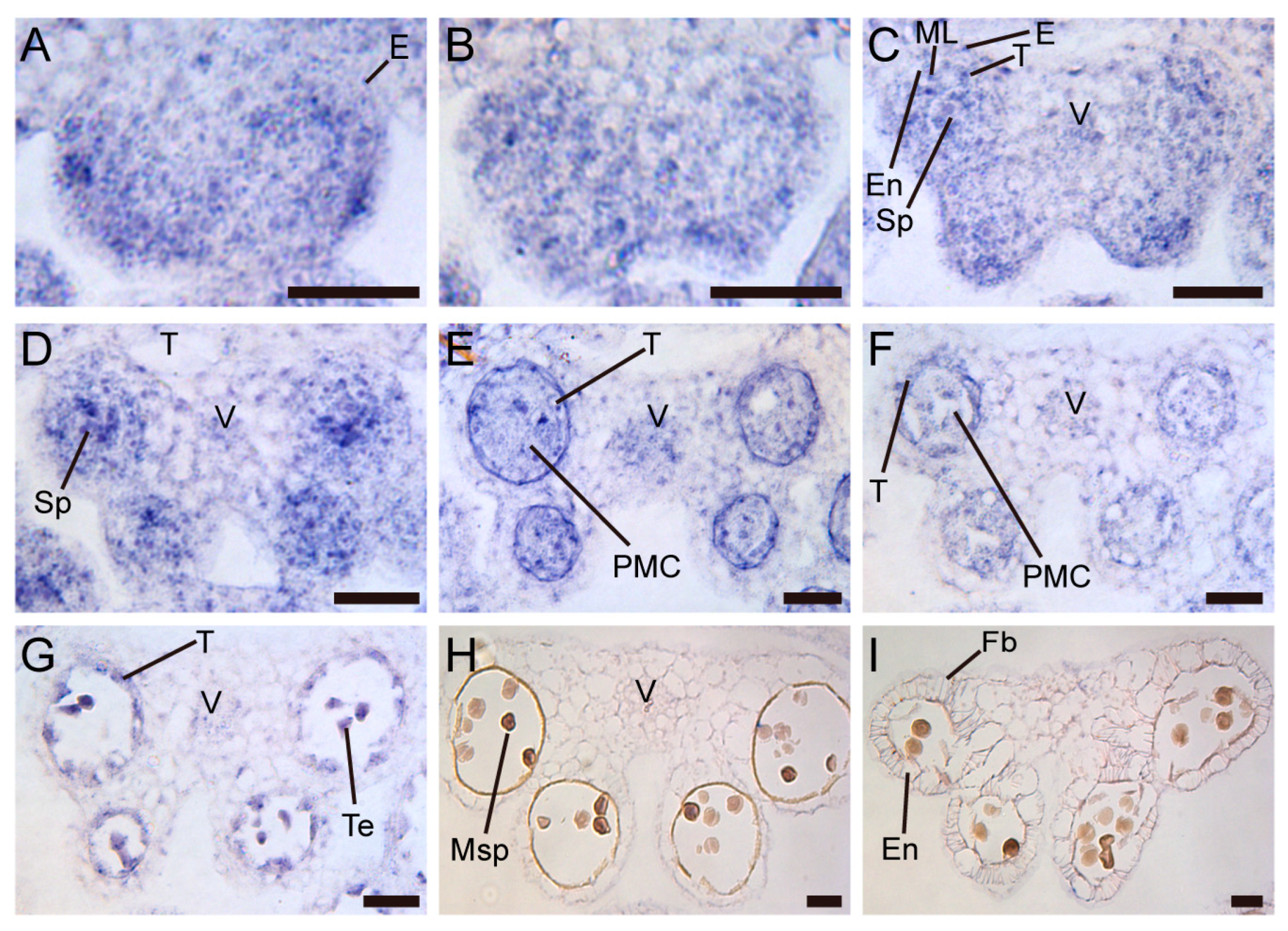

2.5. TCP5 Was Expressed in the Early Anthers

2.6. TCP5-SRDX Transgenic Plants also Had Male Fertility Defects

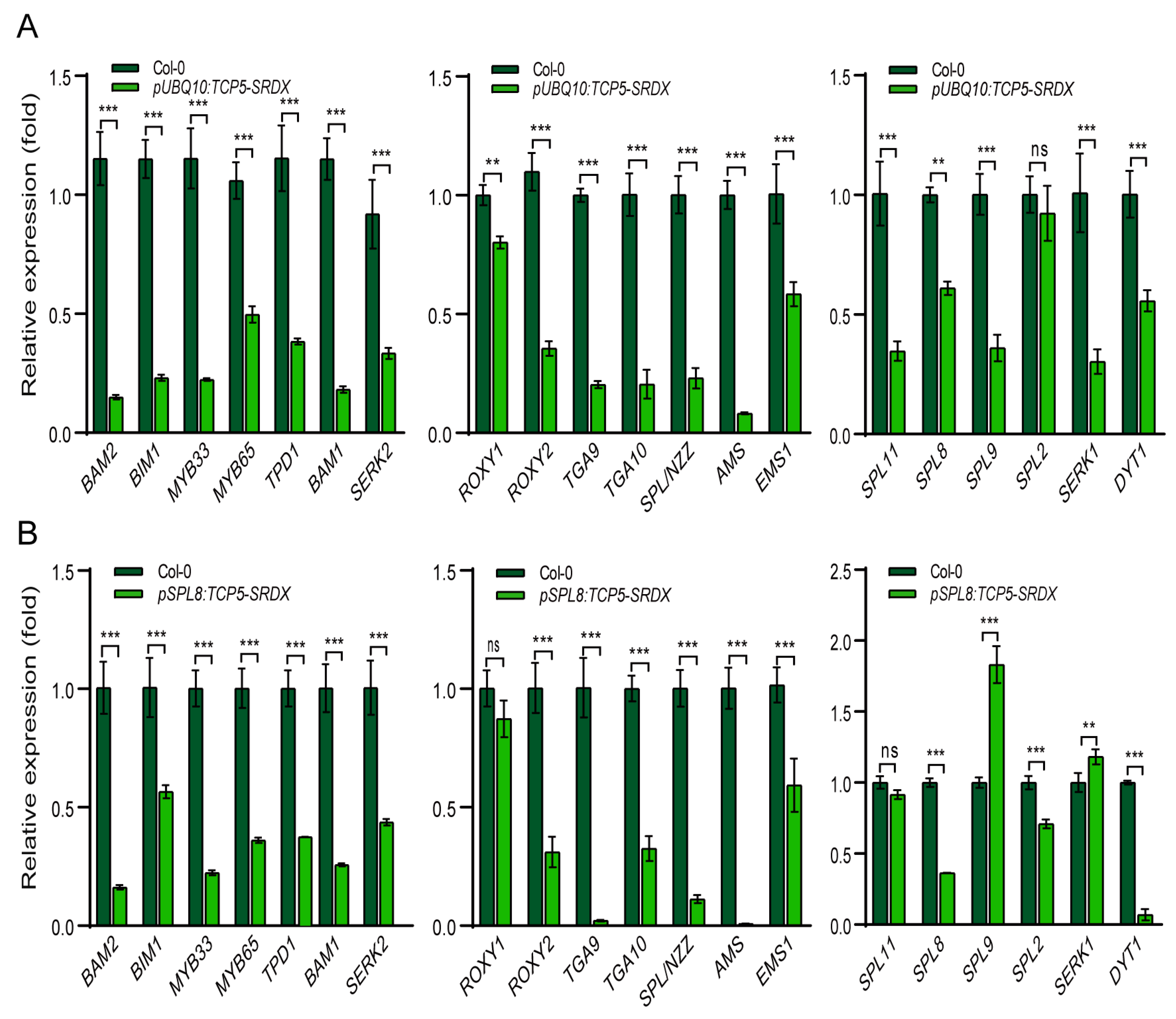

2.7. TCP5-SRDX Transgenic Plants Exhibited Altered Expression of Early Anther Genes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

4.2. Plasmid Construction and Transgenic Plants

4.3. Histology, Histochemistry, and Microscopy

4.4. In Situ Hybridization

4.5. RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR Analysis

4.6. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- González-Grandío, E.; Cubas, P. TCP Transcription Factors: Evolution, Structure, and Biochemical Function. Plant Transcription Factors. 2016; pp 139-151.

- Cubas, P.; Lauter, N.; Doebley, J.; Coen, E. The TCP domain: a motif found in proteins regulating plant growth and development. Plant J. 1999, 18(2), 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manassero, N. G. U.; Viola, I. L.; Welchen, E.; Gonzalez, D. H. TCP transcription factors: architectures of plant form. Biomolecular concepts. 2013, 4(2), 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viola, I. L.; Gonzalez, D. H. TCP Transcription Factors in Plant Reproductive Development: Juggling Multiple Roles. Biomolecules. 2023, 13(5), 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Lu, W.; Li, J.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y. Roles of miR319-regulated TCPs in plant development and response to abiotic stress. The Crop Journal. 2021, 9(1), 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schommer, C.; Debernardi, J. M.; Bresso, E. G.; Rodriguez, R. E.; Palatnik, J. F. Repression of cell proliferation by miR319-regulated TCP4. Mol Plant. 2014, 7(10), 1533–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Irish, V. F. Temporal Control of Plant Organ Growth by TCP Transcription Factors. Curr Biol. 2015, 25(13), 1765–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cochet, F.; Ponnaiah, M.; Lebreton, S.; Matheron, L.; Pionneau, C.; Boudsocq, M.; Resentini, F.; Huguet, S.; Blazquez, M. A.; Bailly, C.; Puyaubert, J.; Baudouin, E. The MPK8-TCP14 pathway promotes seed germination in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2019, 100(4), 677–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Lantzouni, O.; Bruggink, T.; Benjamins, R.; Lanfermeijer, F.; Denby, K.; Schwechheimer, C.; Bassel, G. W. A Molecular Signal Integration Network Underpinning Arabidopsis Seed Germination. Curr Biol. 2020, 30(19), 3703–3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatematsu, K.; Nakabayashi, K.; Kamiya, Y.; Nambara, E. Transcription factor AtTCP14 regulates embryonic growth potential during seed germination in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2008, 53(1), 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhao, X.; Kong, F.; Zuo, Z.; Liu, X. TCP2 positively regulates HY5/HYH and photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2016, 67(3), 775–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xun, Q.; Zhang, D.; Lv, M.; Ou, Y.; Li, J. TCP Transcription Factors Associate with PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR 4 and CRYPTOCHROME 1 to Regulate Thermomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. iScience. 2019, 15, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Challa, K. R.; Aggarwal, P.; Nath, U. Activation of YUCCA5 by the Transcription Factor TCP4 Integrates Developmental and Environmental Signals to Promote Hypocotyl Elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2016, 28(9), 2117–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camoirano, A.; Arce, A. L.; Ariel, F. D.; Alem, A. L.; Gonzalez, D. H.; Viola, I. L. Class I TCP transcription factors regulate trichome branching and cuticle development in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2020, 71(18), 5438–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadde, B. V. L.; Challa, K. R.; Sunkara, P.; Hegde, A. S.; Nath, U. The TCP4 Transcription Factor Directly Activates TRICHOMELESS1 and 2 and Suppresses Trichome Initiation. Plant Physiol. 2019, 181(4), 1587–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baulies, J. L.; Bresso, E. G.; Goldy, C.; Palatnik, J. F.; Schommer, C. Potent inhibition of TCP transcription factors by miR319 ensures proper root growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 2022, 108 (1-2), 93-103.

- Yu, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W.; Tian, P.; Wang, W.; Wang, K.; Gao, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Irish, V. F.; Huang, T. TCP5 controls leaf margin development by regulating KNOX and BEL-like transcription factors in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2021, 72(5), 1809–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, T.; Sato, F.; Ohme-Takagi, M. A role of TCP1 in the longitudinal elongation of leaves in Arabidopsis. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2010, 74(10), 2145–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieffer, M.; Master, V.; Waites, R.; Davies, B. TCP14 and TCP15 affect internode length and leaf shape in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2011, 68(1), 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danisman, S.; Van der Wal, F.; Dhondt, S.; Waites, R.; De Folter, S.; Bimbo, A.; Van Dijk, A. D.; Muino, J. M.; Cutri, L.; Dornelas, M. C.; Angenent, G. C.; Immink, R. G. Arabidopsis class I and class II TCP transcription factors regulate jasmonic acid metabolism and leaf development antagonistically. Plant Physiol. 2012, 159(4), 1511–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Martinez, J. A.; Sinha, N. Analysis of the role of Arabidopsis class I TCP genes AtTCP7, AtTCP8, AtTCP22, and AtTCP23 in leaf development. Front Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Q.; Guo, D.; Wei, B.; Zhang, F.; Pang, C.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, J.; Wei, T.; Gu, H.; Qu, L. J.; Qin, G. The TIE1 transcriptional repressor links TCP transcription factors with TOPLESS/TOPLESS-RELATED corepressors and modulates leaf development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013, 25(2), 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, T.; Sato, F.; Ohme-Takagi, M. Roles of miR319 and TCP Transcription Factors in Leaf Development. Plant Physiol. 2017, 175(2), 874–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bresso, E. G.; Chorostecki, U.; Rodriguez, R. E.; Palatnik, J. F.; Schommer, C. Spatial Control of Gene Expression by miR319-Regulated TCP Transcription Factors in Leaf Development. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176(2), 1694–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, L.; Song, S.; Zhao, Y. N.; Gu, H. H.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, J.; Lu, S. ORANGE interplays with TCP7 to regulate endoreduplication and leaf size. Plant J. 2024, 120(2), 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, S. A.; Physiology, C. Arabidopsis TEOSINTE BRANCHED1-LIKE 1 regulates axillary bud outgrowth and is homologous to monocot TEOSINTE BRANCHED1. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2007, 48(5), 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastaldi, V.; Nicolas, M.; Munoz-Gasca, A.; Cubas, P.; Gonzalez, D. H.; Lucero, L. Class I TCP transcription factors TCP14 and TCP15 promote axillary branching in Arabidopsis by counteracting the action of Class II TCP BRANCHED1. New Phytol. 2024, 243(5), 1810–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, G.; Liang, Y.; Hu, L.; Zhu, B.; Qi, D.; Cui, S.; Zhao, H. TCP7 interacts with Nuclear Factor-Ys to promote flowering by directly regulating SOC1 in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2021, 108(5), 1493–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, H.; Mou, M.; Chen, Y.; Xiang, S.; Chen, L.; Yu, D. Arabidopsis Class II TCP Transcription Factors Integrate with the FT-FD Module to Control Flowering. Plant Physiol. 2019, 181(1), 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Mo, X.; Zhong, L.; Zhang, J.; Mo, B.; Kuai, B. , Overexpression of TCP8 delays Arabidopsis flowering through a FLOWERING LOCUS C-dependent pathway. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19(1), 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. F.; Tsai, H. L.; Joanito, I.; Wu, Y. C.; Chang, C. W.; Li, Y. H.; Wang, Y.; Hong, J. C.; Chu, J. W.; Hsu, C. P.; Wu, S. H. LWD-TCP complex activates the morning gene CCA1 in Arabidopsis. Nat Commun. 2016, 7, 13181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, M.; Cubas, P. TCP factors: new kids on the signaling block. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2016, 33, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Es, S. W.; Silveira, S. R.; Rocha, D. I.; Bimbo, A.; Martinelli, A. P.; Dornelas, M. C.; Angenent, G. C.; Immink, R. G. H. Novel functions of the Arabidopsis transcription factor TCP5 in petal development and ethylene biosynthesis. Plant J. 2018, 94(5), 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Irish, V. F. An epigenetic timer regulates the transition from cell division to cell expansion during Arabidopsis petal organogenesis. PLoS Genet. 2024, 20(3), e1011203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nag, A.; King, S.; Jack, T. miR319a targeting of TCP4 is critical for petal growth and development in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009, 106(52), 22534–22539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gastaldi, V.; Lucero, L. E.; Ferrero, L. V.; Ariel, F. D.; Gonzalez, D. H. Class-I TCP Transcription Factors Activate the SAUR63 Gene Subfamily in Gibberellin-Dependent Stamen Filament Elongation. Plant Physiol. 2020, 182(4), 2096–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucero, L. E.; Uberti-Manassero, N. G.; Arce, A. L.; Colombatti, F.; Alemano, S. G.; Gonzalez, D. H. TCP15 modulates cytokinin and auxin responses during gynoecium development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2015, 84(2), 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, N.; Lan, J.; Pan, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, X.; Feng, X.; Qin, G. Arabidopsis transcription factor TCP4 controls the identity of the apical gynoecium. Plant Cell. 2024, 36(7), 2668–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Wang, N.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, H.; Cao, X.; Qin, G. Arabidopsis TCP4 transcription factor inhibits high temperature-induced homeotic conversion of ovules. Nat Commun. 2023, 14(1), 5673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastaldi, V.; Alem, A. L.; Mansilla, N.; Ariel, F. D.; Viola, I. L.; Lucero, L. E.; Gonzalez, D. H. BREVIPEDICELLUS/KNAT1 targets TCP15 to modulate filament elongation during Arabidopsis late stamen development. Plant Physiol. 2023, 191(1), 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Guo, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, N.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, L.; Yu, D.; Zhang, B.; Qin, G. Rice transcriptional repressor OsTIE1 controls anther dehiscence and male sterility by regulating JA biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 2024, 36(5), 1697–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Mao, Y.; Yang, J.; He, Y. TCP24 modulates secondary cell wall thickening and anther endothecium development. Front Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Pan, Z.; Kong, W.; Mo, B.; Chen, X.; Yu, Y. miR319-TCPs-TGA9/TGA10/ROXY2 regulatory module controls cell fate specification in early anther development in Arabidopsis. Sci China Life Sci. 2024, 67(4), 839–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grefen, C.; Donald, N.; Hashimoto, K.; Kudla, J.; Schumacher, K.; Blatt, M. R. A ubiquitin-10 promoter-based vector set for fluorescent protein tagging facilitates temporal stability and native protein distribution in transient and stable expression studies. Plant J. 2010, 64(2), 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, P. M.; Bui, A. Q.; Weterings, K.; McIntire, K. N.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Lee, P. Y.; Truong, M. T.; Beals, T. P.; Goldberg, R. B. Anther developmental defects in Arabidopsis thaliana male-sterile mutants. Sexual Plant Reproduction. 1999, 11(6), 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D. M.; Zeef, L. A.; Ellis, J.; Goodacre, R.; Turner, S. R. Identification of novel genes in Arabidopsis involved in secondary cell wall formation using expression profiling and reverse genetics. Plant Cell. 2005, 17(8), 2281–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Avci, U.; Tan, L.; Zhu, X.; Glushka, J.; Pattathil, S.; Eberhard, S.; Sholes, T.; Rothstein, G. E.; Lukowitz, W.; Orlando, R.; Hahn, M. G.; Mohnen, D. Loss of Arabidopsis GAUT12/IRX8 causes anther indehiscence and leads to reduced G lignin associated with altered matrix polysaccharide deposition. Front Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N. G. Cellulose biosynthesis and deposition in higher plants. New phytologist. 2008, 178(2), 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, M. J.; Zhong, R.; Zhou, G. K.; Richardson, E. A.; O'Neill, M. A.; Darvill, A. G.; York, W. S.; Ye, Z. H. Arabidopsis irregular xylem8 and irregular xylem9: implications for the complexity of glucuronoxylan biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 2007, 19(2), 549–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goujon, T.; Sibout, R.; Eudes, A.; MacKay, J.; Jouanin, L.; Biochemistry. Genes involved in the biosynthesis of lignin precursors in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiology and Biochemistr. 2003, 41(8), 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Xu, Z.; Song, J.; Conner, K.; Vizcay Barrena, G.; Wilson, Z. A. Arabidopsis MYB26/MALE STERILE35 regulates secondary thickening in the endothecium and is essential for anther dehiscence. Plant Cell. 2007, 19(2), 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Song, J.; Ferguson, A. C.; Klisch, D.; Simpson, K.; Mo, R.; Taylor, B.; Mitsuda, N.; Wilson, Z. A. Transcription Factor MYB26 is key to spatial specificity in anther secondary thickening formation. Plant Physiol. 2017, 175(1), 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner-Lange, S.; Unte, U. S.; Eckstein, L.; Yang, C.; Wilson, Z. A.; Schmelzer, E.; Dekker, K.; Saedler, H. Disruption of Arabidopsis thaliana MYB26 results in male sterility due to non-dehiscent anthers. Plant J. 2003, 34(4), 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsuda, N.; Seki, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Ohme-Takagi, M. The NAC transcription factors NST1 and NST2 of Arabidopsis regulate secondary wall thickenings and are required for anther dehiscence. Plant Cell. 2005, 17(11), 2993–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K. W.; Oh, S.-I.; Kim, Y. Y.; Yoo, K. S.; Cui, M. H.; Shin, J. S. Arabidopsis Histidine-containing Phosphotransfer Factor 4 (AHP4) negatively regulates secondary wall thickening of the anther endothecium during flowering. Molecules and Cells. 2008, 25(2), 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S. L.; Xie, L. F.; Mao, H. Z.; Puah, C. S.; Yang, W. C.; Jiang, L.; Sundaresan, V.; Ye, D. Tapetum determinant1 is required for cell specialization in the Arabidopsis anther. Plant Cell. 2003, 15(12), 2792–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hord, C. L.; Chen, C.; Deyoung, B. J.; Clark, S. E.; Ma, H. The BAM1/BAM2 receptor-like kinases are important regulators of Arabidopsis early anther development. Plant Cell. 2006, 18(7), 1667–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, A. M.; Krober, S.; Unte, U. S.; Huijser, P.; Dekker, K.; Saedler, H. The Arabidopsis ABORTED MICROSPORES (AMS) gene encodes a MYC class transcription factor. Plant J. 2003, 33(2), 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sun, Y.; Timofejeva, L.; Chen, C.; Grossniklaus, U.; Ma, H. Regulation of Arabidopsis tapetum development and function by DYSFUNCTIONAL TAPETUM1 (DYT1) encoding a putative bHLH transcription factor. Development. 2006, 133(16), 3085–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.; Zachgo, S. ROXY1 and ROXY2, two Arabidopsis glutaredoxin genes, are required for anther development. Plant J. 2008, 53(5), 790–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.; Salinas, M.; Hohmann, S.; Berndtgen, R.; Huijser, P. miR156-targeted and nontargeted SBP-box transcription factors act in concert to secure male fertility in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2010, 22(12), 3935–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murmu, J.; Bush, M. J.; DeLong, C.; Li, S.; Xu, M.; Khan, M.; Malcolmson, C.; Fobert, P. R.; Zachgo, S.; Hepworth, S. R. Arabidopsis basic leucine-zipper transcription factors TGA9 and TGA10 interact with floral glutaredoxins ROXY1 and ROXY2 and are redundantly required for anther development. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154(3), 1492–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.; Quodt, V.; Chandler, J.; Hohmann, S.; Berndtgen, R.; Huijser, P. SPL8 Acts Together with the Brassinosteroid-Signaling Component BIM1 in Controlling Arabidopsis thaliana Male Fertility. Plants (Basel). 2013, 2(3), 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unte, U. S.; Sorensen, A. M.; Pesaresi, P.; Gandikota, M.; Leister, D.; Saedler, H.; Huijser, P. SPL8, an SBP-box gene that affects pollen sac development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2003, 15(4), 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, C.; Russinova, E.; Hecht, V.; Baaijens, E.; De Vries, S. The Arabidopsis thaliana SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASES1 and 2 control male sporogenesis. Plant Cell. 2005, 17(12), 3337–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D. Z.; Wang, G. F.; Speal, B.; Ma, H. The excess microsporocytes1 gene encodes a putative leucine-rich repeat receptor protein kinase that controls somatic and reproductive cell fates in the Arabidopsis anther. Genes Dev. 2002, 16(15), 2021–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W-C.; Ye, D.; Xu, J.; Sundaresan, V. The SPOROCYTELESS gene of Arabidopsis is required for initiation of sporogenesis and encodes a novel nuclear protein. Genes & development. 1999, 13 (16), 2108-2117.

- Millar, A. A.; Gubler, F. The Arabidopsis GAMYB-like genes, MYB33 and MYB65, are microRNA-regulated genes that redundantly facilitate anther development. Plant Cell. 2005, 17(3), 705–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiratsu, K.; Matsui, K.; Koyama, T.; Ohme-Takagi, M. Dominant repression of target genes by chimeric repressors that include the EAR motif, a repression domain, in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2003, 34(5), 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrand, J.; Knight, C.; Robson, J.; Talle, B.; Wilson, Z. A. , Evolution and diversity of the angiosperm anther: trends in function and development. Plant Reprod. 2021, 34(4), 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Zhang, J.; Pang, C.; Yu, H.; Guo, D.; Jiang, H.; Ding, M.; Chen, Z.; Tao, Q.; Gu, H.; Qu, L. J.; Qin, G. The molecular mechanism of sporocyteless/nozzle in controlling Arabidopsis ovule development. Cell Res. 2015, 25(1), 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G. H.; Sun, J. Y.; Liu, M.; Liu, J.; Yang, W. C. SPOROCYTELESS is a novel embryophyte-specific transcription repressor that interacts with TPL and TCP proteins in Arabidopsis. J Genet Genomics. 2014, 41(12), 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauser, F.; Schiml, S.; Puchta, H. Both CRISPR/Cas-based nucleases and nickases can be used efficiently for genome engineering in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2014, 79(2), 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asseck, L. Y.; Mehlhorn, D. G.; Monroy, J. R.; Ricardi, M. M.; Breuninger, H.; Wallmeroth, N.; Berendzen, K. W.; Nowrousian, M.; Xing, S.; Schwappach, B.; Bayer, M.; Grefen, C. Endoplasmic reticulum membrane receptors of the GET pathway are conserved throughout eukaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021, 118(1), e2017636118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, T. L.; Shimada, T.; Hara-Nishimura, I. A rapid and non-destructive screenable marker, FAST, for identifying transformed seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2010, 61(3), 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, D.; Kemper, E.; Schell, J.; Masterson, R. New plant binary vectors with selectable markers located proximal to the left T-DNA border. Plant molecular biology. 1992, 20, 1195–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough, S. J.; Bent, A. F. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998, 16(6), 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M. P. Differential staining of aborted and nonaborted pollen. Stain technology. 1969, 44(3), 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.; Rosso, M. G.; Zachgo, S. ROXY1, a member of the plant glutaredoxin family, is required for petal development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 2005, 132(7), 1555–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).