Submitted:

27 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

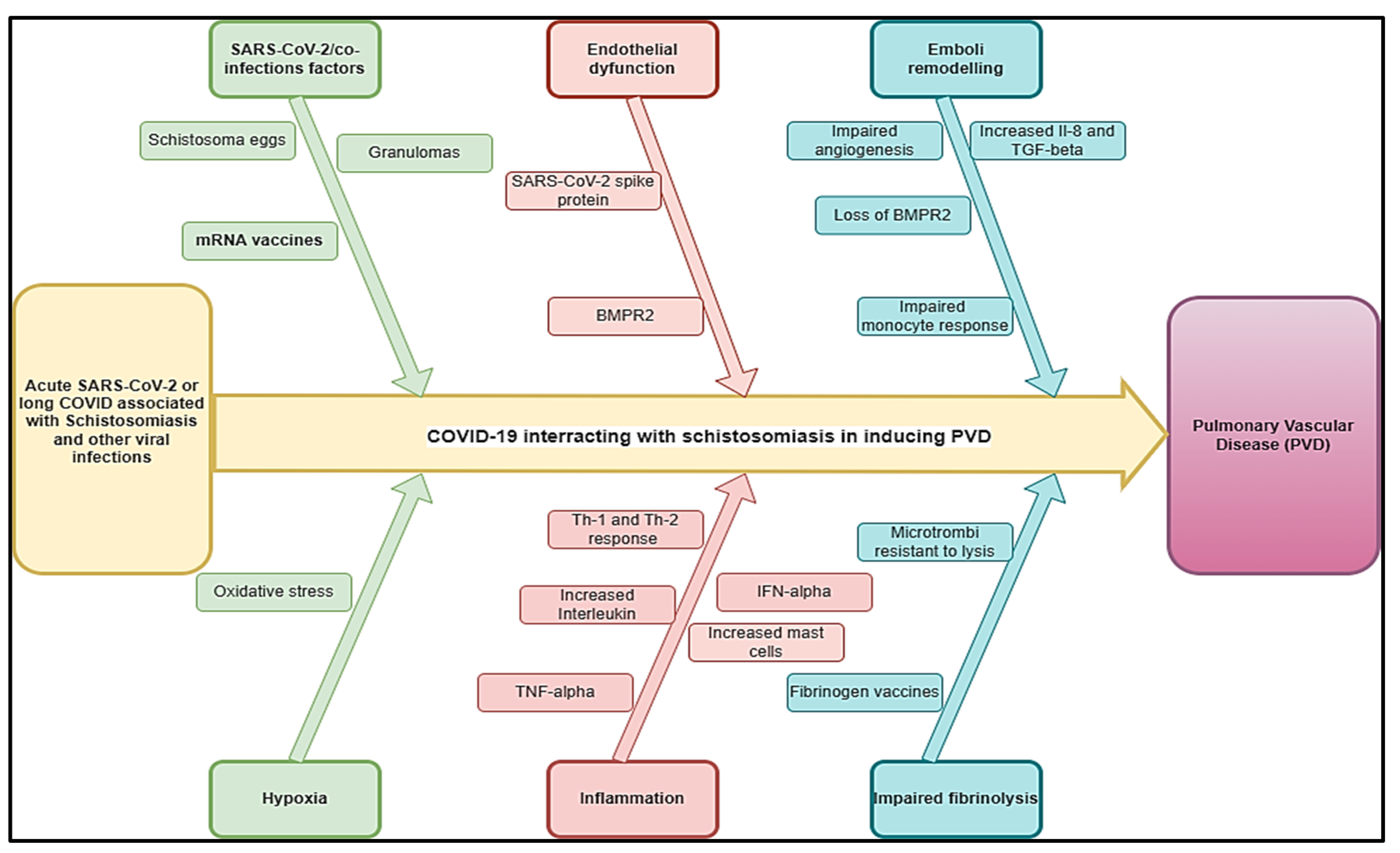

2. COVID-19 and Parasitic Co-Infection

2.1. Schistosomiasis and Other Helminthic Diseases

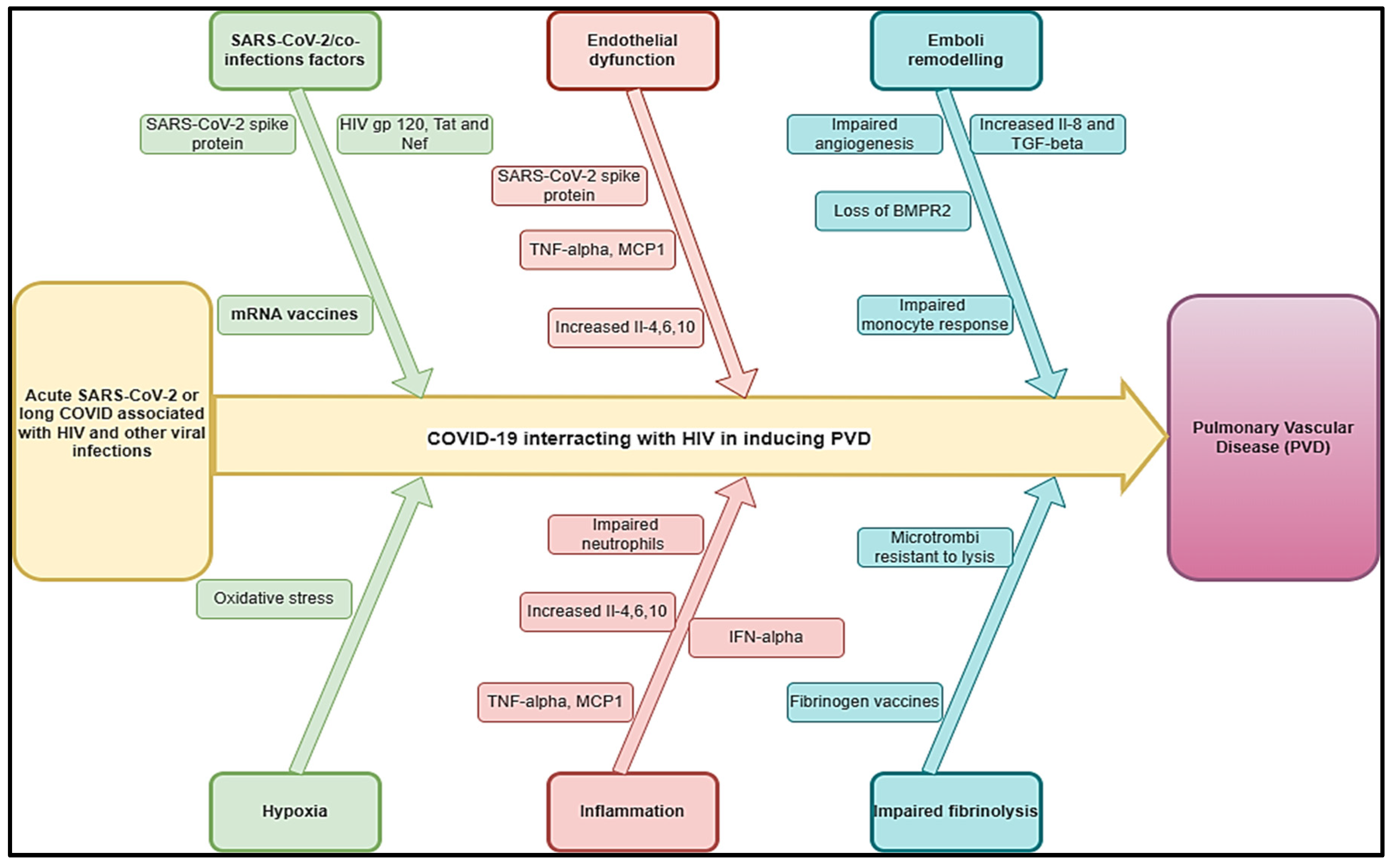

2.2. HIV and Viral Infections like Other Human Herpesviruses

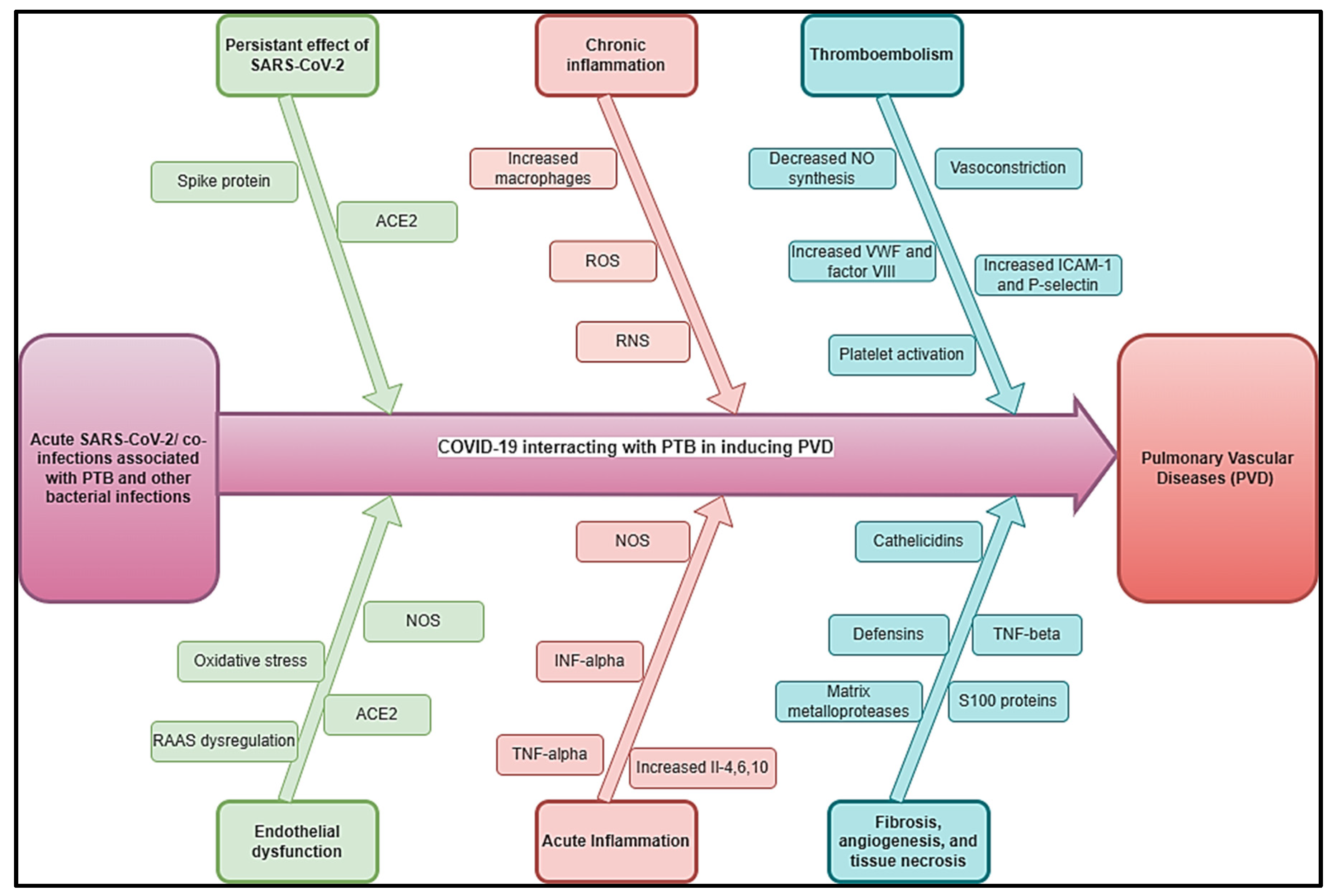

2.3. Tuberculosis and Other Bacterial Infections

2.4. Pulmonary aspergillosis and Other Fungal Infections

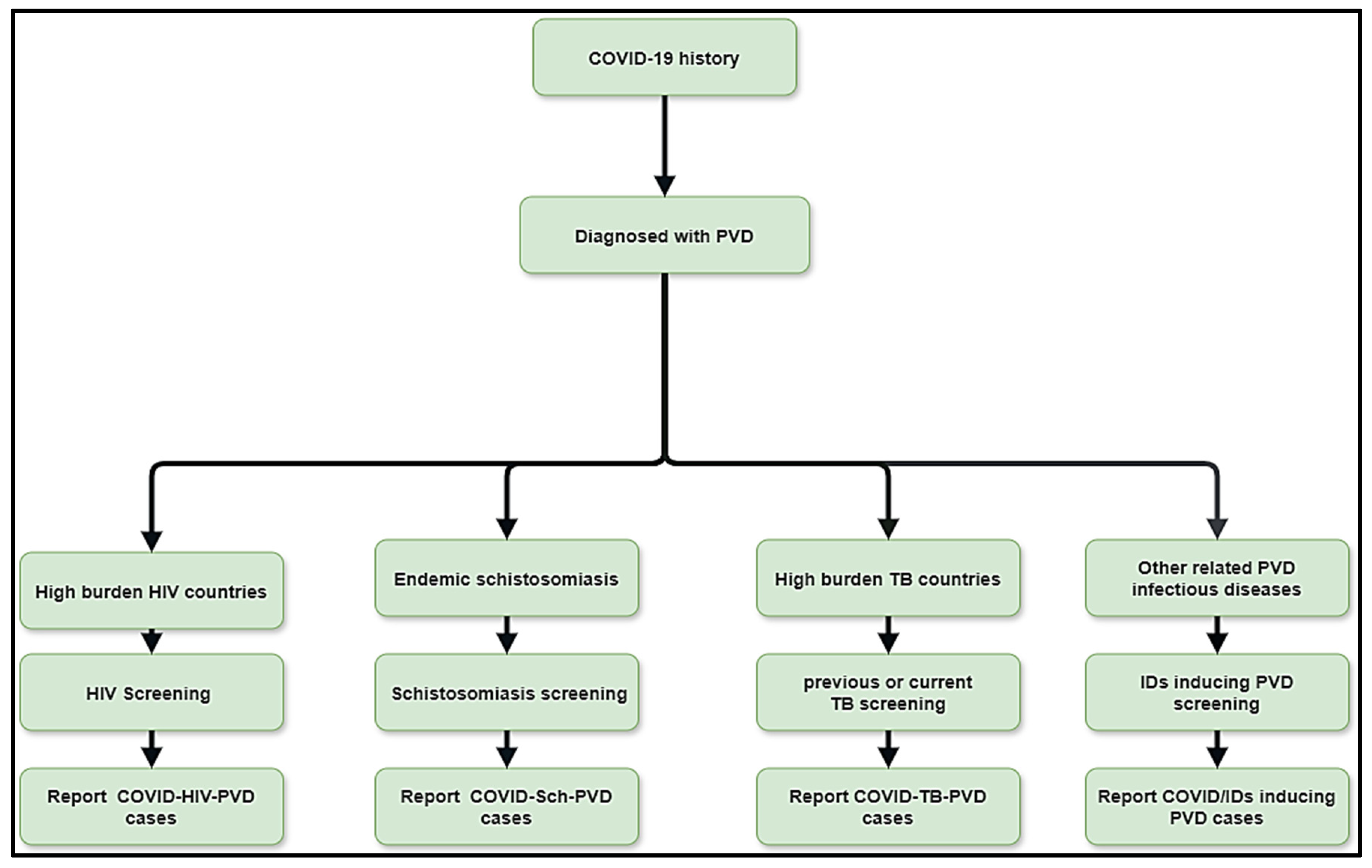

3. A Multidisciplinary Diagnostic and Management Approach of PVDs Related to COVID-19 Co-Infections Is Important

4. Conclusion

Abbreviation

References

- Simonneau, G.; Montani, D.; Celermajer, D.S.; Denton, C.P.; Gatzoulis, M.A.; Krowka, M.; et al. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melot, C.; Naeije, R. Pulmonary vascular diseases. Compr Physiol. 2011, 1, 593–619. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hatano S, Strasser T, World Health Organization. Primary pulmonary hypertension: report on a WHO meeting, Geneva, 15-17 October 1973. World Health Organization; 1975.

- Kovacs, G.; Maier, R.; Aberer, E.; Brodmann, M.; Scheidl, S.; Tröster, N.; et al. Borderline pulmonary arterial pressure is associated with decreased exercise capacity in scleroderma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009, 180, 881–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmons-Bell, S.; Johnson, C.; Boon-Dooley, A.; Corris, P.A.; Leary, P.J.; Rich, S.; et al. Prevalence, incidence, and survival of pulmonary arterial hypertension: A systematic review for the global burden of disease 2020 study. Pulm Circ. 2022, 12, e12020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castiglione, L.; Droppa, M. Pulmonary Hypertension and COVID-19. Hamostaseologie. 2022, 42, 230–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potus, F.; Mai, V.; Lebret, M.; Malenfant, S.; Breton-Gagnon, E.; Lajoie, A.C.; et al. Novel insights on the pulmonary vascular consequences of COVID-19. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2020, 319, L277–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnesi, M.; Baldetti, L.; Beneduce, A.; Calvo, F.; Gramegna, M.; Pazzanese, V.; et al. Pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular involvement in hospitalised patients with COVID-19. Heart. 2020, 106, 1324–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar R, Aktay-Cetin Ö, Craddock V, Morales-Cano D, Kosanovic D, Cogolludo A. ; et al. Potential long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the pulmonary vasculature: Multilayered cross-talks in the setting of coinfections and comorbidities. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011063.

- Musuuza, J.S.; Watson, L.; Parmasad, V.; Putman-Buehler, N.; Christensen, L.; Safdar, N. Prevalence and outcomes of co-infection and superinfection with SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogens: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2021, 16, e0251170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egom, E.À.; Shiwani, H.A.; Nouthe, B. Egom EÀ, Shiwani HA, Nouthe B. From acute SARS-CoV-2 infection to pulmonary hypertension. Front Physiol. 2022, 13, 1023758. [Google Scholar]

- Taha, H.A.; Elshafey, B.I.; Abdullah, T.M.; Salem, H.A. Study of pulmonary hypertension in post-COVID-19 patients by transthoracic echocardiography. Egypt J Bronchol. 2023, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktaviono, Y.H.; Mulia, E.P.B.; Luke, K.; Nugraha, D.; Maghfirah, I.; Subagjo, A. Right ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension in COVID-19: a meta-analysis of prevalence and its association with clinical outcome. Arch Med Sci AMS. 2022, 18, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butrous, G. Human immunodeficiency virus–associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: considerations for pulmonary vascular diseases in the developing world. Circulation. 2015, 131, 1361–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medrano-Garcia, S.; Morales-Cano, D.; Barreira, B.; Vera-Zambrano, A.; Kumar, R.; Kosanovic, D.; et al. HIV and Schistosoma Co-Exposure Leads to Exacerbated Pulmonary Endothelial Remodeling and Dysfunction Associated with Altered Cytokine Landscape. Cells. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butrous, G.; Mathie, A. Infection in pulmonary vascular diseases: Would another consortium really be the way to go? Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2019, 2019, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butrous, G. The global challenge of pulmonary vascular diseases and its forgotten impact in the developing world. Adv Pulm Hypertens. 2012, 11, 117–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butrous, G. Pulmonary Vascular Diseases Secondary to Schistosomiasis. Adv Pulm Hypertens. 2017, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolosionek, E.; Crosby, A.; Harhay, M.O.; Morrell, N.; Butrous, G. Pulmonary vascular disease associated with schistosomiasis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2010, 8, 1467–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Deng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, W.; Huang, Y.; et al. A retrospective analysis of schistosomiasis related literature from 2011-2020: Focusing on the next decade. Acta Trop. 2023, 238, 106750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolosionek, E.; Crosby, A.; Harhay, M.O.; Morrell, N.; Butrous, G. Pulmonary vascular disease associated with schistosomiasis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2010, 8, 1467–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Cleva R, Herman P, Pugliese V, Zilberstein B, Saad WA, Rodrigues J. ; et al. Prevalence of pulmonary hypertension in patients with hepatosplenic Mansonic schistosomiasis--prospective study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003, 50, 2028–30.

- Rohun, J.; Dorniak, K.; Faran, A.; Kochańska, A.; Zacharek, D.; Daniłowicz-Szymanowicz, L. Long COVID-19 myocarditis and various heart failure presentations: a case series. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2022, 9, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolday, D.; Gebrecherkos, T.; Arefaine, Z.G.; Kiros, Y.K.; Gebreegzabher, A.; Tasew, G.; et al. Effect of co-infection with intestinal parasites on COVID-19 severity: a prospective observational cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2021, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Gebrecherkos, T.; Gessesse, Z.; Kebede, Y.; Gebreegzabher, A.; Tasew, G.; Abdulkader, M.; et al. Effect of co-infection with parasites on severity of COVID-19. medRxiv. 2021, 2021–02. [Google Scholar]

- Obeyesekere, I.; Peiris, D. Pulmonary hypertension and filariasis. Br Heart J. 1974, 36, 676–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walloopillai, N. Primary pulmonary hypertension, an unexplained epidemic in Sri Lanka. Pathobiology. 1975, 43, 248–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.; McFadzean, A.; Yeung, R. Microembolic pulmonary hypertension in pyogenic cholangitis. Br Med J. 1968, 1, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.G.; Sleigh, A.C.; Li, Y.; Davis, G.M.; Williams, G.M.; Jiang, Z.; et al. Schistosomiasis in the People’s Republic of China: prospects and challenges for the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001, 14, 270–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halawa, S.; Pullamsetti, S.S.; Bangham, C.R.; Stenmark, K.R.; Dorfmüller, P.; Frid, M.G.; et al. Potential long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the pulmonary vasculature: a global perspective. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022, 19, 314–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.K.; Nyasulu, P.S.; Iqbal, A.A.; Hamdan Gul, M.; Ferreira, E.V.; Leclair, J.W.; et al. Cardiopulmonary disease as sequelae of long-term COVID-19: Current perspectives and challenges. Front Med. 2022, 9, 1041236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijkeuter, M.; Hovens, M.M.; Davidson, B.L.; Huisman, M.V. Resolution of thromboemboli in patients with acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review. Chest. 2006, 129, 192–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pullamsetti, S.; Savai, R.; Janssen, W.; Dahal, B.; Seeger, W.; Grimminger, F.; et al. Inflammation, immunological reaction and role of infection in pulmonary hypertension. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011, 17, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, L.J. Pulmonary arterial hypertension. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006, 3, 111–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budhiraja, R.; Tuder, R.M.; Hassoun, P.M. Endothelial dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2004, 109, 159–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassoun, P.M.; Mouthon, L.; Barberà, J.A.; Eddahibi, S.; Flores, S.C.; Grimminger, F.; et al. Inflammation, growth factors, and pulmonary vascular remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009, 54, S10–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andruska, A.; Spiekerkoetter, E. Consequences of BMPR2 deficiency in the pulmonary vasculature and beyond: contributions to pulmonary arterial hypertension. Int J Mol Sci. 2018, 19, 2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogo, T.; Chowdhury, H.; Yang, J.; Long, L.; Li, X.; Torres Cleuren, Y.N.; et al. Inhibition of overactive transforming growth factor–β signaling by prostacyclin analogs in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013, 48, 733–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burel-Vandenbos, F.; Cardot-Leccia, N.; Passeron, T. Apoptosis and pericyte loss in alveolar capillaries in COVID-19 infection: choice of markers matters. Author’s reply. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 1967–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyeyemi, O.; Okunlola, O.; Adebayo, A. Assessment of schistosomiasis endemicity and preventive treatment on coronavirus disease 2019 outcomes in Africa. New Microbes New Infect. 2020, 38, 100821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maizels, R.M.; McSorley, H.J. Regulation of the host immune system by helminth parasites. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016, 138, 666–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, T.C.A.; Albricker, A.C.L.; Gonçalves, I.M.; Freire, C.M.V. Schistosome-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: a review emphasizing pathogenesis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021, 8, 724254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Mickael, C.; Chabon, J.; Gebreab, L.; Rutebemberwa, A.; Garcia, A.R.; et al. The causal role of IL-4 and IL-13 in Schistosoma mansoni pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015, 192, 998–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butrous, G.; Ghofrani, H.A.; Grimminger, F. Pulmonary vascular disease in the developing world. Circulation. 2008, 118, 1758–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, B.C.; Freeman, C.M.; Stolberg, V.R.; Komuniecki, E.; Lincoln, P.M.; Kunkel, S.L.; et al. Cytokine–chemokine networks in experimental mycobacterial and schistosomal pulmonary granuloma formation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003, 29, 106–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boros, D.L.; Whitfield, J.R. Enhanced Th1 and dampened Th2 responses synergize to inhibit acute granulomatous and fibrotic responses in murine schistosomiasis mansoni. Infect Immun. 1999, 67, 1187–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, R. How do the severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and its variants escape the host protective immunity and mediate pathogenesis? Bull Natl Res Cent. 2022, 46, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DAvila-Mesquita, C.; Couto, A.E.S.; Campos, L.C.B.; Vasconcelos, T.F.; Michelon-Barbosa, J.; Corsi, C.A.C.; et al. MMP-2 and MMP-9 levels in plasma are altered and associated with mortality in COVID-19 patients. Biomed Pharmacother Biomedecine Pharmacother. 2021, 142, 112067. [Google Scholar]

- Laveaux, S.; Vandecasteele, S.; Van De Moortele, K. Chronic Schistosomiasis Presenting with Migrating Pulmonary Manifestation after Recent COVID-19 Infection: HRCT Findings. J Belg Soc Radiol. 2022, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.D.; Jackson, J.A.; Faulkner, H.; Behnke, J.; Else, K.J.; Kamgno, J.; et al. Intensity of intestinal infection with multiple worm species is related to regulatory cytokine output and immune hyporesponsiveness. J Infect Dis. 2008, 197, 1204–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, S.; Nutman, T.B. Immunology of lymphatic filariasis. Parasite Immunol. 2014, 36, 338–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, G.; Barjatya, H.; Bhakar, B.; Gothwal, S.K.; Jangir, T. To estimate prevalence of pulmonary arterial hypertension in HIV patients and its association with CD4 cell count. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2024, 25, 101479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNAIDS Global HIV statistics [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_FactSheet_en.pdf.

- Hoeper, M.M.; Humbert, M.; Souza, R.; Idrees, M.; Kawut, S.M.; Sliwa-Hahnle, K.; et al. A global view of pulmonary hypertension. Lancet Respir Med. 2016, 4, 306–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almodovar, S.; Cicalini, S.; Petrosillo, N.; Flores, S.C. Pulmonary hypertension associated with HIV infection: pulmonary vascular disease: the global perspective. Chest. 2010, 137, 6S–12S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal S, Sharma H, Chen L, Dhillon NK. NADPH oxidase-mediated endothelial injury in HIV- and opioid-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2020, 318, L1097–108.

- Porter, K.M.; Walp, E.R.; Elms, S.C.; Raynor, R.; Mitchell, P.O.; Guidot, D.M.; et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 transgene expression increases pulmonary vascular resistance and exacerbates hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension development. Pulm Circ. 2013, 3, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuche, J.; Pérez-Olivares, C.; de la Cal, T.S.; López-Guarch, C.J.; Ynsaurriaga, F.A.; Subías, P.E. Clinical course of COVID-19 in pulmonary arterial hypertension patients. Rev Espanola Cardiol Engl Ed. 2020, 73, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danwang, C.; Noubiap, J.J.; Robert, A.; Yombi, J.C. Outcomes of patients with HIV and COVID-19 co-infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Res Ther. 2022, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta NJ, Khan IA, Mehta RN, Sepkowitz DA. HIV-related pulmonary hypertension: analytic review of 131 cases. Chest. 2000, 118, 1133–41.

- Suresh SJ, Suzuki YJ. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and lung vascular cells. J Respir. 2020, 1, 40–8.

- Dorfmüller, P.; Perros, F.; Balabanian, K.; Humbert, M. Inflammation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2003, 22, 358–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butrous, G. Human immunodeficiency viruses and their effect on the pulmonary vascular bed. Am J Physiol-Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2021, 321, L1062–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cool, C.D.; Rai, P.R.; Yeager, M.E.; Hernandez-Saavedra, D.; Serls, A.E.; Bull, T.M.; et al. Expression of human herpesvirus 8 in primary pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2003, 349, 1113–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, N.M.; Lederer, D.J.; Borczuk, A.C.; Kawut, S.M. Pulmonary hypertension in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2007, 132, 998–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.; Longhurst, H.J.; Paxton, J.K.; Scotton, C.J. The role of herpes viruses in pulmonary fibrosis. Front Med. 2021, 8, 704222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, F.; Kipar, A.; Lunardi, F.; Balestro, E.; Perissinotto, E.; Rossi, E.; et al. Herpes virus infection is associated with vascular remodeling and pulmonary hypertension in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e55715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubchenko, S.; Kril, I.; Nadizhko, O.; Matsyura, O.; Chopyak, V. Herpesvirus infections and post-COVID-19 manifestations: a pilot observational study. Rheumatol Int. 2022, 42, 1523–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Gidda, H.; Zavoshi, S.; Mahmood, R. A Case of Left Ventricular Thrombus and Herpetic Esophagitis in an Immunocompetent Patient With COVID-19. Cureus. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, P.; Saha, D.; Bhattacherjee, P.D.; Das, S.K.; Bhattacharyya, P.P.; Dey, R. Tuberculosis associated pulmonary hypertension: The revelation of a clinical observation. Lung India Off Organ Indian Chest Soc. 2016, 33, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louw, E.; Baines, N.; Maarman, G.; Osman, M.; Sigwadhi, L.; Irusen, E.; et al. The prevalence of pulmonary hypertension after successful tuberculosis treatment in a community sample of adult patients. Pulm Circ. 2023, 13, e12184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galie, N.; Hoeper, M.M.; Humbert, M.; Torbicki, A.; Vachiery, J.L.; Barbera, J.A.; et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), endorsed by the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J. 2009, 30, 2493–537. [Google Scholar]

- Tamuzi, J.L.; Lulendo, G.; Mbuesse, P.; Nyasulu, P.S. The incidence and mortality of COVID-19 related TB disease in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv. 2022, 2022–01. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.E.H.; Ibrahim, A.S.; Elshafie, S.M. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with treated pulmonary tuberculosis: analysis of 14 consecutive cases. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med. 2011, 5, CCRPM–S6437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.S.; Park, J.H.; Lee, J.K.; Heo, E.Y.; Chung, H.S.; Kim, D.K. Risk factors for pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients with tuberculosis-destroyed lungs and their clinical characteristics compared with patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017, 2433–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, D.G.; Cardona, P.J.; Kim, M.J.; Allain, S.; Altare, F. Foamy macrophages and the progression of the human tuberculosis granuloma. Nat Immunol. 2009, 10, 943–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, S. Pathogenesis of cor pulmonale in pulmonary tuberculosis. 1986.

- Zouaki I, Chahbi Z, Raiteb M, Zyani M. COVID-19 and Pulmonary Tuberculosis Coinfection in a Moroccan Patient with Pulmonary Embolism: A Case Report and Literature Review. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2022, 2022.

- Parolina, L.; Pshenichnaya, N.; Vasilyeva, I.; Lizinfed, I.; Urushadze, N.; Guseva, V.; et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in patients with tuberculosis and factors associated with the disease severity. Int J Infect Dis. 2022, 124, S82–S89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Xia, X.; Nie, D.; Yang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Huo, X.; et al. Respiratory bacterial pathogen spectrum among COVID-19 infected and non-COVID-19 virus infected pneumonia patients. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020, 98, 115199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Cao, Y.; Liu, X.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of Tuberculosis and COVID-19 Co-infection: Prevalence, fatality, and treatment considerations. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2024, 18, e0012136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.T.; Carcillo, J.A.; Shanley, T.P.; Wessel, D.L.; Clark, A.; Holubkov, R.; et al. Critical pertussis illness in children: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Pediatr Crit Care Med J Soc Crit Care Med World Fed Pediatr Intensive Crit Care Soc. 2013, 14, 356–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeican, I.I.; Inișca, P.; Gheban, D.; Tăbăran, F.; Aluaș, M.; Trombitas, V.; et al. COVID-19 and Pneumocystis jirovecii pulmonary coinfection—the first case confirmed through autopsy. Medicina (Mex). 2021, 57, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saibaba, J.; Selvaraj, J.; Viswanathan, S.; Pillai, V.; Saibaba Jr, J. Scrub Typhus and COVID-19 Coinfection Unmasking Antiphospholipid Antibody Syndrome. Cureus. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udwadia ZF, Vora A, Tripathi AR, Malu KN, Lange C, Raju RS. COVID-19-Tuberculosis interactions: When dark forces collide. Indian J Tuberc. 2020, 67, S155–62.

- Tamuzi, J.L.; Ayele, B.T.; Shumba, C.S.; Adetokunboh, O.O.; Uwimana-Nicol, J.; Haile, Z.T.; et al. Implications of COVID-19 in high burden countries for HIV/TB: A systematic review of evidence. BMC Infect Dis. 2020, 20, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsenova, L.; Singhal, A. Effects of host-directed therapies on the pathology of tuberculosis. J Pathol. 2020, 250, 636–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bari, V.; Gualano, G.; Musso, M.; Libertone, R.; Nisii, C.; Ianniello, S.; et al. Increased association of pulmonary thromboembolism and tuberculosis during COVID-19 pandemic: data from an Italian infectious disease referral hospital. Antibiotics. 2022, 11, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thachil, J.; Tang, N.; Gando, S.; Falanga, A.; Cattaneo, M.; Levi, M.; et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020, 18, 1023–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paddock, C.D.; Sanden, G.N.; Cherry, J.D.; Gal, A.A.; Langston, C.; Tatti, K.M.; et al. Pathology and pathogenesis of fatal Bordetella pertussis infection in infants. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2008, 47, 328–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, K.H.T.; Duclos, P.; Nelson, E.A.S.; Hutubessy, R.C.W. An update of the global burden of pertussis in children younger than 5 years: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017, 17, 974–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Wang, L.; Du, S.; Fan, H.; Yu, M.; Ding, T.; et al. Mortality risk factors among hospitalized children with severe pertussis. BMC Infect Dis. 2021, 21, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flikweert, A.W.; Grootenboers, M.J.; Yick, D.C.; du Mee, A.W.; van der Meer, N.J.; Rettig, T.C.; et al. Late histopathologic characteristics of critically ill COVID-19 patients: Different phenotypes without evidence of invasive aspergillosis, a case series. J Crit Care. 2020, 59, 149–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Arkel AL, Rijpstra TA, Belderbos HN, Van Wijngaarden P, Verweij PE, Bentvelsen RG. COVID-19–associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020, 202, 132–135.

- Chethan, M.; Devi, H.; Deshmukh, S. Pleural aspergillosis with pulmonary artery thrombosis as a complication of Covid-19. Lung India. 2022, S214–S214. [Google Scholar]

- Lamoth, F.; Glampedakis, E.; Boillat-Blanco, N.; Oddo, M.; Pagani, J.L. Incidence of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis among critically ill COVID-19 patients. Clin Microbiol Infect Off Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020, 26, 1706–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauvet, P.; Mallat, J.; Arumadura, C.; Vangrunderbeek, N.; Dupre, C.; Pauquet, P.; et al. Risk Factors for Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis in Critically Ill Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019-Induced Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Crit Care Explor. 2020, 2, e0244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DYee, C.; Aung, H.K.K.; Mg Mg, B.; Htun, W.P.P.; Janurian, N.; Pyae Phyo, A.; et al. Case Report: A case report of multiple co-infections (melioidosis, paragonimiasis, Covid-19 and tuberculosis) in a patient with diabetes mellitus and thalassemia-trait in Myanmar. Wellcome Open Res. 2022, 7. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).