1. Introduction

Image reconnaissance involves gathering information using various imaging technologies and sensors. Currently, satellite systems, aerial reconnaissance platforms, and unmanned aerial vehicles, supported by diverse optical tools, radars, and lasers, are most commonly used for this purpose [

1]. Imaging has become a critical component in modern applications due to technological advances that have greatly improved techniques for capturing and transmitting images These systems are widely used in fields such as environmental monitoring, disaster response, and infrastructure analysis, where precise and timely information is essential [

2,

3].

The speed and efficiency of image reconnaissance systems are crucial for enabling real-time decision-making and accurate analysis. However, these systems face numerous challenges that can significantly impact their effectiveness. Maintaining high detection and identification efficiency in disrupted environments ensures reliable performance and enhances situational awareness [

3]. Factors causing disturbances in image reconnaissance systems include:

Atmospheric Factors - Reduced visibility due to rain, fog, or sandstorms can hinder object detection, while artifacts from atmospheric disturbances may lead to incorrect classifications or object omissions [

5,

6].

Deliberate Interference - Intentional disruptions can be introduced through techniques such as masking or signal interference. For example, the use of camouflage [

7] an make objects less visible or entirely undetectable to imaging systems. Signal disruptions, particularly in drone-based systems, can destabilize image feeds, cause signal loss, or result in other distortions that hinder the collection of accurate data [

8].

Lossy Compression– Bandwidth limitations in telecommunication channels [

9] necessitate lossy compression in reconnaissance systems, which, depending on the compression level, can introduce artifacts leading to detail loss. This significantly reduces detection efficiency, especially for smaller or less distinct objects [

10,

11].

Object Dynamics - When capturing objects from long distances, e.g., using drones or satellite systems, the movement of the observed object or camera can cause image blur. This reduces contour sharpness, complicating object detection and classification [

12,

13].

The above disruptive factors can have significant consequences, impacting the reliability and effectiveness of imaging reconnaissance systems [

14]. These include misclassification of objects, low detection efficiency and the occurrence of numerous false alarms [

15], which translates into:

reduced efficiency due to increased response times and delays in critical decision-making [

16],

greater strain on resources, as inappropriate actions triggered by false alarms divert attention from actual priorities. This can lead to reduced confidence in the technology and a tendency to disregard alerts,

loss of informational advantage, providing opportunities for unforeseen events or delays in addressing critical situations, ultimately compromising the effectiveness of operations [

17].

The malfunctioning of the reconnaissance system can even lead to tragic consequences such as: the downing of an Iranian passenger plane in 1988, which was misidentified as an F-14 fighter [

18], which translates into a decrease in the sense of security and trust in modern technologies [

19].

For the above reasons, reconnaissance systems, even state-of-the-art ones based on advanced artificial intelligence algorithms, can lead to misidentifications and the resulting serious operational consequences. The solution to optimize the performance of such systems and increase their efficiency, especially in disturbed conditions, is to use super-resolution (SR) technology, whose main task is to increase the resolution without loss [

20]. However, modern SR algorithms, not only increase the resolution of analyzed images, but also, through the use of GAN architecture, enable simultaneous quality improvement.

The following work analyzes the effectiveness of the aircraft detection algorithm under simulated interference conditions, which were obtained by introducing appropriate artifacts, resulting from the most common interferences occurring in real systems. The impact of the application of the Real-ESRGAN algorithm on the efficiency and correctness of the detection model, both in the evaluation and training process, was analyzed.

The main contributions of the authors are as follows:

Review and taxonomy of super-resolution models based on neural networks.

Application of the super-resolution model in the detection of objects and analysis of its impact.

Conducting a series of experiments with different types of interference, under different scenarios.

Evaluate the impact of SR technology on the selected detection model, identify its limitations in a given application and define directions for further research.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: chapter 2 describes the super-resolution technology, with particular emphasis on the Real-ESRGAN model and examples of use in reconnaissance systems; chapter 3 presents the research methodology: the datasets used, the neural network models, the experiments conducted and a description of the test conditions; chapter 4 presents the results of individual experiments with visualizations; chapter 5 provides a discussion; chapter 6 summarizes the previous considerations and presents the planned directions for further research.

2. Super-Resolution in Imaging Systems

Super-resolution in images refers to the lossless increase in image resolution from low (LR) to high (HR). The idea behind SR algorithms is to reconstruct images to high resolution based on pixels and other information from the original image. The technology is used in many areas:

medical - for medical data, capturing high-resolution images can be difficult to achieve [

21]. Super resolution can be used as part of medical image preprocessing to increase the efficiency of diagnostic algorithms [

22,

23,

24,

25];

surveillance and security systems-The use of super-resolution in surveillance produces clearer camera images, allowing for greater accuracy in identifying people or vehicles in city surveillance systems, during event analysis, or in IoT systems [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30];

film and television industry - super-resolution allows to increase the resolution of material recorded at lower resolution and adapt it to current HD standards, it also facilitates the implementation of image and video watermarking algorithms [

31,

32,

33] and augmented reality (AR) [

34].

Modern super-resolution algorithms make it possible, not only to increase the resolution of images, but also to improve their visual quality by, among other things, reducing noise, sharpening, reconstructing missing elements [

35], which is particularly important in the context of optimizing military imaging reconnaissance systems.

2.1. Overwiev of Super-Resolution Algorithms

The first super-resolution methods were based on various interpolation techniques ( Nearest Neighbor Interpolation [

36], Bilinear Interpolation [

37], Bicubic Interpolation [

38]), frequency domain reconstruction [

39], statistical methods [

40,

41], multi-frame reconstruction [

42] with the availability of multiple images of the same object. The methods were characterized by rather poor quality, especially at high magnifications, and required large computational resources.

With the development of neural networks, algorithms began to emerge to produce high-resolution images with realistic details of comparable quality to the original images. The first solution was the SR-CNN model [

20] based on convolutional layers, in which the first layer was responsible for feature extraction, the second for nonlinear mapping, and the third for reconstruction to higher resolution. U An improvement on this architecture was the Very Deep Super Resolution (VDSR) model, which reduced the size of the convolution filters and used gradient clipping to optimize the learning process [

43].

To reduce the required computational power, the FSR-CNN solution was proposed, in which the preprocessing present in SR-CNN was abandoned, feature extraction was performed in low-resolution space, and reconstruction to high resolution is performed using deconvolution filters [

44].

Further solutions in this area were based on the use of different types of neural networks. Based on residual blocks, EDSR (enhanced deep super-resolution) and MDSR (multi-scale deep super-resolution) models were developed [

45], as well as CARN (Cascading residual network), which used a cascading mechanism to enable the network to process more information [

46]. Using recursive networks, models have been developed for DRCN (Deep Recursive Convolutional Network), which uses one and the same layer repeatedly instead of multiple convolutional layers to process features more deeply without adding more parameters [

47], and its improvement, DRRN (Deep Recursive Residual Network), where residual blocks are used instead of convolutional layers [

48].

To increase the scaling factor to eight times the resolution, progressive solutions have been used, which increase the resolution of images gradually (step-by-step). One such approach is LapSRN (Laplacian Pyramid Super-Resolution Network) [

49].

The breakthrough was the application of the attentional mechanism. In the SelNet (Selective Network) architecture, an additional selective unit was added to the convolutional blocks, which decides which processed features are most relevant and will allow efficient high-resolution image modeling [

50]. The RCAN (Residual Channel Attention Network) architecture, on the other hand, combines residual blocks with a channel-level attentional mechanism that allows to dynamically assign weights to different channels of image features, thus increasing the quality of reconstruction [

51].

The solutions described focus exclusively on optimizing pixel-level differences in LR and HR images. However, from the perspective of the human visual system, it is more important to optimize perceptual quality. This is how generative models work, which are very often used when transforming one image into another, but have been successfully applied to other types of signals as well [

52,

53,

54]. The first approach using a generative model to increase resolution was the SRGAN (Super-resolution Generative Adversarial Network) architecture, which, by using perceptual loss functions, made it possible to generate images with a more natural appearance, clear edges and details [

55]. On this basis, further models were developed such as: ESRGAN (Enhanced Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Network), where the perceptual loss function was improved [

56], Real-ESRGAN [

57], SRResNet, where residual blocks were introduced [

58], TSSRGAN (Two-Stage SRGAN), TSSRGAN (Two-Stage SRGAN), where the resolution enhancement process was divided into two stages to achieve greater stability and accuracy [

59].

A recent approach used in super-resolution models is vision transformers [

60], which were developed based on the popularity of traditional transformers. Using a large-scale attention mechanism allows not only to increase resolution, but also to remove noise and reduce blur. Recent developments of this type include Swin2SR using a Swin Transformer based on the concept of a sliding window transformer [

61], its improvement Swin2-MoSE [

62] and EpiMISR, which creates HR images based on multiple images containing complementary information [

63].

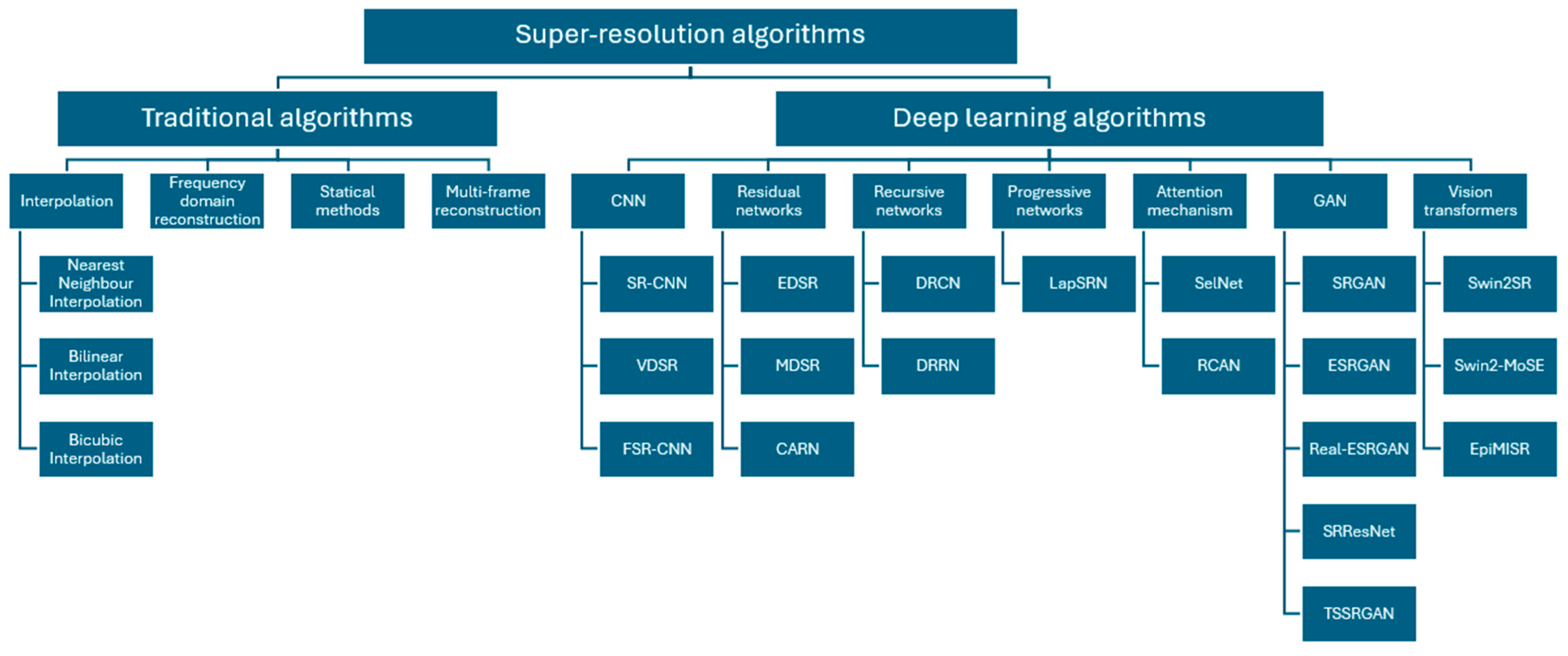

The following diagram shows the taxonomy of the super-resolution methods described above-

Figure 1.

2.2. Real-ESRGAN Model

In the experimental part of the article, the Real-ESRGAN (Real-World Enhanced Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Network) model was used to increase the resolution and improve the quality of data distorted with artifacts typical of real-world conditions. This choice was based on the versatile capabilities of the model, which was specifically adapted to low-quality data and operational conditions often encountered in real-world video systems.

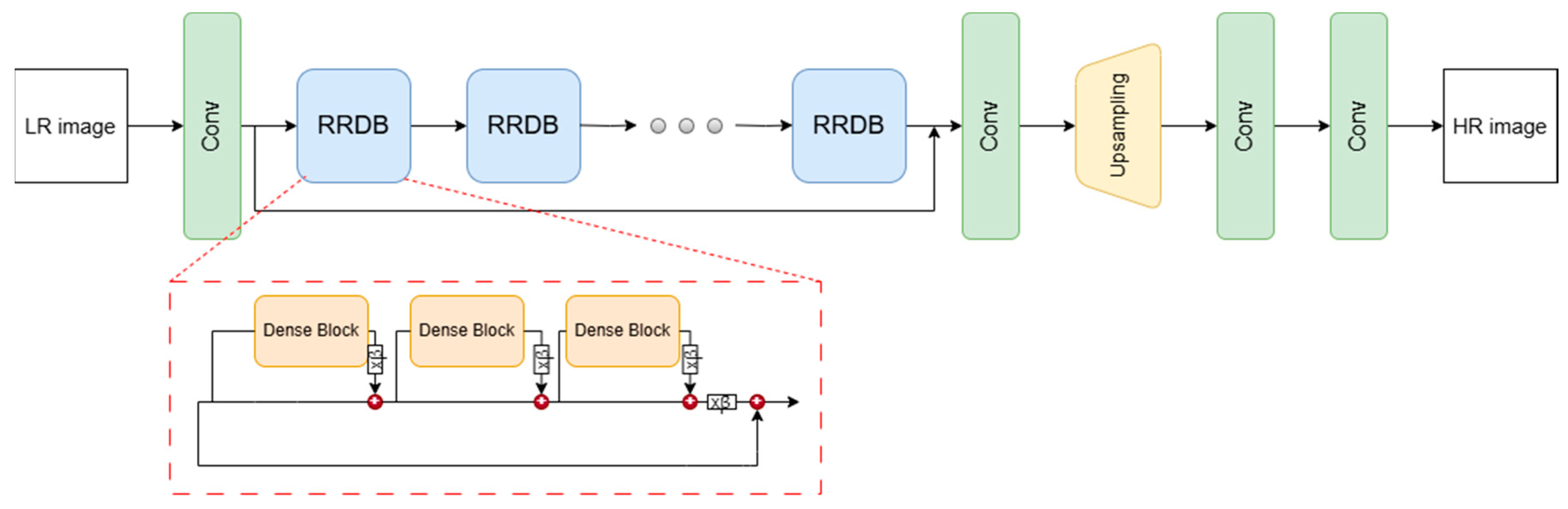

Real-ESRGAN was developed on the basis of ESRGAN, but the model was adapted to process real data, which may be noisy, distorted by compression, blurred, and contain other artifacts due to atmospheric conditions or image capture technology. The basis of the model's architecture -

Figure 2 - is RRDB (Residual-in-Residual Dense Block), which introduces hierarchical residual connections. This enables accurate modeling of image details while minimizing the effect of smoothing, which is crucial for reconstructing details in images with high levels of noise and noise. In addition, an enhanced perceptual loss function, which evaluates the image based on features relevant to human perception, and generative loss functions were used to increase the sharpness and detail of the final image. The versatility of Real-ESRGAN, which successfully processes data from a variety of low-quality sources, makes it widely used in surveillance and security applications [

64].

Real-ESRGAN was selected for further experimentation because of its ability to reconstruct detail in distorted images and its ability to reduce noise. This is crucial for image analysis in systems, where the quality of input data is limited.

2.3. Related Works

Super-resolution is a very popular technique in imagery reconnaissance, where detailed visual data is crucial, especially with satellite or drone imagery. High resolution allows for more precise situational analysis and supports decision-making.

SR is most often used in systems where images come from satellites or drones. The data is recorded from a high altitude, often under adverse weather conditions. The paper [

65] presented the MAGiGAN system, used in a satellite system for MISR (Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer) images, enabling a 3.75-fold increase in resolution while maintaining data quality. Similarly, the SRGAN-MSAM-DRC model [

66]. It is a generative model with a multi-scale attention mechanism and residual blocks, which allows it to catch subtle details in remote sensing images that feature complex spatial arrangements. Super-resolution technology, using various neural network models, positively influences the quality of satellite images after increasing their resolution, which is also confirmed by the following works [

67,

68,

69,

70]. SR is also used to process images from radar and thermal cameras, which are very often noisy, as shown in the works [

71,

72,

73,

74,

75].

In environments, where interference can significantly hinder object detection, the role of visual enhancement is particularly important [

76]. For example, in [

77] the use of super-resolution with adaptive regularization based on MG-MRF (Multi-Grid Markov Random Field) was proposed to aid the detection of point objects in infrared images. In another paper [

78], the authors proposed an algorithm based on the YOLO-SR architecture with data preprocessing to facilitate the detection of small targets in remote sensing images, while in [

79] a system with a generative model, attention mechanism and convolutional layers for infrared images is presented.

In summary, super-resolution techniques are a crucial element in imaging systems, enhancing the quality of visual data even under challenging interference conditions [

80,

81].

3. Methodology

3.1. Military Aircraft Recognition Dataset

The

Military Aircraft Recognition dataset imported from the Kaggle platform [

82] was used for the research in the following work. This is a dataset of satellite images depicting different types of military aircraft, dedicated to object detection. The set consists of 3842 images in which 22341 instances of objects belonging to 20 different classes were detected along with annotations. For implementation reasons, the annotation file was converted from Pascal VOC format [

83] to COCO format [

84] and adapted to the requirements of the detection algorithm used. In the COCO format, the annotations are stored as a JSON file, which consists of the following sections:

info - contains basic information about the dataset, such as creation date, authors, etc.;

images - is a list of JSON objects, containing metadata about each image in the dataset; annotations - is also a list of objects containing key data about each instance in the dataset, categories - a list of all object classes. The annotations define, among other things, the coordinates of the bounding boxes. Due to the requirements of the detection model, the coordinates remained in the format (

xmin, ymin, xmax, ymax), which refer to the position in the image expressed in pixels.

The figure below shows an example of images from the dataset, with the bounding boxes and class identifiers highlighted –

Figure 3.

Most of the images are 800x800 pixels. The images are characterized by different perspectives, lighting levels, surroundings and visual quality. The marked objects vary in size, some are independent objects, some are part of groups. Usually several objects can be observed in the images, representing at least two classes. Such a selection of data allows to reflect real detection challenges.

In order to ensure effective model training and evaluation, the collection was divided into three parts: training, validation and test, with a ratio of 70:20:10.

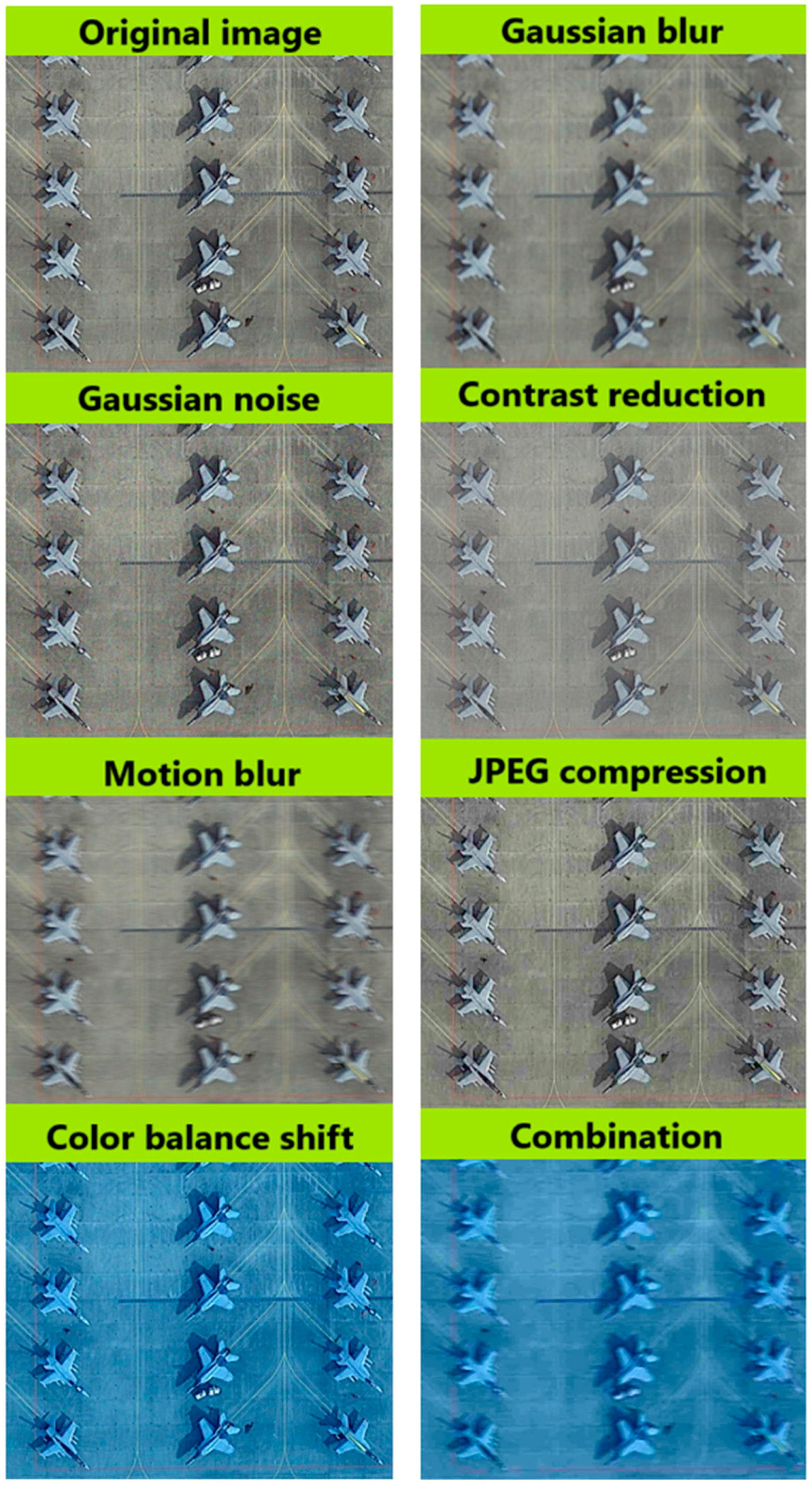

For further experiments, 7 additional subsets were created, based on images from the test set, in which selected distortions and artifacts were introduced to realistically reflect conditions encountered in real applications, such as aerial reconnaissance. The following types of distortions were used:

Gaussian blur which allows to simulate the effect of camera movement, which often occurs in aerial images taken from high altitudes, as small camera vibrations or vehicle movement affect image sharpness.

Gaussian noise reflects interference from sensors or distortion that occurs during data transmission, which is common in long-distance monitoring systems.

Contrast reduction was used to simulate low-light conditions or the presence of fog, which affect the visibility of details.

Motion blur is used to simulate a situation in which a drone or aircraft moves while taking a picture. In this case, the blur follows the direction of motion, making the edges of objects far less distinct.

JPEG compression artifacts, which is one of the most widely used image compression processes, but depending on the degree of compression can introduce visible artifacts such as pixel blocks or loss of detail, which makes detection especially difficult, especially for small objects.

Changing the color balance can simulate problems caused by incorrect camera calibration or varying atmospheric conditions, such as different light intensities. Problems with color balance can affect object recognition by causing unnatural coloring or tonality in the image.

The effects of applying the distortions mentioned are shown below for a selected image from the dataset –

Figure 4.

3.2. Implementation and Application of SN Models

3.2.1. Detection Model

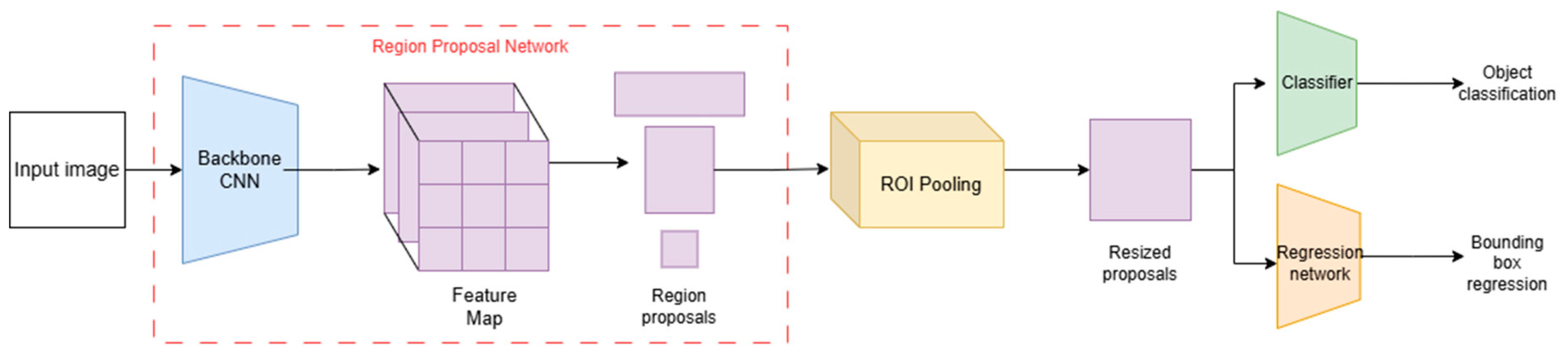

In image recognition systems, detection models play a key role, which enable precise localization and classification of objects in recorded images. In the present study, the Faster R-CNN (Region-based Convolutional Neural Network) model [

85] was selected as the base algorithm, whose efficiency and effectiveness were analyzed in detail.

The model represents an improved version of its precursors: R-CNN [

86] and Fast R-CNN [

87] in terms of speed of operation and detection accuracy. The main components of its architecture are:

Region Proposal Network (RPN) - a convolutional network responsible for generating potential regions of interest in feature maps..

ROI Pooling (Region of Interest Pooling) – a mechanism that transforms potential regions of interest to a uniform size.

The final part of the architecture is a classifier based on fully-connected layers and a regression layer that predicts the exact values of bounding box coordinates. A diagram of the model architecture is shown in the

Figure 5.

In this study, an implementation was used in which the underlying convolutional network is the ResNet-50 model [

90], and model training was performed using the COCO (Common Object in Context) dataset [

84]. Fine-tuning was performed for the model using the Military Aircraft Recognition dataset. The following hyperparameters were assumed during training:

number of epochs – 50,

optimizer – SGD with lr = 0.005, momentum = 0.9, weight decay = 0.0005,

batch size – train batch size = 4, validation batch size = 2.

After increasing the resolution of the training data, training of the detection model was conducted again. The training was terminated early due to the significantly increased processing time of the higher resolution data and the lack of further improvement in the metrics, indicating that a stable level of model performance had been achieved.

3.2.2. Super-Resolution Model

The study used the Real-ESRGAN model to four times increase the resolution of both the training data and additional subsets with introduced interference. To keep the results consistent, the coordinates of the bounding boxes, stored in the annotation file, were also scaled according to the increased resolution.

3.3. Description of Experimental Stages

The following experiments were conducted as part of the study:

Training and evaluation of the detection model on the original training dataset. The detection model was trained and tested on the original data without any additional modifications or distortions. The purpose of this stage was to obtain reference values for detection metrics, which serve as a baseline for assessing the impact of subsequent image modifications.

Implementation of artifacts and distortions in test images and conducting detection. Artifacts were applied to the original test images as described earlier. Object detection was then performed using the model trained in the first step. The results were compared with the reference results to evaluate how distortions affect the performance of the detection model.

Enhancing resolution and improving quality of distorted images. A super-resolution model was applied to increase the resolution and improve the visual quality of distorted images. After image reconstruction, detection was performed again using the model from the first step. The results were compared with earlier results on images without quality improvement and with the reference values to assess whether the super-resolution technique enhanced the detection model's performance under challenging conditions..

Increasing the resolution of the original dataset and retraining the detection model. The original training images were processed using the super-resolution model to enhance their resolution. Subsequently, the Faster R-CNN model underwent fine-tuning, resulting in a new detection model. The results of the newly trained model were compared with those obtained by the baseline model from the first step to determine how higher image resolution impacts detection accuracy during the model training phase.

Detection on Distorted and Restored Images Using the New Detection Model. In the final experiment, the model trained on high-resolution images (from the fourth step) was tested on distorted test images and on distorted images restored using super-resolution. The goal was to compare detection results for both sets of images—distorted and reconstructed—using the new model. This allowed for evaluating how a model adapted to high-resolution, high-quality images performs in detecting objects under distorted and restored conditions and the impact of image reconstruction on detection effectiveness.

3.4. Experimental Conditions and Metrics

The experiments were conducted locally on a laptop running Windows 11, equipped with an Intel Core i9-13980HX processor operating at 2.2 GHz with 24 cores, ensuring fast data processing. GPU acceleration was utilized with CUDA 12.6, supporting an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 graphics card with 16 GB of memory, enabling efficient model training and evaluation. The implementation and training of models were conducted using the PyTorch 2.5 framework, along with the following key libraries: NumPy 1.26.3, OpenCV 4.10.0.84 (preprocessing and data manipulation), pycocotools 2.0.8 (annotation management and evaluation metrics), matplotlib 3.9.2 (data visualization).

To accurately evaluate the effectiveness of the object detection model, key evaluation metrics were employed, allowing for a comprehensive analysis of results:

Precision - The ratio of correctly detected objects of a given class to all detected objects. A high precision value indicates a low number of false detections, which translates to minimizing false alarms.

Recall - The ratio of correctly detected objects of a given class to all objects of that class that the model should have detected. A high recall value signifies that the model successfully detects most objects, which is crucial in applications such as security systems.

mAP (Mean Average Precision) – This metric represents the mean of the Average Precision (AP) values calculated for each class. AP measures the area under the precision-recall curve, computed individually for each class at various levels of the IoU (Intersection over Union) parameter. IoU indicates the extent to which the predicted detection area overlaps with the actual area. This metric accounts for both precision and recall, enabling a holistic assessment of the model's performance.

4. Results

The following section presents the results of individual experiments conducted in accordance with the methodology described in the previous section.

4.1. Training and Evaluation of the Reference Model

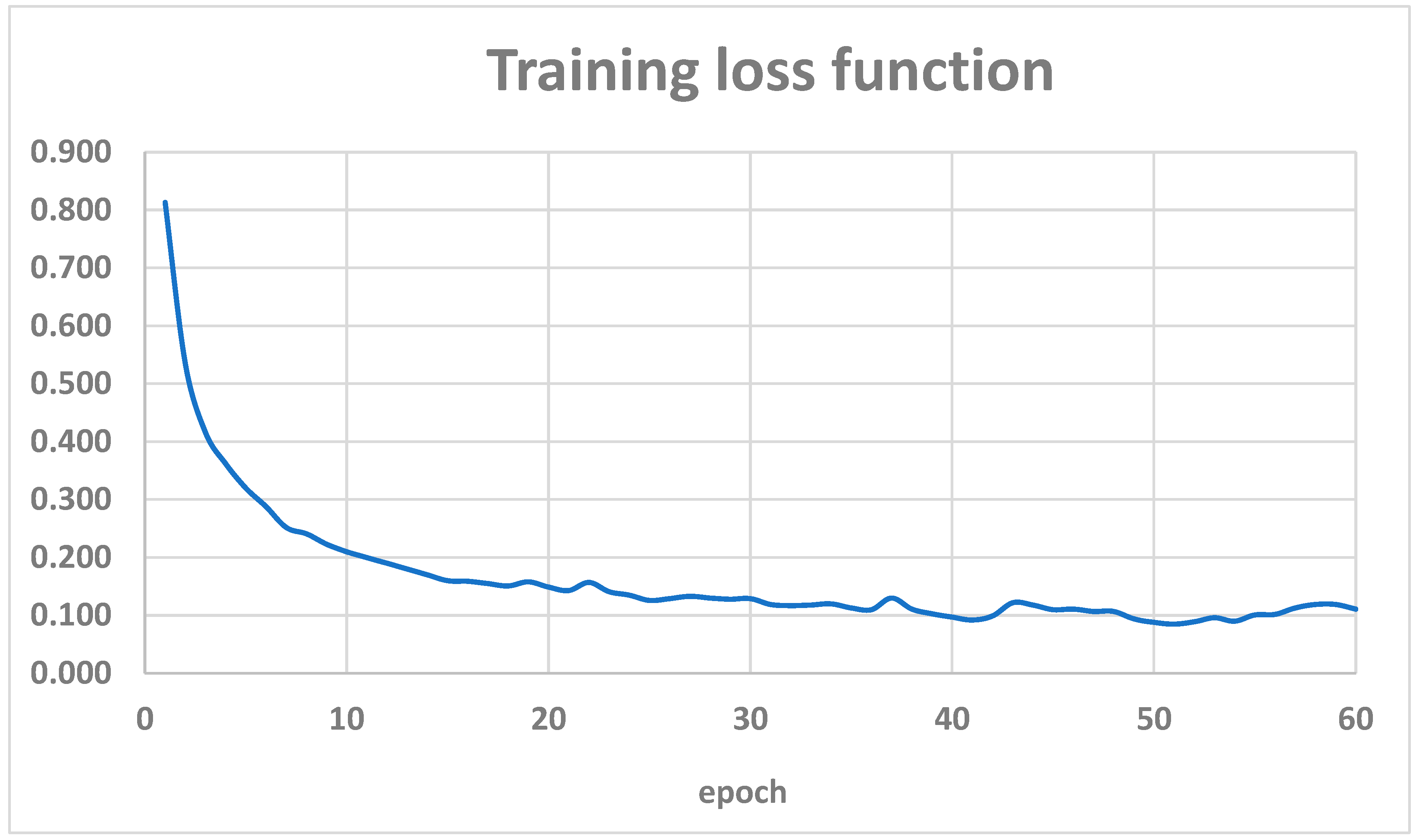

During the fine-tuning of the model, the efficiency of the training process was monitored based on the loss function values for the training data and the metrics values of precision, recall, and mAP for the validation data. The trends of these parameters are illustrated in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. A summary of the metrics values for the test set is presented in

Table 1, while a detailed interpretation of the mAP metric, including Average Precision and Average Recall for various object sizes, the number of detections per image, and IoU thresholds, is provided in

Table 2. Additionally, the figures illustrate example results of the detection model's performance on selected images from the test set -

Figure 8 and

Figure 9.

The results for the reference model indicate high effectiveness in object detection tasks, particularly for medium-sized objects (mAP = 0.755) and large objects (AR = 0.904). However, the model demonstrates lower precision (0.630) compared to recall (0.847), suggesting a higher number of false positives. The model provides a solid foundation for further experiments aimed at improving detection quality through super-resolution techniques.

4.2. Evaluation of Distorted Images

After implementing distortions into the images, the model was evaluated for each subset of data. The values of the obtained detection metrics are presented in illustrates the influence of distortions on the performance of the detection model.

Table 3. Additionally, for distortions with the smallest impact (Contrast reduction) and the largest impact (Motion blur) on detection performance, a detailed interpretation of the mAP metric is provided in

Table 4 and

Table 5. Na

Figure 10 illustrates the influence of distortions on the performance of the detection model.

The research results demonstrate a significant impact of the type of distortion on the system's performance. The smallest decrease in mAP was observed with contrast reduction (a drop to 0.583), suggesting that the model is relatively resistant to this type of distortion. In contrast, the largest drop in mAP occurred with motion blur, where the mAP value fell to just 0.236. Contrast reduction mainly resulted in the loss of some details but did not prevent the model from detecting object boundaries. Motion blur, on the other hand, significantly deteriorated detection results (

Figure 10), as it substantially reduced the clarity of object boundaries, leading to difficulties in detecting actual objects (low recall value) and their accurate classification (low precision value).

4.3. Evaluation of Images After Applying Super-Resolution

After applying the super-resolution model to distorted images, the model was re-evaluated for each data subset. The detection metric values obtained are presented in

Table 6.

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 illustrate the impact of using the super-resolution model on the detection model's performance for selected examples.

The research demonstrated that applying the Real-ESRGAN model improved detection efficiency for all restored subsets, except for images affected by motion blur. The model could not sufficiently sharpen the images to enhance the visibility of key features and contours. For restored images distorted by contrast reduction, a recall value slightly higher than that of the original, undistorted dataset was achieved.

4.4. Training and Evaluation the Model Using the Resolution-Improved Data

After applying the super-resolution model to the training dataset, fine-tuning was performed, resulting in a new detection model.

Figure 13 compares the loss function trends during the training phase for both models, while

Table 7 presents the detection metrics for the test set. Additionally,

Table 8 provides a detailed interpretation of the mAP metric.

After fine-tuning the new model using the high-resolution data, a significant improvement in performance was observed compared to the reference model. The precision metric for the test dataset increased from 0.630 to 0.744, while the recall value slightly decreased to 0.840. This ultimately resulted in an mAP increase to 0.701, confirming the model's overall improved accuracy.

A detailed analysis of the metrics shows that the SR model achieves an Average Precision (AP) of 0.744 at an IoU threshold of 0.50, demonstrating its capability for effective detection under lower localization accuracy requirements. For more stringent thresholds (IoU = 0.75), the AP is 0.743, indicating the model's stability across various scenarios.

4.5. Evaluation of Distorted and Restored Images

The new model was evaluated on distorted and restored images using the super-resolution algorithm. The evaluation metric values obtained are presented in

Table 9.

Similar to the reference model, the introduction of distortions to the images reduced detection performance across all subsets. However, applying the super-resolution model during image preprocessing improved performance. No improvement was achieved for motion blur distortions or the combination of multiple distortions. In most cases, slightly lower recall values were observed compared to the analogous cases evaluated by the original model. However, significantly higher precision and ultimately higher mAP values were achieved. This suggests a potential trade-off between the model's sensitivity and precision, which may be acceptable—or even desirable—in applications that require high precision.

5. Discussion

This section presents an analysis of the results obtained from the conducted experiments, considering their significance in the context of practical applications in object detection systems.

5.1. Limitations of the Model

The implementation of the super-resolution model (Real-ESRGAN) used in the study was unable to improve results for motion blur distortions or for a combination of distortions that included motion blur. This type of distortion significantly alters edges and detailed features of objects, which are critical for the performance of detection models. While super-resolution enhances the visual quality of an image, it may fail to faithfully reconstruct missing details in cases of extreme blur. In such instances, the SR model may amplify distorted or erroneous patterns caused by blur, leading the detection model to interpret them as incorrect shapes and completely ignore such objects.

In the case of combined distortions, the model must address multidimensional problems that are more challenging to reconstruct than single distortions. Super-resolution models perform best with distinct distortions that can be reduced, such as noise or low resolution. For multiple distortions, SR can generate additional artifacts or erroneous details that degrade the detection model's performance, resulting in extremely low metric values.

In such cases, combining SR methods with traditional image enhancement techniques, such as filtering, or additional fine-tuning of the SR model specifically for certain distortions—such as motion blur—may prove effective.

5.2. Super-Resolution a Augmentacja Danych

The research raises the question of whether a simpler solution might involve using data augmentation with selected distortions during the training of the detection model, enabling the model to learn how to localize and recognize objects affected by specific artifacts..

Data augmentation is a widely used technique in machine learning that artificially increases the size of the training dataset by introducing selected transformations and modifications to images. Despite incorporating similar modifications, augmentation and super-resolution have different goals and effects on model performance..

Augmentation introduces artifacts in a non-standard way that does not reflect real operational conditions. The generated data are often unnatural, meaning that instead of teaching the model to handle specific types of distortions, it can lead to degraded model performance due to generalization issues, ultimately resulting in lower effectiveness when analyzing real-world data.

Moreover, augmentation does not improve image quality; the modifications introduced are random and aim to increase data diversity. In extreme cases, excessive data diversity can also be undesirable, as it makes it more difficult for the model to learn patterns. This is particularly problematic in complex operational conditions, leading to reduced model efficiency.

6. Summary

The conducted research demonstrated that the application of super-resolution technology, specifically the generative Real-ESRGAN model, significantly enhances object detection performance in image reconnaissance systems. The increase in mAP and precision in most scenarios confirmed that improving the quality and resolution of input data is critical for object detection tasks, especially under challenging conditions such as noise or lossy compression. However, the analysis also highlighted the limitations of this technology, particularly in the case of motion blur and complex combinations of distortions, where the effects of SR were less pronounced or even detrimental to detection performance. The increase in detection precision, at the cost of a minimal decrease in recall observed during the fine-tuning of the second model, is advantageous in applications where minimizing false alarms and ensuring precise detection are critical.

Proposed directions for future research:

Further improvement of super-resolution models, particularly in handling extreme distortions such as motion blur and complex combinations of distortions characteristic of real-world conditions.

Combining super-resolution with other image processing techniques, such as adaptive noise-reduction filters.

Investigating the integration of super-resolution with advanced detection algorithms, such as models incorporating attention mechanisms.

Developing lightweight SR models optimized for real-time applications, especially in resource-constrained environments.

This research provides a solid foundation for the continued development of super-resolution technology in the context of image reconnaissance systems while highlighting areas requiring further optimization and exploration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Zbigniew Piotrowski and Marta Bistroń; methodology, Marta Bistroń, and Zbigniew Piotrowski; supervision, Zbigniew Piotrowski; validation, Zbigniew Piotrowski; writing—original draft preparation, Marta Bistroń; software, Marta Bistroń; formal analysis, Marta Bistroń; writing—review and editing, Zbigniew Piotrowski; visualization, Marta Bistroń; funding acquisition, Zbigniew Piotrowski. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Military University of Technology, Faculty of Electronics, grant number UGB/22-747 on Application of artificial intelligence methods to cognitive spectral analysis, satellite communications and watermarking and technology Deepfake. The grant is dedicated to supporting a wide range of scientific research projects conducted by the university's academic teams, covering both military and civilian applications, with a focus on advancing artificial intelligence and signal processing technologies for interdisciplinary use.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in a publicly accessible repository: Military Aircraft Recognition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sutherland, B. Modern Warfare, Intelligence and Deterrence: The Technology That Is Transforming Them; Profile Books.

- Butt, M.A.; Voronkov, G.S.; Grakhova, E.P.; Kutluyarov, R.V.; Kazanskiy, N.L.; Khonina, S.N. Environmental Monitoring: A Comprehensive Review on Optical Waveguide and Fiber-Based Sensors. Biosensors (Basel) 2022, 12, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, W.W.; Lynch, J.P.; Zekkos, D. Applications of UAVs in Civil Infrastructure. Journal of Infrastructure Systems 2019, 25, 04019002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitaritonna, A.; Abásolo, M.J. Improving Situational Awareness in Military Operations Using Augmented Reality. 2015.

- Munir, A.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Anwar, S.; El-Maleh, A.; Khan, A.H.; Rehman, A. Impact of Adverse Weather and Image Distortions on Vision-Based UAV Detection: A Performance Evaluation of Deep Learning Models. Drones 2024, 8, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eso, E.; Burton, A.; Hassan, N.B.; Abadi, M.M.; Ghassemlooy, Z.; Zvanovec, S. Experimental Investigation of the Effects of Fog on Optical Camera-Based VLC for a Vehicular Environment. In 2019 15th International Conference on Telecommunications (Con℡); 2019; pp 1–5. [CrossRef]

- White, A. Camouflage and Concealment. Asian Military Review. https://www.asianmilitaryreview.com/2024/06/camouflage-and-concealment/ (accessed 2024-11-08).

- Dobija, K. Countering Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS) in Military Operations. Safety & Defense 2023, 9, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosek-Szott, K.; Natkaniec, M.; Prasnal, L. IEEE 802.11aa Intra-AC Prioritization - A New Method of Increasing the Granularity of Traffic Prioritization in WLANs. In 2014 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC); 2014; pp 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Dai, R. Object-Detection-Based Video Compression for Wireless Surveillance Systems. IEEE MultiMedia 2017, 24, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Byrne, M. ; Vibhoothi; Sugrue, M.; Kokaram, A. Impact of Video Compression on the Performance of Object Detection Systems for Surveillance Applications. arXiv , 2022. 10 November. [CrossRef]

- Sieberth, T.; Wackrow, R.; Chandler, J.H. UAV IMAGE BLUR - ITS INFLUENCE AND WAYS TO CORRECT IT. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2015, XL-1-W4, 33–39. [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.-X.; Gui, D.-Z.; Li, Z. Research on Image Motion Blur for Low Altitude Remote Sensing. Information Technology Journal 2013, 12, 7096–7100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratches, J.A. Review of Current Aided/Automatic Target Acquisition Technology for Military Target Acquisition Tasks. OE 2011, 50, 072001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldschmidt, P. Managing the False Alarms: A Framework for Assurance and Verification of Surveillance Monitoring. Inf Syst Front 2007, 9, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žigulić, N.; Glučina, M.; Lorencin, I.; Matika, D. Military Decision-Making Process Enhanced by Image Detection. Information 2024, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebber, R.J. Treating Information as a Strategic Resource to Win the “Information War. ” Orbis 2017, 61, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iran Air flight 655 | Background, Events, Investigation, & Facts | Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Iran-Air-flight-, 2024.

- Bistron, M.; Piotrowski, Z. Artificial Intelligence Applications in Military Systems and Their Influence on Sense of Security of Citizens. Electronics 2021, 10, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Loy, C.C.; He, K.; Tang, X. Image Super-Resolution Using Deep Convolutional Networks. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2016, 38, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenspan, H. Super-Resolution in Medical Imaging. The Computer Journal 2009, 52, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kumbharkar, P.; Vanam, S.; Sharma, S. Medical Images Classification Using Deep Learning: A Survey | Multimedia Tools and Applications. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024, 83, 19683–19728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.D.; Saleem, A.; Elahi, H.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, M.I.; Yaqoob, M.M.; Farooq Khattak, U.; Al-Rasheed, A. Breast Cancer Classification through Meta-Learning Ensemble Technique Using Convolution Neural Networks. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bistroń, M.; Piotrowski, Z. Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms Used for Skin Cancer Diagnosis. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 9960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechelli, S.; Delhommelle, J. Machine Learning and Deep Learning Algorithms for Skin Cancer Classification from Dermoscopic Images. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chacua, B.; García, I.; Rosero, P.; Suárez, L.; Ramírez, I.; Simbaña, Z.; Pusda, M. People Identification through Facial Recognition Using Deep Learning. In 2019 IEEE Latin American Conference on Computational Intelligence (LA-CCI); 2019; pp 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Mavrokapnidis, D.; Mohammadi, N.; Taylor, J. Community Dynamics in Smart City Digital Twins: A Computer Vision-Based Approach for Monitoring and Forecasting Collective Urban Hazard Exposure; 2021.

- Tippannavar, S.S.; D, Y.S. Real-Time Vehicle Identification for Improving the Traffic Management System-A Review. Journal of Trends in Computer Science and Smart Technology 2023, 5, 323–342. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Deng, R.; Cheng, Y.; Hu, R.; Shen, K. Research on Vehicle Detection and Recognition Based on Infrared Image and Feature Extraction. Mobile Information Systems 2022, 2022, 6154614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czeczot, G.; Rojek, I.; Mikołajewski, D.; Sangho, B. AI in IIoT Management of Cybersecurity for Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0 Purposes. Electronics 2023, 12, 3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenarczyk, P.; Piotrowski, Z. Parallel Blind Digital Image Watermarking in Spatial and Frequency Domains. Telecommun Syst 2013, 54, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Das, A.; Alrasheedi, F.; Tanvir, A. A Brief, In-Depth Survey of Deep Learning-Based Image Watermarking. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 11852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bistroń, M.; Piotrowski, Z. Efficient Video Watermarking Algorithm Based on Convolutional Neural Networks with Entropy-Based Information Mapper. Entropy 2023, 25, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagran-Vizcarra, D.C.; Luviano-Cruz, D.; Pérez-Domínguez, L.A.; Méndez-González, L.C.; Garcia-Luna, F. Applications Analyses, Challenges and Development of Augmented Reality in Education, Industry, Marketing, Medicine, and Entertainment. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Y.; Wang, W.; Xue, J.-H. Deep Learning for Single Image Super-Resolution: A Brief Review. arXiv , 2019. 12 July. [CrossRef]

- Rukundo, O.; Cao, H. Nearest Neighbor Value Interpolation. arXiv , 2019. 4 March. [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, E.J. Bilinear Interpolation. In Advanced Computing in Electron Microscopy; Kirkland, E.J., Ed.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Dai, Y.; Han, K.; Wang, J.; Hu, J. An Efficient Bicubic Interpolation Implementation for Real-Time Image Processing Using Hybrid Computing. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2022, 19, 1211–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Paulsen, K.D.; Osterberg, U.L.; Pogue, B.W.; Patterson, M.S. Optical Image Reconstruction Using Frequency-Domain Data: Simulations and Experiments. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A, JOSAA 1996, 13, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, M.; Fessler, J.A. Statistical Image Reconstruction Methods for Randoms-Precorrected PET Scans. Medical Image Analysis 1998, 2, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoncelli, E.P. Statistical Models for Images: Compression, Restoration and Synthesis; IEEE Computer Society, 1997; p 673- 678. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hu, Y.; Gao, X.; Tao, D.; Ning, B. A Multi-Frame Image Super-Resolution Method. Signal Processing 2010, 90, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, K.M. Accurate Image Super-Resolution Using Very Deep Convolutional Networks. arXiv , 2016. 11 November. [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Loy, C.C.; Tang, X. Accelerating the Super-Resolution Convolutional Neural Network. arXiv , 2016. 1 August. [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.; Son, S.; Kim, H.; Nah, S.; Lee, K.M. Enhanced Deep Residual Networks for Single Image Super-Resolution. In 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); IEEE: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, N.; Kang, B.; Sohn, K.-A. Fast, Accurate, and Lightweight Super-Resolution with Cascading Residual Network. arXiv , 2018. 4 October. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, K.M. Deeply-Recursive Convolutional Network for Image Super-Resolution. arXiv , 2016. 11 November. [CrossRef]

- Tai, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, X. Image Super-Resolution via Deep Recursive Residual Network. In 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017; pp 2790–2798. [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.-S.; Huang, J.-B.; Ahuja, N.; Yang, M.-H. Fast and Accurate Image Super-Resolution with Deep Laplacian Pyramid Networks. arXiv , 2018. 9 August. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Shi, J. Lightweight Image Super-Resolution with Adaptive Weighted Learning Network. arXiv , 2019. 4 April. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Li, K.; Wang, L.; Zhong, B.; Fu, Y. Image Super-Resolution Using Very Deep Residual Channel Attention Networks. arXiv , 2018. 12 July. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xie, L.; Qi, K. Implement Music Generation with GAN: A Systematic Review. In 2021 International Conference on Computer Engineering and Application (ICCEA); 2021; pp 352–355. [CrossRef]

- Walczyna, T.; Piotrowski, Z. Overview of Voice Conversion Methods Based on Deep Learning. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Lan, S.; Zachariah, A.G. EVA-GAN: Enhanced Various Audio Generation via Scalable Generative Adversarial Networks. arXiv , 2024. 31 January. [CrossRef]

- Ledig, C.; Theis, L.; Huszar, F.; Caballero, J.; Cunningham, A.; Acosta, A.; Aitken, A.; Tejani, A.; Totz, J.; Wang, Z.; Shi, W. Photo-Realistic Single Image Super-Resolution Using a Generative Adversarial Network. arXiv , 2017. 25 May. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, K.; Wu, S.; Gu, J.; Liu, Y.; Dong, C.; Loy, C.C.; Qiao, Y.; Tang, X. ESRGAN: Enhanced Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Networks. arXiv , 2018. 17 September. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xie, L.; Dong, C.; Shan, Y. Real-ESRGAN: Training Real-World Blind Super-Resolution with Pure Synthetic Data. arXiv , 2021. 17 August. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Song, S.-H. SRResNet Performance Enhancement Using Patch Inputs and Partial Convolution-Based Padding. Computers, Materials and Continua 2022, 74, 2999–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreini, P.; Bonechi, S.; Bianchini, M.; Mecocci, A.; Scarselli, F.; Sodi, A. A Two Stage GAN for High Resolution Retinal Image Generation and Segmentation. arXiv , 2019. 29 July. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Guo, T.; Xu, C.; Deng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Ma, S.; Xu, C.; Xu, C.; Gao, W. Pre-Trained Image Processing Transformer. arXiv , 2021. 8 November. [CrossRef]

- Conde, M.V.; Choi, U.-J.; Burchi, M.; Timofte, R. Swin2SR: SwinV2 Transformer for Compressed Image Super-Resolution and Restoration. arXiv , 2022. 22 September. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, L.; Bernuzzi, V.; Fontanini, T.; Bertozzi, M.; Prati, A. Swin2-MoSE: A New Single Image Super-Resolution Model for Remote Sensing. arXiv , 2024. 29 April. [CrossRef]

- Aira, L.S.; Valsesia, D.; Molini, A.B.; Fracastoro, G.; Magli, E.; Mirabile, A. Deep 3D World Models for Multi-Image Super-Resolution Beyond Optical Flow. arXiv , 2024. 30 January. [CrossRef]

- Çetin, Ş., B. Real-ESRGAN: A Deep Learning Approach for General Image Restoration and Its Application to Aerial Images. Advanced Remote Sensing 2023, 3, 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Y.; Muller, J.-P. Super-Resolution Restoration of MISR Images Using the UCL MAGiGAN System. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Ju, L.; Du, Y.; Li, Y. A Super-Resolution Reconstruction Model for Remote Sensing Image Based on Generative Adversarial Networks. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Guo, T.; Wang, C. A Remote Sensing Image Super-Resolution Reconstruction Model Combining Multiple Attention Mechanisms. Sensors 2024, 24, 4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, S. SUPER-RESOLUTION RESEARCH ON REMOTE SENSING IMAGES IN THE MEGACITY BASED ON IMPROVED SRGAN. ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2022, V-3–2022, 603–609. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; XU, G.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.; Lin, D.; WU, Y. High Quality Remote Sensing Image Super-Resolution Using Deep Memory Connected Network. In IGARSS 2018 - 2018 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium; 2018; pp 8889–8892. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Li, W.; Lei, S.; Chen, J.; Jiang, X.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z. Continuous Remote Sensing Image Super-Resolution Based on Context Interaction in Implicit Function Space. arXiv , 2023. 16 February. [CrossRef]

- Schuessler, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Vossiek, M. Super-Resolution Radar Imaging with Sparse Arrays Using a Deep Neural Network Trained with Enhanced Virtual Data. arXiv , 2023. 16 June. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Geng, H.; Wu, F.; Geng, L.; Zhuang, X. Radar-SR3: A Weather Radar Image Super-Resolution Generation Model Based on SR3. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Chun, J.; Song, S. Forward-Looking Super-Resolution Radar Imaging via Reweighted L1-Minimization. In 2018 IEEE Radar Conference (RadarConf18); 2018; pp 0453–0457. [CrossRef]

- Huo, W.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yang, J. A Superfast Super-Resolution Method for Radar Forward-Looking Imaging. Sensors 2021, 21, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.; Zeng, Q.; He, J. [Retracted] Weather Radar Image Superresolution Using a Nonlocal Residual Network. Journal of Mathematics 2021, 2021, 4483907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; He, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, G.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, Y. A Review of Intelligent Vision Enhancement Technology for Battlefield. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing 2023, 2023, 6733262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lin, Z.; Deng, X.; An, W. Point Target Detection Utilizing Super-Resolution Strategy for Infrared Scanning Oversampling System. Infrared Physics & Technology 2017, 86, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Luo, S.; Chen, M.; He, C.; Wang, T.; Wu, H. Infrared Small Target Detection with Super-Resolution and YOLO. Optics & Laser Technology 2024, 177, 111221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, J. Target Detection Algorithm Based on Super- Resolution Color Remote Sensing Image Reconstruction. Journal of Measurements in Engineering 2024, 12, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdaş, M.B.; Uysal, F.; Hardalaç, F. Super Resolution Image Acquisition for Object Detection in the Military Industry. In 2023 5th International Congress on Human-Computer Interaction, Optimization and Robotic Applications (HORA); 2023; pp 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Li, Y.; Shao, F.; Yuan, G.; Dai, J. Visual-Simulation Region Proposal and Generative Adversarial Network Based Ground Military Target Recognition. Defence Technology 2022, 18, 2083–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Military Aircraft Recognition dataset. https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/khlaifiabilel/military-aircraft-recognition-dataset (accessed 2024-11-12).

- Everingham, M.; Van Gool, L.; Williams, C.K.I.; Winn, J.; Zisserman, A. The Pascal Visual Object Classes (VOC) Challenge. Int J Comput Vis 2010, 88, 303–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. In Computer Vision – ECCV 2014; Fleet, D., Pajdla, T., Schiele, B., Tuytelaars, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. arXiv , 2016. 6 January. [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich Feature Hierarchies for Accurate Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation. arXiv , 2014. 22 October. [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. arXiv , 2015. 27 September. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, V.K. Faster R-CNN: Object Detection. The Deep Hub. https://medium.com/thedeephub/faster-r-cnn-object-detection-5dfe77104e31 (accessed 2024-11-13).

- Ananth, S. Faster R-CNN for object detection. Medium. https://towardsdatascience.com/faster-r-cnn-for-object-detection-a-technical-summary-474c5b857b46 (accessed 2024-11-13).

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. arXiv , 2015. 10 December. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Super-resolution algorithms taxonomy.

Figure 1.

Super-resolution algorithms taxonomy.

Figure 2.

Real-ESRGAN architecture [

57].

Figure 2.

Real-ESRGAN architecture [

57].

Figure 3.

Example images from the Military Aircraft Recognition dataset.

Figure 3.

Example images from the Military Aircraft Recognition dataset.

Figure 4.

Interference simulating real operational conditions in image reconnaissance systems.

Figure 4.

Interference simulating real operational conditions in image reconnaissance systems.

Figure 5.

Diagram of the Faster R-CNN architecture [

88,

89].

Figure 5.

Diagram of the Faster R-CNN architecture [

88,

89].

Figure 6.

The value of the loss function in the training phase.

Figure 6.

The value of the loss function in the training phase.

Figure 7.

The values of the detection evaluation metrics in the validation phase.

Figure 7.

The values of the detection evaluation metrics in the validation phase.

Figure 8.

Detection model result – example 1.

Figure 8.

Detection model result – example 1.

Figure 9.

Detection model result – example 2.

Figure 9.

Detection model result – example 2.

Figure 10.

The influence of distortions on the performance of the detection model.

Figure 10.

The influence of distortions on the performance of the detection model.

Figure 11.

The influence of the super-resolution algorithm on the detection model performance – contrast reduction.

Figure 11.

The influence of the super-resolution algorithm on the detection model performance – contrast reduction.

Figure 12.

The influence of the super-resolution algorithm on the detection model performance – motion blur.

Figure 12.

The influence of the super-resolution algorithm on the detection model performance – motion blur.

Figure 13.

Comparison of loss function values in the training phase.

Figure 13.

Comparison of loss function values in the training phase.

Table 1.

Values of evaluation metrics for the test set.

Table 1.

Values of evaluation metrics for the test set.

| Test recall |

Test precision |

Test mAP |

| 0.847 |

0.630 |

0.596 |

Table 2.

Summary of Average Precision and Average Recall for the test set.

Table 2.

Summary of Average Precision and Average Recall for the test set.

| |

IoU |

Objects size |

Max detection number |

Value |

Average Precision

Average Precision

Average Precision |

0.50:0.95 |

all |

100 |

0.596 |

| 0.50 |

all |

100 |

0.630 |

| 0.75 |

all |

100 |

0.630 |

| Average Precision |

0.50:0.95 |

small |

100 |

-1.000 |

Average Precision

|

0.50:0.95 |

medium |

100 |

0.755 |

Average Precision

|

0.50:0.95 |

large |

100 |

0.568 |

| Average Recall |

0.50:0.95 |

all |

1 |

0.341 |

| Average Recall |

0.50:0.95 |

all |

10 |

0.820 |

| Average Recall |

0.50:0.95 |

all |

100 |

0.847 |

Average Recall

Average Recall |

0.50:0.95 |

small |

100 |

-1.000 |

| 0.50:0.95 |

medium |

100 |

0.778 |

| Average Recall |

0.50:0.95 |

large |

100 |

0.904 |

Table 3.

Values of evaluation metrics for distorted sets.

Table 3.

Values of evaluation metrics for distorted sets.

| |

Test recall |

Test precision |

Test mAP |

| Reference results |

0.847 |

0.630 |

0.596 |

| Gaussian blur |

0.794 |

0.546 |

0.509 |

| Gaussian noise |

0.798 |

0.532 |

0.496 |

| Contrast reduction |

0.830 |

0.616 |

0.583 |

| Motion blur |

0.494 |

0.256 |

0.236 |

| JPEG compression |

0.812 |

0.555 |

0.519 |

| Color balance shift |

0.778 |

0.525 |

0.489 |

| Combination |

0.285 |

0.131 |

0.118 |

Table 4.

Summary of Average Precision and Average Recall for Contrast reduction distortion.

Table 4.

Summary of Average Precision and Average Recall for Contrast reduction distortion.

| |

IoU |

Objects size |

Max detection number |

Value |

Average Precision

Average Precision

Average Precision |

0.50:0.95 |

all |

100 |

0.583 |

| 0.50 |

all |

100 |

0.616 |

| 0.75 |

all |

100 |

0.616 |

| Average Precision |

0.50:0.95 |

small |

100 |

-1.000 |

| Average Precision |

0.50:0.95 |

medium |

100 |

0.746 |

| Average Precision |

0.50:0.95 |

large |

100 |

0.566 |

| Average Recall |

0.50:0.95 |

all |

1 |

0.333 |

| Average Recall |

0.50:0.95 |

all |

10 |

0.804 |

| Average Recall |

0.50:0.95 |

all |

100 |

0.830 |

Average Recall

Average Recall |

0.50:0.95 |

small |

100 |

-1.000 |

| 0.50:0.95 |

medium |

100 |

0.749 |

| Average Recall |

0.50:0.95 |

large |

100 |

0.912 |

Table 5.

Summary of Average Precision and Average Recall for Motion blur distortion.

Table 5.

Summary of Average Precision and Average Recall for Motion blur distortion.

| |

IoU |

Objects size |

Max detection number |

Value |

Average Precision

Average Precision

Average Precision |

0.50:0.95 |

all |

100 |

0.236 |

| 0.50 |

all |

100 |

0.256 |

| 0.75 |

all |

100 |

0.255 |

| Average Precision |

0.50:0.95 |

small |

100 |

-1.000 |

| Average Precision |

0.50:0.95 |

medium |

100 |

0.413 |

| Average Precision |

0.50:0.95 |

large |

100 |

0.339 |

| Average Recall |

0.50:0.95 |

all |

1 |

0.208 |

| Average Recall |

0.50:0.95 |

all |

10 |

0.492 |

| Average Recall |

0.50:0.95 |

all |

100 |

0.494 |

Average Recall

Average Recall |

0.50:0.95 |

small |

100 |

-1.000 |

| 0.50:0.95 |

medium |

100 |

0.411 |

| Average Recall |

0.50:0.95 |

large |

100 |

0.671 |

Table 6.

Values of evaluation metrics for restored sets.

Table 6.

Values of evaluation metrics for restored sets.

| |

Test recall |

Test precision |

Test mAP |

| Reference results |

0.847 |

0.630 |

0.596 |

| Gaussian blur |

0.794 |

0.546 |

0.509 |

| Gaussian blur SR |

0.825 |

0.560 |

0.521 |

| Gaussian noise |

0.798 |

0.532 |

0.496 |

| Gaussian noise SR |

0.831 |

0.590 |

0.553 |

| Contrast reduction |

0.830 |

0.616 |

0.583 |

| Contrast reduction SR |

0.854 |

0.591 |

0.555 |

| Motion blur |

0.494 |

0.256 |

0.236 |

| Motion blur SR |

0.416 |

0.193 |

0.172 |

| JPEG compression |

0.812 |

0.555 |

0.519 |

| JPEG compression SR |

0.838 |

0.575 |

0.534 |

| Color balance shift |

0.778 |

0.525 |

0.489 |

| Color balance shift SR |

0.801 |

0.530 |

0.496 |

| Combination |

0.285 |

0.131 |

0.118 |

| Combination SR |

0.256 |

0.115 |

0.101 |

Table 7.

Values of evaluation metrics for the test set for both models.

Table 7.

Values of evaluation metrics for the test set for both models.

| |

Test recall |

Test precision |

Test mAP |

| Original model |

0.847 |

0.630 |

0.596 |

| SR model |

0.840 |

0.744 |

0.701 |

Table 8.

Summary of Average Precision and Average Recall for the test set for model fine-tuned with restored data.

Table 8.

Summary of Average Precision and Average Recall for the test set for model fine-tuned with restored data.

| |

IoU |

Objects size |

Max detection number |

Value |

Average Precision

Average Precision

Average Precision |

0.50:0.95 |

all |

100 |

0.701 |

| 0.50 |

all |

100 |

0.744 |

| 0.75 |

all |

100 |

0.743 |

| Average Precision |

0.50:0.95 |

small |

100 |

-1.000 |

Average Precision

|

0.50:0.95 |

medium |

100 |

-1.000 |

Average Precision

|

0.50:0.95 |

large |

100 |

0.701 |

| Average Recall |

0.50:0.95 |

all |

1 |

0.333 |

| Average Recall |

0.50:0.95 |

all |

10 |

0.820 |

| Average Recall |

0.50:0.95 |

all |

100 |

0.840 |

Average Recall

Average Recall |

0.50:0.95 |

small |

100 |

-1.000 |

| 0.50:0.95 |

medium |

100 |

-1.000 |

| Average Recall |

0.50:0.95 |

large |

100 |

0.840 |

Table 9.

Values of evaluation metrics for distorted and restored sets.

Table 9.

Values of evaluation metrics for distorted and restored sets.

| |

Test recall |

Test precision |

Test mAP |

| SR model |

0.840 |

0.744 |

0.701 |

| Gaussian blur |

0.728 |

0.509 |

0.469 |

| Gaussian blur SR |

0.811 |

0.641 |

0.595 |

| Gaussian noise |

0.755 |

0.574 |

0.532 |

| Gaussian noise SR |

0.820 |

0.694 |

0.656 |

| Contrast reduction |

0.807 |

0.662 |

0.625 |

| Contrast reduction SR |

0.816 |

0.688 |

0.649 |

| Motion blur |

0.403 |

0.224 |

0.207 |

| Motion blur SR |

0.269 |

0.127 |

0.114 |

| JPEG compression |

0.777 |

0.602 |

0.560 |

| JPEG compression SR |

0.829 |

0.679 |

0.637 |

| Color balance shift |

0.809 |

0.650 |

0.612 |

| Color balance shift SR |

0.821 |

0.697 |

0.656 |

| Combination |

0.365 |

0.180 |

0.162 |

| Combination SR |

0.327 |

0.150 |

0.134 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).