Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Related Work

- Design a CrowdBA architecture for bounding box annotation using the Ethereum public blockchain as the underlying framework. By developing corresponding smart contracts and integrating the Ethereum public chain with the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS), we shift storage and computation off-chain, reducing the high costs associated with data storage and computation on the blockchain and improving scalability;

- Develop a DWBF algorithm based on Intersection over Union (IoU) for dynamically weighted bounding box fusion. This algorithm infers a true bounding box based on the annotations provided by workers, allowing for the evaluation of each worker's annotation quality. Annotation quality serves as a crucial factor for incentive allocation, ensuring fair reward distribution based on the accuracy of each worker’s contributions;

- Deploy the developed smart contracts on the Ethereum test network to assess the cost-effectiveness of each functional contract, validating the protocol’s practical feasibility. We also evaluate the accuracy of the DWBF algorithm, demonstrating its effectiveness in producing high-quality annotations.

2. Preliminary

2.1. Blockchain and Smart Contracts

2.2. Types of Blockchain

3. CrowdBA Architecture

3.1. Architecture Design

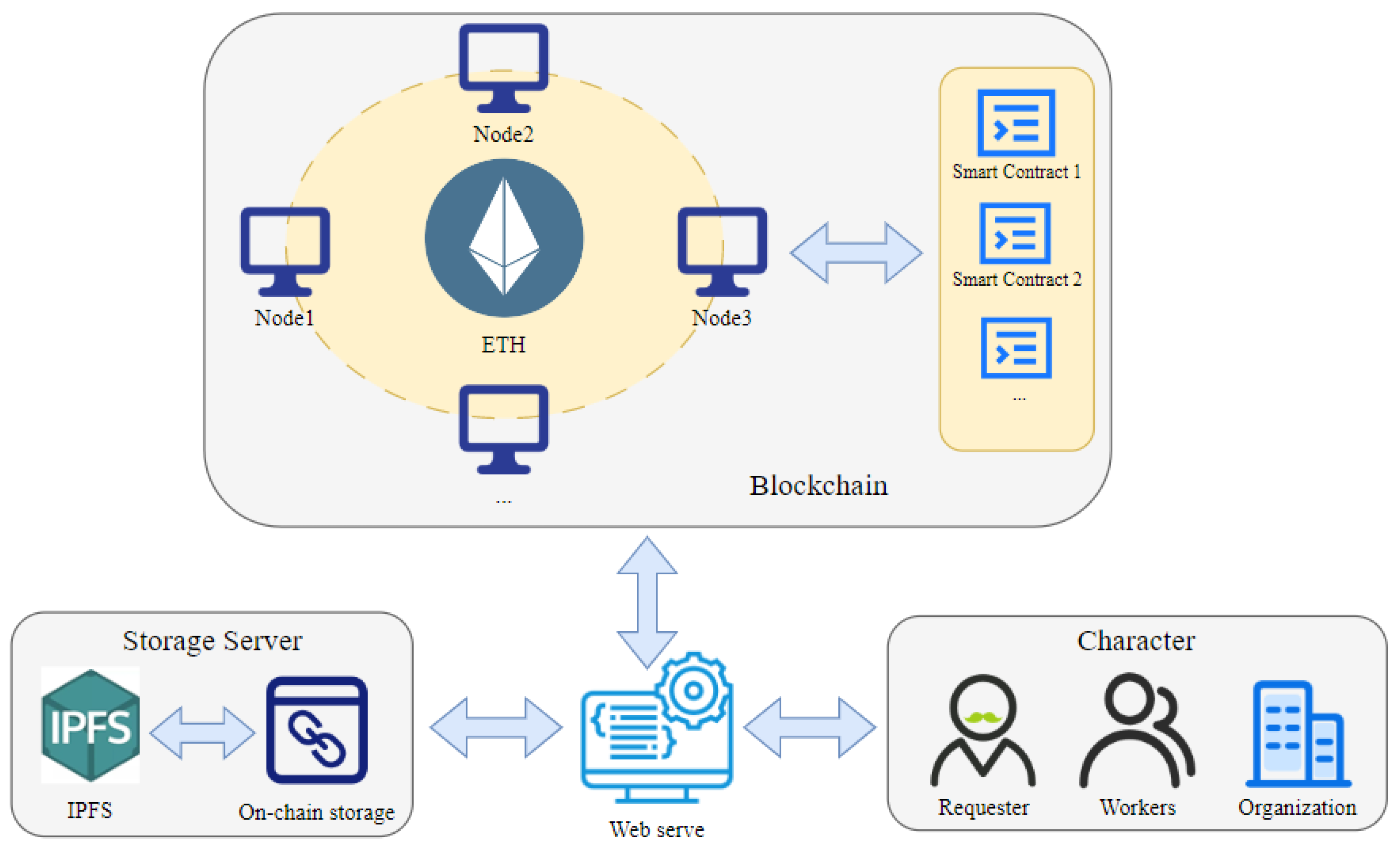

- Requester: Defined as the initiator of crowdsourcing tasks for bounding box annotation on the blockchain. Any user on the blockchain can post crowdsourcing tasks through CrowdBA, becoming a requester.

- Worker: Defined as the executor of crowdsourcing tasks for bounding box annotation on the blockchain. Users can claim appropriate tasks within the CrowdBA to perform annotations, receiving incentives provided by the requester in return.

- Storage Server: Composed of Ethereum and IPFS (InterPlanetary File System). IPFS is a distributed protocol for file storage, sharing, and retrieval. The system generates a content hash (CID, Content Identifier) for each data item through hash computation, which uniquely identifies the data within the IPFS network. Annotation tasks and results are stored and exchanged via IPFS, alleviating storage burdens on the blockchain.

- Smart Contract: The smart contract plays a pivotal role in ensuring algorithm transparency and automating incentive distribution. It is responsible for recording and verifying data, executing predefined incentive distribution rules, and managing the posting and acceptance of tasks.

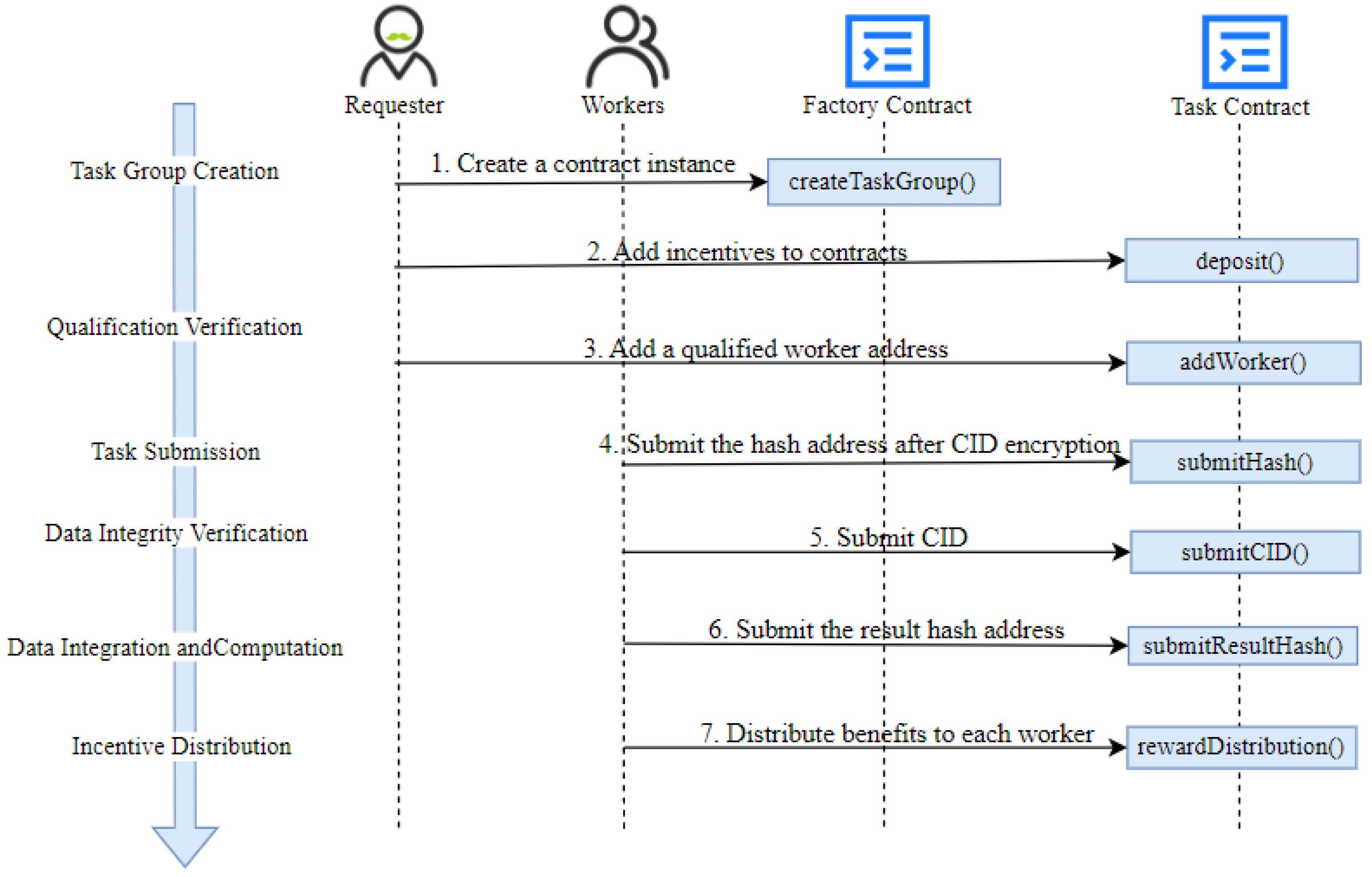

3.2. Design of Smart Contract

- Task Group Creation Stage: The requester calls the task group creation function, entering contract parameters through the factory contract to dynamically create and manage each task contract instance . Task parameters are stored by the requester on IPFS. By encapsulating task group creation logic within the factory contract, the smart contract enables modular task management and data encapsulation. Each task group exists as a distinct contract instance , simplifying management and interaction. A payable staking function is defined within the contract to allow the requester to add incentives at any time; without sufficient , the contract may fail to attract workers . The contract and task parameters are defined as follows:

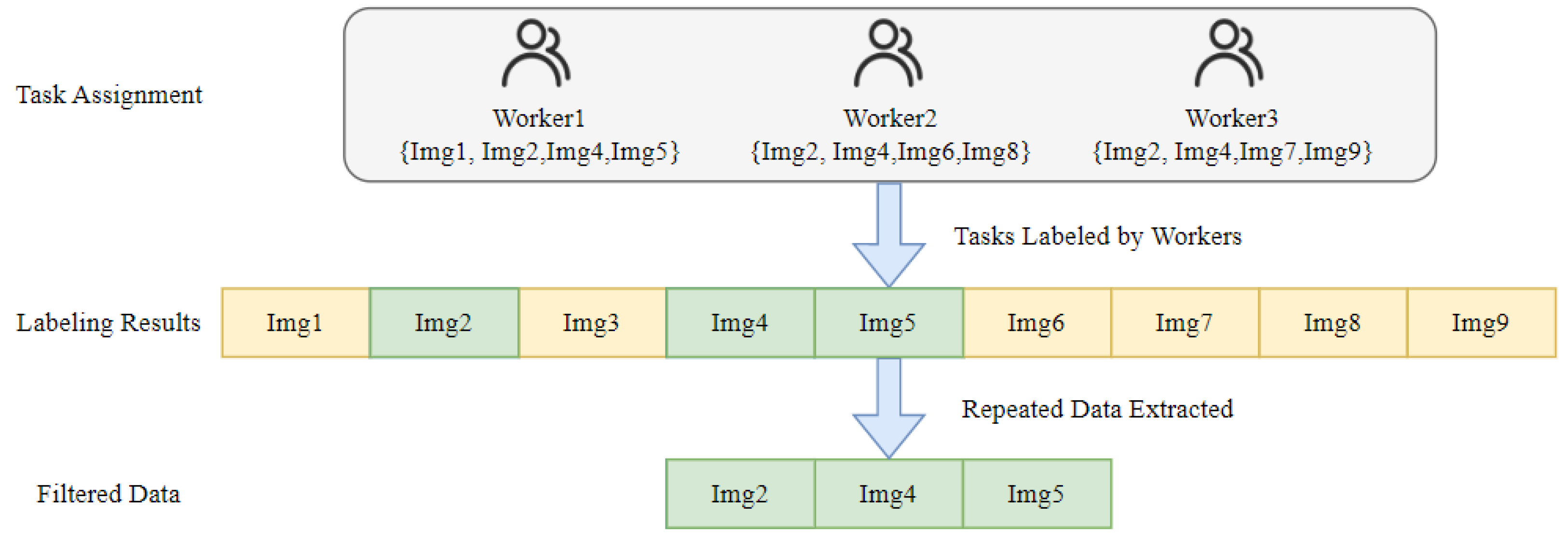

- Eligibility Verification Stage: During eligibility verification, worker reviews task parameters to examine the requester-defined task group and the eligibility verification tasks . This task set includes image data, annotation requirements, and a corresponding one-dimensional array . Worker assesses factors such as task difficulty and annotation cost to decide whether to accept the task. Upon acceptance, the worker extends τitask off-chain into a list of six-element arrays in the format , compiling the annotation results and submitting them for requester review. After confirming the worker’s qualification, the requester calls the add-worker function to add the worker’s address to the eligible workers mapping. This function can only be invoked by the contract creator and only workers recorded in this mapping can call the data submission function to proceed with annotation tasks. As shown in Figure 4, eligibleWorkers is a mapping from addresses to Boolean values, storing the addresses of workers qualified to submit data. The eligibility verification function first checks that the caller is the contract deployer and that the number of eligible workers is below the maximum limit. Only when these conditions are met can the Function 1 be executed. Upon a successful call, the provided worker address is set to true, and the current worker count increments by one.

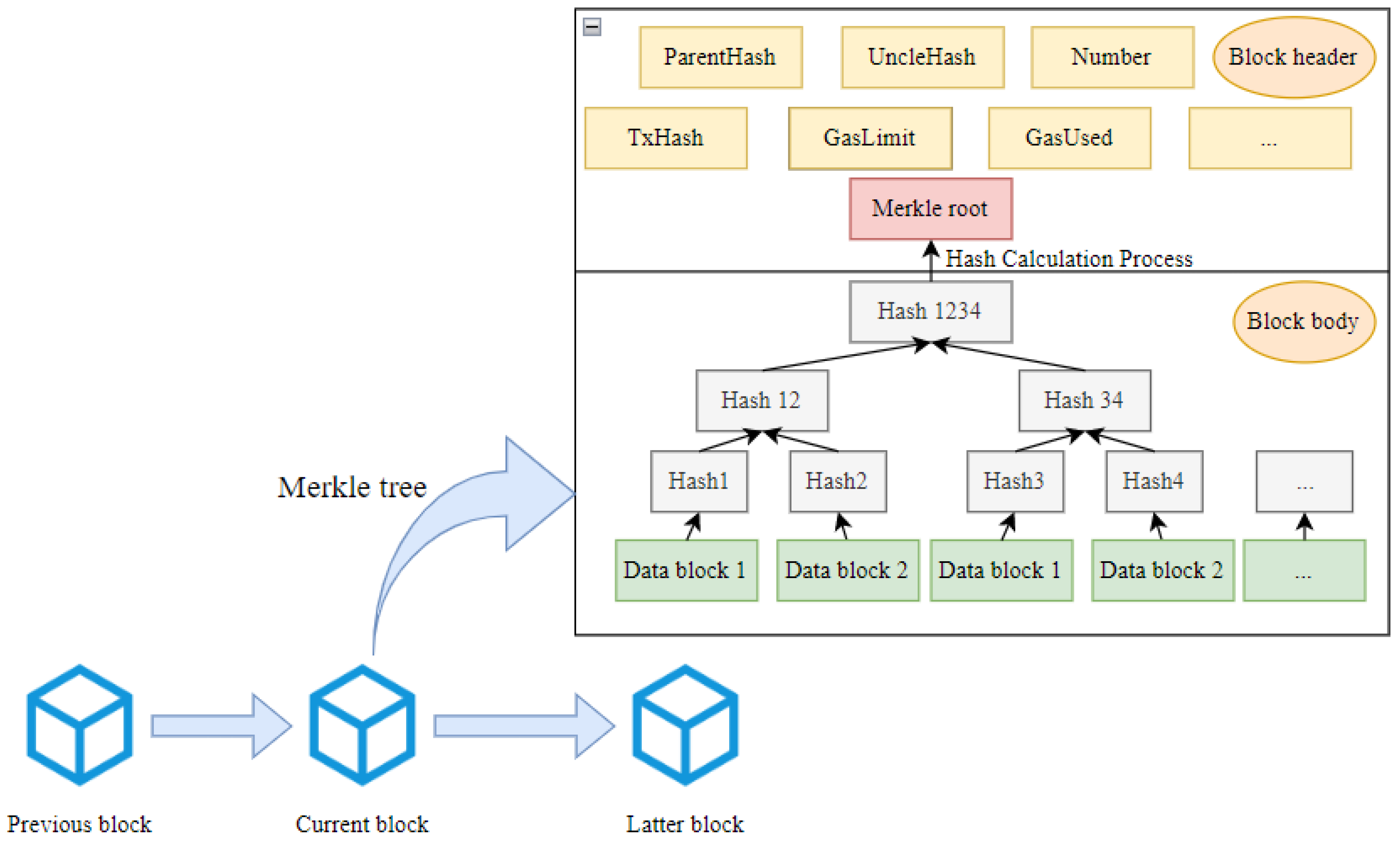

Function 1: AddWorker input: workerAddress output: workerAdded ← true 1. if (msg.sender == owner) then 2. if (currentEligibleWorkers < maxWorkers) then 3. [eligibleWorkers] ← workerAddress currentEligibleWorkers + 1 workerAdded ← true; 4. else 5. Return error; 6. else 7. Return error; 8. End - Task Submission Stage: When the first eligible worker with address is added to the eligible workers mapping, the contract enters the task submission stage. The requester uses an off-chain client to send a set of images and the corresponding one-dimensional annotation array for task to for annotation. After completing the annotation for task , submits the annotation results in a six-element array format denoted as , to the IPFS system, which returns a Content Identifier (CID). The CID serves as both the address and root hash of the Merkle Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) representing the content in IPFS. The CID generation process is shown in Equation (2): data is divided into 256KB blocks, . Each data block is hashed to produce a unique identifier . These hash values are then recursively hashed to construct a Merkle tree until reaching the root node, where the root hash (the topmost unique node) serves as the unique identifier for the entire dataset. The hash value at the highest level is the CID.

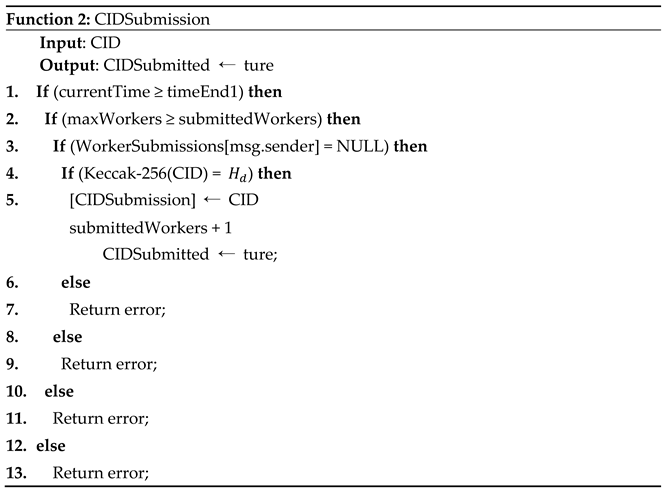

- Data Integrity Verification Stage: The smart contract enters the data integrity verification stage when either the time reaches or the number of workers who have submitted hash values reaches . In this stage, workers are required to call the Function 2, uploading the CID generated during the task submission stage to the smart contract for verifying the actual IPFS content. The smart contract then performs a hash calculation on the received CID to ensure data integrity and authenticity. The data integrity verification process is illustrated in Figure 5. In the CID submission function, the smart contract first checks that the caller has not previously submitted a CID and ensures that the function can only be invoked when the current time has reached or the number of workers who have submitted data meets the threshold . Within the function, the Keccak-256 hash function is called to convert the worker’s CID into a 256-bit byte hash value . This hash value is then compared to the hash submitted by the caller during the task submission stage. If the values match, the CID is stored in the submitted array, and a CID submission event is triggered. Finally, the function returns true, indicating successful submission; otherwise, it returns false, indicating a failed submission.

- Data Integration and Computation Stage: After confirming that the hash value submitted by worker matches the previously submitted IPFS address CID, the hash is added to the array of successfully submitted CIDs. Workers on the blockchain can use the CID viewing function to access all verified CIDs for the current task. They then retrieve the corresponding data from the IPFS system and perform an off-chain computation using the pre-defined data integration algorithm. This integration calculation produces a list of binary arrays , representing each worker's blockchain address and the corresponding incentive allocation. Once the integration calculation is complete, the worker uploads the result to the IPFS system, generating a new CID. Worker then applies a Keccak-256 hash function to this CID, obtaining a hash value , which is uploaded to the computation result submission function. The smart contract then aggregates all submitted hash values into a set . Since all workers are incentivized to protect their interests and due to the irreversible nature of hash functions (making it difficult to deduce the original data from the hash), each worker is motivated to perform the integration computation to ensure their rewards. The details of the DWBF (Dynamic Weight Bounding box fusion) computation process will be elaborated in Section 4. The final data integration result is determined by the hash value that appears most frequently in the submissions, according to the following formula:

- Incentive Distribution Stage: When the time reaches or the number of workers who submitted reaches , the smart contract transitions into the incentive distribution stage. At this stage, a designated on-chain worker must upload the original data, containing multiple binary arrays before the CID hash processing. This data represents each worker’s address and the corresponding incentive allocation for the task. The incentive distribution function within the smart contract will automatically execute the distribution of rewards to each worker based on the pre-defined incentive allocation scheme.

4. Quality-Driven Incentive Mechanism

4.1. Bounding Box Annotation Quality Verification Method

4.2. DWBF Algorithm and Quality-Driven Incentive Mechanism

- IoU Calculation: Assume the coordinates of bounding box are , and the coordinates of a bounding box within a cluster are , which correspond to (). The Intersection over Union (IoU) value between each bounding box and bounding boxes within cluster is calculated in three steps: First, calculate the coordinates of the intersection region using Equation (3). Next, calculate the area of the intersection region using Equation (4). Finally, calculate the IoU value using Equation (5):

- Cluster Computation: Assume we have a set of annotated bounding boxes . Each bounding box needs to be assigned to a cluster. For each bounding box , we calculate its IoU value with all existing bounding boxes in each cluster. Suppose there are currently clusters , and each cluster contains a set of bounding boxes . For each bounding box , iterate through clusters where the number of bounding boxes is at least , and calculate the IoU value with all bounding boxes in the cluster using Equation (6). Identify the maximum IoU value . If exceeds a specified threshold, add to cluster , otherwise, create a new cluster .

- IoU Dynamic Weight Calculation: For each bounding box provided by annotator , the sum of IoU values with all other bounding boxes within cluster is calculated pairwise. The final weight of is then computed using Equation (7). The bounding box with the highest weight in the cluster, , is selected as its first member.

- Weighted Bounding Box Calculation: Let cluster contain bounding boxes, where the dynamic IoU weight score of the i-th bounding box is , and its coordinates are given by . The coordinates of the weighted bounding box are calculated as follows in Equation (8):

- Label Calculation: For each cluster, a weighted summation is performed on the labels of all bounding boxes within the cluster, along with their corresponding weights . The total weight score for each label is accumulated, and the label with the highest cumulative weight is selected as the final label for the cluster. This process is described in Equation (9):

- Incentive Calculation: The incentive allocation for each worker aligns with their contribution and tiered incentive mechanism based on a composite score. First, the IoU and F1-score metrics are weighted in the evaluation of bounding boxes to compute each worker’s composite score using Equation (10). Workers are then grouped into different levels based on their composite scores, with incentives or penalties applied according to score ranges, as shown in Equation (11). If a worker’s composite score , they are classified as low-scoring and receive no incentive; If , they receive a partial incentive based on their score but face a progressive penalty; the lower the score, the higher the deduction, thus creating a positive incentive structure. If , high-scoring workers receive both their earned incentive and a bonus from the penalty pool, encouraging consistent high-quality annotations. This structure encourages workers to maintain high annotation quality while ensuring fair and tiered incentive distribution based on performance metrics.where and are weights for each metric, with .

5. Experiments and Evaluation

5.1. Experimental Setup

5.2. Smart Contract Execution Costs

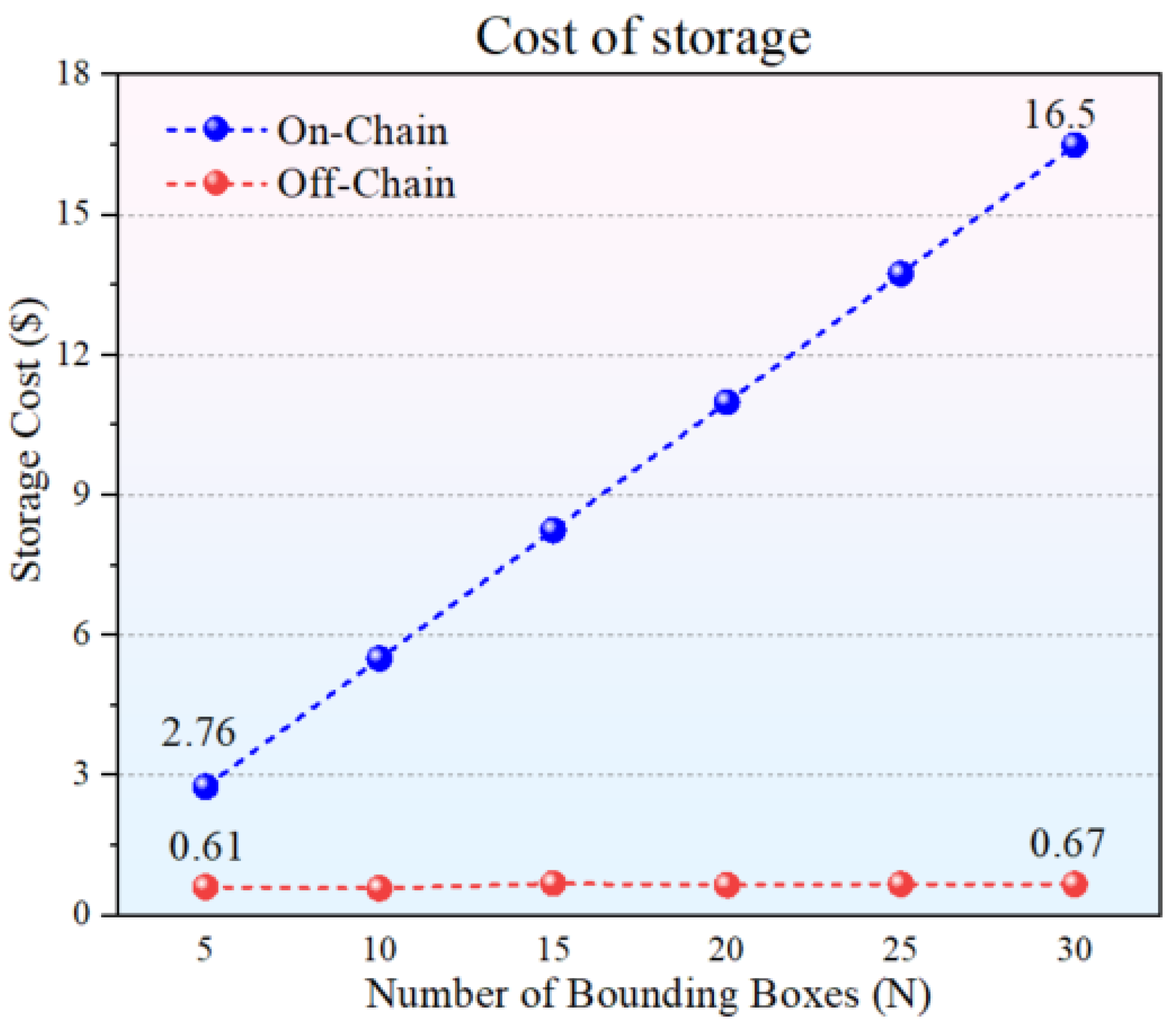

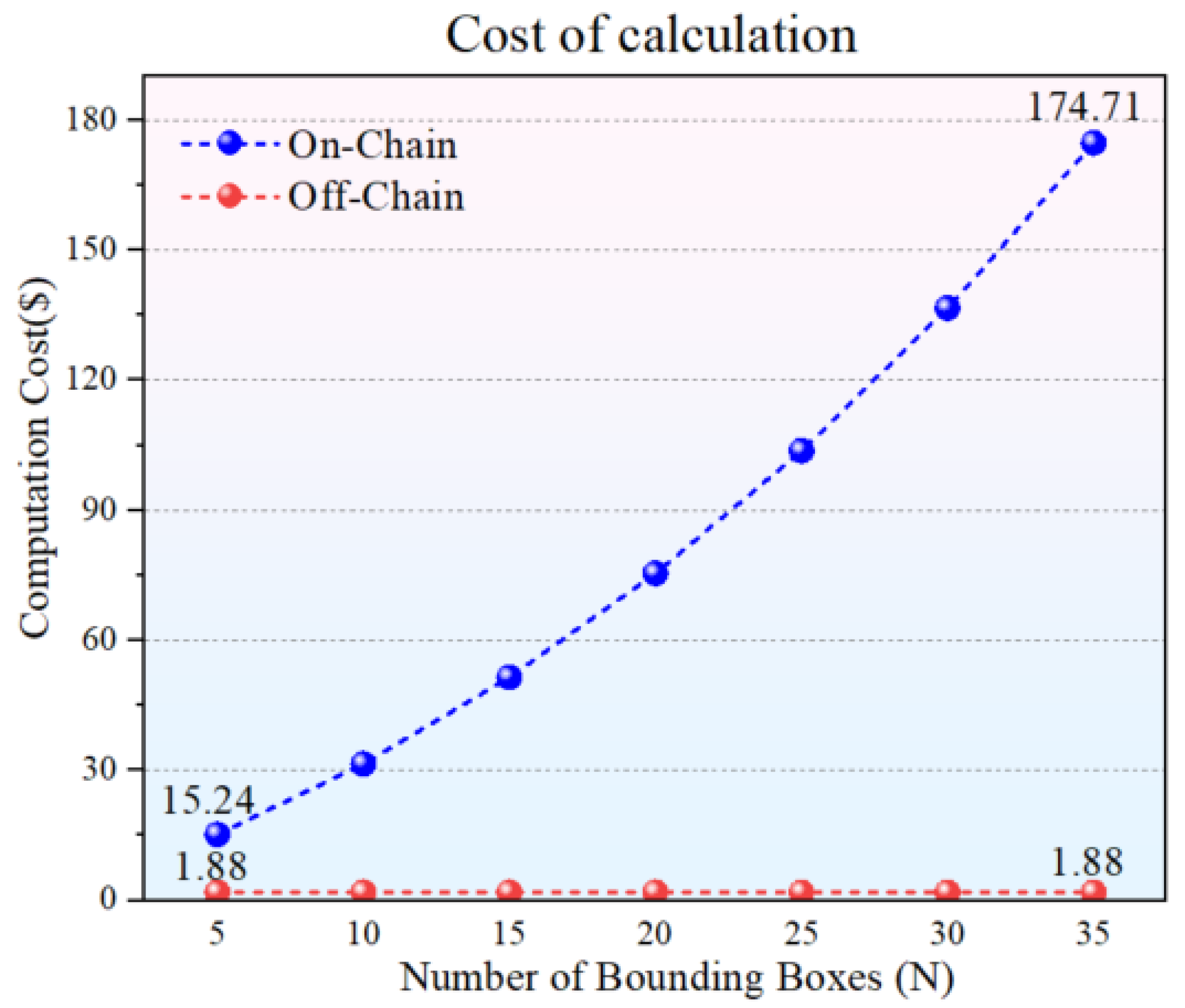

5.3. On-Chain vs. Off-Chain Resource Consumption

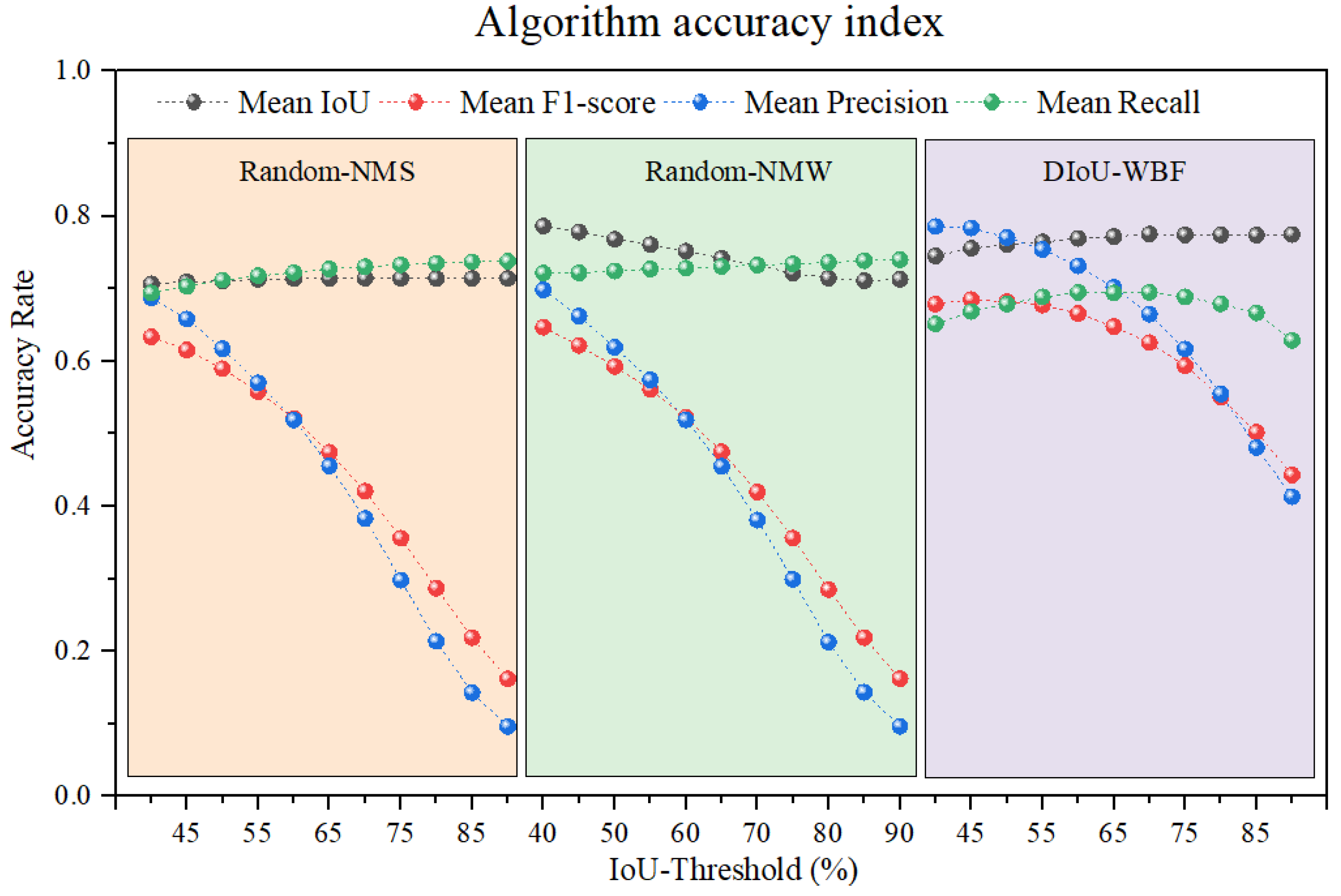

5.4. Comparison of Bounding Box Fusion Algorithms

- Regarding Mean Precision, DWBF experiences minimal declines across different thresholds, performing notably well at low to mid-range thresholds (45%-65%);

- In terms of Mean Recall, DWBF is slightly lower than Random-NMS and Random-NMW but remains within an acceptable range;

- Overall, DWBF achieves a significantly higher Mean F1-score than the other methods, particularly at low to mid IoU thresholds.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu L, Ouyang W, Wang X, et al. Deep learning for generic object detection: A survey[J]. International journal of computer vision, 2020, 128: 261-318.

- Kaur J, Singh W. Tools, techniques, datasets and application areas for object detection in an image: a review[J]. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 2022, 81(27): 38297-38351.

- Whang S E, Roh Y, Song H, et al. Data collection and quality challenges in deep learning: A data-centric ai perspective[J]. The VLDB Journal, 2023, 32(4): 791-813.

- Aldoseri A, Al-Khalifa K N, Hamouda A M. Re-thinking data strategy and integration for artificial intelligence: concepts, opportunities, and challenges[J]. Applied Sciences, 2023, 13(12): 7082.

- Wylde V, Rawindaran N, Lawrence J, et al. Cybersecurity, data privacy and blockchain: A review[J]. SN computer science, 2022, 3(2): 127.

- Xia H, McKernan B. Privacy in Crowdsourcing: a Review of the Threats and Challenges[J]. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 2020, 29: 263-301.

- Jia L, Shao B, Yang C, et al. A Review of Research on Information Traceability Based on Blockchain Technology[J]. Electronics (2079-9292), 2024, 13(20).

- Alsadhan A, Alhogail A, Alsalamah H. Blockchain-Based Privacy Preservation for the Internet of Medical Things: A Literature Review[J]. Electronics, 2024, 13(19): 3832.

- Thakur K S, Ahuja R, Singh R. IoT-GChain: Internet of Things-Assisted Secure and Tractable Grain Supply Chain Framework Leveraging Blockchain[J]. Electronics, 2024, 13(18): 3740.

- Kochovski, P.; Gec, S.; Stankovski, V.; Bajec, M.; Drobintsev, P.D. Trust management in a blockchain based fog computing platform with trustless smart oracles. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 101, 747–759 [CrossRef]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan K, B. Crowdsourcing research: data collection with Amazon’s Mechanical Turk[J]. Communication Monographs, 2018, 85(1): 140-156.

- CrowdSFL: A secure crowd computing framework based on blockchain and federated learning[J]. Electronics, 2020, 9(5): 773.

- Yang S, Zhang Y, Cui L, et al. A Web 3.0-Based Trading Platform for Data Annotation Service With Optimal Pricing[J]. IEEE Transactions on Network Science and Engineering, 2023.

- Witowski J, Choi J, Jeon S, et al. MarkIt: a collaborative artificial intelligence annotation platform leveraging blockchain for medical imaging research[J]. Blockchain in Healthcare Today, 2021, 4.

- Zhu XR, Wu HH, Hu W. FactChain: A Blockchain-based Crowdsourcing Knowledge Fusion System. Journal of Software, 2022, 33(10): 3546-3564(in Chinese). http://www.jos.org.cn/1000-9825/6627.

- Li M, Weng J, Yang A, et al. CrowdBC: A blockchain-based decentralized framework for crowdsourcing[J]. IEEE transactions on parallel and distributed systems, 2018, 30(6): 1251-1266.

- Han X, Liu Y. Research on the consensus mechanisms of blockchain technology. Netinfo Security, 2017, 17(9): 147-152 (in Chinese with English abstract).

- Xu J, Wang C, Jia X. A survey of blockchain consensus protocols[J]. ACM Computing Surveys, 2023, 55(13s): 1-35.

- de Ocáriz Borde H, S. An overview of trees in blockchain technology: merkle trees and merkle patricia tries[J]. University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2022.

- Taherdoost, H. Smart contracts in blockchain technology: A critical review[J]. Information, 2023, 14(2): 117.

- Khan S N, Loukil F, Ghedira-Guegan C, et al. Blockchain smart contracts: Applications, challenges, and future trends[J]. Peer-to-peer Networking and Applications, 2021, 14: 2901-2925.

- Cai W, Wang Z, Ernst J B, et al. Decentralized applications: The blockchain-empowered software system[J]. IEEE access, 2018, 6: 53019-53033.

- Casino F, Dasaklis T K, Patsakis C. A systematic literature review of blockchain-based applications: Current status, classification and open issues[J]. Telematics and informatics, 2019, 36: 55-81.

- Liu Z, Luong N C, Wang W, et al. A survey on blockchain: A game theoretical perspective[J]. IEEE Access, 2019, 7: 47615-47643.

- Xu X, Weber I, Staples M, et al. A taxonomy of blockchain-based systems for architecture design[C]//2017 IEEE international conference on software architecture (ICSA). IEEE, 2017: 243-252.

- Wang W, Hoang D T, Hu P, et al. A survey on consensus mechanisms and mining strategy management in blockchain networks[J]. Ieee Access, 2019, 7: 22328-22370.

- Lashkari B, Musilek P. A comprehensive review of blockchain consensus mechanisms[J]. IEEE access, 2021, 9: 43620-43652.

- Ferdous M S, Chowdhury M J M, Hoque M A, et al. Blockchain consensus algorithms: A survey[J]. arXiv:2001.07091, 2020.

- Gudgeon L, Moreno-Sanchez P, Roos S, et al. Sok: Layer-two blockchain protocols[C]//Financial Cryptography and Data Security: 24th International Conference, FC 2020, Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, –14, 2020 Revised Selected Papers 24. Springer International Publishing, 2020: 201-226.

- Gangwal A, Gangavalli H R, Thirupathi A. A survey of Layer-two blockchain protocols[J]. Journal of Network and Computer Applications, 2023, 209: 103539.

- Thibault L T, Sarry T, Hafid A S. Blockchain scaling using rollups: A comprehensive survey[J]. IEEE Access, 2022, 10: 93039-93054.

- Malik M, Malik M K, Mehmood K, et al. Automatic speech recognition: a survey[J]. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 2021, 80: 9411-9457.

- Yu H, Yang Z, Tan L, et al. Methods and datasets on semantic segmentation: A review[J]. Neurocomputing, 2018, 304: 82-103.

- Bostan L A M, Klinger R. An analysis of annotated corpora for emotion classification in text[J]. 2018.

| Public Blockchain | Consortium Blockchain | Private Blockchain | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | Anyone | Members | Internal access only |

| Consensus Mechanism | PoW / PoS / DPoS | RAFT / PBFT / IBFT | RAFT / PBFT / IBFT |

| Bookkeepers | All nodes | Consortium members | Individual |

| Incentive Mechanism | Required | Optional | N/A |

| Degree of Decentralization | Fully decentralized | Multi-centralized | Centralized |

| Security | High | Medium | Low |

| Cost | High | Medium | Low |

| Transparency | Public | Consortium-only | Internal only |

| Mbps | 20-100 tx/s | 1,000-10,000 tx/s | 10,000-100,000 tx/s |

| Typical Use Cases | Crypto, DeFi, NFTs | Cross-org payments, SCM | Internal audit, data mgmt |

| No. | Symbol | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Task set, eligibility verification task group | |

| 2 | Bounding box annotation task, ground truth of bounding box | |

| 3 | Requester | |

| 4 | Worker set, eligibility worker | |

| 5 | Contract instance | |

| 6 | Minimum weight threshold | |

| 7 | Worker reward | |

| 8 | Contract parameters, task parameters | |

| 9 | Data submission deadline, reward calculation deadline, maximum number of workers | |

| 10 | Task description | |

| 11 | Task address, requester address, worker address | |

| 12 | Data hash |

| Contract | Function | Gas Used | ETH Value | Cost($) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factory.sol | createTaskGroup | 298186 | 0.00137761 | 3.37 |

| TaskContract.sol | deposit | 2848 | 0.00001315 | 0.03 |

| addWorker | 52151 | 0.00024093 | 0.59 | |

| submitHash | 51381 | 0.00023738 | 0.58 | |

| submitCID | 13113 | 0.00006058 | 0.15 | |

| submitResultHash | 120999 | 0.00055901 | 1.37 | |

| rewardDistribution | 12000/person | 0.00005544 | 0.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).