2. Relevant Sections

The first study highlighting the ultrasonographic appearance of duplication cysts was published in 1989 by L.L. Barr et al. The article is based on a review of 8 duplication cyst cases aimed at determining whether the combination of an echogenic inner mucosal layer and a hypoechoic outer muscular layer was a consistent finding with diagnostic value. This pattern was found in all 8 cases, with 7 of them having the two layers visible in over 50% of the cyst wall. They compared these 8 enteric cyst cases with 27 other abdominal cyst cases, observing that none of the 27 cysts had the 2-layer pattern. Given this, they concluded that a double-layered pattern suggests a duplication cyst with high confidence, although an artifact mimicking this pattern was encountered in some cases, a situation in which care must be taken to avoid misinterpretation [

22].

In a 2005 study, G. Cheng et al. presented three cases with suspected enteric duplication cysts, highlighting the diagnostic pitfalls that may lead to misinterpretation. He described an ultrasound artifact that may mimic the double-layered configuration of the cyst wall, which may be resolved with transducer angulation. The factors contributing to the emergence of this false-positive double wall sign include the presence of a fibrous wall at the peripheral zone of a cystic structure, which confers a hypoechoic appearance similar to a "pseudo gut signature" or, alternatively, a thin layer of fat that produces a hyperechoic appearance. False-negative diagnostic information may arise in cases of infected duplication cysts due to the erosion of the mucosal layer, which leads to the subsequent loss of the characteristic hyperechoic inner wall. The study also suggests that the shared muscular layer between the cyst and the intestinal wall, which exhibits a "Y" configuration, may serve as a more reliable indicator for diagnosing enteric duplication cysts when adequately visualized [

8].

A 2017 study by E.O. Gerscovich et al. underscores the significance of observing peristalsis in patients with enteric duplication and Meckel diverticulum, as this finding is distinctive for these two entities. The assessment of the peristaltic wave should be conducted by maintaining the transducer in a stationary position over the area of interest under magnification for clearer visualization [

9].

Furthermore, a 2015 study by I. Tritou also underscored the critical importance of observing cystic peristalsis and the characteristic "Y" configuration of the muscle layer, noting that the multilaminar appearance of the cystic wall alone is insufficient for accurate diagnosis [

10].

In distinction from previously documented cases, H. Peng and colleagues, in their 2012 study, reported a case of an enteric duplication cyst exhibiting the characteristic "pseudo kidney sign". This sign, which appears as a well-defined hypoechoic reniform mass with a hyperechoic inner rim, has been observed in various other conditions, including colonic carcinoma, intussusception, and inflammatory bowel disease. This case report broadened the spectrum of differential diagnoses associated with the "pseudo kidney sign" [

11].

In a 2019 study, M. Kitami introduced the dynamic compression technique for diagnosing enteric duplication cysts, a novel diagnostic approach previously unexplored. This technique involves the deliberate compression of the cystic mass to assess its relationship with the adjacent bowel, facilitating the separation of the cyst from the surrounding intestinal structures. In the case of an enteric duplication cyst, separation cannot be achieved due to the shared wall between the cyst and the intestinal tract. As a dynamic examination, this result cannot be achieved with CT or MRI, further underscoring the utility of ultrasound in diagnosing enteric duplications by identifying the "pseudo-split wall sign". The study further concluded that the "5-layer sign" and presence of peristalsis are not sensitive indicators for enteric duplication. In contrast, the "split-wall sign" appears to offer the highest sensitivity and specificity, particularly when identified using the dynamic compression technique [

12].

In 2013, B.I. Offir and colleagues conducted a study to assess the utility of ultrasound in the prenatal diagnosis of enteric duplication cysts. They presented a case involving multiple duplication cysts, some in communication with the adjacent intestine and others isolated, identified prenatally via ultrasound and subsequently reassessed using MRI. Ultrasonography successfully identified the intestinal structure of the cystic wall and its relationship to the adjacent intestine, thus substantiating the diagnosis, with MRI serving as an auxiliary tool. The study concluded that prenatal diagnosis of enteric duplication cysts is feasible through ultrasound, making the diagnosis more common due to the use of this modality [

13].

Building upon the role of ultrasound in prenatal diagnosis, C. Nishizawa et al. underscored the efficacy of HDlive technology in the antenatal detection of enteric duplication cysts. They reported a case of a 27-week gestation foetus exhibiting an intra-abdominal cystic mass. Initially characterized by 2D ultrasonography, the mass appeared as a sonolucent structure with irregular internal echoes. Subsequently, a 3D multiplanar view and HDlive technology were employed, revealing more detailed and realistic features of the cystic mass: a thick wall, a significant amount of internal debris and no communication with adjacent intra-abdominal structures. The study concluded that HDlive technology has demonstrated substantial utility in characterizing both the internal and external features of the cysts, offering a more realistic perspective of the anatomy and thereby enhancing clinical management [

14].

3. Discussion

Enteric duplication cysts are uncommon congenital anomalies with an incidence of 1 in 4,500 births, showing a modest male predominance. They form during embryonic development, between the 4th and 8th weeks, and can be located anywhere along the gastrointestinal tract, from the oral cavity to the rectum [

6]. The distal ileum is the most frequent site of occurrence, accounting for 33–44% of cases [

6,

7].

The aetiology remains largely uncertain, with proposed theories including the split notochord hypothesis and the abortive twinning theory. However, the most widely accepted explanation is that enteric duplication cysts arise due to the pinching of a diverticulum during embryonic development [

6,

7].

The term "enteric duplication cyst" denotes a spherical or tubular structure positioned adjacent to the muscular wall of the intestine on the mesenteric side, exhibiting the following attributes: contact with the digestive tract, a muscular wall with two layers, a myenteric innervation, a submucous membrane, and a mucosa with a digestive or endoblast-derived epithelium [

24]. Histologically, the wall of an enteric duplication includes a muscular layer (muscularis propria) and a mucosal lining similar to that of the digestive tract. This mucosal layer may consist of typical small bowel epithelium or ectopic mucosa of various types, including ectopic pancreatic, gastric or respiratory tissue. Furthermore, the duplicated structure often shares its blood supply with the adjacent bowel [

4,

7,

15].

Intestinal duplication cysts are classified into two main categories. The first, the cystic type, accounts for approximately 80% of cases and typically does not communicate with the intestinal lumen. The second, the tubular type, constitutes about 20% of cases and generally maintains a direct connection with the bowel lumen, running parallel to it. The lumen of the cyst may be filled with a clear mucous substance, secreted by the mucosa itself. In certain instances, particularly when ectopic gastric mucosa undergoes ulceration, the cyst may become haemorrhagic [

16]. Duplications are typically solitary. The occurrence of multiple duplication cysts is rare; however, cases have been reported where multiple cysts are found within a single bowel segment or, more rarely, across two or more segments. In certain cases, the cysts are non-communicating and entirely isolated from the bowel, with no evidence of a shared wall. These exceptionally rare cysts may be multiple and are termed "atypical duplication cysts" [

6].

Several congenital anomalies have been reported in association with intestinal duplication cysts. These include spinal abnormalities, congenital heart disease, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, oesophageal atresia, pulmonary sequestrations, congenital cystic adenomatoid malformations and urinary malformations, with a prevalence of 16-26% [

4,

6,

17].

The symptomatology can vary depending on the location, type, size, mucosal lining and presence of complications. They are most frequently encountered in children, particularly within the first two years of life, often presenting as acute intestinal obstruction. A small proportion of cases remain asymptomatic until adulthood [

5,

7]. Duodenal duplications are usually symptomatic due to the cystic secretion, which distends the duplication, and finally obstructs the duodenal lumen [

24]. The predominant manifestations include recurrent abdominal pain and melena. Additionally, patients may exhibit symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, feeding intolerance or abdominal distension. The acute onset can arise from the mass effect of the cyst, attributable to the accumulation of secretions within it. This can manifest as severe abdominal pain or intestinal obstruction. Moreover, the cyst may serve as a focal point for intussusception or volvulus of the adjacent bowel loops. In rare instances, the mass effect on neighbouring structures can result in hydronephrosis or obstruction of the vena cava or biliary tree [

1,

5,

6].

In cases where the duplication cyst contains gastric mucosa or pancreatic tissue, it may give rise to serious complications such as ulceration, perforation, and acute bleeding accompanied by melena [

1].

Ultrasound is typically the preferred initial imaging modality for diagnosing bowel pathology in children, surpassing CT and radiography due to its ease of use and absence of radiation exposure. Additional advantages of ultrasonography in paediatric patients include its cost-effectiveness, wide accessibility, minimal need for preparation and the ability to be conducted without sedation. Some limitations include increased body mass, excessive bowel gas and reliance on subjective interpretation [

18].

For the assessment of enteric duplication cysts, children are generally required to maintain nothing-by-mouth (NPO) status for solids for approximately 4 hours prior to examination. They should consume 360-480 mL of clear liquids to help distend the bladder, facilitating the displacement of bowel loops from the pelvis. In certain cases, oral contrast agents may be administered to distend the intestines, offering a safe, well-tolerated option with high diagnostic efficacy [

18].

The ultrasound protocol for diagnosing enteric duplications involves initial imaging with a low-frequency sector transducer, followed by a high-frequency linear transducer for enhanced resolution. Doppler examination is conducted using the lowest pulse repetition frequency to minimize aliasing artifacts. During imaging, simultaneous manual compression from anterior and posterior positions is beneficial [

18].

On ultrasound, an intestinal duplication cyst typically presents as a hollow, well-circumscribed anechoic structure, most often spherical in shape, though it may appear tubular in approximately 20% of cases and is positioned on the mesenteric side of the intestine. The structure is generally unilocular, although, in rare instances, it may exhibit a multilocular configuration [

1]. In certain cases, septations or mucinous material may be observed within the cyst, even in the absence of complications [

6].

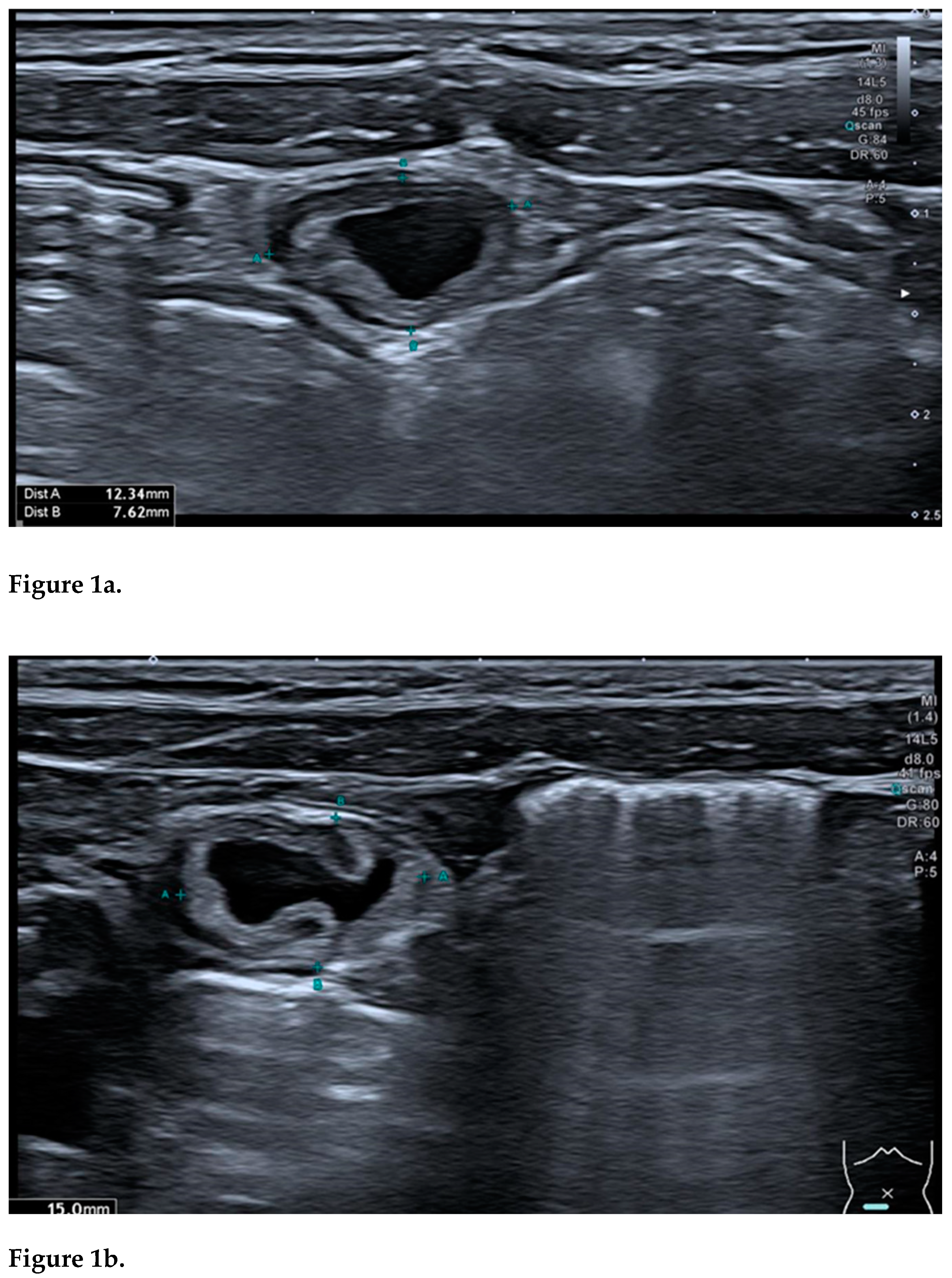

A hallmark feature of an uncomplicated intestinal duplication cyst is the "double-wall sign" or "gut signature sign". This consists of a hyperechoic inner layer, representing the mucosa, encased by a hypoechoic outer layer, corresponding to the muscularis propria (smooth muscle layer). Initially regarded as highly specific, this sign was later found to be present in various other abdominal masses, such as Meckel’s diverticulum and torsed ovarian cysts [

19,

20,

21].

Another valuable indicator for identifying an enteric duplication cyst is the "5-layer sign". This sign shows a cystic wall comprising three hyperechoic layers—the mucosa, submucosa, and serosa— and two hypoechoic layers, representing the muscularis mucosae and the muscular layer. Recognizing this layered architecture requires advanced sonographic expertise and high-resolution equipment (linear probe). However, high-resolution probes can occasionally produce false-positive results, sometimes visualizing up to nine layers. Additionally, identification can be complicated in cases of infection or haemorrhage, where the mucosal layer may not be visible [

1,

6,

20].

The "split wall sign" represents a significant pattern observed in duplication cysts, characterized by a "Y"-shaped configuration of the muscular layer. This phenomenon is attributed to the splitting of the common muscularis propria between the cyst and the adjacent intestinal wall, highlighting the close connection with the nearby intestine. According to reports, this "Y"-shaped configuration may be more specific for diagnosis, as it has not been described for any other type of abdominal cystic mass. In certain abdominal masses, the "pseudo-split wall sign" has been described, representing a significant diagnostic pitfall. To avoid misinterpretation, meticulous examination is essential and dynamic compression serves as an invaluable adjunctive technique. This method is useful in distinguishing a real split wall from a pseudo-split wall, as, in the case of a true duplication cyst, the cyst and the intestine remain inseparable under compression. The dynamic compression technique involves deliberate pressure applied to the lesion to observe its relationship with the adjacent bowel. This approach underscores one of the many advantages of ultrasound examination, a capability that cannot be replicated by other imaging modalities such as CT or MRI [

1,

10,

20].

Another distinctive feature of an enteric duplication is the presence of wall peristalsis. Manifested as a concentric contraction of the cyst wall, this phenomenon results in a temporary alteration of the cyst’s contour and shape, observable with the transducer held stationary on the mass for a minimum of 15 seconds. Although peristalsis is typically specific to intestinal duplication, this appearance has also been documented in some cases of Meckel’s diverticulum [

6,

9,

20].

Transabdominal gastrointestinal ultrasound (GIUS) offers the unique opportunity to examine the bowel non-invasively and in physiological condition. For properly trained users, GIUS has been shown to have good accuracy and repeatability not only in a primary work up, but also in the follow up of chronic diseases. Intestinal US is often suggested as the first imaging tool in patients with acute abdomen [

23].

Ultrasonographic techniques, such as Colour-Doppler and Power-Doppler, can be employed to rule out the presence of solid components within the cyst, as they typically reveal an absence of vascular signals within the cyst itself. The cyst wall, however, may exhibit a moderate vascular signal [

1].

In instances where enteric duplication cysts are complicated by inflammation, ulceration, or internal bleeding, the appearance of the "gut sign" may be absent. Consequently, the characteristic "5-layered cyst wall' pattern is seldom observed in such cases. Instead, the diagnosis can often be confirmed through the presence of the "Y"-configuration. In the event of haemorrhage resulting from the presence of ectopic gastric or pancreatic tissue, fluid levels with debris may become apparent within the cyst. Furthermore, the mesenteric fat may exhibit signs of inflammation due to the transmural extension [

1,

6,

19].

In cases of enteric duplication cysts presenting as acute abdomen, ultrasound can identify signs of intestinal obstruction with bowel loops distention, signs of intussusception or volvulus or compression of the adjacent organs due to mass effect [

1].

The "pseudo kidney sign" is rarely observed in cases of isolated or atypical intestinal duplications. It is characterized by the complete loss of the cystic wall layering due to severe congestion, presenting as a hyperechoic inner layer encompassed by a thick hypoechoic outer rim. This sign has been documented in pathologies such as colonic cancer and inflammatory bowel disease [

6,

11].

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is another imaging modality used for the evaluation and diagnosis of duplication cysts, offering the opportunity to perform fine needle aspiration to obtain definitive diagnosis and rule out more ominous lesions. The use of this procedure is still controversial, as the lesion can become infected during the needle aspiration [

2].

Ultrasonographic investigation during pregnancy contributes to an earlier diagnosis of such pathology, as early as 12 weeks of gestation, before the onset of the first clinical symptoms [26].

Prenatal ultrasound is capable of identifying approximately 20-30% of intestinal duplication cysts. Recently, there has been an increase in prenatal diagnosis, attributed to advancements in screening techniques and enhanced imaging resolution. Prenatal ultrasound can reveal the same signs as a postnatal one; however, the "double wall sign" may not always be discernible. The utilization of HDlive technology has provided a more realistic anatomical depiction of both the interior and exterior of the cyst, as well as its relationship with surrounding structures. This detailed anatomical understanding is crucial, as it enables improved management and the prevention of complications [

6,

13,

14].

CT and MRI may be utilized in cases of diagnostic uncertainty or when the localization of the cystic mass via ultrasound proves challenging. These modalities are not typically employed as routine diagnostic tools due to the requirement for sedation and, in the case of CT, the exposure to ionizing radiation. One of their notable advantages is their capacity to provide detailed information regarding the anatomical relationships with surrounding structures. On MRI, the cystic nature is evidenced by a high-intensity signal on T2-weighted sequences and a low-intensity signal on T1-weighted sequences. On diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), they do not exhibit restricted diffusion. CT imaging reveals these structures as fluid-density masses, which may become hyperdense in the event of haemorrhage. Post-contrast, they demonstrate parietal enhancement similar to that of the intestine [

1,

7].

The differential diagnosis for abdominal cystic masses in paediatric patients encompasses pathologies such as mesenteric cysts, ovarian cysts, duplication cysts, anorectal malformations, lymphangiomas, hydronephrosis, Meckel’s diverticulum and cystic tumours [

13,

19].

Owing to the widespread availability of antenatal diagnosis, intestinal duplication cysts are frequently identified prenatally. Surgical intervention, which involves the complete excision of the enteric duplication cyst and closure of the parietal defect, is imperative in symptomatic patients. Studies indicate that early excision correlates with reduced morbidity and mortality. In instances where there is communication between the cyst and the adjacent intestine, a bowel resection may also be warranted. Regarding asymptomatic patients, the treatment remains a matter of debate. Reports advocate for surgical intervention due to the high incidence of complications such as intestinal obstruction, bleeding, or, in rare cases, malignant transformation in adulthood [

1,

6]. Total resection is not always possible, for example, due to the proximity to the distal part of the bilio-pancreatic duct or to the terminal segment of the common bile duct, which may have the same blood supply as the cyst. In these cases, partial resection or internal derivation must be carried out [

12]. In fact, some authors claim that most intestinal duplications share a common muscular wall and blood supply in the mesenteric border with the native bowel. Therefore, cyst excision alone may rarely be carried out, and resection of the adjacent bowel is the preferred treatment. Nowadays, the laparoscopic surgical approach is a feasible option in the treatment of duplication cysts [

25].

4. Conclusions

Enteric duplication cysts are rare congenital anomalies of the digestive tract with significant clinical importance due to their variable presentations and diagnostic challenges, often mimicking other abdominal masses. They are characterized by the presence of a mucosal lining, similar to that of the gastrointestinal tract, and a muscular layer.

Due to their nonspecific symptoms, diagnosing intestinal duplication cysts can be challenging. Ultrasonography is the preferred diagnostic tool because of its accessibility, cost-effectiveness, absence of ionizing radiation exposure, and versatility, especially in paediatric cases. Ultrasound provides critical indicators for identifying these abdominal masses, such as the "double-wall sign" and the typical "Y"-shaped configuration of the muscular layer. The "5-layer sign", which reveals the detailed architecture of the cyst wall, is also a valuable diagnostic marker, though it requires high-resolution equipment and advanced sonographic expertise. Newer techniques, such as dynamic compression and HDlive technology, have enhanced the precision of the diagnosis, aiding in the differentiation of enteric duplication cysts from other abdominal masses. Dynamic compression is particularly useful for assessing the relationship between the cyst and adjacent structures, highlighting one of ultrasound’s advantages, as it allows real-time interaction with the cyst, which is not possible with CT or MRI. HDlive technology further contributes to prenatal and postnatal diagnosis by offering a realistic view, enhancing visualization of the cyst’s anatomy and its relationship with nearby structures.

In summary, despite the diagnostic challenges posed by the variability of enteric duplication cysts, ultrasonography remains an invaluable tool, with recent advancements significantly enhancing detection accuracy and aiding in appropriate clinical management.

5. Future Directions

The ultrasonographic diagnosis of enteric duplication cysts in paediatric patients has undergone substantial refinement, establishing it as a non-invasive, accessible, and precise approach for detecting these rare abdominal anomalies. Nevertheless, several emerging advancements hold promise for further enhancing diagnostic accuracy and improving patient outcomes.

Firstly, the progression of high-resolution ultrasound technology offers remarkable potential. Innovations in transducer engineering and imaging software may yield more refined visualization of cyst anatomy. Moreover, the integration of 3D and 4D ultrasonography could provide comprehensive anatomical perspectives, facilitating more precise differentiation of enteric duplication cysts from other gastrointestinal or abdominal pathologies.

Secondly, advancing the ultrasonographic diagnosis of intestinal duplication cysts will require larger prospective studies that encompass diverse patient populations across multiple centres to ensure broad applicability of findings. Such studies, by expanding sample sizes and inclusivity, can capture variations in cyst presentation and ultrasonographic characteristics more accurately. Additionally, these studies could shed light on long-term outcomes and the comparative effectiveness of different diagnostic and management approaches. Collaborative research among paediatric radiologists, gastroenterologists and surgeons will enable the development of refined diagnostic criteria and enhanced clinical guidelines, ultimately elevating the quality of patient care.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning algorithms into ultrasonographic diagnostics has the potential to transform this field. AI-powered tools can support radiologists by detecting subtle patterns and anomalies, thereby minimizing diagnostic errors and enhancing precision.

Lastly, continuous education and training for healthcare professionals, through regular updates and workshops on the latest ultrasonographic techniques, will be essential to maintaining high diagnostic standards. Such initiatives will not only enhance practitioners' skills but also foster a deeper understanding of emerging technologies, ultimately contributing to improved patient outcomes and advancing the field of paediatric imaging.