Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. DEA in Cross-Country Analysis of Energy Efficiency

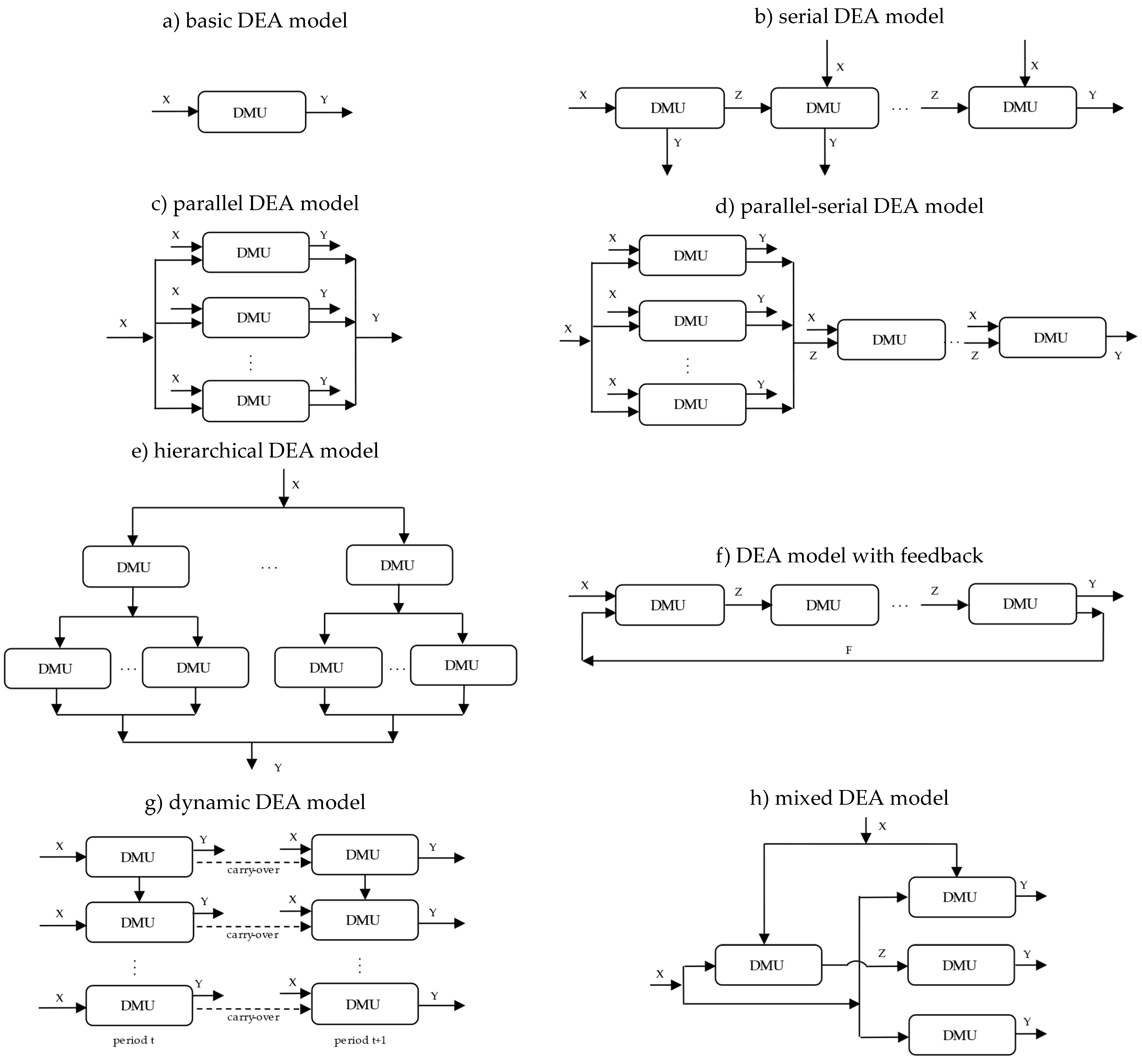

2.2. NDEA in Assessing Energy Efficiency

2.3. DEA in Assessing the Impact of Geographical Location on Energy Efficiency

3. Research Methods and Data

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M.; Rosado, P. CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Our World Data 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nazarko, Ł.; Žemaitis, E.; Wróblewski, Ł.K.; Šuhajda, K.; Zajączkowska, M. The Impact of Energy Development of the European Union Euro Area Countries on CO2 Emissions Level. Energies 2022, 15, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiatros-Motyka, M. Global Electricity Review 2023; Ember, 2023.

- Budak, G.; Chen, X.; Celik, S.; Ozturk, B. A Systematic Approach for Assessment of Renewable Energy Using Analytic Hierarchy Process. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2019, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, S.E.; Ibrahim, M.D.; Daneshvar, S. Dual Efficiency and Productivity Analysis of Renewable Energy Alternatives of OECD Countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eerens, H.; de Visser, E. Wind-Energy Potential in Europe 2020-2030. ETC/ACC Technical Paper; The European Topic Centre on Air and Climate Change, 2008.

- Li, W.; Ji, Z.; Dong, F. Global Renewable Energy Power Generation Efficiency Evaluation and Influencing Factors Analysis. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 33, 438–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, M.; Betak, J.; Rosina, K.; Chrkav, D.; Suriova, N.; Cebecauer, T.; Caltik, M.; Erdelyi, B. Global Photovoltaic Power Potential by Country; Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP); World Bank Group: Washington, D.C, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Emrouznejad, A.; Marra, M.; Yang, G.; Michali, M. Eco-Efficiency Considering NetZero and Data Envelopment Analysis: A Critical Literature Review. IMA J. Manag. Math. 2023, dpad002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaples, G.; Papathanasiou, J. Data Envelopment Analysis and the Concept of Sustainability: A Review and Analysis of the Literature. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 138, 110664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, J. Data Envelopment Analysis Application in Sustainability: The Origins, Development and Future Directions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 264, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C. Network Data Envelopment Analysis; International Series in Operations Research & Management Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-31716-8. [Google Scholar]

- Chodakowska, E.; Nazarko, J. Network DEA Models for Evaluating Couriers and Messengers. Procedia Eng. 2017, 182, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tone, K.; Tsutsui, M. Network DEA: A Slacks-Based Measure Approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 197, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Alnafrah, I.; Zhou, Y. A Systemic Efficiency Measurement of Resource Management and Sustainable Practices: A Network Bias-Corrected DEA Assessment of OECD Countries. Resour. Policy 2024, 90, 104771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarko, J.; Chodakowska, E.; Nazarko, Ł. Evaluating the Transition of the European Union Member States towards a Circular Economy. Energies 2022, 15, 3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarko, L.; Melnikas, B. Operationalising Responsible Research and Innovation – Tools for Enterprises. Eng. Manag. Prod. Serv. 2019, 11, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarko, Ł. Responsible Research and Innovation in Industry: From Ethical Acceptability to Social Desirability. In Corporate Social Responsibility in the Manufacturing and Services Sectors; Golinska-Dawson, P., Spychała, M., Eds.; EcoProduction; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2019; ISBN 978-3-642-33850-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mardani, A.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Streimikiene, D.; Jusoh, A.; Khoshnoudi, M. A Comprehensive Review of Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) Approach in Energy Efficiency. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 70, 1298–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Guo, W.; Zhang, F. Comprehensive Evaluation of Renewable Energy Technical Plans Based on Data Envelopment Analysis. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 3583–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jiang, F.; Li, R. Assessing Supply Chain Greenness from the Perspective of Embodied Renewable Energy – A Data Envelopment Analysis Using Multi-Regional Input-Output Analysis. Renew. Energy 2022, 189, 1292–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papież, M.; Śmiech, S.; Frodyma, K. Factors Affecting the Efficiency of Wind Power in the European Union Countries. Energy Policy 2019, 132, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Alnafrah, I.; Zhou, Y. A Systemic Efficiency Measurement of Resource Management and Sustainable Practices: A Network Bias-Corrected DEA Assessment of OECD Countries. Resour. Policy 2024, 90, 104771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavi, N.K.; Mavi, R.K. Energy and Environmental Efficiency of OECD Countries in the Context of the Circular Economy: Common Weight Analysis for Malmquist Productivity Index. J. Environ. Manage. 2019, 247, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida Neves, S.; Cardoso Marques, A.; Moutinho, V. Two-Stage DEA Model to Evaluate Technical Efficiency on Deployment of Battery Electric Vehicles in the EU Countries. Transp. Res. Part Transp. Environ. 2020, 86, 102489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, N.; Meybodi, M.E. Dynamic Spillover Effects of Renewable Energy Efficiency in the European Countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 11698–11715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.-N.; Nguyen, T.T.-V.; Chiang, C.-C.; Le, H.-D. Evaluating Renewable Energy Consumption Efficiency and Impact Factors in Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Countries: A New Approach of DEA with Undesirable Output Model. Renew. Energy 2024, 227, 120586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Nakagawa, K.; Matsumoto, K. Evaluating Solar Photovoltaic Power Efficiency Based on Economic Dimensions for 26 Countries Using a Three-Stage Data Envelopment Analysis. Appl. Energy 2023, 335, 120714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-N.; Nguyen, N.-A.-T.; Dang, T.-T.; Wang, J.-W. Assessing Asian Economies Renewable Energy Consumption Efficiency Using DEA with Undesirable Output. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 2022, 43, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-N.; Dang, T.-T.; Tibo, H.; Duong, D.-H. Assessing Renewable Energy Production Capabilities Using DEA Window and Fuzzy TOPSIS Model. Symmetry 2021, 13, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Lozano, G.; Cifuentes-Yate, M. Efficiency Assessment of Electricity Generation from Renewable and Non-renewable Energy Sources Using Data Envelopment Analysis. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 19597–19610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, E.; Kınacı, H.; Shehzad, K. Environmental Efficiency of Disaggregated Energy R&D Expenditures in OECD: A Bootstrap DEA Approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 19381–19390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maradin, D.; Cerović, L.; Šegota, A. The Efficiency of Wind Power Companies in Electricity Generation. Energy Strategy Rev. 2021, 37, 100708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, N.; Jones, D.; Treloar, R. A Cross-European Efficiency Assessment of Offshore Wind Farms: A DEA Approach. Renew. Energy 2020, 151, 1186–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-N.; Hsu, H.-P.; Wang, Y.-H.; Nguyen, T.-T. Eco-Efficiency Assessment for Some European Countries Using Slacks-Based Measure Data Envelopment Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenente, M.; Henriques, C.; Da Silva, P.P. Eco-Efficiency Assessment of the Electricity Sector: Evidence from 28 European Union Countries. Econ. Anal. Policy 2020, 66, 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakshit, I.; Mandal, S.K. A Global Level Analysis of Environmental Energy Efficiency: An Application of Data Envelopment Analysis. Energy Effic. 2020, 13, 889–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-N.; Tibo, H.; Duong, D.H. Renewable Energy Utilization Analysis of Highly and Newly Industrialized Countries Using an Undesirable Output Model. Energies 2020, 13, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali Sepehr, M.; Haeri, A.; Ghousi, R. A Cross-Country Evaluation of Energy Efficiency from the Sustainable Development Perspective. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2019, 13, 991–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezősi, A.; Szabó, L.; Szabó, S. Cost-Efficiency Benchmarking of European Renewable Electricity Support Schemes. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 98, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camioto, F.D.C.; Mariano, E.B.; Santana, N.B.; Yamashita, B.D.; Rebelatto, D.A.D.N. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Efficiency: An Analysis of Latin American Countries. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2018, 37, 2116–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robaina, M.; Dias, M.F. Energy Efficiency and Its Determinants: An Empirical Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2018 15th International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM); IEEE: Lodz, June, 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Gökgöz, F.; Güvercin, M.T. Energy Security and Renewable Energy Efficiency in EU. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 96, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chiu, Y.; Lin, T.-Y. Energy and Environmental Efficiency in Different Chinese Regions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Xiao, Q.-W.; Ren, F.-R. Assessing the Efficiency and CO2 Reduction Performance of China’s Regional Wind Power Industry Using an Epsilon-Based Measure Model. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 672183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Q.G.; Chen, H.T.; Li, X.; Ma, C. Comprehensive Assessment of Regional Sustainability via Emergy, Green GDP And DEA: A Case Study in Guizhou Province, China. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2021, 19, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.P.; Singh, S.K. The Dynamics of Indian Energy Mix: A Two-Phase Analysis. Benchmarking Int. J. 2022, 29, 1162–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayir Ervural, B.; Zaim, S.; Delen, D. A Two-Stage Analytical Approach to Assess Sustainable Energy Efficiency. Energy 2018, 164, 822–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-N.; Quynh Le, T.; Dang, T.-T. Measuring Operating Efficiency of Solar Photovoltaic Power Plants Using Epsilon-Based Measure Model: A Case Study in Vietnam. Meas. Control 2023, 56, 874–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Chachuli, F.S.; Ahmad Ludin, N.; Mat, S.; Sopian, K. Renewable Energy Performance Evaluation Studies Using the Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA): A Systematic Review. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2020, 12, 062701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Kourtzidis, S.; Tzeremes, P.; Tzeremes, N. A Robust Network DEA Model for Sustainability Assessment: An Application to Chinese Provinces. Oper. Res. 2022, 22, 235–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.-C.; Jiang, J.; Chen, X.-P. Policy, Technical Change, and Environmental Efficiency: Evidence of China’s Power System from Dynamic and Spatial Perspective. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 323, 116232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, K.; Iftikhar, Y.; Chen, S.; Amin, S.; Manzoor, A.; Pan, J. Analysis of Inter-Temporal Change in the Energy and CO2 Emissions Efficiency of Economies: A Two Divisional Network DEA Approach. Energies 2020, 13, 3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wei, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J. China’s Provincial Eco-Efficiency and Its Driving Factors—Based on Network DEA and PLS-SEM Method. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 8702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavassoli, M.; Ketabi, S.; Ghandehari, M. Developing a Network DEA Model for Sustainability Analysis of Iran’s Electricity Distribution Network. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 122, 106187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Yu, X.; Chiu, Y.; Chang, T.-H. Dynamic Linkages among Economic Development, Energy Consumption, Environment and Health Sustainable in EU and Non-EU Countries. Healthcare 2019, 7, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Yu, X.; Chiu, Y.-H.; Lin, T.-Y. Energy Efficiency and Health Efficiency of Old and New EU Member States. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, J.; Lu, C.; Li, Y.; Chiu, Y.; Xu, Y. Environmental Assessment of European Union Countries. Energies 2019, 12, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chiu, Y.; Lin, T.-Y. Research on New and Traditional Energy Sources in OECD Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iftikhar, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Wang, B. Energy and CO2 Emissions Efficiency of Major Economies: A Network DEA Approach. Energy 2018, 147, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Wan, Y.; Yuan, J.; Yin, J.; Baležentis, T.; Streimikiene, D. Economic and Technical Efficiency of the Biomass Industry in China: A Network Data Envelopment Analysis Model Involving Externalities. Energies 2017, 10, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali Saraji, M.; Streimikiene, D.; Suresh, V. A Novel Two-Stage Multicriteria Decision-Making Approach for Selecting Solar Farm Sites: A Case Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 444, 141198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunrinde, O.; Shittu, E. Benchmarking Performance of Photovoltaic Power Plants in Multiple Periods. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2023, 43, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Yang, Y.; Li, W. Analysis of Dynamic Renewable Energy Generation Efficiency and Its Influencing Factors Considering Cooperation and Competition between Decision-Making Units: A Case Study of China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoudi, M.; Ait Sidi Mou, A.; Idrissi, A.; Ihoume, I.; Arbaoui, N.; Benchrifa, M. New Approach to Prioritize Wind Farm Sites by Data Envelopment Analysis Method: A Case Study. Ocean Eng. 2023, 271, 113820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-N.; Nguyen, H.-P.; Wang, J.-W. A Two-Stage Approach of DEA and AHP in Selecting Optimal Wind Power Plants. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafaeipour, A.; Qolipour, M.; Rezaei, M.; Jahangiri, M.; Goli, A.; Sedaghat, A. A Novel Integrated Approach for Ranking Solar Energy Location Planning: A Case Study. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2021, 19, 698–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siampour, L.; Vahdatpour, S.; Jahangiri, M.; Mostafaeipour, A.; Goli, A.; Shamsabadi, A.A.; Atabani, A. Techno-Enviro Assessment and Ranking of Turkey for Use of Home-Scale Solar Water Heaters. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 43, 100948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-N.; Nguyen, N.-A.-T.; Dang, T.-T.; Bayer, J. A Two-Stage Multiple Criteria Decision Making for Site Selection of Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Power Plant: A Case Study in Taiwan. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 75509–75525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariano, J.; Liao, M.; Ay, H. Performance Evaluation of Solar PV Power Plants in Taiwan Using Data Envelopment Analysis. Energies 2021, 14, 4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-N.; Dang, T.-T.; Nguyen, N.-A.-T. Location Optimization of Wind Plants Using DEA and Fuzzy Multi-Criteria Decision Making: A Case Study in Vietnam. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 116265–116285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanjarpanah, H.; Jabbarzadeh, A.; Seyedhosseini, S.M. A Novel Multi-Period Double Frontier Network DEA to Sustainable Location Optimization of Hybrid Wind-Photovoltaic Power Plant with Real Application. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 159, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W.; Rhodes, E. Measuring the Efficiency of Decision Making Units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1978, 2, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, M.J. The Measurement of Productive Efficiency. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. Gen. 1957, 120, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Färe, R.; Grosskopf, S. Intertemporal Production Frontiers: With Dynamic DEA; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1996; ISBN 978-94-010-7309-7. [Google Scholar]

- Färe, R.; Grosskopf, S. Network DEA. Socioecon. Plann. Sci. 2000, 34, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C. Network Data Envelopment Analysis. Foundations and Extensions; International Series in Operations Research & Management Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-31716-8. [Google Scholar]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W.; Golany, B.; Halek, R.; Klopp, G.; Schmitz, E.; Thomas, D. Two-Phase Data Envelopment Analysis Approaches to Policy Evaluation and Management of Army Recruiting Activities: Tradeoffs between Joint Services and Army Advertising. Cent. Cybern. Stud. Univ. Tex.-Austin Austin Tex. USA 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Färe, R.; Whittaker, G. An Intermediate Input Model of Dairy Production Using Complex Survey Data. J. Agric. Econ. 1995, 46, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Cook, W.D. Modeling Data Irregularities and Structural Complexities in Data Envelopment Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, 2010; ISBN 978-0-387-71607-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gavurova, B.; Kocisova, K.; Sopko, J. Health System Efficiency in OECD Countries: Dynamic Network DEA Approach. Health Econ. Rev. 2021, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maleki, S.; Ebrahimnejad, A.; Kazemi Matin, R. Pareto–Koopmans Efficiency in Two-stage Network Data Envelopment Analysis in the Presence of Undesirable Intermediate Products and Nondiscretionary Factors. Expert Syst. 2019, 36, e12393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Lin, L.; Xiao, H.; Ma, C.; Wu, S. Stochastic Network DEA Models for Two-Stage Systems under the Centralized Control Organization Mechanism. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 110, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavassoli, M.; Fathi, A.; Saen, R.F. Assessing the Sustainable Supply Chains of Tomato Paste by Fuzzy Double Frontier Network DEA Model. Ann. Oper. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodakowska, E.; Nazarko, J. Hybrid Rough Set and Data Envelopment Analysis Approach to Technology Prioritisation. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2020, 26, 885–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, K.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y. Efficiency Measurement in Multi-Period Network DEA Model with Feedback. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 175, 114815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data Envelopment Analysis: A Handbook on the Modeling of Internal Structures and Networks; Cook, W.D., Zhu, J., Eds.; International Series in Operations Research & Management Science; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2014; Vol. 208, ISBN 978-1-4899-8067-0. [Google Scholar]

- Tone, K.; Tsutsui, M. Dynamic DEA with Network Structure: A Slacks-Based Measure Approach. Omega 2014, 42, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khezrimotlagh, D.; Kaffash, S.; Zhu, J. U.S. Airline Mergers’ Performance and Productivity Change. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2022, 102, 102226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Wind Atlas 3.0 2023.

- Global Photovoltaic Power Potential by Country 2023.

- Our World in Data, Population & Demography Data 2023.

- World Population Prospects 2022, Online Edition. 2022.

- The World Bank Data 2021.

- Renewable Capacity Statistics 2023; International Renewable Energy Agency, 2023.

- Our World in Data, Wind Energy Generation 2023.

- Our World in Data, Solar Power Generation 2023.

- Jaanti, M. Solar Energy in Finland & Market Entry. 2016.

| Title (Year) | DMU | DEA model | Analysis Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic spillover effects of renewable energy efficiency in the European countries (2024) [26] | 25 European countries from 2005 and 2020 | two-stage: DEA and regression | Inputs: renewable energy consumption, capital labour Outputs: GDP Influencing factors: GDP, energy price, renewable energy consumption, information and communications technology, industrial value added |

| Evaluating renewable energy consumption efficiency and impact factors in Asia-pacific economic cooperation countries: A new approach of DEA with undesirable output model (2024) [27] | 21 APEC member countries from 2011 to 2020 | DEA with undesirable output | Inputs: foreign direct investment total energy consumption, total renewable energy capacity Outputs: GDPUndesirables: GHG |

| Evaluating solar photovoltaic power efficiency based on economic dimensions for 26 countries using a three-stage data envelopment analysis (2023) [28] | 26 countries from 2000 to 2020 | three-stage: DEA-SFA-DEA | Inputs: capital, labour, PV installed capacity, PV patents Output: PV generation Environment variables: proportion of the urban population, GDP per capita, CO2 |

| Assessing Asian Economies Renewable Energy Consumption Efficiency Using DEA with Undesirable Output (2022) [29] | 14 Asian countries in 2019 | DEA with undesirable output | Inputs: labour, energy consumption, the share of renewable energy, and total renewable energy capacity Outputs: CO2 and GDP |

| Global renewable energy power generation efficiency evaluation and influencing factors analysis (2022) [7] | 36 countries from 2009 to 2018 | Super efficiency DEA, MI, and random forest regression model to analyse the influence of the selected factors | Inputs: five types of renewable energy installed capacity Outputs: renewable energy power generation Influencing factors: population size and density, economic level, urbanisation rate, production level, industrialisation level and structure, electricity and energy structure, carbon emissions, and technology level |

| Assessing Renewable Energy Production Capabilities Using DEA Window and Fuzzy TOPSIS Model [30] (2021) | 42 countries 2010–2019 | DEA window and FTOPSIS | Inputs: population, total energy consumption, and total renewable energy capacity Outputs: GDP, total energy production FTOPSIS: availability of resource, energy security, technological infrastructure, economic stability, social acceptance |

| Efficiency assessment of electricity generation from renewable and non-renewable energy sources using Data Envelopment Analysis (2021) [31] |

126 countries from 2000 to 2016 | BCC model | Inputs: renewable and non-renewable energy sources generation capacity Outputs: Power generation, CO2 emissions avoided |

| Environmental efficiency of disaggregated energy R&D expenditures in OECD: a bootstrap DEA approach (2021) [32] | 26 OECD countries | Bootstrap IO CCR DEA | Inputs: six different energy R&D expenditure indicators in 2015 Outputs: CO2 emission per capita |

| Dual Efficiency and Productivity Analysis of Renewable Energy Alternatives of OECD Countries (2021) [5] | Selected OECD countries in 2012, 2014, and 2016 | OO BCC model and MI | Inputs: investment in RE sources Outputs: electricity generation, EPI, the proportion of the population with access to clean fuels and technology for cooking |

| The efficiency of wind power companies in electricity generation (2021) [33] | 78 wind power companies in 12 selected European countries in 2014 | IO SBM VRS- DEA | Inputs: wind turbine power and number, fuel, tangible fixed assets, receivables and other assets, cash and cash equivalents Outputs: electricity production, EBITDA |

| A cross-European efficiency assessment of offshore wind farms: A DEA approach (2020) [34] | 71 offshore wind farms across 5 countries in 2018 | CCR DEA with sensitivity analysis | Inputs: number of turbines, cost, distance to shore, area Outputs: connectivity, generated electricity, water depth |

| Eco-efficiency assessment for some European countries using slacks-based measure data envelopment analysis (2020) [35] | 17 European countries from 2013 to 2017 | SBM DEA with undesirable outputs model and MI | Inputs: energy consumption, labour productivity, the share of renewable energy in energy consumption, gross capital formation productivity Outputs: GDP per capita, CO2 per capita |

| Eco-efficiency assessment of the electricity sector: evidence from 28 European Union countries (2020) [36] | 28 EU countries 2010 and 2014. | DEA Directional Distance Function model | Inputs: labour, capital, GHG, acidifying gases, ozone Precursors Outputs: GVA |

| A global level analysis of environmental energy efficiency: an application of data envelopment analysis (2020) [37] | 149 economies categorized into low-, middle- and high-income from 1993 to 2013 | IO and OO DEA with and without undesirable output and directional distance function | Inputs: labour, capital, energy Outputs: GDP, CO2 |

| Renewable Energy Utilization Analysis of Highly and Newly Industrialized Countries Using an Undesirable Output Model (2020) [38] | 17 countries highly and newly industrialised from 2013 to 2018 | DEA with undesirables preceded by Grey Prediction Model | Inputs: total renewable energy capacity, labour force, total energy consumption Outputs: CO2, GDP |

| Across-country evaluation of energy efficiency from the sustainable development perspective (2019) [39] | 132 countries from 2007 to 2014 | MinSum DEA | Inputs: GDP per unit of energy use, renewable energy consumption Outputs: GDP, CO2 emissions per GDP |

| Cost-efficiency benchmarking of European renewable electricity support schemes (2018) [40] | 25 EU member states and Norway from 2000 to 2015 | CCR model | Inputs: PV fee, wind fee, LCOE PV, LCOE wind Outputs: PV share, Wind share, REs share |

| Renewable and sustainable energy efficiency: An analysis of Latin American countries (2018) [41] | 156 Latin American countries from 1991 to 2013 | SBM VRS DEA with window analysis | Inputs: labour, capital, energy consumption Outputs: GDP, CO2 |

| Energy efficiency and its determinants: An empirical analysis (2018) [42] | 20 of the largest producers of renewable energy from 2009 to 2013 | BCC DEA and truncated regression | Input: primary energy consumption, capital, labour Output: GDP Regression: renewable energy consumption, GVA per capita, population density |

| Energy security and renewable energy efficiency in EU (2018) [43] | 14 EU countries from 2004 to 2014 | DEA and sequential Malmquist-Luenberger index | Input: deployed renewables Output: increase in the share of RE in total electricity generation Undesirable outputs: coal products, oil products and natural gas |

| Title (Year) | DMU | DEA model | Analysis Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| A robust network DEA model for sustainability assessment: an application to Chinese provinces (2022) [51] | 30 Chinese regions during 2000-2012 | multiplicative two-stage relational NDEA | capital, labour, energy, GDP, CO2, SO2 |

| Policy, technical change, and environmental efficiency: Evidence of China's power system from dynamic and spatial perspective (2022) [52] | 30 Chinese provinces from 2011 to 2020 | DNSBM-DDF model and global MPI | feed-in tariff, renewable portfolio standard CO2, SO2, NOx, and line loss |

| The dynamics of Indian energy mix: a two-phase analysis (2022) [47] | 18 Indian states from 2008 to 2016 | two phases consist of two stages serial NDEA and regression | renewable and conventional capacities, generation from RES and conventional sources, length of transmission lines, technical and commercial losses, agricultural-, residential-, and industrial consumption, state GDP per capita |

| Analysis of inter-temporal change in the energy and CO2 emissions efficiency of economies: a two divisional network DEA approach (2020) [53] | Iran’s Electricity Distribution Network | two stage NDEA | labour, capital, energy consumption, GDP, CO2, the total population |

| China’s provincial eco-efficiency and its driving factors—based on network DEA and PLS-SEM Method (2020) [54] | 30 Chinese regions in 1996 -2015 | two-stage serial NDEA and PLS-SEM | labour, asset, energy consumption, land used, water, GDP, wastewater, exhaust, SO2, investment in pollution control, solid waste utilization, wastewater treatment, greening rate |

| Developing a network DEA model for sustainability analysis of Iran’s electricity distribution network (2020) [55] | Iran’s electricity distribution network | serial and parallel NDEA | fuel, staff, import, export, sale to big industry, electricity generated, electricity distributed, loss in transmission, purchase, network length, service area, sale to customers |

| Dynamic linkages among economic development, energy consumption, environment, and health sustainable in EU and Non-EU Countries (2019) [56] | 8 EU and 53 non-EU countries from 2010 to 2014 | two-stage meta-frontier dynamic serial NDEA | labour, renewable and non-renewable energy consumption, assets, GDP, health expenditure, survival rate, tuberculosis rate, CO2, PM2.5, mortality rates |

| Energy efficiency and health efficiency of old and new EU member states (2020) [57] | 15 old and 13 new EU states from 2010 to 2014 | two-stage meta-frontier dynamic serial NDEA | labour, renewable and non-renewable energy consumption, assets, GDP, health expenditure, survival rate, tuberculosis rate, CO2, PM2.5, mortality rates |

| Environmental assessment of European Union countries (2019) [58] | 28 EU countries 2006–2013 | dynamic DEA | labour, capital, energy consumption, GHE, SOx, GDP, GCF |

| Research on new and traditional energy sources in OECD countries (2019) [59] | 35 OECD countries | dynamic SBM DEA | labour, energy consumption, new energy consumption, GDP, CO2, PM2.5, fixed assets |

| Energy and CO2 emissions efficiency of major economies: a network DEA approach (2018) [60] | major economies | SBM two stages NDEA | energy resources, economic outputs, energy consumption, CO2 |

| Economic and technical efficiency of the biomass industry in China: a network data envelopment analysis model involving externalities (2017) [61] | 31 Chinese provinces in 2012 | NDEA model with undesirable outputs | operational cost, forest residues, organic waste, rural power, fertilizers, agricultural machinery, commercial and residential power, agricultural production, rural power, pollutants, agricultural and straw residues |

| Title | DMU | DEA model | Analysis Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| A novel two-stage multicriteria decision-making approach for selecting solar farm sites: A case study (2024) [62] | 39 potential cities in the Baltic region | DEA and TOPSIS | temperature, wind speed, humidity, precipitation, and air pressure as inputs and sunshine hours, elevation, and irradiation and six evaluation criteria to prioritize the locations |

| Benchmarking performance of photovoltaic power plants in multiple periods (2023) [63] | 3 PV power plants in multiple periods | multi-period DEA | solar insolation, daily sun-hours, temperature, installation cost, installed capacity |

| Analysis of dynamic renewable energy generation efficiency and its influencing factors considering cooperation and competition between decision-making units: a case study of China [64] | China's provinces | DEA cross-efficiency | cumulative installed capacity, annual equipment utilisation hours, electricity consumption of power generation companies, electricity generation |

| New approach to prioritize wind farm sites by data envelopment analysis method: A case study (2023) [65] | 14 offshore sites of the Moroccan seas for 2016–2020 | DEAM (supper-efficiency DEA model) | water depth, distance to coast, accessibility, maximum wave height, maximum wind speed, wind power density |

| A two-stage approach of DEA and AHP in selecting optimal wind power plants (2023) [66] | 12 locations in Vietnam | DEA (CCR-I, CCR-O, BCC-I, BCC-O, SBM-I-O, SMB-O-C) and AHP | DEA: frequency of natural disasters, land cost, wind blow, population, quantity of proper geological and topographical area AHP: location characteristic, technical, economic, social, environmental |

| A novel integrated approach for ranking solar energy location planning: a case study (2021) [67] | 10 provinces in Canada | hybrid approach composed of data (DEA), balanced scorecard (BSC) and game theory (GT) | cost of construction, income, electricity generated by the plant and electricity generated by the panel, amount of pollution |

| Techno-enviro assessment and ranking of Turkey for use of home-scale solar water heaters (2021) [68] | 2 types of solar water heaters for 45 stations in Turkey | BCC and additive DEA model | total annual irradiation, diffuse radiation percentage, cold water temperature, total solar fraction, solar contribution to heating, CO2 emissions avoided, boiler energy to heating and to DHW |

| A two-stage multiple criteria decision making for site selection of solar photovoltaic (pv) power plant: a case study in Taiwan (2021) [69] | 20 potential cities and counties of Taiwan | DEA (CCR-I, CCR-O, BCC-I, BCC-O, SBM-I-O, SMB-O-C) and AHP | DEA: temperature, wind speed, humidity, precipitation, air pressure, sunshine hours, insolation AHP: site characteristics, technical, economic, social, environmental |

| Performance evaluation of solar PV power plants in Taiwan using data envelopment analysis (2021) [70] | solar PV power plants in Taiwan. | epsilon-based DEA | surface area, number of modules, ambient temperature, plant capacity, PV module temperature, irradiation, generated energy |

| Location optimization of wind plants using DEA and fuzzy multi-criteria decision making: a case study in Vietnam (2021) [71] | 20 potential provinces in Vietnam | DEA, FAHP, FWASPAS | DEA: land cost, intensity of natural disasters occurrence, wind power density, quantity of proper geological areas, population FAHP: technical, economic, social/political, environmental |

| Factors affecting the efficiency of wind power in the European Union countries (2019) [22] | 27 EU countries | two-stage bias-corrected DEA | installed wind power capacity, average wind power density, wind-generated electricity, and additional aspects: environmental, economic and energy security |

| A novel multi-period double frontier network DEA to sustainable location optimization of hybrid wind-photovoltaic power plant with real application (2018) [72] | 22 Iran provinces | double frontier (optimistic and pessimistic) parallel single- and multi-period NDEA | land cost, HDI, distance to high consumptions province, wind speed, population, electricity consumptions, sunny hours, above sea level |

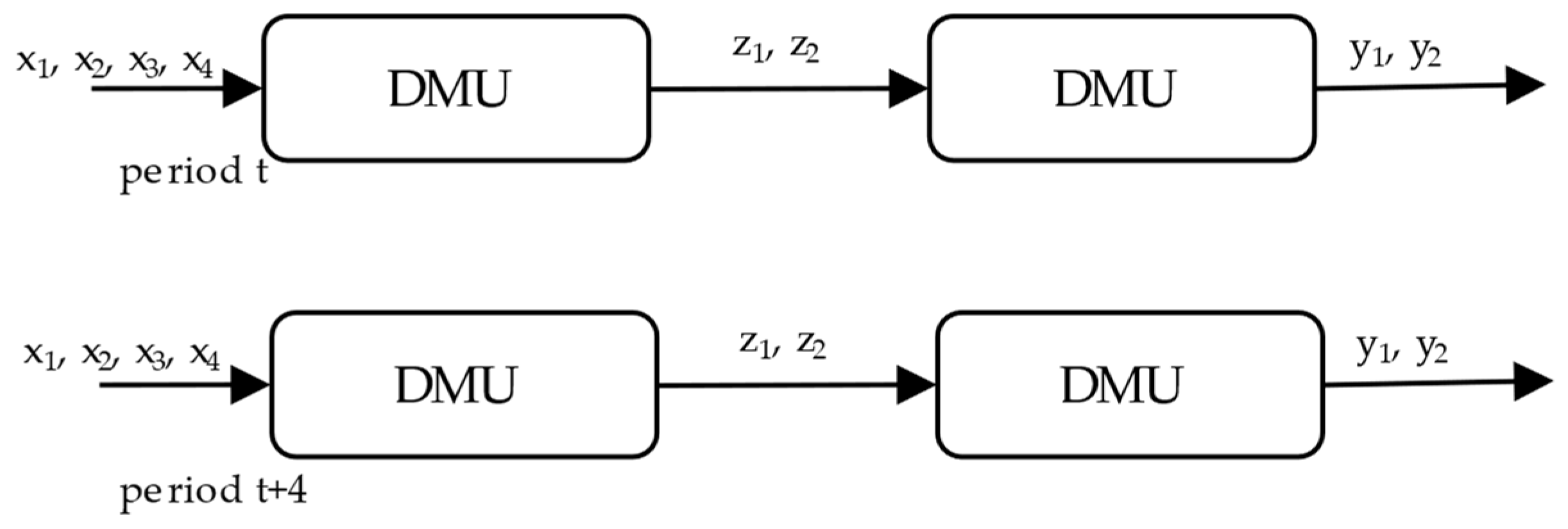

| Variable | Description, source | Unit, year | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| x1 | Mean wind speed | m/s (data for 10% windiest area) | [90] |

| x2 | GHI | kWh/m2/day | [91]* |

| x3 | Population | million people, 2018-2022 | [92,93] |

| x4 | Land area | square thousand km, 2021 | [94] |

| z1 | Wind energy capacity | MW, 2018, 2022 | [95] |

| z2 | Solar PV capacity | MW, 2018-2022 | [95] |

| y1 | Wind energy generation | GWh per year, 2018-2022 | [96] |

| y2 | Solar power generation | TWh per year, 2018-2022 | [97] |

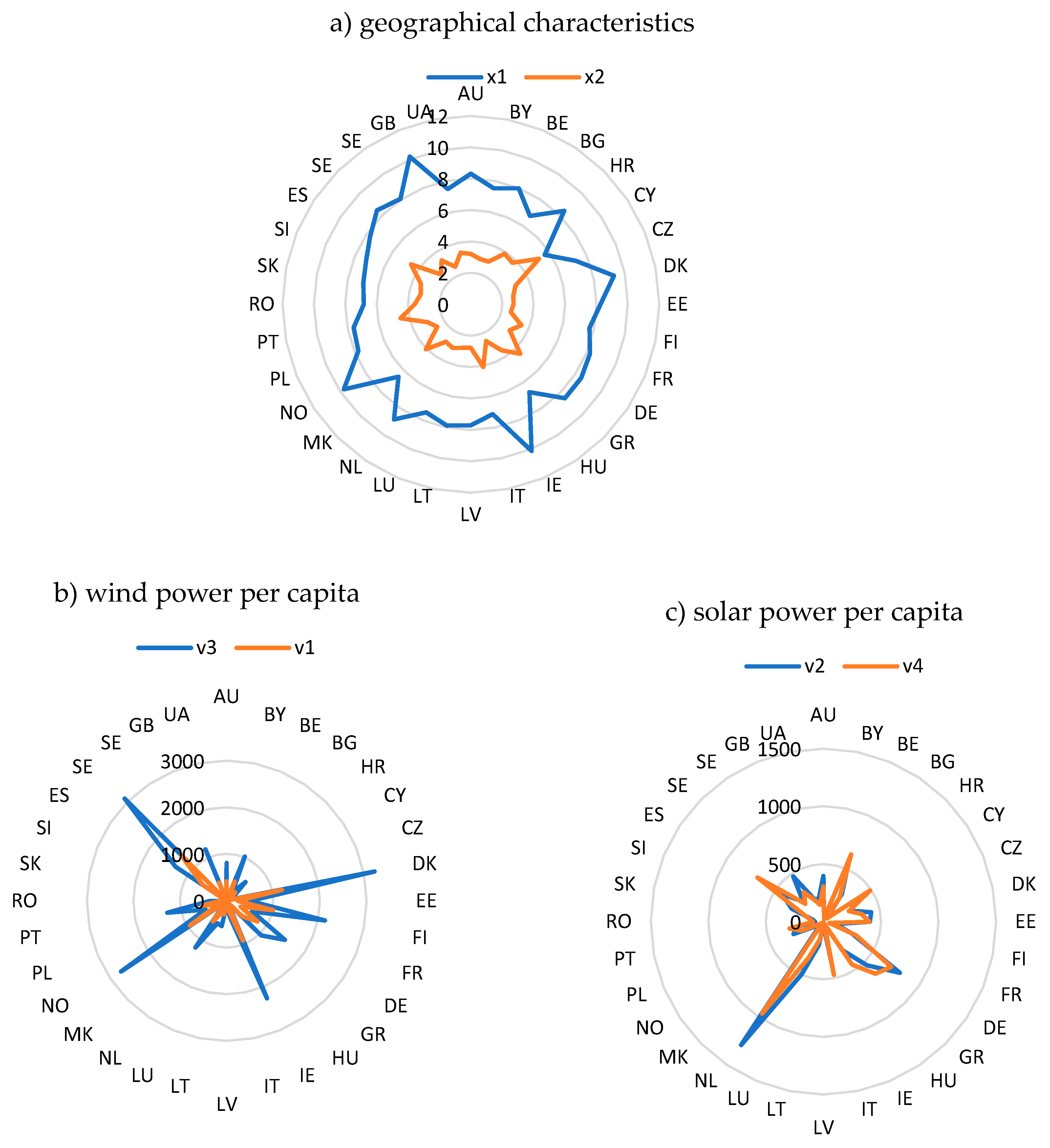

| v1 | Wind capacity per capita | W | |

| v2 | PV capacity per capita | W | |

| v3 | Wind energy generation per capita | kW | |

| v4 | Solar power generation per capita | kW |

| Population | Land area | Mean Wind Speed | GHI | Wind capacity per capita | Solar PV capacity | Wind energy generation per capita | Wind energy generation per capita | Wind capacity | Solar PV capacity | Wind energy generation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| Land area | 0.683 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| Mean Wind Speed | 0.203 | 0.154 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| GHI | 0.029 | -0.027 | -0.593 | 1.000 | |||||||

| Wind capacity per capita | 0.078 | 0.283 | 0.633 | -0.340 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Solar PV capacity per capita | 0.260 | -0.104 | 0.114 | 0.047 | 0.139 | 1.000 | |||||

| Wind energy generation per capita | 0.029 | 0.242 | 0.678 | -0.361 | 0.985 | 0.089 | 1.000 | ||||

| Solar power generation per capita | 0.334 | -0.005 | 0.006 | 0.283 | 0.121 | 0.920 | 0.064 | 1.000 | |||

| Wind capacity | 0.823 | 0.508 | 0.328 | -0.063 | 0.398 | 0.374 | 0.327 | 0.431 | 1.000 | ||

| Solar PV capacity | 0.826 | 0.416 | 0.168 | 0.008 | 0.187 | 0.573 | 0.108 | 0.584 | 0.910 | 1.000 | |

| Wind energy generation | 0.819 | 0.494 | 0.406 | -0.098 | 0.428 | 0.346 | 0.372 | 0.403 | 0.985 | 0.856 | 1.000 |

| Solar power generation | 0.853 | 0.484 | 0.134 | 0.112 | 0.185 | 0.521 | 0.105 | 0.603 | 0.914 | 0.973 | 0.865 |

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. dev. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| x1 | 5.66 | 10.18 | 7.90 | 1.01 |

| x2 | 2.53 | 5.21 | 3.33 | 0.68 |

| x3 | 0.65 | 83.37 | 18.12 | 22.32 |

| x4 | 2.57 | 579.40 | 170.30 | 166.59 |

| z1 | 3.00 | 66315.00 | 7490.81 | 13064.71 |

| z2 | 56.00 | 66554.00 | 7101.69 | 12782.09 |

| y1 | 5.00 | 125287.00 | 16167.99 | 26724.79 |

| y2 | 0.01 | 58.98 | 7.05 | 12.34 |

| v1 | 0.71 | 1379.90 | 377.42 | 372.40 |

| v2 | 26.88 | 1286.15 | 310.56 | 254.56 |

| v3 | 0.89 | 3230.37 | 860.08 | 916.97 |

| v4 | 5.40 | 958.21 | 292.85 | 233.90 |

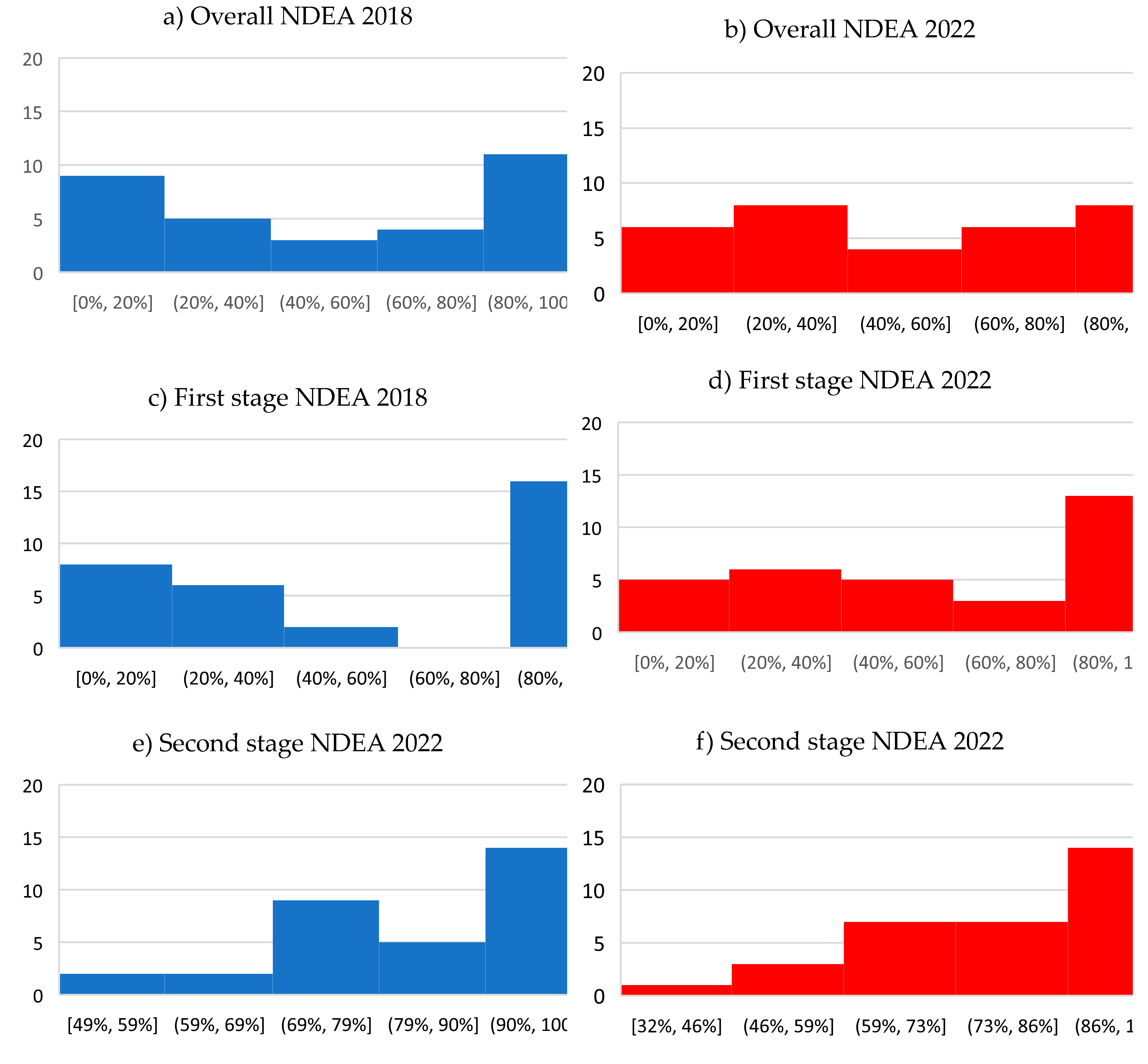

| Country | Two-stage NDEA 2018 | Two-stage NDEA 2022 | Malmquist index | |||||||||

| One stage DEA 2018 | One stage DEA 2022 | First stage | Second stage | Overall | First stage | Second stage | Overall | catch-up | frontier-shift | index | ||

| AU | Austria | 41.6% | 43.1% | 39.2% | 78.2% | 30.7% | 48.5% | 63.6% | 30.9% | 1.01 | 1.57 | 1.58 |

| BY | Belarus | 4.7% | 5.5% | 2.3% | 50.5% | 1.2% | 2.2% | 63.8% | 1.4% | 1.20 | 1.54 | 1.84 |

| BE | Belgium | 100.0% | 97.3% | 97.3% | 86.7% | 84.3% | 77.0% | 96.0% | 74.0% | 0.88 | 1.64 | 1.44 |

| BG | Bulgaria | 43.2% | 40.2% | 22.7% | 84.1% | 19.1% | 21.5% | 75.5% | 16.2% | 0.85 | 1.44 | 1.22 |

| HR | Croatia | 14.2% | 18.9% | 5.7% | 73.4% | 4.2% | 7.1% | 60.5% | 4.3% | 1.03 | 2.12 | 2.18 |

| CY | Cyprus | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 79.6% | 79.6% | 0.80 | 1.12 | 0.89 |

| CZ | Czechia | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 49.9% | 68.6% | 34.2% | 0.34 | 2.87 | 0.98 |

| DK | Denmark | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 70.1% | 70.1% | 100.0% | 75.8% | 75.8% | 1.08 | 1.49 | 1.61 |

| EE | Estonia | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 71.8% | 71.8% | 100.0% | 75.8% | 75.8% | 1.06 | 0.86 | 0.91 |

| FI | Finland | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 50.7% | 52.8% | 0.53 | 0.91 | 0.48 |

| FR | France | 33.2% | 43.1% | 30.1% | 100.0% | 32.1% | 37.2% | 100.0% | 37.2% | 1.16 | 1.34 | 1.55 |

| DE | Germany | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| GR | Greece | 70.2% | 73.1% | 43.1% | 96.6% | 41.7% | 58.9% | 89.5% | 52.7% | 1.26 | 1.42 | 1.80 |

| HU | Hungary | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 71.1% | 71.1% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 1.41 | 1.01 | 1.42 |

| IE | Ireland | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| IT | Italy | 97.8% | 87.8% | 47.6% | 86.5% | 41.2% | 50.0% | 80.4% | 40.2% | 0.98 | 1.74 | 1.70 |

| LV | Latvia | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 1.00 | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| LT | Lithuania | 36.1% | 39.8% | 14.5% | 76.7% | 11.1% | 39.3% | 56.9% | 22.4% | 2.01 | 2.04 | 4.09 |

| LU | Luxembourg | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 75.7% | 75.7% | 100.0% | 65.6% | 65.6% | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.74 |

| NL | Netherlands | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 83.1% | 83.1% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 1.20 | 1.16 | 1.39 |

| MK | North Macedonia | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| NO | Norway | 39.7% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 59.8% | 59.8% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 25.0% | 0.25 | 73.09 | 18.28 |

| PL | Poland | 27.9% | 36.0% | 5.4% | 48.7% | 2.6% | 33.4% | 83.7% | 27.9% | 10.62 | 1.47 | 15.63 |

| PT | Portugal | 78.9% | 64.6% | 21.1% | 100.0% | 21.1% | 36.3% | 99.3% | 36.0% | 1.71 | 1.73 | 2.96 |

| RO | Romania | 61.0% | 59.7% | 38.5% | 95.4% | 36.7% | 24.7% | 96.4% | 23.8% | 0.65 | 1.60 | 1.04 |

| SK | Slovakia | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| SI | Slovenia | 28.5% | 27.0% | 0.5% | 69.5% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 66.2% | 0.3% | 0.77 | 1.23 | 0.95 |

| ES | Spain | 81.4% | 95.2% | 40.0% | 100.0% | 40.0% | 64.3% | 100.0% | 64.3% | 1.60 | 1.37 | 2.20 |

| SE | Sweden | 100.0% | 100.0% | 18.9% | 85.2% | 16.1% | 74.1% | 79.9% | 59.2% | 3.68 | 2.02 | 7.46 |

| SE | Switzerland | 45.5% | 33.1% | 2.3% | 60.6% | 1.4% | 2.4% | 61.7% | 1.5% | 1.03 | 1.20 | 1.24 |

| GB | UK | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| UA | Ukraine | 5.3% | 22.0% | 3.7% | 75.5% | 2.8% | 10.7% | 32.2% | 3.4% | 1.24 | 1.23 | 1.53 |

| Average | 72.2% | 74.6% | 60.4% | 84.4% | 53.7% | 63.7% | 81.9% | 55.6% | ||||

| Overall NDEA 2018 (X→Z→Y) | Overall NDEA 2022 (X→Z→Y) | DEA 2022 (X→Y) | |

| DEA 2018 (X→Y) | 82.7% | 93.4% | |

| DEA 2022 (X→Y) | 83.9% | ||

| Overall NDEA 2018 (X→Z→Y) | 84.6% | ||

| First stage NDEA 2018 (X→Z→Y) | First stage NDEA 2022 (X→Z→Y) | DEA 2022 (X→Z) | |

| DEA 2018 (X→Z) | 84.3% | 94.8% | |

| DEA 2022 (X→Z) | 92.4% | ||

| First stage NDEA 2018 (X→Z→Y) | 89.0% | ||

| Second stage NDEA 2018 (X→Z→Y) | Second stage NDEA 2022 (X→Z→Y) | DEA 2022 (Z→Y) | |

| DEA 2018 (Z→Y) | 49.8% | 54.0% | |

| DEA 2022 (Z→Y) | 51.8% | ||

| Second stage NDEA 2018 (X→Z→Y) | 54.1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).