Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Animals

4.3. Liver Perfusion

4.4. Statistical Analysis

4.5. Glucose Determination

4.6. Liver Glycogen

4.7. Phosphorylation of Glycogen Phosphorylase

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bartok, A.; Weaver, D.; Golenar, T.; Nichtova, Z.; Katona, M.; Bansaghi, S.; Alzayady, K.J.; Thomas, V.K.; Ando, H.; Mikoshiba, K.; et al. IP3 receptor isoforms differently regulate ER-mitochondrial contacts and local calcium transfer. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, M.P.; Schug, Z.T.; Booth, D.M.; Yule, D.I.; Mikoshiba, K.; Hajnoczky, G.; Joseph, S.K. Metabolic adaptation to the chronic loss of Ca2+ signaling induced by KO of IP3 receptors or the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 101436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, P.; Deb, B.K.; Arige, V.; Musthafa, T.; Malik, S.; Yule, D.I.; Taylor, C.W.; Hasan, G. Regulation of store-operated Ca2+ entry by IP3 receptors independent of their ability to release Ca2+. eLife 2023, 12, e80447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, L.C.; Kawaguchi, S.; Collin, T.; Jalil, A.; del Pilar Gomez, M.; Nasi, E.; Marty, A.; Llano, J. Influence of spatially segregated IP3-producing pathways on spike generation and transmitter release in Purkinje cell axons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 11097–11108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bylund, D.B. Subtypes of α1- and α2-adrenergic receptors. FASEB J. 1992, 6, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garro, M.A.; Urizar, E.; Lazkano, A.; Zubillaga, E.; Querejeta, R. The α1A adrenergic receptor inhibits type 5 adenylyl cyclase in HL-1 cardiomyocytes. Clin. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2018, 1, 1003. [Google Scholar]

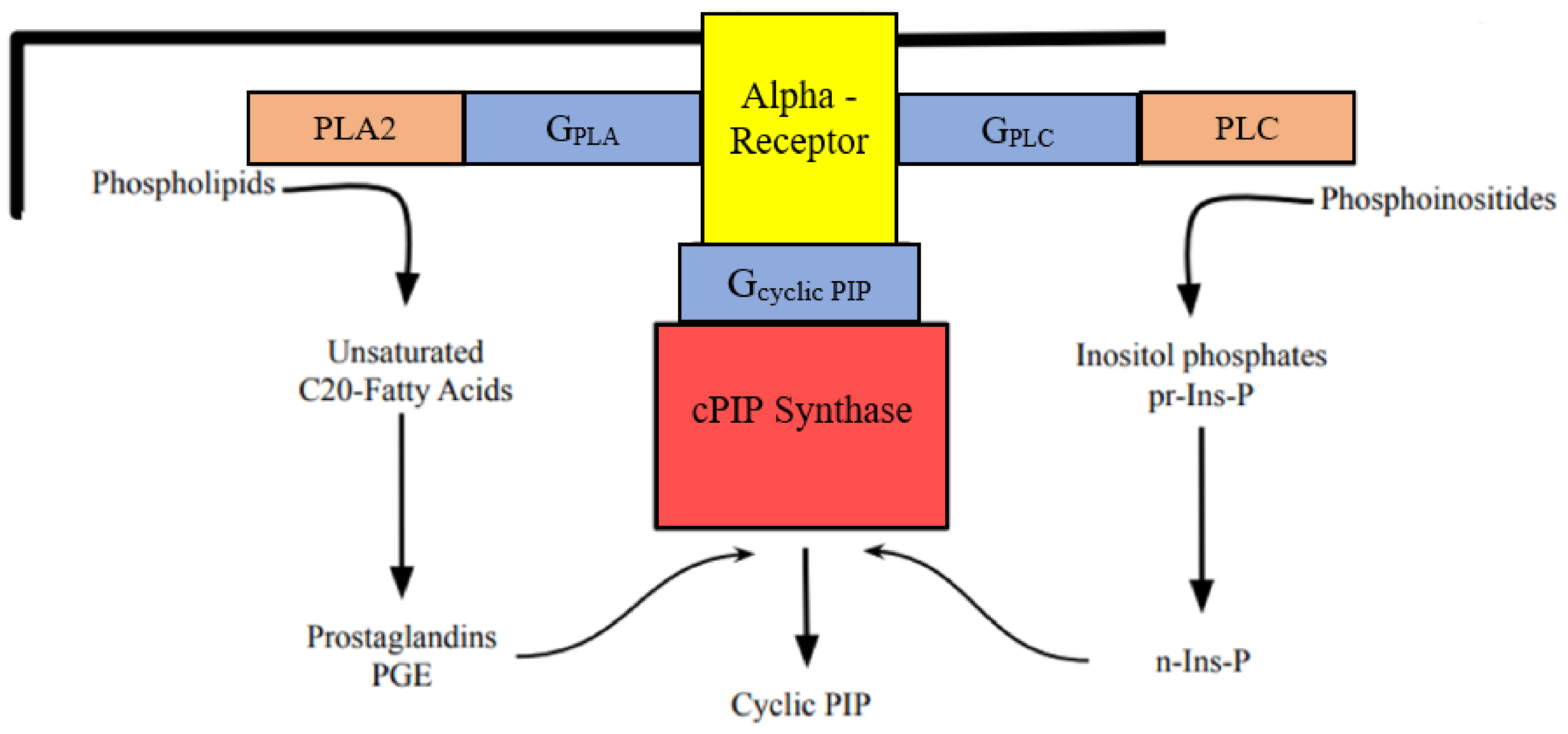

- Burch, R.M.; Luini, A.; Axelrod, J. Phospholipase A2 and phospholipase C are activated by distinct GTP-binding proteins in response to a1-adrenergic stimulation of FRTL5 thyroid cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA 1986, 83, 7201–7205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felder, C.S.; Williams, H.L.; Axelrod, J. A transduction pathway associated with receptors coupled to the inhibitory guanine nucleotide binding protein Gi that amplifies ATP-mediated arachidonic acid release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 6477–6480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesek, F.A. Alpha2-adrenergic receptors activate phospholipase C in renal epithelial cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996, 50, 407–414. [Google Scholar]

- Fain, J.N.; Garcia-Sainz, J.A. Role of phosphatidylinositol turnover in alpha1 and of adenylate cyclase inhibition in alpha2 effects of catecholamines. Life Sci. 1980, 26, 1183–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

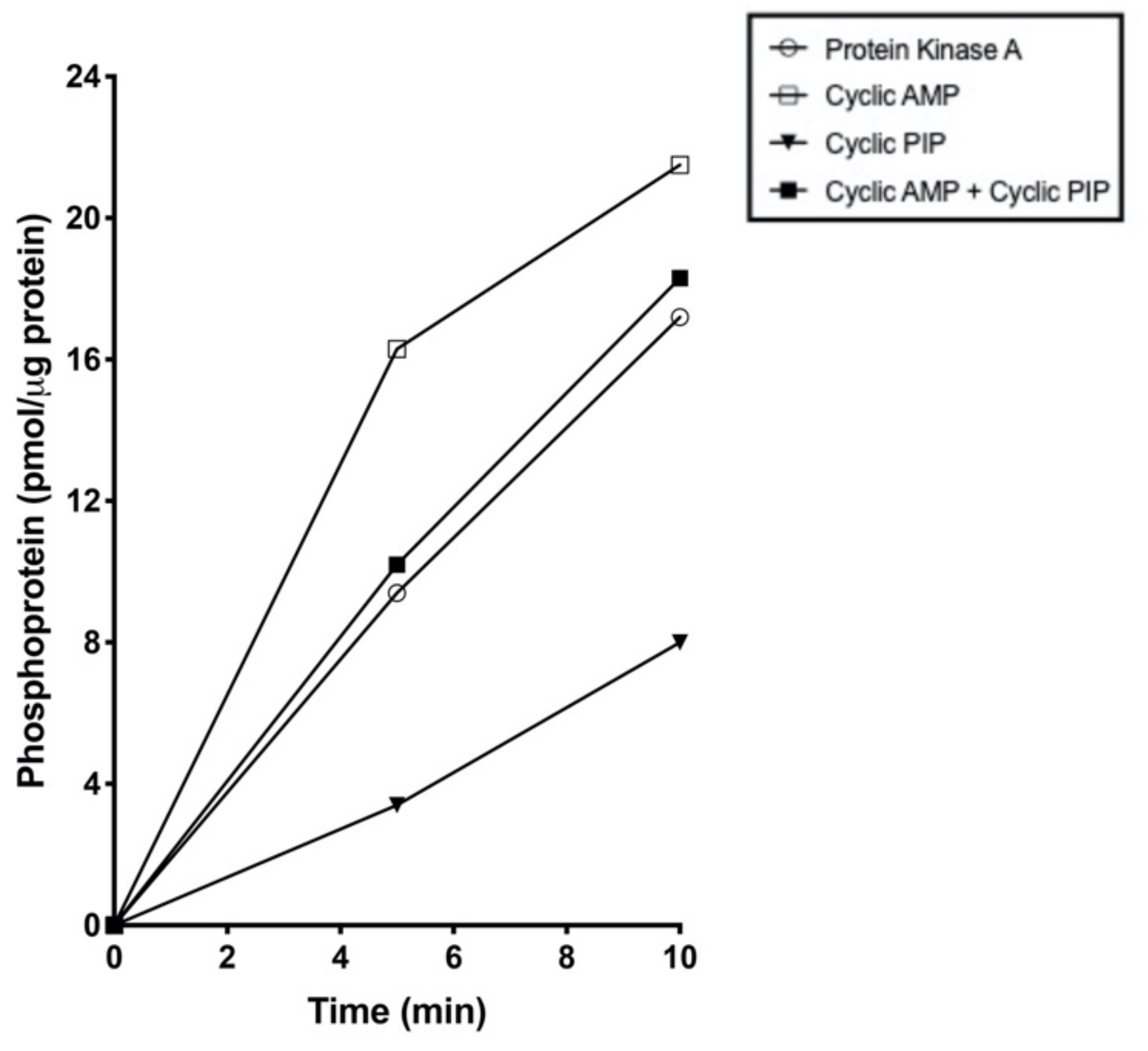

- Wasner, H.K.; Salge, U.; Gebel, M. The endogenous cyclic AMP antagonist, cyclic PIP: its ubiquity, hormone stimulated synthesis and identification as prostaglandylinositol cyclic phosphate. Acta. Diabetol. 1993, 30, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasner, H.K. Prostaglandylinositol cyclic phosphate, the natural antagonist to cyclic AMP. IUBMB Life 2020, 72, 2282–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gypakis, A.; Adelt, S.; Lemoine, H.; Vogel, G.; Wasner, H.K. Activated inositol phosphate, substrate for synthesis of prostaglandylinositol cyclic phosphate (cyclic PIP)–the key for the effectiveness of inositol feeding. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25(3), 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, N.G.; Montague, W. Studies on the mechanism of inhibition of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion by noradrenaline in rat islets of Langerhans. Biochem. J. 1985, 226, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasner, H.K.; Lemoine, H.; Junger, E.; Leßmann, M.; Kaufmann, R. Prostaglandylinositol cyclic phosphate, a new second messenger. In Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes, Lipoxins and PAF. Bailey, J.M., Ed., Plenum Press: New York, USA, 1991, pp. 153–168.

- Wasner, H.K.; Weber, S.; Partke, H.J.; Amini-Hadi-Kiashar, H. Indomethancin treatment causes loss of insulin action in rats: Involvement of prostaglandins in the mechanism of insulin action. Acta Diabetol. 1994, 31, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flechtner-Mors, M.; Jenkinson, C.P.; Alt, A.; Biesalski, H.K.; Adler, G.; Ditschuneit, H.H. Sympathetic regulation of glucose uptake by the α1-adrenoceptor in human obesity. Obes. Res. 2004, 12, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.N.; Cassagnol, M. Alpha-adrenergic receptors. In: StatPearls, Treasure Island, Fl; StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available online: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539830/.

- Wasner, H.K.; Gebel, M.; Hucken, S.; Schaefer, M.; Kincses, M. Two separate mechanisms for activation of cyclic PIP synthase: By a G protein or by protein tyrosine phosphorylation. Biol. Chem. 2000, 381, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanemaru, K.; Nakamura, Y. Activation mechanisms and diverse functions of mammalian phospholipase C. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boi, R.; Ebefors, K.; Henricsson, M.; Boren, J.; Nystroem, J. Modified lipid metabolism and cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation in mesangial cells under pro-inflammatory conditions. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Ilies, M.A. The phospholipase A2 superfamily: structure, isozymes, catalysis, physiologic and pathologic roles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabral, D.; van den Bogaart, G. The roles of phospholipase A2 in phagocytes. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 673502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Zhou, Q.; Labroska, V.; Qin, S.; Darbalaei, S.; Wu, Y.; Yuliantie, E.; Xie, L.; Tao, H.; Cheng, J.; et al. G protein-coupled receptors: structure- and function-based drug dis-covery. Sig. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myagmar, B.-E.; Ismaili, T.; Swigart, P.M.; Raghunathan, A.; Baker, A.J.; Sahdeo, S.; Blevitt, J.M. Milla, M.E.; Simpson, P.C. Coupling of Gq signaling is required for cardioprotection by an alpha-1A-adrenergic receptor agonist. Circulation Research 2019, 125, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostenis, E.; Pfeil, E.M.; Annala, S. Heterotrimeric Gq proteins as therapeutic targets? J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 5206–5215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durkee, C.A.; Cavelo, A.; Lines, J.; Kofuji, P.; Aguilar, J.; Araque, A. Gi/o protein-coupled receptors inhibit neurons but activate astrocytes and stimulate gliotransmission. Glia 2019, 67, 1076–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, M.T.; Dadi, P.K.; Zaborska, K.E.; Nakhe, A.Y.; Schaub, C.M.; Dobson, J.R.; Wright, N.M.; Lynch, J.C.; Scott, C.F.; Robison, L.D.; et al. Gi/o protein-coupled receptor inhibition of beta-cell electrical excitability and insulin secretion on Na+/K+ ATPase activation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, T.W.; Carroll, R.C.; Peralta, E.G. Heterotrimeric G proteins containing Gαi3 regulate multiple effector enzymes in the same cell. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 29565–29570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, V.J.; Lu, R.; Wu, L.; Garcia Macia, M.; Koba, W.R.; Chi, Y.; Singh, R.; Schwartz, G.J.; Schuster, V.L. Inhibiting the prostaglandin transporter PGT induces non-canonical thermogenesis at thermoneutrality. bioRxiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, V.L. Molecular mechanisms of prostaglandin transport. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1998, 60, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.P.; Griffiths, A.L. Lui, S.; Sabar, U.J.; Farrar, D.; O’Donovan, P.J.; Woodward, D.F.; Marshall, K.M. Distribution and function of prostaglandin E2 receptors in mouse uterus translational value for human reproduction. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2020, 373, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Lin, P.; Zhu, J.; Jeschke, U.; von Schoenfeldt, V. Multiple roles of prostaglandin E2 receptors in female reproduction. Endocrines 2020, 1, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Gao, K.; Nie, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Ren, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, Q.; Huang, J.; Liu, L.; et al. Structures of human prostaglandin F2α receptors reveal the mechanism of ligand and G protein selectivity. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasner, H.K. Insulin resistance develops due to an imbalance in the synthesis of cyclic AMP and the natural cyclic AMP antagonist prostaglandylinositol cyclic phosphate (cyclic PIP). Stresses 2023, 3, 762–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, T.R.; Khan, S.A.; Neidhart, M.B.; Masters, B.M.; Zhao, V.K.; Kim, Y.K.; McGill Percy, K.C.; Woo, J.-A.A. The multifaceted functions of β-arrestins and their therapeutic potential in neurodegenerative diseases. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogriopoulos, N.A.; Lopez-Sanchez, I.; Lin, C.; Ngo, T.; Midde, K.K.; Roy, S.; Aznar, N.; Murray, F.; Garcia-Marcos, M.; Kufareva, I.; et al. Receptor tyrosine kinases activate heterotrimeric G proteins via phosphorylation within the interdomain cleft of Gαi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 28763–28774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

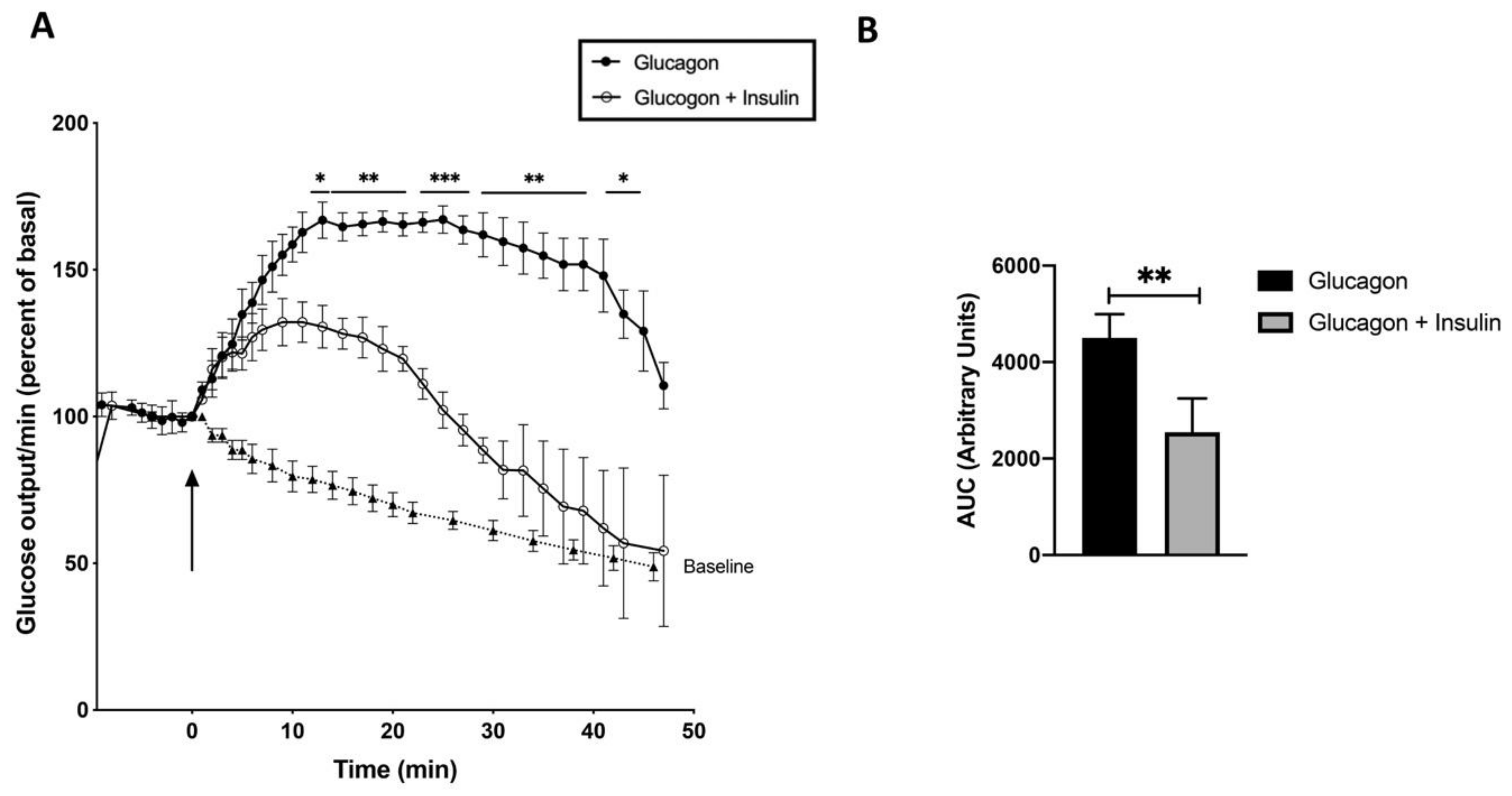

- Charest, R.; Blackmore, P.F.; Berthon, B.; Exton, J.H. Changes in free cytosolic Ca2+ in hepatocytes following α1-adrenergic stimulation. J. Biol. Chem. 1983, 258, 8769–8773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, G.A.; Butcher, R.W.; Sutherland, E.W. Cyclic AMP.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

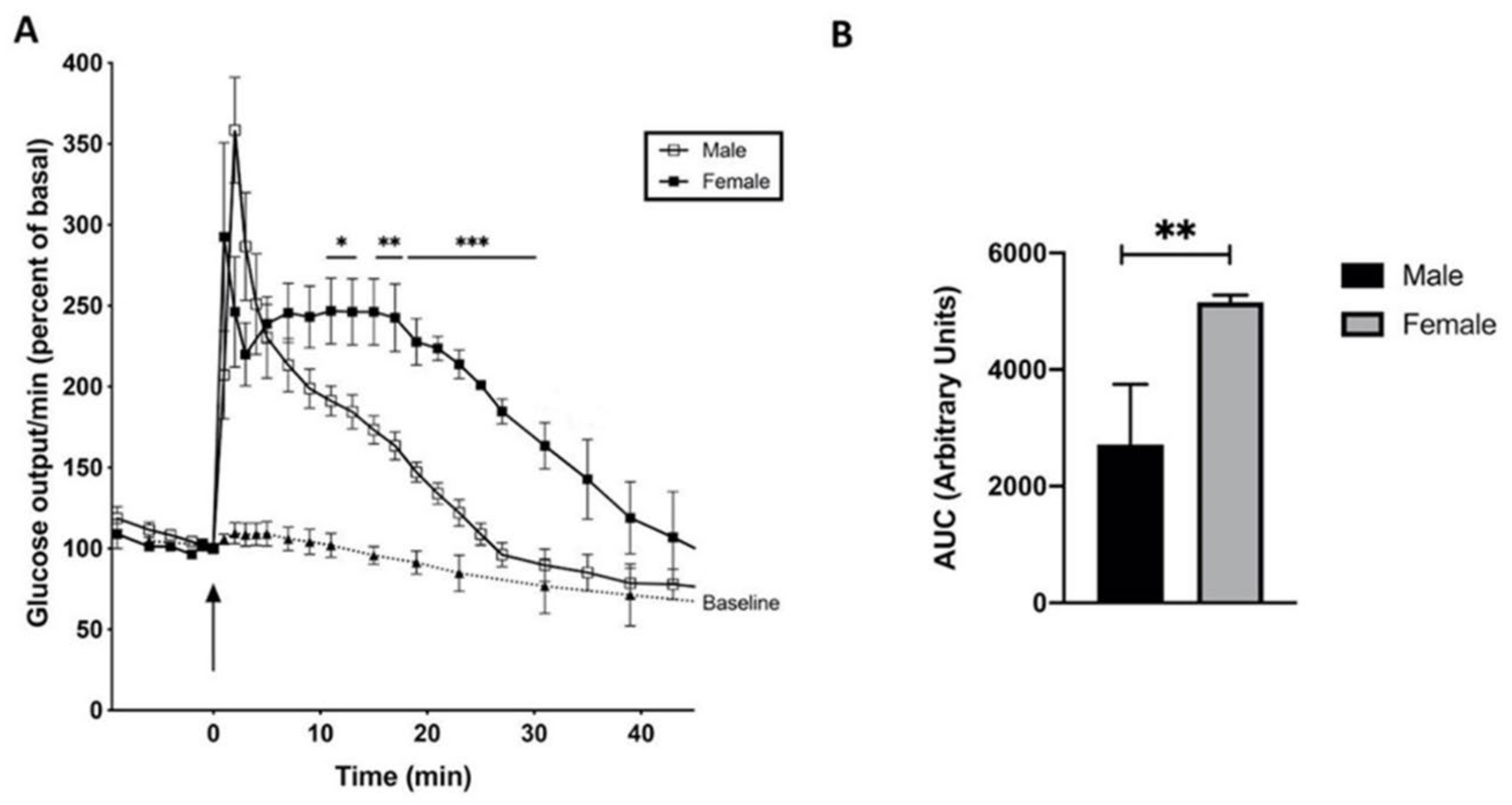

- Studer, R.K.; Borle, A.B. Differences between male and female rats in the regulation of the hepatic glycogenolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257, 7987–7993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pershadsingh, H.A.; Shade, D.L.; Delfert, D.M.; McDonald, J.M. Chelation of intracellular calcium blocks insulin action in the adipocyte. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. US 1987, 84, 1025–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruton, J.D.; Katz, A.; Westerblad, H. Insulin increases near-membrane but not global Ca2+ in isolated skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 3281–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmeyer, L.M.G.; Meyer, F.; Haschke, R.H.; Fischer, E.H. Control of phosphorylase activity in a muscle glycogen particle. II. Activation by calcium. J. Biol. Chem. 1970, 245, 6649–6656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brautigan, D.L. Phosphorylase phosphatase and flash activation of skeletal muscle glycogen phosphorylase–a tribute to Edmond, H. Fischer. IUBMB Life 2023, 75, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

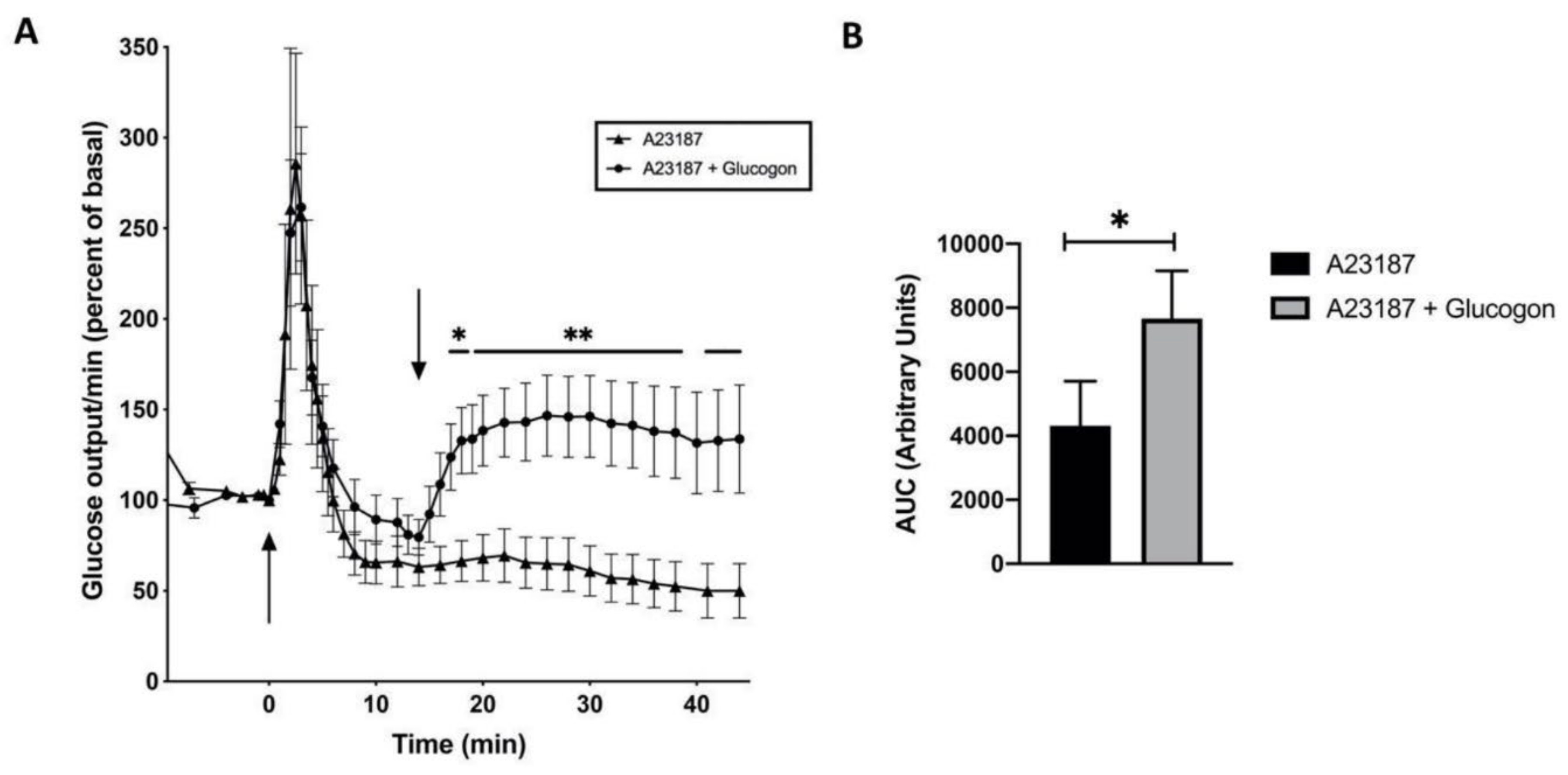

- Assimacopoulos-Jeannet, F.D.; Blackmore, P.F.; Exton, J.H. Studies of the interaction between glucagon and α-adrenergic agonists in the control of hepatic glucose output. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257, 3759–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biringer, R.G. A review of prostanoid receptors: expression, characterization, regulation and mechanism of actions. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2021, 15, 155–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Xu, Y.; He, Q.; Li, D.; Duan, J.; Li, C.; You, C.; Chen, H.; Fan, W.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Ligand-induced activation and G protein coupling of prostaglandin-F2α receptor. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, M.; Krett, A.-L.; Buenemann, M. Voltage dependence of prostanoid receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2020, 97, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, M.; Yang, T.; Sparks, M.A.; Manning, M.W.; Koller, B.H.; Coffman, T.M. Complex role for E-prostanoid 4 receptors in hypertension. J. Am. Heart Association 2019, 8, e010745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, E.A.; Takahashi, H.; Karakas, E. Structural basis for activation and gating of IP3 receptors. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebeau, P.F.; Platko, K.; Byun, J.H.; Austin, R.C. Calcium as a reliable marker for the quantitative assessment of endoplasmic reticulum stress in live cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woll, K.A.; Van Petegem, F. Calcium-release channels: structure and function of IP3 receptors and ryanodine receptors. Physiol. Rev. 2022, 102, 209–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhu, M.; Lu, X.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, J. Architecture and activation of human muscle phosphorylase kinase. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudet, S.; Zagar, Y.; Roche, F.; Gomez-Bravo, C.; Couvet, S.; Becret, J.; Belle, M.; Vougny, J.; Uthayasuthan, S.; Ros, O.; et al. Subcellular second messenger networks drive distinct repellent-induced axon behaviors. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, R.S. Store-operated calcium channels: From function to structure and back again. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2020, 12, a035055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catterall, W.A.; Lenaeus, M.J.; Jamal El-Din, T.M. Structure and pharmacology of voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2020, 60, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Lu, K.; Kamla, C.; Kameritsch, P.; Seidel, T.; Dendorfer, A. Synchronous force and Ca2+ measurements for repeated characterization of excitation-contraction coupling in human myocardium. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Simpson, P.C.; Jensen, B.C. Cardiac α1A-adrenergic receptors: emerging protective roles in cardiovascular diseases. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2021, 320, H725–H733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. The use of perfusion of liver and other organs for the study of microsomal electron transport and cytochrome P-450 systems. Meth. Enzymol. 1978, 52, 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, F.H. Die enzymatische Bestimmung von Glucose und Fructose nebeneinander. Klin. Wochenschr. 1961, 39, 1244–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passonneau, J.V.; Lauderdale, V.R. A comparison of three methods of glycogen measurement in tissue. Analyt. Biochem. 1974, 60, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, K. and Hull, W.F. 31P nuclear magnetic resonance studies of glycogen phosphorylase from rabbit skeletal muscle: Ionization status of pyridoxal 5‘-phosphate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 856–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soderling, T.R.; Park, C.R. Recent advances in glycogen metabolism. Adv. Cyclic Nucleotide Res. 1974, 4, 283–333. [Google Scholar]

- Kraft, G.; Coate, K.C.; Smith, M.; Farmer, B.; Scott, M.; Cherrington, A.D.; Edgerton, D.S. The importance of the mechanisms by which insulin regulates meal-associated liver glucose uptake in the dog. Diabetes 2021, 70, 1292–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).