1. Mutations in mtDNA

1.1. Characteristics of mtDNA

Eukaryotic cells contain two complete sets of genomes, namely the nuclear DNA and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA]. The mitochondria are postulated to have originated from the alpha-proteo-bacterium through the process of endosymbiosis [

1]. In humans, the mitochondrial genome is encoded in a 16,569 bp circular DNA. The coding region of the mtDNA includes 37 genes, these genes encode for 13 mitochondrial peptides which are important components of the oxidative phosphorylation system. These include the 13 peptides which form the subunits of complex I, III, IV and V, as well as 22 transfer-RNAs (tRNA] and 2 ribosomal-RNAs (rRNA] [

2]. The RNAs are key components for the process of mitochondrial protein synthesis.

Within the circular mtDNA, there is a segment of the noncoding region, commonly referred to as the displacement loop (D-loop]. D-loop has a length of 1,124 base pairs and covers two hypervariable regions with HV1 at 16,024 to 16,383 and HV2 at 57 to 372 [

3]. In the D-loop region, promoters for both H and L strands are found and act as a major component in initiating mtDNA transcription and replication. D-loop is also found to be a common location for mtDNA mutations.

The double-membrane mitochondrion is an important organelle which performs the function of regulating the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS] process, producing free radicals, regulating apoptotic activity and controlling the metabolic pathways [

4]. Arguably, the most important function of the mitochondria is the OXPHOS system, embedded in the lipid bilayer of the inner mitochondrial membrane. It results in the production of ATP to be used as energy for cellular activities. The OXPHOS system mainly consists of the protein enzyme complexes I to V, and coenzyme Q and cytochrome c both as electron carriers. It aims to maintain the movement of electrons and protons to result in ATP generation via a proton gradient across the mitochondrial inner membrane [

5]. Only a small portion of the mitochondrial-generated ATP is reserved for the use of the organelle itself, the majority of the ATP is distributed externally. This is achieved by the adenine nucleotide translocator and the ATP molecules are utilized for biological cellular functions [

6]. Additionally, it is also noted that the electrons found to depart the respiratory process in preliminary stages are responsible for the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS] [

2].

There are features of the human mtDNA that differ from nuclear DNA, such as high copy number, high mutation rate and heteroplasmy. Heteroplasmy is a condition in which both wild-type and mutated mitochondrial genomes coexist in the same cell. This can only happen with mtDNA, which can appear numerous times inside the same eukaryotic cell. When cells carrying heteroplasmic mtDNA undergo cell division, the mtDNA genomic content are randomly assorted and divided into the daughter cells. As a result, the proportions of mutant and wild type mtDNA may fluctuate over time, causing genetic drift. This results in genotypes with either entire mutant or wild type mtDNA, a phenomenon known as homoplasmy.

Secondly, another unique feature of the mtDNA is its high copy number. Since several copies of mtDNA exist in the same cell, it is believed that a threshold number of mutant genomes are necessary in the cell before the cellular activities would be disrupted. The threshold is not a set value because it is known to be heavily influenced by the tissue origin, disease pathophysiology and mutational phenotypic effects. It was demonstrated that the mutation type can also play a role in affecting the threshold value. A threshold value of 50-60% mutated mtDNA has been identified for deletions, whereas a significantly higher value is required for cellular dysregulation with point mutations [

7]. Therefore, to successfully apply mtDNA as a biomarker in disease progression, it is important to evaluate the genotypic-phenotypic impacts as well as the heteroplasmy compositions of the affected tissue [

8].

mtDNA is found in the mitochondrial organelle or eukaryotic cells and can be found at high copy numbers. The mtDNA copy number appears to be significantly dependent on the tissue or cellular origin [

9]. Since the rate of mtDNA replication in the mitochondria is independent of nuclear DNA, observing cell cycles cannot be used to estimate the copy number of mtDNA [

10]. It has been suggested that the copy number of mtDNA is carefully controlled by the cellular conditions both internal and external, including oxygen concentration and hormonal influences [

4]. Recent research have indicated that the mtDNA copy number can be utilized as an indication of disease prognosis in glioma patients [

11].

1.2. Types of Mutations in the mtDNA

High mutation rate is also a notable feature in the mitochondrial genome. The mutation rates in mtDNA have been demonstrated to be 10 to 200 times higher than those in nuclear DNA [

12]. This high mutation rate is presumed to be driven preliminarily by the lack of histone protection since mtDNA is bundled into nucleoids [

10]. Besides, the low efficiency of the mtDNA proofreading and repair mechanisms, the lack of intron and the high concentration of ROS located in the inner membrane of the mitochondria were postulated to contribute substantially to the high mutation rate.

Ju et al. conducted a study in the interest of uncovering possible effects of mtDNA mutations on oncogenesis and subsequent clonal selection advantages. Results from 1,675 matched cancer and healthy mtDNA samples across 31 cancer types show that there is no survival benefit for cancer cells carrying mtDNA mutations [

13]. Yet, it is crucial to note that this study was limited by sample size. Furthermore, only point mutation was reviewed, whereas structural variants and mtDNA copy number was omitted.

During replication, the mtDNA may acquire somatic mutations that were not inherited from the DNA templates and instead were spontaneously acquired. The cause of such spontaneous mutations is not known, but it is speculated to have occurred possibly due to external conditions such as high ROS cellular conditions, smoking habits and exposure to UV radiation. However, unlike malignancies known to be associated with exogenous mutagens, such as tobacco and lung cancer, no substantial link was found between carcinogens and mtDNA mutation [

13]. Furthermore, the association of BRCA1/2 gene mutation and breast cancer has been well established. Yet, no clear association to the mitochondrial genome in corresponding cells has been found [

14]. Thus, based on such understandings, it is proposed that the mechanisms of mtDNA differs significantly from those of the nuclear DNA. Moreover, the mtDNA mutations are indicated to occur endogenously in the mitochondria since external environmental factors are less prominently associated with mtDNA mutations [

13].

The first study to successfully identify physical mutations in the mtDNA was conducted in 1967, when mtDNA from leukaemia myeloid cells was shown to be in oligomer form using electron microscopes [

15]. Most studies in the early stages of mtDNA mutation focused on the identification of somatic point mutations specifically. For instance, a study performed by Abu-Amero et al. identified point mutations in the human thyroid carcinoma cells and concluded that mutations in the mitochondrial genome are critical to the early-stages of oncogenesis [

16]. In all, cancer research concentrating on the study of point mutations indicate that the mutations are frequently found in the D-loop area and are homoplasmic in nature. The D-loop region of the mitochondrial genome is a well-known hotspot for mutations. According to Yu et al., it was suggested that the homogeneous state of mtDNA mutation occurs throughout the neoplasticity transition stage in cancer cells [

4].

According to Krishnan et al., deletions in mtDNA have been found to cause sporadic mitochondrial-related diseases. Furthermore, the mitochondria in disease-ridden muscle tissue and the central nervous system were found to harbour mtDNA deletions. Moreover, deletion mutations are often detected in mtDNA from aged tissue and tissues affected by neurological disorders [

8]. Deletions in mtDNA can be further classified into small- or large-scale. Small-scale deletions are often defined as deletions that are less than 1kb in length. It is claimed that all mtDNA deletions share common features, such as its position and genomic structure. mtDNA deletions often occur in the primary arc that is surrounded by the O

H and O

L points of replication initiation, and approximately 85% of the deletions are bound by two short repeats [

17]. After comparing the mtDNA deletion profile of individuals affected by different diseases such as Parkinson’s against the healthy sample from an aged individual, the authors report similarities in the size, presence and length of the short repeats that flank the deleted genomic regions [

8]. This, in turn, suggests the possibility of a common mechanism operating behind all mtDNA deletion states under different pathological circumstances.

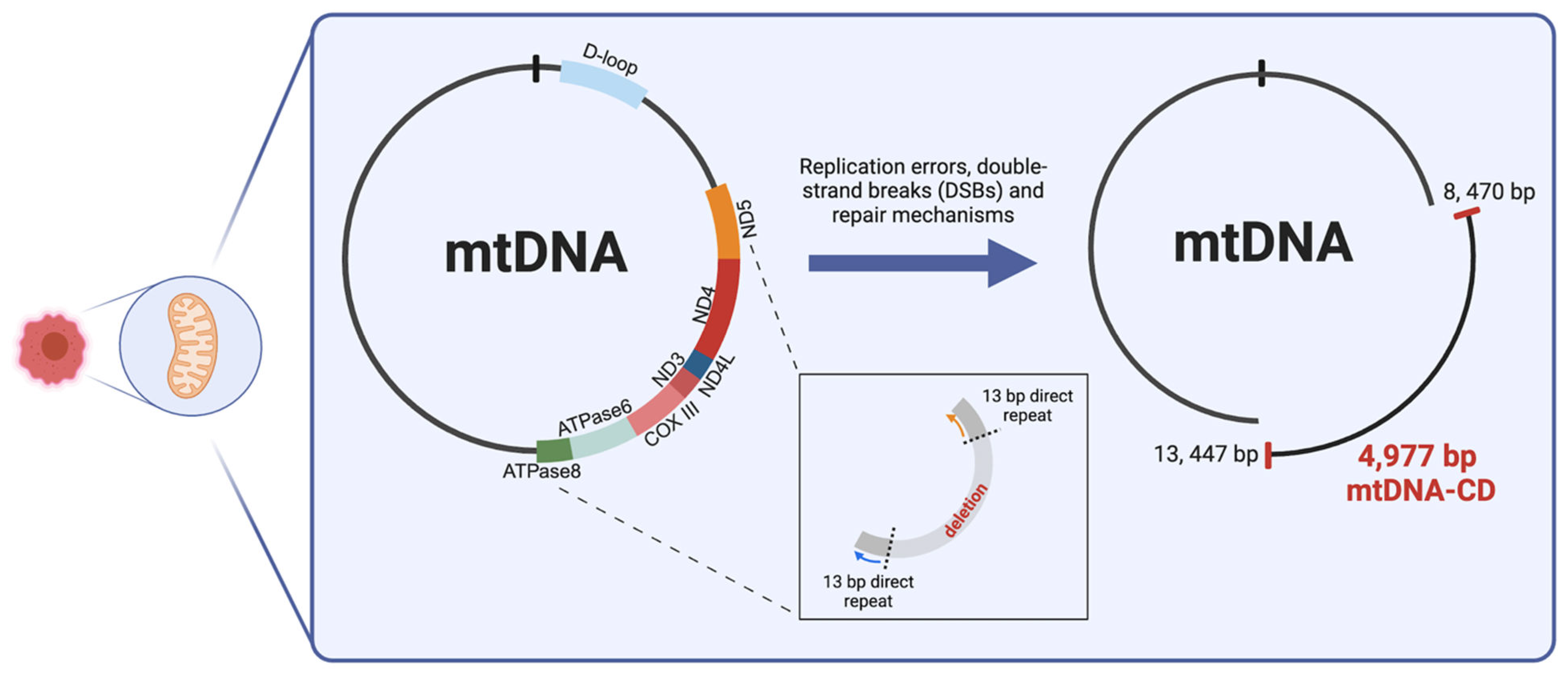

1.3. Common Deletion of the mtDNA

Among the noted mtDNA deletions found in various diseases and cancer types, a 4,977 bp deletion is commonly found between positions 8,470 and 13,447 (

Figure 1]. This deletion, which is flanked by two 13 bp direct repeats, is known as a "common deletion" (CD] because it affects a variety of sporadic disorders. The 4,977 bp long CD was shown to be the causative mutation for Pearson’s syndrome, chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO] and Kearns-Sayre syndrome. Additionally, several studies relate to the role of mtDNA deletion as a biomarker for mtDNA damage, as it is found in abundance in aged tissue [

2]. CD encompasses 12 essential genes encoding for seven complex subunits and five tRNA genes. The loss of the genomic region results in mitochondrial dysfunction because of the interruption in energy production and dysregulated ROS production. This is due to the complete loss of the ND3, ND4, ND4L, COX III, ATPase6 genes, and partial loss of the ND5 and ATPase8 genes. These genes encode for the Complex I subunits, one Complex IV subunit and 2 Complex V subunits [

18].

In contrast to mtDNA point mutations, Wallace et al. found that the CD is heteroplasmic and presents with clinical symptoms when the proportion of affected mtDNA exceeds the bioenergetic threshold in metabolic diseases such as mitochondrial encephalopathy (MELAS] [

19].

CD was first discovered in 1994 in skin squamous cell carcinoma and renal oncocytic tumours and was first linked to cancer pathology [

20,

21]. Recent investigations have also detected CD in breast and colorectal cancer samples, shedding light on the connection between mtDNA mutation and oncogenesis [

2]. In comparison to healthy samples, CD is found to be in higher abundance in tumour samples. Based on this finding, it is suggested that CD contributes to a selective survival advantage in the clonal expansion of cancer cells. Despite our current limited understanding of the molecular mechanism of CD in cancer progression, this discovery emphasizes the potential of mtDNA CD as a biomarker for cancer progression and pathogenesis [

4]. For example, through manipulation of the LNCaP cell line, it was proven that mtDNA deletion is a key component in the induction of the initial transition to the androgen-independent prostate cancer phenotype [

22]. This emphasizes the necessity of gaining a better understanding of the function of mtDNA CD in cancer development and pathogenesis.

To gain further understanding into the molecular mechanisms into the occurrence of deletion in the mitochondrial genome, Phillips et al. investigated the involvement of slipped-strand replication error and double-strand break (DSB] repair processes to better understand the mechanism behind CD formation. By simultaneously employing a DNA combining assay to unveil mtDNA replication mechanisms and creating DSB through adopting mito-TALENs (mitochondrially targeted transcription activator-like effector nucleases], the authors were able to distinguish a DSB repair mechanism that relies on the shared mechanisms of replication. Preliminary findings indicated that the mitochondrial replisome is responsible for the mtDNA break repair system, which is therefore linked to replication processes. The results of this study suggest that by inducing DSB using mito-TALENs, the frequently occurring replication fork stalling will encourage the mispairing of the 13bp repeats flanking the CD (

Figure 1]. This will inadvertently result in the extended exposure of the single-stranded genomic material on the heavy-strand mtDNA [

23]. To our understanding, this hypothesized replication-dependent repair mechanism best describes the potential pathway to CD formation in mtDNA [

18].

2. CD Is Cell-Type Specific in Different Cancer Types

The role of CD-mtDNA as a biomarker in disease diagnosis and prognosis tracking is well established. In a recent study of coronary artery diseases conducted on an Italian population, CD-mtDNA was found to be a viable biomarker for patients plagued by antagonistic cardiac episodes [

24]. CD-mtDNA was discovered to be more sensitive in predicting cardiovascular events than traditional biomarkers like troponin T and N-terminal pro-BNP. Furthermore, CD-mtDNA was identified as an independent predictor of cardiovascular events. Other than that, mtDNA mutation has been linked to illness severity, as reported by Zhang et al., who found a greater proportion of CD-mtDNA in blood samples from individuals with mitochondrial-associated disorders [

25]. It is thus thought that CD-mtDNA may serve as biomarkers in cancer progression. This proposal is supported by the notion of discovering mtDNA deletion signatures in most identified tumour and cancer samples [

26]. Functional effects on mitochondrial biogenesis have been found as a result of such mtDNA alterations; specifically, mutations in the cytochrome C gene may disrupt the normal progression of programmed cell death [

27]. Also, mtDNA in the ATP synthase subunit 6 gene (MTATP6] is associated with the inhibition of apoptosis, thus promoting oncogenesis [

27].

With the premise that mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to cancer formation, various research has endeavoured to discover the linked molecular pathways. An often-observed biochemical change occurring in cancer cells is the increase in glucose uptake and lactate secretion. Given the reported low respiratory rate in cancer cells, it is hypothesized that cancer cells rely significantly on the aerobic glycolysis pathway to create ATP molecules. However, healthy cells with a fully functional mitochondrial OXPHOS system would not require the employment of an alternate metabolic mechanism. Instead, it was postulated that when the mitochondrial respiratory and ATP generation functioning decreases due to accumulated mtDNA damage reaches a critical point. Hence, the healthy cell develops survival strategies by producing ATP through other routes. This phenomenon has since been named the Warburg effect [

4]. To present, investigations have shown that defective OXPHOS systems generate an excessive amount of ROS, facilitating the development of cancer cells [

28]. This circumstance has been perceived in a bladder cancer sample with Cytb deletion to intentionally induce high levels of ROS and lactate production [

29]. The increased cancer growth in the xenograft model demonstrates the relationship between mtDNA damage-induced ROS overproduction and the effective Warburg effect in oncogenesis.

First proposed in 1997, the use of synthesised peptide nucleic acids (PNAs] designed to be complementary to the human mtDNA containing the CD was employed to inhibit the replication process of CD-mtDNA [

30]. This established the notion of generating personalized treatment that targets cancer cells' energy metabolism, especially the mitochondrial OXPHOS pathway. Recent research has promoted the inclusion tumour bioenergetics in cancer cells as a hallmark feature of cancer [

31]. Most previous cancer treatments relied heavily on the development of drugs that are targeted therapies, such as imatinib (drug targeting kinase] and Herceptin [

31]. However, there are many undulated side effects from clinically prescribed targeted therapy drugs. Thus, research has shifted to the inhibition of components involved in energy generation pathways in cancer cells. Yet, due to the complexities and largely unknown mechanisms behind the dysregulation of the mtDNA OXPHOS system in cancer cellular functions, drug development cannot proceed with success. As a result, it is critical to understand the biological processes that control CD-mtDNA formation and its function in tumour growth.

Table 1.

Table summarising the findings of research in the identification of mtDNA-CD for each cancer type.

Table 1.

Table summarising the findings of research in the identification of mtDNA-CD for each cancer type.

| Breast cancer |

|

|

|

mtDNA-CD found in |

| |

Year |

Country |

Experimental method |

Cancer sample |

Adjacent non-cancerous sample |

Blood sample |

| Tan et al. |

2002 |

USA |

Conventional PCR |

0/19 (0%] |

0/19 (0%] |

|

| Dani et al. |

2004 |

Brazil |

Multiplex real-time PCR |

4/17 (23.5%] |

13/17 (76.5%] |

2/17 (11/8%] |

| Zhu et al. |

2004 |

USA |

Conventional PCR |

18/39 (46.2%] |

13/39 (33.3%] |

6/23 (26.1%] |

| Tseng et al. |

2006 |

Taiwan |

Conventional PR |

3/60 (5.0%] |

28/60 (47.0%] |

|

| Ye et al. |

2008 |

China |

Conventional PR |

76/76 (100%] |

76/76 (100%] |

|

| Pavicic & Richard |

2009 |

Argentina |

Conventional PR |

43/95 (45.3%] |

70/95 (73.7%] |

78/199 (39.2%] |

| Tseng et al. |

2009 |

Taiwan |

Conventional PR |

3/60 (5.0%] |

29/60 (48.3%] |

|

| Aral et al. |

2010 |

Turkey |

Nested-PCR |

0/25 (0%] |

0/25 (0%] |

|

| Tipirisetti et al. |

2013 |

India |

Conventional PR |

|

|

0/101 (0%] – BClqx0/90 (0%] – Normal |

| Dimberg et al. |

2015 |

Vietnam |

Nested-PCR |

73/106 (68.8%] |

89/106 (84%] |

|

| Nie et al. |

2016 |

China |

Conventional PCR |

50/107 (46.7%] |

44/107 (41.1%] |

10/113(8.9%] |

| Dhahi et al. |

2016 |

Iraq |

Conventional PCR |

0/26 (0%] |

0/26 (0%] |

|

| Gastric cancer |

|

|

|

mtDNA-CD found in |

| |

Year |

Country |

Experimental method |

Cancer sample |

Adjacent non-cancerous sample |

Blood sample |

| Máximo et al |

2001 |

Portugal |

Conventional PCR |

17/32 (53.1%] |

|

|

| Dani et al. |

2004 |

Brazil |

Multiplex real-time PCR |

11/14 (78.6%] |

14/14 (100%] |

2/17 (11.8%] |

| Wu et al. |

2005 |

Taiwan |

Conventional PCR |

3/31 (9.7%] |

17/31 (55%] |

|

| Kamalidehghan et al. |

2006 |

Iran |

Multiplex PCR |

6/107 (5.6%] |

18/107 (16.8%] |

|

| Kamalidehghan et al. |

2006 |

Iran |

Multiplex PCR |

9.71 (12.7%] |

1/71 (1.4%] |

|

| Wang & Lü |

2009 |

China |

Semi-quantitative PCR and real-time PCR |

86/108 (79.6%] |

73/108 (67.6%] |

29/56 (51.8%] |

| Colorectal cancer |

|

|

|

mtDNA-CD found in |

| |

Year |

Country |

Experimental method |

Cancer sample |

Adjacent non-cancerous sample |

Blood sample |

| Dani et al. |

2004 |

Brazil |

Conventional PCR |

24/46 (52.2%] |

38/46 (82.6%] |

2/17 (11.8%] |

| Aral et al. |

2010 |

Turkey |

Nested-PCR |

0/25 (0%] |

0/25 (0%] |

|

| Chen et al. |

2011 |

China |

Conventional PCR |

17/104 (16.3%] |

13/104 (12.5%] |

|

| Dimberg et al. |

2015 |

Vietnam |

Conventional PCR |

71/88 (80/7%] |

81/88 (92.0%] |

|

| Dimberg et al. |

2015 |

Sweden |

Conventional PCR |

71/105 (67.6%] |

97/105 (92.4%] |

|

| Li et al. |

2016 |

China |

Conventional PCR |

27/27 (100%] |

|

2/5 (40%] |

| Skonieczna et al. |

2018 |

Poland |

Conventional PCR |

2/100 (2%] |

0/100 (2%] |

|

| Oesophageal cancer |

|

|

|

mtDNA-CD found in |

| |

Year |

Country |

Experimental method |

Cancer sample |

Adjacent non-cancerous sample |

Blood sample |

| Abnet et al. |

2004 |

China |

Conventional PCR |

17/19 (89%] |

19/20 (95%] |

|

| Upadhyay et al. |

2009 |

India |

Duplex PCR |

2/39 (5.1%] |

1/39(2.6%] |

|

| Tan et al. |

2009 |

UK |

Conventional PCR |

2/12 (16.7%] |

9/10 (90%] |

1/12 (8.3%] |

| Kelas et al. |

2019 |

Turkey |

Conventional PCR |

0/76 (0%] |

|

|

| Ghadyani et al. |

2024 |

Iran |

Nested PCR |

33/41 (80.5%] |

|

0/50 (0%] |

| Oral cancer |

|

|

|

mtDNA-CD found in |

| |

Year |

Country |

Experimental method |

Cancer sample |

Adjacent non-cancerous sample |

Blood sample |

| Lee et al. |

2001 |

Taiwan |

Semi-quantitative PCR |

26/53 (49.1%] |

36/53 (67.9%] |

|

| Tan et al. |

2003 |

Taiwan |

Conventional PCR |

2/18 (11.1%] |

5/18 (27.8%] |

|

| Shieh et al. |

2004 |

Taiwan |

Real-time PCR |

12/12 (100%] |

12/12 (100%] |

|

| Pandey et al. |

2012 |

India |

Conventional PCR |

42/50 (84%] |

|

18/50 (36%] |

| Datta et al. |

2015 |

India |

Real-time PCR |

12/117 (10.2%] |

|

|

| Thyroid cancer |

|

|

|

mtDNA-CD found in |

| |

Year |

Country |

Experimental method |

Cancer sample |

Adjacent non-cancerous sample |

Blood sample |

| Máximo et al. |

2002 |

Portugal |

Semi-quantitative PCR |

0/5 (0%] |

0/5 (0%] |

|

| Aral et al. |

2010 |

Turkey |

Conventional PCR |

6/50 (12%] |

0/50 (0%] |

|

| Liver cancer |

|

|

|

mtDNA-CD found in |

| |

Year |

Country |

Experimental method |

Cancer sample |

Adjacent non-cancerous sample |

Blood sample |

| Fukushima et al. |

1995 |

Japan |

Conventional PCR |

7/28 (25%] |

|

23/35(65.7%] |

| Yin et al. |

2004 |

Taiwan |

Conventional PCR |

18/18 (100%] |

18/18 (100%] |

|

| Shao et al. |

2004 |

China |

Real-time PCR, quantitative TaqMan-PC |

19/27 (70.4%] |

12/27 (44.4%] |

|

| Wheelhouse et al. |

2005 |

China |

Conventional PCR |

17/62 (28%] |

59/62 (95%] |

6/6 (100%] |

| Gawk et al. |

2011 |

Korea |

Conventional PCR |

3/27 (11/1%] |

23/27 (88.9%] |

8/8 (100%] |

| Guo et al. |

2017 |

China |

Nested-PCR |

10/105 (9.52%] |

0/105 (0%] |

0/69 (0%] |

| Qiao et al. |

2017 |

China |

Conventional PCR |

0/86 (0%] |

|

|

| Nasopharyngeal carcinoma |

|

|

|

mtDNA-CD found in |

|

| |

Year |

Country |

Experimental method |

Cancer sample |

Adjacent non-cancerous sample |

Blood sample |

|

| Shao et al. |

2004 |

China |

Conventional PCR |

54/58 (93%] |

8/31 (26%] |

|

|

2.1. Breast Cancer

A study conducted at Georgetown University Medical Centre [

32] used the forward and reverse primer sets (mtF8295 and mtR13738], and no common deletion was found in the breast cancer samples. The sensitivity of the PCR method is thought to be as low as 0.01% of mtDNA-CD. Thus, according to the results found in this paper, the authors suggested that somatic mutations found in breast cancer may largely be composed of passenger mutations and play a minimal role in driving carcinogenesis. Furthermore, breast cancer samples taken from a Turkish patient cohort also showed negative results for CD identification [

33]. In this study, they used two separate techniques to ensure that low levels of CD would not be missed. Firstly, they employed two sets of primers for PCR. Secondly, they conducted a nested PCR procedure to ensure the lack of positive results was not caused by the low sensitivity of the methodology applied. The same findings were reported by Tipirisetti et al. in their 2013 case-control study and by Dhahi et al. in their 2016 screening of the Iraqi cohort [

34] [

35].

According to the study conducted by Zhu et al., they identified the 4,977 bp mtDNA-CD in both normal and breast cancer samples obtained from matched patient cohorts [

36]. Novel large-scale deletions in the mitochondrial genomes, such as 3,938 bp and 4,388 bp, were also studied but the results were unclear. However, the 4,576 bp deletion in the same D-loop area was found in 77% of breast cancer samples and only 13% of nearby normal tissue samples from the 39-patient repository. Additionally, the 4,576bp deletion was not present in breast tissue samples and blood samples taken from healthy individuals acting as controls. In a different study, the 4,977 bp mtDNA-CD was discovered in a comparison of breast cancer and benign breast disease (BBD] samples. Using the nested PCR method and the beta-globin gene as an internal positive control, the scientists found a significant incidence of mtDNA-CD in blood samples from breast cancer patients compared to BBD patients and healthy individuals [

37]. The reason for the identification in blood samples was postulated to be related to the high levels of oxidative stress in tumour microenvironments. Carcinogenesis is thought to be activated when internal cellular defences are overcome by oxidative stress levels, resulting in the buildup of oxidative damage in the mitochondrial genome, which manifests as CD. When the CD threshold is reached, apoptosis occurs and genetic content is released into the circulation, which the study suggests could be utilised as an effective diagnostic for breast cancer prognosis.

An early study conducted on tumour samples and the adjacent epithelial tissue samples reported less CD found in tumours than the adjacent tissue samples [

38]. The results of this study led the authors to propose that the CD correlates with a selective disadvantage towards proliferating cells in a highly selective tumour microenvironment. The significantly lower proliferative rate in non-tumoural tissue allows for cells with the mtDNA-CD mutation to survive without being selected against, which is subsequently identified in multiplex PCR results. Despite this, the author listed out the limitations that the difference in CD identification may be the effect of varying PCR sensitivity and possible cross-tissue contamination [

38]. In 2005, the use of transmitochondrial cybrid cells showed that even at low levels of heteroplasmy in cells harbouring the mtDNA-CD, there was increased sensitivity towards apoptosis cascade activation. This can possibly be linked to the low levels of CD found in tumour samples due to high selective pressure in proliferative tumour cells and the subsequent diluting effect. This proposal was supported by Tseng et al. since only 5% (3 out of 60 patients] of the breast cancer samples contained the CD mutation [

39]. Similar results were reported in the study conducted by the authors of Ye et al. [

40]. To further this, the authors proposed that the CD mutation is not a driver mutation in breast cancer carcinogenesis since the mutation threshold of 60% of required to present in cellular dysfunction. Therefore, it was suggested that the CD mutation does not play an important role in breast cancer carcinogenesis [

40].

mtDNA-CD was also studied in association with oxidative damage markers such as the NAD(P]H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1] enzyme [

41]. NQO1 C609T is a genetic polymorphism known to correlate with an increased risk of breast cancer. Reduction in the NQO1 enzyme function leads to lower capacity of antioxidant function and was suggested to be linked to the increased observed level of CD mutation. Although CD was identified in more non-tumoural samples, the association between CD identification and NQO1 enzyme deficiency remains substantial in the carcinogenesis of breast cancer. Besides the correlation of the NQO1 enzyme, oestrogen receptors were also found to be significantly associated with levels of CD mutation in a separate study conducted on a cohort of Vietnamese patients [

42]. The suggested molecular mechanism is the binding of oestrogen receptors to p53 on target genes, thus reducing the capacity of p53 to maintain mtDNA genome integrity and resulting in the repression of p53-transcriptional activation. This was suggested to be linked to the increased CD mutation observed in oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer patients.

2.2. Gastric Cancer

Maximo et al.'s research first indicated that CD was not present in gastric cancer samples [

43]. The presence of 4,977 bp mtDNA-CD was determined by analysing 32 tumours and adjacent tissue samples. It was found that the presence of CD was correlated with the presence of other mtDNA genomic mutations (5 out of 7 cases with two or more mutations]. Observing the variations in apoptotic tendencies in various tissue samples led the authors to propose that different mtDNA mutations have different functional effects on cellular function. Increased sensitivity to apoptosis is observed in cells harbouring mtDNA-CD alterations. The apoptotic rate of cancer cells remains unperturbed by the presence of point mutations in the mitochondrial genome. It was suggested that there is an inverse relationship between the presence of mtDNA-CD and the MSI status of samples from neoplastic gastric cancer. The proposed mechanism implies that the mtDNA-CD acts as the cell's apoptotic threshold, with the nMSI modification serving as a putative secondary consequence to cause cellular malfunction and consequent cell death [

43].

A study conducted in the Chinese cohort reported a high occurrence of mtDNA-CD mutation in gastric cancer samples (79.6%] when compared to adjacent healthy tissue (67.6%] [

44]. In the paper, the changes in manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD] expression level and reactive oxidative species (ROS] content were suggested to be correlated to gastric cancer carcinogenesis. Results obtained from cell lines with low levels of MnSOD expression were found to have high levels of CD and ROS, thus possibly suggesting the reduced anti-oxidative capacity of the cell leads to increased oxidative damage, resulting in the observed increase in CD mutation.

In contrast to the results reported by Maximo et al., the study reported by Wu et al. suggested a low incidence rate of mtDNA-CD (3 out of 31 gastric cancer samples, 10%] in gastric cancer samples [

45]. Adversely, 55% (17 out of 31 adjacent stomach epithelial tissue samples] of the non-tumoural tissue samples were found to contain the CD mutation. Furthermore, there was no observed association identified between the 4,977 bp mtDNA-CD mutation and point mutations in the D-loop region. The results were supported by the study conducted on an Iranian patient cohort [

46]. Only 5.6% (6 out of 107] of gastric cancer samples had CD but was identified in 16.8% (18 out of 107] adjacent healthy tissue samples. The authors suggested that this was related to the dilution effect of the high selection pressure in the tumour environment due to increased cellular proliferation. Additionally, the presence of CD was not correlated with patient physiological traits such as age, sex, tumour location and size.

On the other hand, a novel 8.9kb large-scale deletion was identified in a similar study reported by Kamalidehghan et al. After screening for several novel mtDNA deletions with varying lengths of 8.9kb, 8.6kb, 7.5kb and 7.4kb, the 8.9kb deletion was found in 12.7% of the gastric cancer samples available (9 out of 71] [

47]. A correlation was proposed between the patient’s age and the observed occurrence of the 8.9kb deletion in the gastric cancer sample. In addition to this, the 8.9kb deletion was found more commonly in intestinal-type gastric cancers when compared against diffuse-type gastric cancer. The specific correlation between cancer types towards the deletion signature leads to the possible hypothesis of different mechanisms behind the various genomic alterations affecting cellular dysfunctionality.

2.3. Colorectal Cancer

In the Turkish patient cohort, a study was conducted using matched primary colorectal tumour samples with adjacent non-neoplastic tissue samples [

33]. In this study, the mtDNA-CD was not found in the 25 colorectal cancer samples via the method of nested PCR. Thus, the CD mutation was proposed to be rare and not related to colorectal cancer by the authors of the paper.

However, an early study performed in a cohort of Brazilian patients produced the results of a higher frequency of mtDNA-CD found in the non-tumoural sample [

38]. The proposed mechanism was like other studies, conferring the selection pressure due to the metabolic disadvantage of proliferating tumour cells, leading to apoptosis. With the lower corresponding selection pressure in non-tumoural cells, the survival of cells under oxidative stress with differing levels of oxidative damage is identified by the accumulation of mtDNA-CD. The results of this study were supported by a subsequent study conducted using the nested PCR method in 104 colorectal cancer patients [

48]. Interestingly, in conflict with the previously postulated age-dependent accumulation of oxidative damage CD marker, the 4,977 bp mtDNA-CD was found to be more common in patients under the age of 65 (12 out of 48] at 25% occurrence. In contrast, the occurrence for patients over the age of 25 is around 8.9% (5 out of 56]. In addition to this, it was also observed that the mtDNA copy number has an inverse relationship with the CD mutation presence. To explain the observed results, the researchers suggested that the identification of CD alterations in the early stages of cancer may be caused by the retrograde pathways that result in carcinogenesis enhancement from the accumulation of CD mutation. However, as carcinogenesis progresses, the importance of a fully functional respiratory chain process becomes imminent and results in a selective advantage in the survival of cells without mtDNA-CD mutations in the tumour microenvironment. Therefore, the cells harbouring CD alterations are seen to reduce in number during the rapid growth phase.

Besides the age of the patients, the ethnic differences are also postulated to contribute to the differences in CD level. The study reported by Dimberg et al. on a mixed cohort of both Swedish and Vietnamese colorectal cancer patients suggested that there is a difference in the accumulation of the CD mutation in the colorectal tissue [

49]. In the colorectal cancer tissue samples from the Swedish cohort, 67.6% were found to contain the CD mutation (71 out of 105]. In contrast to the cancer samples from the Vietnamese cohort with a higher occurrence of 80.7% (71 out of 88]. However, it is noteworthy that despite the difference between the ethnic groups, the amount of CD found in non-tumoural samples remains higher in each ethnic group. The Swedish cohort non-tumoural sample with 92.4% (97 out of 105] and 92% for the Vietnamese cohort (81 out of 88] with CD in adjacent normal tissue samples. It is also noted that the occurrence of CD in Vietnamese patients is significantly higher than in Swedish patients.

Via a collection of the mesentery arteries from 27 patients with colorectal tumour resection surgery, a novel 4,408 bp mtDNA deletion was observed [

50]. By identifying the mtDNA genomic mutations in the mesenteric arteries, the authors have demonstrated that oxidative damages affect both cancer tissues and the neighbouring blood vessels. The 4,977 bp mtDNA-CD was found to significantly occur more in samples from healthy controls. On the other hand, the novel 4408 bp deletion was not found to significantly occur more in either tumour or adjacent tissue samples. Yet, due to the difference in the sequence structure of the 4,977 bp CD and 4,408 bp deletion, the authors hypothesised that the underlying molecular mechanisms for both deletions are different. The 4,977 bp CD has long been suspected to be caused by the mismatch of the 13 bp sequence in the ATP8 and ND5 genes. No similar repeat sequence was found at the 4,408 bp novel deletion junctions. Furthermore, two more large-scale deletions were reported by the authors of Skonieczna et al. in colorectal cancer tissue samples. The deletions were roughly positioned between the base pair positions of 3,418-3,432 and 10,941-10,951 [

51].

2.4. Oesophageal Cancer

Early studies reported by Abnet et al. identified a high occurrence of mtDNA-CD in both cancer and adjacent normal tissue. In the 21 patient sample of ESCC, CD mutation was found in 89% of the cancer samples (17 out of 19] and in 95% of the adjacent normal tissue samples (19 out of 20] [

52]. This high incidence of CD in the ESCC samples led the authors to propose the use of CD alteration as a biomarker. Moreover, the lack of CD in the corresponding peripheral blood from the tumour site led to the speculation that external factors are contributing to the increased mutation rate in the oesophageal tissue. In another study, the mtDNA-CD was found in both cancer and adjacent normal tissue samples, but in a significantly lower quantity. In the study reported by Upadhyay et al., they collected a total of 39 oesophageal cancer samples with corresponding adjacent normal tissue samples and intravenous blood samples [

53]. Among the samples, only 2 presented with the CD mutation in the cancer sample, and 1 was found to harbour the CD mutation in the adjacent normal tissue sample. This conflict with previous studies pointing towards the use of mtDNA-CD as a potential biomarker for cancer prognosis led the authors to hypothesise that the significant difference between CD mutations detected may be indicative of a population-specific mtDNA genomic alteration. This study was conducted in a Northern Indian population.

In contrast to the results published by Abnet et al., the results of the study performed by Keles et al. suggest that the mtDNA-CD is not found in ESCC and EA samples [

54]. For this study, they designed the experiment to identify the presence of the 4,977 bp CD and novel 7.4 kb deletion. However, due to the absence of both deletions, the authors further suggest that the large-scale deletions do not play pivotal roles in the prognosis of ESCC and EA.

Using two primer pairs and nested PCR methodology, 41 patient samples from the Indian population were used to identify mtDNA-CD [

55]. A significant 80% of ESCC samples were found to contain the CD mutation (33 out of 41]. Moreover, no CD alterations were identified in the corresponding healthy blood samples. In another study conducted, the authors suggested that the increase in CD mutations identified is correlated to the degree of dysplasia severity [

56]. However, according to the results from this study, it is recommended for the use of the mtDNA-CD as a biomarker to identify the severity of dysplasia but is not indicative of the presence of EA.

2.5. Oral Cancer

In a study to establish the association between oral cancer and the habit of chewing betel quid, it was found that 2 tumour samples out of 18 harboured the mtDNA-CD mutation, and 3 adjacent normal samples from 18 individuals contained the mtDNA-CD mutation [

57]. This corroborates with the literature on the lower amount of CD mutation in the cancer samples concerning the adjacent normal sample. To further explore the occurrence of CD in oral cancer, real-time PCR analysis was conducted on oral cancer samples obtained from 12 individuals [

58]. The difference between the presence of CD mutation in precancer and oral cancer samples was 0.367% and 0.137%, respectively. The authors of this paper conducted a baseline analysis of the level of CD mutation in every individual patient's peripheral lymphocyte to allow for the calculation of the relative fold change increase in ROS expression. This is especially helpful in the elimination of external possible contributing factors such as age and genetics. The results of this study propagated the authors to suggest the use of CD mutation as a biomarker for oral precancer identification.

In the Indian cohort, the mtDNA-CD was identified and reported in more cancer patients (42 out of 50] than healthy controls (18 out of 50] [

59]. The study suggests the association between CYP2E1 polymorphism and CD mutation to identify the increased risk of oral cancer development.

On the contrary to previous studies, the results published by an early study conducted by Lee et al. in a Taiwanese population point to a lower occurrence of CD mutation in cancer samples (26 out of 53] when compared against adjacent normal samples (36 out of 53]. The results of this study were collected using a novel semi-quantitative PCR method developed by the research group. In this procedure, each DNA sample undergoes serial dilution two-fold with distilled water before the PCR procedure. However, the conclusion supports that of Tan et al. in the role of betel quid chewing as an oral cancer risk factor [

57]. The results were also supported by a study in the Indian cohort, with significantly less CD mutation presence in the oral cancer sample compared to adjacent normal samples (9.8 and 10.5 folds, respectively] [

60].

2.6. Thyroid Cancer

An early study conducted by Maximo et al. focused on the various histologically different types of Hurthle cell carcinoma in thyroid cancer. Although mtDNA-CD was identified via semi-quantitative PCR in all thyroid cancer samples available (43 out of 43], they further analysed the presence of CD in each Hurthle cell histological type. Moreover, the presence of mtDNA-CD was shown to be significantly associated with Hurthle cell cancer (P value < 0.001] [

61]. The occurrence of CD mutation was significantly higher in Hürthle cell follicular carcinomas when compared to Hurthle cell adenomas and papillary carcinomas (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0012]. For adjacent normal tissue samples, mtDNA-CD was also found at low levels in several samples (12 out of 41]. Reviewing the results of the study, the authors note that the mtDNA changes observed in Hurthle cell cancer mimic the increase in mitochondrial number and structural abnormalities that are present in diseases such as mitochondrial encephalomyopathy (MELAS]. Their hypothesis that the presence of mtDNA-CD alteration suggests that the D-loop area in the mitochondrial genome is prone towards deletion events. This was supported by the observation that 81.5% of the observed point mutations in this study were found to be transitional mutations. Combining the findings from their study, it was proposed that due to CD mutation and reduced ATP production, the cell compensates with increased mitochondrial number. In a study conducted by Savagner et al., they proposed that the observed increase in uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2] expression is an adaptive response in recognition of the OXPHOS abnormalities in the affected cells [

62]. A further study conducted on a Turkish patient cohort supports the identification of mtDNA-CD in thyroid cancer samples [

33]. They identified 4 out of 50 thyroid cancer samples with CD present and 2 adjacent normal samples with CD too. It is noteworthy that the CD mutation was only identified when the nested PCR method was employed and not in the preliminary process of the PCR method used.

According to the results shown by Conti et al., the CD mutation was found in 25% of the thyroid cancer samples collected (2 out of 8] [

63]. However, in 70% of the paired adjacent normal parenchyma samples, the CD mutation was also observed in lower Ct values (30.41 and 28.7, p = 0.05]. Furthermore, the results also differed when the infarction status of tumours was compared, with the CD mutation found less in infarcted samples at 25% (2 out of 8] as compared to non-infarcted samples at 73% (8 out of 11]. This led the authors to speculate that the CD alteration might portray a protective effect on the conservation of the tumour cell viability by increasing tolerance towards oxidative stress [

63]. In agreement with prior studies, the authors suggested that the CD mutation results in a selective survival disadvantage in cancer cells undergoing rapid growth. Since CD was identified in both cancer and adjacent samples, the mutation can occur prior to thyroid carcinogenesis.

2.7. Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Employing an in-house designed real-time PCR protocol to confidently quantify the mtDNA of HCC and hepatocellular nodular hyperplasia (HNH] samples, Shao et al. first reported a novel large-scale deletion that was detected using both the conventional PCR and the quantitative TaqMan-PCR results [

64]. Proposed to be a subtype of the 4,977 bp common deletion, the deletion identified by Shao et al. has a length of 4,981 bp, and breakpoints are located at the 8,470 and 13,450 bp positions in the mtDNA. 70% of HCC samples (19 out of 27], 63% of HNH samples (17 out of 27] and 44% of HCC adjacent normal samples (12 out of 27] were found to harbour the 4981 bp novel mutation. In their conclusion, the deletion was stated to be significant in HCC samples but was insignificant in HNH and HCC-adjacent normal samples. Through this observation, they further suggested that the deletion alteration occurred during hepatocyte transformation and was accumulated in the mitochondrial genome. There was no correlation between external factors, including age, cancer stage, and HBV infection, with the occurrence of deletion in this study. Whereas, in a separate study that utilised the nested PCR method, the 4977bp mtDNA-CD deletion was identified in 9.52% of HCC samples (10 out of 105] [

65]. The CD alteration was completely absent in adjacent normal tissue samples, thus leading the authors of the paper to suggest the use of CD as an HCC cancer biomarker in clinical settings. The proposed mechanism for the presence of CD in the HCC sample is the occurrence of a higher percentage of oxidative damage.

An early study identified the presence of mtDNA-CD in 65.5% of HCC-adjacent normal samples (36 out of 55] [

66]. Yet only a small amount of HCC samples presented with CD (7 out of 28]. In a separate study, CD was also found more prominently in HCC-adjacent normal tissue samples, at the rates of 28% for HCC samples and 95% for HCC-adjacent normal samples [

67]. The observation of such occurrences led the authors to speculate that CD existence in HCC-adjacent tissue samples suggests a possible mechanism in the early stages of HCC carcinogenesis and a subsequent selection disadvantage towards cells harbouring the CD in HCC carcinogenesis. Thus, leading to the observation of more CD found in HCC-adjacent tissue samples and less in HCC samples. The results of these studies were also supported by the conclusion drawn by Gwak et al., where they reported a lower prevalence of CD in HCC when compared with non-neoplastic tissues [

68].

In a follow-up study, the mean proportion of mtDNA-CD found in HCC patients was proposed to be related to the sex of the patient [

69]. There is a slightly lower mean proportion of CD in cancer samples obtained from females when compared to males (0.0035 and 0.0104]. Additionally, alcohol consumption was also shown to be a significant risk factor in CD mutation occurrence. HCC patients reporting long-term alcohol consumption habits were found to have a significantly increased level of CD detected and a significantly reduced mtDNA copy number. This led the authors of the paper to propose that both acute and chronic ethanol consumption can lead to hepatic oxidative stress and subsequently result in cellular mitochondrial dysfunction.

2.8. Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

A novel CD-mtDNA that is 4,981 bp in length was initially identified in a study conducted in Guangzhou using paired healthy and cancer samples obtained from NPC patients [

70]. The increased frequency of CD-mtDNA identified in cancer samples when compared to matched nasopharyngitis samples and white blood cells suggests that cancer cells have a highly dynamic mtDNA genome. Furthermore, it supports the hypothesis that CD-mtDNA accumulates in cancer cells to perpetuate neoplastic transformation. This is further supported by the observation of CD-mtDNA found 3 times more in late-stage NPC samples (stages III and IV]. However, when stratified by age, the results indicate that age is also a contributing factor to the amount of accumulated CD-mtDNA in cancer cells from NPC patients. Furthermore, Pang et al. discovered that CD-mtDNA was abundant in samples from NPC patients who had received irradiation therapy [

71]. However, as no biopsy was conducted before the irradiation therapy, it is impossible to ascertain if CD-mtDNA was present before the irradiation treatment prescribed to the patient.

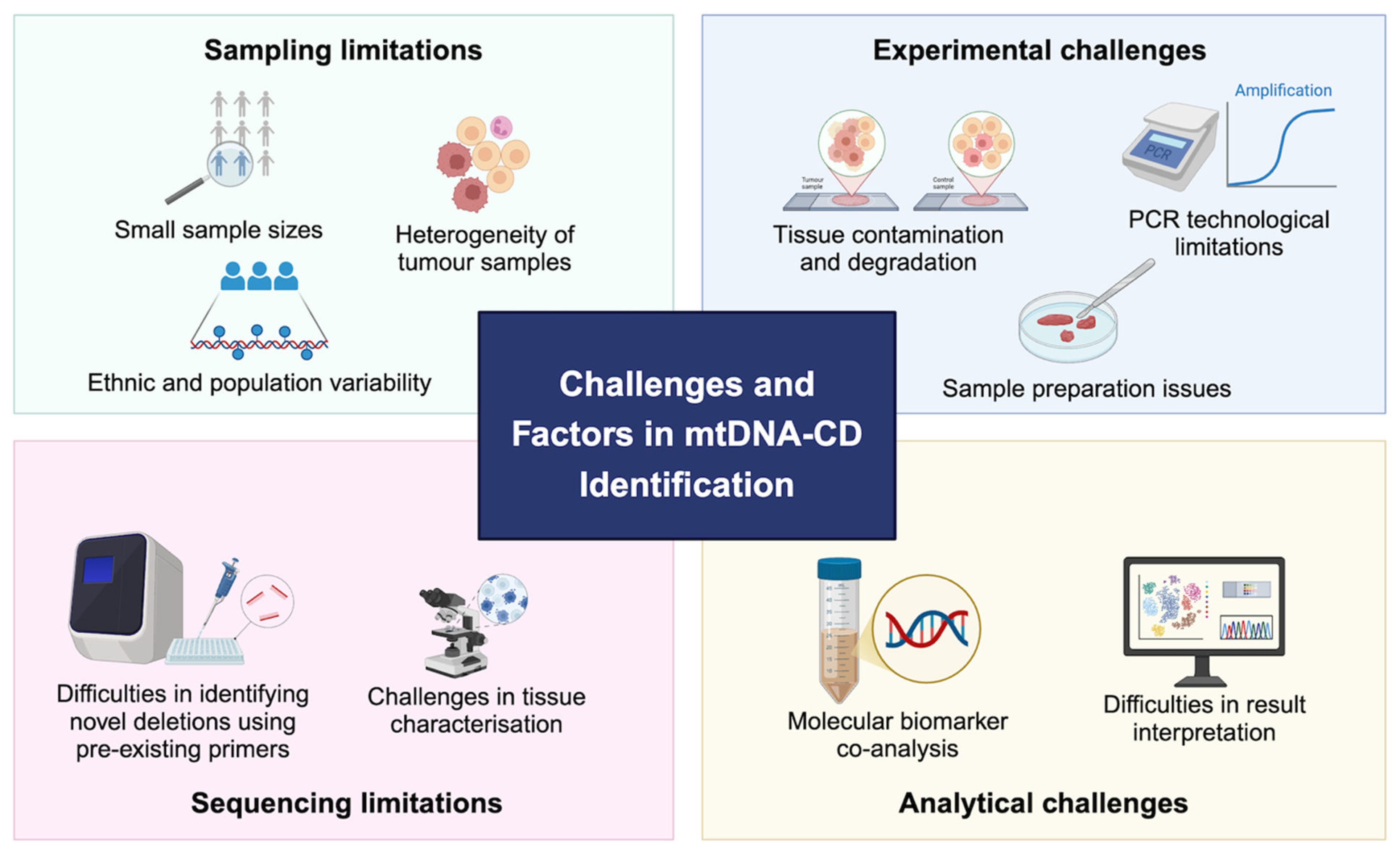

3. Methodological Challenges In Detection of CD

As discussed in previous section, the evidence for the presence of mtDNA-CD is quite heterogeneous. We identified and categories several challenges that limits the empirical detection and quantification of mtDNA-CD from human clinical samples. These challenges conclude: sampling limitation, experimental challenges, sequencing limitations, and analytical challenges (

Figure 2].

3.1. Sampling limitations

Small sample sizes. Small sample sizes are a common issue faced by multiple studies in the identification of CD in cancer patients (Dimberg et al., 2015; Upadhyay et al., 2009], this is partly due to the need for acquiring matching adjacent cancer samples for analysis comparison and acting as internalised control. Without matching cancer and normal samples, it is difficult to determine if the CD mutation signature is specific to either cell type cohort. A similar issue was reported by Nie et al. in their attempt to conduct a meta-analysis was faced with the issue of insufficient sample size, resulting in being unable to conduct an in-depth subgroup analysis [

72].

Ethnic diversity. In the study of breast cancer conducted by Tseng et al., the authors noted a difference in breast cancer diagnosis occurrences in the Taiwanese population compared to the Western population. They described the difference in the C609T polymorphism in the NQO1 enzyme reported in 68.3% of the Chinese cohort against the 26% of the Caucasian descent [

41]. This difference between the Caucasian population and the Asian population was also observed in the incidence of oral cancer [

59]. In their hypothesis of correlation of genetic polymorphism in the CYP2E1 gene, the authors noted that Caucasian populations have notably displayed low levels of CYP2E1 expression levels with the heterozygous c1c2 genotype. Thus, leading to a significant correlation to oral cancer.

For colorectal cancer, a significantly increase incidence of the mtDNA-CD was reported in the Vietnamese patient cohort than in the Swedish cohort [

49]. This is interesting because the authors note that the results identified in the Vietnamese patient population are like the findings previously identified in the Chinese population. However, in research conducted on oesophageal cancer, notable differences were identified when comparing different Asian populations. Upadhyay et al. Reported a significant difference in the number of CD incidences in the Chinese population when compared to a Northern Indian population using oesophageal cancer samples [

53]. A similar difference was seen in a subsequent study conducted by Keles et al in oesophageal carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma [

54].

Within-sample heterogeneity. Cancer stages play a vital role in determining mutational signatures. This was proven in a study conducted by Ju et al., in which mutations specific to metastatic tumour clonal samples were identified. Thus, leading to the suggestion that the mtDNA changes are dynamic and will continue to evolve throughout the tumour progression.

Van Trappen et al. reported a similar result in their samples acquired from ovarian cancer patients. The authors reported that taking multiple biopsy samples of the same tumour site from the same patient would result in the identification of various mtDNA mutations. A possible mechanism causing this difference is that two primary tumours arose from the same population of primary cells, or there was an incidence of clonal expansion in the tumour cell population [

27]. This study highlights the importance of longitudinal studies in cancer profiling to be able to differentiate between driver and passenger mutation in drug target identification.

Understanding that many types of mutations occur within the mitochondrial genome, is thus important in the step of selecting mutations for analysis. It is observed that the aggressive filtering of different mutations can result in a high number of false positive result identifications thus leading to misinterpretation of the biological significance [

73]. Furthermore, this argument is supported by biological factors affecting the presence of large-scale deletions. For example, it has been pointed out that smaller genomes have a selectively higher replication advantage. Therefore small-scale deletions will not appear to accumulate, thus leading to the development of a false sense of mutational selection in the tumour microenvironment [

36].

The difficulties in the analysis are further complicated by the observation of a lack of association between point mutations, mtDNA copy number changes and large-scale deletions. This leads to the hypothesis that different mechanisms are driving the occurrences and physiological effects of such mutations on cellular functionality [

45].

Furthermore, the decision of selecting different sites for biopsy collection can also impact the observed results. In different studies, various samples have been used as a positive internal control for the discovery of mutations in the cancer sample. This includes obtaining tumour-adjacent normal tissues and matched healthy patient samples. However, in several studies, blood samples were taken and used as healthy controls [

38]. Moreover, in a colorectal cancer study conducted by Li et al., samples obtained from mesenteric arteries were taken and used as an internal control for mutation profiling. The authors hypothesised that the blood vessels surrounding the cancer site might play a role in supporting cancer proliferation and growth [

74].

Moreover, the cellular integrity of the biopsy samples is also an important factor. Fine needle aspiration is a common procedure used to diagnose thyroid nodules, however, it is also found to cause histopathological changes in thyroid cancer cells [

63]. The expected histological differences after the FNA procedure may result in difficulties in diagnosis subsequently. It is suggested that this will lead to complications in the identification of tumour type due to infarction situations. Thus, leading to results that cannot be interpreted in the study of mutation profiling. The accurate identification of biopsy samples histologically is important as the subsequent samples will be used in the identification of CD mutations.

3.2. Experimental Challenges

Limitations of traditional methods. Maximo et al. first suggested it in their discovery of CD in gastric cancer samples which were previously not found. The authors of the paper suggested the difference in the technical method employed in the identification of CD in their protocol yielded higher sensitivity and specificity, thus contributing to the positive results acquired in their study [

43]. This is supported by the results reported by Areal et al., in the study of thyroid cancer in a Turkish cohort where the results of six samples were found to be associated with CD when the nested PCR method was used. In their early result, conventional PCR was employed and no CD was discovered within the same samples [

33].

Adding on to this argument, it was further proposed that quantitative real-time PCR procedure has a significantly higher sensitivity than Southern blot analysis in the identification of CD in mtDNA [

38]. The dire need for quantifiable identification of CD was also supported by Ye et al. in their suggestion for consolidating the conflicting results reported by distinct groups on the presence of CD in the same cancer type. They suggested that the limitations and inconsistencies of non-quantitative methodologies will hinder the analysis of the cancer samples and thus lead to inconclusive results.

Sample preparation limitations. Aral et al. also further suggested that the results that are seen as inconsistent in similar cancer types can be attributed to the laboratory techniques chosen for sample preparation [

33]. For example, the samples might be fresh frozen tissue or formalin-fixed.

In the study conducted by Shieh et al., they proposed the use of both laser micro-dissection technique and real-time quantitative PCR methodology would most appropriately result in the identification of CD. According to the results released in their paper, this method allows for reproducible and precise quantitative measurement of the occurrence of CD in formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue samples [

58]. By identifying pure cell populations from the patient tissue sample through molecular, there is significantly less undesired cell type population in the sample analysed. This is important as a homogenised tissue sample containing multiple cell types or undesired cell types can result in confusing outcomes for downstream analysis. Furthermore, they suggested applying a longitudinal study in CD genotyping to allow for the quantification of the CD occurrences into relative fold change values for better comparison and analysis.

Tissue degradation and contamination. In a study comparing tumour samples against adjacent normal tissue samples, the difference in mtDNA-CD concentrations identified raised the possibility of tissue contamination when obtaining the biopsy [

38]. This question was raised because, in subsequent repeated findings, the authors identified less CD concentration in adjacent normal tissue samples prepared using micro-dissection methods. Similar concerns were raised by several other independent studies [

39,

45], a consensus is observed that micro-dissection of the tumour sample is the current most effective method in reducing tissue contamination. However, further research is needed to establish this.

In addition to this, tissue degradation was suggested as a plausible reason for the identification of CD in tumour samples. A possible strategy in mitigating the effects of tissue degradation is to employ a preliminary check by using PCR to amplify a region not associated with the deletion in the mtDNA genome to ensure no tissue degradation has occurred [

36].

3.3. Sequencing Challenges

Using pre-existing primers on novel deletions. In most research conducted to identify CD in the mitochondrial genome of various cancers, the authors elected to use primers already present and available. This is reasonable within the criteria that the common deletion is expected to be found within the cancer sample or the adjacent normal sample. However, in several studies, novel deletions have been identified, thus making it unreasonable to use already present primers targeted to only specific breakpoints in the known 4,977 bp common deletion.

Two novel large-scale deletions were first reported by Zhu et al. in breast cancer samples. The identified 3,938 and 4,388 bp deletions were found to be of higher prevalence in cancer samples than their matched adjacent normal samples [

36]. Following this, another novel deletion was also discovered in colorectal cancer tissue, located around the 3,418 - 3,432 and the 10,941 - 10,951 base positions in the mitochondrial genome [

51]. Interestingly, there are also subtypes to the 4,977 bp CD identified in HCC samples [

64]. This novel 4,981 bp deletion fragment was identified in the gel electrophoresis result and is located from the 84,710 bp to the 13,450 bp.

In lieu of the known limitations of the current conventional PCR in the identification of large-scale deletions, a novel real-time PCR assay was introduced by Ye et al. in hopes of creating a new protocol with higher sensitivity and increased convenience. Targeting the current issues with the time-consuming semi-quantitative PCR and plateau effects which affect the quantitative endpoint determination in conventional PCR, this new method was reported to have less possible contamination [

40]. Besides that, another possible PCR method for increased identification of CD is the digital PCR [dPCR] method [

75]. To overcome the limitations of conventional PCR in quantifying mtDNA deletions of low abundances, dPCR has increased precision to mitigate error and increase sensitivity. However, the efficacy of the dPCR method in CD identification still requires further study.

3.4. Analytical Challenges

Despite the unknown mechanisms driving the presence of large-scale deletions in the mitochondrial genome, it is undeniable that current studies all agree that mutations in the mtDNA are seen to be cancer-type specific [

48]. With increasingly available amounts of publicly available results and data on different cancer types and the mutations found in the mitochondrial DNA, there is a clear need for further analysis into the identification of cancer-specific mutation profiling [

2].

Challenges in result interpretation. The mitochondrial genome is prone to mutation occurrences due to its poor repair mechanisms and has a high tolerance towards mutations due to the high copy number compensation. However, it was suggested that the effect of a structural variant is greater than that of a single nucleotide change [

43]. Yet, it is the observed protein truncation effect of the mutation that is postulated to case phenotypic changes in the cell. Therefore, it is important to identify the phenotypic effects that arise from the mutations to identify its deleterious effects in the individual.

Despite this, it is notable that the interpretation of results may remain challenging. One of the main reasons is due to the metabolic effects of CD in the tissue to cause cellular dysfunction. The effect of such mutation is highly dependent on the tolerance of the cell towards oxidative stress and threshold [

38]. This leads to the suggestion made by Kim et al., that the interpretation of the mtDNA mutation should be tailored towards its specific effects towards the disease of interest. Subsequently, the importance of the mtDNA mutation should be evaluated based on the physiological effects and functional consequences resulting from the mutated mitochondrial genome [

31].

The understanding of the physiological effects of mutations in the mitochondrial genome has been limited due to several factors such as structural differences in the mtDNA. The D-loop in the mitochondrial genome is a known genomic section prone to mutation. Many studies have identified both structural variation and point mutations occurring commonly in this region, yet the direct functional effects of such mutations have yet to be discovered [

31].

Molecular biomarker co-analysis. As not much is understood from the current understanding of the physiological and functional effects of CD in carcinogenesis, it is therefore detrimental to employ different analytical strategies to better quantify and identify the presence and effects of CD in biological processes. This was first performed by Tseng et al., in the use of the NQO1 enzyme as a co-biomarker in the identification of deletion in the mtDNA genome of breast cancer samples. The results showed that there is a significant increase in the presence of the CD mutation in breast cancer samples harbouring the 609 C/T and T/T genotypes when compared against the patient samples with the C/C genotype. By using co-bio markers, the authors were able to come to a conclusion which connects the speculation of increased oxidative stress with the reduction of anti-oxidative functions of the NQO1 enzyme to support the carcinogenesis of breast cancer in the affected patients [

41].

Other antioxidant biomarkers were also used in the co-analysis of CD mutation, such as the manganese superoxide dismutase [MnSOD]expression levels. It was reported in gastric cancer that the co-analysis using MnSOD pathways was able to support the findings that mtDNA-CD is a marker of gastric carcinogenesis. This is purported due to the reduction of anti-oxidative functions of MnSOD, leading to increased oxidative stress and higher reactive oxidative species [ROS] levels and thus resulting in the observed CD levels [

44].

Another study in breast cancer also utilised MnSOD as a co-analysis biomarker, the authors reported similar results of oxidative stress and reduced onto-oxidative functions, leading to increased oxidative damage in the cancer cells [

37]. By using the MnSOD as a common biomarker for oxidative damage in cancer samples, they were able to conclude that breast carcinogenesis can be detected using CD as an oxidative damage marker.

Other external factors. Common risk factors are often well-established for distinct types of cancers, risk factors such as environmental, physiological and comorbidities can affect the results obtained from mutational profiling. For example, in oral cancer, habits such as cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption are well-known risk factors contributing to mtDNA damage [

53]. This is also reported in oesophageal cancer, where the severity of dysplasia can be used to determine the quantity of CD found in the mtDNA genome [

56]. Furthermore, it was also shown that long-term heavy alcohol usage in HCC patients will result in an expected increase in mtDNA-CD identified due to the extensive damage [

69].

Consolidating the findings from these studies, it is imminent that there is a need to collect epidemiological information from patients and further subtypes during CD analysis, as these risk factors are found to directly correlate with the identification of CD. By ignoring the effects of these risk factors and analysing the results from the cohort, we risk missing essential information which might be lost in the homogenised data. This also highlights the importance of increased sample size to allow researchers to confidently conclude population-specific and cancer type-specific inferences about CD occurrence.

It is further notable that the current studies on the identification of mtDNA-CD are conducted primarily on solid tumour cancer types, limited research has been reported on sarcomas. However, it is currently unclear whether this stems from the lack of detection of mtDNA-CD in sarcomas or due to the uncertainty in results resulting from small sample sizes.

4. Future Perspectives

In this review, we discussed the current studies conducted in the field of the identification of the large-scale deletion in the mitochondrial genome. The mtDNA-CD is a 4,977 bp deletion located in the mitochondrial genome and results in the removal of 7 essential genes. Despite the large number of research reported on the identification of the mtDNA-CD, the role of the deletion as a biomarker in cancer prognosis remains unclear. We note that there are several potential limitations in the experimental design, sampling method and analytical techniques that possibly contribute to the resulting ambiguous data.

Emerging technologies, such as single-cell RNA-sequencing or long-read sequencing may be useful in further research into large-scale deletions in the mitochondrial genome. This will potentially reduce the artefacts caused by inaccurate histological annotation of cell type and increase the sequencing coverage to better capture the occurrence of large-scale deletions. Furthermore, it is suggested that multiple biopsy samples should be taken from individual patients to allow for internalised control during data analysis. Additionally, the heterogeneity of the patient sample can be by conducting single-cell RNA-sequencing for cell-type annotation to better analyse the effects of deletion mutation in each cell type within the tumour microenvironment.

In addition, with the vast number of publicly available scRNA-seq data in databases, it is possible to conduct a data mining and re-analysis of known published data. This might revel previously missed key insight into the mechanisms of mutations in the mitochondrial genome. Moreover, spatial transcriptomics methods may also be employed for better understanding of the cell-cell interaction to better depict the mechanisms and occurrence of mtDNA-CD in tumour and adjacent normal cells. In conclusion, further studies are required to clarify the association of CD-mtDNA with cancer diagnosis and prognosis.

Funding

This work was supported in part by AIR@InnoHK administered by Innovation and Technology Commission of Hong Kong, Shenzhen-Hong Kong–Macau Technology Research Programme Type C, Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Fund [Guangdong Natural Science Fund] General Programme [2023A1515011265], and General Research Fund of the Research Grant Council of Hong Kong [17123223].

Acknowledgement

We thank members of Ho Laboratory for their support and insightful feedback throughout this study.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

- Gray MW, Burger G, Lang BF. Mitochondrial Evolution. Science. 1999 Mar 5;283[5407]:1476–81.

- Shen L, Fang H, Chen T, He J, Zhang M, Wei X, et al. Evaluating mitochondrial DNA in cancer occurrence and development. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010 Jul;1201:26–33. [CrossRef]

- Sharma H, Singh A, Sharma C, Jain SK, Singh N. Mutations in the mitochondrial DNA D-loop region are frequent in cervical cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2005 Dec 16;5:34. [CrossRef]

- Yu M. Somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations in human cancers. Adv Clin Chem. 2012;57:99–138.

- Smeitink J, van den Heuvel L, DiMauro S. The genetics and pathology of oxidative phosphorylation. Nat Rev Genet. 2001 May;2[5]:342–52.

- Saraste M. Oxidative Phosphorylation at the fin de siècle. Science. 1999 Mar 5;283[5407]:1488–93. [CrossRef]

- Taylor RW, Turnbull DM. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2005 May;6[5]:389–402. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan KJ, Reeve AK, Samuels DC, Chinnery PF, Blackwood JK, Taylor RW, et al. What causes mitochondrial DNA deletions in human cells? Nat Genet. 2008 Mar;40[3]:275–9.

- Clay Montier LL, Deng JJ, Bai Y. Number matters: control of mammalian mitochondrial DNA copy number. Journal of Genetics and Genomics. 2009 Mar;36[3]:125–31.

- Chen XJ, Butow RA. The organization and inheritance of the mitochondrial genome. Nat Rev Genet. 2005 Nov;6[11]:815–25.

- Zhang Y, Qu Y, Gao K, Yang Q, Shi B, Hou P, et al. High copy number of mitochondrial DNA [mtDNA] predicts good prognosis in glioma patients. Am J Cancer Res. 2015 Feb 15;5[3]:1207–16.

- Larsen NB, Rasmussen M, Rasmussen LJ. Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA repair: similar pathways? Mitochondrion. 2005 Apr;5[2]:89–108.

- Ju YS, Alexandrov LB, Gerstung M, Martincorena I, Nik-Zainal S, Ramakrishna M, et al. Origins and functional consequences of somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations in human cancer. eLife. 2014 Oct 1;3:e02935. [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Aparicio SAJR, Behjati S, Biankin AV, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013 Aug;500[7463]:415–21.

- Clayton DA, Vinograd J. Circular Dimer and Catenate Forms of Mitochondrial DNA in Human Leukaemic Leucocytes. Nature. 1967 Nov;216[5116]:652–7.

- Abu-Amero KK, Alzahrani AS, Zou M, Shi Y. High frequency of somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations in human thyroid carcinomas and complex I respiratory defect in thyroid cancer cell lines. Oncogene. 2005 Feb 17;24[8]:1455–60. [CrossRef]

- Samuels DC, Schon EA, Chinnery PF. Two direct repeats cause most human mtDNA deletions. Trends in Genetics. 2004 Sep 1;20[9]:393–8. [CrossRef]

- Yusoff AAM, Abdullah WSW, Khair SZNM, Radzak SMA. A comprehensive overview of mitochondrial DNA 4977-bp deletion in cancer studies. Oncol Rev. 2019 Apr 16;13[1]:409. [CrossRef]

- Wallace DC, Chalkia D. Mitochondrial DNA Genetics and the Heteroplasmy Conundrum in Evolution and Disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013 Nov;5[11]:a021220. [CrossRef]

- Pang CY, Lee HC, Yang JH, Wei YH. Human skin mitochondrial DNA deletions associated with light exposure. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994 Aug 1;312[2]:534–8. [CrossRef]

- Tallini G, Ladanyi M, Rosai J, Jhanwar SC. Analysis of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA alterations in thyroid and renal oncocytic tumors. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1994;66[4]:253–9. [CrossRef]

- Higuchi M, Kudo T, Suzuki S, Evans T, Sasaki R, Wada Y, et al. Mitochondrial DNA determines androgen dependence in prostate cancer cell lines. Oncogene. 2006 Mar 9;25[10]:1437–45. [CrossRef]

- Phillips AF, Millet AR, Tigano M, Dubois SM, Crimmins H, Babin L, et al. Single-Molecule Analysis of mtDNA Replication Uncovers the Basis of the Common Deletion. Mol Cell. 2017 Feb 2;65[3]:527-538.e6. [CrossRef]

- Vecoli C, Borghini A, Pulignani S, Mercuri A, Turchi S, Carpeggiani C, et al. Prognostic value of mitochondrial DNA4977 deletion and mitochondrial DNA copy number in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2018 Sep;276:91–7. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Ma Y, Bu D, Liu H, Xia C, Zhang Y, et al. Deletion of a 4977-bp Fragment in the Mitochondrial Genome Is Associated with Mitochondrial Disease Severity. PLOS ONE. 2015 May 29;10[5]:e0128624. [CrossRef]

- Penta JS, Johnson FM, Wachsman JT, Copeland WC. Mitochondrial DNA in human malignancy. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research. 2001 May 1;488[2]:119–33.

- Van Trappen PO, Cullup T, Troke R, Swann D, Shepherd JH, Jacobs IJ, et al. Somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations in primary and metastatic ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2007 Jan;104[1]:129–33. [CrossRef]

- Lee HC, Wei YH. Mitochondrial DNA Instability and Metabolic Shift in Human Cancers. Int J Mol Sci. 2009 Feb 23;10[2]:674–701. [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta S, Hoque MO, Upadhyay S, Sidransky D. Mitochondrial cytochrome B gene mutation promotes tumor growth in bladder cancer. Cancer Res. 2008 Feb 1;68[3]:700–6.

- Taylor RW, Chinnery PF, Turnbull DM, Lightowlers RN. Selective inhibition of mutant human mitochondrial DNA replication in vitro by peptide nucleic acids. Nat Genet. 1997 Feb;15[2]:212–5. [CrossRef]

- Kim A. Mitochondrial DNA Somatic Mutation in Cancer. Toxicol Res. 2014 Dec;30[4]:235–42.

- Tan DJ, Bai RK, Wong LJC. Comprehensive scanning of somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2002 Feb 15;62[4]:972–6.

- Aral C, Akkiprik M, Kaya H, Ataizi-Çelikel Ç, Çaglayan S, Özisik G, et al. Mitochondrial DNA common deletion is not associated with thyroid, breast and colorectal tumors in Turkish patients. Genet Mol Biol. 2010;33[1]:1–4. [CrossRef]

- Tipirisetti NR, Lakshmi RK, Govatati S, Govatati S, Vuree S, Singh L, et al. Mitochondrial genome variations in advanced stage breast cancer: A case–control study. Mitochondrion. 2013 Jul 1;13[4]:372–8. [CrossRef]

- Dhahi MAR, Jaleel YA, Mahdi QA. Screening for Mitochondrial DNA A4977 Common Deletion Mutation as Predisposing Marker in Breast Tumors in Iraqi Patients. Current Research Journal of Biological Sciences. 2016;8[1]:6–9. [CrossRef]

- Zhu W, Qin W, Sauter ER. Large-scale mitochondrial DNA deletion mutations and nuclear genome instability in human breast cancer. Cancer Detect Prev. 2004;28[2]:119–26. [CrossRef]

- Nie H, Chen G, He J, Zhang F, Li M, Wang Q, et al. Mitochondrial common deletion is elevated in blood of breast cancer patients mediated by oxidative stress. Mitochondrion. 2016 Jan;26:104–12. [CrossRef]

- Dani MAC, Dani SU, Lima SPG, Martinez A, Rossi BM, Soares F, et al. Less DeltamtDNA4977 than normal in various types of tumors suggests that cancer cells are essentially free of this mutation. Genet Mol Res. 2004 Sep 30;3[3]:395–409.

- Tseng LM, Yin PH, Chi CW, Hsu CY, Wu CW, Lee LM, et al. Mitochondrial DNA mutations and mitochondrial DNA depletion in breast cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006 Jul;45[7]:629–38. [CrossRef]

- Ye C, Shu XO, Wen W, Pierce L, Courtney R, Gao YT, et al. Quantitative analysis of mitochondrial DNA 4977-bp deletion in sporadic breast cancer and benign breast diseases. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008 Apr;108[3]:427–34. [CrossRef]

- Tseng LM, Yin PH, Tsai YF, Chi CW, Wu CW, Lee LM, et al. Association between mitochondrial DNA 4,977 bp deletion and NAD[P]H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 C609T polymorphism in human breast tissues. Oncol Rep. 2009 May;21[5]:1169–74.