Introduction

Throughout this paper, we consider all rings R as commutative rings with unity . The radical of an ideal I in R is traditionally denoted by , in particular, the set of nilpotent elements of R is represented by . The set of all zero divisors of the ring R is denoted by .

The concepts of prime and primary ideals have been well-established in ring theory, serving as fundamental tools for understanding the structure and properties of commutative rings. These ideals have been extended to more complex concepts such as 2-absorbing and 2-absorbing primary ideals. The concept of a 2-absorbing and 2-absorbing primary ideals, introduced by [

4,

5], defines a proper ideal

I such that for any elements

,

Similarly, a 2-absorbing primary ideal is defined by the condition

These generalizations have paved the way for further exploration into more nuanced types of ideals. In the continuation of extending these concepts, the notion of

n-ideals was introduced in [

24]. For a proper ideal

I and elements

,

In [

23],this concept has been further expanded to

-ideals, where a proper ideal

I is considered a

-ideal if for any

,

Recently, in [

6], a new class of ideals which is called 2-nil ideal have been introduced. A proper ideal

I of a ring

R is said to be 2-nil ideal if whenever

then

Despite these advancements, there remains a need to explore other potential classes of ideals that can offer deeper insights into the structure of commutative rings. In this paper, we introduce a new class of ideals known as 2-nil primary ideals. This new class seeks to bridge the gap between existing concepts and provide a broader framework for understanding ideal theory in commutative rings. In this study, a proper ideal

I is defined as a 2-nil primary ideal if for any elements

,

This definition presents a distinct viewpoint by including the collection of nilpotent elements of R, denoted as , in the criteria for an ideal to be 2-nil primary. This work seeks to clarify the relevance and importance of 2-nil primary ideals within the broader field of ring theory by analysing their characteristics and relationships.

The paper is organized as follows:

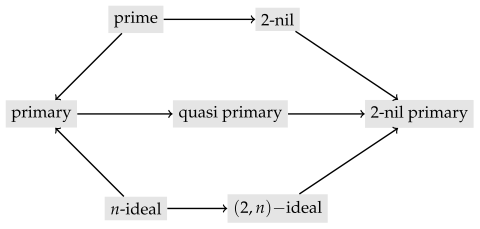

Section 1 introduces the definition of a 2-nil primary ideal (see Definition 1). From this definition, it immediately follows that every 2-nil ideal is a 2-nil primary ideal. However, the converse is not true (see Example 1). Diagram 1 summarises the relationships of 2-nil primary ideals with some well-known classes of ideals in the literature. Proposition 1 defines a 2-nil primary ideal as an ideal whose radical is a 2-nil ideal. Proposition 2 demonstrates that in a Dedekind domain, which is not a field, every 2-nil primary ideal is quasi-primary, though the converse is not true (see Example 2). Theorem 3 describes the 2-nil primary ideals of the ring of integers

, while Proposition 3 provides a characterization of fields in terms of 2-nil primary ideals. At the end of this section, we present the relationships between different classes of ideals in which all elements are nilpotent (see Diagram 2). Section two examines the image and inverse images of 2-nil primary ideals under homomorphisms (refer to Theorem 4). Theorem 5 explores transferring 2-nil primary ideals to the trivial ring extension. Theorem 7 discusses the product of 2-nil primary ideals.

In summary, this paper seeks to advance the theoretical foundation of ideal structures in commutative rings by introducing and investigating the concept of 2-nil primary ideals. Through this exploration, we aim to contribute to a deeper understanding of ring theory and its applications.

1. Some Properties of 2-nil Primary Ideals

In this section, a new class of ideals, the 2-nil primary ideal, will be introduced. We then delve into the properties and characterizations of 2-nil primary ideals. We aim to thoroughly understand their defining characteristics by presenting various theorems and proofs. Examples are included to illustrate the practical implications of these theoretical results.

Definition 1. Let R be a ring and I a proper ideal of R. We call I a 2-nil primary ideal if whenever then either or or

From the definition 1 one can immediately infer that if I is 2-nil ideal, then I is 2-nil primary ideal. The converse of this implication is not true in general, as demonstrated by the following example. However, if I is a radical ideal, then I is a 2-nil primary if and only if I is a 2-nil ideal.

Example 1. Consider and Then I is not 2-nil ideal as but and However, I is 2-nil primary ideal. To verify this claim, consider . Then It is clear that at least one of and c should be even. If , then or

The following diagram illustrates the relationship of 2-nil primary ideal with some well-known ideal classes in the literature.

However, as the reader can see in the following, there is a strict relationship between 2-nil primary ideal and 2-nil ideals. By the following proposition, we can define 2-nil primary ideal as an ideal whose radical is 2-nil, that is; a proper ideal I of a ring R is called a 2-nil primary ideal if is a 2-nil ideal of R.

Proposition 1. Let I be a proper ideal of a ring R. Then I is a 2-nil primary ideal if and only if is a 2-nil ideal.

Proof. Let such that and . Then for some Since I is 2-nil primary, we have either or This means that either or Hence, is a 2-nil ideal of R. Conversely, suppose that is a 2-nil ideal and such that . Since , we have either or or . Thus I is a 2-nil primary ideal of R. □

Next, we discuss the connection between the concepts of 2-nil primary ideal and quasi primary ideal. The next example indicates that a 2-nil primary ideal need not be a quasi primary ideal in general.

Example 2. Let and consider the ideal I is not a quasi primary ideal since but neither nor However, I is a 2-nil primary ideal of R. To show that let for some . Then and which implies that at least one of the elements , or is a multiple of 6. Hence, either or or

We conclude some conditions for a 2-nil primary ideal to be quasi primary.

Proposition 2. In any ring R with (in particular, in Dedekind domains that are not fields; for example, in discrete valuation rings) every 2-nil primary ideals are quasi primary.

Proof. Let R be a ring with Krull dimension 1, and I be a 2-nil primary ideal of R. Assume on the contrary that there are some such that . Then . Since and is prime, . Hence, or , a contradiction. Thus, I is a quasi primary ideal of R. □

In the following, we determine 2-nil primary ideals of the ring of integer

Theorem 1. In the following statements are equivalent:

- (1)

I is a 2-nil primary ideal of

- (2)

or for some prime integer p and

- (3)

I is a primary ideal of

Proof.

Let I be a nonzero 2-nil primary ideal of Then for some prime integers . Assume that . Then but , , , a contradiction. Thus and we are done.

is well-known.

It is straightforward. □

By the proposition below, we give a characterization for fields in terms of 2-nil primary ideals.

Proposition 3. For any commutative ring R, the following are equivalent:

- (1)

R is a field.

- (2)

The zero ideal is the only 2-nil primary ideal of R.

Proof.

is straightforward. Let R be a commutative ring. Suppose that I is a proper ideal of R. Then there exists a prime ideal P containing I. Hence P is 2-nil primary, so by our assumption. Thus and R is a field. □

In the following, we present a characterization of 2-nil primary ideal in terms of ideal of

Theorem 2. Let where for some prime integers . Every proper ideal of R is 2-nil primary if and only if .

Proof. Let

. Then an ideal of

R is of the form

where

for all

. Assume that

. Then

but neither

nor

nor

, a contradiction. Thus

. Conversely, let

. Then

and every ideal of

R is of the form

for some

. Since any primary ideal is 2-nil primary, we are done. Now, let

. Then

for some prime integers

and

. The claim follows from the fact that

, Remark 1 and Corollary 2.12 in [

5]. □

We recall from [

6] that a proper ideal

I of a ring

R is said to be 2-absorbing quasi-primary ideal if its radical is a 2-absorbing ideal of

R. Here, we have the following observations.

Remark 1. Any 2-absorbing quasi primary ideal contained in is 2-nil primary. To see that, let be an ideal of a ring R and such that . Then and since I is 2-absorbing primary, we have either or Hence, I is a 2-nil primary ideal of R.

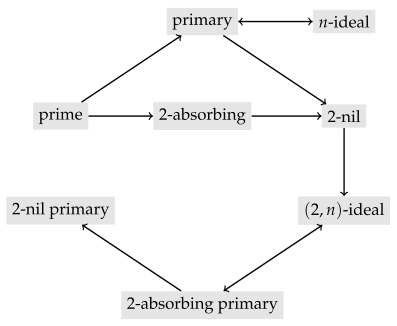

Note that if , then is a 2-nil primary ideal. Moreover, the following statements are equivalent in general:

- (1)

is a 2-absorbing ideal.

- (2)

is a 2-absorbing primary ideal.

- (3)

is a 2-absorbing quasi primary ideal.

- (4)

is a 2-nil ideal.

- (5)

is a 2-nil primary ideal.

- (6)

is a -ideal.

We enclosed the above relations between different classes of ideals, in which all elements are nilpotent, in the following diagram. Let R be a commutative ring with unity, and let I be an ideal of R such that .

The following example shows that the condition is an essential for a 2-absorbing primary ideal to be 2-nil primary ideal.

Example 3. Consider the ideal in where p and q are prime numbers, then However, neither nor nor Hence, it is not a 2-nil primary ideal. But I is 2-absorbing primary ideal. To show this, let Then and thus at least one of or is a multiple of which implies that either or or

From the above example, it is evident that the intersection of a family of 2-nil primary ideals is not necessarily a 2-nil primary ideal. However, through the next definition, we can conclude a condition for this case.

Definition 2. Let R be a ring and I be a 2-nil primary ideal of R. By Proposition 1, is a 2-nil ideal. In this case, we call I a Q-2-nil ideal of R.

Following this definition we have:

- (1)

Let R be a Noetherian ring. If I is a Q-2-nil primary ideal of R, then for some .

- (2)

Let I be an ideal of a ring R providing . Then I is a 2-nil primary ideal if and only if Q is a 2-nil primary ideal.

- (3)

Let J and K be Q-2-nil primary ideals of a ring R with the order . Then I is a Q-2-nil primary ideal.

- (4)

If J and K are Q-2-nil primary and -2-nil primary ideals of a ring R with , then is a Q-2-nil primary ideal of R.

- (5)

If are P-2-nil primary ideal of a ring R where P is a prime ideal, then is a P-2-nil primary ideal of R.

In terms of ideals of a ring, a characterization of the class of 2-nil primary ideals is presented below.

Theorem 3. Let I be a proper ideal of Then the following statements are equivalent:

- (1)

I is a 2-nil primary ideal of R.

- (2)

For any and then

- (3)

For any and then or

- (4)

If for some and J is an ideal of R then either or or

- (5)

If for some ideals of R then either or or

Proof.

Let and . Then we have either or This implies that either or Hence,

Since is an ideal which is a subset of the union of two ideals Then either or

Assume that but neither nor nor Then there exist such that and But and and this means that and which is contradicts to

Suppose that but neither nor nor . Then there exist and such that and and Since and and , we have From and we have either or Hence, we have to consider three cases as follows:

- Case 1.

Suppose that but . Since and and , we have But and imply . Now, from and , we conclude Thus, which is a contradiction.

- Case 2.

If and , then as in Case 1 we have a contradiction.

- Case 3.

-

Suppose that and . Since and we have . Now, since and , then we have Since we have On the other hand, as and , we have Since we conclude Since we get Finally, since , and , we conclude . As and , we obtain a contradiction.

Take and in

□

2. Extensions of 2-nil Primary Ideals

In this section, we are going to study quotients, subrings, localization, Cartesian products and idealizations of 2-nil primary ideals.

Theorem 4. Let be a homomorphism of a commutative rings. Then the following statements hold:

- (1))

If φ is a monomorphism, then the inverse image of a 2-nil primary ideal is 2-nil primary ideal of

- (2)

If φ is a epimorphism, then the image of 2-nil primary ideal is 2-nil primary in if

Proof. (1) Let and assume that . Then which implies either or or Since , we get or or as needed.

(2) Let such that It follows from that which implies either or or It is easy to verify that since , we have and . Hence, or or □

The following corollary is an immediate consequence of Theorem (4).

Corollary 1. Let be ideals. Then

- (1)

If I is a 2-nil primary ideal of R, then is a 2-nil primary of .

- (2)

If A is a subring of R and I is a 2-nil primary ideal of R, then is a 2-nil primary ideal of

- (3)

If is a 2-nil primary of and then I is a 2-nil primary of

Let us define the set

Theorem 5. Let S be a multiplicatively closed subset of a ring Then the following assertions hold

- 1.

If I is a 2-nil primary ideal of R and then is a 2-nil primary ideal of

- 2.

If is a 2-nil primary ideal of and then I is a 2-nil primary ideal of

Proof. (1) Suppose that Then for some Hence, or or This implies that or or Therefore, is a 2-nil primary ideal of

(2) Let for some Then which yields or or If then there exist and such that But then and If then there exist such that but which implies that Hence, Similarly, one can show that if then □

Let

A be a ring and

E an

A-module. Then

, the trivial (ring) extension of

A by

E, is the ring whose additive structure is that of the external direct sum

and whose multiplication is defined by

The basic properties of trivial ring extensions are summarized in the celebrated books [

7] and [

8]. Recall from [

7], that

Now, we investigate the possible transfer of 2-nil primary ideals to the trivial ring extension.

Theorem 6. Let A be a ring, E be an A-module and Then I is a 2-nil primary ideal of if and only if is a 2-nil primary ideal of

Proof. Let I be a 2-nil primary ideal of A and assume that for some elements of Thus, with and c are elements of Furthermore, the fact that I is 2-nil primary ideal of A implies that either or or Hence, one has that either or or Therefore, is a 2-nil primary ideal of

Conversely, assume that I is an ideal of A such that is a 2-nil primary ideal of We are going to prove that I is a 2-nil primary ideal of Let for some elements in A. Then which yields or or Then one has that or or Hence, I is a 2-nil primary ideal of □

It is natural to ask the following question: Suppose that I is a 2-nil primary ideal of . What can we say about the ideal of ? Is this ideal also a 2-nil primary ideal? The following example will address this issue.

Example 4. Let and be commutative rings and let I be 2-nil primary ideal of Then is not necessarily 2-nil primary of To show this, let and . Then I is a 2-nil primary ideal by Theorem 2. However, but neither nor nor

Proposition 4. Let and be commutative rings and I a proper ideal of . Then the following assertions are equivalent:

- (1)

is a 2-nil primary ideal of

- (2)

I is a quasi primary ideal of

- (3)

is a quasi primary ideal of

Proof.

Let such that Then Since then either or This implies that either or which proves that I is a quasi primary ideal of

From Lemma 2.2 in [

6]

It is clear. □

Theorem 7. Let and be proper ideals of and respectively. Then the following statements are equivalent:

- (1)

is a 2-nil primary ideal of

- (2)

and are quasi primary ideals of and , respectively.

- (3)

is a 2-absorbing quasi primary ideal of and

Proof.

Let then there exists Then and . Hence, or which in both cases is a contradiction. Thus, and similarly, Now, if is not quasi primary, then there exist such that , but neither nor . Hence, and since and and , a contradiction. Thus, is quasi primary in The same argument shows that is a quasi primary ideal of

Suppose that

and

are quasi primary ideals. Hence, by Proposition 4, one has that

and

are quasi primary ideals of

By Theorem 2.17(ii) in [

6], the intersection of two quasi primary ideals is 2-absorbing quasi primary ideal. So, we conclude that

is a 2-absorbing quasi primary ideal of

.

It follows from Remark 1. □

Theorem 8. Let be commutative rings and . The following assertions are equivalent:

- (1)

is a 2-nil primary ideal of R.

- (2)

is a quasi primary ideal of for some and for all .

- (3)

is a quasi primary ideal of R.

Proof.

Suppose that is a 2-nil primary ideal of R. Without loss of generality, assume on the contrary that and are proper ideals of and , respectively. Since and , we have either or . Thus, or , a contradiction. Now, we may suppose that is proper and . Let . Since but , we have either or which means that is a 2-nil quasi primary ideal of .

It is clear by Theorem 2.3 in [

6].

Straightforward. □