Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

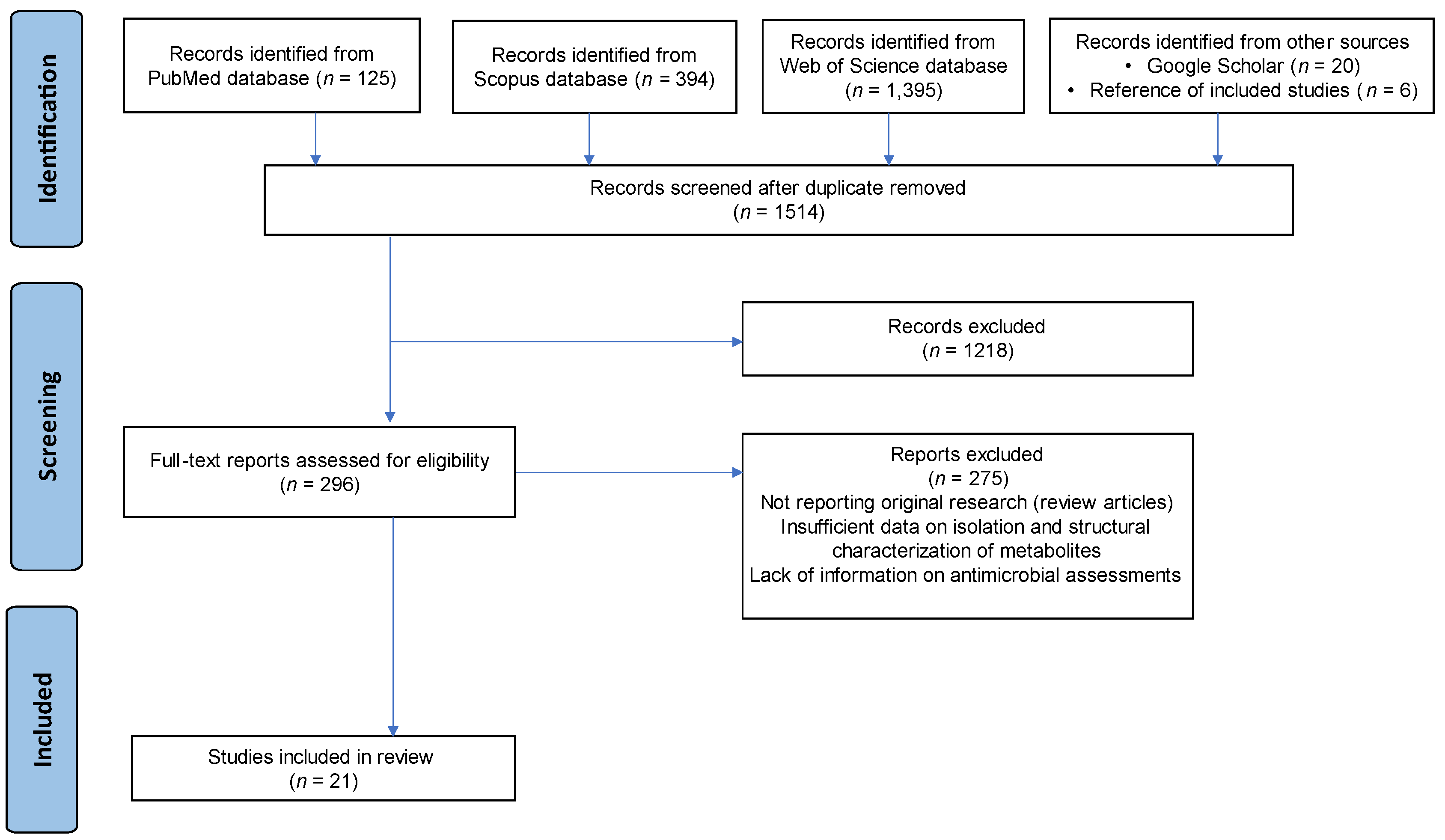

2.1. PRISMA Guidelines

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

- Original research articles published in peer-reviewed journals from 2010-2023. This approach captured the current literature while providing sufficient data.

- Studies have isolated endophytic fungi from plants or environmental sources using standard procedures.

- Investigations using spectroscopic techniques like NMR, LC-MS to elucidate structures of fungal secondary metabolites.

- Reports determining the antibacterial and/or antifungal activity of metabolites/extracts using microdilution assays or disc diffusion tests.

- Studies stating minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values for bioactive compounds against target pathogens.

- Review articles, book chapters, conference papers, and unpublished theses or dissertations. Note that these data do not represent primary data.

- Lack of details on fungal identification, compound structure elucidation, and antibacterial/antifungal evaluation methods.

- Investigations using endophytic actinomycetes or bacteria, with a specific focus on fungal secondary metabolites.

- Articles in languages other than English to maximise accessibility and analysis.

2.4. Data Extraction

- Authors and year of publication

- Fungal isolates, genus, and species (if identified); isolation source

- Isolated compounds: Name, chemical class, or structure

- Antimicrobial activity testing: target pathogens (bacterial/fungal strains),

- Activity against pathogens: Specified as demonstrated activity against the tested strains.

2.5. Quality Assessment

2.6. Data Synthesis and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

- Not reporting original research (review articles, conference abstracts)

- Insufficient data on the isolation and structural characterisation of metabolites

- Lack of information about antimicrobial assessments

3.2. Sources of Endophytic Fungi

3.3. Antimicrobial Activity Of Secondary Metabolites

3.4. Antimicrobial Activity Against Bacteria

3.4.1. Staphylococcus Aureus

3.4.2. Enterococcus spp.

3.4.3. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa

3.4.4. Escherichia Coli

| Bacteria | Secondary metabolites | fungal source |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1-H-indene 1-methanol acetate, azulene | Curvularia eragrostidis |

| Altersolanol, fusaraichromenone | Fusarium spp. | |

| Violaceols | Trichoderma polyalthiae | |

| 5α,8α-epidioxyergosta-6,22-dien-3β-ol, ergosta-7,22-dien-3β,5α,6β-triol | Pichia guilliermondii | |

| Palitantin, fusarielin, cytosporins | Pseudopestalotiopsis spp. | |

| Emodin, quesinol, quesin | Aspergillus spp. | |

| Nigerasperone C, asperpyrone A | Aspergillus niger | |

| 2-methoxy-6-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone, penicillic acid | Aspergillus, Alternaria | |

| Enterococcus spp. (E. faecalis and E. faecium) | Pterin-6 carboxylic acid, 1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid | Fusarium oxysporum |

| Rubrofusarin B, aspergillusol A | Aspergillus niger | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Ergosta-5,7,22-trienol | Pichia guilliermondii |

| Rubrofusarin B, fonsecin | Aspergillus niger | |

| 1-H-indene 1-methanol acetate, azulene | Curvularia eragrostidis | |

| Emodin, quesinol, quesin | Aspergillus spp. | |

| Escherichia coli | 1-H-indene 1-methanol acetate | Curvularia eragrostidis |

| Emodin, questinol, questin | Aspergillus spp. | |

| Palitantin, fusarielin, cytosporins | Pseudopestalotiopsis spp. | |

| Rubrofusarin B, aspergillusol A | Aspergillus niger | |

| 2-methoxy-6-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone, penicillic acid | Aspergillus, Alternaria | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Ergosta-7,22-dien-3β,5α,6β-triol, 5α,8α-epidioxyergosta-6,22-dien-3β-ol | Pichia guilliermondii |

| 9-Octadecenoic acid Z-, methyl ester, pentadecanoic acid, 14-methyl-, methyl ester | Aspergillus niger, Trichoderma lixii | |

| Azulene, 1-H-indene 1-methanol acetate, N, N-diphenyl-2-nitro thio benzamide | Curvularia eragrostidis | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 9-Octadecenoic acid Z-, methyl ester, pentadecanoic acid, 14-methyl-, methyl ester | Aspergillus niger, Trichoderma lixii |

| Palitantin, cytosporins | Pseudopestalotiopsis spp. |

3.4.5. Klebsiella Pneumoniae

3.4.6. Acinetobacter Baumannii

3.5. Antimicrobial Activity Against Fungi

3.5.1. Candida Albicans

| Fungi | Secondary metabolites | Fungi sources |

| Candida albicans | Violaceols | Trichoderma polyalthiae |

| 5α,8α-epidioxyergosta-6,22-dien-3β-ol, ergosta-5,7,22-trienol | Pichia guilliermondii | |

| Azulene, N, N-diphenyl-2-nitro thio benzamide | Curvularia eragrostidis | |

| Palitantin, cytosporins | Pseudopestalotiopsis spp. | |

| Alternsolanol, fusaraichromenone | Fusarium spp. | |

| Aspergillusol A, 2-(hydroxyimino)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl) propanoic acid | Aspergillus niger | |

| Emodin, questinol, quesin | Aspergillus spp. | |

| Trichophyton marneffei and Microsporum gypseum | 2-phenylacetic acid, Z-methyl 4-(isobutyryloxy) but-3-enoate, 5-pentyldihydrofuran-2(3H)-one | Nigrospora spp. |

| Aspergillus spp. | Cladosporin, 50-hydroxyasperentin | Endophytic fungi in Zygophyllum mandavillei |

| Azulene, 1-H-indene 1 methanol acetate, N, N-diphenyl-2-nitro thio benzamide | Curvularia eragrostidis | |

| Ergosta-7,22-dien-3β,5α,6β-triol, 5α,8α-epidioxyergosta-6,22-dien-3β-ol | Pichia guilliermondii |

3.5.2. Aspergillus spp.

3.5.3. Dermatophyte

3.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Acknowledgements

References

- Alam B, Lǐ J, Gě Q, Khan MA, Gōng J, Mehmood S, et al. Endophytic Fungi: From Symbiosis to Secondary Metabolite Communications or Vice Versa? Vol. 12, Frontiers in Plant Science. 2021.

- Verma H, Kumar D, Kumar V, Kumari M, Singh SK, Sharma VK, et al. The potential application of endophytes in management of stress from drought and salinity in crop plants. Microorganisms. 2021;9(8). [CrossRef]

- Rangel LI, Hamilton O, de Jonge R, Bolton MD. Fungal social influencers: secondary metabolites as a platform for shaping the plant-associated community. Vol. 108, Plant Journal. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Keller NP. Fungal secondary metabolism: regulation, function and drug discovery. Vol. 17, Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Dias DA, Urban S, Roessner U. A Historical overview of natural products in drug discovery. Vol. 2, Metabolites. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari P, Bae H. Endophytic Fungi: Key Insights, Emerging Prospects, and Challenges in Natural Product Drug Discovery. Vol. 10, Microorganisms. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Salam MA, Al-Amin MY, Salam MT, Pawar JS, Akhter N, Rabaan AA, et al. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Vol. 11, Healthcare (Switzerland). 2023. [CrossRef]

- WHO. No time to wait: Securing the future from drug-resistant infections. Artforum International. 2019;54(April).

- Low CY, Rotstein C. Emerging fungal infections in immunocompromised patients. F1000 Med Rep. 2011;3(1). [CrossRef]

- Denning, DW. Antifungal drug resistance: an update. European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 2022;29(2). [CrossRef]

- Pusztahelyi T, Holb IJ, Pócsi I. Secondary metabolites in fungus-plant interactions. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6(AUG). [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. The BMJ. 2021 Mar 29;372. [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016 Dec 5;5(1):210. [CrossRef]

- Wells G, Wells G, Shea B, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. 2014;

- Ratnaweera PB, de Silva ED, Williams DE, Andersen RJ. Antimicrobial activities of endophytic fungi obtained from the arid zone invasive plant Opuntia dillenii and the isolation of equisetin, from endophytic Fusarium sp. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15(1).

- Zhang D, Sun W, Xu W, Ji C, Zhou Y, Sun J, et al. Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Activity of Endophytic Fungi from Lagopsis supina. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2023;33(4).

- Santra HK, Banerjee D. Broad-Spectrum Antimicrobial Action of Cell-Free Culture Extracts and Volatile Organic Compounds Produced by Endophytic Fungi Curvularia Eragrostidis. Front Microbiol. 2022 Jun 23;13.

- Zhao J, Mou Y, Shan T, Li Y, Zhou L, Wang M, et al. Antimicrobial metabolites from the endophytic fungus pichia guilliermondii Isolated from Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis. Molecules. 2010 Nov;15(11):7961–70.

- Xiao J, Zhang Q, Gao YQ, Tang JJ, Zhang AL, Gao JM. Secondary metabolites from the endophytic botryosphaeria dothidea of melia azedarach and their antifungal, antibacterial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62(16).

- Leylaie S, Zafari D. Antiproliferative and antimicrobial activities of secondary metabolites and phylogenetic study of endophytic Trichoderma Species From Vinca Plants. Front Microbiol. 2018;9(JUL).

- Abdelalatif AM, Elwakil BH, Mohamed MZ, Hagar M, Olama ZA. Fungal Secondary Metabolites/Dicationic Pyridinium Iodide Combinations in Combat against Multi-Drug Resistant Microorganisms. Molecules. 2023;28(6).

- Zhang XQ, Qu HR, Bao SS, Deng ZS, Guo ZY. Secondary Metabolites from the Endophytic Fungus Xylariales sp. and their Antimicrobial Activity. Chem Nat Compd. 2020;56(3).

- Supaphon P, Preedanon S. Evaluation of in vitro alpha-glucosidase inhibitory, antimicrobial, and cytotoxic activities of secondary metabolites from the endophytic fungus, Nigrospora sphaerica, isolated from Helianthus annuus. Ann Microbiol. 2019;69(13).

- Liu YJ, Zhang JL, Li C, Mu XG, Liu XL, Wang L, et al. Antimicrobial Secondary Metabolites from the Seawater-Derived Fungus Aspergillus sydowii SW9. Molecules. 2019;24(24).

- Said G, Hou XM, Liu X, Chao R, Jiang YY, Zheng JY, et al. Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Activities of Secondary Metabolites from the Soft Coral Derived Fungus Aspergillus sp. Chem Nat Compd. 2019 May 15;55(3):531–3.

- Hiranrat W, Hiranrat A, Supaphon P. Antimicrobial Activity of Secondary Metabolites from Endophytic Fungus Fusarium sp. Isolated from Eichhornia crassipes Linn. ASEAN Journal of Scientific and Technological Reports. 2021;24(3).

- Nuankeaw K, Chaiyosang B, Suebrasri T, Kanokmedhakul S, Lumyong S, Boonlue S. First report of secondary metabolites, Violaceol I and Violaceol II produced by endophytic fungus, Trichoderma polyalthiae and their antimicrobial activity. Mycoscience. 2020;61(1).

- Ajah VN, Okolo C, Okezie U, Ukwubile C, Asekunowo AK, Umeokoli B, et al. Secondary metabolites of mangrove-derived endophytic fungus, Pseudopestalotiopsis species investigated for antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. Journal of Current Biomedical Research. 2023;3(5, September-October).

- Quang TH, Phong NV, Anh LN, Hanh TTH, Cuong NX, Ngan NTT, et al. Secondary metabolites from a peanut-associated fungus Aspergillus niger IMBC-NMTP01 with cytotoxic, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activities. Nat Prod Res. 2022;36(5):1215–23.

- Dhevi, V. Sundar R, Arunachalam S. Endophytic fungi of Tradescantia pallida mediated targeting of Multi-Drug resistant human pathogens. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2024;31(3).

- Yehia RS, Osman GH, Assaggaf H, Salem R, Mohamed MSM. Isolation of potential antimicrobial metabolites from endophytic fungus Cladosporium cladosporioides from endemic plant Zygophyllum mandavillei. South African Journal of Botany. 2020;134.

- Arendrup MC, Patterson TF. Multidrug-resistant candida: Epidemiology, molecular mechanisms, and treatment. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2017;216.

- Onyishi CU, May RC. Human immune polymorphisms associated with the risk of cryptococcal disease. Vol. 165, Immunology. 2022.

- Jarboe LR, Royce LA, Liu P. Understanding biocatalyst inhibition by carboxylic acids. Vol. 4, Frontiers in Microbiology. 2013.

- Ibrahim SRM, Mohamed SGA, Alsaadi BH, Althubyani MM, Awari ZI, Hussein HGA, et al. Secondary Metabolites, Biological Activities, and Industrial and Biotechnological Importance of Aspergillus sydowii. Vol. 21, Marine Drugs. 2023.

- Dufour N, Rao RP. Secondary metabolites and other small molecules as intercellular pathogenic signals. Vol. 314, FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2011.

- Keswani C, Singh HB, García-Estrada C, Caradus J, He YW, Mezaache-Aichour S, et al. Antimicrobial secondary metabolites from agriculturally important bacteria as next-generation pesticides. Vol. 104, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2020.

- Karnwal A, Malik T. Exploring the untapped potential of naturally occurring antimicrobial compounds: novel advancements in food preservation for enhanced safety and sustainability. Vol. 8, Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems. 2024.

- Hyde KD, Baldrian P, Chen Y, Thilini Chethana KW, De Hoog S, Doilom M, et al. Current trends, limitations and future research in the fungi? Fungal Divers. 2024;125(1).

- Marshall DD, Powers R. Beyond the paradigm: Combining mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance for metabolomics. Vol. 100, Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. 2017.

- Garza DR, Dutilh BE. From cultured to uncultured genome sequences: Metagenomics and modeling microbial ecosystems. Vol. 72, Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2015.

- Caesar LK, Montaser R, Keller NP, Kelleher NL. Metabolomics and genomics in natural products research: Complementary tools for targeting new chemical entities. Vol. 38, Natural Product Reports. 2021.

- Vaou N, Stavropoulou E, Voidarou C, Tsakris Z, Rozos G, Tsigalou C, et al. Interactions between Medical Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds: Focus on Antimicrobial Combination Effects. Vol. 11, Antibiotics. 2022.

| Plant Species | Plant Source |

| Mangifera Indica | Roots |

| Catharanthus roseus | Healthy leaves |

| Rhizophora racemosa | Root |

| Melia azedarach L. | Stem bark |

| Distylium chinense | Leaves |

| Helianthus annuus | Leaves |

| Eichhornia crassipes Linn | Leaves |

| Opontia dillenii | Cladodes and flowers |

| Rhizophora racemosa | Root |

| Olea europaea cv. Cobrançosa | Leaves |

| Polygonatum polyphyllum var. yunnanensis | Healthy rhizomes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).