Submitted:

25 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Survival Trials

2.2. Quantitative Gene Expression

2.2.1. Kidney

2.2.2. Liver

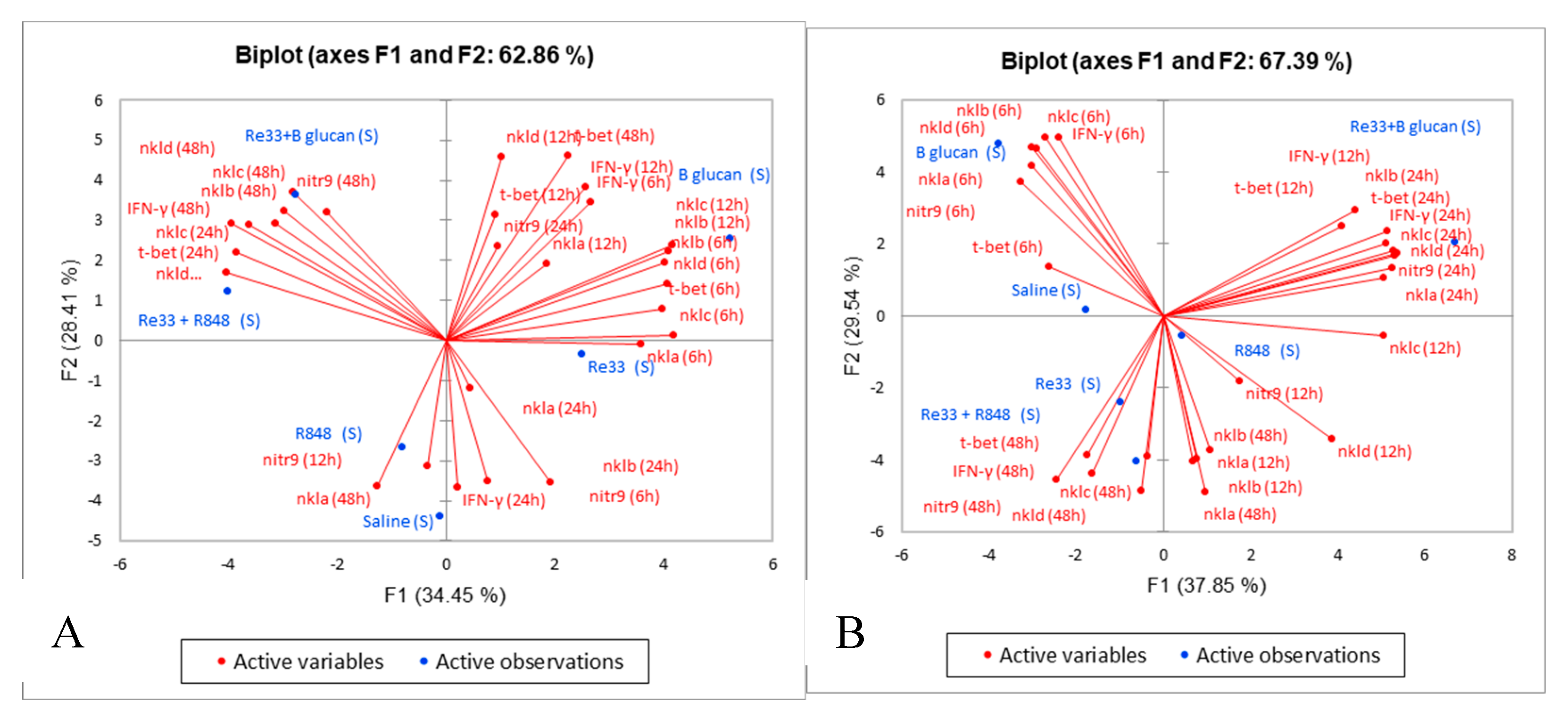

2.3. Principal Component Analysis

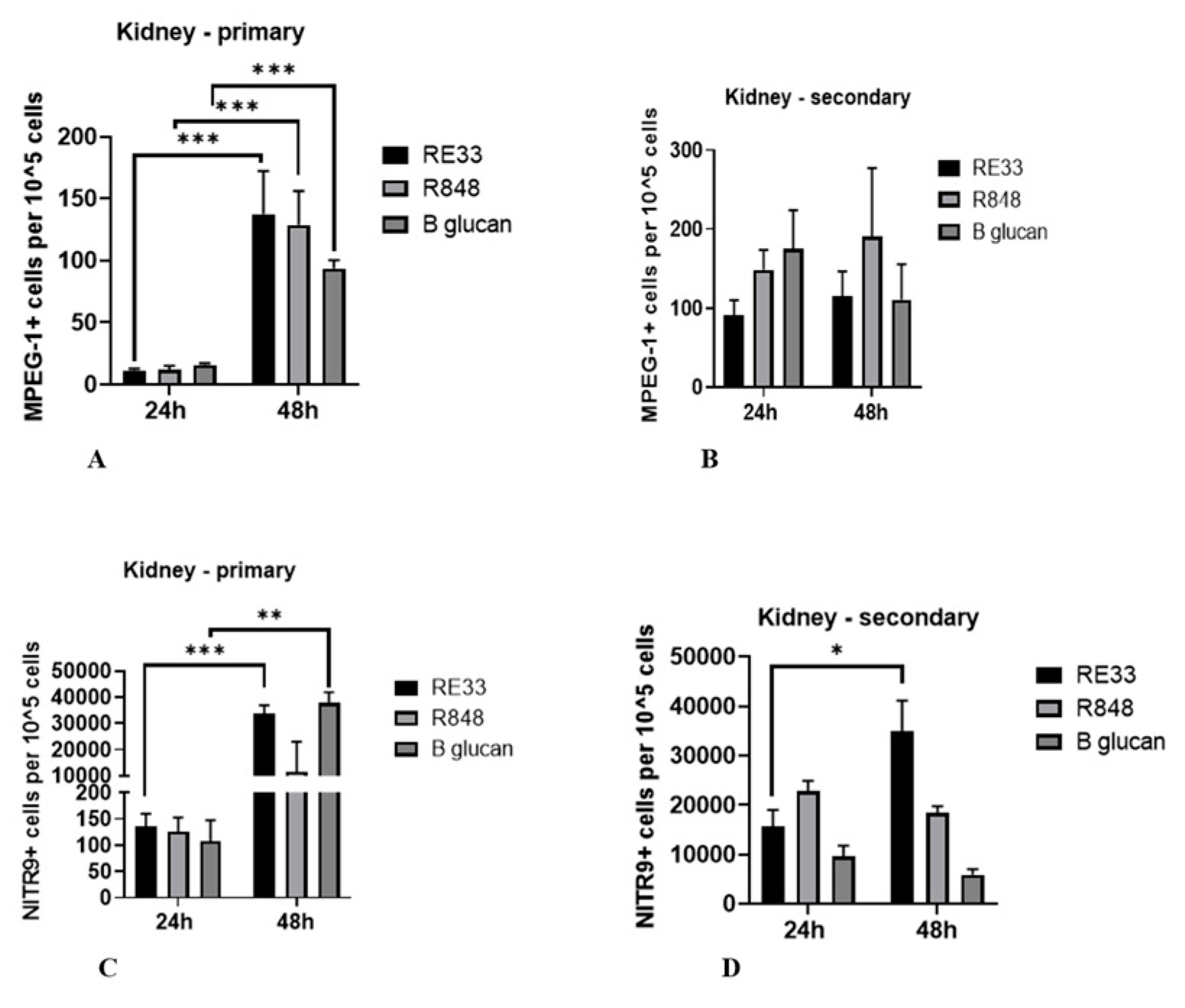

2.4. Expression of MPEG-1+ and NITR9+ Leukocytes in Kidney and Liver Tissues

2.4.1. Kidney

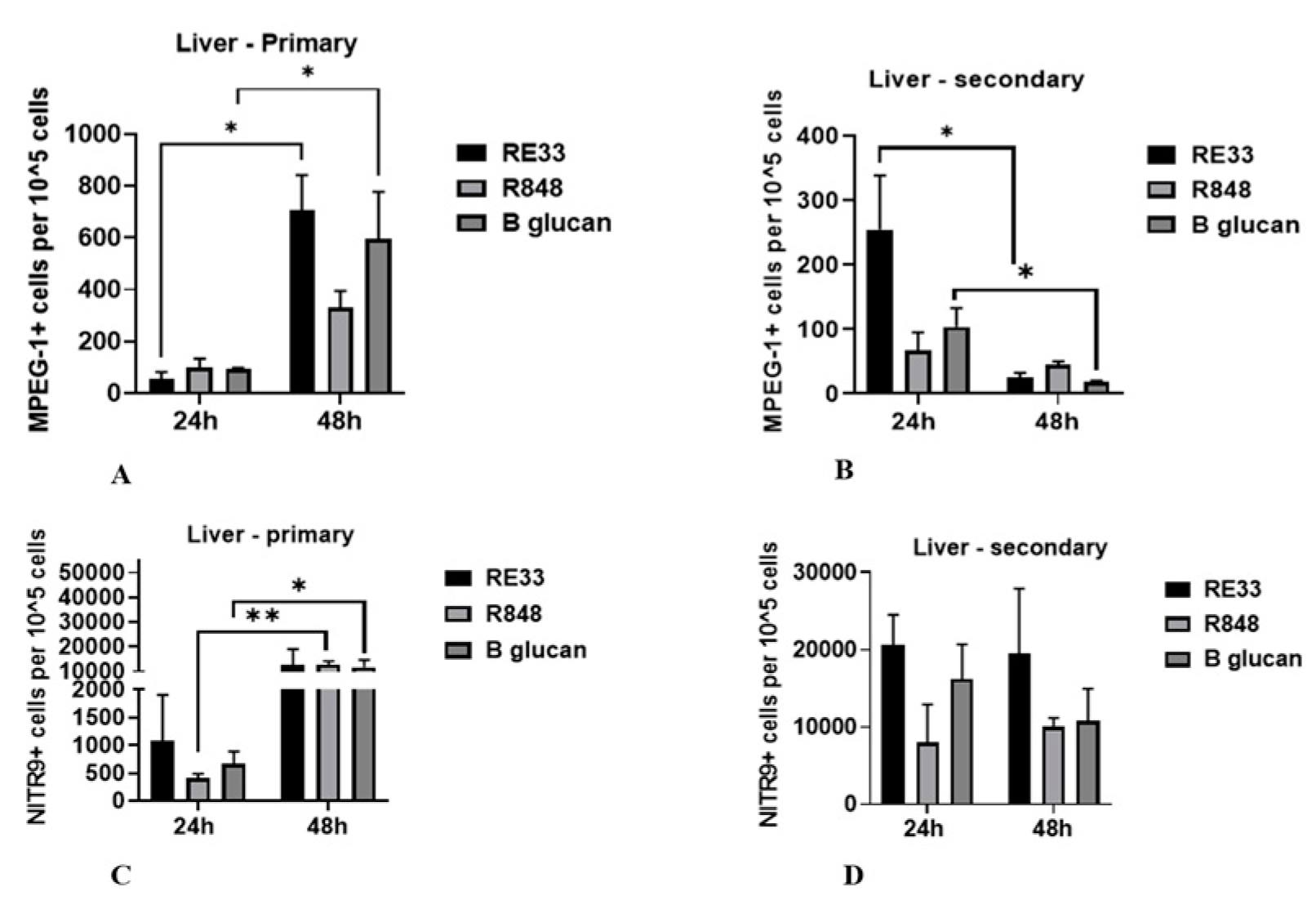

2.2.2. Liver

3. Discussion

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Zebrafish Care

4.2. Innate Immune Training

4.3. Survival Trials

4.3.1. Preparation of Bacterial Cultures

4.3.2. Lethal Dose (LD50) Determination

4.3.3. Bacterial Infections

4.4. Quantifying Gene Expression

| Treatment | Tissue | Upregulated fold change post E. ictaluri challenge |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-100 | 101-1000 | >1000 | ||

| Sham control | Liver |

Ifnγ (12h) Nklc (48h) |

Ifnγ (6h) |

Ifnγ (48h) |

| Kidney |

Nitr9 (6h) Nitr9 (12h) Nitr9 (48h) Nkla (48h) |

Ifnγ (24h) | ||

| RE33® | Liver |

Nkld (12h) Nkla (48h) |

Nitr9 (6h) Nkla (12h) |

Ifnγ (48h) |

| Kidney | Nkld (12h) |

T-bet (6h) |

||

| beta glucan | Liver |

Nkla (6h) Nklb (6h) Nkld (6h) |

Ifnγ (6h) Nklc (6h) |

|

| Kidney |

Ifnγ (24h) Nkla (48h) |

Ifnγ (12h) Nkld (12h) |

Nklb (6h) |

|

| beta glucan + RE33® | Liver |

Nkld (12h) Nitr9 (24h) Nkla (24h) Nklb (24h) Nklc (24h) Nkld (24h) |

Ifnγ (24h) T-bet (24h) |

|

| Kidney | Nkla (48h) |

Nkld (12h) Nklb (24h) Nkld (24h) Ifnγ (48h) |

||

| R848 | Liver | Nitr9 (12h) | ||

| Kidney | Nkla (48h) | |||

| R848 + RE33® | Liver | Nitr9 (24h) | Ifnγ (48h) | |

| Kidney |

Nkla (48h) |

Nkld (24h) | Ifnγ (48h) | |

| Gene | Oligonucleotide sequences (5’–3’) | GenBank Accession No. |

|---|---|---|

| arp |

Fwd: CTGCAAAGATGCCCAGGGA Rev: TTGGAGCCGACATTGTCTGC Probe:[6~FAM]TTCTGAAAATCATCCAACTGCTGGATGACTACC [BHQ1a~ Q] [8] |

NM_131580 |

| ifnγ |

Fwd: CTTTCCAGGCAAGAGTGCAGA Rev: TCAGCTCAAACAAAGCCTTTCG Probe:[6~FAM]AACGCTATGGGCGATCAAGGAAAACGAC[BHQ1a~ Q] [8] |

NM_212864 |

| t-bet |

Fwd:GATCAAGCTCTCTCTGTGATAG Rev:GCTAAAGTCACACAGGTCT Probe:[6~FAM]TTCTGAAGGTCACGGTCACA[BHQ1a~Q] * |

NM_001170599.1 |

| nitr9 |

Fwd: GTCAAAGGGACAAGGCTGATAGTT Rev:GTTCAAAACAGTGCATGTAAGACTCA Probe: [6~FAM]CAAGGTTTGGAAAAGCAC[BHQ1a~Q] [9] |

AY570237.1 |

| nkla |

Fwd: TTTCTGGTCGGCTTGCTCAT Rev: TTCTCATTCACAGCCCGGTC Probe:[6~FAM]TCTGCAGCTCACTGGGAGGTTCGTGA[BHQ1a~Q] |

NM_001311794 |

| nklb |

Fwd: TCCGCAACATCTTTCTGGTCA Rev: AGCCTGCTCATGAATGAAAATGA Probe:[6~FAM]CACGCCTGCAAATCTGAACCACCCA[BHQ1a~Q] |

NM_001311792 |

| nklc |

Fwd: CTGCTTGTGCTGCTCACTTG Rev: AGCACACATGGAGATGAGAACA Probe: [6~FAM]GGGCTTGCAAGTGGGCCATGGGAA[BHQ1a~Q] |

NM_001311793.1 |

| nkld |

Fwd: ACCCTGCTCATCTCCTCTGT Rev: CCCCAGCTAAAGCAAAACCC Probe:[6~FAM]TGCCTGGGATGTGCTGGGCTTGCAA[BHQ1a~Q] |

NM_212741.1 |

4.5. Principal Component Analysis

4.6. Nitr9 and Mpeg-1 Expression by Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting (FACS)

4.7. Data Analysis and Statistical Evaluation

Acknowledgments

References

- Hohn C, Petrie-Hanson L. Rag1−/− Mutant Zebrafish Demonstrate Specific Protection following Bacterial Re-Exposure. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(9):e44451.

- Muire PJ, Hanson LA, Wills R, Petrie-Hanson L. Differential gene expression following TLR stimulation in rag1-/- mutant zebrafish tissues and morphological descriptions of lymphocyte-like cell populations. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(9):e0184077.

- Krishnavajhala A, Muire PJ, Hanson L, Wan H, McCarthy F, Zhou A, et al. Transcriptome Changes Associated with Protective Immunity in T and B Cell-Deficient Rag1-/- Mutant Zebrafish. International Journal of Immunology. 2017;5(2):20.

- Peterman B, Petrie-Hanson L. Beta-glucan induced trained immunity is associated with changes in gut Nccrp-1+ and Mpeg-1+cell populations in rag1-/- zebrafish. Journal of Aquaculture, Marine Biology & Ecology. 2021;2021(01).

- Petit J, Wiegertjes GF. Long-lived effects of administering β-glucans: Indications for trained immunity in fish. Developmental & Comparative Immunology. 2016;64:93-102. [CrossRef]

- Netea MG, Domínguez-Andrés J, Barreiro LB, Chavakis T, Divangahi M, Fuchs E, et al. Defining trained immunity and its role in health and disease. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2020;20(6):375-88. [CrossRef]

- Netea MG, Joosten LAB, Latz E, Mills KHG, Natoli G, Stunnenberg HG, et al. Trained immunity: A program of innate immune memory in health and disease. Science. 2016;352(6284):aaf1098. [CrossRef]

- Petrie-Hanson L, Peterman AEB. Trained Immunity Provides Long-Term Protection against Bacterial Infections in Channel Catfish. Pathogens. 2022;11(10):1140. [CrossRef]

- Dagenais A, Villalba-Guerrero C, Olivier M. Trained immunity: A “new” weapon in the fight against infectious diseases. Frontiers in Immunology. 2023;14:1147476.

- De Zuani M, Frič J. Train the Trainer: Hematopoietic Stem Cell Control of Trained Immunity. Frontiers in Immunology. 2022;13:827250.

- Kain BN, Luna P, Hormaechea Agulla D, Maneix L, Morales-Mantilla DE, Le D, et al. Specificity and Heterogeneity of Trained Immunity in Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells. Blood. 2021;138(Supplement 1):2149-. [CrossRef]

- Ifrim DC, Quintin J, Joosten LAB, Jacobs C, Jansen T, Jacobs L, et al. Trained Immunity or Tolerance: Opposing Functional Programs Induced in Human Monocytes after Engagement of Various Pattern Recognition Receptors. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. 2014;21(4):534-45. [CrossRef]

- Kawai T, Akira S. TLR signaling. Cell Death & Differentiation. 2006;13(5):816-25.

- Nishizawa T, Takami I, Kokawa Y, Yoshimizu M. Fish immunization using a synthetic double-stranded RNA Poly (I: C), an interferon inducer, offers protection against RGNNV, a fish nodavirus. Diseases of aquatic organisms. 2009;83(2):115-22.

- Jensen I, Albuquerque A, Sommer A-I, Robertsen B. Effect of poly I: C on the expression of Mx proteins and resistance against infection by infectious salmon anaemia virus in Atlantic salmon. Fish & shellfish immunology. 2002;13(4):311-26.

- Dong X, Su B, Zhou S, Shang M, Yan H, Liu F, et al. Identification and expression analysis of toll-like receptor genes (TLR8 and TLR9) in mucosal tissues of turbot (Scophthalmus maximus L.) following bacterial challenge. Fish & shellfish immunology. 2016;58:309-17.

- Souza-Fonseca-Guimaraes F, Parlato M, Fitting C, Cavaillon J-M, Adib-Conquy M. NK Cell Tolerance to TLR Agonists Mediated by Regulatory T Cells after Polymicrobial Sepsis. The Journal of Immunology. 2012;188(12):5850-8. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Z-x, Sun L. Immune effects of R848: Evidences that suggest an essential role of TLR7/8-induced, Myd88- and NF-κB-dependent signaling in the antiviral immunity of Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Developmental & Comparative Immunology. 2015;49(1):113-20.

- Zhou Y, Chen X, Cao Z, Li J, Long H, Wu Y, et al. R848 Is Involved in the Antibacterial Immune Response of Golden Pompano (Trachinotus ovatus) Through TLR7/8-MyD88-NF-κB-Signaling Pathway. Frontiers in Immunology. 2021;11:617522.

- Klesius PH, Shoemaker CA. Modified live Edwardsiella ictaluri against enteric septicemia in channel catfish. Google Patents; 2000.

- Petrie-Hanson L, Romano CL, Mackey RB, Khosravi P, Hohn CM, Boyle CR. Evaluation of Zebrafish Danio rerio as a Model for Enteric Septicemia of Catfish (ESC). Journal of Aquatic Animal Health. 2007;19(3):151-8. [CrossRef]

- Pereiro P, Varela M, Diaz-Rosales P, Romero A, Dios S, Figueras A, et al. Zebrafish Nk-lysins: First insights about their cellular and functional diversification. Developmental & Comparative Immunology. 2015;51(1):148-59. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Long H, Sun L. A NK-lysin from Cynoglossus semilaevis enhances antimicrobial defense against bacterial and viral pathogens. Developmental & Comparative Immunology. 2013;40(3-4):258-65. [CrossRef]

- Klose Christoph SN, Blatz K, d’Hargues Y, Hernandez Pedro P, Kofoed-Nielsen M, Ripka Juliane F, et al. The Transcription Factor T-bet Is Induced by IL-15 and Thymic Agonist Selection and Controls CD8αα+ Intraepithelial Lymphocyte Development. Immunity. 2014;41(2):230-43.

- Shah RN, Rodriguez-Nunez I, Eason DD, Haire RN, Bertrand JY, Wittamer V, et al. Development and Characterization of Anti-Nitr9 Antibodies. Advances in Hematology. 2012;2012:1-9. [CrossRef]

- Wei S, Zhou J-m, Chen X, Shah RN, Liu J, Orcutt TM, et al. The zebrafish activating immune receptor Nitr9 signals via Dap12. Immunogenetics. 2007;59(10):813-21. [CrossRef]

- Vivier E, Tomasello E, Baratin M, Walzer T, Ugolini S. Functions of natural killer cells. Nature Immunology. 2008;9(5):503-10.

- Riksen NP, Netea MG. Immunometabolic control of trained immunity. Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 2021;77:100897. [CrossRef]

- Librán-Pérez M, Costa MM, Figueras A, Novoa B. β-glucan administration induces metabolic changes and differential survival rates after bacterial or viral infection in turbot (Scophthalmus maximus). Fish & Shellfish Immunology. 2018;82:173-82. [CrossRef]

- Dawood MAO, Koshio S, Esteban MÁ. Beneficial roles of feed additives as immunostimulants in aquaculture: a review. Reviews in Aquaculture. 2018;10(4):950-74. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Grishin AV, Ford HR. Experimental Anti-Inflammatory Drug Semapimod Inhibits TLR Signaling by Targeting the TLR Chaperone gp96. The Journal of Immunology. 2016;196(12):5130-7. [CrossRef]

- Kumar L, Greiner R. Gene expression based survival prediction for cancer patients—A topic modeling approach. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(11):e0224446. [CrossRef]

- Gravendeel LAM, Kouwenhoven MCM, Gevaert O, de Rooi JJ, Stubbs AP, Duijm JE, et al. Intrinsic Gene Expression Profiles of Gliomas Are a Better Predictor of Survival than Histology. Cancer Res. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Shen Y-J, Huang S-G. Improve Survival Prediction Using Principal Components of Gene Expression Data. Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics. 2006;4(2):110-9. [CrossRef]

- White RJ, Collins JE, Sealy IM, Wali N, Dooley CM, Digby Z, et al. A high-resolution mRNA expression time course of embryonic development in zebrafish. eLife. 2017;6:e30860.

- Al-Sulaiti MM, Soubra L, Ramadan GA, Ahmed AQS, Al-Ghouti MA. Total Hg levels distribution in fish and fish products and their relationships with fish types, weights, and protein and lipid contents: A multivariate analysis. Food Chemistry. 2023;421:136163. [CrossRef]

- Gavery MR, Roberts SB. Predominant intragenic methylation is associated with gene expression characteristics in a bivalve mollusc. PeerJ. 2013;1:e215. [CrossRef]

- Peng H, Jiang X, Chen Y, Sojka DK, Wei H, Gao X, et al. Liver-resident NK cells confer adaptive immunity in skin-contact inflammation. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123(4):1444. [CrossRef]

- Bermudez LE, Wu M, Young LS. Interleukin-12-stimulated natural killer cells can activate human macrophages to inhibit growth of Mycobacterium avium. Infection and immunity. 1995;63(10):4099-104. [CrossRef]

- Muire PJ, Hanson LA, Wills R, Petrie-Hanson L. Differential gene expression following TLR stimulation in rag1-/-mutant zebrafish tissues and morphological descriptions of lymphocyte-like cell populations. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(9):e0184077.

- Schuster IS, Andoniou CE, Degli-Esposti MA. Tissue-resident memory NK cells: Homing in on local effectors and regulators. Immunological Reviews. 2024;323(1):54-60. [CrossRef]

- Petrie-Hanson L, Hohn C, Hanson L. Characterization of rag1 mutant zebrafish leukocytes. BMC Immunology. 2009;10(1):8. [CrossRef]

- Elibol-Fleming, B. Effects of Edwardsiella ictaluri infection on transcriptional expression of selected immune-relevant genes in channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus: Doctoral dissertation. Mississippi State University, Mississippi State; 2006.

- Ju B, Xu Y, He J, Liao J, Yan T, Hew CL, et al. Faithful expression of green fluorescent protein(GFP) in transgenic zebrafish embryos under control of zebrafish gene promoters. Developmental genetics. 1999;25(2):158-67.

- Pfaffl, M.W. Quantification strategies in real-time PCR. AZ of quantitative PCR. 2004;1:89-113.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).