Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The mathematical Model

2.1. Functional Subsystems and Representation

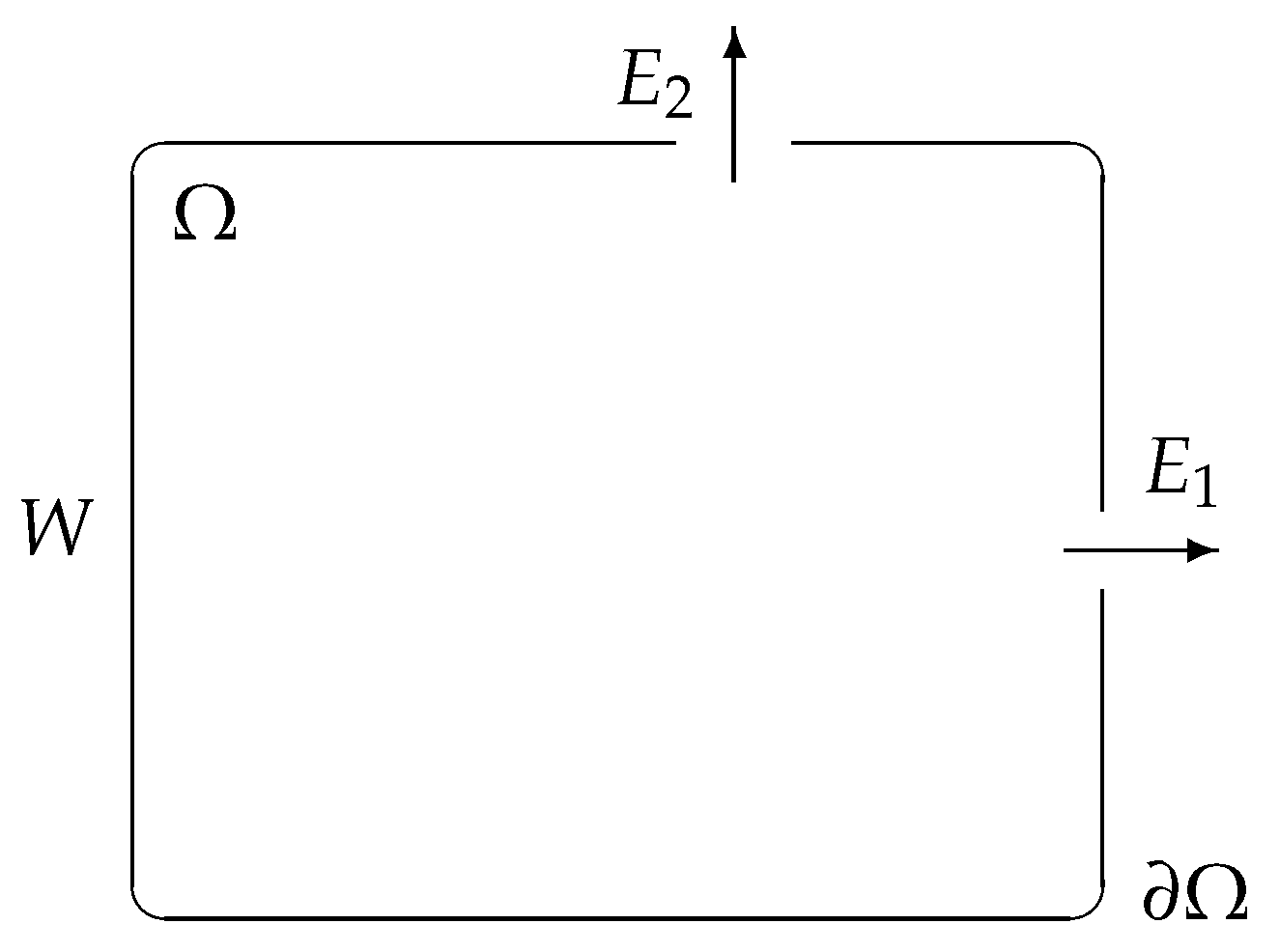

- The boundary , including the exit zone . Note that E could be the finite union of disjoint sets, i.e., the domain may have several exit zones. For instance, in Figure 1 there are two exits and .

- The remaining of the boundary is an impenetrable wall , see Figure 1.

- For simplicity, the domain is assumed to be convex.

- The domain is characterized by a parameter that accounts for the quality of the environment, where represents the worst quality, forcing pedestrians to stop, and represents the best quality, allowing high speeds.

- The position is assumed to be a continuous variable.

- For the velocity, denoted by in polar coordinates, it is assumed that the speed v is a continuous deterministic variable which evolves in time and space according to macroscopic effects determined by the overall dynamics, while the velocity direction is a discrete variable, heterogeneously distributed among pedestrians, attaining values in the setwith cardinal .

- A disease-related state given by a categorical variable in the set with cardinal . The set depends on the case under study. Two examples presented in [3] are with (each class S , E, I, and R corresponds to susceptible, exposed, infected, and recovered, respectively) and with (where V corresponds to a vaccinated class).

-

A state that represents a pedestrian’s level of awareness about the risk of contracting an infectious disease. We denote this variable by and define a discrete set of levelsThe lowest level corresponds to the state in which a pedestrian is not aware of a possible contagion (their only objective is to reach the exit). On the other hand, the highest level corresponds to the state in which a pedestrian is absolutely aware of a possible contagion and, therefore, their priority will be to avoid high densities. It is worth stressing that even in that case, pedestrians do not lose the objective of leaving the room.

2.2. Mathematical Structure

- 1.

- moving towards the exit;

- 2.

- avoiding collision with walls;

- 3.

- moving towards less congested areas;

- 4.

- attraction to follow the main stream;

- 5.

- disease contagion;

- 6.

-

pedestrian awareness.Note the distinction between the first two items, which are related to purely geometric characteristics of the domain, and the subsequent four, which take into consideration that pedestrian behavior is strongly affected by the presence of other pedestrians. Thus, we split the interaction term into two terms

- with models changes in the velocity direction. The quantity is the probability that an individual moving with direction , adjusts its direction into as a consequence of the domain geometry (e.g., walls or exit doors).

-

with , and models inter-pedestrian interactions. In this study, we assume three different types of interactions between pedestrians which are modeled by the following transition probabilities:

- *

- describe the probability that a -individual undergoes a transition into the disease state as a consequence of an interaction with a -individual,

- *

- represents the probability that an individual with level of awareness changes to level as a consequence of an interaction with an individual with level of awareness , and

- *

-

denotes is the probability that an individual moving with direction changes its direction into after an interaction with a pedestrian walking with direction . In Section 2.3.2 we will see that this transition also depends indirectly on the awareness level of the individual.Then, the compact form of inter-pedestrian interactions transition probability is given by the product

2.3. Modeling the Interactions

- test particles with micro-state which are representative of the whole system;

- field particles with micro-state , whose presence triggers the interactions of the candidate particles and;

- candidate particles with micro-state , which can reach in probability the state of the test particles after individual based interactions with field particles or with the environment.

2.3.1. Dynamics Induced by the Shape of the Environment.

- Trend to move toward the exit. During an evacuation, pedestrians may try to reach the exit by moving through the shortest path from their current location. Given a candidate particle at the point , we define its distance to the exit aswhere denotes the Euclidean norm in , and we consider the unitary vector , pointing from to the exit, see Figure 3(a).

- Trend to avoid the collision with walls. A pedestrian at position and moving in direction , that does not point towards the exit, will collide with the wall at a point and a distance from him/her, unless he/she changes direction, see Figure 3(b). Thus, to avoid this collision, the pedestrian must select a suitable new direction. Building on the model presented in [16], we define the unit tangent vector along the boundary at , oriented to guide the particle closer to the exit.

- (A1)

- The trend to the exit increases as particles get closer to it.

- (A2)

- Particles are subject to a stronger influence to avoid the wall as they get closer to it.

- The interaction rate , that models the frequency of interactions between candidate particles and the boundary of the domain. We suppose that decreases with local density, since the lower this quantity is, the easier is for pedestrians to realize about the presence of walls and doors. Following this idea, we assume .

- The transition probability is the probability that an h-candidate particle adjusts its direction into that of the test particle , induced by the presence of walls and exit areas.

2.3.2. Dynamics Induced by Interactions Between Pedestrians

- The interaction rate , that defines the number of binary encounters per unit time. If local density increases, then the interaction rate also increases.

- The transition probability , that represents the probability that a pedestrian with infectious state , level of awareness and moving with direction undergoes a transition into infectious state , level and direction after an interaction with a pedestrian with state , level of awareness and moving with direction .

(I) Interactions can modify the state related to the disease.

(II) Interactions can modify the level of awareness.

- If two pedestrians with the same awareness level interact, then both of them remain at the same level.

- If two pedestrians with different levels of awareness interact, then one pedestrian can influence the other and, as a result, the pedestrian having a lower awareness level may increase her level, while the one with a higher level may face a decrease in her level of awareness.

(III) Interactions can modify the walking direction.

- Tendency to move towards less congested areas. In order to facilitate its movement, a candidate pedestrian at , moving with direction , may decide, under the influence of his/her level of awareness , to change direction by moving towards less congested areas. This direction is denoted by the unitary vector and can be computed by choosing the direction that gives the minimal directional derivative of the density at the point .

- Tendency to follow the stream. A candidate pedestrian, moving with direction and level of awareness , that interact with a field pedestrian may decide to follow him/her and in consequence adopt a new velocity direction. We define the unitary vector to describe the movement of the field particle moving with direction .

- (A3)

- The tendency to look for less congested areas depends on the local density and level of awareness of each active particle.

- (A4)

- The tendency to follow the stream depends on the local density and level of awareness of each active particle.

2.4. Modeling the Velocity Modulus

3. Numerical Results and Cases of Study

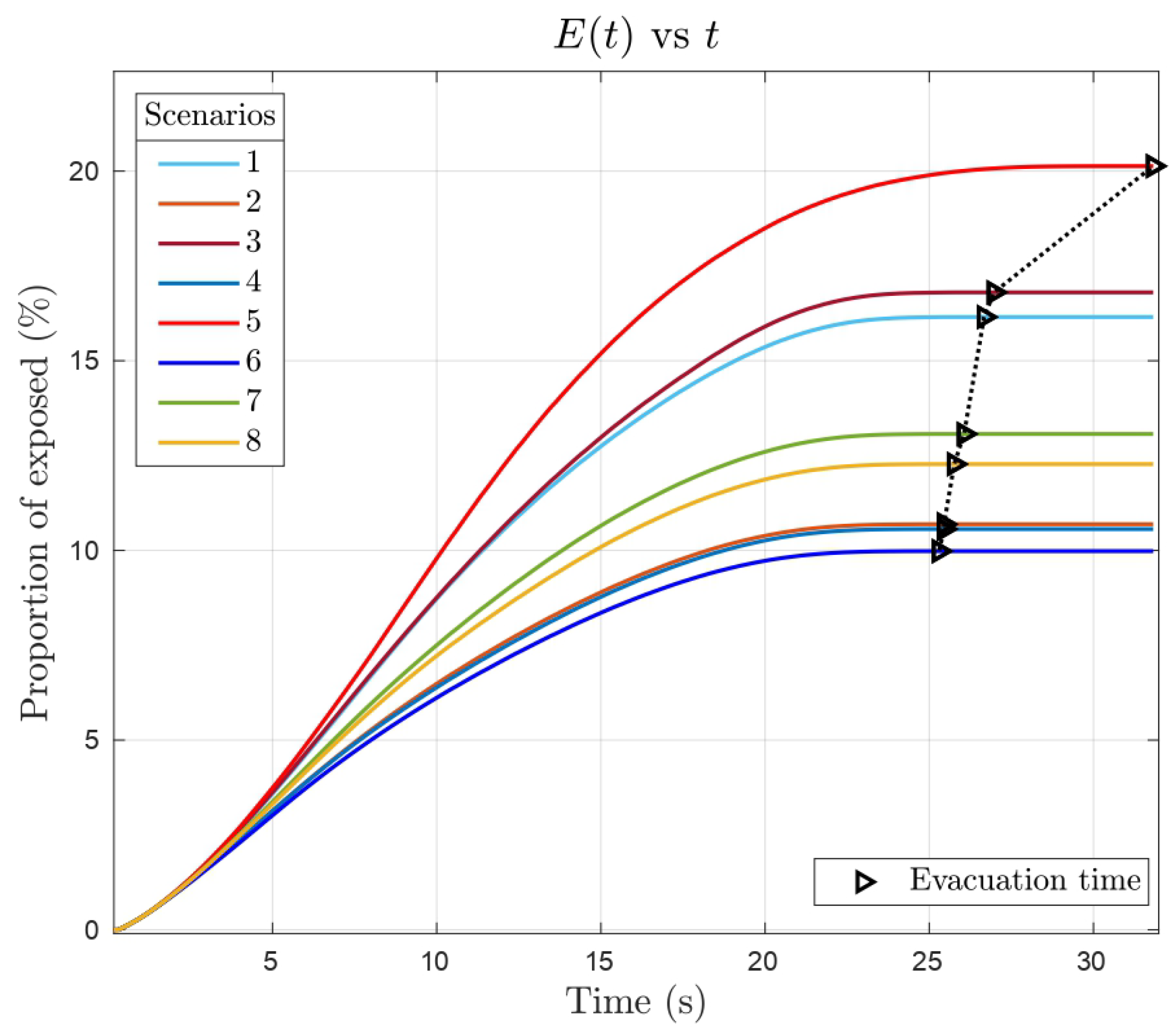

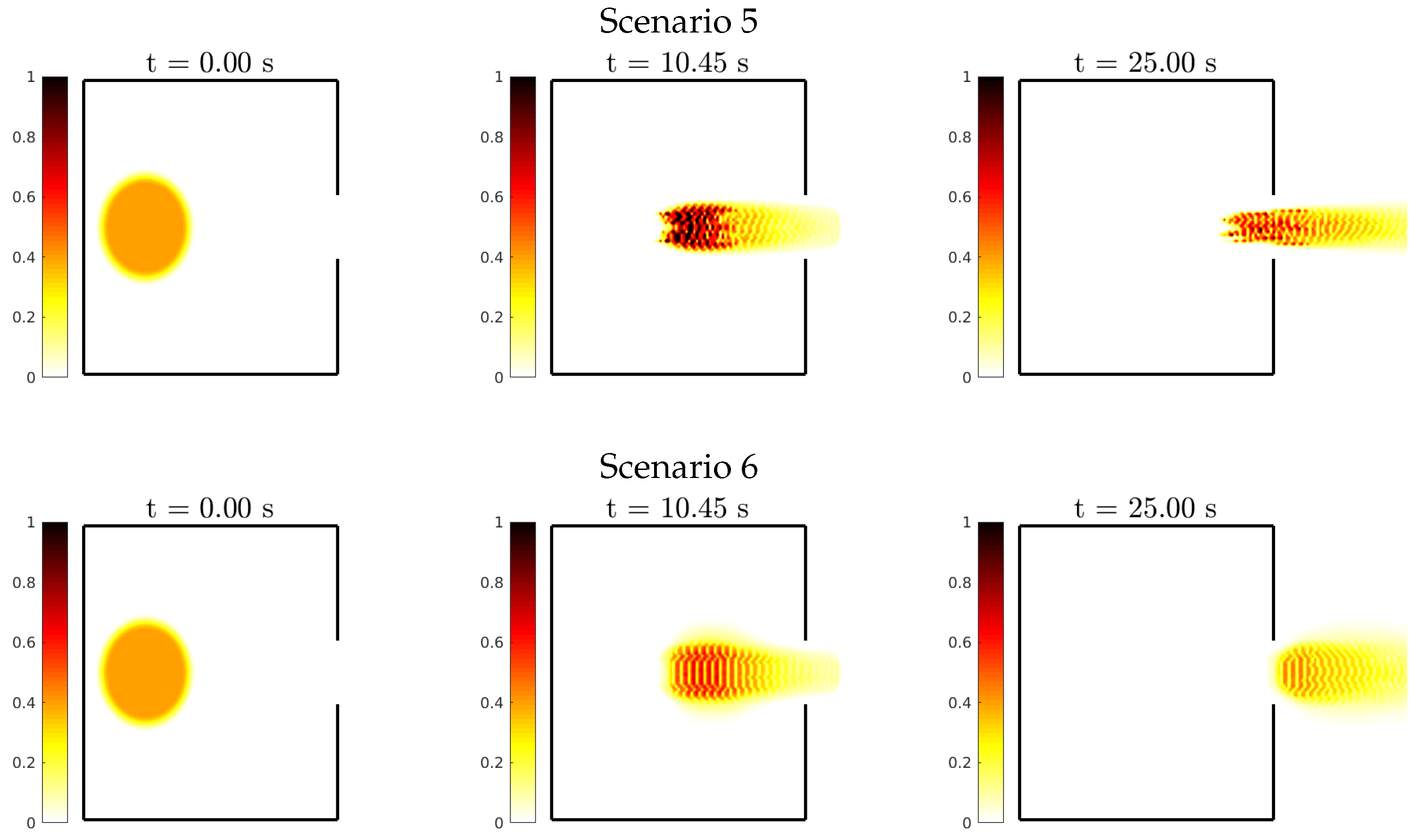

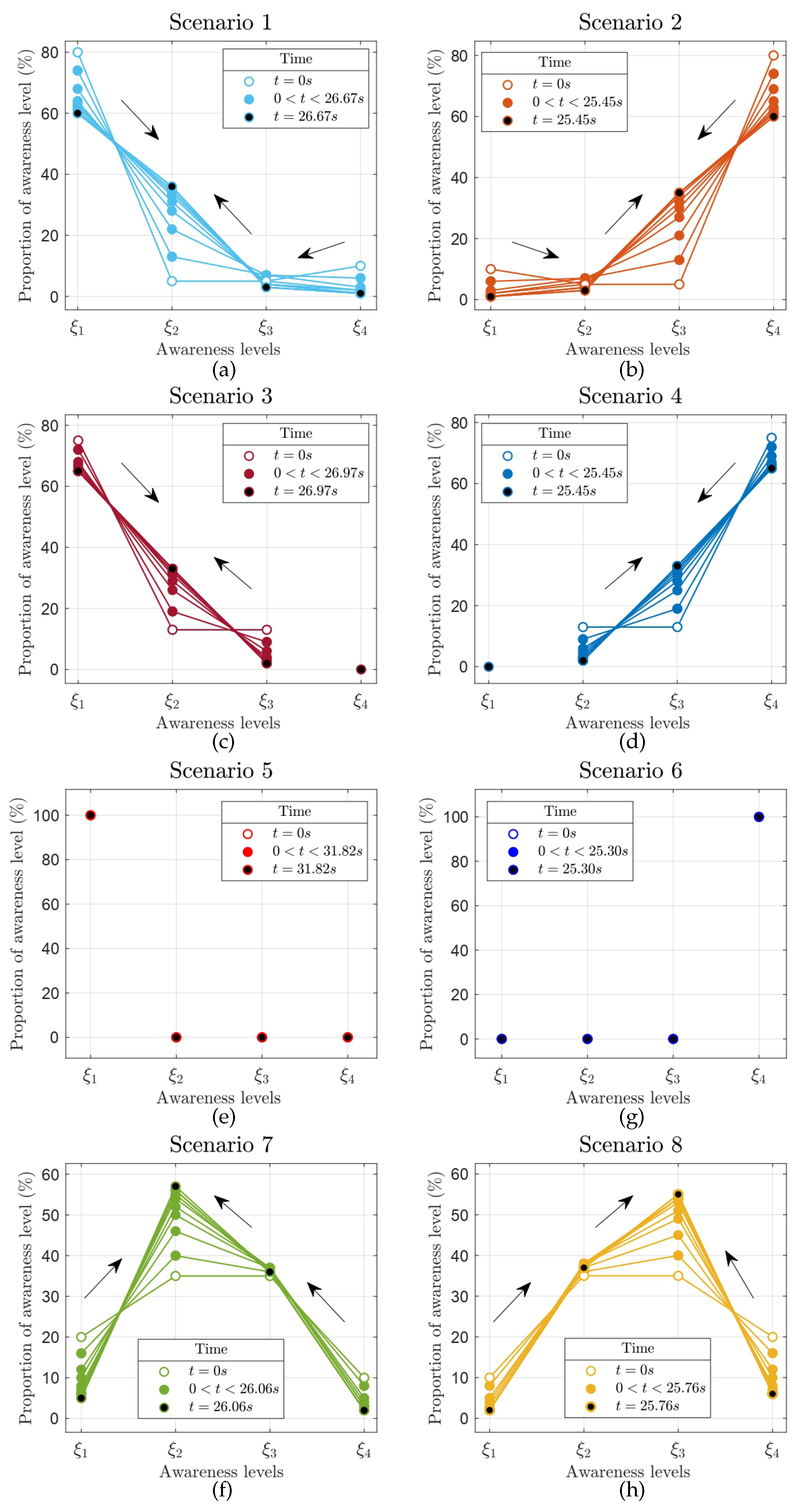

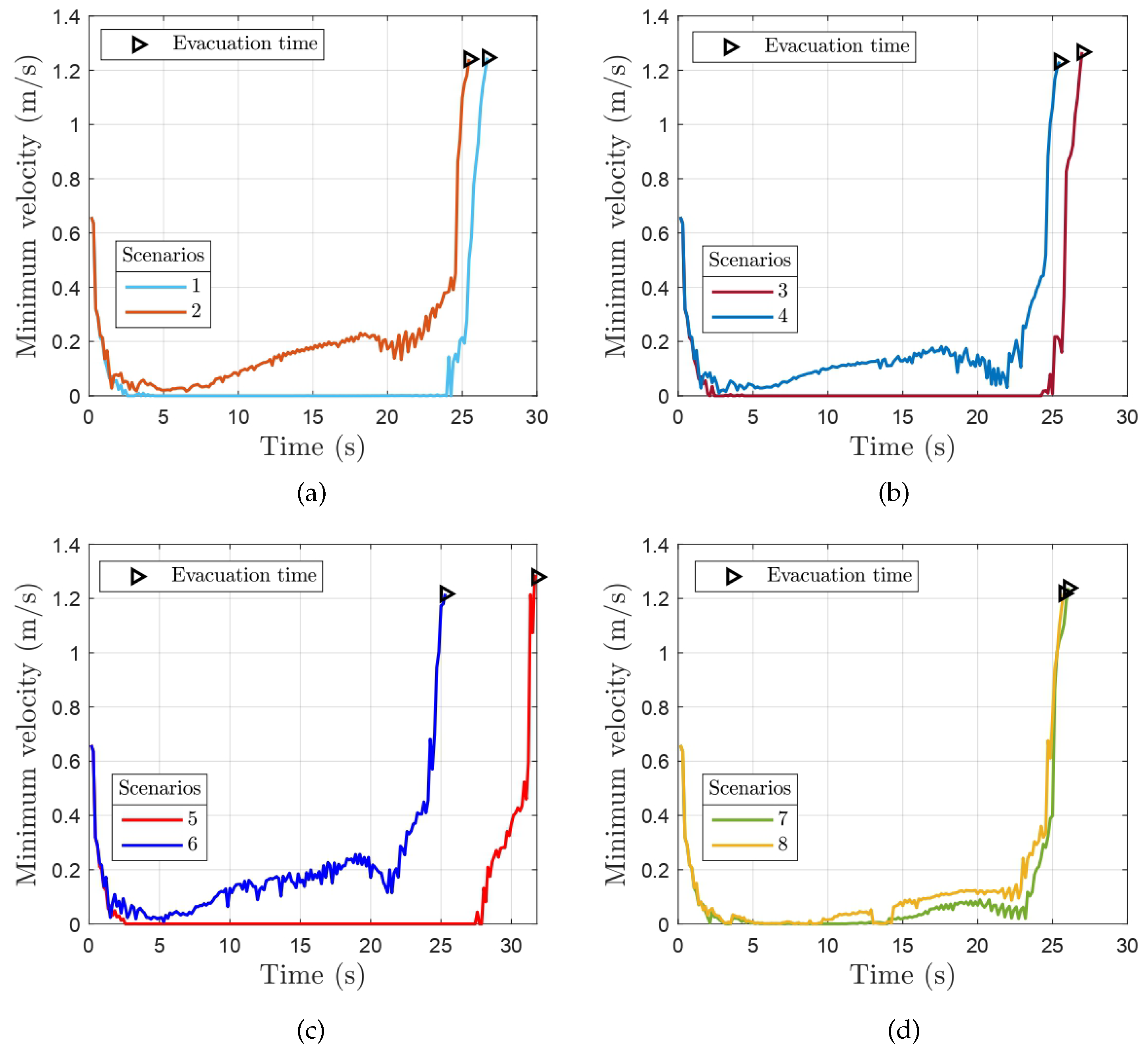

3.1. Case Study 1: The Influence of Awareness Levels

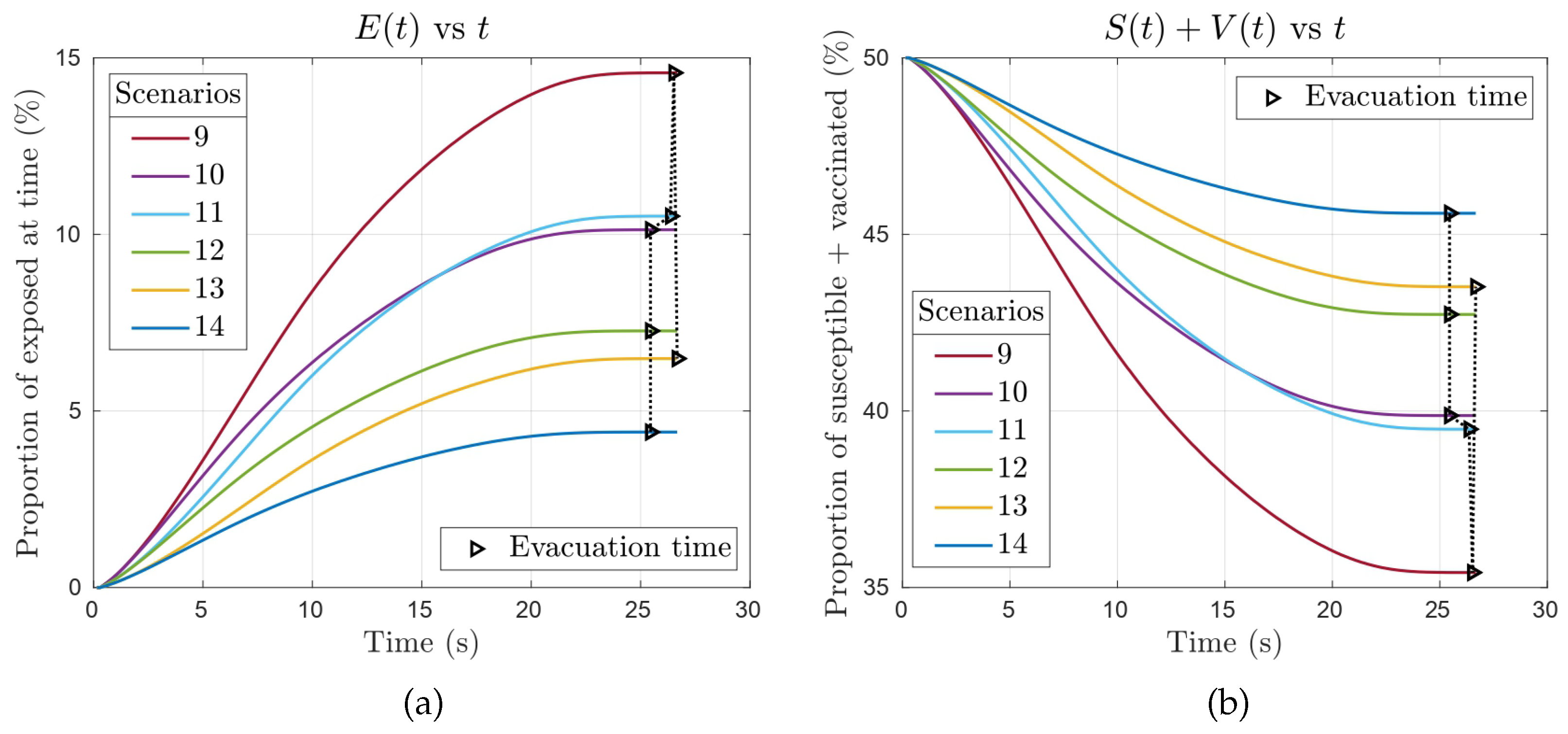

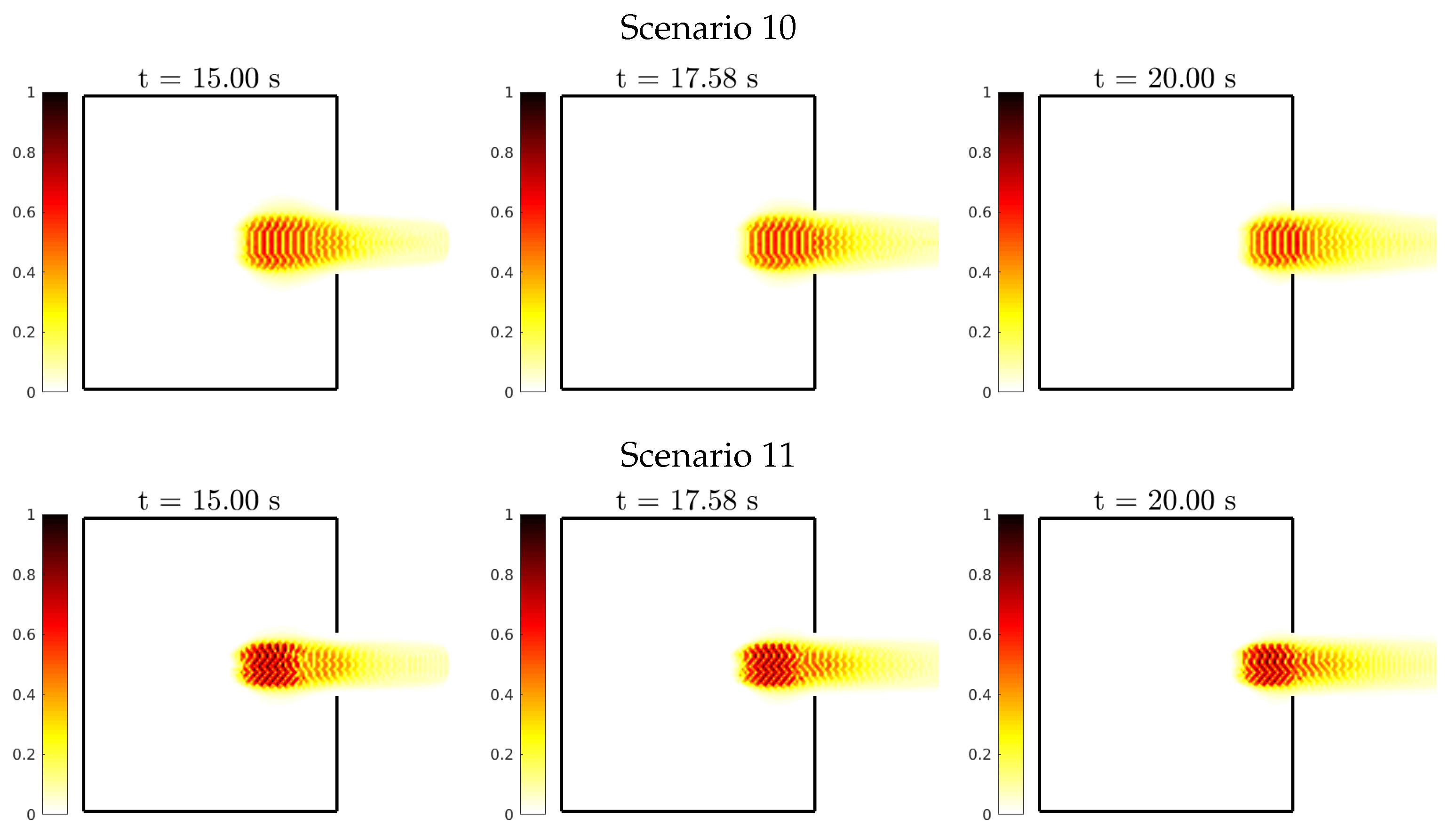

3.2. Case Study 2: Awareness vs. Vaccination

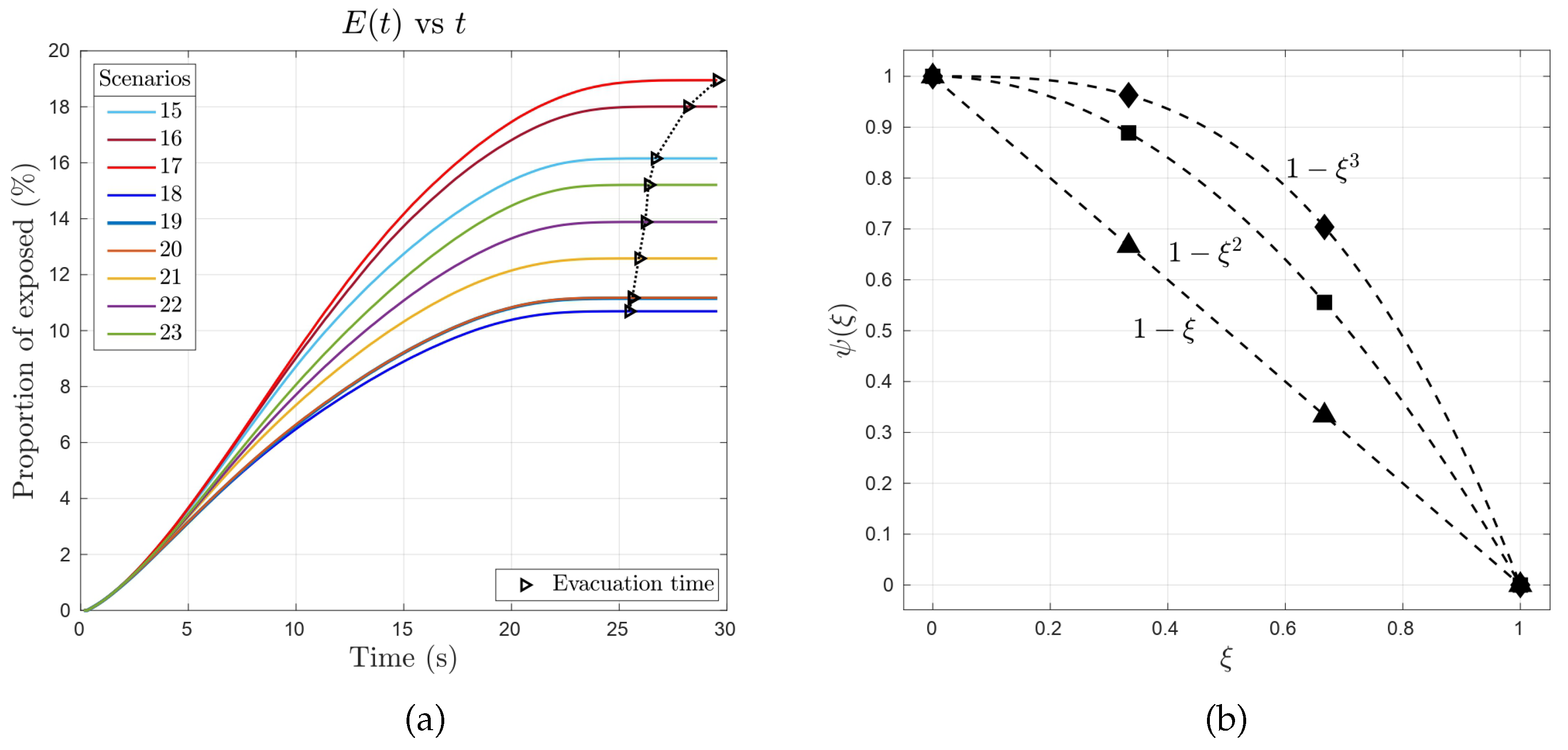

3.3. Case Study 3: Analyzing the Role of

4. Discussion and Conclusions

- Impact of awareness on disease spread: High levels of awareness significantly reduce the spread of disease. Individuals with high awareness adhere to social distancing, exhibit caution for themselves and others, and possess knowledge about safety and prevention measures. Conversely, low levels of awareness lead to greater disease propagation due to neglect of social distancing, indifference, and lack of knowledge.

- Awareness evolution: Pedestrians cannot independently evolve their awareness levels. In our model, the only way to transition to a different awareness state is through interactions with other pedestrians. This aligns with the findings of Kim and Quaini [17], who modeled emotional states (specifically fear) as continuous variables evolving over time. Unlike their model, where fear levels can change even if the entire population starts with the same level, our model shows that a population with uniform awareness levels remains static.

- Impact of awareness on the evacuation dynamics: Unexpectedly, we found that evacuation times were shorter for scenarios with high awareness levels. Initially, we hypothesized that low-awareness pedestrians, focused solely on exiting the room, would achieve faster evacuation by reaching their maximum allowed speed. However, high-awareness pedestrians, by maintaining social distance, actually evacuated more efficiently. This counterintuitive result is explained by the function , which influences evacuation dynamics. Our results are consistent with Agnelli et al. [16], who found that an optimal parameter value of minimized evacuation time. In our study, low-awareness pedestrians had values close to 1, while high-awareness pedestrians had values near 0. There are some practical applications to this counterintuitive result. For instance, during the COVID-19 crisis some airlines have implemented a system to deplane by rows to prevent contagion, resulting also in shorter disembarking times, some interesting models can be found in [26,27,28].

- Action of vaccination: We also obtained interesting insights into the action of vaccination. In a situation in which there is no available immunization to an infectious disease it is evident that awareness must be promoted across the population. However, our results show that the existence of a vaccine can guarantee safety relaxing some policies related to contagion awareness (e.g., social distancing or use of masks).

Funding

References

- Bellomo, N.; Bingham, R.; Chaplain, M.A.; Dosi, G.; Forni, G.; Knopoff, D.A.; Lowengrub, J.; Twarock, R.; Virgillito, M.E. A multiscale model of virus pandemic: Heterogeneous interactive entities in a globally connected world. Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences 2020, 30, 1591–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguiar, M.; Dosi, G.; Knopoff, D.A.; Virgillito, M.E. A multiscale network-based model of contagion dynamics: heterogeneity, spatial distancing and vaccination. Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences 2021, 31, 2425–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnelli, J.P.; Buffa, B.; Knopoff, D.; Torres, G. A spatial kinetic model of crowd evacuation dynamics with infectious disease contagion. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 2023, 85, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellomo, N.; Burini, D.; Dosi, G.; Gibelli, L.; Knopoff, D.; Outada, N.; Terna, P.; Virgillito, M.E. What is life? A perspective of the mathematical kinetic theory of active particles. Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences 2021, 31, 1821–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwell, L.H.; Hopfield, J.J.; Leibler, S.; Murray, A.W. From molecular to modular cell biology. Nature 1999, 402, C47–C52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrero, M.A. On the role of mathematics in biology. Journal of Mathematical Biology 2007, 54, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, R.M. Uses and abuses of mathematics in biology. science 2004, 303, 790–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knopoff, D.A.; Nieto, J.; Urrutia, L. Numerical simulation of a multiscale cell motility model based on the kinetic theory of active particles. Symmetry 2019, 11, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellomo, N.; Outada, N.; Soler, J.; Tao, Y.; Winkler, M. Chemotaxis and cross-diffusion models in complex environments: Models and analytic problems toward a multiscale vision. Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences 2022, 32, 713–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellouquid, A.; Delitala, M. Modelling Complex Biological Systems-A Kinetic Theory Approach. 2006. Birkäuser, Boston.

- Burini, D.; Knopoff, D.A. Epidemics and society—A multiscale vision from the small world to the globally interconnected world. Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences 2024, 34, 1567–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellomo, N.; Burini, D.; Outada, N. Multiscale models of Covid-19 with mutations and variants. Networks & Heterogeneous Media 2022, 17, 293–310. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Quaini, A. Coupling kinetic theory approaches for pedestrian dynamics and disease contagion in a confined environment. Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences 2020, 30, 1893–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burini, D.; Chouhad, N. Cross-diffusion models in complex frameworks from microscopic to macroscopic. Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences 2023, 33, 1909–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.Y.; Tadmor, E. From particle to kinetic and hydrodynamic descriptions of flocking. Kinetic and Related Models 2008, 1, 415–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnelli, J.P.; Colasuonno, F.; Knopoff, D. A kinetic theory approach to the dynamics of crowd evacuation from bounded domains. Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences 2015, 25, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; O’Connell, K.; Ott, W.; Quaini, A. A kinetic theory approach for 2D crowd dynamics with emotional contagion. Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences 2021, 31, 1137–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibelli, L.; Knopoff, D.; Liao, J.; Yan, W. Macroscopic modeling of social crowds. Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences 2024, 34, 1135–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knopoff, D.; Liao, J.; Ma, Q.; Yang, X. Individual-based crowd dynamics with social interaction. Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Quaini, A. A kinetic theory approach to model pedestrian dynamics in bounded domains with obstacles. Kinetic & Related Models 2019, 12, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, H.; Karlsen, K.H.; Lie, K.A. Splitting methods for partial differential equations with rough solutions: Analysis and MATLAB programs; European Mathematical Society: EMS Publishing House Zürich, 2010.

- LeVeque, R.J. Finite Volume Methods for Hyperbolic Problems (Cambridge Texts in Applied Mathematics); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Piccoli, B.; Tosin, A. Time-evolving measures and macroscopic modeling of pedestrian flow. Archive for Rational Mechanics and Analysis 2011, 199, 707–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, M. Computational engineering: Introduction to numerical methods; Springer: Berlin, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Buchmueller, S.; Weidmann, U. Parameters of pedestrians, pedestrian traffic and walking facilities. IVT-Report Nr. 132, Institut for Transport Planning and Systems (IVT), Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETHZ) 2006.

- Schultz, M.; Fuchte, J. Evaluation of aircraft boarding scenarios considering reduced transmissions risks. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, M.; Soolaki, M.; Bakhshian, E.; Salary, M.; Fuchte, J. COVID-19: passenger boarding and disembarkation. Fourteenth USA/Europe Air Traffic Management Research and Development Seminar (ATM2021), 2021.

- Xie, C.Z.; Tang, T.Q.; Hu, P.C.; Huang, H.J. A civil aircraft passenger deplaning model considering patients with severe acute airborne disease. Journal of Transportation Safety & Security 2022, 14, 1063–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scenarios | Initial proportion of individuals (%) and function | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 80 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 80 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 75 | 0 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 4 | 0 | 75 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 5 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7 | 20 | 35 | 35 | 10 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8 | 10 | 35 | 35 | 20 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |

| Scenarios | Initial proportion of individuals (%) and function | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 50 | 0 | 80 | 5 | 5 | 10 | |||

| 10 | 50 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 80 | |||

| 11 | 25 | 50 | 0 | 25 | 80 | 5 | 5 | 10 | |

| 12 | 25 | 50 | 0 | 25 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 80 | |

| 13 | 50 | 0 | 80 | 5 | 5 | 10 | |||

| 14 | 50 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 80 | |||

| Scenarios | Initial proportion of individuals (%) and function | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 80 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 16 | 80 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 17 | 80 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 18 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 80 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 19 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 80 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 20 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 80 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 21 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 22 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 23 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).