Introduction

There is a general consensus that anatomical reduction and stabilization of the distal tibiofibular joint (DTFJ) is necessary. Incongruity after stabilization is associated with increased pressure on the talus and a poorer outcome, which may result in long-term complications [

1,

2]. It has been demonstraed that malreduction, particularly in the sagittal plane, occurs in up to 40% of cases [

3,

4]. Therefore, it is crucial to identify and address all risk factors for malreduction before and during surgical treatment.

The anatomical configuration of the DTFJ exhibits large inter-individual, gender and age variability [

5,

6,

7]. It is therefore recommended that bilateral computed tomography (CT) be performed to ensure adequate intra- or post-operative control following surgical stabilization [

3,

6]. Despite more recent examinations of the DTFG using three-dimensional, sometimes automated procedures, CT diagnostic and control remains the general standard. In most studies, the analysis is performed 10 mm above the joint line [

8]. Moreover, certain anatomical configurations have been demonstrated to increase the risk of malreduction following syndesmotic screw (SYS) stabilization [

9]. A syndesmosis with a deep tibial incisura (incisura) and a fibula that does not engage the tibial incisura is at an increased risk of overtightening. An anteverted incisura poses a risk of anterior fibular translation, while a retroverted incisura poses a risk of posterior fibular translation [

10,

11]. The need for preoperative bilateral CT to improve individualised therapy is therefore being discussed, but remains controversial [

12]. In addition to the syndesmosis screw, stabilisation with a suture button system (SBS) has become established [

3,

13,

14]. In contrast to SYS, which offers static stabilisation, SBS stabilisation has been proven to possess a dynamic component that can be described as a “flexible nature of fixation” (FNF) [

4,

12,

15,

16,

17]. This flexible property may contribute to a reduction in the rate of sagittal malreduction [

4,

17]. It is currently unclear whether the observed effect of FNF is influenced by the anatomy of the incisura. The objective of this study was to assess the impact of the incisura anatomy on the dynamic stabilisation of the DTFJ, with particular focus on its ‘flexible nature of fixation’. It was hypothesised that stabilisation via suture button systems can be performed regardless of anatomical variations.

Materials and Methods

The local institutional review board gave approval for the study beforehand (AZ 488/19-ek).

This retrospective study included 44 consecutive adult patients who underwent surgical stabilisation of the DTFJ in the course of ankle fractures by suture button system and met the inclusion criteria (

Table 1, Flowchart). The identified patients were stored in an electronic database using SPSS (version 24, Chicago, IL, USA), with their data pseudonymised. The patients were, on average, 39 years old (range 18 to 68 years; SD 14 years). There was no difference between sexes (female N = 21 mean age 41 years, SD 15 years; male N = 23 mean age 39 years, SD 14 years; *p = 0.686).

All fractures were classified and treated in accordance with the “Arbeitsgruppe für Osteosynthesefragen” (AO) classification at a trauma level I center [

18,

19]. In patients with no evidence of instability of the distal tibiofibular joint (DTFJ) on preoperative imaging and fracture pattern, an intraoperative assessment of instability was conducted after stabilising the fracture. This was done using standard fluoroscopy (lateral and mortise view) with the hook test, while the joint was held in a neutral, dorsally flexed position [

18,

20,

21]. Once the instability had been verified, reduction and preliminary K-wire fixation of the syndesmosis was carried out under visualisation via the chosen approach. Following verification of the reduction using fluoroscopy, final stabilisation was performed with a suture-button device (TightRope

®, Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA) [

22].

All bilateral CT scans were obtained during the in-patient period without the administration of intravenous contrast medium as part of the standard care to assess syndesmotic reduction. Patients were positioned supine and feet first with the ankle in a neutral position. Images were acquired using a multidetector CT scanner (iCT 256, Philips, Netherlands) and were reconstructed in slice thickness of 0.67 mm to 1 mm in axial, sagittal and coronal orientation.

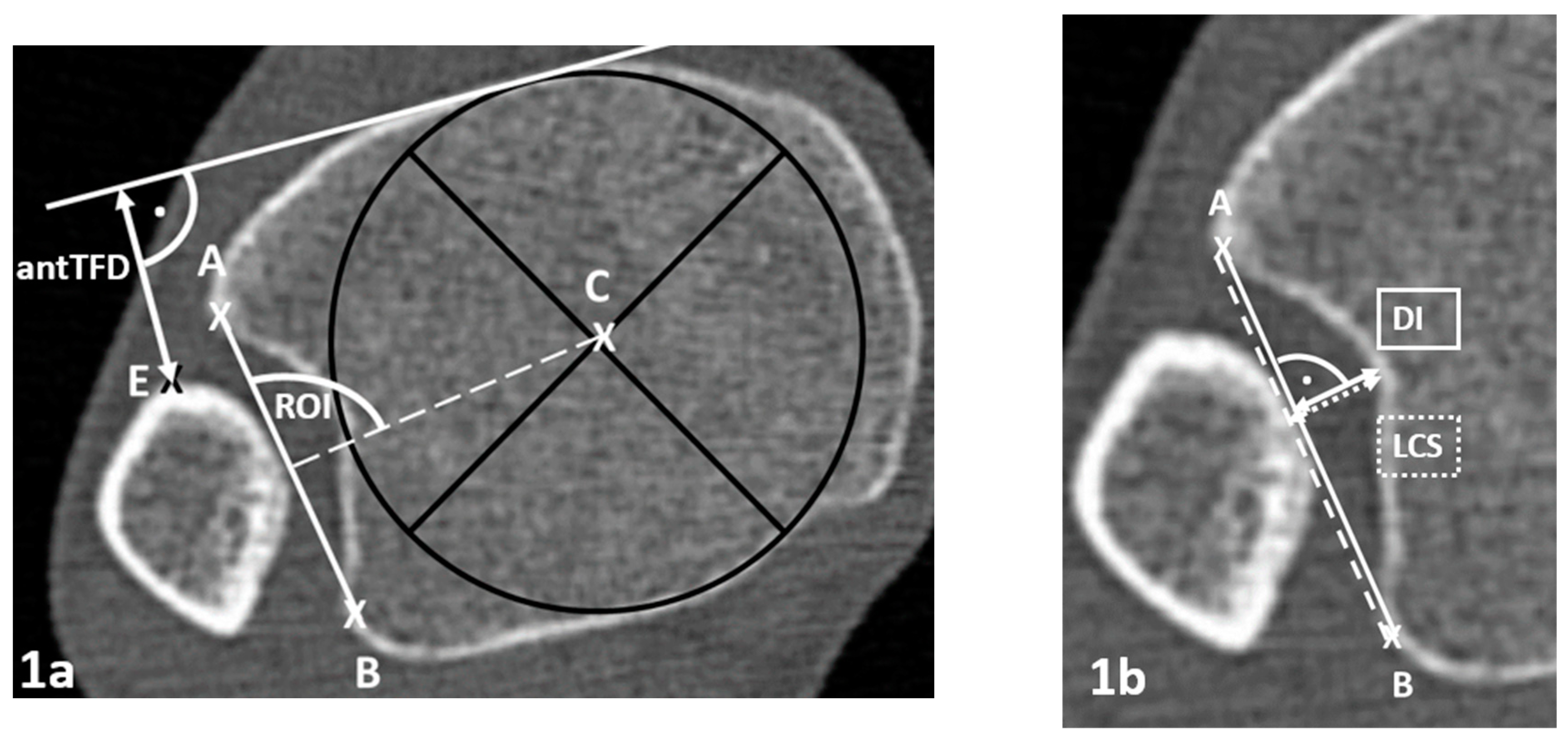

The following parameters were selected to describe the anatomy of the tibial incisura. These included the depth of the incisura (DI), the fibula engagement (FE), the Leporjärvi clear space (LCS), the Nault talar dome angle (NTDA), the anterior tibio-fibular distance (antTFD), and the rotation of the incisura (ROI) of the native side. These were measured 10 mm proximal to the plafond as previously described (

Figure 1) [

5,

9,

23]. All parameters have been proven to have high reliability [

9,

23]. Positive values of FE represent tibio-fibular overlap and ROI greater than 90° a dorsally opened incisura plane (

Figure 1a,b). To verify the comparability of the two sides, the DI of the native and stabilized side were compared.

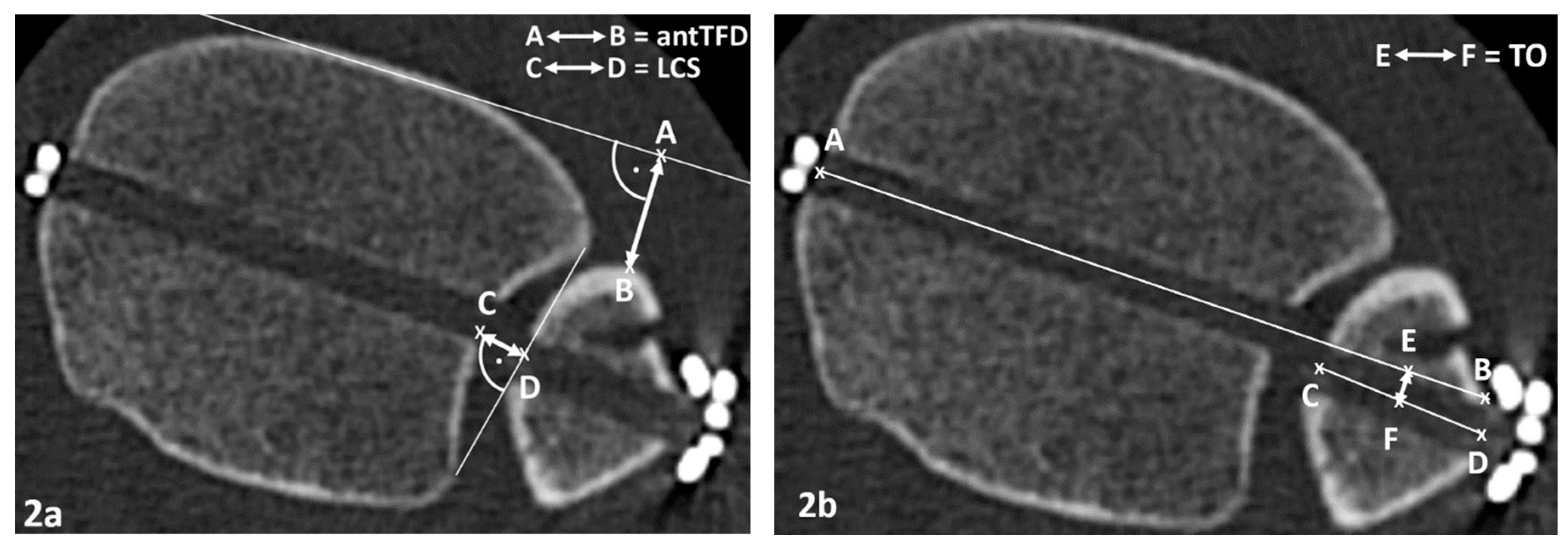

The syndesmotic reduction was also assessed 10 mm proximal of the tibial plafond using the LCS to analyse the medial-lateral translation (coronal plane), the NTDA to evaluate the rotation (transversal plane) and the antTFD for protrusion (sagittal plane,

Figure 2a) [

9,

24,

25,

26]. The parameters were assessed for both sides and the side-to-side difference (Δ) between the injured and uninjured side was calculated (ΔLCS, ΔNTDA and ΔantTFD). A positive ΔLCS indicates widening of the syndesmosis, a positive ΔantTFD defines a posterior translation of the fibula at the stabilised DTFJ, and a positive ΔNTDA represents an increased external rotation of the fibula at the stabilised DTFJ. In accordance with existing literature, malreduction of the syndesmosis is defined as a side-to-side difference of more than two millimeters In order to facilitate comparison with results from the literature, the thresholds in this analysis were determined to be greater than 1.0 mm for ΔLCS, ΔaTFD, and greater than 5° for ΔNTDA, as a definition of incongruity [

1,

27]. To quantify the FNF, the transverse offset (TO) of the burr channels was measured In accordance with the previously described methodology (sagittal plane,

Figure 2a) [

17].

The standardised measurements of the parameters describing the anatomy were performed using the RadiAnt DICOM Viewer 2020.2.3 (Medixant, Poznań, Poland). The radiological measurements assessing the reduction result and the FNF were performed by two examiners. Previous studies have demonstrated an excellent level of intra- and inter-observer reliability for all parameters used [

11,

17,

23].

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed with SPSS software (version 25, Chicago, IL, USA). The Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney U-test or Kruskal-Wallis-Test were used to compare continuous variables between the study groups, depending on normal distribution and study size (Shapiro-Wilk test). Categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. P-values (p) of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Spearman-Rho correlation coefficients (rho) were used for correlation analysis. The interpretation of |r

s| was as follows: poor (rs < 0.3), moderate (0.3 > rs < 0.5), good (rs > 0.50) [

27].

Results

Parameters Describing the Anatomy of the DTFJ

The mean depth of incisura (DI) on the native side was 3.9 mm (SD 1.2 mm), while on the injured side it was 3.8 mm (SD 1.3 mm). There was no significant difference between the two sides (p = 0.993). The mean engagement of the fibula on the native side into the incisura was 0.4 mm (SD 1.4 mm), while the Leporjärvi clear space (LCS) was 3.5 mm (SD 1.1 mm) and external rotation (NTDA) was 8 degrees (SD 5 degrees). The mean rotation of the incisura (ROI) on the native side was 96 degrees (SD 4 degrees), indicating that the sagittal incisura plane was on average 6 degrees (SD 4°) directed dorsally. Men have lager DI than women [4.3mm (SD 1.1mm) vs 3.3mm (SD 1.2), p = 0.003]. LCS showed no sex differences [men 3.6mm (SD 1.1mm); women 3.4mm (SD 1.2mm), p = 0.378].

For the parameters DI, LCS, FE and antTFD, there are inter-individual differences in excess of 4 mm. The complete results are listed in

Table 2.

There was a positive correlation between depth of incisura (DI) and fibular engagement (FE), indicating that as the depth of the incisura increased, the fibular engaged deeper in the incisura (FE) (rs = 0.663). With increasing fibula engagement, there tends to be a smaller cleare space (rs = -0,446). No correlation was seen between ROI to NTDA, to FE or LCS (|rs | < 0.300).

Correlation Between Reduction Outcome Parameters and Incisura Parameters

On average, a slight diastasis (ΔLCS/ΔFE) of 0.6 mm/0.7 mm (SD 1.6 mm/0.9 mm), a slight dorsal translation (ΔantTFD) of 0.4 mm (SD 2.4 mm) and an external rotation (ΔNTDA) of 2 degrees (SD 4 degrees) tended to occur on the operative side without differences between the sexes (p > 0.05). Full results are shown in

Table 4.

Patients with slight over-tightening exhibited a smaller FE compared to patients with symmetrical reduction (p < 0.05) and to patients with slight diastasis (p = 0.047,

Table 4). There was no difference between patients with slight diastasis and patients with symmetrical congruity (p = 0.336). No differences in DI, ROI, LCS or NTDA were observed between patients with post-operative slight diastasis (ΔLCS > 1 mm) or over-tightened (ΔLCS > -1 mm; p > 0.05,

Table 4).

There is a moderate positive correlation between FE and ΔLCS (rs = 0.406). This indicates that the deeper the fibula is anchored in the incisura, the less this anchoring was restored. Conversely, a wide LCS on the native side is associated with increasing overstressing at a moderate correlation level (rs = -0.495;

Table 4). There were no correlations observed between other parameters describing the anatomy (DI, ROI, NTDA) and the outcome parameters of reduction (

Table 4).

The Impact of Incisura Anatomy on the “Flexible Nature of Fixation”

The mean TO was 1.2 mm (SD, 1.4 mm), with no differences between sexes (p > 0.005;

Table 2). There were no differences observed between patients with TO greater or less than 1 mm (p > 0.005;

Table 3). Additionally, no correlation was found between the extent of FNF and the parameters describing the anatomy of DTFJ (rs < 0.300;

Table 5).

Discussion

This analysis also corroborates the observation that there are considerable inter-individual differences in the appearance of the uninjured tibio-fibular joint (DTFJ) [

5,

6,

26,

28]. A larger depth of incisura (DI) was found to be associated with a larger fibula engagement (FE). In the frontal plane, individuals who had undergone slight over-tightening showed a smaller FE on the native side. There was no evidence to suggest that individual incisura anatomy affects the reduction outcome or the extent of “flexible nature of fixation” (FNF) after dynamic stabilisation, as demonstrated by post-operative CT control.

In the diagnosis of syndesmotic lesions, CT is the superior imaging modality to plain radiography for subtle diastasis of >3 mm, as well as for the assessment of sagittal alignment of the DTFJ, which represents the majority of malreduction [

29]. Despite the increasing availability of three-dimensional analyses with partially automated evaluation, studies with two-dimensional CT remain relevant for clinical practice [

7,

30,

31]. CT is widely available and remains the gold standard in clinical practice. It has also been shown to be highly correlated with three-dimensional parameters [

32]. The present analysis of bilateral CT scans confirms that there are only minimal intraindividual variations in the anatomy of the DTFJ. It is important to note that there are substantial variations between individuals in LCS measurements [

6,

7,

25]. These range from 4 mm to 8 mm for ATF, 5 mm to 6 mm for TFO, 6 mm to 13 mm for TFCS, and 13 mm for antTFD [

5,

7]. The findings of this study reinforce the recommendation that a unilateral CT scan is not a comprehensive assessment of the DTFJ. It is not suitable for identifying DTFJ instability or for assessing DTFJs following surgical stabilisation. A comprehensive bilateral comparison is required [

32,

33]. In particular, the presence of a discrepancy between the anterior tibiofibular compression (ATF) and the tibiofibular compression stress (TFCS) of more than 2 mm in lateral comparison suggests that there may be a malposition present, which could potentially have a negative effect on the clinical outcome [

1].

We are not aware of any studies that have investigated the impact of the anatomy of the incisura, respectively the DTFJ, on the reduction outcome in dynamic stabilisation. In contrast, there are studies available that have investigated the impact of static stabilisation of the DTFJ[

10,

34]. The present study does not assess the categorical quality of DTFJ reduction. Instead, the relationship between the anatomical properties and congruity of DTFJ after dynamic stabilisation by SBS was analysed in order to facilitate comparison with the existing literature [

34].

The present study did not confirm the findings of Boszcyk et al., which suggested that a deep incisura is more frequently associated with over-compression and a shallow incisura with anterior incongruence [

35]. The relationship between the depth of the tibial incisura and the postoperative rotation of the fibula remains a topic of debate. Cherney et al. observed a greater frequency of external rotation of the fibula with increasing depth [

10,

36]. Conversely, our findings align with those of Bosczyk, who was unable to demonstrate this relationship [

10,

35]. In comparison to the syndesmotic screw, during suture button stabilisation, an anterior rotation of the incisura was not confirmed as a morphologic risk factor for anterior in-congruity [

10,

35]. Furthermore, a retroversion of the incisura was not associated with a posterior in-congruity while flexible stabilization [

35]. In the authors’ opinion, the so-called “flexible nature of fixation” (FNF) may be a potential explanation for the lack of correlation between anatomy and reduction outcome. FNF describes small amplitude movements of the fibula that still allow self-centering within the incisura after stabilization (

Figure 2b) [

4,

16,

17]. Previous CT analyses have demonstrated that sagittal translation of the fibula towards the lowest point of the incisura occurs with greater frequency after SBS than after SYS [

17]. The flexible nature of the suture button’s fixation has been demonstrated in CT analysis to result in a low malreduction rate [

4,

17]. In SYS stabilization there is no compensation by sagittal translation, therefore it can be called a static stabilization [

17,

37].

Considering the presented results, the authors hypothesise that the extent of FNF is able to compensate for minor anatomical discrepancies that may occur during reduction due to the anatomical configuration. This results in a lack of correlation between the rate of incongruity and the anatomy of the DTFJ.

As a result, the question was raised as to the extent to which anatomy influences the extent of translation. In the present analysis, no correlation was found between the extent of FNF during SBS stabilisation (transverse offset; TO) and the parameters describing the anatomy of the DTFJ. It is therefore this author’s opinion that stabilisation of the DTFJ can be performed regardless of the anatomical configuration.

It should be noted that this study is not without limitations. In addition to the retrospective design and the heterogeneous patient group, the determination of the reduction was independent of the size of the patient 10 mm above the plafond. In order to facilitate a comparison of the results with those obtained following static stabilisation, the study design was modified to align with the methodology described by Boszcyk et al. [

34]. The results of the study are also based on the assumption that the extremities are symmetrical, which is well documented by studies [

7]. In order to account for inter-individual variability, further analyses could be conducted on the initial axial CT slice in which first subchondral bone is visible [

38]. Furthermore, the available studies employ disparate methodologies, necessitating the establishment of a consensus on the parameters to be considered. This is in accordance with the recommendations of Schon et al. [

24] One possible approach is to determine these parameters in the first slice of the CT, where the subchondral bone of the tibia is visible. This is a topic for further investigation.

The parameters describing the anatomy were measured by one examiner (R.H.). Prior to this, a high level of reliability was demonstrated for the parameters used [

17,

34]. Two investigators (H.R. and C.F.) performed the radiological measurements of the reduction result and the FNF. High intra- and interrater reliability has also been demonstrated in previous publications [

17].

Conclusion

The considerable inter-individual anatomical variability of the DTFJ was confirmed. The morphological configuration of the incisura has no impact on the immediate reduction result after dynamic stabilisation of the DTFG, as determined by CT. The extent of FNF is also not affected by the morphology of the incisura. Stabilisation of the DTFJ can be performed regardless of the anatomical configuration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: RH, CF and ABA; Methodology: RH, CF and ABA Software: RH and ABA; Validation/Formal Analysis/Data Curation RH, CF and FS; Writing – Original Draft Preparation RH and ABA; Writing – Review & Editing FS and UJS; Supervision CK.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approval of the local institutional review board for study had been given (Ethical Committee at the Medical Faculty, Leipzig University, AZ 488/19-ek) in view of the retrospective nature of the study and all the procedures being performed were part of the routine care.

Informed Consent Statement

All individuals have given general consent in the use of their data, including imaging, for analysis and publication. This has been approved by the Ethical Committee.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients who participated in the study and the Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology at Leipzig University Hospital for providing the imaging.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Andersen M. R., Diep L. M., Frihagen F., Castberg Hellund J., Madsen J. E., & Figved W. (2019). Importance of Syndesmotic Reduction on Clinical Outcome After Syndesmosis Injuries: Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 33(8), 397-403. [CrossRef]

- Sagi H. C., Shah A. R., & Sanders R. W. (2012). The Functional Consequence of Syndesmotic Joint Malreduction at a Minimum 2-Year Follow-Up: Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 26(7), 439-443. [CrossRef]

- Hennings R., Souleiman F., Heilemann M., Hennings M., Klengel A., Osterhoff G., et al. (2021). Suture button versus syndesmotic screw in ankle fractures - evaluation with 3D imaging-based measurements. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 22(1), 970. [CrossRef]

- Spindler F. T., Gaube F. P., Böcker W., Polzer H., & Baumbach S. F. (2022). Compensation of Dynamic Fixation Systems in the Quality of Reduction of Distal Tibiofibular Joint in Acute Syndesmotic Complex Injuries: A CT-Based Analysis. Foot & Ankle International, 107110072211151. [CrossRef]

- Dikos G. D., Heisler J., Choplin R. H., & Weber T. G. (2012). Normal Tibiofibular Relationships at the Syndesmosis on Axial CT Imaging: Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 26(7), 433-438. [CrossRef]

- Park C. H., & Kim G. B. (2019). Tibiofibular relationships of the normal syndesmosis differ by age on axial computed tomography—Anterior fibular translation with age. Injury, 50(6), 1256-1260. [CrossRef]

- Souleiman F., Heilemann M., Hennings R., Hennings M., Klengel A., Hepp P., et al. (2021). A standardized approach for exact CT-based three-dimensional position analysis in the distal tibiofibular joint. BMC Medical Imaging, 21(1), 41. [CrossRef]

- Rammelt S., & Boszczyk A. (2018). Computed Tomography in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Ankle Fractures: A Critical Analysis Review. JBJS Reviews, 6(12), e7-e7. [CrossRef]

- Boszczyk, A., Kwapisz S., Krümmel M., Grass R., & Rammelt S. (2018). Correlation of Incisura Anatomy With Syndesmotic Malreduction. Foot & Ankle International, 39(3), 369-375. [CrossRef]

- Cherney S.M., Spraggs-Hughes A. G., McAndrew C. M., Ricci W. M., & Gardner M. J. (2016). Incisura Morphology as a Risk Factor for Syndesmotic Malreduction. Foot & Ankle International, 37(7), 748-754. [CrossRef]

- Boszczyk, A., & Rammelt S. (2018). Syndesmotic Anatomy as a Risk Factor for Syndesmotic Injury and Syndesmotic Malreduction. Foot & Ankle Orthopaedics, 3(3), 2473011418S0016. [CrossRef]

- Kortekangas T., Savola O., Flinkkilä T., Lepojärvi S., Nortunen S., Ohtonen P., et al. (2015). A prospective randomised study comparing TightRope and syndesmotic screw fixation for accuracy and maintenance of syndesmotic reduction assessed with bilateral computed tomography. Injury, 46(6), 1119-1126. [CrossRef]

- Laflamme M., Belzile E. L., Bédard L., van den Bekerom M. P. J., Glazebrook M., & Pelet S. (2015). A Prospective Randomized Multicenter Trial Comparing Clinical Outcomes of Patients Treated Surgically With a Static or Dynamic Implant for Acute Ankle Syndesmosis Rupture. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 29(5), 216-223. [CrossRef]

- Naqvi G.A., Cunningham P., Lynch B., Galvin R., & Awan N. (2012). Fixation of Ankle Syndesmotic Injuries: Comparison of TightRope Fixation and Syndesmotic Screw Fixation for Accuracy of Syndesmotic Reduction. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 40(12), 2828-2835. [CrossRef]

- Westermann R.W., Rungprai C., Goetz J. E., Femino J., Amendola A., & Phisitkul P. (2014). The Effect of Suture-Button Fixation on Simulated Syndesmotic Malreduction: A Cadaveric Study. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 96(20), 1732-1738. [CrossRef]

- Kimura, S., Yamaguchi S., Ono Y., Watanabe S., Akagi R., Sasho T., et al. (2021). Changes in the Syndesmotic Reduction After Syndesmotic Suture-Button Fixation for Ankle Malleolar Fractures: 1-Year Longitudinal Evaluations Using Computed Tomography. Foot & Ankle International, 107110072110085. [CrossRef]

- Hennings, R., Fuchs C., Spiegl U. J., Theopold J., Souleiman F., Kleber C., et al. (2022). “Flexible nature of fixation” in syndesmotic stabilization of the inferior tibiofibular joint affects the radiological reduction outcome. International Orthopaedics. [CrossRef]

- Buckley R.E., Moran C. G., & Apivatthakakul T. (2017). AO Principles of Fracture Management Volume 1, Volume 1.

- Meinberg, E., Agel J., Roberts C., Karam M., & Kellam J. (2018). Fracture and Dislocation Classification Compendium—2018: Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 32, S1-S10. [CrossRef]

- Pakarinen, H., Flinkkilä T., Ohtonen P., Hyvönen P., Lakovaara M., Leppilahti J., et al. (2011). Intraoperative Assessment of the Stability of the Distal Tibiofibular Joint in Supination-External Rotation Injuries of the Ankle: Sensitivity, Specificity, and Reliability of Two Clinical Tests. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 93(22), 2057-2061. [CrossRef]

- Rüedi T.P., & Murphy W. M. (2000). AO Principles of Fracture Management. Stuttgart ; New York : Davos Platz, [Switzerland]: Thieme ; AO Pub.

- Cottom J.M., Hyer C. F., Philbin T. M., & Berlet G. C. (2008). Treatment of Syndesmotic Disruptions with the Arthrex TightropeTM: A Report of 25 Cases. Foot & Ankle International, 29(8), 773-780. [CrossRef]

- Ahrberg A.B., Hennings R., Von Dercks N., Hepp P., Josten C., & Spiegl U. J. (2020). Validation of a new method for evaluation of syndesmotic injuries of the ankle. International Orthopaedics, 44(10), 2095-2100. [CrossRef]

- Schon J.M., Brady A. W., Krob J. J., Lockard C. A., Marchetti D. C., Dornan G. J., et al. (2019). Defining the three most responsive and specific CT measurements of ankle syndesmotic malreduction. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 27(9), 2863-2876. [CrossRef]

- Lepojärvi, S., Pakarinen H., Savola O., Haapea M., Sequeiros R. B., & Niinimäki J. (2014). Posterior Translation of the Fibula May Indicate Malreduction: CT Study of Normal Variation in Uninjured Ankles. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 28(4), 205-209. [CrossRef]

- Nault, M.-L., Hébert-Davies J., Laflamme G.-Y., & Leduc S. (2013). CT Scan Assessment of the Syndesmosis: A New Reproducible Method. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 27(11), 638-641. [CrossRef]

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. . Hillsdale, N.J: L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Elgafy H., Semaan H. B., Blessinger B., Wassef A., & Ebraheim N. A. (2010). Computed tomography of normal distal tibiofibular syndesmosis. Skeletal Radiology, 39(6), 559-564. [CrossRef]

- Gardner M.J., Demetrakopoulos D., Briggs S. M., Helfet D. L., & Lorich D. G. (2006). Malreduction of the Tibiofibular Syndesmosis in Ankle Fractures. Foot & Ankle International, 27(10), 788-792. [CrossRef]

- Peiffer, M., Van Den Borre I., Segers T., Ashkani-Esfahani S., Guss D., De Cesar Netto C., et al. (2023). Implementing automated 3D measurements to quantify reference values and side-to-side differences in the ankle syndesmosis. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 13774. [CrossRef]

- Burssens, A., Krähenbühl N., Weinberg M. M., Lenz A. L., Saltzman C. L., & Barg A. (2020). Comparison of External Torque to Axial Loading in Detecting 3-Dimensional Displacement of Syndesmotic Ankle Injuries. Foot & Ankle International, 41(10), 1256-1268. [CrossRef]

- Hennings, R., Souleiman F., Heilemann M., Hennings M., Klengel A., Osterhoff G., et al. (2021). Suture button versus syndesmotic screw in ankle fractures - evaluation with 3D imaging-based measurements. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 22(1), 970. [CrossRef]

- Souleiman, F., Heilemann M., Hennings R., Hennings M., Klengel A., Hepp P., et al. (2021). A standardized approach for exact CT-based three-dimensional position analysis in the distal tibiofibular joint. BMC Medical Imaging, 21(1), 41. [CrossRef]

- Boszczyk, A., Kwapisz S., Krümmel M., Grass R., & Rammelt S. (2018). Correlation of Incisura Anatomy With Syndesmotic Malreduction. Foot & Ankle International, 39(3), 369-375. [CrossRef]

- Boszczyk A., Kwapisz S., Krümmel M., Grass R., & Rammelt S. (2019). Anatomy of the tibial incisura as a risk factor for syndesmotic injury. Foot and Ankle Surgery, 25(1), 51-58. [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove C. T., Putnam S. M., Cherney S. M., Ricci W. M., Spraggs-Hughes A., McAndrew C. M., et al. (2017). Medial Clamp Tine Positioning Affects Ankle Syndesmosis Malreduction. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 31(8), 440-446. [CrossRef]

- Miller A. N., Barei D. P., Iaquinto J. M., Ledoux W. R., & Beingessner D. M. (2013). Iatrogenic Syndesmosis Malreduction via Clamp and Screw Placement. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 27(2), 100-106. [CrossRef]

- Spindler F. T., Gaube F. P., Böcker W., Polzer H., & Baumbach S. F. (2023). Value of Intraoperative 3D Imaging on the Quality of Reduction of the Distal Tibiofibular Joint When Using a Suture-Button System. Foot & Ankle International, 44(1), 54-61. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).