1. Introduction

Arterial hypertension is a major public health challenge worldwide and is a leading cause of cardiovascular and renal diseases [

1,

2]. The first line of treatment for hypertension is lifestyle changes, such as dietary changes, physical exercise and weight loss [

3]. Reducing blood pressure [by 5 mm Hg] can decrease the risks of stroke by 34% and ischemic heart disease by 21%, as well as reduce mortality from cardiovascular disease [

4].

Recently, much effort is being invested in screening for bioactive components in foods or diets for the treatment and prevention of hypertension [

5]. Morus alba L. is cultivated in eastern countries and its leaves have long been used to feed silkworms. To date, different parts of mulberry from root bark to leaves have been widely investigated for their health benefits, including antioxidant, hypolipidemic, antihyperglycemic, antiatherogenic, antiviral, antimicrobial, and neuroprotective effects [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. In animal studies, abnormally elevated blood pressure was normalized by ingestion of mulberry leaves [

11,

13]. Impaired blood vessel reactivity, including decreased dilation and increased constriction, was significantly restored to normal levels after long-term treatment with mulberry leaves [

9]. Some of these effects may be due to the inhibition of the angiotensin-converting enzyme, thus reducing angiotensin II levels. Another possible mechanism of antihypertensive action could be the content of c-aminobutyric acid [GABA] in mulberry leaves [

11].

In previous studies of our laboratory in two animal models of arterial hypertension [

14,

15] the antihypertensive effects of several flavonoid-rich extracts were related to an increase in nitric oxide levels. Thus, in the present study we have analyzed the cardiovascular, vascular, platelet and renal effects of an ethanolic extract of mulberry leaves Morus alba L. in an experimental model of arterial hypertension due to nitric oxide deficiency.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Morus Alba Extracts

Three types of mulberry leaf extracts from Morus alba were used. Two of them were ethanolic extracts, using 50% and 70% ethanol as the extracting agent respectively, and the third was an aqueous extract, with ultrapure water as the extracting agent. A Morus alba variety from the IMIDA Germplasm Bank (BAGERIM) was selected for its antioxidant effects in previous studies with Caenorhabditis elegans and its anti-inflammatory effects in obese mice [

16]. After the leaves were collected, they were washed, dried and freeze-dried. The 3 types of extracts were produced by the IMIDA Biotechnology Team. The methodology was adapted to each type of extraction according to the existing literature. Starting from the freeze-dried mulberry leaf, the extracts were prepared by incubating with shaking and alternating with sonication, with each type of extracting agent as appropriate. The samples were then centrifuged and filtered, and then concentrated and ethanol was removed using a rotary evaporator. As the last step of the extraction, all the extracts prepared were subjected to freeze-drying and stored at -20 °C until use. In preliminary experiments, all these extracts showed no toxicity in cultures of L929 cells as well as anti-inflammatory capacity and a good antioxidant activity (data not shown). The alcoholic extract made with 70% ethanol was chosen as the extract to be used in the animal studies.

2.2. Animals

All the experiments were performed in male Sprague–Dawley rats (grown and raised in the animal facilities of the Universidad de Murcia) housed in a temperature-controlled environment, with 12:12-h light-dark cycle in the Animal Care Facility of the University of Murcia (REGA ES300305440012). The animals were kept and treated according to the guidelines established by the European Union for the protection of animals used in experiments (86/609/EEC). All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Murcia (C1310050303).

2.3. Experimental Groups

Rats (8th week-old) were randomized into four groups: 1. Control (n = 8), rats without any treatment; 2. L-NAME (n = 8), rats receiving chronic L-NAME during 6 weeks (N-w-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester, 10 mg/kg/day); 3. MAE (n = 8), rats simultaneously treated with L-NAME plus the MAE extract (100 mg/kg/day given as gavage); 4. Captopril (n=8), rats simultaneously treated with L-NAME plus captopril (an inhibitor of angiotensin converting enzyme).

2.4. Experimental Procedures

Rats were maintained in their cages up to weeks 4 and 5 when they were progressively accustomed to individual metabolic cages (Tecniplast, Radnor, PA, USA) two days a week. Then, the week 6th, after two days of adaptation, we measured food and water intake and urinary volume in 24 h. The urine samples were collected and centrifuged (1000× g, 10 min) to remove solid matter and then kept at −80 °C for further analysis.

2.4.1. Measurement of Blood Pressure and Blood Extraction

After the metabolic study was completed, the animals were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (5 mg/Kg, i.p.) and placed on a heated table to maintain body temperature at 37 °C. A polyethylene catheter (PE-50) was placed in the right femoral artery to measure mean arterial pressure (MAP; Hewlett Packard 1280 pressure transducer and amplifier 8805D, Andover, MA, USA) and to collect blood samples, as previously described [

10,

11,

12]. Then, blood was collected into plastic tubes containing an anticoagulant solution (80 mmol/L sodium citrate, 52 mmol/L citric acid and 180 mmol/L glucose) to perform platelet aggregation studies. Thereafter, the animal was euthanized by opening the thorax. We extracted the descending thoracic aorta and placed it in a Petri dish containing oxygenated and pre-warmed Krebs solution for the vascular reactivity study.

2.4.2. Vascular Reactivity Study

The thoracic aorta was cleaned of adhering fat and connective tissue; care was taken not to disrupt vascular endothelium, as previously described [

14,

15]. Then, the aorta was cut into four rings (3–4 mm) and mounted in 10 mL organ baths (organ bath system LE 01004, Panlab, Barcelona, Spain) containing a physiological Krebs solution with the following composition (mM): NaCl, 118; KCl, 4.7; CaCl2, 2.5; MgSO4, 1.2; NaHCO3, 25; KH2PO4, 1.2; edetate calcium disodium, 0.026; and glucose, 5.6. The Krebs solution was maintained at 37 °C and continuously bubbled with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2. The rings are connected to isometric force transducers (TRI202P, Panlab) to detect tension changes that were acquired and analyzed with a data acquisition system (AD Instrument, Oxford, UK) consisting of a bridge amplifier (FE228), a data acquisition hardware (PowerLab 8/30) and a software (LabChart 6.0). Aortic rings were equilibrated for at least 45 min at a resting tension of 2 g before any specific experimental protocol was initiated. During this period, the bathing solution was replaced every 15 min and, if needed, the basal tone readjusted to 2 g. After the stabilization period, the aortic rings were constricted using a cumulative dose-response curve to phenylephrine (Phe, 10−9–10−4 mol/L), administered in 0.1 mL bolus. Then, the rings were washed (usually 2–3 times) until the resting tension was reached again and a second stabilization period of 30 min was allowed. To evaluate the vasodilator responses to acetylcholine (Ach), the aortic rings were pre-contracted with a submaximal dose of Phe (10−6 mol/L). Once a stable plateau was reached, a cumulative dose–response curve to the Ach (10−9–10−4 mol/L) was performed to assess the endothelium-dependent vasodilatation. Thereafter, the rings were frequently washed once again and a third stabilization period of 30 min was permitted and followed by an incubation period of 30 min with the NOS-inhibitor L-NAME (10−4 M) to inhibit NO synthesis. Next, a cumulative concentration-response curve to Ach was again performed, to evaluate the role of NO in the endothelium-dependent vasodilatation. Finally, we added a single dose of sodium nitroprusside (SNP, 10−4 M) to test the independent vasodilator responses and the functionality of the smooth muscle. The responses to Phe are expressed in grams and the relaxation to Ach and SNP as the percentage of the maximal Phe effect. Stock solutions of these drugs were prepared in distilled water and maintained frozen at −20 °C. Working solutions were prepared daily in Krebs solution. Drug concentrations are expressed as final bath concentrations. All reagents and vasoactive compounds were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Panreac (Barcelona, Spain).

2.4.3. Platelet Aggregation Study

Blood obtained as stated earlier was centrifuged to obtain platelet-rich plasma at 180g for 10 min. Then, as previously published [

17,

18] platelets were washed 2 times with Hepes buffer (136 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5.6 mM glucose, 35 mM HEPES, 0.42 mM NaH2PO4), to which 0.5 mM EGTA and albumin (3.5 mg/mL) were added and the pH was adjusted to 6.5. The washed platelets were resuspended in Hepes buffer without Ca2+, to which albumin (1 mg/mL) was added and the pH was adjusted to 7.4. The platelet concentration in the studies was 2x108 platelets/mL, adjusted by measuring their concentration with the hematology analyzer. Platelets were maintained at all times at 19°C in a thermostated bath. Ca2+ was added just before the start of the experiments. The aggregation response to two platelet agonists: adenosine diphosphate or ADP (0.75, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10 and 20 µM) and collagen (0.75, 1.25, 2.5 and 5 µM) was studied in a 2-channel optical aggregometer (Chronolog, model 700, Chronolog Corporation, Havertown, PA 19083, England).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as the arithmetic mean and standard deviation of the mean. To assess within-group differences in vascular reactivity studies, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for multiple comparisons. When significant results were obtained, Duncan's test was applied to identify statistical differences between pairs. The contractile response to phenylephrine is shown in grams, whereas relaxation responses to acetylcholine are expressed as a percentage of the phenylephrine-induced contraction. 50% effective dose (ED50) values were calculated by regression analysis for each ring separately, and between-group differences were assessed using Student's t test. For platelet aggregation studies, the area under the curve (AUC) and the slope of the responses was calculated individually. Between-group differences were analyzed by two-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons, and a post hoc Duncan test was performed if necessary. For other between-group comparisons, one-way analysis of variance was used. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses.

3. Results

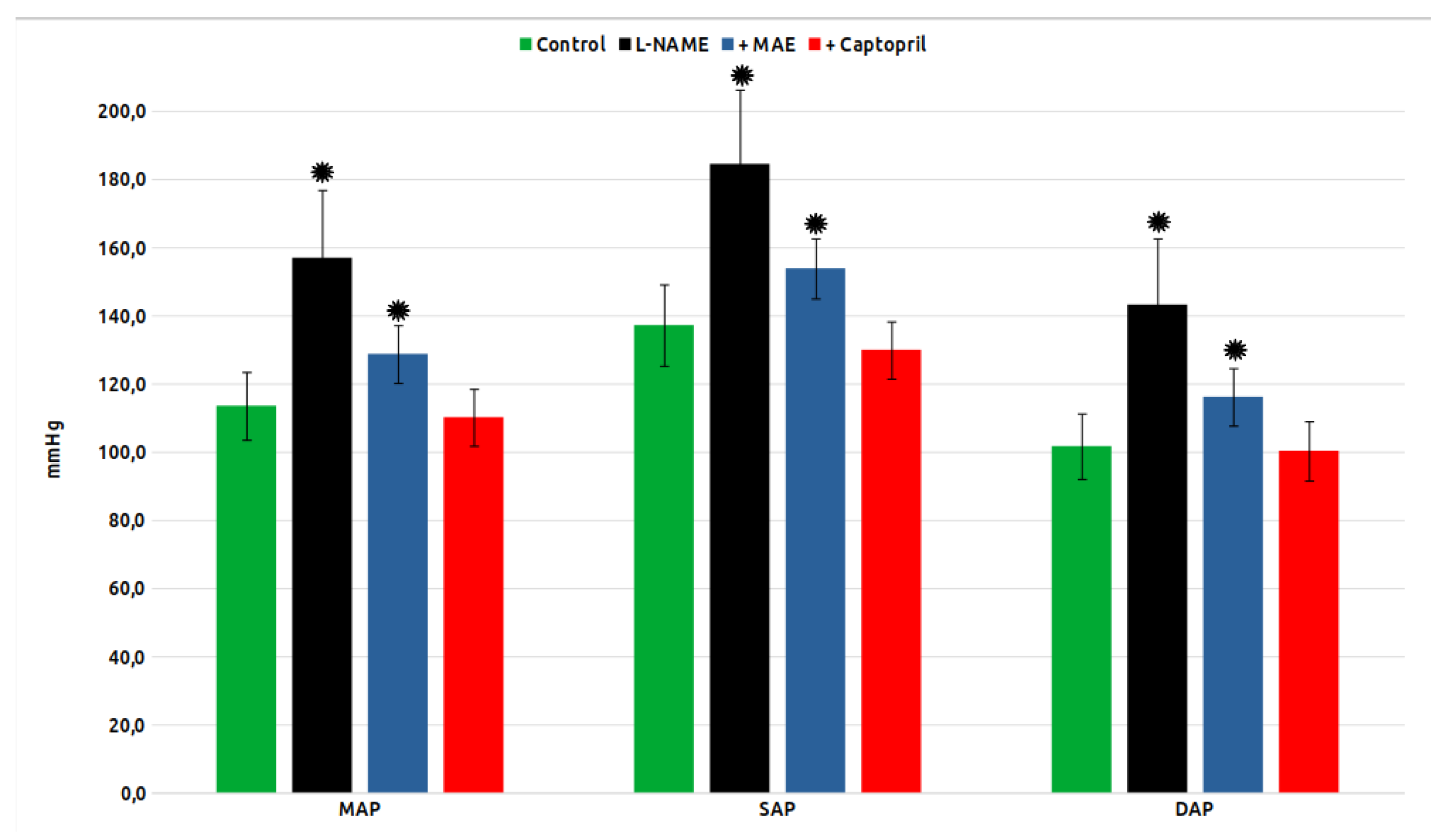

Mean arterial pressure (MAP), as well as systolic (SBP) and diastolic pressure (DBP) in the experimental groups are shown in

Figure 1. As can be seen, chronic treatment with L-NAME induced a strong increase in MAP, SBP and DBP, while the simultaneous treatment with MAE or Captopril significantly reduced it, although without reaching the values of the control group in the case of the group treated with the MAE extract.

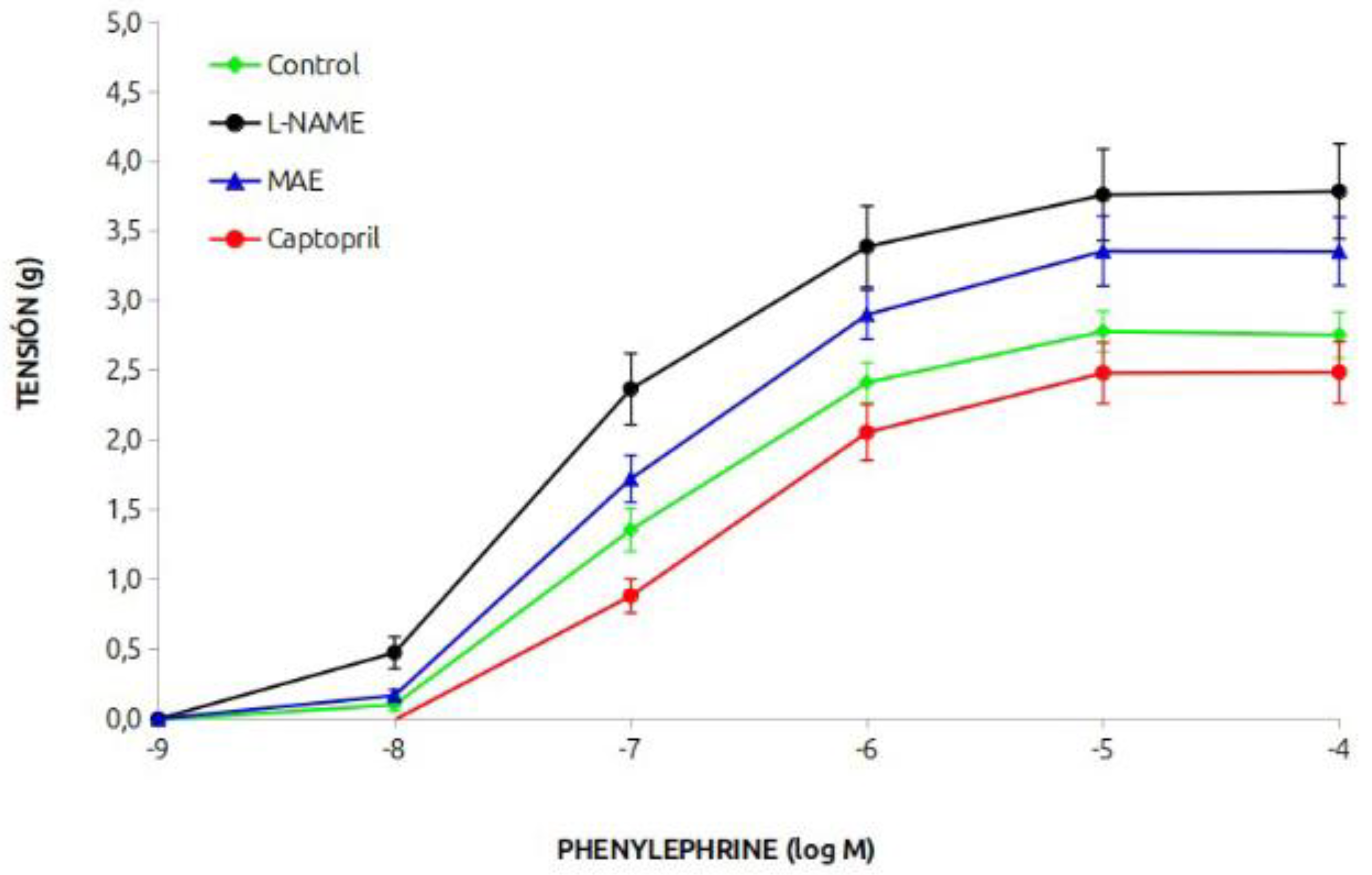

The vasoconstrictor response of the aortic rings to phenylephrine is shown in

Figure 2. The response of the group treated chronically with L-NAME was greater than that of the control group, and simultaneous treatment with MAE reduced it, but it was still greater than that of the control animals. Treatment with captopril reduced the vasoconstrictor response.

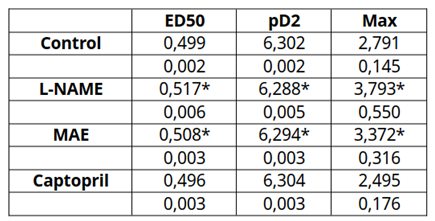

The data on the effective dose 50 (in mM), pD2 (-M) and maximum response (g) are shown in

Table 1. It can be seen those values were enhanced in the hypertensive animals whereas that of the animals treated with the morus extract was lower but still signficantly hogher than that of the control or the captopril groups.

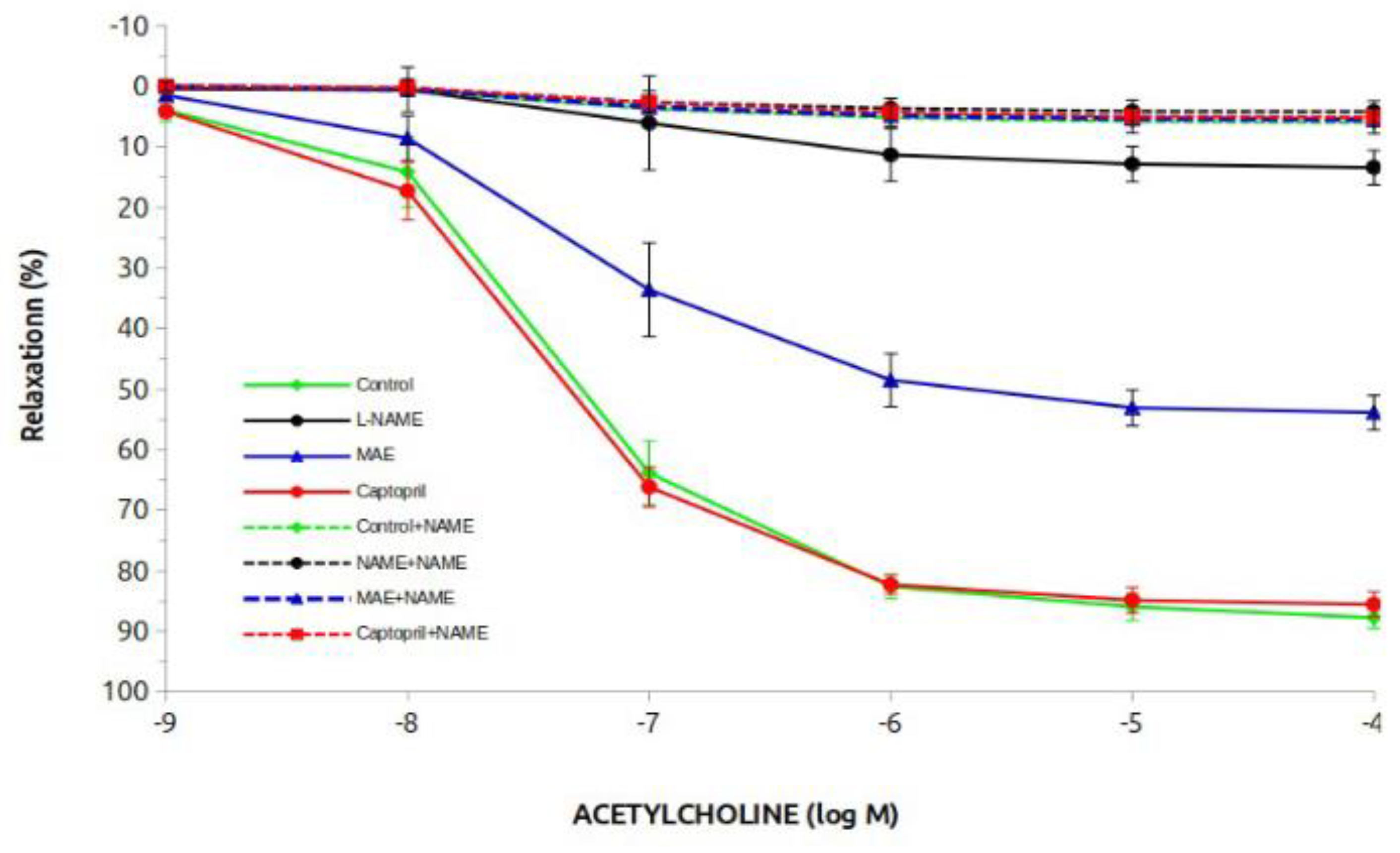

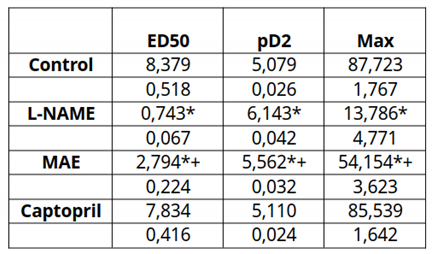

Figure 3 and

Table 2 show the results of the vasodilatory response to acetylcholine. The control and captopril groups showed the highest vasodilatory response (close to 90%), while the L-NAME group had a 10% response. Treatment with MAE in these animals clearly improved the vasodilatory response to almost 60%. In the case of the groups treated chronically with L-NAME, the vasodilatory response was practically abolished. This beneficial effect was due to the involvement of NO since it was completely elininated when L-NAME was added acutely to the rings. This response is better observed when looking at the ED50 or pD2 data. Differences statistically significant were observed in the L-NAME group treated with the morus extract compared to the L-NAME untreated group. The vasodilatory response to sodium nitroprusside at the end of the experiments was conserved at practically 100% with no differences between groups (data not shown).

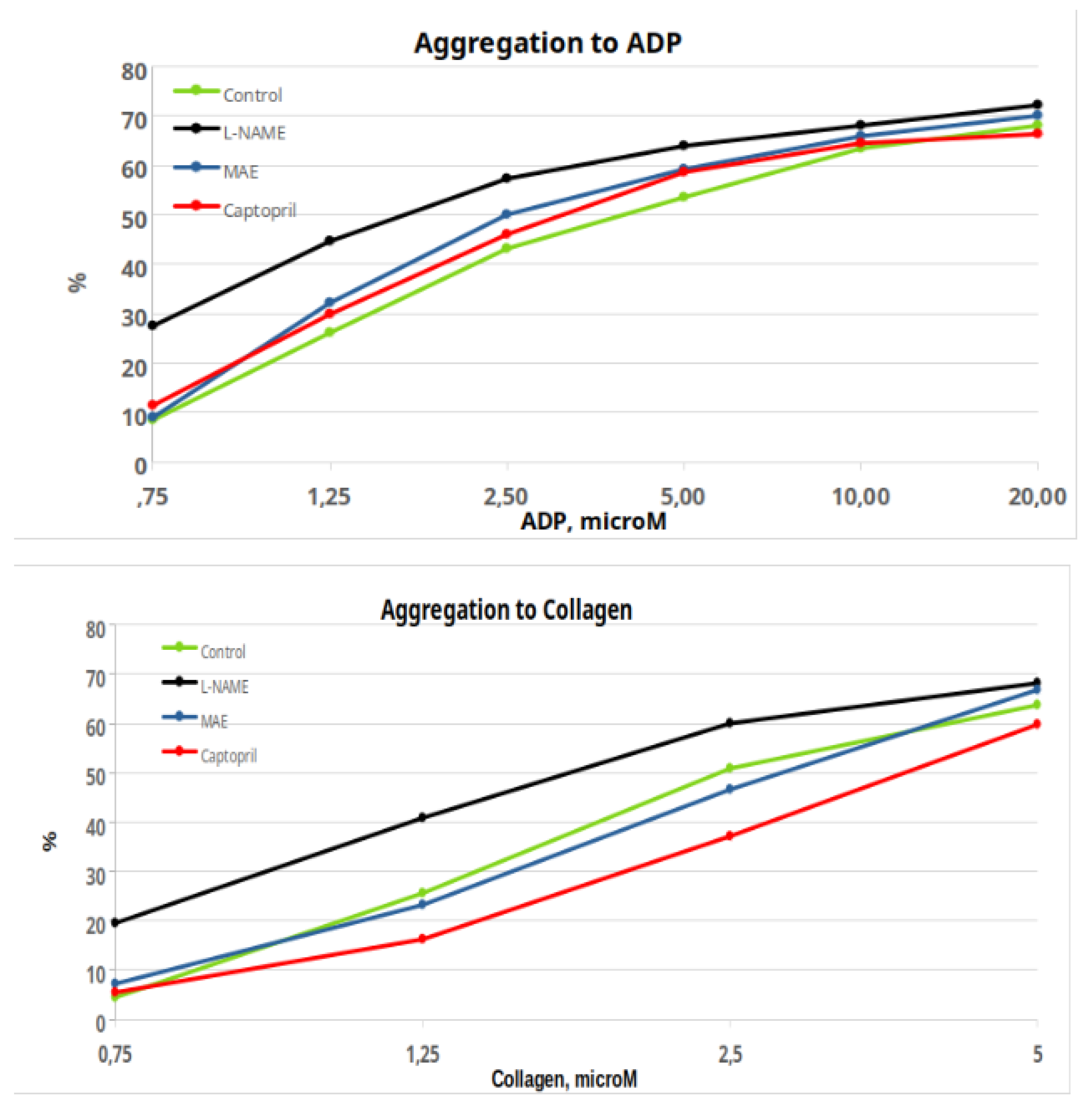

Figure 4 show the percentages of platelet aggregation in the groups of animals in response to ADP and collagen. Although the maximum values reached are quite similar, there are differences in the complete responses, as evidenced by the respective ANOVAs, which give a significant result between groups. The same occurs if we analyze the responses of the area under the curve and the slope of the curve (data not shown). It was decided not to do point-by-point statistics, which would probably give many results, but of difficult clinical interpretation. Instead, we have calculated the ED50 data of the different groups to obtain a clearer response, indicative or not of a change in the overall response (Table 3). Only the group treated chronically with MAE showed a lower ED50 in relation to the control group (p<0.05). There were no significant differences in any other comparisons.

4. Discussion

In our laboratory we have been working for the last few years on the role of flavonoids in an experimental model of arterial hypertension, the model of nitric oxide deficiency by administration of the inhibitor of its synthesis L-NAME. Thus, lemon extract, grapefruit extract, cocoa extract and apigenin were effective as antihypertensive agents, although to a moderate degree, in animals with L-NAME hypertension [

14,

15]. While the causes of spontaneous hypertension are multifactorial (genetics, sympathetic nervous system, renin-angiotensin system, among others), the causes of L-NAME hypertension are directly due to the decrease in NO production and indirectly to the overactivation of vasoconstrictor mechanisms such as the renin-angiotensin system and the increase in oxidative stress. Precisely these effects are the most cited as responsible for the actions of flavonoids. And where we have found the most effects has been in the level of blood pressure and in renal and vascular function. Therefore, when we had the opportunity to analyze the effects of another flavonoid such as Morus Alba extract, we did not hesitate to choose the most appropriate experimental model, that of L-NAME hypertension. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the vascular and renal effects of a Morus Alba extract (MAE) in a well-known experimental arterial hypertension model such as the inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis by L-NAME (L-NAME hypertension).

The treatment with MAE was well tolerated by the animals, as were the other treatments, and nothing significant was found to report. Regarding blood pressure, one of the important objectives analyzed, we have seen how MAP, as well as systolic (SBP) and diastolic (DBP) blood pressure increased significantly in the experimental groups treated with the NO synthesis inhibitor, L-NAME. These data are similar to those previously shown by our group [

14]. As observed, the use of the MAE extract had a significant MAP-reducing effect, or in other words, the hypertensive effect of L-NAME was largely prevented by the MAE extract. Although it remained a slightly higher value than that of the control group. Therefore, the MAE extract largely prevents arterial hypertension due to nitric oxide deficiency. It is important to note at this point that the group chronically treated with Captopril did show practically complete prevention of hypertension and this also coincides with previous studies from our laboratory [

14]. The main reason for this effect of captopril seems to be due to the inhibition of the formation of angiotensin II, which would be the main mechanism causing hypertension and its consequences [

19].

Another objective of our study was to analyze vascular reactivity in aortic rings. As observed, the vasoconstrictor response of the group treated chronically with L-NAME was higher than that of the control group, which coincides with our previous data and those in the literature [

14,

15] and this is due to the decrease in NO and therefore the vasodilatory protection against the increase in vascular tone. Interestingly, the treatment of hypertensive animals simultaneously with MAE reduced this greater reactivity to the vasoconstrictor, but it was still greater than that of the control animals, suggesting that the MAE extract could have increased the levels of NO in these aortic rings. Treatment with captopril reduced the vasoconstrictor response and practically normalized it, which has also been previously found by our group. These MAE data are confirmed by analyzing the values of the ED50 and the maximum response, which show a reduction in relation to the L-NAME group although without reaching the normal values of the control group. More evidence of this possible effect of MAE increasing NO production is observed in the vasodilation experiments with acetylcholine. While the vasodilatory response to acetylcholine is practically eliminated in the group treated chronically with L-NAME (13% of the control), the maximum vasodilation reaches 54% in animals treated with the MAE extract. All these differences were eliminated by adding L-NAME acutely, which allows us to conclude with certainty that treatment with the MAE extract improves vascular production of NO. As in other experiments, the direct response of the aortic smooth muscle after administration of sodium nitroprusside was perfectly preserved, which rules out a direct effect on the smooth muscle and also adds a safety factor in the performance of the experiments.

Regarding platelet aggregation, chronic treatment with L-NAME increased the aggregating response and treatment with the MAE extract significantly improved it and was normalized with captopril, especially at low doses as well. The same occurs if we analyze the responses of the area under the curve and the slopes of the curves. As can be seen, only the group treated chronically with MAE showed a lower ED50 in relation to the control group, although again, without reaching the data of the control group. In conclusion, the MAE extract reduces the greater platelet aggregation induced by chronic treatment with L-NAME, which indicates a very beneficial effect of the extract to improve platelet physiology in situations of excessive aggregation, which may allow a better vascular response. However, the results do not clarify whether this effect is due to the greater production of NO, as would seem logical to deduce.

In conclusion, Morus alba L extract has an antihypertensive effect, improves vascular reactivity and platelet aggregation in an experimental model of arterial hypertension due to nitric oxide deficiency. These effects seem to be related to an increase in the effects of nitric oxide.

Author Contributions

M. Akbari Aghdam and A. Pagán performed most of the experiments, J. García-Estañ supervised all the experimental protocols and procedure laboratories and N.M. Atucha was the director of the research. All authors contributed to the writing and have read and approved the final version.

Funding

This work has been partially supported by the European Commission ERDF/FEDER Operational Programme of Murcia (2021-2027), Project No. 50463 "Development of sustainable models of agricultural, livestock and aquaculture production" (Subproject: Innovation in the field of sericulture: New materials, biomaterials and extracts of biomedical interest).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Animal Experimentation Committee of the Universidad de Murcia (REGA ES300305440012).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Savica V, Bellinghieri G, & Kopple JD. The effect of nutrition on blood pressure. Annual Review of Nutrition, 2010, 30, 365–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forouzanfar MH, Liu P, Roth GA et al. Global Burden of Hypertension and Systolic Blood Pressure of at Least 110 to 115 mm Hg, 1990-2015. JAMA. 2017, 317, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charchar FJ, Prestes PR, Mills C et al. Lifestyle management of hypertension: International Society of Hypertension position paper endorsed by the World Hypertension League and European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2024, 42, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law M, Wald N, & Morris J. Lowering blood pressure to prevent myocardial infarction and stroke: A new preventive strategy. Health Technology Assessment 2003, 7, 1–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa M, Fujita H, Matoba N, et al. Bioactive peptides derived from food proteins preventing lifestyle related diseases. Biofactors 2000, 12, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Beshbishy HA, Singab ANB, Sinkkonen J, Pihlaja K. Hypolipidemic and antioxidant effects of Morus alba L. (Egyptian mulberry) root bark fractions supplementation in cholesterol-fed rats. Life Sciences 2006, 78, 2724–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harauma A, Murayama T, Ikeyama K et al. Mulberry leaf powder prevents atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2007, 358, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu LK, Chou FP, Chen YC, et al. Effects of mulberry (Morus alba L.) extracts on lipid homeostasis in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2009, 57, 7605–7611. [CrossRef]

- Naowaboot J, Pannangpetch P, Kukongviriyapan V et al. Mulberry leaf extract restores arterial pressure in streptozotocin-induced chronic diabetic rats. Nutr Res. 2009, 29, 602–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang LW, Juang LJ, Wang B et al. H. Antioxidant and antityrosinase activity of mulberry (Morus alba L.) twigs and root bark. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2011, 49, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang NC, Jhou KY, Tseng CY. Antihypertensive effect of mulberry leaf aqueous extract containing γ-aminobutyric acid in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 1796–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang R, Zhang Q, Zhu S, et al. Mulberry leaf (Morus alba L.): A review of its potential influences in mechanisms of action on metabolic diseases. Pharmacol Res. 2022, 175, 106029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nade VS, Kawale LA, Bhangale SP, Wale YB. Cardioprotective and antihypertensive potential of Morus alba L. in isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction and renal artery ligation-induced hypertension. J Nat Remedies. 2013, 13, 54–67. Available online: https://www.informaticsjournals.com/index.php/jnr/article/view/118.

- Paredes MD, Romecín P, Atucha NM, O'Valle F, Castillo J, Ortiz MC, García-Estañ J. Beneficial Effects of Different Flavonoids on Vascular and Renal Function in L-NAME Hypertensive Rats. Nutrients 2018, 10, 484–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paredes MD, Romecín P, Atucha NM, O'Valle F, Castillo J, Ortiz MC, García-Estañ J. Moderate Effect of Flavonoids on Vascular and Renal Function in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Nutrients. 2018, 10, 1107–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyva-Jiménez FJ, Ruiz-Malagón AJ, Molina-Tijeras JA et al. Comparative Study of the Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Leaf Extracts from Four Different Morus alba Genotypes in High Fat Diet-Induced Obesity in Mice. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romecín P, Navarro EG, Ortiz MC, Iyú D, García-Estañ J, Atucha NM. Bile Acids Do Not Contribute to the Altered Calcium Homeostasis of Platelets from Rats with Biliary Cirrhosis. Front Physiol. 2017, 8, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbari Aghdam M, Romecín P, García-Estañ J, Atucha NM. Role of Nitric Oxide in the Altered Calcium Homeostasis of Platelets from Rats with Biliary Cirrhosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 10948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Estañ J, Ortiz MC, O'Valle F, Alcaraz A, Navarro EG, Vargas F, Evangelista S, Atucha NM. Effects of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors in combination with diuretics on blood pressure and renal injury in nitric oxide-deficiency-induced hypertension in rats. Clin Sci (Lond). 2006, 110, 227–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).