1. Introduction

Positionality in research refers to how a researcher’s background, experiences, and social position influence their approach to research and their relationships with participants [

1]. This concept has become increasingly important in qualitative research, where researchers often engage deeply with participants through interviews, observations, and interpretative analysis. Recent studies suggest that between 60-75% of qualitative researchers face challenges in managing their positionality effectively, particularly when working with diverse communities or sensitive topics [

2]. As a result, the complex nature of researcher-participant relationships underscores the need for understanding and addressing positionality as a crucial step toward producing credible and ethical research outcomes.

The concept of trustworthiness stands as a cornerstone of qualitative research quality, encompassing elements such as credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability [

3,

4]. While traditional approaches to establishing trustworthiness have primarily focused on methodological rigor and systematic analysis procedures, recent scholarship suggests that the researcher’s positionality plays an equally vital role in shaping research trustworthiness [

5]. Consequently, this shift reflects a growing recognition that the researcher’s identity, assumptions, and social location significantly influence not only data collection but also its interpretation and the representation of findings.

Understanding the relationship between positionality and trustworthiness has become particularly relevant in today’s diverse research landscape. Qualitative researchers increasingly work across cultural, social, and professional boundaries, making the impact of their position more pronounced [

6]. Studies further indicate that researchers who actively reflect on and address their positionality tend to build stronger relationships with participants, which leads to richer data and more nuanced interpretations [

7]. Building on this foundation, scholars have identified several key dimensions of positionality that directly influence research trustworthiness, such as cultural background, professional experience, gender identity, socioeconomic status, and personal beliefs about the research topic [

8]. These dimensions can create both opportunities and challenges in the research process. For instance, researchers with insider status in their studied communities often benefit from increased access and trust but may struggle with maintaining analytical distance [

9]. Conversely, those studying populations different from their own background might bring fresh perspectives but face greater challenges in establishing rapport and achieving cultural understanding [

10].

The practical implementation of positionality awareness in research requires specific strategies and tools. Recent methodological innovations have introduced frameworks for systematic reflection on researcher position throughout the research process. These approaches emphasize continuous self-examination through methods such as reflexive journaling, peer debriefing, and participant consultation, which are shown to enhance participant engagement and result in more robust findings. However, despite the growing recognition of positionality’s importance, researchers continue to face challenges in effectively integrating positional awareness into their methodological frameworks. Studies suggest that many qualitative researchers struggle to balance personal disclosure with professional boundaries, particularly when researching sensitive topics or vulnerable populations. To address these challenges, the present study proposes a comprehensive methodological framework that systematically integrates positionality awareness into qualitative research practices.

2. Concept of Positionality

Positionality encompasses the complex interplay of a researcher’s social identity, cultural background, personal experiences, and power relations that shape their approach to research [

11]. These elements create a unique lens through which researchers view, interpret, and present their findings, influencing every stage of the research process. Recent studies indicate that approximately 70% of qualitative researchers report that their personal backgrounds significantly influence their research decisions, from participant selection to data interpretation [

12]. This influence becomes particularly crucial when researchers work across cultural boundaries or with marginalized communities, as power dynamics can substantially shape research relationships and outcomes.

The dimensions of positionality extend beyond simple demographic characteristics to include deeper aspects such as cultural values, professional experience, and personal biases. For instance, a researcher’s socioeconomic background might affect their understanding of economic hardship, while their cultural heritage could influence how they interpret certain behaviors or traditions [

13]. Moreover, power dynamics, arising from factors like educational status, institutional affiliation, or social privilege, play a particularly significant role in shaping researcher-participant relationships and the quality of data collected. These various dimensions intersect and interact, creating complex positioning that researchers should navigate thoughtfully. Consequently, addressing these intricacies is essential for ensuring both ethical research practices and robust findings.

A key tool in understanding and managing positionality is reflexivity - the systematic process of examining one’s own assumptions, biases, and position within the research context [

14]. Through reflexive practices, researchers gain greater insight into how their background shapes their research choices and interpretations, enabling them to approach their work with greater intentionality and ethical consideration. This awareness is particularly vital in qualitative research, where the researcher serves as the primary instrument for data collection and analysis. Studies consistently show that researchers who engage in regular reflexive practices, such as maintaining reflexive journals or participating in peer debriefing sessions, demonstrate heightened awareness of their positional influences and make more informed methodological decisions [

15].

Furthermore, reflexivity helps researchers identify and address potential blind spots or biases that might arise from their particular position. By actively questioning their assumptions and acknowledging their limitations, researchers can work towards more transparent and ethically sound research practices. This ongoing process of self-examination and adjustment not only supports ethical rigor but also enhances the credibility of the research findings. In sum, reflexivity serves as a dynamic tool that enables researchers to maintain awareness of how their positionality influences different stages of the research process, from initial design through final interpretation and representation of findings.

3. Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research

Trustworthiness in qualitative research represents the overall quality and rigor of the research process, encompassing four key components established by Lincoln and Guba’s seminal work: credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability [

16]. Credibility refers to the confidence in the truth of research findings, while dependability ensures the findings are consistent and could be repeated. Confirmability focuses on the degree to which findings are shaped by participants rather than researcher bias, and transferability addresses how findings might apply to other contexts [

17]. Despite their foundational role, researchers often face difficulties in meeting these components, particularly in the context of complex social phenomena or sensitive topics. Recent studies indicate that approximately 65% of qualitative researchers struggle with at least one aspect of establishing trustworthiness [

18].

Qualitative researchers face numerous challenges in establishing trustworthiness across these components. One primary challenge involves demonstrating the systematic nature of their research process while maintaining the flexibility that qualitative approaches require [

19]. Additionally, researchers should balance the need for rich, detailed descriptions with practical constraints such as word limits and participant privacy concerns [

20]. These difficulties are further compounded by the subjective nature of qualitative data interpretation, which may limit confirmability, particularly when researchers work independently or lack peer review opportunities. Traditional methods for enhancing trustworthiness include techniques such as member checking, peer debriefing, audit trails, and thick description [

3].

While these methods address specific aspects of trustworthiness, each comes with its own limitations. For instance, member checking can enhance credibility but may be complicated by power dynamics or participants’ changing perspectives over time [

21]. Similarly, audit trails contribute to dependability but can become overwhelming in large-scale qualitative studies where decision points are numerous and complex [

19]. In response to these limitations, recent methodological innovations have emerged, introducing more comprehensive approaches. These include integrated frameworks that combine multiple validation strategies, digital tools for systematic documentation, and collaborative approaches to data analysis [

19,

22]. However, these newer methods still face challenges in addressing the full spectrum of trustworthiness concerns, particularly in relation to how researcher positionality influences the implementation and effectiveness of these strategies.

4. Linking Positionality to Trustworthiness

The relationship between positionality and trustworthiness in qualitative research represents a critical intersection that shapes research quality and validity [

11]. When researchers actively acknowledge and address their positionality, they enhance multiple aspects of trustworthiness simultaneously. For instance, transparent discussion of researcher background and potential biases strengthens confirmability, while detailed reflection on how positionality influences research relationships enhance credibility [

23]. Studies indicate that researchers who explicitly address their positionality throughout their research process report higher levels of participant trust and more robust data collection outcomes [

5]. This evidence underscores the importance of integrating reflexivity into all stages of the research process to ensure a more transparent and credible methodology.

The impact of positionality on research processes manifests in various ways across different research stages. During data collection, a researcher’s cultural background and social position can affect how participants share information and what details they choose to disclose [

24]. For example, researchers studying communities similar to their own background might gain easier access and deeper insights, but may also overlook certain phenomena due to overidentification [

25]. Similarly, during data analysis, positionality shapes the interpretation of findings, where personal experiences and theoretical orientations influence coding and theme identification, potentially impacting the validity of the conclusions drawn [

5,

11].

Managing these positional influences effectively requires specific tools and strategies that promote ongoing reflection and awareness. Reflexivity journals serve as a primary tool, allowing researchers to document their thoughts, reactions, and decision-making processes throughout the research journey [

7]. These journals provide a systematic way to track how personal perspectives might influence research interpretations and help researchers maintain awareness of potential biases. Similarly, bracketing exercises, where researchers explicitly identify and set aside their preconceptions, help minimize the impact of personal assumptions on data analysis. To complement these individual efforts, peer debriefing sessions provide opportunities for collaborative reflection, offering alternative perspectives that can identify blind spots and enhance the credibility of findings [

26]. Through regular discussions with colleagues or research team members, researchers can gain alternative perspectives on their interpretations and identify potential blind spots in their analysis [

27]. These collaborative discussions are particularly effective when peers come from different backgrounds or theoretical orientations, as they can highlight how different positional perspectives might lead to varying interpretations of the same data. Ultimately, integrating these tools—reflexivity journals, bracketing, and peer debriefing—into research practice not only strengthens the trustworthiness of findings but also encourages a more holistic understanding of the complexities within qualitative research contexts.

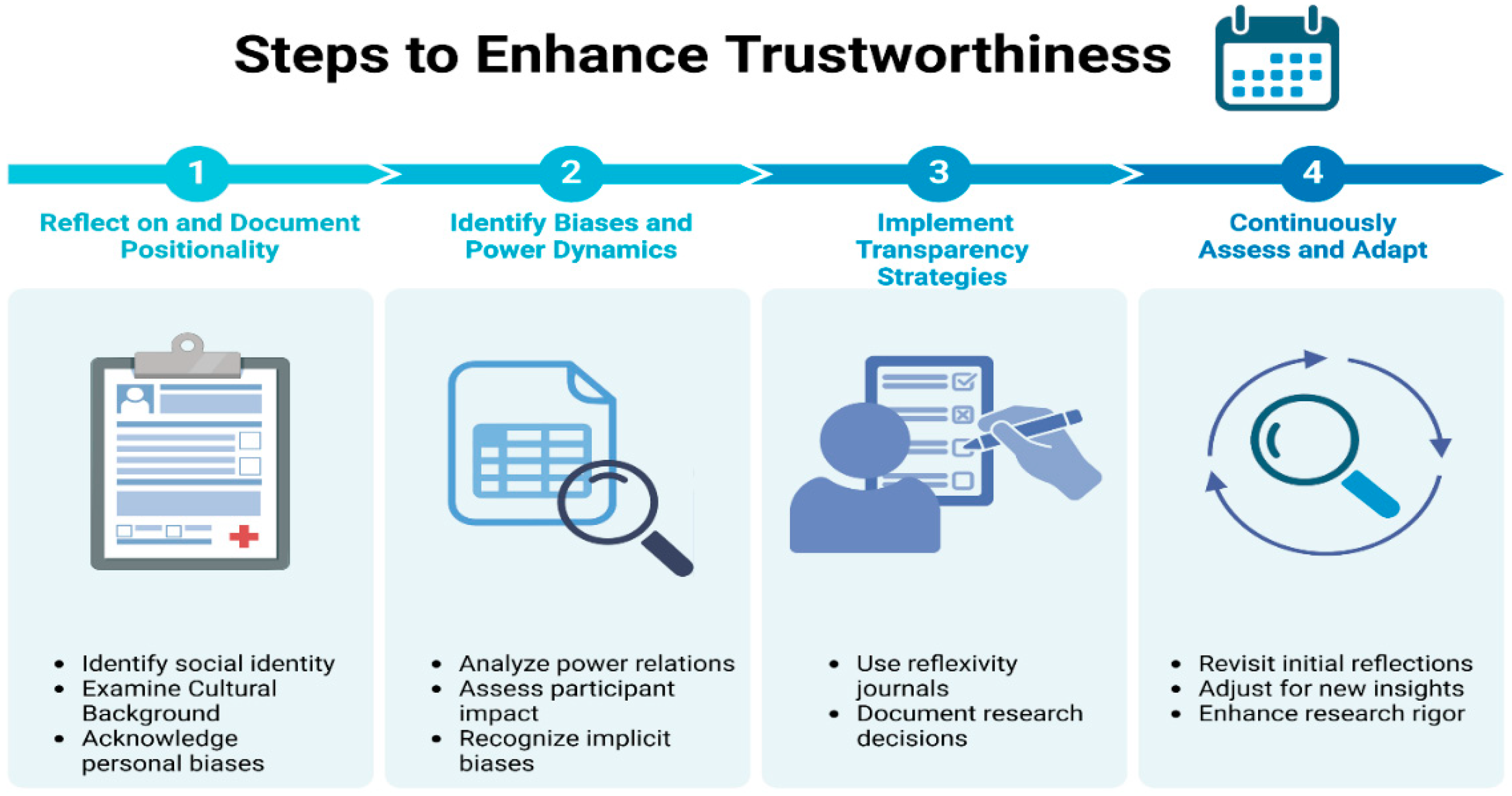

5. Methodological Framework for Enhancing Trustworthiness

Developing a systematic approach to integrating positionality awareness into qualitative research requires a structured framework that guides researchers through key stages of reflection and action. The first essential step involves comprehensive self-reflection, where researchers document their personal and professional backgrounds, values, and assumptions that might influence their research. Studies suggest that researchers who spend dedicated time mapping their positionality before beginning fieldwork demonstrate greater awareness of potential biases throughout their research journey [

28,

29]. This preparatory phase lays the groundwork for a more intentional and reflective research process, promoting greater alignment between researcher awareness and methodological rigor.

The second step focuses on identifying specific biases and power dynamics that might emerge in the research context. This involves analyzing how different aspects of the researcher’s position might interact with the study population and setting. For example, researchers must consider how their educational background, institutional affiliation, or cultural identity might create power imbalances or influence participant responses. Addressing these dynamics early enables researchers to proactively design mitigation strategies, fostering more equitable interactions with participants and enhancing credibility. Recent research indicates that systematic bias identification early in the research process leads to more effective mitigation strategies and stronger trustworthiness outcomes [

30].

The third step emphasizes implementing concrete strategies for transparency throughout the research process. This includes developing detailed documentation protocols, creating structured reflection templates, and establishing regular check-in points for assessing positional influences. Digital tools and standardized forms can streamline this process, allowing researchers to systematically track their decisions and positional reflections while making their methodology more accessible and verifiable to others. Studies show that researchers who maintain consistent documentation of their positional reflections produce more trustworthy and transparent research outcomes [

5].

The final step involves continuous assessment and adaptation throughout the study period. This ongoing process requires researchers to regularly revisit their initial positional reflections and adjust their approaches as new insights emerge. Practical tools for this stage include reflexive journals with structured prompts, peer debriefing schedules, and participant feedback mechanisms that help researchers track and respond to evolving positional dynamics. Integrating these tools into a continuous feedback loop ensures that researchers remain attuned to shifting contexts and positionality challenges, ultimately strengthening the validity and reliability of their findings. (

Figure 1)

6. Conclusion

In concluding this exploration of the role of positionality in enhancing trustworthiness within qualitative research, it is evident that positionality serves as both a lens and a tool for fostering ethical and credible research practices. The proposed methodological framework underscores the critical importance of integrating positionality awareness at every stage of the research process, from initial reflection to final interpretation and dissemination of findings. The foundational elements of the framework—self-reflection, bias identification, transparency, and continuous adaptation—create a structured pathway for qualitative researchers to actively manage their positional influences. Reflexive tools such as journaling, peer debriefing, and structured documentation emerge as essential components in ensuring that research remains both participant-centered and methodologically sound. Additionally, the framework’s emphasis on continuous assessment aligns with the evolving nature of qualitative research, where dynamic interactions and emergent insights necessitate flexibility and adaptability. Implementing this framework, however, requires researchers to navigate challenges, including balancing personal disclosure with professional boundaries and managing the influence of positionality on participant relationships. Addressing these challenges involves fostering a culture of reflexivity within research teams, utilizing collaborative tools, and leveraging technological advancements to streamline documentation and reflective practices. As qualitative research continues to expand across cultural, social, and disciplinary boundaries, the integration of positionality as a core methodological principle holds immense potential for enriching research outcomes and fostering trust with diverse communities. Moving forward, further exploration of innovative reflexive practices and their impact on trustworthiness is vital.

Data availability statement

No datasets were created or analyzed in this work; therefore, data sharing is not relevant.

Competing Interests

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all the peer reviewers and editors for their opinions and suggestions and for their support of this research.

Author Contributions

Abdulmalik Fareeq Saber solely conceived, designed, supervised, drafted, and approved the final manuscript.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

There are no reproduced materials in the current study.

References

- Holmes, A.G.D. Researcher Positionality--A Consideration of Its Influence and Place in Qualitative Research--A New Researcher Guide. Shanlax International Journal of Education 2020, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverio, S.A.; Sheen, K.S.; Bramante, A.; Knighting, K.; Koops, T.U.; Montgomery, E.; November, L.; Soulsby, L.K.; Stevenson, J.H.; Watkins, M. Sensitive, challenging, and difficult topics: Experiences and practical considerations for qualitative researchers. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2022, 21, 16094069221124739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.K. The pillars of trustworthiness in qualitative research. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health 2024, 2, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, D.C. Qualitative Research as the Cornerstone Methodology for Understanding Leadership Studies. In Leadership and Politics: New Perspectives in Business, Government and Society; Springer, 2024; pp. 555–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secules, S.; McCall, C.; Mejia, J.A.; Beebe, C.; Masters, A.S.; L. Sánchez-Peña, M.; Svyantek, M. Positionality practices and dimensions of impact on equity research: A collaborative inquiry and call to the community. Journal of Engineering Education 2021, 110, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, R. Now I see it, now I don’t: Researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative research 2015, 15, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos-Vega, F.M.; Stalmeijer, R.E.; Varpio, L.; Kahlke, R. A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE Guide No. 149. Medical teacher 2023, 45, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukamal, H. Deconstructing insider–outsider researcher positionality. British Journal of Special Education 2022, 49, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, M.J. On the inside looking in: Methodological insights and challenges in conducting qualitative insider research. The qualitative report 2014, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting-Toomey, S.; Dorjee, T. Communicating across cultures. Guilford Publications, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, D.; Mustafa, N. Social identity map: A reflexivity tool for practicing explicit positionality in critical qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2019, 18, 1609406919870075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polkinghorne, D.E. Language and meaning: Data collection in qualitative research. Journal of counseling psychology 2005, 52, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Mohammed, S.A.; Leavell, J.; Collins, C. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Annals of the new York Academy of Sciences 2010, 1186, 69–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corlett, S.; Mavin, S. Reflexivity and researcher positionality. The SAGE handbook of qualitative business and management research methods 2018, 377–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembele, L.; Nathan, S.; Carter, A.; Costello, J.; Hodgins, M.; Singh, R.; Martin, B.; Cullen, P. Researching With Lived Experience: A Shared Critical Reflection Between Co-Researchers. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2024, 23, 16094069241257945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayre, C.M. Data analysis and trustworthiness in qualitative research. In Research methods for student radiographers; CRC Press, 2021; pp. 145–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyirenda, L.; Kumar, M.B.; Theobald, S.; Sarker, M.; Simwinga, M.; Kumwenda, M.; Johnson, C.; Hatzold, K.; Corbett, E.L.; Sibanda, E. Using research networks to generate trustworthy qualitative public health research findings from multiple contexts. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International journal of qualitative methods 2017, 16, 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M. What is qualitative research? Australasian Marketing Journal 2024, 14413582241264619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, J.L.; Balmer, D.F.; Giardino, A.P. Qualitative research methods for medical educators. Academic pediatrics 2011, 11, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birt, L.; Scott, S.; Cavers, D.; Campbell, C.; Walter, F. Member checking: a tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qualitative health research 2016, 26, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sakao, T.; Huisingh, D.; Almeida, C.M. A comprehensive review of big data analytics throughout product lifecycle to support sustainable smart manufacturing: A framework, challenges and future research directions. Journal of cleaner production 2019, 210, 1343–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, I.H.Z.; Abd Patah, M.O.R.; Majid, M.A.A.; Usman, S.B.; Zulkornain, L.H. A Practical Guide to Improve Trustworthiness of Qualitative Research for Novices. Asian Journal of Research in Education and Social Sciences 2024, 6, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, A.; Korstjens, I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. European journal of general practice 2018, 24, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Burnett, D. Insider-outsider: Methodological reflections on collaborative intercultural research. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2022, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.E.K.; Nørgaard, L.S.; Cavaco, A.M.; Witry, M.J.; Hillman, L.; Cernasev, A.; Desselle, S.P. Establishing trustworthiness and authenticity in qualitative pharmacy research. Research in social and administrative pharmacy 2020, 16, 1472–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böckel, A.; Nuzum, A.-K.; Weissbrod, I. Blockchain for the circular economy: analysis of the research-practice gap. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2021, 25, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, C.V. Navigating pregnancy and scholarship: Exploring positionality, reflexivity, and intersectionality in research. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 2024; 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, R. Embracing the uncertain—figuring out our own stories of flexibility and ethics in the field. Gender, Place & Culture 2023, 30, 1126–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albahri, A.S.; Duhaim, A.M.; Fadhel, M.A.; Alnoor, A.; Baqer, N.S.; Alzubaidi, L.; Albahri, O.S.; Alamoodi, A.H.; Bai, J.; Salhi, A. A systematic review of trustworthy and explainable artificial intelligence in healthcare: Assessment of quality, bias risk, and data fusion. Information Fusion 2023, 96, 156–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).