Submitted:

25 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

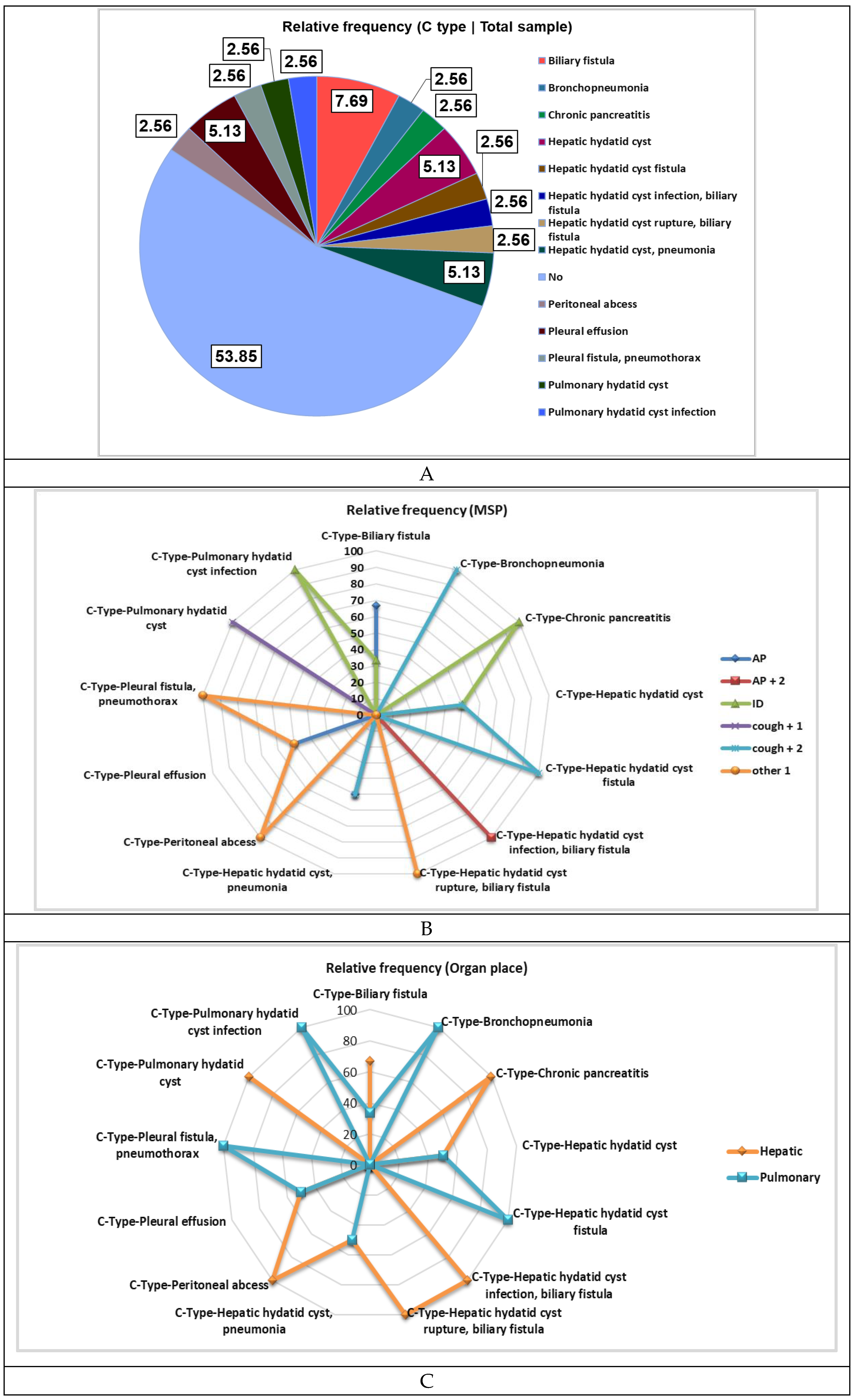

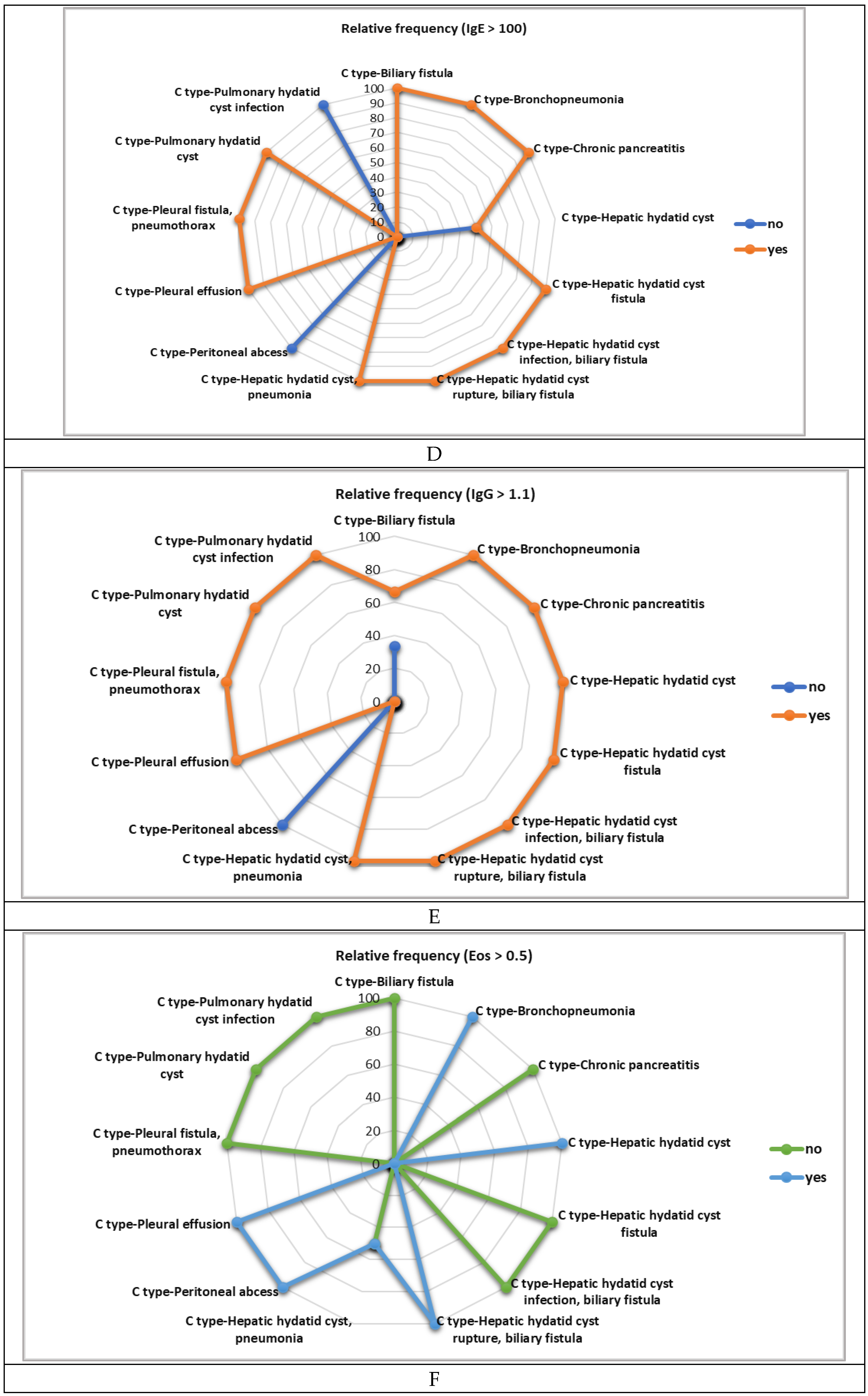

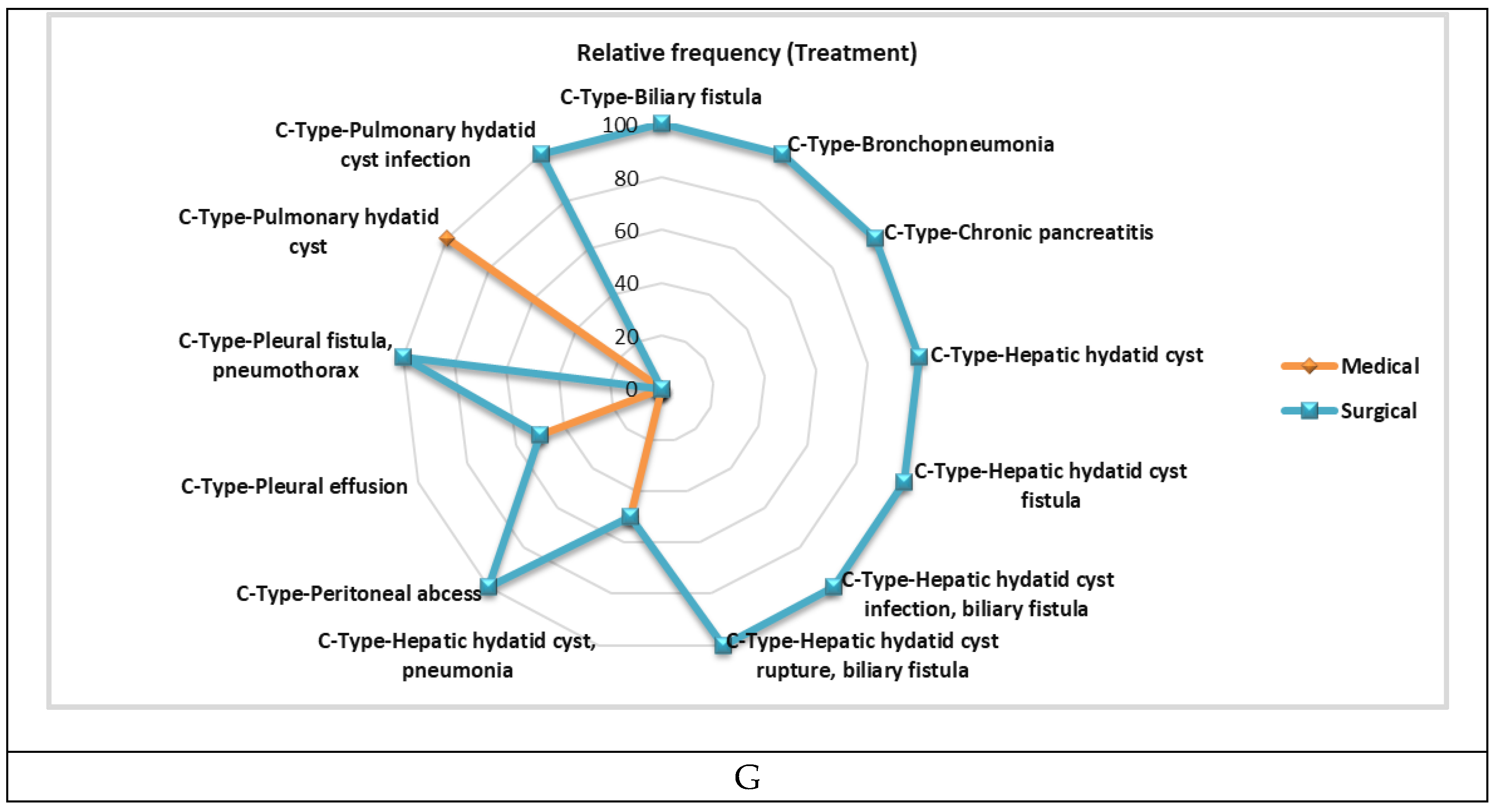

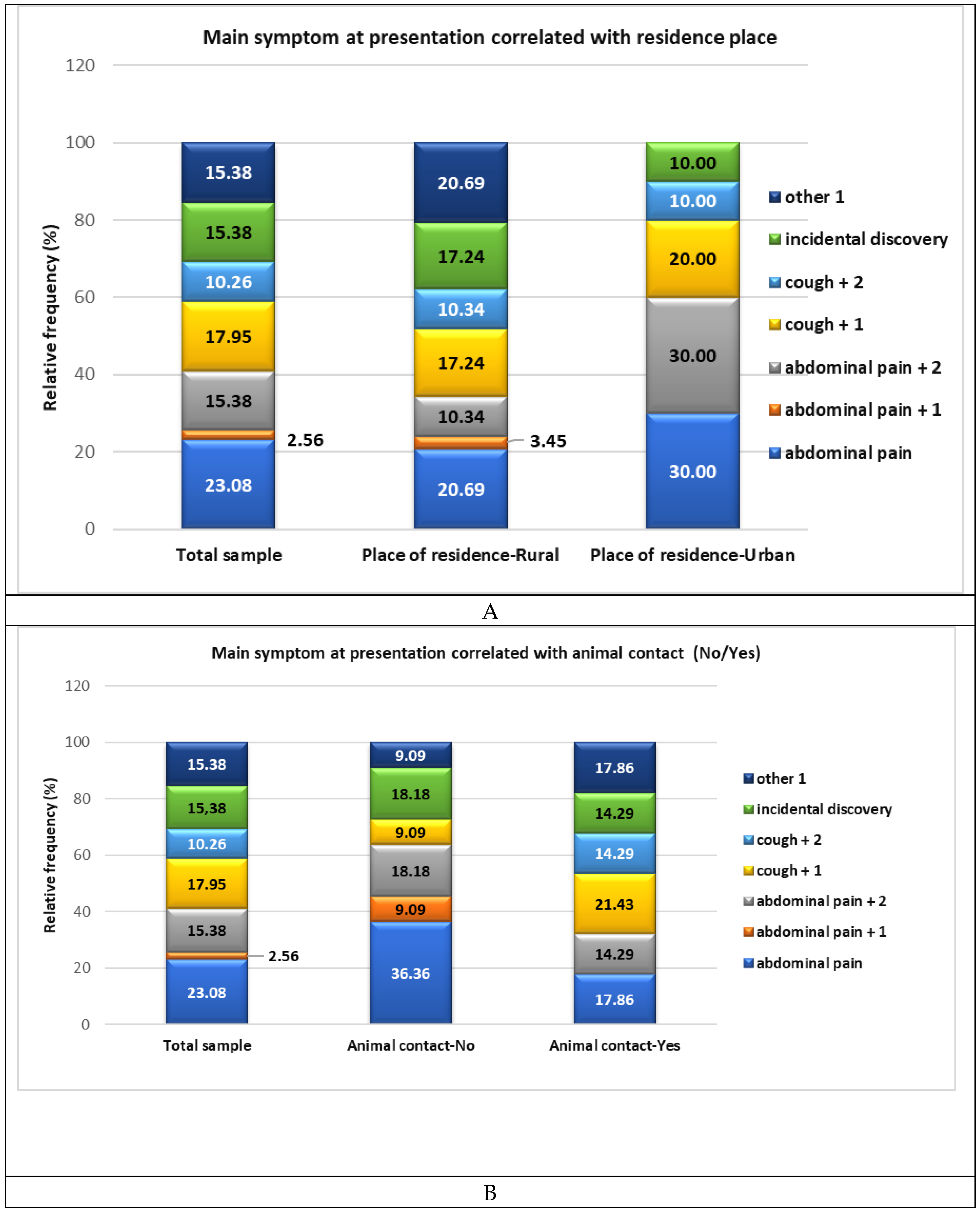

3. Results

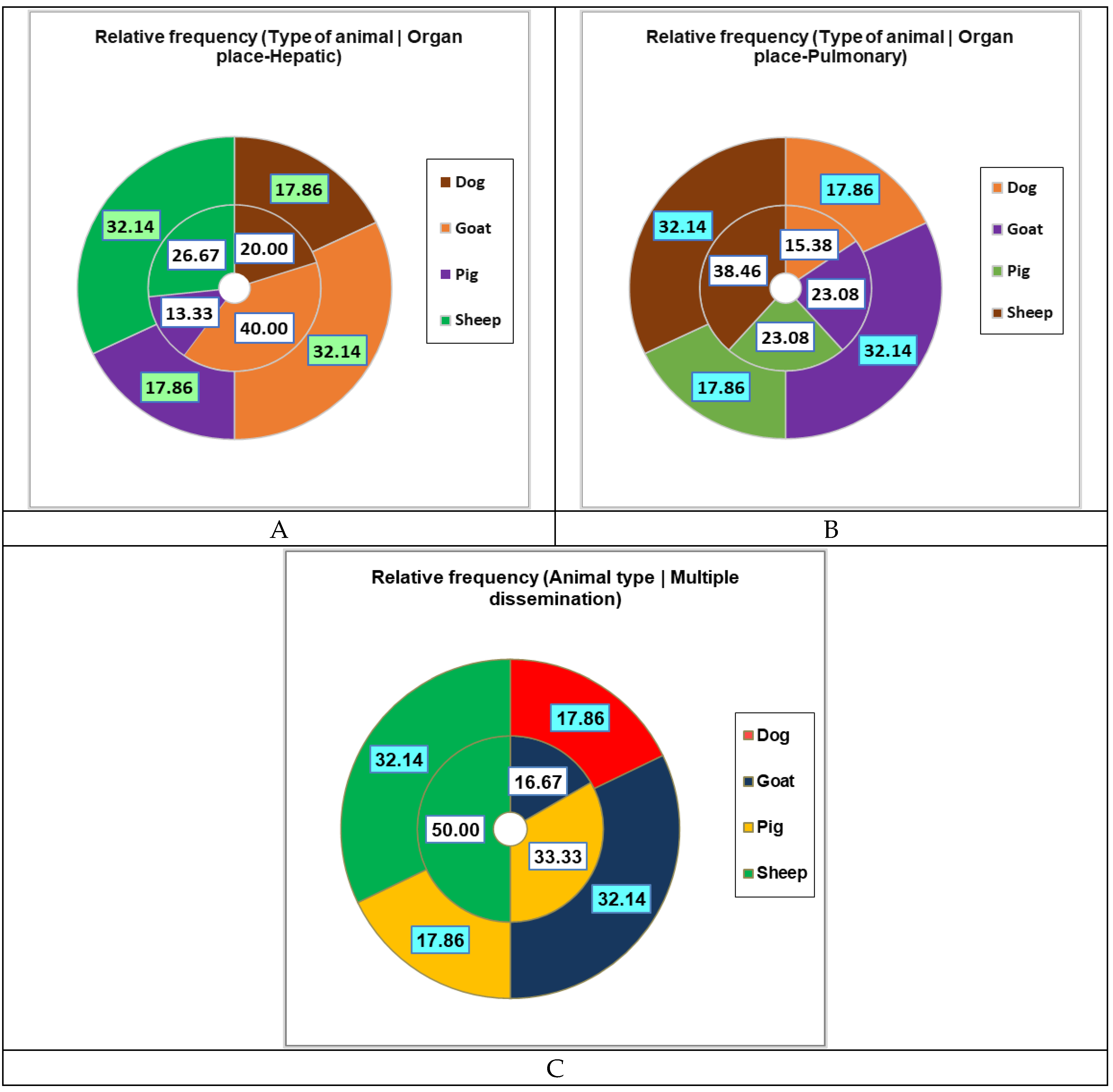

3.1. Sociodemographic and Epidemiological Characterization of Pediatric Patients

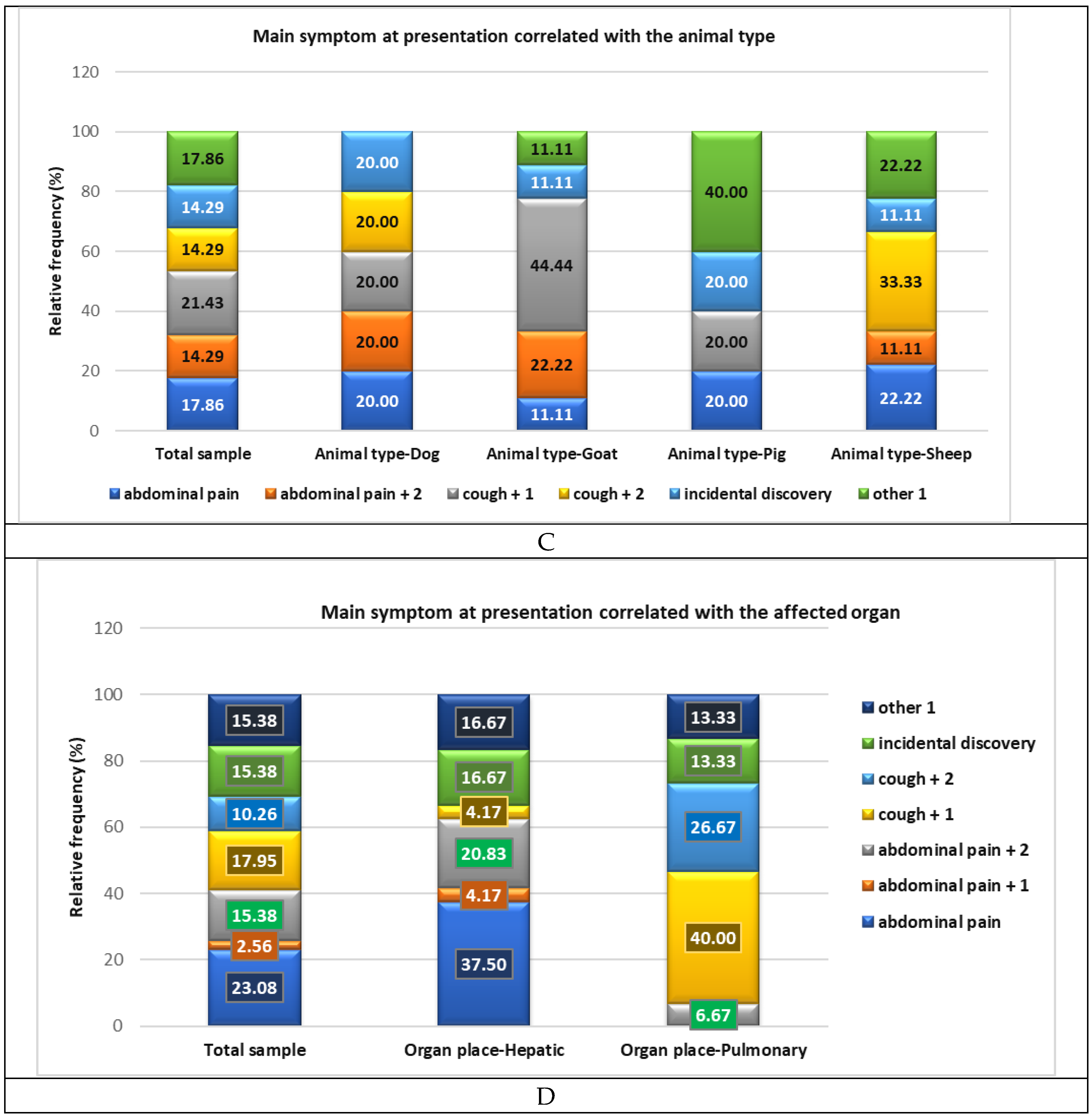

3.2. Main Symptoms at Presentation and Organ Involvement

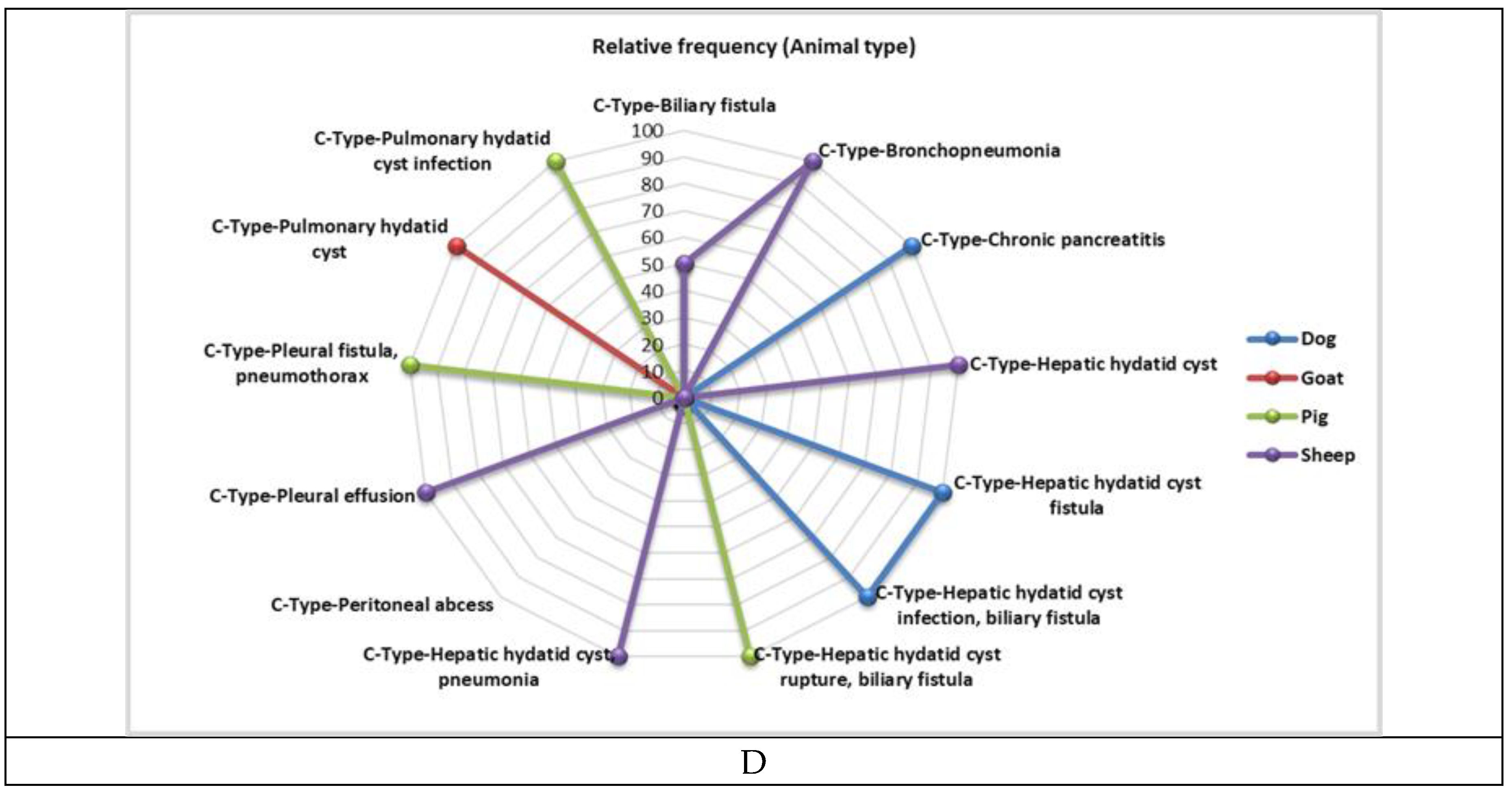

3.3. Laboratory Analyses, Evolution and Treatment

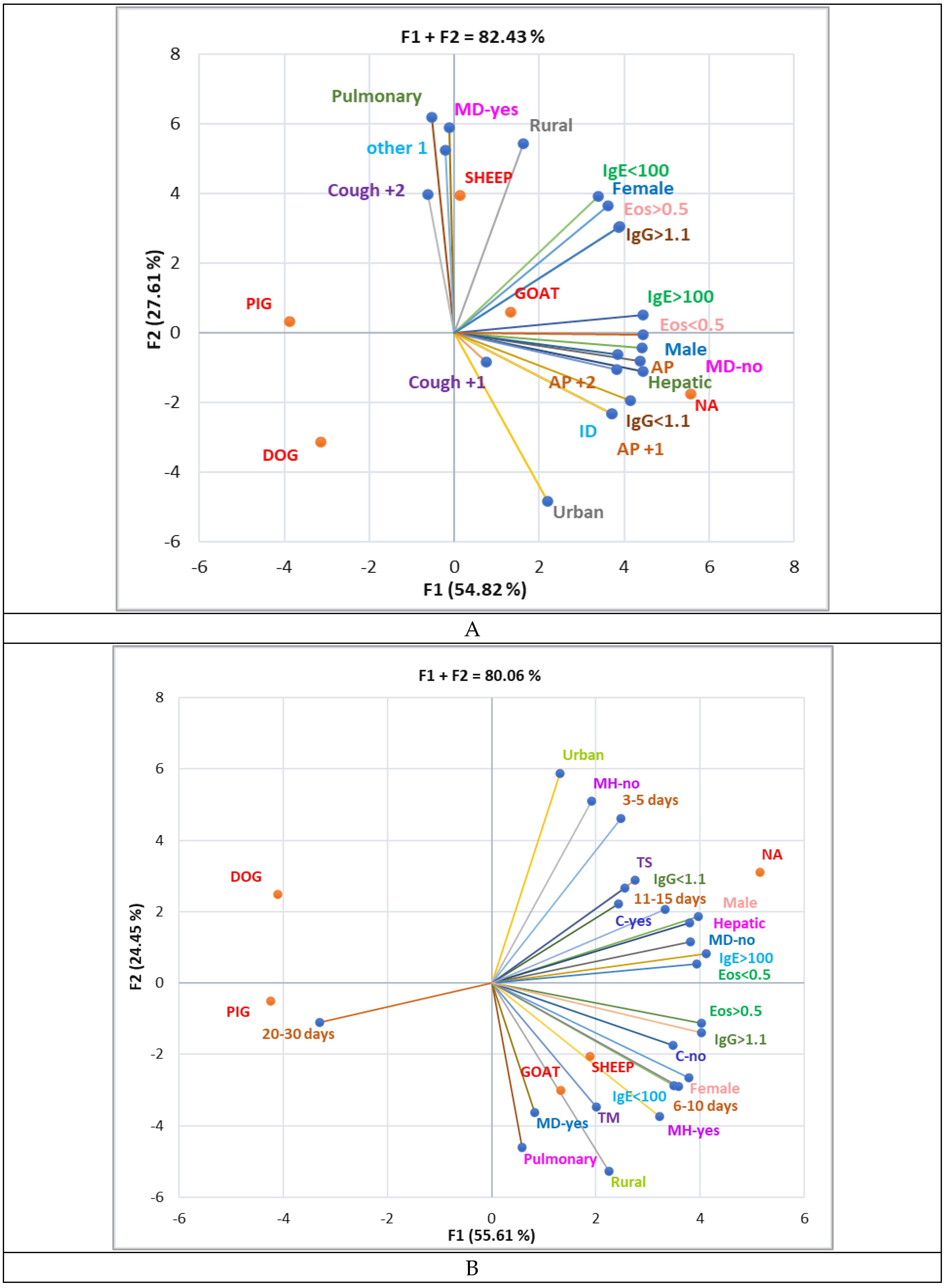

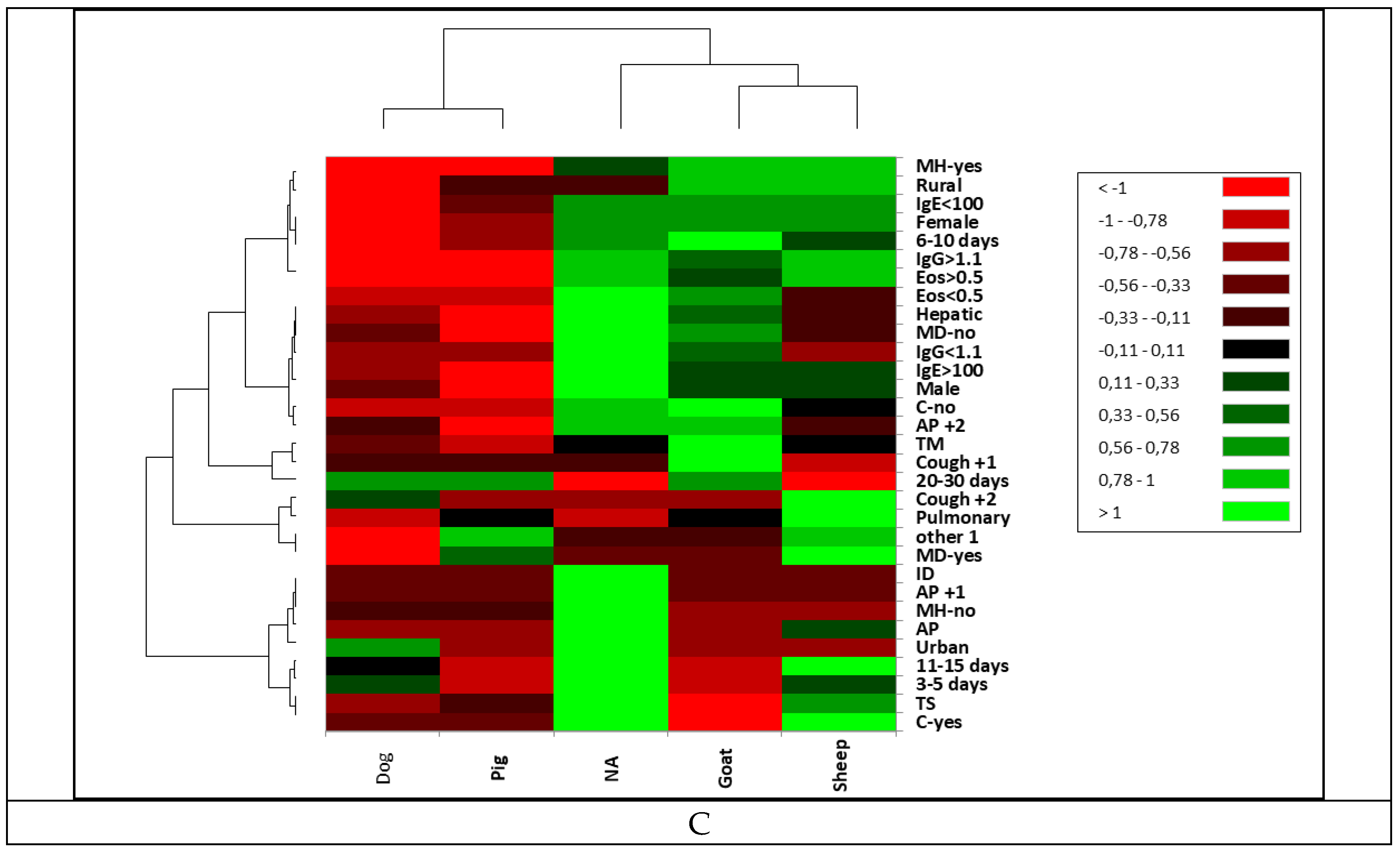

3.4. Correlation Between Sociodemographic Data and Clinical Findings

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paternoster, G.; Boo, G.; Wang, C.; Minbaeva, G.; Usubalieva, J.; Raimkulov, K.M.; Zhoroev, A.; Abdykerimov, K.K.; Kronenberg, P.A.; Müllhaupt, B.; et al. Epidemic Cystic and Alveolar Echinococcosis in Kyrgyzstan: An Analysis of National Surveillance Data. Lancet Glob Health 2020, 8, e603–e611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Ahmed, H.; Simsek, S.; Afzal, M.S.; Cao, J. Spread of Cystic Echinococcosis in Pakistan Due to Stray Dogs and Livestock Slaughtering Habits: Research Priorities and Public Health Importance. Front Public Health 2020, 7, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casulli, A.; Abela-Ridder, B.; Petrone, D.; Fabiani, M.; Bobić, B.; Carmena, D.; Šoba, B.; Zerem, E.; Gargaté, M.J.; Kuzmanovska, G.; et al. Unveiling the Incidences and Trends of the Neglected Zoonosis Cystic Echinococcosis in Europe: A Systematic Review from the MEmE Project. Lancet Infect Dis 2023, 23, e95–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Ending the Neglected Tropical Diseases to Attain the Sustainable Development Goals. A Road Map for Neglected Tropical Diseases 2021–2030. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. 2020.

- Widdicombe, J.; Basáñez, M.-G.; Entezami, M.; Jackson, D.; Larrieu, E.; Prada, J.M. The Economic Evaluation of Cystic Echinococcosis Control Strategies Focused on Zoonotic Hosts: A Scoping Review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2022, 16, e0010568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutwiri, T.; Magambo, J.; Zeyhle, E.; Muigai, A.W.T.; Alumasa, L.; Amanya, F.; Fèvre, E.M.; Falzon, L.C. Findings of a Community Screening Programme for Human Cystic Echinococcosis in a Non-Endemic Area. PLOS Global Public Health 2022, 2, e0000235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqub, S.; Jensenius, M.; Heieren, O.E.; Drolsum, A.; Pettersen, F.O.; Labori, K.J. Echinococcosis in a Non-Endemic Country – 20-Years' Surgical Experience from a Norwegian Tertiary Referral Centre. Scand J Gastroenterol 2022, 57, 953–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindi, E.; Nino, F.; Simonini, A.; Cobellis, G. Giant Hydatid Lung Cyst in Non-Endemic Area. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep 2021, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.-M.; Cai, Q.-G.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.-S. Childhood Suffering: Hyper Endemic Echinococcosis in Qinghai-Tibetan Primary School Students, China. Infect Dis Poverty 2018, 7, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulos, A.S.; Chatzoulis, G.A. Echinococcus Granulosus in Childhood: A Retrospective Study of 187 Cases and Newer Data. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2019, 58, 864–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalki, E.; Al-Quarishy, S.; Abdel-Baki, A.-A.S. Assessment of Prevalence of Hydatidosis in Slaughtered Sawakny Sheep in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Biol Sci 2017, 24, 1534–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Scientific Analysis of the Islamic Rules on the Uncleanliness of Dogs from the Perspective of Medical Parasitology. Journal of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences 2023, 78–82. [CrossRef]

- Araujo, F.P.; Schwabe, C.W.; Sawyer, J.C.; Davis, W.G. Hydatid Disease Transmission in California: A Study of the Basque Connection. Am J Epidemiol 1975, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coello Peralta, R.D.; Coello Cuntó, R.A.; Yancha Moreta, C.; Guerrero Lapo, G.E.; Vinueza Sierra, R.L.; León Villalba, L.R.; Pazmiño Gómez, B.J.; Gómez Landires, E.A.; Ramallo, G. A Case of Hepatic Hydatid Cyst in a Woman Associated with the Presence of Echinococcus Granulosus in Her Domestic Dogs in a Marginal Urban Area from Ecuador. American Journal of Case Reports 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.S.; Jenkins, D.J.; Brookes, V.J.; Barnes, T.S. An Eight-Year Retrospective Study of Hydatid Disease (Echinococcus Granulosus Sensu Stricto) in Beef Cattle Slaughtered at an Australian Abattoir. Prev Vet Med 2019, 173, 104806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gareh, A.; Saleh, A.A.; Moustafa, S.M.; Tahoun, A.; Baty, R.S.; Khalifa, R.M.A.; Dyab, A.K.; Yones, D.A.; Arafa, M.I.; Abdelaziz, A.R.; et al. Epidemiological, Morphometric, and Molecular Investigation of Cystic Echinococcosis in Camel and Cattle From Upper Egypt: Current Status and Zoonotic Implications. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tüz, A.E.; Ekemen Keleş, Y.; Şahin, A.; Üstündağ, G.; Taşar, S.; Karadağ Öncel, E.; Kara Aksay, A.; Öztan, M.O.; Köylüoğlu, G.; Çapar, A.E.; et al. Hydatid Disease in Children from Diagnosis to Treatment: A 10-Year Single Center Experience. Turkish Journal of Parasitology 2022, 46, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawit, G.; Shishay, K. Epidemiology, Public Health Impact and Control Methods of the Most Neglected Parasite Diseases in Ethiopia: A Review. World Journal of Medical Sciences 2014, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, L.; Burkert, S.; Grüner, B. Parasites of the Liver – Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Clinical Management in the European Context. J Hepatol 2021, 75, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakala, T.; Molina, M.; Wu, G.Y. Hepatic Echinococcal Cysts: A Review. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2016, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Belhassen-García, M.; Romero-Alegria, A.; Velasco-Tirado, V.; Alonso-Sardón, M.; Lopez-Bernus, A.; Alvela-Suarez, L.; Perez Del Villar, L.; Carpio-Perez, A.; Galindo-Perez, I.; Cordero-Sanchez, M.; et al. Study of Hydatidosis-Attributed Mortality in Endemic Area. PLoS One 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.E.; Abdalla, S.S.; Adam, I.A.; Grobusch, M.P.; Aradaib, I.E. Prevalence of Cystic Echinococcosis and Associated Risk Factors among Humans in Khartoum State, Central Sudan. Int Health 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, J.R.; Gemmell, M.A. Transmission of Taeniid Tapeworm Eggs via Blowflies to Intermediate Hosts. Parasitology 1990, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Bernus, A.; Belhassen-García, M.; Carpio-Perez, A.; Perez Del Villar, L.; Romero-Alegria, A.; Velasco-Tirado, V.; Muro, A.; Pardo-Lledias, J.; Cordero-Sánchez, M.; Alonso-Sardón, M. Is Cystic Echinoccocosis Re-Emerging in Western Spain? Epidemiol Infect 2015, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessese, A.T. Review on Epidemiology and Public Health Significance of Hydatidosis. Vet Med Int 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masih, Z.; Hoghooghirad, N.; Madani, R.; Sharbatkhori, M. Expression and Production of Protoscolex Recombinant P29 Protein and Its Serological Evaluation for Diagnosis of Human Hydatidosis. Journal of Parasitic Diseases 2022, 46, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigui, A.; Toumi, N.; Fendri, S.; Saumtally, M.S.; Zribi, I.; Akrout, A.; Mzali, R.; Ketata, S.; Dziri, C.; Amar, M. Ben; et al. Cystic Echinococcosis of the Liver: Correlation Between Intra-Operative Ultrasound and Preoperative Imaging. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2024, 25, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durhan, G.; Tan, A.A.; Düzgün, S.A.; Akkaya, S.; Arıyürek, O.M. Radiological Manifestations of Thoracic Hydatid Cysts: Pulmonary and Extrapulmonary Findings. Insights Imaging 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, T.F.E.; Casulli, A. Morphological Characteristics of Alveolar and Cystic Echinococcosis Lesions in Human Liver and Bone. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babadjanov, A.K.; Yakubov, F.R.; Ruzmatov, P.Y.; Sapaev, D.S. Epidemiological Aspects of Echinococcosis of the Liver and Other Organs in the Republic of Uzbekistan. Parasite Epidemiol Control 2021, 15, e00230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Naz, K.; Ahmed, H.; Simsek, S.; Afzal, M.S.; Haider, W.; Ahmad, S.S.; Farrakh, S.; Weiping, W.; Yayi, G. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Related to Cystic Echinococcosis Endemicity in Pakistan. Infect Dis Poverty 2018, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamarozzi, F.; Legnardi, M.; Fittipaldo, A.; Drigo, M.; Cassini, R. Epidemiological Distribution of Echinococcus Granulosus s.l. Infection in Human and Domestic Animal Hosts in European Mediterranean and Balkan Countries: A Systematic Review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020, 14, e0008519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borhani, M.; Fathi, S.; Lahmar, S.; Ahmed, H.; Abdulhameed, M.F.; Fasihi Harandi, M. Cystic Echinococcosis in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: Neglected and Prevailing! PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020, 14, e0008114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cracu, G.-M.; Schvab, A.; Prefac, Z.; Popescu, M.; Sîrodoev, I. A GIS-Based Assessment of Pedestrian Accessibility to Urban Parks in the City of Constanța, Romania. Applied Geography 2024, 165, 103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrat K, Yahia A, Benaissa MH, C. V Histological Appearance of Echinococcus Granulosus in the Camel Species in Algeria. Bulletin UASVM Veterinary Medicine 2014, 71, 79–44.

- Ciuca, N. Studies on Echinococcosis/Hydatidosis in Men and in Animals TV Constanza County, Romania. Parasitol Int 1998, 47, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobzaru, R.G.; Dumitrescu, A.M.; Ciobotaru, M.; Rîpǎ, C.; Leon, M.; Luca, M.; Iancu, L.S. Epidemiological Aspects of Hydatidosis in Children, in Some Areas of North-Eastern Romania. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi 2013, 117, 754–757. [Google Scholar]

- Mitrea, I.L.; Ionita, M.; Wassermann, M.; Solcan, G.; Romig, T. Cystic Echinococcosis in Romania: An Epidemiological Survey of Livestock Demonstrates the Persistence of Hyperendemicity. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2012, 9, 980–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paduraru, A.A.; Lupu, M.A.; Lighezan, R.; Pavel, R.; Cretu, O.M.; Olariu, T.R. Seroprevalence of Anti-Echinococcus Granulosus Antibodies and Risk Factors for Infection in Blood Donors from Western Romania. Life 2023, 13, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paduraru, A.A.; Lupu, M.A.; Popoiu, C.M.; Stanciulescu, M.C.; Tirnea, L.; Boia, E.S.; Olariu, T.R. Cystic Echinococcosis in Hospitalized Children from Western Romania: A 25-Year Retrospective Study. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paduraru, A.A.; Lupu, M.A.; Sima, L.; Cozma, G.V.; Olariu, S.D.; Chiriac, S.D.; Totolici, B.D.; Pirvu, C.A.; Lazar, F.; Nesiu, A.; et al. Cystic Echinococcosis in Hospitalized Adult Patients from Western Romania: 2007–2022. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.S.; Arrowood, M.; Kokoskin, E.; Paltridge, G.P.; Pillai, D.R.; Procop, G.W.; Ryan, N.; Shimizu, R.Y.; Visvesvara, G. Practical Guidance for Clinical Microbiology Laboratories: Laboratory Diagnosis of Parasites from the Gastrointestinal Tract. Clin Microbiol Rev 2018, 31, e00025–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukarram Shah, S.M. ; Saira; Hussain, F. Molecular Techniques for the Study and Diagnosis of Parasite Infection. In Parasitic Infections; Wiley, 2023; pp. 176–204.

- Moroșan, E.; Dărăban, A.; Popovici, V.; Rusu, A.; Ilie, E.I.; Licu, M.; Karampelas, O.; Lupuliasa, D.; Ozon, E.A.; Maravela, V.M.; et al. Sociodemographic Factors, Behaviors, Motivations, and Attitudes in Food Waste Management of Romanian Households. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streba, L.; Popovici, V.; Mihai, A.; Mititelu, M.; Lupu, C.E.; Matei, M.; Vladu, I.M.; Iovănescu, M.L.; Cioboată, R.; Călărașu, C.; et al. Integrative Approach to Risk Factors in Simple Chronic Obstructive Airway Diseases of the Lung or Associated with Metabolic Syndrome—Analysis and Prediction. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mititelu, M.; Popovici, V.; Neacșu, S.M.; Musuc, A.M.; Busnatu, Ștefan S.; Oprea, E.; Boroghină, S.C.; Mihai, A.; Streba, C.T.; Lupuliasa, D.; et al. Assessment of Dietary and Lifestyle Quality among the Romanian Population in the Post-Pandemic Period. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1006. [CrossRef]

- Cucher, M.A.; Macchiaroli, N.; Baldi, G.; Camicia, F.; Prada, L.; Maldonado, L.; Avila, H.G.; Fox, A.; Gutiérrez, A.; Negro, P.; et al. Cystic Echinococcosis in South America: Systematic Review of Species and Genotypes of Echinococcus Granulosus Sensu Lato in Humans and Natural Domestic Hosts. Tropical Medicine & International Health 2016, 21, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, P.; Menezes da Silva, A.; Akhan, O.; Müllhaupt, B.; Vizcaychipi, K.A.; Budke, C.; Vuitton, D.A. The Echinococcoses. In Advances in Parasitology; 2017; Vol. 96, pp. 259–369.

- Alvi, M.A.; Alsayeqh, A.F. Food-Borne Zoonotic Echinococcosis: A Review with Special Focus on Epidemiology. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Deb Mandal, M. Human Cystic Echinococcosis: Epidemiologic, Zoonotic, Clinical, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Aspects. Asian Pac J Trop Med 2012, 5, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budke, C.M.; Carabin, H.; Ndimubanzi, P.C.; Nguyen, H.; Rainwater, E.; Dickey, M.; Bhattarai, R.; Zeziulin, O.; Qian, M.-B. A Systematic Review of the Literature on Cystic Echinococcosis Frequency Worldwide and Its Associated Clinical Manifestations. The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2013, 88, 1011–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, G.L.; Tanase, I.; Popa, C.A.; Mastalier, B.; Popa, M.I.; Cretu, C.M. Medical and Surgical Management of a Rare and Complicated Case of Multivisceral Hydatidosis; 18 Years of Evolution. New Microbiologica 2014, 37, 387–391. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Y.; Wang, Y.-F.; Wang, J.; Long, S.; Seyler, B.C.; Zhong, X.-F.; Lu, Q. Pictorial Review of Hepatic Echinococcosis: Ultrasound Imaging and Differential Diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol 2024, 30, 4115–4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menschaert, D.; Hoyoux, M.; Moerman, F.; Daron, A.; Frere, J. Echinococcosis, a Global Economic and Health Burden. Tropical Medicine and International Health 2017, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti, E.; Kern, P.; Vuitton, D.A. Expert Consensus for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Cystic and Alveolar Echinococcosis in Humans. Acta Trop 2010, 114, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luga, P.; Gjata, A.; Akshija, I.; Mino, L.; Gjoni, V.; Pilaca, A.; Zobi, M.; Martinez, G.E.; Richter, J. What Do We Know about the Epidemiology and the Management of Human Echinococcosis in Albania? Parasitol Res 2023, 122, 1811–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihailescu, P.E.; Istrate, C.M.; Lazar, V. Echinococcus Species, Neglected Food Borne Parasites: Taxonomy, Life Cycle and Diagnosis. Biointerface Res Appl Chem 2020, 10, 5284–5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Heath Organization Investing to Overcome the Global Impact of Neglected Tropical Diseases ... - World Health Organization - Google Books. Google books 2015, 3.

- da Silva, A.M. Human Echinococcosis: A Neglected Disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2010, 2010, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamarozzi, F.; Akhan, O.; Cretu, C.M.; Vutova, K.; Akinci, D.; Chipeva, R.; Ciftci, T.; Constantin, C.M.; Fabiani, M.; Golemanov, B.; et al. Prevalence of Abdominal Cystic Echinococcosis in Rural Bulgaria, Romania, and Turkey: A Cross-Sectional, Ultrasound-Based, Population Study from the HERACLES Project. Lancet Infect Dis 2018, 18, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmidis, C.S.; Papadopoulos, K.; Mystakidou, C.M.; Sevva, C.; Koulouris, C.; Varsamis, N.; Mantalovas, S.; Lagopoulos, V.; Magra, V.; Theodorou, V.; et al. Giant Echinococcosis of the Liver with Suppuration: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Medicina (B Aires) 2023, 59, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanshahi, F.; Parsaei, A.H.; Naderi, D.; Davani, S.Z.N. Primary Isolated Extraluminal Hydatid Cyst of Left Pulmonary Artery. Int J Surg Case Rep 2023, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewnte, B. Hydatid Cyst of the Foot: A Case Report. J Med Case Rep 2020, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaker, K.; Nouira, Y.; Ouanes, Y.; Bibi, M. A Simple Score for Predicting Urinary Fistula in Patients with Renal Hydatid Cysts. Libyan Journal of Medicine 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jan, Z.U.; Ahmed, N.; Khan, M.Y.; Samin, Y.; Sohail, R. Hydatid Cyst of the Hepatopancreatic Groove - A Case Report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2023, 111, 108771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmady-Nezhad, M.; Rezainasab, R.; Khavandegar, A.; Rashidi, S.; Mohammad-Zadeh, S. Perineal and Right Femoral Hydatid Cyst in a Female with Regional Paresthesia: A Rare Case Report. BMC Surg 2022, 22, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khasawneh, R.A.; Mohaidat, Z.M.; Khasawneh, R.A.; Zoghoul, S.B.; Henawi, Y.M. Unusual Intramuscular Locations as a First Presentation of Hydatid Cyst Disease in Children: A Report of Two Cases. BMC Pediatr 2021, 21, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhdar, F.; Benzagmout, M.; Chakour, K.; Chaoui, M. el faiz Multiple and Infected Cerebral Hydatid Cysts Mimicking Brain Tumor: Unusual Presentation of Hydatid Cyst. Interdisciplinary Neurosurgery 2020, 22, 100802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshering, S.; Dorji, N.; Wangden, T.; Choden, S. Pelvic Hydatid Cyst Mimicking Ovarian Cyst. Journal of South Asian Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2022, 14, 317–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouknani, N.; Kassimi, M.; Saibari, R.C.; Fareh, M.; Mahi, M.; Rami, A. Hydatid Cyst of the Uterus: Very Rare Location. Radiol Case Rep 2023, 18, 882–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakzai, H.A.; Baset, Z.; Ibrahimkhil, A.S.; Rahimi, M.S.; Khan, J.; Hanifi, A.N. Primary Hydatid Cyst of the Urinary Bladder with Associated Eosinophilic Cystitis: Report of a Unique Case. Urol Case Rep 2023, 46, 102296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ismail, I.; Sghaier, M.; Boujmil, K.; Rebii, S.; Zoghlami, A. Hydatid Cyst of the Liver Fistulized into the Inferior Vena Cava. Int J Surg Case Rep 2022, 94, 107060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, M.T.; Hares, R.; Rahman, H.; Shinwari, M.A.; Khaliqi, S.; Hares, S. Primary Cervical Hydatid Cyst: A Rare Case Report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2023, 107, 108349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziri, C.; Haouet, K.; Fingerhut, A.; Zaouche, A. Management of Cystic Echinococcosis Complications and Dissemination: Where Is the Evidence? World J Surg 2009, 33, 1266–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojković, M.; Weber, T.F.; Junghanss, T. Clinical Management of Cystic Echinococcosis: State of the Art and Perspectives. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2018, 31, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiresi, D.A.; Karabacakoglu, A.; Odev, K.; Karakose, S. Pictorial Review. Uncommon Locations of Hydatid Cysts. Acta radiol 2003, 44, 622–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, B.; Akhavan, R.; Ghamari Khameneh, A.; Darban Hosseini Amirkhiz, G.; Rezaei-Dalouei, H.; Tayebi, S.; Hashemi, J.; Aminizadeh, B.; Darban Hosseini Amirkhiz, S. Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Hydatid Disease: A Pictorial Review of Uncommon Imaging Presentations. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindasamy, A.; Bhattarai, P.R.; John, J. Liver Cystic Echinococcosis: A Parasitic Review. Ther Adv Infect Dis 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, V.; Popa, F.; Socea, B.; Carâp, A.; Bǎlǎlǎu, C.; Motofei, I.; Banu, P.; Costea, D. Spontaneous Rupture of a Splenic Hydatid Cyst with Anaphylaxis in a Patient with Multi-Organ Hydatid Disease. Chirurgia (Romania) 2014, 109. [Google Scholar]

- Calu, V.; Enciu, O.; Toma, E.-A.; Pârvuleţu, R.; Pîrîianu, D.C.; Miron, A. Complicated Liver Cystic Echinococcosis—A Comprehensive Literature Review and a Tale of Two Extreme Cases. Tomography 2024, 10, 922–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Infante, S.; Castellón Pavón, C.; Díaz García, G.; Pérez Domene, M.; Durán Poveda, M. Pancreatic Hydatidosis: Unusual Incidental Finding in the Surgical Specimen of a Cephalic Duodenopancreatectomy. Cirugía Andaluza 2023, 34, 468–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arghir, O.; Dantes, E.; Toma, C.; Alexe, M. Bronchoscopic Diagnosis and Complete Treatment of a Ruptured Left Pulmonary Hydatid Cyst. Chest 2012, 142, 880A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado-Aliaga, J.; Romero-Alegría, Á.; Alonso-Sardón, M.; Muro, A.; López-Bernus, A.; Velasco-Tirado, V.; Muñoz Bellido, J.L.; Pardo-Lledias, J.; Belhassen-García, M. Complications Associated with Initial Clinical Presentation of Cystic Echinococcosis: A 20-Year Cohort Analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2019, 101, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramita, A.A.K.Y.; Wibawa, I.D.N. Multimodal Treatment of Cystic Echinococcosis. The Indonesian Journal of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Digestive Endoscopy 2023, 24, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehkordi, A.B.; Sanei, B.; Yousefi, M.; Sharafi, S.M.; Safarnezhad, F.; Jafari, R.; Darani, H.Y. Albendazole and Treatment of Hydatid Cyst, Review of Literature. Infect Disord Drug Targets 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, Y.; Ulas, A.B.; Ince, I.; Kalin, A.; Can, F.K.; Gundogdu, B.; Kasali, K.; Kerget, B.; Ogul, Y.; Eroglu, A. Evaluation of Albendazole Efficiency and Complications in Patients with Pulmonary Hydatid Cyst. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2022, 34, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenman, E.J.L.; Uhart, M.M.; Kusch, A.; Vila, A.R.; Vanstreels, R.E.T.; Mazet, J.A.K.; Briceño, C. Increased Prevalence of Canine Echinococcosis a Decade after the Discontinuation of a Governmental Deworming Program in Tierra Del Fuego, Southern Chile. Zoonoses Public Health 2023, 70, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manouchehr Aghajanzadeh; Afshin Shafaghi; Mohammad Taghi Ashoobi; Mohamad Yosafee Mashhor; Omid Mosaffaee Rad; Mohaya Farzin Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis and Surgical Treatment of Intrabiliary Ruptured Hydatid Disease of the Liver. GSC Advanced Research and Reviews 2023, 16, 162–170. [CrossRef]

- Dogu, D.; Dincer, H.; Turan, T.; Akinci, D.; Parlak, E.; Dogrul, A.B. Diagnosis and Surgical Treatment of Cysto-Gastric Fistula out of an Hepatic Hydatid Cyst. Unusual Case. Ann Ital Chir 2023, 12, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cen, C.; Xie, H.; Zhou, L.; Wen, H.; Zheng, S. The Comparison of 2 New Promising Weapons for the Treatment of Hydatid Cyst Disease. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2015, 25, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Inaebnit, E.; Molina-Romero, F.X.; Segura-Sampedro, J.J.; González-Argenté, X.; Morón Canis, J.M. A Review of the Diagnosis and Management of Liver Hydatid Cyst. Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas 2021, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamarozzi, F.; Nicoletti, G.J.; Neumayr, A.; Brunetti, E. Acceptance of Standardized Ultrasound Classification, Use of Albendazole, and Long-Term Follow-up in Clinical Management of Cystic Echinococcosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2014, 27, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi, S.; Ebrahimian, M.; Mirhashemi, S.H.; Soori, M.; Rashnoo, F.; Oshidari, B.; Shadidi Asil, R.; Zamani, A.; Hajinasrollah, E. A 20 Years Retrospective Descriptive Study of Human Cystic Echinococcosis and the Role of Albendazole Concurrent with Surgical Treatment: 2001-2021. Iran J Parasitol 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Tania Mahar; Abdul Manan; Irfan Ahmad; Abdul Qadir; M. Usman; M. Waseem Cystobiliary Fistula in Hepatic Hydatid Cyst Disease; A Case Report and Literature Review. Medical Journal Of South Punjab 2021, 2. [CrossRef]

- Jafari, R.; Sanei, B.; Baradaran, A.; Kolahdouzan, M.; Bagherpour, B.; Yousofi Darani, H. Immunohistochemical Observation of Local Inflammatory Cell Infiltration in the Host-Tissue Reaction Site of Human Hydatid Cysts. J Helminthol 2019, 93, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sakee, H. Immunological Aspects of Cystic Echinococcosis in Erbil. Zanco J Med Sci 2011, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotz, J.F.; Kaczirek, K.; Stremitzer, S.; Waneck, F.; Auer, H.; Perkmann, T.; Kussmann, M.; Bauer, P.K.; Chen, R.-Y.; Kriz, R.; et al. Evaluation of Eosinophilic Cationic Protein as a Marker of Alveolar and Cystic Echinococcosis. Pathogens 2022, 11, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartar, T.; Bakal, U.; Sarac, M.; Kazez, A. Laboratory Results and Clinical Findings of Children with Hydatid Cyst Disease. Niger J Clin Pract 2020, 23, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lissandrin, R.; Tamarozzi, F.; Piccoli, L.; Tinelli, C.; De Silvestri, A.; Mariconti, M.; Meroni, V.; Genco, F.; Brunetti, E. Factors Influencing the Serological Response in Hepatic Echinococcus Granulosus Infection. The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2016, 94, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotz, J.F.; Peters, L.; Kapp-Schwörer, S.; Theis, F.; Eberhardt, N.; Essig, A.; Grüner, B.; Hagemann, J.B. Evaluation of Serological Markers in Alveolar Echinococcosis Emphasizing the Correlation of PET-CTI Tracer Uptake with RecEm18 and Echinococcus-Specific IgG. Pathogens 2022, 11, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, J.; Nell, J.; Hillenbrand, A.; Henne-Bruns, D.; Schmidberger, J.; Kratzer, W.; Gruener, B.; Graeter, T.; Reinehr, M.; Weber, A.; et al. Immunohistological Detection of Small Particles of Echinococcus Multilocularis and Echinococcus Granulosus in Lymph Nodes Is Associated with Enlarged Lymph Nodes in Alveolar and Cystic Echinococcosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KHABIRI, A.R.; BAGHERI, F.; ASSMAR, M.; SIAVASHI, M.R. Analysis of Specific IgE and IgG Subclass Antibodies for Diagnosis of Echinococcus Granulosus. Parasite Immunol 2006, 28, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, F.; Akhlaghi, L.; Tabatabaie, F. Evaluation of Hydatid Cyst Antigen for Serological Diagnosis. Med J Islam Repub Iran 2023, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Tirado, V.; Alonso-Sardón, M.; Lopez-Bernus, A.; Romero-Alegría, Á.; Burguillo, F.J.; Muro, A.; Carpio-Pérez, A.; Muñoz Bellido, J.L.; Pardo-Lledias, J.; Cordero, M.; et al. Medical Treatment of Cystic Echinococcosis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2018, 18, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, J.; Du, X.; Liu, K.; Wang, C.; Lv, Y.; Wang, M.; Yang, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, S.; Wu, C.; et al. Clinical Characteristics and Antibodies against Echinococcus Granulosus Recombinant Antigen P29 in Patients with Cystic Echinococcosis in China. BMC Infect Dis 2022, 22, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bethony, J.M.; Cole, R.N.; Guo, X.; Kamhawi, S.; Lightowlers, M.W.; Loukas, A.; Petri, W.; Reed, S.; Valenzuela, J.G.; Hotez, P.J. Vaccines to Combat the Neglected Tropical Diseases. Immunol Rev 2011, 239, 237–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Children 2-15 years (average age = 9.84 years) |

Total | Rural residence | Urban residence | p-value | ||||

| Nr | % | Nr | % | Nr | % | |||

| 39.00 | 100.00 | 29.00 | 74.36 | 10.00 | 25.64 | < 0.05 | ||

| Sex | Female | 15.00 | 38.46 | 13.00 | 44.83 | 2.00 | 20.00 | < 0.05 |

| Male | 24.00 | 61.54 | 16.00 | 55.17 | 8.00 | 80.00 | ||

| Animal contact |

No | 11.00 | 28.21 | 5.00 | 17.24 | 6.00 | 60.00 | < 0.05 |

| Yes | 28.00 | 71.79 | 24.00 | 82.76 | 4.00 | 40.00 | ||

| Animal type |

Dog | 5.00 | 17.86 | 1.00 | 4.17 | 4.00 | 100.00 | < 0.05 |

| Goat | 9.00 | 32.14 | 9.00 | 37.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| Pig | 5.00 | 17.86 | 5.00 | 20.83 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| Sheep | 9.00 | 32.14 | 9.00 | 37.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

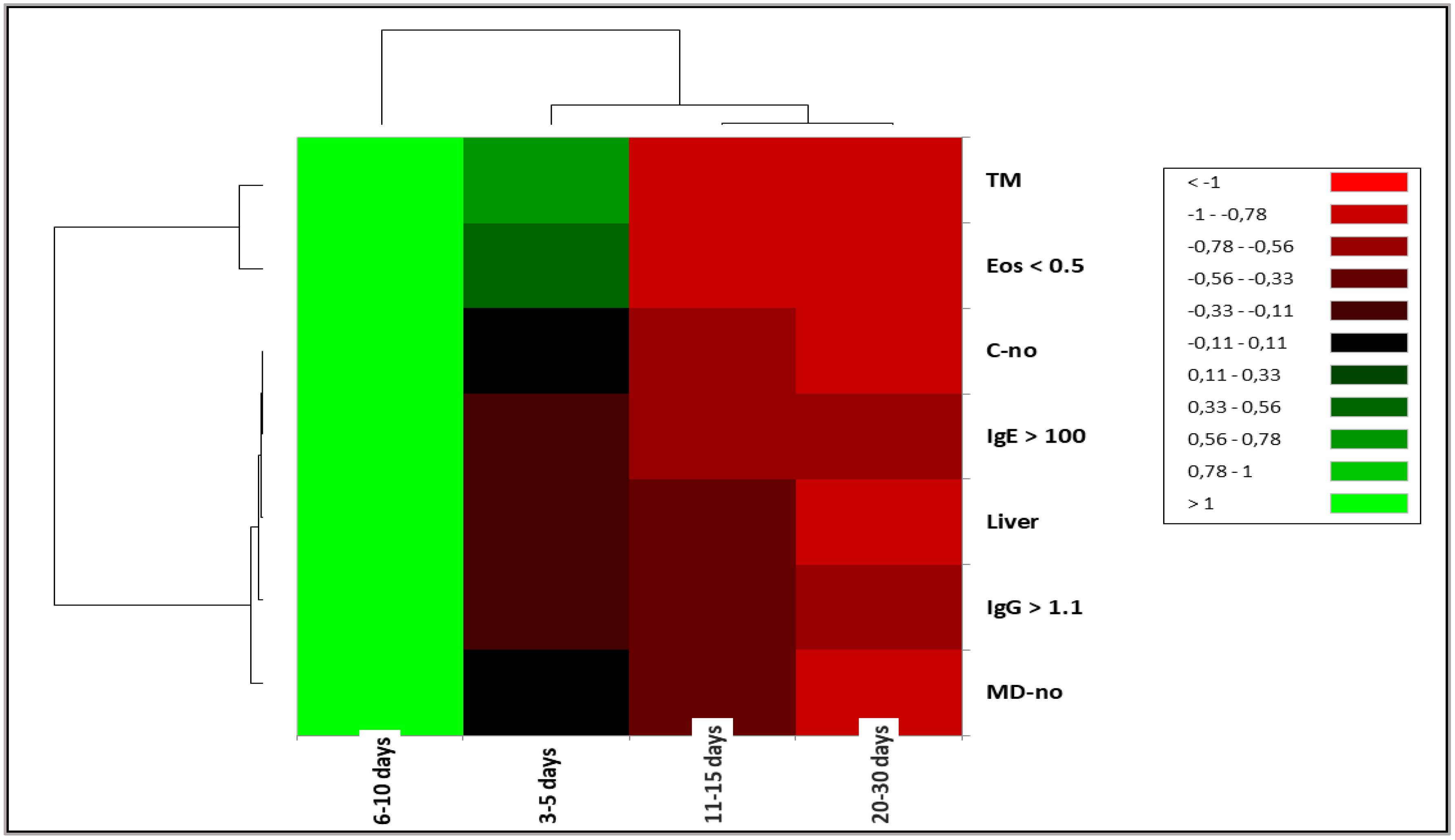

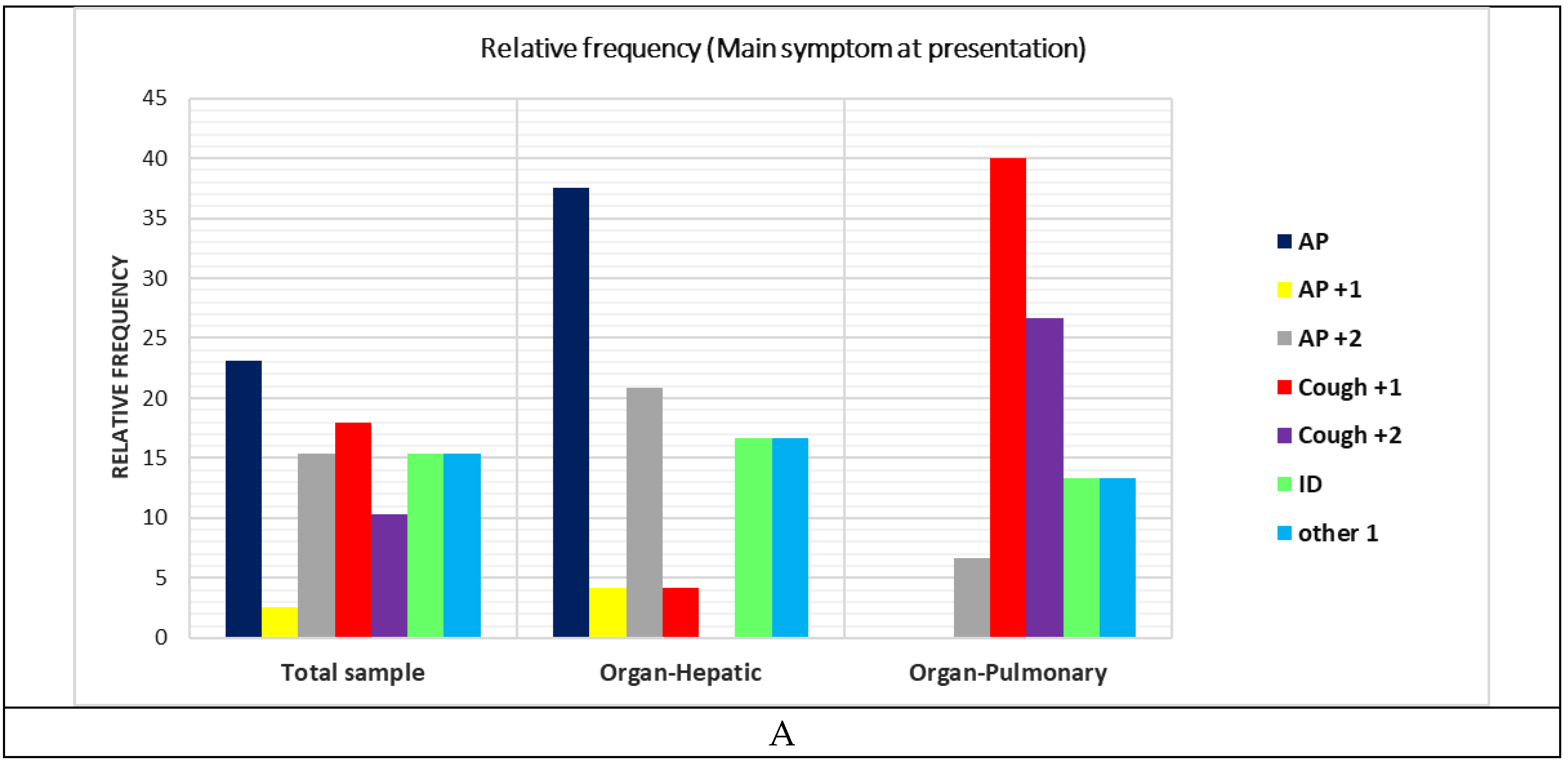

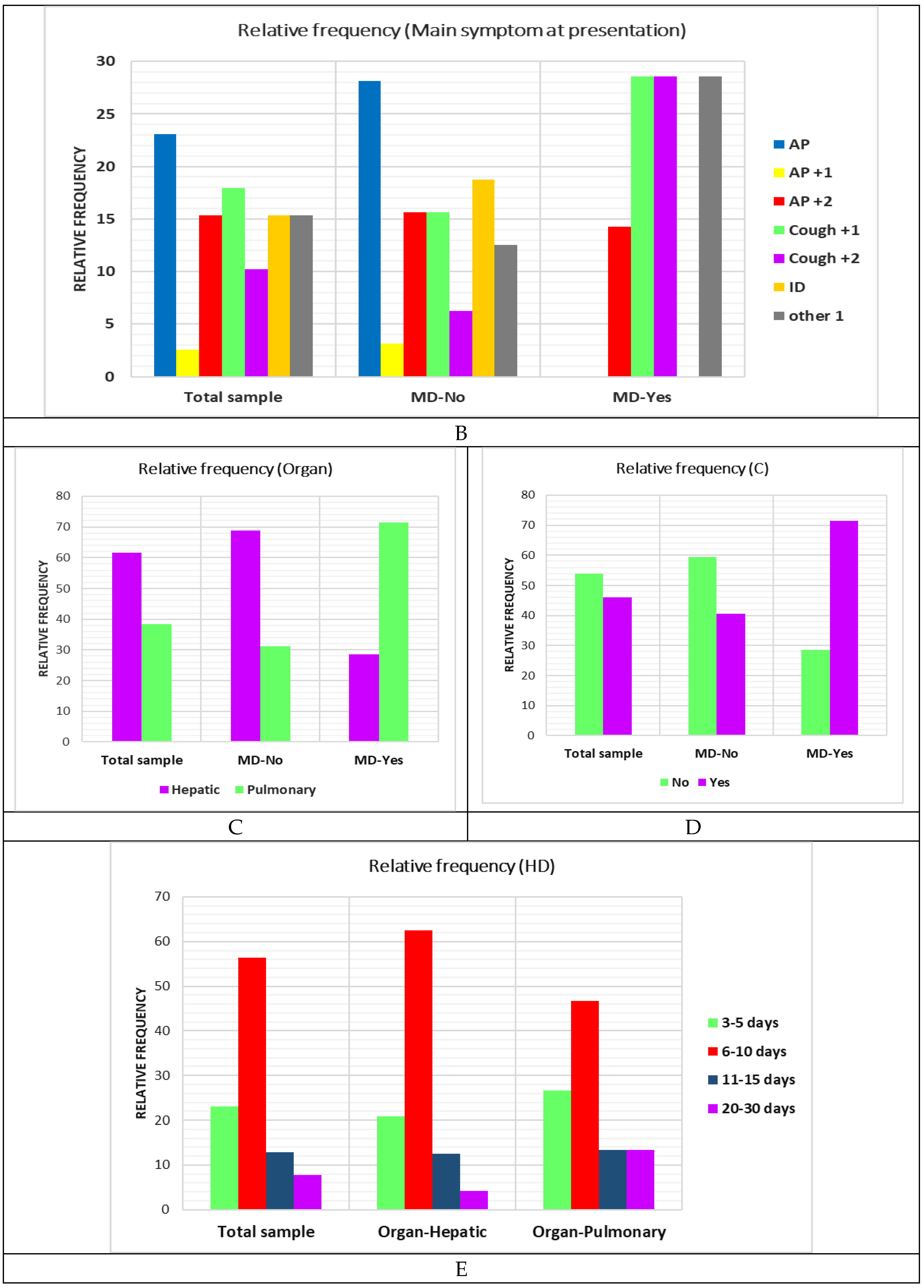

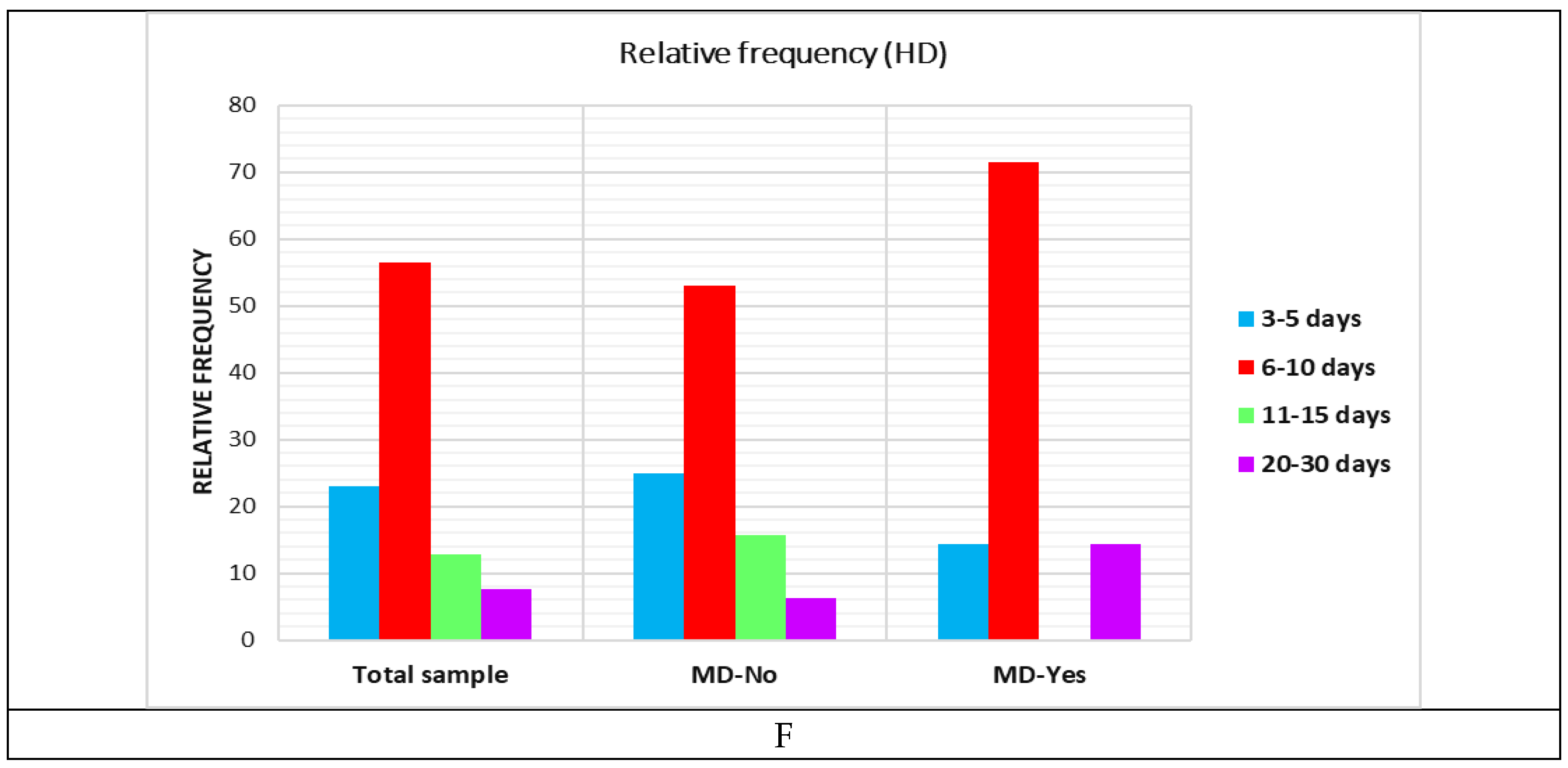

| Aspect | Total | Days of hospitalisation | |||||||||

| 3-5 days | 6-10 days | 11-15 days | 20-30 days | ||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Signs | AP | 9.00 | 23.08 | 3.00 | 33.33 | 5.00 | 22.73 | 1.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| AP+1 | 1.00 | 2.56 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 4.55 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| AP+2 | 6.00 | 15.38 | 1.00 | 11.11 | 5.00 | 22.73 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Cough+1 | 7.00 | 17.95 | 1.00 | 11.11 | 4.00 | 18.18 | 1.00 | 20.00 | 1.00 | 33.33 | |

| Cough+2 | 4.00 | 10.26 | 2.00 | 22.22 | 2.00 | 9.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| ID | 6.00 | 15.38 | 1.00 | 11.11 | 2.00 | 9.09 | 2.00 | 40.00 | 1.00 | 33.33 | |

| Other 1 | 6.00 | 15.38 | 1.00 | 11.11 | 3.00 | 13.64 | 1.00 | 20.00 | 1.00 | 33.33 | |

| Organ | Liver | 24.00 | 61.54 | 5.00 | 55.56 | 15.00 | 68.18 | 3.00 | 60.00 | 1.00 | 33.33 |

| Lung | 15.00 | 38.46 | 4.00 | 44.44 | 7.00 | 31.82 | 2.00 | 40.00 | 2.00 | 66.67 | |

| MD | no | 32.00 | 82.05 | 8.00 | 88.89 | 17.00 | 77.27 | 5.00 | 100.00 | 2.00 | 66.67 |

| yes | 7.00 | 17.95 | 1.00 | 11.11 | 5.00 | 22.73 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 33.33 | |

| C | no | 21.00 | 53.85 | 5.00 | 55.56 | 13.00 | 59.09 | 2.00 | 40.00 | 1.00 | 33.33 |

| yes | 18.00 | 46.15 | 4.00 | 44.44 | 9.00 | 40.91 | 3.00 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 66.67 | |

| Treatment | TM | 11.00 | 28.21 | 5.00 | 55.56 | 6.00 | 27.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| TS | 28.00 | 71.79 | 4.00 | 44.44 | 16.00 | 72.73 | 5.00 | 100.00 | 3.00 | 100.00 | |

| MH | no | 21.00 | 53.85 | 5.00 | 55.56 | 11.00 | 50.00 | 3.00 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 66.67 |

| yes | 18.00 | 46.15 | 4.00 | 44.44 | 11.00 | 50.00 | 2.00 | 40.00 | 1.00 | 33.33 | |

| IgE > 100 | No | 7.00 | 17.95 | 2.00 | 22.22 | 4.00 | 18.18 | 1.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| yes | 32.00 | 82.05 | 7.00 | 77.78 | 18.00 | 81.82 | 4.00 | 80.00 | 3.00 | 100.00 | |

| Eos > 0.5 | No | 26.00 | 66.67 | 8.00 | 88.89 | 12.00 | 54.55 | 3.00 | 60.00 | 3.00 | 100.00 |

| yes | 13.00 | 33.33 | 1.00 | 11.11 | 10.00 | 45.45 | 2.00 | 40.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| IgG > 1.1 | No | 8.00 | 20.51 | 3.00 | 33.33 | 4.00 | 18.18 | 1.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| yes | 31.00 | 79.49 | 6.00 | 66.67 | 18.00 | 81.82 | 4.00 | 80.00 | 3.00 | 100.00 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).