1. Introduction

Cancer is becoming an ever greater health concern as demographic-based predictions indicate that the number of new cases will reach 35 million by 2050 [

1]. Due to the increasing prevalence of cancer and improved survival rates, the number of oncological patients visiting the ED may increase [

2,

3]. Annually, 4 million visits to emergency departments (EDs) and other oncology urgent care centers are generated by patients with advanced-stage cancers [

4]. These data hint at emergency care's important role in end-of-life and palliative care [

5]. Furthermore, approximately 40% of all men and women in the United States will be diagnosed with a malignancy during their lifetime, with the emergency department being an essential site for the care of these patients [

6]. Thus, the role of emergency care in managing these cases is increasing.

Oncological emergencies are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. These can be defined as acute conditions caused by neoplasia or its treatment, which require rapid intervention to avoid complications or death [

7,

8]. Cancer often occurs in the elderly population, which has high levels of comorbidity and frailty that predispose them to treatment complications, making them particularly vulnerable to life-threatening conditions and death [

9,

10]. These patients often develop conditions that require emergent management, such as acute respiratory failure, severe pain, mechanical obstruction due to tumor growth, metabolic disorders, jaundice, hemorrhage, anemia, fever, infection, dehydration, nausea, and vomiting, or various other toxic effects generated by treatments [

8,

11,

12]. Fortunately, many of these emergencies are preventable (especially the metabolic ones) as they often occur following oncological therapy [

13]. An appropriate evaluation is essential for all patients with oncological emergencies. Furthermore, emergency care specialists are frequently the first evaluators of oncological patients before any oncological consult, and their role in patient outcomes is often significant as they address complications associated with the cancer diagnosis [

13,

14].

Given the worldwide increase in the number of patients diagnosed daily with an oncological condition and presenting with emergency symptoms, we proposed conducting a study on oncological emergencies in the Emergency Department of the largest emergency hospital in the northeastern region of Romania. The study's objectives were to evaluate the demographic characteristics of oncological patients, the most frequent types of neoplasm for which emergency medical assistance was sought, and to analyze the short-term outcomes of patients with neoplasm during hospitalization in the emergency department.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective study including patients diagnosed with neoplasms who received emergency medical care at the Emergency Department of “Sf. Spiridon” County Emergency Care Hospital in Iași, Romania, between October 1, 2022, and September 30, 2023. Inclusion criteria were as follows: patients aged 18 years or older, admitted to the Emergency Department during the specified period, with a known diagnosis of neoplasm or a suspected diagnosis based on clinical or paraclinical findings confirmed in the Emergency Department. Data on demographics, oncologic history, and patient care were collected from the emergency department records.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 23 (IBM Corp.). Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables. Inferential statistics, including independent samples t-tests (after Levene's test for homogeneity of variances) and chi-square or Fisher's exact tests (as appropriate), were used to compare means and frequencies between groups. Risk analysis was conducted to assess the association between patient characteristics and specific care needs, with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) reported.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of “St. Spiridon” Emergency Hospital (approval number 114/2024). Given the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent from patients was waived.

3. Results

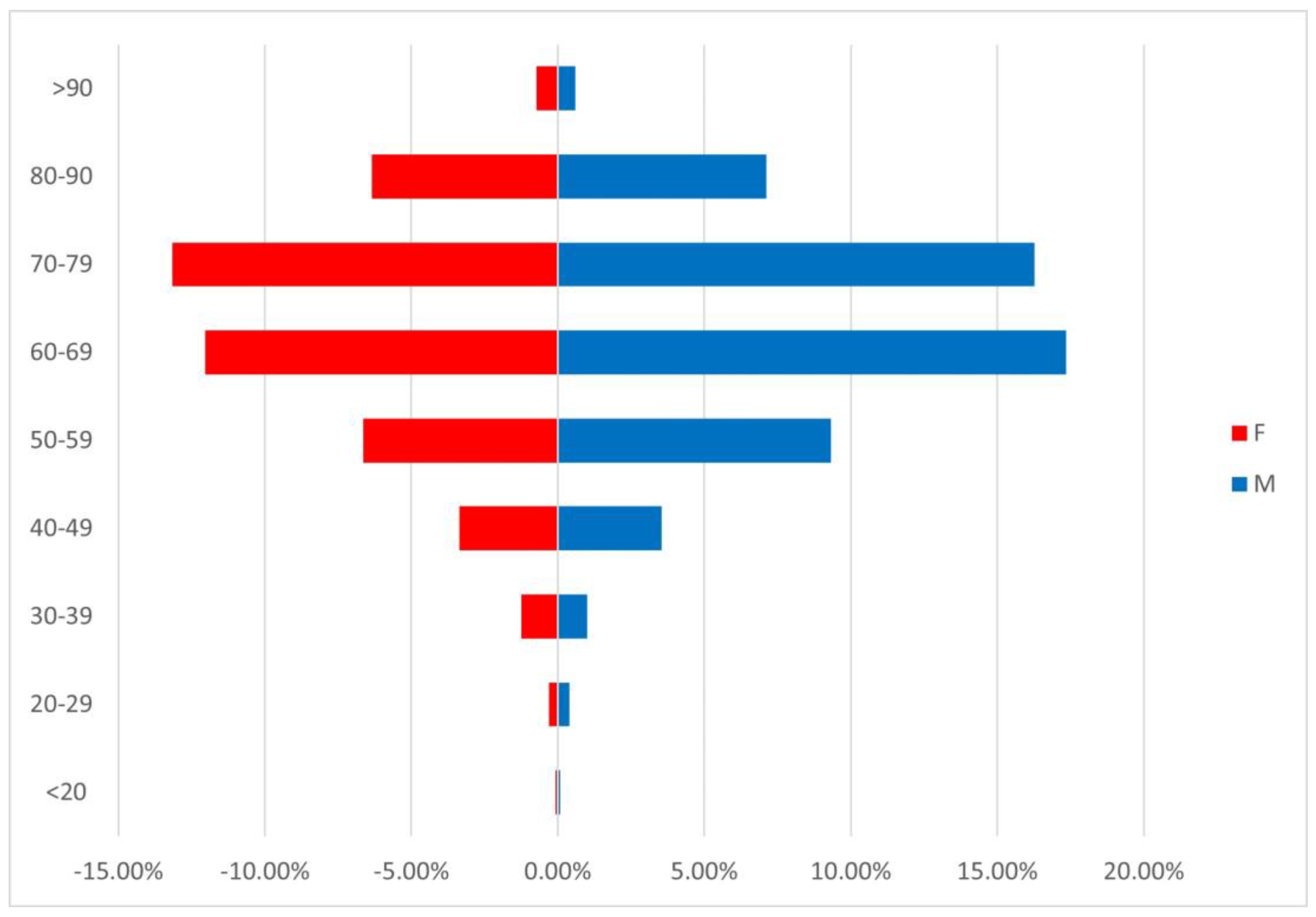

Of the total 81,276 emergency department presentations during the analyzed period, 2510 (3.08%) were for oncological patients. 193 were repeated presentations of the same patients. Therefore, our study included 2318 patients: 1294 men (55.82%) and 1024 women (44.18%). The average age in the study group was 66.43 years, with no statistical difference between genders. The most frequent age group was 70-79 years (29.42%), closely followed by the 60-69 age group (29.38%). Only 3.1% of patients were in the younger age group of 18-39 years (

Figure 1). Among young patients, the most frequent gender was female (1.6% vs 1.42%). Interestingly, older patients had greater odds of needing medical care (OR 1.27, 95% CI: 1.02-1.59, P = 0.04) but were less likely to present repeatedly for emergency care (OR 0.64, 95% CI: 0.46-0.90, P= 0.01).

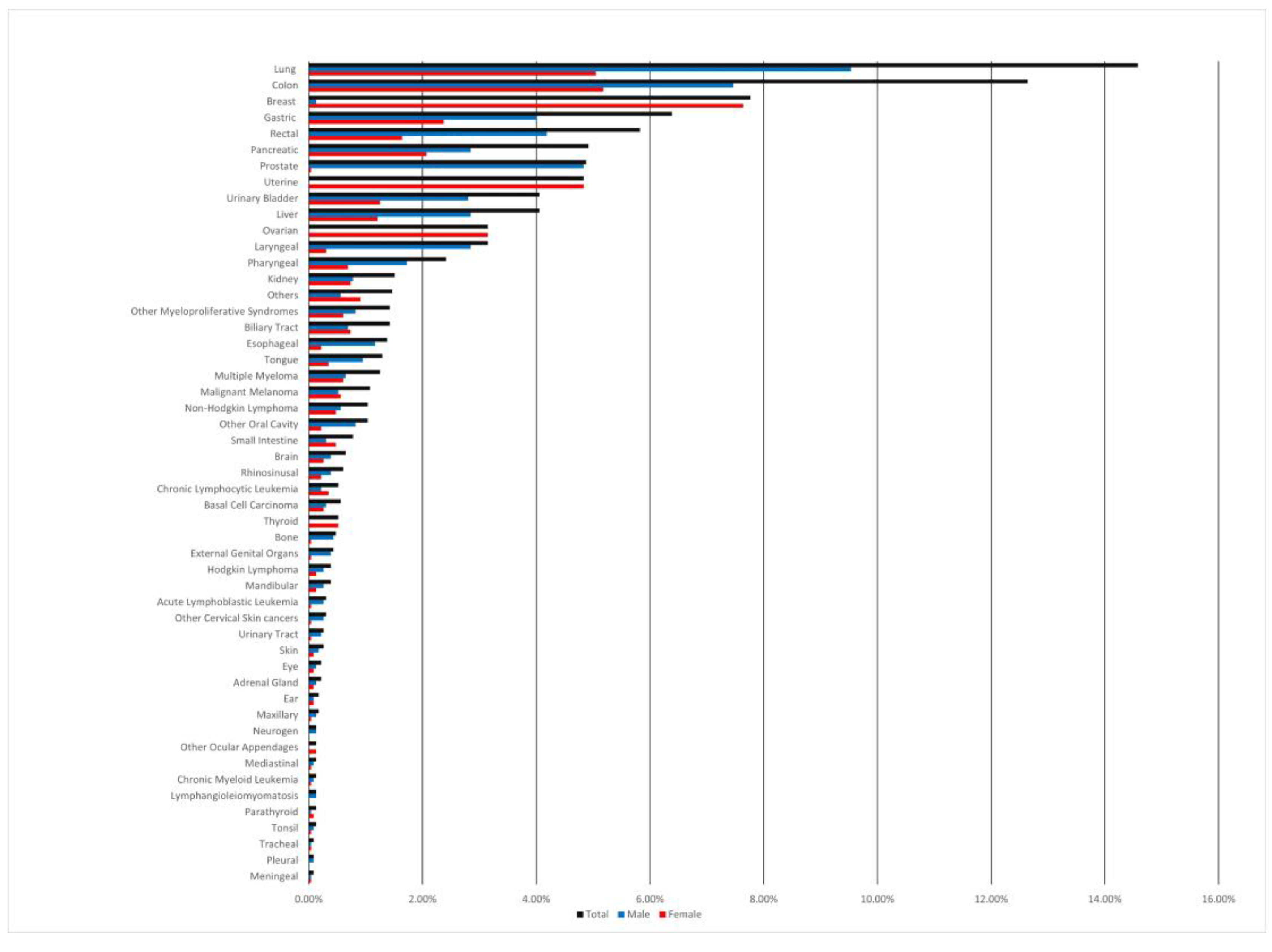

The statistical analysis of cancer types identified the most frequent sites as digestive (40.29%), respiratory (21.05%), and reproductive (21.05%), respectively (

Table 1). The most common cancer types in the analyzed study group were colorectal cancer (18.46%), bronchopulmonary cancer (14.58%), and breast cancer (7.77%) (

Supplementary Figure S1). The most frequent locations for men were the lung, colon, and prostate gland (9.53%, 7.46%, and 4.83%, respectively), while for women, the most frequent locations were breast, colon, and lung (7.64%, 5.18%, and 5.05% respectively).

1874 patients (80.85%) had a previous cancer diagnosis, while 444 patients (19.15%) presented with a high suspicion of neoplasia during their initial emergency department visit, a diagnosis subsequently confirmed by diagnostic tests after a median latency period of 2.5 days. A first diagnosis was associated with gender male (270 vs. 174, P=0.02). There was no statistical difference in age between people with a known diagnosis and a first-time cancer diagnosis (mean age 65.44 vs. 66.34, P=0.86). There was a disparity in cancer type between patients with a known and a first-time diagnosis of cancer (P<0.001). The most common neoplasms diagnosed in this category were lung (3.84%), colon (2.55%), and gastric (1.86%), respectively (

Figure 2). Risk analysis detailed in

Table 2 shows that patients with a de novo cancer diagnosis were more likely to be admitted to the ward, require a specialty consultation, or need any form of medical care (OR 2.09, 95% CI: 1.70-2.59, P < 0.001; OR 3.28, 95% CI: 2.48-4.35, P < 0.001; OR 2.65, 95% CI: 2.12-3.32, P < 0.001, respectively). Consequently, these cases were less likely to be discharged home without further care (OR 0.33, 95% CI: 0.25-0.44, P < 0.001). However, they were less severe, as none required intensive care, and were less likely to need intubation (OR 0.36, 95% CI: 0.14-0.89, P = 0.02).

Risk analysis also shows that men were more likely to be diagnosed with cancer for the first time and be transferred to other local hospitals for further care (OR 1.29, 95% CI: 1.04-1.59, P = 0.02, and OR 1.21, 95% CI: 1.02-1.44, P = 0.03, respectively), while women were more likely to present repeatedly to the ER (OR 1.40, 95% CI: 1.01-1.94, P = 0.05). Men also presented more often to the ER for respiratory (OR 2.14, 95% CI: 1.72-2.64, P < 0.001), digestive (OR 1.72, 95% CI: 1.45-2.04, P < 0.001), or urinary system neoplasia (OR 1.52, 95% CI: 1.05-2.18, P = 0.03), while women were more likely to have reproductive (OR 5.21, 95% CI: 4.15-6.54, P < 0.001) and endocrine system cancer (OR 5.13, 95% CI: 1.71-15.38, P < 0.001), respectively (

Table 2).

A total of 193 patients (6.64%) had multiple ED visits, averaging 2.27 (±0.75) vis-its, with no statistically significant difference between genders. Patients who had more than one emergency room visit had significantly higher odds of being discharged without any other consult or specialty care (OR 2.85, 95% CI: 2.05-3.97; p < 0.001), being referred to different hospitals for evaluation (OR 1.95, 95% CI: 1.40-2.71; p < 0.001), or being withheld for observation for more than 24 hours (OR 2.66, 95% CI: 1.01-7.00; with marginal statistical significance, p = 0.057).

In-hospital mortality within the emergency department was low for cancer patients, at 0.95%. Most were monitored and treated in the emergency department, then admitted to relevant clinical wards or discharged home with therapeutic recommendations. The odds of mortality in the de novo diagnosis group were slightly elevated (OR-1.01, 95% CI 1.01-1.02, p = 0.01). (

Table 3)

Finally, 26.57% (616) of patients had end-stage cancer, with the most frequent locations of metastasis being liver metastases, lung metastases, and lymph node metastases. First cancer diagnosis and end-stage disease did not overlap as most patients did not have metastasis when the emergent care occurred (OR-0.42, 95% CI:0.32-0.56; P < 0.001). Patients with stage IV cancer had, on average, more days of observation (0.86 vs 0.13 days, p < 0.001) and a higher number of ER visits (1.13 vs 1.06, p < 0.001). These patients had higher odds of having a repeated ER visit (OR 1.85, 95% CI: 1.32-2.59, p = 0.001) and a more severe condition (requiring monitoring, transfer to another hospital, intensive care, intubation, or mortality).

Figure 1.

Age distribution among emergency patients with a cancer diagnostic. M-male; F-Female.

Figure 1.

Age distribution among emergency patients with a cancer diagnostic. M-male; F-Female.

Figure 2.

Cancer type distribution among first-time diagnosed patients.

Figure 2.

Cancer type distribution among first-time diagnosed patients.

Supplementary Figure 1.

Emergency patient's cancer diagnosis distribution.

Supplementary Figure 1.

Emergency patient's cancer diagnosis distribution.

Table 1.

Case summary and gender correlation.

Table 1.

Case summary and gender correlation.

| Variable |

Total |

Gender |

Significance |

| Male |

Female |

| Age mean(±SD) |

66.43(±12.93) |

66.38(±12.41) |

66.50(±13.57) |

0.82 |

| Neoplasia |

|

|

|

|

| Respiratory |

488(21.05%) |

341(14.71%) |

147(6.34%) |

<0.001 |

| Digestive |

934(40.29%) |

595(25.67%) |

339(14.62%) |

<0.001 |

| Reproductive |

488(21.05%) |

124(5.35%) |

364(15.70%) |

<0.001 |

| Urinary |

135(5.82%) |

88(3.80%) |

47(2.03%) |

0.02 |

| Hematologic |

125(5.39%) |

72(3.11%) |

53(2.29%) |

0.68 |

| Skin |

51(2.20%) |

29(1.25%) |

22(0.95%) |

0.88 |

| Endocrine |

20(0.86%) |

4(0.17%) |

16(0.69%) |

0.001 |

| Neuro-sensorial |

32(1.38%) |

18(0.78%) |

14(0.60%) |

0.96 |

| Musculo-scheletal |

11(0.47%) |

10(0.43%) |

1(0.04%) |

0.02 |

| Others |

34(1.47%) |

13(0.56%) |

21(0.91%) |

0.04 |

| First Diagnosis n(%) |

444(19.15%) |

270(11.65%) |

174(7.51%) |

0.02 |

| Stage IV neoplasia |

616(26.57%) |

332(14.32%) |

284(12.25%) |

0.26 |

| Repeated visits |

154(6.64%) |

74(3.19%) |

80(3.45%) |

0.04 |

| Home Discharge |

737(31.79%) |

399(17.21%) |

338(14.58%) |

0.26 |

| >24h monitoring |

32(1.38%) |

17(0.73%) |

15(0.65%) |

0.76 |

| Hospital admission |

754(32.53%) |

431(18.59%) |

323(13.93%) |

0.37 |

| Other county hospital transfer |

10(0.43%) |

5(0.22%) |

5(0.22%) |

0.71 |

| Local Hospital Transfer |

784(33.82%) |

462(19.93%) |

322(13.89%) |

0.03 |

| Specialty consult |

1587(68.46%) |

899(38.78%) |

688(29.68%) |

0.24 |

| Medical care |

529(22.82%) |

295(12.73%) |

234(10.09%) |

0.98 |

| Surgery |

227(9.79%) |

138(5.95%) |

89(3.84%) |

0.11 |

| Intensive care |

8(0.35%) |

4(0.17%) |

4(0.17%) |

0.74 |

| Intubation |

63(2.72%) |

37(1.60%) |

26(1.12%) |

0.64 |

| Mortality |

22(0.95%) |

16(0.69%) |

6(0.26%) |

0.11 |

| Total |

2318(100%) |

1294(55.82%) |

1024(44.18%) |

|

Table 2.

Risk analysis for emergency care and gender (male).

Table 2.

Risk analysis for emergency care and gender (male).

| |

Gender (Male) OR(95%CI) |

P |

| First Diagnosis |

1.29(1.04-1.59) |

0.02 |

| Repeated ED visits |

0.72(0.52-0.99) |

0.05 |

| Stage IV neoplasia |

0.90(0.75-1.08) |

0.28 |

| >24h monitoring |

0.90(0.45-1.80) |

0.86 |

| Intubation |

1.13(0.68-1.88) |

0.70 |

| Hospital admission |

1.08(0.91-1.29) |

0.37 |

| Other county hospital transfer |

0.79(0.23-2.74) |

0.76 |

| Home Discharge |

0.91(0.76-1.08) |

0.28 |

| Specialty consult |

1.11(0.93-1.33) |

0.24 |

| Local Hospital Transfer |

1.21(1.02-1.44) |

0.03 |

| Need of Surgery |

1.25(0.95-1.66) |

0.12 |

| Medical care |

1.00(0.82-1.21) |

1 |

| Intensive care |

0.79(0.20-3.17) |

0.74 |

| Mortality |

2.12(0.83-5.45) |

0.13 |

| ED- Emergency department; |

|

Table 3.

Risk analysis for cancer stage, moment of diagnosis, and need for emergency healthcare.

Table 3.

Risk analysis for cancer stage, moment of diagnosis, and need for emergency healthcare.

| |

Stage IV cancer |

First cancer diagnoses |

| OR(95% CI) |

P |

OR(95% CI) |

P |

| Repeated ED visits |

1.85(1.32-2.59) |

0.001 |

0.73(0.46-1.15) |

0.20 |

| Home Discharge |

0.93(0.76-1.14) |

0.51 |

0.33(0.25-0.44) |

<0.001 |

| >24h monitoring |

4.14(2.03-8.42) |

<0.001 |

0.28(0.07-1.17) |

0.07 |

| Hospital admission |

0.94(0.77-1.14) |

0.55 |

2.09(1.70-2.59) |

<0.001 |

| Other county hospital transfer |

1.19(0.31-4.60) |

0.73 |

1.81(0.47-7.04) |

0.42 |

| Local Hospital Transfer |

1.27(1.05-1.54) |

0.02 |

1.04(0.83-1.29) |

0.78 |

| Specialty consult |

1.06(0.87-1.29) |

0.61 |

3.28(2.48-4.35) |

<0.001 |

| Need of Surgery |

1.04(0.77-1.42) |

0.81 |

0.78(0.54-1.13) |

0.21 |

| Medical care |

0.87(0.70-1.09) |

0.24 |

2.65(2.12-3.32) |

<0.001 |

| Intensive care |

4.63(1.10-19.45) |

0.04 |

- |

- |

| Intubation |

2.59(1.57-4.28) |

<0.001 |

0.36(0.14-0.89) |

0.02 |

| Mortality |

4.06(1.73-9.54) |

0.001 |

1.01(1.01-1.02) |

0.01 |

4. Discussion

The emergency department plays an important role in providing medical care for oncological patients and in the diagnosis of cancer. Several situations can be highlighted in which the role of care is crucial: (1) the neoplasm is diagnosed incidentally while the patient is being investigated for unrelated conditions that led them to seek medical assistance (such as vehicle collisions, domestic accidents); (2) acute manifestations of neoplastic disease, known or unknown, requiring emergency care; (3) pathway used by patients without medical insurance or those who request medical care before their scheduled appointment with the attending oncologist (as an entry point for hospital admission).

Cancer patients may present to the ED at any stage of the cancer survivorship continuum: at diagnosis, during treatment, post-treatment, or at the end of life [

15]. We found that 19.15% of patients presented with a de novo cancer diagnostic, and 26.57% were end-stage cancers. Expectedly, end-stage patients were more severe and had increased odds of needing intensive care treatment (OR-4.63, P=0.04), while first-time diagnosed patients required further assessment in a specialty department and were more often admitted to a ward. Studies also show that cancer patients who seek medical assistance in the ED, compared to those who receive a diagnosis in other settings, have higher comorbidity, present with more advanced-stage cancers, and have a poorer prognosis [

16]. A non-negligible amount of our study patients were diagnosed with cancer for the first time during their ED visit, aligning with specialized literature indicating that 12-32% of cancer diagnoses occur in the ED [

15]. Based on our findings, these de novo cases were usually not severe and were more likely to need specialty consults and be admitted to a ward. A recent article by Hong et al. found that self-referred cancer patients to the ED did not need admission to a specialty ward, following emergency department visits more than patients referred by doctors [

17]. This emphasizes the increasing role that emergency care plays in cancer diagnosis. Diagnosing cancer in the ED, whether incidental or due to specific symptomatology, is becoming an increasingly important method. Thus, emergency specialists face significant adversities in managing these cases and could benefit from multidisciplinary assessments, such as in situ oncological consultations and palliative care assessments.

Our study found that 3.08% of all ED presentations during the analyzed period were oncological patients. While this percentage may seem insignificant, it represents a substantial number of visits to Emergency Departments already overwhelmed by various ailments. These percentages are comparable to the proportion of visits due to other conditions such as congestive heart failure (4%), chronic kidney disease (3.5%), cerebrovascular diseases, including stroke (3.7%), and widespread chronic conditions like diabetes (6%) [

18]. A recent study on a large national database (NEDS) on emergency room presentation with cancer in the United States for the interval 2006-2012 found a presentation rate of 4.2% [

19]. The study also shows that cancer patients were more likely to have an ER visit within the first year of diagnosis and have repeated visits. The difference in the observed rate of cancer presentations is most likely population-specific, and because of the time period assessed, novel therapeutic interventions and quality of care have since significantly improved patient outcomes [

20]. A previous assessment by Cimpoesu et al. of the same issue in our emergency department for the assessed period of June 2009 and May 2010 revealed that oncological patients accounted for 3.26% of total presentations [

21]. Although this presentation rate is similar, and only a slight reduction can be observed, in our assessment, we reported this rate to the 81,276 presentations while they reported this rate to the 40,322 presentations within that period, with only 1315 cases of emergencies for oncologic patients. There has been a significant increase in ED overcrowding, which is projected to be an upward trend [

22]. As the prevalence of neoplasia increases, more and more patients will request emergent aid. Comparatively, our study further shows a reduction in the presentation rate of end-stage cases, as the survey above reported up to 67.07% of patients having metastasis, while their observed de novo case rate was similar (23.12%). The constant rate of de novo cases diagnosed in the ED is concerning and raises questions about screening programs' efficiency in preventing emergent care needs for cancer patients. These findings highlight that requesting emergency healthcare is sometimes unavoidable for oncological patients. The observed rates can help project healthcare needs and resource utilization for this patient population. Thus, further studies are needed to identify these needs and provide evidence of improved care and patient outcomes in the emergency department.

The distribution of cases according to histology in our study overlaps with the global cancer epidemiology for each gender [

20]. Our study found a high rate of addressability for patients with lung, breast, and colorectal cancers. This aligns with previous research that found similar distribution by cancer type [

19,

23]. Because these statistics largely reflect the prevalence of surviving patients diagnosed with cancer and may not account for patient-specific information, it is difficult to affirm that specific cancers require more emergent care. Efforts have been made, though, to identify factors influencing emergency care needs (like comorbidity, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy), such as in the case of patients with colorectal cancers [

24]. The symptoms prompting ED visits may be directly cancer-related, or the diagnosis may be incidental. In either case, it's challenging to determine if these ED presentations could have been avoided through different triage codes or improved primary care/cancer screening access. Understanding how cancer patients present to the ED for diagnosis is crucial for improving their care and follow-up. The relationship between increased ED-diagnosed cancers and limited access to primary care or cancer screening remains unclear [

16]. Regarding first-time diagnosed patients, we found a significant difference in cancer localization distribution (p<0.001). The largest proportion of these cases was still diagnosed with lung, colon, and gastric cancers (20.05%, 13.29%, and 9.68%, respectively). The reduced rates of reproductive de novo cancer highlight the important impact populational screening programs have at a national level. Romania does not have a functional Lung cancer screening program set up yet, which might explain these rates.

The elderly age group constitutes the majority of ED presentations for cancer in our research [

25]. This is due mainly to the demographic distribution of cancer that affects particularly the older population [

25]. It is known that cancer disproportionately affects the elderly population and that this population is at risk for unfavorable outcomes. These cases are challenging because of their increased comorbidity and associated geriatric syndromes like frailty [

10]. New cases diagnosed in the ED aren't different in age distribution from patients with a new diagnosis (p-0.68). Thus, elderly patients could benefit from a multidisciplinary assessment containing a geriatric evaluation to fine-tune their care in the context of emergency care.

Literature shows that a large proportion of cancer patients have multiple ED vis-its [

15,

23,

24]. A California population-based study reported that 20% of patients with cancer had one ED visit, 8% had two visits, and 7% had three or more visits within 180 days of diagnosis [

23]. In our one-year retrospective cohort study, 6.64% of patients had multiple ED visits, averaging 2.27(±0.75). End-stage patients were more likely to present repeatedly to the ED, while these repeated cases were less likely to be admitted to a ward and receive any further specialty assessment. Studies show that patients with cancer are more likely to be admitted to a progressive care or intensive care unit (11%) compared to the general population (2%) [

15]. Between 34% and 49% are discharged home, and approximately 4–5% of the remaining patients are transferred to another facility, die during the ED visits, or leave before physician evaluation or against medical advice [

24]. The vast majority of patients included in our study were monitored and treated urgently, and then they were hospitalized in specialized clinical departments (32.53%) or could go home with therapeutic recommendations (31.79%). The low hospitalization rate highlights the importance of ambulatory palliative care and its potential to decrease ED overload.

Finally, the mortality rate of patients in the emergency department was minimal (0.95%), with the most common cancer diagnostics being lung cancer (0.17%). Surprisingly, there was a slight increase in the odds of mortality for first-time cancer diagnosis patients (OR-1.01, P=0.01). This means that patients without a previously known diagnosis are more vulnerable and could suffer more severe unfortunate outcomes. Yet, this does not consider variables like disease and patient characteristics that could significantly influence this result.

Our study is a follow-up study on cancer epidemiology within the largest county hospital in Iasi that focuses specifically on patients with a novel cancer diagnosis following emergency care. The generated data was used to assess the correlation between cancer diagnosis and care needs in the emergency department. This study's findings are limited by its retrospective design. This was a single-center study; thus, it could not assess the repeated visits patients could have had in other emergency departments in the county. Furthermore, the university hospital receives severe cases more often, limiting the generalizability of our findings.

5. Conclusions

The role of the Emergency Department in evaluating and treating cancer patients is often underemphasized. Our study demonstrates that a significant proportion of patients receive their initial cancer diagnosis following emergency care. Implementing national screening programs could further reduce the cancer diagnosis burden in emergency care. These findings highlight the importance of a multidisciplinary approach, including close collaboration with oncologists and palliative care specialists, to ensure the best possible outcomes. Furthermore, we show the importance of well-coordinated end-of-life care in reducing emergency department overcrowding and assert the importance of ambulatory palliative care services.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study design and conceptualization.M.C-A., R-A.I., and V.P. wrote the original draft, and A.H., P.L.N., G.G., M.P., R.E.C., and A-I.S. performed further review and editing. C.C.D. supervised the research. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of “St. Spiridon” Emergency Hospital (approval number 114/2024) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Given the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent from patients was waived.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; and Jemal, A. "Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries," CA Cancer J Clin, 2024, 74(3), 229-263. [CrossRef]

- Workina, A.; Habtamu, A.; Zewdie, W. "Reasons for Emergency Department Visit, Outcomes, and Associated Factors of Oncologic Patients at Emergency Department of Jimma University Medical Centre," Open Access Emerg Med, 2022, 14, 581-590. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Ro, Y.S.; Shin, S.D.; Moon, S. "Epidemiologic trends in cancer-related emergency department utilization in Korea from 2015 to 2019," Sci Rep, 2021, 11(1), 21981. [CrossRef]

- Gould Rothberg, B.E.; Quest, T.E.; Yeung, S.J.; Pelosof, L.C.; Gerber, D.E.; Seltzer, J.A.; Bischof, J.J.; Thomas, C.R.; Akhter, N.; Mamtani, M.; Stutman, R.E.; Baugh, C.W.; Anantharaman, V.; Pettit, N.R.; Klotz, A.D.; Gibbs, M.A.; Kyriacou, D.N. "Oncologic emergencies and urgencies: A comprehensive review," CA Cancer J Clin, 2022, 72(6), 570-593. [CrossRef]

- Long, D.A.; Koyfman, A.; Long, B. "Oncologic Emergencies: Palliative Care in the Emergency Department Setting," J Emerg Med, 2021, 60(2), 175-191. [CrossRef]

- Dormagen, J.B.; Verma, N.; Fink, K.R. "Imaging in Oncologic Emergencies," Semin Roentgenol, 2020, 55(2), 95-114. [CrossRef]

- Brigden, M.L "Hematologic and oncologic emergencies. Doing the most good in the least time," Postgrad Med, 2001, 109(3),143-157. [CrossRef]

- Spring, J; Munshi, L. "Oncologic Emergencies: Traditional and Contemporary," Crit Care Clin, 2021, 37(1), 85-103.

- Miller, K.D.; Nogueira, L.; Devasia, T.; Mariotto, A.B.; Yabroff, K.R.; Jemal, A.; Kramer, J.; Siegel, R.L. "Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2022," CA Cancer J Clin, 2022, 72(5), 409-436. [CrossRef]

- Ethun, C.G.; Bilen, M.A.; Jani, A.B.; Maithel, S.K.; Ogan, K.; Master, V.A. "Frailty and cancer: Implications for oncology surgery, medical oncology, and radiation oncology," CA Cancer J Clin, 2017, 67(5), 362-377.

- Brydges, N.; Brydges, G.J. "Oncologic Emergencies," AACN Adv Crit Care, 2021, 32(3), 306-314. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.; Donnelly, J.P.; Moore, J.X.; Meneses, K.; Williams, G.; Wang, H.E. "National characteristics of Emergency Department visits by patients with cancer in the United States," Am J Emerg Med, 2018, 36(11), 2038-2043. [CrossRef]

- Yeung, S.-C.J; Escalante, C.P. Oncologic Emergencies, in Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine, 1-21.

- Jean-Baptiste, E. "Clinical assessment and management of massive hemoptysis," Crit Care Med, 2000, 28(5), 1642-77. [CrossRef]

- Lash, R.S.; Hong, A.S.; Bell, J.F.; Reed, S.C.; Pettit, N. "Recognizing the emergency department's role in oncologic care: a review of the literature on unplanned acute care," Emerg Cancer Care, 2022, 1(1), 6ew of the literature on unplanned acute care," Emerg Cancer Care, 2022, 1(1), 6. [CrossRef]

- Wattana, M.K.; Lindsay, A.; Davenport, M.; Pettit, N.R.; Menendez, J.R.; Li, Z.; Lipe, D.N.; Qdaisat, A.; Bischof, J.J. "Current gaps in emergency medicine core content education for oncologic emergencies: A targeted needs assessment," AEM Educ Train, 2024, 8(3), e10987. [CrossRef]

- Hong, A.S.; Chang, H.; Courtney, D.M.; Fullington, H.; Lee, S.J.C.; Sweetenham, J.W.; Halm, E.A. "Patterns and Results of Triage Advice Before Emergency Department Visits Made by Patients With Cancer," JCO Oncol Pract, 2021, 17(4), e564-e574. [CrossRef]

- Cairns, C.; Kang, K.; Santo, L. "National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2018 Emergency Department Summary Tables," 2018, Access Date: 18.11.2024; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2018-ed-web-tables-508.pdf.

- Rivera, D.R.; Gallicchio, L.; Brown, J.; Liu, B.; Kyriacou, D.N.; Shelburne, N. "Trends in Adult Cancer-Related Emergency Department Utilization: An Analysis of Data From the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample," JAMA Oncol, 2017, 3(10), e172450. [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. "Cancer statistics, 2022," CA Cancer J Clin, 2022, 72(1), 7-33. [CrossRef]

- Cimpoesu, D.; Dumea, M.; Durchi, S.; Apostoae, F.; Olaru, G.; Ciolan, M.; Popa, O.; Corlade-Andrei, M. "Urgente oncologice in Departamentul de Urgenta," The Medical-Surgical Journal, 2011, 114(4), 1073-1079.

- Maninchedda, M.; Proia, A.S.; Bianco, L.; Aromatario, M.; Orsi, G.B.; Napoli, C. "Main Features and Control Strategies to Reduce Overcrowding in Emergency Departments: A Systematic Review of the Literature," Risk Manag Healthc Policy, 2023, 16, 255-266. [CrossRef]

- Lash, R.S.; Bell, J.F.; Bold, R.J.; Joseph, J.G.; Cress, R.D.; Wun, T.; Brunson, A.M.; Romano, P.S. "Emergency department use by recently diagnosed cancer patients in California," J Community Support Oncol, 2017, 15(2), 95-102. [CrossRef]

- Weidner, T.K.; Kidwell, J.T.; Etzioni, D.A.; Sangaralingham, L.R.; Van Houten, H.K.; Asante, D.; Jeffery, M.M.; Shah, N.; Wasif, N. "Factors Associated with Emergency Department Utilization and Admission in Patients with Colorectal Cancer," J Gastrointest Surg, 2018, 22(5), 913-920. [CrossRef]

- Guida, J.L.; Ahles, T.A.; Belsky, D.; Campisi, J.; Cohen, H.J.; DeGregori, J.; Fuldner, R.; Ferrucci, L.; Gallicchio, L.; Gavrilov, L.; Gavrilova, N.; Green, P.A.; Jhappan, C.; Kohanski, R.; Krull, K.; Mandelblatt, J.; Ness, K.K.; O'Mara, A.; Price, N.; Schrack, J.; Studenski, S.; Theou, O.; Tracy, R.P.; Hurria, A. "Measuring Aging and Identifying Aging Phenotypes in Cancer Survivors," J Natl Cancer Inst, 2019, 111(12), 1245-1254. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).