Submitted:

25 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment of Study Participants and Design of the Study

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Analyses of Blood Samples

2.4. DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Two Groups Based on Changes in Uric Acid Levels After Consuming HPect Smoothie

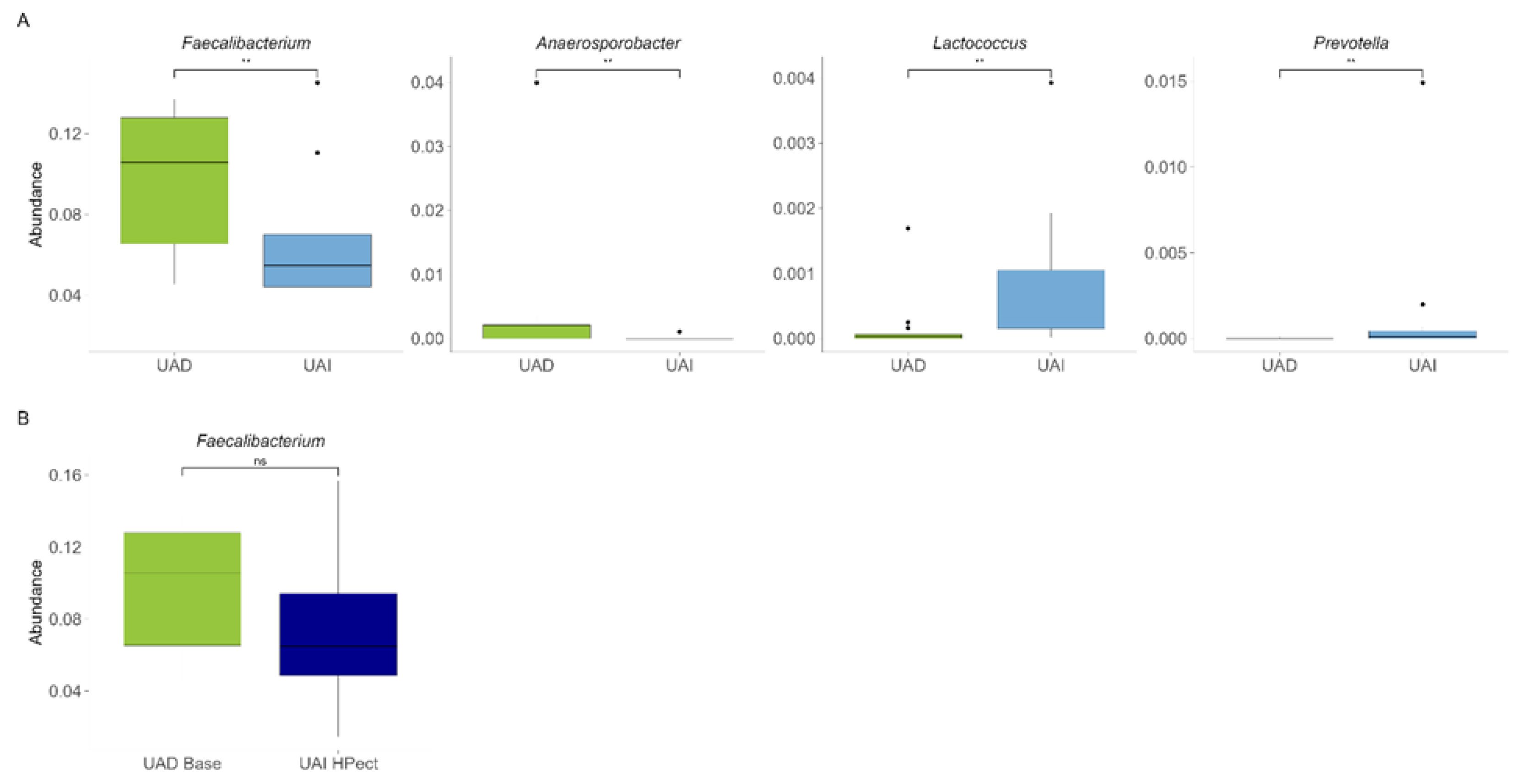

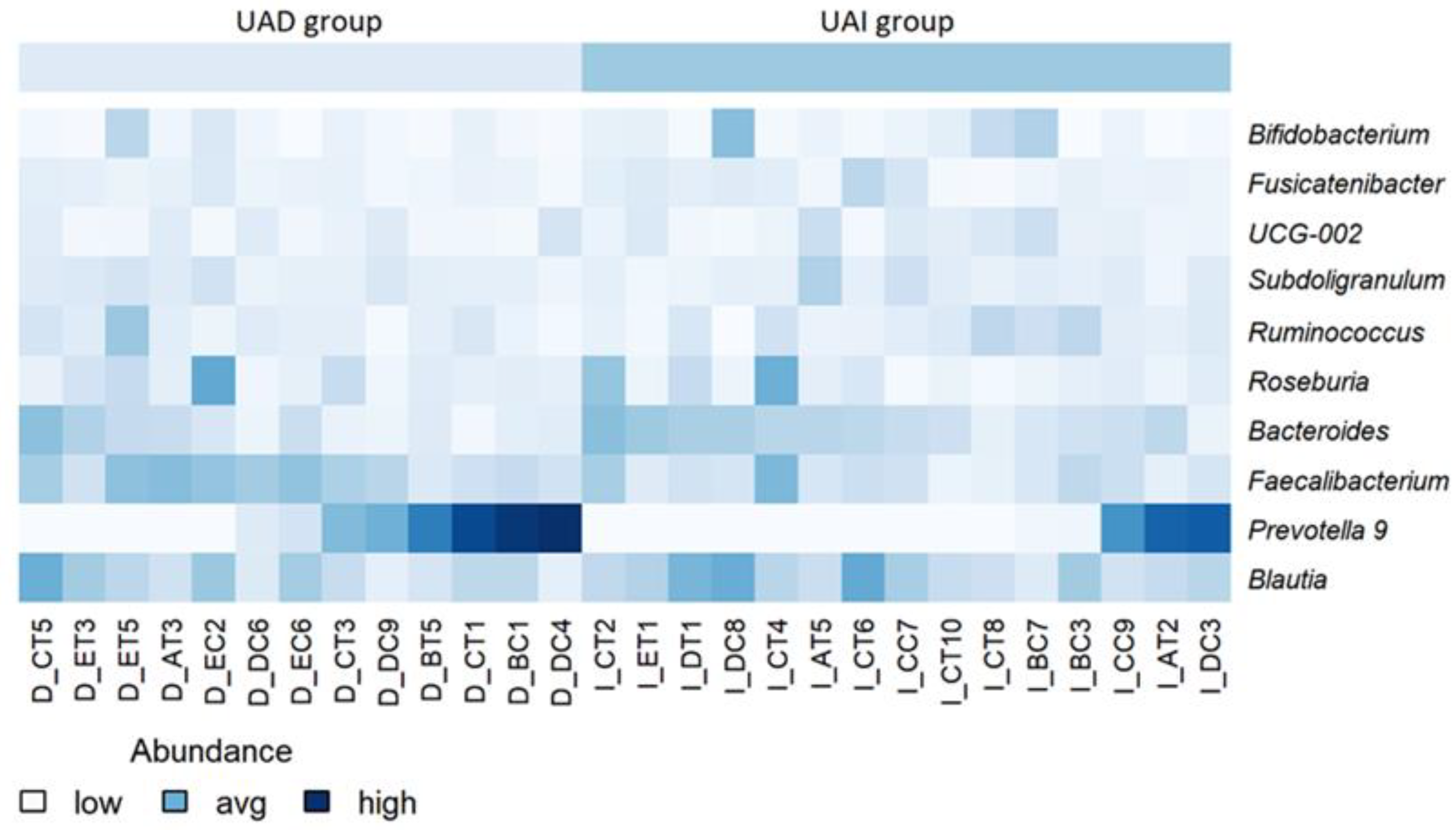

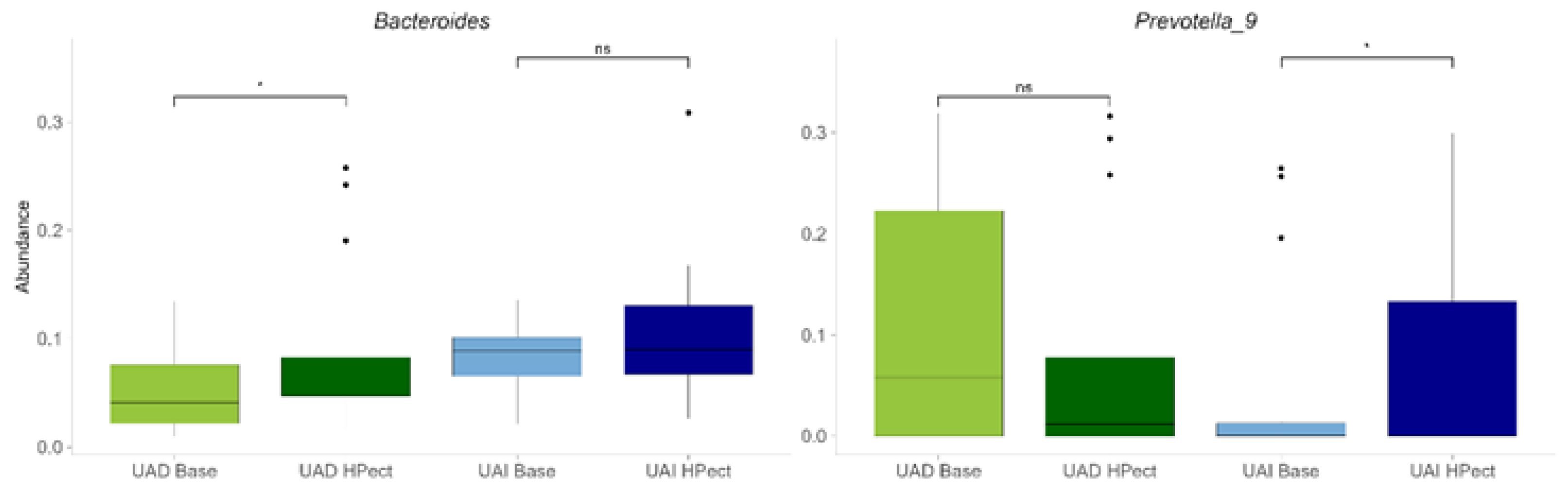

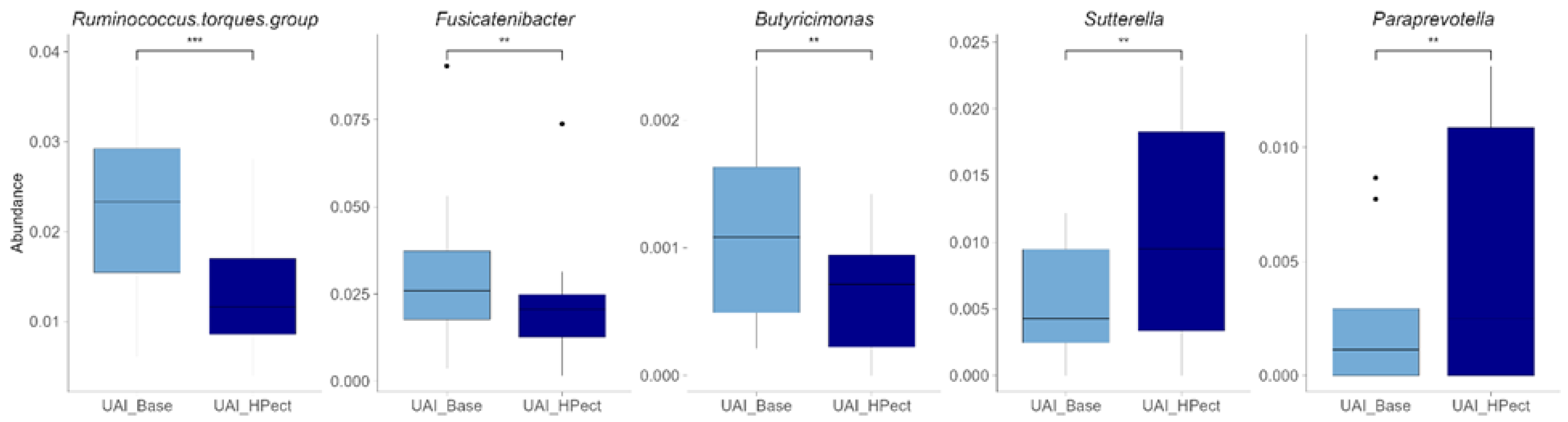

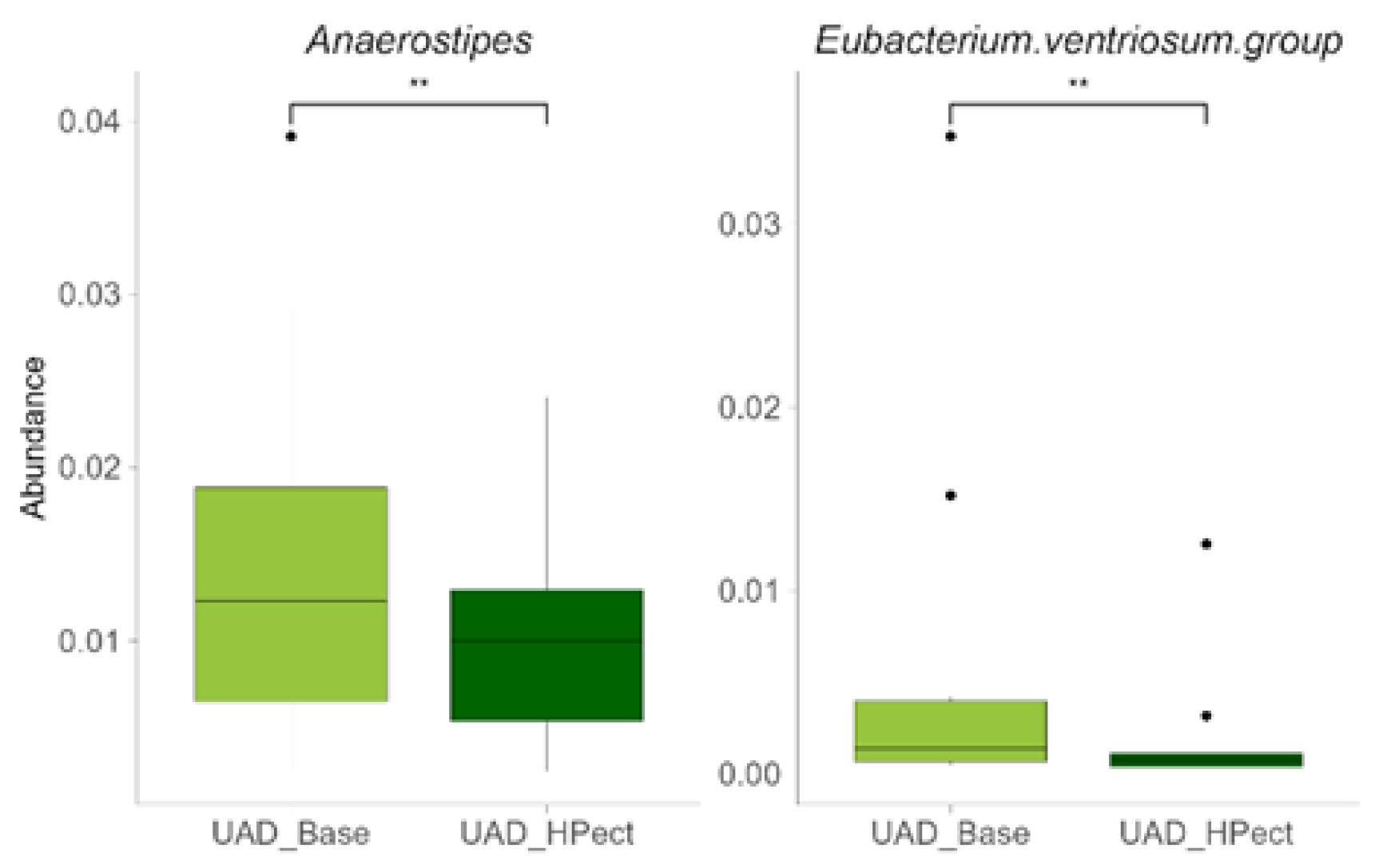

3.2. The High-Pectin Smoothie Affects Uric Acid Levels and Gut Microbiota Differently in the UAI and UAD Groups

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- T. Bardin and P. Richette, “Definition of hyperuricemia and gouty conditions,” Curr. Opin. Rheumatol., vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 186–191, 2014. [CrossRef]

- V. L. H. Kuhns and O. M. Woodward, “Molecular Sciences Sex Differences in Urate Handling,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 21, no. Figure 1, pp. 1–20, 2020, [Online]. Available: www.mdpi.com/journal/ijms.

- T. Zuo, X. Liu, L. Jiang, S. Mao, X. Yin, and L. Guo, “Hyperuricemia and coronary heart disease mortality: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies,” BMC Cardiovasc. Disord., vol. 16, no. 1, 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. I. Fang, J. S. Wu, Y. C. Yang, R. H. Wang, F. H. Lu, and C. J. Chang, “High uric acid level associated with increased arterial stiffness in apparently healthy women,” Atherosclerosis, vol. 236, no. 2, pp. 389–393, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. Miyajima et al., “Prediction and causal inference of hyperuricemia using gut microbiota,” Sci. Rep., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1–9, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Mao, Q. He, J. Yang, L. Jia, and G. Xu, “Relationship between gout, hyperuricemia, and obesity—does central obesity play a significant role?—a study based on the NHANES database,” Diabetol. Metab. Syndr., vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 1–12, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Kurajoh et al., “Uric acid shown to contribute to increased oxidative stress level independent of xanthine oxidoreductase activity in MedCity21 health examination registry,” Sci. Rep., vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1–9, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Yamada et al., “Evaluation of purine utilization by Lactobacillus gasseri strains with potential to decrease the absorption of food-derived purines in the human intestine,” Nucleosides, Nucleotides and Nucleic Acids, vol. 35, no. 10–12, pp. 670–676, 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. A. Martínez-Nava et al., “The impact of short-chain fatty acid–producing bacteria of the gut microbiota in hyperuricemia and gout diagnosis,” Clin. Rheumatol., vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 203–214, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Yin, N. Liu, and J. Chen, “The Role of the Intestine in the Development of Hyperuricemia,” vol. 13, no. February, pp. 1–8, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Y. Lim, M. Rho, Y. Song, K. Lee, J. Sung, and G. Ko, “Stability of Gut Enterotypes in Korean Monozygotic Twins and Their Association with Biomarkers and Diet,” pp. 1–7, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chu et al., “Metagenomic analysis revealed the potential role of gut microbiome in gout,” npj Biofilms Microbiomes, vol. 7, no. 1, 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Valeri and K. Endres, “How biological sex of the host shapes its gut microbiota,” Front. Neuroendocrinol., vol. 61, p. 100912, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Beisner, A. Gonzalez-granda, M. Basrai, and A. Damms-machado, “Fructose-Induced Intestinal Microbiota Shift,” Nutrients, vol. 12, pp. 1–21, 2020.

- Z. Wang, Y. Li, W. Liao, and J. Huang, “Gut microbiota remodeling : A promising therapeutic strategy to confront hyperuricemia and gout,” no. August, pp. 1–18, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. P. Juraschek, C. Yokose, N. McCormick, E. R. Miller, L. J. Appel, and H. K. Choi, “Effects of Dietary Patterns on Serum Urate: Results From a Randomized Trial of the Effects of Diet on Hypertension,” Arthritis Rheumatol., vol. 73, no. 6, pp. 1014–1020, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Pihelgas, K. Ehala-Aleksejev, R. Kuldjärv, A. Jõeleht, J. Kazantseva, and K. Adamberg, “Short-term pectin-enriched smoothie consumption has beneficial effects on the gut microbiota of low-fiber consumers,” FEMS Microbes, no. February, pp. 1–10, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Beukema, M. M. Faas, and P. de Vos, “The effects of different dietary fiber pectin structures on the gastrointestinal immune barrier: impact via gut microbiota and direct effects on immune cells,” Exp. Mol. Med., vol. 52, no. 9, pp. 1364–1376, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. G. Caporaso et al., “Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 108, no. SUPPL. 1, pp. 4516–4522, 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. Kazantseva, E. Malv, A. Kaleda, A. Kallastu, and A. Meikas, “Optimisation of sample storage and DNA extraction for human gut microbiota studies,” BMC Microbiol., vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 1–13, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. E. McDonald et al., “Characterising the canine oral microbiome by direct sequencing of reverse-transcribed rRNA molecules,” PLoS One, vol. 11, no. 6, pp. 1–17, 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. Pitsi et al., Eesti toitumis- ja liikumissoovitused 2015. Tervise Arengu Instituut, 2017.

- Kallion Kaja, Ühendlabori analüüside käsiraamat. .

- H. W. Kim, E. J. Yoon, S. H. Jeong, and M. C. Park, “Distinct Gut Microbiota in Patients with Asymptomatic Hyperuricemia: A Potential Protector against Gout Development,” Yonsei Med. J., vol. 63, no. 3, pp. 241–251, 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Engel, F. Hoffmann, M. H. Freitag, and H. Jacobs, “Should we be more aware of gender aspects in hyperuricemia? Analysis of the population-based German health interview and examination survey for adults (DEGS1),” Maturitas, vol. 153, no. June, pp. 33–40, 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Zi, A. Fisc, L. Karl, C. Hans, and G. Nage, “Sex- and age-specific variations , temporal trends and metabolic determinants of serum uric acid concentrations in a large population-based Austrian cohort,” pp. 1–8, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Gaffo, D. R. Jacobs, F. Sijtsma, C. E. Lewis, T. R. Mikuls, and K. G. Saag, “Serum urate association with hypertension in young adults: Analysis from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults cohort,” Ann. Rheum. Dis., vol. 72, no. 8, pp. 1321–1327, 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. Li, K. Yu, and C. Li, “Dietary factors and risk of gout and hyperuricemia: A meta-analysis and systematic review,” Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr., vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 1344–1356, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Johnson et al., “The fructose survival hypothesis for obesity,” Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci., vol. 378, no. 1885, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tero-Vescan, R. Ștefănescu, T. I. Istrate, and A. Pușcaș, “Fructose-induced hyperuricaemia–protection factor or oxidative stress promoter?,” Nat. Prod. Res., vol. 0, no. 0, pp. 1–13, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Liang et al., “Diagnostic model for predicting hyperuricemia based on alterations of the gut microbiome in individuals with different serum uric acid levels,” Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne)., vol. 13, no. September, pp. 1–13, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Koguchi et al., “Suppressive Effect of Viscous Dietary Fiber on Elevations of Uric Acid in Serum and Urine Induced by Dietary RNA in Rats is Associated with Strength of Viscosity,” Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res., vol. 73, no. 5, pp. 369–376, 2003. [CrossRef]

- T. Koguchi and T. Tadokoro, “Beneficial Effect of Dietary Fiber on Hyperuricemia in Rats and Humans: A Review,” Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res., vol. 89, no. 1–2, pp. 89–108, 2019. [CrossRef]

- W. S. F. Chung et al., “Modulation of the human gut microbiota by dietary fibres occurs at the species level,” BMC Biol., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1–13, 2016. [CrossRef]

- N. Larsen et al., “Potential of pectins to beneficially modulate the gut microbiota depends on their structural properties,” Front. Microbiol., vol. 10, no. FEB, pp. 1–13, 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Pascale, F. Gu, N. Larsen, L. Jespersen, and F. Respondek, “The Potential of Pectins to Modulate the Human Gut Microbiota Evaluated by In Vitro Fermentation: A Systematic Review,” Nutrients, vol. 14, no. 17, pp. 1–31, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. K. Yeoh et al., “Prevotella species in the human gut is primarily comprised of Prevotella copri, Prevotella stercorea and related lineages,” Sci. Rep., vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–9, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Martín et al., “Faecalibacterium: a bacterial genus with promising human health applications,” FEMS Microbiol. Rev., vol. 47, no. 4, pp. 1–18, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Larsen, “The immune response to Prevotella bacteria in chronic inflammatory disease,” Immunology, vol. 151, no. 4, pp. 363–374, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Takahashi, K. Nakagawa, W. Nagata, A. Koizumi, and T. Ishizuka, “A preliminary therapeutic study of the effects of molecular hydrogen on intestinal dysbiosis and small intestinal injury in high-fat diet-loaded senescence-accelerated mice,” Nutrition, vol. 122, 2024. [CrossRef]

| UAD group (n=13) | UAI group (n=15) | |

|---|---|---|

| Energy (kcal/day) | 1888.8 (±497.0) | 1809.7 (±561.1) |

| Fiber (g/day) | 23.9 (±8.4) | 24.2 (±10.9) |

| Carbohydrates (g/day)/(%) | 218.4 (±57.1)/46.0 | 210.8 (±66.4)/44.7 |

| Fat (g/day) /(%) | 81.2 (±31.9)/38.0 | 77.0 (±35.3)/37.3 |

| Protein (g/day) /(%) | 74.8 (±27.1)/16.0 | 79.4 (±35.9)/18.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).