1. Introduction

Vishing, a portmanteau of “Voice” and “Phishing”, has evolved with advancements in technology, allowing attackers to employ additional phishing channels such as web, Short Message Service (SMS), and email for more sophisticated scams [

1]. These techniques continue to result in annual losses amounting to millions of dollars for both individuals and organizations [

2,

3]. The emergence of attacks utilizing vishing applications has significantly escalated the fraud landscape; leveraging these applications has been shown to incur losses up to ten times greater than those caused by traditional phishing campaigns that do not utilize such apps [

4].

With the proliferation of vishing applications, the most commonly observed attack methods are the Call Redirection Attack and the Display Overlay Attack [

4]. Firstly, the Call Redirection Attack involves redirecting the number dialed by the user to the attacker’s phone number. However, since the attacker’s phone number would appear on the user’s outgoing call screen, this method is often combined with a Display Overlay Attack for added deception. The Display Overlay Attack, on the other hand, is used to conceal the attacker’s phone number by overlaying a fake waiting screen during incoming or outgoing calls [

5]. By masking the real phone number with a counterfeit screen, users are less likely to notice discrepancies, thereby increasing the likelihood of them divulging personal information without suspicion. Additionally, we defined a new attack, Duplicated Contacts Attack. This attack involves registering the attacker’s phone number under a contact name that matches a target contact’s name or editing an existing contact on the target’s device to insert the attacker’s phone number.

In previous research, due to the lack of clearly defined vishing attack techniques, researchers explored various dimensions of vishing and investigated user behavior in response to these threats. Based on these studies, research was conducted to enhance users’ security awareness, focusing on enabling individuals to recognize and respond to phishing attempts. These include user studies analyzing why individuals respond (or do not respond) to vishing attempts [

6], research aimed at increasing awareness of mobile scams through education [

7], and detailed crime reports explaining how attackers succeed in their fraudulent schemes [

8]. However, the emergence of vishing applications has introduced new attack vectors, such as call redirection and display overlay attacks, leaving gaps in the existing body of research. To fill these gaps an approach involving modifications to the Android Operating System (OS) was proposed, which monitors specific Application Programming Interfaces (API) to detect malicious behaviors [

4]. However, this method requires users to directly alter the Android OS, which poses a significant barrier to adoption. Additionally, it is limited to monitoring specific APIs used in malicious techniques. If Google introduces new APIs with similar functionalities, this approach may fail to detect them. There has also been research utilizing Large Language Models (LLMs) to assist victims in responding to vishing attempts. However, these approaches face challenges due to limited training data, which can introduce biases and reduce the reliability of the results [

9].

In this work, Ventinel focuses on monitoring the user’s screen to defend against Display Overlay Attack and Call Redirection Attack. When an incoming call is detected, Ventinel uses Optical Character Recognition (OCR) to compare the number displayed on the user’s screen with the incoming number to detect the Display Overlay Attack. Additionally, when an outgoing call is initiated, Ventinel compares the number dialed by the user with the number that successfully connects, which allows it to detect the Call Redirection Attack. Then, through OCR, Ventinel checks for the Display Overlay Attack that could be used alongside Call Redirection Attack by comparing the number displayed on the screen with the number dialed by the user. Finally, Ventinel examines the user’s contacts and cross-references the phone numbers stored in the recent call log and SMS records to identify unused contacts, thereby defending against Duplicated Contacts Attacks. Ventinel stores the identified phone numbers in the blacklist and, after confirming the user’s intention to delete them, proceeds with deleting the contacts. In the process, Ventinel does not collect or store unnecessary data and only accesses the minimum data needed to monitor duplicate contacts by asking for explicit permission from the user.

This method emphasizes pre-incident detection and operates entirely within the Android application, ensuring user convenience. Furthermore, even if the APIs used to execute the same malicious actions are changed, the Ventinel remains capable of detection. Ventinel demonstrated a 100% detection rate for Display Overlay, Call Redirection, and Duplicated Contacts, achieving higher scores compared to commercial apps available on the Android Play Store. Additionally, we conducted a user study using a benchmark that we developed, which revealed that, when using Ventinel, only approximately 8.9% of users responded on average.

We present the following contributions:

We analyze APIs provided in Android level 29 and above that exhibit behaviors similar to malicious activities.

We identify and highlight the limitations of currently available commercial vishing defense applications.

We examine existing attack techniques used by vishing applications and propose novel attack methods.

We implement a defense mechanism within an application to counteract vishing attacks, specifically focusing on Display Overlay Attack, Call Redirection Attack, and the newly defined Duplicated Contacts Attack, all without requiring OS modifications.

2. Background

In this section, we introduce the malicious behaviors found in vishing applications and the Android APIs that enable the creation of these behaviors. We also explain how vishing applications may use Android APIs differently depending on the Android API level. Furthermore, we discuss known vishing defense approaches and their limitations.

2.1. Malicious Behavior in Vishing Apps

Vishing, a combination of “Phishing” and “Voice”, refers to a type of mobile cyber crime that uses voice calls to financially exploit victims [

10,

11]. Attackers lure victims into installing vishing applications and subsequently impersonate public institutions or acquaintances through these applications. Consequently, victims may be misled by insidious fraud and inadvertently provide sensitive information, potentially leading to financial harm [

12]. The malicious behaviors identified in the vishing applications we examined are as follows:

Call Redirection. Android provides APIs for Call Redirection, enabling developers to create applications that cancel outgoing calls and automatically connect to a different phone number. Therefore, attackers can develop vishing applications to cancel a victim’s requested outgoing call and redirect it to a attacker. To implement Call Redirection, attacker employ different APIs based on the target Android API level. We detail different Android APIs corresponding APIs levels in

Section 2.2. Additionally, vishing applications may combine Display Overlay with Call Redirection to disguise the redirected outgoing number.

Display Overlay. Android supports APIs that facilitate the output of specific pop-up screens or full-screen displays, known as Display Overlay [

13,

14]. Vishing applications can exploit this APIs to perform malicious activities by using Display Overlay to cover the victim’s device screen with a fake interface, thereby deceiving the victim about the outgoing caller ID. Specifically, when vishing applications change the outgoing call, they overlay a fake screen to disguise the altered outgoing number display. When victims receive a call from attackers, vishing applications overlay a screen that appears to be from a legitimate institution (e.g., police, bank, public institution) to deceive the victim.

Duplicated Contacts. Android provides APIs that allow developers to retrieve, and modify contacts stored on a device. Vishing applications may exploit these APIs to exfiltrate or modify contacts on a victim’s device for malicious purposes. Additionally, we introduce a malicious behavior called

Duplicated Contacts. Duplicated Contacts involves adding the attacker’s number to the victim’s contact list under an existing contact name or editing it as a secondary contact. According to a FINLEY, Jason R., et al [

15], many smartphone users store contacts on their devices rather than memorizing phone numbers, making Duplicated Contacts effective in tricking victims into thinking they are receiving a call from someone they know.

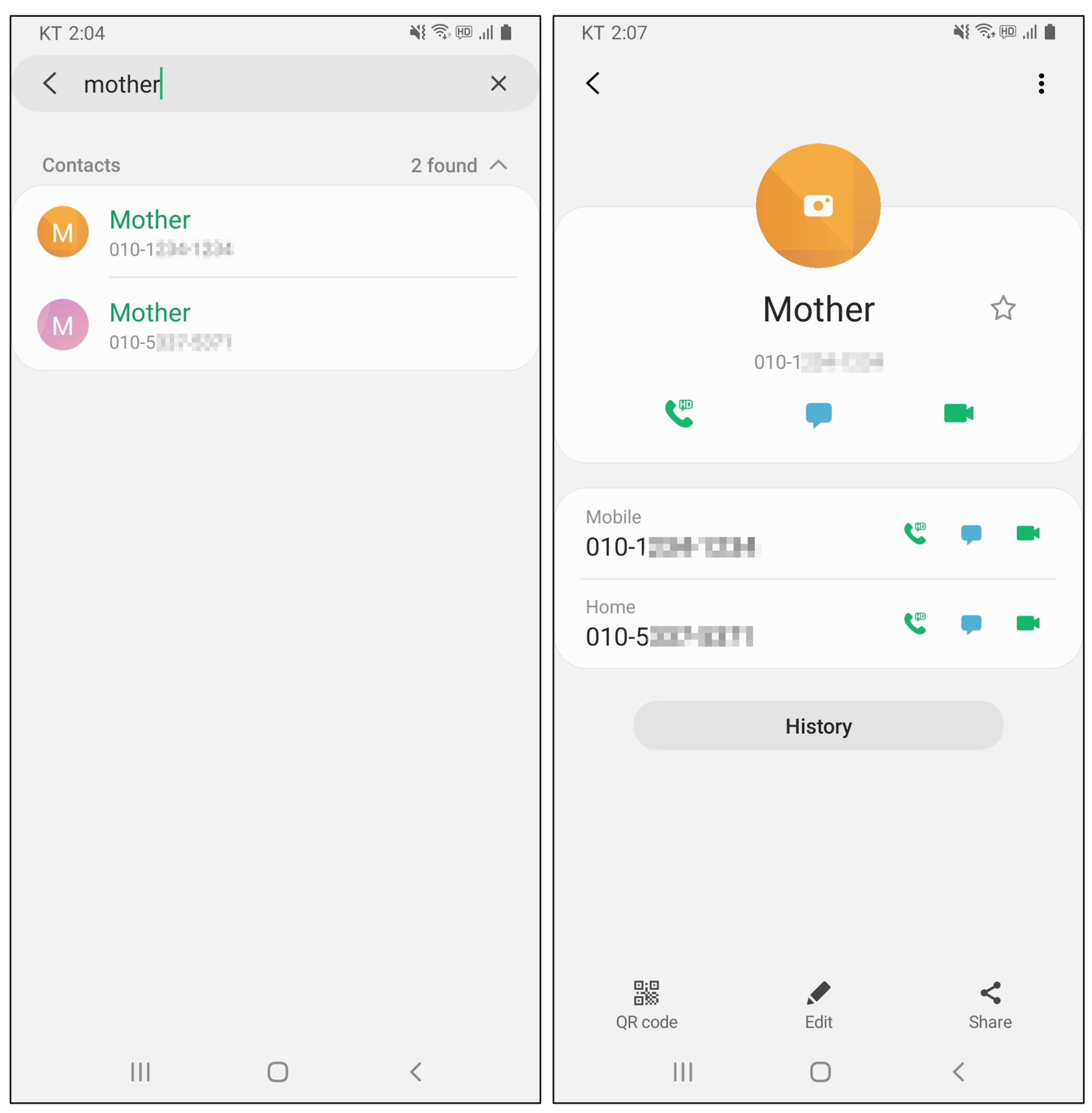

Figure 1 shows the incoming call screen on Android and iOS devices. Android users may overlook the actual number displayed beneath the contact name, and iOS users do not see the number at all, allowing attackers to exploit this limitation.

Application Repackaging. Application repackaging is a technique that involves decompiling an application, modifying its code, and recompiling it into a distributable format (such as Android Application Package (APK) or iOS Application Archive (IPA)). Attackers exploit this method by decompiling signed applications, adding malicious code, and repackaging them [

16]. The repackaged applications maintain the layout of the original applications, making it difficult for victims to detect the alterations [

17]. Attackers have deceived victims by utilizing vishing applications that encompass the previously mentioned behaviors. Experts caution that individuals and businesses incur annual financial losses amounting to millions of dollars as a result of vishing-related fraud [

2,

3]. To prevent vishing fraud, researchers have proposed various approaches to detect vishing behaviors using different methods [

4,

18,

19,

20]. Unfortunately, despite these efforts, incidents of financial loss resulting from vishing continue to rise [

21]. Therefore, we propose an approach to detect malicious behaviors, specifically Display Overlay, Call Redirection, and Duplicated Contacts, without modifying the Android OS.

2.2. Vishing Apps According to Android APIs Levels

The Android platform provides various APIs(e.g., TelephonyManager API, LocationManager API, etc.) that request information from the device or manipulate it directly, facilitating flexible feature development for applications. Attackers exploit these APIs to create malicious applications, such as vishing applications. Google has recognized these issues and has been consistently implementing security patches [

22,

23] including: removing APIs that can be exploited by malicious apps, restricting the values that apps can request from APIs, and requiring additional permission checks before app installation, among others. Specifically, Google introduced security patches in the API Level 29 update to prevent the abuse of Call Redirection [

24]. In this section, we introduce the alterations in Call Redirection and Display Overlay Attacks in vishing applications based on this security patch.

Lower API Level 29. In Android API Levels 28 and below, vishing applications implement Call Redirection using

BroadcastReceiver. At this level, the Android system broadcasts

NEW_OUTGOING_ CALL just before an outgoing call is made. Consequently, vishing applications can retrieve or modify the broadcast value in the

onReceive() callback function, thus invoking

getResultData() to obtain the victim’s phone number and using

setResultData() to redirect the call. Vishing applications involve Display Overlay to present a counterfeit screen when displaying specific call numbers. Therefore, these applications employ APIs to detect phone events and retrieve the incoming or outgoing numbers. Vishing applications utilize the

onCallStateChanged() and

onCallAdded() callback functions to retrieve call states and incoming number, as shown in

Table 1. Specifically,

onCallStateChanged() provides both incoming and outgoing phone numbers through

EXTRA_INCOMING_NUMBER.

API Level 29 and Above. In Android API Level 29 and above, Android modified the call-related APIs and categorized the phone permissions in more detail. First, to prevent Call Redirection that altered broadcast values, Android restricted access to broadcast values and introduced the CallRedirectionService. Android modified the behavior of the BroadcastReceiver so that the setResultData() method called just before an outgoing call returned null. Furthermore, for an application to utilize the CallRedirectionService, user consent is required, and the application must be registered as the default call redirecting app. Second, Android restricted the APIs that provided incoming or outgoing numbers in API Level 28 and below by introducing the CallScreeningService. In earlier versions, Android apps with permissions related to TelephonyManager could call APIs within callback functions to obtain call status as well as incoming or outgoing numbers. In these versions, Android added the CallScreeningService to manage call events and introduced settings for the default app for caller ID & spam. Therefore, for an Android app to access the call numbers, it must implement the CallScreeningService and obtain user consent to be registered as the default app. Finally, the APIs required to execute Display Overlay are available across all Android API levels.

2.3. Current Vishing Defenses

In practice, attackers circumvent safeguards by sharing vishing applications through websites or emails, rather than through application marketplaces like the Google Play Store [

7]. Due to the difficulty in preventing such distribution, companies offer applications that provide blacklist-based warnings or utilize Android APIs to present phone numbers. The Google Play Store hosts vishing defense applications, including Whowho [

25], Truecaller [

26], SafeVoice [

27], Hiya [

28], Whoscall [

29], Phishingeyes [

30], CallApp [

31], Show Caller ID & Spam Blocker [

32], and SmartAntiPhishing [

33]. Blacklist-based defenses add the attacker’s number to the blacklist after the victim has already suffered an incident, while defense applications utilizing Android APIs simply verify Call Redirection based on the numbers. These defense techniques are not effective against new Vishing applications or Display Overlay Attack.

In the state of the art, HearMeOut [

4] introduces an effective approach that modifies the operating system using the Android Open Source Project (AOSP) to detect invocations of Android APIs. This approach investigates the APIs that vishing applications use for malicious activities and alerts users to invocations of these APIs. However, it has limitations as follow: 1) it requires ongoing modifications to the operating system to keep up with continuous OS updates, and 2) it cannot recognize different APIs that perform similar malicious actions. These can be found in the

Table 2. Therefore, we examine Android APIs in vishing applications and propose an approach that does not require modifications to the Android OS.

3. Overview

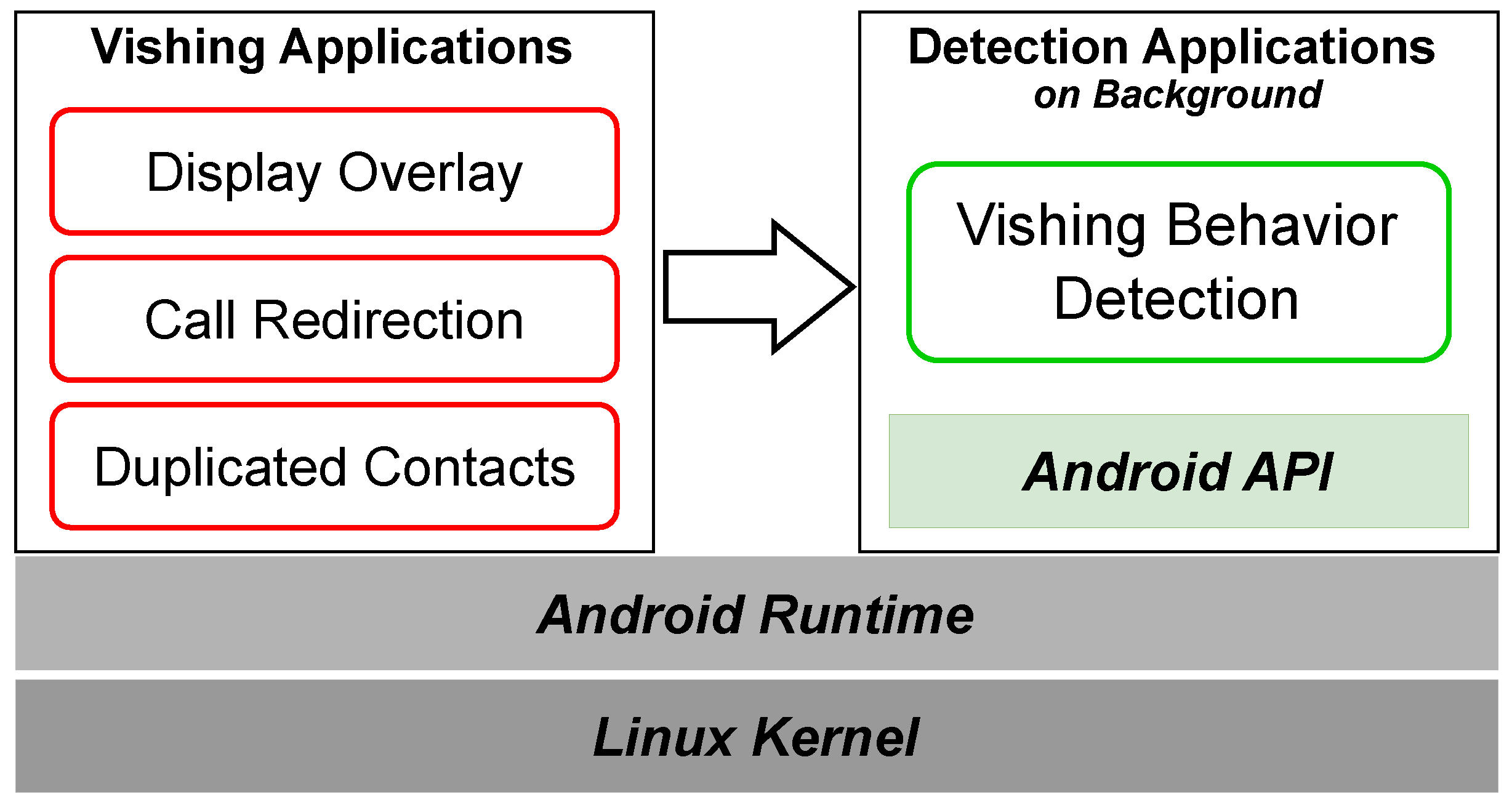

In this section, we present an approach for detecting malicious behavior in vishing applications running in the background. Our approach identifies malicious behaviors, including Call Redirection, Display Overlay, and Duplicated Contacts.

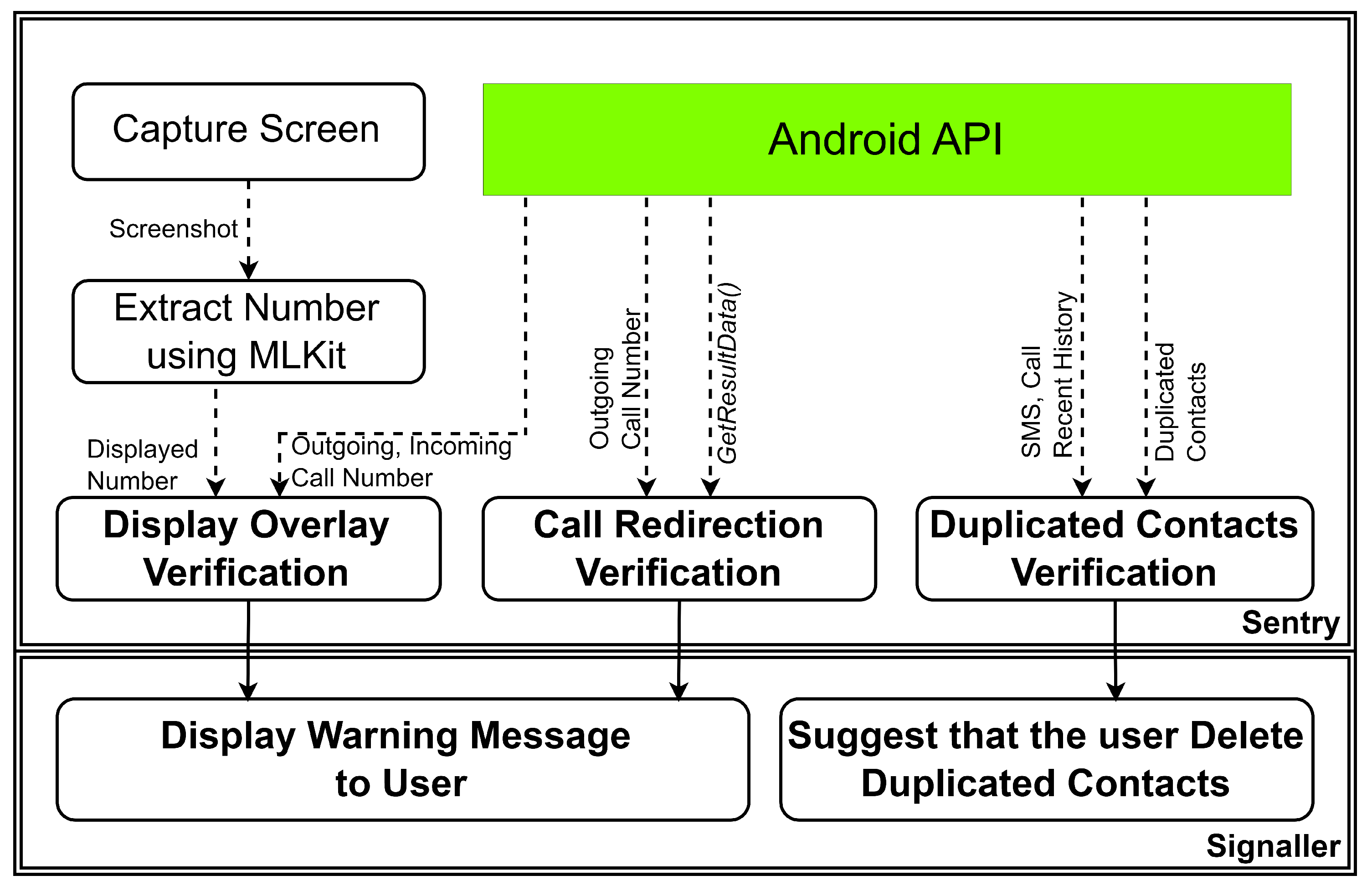

Figure 2.

Vishing App Detection Architecture at the Application Level.

Figure 2.

Vishing App Detection Architecture at the Application Level.

3.1. Call Redirection Detection

Vishing applications may include Call Redirection Attacks to alter the outgoing call on the victim’s phone using setResultData() or CallRedirectionService. These applications may also implement Display Overlay Attacks that obscure changes to the outgoing number, making it challenging for victims to detect call redirection. To detect Call Redirection Attacks, we retrieve and compare both the original outgoing number and the redirecting outgoing number using Android APIs. Additionally, we obtain the number displayed on the call standby screen and compare it with the actual outgoing number for double verification. This approach reduces the false positives, thereby protecting users from both inadvertent and malicious call alterations.

3.2. Display Overlay Detection

Vishing applications may employ Display Overlay Attacks that present a fake screen during call events (incoming or outgoing), preventing victims from identifying the actual numbers. To detect these Attacks, we compare the number displayed on the screen with the actual number retrieved using Android APIs. We capture a screen during call events and extract the phone number from the captured image using OCR. We also retrieve the actual incoming or outgoing number by invoking the Android APIs in the background application, and then we compare the extracted number from the screen with the actual number. Our approach enhances the detection of Call Redirection Attacks by double verification.

3.3. Duplicated Contacts Detection

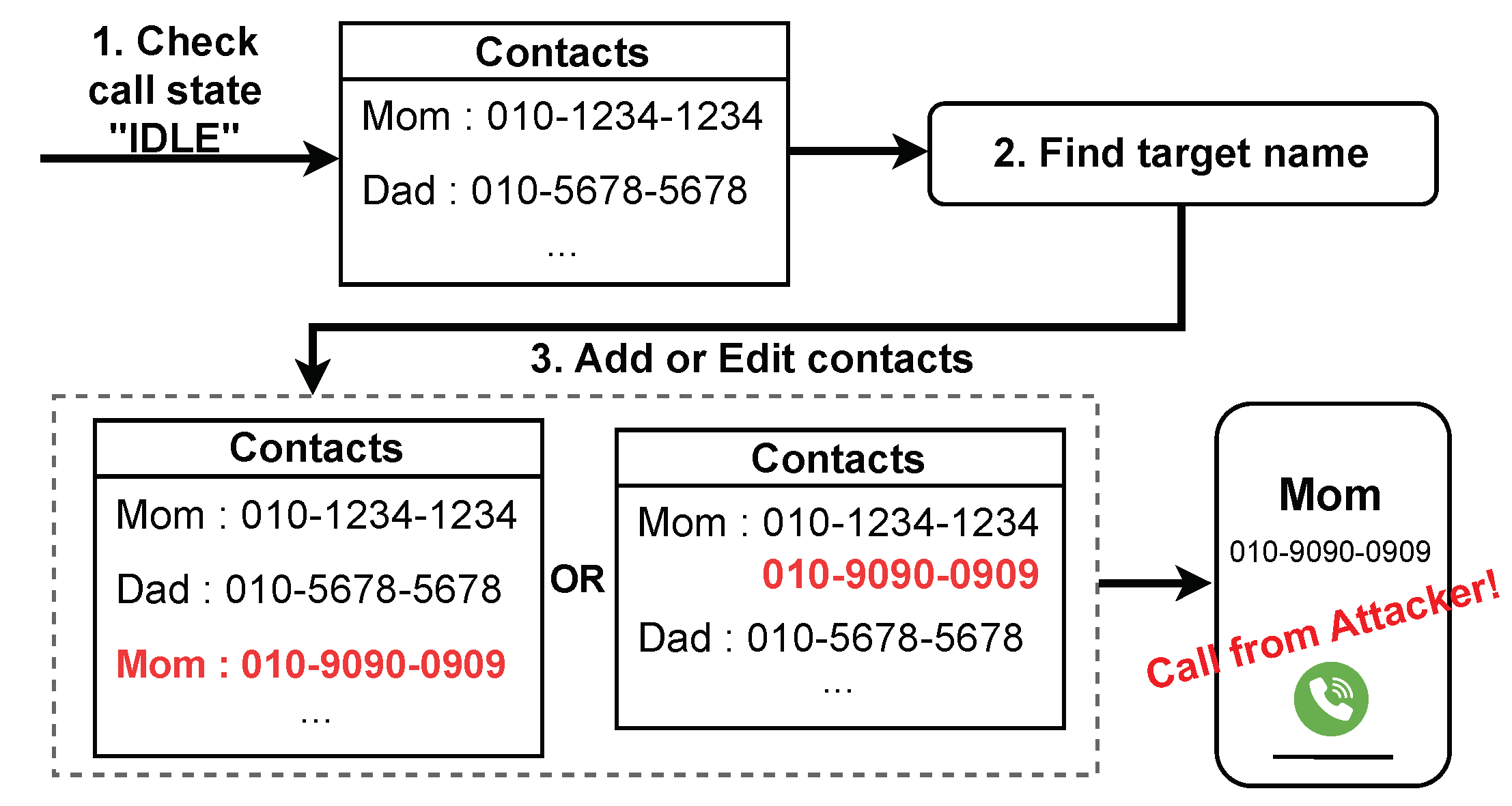

Vishing applications may conduct Duplicated Contact Attacks to make victims mistake an attacker’s number for an existing contact. Adding the attacker’s contact using a name that matches the target or editing the target’s contact to include the attacker’s phone number (i.e., the secondary phone number) can be seen in

Figure 3. These applications generate Duplicated Contacts by adding the attacker’s number either under an existing contact name or as a secondary phone number to an existing contact. To counter this, we identify contacts with duplicate names or secondary phone numbers and prompts the user to review and delete any suspicious duplicates.

Vishing applications may conduct Duplicated Contact Attacks to make victims mistake an attacker’s number for an existing contact. Adding the attacker’s contact using a name that matches the target or editing the target’s contact to include the attacker’s phone number (i.e., the secondary phone number) can be seen in

Figure 3. These applications generate Duplicated Contacts by adding the attacker’s number either under an existing contact name or as a secondary phone number to an existing contact. To counter this, we identify contacts with duplicate names or secondary phone numbers and prompts the user to review and delete any suspicious duplicates.

4. Design

In this section, we present

Ventinel, a system designed to detect the malicious behavior of vishing applications without necessitating modifications to the Android OS. As detailed in the

Figure 4,

Ventinel operates as a background application, detecting malicious activities from vishing applications in real time and promptly notifying the user.

Ventinel is composed of two core modules:

Sentryand

Signaller Sentry is continuously monitors vishing applications for signs of malicious behaviors,

Signaller sends alerts to users when

Sentry transmits information.

4.1. Sentry of Ventinel

The Sentry of Ventinel operates in the background to monitor the malicious behavior of vishing applications. It utilizes Android APIs to gather various types of information, such as incoming and outgoing numbers, to verify the presence of malicious activities. Sentry detects specific malicious behaviors, including Call Redirection, Display Overlay manipulation, and Duplicated Contacts. When the Android device is on IDLE and not engaged in a call, Sentry performs a Duplicate Contacts Verification. Upon the user’s attempt to initiate a call, Sentry conducts a Call Redirection Verification. Following this, Sentry carries out a secondary check through Display Overlay analysis. It captures the screen displayed by the device during both incoming and outgoing call states and performs a Display Overlay Verification to detect any potential malicious activity.

4.1.1. Duplicated Contacts Verification

The Sentry module conducts a search for duplicate contacts within the contacts stored on the Android device while in IDLE. Any contacts identified as duplicates are forwarded to the Signaller module for further action. Vishing applications can add or modify contacts without the victim’s awareness, causing the attacker’s number to appear on the incoming or outgoing call screen.

Algorithm 1 is pseudo code that enables the Sentry of Ventinel to perform Duplicate Contact Verification. The Sentry accesses the complete contact list, SMS messages, and call logs from the Android device. To facilitate Sentry, the following permissions must be granted by the user explicitly:

READ_CONTACTS

READ_SMS

READ_CALL_LOG

|

Algorithm 1 Duplicated Contact Verification. |

- 1:

List of existing Contacts - 2:

initialize empty hash table - 3:

for in do - 4:

name of - 5:

phone numbers of - 6:

- 7:

if already in then - 8:

Add to - 9:

end if - 10:

end for - 11:

initialize empty hash table - 12:

for each in do - 13:

if .length > 1 then - 14:

- 15:

end if - 16:

end for - 17:

List of Recent Call and SMS history - 18:

- 19:

for in do - 20:

phone number in - 21:

Add to - 22:

end for - 23:

for each in do - 24:

for in do - 25:

if then - 26:

Delete in - 27:

end if - 28:

end for - 29:

end for |

Once these permissions are obtained, the Sentry identifies any contacts with the same name or multiple phone numbers associated with a single name as duplicates. Additionally, phone numbers that exist in recent call and text records are created as a whiteList, assuming that they are related to the user. The Sentry then removes these whitelisted numbers from the identified duplicates, generating a list of suspicious duplicate contacts, which is subsequently forwarded to the Signaller.

4.1.2. Call Redirection Verification

The Sentry is designed to detect Call Redirection Attacks that intercept calls initiated by vishing applications and to alert the victim accordingly. To accomplish this, it utilizes Android APIs to request and validate call-related information from the device initiating the call. As such, Sentry requires the following permissions:

READ_PHONE_STATE

READ_CALL_LOG

For devices operating at API level 29 and lower, an additional permission, PROCESS_OUTGOING_ CALLS, is necessary, while devices operating at API level 29 and above require the permission READ_ PHONE_NUMBER. When a phone number is entered and the dial button is pressed in Android dialing applications, the operating system triggers theACTION_NEW_OUTGOING_CALL action and transmits EXTRA_PHONE_NUMBER, which contains the dialed number as an intent value. The Sentry requests this value and stores it in a designated variable for comparison against the phone number obtained when the call state transitions to EXTRA_STATE_OFFHOOK, as this value remains unaffected by any Call Redirection Attack. Subsequently, when the call state changes to EXTRA_STATE_OFFHOOK, the intent value is cleared, and the final dialed phone number is retrieved using getResultData(). The initially stored value (the intended phone number) is then compared with the final phone number received after dialing. The result of this comparison is forwarded to the Signaller. This approach is effective for detecting Call Redirection Attacks across both API levels 28 and below as well as 29 and above.

4.1.3. Display Overlay Verification

The Algorithm 2 as the pseudocode for

Ventinel’s Sentry to conduct Display Overlay Verification. To monitor for Display Overlay,

Sentry compares the phone numbers displayed on the screen during incoming and outgoing calls with the actual phone numbers being dialed. To initiate this process,

Sentry first captures the screen at the beginning of an incoming or outgoing call and utilizes ML Kit [

34], an OCR tool provided by Google, to extract the phone number displayed on the screen. This extraction process reads text that conforms to the phone number format from the top left to the right of the screen. Simultaneously,

Sentry employs Android APIs to retrieve the outgoing or incoming number that the device is attempting to dial. For outgoing calls, it retrieves the number from the

ACTION_NEW_OUTGOING_CALL action, while for incoming calls, it uses

getStringExtra(incomingNumber). Finally,

Sentry compares the two phone numbers obtained during the call event to determine whether a Display Overlay has occurred and forwards the results to the

Signaller. To facilitate screen capture, Ventinel sets the foreground service type to mediaProjection and requires the following permissions:

READ_PHONE_STATE

READ_CALL_LOG

|

Algorithm 2 Display Overlay verification of incoming call. |

- 1:

Captured Screenshot - 2:

Extracted Phone Number from

- 3:

234 - 4:

Phone Call State - 5:

if is EXTRA_STATE_RINGING then - 6:

Incoming Phone Number - 7:

if is not then - 8:

Detect Malicious Behavior - 9:

end if - 10:

end if - 11:

if is EXTRA_STATE_OFFHOOK then - 12:

Outgoing Phone Number - 13:

if is not then - 14:

Detect Malicious Behavior - 15:

end if - 16:

end if |

For devices operating at API level 29 and above, an additional permission,

READ_PHONE_NUMBER, is necessary. To implement the APIs that verify the outgoing number, the permissions detailed in

Section 4.1.2 must be obtained. Moreover, to ensure

Ventinel can run in the background together with other applications, it necessitates the

FOREGROUND_SERVICE permission.

4.2. signaller of Ventinel

In the Ventinel, the Signaller is responsible for notifying users of the malicious behaviors identified by the Sentry in real time. The Signaller generates a vibration on the device and displays a warning pop-up to alert the user of any detected Display Overlay or Call Redirection Attacks. To address Duplicated Contacts Attacks, the Signaller presents the user with a list of identified suspicious contacts and requests their consent to delete these entries. Upon receiving the user’s approval, the Signaller proceeds with the deletion of the specified contacts.

5. Evaluation

In this section, we present benchmarks to evaluate Ventinel’s detection and discuss the comparative results between Ventinel and commercial applications. Additionally, we conduct a manual analysis of select commercial applications to identify critical factors influencing their detection rates. To assess Ventinel’s reliability from a user perspective, we also conducted a user study involving 200 Android users.

5.1. Benchmark with Vishing Malicious Behavior

To evaluate Ventinel, we required vishing applications; however, we opted to use a benchmark with malicious behaviors, given the typically short lifecycle of vishing applications. Consequently, we developed a benchmark application that incorporates the following malicious behaviors: Display Overlay, Call Redirection, and Duplicated Contacts.

Idle. In Idle state, vishing applications exploit Duplicated Contacts with procedures described in

Figure 5. The attack begins while the device is in an

IDLE state (i.e.,

PHONE_STATE_IDLE) with no incoming calls ➀. The attacker searches for names in the contact list that match predefined target names (e.g., mother, mom, mum, mama, etc.) ➁. If a target name is found, the attacker either saves their own phone number under the same name as the target contact or adds their number to the existing target contact ➂. Consequently, when an incoming call event occurs, the attacker’s number will appear under the target name. And if the user is not vigilant, the attack may go unnoticed. Additionally, when saving a number with an identical name, the Android system does not display a notification or toast message, potentially preventing the user from realizing that an unwanted contact has been added.

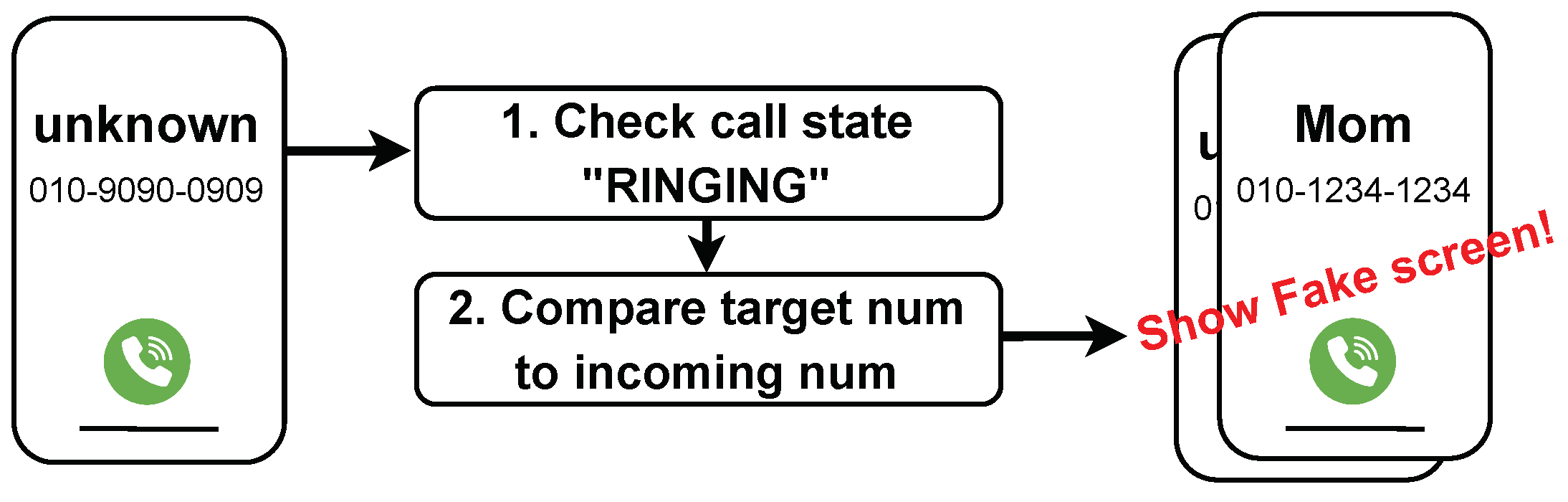

Incoming Call. A vishing application leverages Display Overlay to alter the caller ID displayed when an attacker places a call to the user. This attack follows the steps outlined in

Figure 6. Initially, the application monitors changes in phone state to detect when an incoming call event begins ➀. Once an incoming call event triggers and the phone state changes to

EXTRA_STATE_RINGING, the attacker checks if the incoming call number matches the pre-set number using

EXTRA_PHONE_NUMBER ➁. If the incoming number aligns with the attacker’s preset, a fake incoming call screen, embedded within the application, overlays the display, thereby executing the Display Overlay Attack.

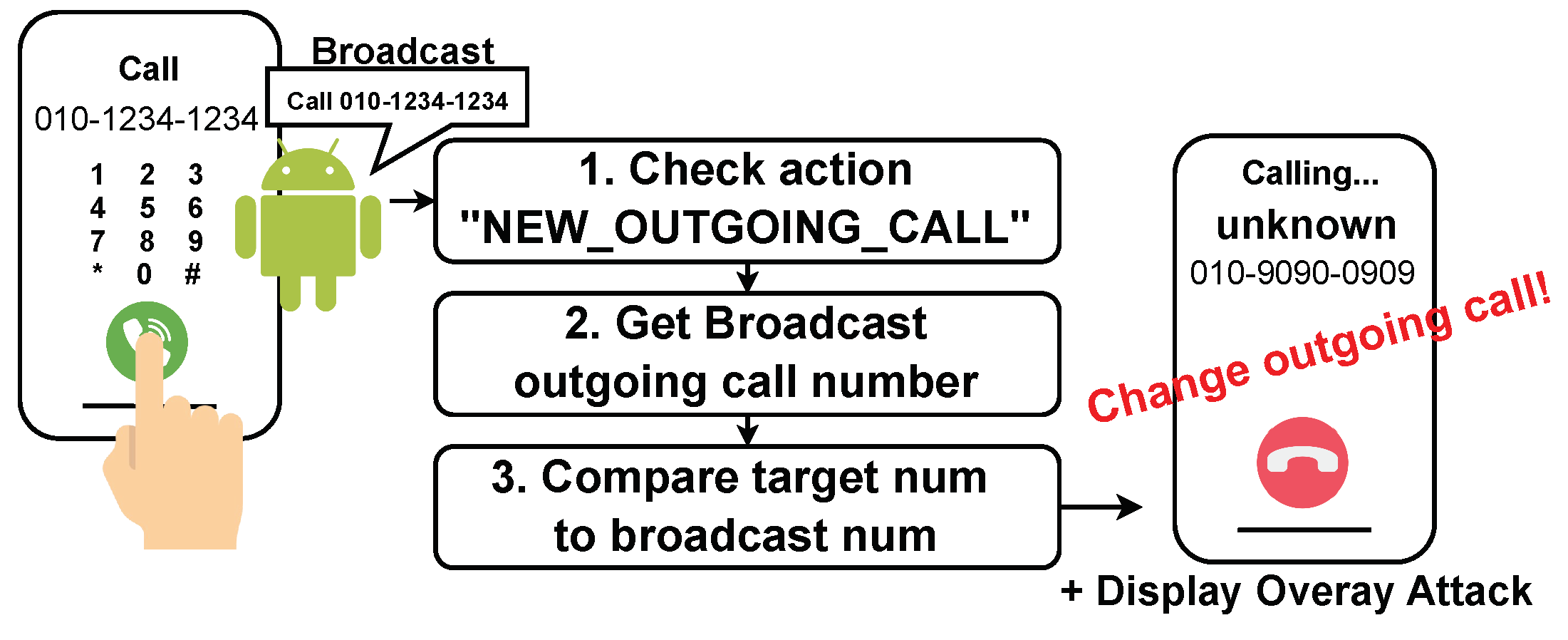

Outgoing Call. Finally, if the user attempts to dial a number targeted by the attacker, Call Redirection is employed. The vishing application conducts this attack step-by-step, as described in

Figure 7. First, when the user presses the dial button, the vishing application checks if the outgoing call event has started using

getAction ➀. If the call state is

ACTION_NEW_OUTGOING_CALL, the application retrieves the number stored in

EXTRA_PHONE_NUMBER ➁. Should this number match the attacker’s target, the vishing application uses

setResultData() to replace the dialed number with one designated by the attacker ➂. Once the outgoing number is altered, the number displayed to the user also changes, necessitating the use of Display Overlay to re-display the originally dialed number. This re-display occurs when the phone state switches to

EXTRA_STATE_OFFHOOK, overlaying a fake incoming call screen to mask the redirection, thereby preventing the user from detecting any manipulation.

5.2. Comparative Analysis

We conducted a comparative evaluation of vishing defense applications registered on the Google Play Store against

Ventinel using the benchmarking applications we developed, as outlined in

Section 5.1. Additionally, to prevent false positives from approved applications exhibiting behavior similar to Display Overlay Attacks, we analyzed the top four most downloaded call screen theme applications to assess whether they were detected as vishing applications. For evaluation, we categorized detection outcomes as follows: detecting a approved application as benign was classified as a True Negative (TN), detecting a approved application as malicious behavior was classified as a False Negative (FN), detecting a benchmark application as malicious behavior was classified as a True Positive (TP), and detecting a benchmark application as benign behavior was classified as

a False Positive (FP). As shown in

Table 3, most commercial applications available on the Google Play Store failed to detect the malicious behaviors employed by vishing applications. Some applications that can identify these malicious behaviors provide warnings by displaying the incoming or outgoing phone number to the user through pop-up windows when call events occur. Additionally, certain applications compare the incoming phone number at the start of a call with the number displayed when the call transitions to the

OFFHOOK state, alerting the user to any discrepancies. However, these approaches are generally limited, as they primarily provide indirect warnings to users or are confined to detecting specific malicious behaviors only. Consequently, to compare defensive measures and address their shortcomings, we manually analyzed the Safe Voice and Call Blocker applications.

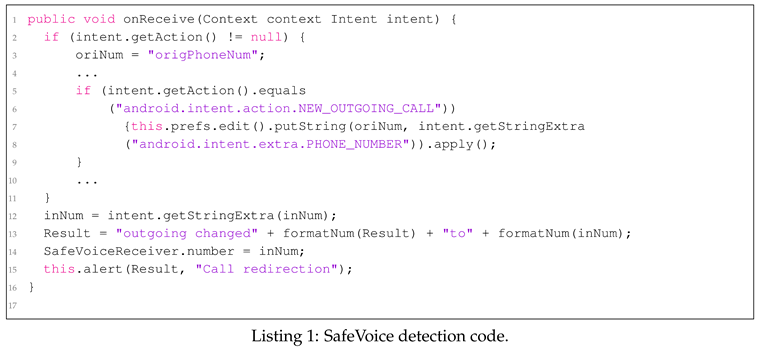

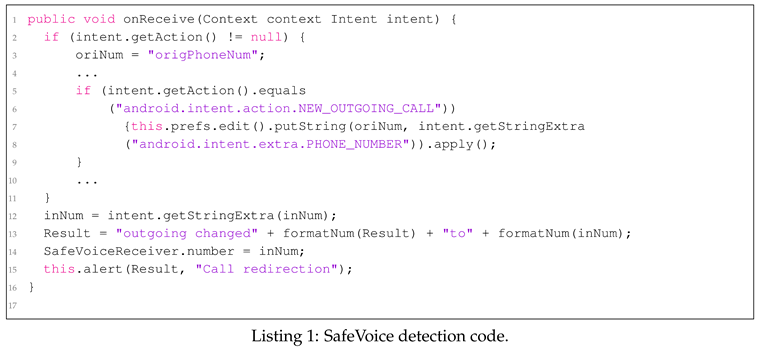

SafeVoice. The primary goal of the SafeVoice application is to verify whether the phone number has been altered during outgoing and incoming events and to notify the user accordingly [

27]. The application first checks whether phone-related permissions are granted in Call Modulation and monitors for outgoing events. If an

ACTION_NEW_OUTGOING_CALL event occurs, the app retrieves the phone number using

EXTRA_PHONE_NUMBER, attaches a specific tag to it, and stores it in

SharedPreferences. This stored phone number is then saved in the Result using

getSharedPreference(tag), while the outgoing number is stored in CallModulation using

getStringExtra. Finally, if a discrepancy is detected between the Result (i.e., Original Number) and the CallModulation (i.e., Outgoing Number), the application alerts the user through

alert. The operational flow can be observed in the code presented in Listing 1. At the time of an outgoing call, SafeVoice displays

EXTRA_PHONE_NUMBER alongside

getStringExtra(IncomingNumber) to the user. However, this process fails to compare the number collected during the outgoing event with any other numbers before displaying it to the user, limiting its ability to detect Display Overlay Attacks that may occur during incoming events. Additionally, because the values stored in

SharedPreferences do not change until the next outgoing call occurs, any subsequent legitimate incoming call may incorrectly be detected as tampered.

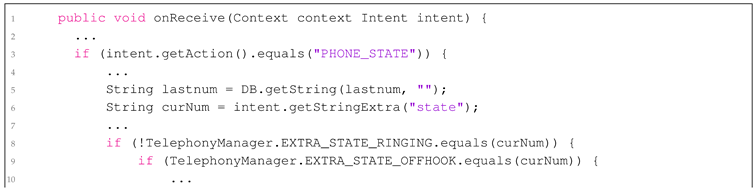

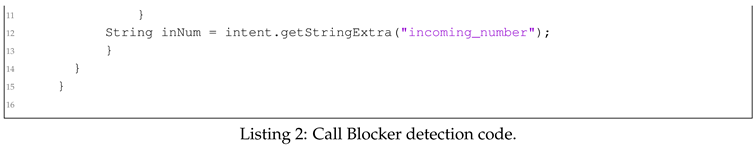

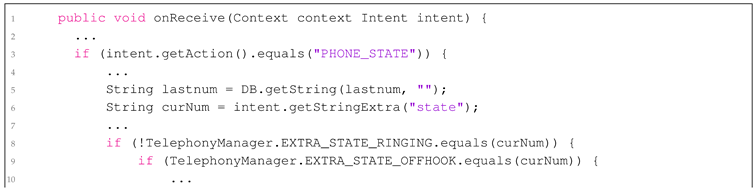

Call Blocker. The Call Blocker application aims to display the appropriate phone number to the user via a pop-up based on the current phone state [

35]. To achieve this, the application checks whether the phone state (i.e., CurrentState) is

RINGING or

OFFHOOK using

getStringExtra(state). It then retrieves the phone number with

getStringExt- ra(IncomingNumber) and presents it to the user. This process can be observed in the code provided in Listing 2. Users can verify the phone number displayed by Call Blocker in the pop-up when either an incoming or outgoing call event occurs. However, the application fails to detect any alterations or provide warnings when a manipulation takes place, making it incapable of directly identifying Display Overlay and Call Redirection Attacks. Thus, while Call Blocker effectively shows the relevant phone number during call events, its inability to alert users to potential tampering or manipulations limits its effectiveness as a vishing defense tool.

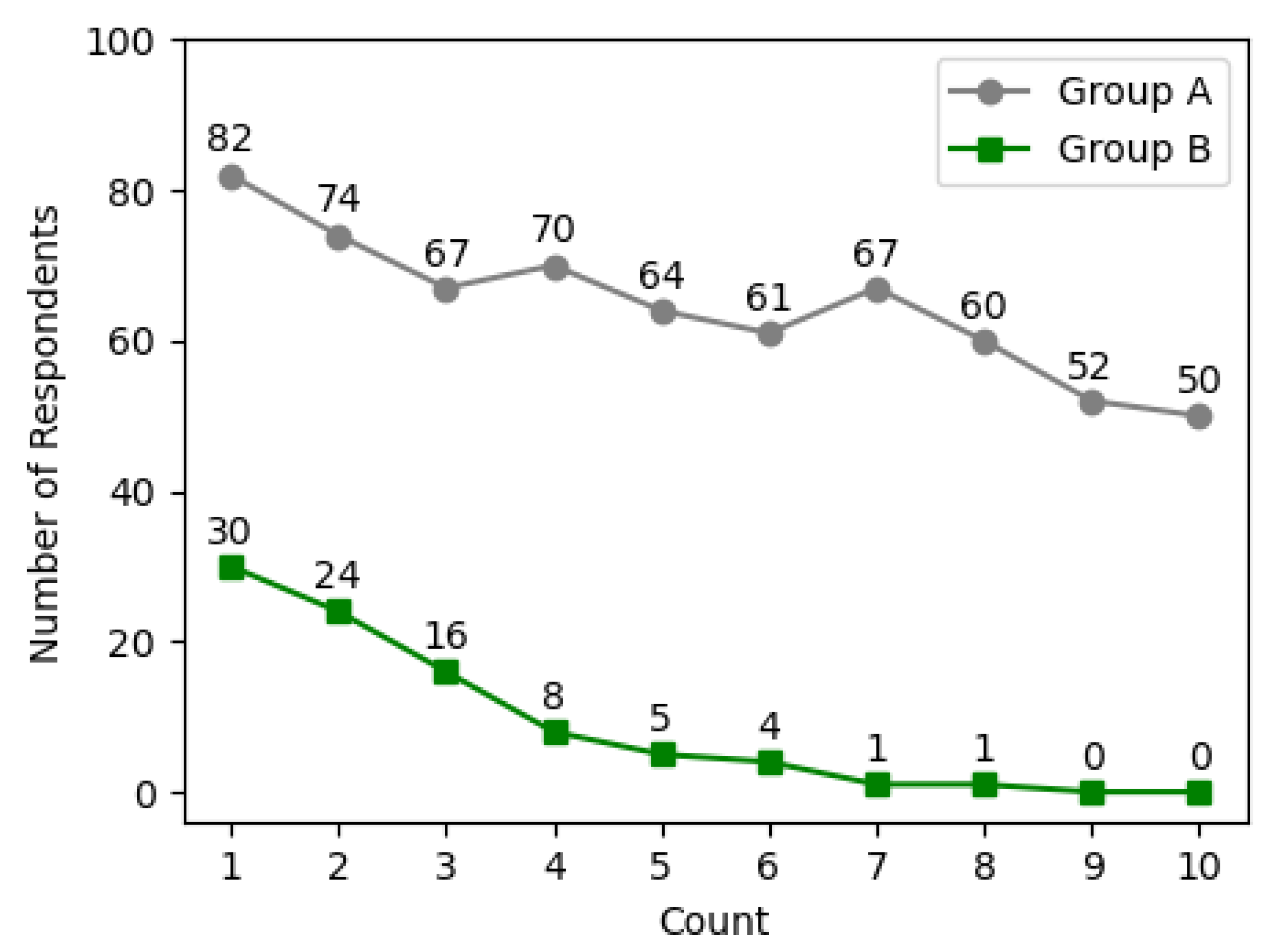

5.3. User Study

To validate the proposed technique, we recruited 100 participants for Group A, who received vishing applications, and another 100 participants for Group B, who were provided with both vishing applications and

Ventinel. All participants used Android devices, with the Android version randomly selected. Participants were recruited under the pretext of a study unrelated to vishing, ensuring they would not recognize the functioning of the vishing applications. After the experiment concluded, we informed them about the study’s true nature and requested their participation in a survey regarding vishing. The experiment lasted one week, during which both incoming and outgoing calls were executed randomly. An incoming call was considered unanswered if the participant did not respond, while an outgoing call was counted as unanswered if the subject ended the call within five seconds after answering. As shown in

Figure 8, Group A had an average response rate of approximately 64.7% across ten tests, whereas Group B exhibited an average response rate of only 8.9%. These results demonstrate that

Ventinel effectively defends against vishing applications.

6. Discussion

Ventinel is engineered to detect attacks from vishing applications(Call Redirection, Display Overlay, and Duplicated Contacts)while operating in the background without necessitating modifications to the Android OS. Vishing applications employ diverse attack strategies across different Android API levels. To address this, we conducted an in-depth analysis of the malicious behavior patterns associated with various API levels and developed Ventinel to effectively identify and mitigate these threats.

Lacking visibility. In the

Section 5.3, Group B, which utilized

Ventinel, demonstrated an average response rate of 8.9%. Although the overall figure is extremely low, we analyzed the experiment to understand why a specific part of Group B exhibited the high response rate. The analysis indicated that the signaller’s warning window lacked sufficient visibility. Additionally, the widespread use of bluetooth earphones and wearable devices led to instances where participants failed to notice the warnings. To address this issue, it is essential to enhance the delivery of alerts related to malicious activities by incorporating voice prompts or establishing a connection between the wearable device and the user’s mobile phone for more effective notifications.

APIs permission settings. Ventinel functions entirely within the confines of the application and requires explicit user authorization to operate effectively. It is essential that we provide appropriate notification to users to ensure that all necessary permissions are granted. Furthermore, Ventinel utilizes an APIs that Google has mandated be disabled starting from API level 29. Consequently, if the minimum API level is set to 29 or higher, this feature will be completely deactivated. To address this limitation, it is essential to switch to an alternative APIs that gives the same results.

Relay Station Attack. Ventinel is designed to protect against the malicious techniques employed by vishing applications. However, it is important to note that if a relay station alters the phone number,

Ventinel will be unable to detect this modification. To mitigate this limitation, it is necessary to utilize the relay station detection APIs provided by services such as Twilio [

36], Hiya [

37], YouMail [

38], and others. Since domestic services are not supported, close collaboration with telecommunications providers such as SK Telecom [

39], LG Telecom [

40], and KT Telecom [

41] will be essential for effective implementation.

7. Related Work

Various solutions exist to mitigate the impact of vishing, which can be categorized into pre-incident and post-incident techniques. This section provides an overview of vishing defense methods, dividing them into pre-incident and post-incident approaches.

7.1. Pre-Incident Detection

7.1.1. Typical Approaches

To prevent vishing and mobile fraud, governments and corporations typically conduct mobile security training [

7]. Mobile security education enhances cybersecurity awareness among general users, helping them become more familiar with security terminology. However, Chin et al. [

42] indicate that there is little difference in security awareness between groups that received mobile security training and those that did not, suggesting that such training alone is not effective in blocking vishing.

Table 4.

Specific functions monitored by HearMeOut.

Table 4.

Specific functions monitored by HearMeOut.

| Call Redirection |

broadcastIntent() |

| setResultData() |

| onCreateOutgoingConnection() |

| Call Screen Overlay |

WindowManagerImpl,addView() |

| onCreateOutgoingConnection() |

| onCreateIncomingConnection() |

| Fake Call Voice |

onCallStateChanged() |

| onAudioFocusChanged() |

| onPlaybackStateChanged() |

7.1.2. API Trace-Based Approaches

HearMeOut [

4] was proposed as a modified version of AOSP to automatically detect and alert users to vishing attempts that may otherwise go unnoticed. HearMeOut monitors three features implemented using the functions listed in Table 4, which are utilized by vishing applications. Through this, HearMeOut detects Call Redirection and Call Screen Overlay as pre-incident detection, and detects Fake Call Voice as a post-incident detection.

HearMeOut recruited a total of 45 Android users for evaluation. Among them, 23 participants did not use HearMeOut, while 22 participants used it. The experiment was conducted by having participants make calls to the official Woori Bank service center using pre-installed Pixel 2 phones. Ultimately, HearMeOut achieved a 100% detection rate for the three techniques and recorded zero false positives. However, it has limitations, as it is vulnerable to changes, deletions, or additions to the APIs and functions supported by android. Addressing this issue requires support from AOSP maintainers and collaboration with android.

7.2. Post-Incident Detection

7.2.1. Voice Recognition-Based Approaches

Viking [

9] proposed a method designed to assist victims by leveraging AI to recognize and respond to real-time conversations during incoming and outgoing calls (i.e., Social Engineering Attacks). The operational process of Viking involves collecting information through Text-To-Speech (TTS) when a call occurs and relaying this information to a trained LLMs for risk assessment of the conversation. For instance, if language patterns indicative of sensitive information requests or urgent actions are detected, the conversation is deemed risky, and the system alerts the victim, providing them with suggested responses. Ultimately, Viking aims to help victims protect their privacy and safely terminate conversations with attackers. However, Viking faces limitations due to the restricted dataset used for training the LLMs, which may introduce data sets. Additionally, utilizing an LLMs demands substantial resources, posing significant challenges for real-time processing and potentially leading to delays in response generation.

7.2.2. Blacklist-based approaches

The applications that failed to detect benchmarks in

Section 5.2 all operate on a blacklist basis. Blacklist-based approaches are easy to implement and have the advantage of being able to block any phone numbers used for vishing once they are registered. However, until the numbers used by attackers are included in the blacklist, victims continue to incur losses. Moreover, attackers can easily create new phone numbers using burner phones, making it challenging to mitigate the impact of vishing attacks.

8. Conclusion

This study analyzes the APIs used by vishing applications and reveals that malicious behaviors, such as Call Redirection, Display Overlay and Duplicated Contacts can still be executed using specific APIs available at API Level 29 and above. This finding confirms the vulnerabilities associated with APIs modifications and additions presented in the HearMeOut [

4]. To address these issues, we propose

Ventinel. We evaluated the detection accuracy of

Ventinel using benchmarks from API Level 28 and below, as well as those from API Level 29 and above, achieving a high detection rate. Additionally, the application is designed to operate with minimal permissions at the app level, making it easy for users to install and use. Finally, user studies demonstrate that

Ventinel is a robust tool capable of accurately detecting and warning against vishing applications. This research contributes to a better understanding of vishing and may assist future studies in this domain.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K.; methodology, D.K.; software, D.K. and S.O.; validation, D.K.; formal analysis, D.K.; investigation, D.K.; resources, D.K. and S.O.; data curation, D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K., O.S., Y.B., K.J and H.C.; supervision, J.P., K.J and H.C.; project administration, H.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Institute of Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2024-00398353, Development of Countermeasure Technologies for Generative AI Security Threats).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Institute of Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2024-00398353, Development of Countermeasure Technologies for Generative AI Security Threats).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kolandaisamy, R.; Rajagopal, H.; Kolandaisamy, I. Emergence of Cybercrimes in Online Social Networks 2024.

- The Most Common Types of Cyber Crime. https://www.statista.com/chart/24593/most-common-types-of-cyber-crime/. 2024.04.

- Hashmi, S.I.; George, N.; Saqib, E.; Ali, F.; Siddique, N.; Kashif, S.; Ali, S.; Bajwa, N.U.H.; Javed, M. Training Users to Recognize Persuasion Techniques in Vishing Calls. Extended Abstracts of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2023, pp. 1–8.

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Wi, S.; Kim, Y.; Son, S. HearMeOut: detecting voice phishing activities in Android. Proceedings of the 20th Annual International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications and Services, 2022, pp. 422–435.

- Das, S.; Ganguly, D. Protecting Your Assets: Effective Use of Cybersecurity Measures in Banking Industries. In Next-Generation Cybersecurity: AI, ML, and Blockchain; Springer, 2024; pp. 265–286.

- Tu, H.; Doupé, A.; Zhao, Z.; Ahn, G.J. Users really do answer telephone scams. 28th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 19), 2019, pp. 1327–1340.

- Yeboah-Boateng, E.O.; Amanor, P.M. Phishing, SMiShing & Vishing: an assessment of threats against mobile devices. Journal of Emerging Trends in Computing and Information Sciences 2014, 5, 297–307. [Google Scholar]

- Maggi, F. Are the con artists back? a preliminary analysis of modern phone frauds. 2010 10th IEEE International Conference on Computer and Information Technology. IEEE, 2010, pp. 824–831. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, J.; Carvalho, A.; Castro, D.; Gonçalves, D.; Santos, N. On the Feasibility of Fully AI-automated Vishing Attacks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.13793, arXiv:2409.13793 2024.

- Khonji, M.; Iraqi, Y.; Jones, A. Phishing detection: a literature survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2013, 15, 2091–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, B.; Perova, K.; Farooq, A.; Makhdoom, I.; Oyedeji, S.; Porras, J. Mitigation strategies against the phishing attacks: A systematic literature review. Computers & Security, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Gomez, L.; Neamtiu, I.; Faloutsos, M. Malicious android applications in the enterprise: What do they do and how do we fix it? 2012 IEEE 28th International Conference on Data Engineering Workshops. IEEE, 2012, pp. 251–254. [CrossRef]

- Android developer PopupWindow. https://developer.android.com/reference/android/widget/Popup Window. 2024.10.

- Android developer WindowManager. https://developer.android.com/reference/android/view/Window Manager. 2024.10.

- Finley, J.R.; Naaz, F.; Goh, F.W.; Finley, J.R.; Naaz, F.; Goh, F.W. Results: Behaviors and experiences with internal and external memory. Memory and technology: How we use information in the brain and the world.

- Muhammad, Z.; Anwar, Z.; Javed, A.R.; Saleem, B.; Abbas, S.; Gadekallu, T.R. Smartphone Security and Privacy: A Survey on APTs, Sensor-Based Attacks, Side-Channel Attacks, Google Play Attacks, and Defenses. Technologies 2023, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, S.; Zhou, B.; Karabiyik, U. Are we really protected? An investigation into the play protect service. 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data). IEEE, 2019, pp. 4997–5004. [CrossRef]

- Griffin, S.E.; Rackley, C.C. Vishing. Proceedings of the 5th annual conference on Information security curriculum development, 2008, pp. 33–35.

- Jain, A.K.; Gupta, B. A survey of phishing attack techniques, defence mechanisms and open research challenges. Enterprise Information Systems 2022, 16, 527–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.S.; Armstrong, M.E.; Tornblad, M.K.; Namin, A.S. How social engineers use persuasion principles during vishing attacks. Information & Computer Security 2020, 29, 314–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phishing Activity Trends Report 4th Quarter 2023. https://apwg.org/trendsreports/. 2024.04.

- Android Security Bulletins. https://source.android.com/docs/security/bulletin/asb-overview?hl. 2024.10.

- All android releases. https://developer.android.com/about/versions. 2024.10.

- Android developers android 9 changes. https://developer.android.com/about/versions/pie/android-9.0-changes-all. 2024.10.

- Whowho. https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.ktcs.whowho&hl. 2024.10.

- Truecaller. https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.truecaller&hl. 2024.10.

- SafeVoice. https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=co.safevoice&hl. 2024.08.

- Hiya. https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.webascender.callerid&hl. 2024.10.

- Whoscall. https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=gogolook.callgogolook2. 2024.10.

- phishingeyes. https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.infinigru.lite.phishingeyes&hl. 2024.10.

- CallApp. https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.callapp.contacts. 2024.10.

- Show Caller ID & Spam Blocker. https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.truecaller.callerid.callername&hl. 2024.10.

- SmartAntiPhishing. https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.infinigru.sap.phishingeyes&hl. 2024.10.

- Google ML Kit. https://developers.google.com/ml-kit. 2024.06.

- Call Blocker. https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=call.blacklist.blocker&hl. 2024.08.

- Twilio. https://www.twilio.com/en-us. 2024.11.

- Hiya. https://www.hiya.com/. 2024.11.

- YouMail. https://www.youmail.com/. 2024.11.

- SK telecom. https://www.sktelecom.com/index_en.html. 2024.11.

- LG telecom. https://www.lguplus.com/. 2024.11.

- KT telecom. https://www.kt.com/. 2024.11.

- Chin, A.G.; Etudo, U.; Harris, M.A. On mobile device security practices and training efficacy: An empirical study. Informatics in Education 2016, 15, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).